Abstract

A gene responsible for multidrug resistance was cloned from the chromosomal DNA of non-O1 Vibrio cholerae NCTC 4716 by using as a host drug-hypersensitive Escherichia coli strain KAM32, which lacks major multidrug efflux pumps. E. coli cells transformed with the gene showed elevated levels of resistance to a number of structurally dissimilar drugs, such as tetracycline, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, doxorubicin, daunomycin, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and Hoechst 33342. We determined the nucleotide sequence and found one open reading frame. We designated the gene vcaM. The deduced product, VcaM, seems to be a polypeptide with 619 amino acid residues (69 kDa) that has a putative topology of six transmembrane segments in the N-terminal hydrophobic domain, followed by an ATP binding domain in the C-terminal hydrophilic region. The sequence of VcaM was shown to be similar to those of human multidrug resistance proteins P-glycoprotein MDR1 and lactococcal LmrA, which are driven by ATP. The efflux of Hoechst 33342 and doxorubicin from cells possessing VcaM was detected. The efflux activity was inhibited by reserpine and sodium o-vanadate, which are potent inhibitors of MDR1 and LmrA. Thus, we conclude that VcaM is a member of the family of multidrug efflux pumps of the ATP binding cassette type and the first experimentally proven example of a multidrug efflux pump of this family in gram-negative bacteria.

The incidence of multidrug resistance is a serious medical problem that has significantly affected the treatment of infectious diseases (4, 29) and cancer (35). Multidrug efflux is one of the major mechanisms of drug resistance in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (38, 42) and is often associated with the enhanced expression of multidrug transport proteins (1, 27, 43). Most of the eukaryotic multidrug efflux pumps belong to the ATP binding cassette (ABC) family of transport proteins, while the prokaryotic systems are mainly secondary transporters (38). ABC multidrug transporters are involved in the tolerance of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes to a wide diversity of cytotoxic agents (37-39). The human multidrug resistance protein P-glycoprotein is an ATP-dependent drug efflux pump. The pump contains 1,280 amino acid residues and is organized as two tandem repeats, with each repeat consisting of a hydrophobic domain containing six predicted transmembrane segments followed by a hydrophilic domain containing an ATP binding site (19). Only two bacterial ABC drug transporters conferring multidrug resistance have been experimentally characterized in gram-positive bacteria, namely, LmrA of Lactococcus lactis (39) and HorA of Lactobacillus brevis (32). Both LmrA and HorA contain six transmembrane segments and a nucleotide-binding domain. Young and Holland (41) hypothesized that ABC drug exporters in gram-negative bacteria are redundant in the face of many alternative secondary drug efflux systems of extremely ancient origin. Recently, Kobayashi et al. (20) reported on a macrolide-specific ABC transporter in Escherichia coli. However, no functional ABC multidrug transporter has yet been definitively established to exist in gram-negative bacteria.

Vibrio cholerae, a gram-negative noninvasive enteric pathogen, is the causative agent of the severe diarrheal disease cholera. Cholera, which is caused by toxigenic and drug-resistant V. cholerae strains, is a major public health concern in developing countries of Asia and Africa (11). Fluid replacement is the most important component of therapy, but tetracycline and fluoroquinolone are routinely given to patients with cholera because they decrease the duration and volume of purging, as well as the duration of vibrio excretion (14, 40). Both clinical and environmental strains of V. cholerae (O1 and non-O1 strains) that are resistant to multiple antimicrobial agents are reported with increasing frequency (6, 8, 10, 12, 13). Even though some reports have demonstrated that the presence of antibiotic resistance genes in plasmids or integrons in V. cholerae were the cause of resistance to antimicrobial agents, the mechanism of resistance in other cases is unknown and remains to be elucidated (10, 36). The aim of this work is to elucidate the multidrug resistance systems in non-O1 V. cholerae strains. Thus, we investigated multidrug efflux pumps in this organism. Colmer et al. (7) characterized a multidrug efflux pump, VceAB, in V. cholerae, a homologue of EmrAB of E. coli, which belongs to the major facilitator superfamily. Recently, we cloned and charcterized two Na+-driven multidrug efflux pumps, VcmA and VcrM, from non-O1 V. cholerae strains (17, 18). Here we report on a novel ABC multidrug transporter, VcaM, from non-O1 V. cholerae. In addition to other drugs, tetracycline and fluoroquinolones are substrates of VcaM. Because both tetracycline and fluoroquinolones are commonly used for the treatment of cholera, the overexpression of VcaM would be a serious threat to patients infected with V. cholerae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Daunomycin, doxorubicin, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and sodium o-vanadate were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Hoechst 33342 was supplied by Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg. All other reagents were commercial products of reagent grade.

