Abstract

The development and mechanisms of tolerance to allergens are poorly understood. Using the murine low zone tolerance (LZT) model, where contact hypersensitivity (CHS) is prevented by repeated topical low-dose applications of contact allergens, we show that LZT induction is IL-10 dependent. IL-10 is required for the generation of LZT effector cells, that is, CD8+ regulatory T cells. Only T cells from tolerized IL-10+/+ mice or IL-10–/– mice reconstituted with IL-10 during LZT induction adoptively transferred LZT to naive mice and prevented CHS, whereas T cells from IL-10–/– mice failed to do so. The IL-10 required for normal LZT development is derived from lymph node CD4+ T cells, the only skin or lymph node cell population found to produce relevant amounts of IL-10 after tolerization. CD4+ T cells derived from IL-10+/+ mice, but not from IL-10–/– mice, allowed the induction of LZT in adoptively transferred T cell–deficient mice. Interestingly, IL-10 injections during tolerization greatly enhanced LZT responses in normal mice. Thus, the generation of CD8+ LZT effector T cells by CD4+ regulatory T cells via IL-10 may be a promising target of strategies aimed at preventing contact allergies and other harmful immune responses.

Introduction

Allergy prevention by the induction of tolerance has been studied extensively in various animal models and includes oral tolerance, immunosuppression induced by UV irradiation, and low zone tolerance (LZT), in which repeated applications of low doses of contact allergens impede the development of contact hypersensitivity (CHS) (1–3). Because low zone tolerization is achieved by the physiological uptake of very small amounts of allergenic antigens by way of the skin, LZT is widely regarded as a most relevant model of naturally occurring tolerance to contact allergens. LZT is hapten specific and can be transferred to naive animals by CD8+ LN T cells from tolerized mice (4–6). These LZT effector T cells exhibit characteristic features of suppressor T cells, including the production of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 (4–6). The mechanisms of CHS prevention by LZT effector T cells and the signals involved in their generation remain unknown, however.

IL-10 was first recognized for its inhibition of T cell activation and effector functions. Now, it is regarded to be a multifunctional cytokine that can limit and ultimately terminate inflammatory responses, including allergic reactions (7, 8). IL-10 was initially characterized as a cytokine produced by certain Th2 cell clones. Many other cell types, however, such as macrophages, B cells, mast cells, and keratinocytes have been shown to secrete considerable amounts of this cytokine (7, 8). IL-10 downregulates the expression of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules and inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-12 by DCs and other professional antigen-presenting cells (7, 8). In addition, IL-10 is crucial for the differentiation and immunosuppressive functions of regulatory T cell (Tr cell) populations such as Tr1 cells and Tr1-like cells, which can control tolerance and other immune responses in vivo and in vitro (9, 10).

In this study, we employed IL-10–deficient mice to characterize the role of IL-10 in LZT. We demonstrate that LZT cannot develop in the absence of IL-10 because IL-10, which is produced by CD4+ LN T cells, is required for the development of LZT effector CD8+ T cells.

Methods

Mice.

Mice deficient for IL-10 (IL-10–/– mice), corresponding wild-type mice (IL-10+/+ mice) on a C57BL/6 genetic background, genetically mast cell–deficient (MC-deficient) KitW/KitW-v mice, and normal Kit+/+ mice, as well as Rag1–/– mice, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA), and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Animal Care Facilities of the University Hospital Mainz (Mainz, Germany). Mice were used between 8 and 12 weeks of age in experimental groups of six to eight animals. All animal care and experimentation were conducted in accordance with current federal, state, and institutional guidelines.

Reagents and cytokines.

Picrylchloride (TNCB; 2,4,6-trinitro-1-chlorobenzene) and picrylsulfonic acid (TNBS; 2,4,6-trinitro-benzenesulfonic acid) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Deisenhofen, Germany). Recombinant murine IL-10 (rmIL-10) was a generous gift of Schering-Plough USA (Palo Alto, California, USA).

Induction of tolerance.

LZT was induced by topical treatment of shaved mice with tolerizing doses of 0.45 or 4.5 μg TNCB dissolved in 15 μl acetone/olive oil (AOO; 3:1 vol/vol) or AOO alone as control five times on every second day. On day 10, mice were sensitized by epicutaneous application of 450 μg TNCB in 15 μl AOO to induce CHS. Challenge was performed by painting 45 μg TNCB onto the dorsal side of the right ear at day 15, and increase of ear thickness was measured after 24 hours and 48 hours, respectively, using an engineer‘s micrometer (Oeditest; Kroeplin GmbH, Schlüchtern, Germany). Results are expressed as mean values in units of millimeters × 10–2 or percentage of control plus or minus SEM.

Preparation of LN cells and enriched T cells for cell culture and adoptive transfer.

Auricular, cervical, and inguinal LN, obtained 24 hours after induction of LZT or challenge, were homogenized mechanically and passed through a sterile 70-μm nylon cell strainer. For cell culture, LN cells (LNCs) (106 cells/100 μl) were resuspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 1% heat-inactivated syngeneic normal mouse serum (NMS). CD4+/CD8+ T cell populations were purified using magnetic cell-sorting beads, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (purity: more than 96% CD4+/CD8+, more than 98% T cells; Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany), and finally resuspended in RPMI-1640 (106 cells/100 μl) stimulated with 0.5 × 106 haptenized spleen cells (see below).

Haptenization of LNCs and spleen cells.

LNCs or spleen cells (107 cells/ml) were incubated in 10 mM TNBS in HBSS for 10 minutes at 37°C, subsequently washed three times in RPMI-1640, and resuspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 1% syngeneic NMS.

