Abstract

In Australia, physiotherapy is a primary contact profession when practiced in private ambulatory settings. Primary contact means that physiotherapists take responsibility for diagnosis, decisions on interventions, appropriate ongoing management, and costs related to benefits. For most physiotherapists, the most common clinical presentations relate to symptoms from musculoskeletal conditions. There is considerable research evidence for many “physiotherapy” techniques in the management of musculoskeletal symptoms. As part of these management strategies, some physiotherapists may use nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as an adjunct to treatment. Physiotherapists do not have the training or the legislative powers to prescribe NSAIDs. However, they can recommend that patients seek advice about appropriate adjunct NSAIDs from pharmacists and/or medical practitioners. The roles and responsibilities of key health providers in this area appear to be well defined in terms of minimizing medication misadventure and optimizing patient health outcomes. A recent survey of physiotherapist behaviors and practices, however, identified a number of “gray” areas that could confront unwary physiotherapists, or pose dilemmas for those without the support of medical/pharmacist colleagues. These gray areas relate to the adjunct use of topical NSAIDs in physiotherapy management and making recommendations for the use of oral NSAIDs. This paper reports on qualitative data that highlights the dilemmas confronting physiotherapists.

Keywords: physiotherapy, antiinflammatory agents, legal and ethical issues

Introduction

Physiotherapists in Australia often work in community settings as primary contact practitioners where they treat a range of musculoskeletal conditions, from acute sprains and strains to chronic inflammatory conditions (Grimmer et al 1998). As highlighted by Moore et al (1998), nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are by far the most common pharmaceuticals used for managing these symptoms and, hence, are often adjunct therapy to physiotherapy management of musculoskeletal conditions. The cost to the Australian community in the management of musculoskeletal disorders is in excess of 15 billon Australian dollars per annum (Access Economics 2001a, 2001b cited in AAMPGG 2003), and given the recent recognition of the role of physiotherapy in the management of chronic musculoskeletal conditions by the Australian Government Medicare legislation (Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing 2003), it could be presumed that the place of physiotherapy in managing musculoskeletal conditions is assured in the eyes of the public. In recent years, there has been improved community access to NSAIDs. Due to changes to drug scheduling, many common NSAIDs are now available in non-prescription over-the-counter forms in supermarkets and pharmacies.

The assumption underlying the purchase of NSAIDs from a pharmacy is that appropriate professional advice would be supplied along with the drug at the point of sale. This information is currently not available in the supermarket. More potent NSAIDs are available on prescription from medical practitioners.

The Quality Use of Medicines policy refers to selecting appropriate pharmaceutical management, and advising on the safe and effective use of medicines (Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing 2002). Current legislation in Australia precludes physiotherapists from prescribing, supplying, or selling NSAIDs in their clinical settings. The scheduling of therapeutic drugs is monitored via the Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Drugs and Poisons, which is adopted from the South Australia Controlled Substances (Poisons) Regulation, 1996. The legislation governing access to scheduled medicines is the Controlled Substances Act 1984 and the Controlled Substances (Poisons) Regulation 1996. As per these legislations, only medical practitioners and dentists are permitted to prescribe Schedule 4 (prescription-only) medicines within the ordinary course of their profession. Access to these medicines would be through the dispensing of such a prescription by a pharmacist. Access to Schedule 2 pharmacy and Schedule 3 pharmacist-only medicines is also only from a pharmacy. Physiotherapists are not permitted to prescribe, sell, or supply Schedule 2, 3, and 4 medicines.

The gray area related to physiotherapist involvement with NSAIDs concerns the reference to drugs that are classified as S2 Expect; ie, the product is unscheduled and therefore can be sold outside pharmacies such as in supermarkets. While the legislation is very clear on the supply, sale, and use of S2, 3, and 4, the legislation does not control the sale or supply of unscheduled medicines. This has been left as a matter of professional practice.

