Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to determine whether physicians’ treatment preferences are influenced by patients’ age.

Methods

We mailed a survey to a random sample of rheumatologists practicing in the U.S. The survey included a scenario describing a hypothetical patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and low dose prednisone, who presents with active disease during a follow-up appointment. The scenario was formulated in two versions which were identical except for the age of the patient. After reading the scenario, respondents were asked to rate (on a 10 cm numerical rating scale) their recommendations for each of the three options: 1) increasing the dose of prednisone, 2) adding a new disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD), and 3) switching DMARDs. Rheumatologists who rated either adding a new DMARD or switching DMARDs higher than increasing the dose of prednisone were classified as “preferring aggressive treatment with DMARDs”, while the remaining rheumatologists were classified as “NOT preferring aggressive treatment with DMARDs”.

Results

480 rheumatologists were mailed a questionnaire; 204 responded for a response rate of 42.5%. Overall 163 (80%) of respondents were classified as preferring aggressive treatment with DMARDs. Rheumatologists responding to this survey were more likely to prefer aggressive DMARD treatment for the young RA patient versus the older RA patient (87% versus 71%, p=0.007).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that rheumatologists’ treatment recommendations may be influenced by age. Future educational efforts should increase physician awareness of this possible bias in order to ensure equal service delivery across ages.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs, Decision-making

Current treatment guidelines for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) emphasize the need for aggressive management of active disease with one or more disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (1). This recommendation is based on a body of literature demonstrating that aggressive treatment is associated with better long-term outcomes (1). There is no evidence that the overall benefits of DMARD therapy are related to patients’ age. Yet, a large, population-based study found that the time to initiate DMARD therapy was longer, and the number of DMARDs received was less for older versus younger patients (2). Similarly, Tuntucu et al (3) recently found that older RA patients with disease onset after 60 years receive biologic therapy and combination therapy less frequently than patients with disease onset between ages 40 and 60 years (p<0.0001). A small single site study, however, found no differences in types of DMARDs used across age groups (4).

Lower utilization of DMARD therapy among older patients may be due to patients’ and/or physicians’ treatment preferences. Regarding the former, older patients may be more risk averse and less willing to accept the risk of drug toxicity compared to younger patients. Patients’ perceptions of physicians’ treatment recommendations have also been shown to differ by age, and may help explain why older patients receive less aggressive care (5). Alternatively, differences in the use of DMARDs across age groups may be due, in part, to age bias.

Age bias refers to the observation that older patients are not as likely to receive medical interventions as younger patients with comparable disease severity. This discrepancy in the delivery of healthcare has been demonstrated in diverse areas including oncology (6, 7) and cardiovascular disease (8, 9), but has not been well-studied in RA. Given this background, the objective of this study was to determine whether, after controlling for other patient-related factors, rheumatologists’ treatment preferences are influenced by age. We chose to examine the influence of patients’ age on physicians’ practices using standardized scenarios because this method provides a controlled experimental setting in which we were able to manipulate the variable of interest (i.e. age) while controlling for other important confounders.

METHODS

Survey

We mailed a survey to a random sample of rheumatologists practicing adult rheumatology in the U.S. The random sample was obtained by assigning a number to consecutive rheumatologists practicing adult rheumatology listed in the American College of Rheumatology Directory. From this list, a random sample was obtained using a random number table. The survey consisted of a scenario describing a hypothetical patient with RA on hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and low dose prednisone, who presents with active disease during a follow-up appointment. The scenario was formulated in two versions which were identical except for the age of the patient. Each rheumatologist was mailed one version of the scenario. Scenarios were classified by version (i.e. young versus older RA patient) and assignment of scenarios was determined using a computer-generated randomization sequence (Microsoft® Excel 2002).

Half of the respondents received a scenario containing the following information: “Mr. T. is an 82 year old man with rheumatoid factor positive RA diagnosed approximately 15 months ago. His disease has been well controlled with low dose prednisone and the combination of hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine (2 grams BID) (10). He does not take NSAIDs because they upset his stomach. Today, during a routine follow-up visit, he complains of increased pain in his finger joints. The review of symptoms is otherwise negative apart from increased morning stiffness lasting up to 1.5 hours (baseline = 20 to 30 minutes). General physical examination is unremarkable except for moderate synovitis involving the 2nd and 3rd MCPs (metacarpophalangeal joints) bilaterally. Lab tests from this morning: Normal CBC, SMA7, LFT, TSH, ESR =45.”

The remaining rheumatologists received the same scenario except that the patient’s age was 28 years old. Photographs of an older adult and young man sitting with the same physician were inserted into the old and young patient scenarios respectively.