Bacterial strains and growth.

Non-O1 V. cholerae NCTC 4716 (generously provided by Sumio Shinoda, Department of Environmental Hygiene, Okayama University, Okayama, Japan) was used as the source of chromosomal DNA. E. coli strain KAM32 (ΔacrAB ΔydhE) (18) was used as a host for gene cloning. Non-O1 V. cholerae cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium (23), and E. coli cells were grown in Luria medium (L medium) (22) at 37°C. Cell growth was monitored turbidimetrically at 650 nm.

Gene cloning and sequencing.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared from the non-O1 V. cholerae cells by the method of Berns and Thomas (5). The DNA was partially digested with Sau3AI; and the fragments, which ranged in size from 4 to 10 kbp, were separated by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Plasmid pBR322 was digested with BamHI, dephosphorylated with bacterial alkaline phosphatase, and then ligated with the chromosomal DNA fragments by using a ligation kit (version 2; TaKaRa Co.). Competent cells of E. coli KAM32 were transformed with the recombinant plasmids and were spread onto agar plates containing L broth, 0.5 μg of DAPI per ml, 60 μg of ampicillin ml, and 1.5% agar, on which the host strain could not grow. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Candidate colonies were replica plated, and plasmids were isolated from each of the candidates. Plasmid DNA was reintroduced into KAM32 cells, and the cells were spread on the same plate. Plasmids were isolated from each of these transformants. One of the candidate plasmids possibly carrying the gene for DAPI resistance was denoted pDAV6. The insert in pDAV6 was digested with several restriction enzymes and subcloned. The resulting plasmids, which had shorter inserts than the original pDAV6 plasmid, were introduced into KAM32 cells; and the transformants were tested for their sensitivity or resistance to DAPI. One of the plasmids, pDAV63, which conferred on KAM32 resistance to DAPI, carried the shortest insert (about 2.2 kbp) and was used for further analysis.

The nucleotide sequence was determined by the dideoxy chain termination method (33) with a DNA sequencer (ALF Express; Pharmacia Biotech.).

Drug susceptibility testing.

The MICs of various drugs were determined in Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco) containing the different drugs at various concentrations (18, 25). The cells were incubated in the test medium at 37°C for 24 h, and the growth was examined by visual inspection.

Efflux assays.

Cells of E. coli KAM32 harboring control or recombinant plasmids were grown in 10 ml of L broth until the optical density at 650 nm reached 0.6 units. After the cells were harvested, they were washed with modified Tanaka buffer (24, 34) and were then resuspended in the same buffer containing 1.0 μM Hoechst 33342 (or 1.0 μM doxorubicin) and 5.0 mM 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) and incubated at 37°C for 10 h. DNP, which is a well-known conductor of protons across the cytoplasmic membrane (3), was used to deenergize the cells. The cells were washed with 0.1 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid-tetramethylammonium hydroxide (pH 7.0) containing 2.0 mM MgSO4 and were then resuspended in the same buffer to obtain an optical density at 650 nm of 0.4 units. The fluorescence of Hoechst 33342 was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 and 457 nm, respectively (37). For the doxorubicin efflux experiment, the excitation wavelength was 467 nm, and the emission was monitored at 590 nm (30). The cell suspension was incubated at 37°C for 5.0 min, and then glucose was added as an energy source to monitor the efflux of the respective drugs.

