Abstract

Legionella pneumophila, a parasite of aquatic amoebae and pathogen of pulmonary macrophages, replicates intracellularly, utilizing a type IV secretion system to subvert the trafficking of Legionella-containing phagosomes. Defense against host-derived reactive oxygen species has been proposed as critical for intracellular replication. Virulence traits of null mutants in katA and katB, encoding the two Legionella catalase-peroxidases, were analyzed to evaluate the hypothesis that L. pneumophila must decompose hydrogen peroxide to establish a replication niche in macrophages. Phagosomes containing katA or katB mutant Legionella colocalize with LAMP-1, a late endosomal-lysosomal marker, at twice the frequency of those of wild-type strain JR32 and show a decreased frequency of bacterial replication, in similarity to phenotypes of mutants with mutations in dotA and dotB, encoding components of the Type IV secretion system. Quantitative similarity of the katA/B phenotypes indicates that each contributes to virulence traits largely independently of intracellular compartmentalization (KatA in the periplasm and KatB in the cytosol). These data support a model in which KatA and KatB maintain a critically low level of H2O2 compatible with proper phagosome trafficking mediated by the type IV secretion apparatus. During these studies, we observed that dotA and dotB mutations in wild-type strain Lp02 had no effect on intracellular multiplication in the amoeba Acanthamoeba castellanii, indicating that certain dotA/B functions in Lp02 are dispensable in that experimental model. We also observed that wild-type JR32, unlike Lp02, shows minimal contact-dependent cytotoxicity, suggesting that cytotoxicity of JR32 is not a prerequisite for formation of replication-competent Legionella phagosomes in macrophages.

Legionella pneumophila, the causative organism of Legionnaires' pneumonia (13, 40), resides in natural and man-made freshwater environments as a free-living organism in biofilms (51, 52) and as an intracellular parasite of amoebae (1, 55, 66). Legionella-containing amoebae can form cysts that survive chlorination (18) and contaminate domestic water supplies. Aerosolization of these cysts from environmental reservoirs—humidifiers, air conditioning ducts, water cooling towers, and shower heads—can deliver an infectious inoculum to a susceptible individual (70). Following invasion of pulmonary macrophages by L. pneumophila, the bacterium resides in specialized phagosomes that are delayed in fusion with lysosomes and permissive for subsequent bacterial replication (68). Two virulence islands, containing the dot (defective organelle transport)/icm (intracellular multiplication) genes, encode a type IV secretion apparatus. This apparatus is proposed to inject bacterial proteins into the host cell that alter trafficking pathways and permit formation of the specialized phagosome that favors transition of Legionella to a replicative form (16, 35, 57, 63, 65, 69). A type II secretion system is also required for intracellular multiplication (25, 53). Growth of L. pneumophila to postexponential (PE) phase elicits cardinal traits of the virulent organism that are lacking from exponentially growing cultures: sensitivity to sodium ions, motility, cytotoxicity to primary macrophages, and the ability of Legionella-containing phagosomes to be diverted from fusion with lysosomes (12). These and other observations support a model in which L. pneumophila alternates between an intracellular replicative form and an extracellular transmissible form in response to growth conditions (69).

Several virulence factors associated with growth conditions have been characterized. The Legionella homologue of RpoS, an enteric regulator of starvation and other stress responses, is required for maximal intracellular growth in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages and Acanthamoeba castellanii, an environmental amoeba host, but not in a human monocyte-derived macrophage line (4, 26). In the stationary phase, RpoS and the LetA/S two-component regulator induce sodium sensitivity, cytotoxicity, motility, and proficient infection of primary murine macrophages (4, 28). On the other hand, none of nine icm genes tested shows any significant change in expression during growth or in an rpoS null (78), suggesting that L. pneumophila expresses its type IV secretion apparatus constitutively during growth. RalF, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor and candidate substrate of the type IV secretion apparatus, is induced threefold in the transition from exponential (E) to stationary phase, but ralF null mutants infect macrophages as efficiently as the wild type (46). Thus, the genes induced by RpoS and LetA/S to promote differentiation of L. pneumophila to a transmissible, infectious form remain to be identified.

We are investigating the role of catalase-peroxidases, enzymes that catalyze the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, as growth stage-dependent factors that promote intracellular survival and growth of L. pneumophila (5, 6). Increased catalase-peroxidase activity is a hallmark of the stationary phase, and genes encoding these activities frequently belong to regulons controlling a transition between replicative and nonreplicative forms (19, 45, 48). Expression of the two bifunctional catalase-peroxidases in Legionella increases during the shift from E to stationary phase, conditions that favor the transition of replicating bacteria into a transmissible form. Activity of the periplasmic KatA increases 8- to 10-fold during the exit from E phase, as assessed by measuring the peroxidatic activity of KatA. Under these growth conditions, activity of the cytosolic KatB is induced about 20-fold on the basis of a katB::lacZ translational fusion. Moreover, inactivation of katA or katB alters the intracellular multiplication of L. pneumophila in the THP-1 monocyte line when grown in cultures. Detection of bacteria released into the tissue culture medium is delayed by 1 and 2 days for the katA and katB null mutants, respectively. Thereafter, both the apparent rate of intracellular replication and the maximum yield of each null mutant are similar to those of the wild type (5, 6). These observations suggest that the initial adaptation of katA/B mutants to an intracellular niche is defective, presumably because of exposure to H2O2.

Several lines of evidence indicate that L. pneumophila is exposed to H2O2 and/or other reactive oxygen species during phagocytosis. A respiratory burst, as demonstrated by conversion of nitroblue tetrazolium to formazan particles, is produced on ingestion of L. pneumophila by primate alveolar macrophages (33) or by amoebae (24). The restriction of L. pneumophila by the J774.1 murine macrophage line is attributed to increased production of reactive oxygen species compared to that of a macrophage line permissive to Legionella intracellular growth (37). These investigations suggest that the ability of L. pneumophila to mount a defense against host-generated reactive oxygen species is critical to its pathogenesis. This defense may protect specific macromolecular targets in Legionella required for invasion or survival within macrophages or may maintain a redox state necessary for metabolic changes accompanying a transition from an extracellular transmissible form to an intracellular replicative state.

The present study was undertaken to investigate the model that decomposition of hydrogen peroxide is required for adaptation of L. pneumophila to an intracellular niche permissive to subversion of phagosome maturation and replication in macrophages. This model was evaluated by comparing katA and katB mutants with the isogenic wild-type strain JR32 with respect to phagosome trafficking, replication, and contact-dependent cytotoxicity in bone marrow-derived macrophages and intracellular growth in the amoeba A. castellanii. The dotA and dotB mutants of wild-type strain Lp02 were included as avirulent controls. Our results indicate that Legionella species require KatA and KatB to subvert maturation of the phagosome either by interaction with the dot/icm pathway or by an independent pathway. Quantitative aspects of the katA and katB defects indicate that both catalase-peroxidases contribute to virulence phenotypes in a fashion largely independent of isozyme compartmentalization in periplasm or cytosol. These data support the model that KatA/B are required for maintenance of a critically low level of H2O2 by equilibration of H2O2 between periplasm and cytosol. In parallel studies of the Lp02 strains, we observed that dotA and dotB mutations in Lp02 are without effect on intracellular growth in A. castellanii, despite severe consequences on growth in macrophage hosts. In addition, we observed that wild-type strain JR32 shows minimal contact-dependent cytotoxicity yet still blocks phagosome maturation with an efficiency comparable to that of the cytotoxic wild-type strain Lp02. This suggests that pore formation at the host cell plasma membrane, the proposed mechanism of cytotoxicity, is not a prerequisite in JR32 for formation of the replication-competent Legionella phagosome in macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and media. (i) Macrophage cultures.

