Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen, causes infections associated with a high incidence of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised hosts. Production of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), primarily by cells of monocytic lineage, is a crucial event in the course of these infections. During in vivo infections with P. aeruginosa, both lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and extracellular slime glycolipoprotein (GLP) produced by mucoid and nonmucoid strains are released. In the present study, we sought to explore the relative contributions of these two bacterial products to TNF-α production by human monocytes. To this end, fresh human monocytes and THP-1 human monocytic cells were stimulated with P. aeruginosa LPS or GLP. GLP was found to be a more potent stimulus for TNF-α production (threefold higher) by human monocytes than LPS. Moreover, its effect was comparable to that of viable bacteria. Quantitative mRNA analysis revealed predominantly transcriptional regulation. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays and transfection assays demonstrated activation of NF-κB and activator protein 1 (AP-1). NF-κB activation by GLP was rapid and followed the same time course as that by viable bacteria, suggesting that bacteria could directly activate NF-κB through GLP. Moreover P. aeruginosa GLP induced the formation of AP-1 complex with delayed kinetics compared with NF-κB but much more efficiently than the homologous LPS. These results identify GLP as the most important stimulant for TNF-α production by human monocytes. Activation of NF-κB and AP-1 by P. aeruginosa GLP may be involved not only in TNF-α induction but also in many of the inflammatory responses triggered in the course of infection with P. aeruginosa.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an environmentally ubiquitous, extracellular, opportunistic pathogen that is associated with severe infections of immunocompromised or critically ill patients and individuals with cystic fibrosis or severe burns (7). The local or systematic inflammatory responses associated with severe P. aeruginosa infections are mediated by a wide range of proinflammatory and inflammatory cytokines produced by continuously stimulated host cells. These include cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage that play a central role in initiating the innate immune response that leads to activation of the adaptive response. Their role is exerted by the production of a wide range of cytokines, including interleukin-1 α (IL-1α), IL-1β, and, most importantly, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α).

A number of cellular and extracellular constituents of P. aeruginosa have been identified to stimulate, at various levels, TNF-α synthesis and release from human monocytes/macrophages. These include lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (32, 40, 50), porins (12), pyocyanin (46), and exoenzyme S (17). Slime, the surface polysaccharide, has received much attention for its role in stimulating monocytes/macrophages to overproduce TNF-α. Most of the studies have focused on mucoid polysaccharide (also called alginate) produced only by strains isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis (34). However, some studies had shown that the extracellular slime glycolipoprotein (GLP) is produced in vivo by both mucoid and nonmucoid strains and possesses many biological properties comparable to those of viable cells (14, 15, 37). Although alginate is present in small quantities in the extracellular product of nonmucoid strains, the GLP component is more prominent (1). GLP is mitogenic for human peripheral blood and cord blood lymphocytes and a subset of murine B cells (33, 48). More interestingly, active or passive immunization with rabbit anti-GLP protects mice against a lethal challenge with viable cells (14). The extracellular slime GLP is clearly distinct biologically from the LPS of the cell envelope. Thus, the neutral sugar composition between GLP and LPS differs qualitatively (15). Adsorption of anti-GLP serum with GLP completely removes the serum protection afforded by serum against challenge by the homologous viable cells, whereas adsorption with the homologous LPS does not do so (37). Finally GLP inhibits phagocytosis in vitro, whereas LPS from the same strain does not (37).

TNF-α is the most important factor in triggering the lethal effects of septic shock syndrome, cachexia, and other systemic manifestations of disease. It is also a vital mediator of the host defense against infection (42). Since it exhibits both beneficial and pathological effects, it is conceivable that its expression is rigorously regulated both at transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (24). Transcriptional regulation of TNF-α is both stimulus and cell type specific (27). Regulation of human TNF-α expression in cells of monocytic lineage is quite complex and differs with different stimulants. The promoter of the human TNF-α gene contains potential binding sites for a complex array of transcription factors, including NF-κB, activator protein 1 (AP-1), and CREB. A number of studies have shown that the transcription factor NF-κB acts in concert with other transcription factors to stimulate maximal TNF-α production by human monocytes in response to bacterial or viral stimuli (23, 28, 38, 43, 49). More recent studies emphasize the role of Ets, Elk-1, and Sp1 recruitment to TNF-α promoter in response to LPS (44).

The interaction of P. aeruginosa with the host is complex, and no general agreement exists on the molecular events underlying its pathogenesis. Because of the importance of P. aeruginosa as a pathogen and the previous evidence for a crucial role of GLP, we sought to determine the relative contribution of GLP compared to LPS, a potent inducer of TNF-α production, and the molecular mechanisms involved. We report here that in contrast with P. aeruginosa LPS, the extracellular slime GLP of P. aeruginosa is a potent stimulant for TNF-α production by human monocytes and that its effect is comparable to that of Escherichia coli LPS, a well-known potent TNF-α stimulant, and to that of viable whole bacterial cells. Regulation of TNF-α production induced by P. aeruginosa GLP occurs at the transcriptional level and involves the transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

RPMI 1640 cell culture medium containing 40 μg of gentamicin/ml and low-endotoxin fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from GIBCO BRL (Grand Island, N.Y.). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for cell differentiation and stimulation, LPS from E. coli (O127:B8), LPS from P. aeruginosa (serotype 10), and exotoxin A from P. aeruginosa were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). TNF-α enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from R&D Systems Inc. (Minneapolis, Minn.). Anti-NF-κBp50 (NLS) and anti-NF-κBp65 (A) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. [γ-32P]ATP (∼5,000 Ci/mmol) used for 5′ end labeling of DNA probes was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech U.K., Limited. Guanidine thiocyanate used for RNA extraction was purchased from Fluka Biochemika (Buchs, Switzerland). TNF-α mRNA expression was measured by a commercial kit (R&D Systems). Acid-equilibrated phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (125:24:1) used for RNA isolation and polymyxin B were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co.

P. aeruginosa culture and processing of culture.

A nonmucoid P. aeruginosa strain originally isolated from the blood of a patient with sepsis in the University Hospital of Patras was used in our study. P. aeruginosa viable cells were maintained in Luria-Bertani broth, and the bacterial concentration was adjusted to 1 × 108 organisms/ml, according to the McFarland standards of bioMerieux Inc. (Hazelwood, Mo.). For the use of whole heat-inactivated and formalin-fixed P. aeruginosa cells, these were mixed with buffered formaldehyde (final concentration, 1.25%) over a 3-h period at room temperature and heat treated at 80°C for 5 min (3). Bacteria were washed in RPMI 1640, resuspended in this medium at the desired concentration and stored at −20°C until they were used for stimulation experiments with monocytes.

Preparation of P. aeruginosa slime GLP.

