Abstract

Ciclesonide is a nonhalogenated corticosteroid that is converted to its clinically active metabolite, desisobutyryl-ciclesonide, by esterases in the airways. Pharmacodynamic studies have shown that inhaled ciclesonide has potent antiinflammatory activity in patients with asthma, and does not appear to have clinically relevant systemic effects, even at high doses. It is highly protein-bound and rapidly metabolized by the liver, and thus has a low oral bioavailability. Ciclesonide is formulated as a solution for inhalation using a hydrofluoroalkane pressurized metered-dose inhaler. This formulation delivers a high fraction of respirable particles that yield high lung deposition with even distribution throughout the lungs and minimal oropharyngeal deposition. Results from numerous 12-week trials in patients (including children) with varying degrees of asthma show that morning or evening dosing with ciclesonide is more effective than placebo, and at least equivalent to other inhaled corticosteroids such as budesonide and fluticasone, with regard to improved spirometry, symptom scores, and less need for rescue medication. Results with once-daily ciclesonide are similar to those with twice-daily budesonide or fluticasone. At the dosages used in clinical trials, ciclesonide did not exert any untoward adverse effects and did not affect cortisol production. The favorable pharmacological properties of ciclesonide help explain the low incidence of adverse events, which are mostly mild to moderate in nature. Once-daily ciclesonide offers an efficacious treatment option for stepwise asthma management when inhaled corticosteroids are required.

Keywords: ciclesonide, asthma, inhaled corticosteroids, adults, children

Introduction

The number of persons worldwide with asthma has increased to around 300 million, and may reach 400 million by 2025 (GIA 2005). The reasons for this dramatic increase are under investigation and may relate to adoption of Western lifestyles and urbanization (GIA 2005). About 1% of all disability-adjusted life years are lost due to asthma, and asthma accounts for 1 in every 250 deaths worldwide (GIA 2005). Asthma is characterized by bronchospasm and inflammation, and airway remodeling may occur in some patients – all of which can result in moderate and severe persistent disease requiring long-term management (NAEPP 2002).

There is a problem with under-diagnosis of asthma (Hasselgren et al 2001) and, once diagnosed, with inadequate management of underlying inflammation, particularly in patients with intermittent disease. A study in adolescents with mild intermittent asthma found evidence of persistent airway inflammation, which suggests that these patients may benefit from early intervention with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) (Spallarossa et al 2003). Such intervention in mild persistent asthma improves asthma control and reduces the risk of severe asthma exacerbations (Pauwels et al 2003).

Inhaled corticosteroids are the cornerstone of asthma therapy and are recommended for daily control of mild, moderate, and severe persistent asthma in adults and children (GIA 2004). While the established efficacy of ICS in asthma has led to their acceptance as first-line control of persistent asthma (GIA 2004), their use may be limited by local adverse effects such as oral candidiasis, and there is some concern about potential long-term systemic effects, including cortisol suppression, growth retardation in children, and risk of osteoporosis and fractures (Ellepola and Samaranayake 2001; Salvatoni et al 2003; Hubbard and Tattersfield 2004). Ciclesonide is a new once-daily ICS with similar efficacy to other ICS in asthma, and it possesses potential advantages in terms of reduced local and systemic adverse effects. It is available as 80 μg and 160 μg inhalers. Each actuation delivers either 80 μg or 160 μg of ciclesonide from the mouthpiece (ex-actuator). In the following review, some studies reported the ciclesonide ciclesonide dose released from the valve, ie, ciclesonide 100 μg or 200 μg ex-valve, which are equivalent to ciclesonide 80 or 160 μg ex-actuator, respectively.

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

Ciclesonide is a nonhalogenated ICS that is formulated as a solution for inhalation in a hydrofluoroalkane (HFA) pressurized metered-dose inhaler (MDI). This device delivers ciclesonide in fine particle spray (average particle size 1.1–2.1 μm) that yields a high fraction of respirable particles (Rohatagi, Derandorf, et al 2003; Newman et al 2004; Rohatagi et al 2004). In adult patients with asthma, inhalation of a single dose of 99mTc-labeled ciclesonide 320 μg resulted in a mean of 52% of the ex-actuator dose reaching the lungs (Newman et al 2004). Deposition of ciclesonide within the lung was highest (approximately 55%) in the outermost regions, ie, small airways and alveoli. Oropharyngeal deposition of ciclesonide 800 μg (via HFA MDI) was half that of budesonide 800 μg (via chlorofluorocarbon [CFC] MDI), and conversion of ciclesonide to its active metabolite in the upper oropharynx was very low in a randomized, open-label, sequential treatment study in 18 healthy subjects (Nave, Zech, et al 2005). Oropharyngeal deposition of ciclesonide was also significantly lower than fluticasone in a study of 18 patients with asthma (Figure 1) (Richter et al 2005).

Figure 1.

Deposition characteristics of ciclesonide: (a) Mean (± SD) percentage of a single dose of 99mTc-ciclesonide 320 μg deposited in the lung, oropharynx, esophagus, stomach, or exhaled air filter, in 12 adult patients with asthma (measured by 2D gamma-scintigraphy) (Newman et al 2004); (b) Relative oropharyngeal deposition of ciclesonide 800 μg inhaled via HFA MDI and desisobutyryl-ciclesonide (des-CIC) compared with budesonide 800 μg inhaled via CFC MDI in the first hour following administration, as measured in oropharyngeal wash samples from 18 healthy volunteers (values were calculated using molar dose-adjusted area under the curve data) (Nave R, Zech K, Bethke TD. 2005b. Lower oropharyngeal deposition of inhaled ciclesonide via hydrofluoroalkane metered-dose inhaler compared with budesonide via chlorofluorocarbon metered-dose inhaler in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 61:203-8. Copyright © 2005. Reproduced with permission from European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology); (c) Relative oropharyngeal deposition of ciclesonide 800 μg inhaled via HFA MDI and des-CIC compared with fluticasone propionate 1000 μg inhaled via HFA MDI in the first hour following administration in 18 patients with asthma.(Richter et al 2005).

*p < 0.0001 versus active comparator.

† p < 0.001 versus active comparator.

Abbreviations: CIC, ciclesonide; CFC, chlorofluorocarbon; HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; MDI, marked-dose inhaler; SD, standard deviation.