This legislation protects physiotherapists from situations where their limited training in pharmacology could inadvertently place their patient at risk of greater harm than good when using NSAIDs as an adjunct to physiotherapy management. Thus, the expected approach taken by physiotherapists to ensure that patients use NSAIDs appropriately as an adjunct to physiotherapy management is for the physiotherapist to recognize the potential role of oral or topical NSAIDs in individual symptom management, then to recommend this in a general sense to the patient, and to advise the patient to discuss the matter further with the pharmacist or the general medical practitioner. It is inappropriate for physiotherapists to recommend a particular brand of NSAIDs to a patient (which is seen as anecdotal evidence) or to provide NSAIDs (stock or sell) in any form in the physiotherapy clinic. Grimmer et al (2002), reporting on quantitative data from a survey of physiotherapists, highlighted legal and ethical issues underpinning the use of NSAIDs in every day clinical practice. These findings were supported by Lansbury and Sullivan (1998, 1999) who also identified the need for educating physiotherapists on aspects of NSAIDs.

It seems clear that there is the potential for patients who have experienced a NSAIDs misadventure as a result of inappropriate recommendation by a physiotherapist (without seeking advice from appropriate health professionals), to undertake legal action against the physiotherapist.

Typical symptoms of medication misadventure from NSAIDs are listed in Table 1. Drugs with which NSAIDs ingestion is currently considered inappropriate are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Commonly reported side effects with NSAIDs

| Systems affected | Symptoms reported |

|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | Heartburn, dyspepsia, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, nausea, stomatitis, decreased appetite, vomiting |

| Central nervous system | Headache, insomnia, dizziness, drowsiness, tinnitus, confusion (more common in the elderly), unusual weakness |

| Ocular | Visual disturbances such as loss of visual acuity, blurred, or double vision |

| Dermatologic | Itching, skin rash, photosensitivity reactions, eruptions, hives |

| Cardiovascular | Edema, palpitations, fast heartbeat |

| Genitourinary | Dysuria, vaginal bleeding, blood in urine, cystitis |

Source: Data adapted from Lukazewski (2004).

Abbreviation: NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Table 2.

Types of drugs contraindicated/interactions with NSAIDs

| Anticoagulants |

| ASPRIN/DISPRIN |

| Antihypertensives |

| Asthma medications |

| Lithium |

| Some cardiac medications |

Source: Data adapted from AMA-CME (2004).

This paper reports qualitative evidence on the understanding of the role of physiotherapists in the use, recommendation, and delivery of NSAIDS. The 2002 survey involved interviews with physiotherapists working in a range of practice settings in Australia. Providing additional and adjunct findings to those reported in Grimmer et al (2002), this paper summarizes qualitative findings of the same study. Pitfalls for physiotherapists regarding inappropriate NSAIDs practices are highlighted, and the need for physiotherapists to be regularly informed of legislative requirements is discussed.

Methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was provided by the University of South Australia, and participants provided verbal consent to participate in the project.

Subjects

The subjects were a purposive sample of physiotherapists registered to practice in South Australia (SA), Tasmania, and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). These three sites provided ideal comparisons for collecting information on physiotherapists' knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes to NSAIDs because they reflected different types of practice locations, as well as the influence of teaching schools and professional practice philosophies. Physiotherapists in ACT reflected generally urban or semi-rural practice, whilst physiotherapists in SA and Tasmania were a mix of urban, large, and small rural and remote practices. At the time of the survey (2001–2002), there were no physiotherapy university teaching schools in Tasmania or ACT.

Purposive sampling was the sampling method of choice as dictated by the research design of the project (Barbour 2001). These physiotherapists were identified by members of the project steering committee, as those who were interested in medication usage in physiotherapy practice. Attempts were made to ensure the subjects were evenly distributed throughout the three states and were a diverse group representing both private and public practitioners. The steering committee consisted of different stakeholders from the physiotherapy profession and external agencies (three experienced private practitioners from the three participating states, two experienced public practitioners). This included the head of a physiotherapy school, the director of the local branch of the Australian Physiotherapy Association, a health economist, and a surveyor of a quality endorsement program of the Australian Physiotherapy Association. These members were asked to identify key private and public practitioners within their respective states for individuals who had an interest in medications and its use in physiotherapy.