Extracellular P. aeruginosa product was obtained as previously described (11, 14, 15). Briefly, mid-log-phase bacterial suspensions in Trypticase soy broth (BBL Microbiology, Cockeysville, Md.) were inoculated on cellophane sheets (12 cm in diameter) overlying Trypticase soy agar plates and grown for 18 h in humidified chambers at 37°C. Cells were harvested by washing the cellophane sheets with 0.15 M NaCl, and the extracellular material was extracted by gentle shaking with glass beads. Cellular extracts were precipitated with a mixture of ethanol, sodium acetate, and acetic acid at final concentrations of 80%, 0.26 M, and 0.05 M, respectively. The precipitate was dissolved in distilled water, centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 30 min, and dialyzed three times against 100 volumes of distilled water. The dialysates were centrifuged at 105,000 × g for 3 h to remove LPSs, and the supernatants were lyophilized and kept at −20°C. All stages of extraction were performed at 4°C in the presence of 100 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF).

Analytical methods.

Chemical determination of extracellular products were made on three independently prepared lots in triplicate, and average values were calculated. The protein content was measured by the method of Lowry et al. (29). Total hexose content was determined by the anthrone method (39), uronic acids content was determined by the carbazole reaction as modified by Bitter and Muir (6), total hexozamine content was determined by the method of Belcher et al. (4), and phosphate content was determined by the method of Chen et al. (9). Analysis of the naturally occurring neutral monosaccharides rhamnose, fucose, xylose, mannose, glucose, and galactose was performed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Lichrosorb SI-100 column using derivation with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine and detection of the derivatives at 352 nm. Neutral monosaccharides were liberated from the slime samples by acid hydrolysis with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid at 100°C for 8 to 10 h (11).

Endotoxin contamination in extracellular material was measured by the Limulus amebocyte lysate assay obtained from BioWhittaker Inc. (Walkersville, Md.). The level of endotoxin was 0.15 pg/μg.

Cell culture conditions.

The human monocytic cell line THP-1 (ATCC TIB202; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.), originally isolated from a child with acute leukemia, are mature cells in the monocyte/macrophage lineage, which can produce TNF-α and other cytokines in response to endotoxin (45). These nonadherent cells can be maintained in culture with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.005 mM 2-mercaptoethanol in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. The doubling time of these cells under these conditions is ∼48 h. THP-1 cells were treated with 10 ng of PMA/ml for up to 24 h to induce the monocytes to mature and become macrophage-like. Differentiated macrophages were identified by morphological features and their ability to adhere to plastic. Before experimentation or PMA treatment, THP-1 cells were washed twice with FBS-free RPMI 1640 and resuspended to a concentration of 106 cells/ml. Cell viability was determined to be >90% by the trypan blue dye exclusion method. For cell stimulation, cells were further incubated with or without LPS and/or other stimulants for different time intervals in fresh complete RPMI 1640. Differentiated cells without further stimulation with LPS were used as controls.

Freshly collected leukocyte-rich buffy coats from healthy blood donors were supplied by the St. Andrews General Hospital blood transfusion service (Patras, Greece). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by a density gradient centrifugation over a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient. After washing, cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium. For monocyte differentiation, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were allowed to adhere to plastic six-well plates for 2 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere in complete RPMI 1640 culture medium. After incubation, nonadherent cells were removed by washing twice with warm sterile phosphate-buffered saline (without Mg2+ or Ca2+) (pH 7.4). The adherent population was then scraped and viewed under light microscope for viability and morphology.

Stimulation of human monocytes.

Monocytes were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 40 μg of gentamicin/ml. Monocytes were stimulated with 10 ng to 5 μg of E. coli LPS/ml, 10 ng to 100 μg of P. aeruginosa LPS/ml, 10 ng to 100 μg of slime GLP/ml, 10 viable bacteria per monocyte, or 10 to 1,000 ng of exotoxin A/ml for different time intervals in 24-well polypropylene plates (∼1.5 × 106 cells/well). Supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until determination of TNF-α activity by a specific ELISA was performed. The ELISA was performed in accordance with the manufacturer instructions.

Nuclear extract preparations.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from 107 human monocytes by a modification of the method of Dignam et al. (13). The nuclear protein fraction was collected, and the protein concentration was determined by using the Bradford assay (8).

DNA-protein binding assay.

An electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed to detect DNA-bound NF-κB and AP-1 sites in the human TNF-α promoter. An NF-κB consensus double-stranded oligonucleotide (5-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3) and an AP-1 consensus double-stranded oligonucleotide (5-CGCTTGATGAGTCAGCCGGAA-3) were end labeled (0.25 ng; 2 × 104 cpm) with [γ-32P]ATP. Five micrograms of nuclear extracts was incubated with the labeled oligonucleotide for 30 min at room temperature in the presence of 4 μg of poly(dI-dC) in 15 μl of binding buffer (20% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]). DNA-protein complexes were separated from free probe on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× Tris-borate-EDTA. Radioactive bands were visualized by autoradiography. Binding quantitation was performed by means of ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.) after exposing the gels to a PhosphorImager screen. The specificity of binding was determined by using a 50-fold molar excess of specific and nonspecific cold oligonucleotide.

Identification of the DNA-bound NF-κB was carried out by supershift EMSA with antibodies against p50 and p65 NF-κB subunits (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.). In brief, 5 μg of nuclear extracts was mixed with 2 μg of anti-p50 or anti-p65 antiserum or normal rabbit immunoglobulin for 10 min at room temperature before the addition of the labeled NF-κB probe.

RNA isolation and TNF-α mRNA expression.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from ∼2 × 107 human monocytes by the acid guanidium thiocyanate phenol-chloroform method (10). After treatment with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (2 units/μg of RNA; Promega), RNA samples were analyzed by 1% agarose gel and visualized under UV light to confirm RNA integrity and possible DNA contamination. DNA-free RNA samples (2 μg) were subjected to a specific ELISA for the determination of TNF-α mRNA levels, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Constructs.

pNF-κB-Luc containing five NF-κB domains and pAP-1-Luc containing seven AP-1 domains upstream of the luciferase reporter gene, respectively, were obtained from Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.). The pEGFP-C1 plasmid was obtained from Clontech Laboratories, Inc. (Palo Alto, Calif.).

Transient transfections of THP-1 cells.

THP-1 cells were transfected by electroporation with a gene pulser (ECM399, BTX) at 250 V for 32 to 40 ms. Cells (5 × 106) were mixed with 20 μg of plasmid DNA in 0.25 ml of plain RPMI in 0.4-cm-gap cuvettes. Following transfection, cells were allowed to recover for 48 h prior to stimulation. Cells were then stimulated for 6 h by different stimuli, harvested, and washed twice with PBS (without Mg2+ or Ca2+); the luciferase activity was determined on cell lysates, as described in the luciferase reporter gene assay kit instructions (Roche), using the DT20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale Calif.). The transfection efficiency was determined by coexpression of the green fluorescent protein pEGFP-C1. The luciferase activity was normalized per milligram of total protein (determined by the BCA protein assay reagent [Pierce]) and expressed as relative light units.