To study the effects of reserpine and sodium o-vanadate on the efflux of Hoechst 33342, cell suspensions were prepared in the same way as described above. The cell suspensions were preincubated for 5 min at 37°C with different concentrations of reserpine (0 to 40 μM) and sodium o-vanadate (0 to 2 mM) prior to the addition of glucose.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence data bank under accession number AB073220.

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of vcaM gene.

In an attempt to isolate a V. cholerae gene that encodes a multidrug efflux pump, we cloned chromosomal DNA fragments from non-O1 V. cholerae into the pBR322 vector using the shotgun method. We obtained two candidate hybrid plasmids carrying the same insert, and one of the plasmids was denoted pDAV6, which carries a determinant for DAPI resistance. We constructed several deletion plasmids and determined the region where the drug resistance determinant is present. The shortest deletion plasmid that retained the capacity to confer DAPI resistance, pDAV63, was further analyzed. We found one open reading frame in the insert of pDAV63 and named the gene vcaM (V. cholerae ABC multidrug resistance pump) and named its product VcaM. The VcaM protein sequence showed homology with the sequence of a putative ABC protein, VCA0996, suggested from the genome sequence of O1 V. cholerae El Tor (16). The VCA0996 gene is located in chromosome II of the strain. We cloned the gene from non-O1 V. cholerae, which is different from the O1 V. cholerae El Tor N16961 strain used for genome sequencing. In fact, we found that there were some differences (64 nucleotide differences among 1,857 nucleotides at various positions in the gene) in the sequence between the vcrM gene of non-O1 V. cholerae NCTC 4716 and the VCA0996 gene of O1 V. cholerae El Tor N16961. We believe that the product of the VCA0996 gene is an ABC multidrug efflux pump, although it has not yet been characterized. The vcaM gene is preceded by a possible promoter-like sequence and a putative ribosome-binding site (Shine-Dalgarno sequence) starting 9 nucleotides upstream of the ATG initiation codon. The gene was followed by a putative transcription terminator-like (inverted repeat) sequence. The vcaM region was located downstream from the tet promoter of pBR322 in the same direction in pDAV6. There were some transcription terminator-like sequences (inverted repeat) upstream of the putative promoter-like sequence, suggesting that the native promoter of the insert in pDAV6 is functional in E. coli cells. Plasmid pDAV63, from which the transcription terminator-like and the native promoter-like sequences were deleted, was fully functional under the tet promoter of pBR322 to the same extent as pDAV6, judging from the resistance levels (data not shown). The vcaM gene, which is 1,857 bp in length, specifies a putative 619-amino acid protein with a calculated molecular mass of 68.7 kDa. Hydropathy analysis of VcaM suggests the presence of an N-terminal hydrophobic domain with six putative transmembrane segments and a C-terminal hydrophilic domain. The C-terminal domain contains an ABC signature sequence (amino acid residues 496 to 512) and the Walker A motif (residues 396 to 406) and the Walker B motif (residues 516 to 530). The patterns of the transmembrane segments are very similar to those of LmrA and both halves of human P-glycoprotein (data not shown).

The degrees of amino acid sequence identity and similarity between VcaM and VC0996 were 99.2 and 99.7%, respectively. Only 5 amino acid residues at various positions throughout the sequences were found to be different between VcaM and VC0996 (namely, T291I, K346T, Q349P, E355V, and T474H). Comparison of the VcaM sequence with the sequences of members of the ABC protein superfamily revealed the highest overall sequence similarity to members of the subfamily of multidrug resistance P-glycoproteins (e.g., MDR1), LmrA, and HorA. VcaM and each half of human MDR1 share 30% identical residues (48% similarity). Sequence identities between VcaM and the N- and C-terminal halves of human P-glycoprotein were observed throughout their lengths. For instance, the membrane domains of VcaM (residues 1 to 320) and the N- and C-terminal halves of human P-glycoprotein are 16 and 19% identical, respectively (with 55 and 56% similarity, respectively), whereas the ABC domains of the protein are 44 and 39% identical, respectively (with 70 and 77% similarity, respectively) (data not shown). VcaM also has 29 and 26% identity and 53 and 61% similarity with LmrA and HorA, respectively (data not shown).

