Abstract

Background

Disrupting neural migration with bilateral focal freezing necrosis on postnatal day 1 (P1) results in the formation of 4-layered microgyria. This developmental injury triggers a pervasive neural reorganization, which is evident at the electrophysiological, behavioral, and anatomical levels. In this experiment, we investigated changes in brain weight as an index of global disruption of neural systems caused by focal damage to the developing cortical plate.

Results

We found a dramatic reduction in overall brain weight in microgyric subjects. This reduction in brain weight among animals with microgyria is reflected in decreased total brain volume, with a disproportionate decrease in neocortical volume. This effect is so robust that it is seen across varied environments, at variable ages, and across the sexes.

Conclusions

This finding supports previous work suggesting that substantial reorganization of the brain is triggered by the induction of bilateral freezing damage. These results have critical implications for the profound re-organizational effects of relatively small focal injuries early in development to distributed systems throughout the brain, and particularly in the cerebral cortex.

Background

Focal damage to the developing brain can have widespread consequences for structures and regions that project to or receive direct or even indirect projections from the damaged area [1-3]. Focal neocortical malformations induced by freeze injury to the developing cortical plate exemplify this fact. It has been shown that these malformations, resembling human microgyria, are associated with widespread disturbances in neuronal organization[4,5]. For example, brain slices containing microgyric cortex show increased epileptogenic activity [6-9]. Microgyric anomalies are also associated with connectional alterations [10-12], affecting both thalamic and cortico-cortical connectivity. In addition, changes in neuronal cell size distribution in the medial geniculate nuclei associated with the presence of neocortical malformations, have been demonstrated in both human dyslexic brains[13] and rat brains [14-16].

Along with these structural alterations, damage to the developing brain produces functional changes[1], suggesting that structural changes are not necessarily maladaptive in all cases. For example, the presence of neocortical malformations in certain strains of inbred mice are correlated with better performance on tasks of spatial reference memory[17,18]. On the other hand, induced microgyric animals show a variety of behavioral deficits that suggest disturbances to multiple brain systems [15,19-22]. Rapid auditory processing deficits have been found in males with induced microgyria using both an operant condition paradigm and a reflex modification paradigm [15,19-21]. In both paradigms, auditory processing deficits were found only on rapidly changing stimuli, and not when these same stimuli were delivered at slower rates. Further, animals with induced microgyria showed poorer performance in discrimination learning and took longer paths to the target in the Morris Water Maze than sham littermates[22].

The extent of brain-wide changes induced by the relatively restricted freezing lesion that produces microgyria is, however, unknown. Here we present evidence that induced bilateral focal microgyria leads to significant reductions in overall brain weight that are quite robust, being seen at all ages measured (P30 – P118), in both males and females, and are unaffected by acoustic rearing experiences. Moreover, volumetric analysis suggests this reduction largely reflects a disproportionate decrease of neocortical tissue.

Results

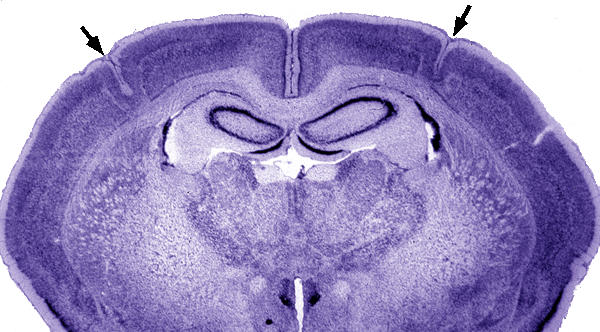

Histological analysis confirmed the presence of bilateral microgyria in all subjects exposed to the P1 freezing lesion treatment (Figure 1). Malformations were located in somatosensory-related cortex (SM-I) including regions Par1, Par2, HL, and FL[23]. No malformations were seen in any sham subject.

Figure 1.

Low power photomicrograph of a Wistar rat brain with bilateral microgyria (arrows). Note the normal-appearing cortex medial and lateral to the microgyria. Bar = 800 μm.

The present experiment was comprised of three studies (see Methods for complete details). Study 1 examined the effect of rearing in three different acoustic Environments (enriched, deprived, and control). The effect of Age (P30, P52, P83) was investigated in Study 2, while the effect of Sex was assessed in Study 3.