RESULTS

Chemical composition and HPLC analysis of slime preparation.

Chemical analysis of the slime preparation is presented in Table 1. As shown in this table, the slime preparation contained mainly neutral monosaccharides and protein, a small amount of uronic acids, and phosphorus. In absolute agreement with previous studies (1, 11), the extracellular product of nonmucoid strains consists of carbohydrate-containing molecules and protein/glycoprotein components.

TABLE 1.

Chemical composition of extracellular slime GLP derived from a P. aeruginosa clinical nonmucoid strain

| Component | % Dry weight of slime GLP (mean ± SEM)a |

|---|---|

| Neutral sugars | 22.33 ± 0.38 |

| Hexosamines | 11.48 ± 0.75 |

| Uronic acid | 6.50 ± 0.22 |

| Protein | 15.80 ± 0.24 |

| Phosphorus | 0.67 ± 0.01 |

Values are the results of three determinations of each component on one batch of each GLP.

In order to further investigate the composition of neutral sugars, the slime preparation was subjected in HPLC analysis as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Table 2, mannose, glycose, and galactose are the main components. It is worth noticing here that in accordance with previous studies (1, 11), the LPS preparation did not contain galactose and mannose, neutral monosaccharides that are present in the slime preparations (see Discussion).

TABLE 2.

HPLC analysis of neutral monosaccharides from slime extracellular product of a smooth clinical nonmucoid strain

| Neutral monosaccharide | % of neutral sugars in slime extracellular product |

|---|---|

| Rhamnose | 8.4 |

| Fucose | 5 |

| Xylose | 4 |

| Mannose | 22 |

| Galactose | 25 |

| Glucose | 36 |

Dose response and kinetics of TNF-α production by P. aeruginosa slime GLP-treated human monocytes.

To study the TNF-α inducing activity of P. aeruginosa components, LPS, GLP, and exotoxin A were added to human peripheral monocyte cultures in increasing concentrations, and supernatants were tested for TNF-α. LPS of E. coli (5 μg/ml) was used as a positive control.

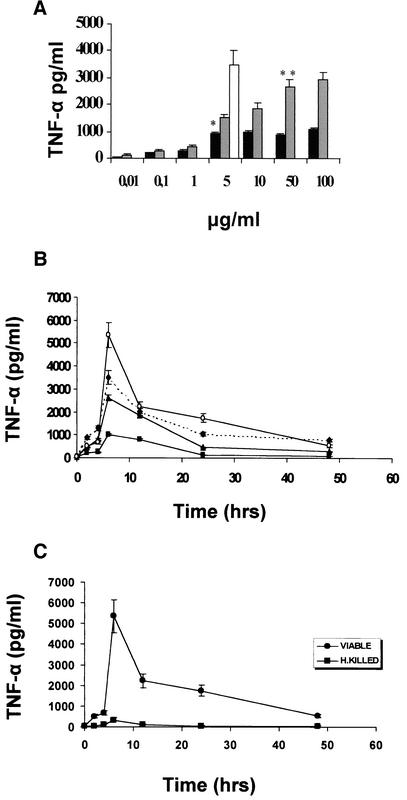

TNF-α was not detected in unstimulated or exotoxin A-stimulated cultures (10 or 100 ng/ml; data not shown). Both P. aeruginosa LPS and GLP were capable of dose-dependent TNF-α release (Fig. 1A). P. aeruginosa LPS induced TNF-α release in doses higher than 100 ng/ml and reached a maximum between 5 and 10 μg/ml, and further increase did not cause more TNF-α production. Slime GLP had a higher inducing activity and was found to be dose dependent in doses between 1 and 50 μg/ml. The optimum dose was found to be between 10 and 50 μg/ml. In following experiments, P. aeruginosa LPS was used at 5 μg/ml, and GLP was used at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. Comparison of the optimum dose concentration for TNF-α induction by each stimulant showed that E. coli LPS caused a 3.5-fold-higher induction than P. aeruginosa LPS, whereas P. aeruginosa GLP caused a 3-fold-higher induction than the homologous LPS. Thus, P. aeruginosa LPS was the weakest stimulant for TNF-α induction compared to E. coli LPS and GLP.

FIG. 1.

(A) TNF-α production by human peripheral monocyte cultures stimulated with increasing doses of P. aeruginosa LPS (▪), slime GLP (▨), or E. coli LPS (□) as a control. Human monocytes were stimulated for 6 h with 10 ng to 100 μg of P. aeruginosa LPS/ml, 10 ng to 100 μg of slime GLP/ml, or 5 μg of E. coli LPS/ml as a control. TNF-α concentrations were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Results are means for triplicate cultures obtained in three different experiments. * and **, P < 0.001. (B) Time course of TNF-α levels in supernatants of human peripheral monocyte cultures stimulated with different components of P. aeruginosa. Cells (1 × 106/ml) were challenged with 5 μg of LPS/ml (▪), 50 μg of slime GLP/ml (▴), or 107 (10 bacteria/monocyte) whole viable (○) P. aeruginosa cells, as described in Material and Methods. E. coli LPS (5 μg/ml) (⧫) was used as a positive control. Results are means for triplicate cultures obtained in three separate experiments. (C) Kinetics of TNF-α production by monocytes stimulated with 107 formalin-fixed heat-killed P. aeruginosa bacteria/ml or 107 whole viable P. aeruginosa bacteria. Culture supernatants for cytokine measurements were removed at the times indicated on the graph. Results are means from two independent experiments.

GLP preincubation with polymyxin B (5 μg/ml) for 2 h before its addition to cell cultures had no effect on TNF-α production, whereas polymyxin B completely abolished TNF-α induction by LPS (data not shown). These results and the results of the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (see Materials and Methods) clearly indicate that the effects of slime GLP preparations are not to be ascribed to endotoxin contamination.