Data collection and analysis

In-depth telephone interviews were conducted with consenting physiotherapists to establish a framework of knowledge and use of NSAIDs in clinical practice, and to identify issues of concern regarding physiotherapists and NSAID use. These interviews were conducted over a period of one month and typically each interview was conducted for approximately 20 minutes. Interviews were conducted by one of the research team (SK) based on a series of questions outlined in a semi-structured format. The questions were provided to physiotherapists prior to the interview.

The interviews were audio taped, later transcribed, and synthesized by key themes and concepts. These synthesized findings were validated using hand written notes taken during the interviews to verify the trustworthiness and credibility of the data. Data were collected from participants until saturation was attained (Rice and Ezzy 1999). Follow-up interviews were conducted if additional information and/or clarification of the initial interview data were required.

Results

Subject demographics

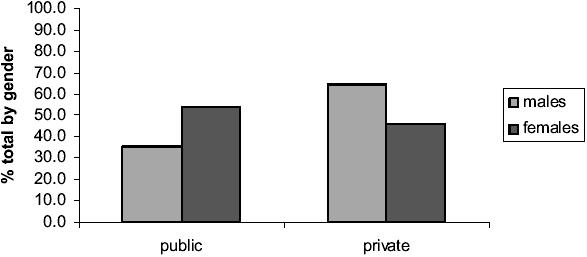

Forty-two physiotherapists were identified by the project steering committee as key practitioners with an interest in NSAIDs and their use in physiotherapy. One of the research team (SK) invited these physiotherapists by phone or email to participate in the project. Twelve physiotherapists either rejected the invitation due to various reasons or were unable to be contacted. Common reasons for not participating in the study were lack of time, heavy current work load, holidays, or illness. Thirty physiotherapists provided consent to participate, and were interviewed for this study (17 men and 13 women). The average age (standard deviation) was not significantly different for men and women, being 38.8 (SD 9.8) years for men and 40.4 (SD 7.8) years for women. Fourteen of the participants were from SA, eight from ACT, and eight from Tasmania. These proportions reflected the proportions of physiotherapists registered to work in these states at this time (personal communication with Physiotherapy Registration Boards in each of these states 2002). There were different percentages of male and female participants working in public and private sectors (Figure 1); however, there was no significant influence of location (state) on these percentages.

Figure 1.

Percentage of males and females working in health sectors.

Follow-up interviews were conducted with only three physiotherapists to clarify issues that were raised during the initial interviews. The remainder of the interviews provided complete data and required no further exploration.

Key themes

Key themes synthesized from the interviews are outlined in Table 3. The following sections provide details on each of the key themes raised by the participants. Excerpts taken from the interviews are included.

Table 3.

Key themes synthesized from the interviews

| Common questions asked of physiotherapists |

| Commonly encountered NSAIDs oral medications and topical gels |

| Concerns regarding usage of NSAIDs |

| Knowledge |

| Opportunities for education |

| Opinions of physiotherapists regarding NSAIDs |

| Involvement of GPs and pharmaceutical companies with physiotherapists |

| Practices that were contrary to the legislation or challenged the nature of the interpretation of the legislation |

Common questions asked of physiotherapists

All participants reported that patients regularly asked a range of questions about the nature, use, indications and contraindications, and interactions of NSAIDs. Almost all the interviewed physiotherapists agreed that patients were not fully informed or knowledgeable about these medications and that they perceived physiotherapists as having reliable and up-to-date knowledge in this area. (See following excerpt.)

I don't believe that physiotherapists should take a role in drug therapy advice – just as I don't believe we should give advice on diet. General advice is OK, but always back it up with suggestions that they speak to their GP/pharmacist.

I feel I don't have the knowledge or expertise to recommend NSAIDs, especially to an aged population who are more likely to have conditions which are contraindicated for NSAIDs. GPs and pharmacists have knowledge of drug adverse reactions as well as medication interactions. Patients don't always know the details of their current medications or medical history and so physiotherapists shouldn't be responsible for NSAID prescription or advice.

