Abstract

Background

Through the AMI-QUEBEC Study we sought to describe delays to reperfusion therapy for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and to identify factors associated with prolonged delays.

Methods

We reviewed the charts of all consecutive patients with STEMI admitted to 17 hospitals in the province of Quebec in 2003 to obtain data on the time from presentation to reperfusion therapy. Data were available for 1189 (83.0%) of 1432 patients.

Results

The median delay to reperfusion therapy was 32 minutes (first and third quartile [Q1, Q3] 20, 49) for 535 patients who received fibrinolytic therapy, 109 minutes (Q1, Q3 79, 150) for 455 patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) at the initial hospital of presentation and 142 minutes (Q1, Q3 115, 194) for 199 patients who underwent primary PCI after an interhospital transfer. Patients who presented outside daytime working hours, those who received primary PCI and those who required interhospital transfer for primary PCI were less likely to receive reperfusion therapy within current recommended times (odds ratios [ORs] 0.49, 0.56 and 0.15, respectively). Increased age was associated with prolonged delays only among patients who received fibrinolytic therapy (OR for each 10-year increase in age 0.95, 95% credible interval [CrI] 0.93–0.99 for fibrinolytic therapy and 0.99, 95% CrI 0.95–1.05, for primary PCI).

Interpretation

In 2003, many patients with STEMI in Quebec were not treated within the recommended times. Delays may be reduced by reorganizing pre- and in-hospital care for patients with STEMI to expedite delivery of reperfusion therapy.

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is most often caused by thrombosis in a coronary artery. Reperfusion therapy with either fibrinolytic therapy or primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) aims to restore coronary artery blood flow. Regardless of the method used, prolonged delays to reperfusion therapy are associated with an increased risk of impaired left ventricular systolic function and death.1–11 Current international guidelines recommend that times from arrival at hospital to administration of reperfusion therapy should be within 30 minutes for fibrinolytic therapy (i.e., door-to-needle time) and within 90 minutes for primary PCI (i.e., door-to-balloon time).12–14

One study from the United States reported that the amount of time to fibrinolytic therapy has increased with more frequent use of primary PCI.15 We undertook a systematic literature review that did not identify any published data on the effects of increased use of primary PCI in Canada. (The search strategy for the literature review is explained in Appendix 1, available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/175/12/1527/DC1.) The objectives of the AMI-QUEBEC Study were to describe delays to reperfusion therapy in selected hospitals in the province of Quebec and to identify factors associated with failure to receive reperfusion therapy within current recommended times.

Methods

The AMI-QUEBEC Study was a retrospective study of consecutive patients with STEMI admitted to selected hospitals in the province of Quebec in 2003. Hospitals that had a minimum of 100 patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) admitted annually16 and research personnel available in the cardiology or emergency departments were invited to participate. We reviewed the charts of all consecutive patients with a final principal discharge diagnosis of AMI, including both patients with and without STEMI (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, code 410),17 who were admitted to participating hospitals from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2003. (The definitions used in the study appear in Appendix 2, available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/175/12/1527/DC1.)

To be included in the analysis, patients must have presented with symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia with a minimum duration of 20 minutes and an ST-segment elevation of at least 1 mm in 2 or more contiguous electrocardiogram (ECG) leads or new left bundle branch block. In addition, the diagnosis of STEMI must have been confirmed by an emergency physician or cardiologist. We excluded patients with STEMI that developed in hospital, those with a prior STEMI already recorded in the AMI-QUEBEC database, patients who did not receive reperfusion therapy and those whose AMI symptoms lasted more than 12 hours (since reperfusion therapy is generally not recommended for these patients12–14).

Approval for the AMI-QUEBEC Study was obtained at all participating hospitals from the directors of professional services or the institutional review boards.