To compare the relative contribution of each P. aeruginosa component to TNF-α induction and kinetics of this induction, fresh human monocytes and macrophage-differentiated human THP-1 monocytic cells (41) were stimulated with viable, heat-killed bacteria, LPS, or P. aeruginosa slime GLP, as described in Materials and Methods. The amount of TNF-α produced was optimum when 10 bacteria/monocyte were used. Higher numbers of bacteria caused a drop in production of TNF-α. Monocyte viability during infection was examined by trypan blue exclusion. E. coli LPS, a well-known stimulant of TNF-α production by human monocytes, was included as a positive control of monocyte activation. As shown in Fig. 1B, detection of TNF-α in culture supernatants starts as early as 2 h, peaks at 6 h, and declines after 24 h. The amount and the time course of TNF-α production are comparable in fresh human monocytes or THP-1 differentiated cells. Slime GLP used at the optimum concentration of 50 μg/ml, as determined by previous experiments, stimulated a high TNF-α production (Fig. 1B) comparable to that of E. coli LPS or viable P. aeruginosa cells. P. aeruginosa LPS (5 μg/ml) was the weakest stimulant of TNF-α production. Heat-killed bacteria stimulated a small amount of TNF-α production (Fig. 1C), suggesting that viable bacteria essentially produce a strong stimulant of TNF-α production. The small amount of TNF-α produced by heat-killed bacteria could be attributed to LPS stimulation that is not affected by heating.

The results are identical from two independent experiments using viable cells from clinical, nonmucoid P. aeruginosa strains isolated from bacteremia. Although the absolute amount of secreted TNF-α varied somewhat among different donors, the relative increase in TNF-α secretion after stimulation with different stimuli was comparable.

P. aeruginosa slime GLP induces TNF-α mRNA production.

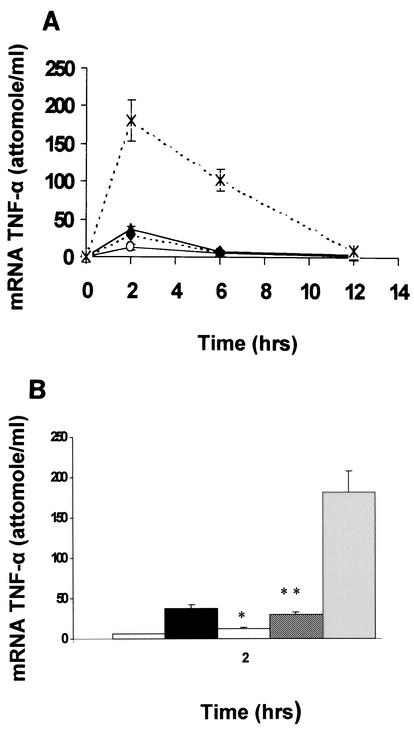

TNF-α production by human monocytes in response to LPS is regulated mainly at the transcriptional level. Having shown a differential effect on TNF-α production between P. aeruginosa slime GLP and LPS, we next addressed whether this difference arises at the level of gene transcription. For this purpose, mRNA was quantitatively analyzed in fresh human monocytes and THP-1 cells stimulated with different stimulants, including P. aeruginosa LPS, slime GLP, and viable P. aeruginosa cells. E. coli LPS was also included. As shown in Fig. 2A, TNF-α mRNA induction by all stimulants followed a comparable time course. Thus, induction began 0.5 h poststimulation, reached a maximum at 2 h, and declined rapidly to levels comparable to unstimulated monocytes by 12 h. Resting monocytes/macrophages expressed very low amounts of TNF-α mRNA. Comparison between the levels of mRNA induction at 2 h revealed that the difference observed between the stimulants was only in the magnitude of induction (Fig. 2B). For instance, TNF-α mRNA level was increased 6-fold upon stimulation with E. coli LPS and P. aeruginosa slime-GLP and 1.5-fold upon stimulation with LPS P. aeruginosa.

FIG. 2.

(A) Time course of mRNA TNF-α isolated from human peripheral monocytes. Cells were stimulated with different components of P. aeruginosa. Monocytes (∼107) were challenged with either 5 μg of E. coli LPS/ml (▴) as a control or with 5 μg of P. aeruginosa LPS/ml (○), 50 μg of P. aeruginosa slime GLP/ml (⧫), or 108 viable P. aeruginosa cells (×), as described in Materials and Methods. Results are representative of four independent experiments. (B) Differential induction of TNF-α mRNA after treatment of human monocytes with (left to right) medium, 5 μg of E. coli LPS/ml, 5 μg of P. aeruginosa LPS/ml, 50 μg of P. aeruginosa slime GLP/ml, or 108 P. aeruginosa viable cells. After 2 h of stimulation, monocytes were lysed and tested for levels of TNF-α mRNA as described in Materials and Methods. Results represent means ± standard deviations for three different experiments. * and **, P < 0.002.

Because the mRNA level induced by slime GLP paralleled that of the proteins, it is conceivable that slime GLP stimulates TNF-α production by regulating transcription and/or the mRNA stability of TNF-α.

P. aeruginosa slime GLP induces NF-κB-dependent transcription.

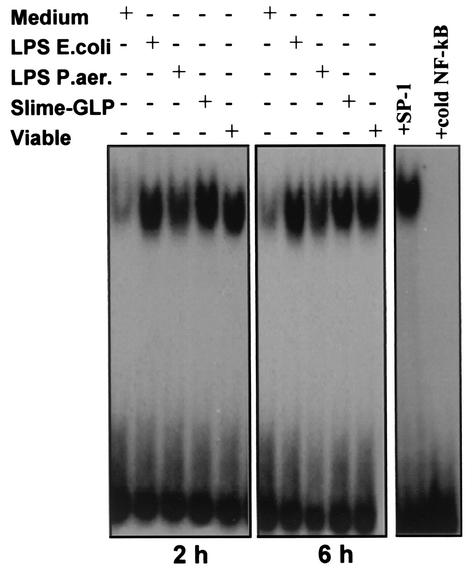

To further elucidate the mechanism(s) by which slime GLP induces the transcriptional activation of the TNF-α gene in peripheral human monocytes and THP-1 cells, we measured the nuclear translocation of two transcriptional activator complexes, NF-κB and AP-1, in response to GLP treatment. Treatment of macrophages with LPS or pharmacologic agents such as phorbol diesters is known to induce NF-κB and AP-1 nuclear translocation. Both NF-κB and AP-1 are involved in the regulation of many genes encoding cytokines and cytokine receptors. To determine their role in TNF-α transcription induced by P. aeruginosa LPS and slime GLP, we performed gel shift assays on nuclear extracts from fresh human monocytes or differentiated THP-1 cells. Cells were stimulated with P. aeruginosa LPS, P. aeruginosa slime GLP, E. coli LPS, and viable P. aeruginosa cells for the indicated time points. In vitro binding assays were performed using the consensus sequence for NF-κB from immunoglobulin G κ.

LPS from E. coli and P. aeruginosa induced NF-κB binding activity in fresh human monocytes. The induction started at 0.5 h and lasted 24 h (data not shown). Interestingly, P. aeruginosa slime GLP caused a much higher induction (fivefold higher) than the corresponding LPS of NF-κB binding activity, comparable with that of E. coli LPS or viable P. aeruginosa cells (Fig. 3). The sequence specificity of the binding was assessed by using a 50-fold molar excess of homologous and heterologous nucleotides as competitors.