Commonly encountered NSAID oral medications and topical gels

Respondents reported that there were a number of NSAID oral medications and topical gels that they commonly encountered – either from patient discussions, or through personal experience. Physiotherapists reported that they were often put in situations where they had to “recommend” these medications to patients. With respect to topical agents, there were differing opinions by physiotherapists about NSAIDs efficacy, and few physiotherapists were aware of up-to-date research information (such as systematic reviews) that provided best practice information. An area of real concern was in therapists' knowledge about topical NSAIDs (ie, their efficacy as an adjunct to physiotherapy management, whether there was a systemic effect on the patient, or whether there were any potentially adverse effects for the therapist administering it).

Physiotherapists are in an ideal position to reinforce the advice of GPs re NSAIDs – both their indications and precautions. Physios are often the first contact practitioner and need to know enough about NSAID indications/contraindications to be able to refer on to the GP for prescription when required.

For more chronic conditions involving swelling I consider topical NSAIDs helpful if the dosage is right. I would appreciate more information regarding the legal side, contraindications, and any research regarding topical NSAIDs effect on tissue healing rates.

While massaging or using ultrasound, I like the “double” advantage of using NSAID gel medium to help the cause of my patients. Accountability of oral NSAIDs should remain with trained pharmacists/doctors.

Concerns regarding usage of NSAIDs

Almost all interviewed physiotherapists reported having concerns about the way NSAIDs were, or could be used in their practice. Commonly reported concerns were lack of proper knowledge about NSAIDs when dealing with patients, lack of adequate education of patients by the relevant prescriber or supplier (GPs and pharmacists), use of “cocktails” of drugs, long-term use of NSAIDs, etc.

NSAIDs kill people. Drugs and side effects cause so many problems because of inadequate education. Short-term NSAIDs for some patients seem to be useful. Long-term NSAIDs need to be prescribed and monitored by doctors. Over-the-counter drugs should only be advised by physios who have not been trained.

Knowledge

Almost all the physiotherapists interviewed reported that their knowledge of NSAIDs was poor to average, and few reported that their undergraduate or postgraduate education had been sufficient for them to understand the finer aspects of NSAIDs action or range of effects.

I will normally suggest (patients) see their GP. If their general health is good, I may recommend an over-the-counter NSAID, ie, gel or tablet, but to discuss it with the pharmacist first. I only warn them of the GI [gastrointestinal] problems as that is all I am aware of. It would be good to know more, but I don't think that it is our role to prescribe the higher dose NSAIDs as we have poor knowledge on drugs and interactions with other medications.

Opportunities for education

Matching physiotherapist concerns about their knowledge on NSAIDs was the lack of available and easily accessible education provided to practicing physiotherapists about the use of NSAIDs. This involved not only Quality Use of Medicines (QUM)1 principles and legislation details, but also information on existing and new NSAIDs, their actions, contraindications, dosages, and side effects. Often physiotherapists reflected on how little education they had received since graduation. Some suggested that there be increased exposure during undergraduate and postgraduate training, followed by regular and clinically focused updates from their respective professional organizations, relevant to their areas of practice. Knowledge of currently available medications, their action, and possible side effects is an area requiring increased focus.

As physiotherapists, we are often the first point of contact for patients with musculoskeletal disorders. It is our responsibility to recognize conditions which may respond more favourably to NSAIDs and recommend or refer appropriately. It is not our responsibility to recommend particular medications, even if we had more up-to-date information on drug actions and interactions.

Opinions of physiotherapists regarding NSAIDs

Three distinct sets of opinions were identified concerning the use of NSAIDs in physiotherapy clinical practice. The first opinion, mostly expressed by hospital-based physiotherapists, was that physiotherapists should have nothing to do with any medications.

I think that we should stick to our core practice and I don't think that includes prescribing medications. Although I think that we should be able to access NSAIDs for patients by referring to pharmacists.

The second opinion was that since a large number of NSAIDs were available over-the-counter, physiotherapists should be able to recommend and prescribe them. The overwhelming feeling from physiotherapists who gave this response was that physiotherapists should be able to recommend/suggest NSAIDs for specific conditions, but it should be left up to the prescribing doctor/pharmacist to undertake all the screening issues, dosage, etc.