Mouse macrophages were derived from bone marrow exudates of cells obtained from femurs of female A/J mice (Jackson Laboratory) as described previously (71). After a 7-day culture in L-cell-conditioned medium, macrophages were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (RPMI-FBS; GIBCO/BRL), and plated as described below for quantitative intracellular growth, internalization, cytotoxicity and immunofluorescence assays.

(ii) Amoeba cultures.

A. castellanii (ATCC 30234) was cultured at 28°C in 75-cm2 tissue culture flasks in proteose peptone-yeast extract-glucose (PYG) medium (43). Adherent cells (29, 64) were plated for intracellular growth assays as described below.

(iii) Bacterial cultures.

The bacterial strains used in this study (Table 1) were cultured at 37°C. L. pneumophila strain JR32 and its isogenic katA and katB null mutants (5, 6) were cultured in N-(2-acetamido)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (ACES)-buffered pH 6.9 yeast extract (AYE) broth or on charcoal-ACES-buffered pH 6.9 yeast extract (CAYE) agar plates (21, 31). L. pneumophila strain Lp02 and its isogenic dotA (7, 8) and dotB mutants were grown in cultures in AYET broth or on CAYET plates, i.e., AYE broth or CAYE plates, respectively, supplemented with 100 μg of thymidine per ml because these strains are thymine auxotrophs (7). E and PE cultures were grown to optical densities at 600 nm of 0.5 to 1 and >2.5, respectively (12).

TABLE 1.

L. pneumophila strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant property(s) | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Lp02 | Philadelphia-1 Strr HsdR− Thy−, wild-type strain for dotA and dotB null mutants | 7 |

| dotA | Lp02 dotA (= Lp03) nonsense mutant of Lp02 | 8 |

| dotB | Lp02 dotB (= JV374) internal deletion of nucleotides 1503-2650) | Joseph Vogel, Washington University, St. Louis, Mo. |

| JR32 | (Philadelphia-1 Smr r− m+) Homogenous salt-sensitive isolate of AM511, wild-type strain for katA and katB null mutants | 75 |

| katA | JR32 katA::Gmr | 5 |

| katB | JR32 katB::Cmr Ω | 6 |

| 25D | Avirulent mutant of Philadelphia-1 | 9, 30 |

Antibodies and fluorescent reagents.

Monoclonal antibody 1D4B to the late endosomal-lysosomal marker LAMP-1 glycoprotein was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank of the Department of Pharmacology and Molecular Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, and the Department of Biology, University of Iowa. Rabbit serum specific for L. pneumophila serogroup 1 was from Ralph Isberg, Tufts University School of Medicine. Secondary antisera conjugated to fluorescent probes and Texas Red ovalbumin (TRov; molecular mass, 10 kDa) were obtained from Molecular Probes.

Sodium ion sensitivity.

Broth PE cultures in AYE (JR32, katA, and katB strains) or AYET (Lp02, dotA, and dotB strains) were diluted in 1× M9 salts (42) and plated on CYE or CYET plates, respectively, with and without 100 mM NaCl. The percentage of the culture resistant to sodium ion was calculated from the titer on plates with 100 mM NaCl added compared to that on plates without NaCl added (12), as determined by quantifying CFU.

Intracellular growth and infection efficiency in macrophages.

Macrophages were plated at a density of 2 × 105 to 3 × 105 per well of 24-well tissue culture dishes in 0.5 ml of RPMI-FBS. Bacteria were added at an approximate multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 in the same medium; for infections with Lp02 strains, the medium was supplemented with 100 μg of thymidine per ml. After 2 h at 37°C, extracellular bacteria were removed by washing three times with 0.5 ml of RPMI-FCS. Intracellular growth was measured at 24, 48, and 72 h after infection by pooling culture supernatants and lysates prepared by trituration of monolayers with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then determining the titers of the total number of bacteria per well on CYE or CYET plates. Quantitative intracellular growth was plotted as the ratio of CFU per well to the number of CFU determined by titration at 2 h (4). Infection efficiency was measured by determining the titers of the infection medium and the bacteria released from washed and then lysed monolayers at 2 h after infection, a period before bacterial replication was observed, as described previously (12). Infection efficiency was calculated as follows: [(cell-associated CFU at 2 h)/(CFU in the inoculum)] × 100.

Microscopic assay for intracellular growth (34, 72).

Macrophages (1.5 × 105, cultured in 0.5 ml of RPMI-FBS on 12-mm-diameter glass coverslips) were infected at an MOI of <1 such that only rarely did more than one bacterium infect a macrophage. After 2 h at 37°C, the majority of extracellular bacteria were removed by washing the monolayers three times with 0.5 ml of RPMI-FBS and then the coverslips were incubated an additional 16 h, a period in which most L. pneumophila replicated but did not escape from the macrophage. The coverslips were then fixed with periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde (41) containing 4.5% sucrose, extracted with methanol, and washed three times with PBS. DNA was stained with 4′,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (0.1 μg/ml of PBS). At least 50 infected macrophages were located, and the numbers of intact bacteria per macrophage were counted.

Interaction of L. pneumophila and late endosomes and lysosomes (72).

Macrophages cultured on coverslips were infected with Legionella at an MOI of 1, incubated 2 h at 37°C, then fixed as described above. After the preparations were permeabilized by methanol extraction, LAMP-1 was stained with monoclonal antibody 1D4B followed by Oregon Green-conjugated anti-rat serum (Molecular Probes) and bacteria were stained with 0.1 μg of DAPI per ml of PBS. The interaction of bacteria with late endosomes and lysosomes was quantified as the fraction of cell-associated bacteria that colocalized with LAMP-1.

Phagosome-lysosome fusion assay.

Phagosome-lysosome fusion was quantified essentially as described previously (72). Macrophages whose lysosomes were prelabeled with endocytosed TRov were infected with Legionella at an MOI of 1, incubated 2 h at 37°C, and then fixed as described above. Extracellular bacteria were stained with rabbit serum specific for L. pneumophila followed by Cascade Blue-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibody. The preparations were permeabilized by methanol extraction, and then intracellular and extracellular bacteria were stained with L. pneumophila-specific antiserum followed by Oregon Green-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin antibody (Molecular Probes). The efficiency of phagosome-lysosome fusion was quantified as the ratio of the number of intracellular bacteria that colocalized with TRov to the total number of intracellular bacteria.

Intracellular growth in amoebae.

Amoebae from cultures fed PYG medium 24 h earlier were resuspended in PYG medium at a concentration of 3 × 105 cells/ml, and then 0.5 ml was added per well of 24-well tissue culture dishes. After 1 h at 37°C, the PYG medium was aspirated, the adherent cells were washed with 0.5 ml of 37°C A. castellanii buffer (43), and then 0.5 ml of A. castellanii buffer was added to each well prior to infection by L. pneumophila at an MOI of 2 to 3. For the avirulent strain 25D, the MOI was 4. With Legionella sp. strains Lp02, dotA, and dotB, the A. castellanii buffer was supplemented with 500 μg of thymidine per ml. Over the next 3 days, aliquots were removed from the A. castellanii buffer and plated on CYE or CYET plates for determination of the titers of bacteria released from infected amoebae. Quantitative intracellular growth was expressed as the ratio of CFU/ml at each time point to the number initially added to the well (26, 29, 64).