FIG. 3.

Activation of NF-κB in response to different components of P. aeruginosa. NF-κB activation was measured by EMSA using radiolabeled oligonucleotide encompassing the NF-κB consensus motif. Human monocytes were stimulated with either 5 μg of LPS/ml, 50 μg of slime GLP/ml, or 108 whole viable P. aeruginosa bacteria (10 bacteria/monocyte) for 2 and 6 h. Untreated cells were used as negative control, while 5 μg of E. coli LPS/ml was used as a positive control. Nuclear extracts and EMSAs were performed as indicated in Materials and Methods. The specificity of the DNA binding was assessed by preincubating extracts (5 μg) with unlabeled specific NF-κB or unspecific SP-1 competitor oligonucleotide at a 50-fold molar excess.

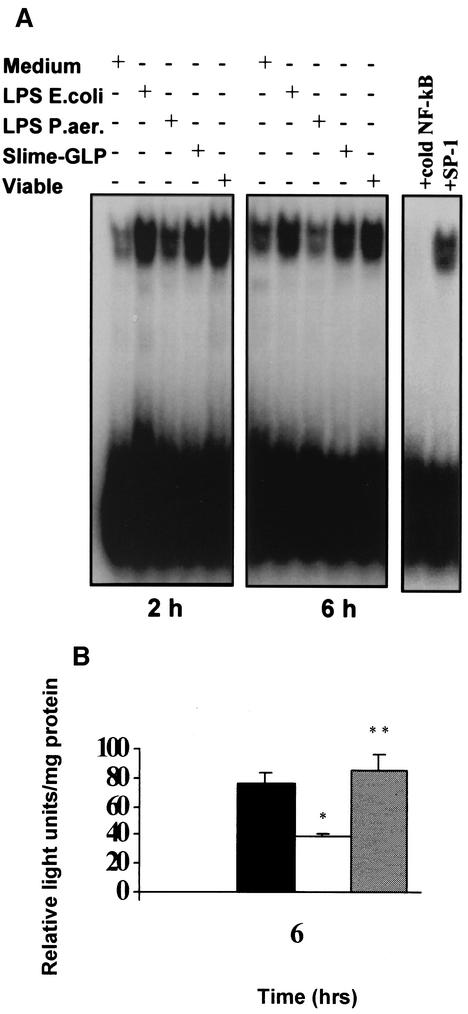

The same pattern of activation of NF-κB-dependent transcription by P. aeruginosa slime GLP, the homologous LPS, and viable P. aeruginosa bacteria was observed in the macrophage-like differentiated THP-1 cell line (Fig. 4A). NF-κB transactivating activity, as measured by the pNF-κB-Luc simian virus 40 reporter construct, corresponded to changes in nuclear NF-κB DNA binding activity. Following transient transfection of THP-1 cells with this construct, cells were stimulated with P. aeruginosa LPS, slime GLP, or E. coli LPS and lysed before the luciferase activity was determined. As shown in Fig. 4B, slime GLP induced an 80-fold increase in luciferase activity in cells transfected with NF-κB reporter plasmid, equal to that induced by E coli LPS. In contrast, P. aeruginosa LPS was a weak inducer.

FIG. 4.

(A) NF-κB binding induction in the human monocytic THP-1 cell line after stimulation with the different components of P. aeruginosa. NF-κB binding was induced by stimulation with either 5 μg of E. coli LPS/ml, 50 μg of slime GLP/ml, or 10 viable P. aeruginosa bacteria/monocyte for 2 and 6 h. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Unstimulated monocytes were used as a negative control. The specificity of the DNA binding was assessed by preincubating extracts (5 μg) with unlabeled specific NF-κB or unspecific SP-1 competitor oligonucleotide at a 50-fold molar excess. (B) NF-κB-dependent transactivation in THP-1 cells stimulated with different components of P. aeruginosa. THP-1 cells were transfected with the pNF-κB-Luc reporter construct. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were treated for 6 h with either medium alone (▥), 5 μg of E. coli LPS/ml (▪), 5 μg of P. aeruginosa LPS/ml (□), or 50 μg of P. aeruginosa slime GLP/ml (▨). Transfection efficiency was monitored by cotransfection of pGEFP-C1 plasmid. Cell lysates were prepared, and aliquots were assayed for luciferase activity. Luciferase activity is expressed as relative light units/mg of total protein. Results are representative of three independent experiments. * and **, P < 0.001.

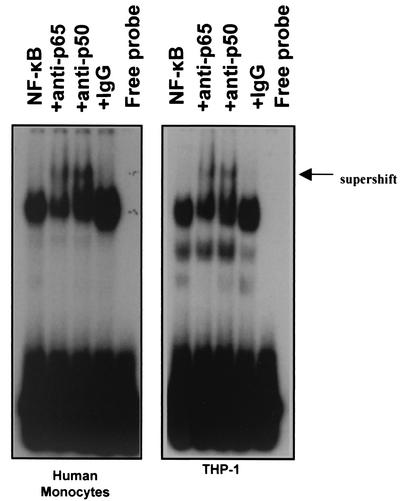

To identify the subunit composition of the slime-induced NF-κB gel shift complexes, supershift experiments were performed using anti-NF-κB antibodies against its p50 and p65 subunits. Nonimmune serum was used as a control. As shown in Fig. 5 (left panel), the anti-p50 antibody reduced binding and produced a supershifted complex more strongly than that against the p65 subunit. Control serum had no effect. This indicates that P. aeruginosa slime GLP induced NF-κB activity of the p50 and p65 subunits. The same subunits were detected in NF-κB complexes induced by all stimuli, including P. aeruginosa slime in THP-1 cells (Fig. 5, right panel).

FIG. 5.

Identification of the NF-κB subunits induced by LPS or slime GLP of P. aeruginosa in monocytes. Nuclear extracts from cells stimulated with either 5 μg of P. aeruginosa LPS/ml or 50 μg of P. aeruginosa slime GLP/ml were preincubated with the indicated antiserum for 20 min at room temperature before the binding reaction with the NF-κB specific probe was performed. The arrow indicates supershift complexes by antibody binding.