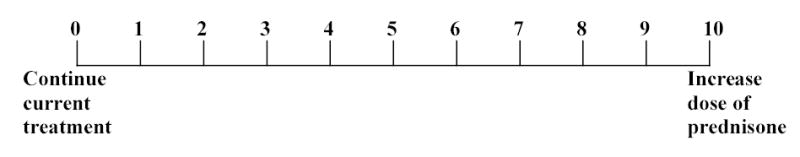

After reading the scenario, respondents were asked to rate (on a 10 cm numerical rating scale (11)) their recommendations for each of the three options: 1) increasing the dose of prednisone, 2) adding a new DMARD, and 3) switching DMARDs. An example of the scale used is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of rating scale used.

Respondents were also asked to indicate the number of years in practice, their gender, their type of practice, and how they spend the majority of their time. No reminders were sent and each rheumatologist received only one mailing. Surveys were returned anonymously in preaddressed stamped envelopes.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to describe the physicians’ characteristics. Median values and ranges are presented because the distributions of preferences were not normally distributed. Rheumatologists who rated either adding a new DMARD or switching DMARDs higher than increasing the dose of prednisone were classified as “preferring aggressive treatment with DMARDs”, while the remaining rheumatologists were classified as “NOT preferring aggressive treatment with DMARDs”. The association of treatment preference with age was ascertained using the chi-square statistic. We also examined the association of treatment preference with physicians’ characteristics using the chi-square statistic and the Mann-Whitney test for categorical and non-parametric data respectively. Multivariate analyses were subsequently performed using multiple logistic regression. This protocol was approved by the Human Investigations Committee at our institution.

RESULTS

480 rheumatologists were mailed a questionnaire; 204 responded for a response rate of 42.5%. Ninety-one scenarios describing the older patient and 113 scenarios describing the younger patient were returned. Seventy-four percent of the respondents were male; 84% spent the majority of their time in adult patient care, 20% were based at academic centers, and the median number of years in practice was 18 (range 2 to 53). Because questionnaires were returned anonymously, we do not have any information on the non-responders. However, a comparison of the demographic characteristics of this study sample with that of a larger recently published survey on biologic drug use in rheumatoid arthritis (12) are provide in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study sample vs larger survey of US rheumatologists.

| Characteristic | Age Bias Survey | Biologic Drug Use Survey (12) |

|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 74 | 72 |

| Academic – based (%) | 20 | 36 |

| Number of years in practice (%) | ||

| 0 – 10 | 26 | 29 |

| 11 – 20 | 34 | 33 |

| >20 | 40 | 38 |

The median (interquartile range) willingness to increase the dose of prednisone was 2 (0 to 7), to prescribe an additional DMARD was 5 (0 to 9), and to switch DMARDS was 6 (1 to 9). Overall 163 (80%) of respondents were classified as preferring aggressive treatment with DMARDs.

In bivariate analyses, rheumatologists responding to this survey were more likely to prefer aggressive DMARD treatment for the young RA patient versus the older RA patient (87% versus 71%, p=0.007). In addition to patients’ age, physician gender and number of years in practice were also associated with preference for aggressive therapy in bivariate analyses. Ninety-four percent (N=50) of the female rheumatologists preferred aggressive DMARD treatment compared to 74% (N=109) of the male physicians (p=0.002). The median number of years in practice was less among physicians preferring aggressive DMARD therapy compared to those not preferring aggressive therapy (17 versus 23 years, p<0.05).

In a logistic regression model evaluating the preceding covariates (patients’ age, physician gender, number of years in practice), patient’s age [adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) = 3.0 (1.4–6.2)] and physician gender [adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) = 5.4 (1.5–19.2)] remained associated with preference for aggressive DMARD therapy.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that rheumatologists were more likely to recommend aggressive treatment for a young RA patient compared to an older RA patient with the same disease activity and co-morbidities. These results may help explain why Kremers et al (2) and Tuntucu et al (3) found that older adults with RA were less aggressively treated compared to their younger counterparts. Our results also suggest that age bias may be stronger among male than female physicians. This finding is consistent with some studies demonstrating that women tend to have fewer systematic biases towards the elderly than do men (13). As in a study by Gruppen et al (14), we also found that younger physicians were more likely to favor “aggressive” treatment for older adults. This result did not reach statistical significance when controlled for other covariates, perhaps because of small numbers.

This study does have important limitations. First, we chose not to send reminders and second mailings, in order to respect physicians’ right to refuse participation, and as a result achieved a participation rate of 42.5%. This response rate, however, is consistent with (12, 15), or better than (16), previous surveys of rheumatologists in the US. In addition, because the questionnaires were returned anonymously, we do not have any information on the non-responders. Nonetheless, some demographic characteristics of the responders are similar to a recent large survey conducted on the same population (12).

In order to limit the number of potential influences on physician behavior, we did not vary patient gender in the scenarios. However, gender has been shown to effect health care in other fields (17, 18). In addition, we did not have a large enough sample size to examine all associations between physicians’ characteristics and age bias. Though in practice, efforts to reduce age bias in rheumatologists would most likely be directed at a general population of practicing clinicians and not specific subgroups.