Animal (Nave, Meyer, et al 2005) and in vitro (Nave et al 2003) studies showed that ciclesonide is converted by esterases in lung tissue to the pharmacologically active metabolite, desisobutyryl-ciclesonide (des-CIC), which has a 100-fold greater glucocorticoid receptor binding affinity than ciclesonide (Stoeck et al 2004). An in vitro study in human lung tissue slices showed a high proportion of des-CIC conjugation with fatty acids (Nave et al 2003). These lipid conjugates of des-CIC may explain the prolonged local antiinflammatory action of ciclesonide in the lung and its clinical efficacy with once-daily dosing.

The pharmacokinetics of ciclesonide and des-CIC were equivalent in 12 healthy volunteers and 12 patients with asthma after inhalation of a single dose of ciclesonide 1240 μg (ex-actuator MDI) (Bethke et al 2003). Pooled pharmacokinetic data from 151 healthy subjects and patients with asthma who participated in phase I studies show des-CIC has a clearance of 396 L/hr and a volume of distribution of 1190 L (Rohatagi, Arya, et al 2003).

Ciclesonide and des-CIC are highly protein-bound (∼99%), which is an advantage over other ICS because it results in a low proportion of free, unbound drug in the systemic circulation (Rohatagi et al 2005) (Figure 2). In In vitro studies show that ciclesonide is metabolized by hepatocytes to des-CIC within the first hour of exposure (Gu et al 2004). Des-CIC is, in turn, extensively metabolized to inactive metabolites (Nave et al 2003; Gu et al 2004). Elimination of des-CIC and other metabolites is predominantly through the feces (Nave, Bethke, et al 2004). Because of extensive first-pass metabolism, the systemic bioavailability of des-CIC after oral ingestion is < 1% (Nave, Bethke, et al 2004). Thus, any ciclesonide swallowed after oral inhalation does not contribute to the systemic availability of the drug or its active metabolite. In addition, low systemic exposure to unbound des-CIC suggests a low potential for systemic adverse events after oral inhalation.

Figure 2.

Fraction of free, unbound drug in plasma for des-CIC (Rohatagi et al 2005), fluticasone propionate (FP) (Rohatagi et al 1996), budesonide (BUD) (Ryrfeldt et al 1982), beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP) (Martin et al 1975), and flunisolide (FLU) (Mollmann et al 1997).

Pharmacodynamics

Up to one third of des-CIC may be converted to lipophilic fatty acid esters that reside in lung tissue (Nave, Schmidt, et al 2004). Binding affinity of des-CIC to glucocorticoid receptors is comparable with budesonide (Stoeck et al 2004) and fluticasone (Belvisi et al 2005), and potent dose-dependent antiinflammatory activity in human bronchial epithelial cells have been described (Serpero et al 2004). Studies in rats showed that ciclesonide prevented and reversed allergic airways inflammation and remodeling (Leung et al 2005).

Inhaled ciclesonide (800 μg dry powder via Cyclohaler® twice daily for one week) reduced early- and late-phase reactions, compared with placebo, after allergen challenge in patients with asthma (Larsen et al 2003), and a minimally effective dose of 80 μg once daily was identified (Gauvreau et al 2005). Ciclesonide also reduced airway responsiveness to adenosine-5′-monophosphate (AMP) in a dose-dependent manner (100–1600 μg dry powder via Cyclohaler daily) in 29 patients with mild to moderate asthma (Taylor et al 1999). Ciclesonide (400 μg ex-valve HFA MDI in the morning) reduced airway responsiveness and inflammation similar to budesonide (400 μg via Turbuhaler®) in 15 patients with mild asthma (Kanniess et al 2001). Reduced methacholine or AMP hyperresponsiveness was observed with dosages of ciclesonide (400–1600 μg ex-valve HFA MDI) and fluticasone (500–2000 μg ex-valve CFC MDI) in two studies of patients with asthma (Lee et al 2004; Derom et al 2005). Attenuation of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction by ciclesonide (40–320 μg ex-actuator MDI daily) was found in a study of 26 affected adults (Subbarao et al 2005).