I think NSAIDs complement physiotherapy treatment and are very useful where an acute inflammatory condition exists. As certain drugs which are NSAIDs are already available over the counter (and are marketed as pain killers rather than NSAIDs – and are often sold without adequate warnings or advice on the packet), I think it is appropriate for physiotherapists to advise on their use and offer adequate advice (which is not always forthcoming from pharmacy assistants).

The third opinion came mostly from rural physiotherapists and physiotherapists who worked on the sidelines at sports and recreational activities, who reported that they were often the first contact practitioner with limited opportunity to consult a health professional. These physiotherapists believed that they should be in a position to “prescribe” NSAIDs but still felt it was up to pharmacists to deal with issues of dosage, etc.

I think they [NSAIDs] have a huge place in physio practice. In patients with acute injuries, I am frequently referring them back to the GP to get a prescription for NSAIDs. I think physios should be able to prescribe them themselves (saving their patients and doctors visits and money), but only once they have sufficient knowledge to prescribe safe dosages, contraindications, etc.

Involvement of GPs and pharmaceutical companies with physiotherapists

Most physiotherapists interviewed reported that they often consulted GPs regarding NSAID use. Interestingly, not one physiotherapist had been consulted by pharmaceutical companies about their products, even though physiotherapists perceived themselves as regular customers. Many of the above quotes represent these views.

Practices that were contrary to the legislation, or which challenged the nature of the interpretation of the legislation

The use of topical NSAIDs as an adjunct to electrophysical modalities, particularly when used as a “first-aid” for acute musculoskeletal pain (as a contact medium for ultrasound).

The use of topical NSAIDs as a massage interface.

The recommendation to use specific oral NSAIDs as an adjunct to physiotherapy management, particularly when medical or pharmaceutical advice is not available (for instance in rural areas, or over weekends).

The difference between giving advice as an informed therapist (with up-to-date knowledge of pharmacology), compared with giving advice as a concerned citizen (where evidence is anecdotal at best).

NSAIDs use is a daily issue in my practice. As first contact practitioner, it would make a lot of sense to incorporate this functionality into the physiotherapists' arsenal. It would save on unnecessary duplication of visits to a GP. As experts in musculoskeletal pain/movement and also feel, I am in a very good position to differentiate mechanical from chemical – inflammatory conditions.

The interviews provided information that described common scenarios illustrating the challenges faced by physiotherapists using NSAIDs. The following section reports on three such cases (using fictitious names), which highlight issues that were raised during the interviews, and which reflect the “gray areas” in the interpretation of current legislation.

Case studies

Bill, a physiotherapist with 5-years experience, provides physiotherapy services on a voluntary basis to the local netball team every Saturday. He believes that this exposure will improve his business on Monday mornings. Most of the conditions he encounters on Saturdays are acute inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions. He regularly uses topical NSAIDs in conjunction with electrophysical agents. He was horrified to receive a letter from the local registration board regarding a complaint filed against him by a netballer he had treated with NSAIDs. Subsequent to his treatment, she had developed a skin rash that was resistant to medical intervention. The treating doctor had diagnosed the rash as related to topical NSAID administration and had suggested the netballer take this course of action because he considered the physiotherapist's intervention to be professionally inappropriate.

Sandra works as a rural physiotherapist in private practice. Her clientele are generally elderly folk with chronic conditions. She often treats musculoskeletal complaints of many years standing and is concerned at how much the pain and dysfunction from these conditions restrict her patients' activities of daily living. Sandra had limited access to up-to-date pharmacology advice because the general practitioner was elderly and by his own admission was out of touch with current practice. The local chemist only operated two days a week in town. One Friday evening, she was consulted by Mr Smith, an 80-year-old with acute-on-chronic low back pain. He hadn't slept for several nights and was barely able to stand upright. Sandra could see he required multifactorial management. She provided him with appropriate physiotherapy intervention to reduce his pain and improve his range of movement. She also gave him a sheet of NSAIDs from her own personal supply because there would not be a chemist service until Tuesday. On Saturday evening, Mr Smith was admitted to the local hospital in severe discomfort and with shortness of breath. On investigation it appeared to be related to an adverse interaction between the oral NSAIDs and his antihypertensive and cardiac medications. Sandra was very lucky that neither Mr Smith nor the admitting doctor took the matter any further.