Cytotoxicity.

To quantify contact-dependent cytotoxicity, macrophages were plated at a density of 3 × 104 to 5 × 104 cells per well of a 96-well tissue culture dish and incubated for 1 h with different MOIs of the Legionella strain. The monolayers were then incubated for 4 h with 0.1 ml of 10% (vol/vol) Alamar Blue solution (Accumed, Inc.) in RPMI-FBS, after which the A570 and A600 of the medium were measured. The percentage of viable macrophages was calculated from a calibration plot of A570 to A600 values for known numbers of uninfected macrophages in the range of 1 × 103 to 5 × 104 cells per well (12, 27).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Samples were mounted in ProLong Antifade (Molecular Probes) and observed with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a 100× Plan-Neofluar objective (numerical aperture of 1.3) and filters 487901, 487910, and 487900. For each experiment under each set of conditions, at least 50 phagosomes were examined (34).

RESULTS

Sodium ion sensitivity.

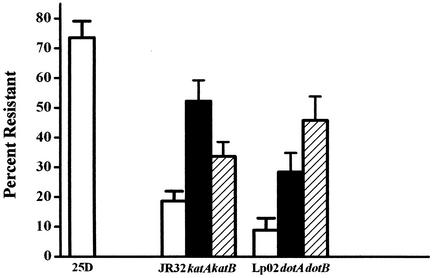

L. pneumophila mutants that have lost sensitivity to sodium ion, as judged by a high efficiency of colony formation on medium containing 100 mM Na+, are frequently defective in virulence phenotypes (14, 30, 39, 58, 73). In cultures of the dotA and dotB mutants, 28 and 46% of the cells are resistant to Na+, respectively, compared to 9% of those of wild-type strain Lp02 (Fig. 1). Cultures of the katA and katB null mutants are similar to those of dotA and dotB, showing 52 and 34% resistance to Na+ compared to 19% for that of wild-type strain JR32. All four mutants were less resistant to Na+ than the avirulent strain 25D (73%; Fig. 1) isolated following repeated passage on agar medium containing 100 mM Na+ (30). In this study, strains were not subjected to repeated passage on agar medium. Nonetheless, to eliminate the unlikely possibility that loss of Na+ sensitivity by katA and katB mutants was due to spontaneous mutations, Na+ sensitivity was determined for mutants complemented with the respective plasmidborne wild-type genes (5, 6). The resistance to Na+ of the complemented katA and katB mutants was significantly reduced compared to that of mutants with the empty plasmid (P < 0.03), suggesting that loss of Na+ sensitivity was not due to spontaneous mutations outside of the katA or katB genes.

FIG. 1.

Sodium resistance. Titers of PE cultures in AYE (25D, JR32, katA, and katB) or in AYET (Lp02, dotA, and dotB) broth were determined on CYE or CYET, respectively, without and with 0.1 M NaCl. The percentages of resistance (± standard deviation) were calculated by comparing the plating efficiency with 0.1 M NaCl to that without 0.1 M NaCl. The P value for a one-sided t test comparing each mutant strain with the corresponding wild-type strain is less than 3 × 10−5.

Quantitative growth experiments in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages.

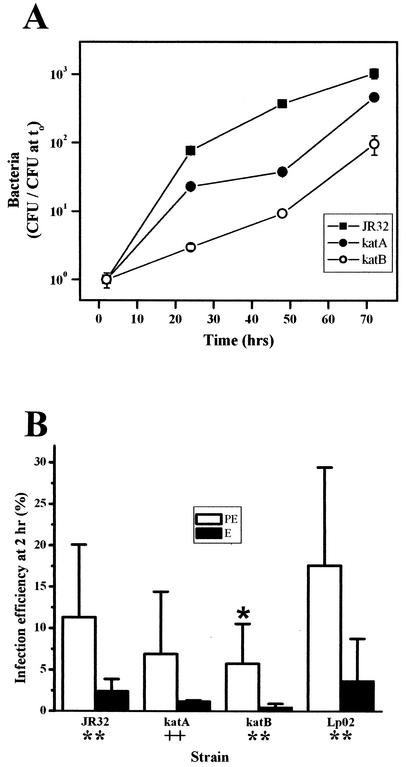

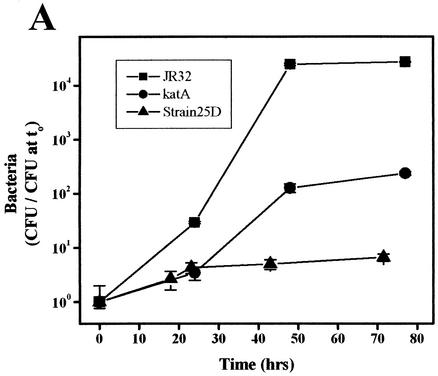

Intracellular growth, a hallmark of Legionella pathogenicity, can be quantified by determination of the titers of bacteria present in host cells and released into the medium following lysis of the host. Quantitative intracellular growth experiments were performed in bone marrow macrophages derived from A/J mice, which are susceptible to infection by L. pneumophila (76). The katA and katB mutants replicate in macrophages, but their yields and apparent growth rates are lower than those observed for wild-type strain JR32 (Fig. 2A). The fold increase of bacteria by 48 h was 380 for the wild-type strain compared to 37 and 9 for the katA and katB strains, respectively. The mean apparent intracellular doubling time (calculated from the growth curve from 0 to 48 h as determined in five different preparations of bone marrow macrophages) was 10.7 ± 2.3, 16.1 ± 2.6, and 6.9 ± 1.2 h for the katA and katB mutant strains and wild-type strain JR32, respectively. By comparison, dotA mutants show no increase in titer over the same time period (7, 72). Defective intracellular multiplication of katA and katB mutants in the THP-1 human monocyte cell line is complemented by plasmid wild-type alleles (5, 6), suggesting that the above-described intracellular growth defects in primary macrophages are likewise attributable to inactivation of KatA and KatB genes.

FIG. 2.

Intracellular growth and infection efficiency in bone marrow-derived macrophages. (A) Intracellular growth. Adherent macrophages were infected with PE cultures at an MOI of 1.0 for 2 h and then washed to remove extracellular bacteria. At the indicated times, macrophages were lysed and titers were determined (± standard deviation) on CYE. (B) Infection efficiency. Macrophages were infected with PE (open bars) or E (filled bars) cultures of the indicated strains at an MOI of 1.0 for 2 h. External bacteria were removed by washing the monolayers. The percentages of internalization (± standard deviation) were calculated from the titers of bacteria as determined after lysis of the macrophages compared to the number of bacteria in the infection medium. Above the error bar is a symbol representing a P value from a one-sided t test comparing PE strains (open bars) with wild-type strain JR32, and below the x axis are symbols representing P values for comparisons of E and PE cultures of each strain. ∗, P < 0.05; ++, P ≤ 0.02; ∗∗, P ≤ 0.003.

To evaluate whether the katA and katB mutants grow poorly in primary cultures of bone marrow macrophages because they are generally compromised in growth, doubling times of broth cultures were determined. With or without thymidine supplementation, the doubling times of katA and katB strains were identical to that of the wild-type strain (references 5 and 6 and data not shown). Therefore, the decreased intracellular growth of the katA and katB mutants reflects a demand of the phagocyte environment and not an inherent defect in growth.

Infection efficiency of Legionella mutants in bone marrow-derived macrophages.