Body Weight Analysis

Differences in body weight within each study were examined by analysis of variance (ANOVA; see Table 1). In Study 1, there was a significant effect of rearing condition (F2,34 = 18.1, P < .001), with animals in the enriched condition having significantly smaller body weights than subjects in either of the other two groups. There were no other significant main effects or interactions. For Study 2, there was the expected highly significant effect of Age (F2,50 = 508.6, P < .001), but no other significant effects. There was also an expected effect of Sex in Study 3, with females weighing significantly less than males (F1,36 = 685.2, P < .001); there were no other significant effects. Due to the significant main effects of body weight in these studies, we regressed out the effects of body weight on all subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Mean (± SEM) Body Weights for All Studies

| Study | Surgical Group | ||

| Study 1 | Environment | Microgyria | Sham |

| White Noise | 506.8 ± 22.4 | 459.9 ± 25.4 | |

| Control | 449.4 ± 10.6 | 462.1 ± 8.3 | |

| Enriched | 408.9 ± 14.1 | 364.0 ± 9.3 | |

| Study 2 | Age | ||

| P30 | 97.1 ± 4.7 | 98.2 ± 3.7 | |

| P52 | 230.6 ± 8.2 | 233.0 ± 11.9 | |

| P83 | 381.0 ± 10.4 | 382.5 ± 9.5 | |

| Study 3 | Sex | ||

| Male | 443.8 ± 9.7 | 459.3 ± 7.3 | |

| Female | 238.4 ± 8.1 | 254.5 ± 5.6 | |

Brain Weight Analyses

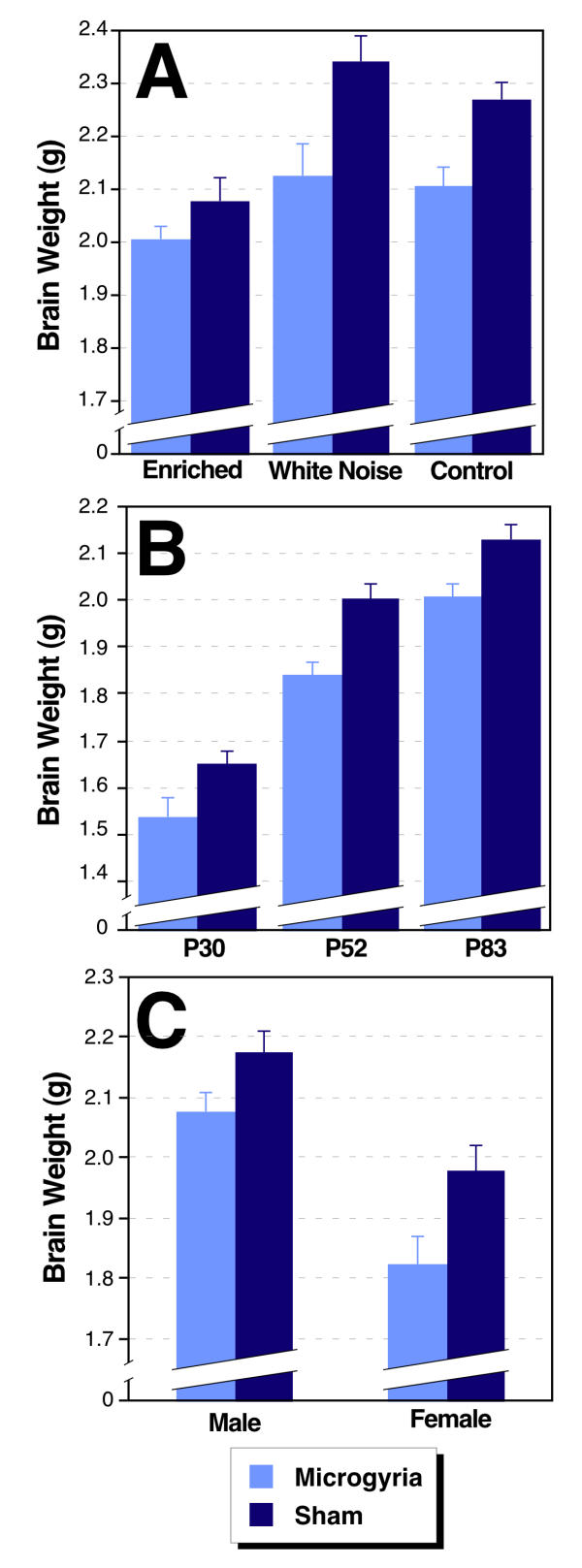

Brain weight measures were regressed against body weight, and the residuals were used as the dependent measure in an ANOVA (see Table 2). Study 1 showed a highly significant effect of Lesion (F 1,34 = 30.83; p < 0.001), reflecting a decreased brain weight in microgyric subjects compared to shams across environments (Figure 2A). There was no interaction with Environment (F 2,34 < 1), nor main effect