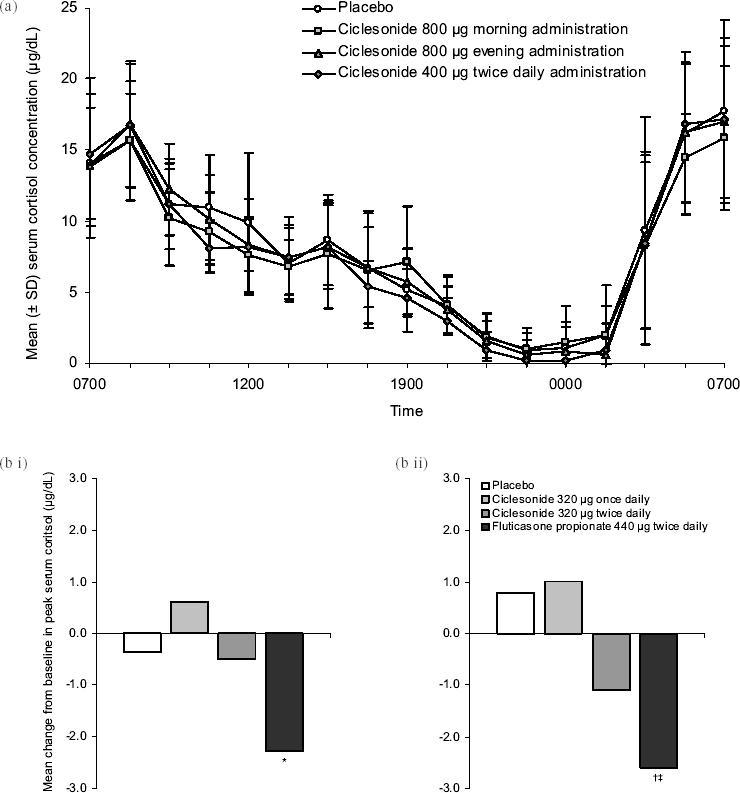

Treatment with ciclesonide does not appear to have a clinically relevant effect on serum cortisol (Figure 3). There was no difference in serum cortisol concentrations when inhaled ciclesonide (800 μg ex-valve MDI daily for 7 days) was compared with placebo in 12 healthy volunteers (Weinbrenner et al 2002). Placebo-controlled studies in patients with asthma showed similar results at dosages up to 1280 μg (ex-actuator HFA MDI) daily for as long as 12 weeks (Chapman et al 2002; Ukena et al 2003; Kerwin et al 2004; Derom et al 2005; Lipworth et al 2005). In studies of up to 12 weeks’ duration, ciclesonide (320–1280 μg ex-actuator HFA MDI daily) had significantly less effect on cortisol production than fluticasone propionate (880–1760 μg daily, ex-actuator HFA MDI or CFC MDI) (Derom et al 2005; Lee et al 2005; Lipworth et al 2005). An analysis of 17 trials in adults and children with asthma showed that inhaled ciclesonide (up to 1280 μg daily) had a negligible effect on endogenous cortisol concentrations (Pfister et al 2004). Switching to ciclesonide (800–1600 μg ex-valve MDI daily for up to 52 weeks) following high-dose therapy with another ICS was found to improve serum cortisol and markers of bone formation (O’Connor, Kilfeather, et al 2002; O’Connor, Sips, et al 2002). Short-term lower-leg growth rate was not affected by inhaled ciclesonide (40–160 μg HFA MDI daily for 2 weeks) in a study of 24 children with asthma (Agertoft and Pedersen 2005).

Figure 3.

Effects of ciclesonide treatment on serum cortisol levels: (a) Mean (± SD) 24-hour serum cortisol levels in 12 healthy male subjects on day 7 of treatment with either placebo or ciclesonide in a randomized, double-blind, cross-over study (Weinbrenner A, Huneke D, Zschiesche M, et al. 2002. Circadian rhythm of serum cortisol after repeated inhalation of the new topical steroid ciclesonide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 87:2160–3. Copyright © 2002. Reproduced with permission from the Endocrine Society); (b) Mean change from baseline in serum cortisol levels after 12 weeks of treatment in adult patients with mild to moderate persistent asthma randomized to receive placebo (n = 41), ciclesonide 320 μg once daily (n = 40), ciclesonide 320 μg twice daily (n = 42), or fluticasone propionate 440 μg twice daily (n = 41) (Lipworth BJ, Kaliner MA, LaForce CF, et al. 2005. Effect of ciclesonide and fluticasone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in adults with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 94:465–72. Copyright © 2005. Reproduced with permission from the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology). Serum cortisol levels were measured following sequential stimulation with (i) low-dose (1 μg) and (ii) high-dose (250 μg) cosyntropin. Changes observed with ciclesonide treatment were not statistically different from placebo.

*p < 0.0001 versus active comparator.

† p < 0.001 versus active comparator.

Clinical Studies

Efficacy

Ciclesonide has been studied in numerous 12-week trials with comparison against baseline, placebo, and other ICS (Table 1). A placebo-controlled study of ciclesonide (80 or 320 μg ex-actuator HFA MDI each morning over 12 weeks) given to 360 patients with bronchial asthma (previously treated with constant beclomethasone dipropionate) showed that both dosages significantly improved peak expiratory flow (PEF) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) compared with placebo (Langdon et al 2005). These results were corroborated in a similar 12-week trial of 329 patients with persistent asthma (Chapman et al 2005). Compared with placebo, ciclesonide 160 or 640 μg (ex-actuator HFA MDI) once daily in the morning were equally effective at maintaining morning PEF (p < 0.0001 for both doses), FEV1 (p < 0.05) and forced vital capacity (FVC) (p < 0.05) (Chapman et al 2005). An open extension of this trial showed that ciclesonide was effective over a period of 52 weeks (Chapman et al 2002). A collation of 2 identical placebo-controlled trials in 1015 patients with mild to moderate asthma showed that ciclesonide (80, 160, or 320 μg ex-actuator HFA MDI daily for 12 weeks) significantly improved FEV1 (p = 0.0007, p = 0.0004, p < 0.0001, respectively) and reduced symptoms (p < 0.0001 for all dosages), daily albuterol use (p < 0.0001), and discontinuations (p < 0.0001) compared with placebo (Pearlman et al 2005). These results confirmed findings from a 12-week trial of ciclesonide 400 versus 800 μg (ex-valve MDI) twice daily in 365 patients with asthma pretreated with high-dose ICS, where improved PEF and a decrease in symptoms and rescue medications were found after 12 weeks of therapy (both doses produced equivalent results) (O’Connor, Sips, et al 2002). FEV1 improvements were maintained over a 40-week open extension of this study (O’Connor, Kilfeather, et al 2002).

Table 1.

Efficacy and tolerability of ciclesonide in patients with asthma in clinical studies of 12 weeks’ duration

| Study | Study design (n) | Inclusion criteria | Dosages (μg) | Main results | Overall efficacy | Tolerability and quality of life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langdon et al 2005 | mc, r, pg, db, P n = 360 | Low–moderate-dose ICS; FEV1 60%–90% predicted; demonstrated reversibility | C 80 od am C 320 od am | PEFam: C80 > P (p = 0.0012); C320 > P (p=0.0006) PEFpm: C80 > P (p = 0.0121); C320 > P (p=0.0048) FEV1: C80 > P(p=0.0044); C320 > (p=0.0001) FVC: C80 > P (p=0.0203); C320 > P(p=0.0197)SR; C>P(p<0.0001 change from BL) Resc:C<P(p<0.01 change from BL) LOE: C80> P(p≤0.0052); C320> P(p<0.0001); C320>C80 (p=0.0087) | C > P | Safe and well tolerated Serum and urinary cortisol levels: C80≡C320≡P |

| Chapman et al 2005 | mc, r, pg, db, P n=329 | Moderate-dose ICS; FEV1 60%–90% predicted; demonstrated reversibility | C 160 od am C 640 od am | PEFam: C160 ≡ C640 > P (p < 0.0001AD) FEV1: C160 ≡ C640 > P(p < 0.05 AD) FVC: C160 ≡ C640 > P (p < 0.05 AD) SR: C > P (p ≤ 0.0006 change from BL) Resc: C < P(p < 0.0001 change from BL) LOE: P > C160≡C640 (p < 0.0001 AD) | C160 ≡ C640 > P | Cortisol levels C160≡C640≡P |