To grow efficiently in bone marrow-derived macrophages, L. pneumophila must first bind, enter, and survive within the host cell. To investigate how catalase-peroxidase activity contributes to the parameter defined as infection efficiency, we measured the fraction of the inoculum that was internalized and viable at 2 h postinfection. The infection efficiencies of the katA and katB mutants were decreased by one-third and one-half, respectively, compared to that of strain JR32 (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that KatA and KatB promote efficient infection of bone marrow macrophages, a trait that contributes to the observed differences in the quantitative growth of intracellular bacteria (Fig. 2A). Our observations (made at 2 h after infection) do not exclude the possibility that significant differences between the katA and katB mutants and wild-type strain JR32 also occur at earlier times (29, 74).

Compared to PE cultures, E cultures of Lp02 are defective in infection efficiency and other virulence traits (12). This dependence of virulence traits on the growth stage of Lp02 is a basis for linking starvation phenomena to pathogenicity in L. pneumophila (12, 69). For strain Lp02, the PE:E ratio of infection efficiencies was 4.8. For JR32 and the katA and katB mutants, the respective PE:E infection ratios were 4.7, 5.8, and 12 (Fig. 2B). These data clearly demonstrate that like that of strain Lp02, infection efficiency of JR32 strains is dependent on the growth stage, indicating that starvation and bacterial differentiation are also linked in the JR32 lineage.

Intracellular growth phenotype of individual L. pneumophila cells in macrophages.

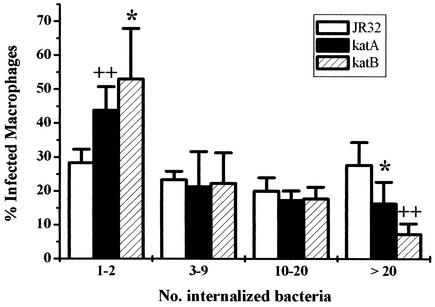

The preceding quantitative growth and infection efficiency experiments measure virulence traits of a population of L. pneumophila, a method that cannot distinguish slow growth by all of the bacteria in the population from efficient replication by only a subset of the bacteria. To analyze the replication of individual endocytosed bacteria, macrophages were infected for 18 h and the number of intracellular bacilli in individual vacuoles of bone marrow-derived macrophages were counted. When an MOI of <0.1 is used, the count for any given vacuole reflects the replication of a single L. pneumophila cell. The infected macrophages were grouped into four classes, containing from 1 to 2 to >20 bacteria per vacuole (Fig. 3). By 18 h after infection, the percentage of macrophages containing only 1 to 2 bacteria per vacuole was significantly higher for katA and katB null mutants than for the wild-type strain (44 and 53%, respectively, compared to 28%), indicating that approximately half of the mutant bacteria failed to multiply. Conversely, the percentage of macrophages containing >20 wild-type bacteria per vacuole was significantly higher for wild-type strain JR32 than for the katA and katB mutants (28% compared to 16 and 7%, respectively). The decreased growth yield and apparent growth rate of katB bacteria in primary macrophages compared to those of katA bacteria (Fig. 2A) are consistent with the smaller percentage of macrophages containing >20 katB bacteria per vacuole (7%) compared to that of vacuoles containing >20 katA bacteria (16%). For comparison, >85% of macrophages contained only one dotA bacterium per vacuole, which is in good agreement with the inability of dotA mutants to grow within macrophage cultures (7, 72).

FIG. 3.

Frequency of replication of individual L. pneumophila cells in bone marrow-derived macrophages. Macrophages were infected with PE cultures of L. pneumophila. After 18 h, the number of bacteria per vacuole in infected macrophages was counted and scored (± standard deviation) as belonging to one of the four categories indicated below the x axis. P values from a one-sided t test comparing mutant strains with the wild-type strain are indicated as follows: ∗, P ≤ 0.05; ++, P < 0.01. For comparisons of katA and katB strains at >20 bacteria per vacuole, P = 0.04.

Intracellular trafficking in bone marrow macrophages.

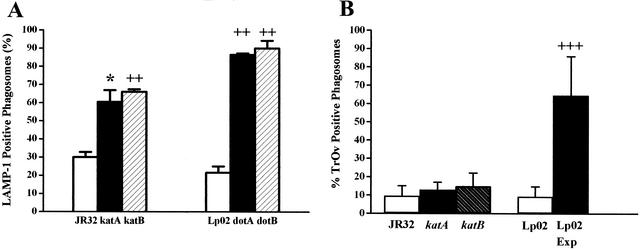

Phagosomes containing dot/icm mutants rapidly fuse with the endosomal pathway, while those containing wild-type L. pneumophila do not (7, 34, 57). Maturation of Legionella-containing phagosomes can be monitored microscopically by scoring their colocalization with markers for late endosomes and lysosomes (34), such as the LAMP-1 glycoprotein (15, 32, 50). At 2 h after infection, 87 and 90% of phagosomes containing dotA and dotB L. pneumophila mutants, respectively, were LAMP-1 positive compared to 22% of phagosomes containing wild-type strain Lp02 (Fig. 4A). This fourfold increase is consistent with the known involvement of dotA and dotB in the subversion of phagosome trafficking (16, 57, 63, 70). For phagosomes containing the katA or katB mutants, 61 or 66%, respectively, colocalize with LAMP-1, a twofold increase compared to wild-type strain JR32 (30%). Thus, the absence of KatA or KatB catalase-peroxidase activity produces an intracellular trafficking defect.

FIG. 4.

Colocalization of L. pneumophila with endosomal markers. Macrophages on coverslips were incubated with PE bacteria of the indicated strains. At 2 h after infection, Legionella-containing phagosomes were identified by immunofluorescence and the percentages (± standard deviation) of those which were also positive for LAMP-1 (A) or TRov (B) were determined. For strain Lp02 in panel B, results for PE cultures are indicated by the rightmost open bar and results for E (Exp) cultures are indicated by the rightmost filled bar. P values for a one-sided t test comparing mutant strains with the corresponding wild-type strain or (in panel B only) comparing E and PE cultures are indicated as follows: ∗, P ≤ 0.05; ++, P < 0.02; +++, P < 0.00015.

When phagosome maturation was assessed by colocalization of L. pneumophila phagosomes with lysosomal TRov, the colocalization was comparable for katA and katB mutants and wild-type strain JR32 at 2 h after infection (Fig. 4B) (10, 13, and 15% TRov positive, respectively). Similar results were found with dotA dotB mutants: 16 and 18% of Legionella phagosomes colocalize with TRov (34) compared to 9% for wild-type strain Lp02 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, for live E-phase (Fig. 4B) and heat-killed PE-phase bacteria of strain Lp02 (34), 65 and >95% of Legionella phagosomes colocalize with TRov, respectively. In sum, our data show that null mutants of katA or katB bear a striking resemblance to dotA or dotB mutants: both classes of mutants are impaired in the ability to isolate Legionella-containing phagosomes from LAMP-1-containing compartments but nevertheless retain activities that prevent fusion of their phagosomes with lysosomes, as judged by the low degree of colocalization with TRov.

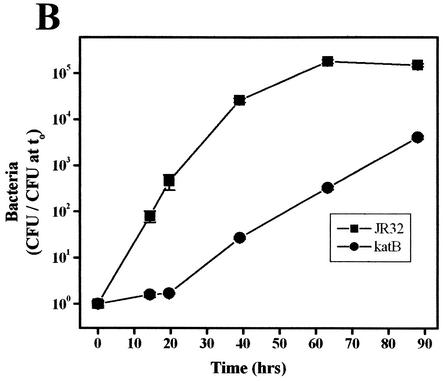

Quantitative growth experiments of Legionella kat and dot mutants in an amoeba host.