Data abstractors received 7 hours of intensive training on chart review and electronic case reporting. All electronic case report forms were reviewed at the coordinating centre. Queries concerning inconsistencies and inaccuracies were sent electronically to the data abstractors at participating hospitals for clarification. There were 308 queries. Most involved inconsistencies in the entry of dates (e.g., date–month–year instead of month–date–year). Age was entered incorrectly for 2 patients. Eight queries were related to patients who were duplicated in the database (2 duplicate entries, 3 reinfarctions in the same patients and 3 transferred patients). Because of funding constraints, we could not examine the reliability of either the data abstraction procedures or entry of this information into the electronic case report forms.

The dependent variable, timely administration of reperfusion therapy, was defined as door-to-needle time within 30 minutes for fibrinolytic therapy (yes, no) or door-to-balloon time within 90 minutes for primary PCI (yes, no). Potential determinants to be investigated were identified ahead of time and included age, sex, duration of AMI symptoms, previous MI, STEMI that involved the anterior wall, STEMI that occurred during the winter months, presentation at hospital during holidays or on weekends, presentation at hospital outside daytime working hours (between 5:00 pm and 8:00 am), method of reperfusion, thrombolysis in MI (TIMI) score,18 presence of cardiogenic shock and interhospital transfer for primary PCI. Cardiogenic shock was defined as a systemic blood pressure of less than 90 mm Hg on presentation at the initial hospital and signs of low cardiac output (e.g., decreased urine output or altered mental status).

As a preliminary step, several fixed-effects nonhierarchical logistic regression models were fitted with variables selected according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC).19 We included any variable that appeared at least once in any of the 5 models with the highest posterior probabilities according to the BIC. The BIC was computed using the “bic.glm” function, which is an add-on to R version 2.1.1 (http//probability.ca/cran, accessed 2003 Oct 11).

A hierarchical logistic regression model was first fitted to estimate the probability of timely administration of reperfusion therapy among hospitals that participated in the AMI-QUEBEC Study. These estimates showed substantial interhospital variation. Since fixed-effects nonhierarchical models do not take interhospital variation into account,20 multilevel hierarchical models were fitted in the final analysis. In the 3-level hierarchical model, the unit of analysis at the first level of the hierarchy was the patient, and patient-related characteristics were entered at this level. The second level of analysis allowed us to estimate interhospital variability. At the third level, we set diffuse (noninformative) prior distributions over the unknown parameters, so that final conclusions were based mainly on the information contained in the data.

Hierarchical modeling was performed with the use of the complete AMI-QUEBEC data set. In subgroup analyses, random-effects hierarchical models were fitted for each treatment group (fibrinolytic therapy or primary PCI) separately. Identification of factors associated with use of primary PCI as the method of reperfusion and correlates of in-hospital mortality were undertaken using the same analytic strategy.