Role of VcaM in drug resistance.

To investigate the role of VcaM in drug resistance, VcaM was expressed in cells of E. coli KAM32, which is hypersensitive to a number of drugs due to deficiencies in the major multidrug efflux pumps AcrAB and YdhE. The differences in drug susceptibilities between cells harboring pDAV63, which carries vcaM, and cells harboring control plasmid pBR322 were studied in liquid cultures in the presence of 21 drugs that are known substrates for MDR1 and LmrA. The results depicted in Table 1 show that KAM32/pDAV63 showed increased levels of resistance to tetracycline, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, doxorubicin, daunomycin, DAPI, and Hoechst 33342. The cells harboring vcaM were somewhat resistant to ofloxacin, streptomycin, ethidium bromide, tetraphenylphosphonium chloride, rhodamine 6G, and acridine orange. It seemed that other substrates of MDR1, e.g., vinca alkaloids, kanamycin, erythromycin, and chloramphenicol, were not substrates for VcaM.

TABLE 1.

Drug susceptibilities of KAM32/pDAV63 and KAM32/pBR322

| Drug group and drug | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Relative resistancea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KAM32/pBR322 (control) | KAM32/ pDAV63 | ||

| Common drugs for cholera treatment | |||

| Tetracycline | 0.25b | 4.0 | 16 |

| Norfloxacin | 0.015 | 0.125 | 8 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.002 | 0.015 | 8 |

| Ofloxacin | 0.008 | 0.03 | 4 |

| Other antibiotics | |||

| Doxorubicin | 1.0 | 32.0 | 32 |

| Daunomycin | 1.0 | 16.0 | 16 |

| Streptomycin | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2 |

| Kanamycin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Erythromycin | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1 |

| Chloramphenicol | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| Others | |||

| DAPI | 0.12 | 4.0 | 32 |

| Hoechst 33342 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 8 |

| TPPCIc | 4.0 | 16.0 | 4 |

| Rhodamine 6G | 4.0 | 16.0 | 4 |

| Ethidium bromide | 2.0 | 4.0 | 2 |

| Acridine orange | 16 | 32 | 2 |

Relative resistance is the ratio of the MIC for KAM32/pDAV63 to the MIC for KAM32/pBR322.

The value is for KAM32 not harboring pBR322.

TPPCl, tetraphenyl phosphonium chloride.

The MICs for both KAM32/pDAV6 and KAM32/pDAV63 were the same, indicating that only VcaM is necessary and sufficient for resistance. Thus, VcaM is a determinant of multidrug resistance with broad drug specificity.

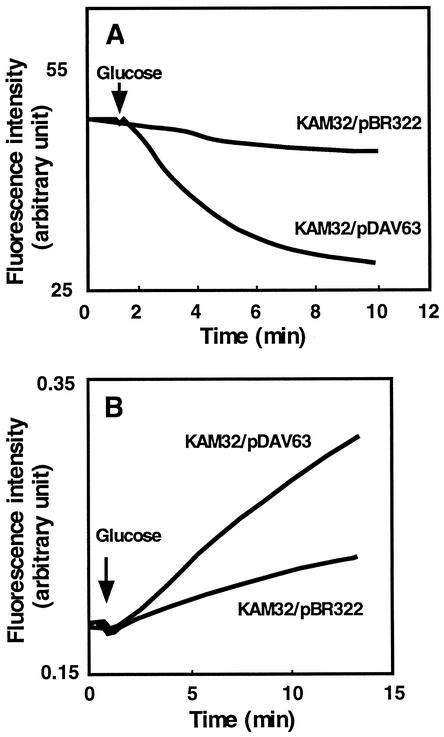

Extrusion of Hoechst 33342 from cells.