Age bias in medicine is a well-recognized problem in heath care delivery and has received considerable attention in fields such as oncology and cardiovascular disease, but has not been well-studied in rheumatology (6–9, 19–24). The results of this study, along with other evidence (2, 3), suggest that underutilization of DMARDs in older adults may be partially explained by age bias. Examining this bias as an influence on physicians’ treatment recommendations is particularly important in RA given that the incidence of RA increases with age and the proportion of older adults is steadily growing. Future educational efforts should increase physician awareness of this possible bias in order to ensure equal service delivery across ages.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants for their time and effort. The corresponding author had full access to all the data and takes full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. There are no potential conflicts or overlap with other publications to the best of our knowledge. The authors do not have any financial interests that would be considered a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Dr. Fraenkel is supported by the K23 Award AR048826-01 A1.

Contributor Information

Liana Fraenkel, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, Yale University School of Medicine,.

Nicole Rabidou, Yale University School of Medicine..

Ravi Dhar, Yale University School of Management..

References

- 1.O'Dell JR. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2591–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kremers HM, Nicola P, Crowson CS, O'Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Therapeutic strategies in rheumatoid arthritis over a 40-year period. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2366–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tutuncu Z, Reed G, Kremer J, Kavanaugh A. Do patients with older onset rheumatoid arthritis receive less aggressive treatment than younger patients? Ann Rheum Dis 2006:doi:10.1136/ard.2005.051144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Harrison MJ, Kim CA, Silverberg M, Paget SA. Does age bias the aggressive treatment of elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis? J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1243–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson MF, Lin M, Mangalik S, Murphy DJ, Kramer AM. Patients' perceptions of physicians' recommendations for comfort care differ by patient age and gender. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:248–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2000.07004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodard S, Nadella PC, Kotur L, Wilson J, Burak WE, Shapiro CL. Older women with breast carcinoma are less likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy: evidence of possible age bias? Cancer. 2003;98:1141–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alibhai SM, Krahn MD, Cohen MM, Fleshner NE, Tomlinson GA, Naglie G. Is there age bias in the treatment of localized prostate carcinoma? Cancer. 2004;100:72–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurwitz JH, Osganian V, Goldberg RJ, Chen ZY, Gore JM, Alpert JS. Diagnostic testing in acute myocardial infarction: does patient age influence utilization patterns? Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:948–57. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yarzebski J, Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS. Temporal trends and factors associated with pulmonary artery catheterization in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chest. 1994;105:1003–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Dell JR, Haire CE, Erikson N, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate alone, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine, or a combination of all three medications. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1287–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605163342002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollen PJ, Gralla RJ, Kris MG, McCoy S, Donaldson GW, Moinpour CM. A comparison of visual analogue and numerical rating scale formats for the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale (LCSS): does format affect patient ratings of symptoms and quality of life? Qual Life Res. 2005;14:837–47. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0833-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cush JJ. Biological drug : US perspectives on indications and monitoring. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:iv18–iv23. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.042549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rupp DE, Vodanocih SJ, Crede M. The multidimensional nature of ageism: construct validity and group differences. J Soc Psychol. 2005;145:335–62. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.145.3.335-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruppen LD, Wolf FM, Van Voorhees CJKS. The influence of general and case-related experience on primary care treatment decision making . Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2657–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazici Y, Erkan D, Paget SA. Monitoring by rheumatologists for methotrexate, etanercept, infliximab, and anakinra-associated adverse effects. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2769–72. doi: 10.1002/art.11277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfe F, Albert DA, Pincus T. A survey of United States rheumatologists concerning effectiveness of disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and prednisone in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:375–81. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blum M, Slade M, Boden D, Cabin H, CaulinGlaser T. Examination of gender bias in the evaluation and treatment of angina pectoris by cardiologists. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:765–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauer M, Pashkow F, Snader C, Harvey S, Thomas J, Marwick T. Gender and referral for coronary angiography after treadmill thallium testing. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:278–83. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Witt JD. Age bias and choice of intervention for treatment of avascular necrosis. J Bone Jt Surg. 2000;82–A(12):1805–6. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200012000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams D, Bennett K, Feely J. Evidence for an age and gender bias in the secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:604–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madan AK, Aliabadi-Wahle S, Beech DJ. Age bias: a cause of underutilization of breast conservation treatment. J Cancer Educ. 2001;16:29–32. doi: 10.1080/08858190109528720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madan AK, Aliabadi-Wahle S, Beech DJ. Ageism in medical students' treatment recommendations: the example of breast-conserving procedures. Acad Med. 2001;76:282–4. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200103000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plaisier BR, Blostein PA, Hurt KJ, Malangoni MA. Withholding/withdrawal of life support in trauma patients: is there an age bias? Am Surgeon. 2002;68:159–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rybarczyk B, Haut A, Lacey RF, Fogg LF, Nicholas JJ. A multifactorial study of age bias among rehabilitation professionals. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2001;82:625–32. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.20834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]