Abstract

Pirellula sp. strain 1 (“Rhodopirellula baltica”) is a marine representative of the globally distributed and environmentally important bacterial order Planctomycetales. Here we report the complete genome sequence of a member of this independent phylum. With 7.145 megabases, Pirellula sp. strain 1 has the largest circular bacterial genome sequenced so far. The presence of all genes required for heterolactic acid fermentation, key genes for the interconversion of C1 compounds, and 110 sulfatases were unexpected for this aerobic heterotrophic isolate. Although Pirellula sp. strain 1 has a proteinaceous cell wall, remnants of genes for peptidoglycan synthesis were found. Genes for lipid A biosynthesis and homologues to the flagellar L- and P-ring protein indicate a former Gram-negative type of cell wall. Phylogenetic analysis of all relevant markers clearly affiliates the Planctomycetales to the domain Bacteria as a distinct phylum, but a deepest branching is not supported by our analyses.

Pirellula sp. strain 1, which is in the process of being validly described as `Rhodopirellula baltica,' is a marine, aerobic, heterotrophic representative of the globally distributed and environmentally important bacterial order Planctomycetales. Molecular microbial ecology studies repeatedly provided evidence that planctomycetes are abundant in terrestrial and marine habitats (1–5). For example, they inhabit phytodetrital macroaggregates in marine environments (6) and include one of the organisms known to derive energy from the anaerobic oxidation of ammonia (7). They catalyze important transformations in global carbon and nitrogen cycles. By their mineralization of marine snow particles planctomycetes have a profound impact on global biogeochemistry and climate by affecting exchange processes between the geosphere and atmosphere (8). From a phylogenetic perspective the order Planctomycetales forms an independent, monophyletic phylum of the domain Bacteria (9). It has recently been suggested to be the deepest branching bacterial phylum (10). Planctomycetes are unique in many other respects. Their cell walls do not contain peptidoglycan, the main structural polymer of most members of the domain Bacteria. They show a unique cell compartmentalization in which a single membrane separates a peripheral ribosome-free paryphoplasm from the inner riboplasm (pirellulosome). Within the riboplasm, all planctomycetes contain a condensed fibrillar nucleoid, which in Gemmata spp. is surrounded by a additional double membrane (11). These structures, together with an unusual fatty acid composition of the phospholipids, resemble eukaryotes rather than a representative of the bacterial domain (12).

Characteristic for Planctomycetales are the polar cell organization and a life cycle with a polar, yeast-like cell division. Cells attach to surfaces at their vegetative poles by means of an excreted holdfast substance or stalks (13). Further unusual features are the crateriform structures on the cell surface of all planctomycetes (14). They appear as electron-dense circular regions at the reproductive cell pole (Pirellula spp.) or on the whole cell surface (Planctomyces spp.) (15).

Currently, none of the members of this fascinating group have been investigated by a genomic approach. Here we report the complete, closed genome of Pirellula sp. strain 1, a Baltic Sea isolate from the Kiel Fjord (16).

Methods

Sequencing Strategy. Genome sequencing was performed by a combination of a clone-based and a whole-genome shotgun approach. Two plasmid libraries with 1.5- and 3.5-kb inserts and a cosmid library (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, WI) were built from Pirellula sp. strain 1 DNA. End sequences of inserts were determined by using Big Dye chemistry (ABI), M13 primers, and ABI 3,700 capillary sequencers (ABI) up to eightfold sequence coverage. All raw sequences were processed by phred (17) and controlled for vector or Escherichia coli contamination. Reads were assembled by phrap and manually finished by using gap4 (18). The quality of the sequence data was finished to reach a maximum of 1 error within 10,000 bases. Gap closure and finishing of the sequence were done by resequencing clones, primer-walking, and long-range PCR. Locations and sequence of repetitive sequence elements were additionally controlled by PCR.

Open Reading Frame (ORF) Prediction. Three different programs were used for ORF prediction, glimmer (19), critica (20), and orpheus (21). A nonredundant list of ORFs was generated by parsing the results with a self-written Perl-script. The script applied performs in the following way: For all ORFs that are predicted identically by all three gene finders, only one is kept. If the script recognizes identical stop positions but different starts and the difference is below 10% of the sequence length, only the longer ORF is kept. If the difference is more than 10%, both ORFs are kept.

Annotation. The software package pedant PRO (22) was used for annotation. All automatically generated results were evaluated manually for final annotation. Obviously overpredicted ORFs, e.g., overlapping ORFs without functional assignment, were marked for deletion and deleted after cross-checking by at least two independent annotators.