| Berger et al 2004; Nayak et al 2005,Pearlman et al 2005 | mc, r, pg, db, P n = 1015 | Mild to moderate asthma; FEV1 60%–80% predicted; ≥ 12 years old | C 80 od C160 od C 320 od | FEV1:C80>P(p=0.0007);C160 > P(p=0.0004); C320 > P(p<0.0001) SR: C < P (p<0.0001 AD) Resc: C < P(p<0.0001 AD) LOE:C <P(p<0.0001 AD) | C > P | Oral candidiasis: C ≡ PHPA function; C had no effect Overall AQLQ: C80, C160, C320 > P (p < 0.0001 AD) |

| O’Connor, Sips, et al 2002 | r, pg, db n = 365 | High-dose ICS; PEF am ≤ 80% predicted; demonstrated reversibility; symptom scores ≥ 4 last week; resc ≥ 14 puffs last week | C 400 bid C 800 bid (C ex-valve) | PEFam: C800 > BL (p = 0.0002); C1600 > BL (p=0.001) SR:C>BL (p<0.0001 AD) Resc: C800 < BL (p=0.0045); C1600≡BNL (p=0.0758) | C400 bid≡C800 bid > BL | Safe and well tolderated Serum and urinary cortisol levels: C > BL (p < 0.05 AD) Serum osteocalcin levels: C > BL (p < 0.05 AD) |

| Postma et al 2001 | r, pg, dba n = 209 | Mild to moderate asthma; FEV150%–90% predicted; demonstrated reversibility; resc meds only during past 4 weeks | C 200 od am C 200 od pm (C ex-valve) | PEFam: Cpm > Cam (p < 0.05) ≡ BL PEFpm: Cpm > BL (p < 0.05) ≡ Cam FEV1: Cam ≡ Cpm > BL (p < 0.05) FVC: Cam ≡ Cpm > BL (p<0.05) SR: Cam ≡ Cpm > BL (p < 0.001) Resc: Cam ≡ Cpm < BL (p<0.05) | Cam ≡ Cpm ≡ BL | Safe and well tolerated Urinary cortisol excretion: Cam = Cpm = BL |

| Hansel et al 2004 | r,pg,db(C); open (Bu) n = 554 | FEV1 50%–90% predicted | C 80 od am C 320 od am Bu 200 bid (Turbuhaler®) | PEFam: C80 ≡ C320 ≡ Bu > BL (p < 0.0001) PEFam: C80 ≡ C320 ≡ Bu > BL (p < 0.0001) FEV1:C80 ≡ C320 ≡ Bu > BL (p < 0.0001) FVC: C80 ≡ C320 ≡ Bu > BL (p < 0.0001) SR: C80 ≡ C320 ≡ Bu > BL (p < 0.0001) Resc: C80 ≡ C320 ≡ Bu < BL (p < 0.0001) | C80 ≡ C320 ≡ Bu > BL | Urinary cortisol excretion: C80 ≡ C320 ≡ BL Bu < BL (p < 0.05) |

| Gadgil et al 2005 | NR n = 404 | Low-dose ICS; FEV1 70% predicted; 2-week run-in with Bu 200 μg twice daily | C 160 od am C 160 od pm Bu 200 bid (pMDI) | FEV1 Cpm ≡ Cpm ≡ Bu ≡ BL SR: Cam ≡ Cpm ≡ Bu ≡ BL Resc: Cam ≡ Cpm ≡ Bu ≡ BL LOE: Cam ≡ Cpm ≡ Bu ≡ BL | Cam ≡ Cpm ≡ Bu | NR |

| Ukena et al 2003 | mc, r, pg, db, dd n = 399 | FEV1 50%–90% predicted | C 320 od pm Bu 400 od pm (Turbuhaler®) | FEV1: C > Bu (p = 0.0185) > BL (p < 0.0001) FVC: C > Bu (p = 0.0335) > BL (p < 0.0001) PEFam: C > Bu (earlier onset) SR: C ≡ Bu > BL | C> Bu > BL | Urinary cortisol levels: C ≡ Bu ≡ BL |

| Boulet et al 2003 | mc, r, pg, db n = 359 | Moderate-dose ICS then Bu 1600 μg od × 2–4 weeks; FEV1 65%–90% predicted on Bu | C 320 od am Bu 400 od am (Turbuhaler®) | FEV1: C ≡ Bu FVC: C > Bu (p < 0.01) SR: C > Bu (p = 0.0288)b Resc: C ≡ Bu | C ≡ Bu | NR |

| Buhl et al 2004 | mc, r, db n = 529 | FEV1 80%–100% predicted, pretreated with low-dose ICS; FEV1 50%–90% predicted after 1–4 weeks without ICS | C 160 od pm F 88 bid | PEFam: C ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0001) F > BL (p < 0.0001) FEV1: C≡ FVC: C ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0001) SR: C ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0001) Resc: C ≡ F < BL (p < 0.0001) | C ≡ F | NR |

| Magnussen et al 2005 | mc, r, db n = 697 | 1–4 weeks without ICS; FEV1 61%–90% predicted; 12–75 years old | C 80 od pm C 160 od pm F 88 bid | FEV1: C80≡C160 ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0051 AD) SR: C80 ≡ C160 ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0001 AD) Resc: C80 ≡ C160 ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0001 AD) | C80 ≡ C160 ≡ F NR | |

| Bernstein et al 2004; Bernstein et al 2005; Busse et al 2005 | mc, r, pg, db, dd, P n = 531 | Moderate to severe asthma; high-dose ICS; FEV1 40%–65% predicted; ≥ 12 years old | C 160 bid C 320 bid F 440 bid | FEV1: C320 > P (p = 0.0374); C640 > P (p = 0.0008); F > P p = (0.0001) SR: C320, C640, F > P (p < 0.0001 AD) Resc: C320, C640, F > P (p < 0.0001 AD) LOE: C320, C640, F > P (p < 0.0001 AD) | C ≡ F | Oral candidiasis: P ≡ C320 ≡ C640 < F HPA function: C320 ≡ C640 ≡ F ≡ P ≡ BL AQLQ: C320, C640, F > P (p < 0.0001) |

