Abstract

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive facultative intracellular food-borne pathogen that can cause severe infections in humans and animals. We have recently adapted signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis (STM) to identify genes involved in the virulence of L. monocytogenes. A new round of STM allowed us to identify a new locus encoding a protein homologous to AgrA, the well-studied response regulator of Staphylococcus aureus and part of a two-component system involved in bacterial virulence. The production of several secreted proteins was modified in the agrA mutant of L. monocytogenes grown in broth, indicating that the agr locus influenced protein secretion. Inactivation of agrA did not affect the ability of the pathogen to invade and multiply in cells in vitro. However, the virulence of the agrA mutant was attenuated in the mouse (a 10-fold increase in the 50% lethal dose by the intravenous route), demonstrating for the first time a role for the agr locus in the virulence of L. monocytogenes.

Listeria monocytogenes is a gram-positive bacterium widespread in nature and responsible for sporadic severe infections in humans and other animal species (see reference 2 and references therein). This organism is a facultative intracellular parasite capable of invading most host cells, including epithelial cells (13), hepatocytes (7, 14), fibroblasts (20), endothelial cells (8), and macrophages (22). Each step of the intracellular parasitism by L. monocytogenes is dependent upon the production of virulence factors (4). The major virulence genes (hly, plcA, plcB, mpl, actA, inlA, and inlB) are clustered into two distinct loci on the chromosome and are controlled by a single pleiotropic regulatory activator, PrfA, which is required for virulence (see reference 33 for a review).

We have recently adapted signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM) to L. monocytogenes (1). In this work, we performed a new STM screening with the liver as a target organ (see Materials and Methods for details). By this procedure, we have identified a transposon insertion in a gene, designated agrA, encoding a protein homologous to the response regulator AgrA of Staphylococcus aureus. The two-component regulatory system of which AgrA is a part has been extensively studied in S. aureus and has been shown to control the production of virulence factors (see reference 27 for a review). The agr locus of S. aureus expresses two primary divergent transcripts. RNAII encodes a two-component system, AgrA/AgrC, which recognizes the agrD-encoded secreted autoinducing octapeptide (AIP), and AgrB, which is thought to act in the posttranslational processing and secretion of AIP. The second major transcript, RNAIII, acts as the effector molecule of the agr locus. Finally, a third, short transcript, RNAI, has also been described as encoding AgrA. Upon accumulation of sufficient quantities of AIP in the growth medium, signaling via AgrA/AgrC increases transcription of both RNAII and RNAIII, resulting in the down-regulation of exponential-phase proteins, such as the cell surface-associated protein A, and the increased expression of postexponentially secreted proteins, such as enterotoxins B, C, and D, involved in bacterial virulence (18). AgrA, which is also required for agr activation and corresponds to the response regulator, does not appear to bind directly to the agr promoters but may interact with SarA, the product of a separate genetic locus, to mediate activation (25, 26). AgrC acts as a sensor for the autocrine signal provided by the AIP derived from AgrD and responds by autophosphorylation on a histidine residue.

The genome of L. monocytogenes contains 16 putative response regulators constituting two-component regulatory systems (16). This number is similar to that in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli (taking into account the genome sizes). In Streptococcus pneumoniae, thirteen putative two-component regulatory systems have been identified, and a systematic gene inactivation approach showed that most of them (8 of 13) were important for bacterial virulence (31). Two of the 16 putative two-component systems of L. monocytogenes have been studied experimentally: the cheY/cheA (11) and lisR/lisK (5) systems. Transposon insertion in the promoter region of the che operon reduced flagellin expression and affected the ability of L. monocytogenes to attach to the mouse fibroblast cell line 3T3 (11). The LisR/LisK system was shown to be involved in stress tolerance, and inactivation of lisRK resulted in a slight decrease of bacterial virulence (5). A more recent study described the inactivation of five putative two-component systems (19). One of them corresponded to the previously studied LisR gene (lmo1377), and the four others corresponded to lmo2422, lmo2501, lmo2583, and lmo2678. A preliminary evaluation of the effects of the mutations on bacterial virulence, performed with mice, showed that only the inactivation of the LisR gene reduced bacterial virulence by the different routes of infection used (5, 19).

In the present work, we show that inactivation of the L. monocytogenes agrA gene influences protein secretion and attenuates the virulence of the bacterium in the mouse without affecting the growth of the bacterium in cell cultures. Functional implications of the role of this locus in L. monocytogenes are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and DNA techniques.

E. coli recombinants were grown in Luria-Bertani medium and L. monocytogenes in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C. The wild-type virulent strain of L. monocytogenes EGD belongs to the serovar 1/2a (23). EGD-e was transformed with the different recombinant plasmids by electroporation as previously described (1). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: kanamycin, 50 μg ml−1; erythromycin (Em), 5 μg ml−1.

Chromosomal DNA, plasmid isolation, restriction enzyme analyses, and PCR amplifications were performed as previously described (1). Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Proligo (Paris, France). The AmpliTaq DNA polymerase of Thermus aquaticus from Finnzymes OY (Espoo, Finland) was used.

Screening procedure.

STM was performed as described previously with L. monocytogenes strain EGD-e (1). Pools of 48 mutants of L. monocytogenes were assembled, and each pool was injected into mice at a dose of 106 bacteria per mouse. In the present screening, the liver was chosen as a target organ. At this dose, the average number of bacteria reached >108 per liver at day 4, i.e., 1,000-fold higher than that in the brain. In these conditions, each mutant within a pool is represented up to 2 × 106 times, thus improving the sensitivity of the screening. Infected livers were collected at day 4 and homogenized and cultured in BHI-Em (1).

Southern blot analysis.

L. monocytogenes chromosomal DNA was prepared as previously described in reference 1. Briefly, chromosomal DNA was digested with BglII and Sau3AI and transferred onto nylon Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham) under denaturing conditions. Hybridizations were realized under high stringency conditions, including prehybridization at 65°C for 3 h in 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-0.05% Régilait buffer. Hybridization was carried out overnight at 65°C in 6× SSC-0.1% SDS-0.05% Régilait buffer, with two 30-min washes at room temperature in 2× SSC-0.1% SDS followed by two 30-min washes at 65°C in 0.2× SSC-0.1% SDS. Hybridization was detected on Hyperfilm-MP films (Amersham).