Data Analysis. For origin and terminus determination a combination of compositional indexes and oligomer distribution skew was used. The following compositional indexes were determined with self-written Perl-scripts: (i) cumulative GC skew [sum of (G - C)/(G + C) over adjacent windows of 10 kb]; (ii) keto excess [sum(GT) - sum(AC)]; (iii) purine excess [sum(AG) - sum(TC)] and the external program oligoskew8 (www.tigr.org/∼salzberg/oligoskew8). Repeats were detected by the software reputer (23). DNA flexibility such as curvature and bending was calculated with the banana program, and sequence twist was calculated with the program btwisted, both taken from the EMBOSS package (www.hgmp.mrc.ac.uk/Software/EMBOSS). Codon usage (codon adaptation index, CAI) was calculated with the codonw-program (www.molbiol.ox.ac.uk/cu). Highly expressed and alien genes according to Karlin and Mrazek (24) were identified with self-written Perl-scripts. For the phylogenetic distribution of the best blast hits the seals package and the taxonomy of the National Center for Biotechnology Information was used. Tat signals were found by extracting all proteins containing twin arginines plus two additional amino acids of the conserved Tat pattern (SRRXFLK).

For whole-genome visualization the software tool genewiz (25) was used. Total gene numbers were calculated by searches against all publicly available genomes with Pfam profiles (http://pfam.wustl.edu) by using gendb 1.1 (46). For phylogenetic reconstructions the preliminary sequence of Gemmata obscuriglobus UQM_2246 was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research (www.tigr.org). The program package ARB was used for phylogenetic analysis (www.arb-home.de).

Supporting Information. All supporting information (Appendices 1–8) is available on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. The complete annotation data and all supporting information are available on the home page of the REGX Project, www.regx.de. For fast searching a blast server is available for public use.

Results and Discussion

Genome Organization. With a size of 7,145,576 bases, Pirellula sp. strain 1 has the largest prokaryotic circular genome sequenced so far. Origin and terminus could be clearly identified by the change in cumulative GC and AT skews (Fig. 1). A single, unlinked rRNA operon was identified near the origin. Unlinked rrn operons have also been described for other planctomycetes (13) but the 460 kb separating the 16S from the 23S–5S rRNA genes in Pirellula sp. strain 1 are exceptional. A nonrandom distribution of the 81 transposases and the 13 integrases/recombinases was found: 68% (55) of all transposases and 85% (11) of all integrases/recombinases are located in the region between 0 and 3.6 megabases of the genome. General features of the genomic sequence are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Structural representation of the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome. Circle 1 (from the outside in), GC skew; circle 2, G+C content; circle 3, G+A content; circle 4, DNA curvature; circle 5, DNA bending; circle 6, DNA stacking energy; circle 7, codon adaptation index (CAI). The origin of replication (ORI) and the terminus (TER) are indicated. A and B indicate minor irregularities. Ochre, pink, and red represent high values; blue, light blue, and green show low values.

Table 1. General features of the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome.

| Component of chromosome | Property |

|---|---|

| Total size, bases | 7,145,576 |

| G+C content, % | 55.4 |

| Coding sequences | 7,325 |

| Coding density, % | 95 |

| Average gene length, bases | 939 |

| Genes with similarities in databases* | 3,380 (46%) |

| Genes with functional assignments | 2,582 (35%) |

| rRNAs | 1× (16S) and (23S-5S) |

| tRNAs | 70 |

| Other stable RNAs | 1 (ribozyme) |

Threshold for BLASTP E value ≤1 × 10-3, includes hits to hypothetical proteins

Irregularity. A large inversion at position 87,500 to 431,000 of 343.5 kb is indicated by cumulative GC-skew and other structural parameters (Fig. 1 and Appendix 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Analysis of this anomalous region did not give any indications for lateral gene transfer. On the contrary, a regular codon adaptation index and the localization of housekeeping genes (e.g., several tRNA synthetases, ribosomal proteins, and flagella proteins) in this region indicate that most probably an internal chromosomal inversion has occurred. This conclusion is supported by five and four flanking transposases. Two of them are identical and have reverse orientation. In total, 16% (13) of all transposase genes are located within this region, supporting a hot spot for large genomic rearrangements.

Gene and Functional Prediction. An initial nonredundant list of 13,331 potential ORFs was generated. By manual annotation, this ORF set could be reduced to 7,325 ORFs, which equals a gene coverage of 95%. A blastx of all intergenic regions confirmed that a comprehensive ORF set was achieved. More than half (56%, 4,148) of the predicted ORFs showed only weak or no similarities (E values higher than 0.9) compared with the currently available sequence databases. Only 32% (2,384) of all ORFs had reliable functional predictions, which is about 20% less than the numbers found in general (26). This low percentage reflects the distinct phylogenetic position and the lack of molecular studies performed on Planctomycetales so far. An overview of the localization of the functional genes according to our functional classification (27) is given in Fig. 2. The complete annotation results are available at www.regx.de.