of Environment (F 2,34 = 1.50; ns). Study 2 also showed a highly significant effect of Lesion (F 1,50 = 48.43; p < 0.001), with the presence of microgyric lesion associated with decreased brain weight (Figure 2B). There was no main effect of Age (F 2,50 = 1.03; NS; the effects of body size differences having been regressed out) nor was there a significant interaction between main effects (F 2,50 < 1). In Study 3, Lesion once again had a significant effect on brain weight (F 1,36 = 8.86; p < 0.01), with microgyric lesions associated with decreased overall brain weight (Figure 2C). There was no Lesion × Sex interaction (F 2,36 < 1), nor main effect of Sex (F 1,36 <1).

Table 2.

Mean (± SEM) Residual Brain Weight Scores Regressed Against Body Weight for All Studies

| Study | Surgical Group | ||

| Study 1 | Environment | Microgyria | Sham |

| White Noise | -0.097 ± 0.035 | 0.079 ± 0.039 | |

| Control | -0.044 ± 0.038 | 0.105 ± 0.028 | |

| Enriched | -0.092 ± 0.027 | 0.040 ± 0.033 | |

| Study 2 | Age | ||

| P30 | -0.070 ± 0.025 | 0.041 + 0.026 | |

| P52 | -0.068 ± 0.018 | 0.093 ± 0.015 | |

| P83 | -0.079 ± 0.023 | 0.044 ± 0.026 | |

| Study 3 | Sex | ||

| Male | -0.050 ± 0.031 | 0.030 ± 0.034 | |

| Female | -0.058 ± 0.038 | 0.077 ± 0.041 | |

Figure 2.

Brain weights (in g) from three separate studies. A. Study 1: Microgyric brains weigh less than shams at all environmental conditions (P < .001). There is no effect of Environment when body weight is regressed out. B. Study 2: Animals with microgyria have smaller brain weights than shams at all three ages tested (P < .001). There is no effect of Age on brain weight when body weight is regressed out. C. Study 3: Microgyric brain weight is less than shams for both males and females (P < .001). There is no effect of Sex on brain weight when body weight is regressed out.