The probe used corresponds to a 0.7-kb internal portion of the plasmid pAT113 located between oriRK2 and the multiple cloning site. The fragment was (i) amplified by PCR with primer RK2-F and the forward primer of mp18/pUC18 (sequencing primer 1211; NE Biolabs), (ii) digested with HindIII (downstream of the multiple cloning site) to remove the region of the polylinker, and (iii) 32P-labeled using the megaprime kit (Amersham).

Transduction.

The transposon-inactivated agrA gene was transferred into a wild-type background by generalized transduction with phage LMUP35 (17). Lysates of LMUP35 were prepared with the agrA mutant strain, and transduction into wild-type EGD-e was carried out as described previously (24). The transductants were checked by PCR analysis.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from L. monocytogenes cultures grown overnight in BHI broth at 37°C as described in reference 3. The primers used to amplify the mRNA corresponding to the different genes from EGD by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) are listed below. We used the procedure described in the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR system kit (Life Technologies, Paisley, Scotland). Prior to RT-PCR, total RNA samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with DNase I (RNase free; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) to eliminate any DNA contamination. The following pairs of primers were used: agrA forward primer, 5′-CGAATGCCTACACATCAAGGTA-3′; agrA reverse primer, 5′-TCACCACACCTTTTGTCGTATC-3′; agrB forward primer, 5′-AAAGTCCCTTTGTCAGAAAGAATG-3′; agrB reverse primer, 5′-CACCTGAAACAAAGATCCTACCA-3′; agrC forward primer, 5′-ATTAATACGGCAACCAACGAAC-3′; and agrC reverse primer, 5′-AAATCGGTGGCATATTTACTGG-3′.

Real-time quantitative Taqman PCR assay. (i) Extraction of L. monocytogenes RNA.

Bacteria were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.4. Cells were broken in a solution of Trizol (1 ml; Life Technologies) with mini glass beads by using a Bead Beater apparatus (Polylabo) set at maximum speed. RNA was extracted with 300 ml of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol. After 10 min of centrifugation at 13,000 × g, the aqueous phase was transferred to a tube containing 270 ml of isopropanol. Total RNA was then precipitated overnight at 4°C and washed with 1 ml of a 75% ethanol solution before suspension in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. Contaminating DNA was removed by digestion with DNase I according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Roche).

(ii) Real-time quantitative PCR.

The assay was carried out with the ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system by using Taqman Universal PCR master mix (PE Applied Biosystems). The primers were designed by using the Primer Express software and obtained from PE Applied Biosystems. The sequences were as follows: agrA forward primer, 5′-AATGTTTTGAATTAGCTCAGGAAA-3′; agrA reverse primer, 5′-ACTCCGCATGTGTTGTAATAAAAATAA-3′; agrB forward primer, 5′-AGGTACATTTGGATTTATACTGCTCAAC-3′; agrB reverse primer, 5′-TCTTCACCGATTAAAGGCAAACT-3′; agrC forward primer, 5′-ATTGACAAGATTTCGATGGATAGTATAGATT-3′; agrC reverse primer, 5′-CACAAGTTAACGCCGCTTCA-3′; gyr forward primer, 5′-AAATGCGGACATCATTCCTAGACT-3′; gyr reverse primer, 5′-TTTAACCCGTCACGAACATCAG-3′; 16S forward primer, 5′-CATAATGGTGCAAAACCATCTGA-3′; and 16S reverse primer, 5′-TTGGTTATGGAATTTTTCCATGATGATAC-3′.

RT-PCR experiments were carried out with 1 μg of RNA and 2.5 pmol of primers specific for agr, gyr, and 16S in a volume of 8 μl. After denaturation at 65°C for 10 min, 12 μl of the mixture containing 2 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate (25 mM), 4 μl of 4× buffer, 2 μl of dithiothreitol, 1 μl of RNasin (Promega), and 1.5 μl of Superscript II (Invitrogen) was added. Samples were incubated for 60 min at 42°C, heated at 75°C for 15 min, and then chilled on ice. Samples were diluted with 40 μl of H2O and stored at −20°C. PCR conditions were identical for all reactions. The 25-μl reaction mixtures consisted of 12.5 ml of PCR master mix (PE Applied Biosystems) containing Sybr Green, 4 μl of template, and 5 pmol of each primer. The reactions were carried out in sealed tubes. Results were normalized to the amount of gyr mRNA and 16S (16S rRNA). The gyr and 16S genes were chosen as standards because they had been previously shown to be constant under different conditions in several gram-positive bacteria. Our assays confirmed that these two reporter genes also remained constant in L. monocytogenes under all the growth conditions used here (for the same concentrations of RNA under different conditions of growth, we obtained the same amounts of mRNA for gyr and 16S; data not shown). All the experiments have been done in triplicate.

Sequence analysis and identification of transposon insertion site in Listeria genome. (i) Inverse PCR.

The DNA sequence flanking the transposon was determined as described previously (1). Chromosomal DNA was digested with Sau3A. Digestion products were ligated, generating circular molecules containing either the right end or the left end of Tn1545. DNA was amplified by PCR with the primers SeqL (5′-GGATAAATCGTCGTATCAAAG-3′) and SeqR (5′-CGTGAAGTATCTTCCTACAGT-3′).

(ii) PCR sequencing.

The PCR products were sequenced with the automated ABI Prism 310 sequencer (Perkin Elmer; Applied Biosystems) using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit. Sequences were analyzed with the Sequence Navigator software program (Perkin Elmer). Similarity searches were then performed via the Internet with BLAST software (1) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information home page (www.ncbi.nlm.gov./BLAST/) by launching the sequences in the complete 2,900,000-bp Listeria genome database (BLASTn search). The sequences of the identified open reading frames (ORFs) were then launched in the general databases (nonredundant BLASTp search).