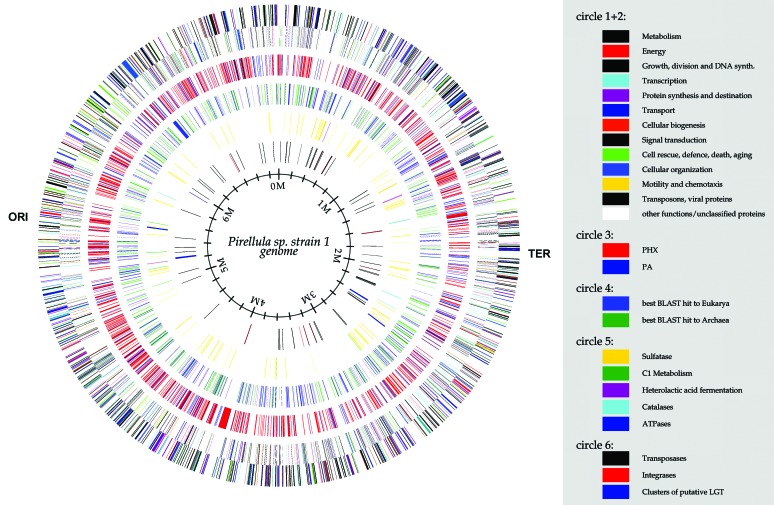

Fig. 2.

Circular representation of the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome. Circles 1 and 2 (from the outside in), all genes (reverse and forward strand, respectively) color-coded by function; circle 3, predicted highly expressed (PHX) and predicted alien (PA) genes; circle 4, potentially eukaryotic or archaeal genes; circle 5, sulfatase, C1-metabolism, heterolactic acid fermentation, catalase, and ATP-synthase genes; and circle 6, transposase, integrase, and clusters of putative laterally acquired genes. The origin of replication (ORI) and the terminus (TER) are indicated.

Genome Size. We found that 1,301 genes (i.e., 17.6% of all genes), with an average length of 464 aa, have more than one copy within the genome. In total, multicopy genes make up for about 25.4% of the genome sequence. This is less than the 30% reported for Bacillus subtilis (28) and the 29% we calculated for E. coli K-12. Therefore extensive gene duplication is not the reason for the large genome size of Pirellula sp. strain 1. A large genome with an expanded genetic capability might be a prerequisite for environmental adaptability, as already discussed for the genome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (29).

Potential Environmental Adaptations. Metabolism. The annotation process identified the standard pathways for heterotrophic bacteria such as glycolysis, the citrate cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation. Pirellula sp. strain 1 lacks the glyoxylate bypass and the Entner–Doudoroff pathway but exhibits the pentose-phosphate cycle. Furthermore, it seems to be capable of synthesizing all amino acids (Appendix 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Recent growth studies did not provide evidence that Pirellula sp. strain 1 can grow under nitrate-reducing or fermentative conditions. Interestingly, however, all genes required for heterolactic acid fermentation are present (Fig. 2 and Appendix 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Expression of the genes is likely, because the key enzyme lactate dehydrogenase has been predicted to be highly expressed on the basis of codon usage. Furthermore, both Pirellula marina and Planctomyces limnophilus have been described to be capable of carbohydrate fermentation (30). This capability could explain why planctomycetes were found in anoxic marine and freshwater sediments and anoxic terrestrial habitats (1–3).

Motility. The life cycle of Pirellula sp. strain 1 consists of an aggregate-forming sessile form and a motile swarmer cell. In the genome all genes for a functional flagellum could be determined, whereas except for cheY, essential genes for chemotaxis such as cheA, cheB, cheR, cheW, and cheZ could not be identified.

Transporters. As a free-living organism, Pirellula sp. strain 1 was expected to have a wide range of transporters (29). A comparative study with Pfam profiles for ABC-transporters against all 70 publicly available prokaryotic genomes revealed that the 55 ABC-transporters found in Pirellula sp. strain 1 is close to the calculated mean of 49 transporters. In comparison with other free-living bacteria this is only about one-third of the 148 ABC-transporters found with the same method in Streptomyces coelicolor A3 (2), but similar to the 45 transporters of Caulobacter crescentus (Appendix 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Annotation revealed that ABC-transporters for ribose, oligopeptides, phosphate, manganese, nitrate, and sodium are present, but only one phosphotransferase system (PTS) specific for fructose could be identified. Exceptional is a set of ORFs for nitrate transport and nitrate/nitrite reduction that were predicted to be highly expressed (PHX) on the basis of codon usage (24). This set of ORFs could be essential in nitrogen-limited marine systems (31).

Stress response. The genome harbors homologues to superoxide dismutase and all four known types of catalases (Fig. 2). Methionine-sulfoxide reductases are present to repair oxidized methionine. By synthesis of a cytochrome d oxidase as an alternative to the regular cytochrome aa3 Pirellula sp. strain 1 should be able to cope with low oxygen concentrations.