Results

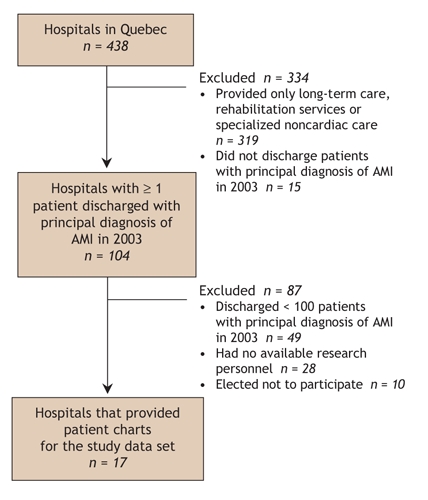

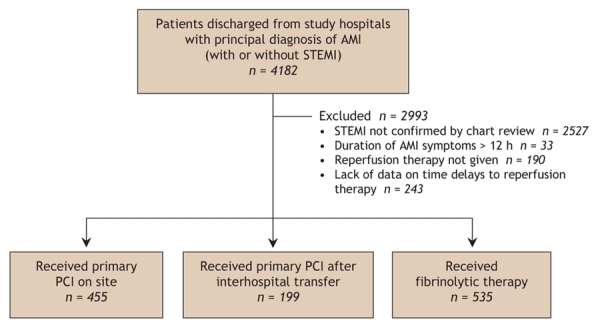

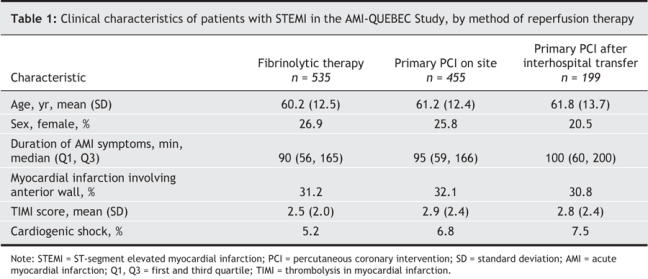

Seventeen hospitals participated in the AMI-QUEBEC Study (Fig. 1). (A complete list of the hospitals, and a list of investigators and coordinators who participated in the study, appears in Appendix 3, available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/175/12/1527/DC1.) A total of 4182 consecutive AMI patients (including those with and without STEMI) were discharged from the hospitals from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31, 2003 (Fig. 2). A diagnosis of STEMI was confirmed through chart review in 1655 of the 4182 patients. We excluded 33 patients whose AMI symptoms lasted longer than 12 hours and 190 patients who did not receive any reperfusion therapy. Among the records for the 1432 remaining patients, 243 did not have complete data on time-to-reperfusion therapy. Thus, we were able to analyze the time to reperfusion therapy for 1189 (83.0%) of the patients who received reperfusion therapy. The characteristics of patients according to method of reperfusion are shown in Table 1. Patients who received primary PCI had a higher mean TIMI score, and more of these patients than of those who received fibrinolytic therapy were in cardiogenic shock. The proportion of patients who were women was lower in the group of patients transferred for primary PCI than in the group of patients who received either primary PCI on site or fibrinolytic therapy.

Fig. 1: Selection of hospitals for participation in the AMI-QUEBEC Study. AMI = acute myocardial infarction.

Fig. 2: Selection of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) with and without ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) discharged from the 17 study hospitals in 2003. PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 1

The median door-to-ECG times were 12 minutes (first quartile, third quartile [Q1, Q3] 5, 25) for patients who presented during regular working hours and 13 minutes (Q1, Q3 6, 28) for those presenting outside of regular working hours. The median door-to-ECG time was slightly lower among patients who underwent primary PCI than among those who received fibrinolytic therapy.

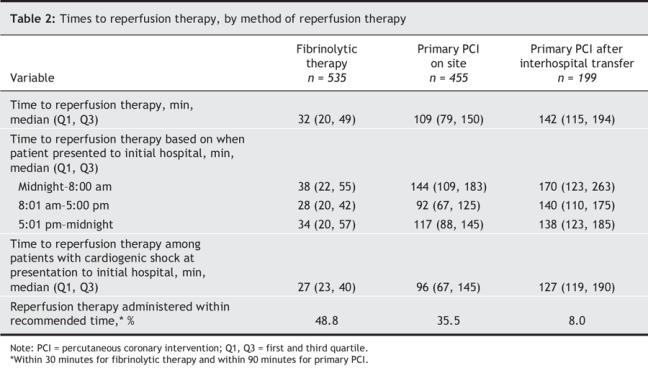

The delays to reperfusion therapy are shown in Table 2. Among the patients who received fibrinolytic therapy, the median door-to-needle time was 32 minutes; 48.8% of patients received the treatment within 30 minutes (Table 2). Among the patients who received primary PCI on site, the median door-to-balloon time was 109 minutes; 35.5% received treatment within 90 minutes and 59.5% received treatment within 120 minutes. Among the patients who underwent primary PCI after interhospital transfer, the median door-to-balloon time was 142 minutes; 8.0% received treatment within 90 minutes and 27.6% received treatment within 120 minutes (Table 2).