Continuous monitoring of fluorescence is an excellent method for the assay of transport, assuming that some fluorescence characteristics of the transported compound (substrate) change when the substrate moves between the intracellular and extracellular milieus (30). The positively charged bisbenzimide Hoechst 33342, 2-[2-(4-ethoxyphenyl)-6-benzimidazolyl]-6-(1-methyl)-4-piperazil)-benzimidazole, has been shown to be actively transported out of cells expressing MDR1 (21). This dye is nonfluorescent in an aqueous environment and becomes strongly fluorescent when it binds to lipid membranes (39) and DNA molecules (21). Therefore, the transport of Hoechst 33342 from the membrane to the aqueous phase can be monitored by detection of a decrease in the level of Hoechst 33342 fluorescence with time. Assays of Hoechst 33342 transport were performed to elucidate the mechanism of VcaM-associated drug resistance. KAM32 cells harboring pDAV63 or pBR322 were deenergized with DNP and loaded with Hoechst 33342. The VcaM-mediated extrusion of Hoechst 33342 from intact cells was measured by monitoring glucose-induced fluorescence dequenching in energy-starved, Hoechst 33342-preloaded cells. Addition of glucose as an energy source caused the rapid extrusion of Hoechst 33342 from KAM32/pDAV63 cells but not from KAM32/pBR322 cells (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Efflux of Hoechst 33342 (A) and doxorubicin (B) from E. coli KAM32 cells with or without VcaM. Energy-starved KAM32/pDAV63 cells or KAM32/pBR322 cells (control) were loaded either with 1 μM Hoechst 33342 (A) or with 10 μM doxorubicin (B). At the time point indicated by the arrow, glucose (final concentration, 20 mM) was added to energize the cells. The fluorescence of Hoechst 33342 or doxorubicin was monitored with a fluorescence spectrophotometer at 37°C over time. In panel A, the downward deflection indicates the efflux of Hoechst 33342 from the cell to the aqueous medium. In panel B, the upward deflection indicates the efflux of doxorubicin from the cell to the aqueous medium.

Extrusion of doxorubicin from cells.

One of the very important characteristics of the multidrug efflux pump is that it extrudes structurally unrelated compounds. In order to support the notion that the multidrug resistance induced by VcaM is based on the energy-dependent efflux of multiple drugs, we also measured the efflux of doxorubicin. The efflux of doxorubicin from deenergized and doxorubicin-preloaded cells was observed after the addition of glucose as an energy source (Fig. 1B). Since the fluorescence quantum yield for extracellular doxorubicin is 6.5 times greater than that for intracellular drug, the time-dependent increase in total fluorescence is due to the appearance of extracellular drug. Therefore, the rate of change in the total fluorescence of doxorubicin represents the rate of efflux of the drug from cells. These results, together with the drug susceptibility assay results (described above), identify VcaM as an efficient and excellent cell detoxification system.

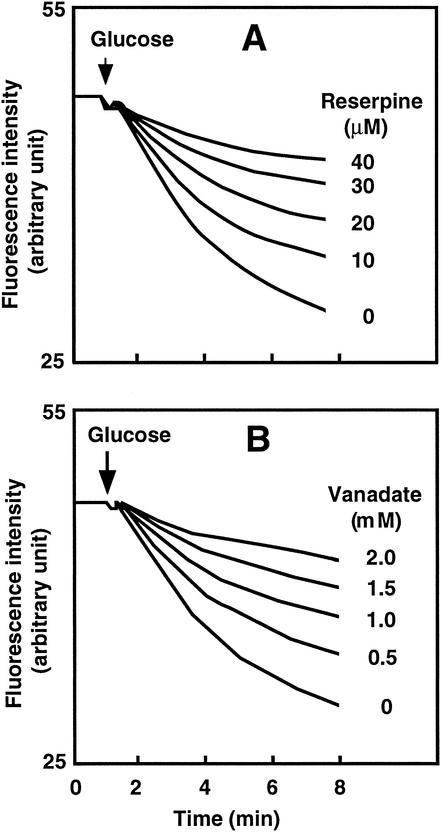

Inhibition of Hoechst 33342 extrusion.