Many mechanisms are present to reduce the damaging effect of UV radiation. Besides the genes for SOS response (recA, lexA, uvrA, uvrB, and uvrC), Pirellula sp. strain 1 has a photolyase gene organized in an operon-like manner with genes encoding phytoene dehydrogenase and phytoene synthase. Probably, UV stress triggers the biosynthesis of a UV-protection carotenoid, which might be responsible for the pinkish color of Pirellula sp. strain 1. Regarding temperature stress, Pirellula sp. strain 1 has many homologues to heat and cold shock DNA-binding proteins. Detoxification seems to take place by means of unspecific export systems like cation efflux systems of the AcrB/AcrD/AcrF family or unspecific multidrug export systems for hydrophobic compounds. A cytochrome P450 mono-oxygenase and an epoxide hydrolase are present for the detoxification of xenobiotics. Specific detoxification involves mercury reductase, arsenate reductase, and the ArsA arsenite-exporting ATPase. The harmful effect of d-tyrosine binding to tyrosyl-tRNA is minimized by d-tyrosyl-tRNATyr deacylase. In addition, Pirellula sp. strain 1 has a gene encoding a bacterial hemoglobin, which is believed to detoxify NO by oxidation. Finally, the genome has some homologues to carbon-starvation proteins, including DNA-protection proteins.

Antibiotics. Several ORFs potentially coding for polyketide antibiotics and nonribosomal polypeptide antibiotics or a mixture of both have been determined in the genome of Pirellula sp. strain 1. In general the ORFs are unusually long, coding for proteins from 916 up to 3,665 aa.

Sulfatases. The Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome harbors 110 genes encoding proteins with significant similarity to prokaryotic (82 genes; 75%) and eukaryotic (28 genes; 25%) sulfatases. For instance, similarity was found to alkylsulfatase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, to arylsulfatases of Pseudomonas sp., to mucindesulfating sulfatase of Prevotella sp., and to archaeal arylsulfatase, as well as to mammalian iduronate-2-sulfatase and arylsulfatases A and B. In comparison, the analysis of 70 published prokaryotic genomes with a specific Pfam profile revealed a maximum of only 6 sulfatases found in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 genome. In Pirellula sp. strain 1, the sulfatase genes are distributed across the genome in 22 clusters containing two to five genes (Fig. 2).

In Pirellula sp. strain 1, all detected sulfatase gene products, except for the three alkylsulfatases, are of the cysteine type; 85 (79%) of them show the canonical CXPXR motif and are hence considered as potentially functional (32). In contrast to the known bacterial cysteine-type sulfatases, which are cytosolic enzymes (e.g., arylsulfatase AtsA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa), for 26 (31%) of the 85 potentially functional sulfatases in Pirellula sp. strain 1 a signal peptide is predicted with high probability, suggesting an extracytosolic localization of the proteins.

The fact that the sulfatase genes in Pirellula sp. strain 1 outnumber those present in all other known prokaryotic genomes by two orders of magnitude raises the question about their physiological role. Bacterial sulfatases seem to be primarily used in sulfur scavenging, and their expression is known to be tightly regulated and dependent on the sensing of sulfur deprivation (32). As marine systems are characterized by high inorganic sulfate concentrations, sulfur limitations should not occur. Therefore, Pirellula sp. strain 1 might use its sulfatases to access more effectively the carbon skeleton of sulfated compounds as an energy source rather than to meet its sulfate requirements. Cleavage of sulfate esters in sulfated high molecular weight glycoproteins (mucins) to increase the efficiency of polymer degradation by other enzymes has been described for Prevotella sp. RS2. Seven of the 110 sulfatase genes in Pirellula sp. strain 1 encode proteins with high similarity to mucindesulfating sulfatase of Prevotela sp. RS2, an enzyme that seems to be specific for the cleavage of sulfate from N-acetylglucosamine 6-sulfate in mucin side chains (33). Remarkably, one of the seven genes in Pirellula sp. strain 1 is located next to a gene encoding a protein with some similarity to N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase, a protein involved in metabolism of N-acetylglucosamine. This compound is known to support growth of Pirellula sp. strain 1 as a sole source of nitrogen and organic carbon.

Furthermore, 17 (20%) of the potentially functional Pirellula sp. strain 1 sulfatase gene products exhibit similarity to proteins hydrolyzing sulfate ester bonds of sugar units in heteropolysaccharides. Interestingly, chondroitin sulfate is an excellent growth substrate for Pirellula sp. strain 1 (H.S., unpublished results).

In addition, 25 (29%) of the 85 genes coding for potentially functional sulfatases in Pirellula sp. strain 1 are found in a genomic context of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, e.g., carrageenase and other glycosyl hydrolases. For 3 of these 25 sulfatases as well as for an additional 4 potentially functional sulfatases a high expression level is predicted (PHX).

These data suggest that sulfatases are metabolically important in Pirellula sp. strain 1 and could play a role in the efficient degradation of sulfated glycopolymers. Such compounds (e.g., carrageen) are abundant in marine environments in the form of phytodetrital macroaggregates (“marine snow”), and planctomycetes have been shown to be components of the microbial communities on such aggregates (6).