| Gelfand et al 2005; Miller et al 2005; Shapiro et al 2005 | mc, r, pg, db, P n = 1031 | Children with mild to severe persistent 60%–85% asthma/FEV1 predicted; 4–11 years old | C 40 od C 80 od C 160 od | FEV1: C40 = P (p = 0.26), C80 > P (p = 0.01), C160 > P (p = 0.008) SR: C40 > P (p = 0.0022), C80 > P (p < 0.0001), C160 > P (p < 0.0001) Resc: C40, C80, C160 < P LOE: C40, C80, C160 < P (p = 0.02 AD) | C > P | Well tolerated in all groups Oral candidiasis: 3 cases (all C) in 1025 patients Serum and urinary cortisol levels: P ≡ C40, C80, C160 Pediatric AQLQ (in 793 children ≥ 7 years old): C40 > P (p = 0.01), C80 > P (p = 0.004), C160 > P (p = 0.002) |

| Pedersen, Garcia, et al 2004; Pedersen, Gyurkovits, et al 2004 | mc, r, db n = 556 | Children and adolescents with mild-to-severe asthma/2–4 weeks without ICS; 50%–90% FEV1 predicted/6 to 15 years old | C 80 bid F 88 bid | PEFam: C ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0001) PEFpm: C ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0001) F > BL (p < 0.0001) FEV1: C≡ SR: C ≡ F > BL (p < 0.0001) Resc: C ≡ F < BL (p < 0.0001) | C ≡ F > BL | Adverse events: C ≡ F Urinary cortisol levels: Cc > F (p = 0.0062) |

8-week study

C produced more symptom-free days

C increased levels from BL

Abbreviations: AD, all/both drug doses; am, morning; AQLQ, Juniper Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire; bid, twice daily; BL, baseline; Bu, budesonide; C, ciclesonide ex-actuator dose via HFA-MDI unless otherwise stated; db, double-blind; dd, double-dummy; FEV1,forced expiratory flow in one second; F, fluticasone propionate ex-actuator dose via MDI; FVC, forced vital capacity; HPA, hypothalamic pituitary adrenal; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LOE, discontinuation due to lack of efficacy; mc, multicenter; n, number of patients; NR, not reported; od, once daily; P, placebo; PEF, peak expiratory flow; pg, parallel group; pm, evening; r, randomized; Resc, need for rescue medications; SR, symptom control (reduction of symptoms).

A study in 209 patients with bronchial asthma showed that ciclesonide 200 μg (ex-valve HFA MDI) for 8 weeks may be given in the morning or evening to produce significant improvements in symptoms (at least p < 0.001 compared with baseline), spirometry (p < 0.05), and rescue medication usage (p < 0.05), with evening dosing significantly improving morning PEF (p < 0.05 compared with morning dosing) (Postma et al 2001).

Compared with other ICS

Ciclesonide has been compared with budesonide and fluticasone in several studies (Table 1). In 554 patients with asthma, ciclesonide 80 or 320 μg (ex-actuator HFA MDI) each morning was equal in efficacy to budesonide 200 μg via (Turbuhaler) twice daily for 12 weeks with regard to significant improvements in FEV1, FVC, PEF, asthma symptoms, and use of rescue medication (Hansel et al 2004). Similar 12-week efficacy to budesonide (200 μg ex-valve MDI twice daily) was found with ciclesonide (160 μg ex-actuator MDI, morning or evening) in a study of 404 patients pretreated with ICS (Gadgil et al 2005). FEV1 was maintained, and level of symptoms and use of rescue medications were decreased or remained stable with all regimens. Evening doses of ciclesonide (320 μg ex-actuator HFA MDI) and budesonide (400 μg via Turbuhaler) have been compared over 12 weeks in 399 patients with asthma (Ukena et al 2003). Ciclesonide produced significantly better FEV1 (p < 0.0185) and FVC (p < 0.0335) results than budesonide and produced an earlier onset of morning PEF improvement (day 3 vs week 2). Once-daily morning regimens of ciclesonide 320 μg (ex-actuator HFA MDI) and budesonide 400 μg (via Turbuhaler) were compared in a study of 359 patients with asthma who had been pretreated with high-dose ICS (Boulet et al 2003). Ciclesonide produced equivalent FEV1 results to budesonide, but better FVC results (p < 0.01), and more symptom-free days (p = 0.0288), and there was no difference between the two drugs in the need for rescue medication.

Ciclesonide 160 μg once daily in the evening has been compared with fluticasone 88 μg twice daily (ex-actuator HFA MDI both drugs) in 529 patients with asthma (Buhl et al 2004). The results showed that ciclesonide produced significant improvements from baseline in FEV1, FVC, and morning PEF (all p < 0.0001 compared with baseline) that were equivalent to fluticasone. Equivalent symptom reduction and need for rescue medication were also observed with the two drugs. Similar results were observed in a study of 697 patients with persistent asthma (Magnussen et al 2005). In this study, equivalency to fluticasone (88 μg twice daily) was found with ciclesonide 80 and 160 μg once daily (all drugs ex-actuator MDI). Ciclesonide has also been compared with fluticasone in 531 patients in severe persistent asthma (Busse et al 2005). Following 12 weeks’ treatment, and compared with placebo, FEV1 improved with fluticasone 440 μg (ex-actuator CFC MDI) twice daily (p < 0.0001) and dose-dependently with twice daily ciclesonide (ex-actuator HFA MDI) 160 μg (p = 0.0374) or 320 μg (p = 0.0008). All 3 regimens improved asthma symptoms and need for albuterol compared with placebo (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons).

Efficacy in children

Ciclesonide (40, 80, or 160 μg ex-actuator HFA MDI once daily) was compared with placebo in a 12-week study of 1031 children with persistent asthma (Shapiro and Bensch 2005). FEV1 significantly improved compared with placebo in all doses. There were fewer discontinuations due to lack of efficacy with ciclesonide, as well as significantly less asthma symptoms, less need for albuterol, and a decrease in nocturnal awakenings, compared with placebo. Another 12-week study compared ciclesonide 80 μg twice daily with fluticasone 88 μg twice daily (both drugs ex-actuator HFA MDI) in 556 children and adolescents with mild to severe asthma (Pedersen, Garcia, et al 2004). Compared with baseline both drugs significantly improved FEV1 and morning and evening PEF. Asthma symptoms and need for rescue medications were lowered with both drugs. The authors concluded that the drugs showed equivalent efficacy in this patient population.