Brain Volume Analyses

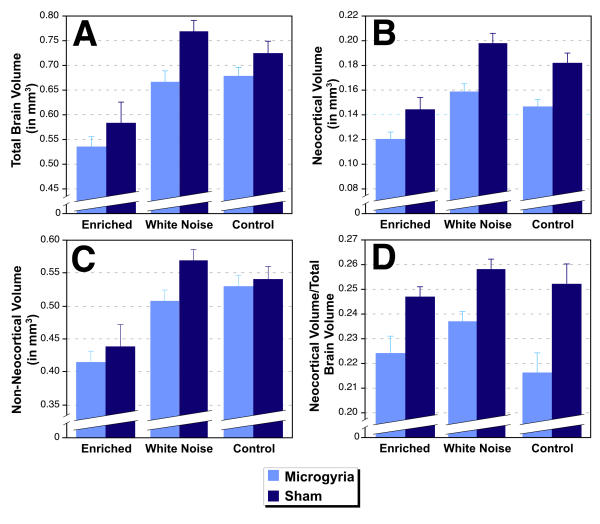

In an attempt to localize the effects of microgyric lesions on brain weight, we assessed total brain area, neocortical area, and microgyric lesion area, and estimated volume in a randomly selected subset of subjects from Study 1 (Control N = 7 microgyric, 6 sham; Deprived N = 6 microgyric, 6 sham; Enriched N = 6 microgyric, 5 sham). Volume measures were linearly regressed against body weight, and the residuals were used as the dependent measure (see Table 3). For microgyric volume, only lesioned subjects were included in the regression. An initial ANOVA, using residuals of microgyria volume as the dependent measure and Environment as the independent measure, showed no difference among the different environmental conditions (F2,16 = 1.51, NS). This demonstrates an equivalent microgyria size in all environmental groups. An ANOVA on total brain volume revealed a significant effect of Lesion (F1,31= 18.11, p < .001) and Environment (F1,31= 6.35, p = 0.01), but no interaction (F2,31= 2.33, NS). As can be seen in Figure 3A, microgyric animals had smaller brain volumes than their sham counterparts across all conditions. Among the three environmental groups, those from the acoustically Enriched group had smaller residuals than the other two groups.

Table 3.

Mean (± SEM) Residual Volume Scores Regressed Against Body Weight.

| Volume Measure | Surgical Group | Environment Condition | ||

| White Noise | Control | Enriched | ||

| Total Brain | Microgyria | -51.44 ± 11.26 | 7.92 ± 12.36 | -94.55 ± 21.32 |

| Sham | 89.35 ± 34.37 | 45.73 ± 23.36 | -15.74 ± 35.59 | |

| Neocortex | Microgyria | -13.38 ± 3.68 | -14.09 ± 5.28 | -31.16 ± 5.46 |

| Sham | 35.53 ± 10.64 | 19.51 ± 8.28 | 0.01 ± 8.41 | |

| Non Neocortex | Microgyria | -38.06 ± 8.83 | 22.01 ± 12.72 | -63.50 ± 17.59 |

| Sham | 53.82 ± 24.03 | 26.22 ± 18.01 | -15.75 ± 27.60 | |

| Cortex: Total Brain | Microgyria | -0.00 ± 0.004 | -0.02 ± 0.008 | -0.01 ± 0.007 |

| Sham | 0.02 ± 0.004 | 0.01 ± 0.008 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | |

| Microgyria | -0.35 ± 1.90 | 1.79 ± 1.31 | -1.75 ± 1.15 | |

Figure 3.

Regional volumes as determined from stereology of histologic sections. A. Total brain volume is smaller in animals with microgyria than in shams (P < .001). This is true across all environmental conditions. B. Microgyric subjects have smaller neocortical volumes than do shams at all environmental conditions (P < .001). C. The volume of non-neocortical regions is smaller in microgyric as compared to sham subjects (P < .01). This is true across all environmental conditions. D. The ratio of neocortical to total brain volume is smaller in microgyric subjects, indicating that neocortex is disproportionately smaller in subjects with microgyria (P < .001).

An ANOVA using the residuals of neocortical volume as the dependent measure were similar to those of brain volume (Figure 3B). Microgyric subjects had smaller neocortical volumes than shams (F1,31 = 38.00, p < 0.001), irrespective of environmental condition. Environmental effects remained significant (F2,31 = 6.27, p< 0.01), with those subjects in the acoustically Enriched group having smaller neocortical volume residuals than those in the other conditions. There was no interaction between Lesion and Environment (F2,31 < 1, NS).

An ANOVA was performed for non-neocortical volume (computed by total brain volume minus neocortical volume), to assess whether Lesion effects and Environmental effects were specific to cortex, or distributed through non-neocortical areas as well. Analysis showed a main effect of Lesion (F1,31 = 9.62, p < 0.01), and Environment (F2,31 = 5.83, p < 0.01), with no interaction (F2,31 = 2.85, p > 0.05; see Figure 3C). However, relative F values suggested that while Environment main effects were equivalent between cortex and non-cortex, Lesion effects were more pronounced in the neocortex.

To directly assess the issue of a disproportionate loss of neocortical volume in Lesion subjects, we computed the ratio of neocortical to total brain volume, regressed those values against body weight, and analyzed the residuals. An ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Lesion (F1,31 = 25.66, p < 0.001) but not Environment (F2,31 = 2.97, p > 0.05), and no interaction between the two (F2,31 < 1, NS). Thus, microgyric subjects had disproportionately smaller cortices than their sham counterparts (Figure 3D). Environment, conversely, affected the whole brain and had no significant effects on this ratio measure. It is important to note that the enrichment procedure of this study differed significantly from those used previously[24] in that it began prenatally. Future research will be needed to determine what possible effects this additional variable had on subjects' body weight and brain volume.