Jill reminded her family that she would be a little late coming home this evening. Tonight was the regular bimonthly visit by the local pharmacist to her physiotherapy practice. All 6 of her staff would be attending, and there were a number of physiotherapists from other practices who were invited. Tonight the pharmacist was presenting information on recently released, over-the-counter NSAIDs. If tonight's presentation was as entertaining and informative as the previous presentation by this pharmacist (on asthma medications), it would be a very worthwhile extra hour spent at work. In her undergraduate and postgraduate training, Jill had been exposed to less than 10 hours of information on pharmacology, much of which had been forgotten in the following years. She had a Monthly Index of Medical Specialties on her shelf but this was several years old, and trying to find the information was very time consuming. The arrangement with the local pharmacist had been in place a year after Jill had queried the nature of a prescription drug taken by one of her patients. It was quickly apparent that physiotherapists could learn a great deal about practical pharmacology from the pharmacists, and it was also apparent that the pharmacist could learn a lot about musculoskeletal symptom management from the therapists. Entertaining as these sessions were, there was the additional benefit of the continuing education points which Jill had negotiated for her staff with the local physiotherapy association for attending.

Discussion

This research identified many core issues associated with NSAIDs and their use by physiotherapists. While it is increasingly more common for physiotherapists to be routinely using and recommending NSAIDs as adjunct to traditional therapy modalities, there is limited undergraduate and postgraduate training in the field of pharmacology, quality use of medicines, ethics of prescription, and key legislative aspects of NSAID use. Physiotherapists who work as primary contact practitioners assume the responsibility for an accurate diagnosis and key decisions on interventions for the acute and chronic management of musculoskeletal conditions. Managing inflammation is one of the key roles in this process. Physiotherapy training allows for the appropriate use of electophysical agents, exercises, and manual therapy but not for directly prescribed medicines.

Prescribing NSAIDs is currently the domain of medical practitioners, and supply of the same is the domain of the pharmacist who has the knowledge and legislative responsibility to provide advice to patients regarding appropriate use and contraindications. The gray area for physiotherapists, highlighted in this research is in the definition of their responsibility to patients when providing “advice” on NSAIDs. While the legislation is clear and specifies that physiotherapists cannot prescribe, provide, or sell NSAIDs, it is unclear regarding the nature and impact of recommendation by physiotherapists relevant to their personal or professional experience. In addition, while the legislation supports physiotherapists in recommending that patients seek advice from their medical practitioner and/or pharmacist, and supports the use of topical NSAIDs as an adjunct to electrophysical therapy and manual therapy, it is unclear regarding the need for the therapist to obtain explicit consent from the patient to use NSAIDs or obtain information from the patient regarding past effects of using NSAIDs.

Recommending the use of a therapeutic product in this instance requires clarification, particularly as a medication misadventure related to current physiotherapy advice could well put a physiotherapist in a difficult legal situation. If physiotherapists recommend (directly to patients) the use of a particular NSAID, they are operating on the same anecdotal evidence level as any lay person, because of the lack of specific training in pharmacology. Furthermore, while the legislation currently supports the sale of “S2 Expect” NSAIDs over-the-counter and in supermarket shelves, the explicit recommendation by a health professional, in this instance a physiotherapist, could be assumed by the patient to be based on greater knowledge than their own, as it is provided by a health professional. This assumes that the physiotherapist is adequately trained and informed about drug indications, contraindications, dosage, and usage. The interviews did not reflect this. Similar dilemmas exist when using NSAIDs as topical agents (massage) and in the form of phonopheresis (ultrasound). This is often undertaken without explicit consent from the patients and, currently, evidence in the literature is lacking to support the use of NSAIDs in this adjunct form. Physiotherapists, however, can recommend the generic use of antiinflammatory and direct patients to the appropriate evidence-based sources.