C1 metabolism. Another intriguing feature derived form the genome sequence is the genetic potential for degrading C1 compounds (Fig. 2). Although Pirellula sp. strain 1 is not capable of utilizing methanol, methylamine, or methylsulfonate, and genes encoding enzymatic activities for the primary oxidation steps of such C1 compounds could not be identified in the genome, functional prediction revealed all enzymes necessary for the oxidation of formaldehyde to formate. The predicted pathway in Pirellula sp. strain 1 (M.B., unpublished results) resembles very closely a pathway of formaldehyde oxidation/detoxification in methylotrophic proteobacteria. These tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT)-dependent enzymes were previously thought to be unique for anaerobic methanogenic and sulfate-reducing Archaea. Recently, however, they have been shown to play an essential physiological role in methylotrophic proteobacteria (34). Pirellula sp. strain 1 is, to our knowledge, the first bacterial organism outside the proteobacterial division found to contain genes encoding H4MPT-dependent enzymes. In context with the fact that planctomycetes constitute an independent phylum, our finding revives the discussion on the evolutionary processes leading to the distribution of these archaeal genes.

Cell Biology. Cell wall. Planctomycetes are the only group of free-living members of the domain Bacteria known so far that have no peptidoglycan in their cell walls. Instead, they are stabilized by a protein sacculus with disulfide bonds (35). A systematic investigation for genes involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis revealed that murB, murE, murG, ddlA, and upk (bacA) are present. Furthermore, Pirellula sp. strain 1 possesses the gene glmS, which is involved in the formation of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, a precursor for peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Other key enzymes, such as MurA, MurC, MurD, MurF, and DdaA for the final cross-linking of peptidoglycan, are notably absent from the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome. The preservation of at least some of the genes of the peptidoglycan synthesis pathway suggests that Pirellula sp. strain 1 is not a descendant from a bacterium evolving before the invention of peptidoglycan, as proposed earlier (36). It rather seems that after the development of a proteinaceous cell envelope in planctomycetes, genes for peptidoglycan biosynthesis were successively lost.

Membrane. It is noteworthy that the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome harbors all genes required for biosynthesis of lipid A, the major constituent of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) layer in Gram-negative bacteria. The presence of these genes is in line with earlier reports of presence of lipid A with unusual portions of long-chain 3-OH fatty acids in members of the Pirellula/Planctomyces group (12). Nevertheless, the key enzymes necessary for the biosynthesis of an O-specific side chain (O-antigen ligase; O-antigen polymerase) are absent from the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome. The presence of lipid A and homologues to the flagellar L- and P-ring protein suggests that the cell envelope of planctomycetes was converted from a Gram-negative type of cell wall. Furthermore, Pirellula sp. strain 1 lacks the signature sequences in the ribosomal protein S12 and SecF typical for low and high G+C Gram-positive bacteria, respectively (37).

Compartmentalization. One of the most striking properties of the Planctomycetales is their complex internal structures (11). Ribosomes are located only within the riboplasm, therefore proteins targeted to the paryphoplasm have to overcome the intracytoplasmic membrane. This requires effective protein targeting. A comparative search with Pfam profiles against all publicly available prokaryotic genomes revealed that Pirellula sp. strain 1 has the highest number of hits to secA (3), the general secretory pathway (GSP) type II F-domain (6), and the GSP type II/III secretion system protein (9). Furthermore Pirellula sp. strain 1 has 1,271 genes with predicted signal peptides. In comparison with all other genomes investigated this number is matched only by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 (1,277). When normalized on genome size, Pirellula sp. strain 1 comprises 178 signal peptides per megabase, which is again at the high end. An equally high proportion of proteins with signal peptides was also found in another “life cycle” bacterium, C. crescentus, which has 182 signal peptides per megabase (Appendix 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). A comparison for Tat (twin arginine translocation) signal peptides showed that Pirellula sp. strain 1 has the highest number of all genomes investigated (135; 18.9 per megabase). Effective protein targeting might be the basis for the polar organization of Pirellula sp. strain 1 and for distinct features (e.g., stalks, holdfast substance, crateriform structures) present only in certain regions of the cells.

Cell division. Cell division involves a plethora of genes. The most important are ftsZ, ftsA, ftsI, ftsL, ftsQ, ftsN, zipA, and ftsW (38). Surprisingly, with the exception of ftsK, all genes are absent from the genome of Pirellula sp. strain 1. A lack of the key enzyme FtsZ, the major constituent of the septal replication ring, has so far been reported only for chlamydiae, the Crenarchaeota, and Ureaplasma urealyticum (38). Not much is known about replication in planctomycetes, especially how the cell compartments are distributed to the daughter cells. Altogether, cell division in Pirellula sp. strain 1 must follow a different pathway than reported for the model organisms E. coli and B. subtilis.

Life cycle. Pirellula sp. strain 1 exhibits a life cycle similar to C. crescentus (39). Surprisingly, no homologue to the master response regulator protein CtrA has been found within the genome of Pirellula sp. strain 1. However, the origin in Pirellula sp. strain 1 contains some patterns similar to the CtrA binding site pattern TTAAN7TTAA upstream of dnaN (e.g., TTAAN7AAAC), which might indicate a similar control mechanism.