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Proteins from culture supernatants and total bacterial extracts were prepared as follows. Fractions of bacterial cultures grown in BHI rich medium at different OD600s were centrifuged (exponential phase, OD600 of 0.6; stationary phase, OD600 of 10). Supernatants were passed through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter (Millipore) and further concentrated with ultrafree columns (Millipore) with a cutoff of 30 kDa. Samples were finally suspended in 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer (130 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 1% SDS, 7% 2-β-mercaptoethanol, 7% sucrose, 0.01% bromophenol blue). The bacterial pellets were suspended in cold water, and bacteria were disrupted by using a Fastprep FP120 apparatus (BIO101, La Jolla, Calif.) with three pulses of 30 s at a speed rating of 6.5. After centrifugation for 3 min at 8,000 × g, lysates were collected and suspended in 1× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Electrophoresis and Western blotting were carried out as described previously (15) in SDS-8% polyacrylamide minigels (Mini Protean II; Bio-Rad). Silver staining of gels was adapted from that described in reference 32.

Nitrocellulose sheets were probed either with anti-listeriolysin O (anti-LLO) monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) SE1 and SE2 (9) or with polyclonal anti-ActA or anti-PlcB antibodies, along with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Antibodies were used at a final dilution of 1:1,000, except for anti-PlcB (1:200). Antibody binding was revealed by adding 0.05% diaminobenzidine-tetrahydrochloride (Sigma) and 0.03% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma).

Culture of cell lines.

The human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2 (ATCC HTB37) and the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG-2 (ATCC HB 8065, kindly provided by S. Dramsi and P. Cossart, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) were propagated as previously described (7) in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were seeded at ca. 2 × 105 cells cm−2 in 24-well tissue culture plates (Falcon). Monolayers were used 24 h after seeding.

Invasion assays.

The invasion assays were carried out essentially as described previously (15). Briefly, cells were inoculated with bacteria at a multiplicity of infection of approximately 100 bacteria per cell. The cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C to allow the adherent bacteria to enter. Cells were washed six times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) medium and inoculated with fresh Dulbecco modified Eagle medium-fetal bovine serum. At 2, 3, and 4 h, cells were washed three times in PBS medium containing MgCl2 and CaCl2 and processed for counting of infecting bacteria. For processing, cells were lysed by adding a solution of 0.1% Triton X-100. The titer of viable bacteria released from the cells was determined by spreading bacteria onto BHI plates. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and repeated twice.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages from BALB/c mice were cultured as described previously (6) and then infected as follows: bacteria grown overnight were diluted in cell culture medium to give a multiplicity of infection of one bacteria per macrophage. Bacteria were allowed to adhere to cells by incubation on ice for 15 min and then to enter cells by placing cells at 37°C for 15 min. After the medium was removed, the infected cells were washed six times with 1 ml of PBS medium containing MgCl2 and CaCl2 and once with RPMI medium to remove extracellular bacteria. The cells were then replaced in fresh medium and incubated at 37°C.

Infection of mice.

Specific-pathogen-free 6- to 8-week-old female Swiss mice (Janvier, Le Genest St. Isle, France) were used. Bacteria were grown for 18 h in BHI broth, centrifuged, appropriately diluted in 0.15 M NaCl, and inoculated (0.5 ml) intravenously (i.v.) into mice via the lateral tail veins. Groups of five mice were challenged i.v. with various doses of bacteria, and mortality was monitored for 10 days. The virulence of the mutant was estimated by using the 50% lethal dose (LD50) with the Probit method (10).

Kinetics studies.

Thirty mice per mutant were inoculated i.v. in the lateral tail veins. At days 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 10, groups of five mice were sacrificed and the organs (spleens, livers, and brains) were aseptically removed and separately homogenized in 0.15 M NaCl. Bacterial numbers in organ homogenates were determined at various intervals on BHI plates containing Em. Five hundred microliters of bacterial suspension containing 2 × 104 bacteria were injected per mouse.

In all the assays, bacteria were stored in 1-ml fractions at −80°C after growth and the number of bacteria per milliliter in each defrosted culture was determined before and after inoculation.

RESULTS

Isolation and characteristics of the agrA mutant of L. monocytogenes.

Among the candidates identified by this new STM screen, one mutant contained a Tn1545 insertion in a gene, designated agrA by analogy to the agr two-component regulatory system of S. aureus. The particular attention devoted recently to the role of two-component systems in the control of bacterial pathogenesis (30), and the fact that the agr system of S. aureus is one of the most studied two-component systems in gram-positive organisms, prompted us to focus, in the present work, on the properties of this mutant.

Characterization of the mutant.

The transposon insertion site in the chromosome of the agrA mutant was determined as described previously (1). The Tn1545 insertion occurred 276 bases downstream of the first ATG of agrA, thus leading to the complete inactivation of its expression. We first checked by Southern blot hybridization that the mutant corresponded to a single Tn1545 insertion. Then, in order to eliminate possible additional mutations in other regions of the chromosome, the transposon-inactivated agrA gene was transferred into a wild-type background by generalized transduction (17). All further analyses were performed with the transduced strain.

Organization of the agr locus of L. monocytogenes and transcriptional analysis. (i) In silico analyses.