Discussion

The current findings show that early focal brain injuries, specifically P1 focal freezing necrosis producing microgyria, lead to reductions in brain weight that are so robust that the main effect of Lesion does not interact with Environment, Age, or Sex. Analysis of histologic brain and neocortical volume confirmed the effects of lesion on brain weight, and suggest that the reduction in volume associated with microgyria is proportionally greater in the cerebral cortex. This finding supports previous work suggesting that substantial reorganization of the brain is triggered by the induction of bilateral freezing damage. Surprisingly, this reorganization was not differentially affected across ages, by an enriched environment, nor by the difference in brain weight between the sexes (e.g.,.Refs. [27,28]). Further, reorganization (i.e., brain weight and volume reduction due to microgyria) was evident by P30 and remained consistent into adulthood.

Since reductions in brain weight and total brain volume in Microgyric (Lesion) subjects reflect disproportionate loss of neocortical tissue, it is important to address the unlikely possibility that this effect reflects direct tissue loss from lesion induction. This is unlikely because no tissue was removed. Further, though microgyric neocortical tissue showed anomalous organization, there was no demonstrable tissue reduction localized to the malformation itself (see Figure 1).

Unlike Lesion effects, the reduction in brain volume seen in subjects raised in an acoustically Enriched environment was evident throughout neocortical and non-neocortical regions, with no disproportionate effects in cortex. It is possible that this reduction reflects the smaller body size of enriched animals (who were highly active), and which may not have been fully accounted for in the residual measure due to a low n and accordingly low correlation. Further research will be needed to reconcile this smaller brain size with reports of increased brain weight in enriched subjects [24-26]. It is important to note that the environmental enrichment methods employed in this study are fundamentally different from those used in other studies; for example, our auditory environment differences began prenatally and extended until adulthood.

Finally, Kolb and Cioe[29] also found a reduction in brain weight following aspiration lesions of frontal cortex performed on P2. Although aspiration differs from freezing injury, both techniques were applied within the period of neural migration, and have demonstrated little effect of specific location of the lesion on a variety of measures (e.g., behavior, brain weight, thalamic morphology[14,30]). These factors indicate that subsequent systematic alterations (e.g., in function) may reflect a developmental cascade leading to distal changes, rather than stemming from the focal injury per se.

Conclusions

An animal model of microgyric neuromigrational anomalies has been employed to demonstrate a reduced brain weight in microgyric subjects that is consistent across variable ages, environments, and sex. Importantly, this effect appears to reflect a disproportionate reduction of neocortical volume. Since differences in brain weight have been shown to be proportional to total brain DNA content and thus total CNS cell number[31,32], and since brain weight has been suggested to be a good surrogate measure for total cell number in mice (as in humans [28]), we hypothesize that total cell number – particularly in cortex – may be decreased in microgyric subjects.

Alternatively, the decrease in brain weight could reflect changes in neuropil rather than cell numbers. It is important to note that the highly significant Microgyria effects on whole brain, and particularly cerebral cortex, are seen despite a lack of body weight differences between Sham and Lesion groups. Environment effects, conversely, may be accounted for at least partly by significant body weight differences (due to activity differences) that may not fully have been accounted for in residual scores (due to relatively small subject numbers). Collective results have critical implications for the profound re-organizational effects of relatively small focal injuries early in development, specifically to affect distributed systems throughout the brain and in particular the cerebral cortex. Future research will explore these issues.

Methods

Wistar rats (N = 96) from three separate study groups born at the University of Connecticut to purchased dams from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were used. All groups received induced focal microgyric lesions on P1 using identical methods (see below), and took part in a battery of auditory perception testing (data not shown). All procedures were approved by the University of Connecticut's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, with adequate measures to minimize pain or discomfort to the animals.