Regulation. Analysis of the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome with 116 relevant Pfam 7.2 family models shows only 135 genes with motifs for predicted transcriptional regulators. No evidence for eukaryotic-like transcriptional regulators could be found. There are 68 response regulators, which allow microorganisms to respond to changes in their environment, but common bacterial regulators such as LysR are absent or underrepresented. A comparative analysis in all currently available bacterial genomes was performed. The results confirm earlier findings that the proportion of the genome encoding transcriptional regulators increases with genome size (29, 40) (Appendix 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Nevertheless with a genome size of more than 7 megabases and only 2% predicted regulatory genes, Pirellula sp. strain 1 clearly contradicts this trend. It remains to be determined whether these results reflect a lack of knowledge in the diversity of regulatory proteins or even unknown gene regulation mechanisms. For example, a unique family of predicted DNA-binding proteins has been reported in the genome of S. coelicolor A3(2) (40), which might constitute a family of Streptomyces-specific transcriptional regulators. Regulation of metabolic capacities of Pirellula sp. strain 1 were recently addressed by a proteomic approach, which revealed differential protein patterns in response to carbohydrates used for growth (41).

Sigma factors. Pirellula sp. strain 1 encodes for a total of 51 sigma factors, including 16 ECF (extracytoplasmic function) sigma factors. Currently, with 65 sigma factors, only S. coelicolor has a higher number. Therefore, it seems that in Pirellula sp. strain 1 gene regulation is based to a greater extent on altering the promoter specificity of the RNA polymerase. Further support for this hypothesis comes from the observation that genes for essential pathways such as purine or biotin and amino acid biosynthesis are not organized in operons, as is known for most of the prokaryotes. This scattering, together with the split rRNA operon, requires a different way of regulation.

Evolution. Phylogeny. The currently accepted bacterial systematics based on 16S rRNA assigns the Planctomycetales with the genera Pirellula, Planctomyces, Isosphaera, and Gemmata as an independent monophyletic phylum (9). For evaluation, phylogenetic trees for commonly used alternative markers such as the 23S rRNA, elongation factors Tu and G, ATP-synthase subunits, RecA, heat shock proteins HSP60 and HSP70, RNA polymerase, and DNA gyrase subunits as well as the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases of Pirellula sp. strain 1 were constructed. A common Pirellula–Gemmata (G. obscuriglobus UQM_2246) cluster separated from all other phyla or major subgroups is seen in trees derived from 23S rRNA, elongation factors, ATP-synthase subunits α and β, DNA gyrase subunits A and B, the heat shock proteins HSP60 and HSP70, the recA protein, and most of the tRNA synthetases. Multiple copies are present in the case of ATP-synthase α and β as well as the DNA gyrase A and B subunits. The sequence divergence of the duplicates corresponds to the phylum level. Thus the individual monophyletic Pirellula–Gemmata pairs are separated from other phyla in the respective trees. However, the multiple copies of heat shock proteins HSP60 and HSP70 cluster in common groups with the Pirellula and Gemmata proteins phylogenetically intermixed. Keeping in mind the possible pitfalls and the differences in resolving power when functional genes are used for tree reconstruction (42), the status as an independent phylum affiliated to the domain Bacteria is clearly supported in the majority of analyses. A deepest branching of planctomycetes within the bacterial subtree as reported recently (10) is not convincingly supported by any of the markers, as evaluated by applying different tree-building methods, parameters, and significance tests.

ATP-synthases. Pirellula sp. strain 1 is the only bacterium described so far that contains two FoF1 ATP-synthases (Fig. 2). By gene organization (a, c, b, δ, α, γ, β, ε) and similarity one ATP-synthase resembles the “standard” ATP-synthase that is common in all Bacteria (43). Nevertheless, the J gene found in all Bacteria except for Thermotoga maritima is missing. The second set of FoF1-ATP-synthase genes has a different operon structure with β and ε genes followed by the J, X, a, c, and b genes and the α, γ genes (Appendix 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The strong conservation and the high similarity of this ATP-synthase operon to Methanosarcina barkeri indicates a lateral gene transfer event. It remains unclear whether the genes were transferred from the archaeal to the bacterial domain or vice versa.

Phylogenetic Distribution of Best blast Hits. All 7,325 potential proteins (ORFs) in the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome were searched against the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant database. By setting the cut-off for the blastp expectation value ≤1 × 10-3, significant hits could be obtained for 3,380 genes. Of these genes, 83% were assigned to the domain Bacteria, 9% and 8% to the domains Archaea and Eukarya, respectively (Fig. 2). The large number of hits to eukaryotes is exceptional. T. maritima, for example, shows 24% hits to Archaea but only 2% to Eukarya, and in E. coli only 0.4% of the best hits assign to Archaea or Eukarya. Nevertheless, among the 270 genes found in Pirellula sp. strain 1 no trend for a certain organism of origin or a distinct functional category could be detected (Appendix 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Furthermore, the two genes for the integrin α-V and inter-α-trypsin inhibitor found in Pirellula marina and G. obscuriglobus, considered to be typical for Eukarya (44), could not be detected in the Pirellula sp. strain 1 genome.