P. aeruginosa slime GLP stimulates AP-1-dependent transcription.

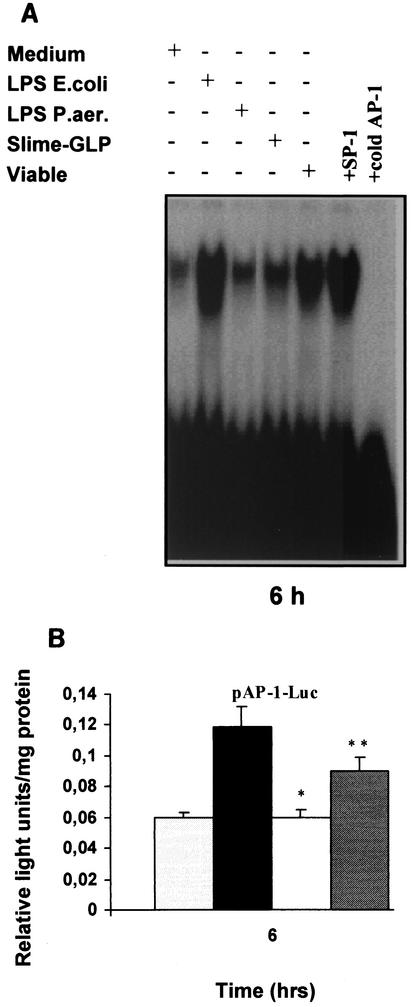

Transcriptional activation of TNF-α promoter in human monocytes remains controversial, with different transcription factors being recruited in response to different stimuli in different cell types. The NF-κB and c-Jun/ATF-2 sites are adjacent in the TNF-α promoter, raising the possibility that they interact in respect to factor binding and transactivation. Cooperation between NF-κB and c-Jun/ATF-2 sites induces TNF-α gene expression in monocytic cells activated by stress (21). Glucocorticoids inhibit TNF-α expression by suppressing transactivation through the same sites (41). Moreover, a number of studies have implicated the AP-1 transcription factor in TNF-α gene transcription induced by cellular components of gram-positive microorganisms (47) or mycoplasmas (19). To further understand the signaling mechanisms involved in the P. aeruginosa slime TNF-α induction, we examined the binding activity of AP-1 induced by P. aeruginosa slime GLP. To this end, fresh human monocytes or THP-1 cells were stimulated by viable P. aeruginosa cells, P. aeruginosa LPS, or P. aeruginosa slime GLP. E. coli LPS was included as a positive control for monocyte activation. In vitro binding assays were performed using AP-1 consensus sequence as probe. As shown in Fig. 6A, AP-1 binding was hardly detected in unstimulated cells. E. coli LPS or viable P. aeruginosa cells caused a strong induction, whereas P. aeruginosa slime GLP caused a 40% increase relative to that of viable P. aeruginosa cells and E. coli LPS. PhosphorImager analysis revealed that P. aeruginosa LPS caused a 1.5-fold induction of AP-1 binding activity above baseline. Even after 2 h of treatment, AP-1 binding was hardly induced by all stimuli. Maximum AP-1 binding was detected between 4 and 6 h of stimulation, corresponding to the time frame of maximum protein production. In contrast, NF-κB binding reached a maximum at 2 h (data not shown). To correlate the in vitro data with in vivo transactivation of AP-1 transcription factor by slime GLP, THP-1 cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid construct containing the AP-1 site driving the expression of luciferase gene. After a 6-h stimulation with P. aeruginosa slime GLP, homologous LPS, or E. coli LPS, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity. As shown in Fig. 6B, P. aeruginosa LPS failed to induce AP-1-dependent transactivation. Slime GLP caused only a 1.5-fold induction, and E. coli LPS caused a 2-fold induction over baseline. All experiments suggested independently that P. aeruginosa slime GLP is a more potent inducer of AP-1-dependent transactivation than its homologous LPS.

FIG. 6.

(A) Activation of AP-1 in response to different components of P. aeruginosa. AP-1 activation was determined by EMSA using a radiolabeled oligonucleotide encompassing the AP-1 consensus motif. Human monocytes were stimulated with either 5 μg of LPS/ml, 50 μg of slime GLP/ml, or 108 viable P. aeruginosa cells for 6 h as described in Materials and Methods. Untreated cells were used as a negative control. The specificity of the DNA binding was assessed by preincubating extracts with an unlabeled specific (AP-1) or unspecific (SP-1) competitor oligonucleotide at a 50-fold molar excess. (B) AP-1-dependent transactivation by different components of P. aeruginosa. THP-1 cells were transfected with the pAP-1 luciferase construct as described in Materials and Methods. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with either (left to right) medium alone, 5 μg of E. coli LPS/ml, 5 μg of P. aeruginosa LPS/ml, or 50 μg of P. aeruginosa slime GLP/ml for 6 h. Cell lysates were prepared, and aliquots were assayed for luciferase activity. Luciferase activity is expressed as relative light units/mg of total protein. Results are representative of three independent experiments. * and **, P < 0.03.

DISCUSSION

Given the proposed central role of TNF-α in the development and progression of P. aeruginosa septic shock, it becomes important to understand the mechanisms by which this bacterium triggers TNF-α production.

The prime pathogenic role of gram-negative bacteria is attributed to LPS virulence factor. The current studies suggest that P. aeruginosa LPS is a weak stimulant in triggering TNF-α production, whereas slime GLP produced by both mucoid and nonmucoid strains is as strong as E. coli LPS, which is a strong TNF-α stimulant, and viable P. aeruginosa bacteria. Our data are in agreement with previous reports indicating that P. aeruginosa LPS is a weak stimulant of TNF-α production not only compared with LPS from other gram-negative bacteria (32, 40) but also compared with LPS of other species of the same genus (50). Heat killing of P. aeruginosa cells abolished their ability to induce TNF-α production, suggesting that either a protein component of the cell wall or a virulence factor produced by viable cells triggers TNF-α production. That other microbial factors produced during an in vitro infection are involved in TNF-α induction cannot be excluded by our experiments. Exotoxin A, as described in the report by Staugas et al. (40) and in our data (not shown), and pyocyanin (46) and exoenzyme S (17) are either weak stimulants or unable to induce TNF-α production. These observations, taken together with the fact that slime is produced early during infection, support our findings that GLP plays a key role in triggering TNF-α induction by human monocytes.

Interestingly, P. aeruginosa slime GLP accounted for more than half of the inducing TNF-α activity of viable P. aeruginosa cells. The rest could be attributed to individual or synergistic action of other cellular and/or extracellular components of P. aeruginosa, most probably porins (12). This is indirectly supported by our experiments. Heat-inactivated porins derived from heat-killed bacteria did not induce TNF-α production. However, in viable bacteria, they acted synergistically with slime to stimulate maximum TNF-α production by human monocytes.