Conclusion

The legislation relating to NSAID use by physiotherapists is clear. Our interviews highlighted the potential for medication misadventure for patients using other medications, or who were hypersensitive to NSAIDs, because of physiotherapists' variable knowledge of the legislation, and the variable ways in which physiotherapists interpreted the legislation and acted it out. This study also identified opportunities for physiotherapists to unknowingly place themselves at risk of unprofessional behavior by providing advice to patients which may be misinterpreted or result in actual harm.

The areas that could challenge physiotherapists' understanding of the legislation include:

The use of topical NSAIDs as an adjunct to electrophysical modalities, particularly when used in a “first-aid” scenario for acute musculoskeletal conditions.

The use of topical NSAIDs as a massage interface.

The recommendation to use specific oral NSAIDs as an adjunct to physiotherapy management, particularly when medical or pharmaceutical advice is not available (for instance in rural areas, or over weekends).

The difference between giving advice as an informed therapist (which presumes up-to-date knowledge of pharmacology), compared with giving advice as a concerned citizen (where evidence is anecdotal at best).

While the inclusion of NSAIDs in management plans by physiotherapists has the potential to improve patient outcomes, this approach should be undertaken with advice from pharmacists or medical practitioners. Physiotherapists should be aware of the pitfalls of not seeking this advice for every patient.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding support from the Quality Use of Medicines Evaluation Program and The Hospitals Contribution Fund of Australia (HCF). They wish to thank Mr Bill Dollman (DHS SA) for his academic input to the project; the members of the reference and steering committees – Toni Hewitt, John Moss, Mark Smith, Marilynn Pitt, and Lorraine Sheppard – who gave their time freely and with unflagging enthusiasm; and the participating physiotherapists.

Notes

QUM is defined as selecting management options wisely, choosing suitable medicines if a medicine is considered necessary, and using medicines safely and effectively (Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing 2002).

References

- [AAMPGG] Australian Acute Musculoskeletal Pain Guidelines Group. Evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain. Brisbane: Australian Academic Pr; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Access Economics. The prelevance, cost and disease burden of arthritis in Australia. A report prepared for The Arthritis Foundation of Australia. Canberra: Access Economics; 2001a. [Google Scholar]

- Access Economics. The burden of brittle bones: costing osteoporosis in Australia. A report prepared for Osteoporosis Australia. Canberra: Access Economics; 2001b. [Google Scholar]

- AMA-CME. Potential drug interactions with NSAID analgesics [online] 2004. Accessed 18Oct 2004. URL: http://www.ama-cmeonline.com/pain_mgmt/module02/pop_up/table02_inter_nsaids.htm.

- Barbour RS. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ. 2001;322:1115–17. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing 2002. The national strategy for quality use of medicines in Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. Medicare – for all Australians [online] 2003. Accessed 13 Oct 2004. URL: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/wcms/publishing.nsf/Content/health-budget2003-book.htm.

- Grimmer K, Kerr J, Hughes K, et al. An overview of the Australian Physiotherapy Association accredited practice data collection 1995–1996. Aust J Physiother. 1998;44:61–3. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer K, Kumar S, Gilbert A, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): physiotherapists' use, knowledge and attitudes. Aust J Physiother. 2002;48:82–91. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansbury G, Sullivan G. Physiotherapist and drug administration: a survey of practices in New South Wales. Aust J Physiother. 1998;44:231–7. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(14)60382-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukazewski A. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. 2004. Accessed 17 Aug 2004. URL: http://www.agenet.com/Category_Pages/document_display.asp?Id=515.

- Moore RA, Tramer MR, Carroll D, et al. Quantitative systematic review of topically applied non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ. 1998;316:333–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice PL, Ezzy D. Qualitative research methods. A health focus. Melbourne: Oxford Univ Pr; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan G, Lansbury G. Physiotherapists' knowledge of their client medication: a survey of practising physiotherapists in New South Wales, Australia. Physiother Theory Pract. 1999;15:197–8. [Google Scholar]