Relationship to Chlamydia. The phylogenetic analysis of a comprehensive set of markers with different tree-building methods and confidence tests revealed that only the trees for DNA gyrase, RNA polymerase C, and lysyl- and valyl-tRNA synthetase supported a moderate relationship to Chlamydia. Using only distance matrix methods, we also found a remote relationship to Chlamydia in some ribosomal proteins, DnaA, Hsp60, Rho, the protein component of RNase P, and CTP synthase. According to the indel method of Gupta and Griffiths (37), Pirellula sp. strain 1 branches off between spirochetes and Chlamydia.

As already mentioned, Pirellula sp. strain 1 and Chlamydia share some noteworthy features: both lost their peptidoglycan cell walls in favor of a proteinaceous cell envelope. Furthermore, Chlamydia and Pirellula sp. strain 1 have two dnaA copies and lack ftsZ, indicating an unknown mode of cell division. In addition, the ribosomal protein L30 is missing from the spc operon in Chlamydia as well as in Pirellula sp. strain 1. Although the complete genome sequence does not confirm a close relationship of Chlamydia and planctomycetes, it is still possible that an ancient relatedness exists. In this case the extremely different habitats might have blurred the genetic records.

Conclusions. The genome sequence of Pirellula sp. strain 1 has revealed insights into adaptations of free-living marine bacteria. Environmental versatility demands an enhanced genetic complexity harbored by larger genomes (29, 40). In case of Pirellula sp. strain 1 no indication for a recent expansion of the genome could be detected. In contrast, except for some irregularities (Fig. 1), the plot of the cumulative GC-skew of Pirellula sp. strain 1 is very “smooth” with clear maxima and minima (Appendix 1). From the genome features it is now possible to propose a certain lifestyle of Pirellula sp. strain 1. In the water column Pirellula sp. strain 1 gains energy from the aerobic oxidation of mono- or disaccharides derived from the cleavage of sulfated polymers produced by algae. Protection systems for UV and the expression of carotenoids protect Pirellula sp. strain 1 from irradiation at the water surface. Nitrate transporters support growth even under limited-nitrogen conditions common in continental shelf areas. The holdfast substance enables Pirellula sp. strain 1 to attach to nutrient-rich marine snow particles slowly sedimenting to the sea floor. When the bacterium reaches the sediment the expression of cytochrome d oxidase allows survival under low oxygen conditions. Anoxic conditions force Pirellula sp. strain 1 to switch to heterolactic acid fermentation or pathways involving formaldehyde conversion if not to support growth, then at least to allow basic maintenance metabolism. With the expression of genes for carbon starvation Pirellula sp. strain 1 can even outlast periods of nutrient depletion. The formation of swarmer cells helps Pirellula sp. strain 1 to reach for new resources. The high number of sigma factors allows the tight control of gene expression under changing environmental conditions.

Exceptionally interesting will be the genome comparison of Pirellula sp. strain 1 with the freshwater isolate G. obscuriglobus UQM_2246 (45), currently being sequenced by The Institute for Genomic Research, and Gemmata sp. Wa1-1, being sequenced by Integrated Genomics. It will not only reveal common traits of the Planctomycetales but also give hints for the specific adaptations to the different habitats and the origin of the unique combination of morphological and ultrastructural properties.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jörg Wulf for DNA extraction; Sven Klages, Ines Marquardt, Silvia Lehrack, Birol Köysüren, özlem Ogras, and Roman Pawlik for technical assistance; Hauke Pfeffer, Michael Richter, Thomas Otto, Tim Frana, Stella Koufou, Andreas Schmitz, and Jost Waldmann for their expert help in annotation and programming; Folker Meyer and Alexander Goesmann for their continuous support with GenDB; Anke Meyerdierks and Erich Lanka for excellent critical discussions; and Hans Lehrach for his continuous support and critical discussions. Major funding of this project was provided by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Further support came from the Max Planck Society. G. obscuriglobus is being sequenced with support from the U.S. Department of Energy.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. BX119912).