Quality of Life

Quality of life (QoL) assessment in 2 of the studies in Table 1 showed that ciclesonide improved QoL significantly over placebo and was comparable with fluticasone in patients aged 12 years or older (Bernstein et al 2005; Nayak et al 2005). Ciclesonide also improved QoL in children aged 7 years or older in a placebo-controlled study in pediatric patients (Miller et al 2005).

Tolerability

A low propensity for typical ICS adverse events was presented in the pharmacodynamics section of this review. In addition, ciclesonide was well tolerated in all of the clinical trials reported in Table 1. For example, in the placebo-controlled study of 329 patients with persistent asthma, adverse events with ciclesonide (160 or 640 μg ex-actuator HFA MDI once daily for 12 weeks) were mostly mild or moderate and were unrelated to study medication, and severe adverse events were reported in 7% or less of all patients (Chapman et al 2005). The most frequent adverse events included asthma (14% and 13% in ciclesonide 160 and 640 μg groups, respectively, compared with 29% in the placebo group), headache (16%, 13%, and 17%, respectively), upper respiratory tract infection (6%, 8%, and 13%), and rhinitis (15%, 9%, and 13%). Oral candidiasis did not occur, and cortisol levels were similar in all groups.

Table 1 shows the key tolerability results from published studies in adults and children. At the dosages used, ciclesonide did not exert any untoward adverse effects, and did not suppress cortisol production. A pooled analysis of studies shows that among 6846 patients with asthma who were treated with ciclesonide, another ICS, or placebo, the incidence of oral adverse events was similar for ciclesonide and placebo-treated patients, and that other ICS produced the most oral candidiasis and hoarseness (Figure 4) (Engelstatter et al 2004). Another pooled analysis among 7732 patients with asthma concluded that ciclesonide and placebo recipients experienced similar incidences of adverse events (Hafner et al 2004).

Figure 4.

Occurrence of oropharyngeal adverse events with ciclesonide. Derived from a pooled analysis of the number of oral adverse events per patient year (adjusted for exposure time) in a total of 6846 patients with asthma who received placebo, ciclesonide, or active comparator (budesonide, beclomethasone dipropionate, or fluticasone propionate) in phase II and III studies (Engelstatter et al 2004). This subanalysis of 2755 patients who received placebo (n = 388), ciclesonide 80–640 μg/day (n = 1621), or fluticasone propionate 176 or 880 μg/day (n = 746) for 12 weeks showed that the incidence of oral adverse events associated with ciclesonide 640 μg/day (n = 465) was lower than with fluticasone 880 μg/day (n = 483) (Engelstatter R, Banerji D, Stenijans VW. 2004. Low incidence of oropharyngeal adverse events in asthma patients treated with ciclesonide: results from a pooled analysis [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 169:A92. Copyright © 2004. Reproduced with permission from AJRCCM).

The long-term safety profile of once-daily ciclesonide during a 52-week multicenter, open-label extension study in 226 patients was similar to that in the 12-week studies. Overall, 13 patients (5.75%) experienced at least 1 adverse event that was considered possibly related to ciclesonide treatment, including one case each of oral candidiasis and pharyngitis. There were no clinically relevant changes from baseline to study endpoint in HPA function as measured by 24-hour urinary free cortisol levels (corrected for creatinine) and peak serum cortisol concentrations following cosyntropin 1 μg stimulation (Berger et al 2005).

Patient support/disease management programs

Current asthma treatment guidelines incorporate a stepwise approach to therapy, based on asthma severity (BTS & SIGN 2004; GIA 2004). Inhaled corticosteroids are recommended from the second step onwards, where regular controller therapy is required. Poor adherence to ICS is common and is associated with negative outcomes in patients with asthma (Williams et al 2004). Complex treatment regimens are considered to be an important factor underlying patient noncompliance, and once-daily drug regimens have been suggested as a means of improving compliance with ICS, and hence the outcomes of treatment, for patients with asthma (Campbell 1999). The ciclesonide efficacy and safety results show that it can be recommended for stepwise asthma therapy when ICS are required. Once-daily administration (morning or evening) offers greater patient acceptability than other twice-daily ICS. The low systemic availability and high protein binding of ciclesonide (Rohatagi et al 2005) are features that may explain the low incidence of adverse events. Figure 5 provides a clinical summary of ciclesonide based on its pharmacological properties and clinical trial results.

Figure 5.

Clinical summary of ciclesonide in asthma. All features and comments are derived from referenced information in the text.

Abbreviations: des-CIC, desisobutyryl-ciclesonide; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; PEF, peak expiratory flow.

Conclusion

Ciclesonide has good efficacy equivalent at least to that of the most widely used ICS medications for the treatment of asthma: budesonide and fluticasone. Ciclesonide has a favorable pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile, with potential for reduced local and systemic adverse effects compared with other ICS. In clinical trials, it had oropharyngeal effects that were similar to placebo, and did not suppress cortisol production. Initial results from long-term, open studies are promising, and future trials, including outcomes data, will enable the role of ciclesonide in asthma management to be further defined.

In clinical practice, the once-daily dosing regimen of ciclesonide should aid patient compliance, which could potentially improve outcomes and QoL for adults and children with asthma. Overall, ciclesonide offers an efficacious alternative to ICS for persistent asthma, with a convenient dosing regimen and the potential for reduced systemic adverse effects.

References

- Agertoft L, Pedersen S. Short-term lower-leg growth rate and urine cortisol excretion in children treated with ciclesonide. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:940–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi MG, Bundschuh D, Stoeck M, et al. Preclinical profile of ciclesonide, a novel corticosteroid for the treatment of asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:568–74. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.085217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger W, Galant S, Kundu S, et al. Long term safety profile of once-daily ciclesonide in adults/adolescents with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma [abstract]. 61st Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Imxmunology; March 18–22 2005; San Antonio, TX, USA. 2005. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Berger WE, Mansfield L, Pinter C, et al. Ciclesonide is well tolerated and has minimal oropharyngeal side effects at once-daily doses of 80μg, 160μg, and 320μg in the treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(Suppl):50A. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein D, Nathan R, Ledford D, et al. Ciclesonide, a new inhaled corticosteroid, significantly improves asthma-related quality of life in patients with severe, persistent asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(Suppl)(210):836. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein JA, Noonan MJ, Rim C, et al. Ciclesonide has minimal oropharyngeal side effects in the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(Suppl):349. [Google Scholar]