Table 2

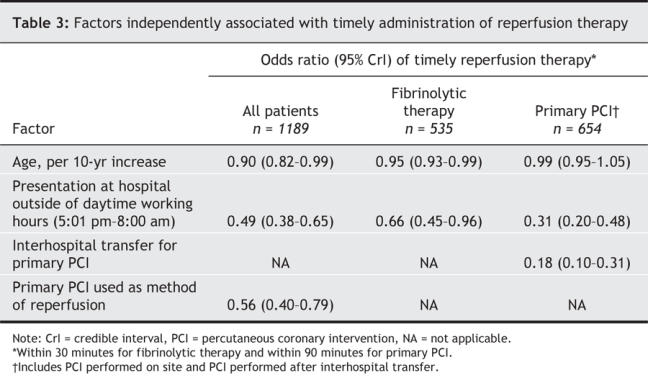

Factors associated with delayed administration of reperfusion therapy included presentation outside daytime working hours (51% decrease in odds of timely reperfusion), primary PCI as the method of reperfusion (44% decrease) and primary PCI after interhospital transfer (82% decrease) (Table 3). Increased age was associated with delayed administration of fibrinolytic therapy (Table 3). For every 10-year increase in age, there was a 5% decrease in the odds of patients receiving timely fibrinolytic therapy. Age was not independently associated with delayed primary PCI in the AMI-QUEBEC Study. Factors associated with the use of primary PCI as the method of reperfusion included availability of PCI facilities at the hospital where the patient first presented (odds ratio [OR] 28.1, 95% credible interval [CrI] 19.9–40.3), patient in cardiogenic shock (OR 2.7, 95% CrI 1.3–5.5) and presentation during daytime working hours (OR 1.5, 95% CrI 1.2–2.3).

Table 3

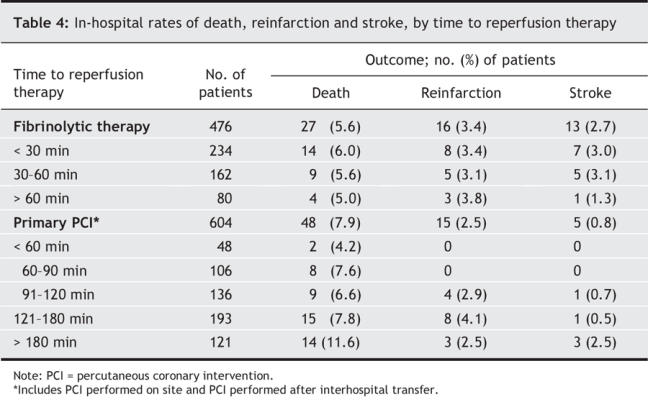

Complete data on in-hospital adverse events were available for 476 (89.0%) of the patients who received fibrinolytic therapy and 604 (92.4%) who received primary PCI. The in-hospital rate of death was higher among patients with prolonged delays to primary PCI (Table 4). However, delays to reperfusion therapy were not independently associated with in-hospital death after adjusting for patients' clinical characteristics (OR 0.98, 95% CrI 0.98–1.01 for time to fibrinolytic therapy and OR 1.00, 95% CrI 0.99–1.01 for time to primary PCI).

Table 4

Interpretation

Overall, the proportion of patients who received reperfusion therapy within recommended times in the AMI-QUEBEC Study was similar to that reported in 2002 in the United States.21 Almost half of the patients in our study who received fibrinolytic therapy were treated within 30 minutes. This represents a substantial improvement over the median door-to-needle time of 85 minutes reported during 1991/92, when only 3% of Canadian patients were treated within 30 minutes.22 However, the times to primary PCI for most patients exceeded current recommendations.