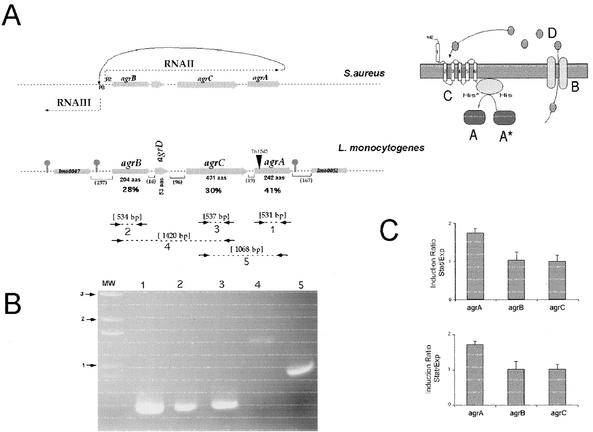

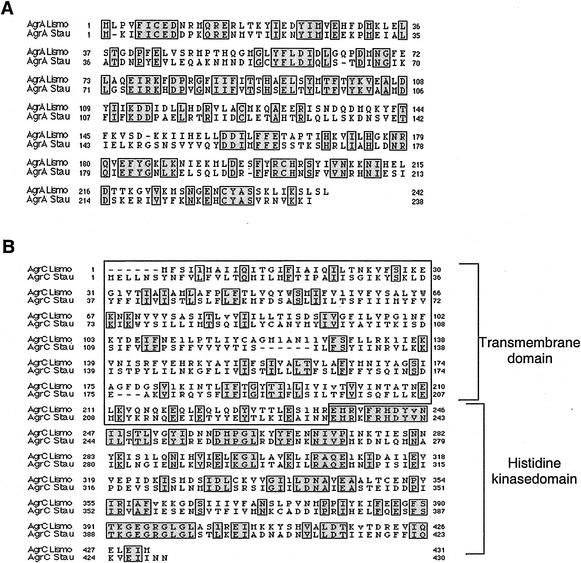

Analysis of the L. monocytogenes genome (16) revealed that it contains a complete agr locus, comprising the four genes agrB, agrD, agrC, and agrA in the same arrangement found in S. aureus (Fig. 1). The agrB-encoded protein of L. monocytogenes shares only 28% identity with AgrB of S. aureus. AgrC of L. monocytogenes shares 30% identity with AgrC of S. aureus. Between L. monocytogenes agrB and agrC, a short ORF encodes a putative AgrD polypeptide of 53 amino acids from which an analogue to the AIP of S. aureus may derive. Aside from comparable sizes, no significant similarity was found between the two polypeptides. This observation concurs with the fact that the AgrD polypeptides are highly variable among various S. aureus isolates (18). With 41% identity between those of L. monocytogenes and S. aureus, the AgrA proteins were the most conserved (Fig. 2). AgrB, AgrD, AgrC, and AgrA are highly conserved in the other pathogenic serogroup, that of L. monocytogenes 4b (preliminary sequence data were obtained from the Institute for Genomic Research website at http://www.tigr.org). The AgrA, AgrC, and AgrD protein sequences were identical in the strains. AgrB of L. monocytogenes 4b is 14 residues shorter than its counterpart in EGD-e, but the conserved portions had 99% amino acid identity. The loci were comparably organized and conserved in the nonpathogenic species L. innocua (over 90% identity).

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the agr locus and transcriptional analysis. (A) Genetic organization of the agr locus. (Upper panel) agr locus of S. aureus. The grey arrows indicate the orientations and approximate sizes of the different genes. The dotted lines ending in arrows indicate the two main divergent transcripts RNAII and RNAIII. To the right, a schematic representation of the various components of the agr locus is shown, with letters representing the proteins encoded A, AgrA; B, AgrB; C, AgrC; D, AgrD; asterisk, phosphorylated group; P2 and P3, promoters of RNAII and RNAIII, respectively. (Lower panel) agr locus of L. monocytogenes. The arrows indicate approximate sizes and orientations of the different genes. The predicted length of each protein is indicated below (in amino acids [aas]). The stop sign-shaped symbols indicate putative transcription terminators. The values in percentages below agrB, agrC, and agrA indicate the percentage of amino acid identity between the L. monocytogenes and S. aureus orthologues encoded by the genes of the agr loci. Numbers between parentheses indicate the sizes (in base pairs) of the intergenic regions. The site of Tn1545 insertion is represented by an inverted black triangle. (B) Transcriptional analysis by RT-PCR. The dotted lines enclosed by arrows in the lower half of panel A indicate the positions of the primers and PCR products used in the RT-PCR analysis. The amplified products, numbered 1 to 5, were subjected to Tris acetate-EDTA-agarose gel electrophoresis. The arrows preceded by numbers (in kilobases) to the left of the panel correspond to the molecular weight (MW) DNA ladder. (C) Expression of the agr genes in stationary (Stat) and exponential (Exp) phases. The expression was measured by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. The amount of agr mRNA relative to that of the normalizing gene gyr (upper panel) and the 16S gene (lower panel) was determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR with bacteria grown in BHI in the exponential or stationary phase of growth. The amounts of gyr mRNA and 16S rRNA were constant under these conditions (data not shown). The values shown are means of results from three assays; the error bars indicate the standard deviations.

FIG. 2.

Multiple alignment of AgrA (A) and AgrC (B) from L. monocytogenes and S. aureus. Alignments were performed by using CLUSTALW and AlignP programs. Lismo, L. monocytogenes (EGD-e); Stau, S. aureus. Identical residues are boxed and shaded. (S. aureus AgrA is from strain N315, accession no. P13131; S. aureus AgrC is from strain KSI54, accession no. gi:1916243). In panel B, the transmembrane N-terminal domain (boxed) and the histidine kinase domain of AgrC are indicated.

Structural predictions and sequence alignments of AgrC of L. monocytogenes predict the presence of five or six membrane-spanning helices in the N-terminal part of the protein, suggesting an organization similar to that of the S. aureus protein. Secondary structure predictions were performed with the TOPPRED 2 program (available on the Internet at http://www.sbc.su.se/∼erikw/toppred2/), and sequence alignments were performed with the CLUSTALW algorithm (http://www.infobiogen.fr/services/analyseq/cgi-bin/clustalw_in.pl). Indeed, in S. aureus, AgrC contains two distinct domains: an N-terminal receiver module, which is highly variable among different groups of S. aureus (18), and a C-terminal cytoplasmic histidine kinase domain that is conserved in the same subgroup (with 44% identity in the region from amino acids 236 to 431). The transmembrane topology model of AgrC of S. aureus (21), the receiver module comprises five or six transmembrane helices followed by the cytoplasmic domain.