- Bethke TD, Nave R, Zech K, et al. Pharmacokinetics of ciclesonide and its active principle in asthma patients and healthy subjects after single-dose inhalation [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(Suppl. 2)(217):593. [Google Scholar]

- Boulet LP, Engelstatter R, Magyar P, et al. Ciclesonide is at least as effective as budesonide in the treatment of patients with bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:A771. [Google Scholar]

- British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma: A national clinical guideline [online] 2004 Accessed 12 December 2005 URL: http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- Buhl R, Vinkler I, Magyar P, et al. Once daily ciclesonide and twice daily fluticasone propionate are equally effective in the treatment of patients with asthma [abstract] Eur Resp J. 2004;24(Suppl)(346S):2177. [Google Scholar]

- Busse W, Kaliner M, Bernstein D, et al. The novel inhaled corticosteroid ciclesonide is efficacious and has a favorable safety profile in adults and adolescents with severe persistent asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(Suppl)(213):846. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LM. Once-daily inhaled corticosteroids in mild to moderate asthma: improving acceptance of treatment. Drugs. 1999;58(Suppl 4):25–33. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958004-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KR, Patel P, Boulet LP, et al. Efficacy and long-term safety of ciclesonide in asthmatic patients as demonstrated in a 52 week long study. Eur Respir J. 2002;20(Suppl 38):373–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KR, Patel P, D’Urzo AD, et al. Maintenance of asthma control by once-daily inhaled ciclesonide in adults with persistent asthma. Allergy. 2005;60:330–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derom E, Van De Velde V, Marissens S, et al. Effects of inhaled ciclesonide and fluticasone propionate on cortisol secretion and airway responsiveness to adenosine 5' monophosphate in asthmatic patients. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2005;18:328–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellepola AN, Samaranayake LP. Inhalational and topical steroids, and oral candidosis: a mini review. Oral Dis. 2001;7:211–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelstatter R, Banerji D, Stenijans VW. Low incidence of oropharyngeal adverse events in asthma patients treated with ciclesonide: results from a pooled analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:A92. [Google Scholar]

- Gadgil DA, Niphadkar P, Jagannath KT, et al. Once-daily ciclesonide is as effective as twice-daily budesonide in maintaining lung function and asthma control in patients with asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(Suppl)(3):11. [Google Scholar]

- Gauvreau GM, Watson RM, Postma DS, et al. Effect of ciclesonide 40 μg and 80 μg on early and late asthmatic reaction, and sputum eosinophils after allergen challenge in patients with mild asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:834. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand E, Boguniewicz M, Weinstein S, et al. Ciclesonide, administered once daily, has a low incidence of oropharyngeal adverse events in pediatric asthma patients [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;1151:847. [Google Scholar]

- [GIA] Global Initiative for Asthma. Pocket guide for asthma management and prevention [online] 2004 Accessed 12 December 2005/URL: http://www.ginasthma.com.

- [GIA] Global Initiative for Asthma. Global burden of asthma [online] 2005 Accessed 18 April 2005/URL: http://www.ginasthma.com.

- Gu Z, Howell S, Liu D, et al. In vitro metabolism of 14C-ciclesonide in hepatocytes from mice, rats, rabbits, dogs and humans [abstract] AAPS Journal. 2004;6:W5295. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner D, Kassel G, Wurst W, et al. The incidence of adverse events is comparable in asthma patients receiving ciclesonide or placebo: results from a pooled analysis [abstract] Thorax. 2004;59(ii71):P94. [Google Scholar]

- Hansel T, Biberger C, Engelstatter R. Ciclesonide 80 μg or 320 μg once daily achieves lung function improvement comparable with budesonide 200 μg twice daily in patients with persistent asthma [abstract] Thorax. 2004;59(Suppl 2 ii71):P93. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselgren M, Arne M, Lindahl A, et al. Estimated prevalences of respiratory symptoms, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related to detection rate in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19:54–7. doi: 10.1080/028134301300034701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard R, Tattersfield A. Inhaled corticosteroids, bone mineral density and fracture in older people. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:631–8. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200421100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanniess F, Richter K, Bohme S, et al. Effect of inhaled ciclesonide on airway responsiveness to inhaled AMP, the composition of induced sputum and exhaled nitric oxide in patients with mild asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2001;14:141–7. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2001.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerwin E, Chervinsky P, Fish J. Ciclesonide has no effect on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis at once-daily doses of 80 μg, 160 μg or 320 μg in the treatment of patients with mild-to-moderate asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:A90. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon CG, Adler M, Mehra S, et al. Once-daily ciclesonide 80 or 320 mg for 12 weeks is safe and effective in patients with persistent asthma. Respir Med. 2005;99:1275–85. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BB, Nielsen LP, Engelstatter R, et al. Effect of ciclesonide on allergen challenge in subjects with bronchial asthma. Allergy. 2003;58:207–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DK, Fardon TC, Bates CE, et al. Airway and systemic effects of hydrofluoroalkane formulations of high-dose ciclesonide and fluticasone in moderate persistent asthma. Chest. 2005;127:851–60. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DK, Haggart K, Currie GP, et al. Effects of hydrofluoroalkane formulations of ciclesonide 400 μg once daily vs fluticasone 250 μg twice daily on methacholine hyper-responsiveness in mild-to-moderate persistent asthma. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung SY, Eynott P, Nath P, et al. Effects of ciclesonide and fluticasone propionate on allergen-induced airway inflammation and remodeling features. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:989–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipworth BJ, Kaliner MA, LaForce CF, et al. Effect of ciclesonide and fluticasone on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in adults with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:465–72. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnussen H, Hofman J, Novakova B, et al. Ciclesonide 80 μg or 160 μg once-daily is as effective as fluticasone propionate 88 μg twice-daily in the treatment of persistent asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(Suppl)(4):12. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LE, Harrison C, Tanner RJ. Metabolism of beclomethasone dipropionate by animals and man. Postgrad Med J. 1975;51(Suppl 4):11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Ratner P, Condemi J, et al. Once-daily ciclesonide improves quality of life in pediatric patients with asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:838. [Google Scholar]