Induction of Microgyric Lesions

On P1 (day of birth = P0), litters were culled to 10 rat pups for focal microgyria induction. Pups were randomly designated to receive bilateral freezing lesions or sham surgery, balancing treatment within litters. Focal microgyric lesions were induced using a modification of the technique employed by Dvorák and associates[33,34]; and explained in detail elsewhere[5]. Briefly, pups assigned to the lesion condition received hypothermia induced anesthesia followed by a small midline incision over the skull. A cooled (-70°C) 2-mm diameter stainless steel probe was placed on the skull approximately 2 mm lateral of the sagittal suture overlying bregma for 5 sec. Following the initial lesion, an identical lesion was placed in the opposite hemisphere (first lesion side randomly determined) using a second cooled probe. Sham subjects had identical treatment, except the steel probe was maintained at room temperature. Following treatment, the skin was sutured, and subjects were marked with ink footpad injections, warmed, and returned to the dam.

Study Groups

A summary of the three study groups is presented in Table 4. Study 1 assessed environmental variations on the effects of the P1 induced microgyria in male subjects. Litters were raised from embryonic day 7 (E7) to adulthood (P70) in one of three environmental conditions. A Control group was reared in the normal housing area (background room noise = 45–55 dB), and was pair-housed by treatment at weaning (P21). A White Noise group was reared in a separate room with 24 h. exposure to a broad band white noise (80 dB), and was pair-housed by treatment at weaning. An Enriched group was reared in a separate room with 3 h of non-vocal, light classical music exposure (75–78 dB) daily as the dark period began, and was group housed (n = 19) at weaning in an enriched housing condition. Brain analysis (see below) occurred on P118 (see [15] for further study details). Study 2 assessed the effects of P1 induced microgyria in male rats across three stages of development. To accommodate auditory testing, pups were weaned on P24 and pairhoused by treatment in the normal housing area. Brain analysis (see below) occurred on P30, P52, and P83. Study 3 assessed the effects of P1 induced microgyria in males and females. At weaning (P21), pups were pair-housed by sex and treatment in the normal housing area. Brain analysis (see below) occurred on P110.

Table 4.

Study Group Composition

| Study 1: Environment | Study 2: Development | Study 3: Sex | |

| Age at Time of Brain Analysis | P118 | P30 (N = 7L/11s) P52 (N = 8L/10S) P83 (N = 10L/10S) | P110 |

| Environment | Standard Housing (N = 7L/7S) White Noise (N = 6L/7S) Enriched (N = 7L/6S) | Standard Housing | Standard Housing |

| Subject Sex | Male | Male | Male (N = 10L/10S) Female (N = 10L/10S) |

A summary of the three Study Groups used to evaluate effects of induced P1 bilateral microgyria on brain weight. Note: P = Postnatal Day (P0 = birth), L = Microgyric Lesion Subject, S = Sham Subject

Brain Weight Analysis

Subjects were weighed, anesthetized and transcardially perfused (0.9% saline, 10% Phosphate Buffered Formalin). Heads were removed, placed in formalin, and shipped to GDR for anatomical analysis. Brains were removed (spinal cord removed at the caudal extent of the cerebellum) and weighed. The brains were then embedded in celloidin as described previously[14,15,35], sliced at 30 μm, and every tenth section stained with cresyl violet and mounted onto glass slides. Microgyric lesions were confirmed and location assessed.

Separate ANOVA's were performed on brain weight residuals for each study group after regressing against body weight (see Tables 1 and 2), using either a linear regression (Studies 1 and 3), or a logarithmic regression (Study 2). The logarithmic regression for Study 2 compensated for the confound between brain weight and age in this study. Each study's specific treatment groups served as Between Subject variables – Study 1: Environment (3 levels: Enriched, White Noise, and Control), Lesion (2: Microgyric Lesion and Sham); Study 2: Age (3: P30, P52, and P83), Lesion (2: Microgyric Lesion and Sham); Study 3: Sex (2: Male and Female), Lesion (2: Microgyric Lesion and Sham).

Brain Volume Analysis

Volumes were estimated using Stereo Investigator (Microbrightfield Corp., USA) interfaced to a Nikon E800 microscope (Nikon Instruments, USA) fitted with a Prior motorized stage (Prior Scientific, USA). The areas of systematic series of sections through the entire region of interest were measured using point counting, and the volumes estimated using Cavalieri's rule. In cases where there were missing sections, volumes were estimated using a parabolic approach[36]. Measures of total brain volume included the entire brain from olfactory bulb to cerebellum. Cerebral cortex was measured from the first section on which it appeared through its caudal extent, with the lateral boundary defined by entorhinal cortex. For estimates of total brain and cerebral cortical volume, we measured every 40th section using a 1 mm2 point counting grid (13–18 sections for total brain volume, 7–13 sections for cerebral cortex). Microgyric volume was measured on every 20th section using a 300 μm2 grid (6–10 sections/subject). The coefficient of error for these measures ranged from 0.01 to 0.10, with means of 0.02 ± 0.004 for brain volume, 0.05 ± 0.011 for neocortical volume, and 0.06 ± 0.02 for microgyria volume.