However, no equivalent to the divergent transcript RNAIII of S. aureus was found upstream of the agr operon of L. monocytogenes (Fig. 1A). The ORF (lmo0047) preceding agrB is in the same orientation as agrB and encodes a 203-amino-acid-long hypothetical protein of unknown function. The agrBDCA gene cluster is flanked on both sides by putative transcription terminators (in the 257-bp intergenic region between lmo0047 and agrB and downstream of the agrBDCA operon). The ORF (lmo0052) located 167 bp downstream of agrA encodes a hypothetical protein of 657 amino acids, highly similar to YybT, a hypothetical protein of B. subtilis. A potential promoter region is predicted immediately upstream of agrB (with the promoter prediction program available on the Internet at http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html).

(ii) Transcriptional analyses.

First, we tested by RT-PCR whether the agr region was transcribed in the wild-type strain (EGD-e) grown in laboratory conditions (see Materials and Methods). Our RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that the three genes agrB, agrC, and agrA were transcribed, suggesting that they encode functional proteins. Moreover, we found that agrB, agrD, and agrC, as well as agrC and agrA, were cotranscribed (Fig. 1B), confirming that that the four genes constitute an operon.

Then, we quantified by real-time quantitative RT-PCR the variations in the levels of expression of the mRNA from agrB, agrC, and agrA genes during the exponential and stationary phases of growth. Bacteria were grown at 37°C in BHI rich medium. Two internal control genes were used: gyr, encoding gyrase, and the gene determining 16S rRNA (see Materials and Methods for details). The levels of expression of agrB, agrC, and agrA were comparable in exponential-phase growth (data not shown). In the stationary phase of growth, the expression of agrB and agrC remained similar to that in the exponential phase, the ratio of the values recorded for the two conditions of growth being around one. In contrast, a twofold increase in the amount of agrA mRNA was recorded in the stationary phase compared to that in the exponential phase (Fig. 1C). These data indicate that, in contrast to those of S. aureus, the levels of expression of agrB and agrC of L. monocytogenes are not up-regulated in the stationary phase. They also demonstrate that, as reported for S. aureus, a short transcript encoding AgrA is expressed in L. monocytogenes.

Properties of the agrA mutant of L. monocytogenes.

At all the temperatures tested (4, 30, 37, and 42°C), growth of the agrA mutant was identical to that of wild-type EGD-e in BHI medium, indicating that the Tn1545 insertion had no effect on bacterial multiplication in culture (data not shown).

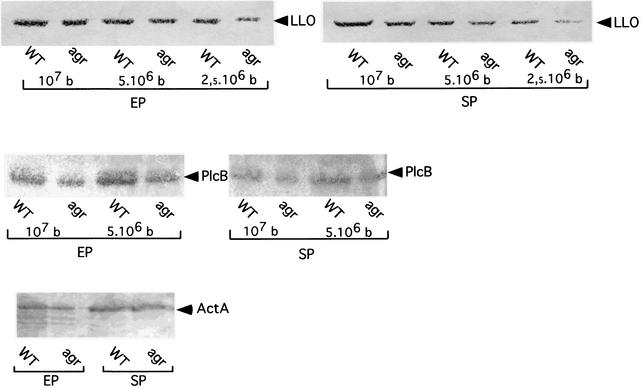

Effect of agrA inactivation on protein secretion.

In S. aureus, surface proteins such as protein A, a major surface antigen, are produced early in growth in vitro and their production is down-regulated at a later time. Most secreted proteins are produced at the end of exponential growth. The production of all these factors (the virulence response) is controlled primarily by the global regulatory locus agr (see reference 28 for a review). Therefore, we tested whether inactivation of agrA of L. monocytogenes would alter the production of known virulence factors. We chose two virulence factors secreted in the culture medium, LLO and the phosphatidylcholine phospholipase (PlcB), and the membrane-anchored protein ActA. No differences in the production of ActA and PC-PLC were observed in the agrA mutant compared to that in the wild-type strain (Fig. 3). However, a moderate reduction in the amount of LLO secreted was observed in the stationary phase (ca. 2.5-fold, as determined by densitometry scanning of the Western blot with the NIH Image software version 1.61). This observation was in agreement with the AgrA/AgrC-dependent increase in expression of postexponentially secreted proteins reported for S. aureus (18).

FIG. 3.

Western blot analyses. Culture supernatants and membrane fractions from cells grown overnight at 37°C with agitation in BHI medium were tested in exponential phase (EP) and stationary phase (SP). Identical amounts of each culture supernatant were loaded onto SDS-10% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred electrophoretically onto nitrocellulose and detected with specific antibodies. (Upper panel) Anti-LLO MAb. Decreasing amounts of supernatant were loaded, corresponding to 107, 5 × 106, and 2.5 × 106 bacteria (b). The anti-LLO MAbs SE1 and SE2 were used at a final dilution of 1/1,000. (Middle panel) Anti-PC-PLC. Decreasing amounts of supernatant were loaded, corresponding to 107 and 5 × 106 bacteria. The anti-PlcB polyclonal antibody was used at a final dilution of 1/200. (Lower panel) Anti-ActA. Membrane fractions corresponding to 107 bacteria were loaded. The anti-ActA polyclonal antibody was used at a final dilution of 1/1,000. WT, strain EGD-e; agr, agrA-Tn1545 insertion mutant.

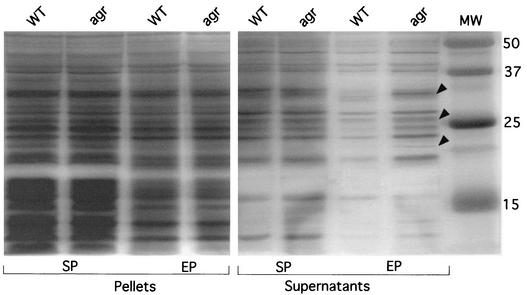

We then tested whether the agr locus would influence the production of other proteins by comparing the protein contents of culture supernatants or envelope fractions of the agrA mutant to those of the wild-type strain.