Increased age was associated with decreased odds of timely administration of reperfusion therapy for patients who received fibrinolytic therapy. Elderly patients with STEMI often have more atypical symptoms than younger patients.23,24 They are also at increased risk for intracranial hemorrhage and serious bleeding complications with fibrinolytic therapy.25,26 Concerns regarding serious bleeding complications may have contributed to delays in administering fibrinolytic therapy in elderly patients.

Patients who presented outside daytime working hours had longer delays for both methods of reperfusion therapy than did patients who presented during daytime working hours. The difference may have been due to reductions in emergency department personnel during off-hours, which might in turn generate delays in recognizing and treating STEMI. Furthermore, longer times to primary PCI among patients who presented outside daytime working hours can be attributed in part to the necessity of mobilizing PCI personnel from home. The prolonged delay for a majority of patients who underwent primary PCI, and especially those who required interhospital transfer, may be explained in part by the lack of structured prehospital and interhospital networks for treating STEMI in Quebec. Kalla and colleagues demonstrated that optimal times to reperfusion therapy can be achieved with a comprehensive regional network of prehospital medical services and hospitals designated for treatment of STEMI.27 The use of primary PCI as a reperfusion method was related to the presence of cardiogenic shock when the patient arrived at the hospital, availability of primary PCI at the hospital where the patient first presented and whether the patient presented to hospital during regular working hours. Furthermore, the adjusted OR for receiving primary PCI among women was 0.70 (95% CrI 0.48–1.01), which suggests that women may be at reduced odds of receiving primary PCI.

Although we did not observe an independent association between delays to reperfusion therapy and in-hospital death, our study was not designed to accurately assess these associations. The lack of association between delays to reperfusion therapy and in-hospital nonfatal reinfarction and stroke in our study is consistent with findings from a previous report.28

The following approaches may be useful in considering how to decrease delays to reperfusion therapy in Quebec. At all hospitals that provide care to patients with STEMI, streamlined treatment protocols should be considered to ensure that patients are given reperfusion therapy expeditiously.29–31 Emergency departments should have adequate personnel outside of daytime working hours to enable prompt identification and treatment of STEMI. At hospitals where primary PCI is the preferred treatment, the emergency physician should be able to contact PCI personnel directly without having to consult a cardiologist.31 When delays for primary PCI are expected to exceed 90 minutes, patients who do not have contraindications to fibrinolytic agents should receive fibrinolytic therapy.

Ongoing surveillance of delays to reperfusion therapy should be also established in Quebec. Continuous monitoring may help to identify obstacles to timely administration of reperfusion therapy and may reduce delays.32,33 Finally, it should be noted that the recommended times to reperfusion therapy may not be realistic or relevant in certain situations, including life-threatening complications of STEMI that require specific medical interventions, uncertainty about the diagnosis and delays associated with the informed choice of therapy by the patient.

Our study had a few limitations. First, the external generalizability of the findings may be limited. The total number of patients with AMI admitted to hospitals participating in the AMI-QUEBEC Study represented 38.8% of all such hospital admissions in Quebec in 2003.16 Our results might not be generalizable to hospitals with fewer than 100 AMI patients a year. Second, the method of data abstraction from hospital charts was not independently validated. However, all data abstractors received standardized training, and all case reports were systematically reviewed at the coordinating centre for inconsistencies and missing data. Third, data on delays to reperfusion therapy were missing or incomplete for 243 patients (17.0% of 1432 patients). Patients with missing data were more likely to have been transferred for primary PCI and to have presented outside daytime working hours, factors that were associated with prolonged delays. The median delays would likely have been longer had these patients been included in the analysis. Fourth, 2 of the 10 hospitals with PCI facilities usually transferred patients back to referring hospitals immediately after uncomplicated primary PCI and admitted those with complications. The median times to primary PCI may have been longer at these 2 hospitals, if only “sicker” patients transferred from other hospitals were admitted. However, median door-to-balloon times did not change in an analysis that excluded patients who underwent primary PCI after interhospital transfers from these 2 hospitals. Finally, because this was an observational study, we were restricted to data available in hospital charts and therefore could not study all possible determinants of delays (e.g., hospital administrative policies, physician competence and cost).

