The word Chlamydia is derived from the Greek meaning cloak-like mantle. The term was coined based on the incorrect conclusion that Chlamydia are intracellular protozoan pathogens that appear to cloak the nucleus of infected cells. Thus, this genus designation is symbolic of the difficulties encountered in discovering the true nature of these important pathogens. It is now known that the chlamydiae are actually prokaryotic organisms, and what was originally thought to be the hooded cloak is in fact a cytoplasmic vesicle containing numerous individual organisms and is termed an inclusion (1). There has been a great deal of interest and effort devoted to understanding more about chlamydiae because it is clear that Chlamydia trachomatis infections continue to be a problem both in the developing world, as a leading cause of preventable blindness (trachoma), and in industrialized countries, as a major sexually transmitted disease (STD) pathogen and significant cause of pelvic inflammatory disease and tubal factor infertility in women (2). The association of genital infections by C. trachomatis with increased risk for cervical cancer and HIV transmission reinforces the need to gain deeper appreciation of the means and mode of chlamydial pathogenesis (3). The more recent recognition of Chlamydia pneumoniae as an important community-acquired respiratory pathogen and its association with common chronic afflictions such as asthma and cardiovascular disease provide additional documentation of the importance for improved understanding of the pathogenic potential for these organisms (4). Lack of a gene transfer system for chlamydiae has hampered definitive pathogenesis investigations for these organisms. Most studies have used traditional cell biology and biochemical approaches, often coupled with microscopic or ultrastructural observations for visual validation of the results (5). Studies of this kind have provided useful insights on chlamydial growth and development, mechanisms of pathogenesis, and generation of immune responses, but, in general, work on chlamydiae has been hindered by the more descriptive restrictions imposed by the limitations in available technology. Reverse genetics has occasionally yielded functional confirmation for a few chlamydial gene products, but these types of studies depend on producing, cloning, and expressing a chlamydial gene or set of genes in a heterologous system, relying on sufficient similarity between the chlamydial gene and the heterologous organism to permit complementation for appropriate mutants (6). When reverse genetic studies work, the results can be gratifying, but relying on this strategy imposes severe restrictions in the actual amount of useful data that can be gleaned, and they necessarily deal with one or only a few chlamydial genes at a time.

Transcriptional profiling can be used to determine events resulting in production of infectious bacteria.

Fortunately, chlamydiae do offer a few experimental advantages. They have small genomes (≈1 Mb) and therefore are easily sequenced. At least six complete genome sequences are available for three of the chlamydial species (7–9), and more sequences are planned and are being produced by a variety of interested research groups. Annotation, analysis, and comparison of chlamydial genomes have provided a few surprises (e.g., they have the genes required for production of peptidoglycan, but no peptidoglycan is present in the fully infectious form of the organism) and some important insights into possible pathogenic mechanisms (10). One key clue for understanding chlamydial pathogenesis is that they have the genes needed for assembling a type III (pathogen to host) secretion apparatus. This is an important finding because in other pathogens this mechanism is used for the direct injection of pathogen proteins into the cytoplasm of host cells (11). This results in changes in the host cell physiology that contributes in manifold ways to pathogen survival or host pathology. The specific mechanisms elicited depend largely on the nature of the effectors injected (12, 13) but often involve modulation of signal transduction pathways (e.g., proor antiapoptotic events, inflammatory activity, immune response capacity), motility, or trafficking (14, 15). Genome sequences for chlamydiae have also demonstrated how phylogenetically remote this organism is from other life forms (16), and has provided the necessary information for construction of genome transcript maps that will be essential for truly understanding the steps that are necessary for successful intracellular chlamydial growth and development, and how these activities relate to the pathogenesis of chlamydial disease. In this issue of PNAS, Belland et al. (17) have provided a well controlled study of how genomic transcriptional profiling of C. trachomatis can be used to gain definitive insight of developmentally regulated events that are necessary for successful completion of the intracellular growth stages that result in the production of infectious progeny.

The work of Belland et al. (17) has also provided important new insights into the interrelationships between chlamydiae and the eukaryotic host. Belland et al. (17) provide excellent rationale for defining immediate early, early, midcycle, and late gene transcription patterns. They insightfully reason that early and late transcription patterns are likely to provide key information on developmentally regulated processes. They then focus their attention on one very early transcript that shares sequence similarities with a eukaryotic gene that produces a protein involved in vesicular trafficking. This type of information not only provides clues regarding mechanisms whereby the chlamydiae may inhibit lysosome fusion, and thus promote their intracellular survival and virulence, but also suggests that a subset of chlamydial genes are in some way related to eukaryotic homologues.