Silver staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gels loaded with supernatants of exponentially grown cells revealed the presence of several additional protein bands in the agrA mutant (Fig. 4), indicating that the agr locus plays a role in regulating as yet unidentified secreted proteins of L. monocytogenes. The additional bands observed with the agrA mutant (mainly between 20 and 40 kDa) might correspond to the release of normally cell wall-associated proteins that would be down-regulated in the wild-type background. Further proteomic analyses will be required to address this point. In contrast, we did not observe significant differences between the protein patterns of the mutant and those of the wild-type strain in the stationary phase, either in bacterial supernatants or in envelope fractions (Fig. 4). Since agr of S. aureus has been shown to up-regulate protein secretion in the stationary phase, we expected to see the disappearance of bands in the supernatant of the agr mutant. Our data suggest that the agr locus represses expression of protein in the exponential phase. They imply that the role of the agr locus of L. monocytogenes in regulating protein secretion is distinct from that of the corresponding locus of S. aureus.

FIG. 4.

Protein secretion in the agrA mutant. Culture supernatants and membrane fractions from cells grown overnight at 37°C with agitation in RPMI medium were tested in exponential phase (EP) and stationary phase (SP). The black arrowheads point to protein bands present in the supernatant of the agr mutant in the exponential phase of growth that are missing in that of the wild-type (WT) strain. Numbers to the right correspond to the molecular weight (MW) markers.

Effect of agrA inactivation on intracellular multiplication and bacterial virulence.

The ability of the mutants to penetrate into and replicate within cells was studied first with two nonprofessional phagocytic mammalian cell lines: epithelial cells (Caco-2) and hepatocytes (HepG-2), previously used as model systems to study infection by L. monocytogenes (7, 22, 28). The number of viable mutant bacteria and that of wild-type bacteria were not statistically different (although the number of mutant bacteria was slightly lower) at any time in the growth curve and in both cell types (Fig. 5A and B). We also monitored the intracellular multiplication of the agrA mutant in bone marrow-derived macrophages from BALB/c mice. The agrA mutant did not show any growth defect in macrophages, indicating that the agrA gene product does not participate in intracellular survival of L. monocytogenes.

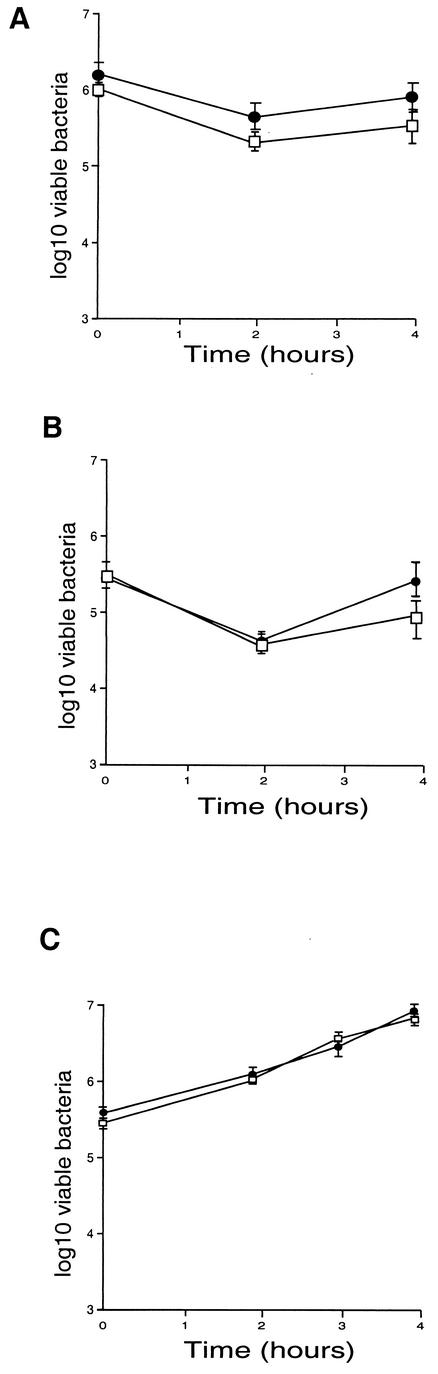

FIG.5.

Invasiveness of the agrA mutant was evaluated in two different cell lines, Caco-2 cells (A) and HepG-2 cells (B), and in bone marrow macrophages (C). Cell monolayers were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with approximately 100 bacteria per cell. After washing, the cells were reincubated for 4 h in fresh culture medium. At 2, 3, and 4 h, the cells were washed again and lysed and viable bacteria were counted on BHI plates. Values and error bars represent the means and standard deviations of the numbers of bacteria per well (three wells per assay, two different assays). •, EGD-e; □, agrA mutant.

In vivo properties.

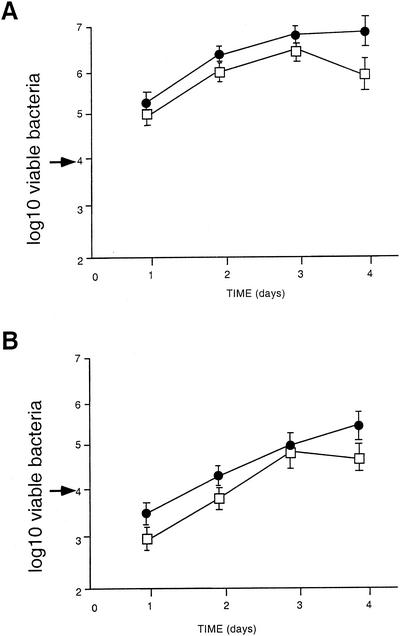

We determined the LD50 of the agrA mutant by i.v. inoculation of Swiss mice. The LD50 of the agrA mutant was of 105.6, i.e., 10-fold higher than that of the parental strain (104.6), reflecting a moderate attenuation. We monitored the kinetics of bacterial survival in the spleens and livers of mice infected with a sublethal dose of 104 bacteria per mouse. As shown in Fig. 6, the capacity of the agrA mutant to survive and multiply in vivo was only slightly lower than that of the wild-type strain, both in the spleens and in the livers of infected animals. These data favor the idea that the agr locus might have only a global indirect influence on the pathogenesis of L. monocytogenes rather than a direct effect on the temporal control of key virulence factors.