Reserpine is known to be a potent inhibitor of MDR1 (9). We investigated the effect of reserpine on the efflux of Hoechst 33342 from KAM32/pDAV63 cells. Cells were preincubated with different concentrations of reserpine prior to the addition of glucose as an energy source. Reserpine inhibited the extrusion of Hoechst 33342 in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Strong inhibition was observed with 40 μM reserpine. The concentration of reserpine causing 50% inhibition was about 20 μM.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of VcaM-mediated efflux of Hoechst 33342 by reserpine (A) or vanadate (B). Energy-starved KAM32/pDAV63 cells loaded with Hoechst 33342 were prepared as described in the legend to Fig. 1. (A) Reserpine was added at concentrations ranging from 0 to 40 μM before the addition of glucose (final concentration, 20 mM). (B) Sodium-o-vanadate was added at concentrations ranging from 0 to 2.0 mM before the addition of glucose.

VcaM is a member of the ABC multidrug efflux pump family. Sodium o-vanadate is a well-known ATPase inhibitor and specifically inhibits the activities of LmrA, HorA, and MDR1, members of the ABC family (9, 32, 39). We tested whether extrusion of Hoechst 33342 was inhibited by sodium o-vanadate. Cells were preincubated with or without sodium o-vanadate (0 to 2 mM). Again, concentration-dependent inhibition of Hoechst 33342 extrusion was observed (Fig. 2B). At 2 mM, sodium o-vanadate strongly inhibited efflux.

DISCUSSION

In gram-positive bacteria, two ABC multidrug transporters, LmrA and HorA, have been characterized thus far. There have been a number of reports on ABC transporters in gram-positive bacteria that mediate extrusion of a specific antibiotic (2, 15, 28, 31). Recently, a macrolide-specific ABC transporter, MacAB, has been reported in E. coli (20). To our knowledge, VcaM of non-O1 V. cholerae, which detoxifies multiple drugs with different chemical structures and mechanisms of action and which has been described in this paper, represents the first ABC multidrug efflux pump in gram-negative bacteria.

A search with the BLAST program revealed that the sequence of VcaM shares significant identity with the sequences of putative ABC transporters of a number of gram-negative bacteria, such as Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and also with gram-positive bacteria, e.g., Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis. The VcaM sequence is also similar to those of the ABC transporters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila melanogaster. Therefore, the VcaM homologues or similar pumps are present in a number of organisms, and this type of multidrug efflux pump is conserved from bacteria to mammals. However, the VcaM sequence showed no significant similarity with those of five putative ABC multidrug transporters from the genome of E. coli (26). There are at least 23 multidrug efflux pump genes in the O1 V. cholerae genome sequence, and only 2 (MsbA homolog and VcaM) are of the ABC type.

An important feature of this study is that VcaM made an E. coli strain highly resistant to tetracycline, norfloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. Tetracycline and fluoroquinolones, e.g., norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin, are commonly used in the treatment of cholera patients in order to reduce the vibrio counts in the stool and to decrease fluid loss. We do not yet have evidence of whether VcaM is expressed in any other V. cholerae strain under natural conditions. As we found that chromosome II of an O1 V. cholerae strain also possesses a gene (VCA0996) almost identical to vcaM (16), the possibility of its expression or overexpression cannot be ruled out. If this were to occur, it would be a serious threat to the treatment of cholera, especially in patients with severe cases.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Varela of Eastern New Mexico University for critical reading of the manuscript.