References

- 1.Wang, J., Jenkins, C., Webb, R. I. & Fuerst, J. A. (2002) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68 417-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llobet-Brossa, E., Rossellò-Mora, R. & Amann, R. (1998) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 2691-2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miskin, I., Farrimond, P. & Head, I. (1999) Microbiology 145 1977-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neef, A., Amann, R., Schlesner, H. & Schleifer, K.-H. (1998) Microbiology 144 3257-3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuerst, J. A., Gwilliam, H. G., Lindsay, M., Lichanska, A., Belcher, C., Vickers, J. E. & Hugenholtz, P. (1997) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63 254-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeLong, E. F., Franks, D. G. & Alldredge, A. L. (1993) Limnol. Oceanogr. 38 924-934. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strous, M., Fuerst, J. A., Kramer, E. H. M., Logemann, S., Muyzer, G., van de Pas-Schoonen, K. T., Webb, R., Kuenen, J. G. & Jetten, M. S. M. (1999) Nature 400 446-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alldredge, A. L. (2000) Limnol. Oceanogr. 45 1245-1253. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrity, G. M. & Holt, J. G. (2001) in Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, eds. Boone, D. R. & Castenholz, R. W. (Springer, New York), 2nd Ed., Vol. 1, pp. 119-166. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brochier, C. & Philippe, H. (2002) Nature 417 244-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsay, M. R., Webb, R. I., Strous, M., Jetten, M. S., Butler, M. K., Forde, R. J. & Fuerst, J. A. (2001) Arch. Microbiol. 175 413-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerger, B. D., Mancuso, C. A., Nichols, P. D., White, D. C., Langworthy, T., Sittig, M., Schlesner, H. & Hirsch, P. (1988) Arch. Microbiol. 149 255-260. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuerst, J. A. (1995) Microbiology 141 1493-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt, J. M. & Starr, M. P. (1978) Curr. Microbiol. 1 325-330. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlesner, H. & Hirsch, P. (1984) Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 34 492-495. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlesner, H. (1994) Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 17 135-145. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ewing, B. & Green, P. (1998) Genome Res. 8 186-194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Staden, R., Beal, K. F. & Bonfield, J. K. (2000) Methods Mol. Biol. 132 115-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delcher, A. L., Harmon, D., Kasif, S., White, O. & Salzberg, S. L. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27 4636-4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badger, J. H. & Olsen, G. J. (1999) Mol. Biol. Evol. 16 512-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frishman, D., Mironov, A., Mewes, H. W. & Gelfand, M. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 26 2941-2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frishman, D., Albermann, K., Hani, J., Heumann, K., Metanomski, A., Zollner, A. & Mewes, H. W. (2001) Bioinformatics 17 44-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurtz, S., Choudhuri, J. V., Ohlebusch, E., Schleiermacher, C., Stoye, J. & Giegerich, R. (2001) Nucleic Acids Res. 29 4633-4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlin, S. & Mrazek, J. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182 5238-5250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jensen, L. J., Friis, C. & Ussery, D. W. (1999) Res. Microbiol. 150 773-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraser, C. M., Eisen, J. A. & Salzberg, S. L. (2000) Nature 406 799-803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mewes, H. W., Albermann, K., Bahr, M., Frishman, D., Gleissner, A., Hani, J., Heumann, K., Kleine, K., Maierl, A., Oliver, S. G., et al. (1997) Nature 387 7-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kunst, F., Ogasawara, N., Moszer, I., Albertini, A. M., Alloni, G., Azevedo, V., Bertero, M. G., Bessieres, P., Bolotin, A., Borchert, S., et al. (1997) Nature 390 249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stover, C. K., Pham, X. Q., Erwin, A. L., Mizoguchi, S. D., Warrener, P., Hickey, M. J., Brinkman, F. S. L., Hufnagle, W. O., Kowalik, D. J., Lagrou, M., et al. (2000) Nature 406 959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlesner, H. & Stackebrandt, E. (1986) Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 8 174-176. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agusti, S., Duarte, C. M., Vaque, D., Hein, M., Gasol, J. M. & Vidal, M. (2001) Deep-Sea Res. Part II 48 2295-2321. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kertesz, M. A. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24 135-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright, D. P., Knight, C. G., Parker, S. G., Christie, D. L. & Roberton, A. M. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182 3002-3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chistoserdova, L., Vorholt, J. A., Thauer, R. K. & Lidstrom, M. E. (1998) Science 281 99-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liesack, W., König, H., Schlesner, H. & Hirsch, P. (1986) Arch. Microbiol. 145 361-366. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stackebrandt, E., Ludwig, W., Schubert, W., Klink, F., Schlesner, H., Roggentin, T. & Hirsch, P. (1984) Nature 307 735-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta, R. S. & Griffiths, E. (2002) Theor. Popul. Biol. 61 423-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margolin, W. (2000) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24 531-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marczynski, G. T. & Shapiro, L. (2002) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56 625-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bentley, S. D., Chater, K. F., Cerdeno-Tarraga, A. M., Challis, G. L., Thomson, N. R., James, K. D., Harris, D. E., Quail, M. A., Kieser, H., Harper, D., et al. (2002) Nature 417 141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabus, R., Gade, D., Helbig, R., Bauer, M., Glöckner, F. O., Kube, M., Schlesner, H., Reinhardt, R. & Amann, R. (2002) Proteomics 2 649-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ludwig, W. & Klenk, H. P. (2001) in Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, eds. Boone, D. R. & Castenholz, R. W. (Springer, New York), 2nd Ed., Vol. 1, pp. 49-65. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deckers-Hebestreit, G. & Altendorf, K. (1996) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50 791-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jenkins, C., Kedar, V. & Fuerst, J. (2002) Genome Biol. 3 0031.1-0031.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franzmann, P. D. & Skerman, V. B. D. (1984) Antonie Leeuwenhoek 50 261-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer, F., Goesmann, A., McHardy, A. C., Bartels, D., Bekel, T., Clausen, J., Kalinowski, J., Linke, B., Rupp, O., Giegerich, R., et al. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31 2187-2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.