FIG. 6.

In vivo survival of the agrA mutant. The kinetics of bacterial growth were monitored in mice infected either with EGD-e or with the agrA mutant. Mice were inoculated with 2 × 104 bacteria (indicated by an arrow to the left of the ordinate). Bacterial survival in the spleens (A) and livers (B) was monitored over a 4-day period. •, EGD-e; □, agrA mutant.

DISCUSSION

We report for the first time the participation of a locus homologous to the agr locus of S. aureus in the virulence of L. monocytogenes. Inactivation of the agrA homologue reduced bacterial virulence without impairing intracellular survival, suggesting an indirect participation of this locus in the pathogenicity of the bacterium.

Role of the agr locus in protein secretion and bacterial virulence.

We show here that the agr locus of L. monocytogenes influences the production of several secreted proteins, including LLO. However, these variations do not correlate with a major defect in virulence, suggesting that the regulatory functions of the agr locus might be less critical for the development of the infectious cycle than for the saprophytic life of the bacterium. Strikingly, inactivation of agrA attenuated the virulence of L. monocytogenes in the mouse model (a 10-fold reduction of the LD50) without significantly impairing bacterial growth in vitro. This unexpected phenotype suggests that the agrA mutation might exert an effect on the overall infectious process.

Possible roles of the agr locus in L. monocytogenes.

In addition to agr, S. aureus was shown to possess a second global regulatory locus, designated sar, that also influences exoprotein and cell surface protein expression. The sarA locus contains three overlapping transcripts designated sarA, sarC, and sarB. SarA binds to conserved regions termed “Sar boxes” within promoter regions of genes encoding secreted and cell surface proteins as well as to agr. SarA binding to agr promoters (26) increases both RNAII and RNAIII and therefore contributes indirectly to the regulation of some virulence genes. SarA also affects the expression of certain virulence genes directly, independently of its effects on agr.

No homologue of the RNAIII transcript or SarA could be found in the genome of L. monocytogenes by using BLAST experiments. The fact that L. monocytogenes lacks the equivalent of RNAIII, and a SarA homologue, strongly suggests that the regulation of the agr locus and agr-dependent protein expression are quite different in the two organisms. Since S. aureus is an extracellular pathogen while L. monocytogenes is able to multiply intracellularly, the two organisms have probably developed distinct strategies to temporally control their production of virulence factors.

A third two-component regulatory system of S. aureus, the ArlS/ArlR system, has also been recently shown to influence protein secretion. The data suggest that the three systems interact to modulate the virulence regulation network in S. aureus (12). It is likely that other yet unknown two-component systems are involved in these regulatory networks. Notably, by reexamining the sequence of LisR/LisK proteins of L. monocytogenes (5), we found that they shared significant similarities with ArlR/ArlS of S. aureus; LisR and LisK share 53 and 34% amino acid identity with ArlR and ArlS, respectively.

Of interest, a series of SarA homologues have been identified by computer-assisted analysis of the recently released S. aureus genomes (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome and www.TIGR.org) (23, 29). The four closest homologues of SarA are SarT (or SarH3), SarS (or SarH1), SarU (or SarH2), and SarR. As in S. aureus, RNAIII is up-regulated in a sarT mutant and it is believed that sarT may down-regulate agr RNAIII expression. Thus, in addition to the cooperative effect of the AIPs of agr secreted by the bacteria, the sarT pathway may represent a second level of control of the agr signal. By searching for paralogs of SarT, SarS, SarU, and SarR in the genome of L. monocytogenes, we identified a single ORF, lmo1225, encoding a protein of 150 amino acids that shares 29.2% identity and 62.5% similarity with SarT (SA2506). Thus, the possibility cannot be excluded that in L. monocytogenes, this SarT homologue may influence expression of the agr locus.

At this stage it is possible to speculate that the modest defect caused by the inactivation of agrA on the virulence of L. monocytogenes might be due to a compensatory role of another (or more) yet to be determined two-component regulatory system(s). Alternatively, it is also possible that a response regulator module from another two-component regulatory system may be able to interact functionally with the sensor AgrC to transduce the agr-dependent signals.

A recent study showed that, although the agr locus of S. aureus can modulate the expression of secreted proteins in cell cultures, it has little or no regulatory role in vivo (34), suggesting the existence of complex regulatory networks sensing and responding to the variations of environmental conditions of growth. The present work constitutes the first preliminary report on the role of the agr locus of L. monocytogenes. The molecular mechanisms by which the agr locus participates in or influences the pathogenicity of L. monocytogenes in vivo remain to be elucidated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Salete Newton, Phillip Klebba, and Colin Tinsley for careful reading of the manuscript and helpful comments on this work.

This work was supported by CNRS, INSERM, Université Paris V, Université Paris VII, and the EEC (BMH-4 CT 960659). Nicolas Autret received a fellowship from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie and from Université Paris V. Catherine Raynaud was supported by a fellowship from the FRM.

Editor: J. T. Barbieri

REFERENCES

- 1.Autret, N., I. Dubail, P. Trieu-Cuot, P. Berche, and A. Charbit. 2001. Identification of new genes involved in the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes by signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 69:2054-2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berche, P. 1995. Bacteremia is required for invasion of the murine central nervous system by Listeria monocytogenes. Microb. Pathog. 18:323-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celli, J., and P. Trieu-Cuot. 1998. Circularization of Tn916 is required for expression of the transposon-encoded transfer functions: characterization of long tetracycline-inducible transcripts reading through the attachment site. Mol. Microbiol. 28:103-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cossart, P., and M. Lecuit. 1998. Interactions of Listeria monocytogenes with mammalian cells during entry and actin-based movement: bacterial factors, cellular ligands and signaling. EMBO J. 17:3797-3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotter, P. D., N. Emerson, C. G. Gahan, and C. Hill. 1999. Identification and disruption of lisRK, a genetic locus encoding a two-component signal transduction system involved in stress tolerance and virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 181:6840-6843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Chastellier, C., and P. Berche. 1994. Fate of Listeria monocytogenes in murine macrophages: evidence for simultaneous killing and survival of intracellular bacteria. Infect. Immun. 62:543-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dramsi, S., I. Biswas, E. Maguin, L. Braun, P. Mastroeni, and P. Cossart. 1995. Entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes requires expression of inIB, a surface protein of the internalin multigene family. Mol. Microbiol. 16:251-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drevets, D. A., R. T. Sawyer, T. A. Potter, and P. A. Campbell. 1995. Listeria monocytogenes infects human endothelial cells by two distinct mechanisms. Infect. Immun. 63:4268-4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erdenlig, S., A. J. Ainsworth, and F. W. Austin. 1999. Production of monoclonal antibodies to Listeria monocytogenes and their application to determine the virulence of isolates from channel catfish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2827-2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finney, D. J. 1971. Probit analysis, 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