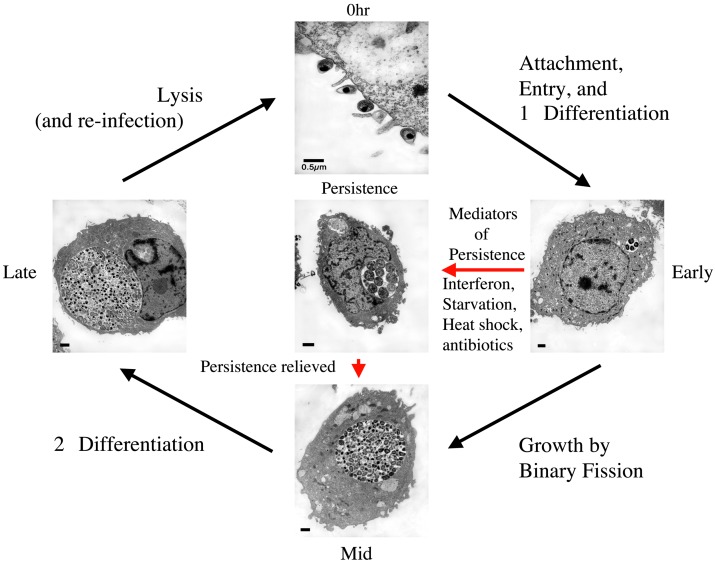

There are not many other experimental advantages associated with research on chlamydiae. Not only are there no methods for stably introducing DNA into this organism, but also they are difficult to grow and manipulate in the laboratory. Based on the work of Belland et al. (17) and a recent gene profiling paper on the lymphogranuloma venereum biovar of C. trachomatis (18), it appears that these organisms may be extremely well suited to transcriptional profiling investigations. Their cycle of intracellular development is linear and, at least during early and late phases, is reasonably synchronized. The cycle conveniently starts with a well characterized developmental form that is not metabolically active and is very stable. Thus, transcriptional activity actually has a legitimate beginning and end. It begins with infection of the host cell with the metabolically inert elementary body (EB) and ends with the differentiation of active metabolic forms back to the metabolically inert EB (see also Fig. 1). There are numerous descriptive, biochemical, microscopic, and ultrastructural characterizations of this process, and Belland et al. (17) have set the stage and provided the methods for additional definitive work in defining the molecular events necessary for successful progression through the developmental cycle as well as other, less well characterized growth options, such as persistence (Fig. 1). It is clear from the transcript patterns reported (17) that microarray analysis confirmed by real-time RT-PCR have provided reliable data, validated by other methods, of identifying a few key early and late gene expression patterns.

Fig. 1.

The chlamydial developmental cycle is unique, allows for both productive and chronic infection cycles, involves production of developmentally regulated gene products, and is intimately connected to the pathogenesis of infectious diseases caused by these organisms.

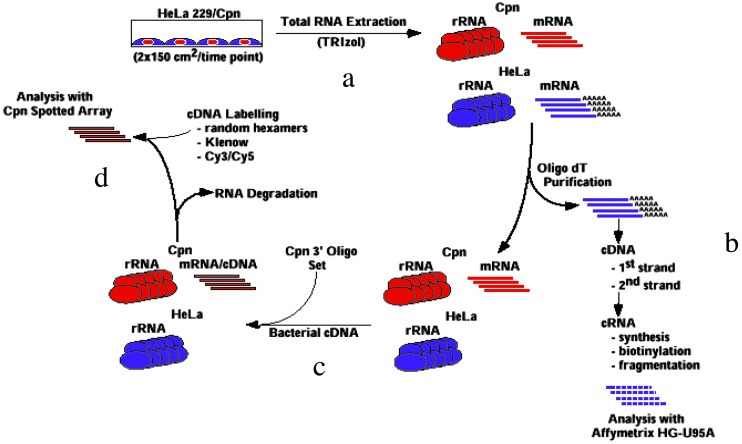

Significantly, microarray analysis of C. trachomatis does not seem to be plagued by mRNA stability issues that have hampered gene profiling studies in other prokaryotic pathogens (19). It is not clear whether this is caused by the particular methods used by Belland et al. (17) or to an inherent property of chlamydiae. However, it is apparent, based on empiric trials, that it is probably best to begin by isolating total RNA from infected host cells rather than beginning by purifying chlamydial organisms from host cell lysates, although Nicholson et al. (18) were successful using the latter method. It is also probably important to use specific chlamydial primers for first-strand cDNA synthesis, because Belland et al. (17) found that inconsistent results were obtained if random primers were initially used. Once single-stranded chlamydial cDNA is produced, total RNA can be removed and random primers can be introduced to produce labeled duplex cDNA for probes in the actual assay. These methods are outlined in Fig. 2. Another key methodological feature of the Belland et al. (17) paper is the use of a standard amount of genomic DNA for cohybridization on the array. This method allows for valid comparisons among all time points and provides a means for reporting data as transcript number per genome. An alternative method would involve cohybridizing samples with one of the time points tested in the assay (18). A final important methodological consideration is selection of the data management package used to display the profiling information. It would appear that, at least for organisms with small genomes such as chlamydiae, the GENESPRING layout chosen by Belland et al. (17) is useful and allows presentation of the data in a manner that is easily diagrammed and provides informative data representations.