Overall 48.8%, 35.5% and 8.0% of patients who received fibrinolytic therapy, on-site primary PCI and primary PCI after interhospital transfer were treated within current recommended times. There is potential for improvement in the administration of reperfusion therapy. Consideration should be given to reorganizing pre-and in-hospital care for patients with STEMI to expedite delivery of reperfusion therapy in Quebec.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this article to the memory of our colleague and AMI-QUEBEC Study investigator Dr. Franz Dauwe, who was an esteemed and compassionate cardiologist.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Thao Huynh was the principal investigator of the AMI-QUEBEC Study. All of the authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of the data, and the conception and critical review of the manuscript, and all approved the final version of the manuscript.

We thank all of the investigators and coordinators for their dedication to the AMI-QUEBEC Study (the names of the investigators and coordinators appear in Appendix 3, available online at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/175/12/1527/DC1). We also thank Drs. Richard Harvey, Louise Pilote, Gilles Paradis and Stéphane Perron for their invaluable input, and Axiom Real-Time Metrics for its expertise in creating and ensuring the integrity of the AMI-QUEBEC data capture tools and data set.

The AMI-QUEBEC Study was supported by Hoffmann-La Roche Pharma Canada; the company was not involved in the collection or analysis of the data or in the conception of the study. Jennifer O'Loughlin holds a Canada Research Chair in the Childhood Determinants of Adult Chronic Disease. Stéphane Rinfret is a junior clinician-scientist, and Mark Eisenberg is a senior clinician-scientist, of the Fond de la recherche en santé du Québec.

Competing interests: Thao Huynh received travel funding from Hoffmann-La Roche Pharma Canada to present the results of the AMI-QUEBEC Study at the 2005 Annual Meeting of the Association des Cardiologues du Québec. Simon Kouz owns stocks in Boston Scientific and Medtronic. He received a speaker fee from Hoffmann-La Roche Pharma Canada in the last 2 years. The other authors declared no competing interests.

Correspondence to: Dr. Thao Huynh, Department of Cardiology, Montreal General Hospital, Rm. e-5200, 1650 ave. Cedar, Montréal QC H3G 1A4; fax 514 934-8318; thao.huynhthanh@mail.mcgill.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Boersma E, Mass ACP, Deckers JW, et al. Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet 1996;348:771-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Brodie BR, Hansen C, Stuckey TD, et al. Door-to-balloon time with primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction impacts late cardiac mortality in high-risk patients and patients presenting early after the onset of symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:289-95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lundergan CF, Reiner JS, Ross AM. How long is too long? Association of time delay to successful reperfusion and ventricular function outcome in acute myocardial infarction. The case for thrombolytic therapy before planned angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2002;144:456-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Zijlstra F, et al.; ZWOLLE Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Symptom-onset-to-balloon time and mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:991-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Berger PB, Ellis SG, Holmes DR, et al. for the GUSTO-IIb investigators. Relationship between delay in performing direct coronary angioplasty and early clinical outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Results from the Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes (GUSTO-IIb) Trial. Circulation 1999;100:14-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT, et al. Relationship of symptom-onset-to-balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2000;283:2941-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Migliorini A, et al. Relation of time to treatment and mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 2002;89:1248-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Brodie BR, Stuckey TD, Muncy DB, et al. Importance of time-to-reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction with and without cardiogenic shock treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J 2003;145:708-15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.De Luca G, Ernst N, Suryapranata H, et al. Relation of interhospital delay and mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:1361-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Nallamothu BK, Bates ER. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction: is timing (almost) everything? Am J Cardiol 2003;92:824-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.McNamara RL, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Effect of door-to-balloon time on mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47:2180-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction) [published erratum in Circulation 2005;111:2013-4]. Circulation 2004;110:e82-292. [PubMed]