List of Abbreviations

P - Postnatal Day

E - Embryonic Day

SM-I - Somatosensory-related cortex

Par1 - Primary somatosensory cortex

Par2 - Secondary somatosensory cortex

HL - Hindlimb area of somatosensory cortex

FL - Forelimb area of somatosensory cortex

ANOVA - Analysis of variance

Authors' contributions

AMP participated in the design of the study, performed the auditory testing and perfusions for Studies 1 and 3, performed the initial data analysis and drafted the manuscript. RHF supervised all aspects of the study and participated in all aspects of its design, coordination, and drafting. JJT performed the auditory testing and perfusions of Study 2. ANY performed the anatomic measures and collaborated on the statistical analysis. GDR performed the freezing lesions, supervised the anatomic measures, supervised the final data analysis, and participated in the drafting of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Research was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health, grant HD20806. The authors would like to thank Dr. Victor Denenberg for statistical advice and discussion and Stefany Palmieri, Phyllis Itoka, and Sidhardha Kamaraju for technical assistance.

Contributor Information

Ann M Peiffer, Email: ann.peiffer@uconn.edu.

R Holly Fitch, Email: roslyn.h.fitch@uconn.edu.

Jennifer J Thomas, Email: thomas@axon.rutgers.edu.

Alexandra N Yurkovic, Email: yurkovic@fas.harvard.edu.

Glenn D Rosen, Email: grosen@bidmc.harvard.edu.

References

- Goldman PS, Galkin TW. Prenatal removal of frontal association cortex in the fetal rhesus monkey: anatomical and functional consequences in postnatal life. Brain Res. 1978;152:451–485. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B, Windrem MS, Finlay BL. Thalamic ablations and neocortical development: alterations in thalamic and callosal connectivity. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1:241–61. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider GE. Early lesions and abnormal neuronal connections. Trends Neurosci. 1981;4:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda AM, Sherman GF, Rosen GD, Aboitiz F, Geschwind N. Developmental dyslexia: four consecutive patients with cortical anomalies. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:222–33. doi: 10.1002/ana.410180210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys P, Rosen GD, Press DM, Sherman GF, Galaburda AM. Freezing lesions of the developing rat brain: a model for cerebrocortical microgyria. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1991;50:145–60. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs KM, Gutnick MJ, Prince DA. Hyperexcitability in a model of cortical maldevelopment. Cereb Cortex. 1996;6:514–23. doi: 10.1093/cercor/6.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs KM, Hwang BJ, Prince DA. Focal epileptogenesis in a rat model of polymicrogyria. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:159–73. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann HJ, Raabe K. Characterization of neuronal migration disorders in neocortical structures: I. Expression of epileptiform activity in an animal model. Epilepsy Res. 1996;26:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(96)00041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann HJ, Raabe K, Qu M, Zilles K. Characterization of neuronal migration disorders in neocortical structures: extracellular in vitro recordings. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:3085–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti S, Gaglini P, Granato A, Di Rocco C. Organization of callosal connections in rats with experimentally induced microgyria. Childs Nerv Syst. 1999;15:444–8. doi: 10.1007/s003810050435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannetti S, Gaglini P, Di Rocco F, Di Rocco C, Granato A. Organization of cortico-cortical associative projections in a rat model of microgyria. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2185–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200007140-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen GD, Burstein D, Galaburda AM. Changes in efferent and afferent connectivity in rats with induced cerebrocortical microgyria. J Comp Neurol. 2000;418:423–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaburda AM, Menard MT, Rosen GD. Evidence for aberrant auditory anatomy in developmental dyslexia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8010–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman AE, Galaburda AM, Fitch RH, Carter AR, Rosen GD. Cerebral microgyria, thalamic cell size and auditory temporal processing in male and female rats. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7:453–64. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiffer AM, Rosen GD, Fitch RH. Rapid auditory processing and MGN morphology in microgyric rats reared in varied acoustic environments. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;138:187–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen GD, Herman AE, Galaburda AM. Sex differences in the effects of early neocortical injury on neuronal size distribution of the medial geniculate nucleus in the rat are mediated by perinatal gonadal steroids. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:27–34. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denenberg VH, Sherman GF, Morrison L, Schrott LM, Waters NS, Rosen GD, Behan PO, Galaburda AM. Behavior, ectopias and immunity in BD/DB reciprocal crosses. Brain Res. 1992;571:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90671-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denenberg VH, Sherman G, Schrott LM, Waters NS, Boehm GW, Galaburda AM, Mobraaten LE. Effects of embryo transfer and cortical ectopias upon the behavior of BXSB-Yaa and BXSB-Yaa plus mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;93:100–108. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MG, Rosen GD, Tallal P, Fitch RH. Impaired processing of complex auditory stimuli in rats with induced cerebrocortical microgyria: An animal model of developmental language disabilities. J Cogn Neurosci. 2000;12:828–39. doi: 10.1162/089892900562435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch RH, Tallal P, Brown CP, Galaburda AM, Rosen GD. Induced microgyria and auditory temporal processing in rats: a model for language impairment? Cereb Cortex. 1994;4:260–70. doi: 10.1093/cercor/4.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch RH, Brown CP, Tallal P, Rosen GD. Effects of sex and MK-801 on auditory-processing deficits associated with developmental microgyric lesions in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111:404–12. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen GD, Waters NS, Galaburda AM, Denenberg VH. Behavioral consequences of neonatal injury of the neocortex. Brain Res. 1995;681:177–89. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00312-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K. The Cortex of the Rat: A Sterotaxic Atlas. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. 1985.