- 11.Flanary, P. L., R. D. Allen, L. Dons, and S. Kathariou. 1999. Insertional inactivation of the Listeria monocytogenes cheYA operon abolishes response to oxygen gradients and reduces the number of flagella. Can. J. Microbiol. 45:646-652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fournier, B., A. Klier, and G. Rapoport. 2001. The two-component system ArlS-ArlR is a regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 41:247-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaillard, J. L., P. Berche, J. Mounier, S. Richard, and P. Sansonetti. 1987. In vitro model of penetration and intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes in the human enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2. Infect. Immun. 55:2822-2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaillard, J. L., F. Jaubert, and P. Berche. 1996. The inlAB locus mediates the entry of Listeria monocytogenes into hepatocytes in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 183:359-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garandeau, C., H. Reglier-Poupet, I. Dubail, J. L. Beretti, P. Berche, and A. Charbit. 2002. The sortase SrtA of Listeria monocytogenes is involved in processing of internalin and in virulence. Infect. Immun. 70:1382-1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glaser, P., L. Frangeul, C. Buchrieser, A. Amend, F. Baquero, P. Berche, H. Bloecker, P. Brandt, T. Chakraborty, A. Charbit, F. Chetouani, E. Couvé, A. de Daruvar, P. Dehoux, E. Domann, G. Domínguez-Bernal, E. Duchaud, L. Durand, O. Dussurget, K. D. Entian, H. Fsihi, F. Garcia-Del Portillo, P. Garrido, L. Gautier, W. Goebel, N. Gómez-López, T. Hain, J. Hauf, D. Jackson, L. M. Jones, U. Kaerst, J. Kreft, M. Kuhn, F. Kunst, G. Kurapkat, E. Madueño, A. Maitournam, J. Mata Vicente, E. Ng, G. Nordsiek, S. Novella, B. de Pablos, J. C. Pérez-Diaz, R. Purcell, B. Remmel, M. Rose, C. Rusniok, T. Schlueter, N. Simoes, A. Tierrez, J. A. Vázquez-Boland, H. Voss, J. Wehland, and P. Cossart. 2001. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science 294:849-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgson, D. A. 2000. Generalized transduction of serotype 1/2 and serotype 4b strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:312-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji, G., R. Beavis, and R. P. Novick. 1997. Bacterial interference caused by autoinducing peptide variants. Science 276:2027-2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kallipolitis, B. H., and H. Ingmer. 2001. Listeria monocytogenes response regulators important for stress tolerance and pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 204:111-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhn, M., and W. Goebel. 1989. Identification of an extracellular protein of Listeria monocytogenes possibly involved in intracellular uptake by mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 57:55-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lina, G., S. Jarraud, G. Ji, T. Greenland, A. Pedraza, J. Etienne, R. P. Novick, and F. Vandenesch. 1998. Transmembrane topology and histidine protein kinase activity of AgrC, the agr signal receptor in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 28:655-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackaness, G. B. 1962. Cellular resistance to infection. J. Exp. Med. 116:381-406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manna, A. C., and A. L. Cheung. 2003. SarU, a SarA homolog, is repressed by SarT and regulates virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 71:343-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merino, D., H. Reglier-Poupet, P. Berche, and A. Charbit. 2002. A hypermutator phenotype attenuates the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes in a mouse model. Mol. Microbiol. 44:877-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morfeldt, E., I. Panova-Sapundjieva, B. Gustafsson, and S. Arvidson. 1996. Detection of the response regulator AgrA in the cytosolic fraction of Staphylococcus aureus by monoclonal antibodies. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 143:195-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morfeldt, E., K. Tegmark, and S. Arvidson. 1996. Transcriptional control of the agr-dependent virulence gene regulator, RNAIII, in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 21:1227-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Novick, R. P. 2000. Pathogenicity factors and their regulation, p. 392-407. In V. A. Fischetti, R. P. Novick, J. J. Ferreti, D. A. Portnoy, and J. I. Rood, (ed.), Gram-positive pathogens. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 28.Novick, R. P., and T. W. Muir. 1999. Virulence gene regulation by peptides in staphylococci and other Gram-positive bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:40-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt, K. A., A. C. Manna, S. Gill, and A. L. Cheung. 2001. SarT, a repressor of alpha-hemolysin in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 69:4749-4758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stephenson, K., and J. A. Hoch. 2002. Two-component and phosphorelay signal-transduction systems as therapeutic targets. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2:507-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Throup, J. P., K. K. Koretke, A. P. Bryant, K. A. Ingraham, A. F. Chalker, Y. Ge, A. Marra, N. G. Wallis, J. R. Brown, D. J. Holmes, M. Rosenberg, and M. K. Burnham. 2000. A genomic analysis of two-component signal transduction in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 35:566-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai, C. M., and C. E. Frasch. 1982. A sensitive silver stain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 119:115-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vazquez-Boland, J. A., M. Kuhn, P. Berche, T. Chakraborty, G. Dominguez-Bernal, W. Goebel, and B. Gonzalez-Zorn. 2001. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:584-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yarwood, J. M., J. K. McCormick, M. L. Paustian, V. Kapur, and P. M. Schlievert. 2002. Repression of the Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator in serum and in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 184:1095-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]