Legionnaires' pneumonia is not spread from person to person but by aerosols from environmental reservoirs. L. pneumophila contained within cysts of environmental amoebae are believed to be the infectious inocula (55, 66, 70). To investigate this aspect of Legionella pathogenesis, replication of L. pneumophila was studied in A. castellanii, a freshwater amoeba and an environmental host of Legionella (54-56, 66). Wild-type strain JR32 replicates in A. castellanii (26, 29, 64), but intracellular multiplication of the katA and katB mutants was markedly attenuated in both yield and growth rate (Fig. 5A and B). After 48 h, the yield for the katA and katB mutants increased a modest 130-fold and 150-fold, respectively, compared to a 25,000- to 85,000-fold increase for the wild-type strain. The apparent intracellular doubling times of the katA and katB nulls are 2.4- and 2.1-fold longer that of the wild type, as judged on the basis of the initial slopes for wild-type and katA strains (0 to 48 h) and the slope after the 20-h delay for the katB strain. Avirulent strain 25D is essentially nonreplicative (Fig. 5A) (26, 64).

FIG. 5.

Intracellular growth in A. castellanii. A. castellanii was infected at an MOI of 1.5 to 3.0 with the cultures of indicated PE L. pneumophila strains, and titers (± standard deviation) of bacteria released into the medium were determined on CYE (strains JR32, katA, and 25D [A] and strains JR32 and katB [B]) or CYET (strains Lp02, dotA, and dotB [C]).

Like the L. pneumophila rpoS mutant (4, 26), katA and katB mutants were more severely attenuated in A. castellanii and primary macrophage cultures (Fig. 2, 5A, and 5B) than in macrophage-like cell line cultures (5, 6). This difference in host restriction might be explained by the increased production of reactive oxygen species by amoebae and primary macrophages compared to that by cell lines grown in culture. Although primary macrophage cultures, monocyte lines, and amoebae are all known to exhibit a respiratory burst (11, 17, 24, 33, 37), a quantitative comparison of reactive oxygen species produced on interaction with L. pneumophila has not been performed.

The intracellular multiplication of dotA and dotB mutants in A. castellanii was not attenuated compared to that of their wild-type strain Lp02. Quantitative growth curves for the mutants can be superimposed with that of the wild type (Fig. 5C). For all three strains, the apparent intracellular doubling time calculated from the increase in CFU between 20 and 48 h is comparable to that of Lp02 in broth (2.5 to 3 h). The absence of an intracellular growth phenotype in amoebae is surprising, because these dotA and dotB mutants are defective in multiple virulence traits in primary cultures of murine bone marrow macrophages and are essentially nonreplicative in those hosts (7, 47, 72; B. Byrne and M. S. Swanson, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Amer. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. D/B-70, 1999). To verify that intracellular growth defects of the Lp02 dotA and dotB mutants are macrophage specific, identical bacterial cultures were used for quantitative growth experiments with A. castellanii and the HL-60 monocyte line. Both mutants replicated in A. castellanii identically to Lp02, as depicted in Fig. 5C. In contrast, the dotA and dotB mutants were defective for growth in HL-60 cultures. By 52 h after infection, the titer of wild-type Lp02 in the HL-60 cultures increased more than 2,000-fold, while titers of dotA and dotB mutants increased 6-fold or less (data not shown). As expected, the Lp02 dotA and dotB mutant strains were also sodium resistant (Fig. 1), a trait that frequently correlates with virulence deficits in macrophage phenotypes. Therefore, these particular dotA and dotB mutations in wild-type strain Lp02 are not associated with a replication defect in A. castellanii.

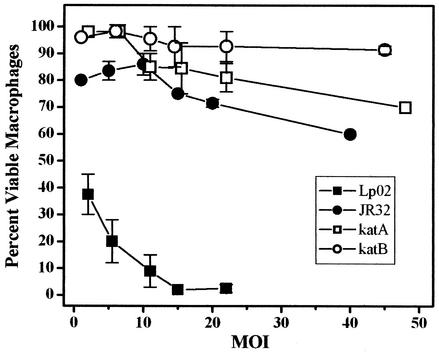

Contact-dependent cytotoxicity.

At multiplicities of infection as low as 5 (12), Legionella sp. strain Lp02 is cytotoxic to murine bone marrow macrophages within 1 h after infection. This killing occurs too rapidly to be related to intracellular replication and has been attributed to a pore-forming activity that causes a contact-dependent lysis that may promote bacterial escape from host cell (2, 12, 36). E cultures of Lp02 are essentially devoid of this contact-dependent cytotoxicity, as are PE cultures of several dot mutants (36) and fliA, letA, and letS mutants (28) derived from Lp02. Quantification of this virulence phenotype in the katA and katB mutants showed that they are slightly less cytotoxic than wild-type strain JR32 (Fig. 6). More striking is the observation that contact-dependent cytotoxicity of wild-type strain JR32 was but a small fraction of that of wild-type strain Lp02. At MOIs of 5 and 15, macrophage survival with JR32 was 84 and 75% compared to 20 and 2% with Lp02, respectively.

FIG. 6.

Cytotoxicity of L. pneumophila to bone marrow-derived macrophages. Macrophages were incubated for 1 h with PE bacteria of the indicated Legionella strain at each of the MOI values shown. The percentages of viable macrophages (± standard deviation) were determined by the Alamar Blue method.

DISCUSSION

The katA and katB mutants are required for proper trafficking in primary macrophages.

Defective intracellular trafficking in macrophages has most often been associated with mutations in the L. pneumophila dot/icm loci and less frequently with those of other mutant classes, including regulators of virulence (4, 28). Our data demonstrate that null mutations in katA or katB also alter L. pneumophila intracellular trafficking in murine bone marrow macrophages in a manner comparable to that observed for dotA and dotB mutations (Fig. 4A). By 2 h after infection, the majority (i.e., twice the wild-type value) of phagosomes containing katA or katB bacteria had acquired the LAMP-1 glycoprotein marker of late endosomes and lysosomes yet continued to evade lysosomal compartments, as judged by colocalization with the endosomal marker TRov (Fig. 4B). Therefore, L. pneumophila appears to isolate its phagosome from LAMP-1-positive endosomes by a Dot/Icm-dependent mechanism that is sensitive to formaldehyde treatment and inactivation of katA or katB. In contrast, evasion of lysosomes is conferred by a virulence factor(s) resistant to formaldehyde treatment and unaffected by inactivation of katA or katB (Fig. 4) (34).

The virulence phenotypes of katA and katB mutants show some similarities to those of a mutant in the L. pneumophila homologue of E. coli htrA/degP, encoding a periplasmic protease-chaperone in the σE regulon. Phagosomes containing htrA/degP mutant bacteria colocalize with LAMP-2, a late endosomal-lysosomal marker, 5 to 10 times more frequently than phagosomes containing wild-type bacteria (49). However, the Legionella htrA/degP mutant shows a general increase in sensitivity to stress; in particular, it is >10,000-fold more sensitive to 100 mM NaCl than the wild type. In contrast, our katA and katB mutants were more resistant to 100 mM NaCl than the wild type (Fig. 1). Therefore, to the extent that sodium sensitivity is an indicator of Dot/Icm function of virulent Legionella, the loss of sodium sensitivity in the katA and katB mutants suggests that catalase-peroxidase activity contributes to or protects the type IV secretion system activity.