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sport and Culture of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, A., and J. L. Martinez. 2001. Expression of multidrug efflux pump SmeDEF by clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1879-1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrasa, M. I., J. A. Tercero, R. A. Lacalle, and A. Jimene. 1995. The ard1 gene from Streptomyces capreolus encodes a polypeptide of the ABC transporters superfamily which confers resistance to the aminonucleoside antibiotic A201A. Eur. J. Biochem. 228:562-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger, E. A. 1973. Different mechanisms of energy coupling for the active transport of proline and glutamine in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 70:1514-1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger-Bachi, B. 2002. Resistance mechanisms of gram-positive bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berns, K. I., and C. A. J. Thomas. 1965. Isolation of high molecular weight DNA from Haemophilus influenzae. J. Mol. Biol. 11:117-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhury, P., and R. Kumar. 1996. Association of metal tolerance with multiple antibiotic resistance of enteropathogenic organisms isolated from coastal region of delta Sunderbans. Indian J. Med. Res. 104:148-151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colmer, J. A., J. A. Fralick, and A. N. Hamood. 1998. Isolation and characterization of a putative multidrug resistance pump from Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 27:63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalsdaard, A., A. Forslund, L. Bodhidatta, O. Serichantalergs, C. Pitarangsi, L. Pang, T. Shimada, and P. Echeverria. 1999. A high proportion of Vibrio cholerae strains isolated from children with diarrhoea in Bangkok, Thailand are multiple antibiotic resistant and belong to heterogenous non-O1, non-O139 O-serotypes. Epidemiol. Infect. 122:217-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Endicott, J. A., and V. Ling. 1989. The biochemistry of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 58:137-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falbo, V., A. Carattoli, F. Tosin, C. Pezzella, A. M. Dionisi, and I. Luzzi. 1999. Antibiotic resistance conferred by a conjugative plasmid and a class I integron in V. cholerae O1 E1 Tor strains isolated in Albania and Italy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:693-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faruque, S. M., M. J. Albert, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Epidemiology, genetics, and ecology of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1301-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garg, P., S. Chakraborty, I. Basu, S. Datta, K. Rajendran, T. Bhattacharya, S. Yamasaki, S. K. Bhattacharya, Y. Takeda, G. B. Nair, and T. Ramamuthy. 2000. Expanding multiple antibiotic resistance among clinical strains of Vibrio cholerae isolated from 1992-7 in Calcutta, India. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:393-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg, P., S. Sinha, R. Chakraborty, S. K. Bhattacharya, G. B. Nair, and T. Ramamuthy. 2001. Emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor among hospitalized patients with cholera in Calcutta, India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1605-1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glass, R. I., I. Huq, A. R. M. A. Alim, and M. Yunus. 1980. Emergence of multiply antibiotic resistance Vibrio cholerae in Bangladesh. J. Infect. Dis. 142:939-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guilfoile, P. G., and G. Hutchinson. 1991. A bacterial analog of the mdr gene of mammalian tumor cells is present in Streptomyces peucetius, the producer of daunorubicin and doxorubicin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8553-8557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heidelberg, J. F., A. J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, R. R. Colwell, J. J. Mekalanos, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huda, M. N., J. Chen, Y. Morita, T. Kuroda, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 2003. Gene cloning and characterization of VcrM, a Na+-coupled multidrug efflux pump, from Vibrio cholerae non-O1. Microbiol. Immunol. 47:419-427. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Huda, M. N., Y. Morita, T. Kuroda, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 2001. Na+-driven multidrug efflux pump VcmA from Vibrio cholerae non-O1, a non-halophilic bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203:235-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, P. M., and A. M. George. 1998. A new structural model for P-glycoprotein. J. Membr. Biol. 166:133-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi, N., K. Nishino, and A. Yamaguchi. 2001. Novel macrolide-specific ABC-type efflux transporter in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:5639-5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lalande, M. E., V. Ling, and R. E. Miller. 