- Mollmann H, Derendorf H, Barth J, et al. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic evaluation of systemic effects of flunisolide after inhalation. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37:893–903. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert panel report: guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma update on selected topics – 2002. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:S141–S219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave R, Bethke TD, van Marle SP, et al. Pharmacokinetics of [14C]ciclesonide after oral and intravenous administration to healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004a;43:479–86. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave R, Fisher R, Zech K. In vitro metabolism of ciclesonide in the human lung and liver as determined by use of precision-cut tissue slices. Poster presented at 99th International Conference of the American Thoracic Society; May 16–21 2003; Seattle, WA, USA. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nave R, Meyer W, Fuhst R, et al. Formation of fatty acid conjugates of ciclesonide active metabolite in the rat lung after 4-week inhalation of ciclesonide. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2005a;18:390–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nave R, Schmidt B, Hummel R. Highly lipophilic fatty acid esters of the active metabolite of ciclesonide formed in vitro in rat lung tissue [abstract] Eur Respir J. 2004b;48(345s):2170. [Google Scholar]

- Nave R, Zech K, Bethke TD. Lower oropharyngeal deposition of inhaled ciclesonide via hydrofluoroalkane metered-dose inhaler compared with budesonide via chlorofluorocarbon metered-dose inhaler in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005b;61:203–8. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak A, Charous BL, Finn A, et al. A novel inhaled corticosteroid ciclesonide significantly improves quality of life in patients with mild-to-moderate asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:837. [Google Scholar]

- Newman S, Salmon A, Nave R. High lung deposition of 99mTc-labelled ciclesonide administered via HFA-MDI to asthma patients [abstract] Eur Respir J. 2004;48(583s):3581. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor BJ, Sips P, Engelstatter R, et al. Management of moderate to severe bronchial asthma by ciclesonide: a 12 week trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(8 Pt 2):A767. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor BJ, Kilfeather S, Cheung D, et al. Treatment of moderate to severe asthma with ciclesonide: a long term investigation over 52 weeks [abstract] Eur Respir J. 2002;20(Suppl. 38)(406s):2579. [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels RA, Pedersen S, Busse WW, et al. Early intervention with budesonide in mild persistent asthma: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2003;361:1071–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12891-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman D, Creticos P, Lampl K, et al. Once-daily ciclesonide is effective and well-tolerated in adult and adolescent patients with mild-to-moderate asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:845. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Garcia Garcia ML, Manjra AJ. Ciclesonide and fluticasone propionate show comparable efficacy in children and adolescents with asthma [abstract] Eur Respir J. 2004a;48(346s):2176. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Gyurkovits K, von Delft KHE. Safety profile of ciclesonide as compared with fluticasone propionate in the treatment of children and adolescents with asthma [abstract] Eur Respir J. 2004b;48(346s):2175. [Google Scholar]

- Pfister M, Krishnaswami S, Rohatagi S. Characterization of cortisol circadian rhythm and lack of cortisol suppression by a new corticosteroid, ciclesonide [abstract]. Proceedings of the 13th meeting of the Population Approach Group in Europe Uppsala; June 17–18 2004; Sweden. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Postma DS, Sevette C, Martinat Y, et al. Treatment of asthma by the inhaled corticosteroid ciclesonide given either in the morning or evening. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:1083–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00099701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Kanniess F, Biberger C, et al. Comparison of the oropharyngeal deposition of inhaled ciclesonide and fluticasone propionate in patients with asthma. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:146–52. doi: 10.1177/0091270004271094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatagi S, Appajosyula S, Derendorf H, et al. Risk-benefit value of inhaled glucocorticoids: a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic perspective. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:37–47. doi: 10.1177/0091270003260334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatagi S, Arya V, Zech K, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ciclesonide. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003a;43:365–78. doi: 10.1177/0091270002250998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatagi S, Bye A, Falcoz C, et al. Dynamic modeling of cortisol reduction after inhaled administration of fluticasone propionate. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:938–41. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatagi S, Derandorf H, Zech K, et al. PK/PD of inhaled corticosteroids: the risk/benefit of inhaled ciclesonide [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003b;111(2 Suppl)(S218):598. [Google Scholar]

- Rohatagi S, Luo Y, Shen L, et al. Protein binding and its potential for eliciting minimal systemic side effects with a novel inhaled corticosteroid, ciclesonide. Am J Ther. 2005;12:201–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryrfeldt A, Andersson P, Edsbacker S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of budesonide, a selective glucocorticoid. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1982;122:86–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatoni A, Piantanida E, Nosetti L, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in childhood asthma: long-term effects on growth and adrenocortical function. Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5:351–61. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200305060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpero L, Petecchia L, Silvestri M. In vitro modulation of the cytokine-induced human bronchial epithelial cell (HBEC) functions by ciclesonide (CIC) [abstract] Eur Respir J. 2004;24(Suppl)(48):346s:2173. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro G, Bensch GRL, et al. Once-daily treatment with ciclesonide is effective and well tolerated in children with persistent asthma [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(S6):20. [Google Scholar]

- Spallarossa D, Battistini E, Silvestri M, et al. Steroid-naive adolescents with mild intermittent allergic asthma have airway hyperresponsiveness and elevated exhaled nitric oxide levels. J Asthma. 2003;40:301–10. doi: 10.1081/jas-120018629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeck M, Riedel R, Hochhaus G, et al. In vitro and in vivo antiinflammatory activity of the new glucocorticoid ciclesonide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:249–58. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao PJ, Duong M, Otis J, et al. Ciclesonide is effective in protecting against exercise-induced bronchoconstriction [abstract] J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:3. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DA, Jensen MW, Kanabar V, et al. A dose-dependent effect of the novel inhaled corticosteroid ciclesonide on airway responsiveness to adenosine-5'-monophosphate in asthmatic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:237–43. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9809046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukena D, Biberger C, von Behren V, et al. Ciclesonide significantly improves pulmonary function when compared with budesonide: a randomized 12-week study [abstract] Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;22(S45):P2640. [Google Scholar]

- Weinbrenner A, Huneke D, Zschiesche M, et al. Circadian rhythm of serum cortisol after repeated inhalation of the new topical steroid ciclesonide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2160–3. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams LK, Pladevall M, Xi H, et al. Relationship between adherence to inhaled corticosteroids and poor outcomes among adults with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1288–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]