Several functions for KatA and KatB in dot/icm-dependent trafficking can be proposed, given that decomposition of H2O2 is the principal activity of catalase-peroxidases. KatA and KatB may influence disulfide bond formation of Dot/Icm proteins or proteins required for Dot/Icm function or may protect them from damage from oxidants generated by Legionella or the host. Alternatively, KatA and KatB may influence the cellular redox potential or protect oxygen-sensitive proteins as energy generation by oxidative phosphorylation and reactive oxygen production increase during the transition from an infectious nonreplicative state to the intracellular replicative form. L. pneumophila enzymes of intermediary metabolism identified in a signature-tagged mutagenesis study using a guinea pig pneumonia model (20) may be targets protected by the catalase-peroxidases in the transition to an intracellular replicative state.

The KatA and KatB isozymes each contribute to L. pneumophila virulence traits in macrophages and A. castellanii.

The presence of two catalase-peroxidases that are ∼60% identical in amino acid sequences (3, 5) raises the question of whether these highly homologous isozymes are functionally redundant. We reported that both isozymes contribute to resistance to exogenous hydrogen peroxide. However, the plating efficiency of a katA null mutant from PE cultures is decreased by 2 to 4 orders of magnitude while that of a katB null mutant is identical to that of the wild type (5, 6). A mixture of overlapping and discrete functions in virulence traits is seen here. The katA and katB mutants are qualitatively similar in their growth defect in A. castellanii (Fig. 5A and B), decreased efficiency of infection (Fig. 2B), and colocalization of phagosomes with LAMP-1 and TRov markers in macrophages (Fig. 4). However, growth in THP-1 cells (5, 6) and in bone marrow-derived macrophages (Fig. 2A and 3) is modestly but quantitatively more defective in the katB mutant than in the katA mutant.

For virulence traits that are quantitatively similar in katA and katB mutants, the intracellular compartmentalization of catalase-peroxidase activity (i.e., periplasmic KatA versus cytosolic KatB) evidently plays a minor role. This can be understood by considering that hydrogen peroxide readily diffuses through membranes (61, 62). Decomposition of H2O2 in one compartment may therefore reduce the H2O2 concentration in the other by equilibration of H2O2 across the inner membrane. This situation contrasts with the functional nonequivalence of L. pneumophila superoxide dismutases (SODs). Cytosolic iron SOD is essential for viability (59), while periplasmic copper-zinc SOD is not (67). Thus, decomposition of periplasmic superoxide by copper-zinc SOD cannot compensate for the absence of iron SOD in the cytosol. This is consistent with the relative impermeability of membranes to the superoxide radical (38).

Our present data combined with previous observations suggest that the virulence traits studied here depend quantitatively on the amount of Legionella KatA or KatB activity. It was previously shown that the KatA and KatB isozymes contribute approximately equally to the catalase activity in cell extracts and that when one gene is inactivated, the activity of the remaining catalase-peroxidase is comparable to the level in the wild type (5, 6). Since quantitatively similar virulence phenotypes were observed for katA/B bacteria expressing approximately half of wild-type catalatic activity, the output of a single catalase-peroxidase isozyme is insufficient to maintain the wild-type phenotype. This implication, analogous to haploinsufficiency in diploid organisms, predicts that the katA katB double mutant would display more severe defects than either single mutant. This prediction has been confirmed. The doubling time of the katA katB double null in broth is twice that of the wild type, while that of single null mutants is identical to that of the wild type (5, 6). In addition, the apparent intracellular doubling time of the katA katB mutant in A. castellanii is 3.0 times that of the wild type (data not shown) compared to 2.4 and 2.1 times that of the wild type for katA and katB single mutants, respectively (Fig. 5A and B).

Together, these data support two key features of our model that KatA and KatB are required for proper trafficking and growth of L. pneumophila in primary macrophages. The prediction that KatA and KatB normalize cellular H2O2 concentrations between periplasmic and cytosolic compartments is supported by qualitatively and quantitatively similar phenotypes for mutants of periplasmic KatA and cytosolic KatB. The prediction that KatA and KatB maintain the H2O2 concentration below a critical threshold for damage is supported by our data that virulence phenotypes of katA and katB null mutants depend quantitatively on the amount of catalase-peroxidase activity. In sum, our observations identify KatA and KatB as growth phase-regulated factors (5, 6) required by Legionella to initiate intracellular replication.

The dotA and dotB mutants of LpO2 are not defective in intracellular growth in A. castellanii.

Since strain Lp02 and its dotA and dotB mutants are thymine auxotrophs (7), we considered the possibility that intracellular growth in amoebae is limited by thymidine availability rather than by intrinsic intracellular growth differences between Lp02 and dotA/B mutants. However, this explanation is unlikely because the apparent intracellular doubling times of Lp02, dotA, and dotB strains are comparable to that of Lp02 in thymidine-supplemented broth in which thymidine is freely available. Thus, our data support the contention that these inactivating mutations of dotA and dotB in the Lp02 background are without effect on intracellular multiplication in the amoeba A. castellanii, although these same mutations render Lp02 nonreplicative in macrophages.

Internalization and intracellular growth of L. pneumophila in amoebae and macrophages occur by processes that are morphologically similar, and mutations in 2 genes in dot/icm region I and 16 genes in dot/icm region II and in genes outside the two dot/icm loci produce similar defects in both experimental models (1, 22, 64). Nonetheless, different defects in amoebae and macrophage models have been reported, although little is know about the basis for these differences because many of these mutations are in genes of unknown function. One class of mutations primarily affects the interaction with macrophages, while a second class primarily affects the interaction with amoebae (10, 23, 64) with little effect on the interaction with the other experimental model. The dotA and dotB mutations in Lp02 belong to the first class. To our knowledge, replication of dotB mutants in amoebae has not been previously quantified. However, a transposon insertion mutant of dotA in strain JR32 is unable to replicate in A. castellanii (64). This raises the possibility that the absence of a phenotype of the Lp02 dotA mutant in A. castellanii is related to background differences between JR32 and Lp02 strains and/or to different effects of transposon (64) versus point (8) mutations on DotA function in an amoeba host.

JR32 and Lp02 wild-type strains differ in contact-dependent cytotoxicity.

Recently, virulence traits were compared for three laboratory strains widely used in Legionella research (60): JR32 and Lp01, derivatives of the Philadelphia 1 strain, and AA100, a derivative of strain 130 b. Strain Lp02 was derived from Lp01 as a thymidine auxotroph (7). Our JR32 and Lp02 data on the acquisition of the LAMP-1 marker by Legionella-containing phagosomes (Fig. 4A) and infection efficiency of E and PE cultures (Fig. 2B) with primary murine bone marrow-derived macrophages are in good agreement with the published data for strains JR32 and Lp01 with human U937 monocyte-derived macrophages (60). In contrast, we observed that JR32 is remarkably deficient compared to Lp02 in contact-dependent cytotoxicity (Fig. 6), a virulence trait not examined in the previous study (60). Contact-dependent cytotoxicity is attributed to a Legionella activity that forms pores in the macrophage membrane, leading to osmotic lysis and macrophage death (35, 36). To our knowledge, the relative paucity of contact-dependent cytotoxicity of strain JR32 towards primary macrophages has not previously been reported.