TNF-α expression in LPS-induced human monocytes is mediated at the transcriptional level. Our data are in agreement with previous studies (49) that employed LPS from E. coli as a stimulus. Furthermore, they demonstrate that TNF-α transcription is differentially induced by various LPS, and in the case of P. aeruginosa, extracellular slime GLP and not LPS triggers maximum TNF-α transcription. TNF-α mRNA analysis suggested that the slime GLP-induced increase in TNF-α production occurs, at least in part, at the transcriptional level. Elevated TNF-α transcription in slime GLP-stimulated monocytes was accompanied by the activation of NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors. NF-κB activation induced by slime GLP was comparable to that of viable bacteria. Since P. aeruginosa LPS caused only a minimal induction in NF-κB activity, it is possible that P. aeruginosa slime GLP mediates direct activation of NF-κB. Rapid NF-κB activation after binding of pathogenic bacteria to their target cells has been observed with Listeria (25), Mycobacteria (20), E. coli and Salmonella (16). A number of studies have shown that NF-κB binding induced by LPS in human monocytes involves mainly p50/p65 complexes (43, 49). NF-κB binding induced by P. aeruginosa slime GLP differed quantitatively but not qualitatively from that induced by homologous LPS. This supports the hypothesis that a transactivation effect, which is differentially activated by various stimuli, is mediated by other transcription factors. In fact, P. aeruginosa LPS caused a barely detectable induction of AP-1 binding whereas slime GLP induced a much stronger binding, albeit lower than that induced by viable bacteria or E. coli LPS. Our data demonstrate that slime GLP is a strong stimulant of NF-κB-dependent transcription, which could act in concert with AP-1 or other transcription factors to stimulate maximum transcription.

A number of studies have attempted to identify the molecular structures that trigger maximum TNF-α production by human monocytes. These include the polysaccharide portion of LPS (32), short polymers of β-1,4-linked d-mannuronic acid (26) found in alginate, and defined structures within the lipid A moiety (22). Moreover, evidence supporting a model where aggregated and nonmonomeric molecules (30) or supramolecular configuration of polysaccharides (5) stimulate TNF-α production more effectively have gained more attention. In the case of P. aeruginosa, LPS and slime GLP do not differ substantially in their chemical composition. Differences in chemical composition are quantitative rather than qualitative. An important structural difference that is directly linked to lethality caused by slime GLP (31) is the presence of mannose in slime but not in the homologous LPS. The macrophage mannose receptor is a pattern recognition molecule that links innate and adaptive immunity (18). Susceptibility to antibiotics (2) or in phage-mediated lysis (35) correlates with the presence of mannose in GLP, supporting a role for mannose in receptor-mediated functions. Because P. aeruginosa slime possesses mitogenic properties for human lymphocytes, it is possible that the presence of mannose in the supramolecular configuration of extracellular slime GLP causes aggregation of as-yet-undefined receptors on T cells, causing proliferation, or on monocytes, leading to TNF-α production.

Interaction of P. aeruginosa slime GLP with other receptors on the monocyte surface, such as CD14 (30), or with a member(s) of the recently described family of Toll-like receptors (36), is an intriguing possibility. Since both receptors have broad specificity, it remains to be elucidated whether specific components of P. aeruginosa GLP or their supramolecular configuration interact with these receptors and stimulate TNF-α production.

In conclusion, our data identify a potent virulence factor in all P. aeruginosa strains and suggest a molecular mechanism by which P. aeruginosa slime GLP induces TNF-α production by human monocytes. Identification of the receptor molecule(s) on the monocyte surface that binds P. aeruginosa slime GLP and dissection of the underlying molecular mechanisms would enhance our understanding of, and ability to promote, the host defense against pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank the personnel of St. Andrews General Hospital Blood Transfusion Service (Patras, Greece) for their assistance with buffy coat isolation and D. T. Boumpas and S. M. Najjar for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the University of Patras Research Committee (Karatheodoris 2000).