- 13.Bassand JP, Danchin N, Filippatos G, et al. Implementation of reperfusion therapy in acute myocardial infarction. A policy statement from the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2005;26:2733-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Canadian Working Group on treatment of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. The 2004 ACC/AHA Guidelines: a perspective and adaptation for Canada by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Working Group. Can J Cardiol 2004;20:1075-9. [PubMed]

- 15.Doorey A, Patel S, Reese C, et al. Dangers of delay of initiation of either thrombolysis or primary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction with increasing use of primary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 1998;81:1173-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Comité d'experts en hémodynamie du Réseau québecois de cardiologie tertiaire (RQCT). Le développement de l'hémodynamie au Québec: évaluation des besoins et proposition pour une utilisation optimale des ressources. Perspective 2005–2010. Québec: RQCT; 2005. Annexe 5. p. 79-82. Available: http://publications.msss.gouv.qc.ca/acrobat/f/documentation/2005/05-906-02.pdf (accessed 2006 Nov 6).

- 17.World Health Organization. International classification of diseases. Available: www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ (accessed 2006 Oct 17).

- 18.Morrow DA, Antman EM, Charlesworth A, et al. TIMI risk score for ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a convenient bedside, clinical score for risk assessment at presentation. Circulation 2000;102:2031-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes Factor. J Am Stat Assoc 1995;90:773-95.

- 20.Austin PC, Tu JV, Alter DAA. Comparing hierarchical modeling with traditional logistic regression analysis among patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: Should we be analyzing cardiovascular outcomes data differently? Am Heart J 2003;145:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.McNamara RL, Herrin J, Bradley EH, et al. Hospital improvement in time to reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction, 1999–2002. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:45-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Cox JL, Lee E, Langer A, et al. for the Canadian GUSTO investigators. Time to treatment with thrombolytic therapy: determinants and effect on short-term nonfatal outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. CMAJ 1997;156(4):497-505. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Boucher JM, Racine N, Huynh T, et al.; Quebec Acute Coronary Care Working Group. Age-related differences in in-hospital mortality and the use of thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. CMAJ 2001;164(9):1285-90. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Berger AK, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Factors associated with delay in reperfusion therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction: analysis of the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. Am Heart J 2000;139:985-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Huynh T, Cox JL, Massel D, et al. Predictors of intracranial hemorrhage with fibrinolytic therapy in unselected community patients: A report from the FASTRAK II project. Am Heart J 2004;148:86-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Brass LM, Lichtman JH, Wang Y, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage associated with thrombolytic therapy for elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. Stroke 2000;31:1802-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Kalla K, Christ G, Karnik R, et al. Implementation of guidelines improves the standard of care: the Viennese Registry on reperfusion strategies in ST-Elevation myocardial infarction (Vienna STEMI Registry). Circulation 2006;113:2398-405. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Goldberg RJ, Mooradd M, Gurwitz JH, et al. Impact of time to treatment with tissue plasminogen activator on morbidity and mortality following acute myocardial infarction (The Second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction). Am J Cardiol 1998;82:259-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Lambrew CT, Weaver WD, Rogers WJ, et al. Hospitals protocols and policies that may delay early identification and thrombolytic therapy of acute myocardial infarction patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis 1996;3:301-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Waters RE, Singh KP, Roe MT, et al. Rationale and strategies for implementing community-based transfer protocols for primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:2153-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Bradley EH, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, et al. Achieving door-to-balloon times that meet quality guidelines. How do successful hospitals do it. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:1236-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Caputo RP, Ho KKL, Stoler RC, et al. Effect of continuous quality improvement analysis on the delivery of primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:1159-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Shry EA, Eckhart RE, Winslow JB, et al. Effect of monitoring of physician performance on door-to-balloon time for primary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2003;91:867-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.