It was previously proposed that cytotoxicity is not sufficient for endosomal trafficking and intracellular replication on the basis of the isolation of a mutant that retains cytotoxicity towards primary macrophages but is defective in evasion of phagosome-lysosome fusion (77). In the present study, we observed that wild-type strain JR32, which is as competent as strain Lp02 in evasion of phagosome-lysosome fusion and intracellular replication, essentially lacks contact-dependent cytotoxicity. Therefore, our data favor the hypothesis that the activity related to contact-dependent cytotoxicity is required at the end of the intracellular life cycle for L. pneumophila to escape from amoebae (2, 12, 44) rather than being essential in the evasion of the endosomal pathway or intracellular replication which occurs earlier.

In sum, our studies identify oxidative stress, functional consequences of different inactivating mutations in dotA, and the difference in macrophage cytotoxicity between Lp02 and JR32 lines as areas for future study of virulence mechanisms in L. pneumophila.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AI44212 to M.S.S. and NSF grant MCB-980992 and an REU supplement to that grant to H.M.S.

Editor: S. H. E. Kaufmann

REFERENCES

- 1.Abu Kwaik, Y., L. Y. Gao, B. J. Stone, C. Venkataraman, and O. S. Harb. 1998. Invasion of protozoa by Legionella pneumophila and its role in bacterial ecology and pathogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3127-3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alli, O. A., L. Y. Gao, L. L. Pedersen, S. Zink, M. Radulic, M. Doric, and Y. Abu Kwaik. 2000. Temporal pore formation-mediated egress from macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 68:6431-6440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amemura-Maekawa, J., S. Mishima-Abe, F. Kura, T. Takahashi, and H. Watanabe. 1999. Identification of a novel periplasmic catalase-peroxidase KatA of Legionella pneumophila. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:339-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachman, M. A., and M. S. Swanson. 2001. RpoS co-operates with other factors to induce Legionella pneumophila virulence in the stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1201-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandyopadhyay, P., and H. M. Steinman. 2000. Catalase-peroxidases of Legionella pneumophila: cloning of the katA gene and studies of KatA function. J. Bacteriol. 182:6679-6686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bandyopadhyay, P., and H. M. Steinman. 1998. Legionella pneumophila catalase-peroxidases: cloning of the katB gene and studies of KatB function. J. Bacteriol. 180:5369-5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger, K. H., and R. R. Isberg. 1993. Two distinct defects in intracellular growth complemented by a single genetic locus in Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 7:7-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger, K. H., J. J. Merriam, and R. R. Isberg. 1994. Altered intracellular targeting properties associated with mutations in the Legionella pneumophila dotA gene. Mol. Microbiol. 14:809-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brand, B. C., A. Sadosky, and H. A. Shuman. 1994. The Legionella pneumophila icm locus: a set of genes required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 14:797-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brieland, J., M. McClain, M. LeGendre, and C. Engleberg. 1997. Intrapulmonary Hartmannella vermiformis: a potential niche for Legionella pneumophila replication in a murine model of legionellosis. Infect. Immun. 65:4892-4896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks, S. E., and D. L. Schneider. 1985. Oxidative metabolism associated with phagocytosis in Acanthamoeba castellanii. J. Protozool. 32:330-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrne, B., and M. S. Swanson. 1998. Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect. Immun. 66:3029-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carratala, J., F. Gudiol, R. Pallares, J. Dorca, R. Verdaguer, J. Ariza, and F. Manresa. 1994. Risk factors for nosocomial Legionella pneumophila pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 149:625-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catrenich, C. E., and W. Johnson. 1989. Characterization of the selective inhibition of growth of virulent Legionella pneumophila by supplemented Mueller-Hinton medium. Infect. Immun. 57:1862-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen, J. W., Y. Cha, K. U. Yuksel, R. W. Gracy, and J. T. August. 1988. Isolation and sequencing of a cDNA clone encoding lysosomal membrane glycoprotein mouse LAMP-1. Sequence similarity to proteins bearing onco-differentiation antigens. J. Biol. Chem. 263:8754-8758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cianciotto, N. P. 2001. Pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:331-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies, B., L. S. Chattings, and S. W. Edwards. 1991. Superoxide generation during phagocytosis by Acanthamoeba castellanii: similarities to the respiratory burst of immune phagocytes. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:705-710. [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Jonckheere, J., and H. van de Voorde. 1976. Differences in destruction of cysts of pathogenic and nonpathogenic Naegleria and Acanthamoeba by chlorine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 31:294-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dukan, S., and T. Nystrom. 1999. Oxidative stress defense and deterioration of growth-arrested Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26027-26032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelstein, P. H., M. A. Edelstein, F. Higa, and S. Falkow. 1999. Discovery of virulence genes of Legionella pneumophila by using signature tagged mutagenesis in a guinea pig pneumonia model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8190-8195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feeley, J. C., R. J. Gibson, G. W. Gorman, N. C. Langford, J. K. Rasheed, D. C. Mackel, and W. B. Baine. 1979. Charcoal-yeast extract agar: primary isolation medium for Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 10:437-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao, L. Y., O. S. Harb, and Y. Abu Kwaik. 1997. Utilization of similar mechanisms by Legionella pneumophila to parasitize two evolutionarily distant host cells, mammalian macrophages and protozoa. Infect. Immun. 65:4738-4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao, L. Y., O. S. Harb, and Y. A. Kwaik. 1998. Identification of macrophage-specific infectivity loci (mil) of Legionella pneumophila that are not required for infectivity of protozoa. Infect. Immun. 66:883-892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halablab, M. A., M. Bazin, L. Richards, and J. Pacy. 1990. Ultra-structure and localisation of formazan formed by human neutrophils and amoebae phagocytosing virulent and avirulent Legionella pneumophila. FEMS Microbiol. Immunol. 2:295-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hales, L. M., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Legionella pneumophila contains a type II general secretion pathway required for growth in amoebae as well as for secretion of the Msp protease. Infect. Immun. 67:3662-3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hales, L. M., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. The Legionella pneumophila rpoS gene is required for growth within Acanthamoeba castellanii. J. Bacteriol. 181:4879-4889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammer, B. K., and M. S. Swanson. 1999. Co-ordination of Legionella pneumophila virulence with entry into stationary phase by ppGpp. Mol. Microbiol. 33:721-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammer, B. K., E. S. Tateda, and M. S. Swanson. 2002. A two-component regulator induces the transmission phenotype of stationary-phase Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 44:107-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilbi, H., G. Segal, and H. A. Shuman. 2001. Icm/dot-dependent upregulation of phagocytosis by Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 42:603-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horwitz, M. A. 1987. Characterization of avirulent mutant Legionella pneumophila that survive but do not multiply within human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 166:1310-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horwitz, M. A., and S. C. Silverstein. 1983. Intracellular multiplication of Legionnaires' disease bacteria (Legionella pneumophila) in human monocytes is reversibly inhibited by erythromycin and rifampin. J. Clin. Investig. 71:15-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunziker, W., and H. J. Geuze. 1996. Intracellular trafficking of lysosomal membrane proteins. Bioessays 18:379-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs, R. F., R. M. Locksley, C. B. Wilson, J. E. Haas, and S. J. Klebanoff. 1984. Interaction of primate alveolar macrophages and Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Investig. 73:1515-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joshi, A. D., S. Sturgill-Koszycki, and M. S. Swanson. 2001. Evidence that Dot-dependent and -independent factors isolate the Legionella pneumophila phagosome from the endocytic network in mouse macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 3:99-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirby, J. E., and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Legionnaires' disease: the pore macrophage and the legion of terror within. Trends Microbiol. 6:256-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirby, J. E., J. P. Vogel, H. L. Andrews, and R. R. Isberg. 