- Rosenzweig MR, Krench D, Bennett EL, Diamond MC. Effects of environmental complexity and training on brain chemistry and anatomy: A replication and extension. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1962;55:429–437. doi: 10.1037/h0041137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett EL, Rosenzweig MR, Diamond MC. Rat brain: effects of environmental enrichment on wet and dry weights. Science. 1969;163:825–6. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3869.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Torre JC. Effect of differential environmental enrichment on brain weight and on acetylcholinesterase and cholinesterase activities in mice. Exp Neurol. 1968;22:493–503. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(68)90144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Froese N, Sade DS, Dudek BC. Sex differences in brain/body relationships of Rhesus monkeys and humans. J Hum Evol. 1999;36:233–8. doi: 10.1006/jhev.1998.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakkenberg B, Gundersen HJ. Neocortical neuron number in humans: effect of sex and age. J Comp Neurol. 1997;384:312–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, Cioe J. Recovery from early cortical damage in rats, VIII. Earlier may be worse: behavioural dysfunction and abnormal cerebral morphogenesis following perinatal frontal cortical lesions in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:756–64. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb B, Holmes C, Whishaw IQ. Recovery from early cortical lesions in rats. III. Neonatal removal of posterior parietal cortex has greater behavioral and anatomical effects than similar removals in adulthood. Behav Brain Res. 1987;26:119–137. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(87)90161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamenhof S, Guthrie D, van Marthens E. Neonatal rats with outstanding values of brain and body parameters. Life Sci. 1976;18:1391–6. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamenhof S, van Marthens E, Grauel L. DNA (cell number) in neonatal brain: second generation (F2) alteration by maternal (F0) dietary protein restriction. Science. 1971;172:850–1. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3985.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak K, Feit J. Migration of neuroblasts through partial necrosis of the cerebral cortex in newborn rats-contribution to the problems of morphological development and developmental period of cerebral microgyria. Histological and autoradiographical study. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1977;38:203–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00688066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak K, Feit J, Jurankova Z. Experimentally induced focal microgyria and status verrucosus deformis in rats – pathogenesis and interrelation. Histological and autoradiographical study. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1978;44:121–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00691477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen GD, Press DM, Sherman GF, Galaburda AM. The development of induced cerebrocortical microgyria in the rat. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1992;51:601–11. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199211000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen GD, Harry JD. Brain volume estimation from serial section measurements: A comparison of methodologies. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;35:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90101-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]