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Anastassiou, E. D., A. C. Mintzas, C. Kounavis, and G. Dimitracopoulos. 1987. Alginate production by clinical nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:656-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arsenis, G., and G. Dimitracopoulos. 1986. Chemical composition of the extracellular slime glycolipoprotein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its relation to gentamicin resistance. J. Med. Microbiol. 21:199-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banck, G., and A. Forsgren. 1999. Many bacterial species are mitogenic for human blood B lymphocytes. Scand. J. Immunol. 8:347-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belcher, R., A. J. Nutten, and C. M. Sambrook. 1954. The determination of glycosamine. Analyst (London) 79:201-208. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berntzen, G., T. H. Flo, A. Medvedev, L. Kilaas, G. Skjak-Braek, A. Sundan, and T. Espevik. 1998. The tumor necrosis factor-inducing potency of lipopolysaccharide and uronic acid polymers is increased when they are covalently linked to particles. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:355-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bitter, T., and H. M. Muir. 1962. A modified uronic acid carbazole reaction. Anal. Biochem. 4:330-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodey, G. P., R. Bolivar, V. Fainstein, and L. Jadeja. 1983. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev. Infect. Dis. 5:279-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, P. S., T. Y. Toribara, and H. Warner. 1956. Microdetermination of phosphorus. Anal. Chem. 28:1756-1758. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chomczynski, P., and N. Sacchi. 1987. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 162:156-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christofidou, M., N. K. Karamanos, A. C. Mintzas, G. Dimitracopoulos, and E. D. Anastassiou. 1993. Occurrence of a 29 kDa polysaccharide in the slime layer of both smooth and rough strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Biochem. 25:313-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cusumano, V., M. A. Tufano, G. Mancuso, M. Carbone, F. Rossano, M. T. Fera, F. A. Ciliberti, E. Ruocco, R. A. Merendino, and G. Teti. 1997. Porins of Pseudomonas aeruginosa induce release of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 by human leukocytes. Infect. Immun. 65:1683-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dignam, J. D., R. M. Lebovitz, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:1475-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimitracopoulos, G., and P. F. Bartell. 1980. Slime glycolipoproteins and the pathogenicity of various strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in experimental infection. Infect. Immun. 30:402-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimitracopoulos, G., J. W. Sensakovic, and P. F. Bartell. 1974. Slime of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: in vivo production. Infect. Immun. 10:152-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eaves-Pyles, T., C. Szabo, and A. L. Salzman. 1999. Bacterial invasion is not required for activation of NF-κB in enterocytes. Infect. Immun. 67:800-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epelman, S., T. F. Bruno, G. G. Neely, D. E. Woods, and C. H. Mody. 2000. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S induces transcriptional expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Infect. Immun. 68:4811-4814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser, I. P., H. Koziel, and R. A. Ezekowitz. 1998. The serum mannose-binding protein and the macrophage mannose receptor are pattern recognition molecules that link innate and adaptive immunity. Semin. Immunol. 10:363-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia, J., B. Lemercier, S. Roman-Roman, and G. Rawadi. 1998. A Mycoplasma fermentans-derived synthetic lipopeptide induces AP-1 and NF-κB activity and cytokine secretion in macrophages via the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 273:34391-34398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giri, D. K., R. T. Mehta, R. G. Kansal, and B. B Aggarwal. 1998. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex activates nuclear transcription factor-κB in different cell types through reactive oxygen intermediates. J. Immunol. 161:4834-4841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guha, M., W. Bai, J. L. Nadler, and R. Natarajan. 2000. Molecular mechanisms of tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression in monocytic cells via hyperglycemia-induced oxidant stress-dependent and independent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 275:17728-17739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo, L., K. B. Lim, J. S. Gunn, B. Bainbridge, R. P. Darveau, M. Hackett, and S. I. Miller. 1997. Regulation of lipid A modifications by Salmonella typhimurium virulence genes phoP-phoQ. Science 276:250-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hambleton J., S. L Weinstein, L. Lem, and A. L. DeFranco. 1996. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:2774-2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han, J., T. Brown, and B. Beutler. 1990. Endotoxin-responsive sequences control cachectin/tumor necrosis factor biosynthesis at the translational level. J. Exp. Med. 171:465-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hauf, N., W. Goebel, F. Fiedler, Z. Sokolovic, and M. Kuhn. 1997. Listeria monocytogenes infection of P388D1 macrophages results in a biphasic NF-κB (RelA/p50) activation induced by lipoteichoic acid and bacterial phospholipases and mediated by IκBα and IκBβ degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:9394-9399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jahr, T. G., L. Ryan, A. Sundan, H. S. Lichenstein, G. Skjak-Braek, and T. Espevik. 1997. Induction of tumor necrosis factor production from monocytes stimulated with mannuronic acid polymers and involvement of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, CD14, and bactericidal/permeability-increasing factor. Infect. Immun. 65:89-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jongeneel, C. V. 1992. The molecules and their emerging role in medicine, p. 539-559. In B. Beutler (ed.), Tumor necrosis factors. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 28.Kuprash, D. V., I. A. Udalova, R. L. Turetskaya, D. Kwiatkowski, N. R. Rice, and S. A. Nedospasov. 1999. Similarities and differences between human and murine TNF promoters in their response to lipopolysaccharide. J. Immunol. 162:4045-4052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowry, O., N. J. Rosebrough A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGinley, M. D., L. O. Nahri, M. J. Kelley, E. Davy, J. Robinson, M. F. Rohde, S. D. Wright, and H. S. Linchenstein. 1995. CD14: physical properties and identification of an exposed site that is protected by lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 270:5213-5218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orr, T., L. H. Koepp, and P. F. Bartell. 1982. Carbohydrate mediation of the biological activities of the glycolipoprotein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:2631-2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otterlei, M., A. Sundan, G. Skjak-Braek, L. Ryan, O. Smidsrod, and T. Espevik. 1993. Similar mechanisms of action of defined polysaccharides and lipopolysaccharides: characterization of binding and tumor necrosis factor alpha induction. Infect. Immun. 61:1917-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papamichail, M., G. Dimitracopoulos, G. Tsokos, and J. Papavassiliou. 1980. A human lymphocyte mitogen extracted from the extracellular slime layer of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 141:686-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pier, G. B., W. J. Matthews, Jr., and D. D Eardley. 1983. Immunochemical characterization of the mucoid exopolysaccharide of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Infect. Dis. 147:494-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reese, J. F., G. Dimitracopoulos, and P. F. Bartell. 1974. Factors influencing the adsorption of bacteriophage 2 to cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Virol. 13:22-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rock, F. L., G. Hardiman, J. C. Timans, R. A. Kastelein, and J. F. Bazan. 1998. A family of human receptors structurally related to Drosophila Toll. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:588-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sensacovic, J. W., and P. F. Bartell. 1974. The slime of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: biological characterization and possible role in experimental infection. J. Infect. Dis. 129:101-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shakhov, A. N., M. A. Collart, P. Vassalli, S. A. Nedospasov, and C. V. Jongeneel. 1990. Kappa B-type enhancers are involved in lipopolysaccharide-mediated transcriptional activation of the tumor necrosis factor alpha gene in primary macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 171:35-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spiro, R. G. 1966. Analysis of sugars found in glycoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 8:3-26. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staugas, R. E., D. P. Harvey, A. Ferrante, M. Nandoskar, and A. C. Allison. 1992. Induction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1) by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and exotoxin A-induced suppression of lymphoproliferation and TNF, lymphotoxin, gamma interferon, and IL-1 production in human leukocytes. Infect. Immun. 60:3162-3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steer, J. H., K. M. Kroeger, L. J. Abraham, and D. A. Joyce. 2000. Glucocorticoids suppress tumor necrosis factor alpha expression by human monocytic THP-1 cells by suppressing transactivation through adjacent NF-kappa B and c-Jun activating transcription factor-2 binding sites in the promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18432-18440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tracey, K. J., and A. Cerami. 1994. Tumor necrosis factor: a pleiotropic cytokine and therapeutic target. Annu. Rev. Med. 45:491-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trede N. S., A. V. Tsytsykova, T. Chatila, A. E. Goldfeld, and R. S Geha. 1995. Transcriptional activation of the human TNF-alpha promoter by superantigen in human monocytic cells: role of NF-kappa B. J. Immunol. 155:902-908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai, E. Y., J. V. Falvo, A. V. Tsytsycova, A. K. Barczak, A. M. Reimold, L. H. Glimcher, M. J. Fenton, D. Gordon, I. F. Dunn, and A. E. Goldfeld. 2000. A lipopolysaccharide-specific enhancer complex involving Ets, Elk-1, Sp1, and CREB binding protein and p300 is recruited to the tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6084-6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuchiya, S., Y. Kobayashi, Y. Goto, H. Okumura, S. Nakae, T. Konno, and K. Tada. 1982. Induction of maturation in cultured human monocytic leukemia cells by a phorbol diester. Cancer Res. 42:1530-1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ulmer, A. J., J. Pryjma, Z. Tarnok, M. Ernst, and H. D. Flad. 1990. Inhibitory and stimulatory effects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pyocyanine on human T and B lymphocytes and human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 58:808-815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vallejo J. G., P. Knuefermann, D. L Mann, and N. Sivasubramanian. 2000. Group B Streptococcus induces TNF-alpha gene expression and activation of the transcription factors NF-kappa B and activator protein-1 in human cord blood monocytes. J. Immunol. 165:419-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Varey, A. M., A. Cooke, G. Dimitrocopoulos, and M. Papamichail. 1984. Mitogenic effects of glycolipoprotein extract from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 56:431-437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao, J., N. Mackman, T. S. Edgington, and S. T. Fan. 1997. Lipopolysaccharide induction of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter in human monocytic cells. Regulation by Egr-1, c-Jun, and NF-kappaB transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 272:17795-17801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zughaier, S. M., H. C. Ryley, and S. K Jackson. 1999. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Burkholderia cepacia is more active than LPS from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in stimulating tumor necrosis factor alpha from human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 67:1505-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]