1998. Evidence for pore-forming ability by Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 27:323-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kura, F., K. Suzuki, H. Watanabe, Y. Akamatsu, and F. Amano. 1994. Difference in Legionella pneumophila growth permissiveness between J774.1 murine macrophage-like JA-4 cells and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-resistant mutant cells, LPS1916, after stimulation with LPS. Infect. Immun. 62:5419-5423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch, R. E., and I. Fridovich. 1978. Effects of superoxide on the erythrocyte membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 253:1838-1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marra, A., S. J. Blander, M. A. Horwitz, and H. A. Shuman. 1992. Identification of a Legionella pneumophila locus required for intracellular multiplication in human macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:9607-9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marston, B. J., H. B. Lipman, and R. F. Breiman. 1994. Surveillance for Legionnaires' disease. Risk factors for morbidity and mortality. Arch. Intern. Med. 154:2417-2422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLean, I. W., and P. K. Nakane. 1974. Periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde fixative. A new fixation for immunoelectron microscopy. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 22:1077-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 43.Moffat, J. F., and L. S. Tompkins. 1992. A quantitative model of intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila in Acanthamoeba castellanii. Infect. Immun. 60:296-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Molmeret, M., and Y. Abu Kwaik. 2002. How does Legionella pneumophila exit the host cell? Trends Microbiol. 10:258-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moreau, P. L., F. Gerard, N. W. Lutz, and P. Cozzone. 2001. Non-growing Escherichia coli cells starved for glucose or phosphate use different mechanisms to survive oxidative stress. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1048-1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagai, H., J. C. Kagan, X. Zhu, R. A. Kahn, and C. R. Roy. 2002. A bacterial guanine nucleotide exchange factor activates ARF on Legionella phagosomes. Science 295:679-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagai, H., and C. R. Roy. 2001. The DotA protein from Legionella pneumophila is secreted by a novel process that requires the Dot/Icm transporter. EMBO J. 20:5962-5970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nystrom, T. 1999. Starvation, cessation of growth and bacterial aging. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:214-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pedersen, L. L., M. Radulic, M. Doric, and Y. Abu Kwaik. 2001. HtrA homologue of Legionella pneumophila: an indispensable element for intracellular infection of mammalian but not protozoan cells. Infect. Immun. 69:2569-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rabinowitz, S., H. Horstmann, S. Gordon, and G. Griffiths. 1992. Immunocytochemical characterization of the endocytic and phagolysosomal compartments in peritoneal macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 116:95-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rogers, J., A. B. Dowsett, P. J. Dennis, J. V. Lee, and C. W. Keevil. 1994. Influence of temperature and plumbing material selection on biofilm formation and growth of Legionella pneumophila in a model potable water system containing complex microbial flora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1585-1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rogers, J., and C. W. Keevil. 1992. Immunogold and fluorescein immunolabelling of Legionella pneumophila within an aquatic biofilm visualized by using episcopic differential interference contrast microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2326-2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossier, O., and N. P. Cianciotto. 2001. Type II protein secretion is a subset of the PilD-dependent processes that facilitate intracellular infection by Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun 69:2092-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rowbotham, T. J. 1986. Current views on the relationships between amoebae, legionellae and man. Isr. J. Med. Sci. 22:678-689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rowbotham, T. J. 1983. Isolation of Legionella pneumophila from clinical specimens via amoebae, and the interaction of those and other isolates with amoebae. J. Clin. Pathol. 36:978-986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowbotham, T. J. 1980. Preliminary report on the pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila for freshwater and soil amoebae. J. Clin. Pathol. 33:1179-1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roy, C. R. 2002. The Dot/lcm transporter of Legionella pneumophila: a bacterial conductor of vesicle trafficking that orchestrates the establishment of a replicative organelle in eukaryotic hosts. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:463-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sadosky, A. B., L. A. Wiater, and H. A. Shuman. 1993. Identification of Legionella pneumophila genes required for growth within and killing of human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 61:5361-5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sadosky, A. B., J. W. Wilson, H. M. Steinman, and S. H. A. 1994. The iron superoxide dismutase of Legionella pneumophila is essential for viability. J. Bacteriol. 176:3790-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Samrakandi, M. M., S. L. Cirillo, D. A. Ridenour, L. E. Bermudez, and J. D. Cirillo. 2002. Genetic and phenotypic differences between Legionella pneumophila strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1352-1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seaver, L. C., and J. A. Imlay. 2001. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:7173-7181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seaver, L. C., and J. A. Imlay. 2001. Hydrogen peroxide fluxes and compartmentalization inside growing Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:7182-7189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Segal, G., and H. A. Shuman. 1998. How is the intracellular fate of the Legionella pneumophila phagosome determined? Trends Microbiol. 6:253-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Segal, G., and H. A. Shuman. 1999. Legionella pneumophila utilizes the same genes to multiply within Acanthamoeba castellanii and human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 67:2117-2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sexton, J. A., and J. P. Vogel. 2002. Type IVB secretion by intracellular pathogens. Traffic 3:178-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skinner, A. R., C. M. Anand, A. Malic, and J. B. Kurtz. 1983. Acanthamoebae and environmental spread of Legionella pneumophila. Lancet ii:289-290. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.St. John, G., and H. M. Steinman. 1996. Periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Legionella pneumophila. A role in stationary phase survival. J. Bacteriol. 178:1578-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sturgill-Koszycki, S., and M. S. Swanson. 2000. Legionella pneumophila replication vacuoles mature into acidic, endocytic organelles. J. Exp. Med. 192:1261-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Swanson, M. S., and E. Fernandez-Moreia. 2002. A microbial strategy to multiply in macrophages: the pregnant pause. Traffic 3:170-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swanson, M. S., and B. K. Hammer. 2000. Legionella pneumophila pathogenesis: a fateful journey from amoebae to macrophages. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:567-613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Swanson, M. S., and R. R. Isberg. 1995. Association of Legionella pneumophila with the macrophage endoplasmic reticulum. Infect. Immun. 63:3609-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Swanson, M. S., and R. R. Isberg. 1996. Identification of Legionella pneumophila mutants that have aberrant intracellular fates. Infect. Immun. 64:2585-2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vogel, J. P., C. Roy, and R. R. Isberg. 1996. Use of salt to isolate Legionella pneumophila mutants unable to replicate in macrophages. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 797:271-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Watarai, M., I. Derre, J. Kirby, J. D. Growney, W. F. Dietrich, and R. R. Isberg. 2001. Legionella pneumophila is internalized by a macropinocytotic uptake pathway controlled by the Dot/Icm system and the mouse Lgn1 locus. J. Exp. Med. 194:1081-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wiater, L. A., A. B. Sadosky, and H. A. Shuman. 1994. Mutagenesis of Legionella pneumophila using Tn903dIIlacZ: identification of a growth-phase-regulated pigmentation gene. Mol. Microbiol. 11:641-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamamoto, Y., T. W. Klein, C. A. Newton, R. Widen, and H. Friedman. 1988. Growth of Legionella pneumophila in thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages from A/J mice. Infect. Immun. 56:370-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zuckman, D. M., J. B. Hung, and C. R. Roy. 1999. Pore-forming activity is not sufficient for Legionella pneumophila phagosome trafficking and intracellular growth. Mol. Microbiol. 32:990-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zusman, T., O. Gal-Mor, and G. Segal. 2002. Characterization of a Legionella pneumophila relA insertion mutant and roles of RelA and RpoS in virulence gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 184:67-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]