Fig. 2.

An RNA purification scheme for microarray analysis is shown. Methods for preparing chlamydial cDNA for microarray analysis are critical for reproducibility. Four key steps were used by Belland et al. (17) to ensure that quality chlamydial RNA preparations were produced that yielded highly reliable cDNA for microarray analysis. (a) RNA was extracted directly from infected host cells without additional manipulations. (b) Host message was separated and can be used for simultaneous profiling studies. (c) Single-stranded chlamydial cDNA was produced by using primers specific for each chlamydial ORF. (d) After synthesis of chlamydial RNA/cDNA products, RNA can be removed by using alkali and labeled random primers can be added to produce probes for the microarray. Comparisons are made by using standard amounts of chlamydial genomic DNA to facilitate accurate analysis of transcripts collected at different time points.

Chlamydiae remain important human pathogens due in part to the wide repertoire of important diseases that they cause. Their continued prominence reflects an inability to properly manage chlamydial infections because of our poor understanding of the basis for their pathogenesis. The use of microarray analysis has provided a means for establishing a deeper understanding of mechanistic elements involved in the chlamydial intracellular growth cycle. These pathogens, refractive to most experimental approaches, may be ideally suited for these types of studies. The use of gene profiling methods, coupled with quantitative assessment of transcriptional activity and proteomic evaluations (20), are providing the tools that will enable us to learn more about how to identify, treat, and prevent chlamydial infections. The work by Belland et al. (17) is an important first step in learning more about chlamydiae. Continued application of these types of analyses will enable us to understand how this organism has been so successful. The chlamydiae may be uncloaked at last.

Acknowledgments

Work in G.I.B.'s laboratory is supported by Public Health Service Grants AI 19782, AI 42790, AI 54875, and HL 71735.

See companion article on page 8478.

References

- 1.Moulder, J. W. (1991) Microbiol. Rev. 55 143-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stamm, W. E. (1999) J. Infect. Dis. 179 (Suppl. 2), S380-S383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesson, H. W. & Pinkerton, S. D. (2000) J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 24 48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalayoglu, M. V., Libby, P. & Byrne, G. I. (2002) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 288 2724-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scidmore, M. A., Fischer, E. R. & Hackstadt, T. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 134 363-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subtil, A., Parsot, C. & Dautry-Varsat, A. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 39 792-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stephens, R. S., Kalman, S., Lammel, C., Fan, J., Marathe, R., Aravind, L., Mitchel, W., Olinger, L., Tatusov, R. L., Zhao, Q., et al. (1998) Science 282 754-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Read, T. D., Brunham, R. C., Shen, C., Gill, S. R., Heidelbeerg, J. F., White, O., Hickey, E. K., Peterson, J., Utterback, T., Berry, K., et al. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28 1397-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirai, M., Hirakawa, H., Kimoto, M., Tabuchi, M., Kishi, F., Ouchi, K., Shiba, T., Ishii, K., Hattori, M., Kuhara, S. & Nakazawa, T. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28 2311-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatch, T. P. (1998) Science 282 638-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buttner, D. & Bnas, U. (2002) Trends Microbiol. 10 186-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Persson, C., Nordfelth, R., Anderson K., Forsberg, A., Wolf-Watz, H. & Fallman, M. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 33 828-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page, A. L., Ohayon, H., Sansonetti, P. J. & Parsot, C. (1999) Cell. Microbiol. 1 183-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhle, V. & Hensel, M. (2002) Cell. Microbiol. 4 813-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Von Pawel-Rammingen, U., Telepnev, M. V., Schmidt, G., Aktories, K., Wolf-Watz, H. & Rosqvist, R. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 36 737-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanner, M. A., Harris, J. K. & Pace, N. R. (1999) in Chlamydia: Intracellular Biology, Pathogenesis & Immunity, ed. Stephens, R. S. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), pp. 1-8.

- 17.Belland, R. J., Zhong, G., Crane, D. D., Hogan, D., Sturdevant, D., Sharma, J., Beatty, W. L. & Caldwell, H. D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 8478-8483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson, T. L., Olinger, L., Chong, K., Schoolnik, G. & Stephens, R. S. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185 3179-3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arfin, S. M., Long, A. D., Ito, E. T., Tolleri, L., Riehle, M. M., Paegle, E. S. & Hatfield, G. W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 29672-29684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandahl, B. B., Birkelund, S., Demol, H., Hoorelbeke, B., Christiansen, G., Vandekerckhove, J. & Gevaert, K. (2001) Electrophoresis 22 1204-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]