1981. Hoechst 33342 dye uptake as a probe of membrane permeability changes in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 78:363-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lennox, E. S. 1955. Transduction of linked genetic characters of host by bacteriophage P1. Virology 1:190-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, p. 68. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Morita, Y., A. Kataoka, S. Shiota, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 2000. NorM of Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a Na+-driven multidrug efflux pump. J. Bacteriol. 182:6694-6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morita, Y., K. Kodama, S. Shiota, T. Mine, A. Kataoka, T. Mizushima, and T. Tsuchiya. 1998. NorM, a putative multidrug efflux protein, of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and its homolog in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1778-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulsen, I. T., M. K. Sliwinski, and M. Saier, Jr. 1998. Microbial genome analyses: global comparison of transport capabilities based on phylogenies, bioenergetics and substrate specificities. J. Mol. Biol. 277:573-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piddock, L. J., M. M. Johnson, S. Simjee, and L. Pumbwe. 2002. Expression of efflux pump gene pmrA in fluoroquinolone-resistant and -susceptible clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:808-812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podlesek, Z., A. Comino, B. Herzog-Velikonja, D. Zgur-Bertok, R. Komel, and M. Grabnar. 1995. Bacillus licheniformis bacitracin-resistance ABC transporter: relationship to mammalian multidrug resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 16:969-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poole, K. 2003. Overcoming multidrug resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 4:128-139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roepe, P. D. 1992. Analysis of the steady-state and initial rate of doxorubicin efflux from a series of multidrug-resistant cells expressing different levels of P-glycoprotein. Biochemistry 31:12555-12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross, J. I., E. A. Ead, J. H. Cove, W. J. Cunliffe, S. Baumberg, and J. C. Wootton. 1990. Inducible erythromycin resistance in staphylococci is encoded by a member of the ATP-binding transport super-gene family. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1207-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakamoto, K., A. Margolles, H. W. van Veen, and W. N. Konings. 2001. Hop resistance in the beer spoilage bacterium Lactobacillus brevis is mediated by the ATP-binding cassette multidrug transporter HorA. J. Bacteriol. 183:5371-5375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka, S., S. A. Lerner, and E. C. C. Lin. 1976. Replacement of a phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent phoshotransferase by a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-linked dehydrogenase for the utilization of mannitol. J. Bacteriol. 93:642-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas, H., and H. M. Coley. 2003. Overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer: an update on the clinical strategy of inhibiting P-glycoprotein. Cancer Control 10:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Threlfall, E. J., B. Rowe, and I. Huq. 1980. Plasmid-encoded multiple antibiotic resistance in Vibrio cholerae El Tor from Bangladesh. Lancet i:1247-1248. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.van Veen, H. W., A. Margolles, M. Muller, C. F. Higgins, and W. N. Konings. 2000. The homodimeric ATP-binding cassette transporter LmrA mediates multidrug transport by an alternating two-site (two-cylinder engine) mechanism. EMBO J. 19:2503-2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Veen, H. W., M. Putman, W. van Klompenburg, R. Heijne, A. Margolles, and W. N. Konings. 1998. Basic mechanisms of antibiotic resistance: molecular properties of multidrug transporters. McGill J. Med. 4:56-66. [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Veen, H. W., R. Callaghan, L. Soceneantu, A. Sardini, W. N. Konings, and C. F. Higgins. 1998. A bacterial antibiotic-resistance gene that complements the human multidrug-resistance P-glycoprotein. Nature 391:291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. 2001. Antimicrobial resistance in shigellosis, cholera, and campylobacteriosis. Report WHO/CDS/CSR/DRS/2001.8. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 41.Young, J., and I. B. Holland. 1999. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters-revisited five years on. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1461:177-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zgurskaya, H. I. 2002. Molecular analysis of efflux pump-based antibiotic resistance. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, L., X. Z. Li, and K. Poole. 2001. SmeDEF multidrug efflux pump contributes to intrinsic multidrug resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3497-3503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]