Cytokine ELISAs.

Supernatants of LNC cultures were harvested after 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours and kept frozen at –70°C until use. Concentrations of murine IL-4 and IL-10 in the culture supernatants were determined using OptEIA ELISA kits from Pharmingen (Hamburg, Germany). Concentrations of IFN-γ in the culture supernatants were determined using the IFN-γ DuoSet system from R&D Systems (Wiesbaden, Germany). All ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sensitivity was 5 pg/ml for IL-4 and IL-10, and 10 pg/ml for IFN-γ.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay for IL-10 production.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, California, USA). Briefly, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were separated by positive selection using immunobeads as described above. T cells (106) were stimulated with 2.5 × 105 irradiated hapten-modified or control spleen cells for 24 hours. Subsequently, the cocultured cells were placed in wells of the 96-well ELISPOT plates (106 cells per well) coated with the capture anti–IL-10 Ab (50 μl/well). After 24 hours, the plates were washed, and the biotinylated detection Ab (50 μl/well) was added. Thereafter, the plates were incubated with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase for 4 hours at RT (ELISPOT blue color module; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Colorimetric reaction was obtained using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3′ indolylphosphate p-toluidine salt and nitroblue tetrazolium chloride solution to visualize the spots. The assay was run in triplicate, and the spots were counted by computer-assisted image analysis (ELISPOT Reader System; AID GmbH, Strassberg, Germany).

Proliferation assay.

After 24 hours of culture, cells were pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]thymidine (Amersham Biosciences Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) for 18 hours. Incorporated radioactivity was determined using a liquid scintillation counter (1205 Betaplate; LKB Wallac, Stockholm, Sweden). Results are expressed as mean counts per minute of triplicate wells plus or minus SEM.

IL-10 reconstitution in IL-10–/– mice and treatment of IL-10+/+ mice with IL-10.

IL-10–/– mice were reconstituted (100 ng rmIL-10 in 200 μl PBS/2% FCS, intraperitoneally) three times per day during the induction phase or the effector phase of tolerization. IL-10+/+ mice and IL-10–/– mice injected with vehicle alone served as controls. In some experiments, IL-10+/+ mice were treated following the same protocol.

Adoptive transfer of LNCs or enriched T cells.

IL-10–/– and IL-10+/+ mice were tolerized with 4.5 μg TNCB or treated with vehicle (AOO) alone. LNCs (5 × 107 cells/100 μl PBS) and enriched T cells (107 cells/100 μl PBS) were prepared as described and injected intravenously into untreated IL-10+/+ mice. Subsequently, sensitization and challenge were performed as described above.

In other experiments, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were obtained from naive IL-10–/– and IL-10+/+ mice using positive selection on immunobeads as described. CD4+ T cells (2 × 107), and CD8+ T cells (1 × 107) were adoptively transferred into T cell–deficient Rag1–/– mice. After 2 days, the protocol of tolerization and sensitization was run on these mice as described.

Measurements of tissue IL-10.

At various time points after application of sensitizing or tolerizing doses of TNCB or AOO alone, mice were killed and the ears were excised and submerged immediately into liquid N2. The frozen tissue was pulverized, dissolved in 1 ml PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, and homogenized for 30–60 seconds. Subsequently, the samples were refrozen in liquid N2, thawed at 37°C, sonicated for 15 seconds, and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 10,000 g. Supernatants were harvested, and IL-10 was quantified as described above. Results were normalized to total protein as determined by a protein assay (Pierce, Bonn, Germany).

Statistics.

The statistical significance of differences between experimental groups was evaluated using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney two-sample test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results and Discussion

IL-10 is required for the induction of LZT to contact allergens.

The cytokine network plays a pivotal role in the orchestration of immune responses to contact allergens. Both proinflammatory and immunosuppressive cytokines are critical for the function of immunocompetent cells that promote the development of either contact hypersensitivity or tolerance (11). In this study, we tested whether IL-10 contributes to the development of LZT, a most suitable model of hapten-specific tolerance induced by the application of low doses of allergenic chemicals (4–6). IL-10–/– mice and IL-10+/+ mice were treated repeatedly with low doses of the contact allergen TNCB before they were sensitized with a single high-dose application of TNCB to induce CHS. LZT to contact allergens was assessed by measuring increases in skin thickness, which reflect allergic inflammatory responses after topical application of TNCB (challenge) to the ears of sensitized mice. As expected, IL-10+/+ mice pretreated with low doses of TNCB developed normal LZT and exhibited markedly reduced ear swelling after challenge with TNCB as compared with vehicle-pretreated mice. In contrast, IL-10–/– mice failed to develop LZT; that is, allergic inflammatory responses were virtually identical in IL-10–/– mice pretreated with low doses of TNCB or vehicle (Figure 1a), indicating that LZT cannot develop without IL-10.

Figure 1.

IL-10 is required for the induction of LZT, whereas CHS prevention in tolerized mice is IL-10 independent. Expression of LZT quantified by assessing allergic inflammatory responses (ear swelling) after TNCB challenge in IL-10+/+ mice and IL-10–/– mice that were treated repeatedly with low doses of contact allergen (TNCB) to induce LZT and then sensitized to TNCB. Some IL-10–/– mice were reconstituted with IL-10 during tolerization (the induction phase of LZT) or during sensitization (the effector phase of LZT). Data represent relative (a) and absolute (b) changes in ear thickness (means ± SEM) pooled from six or more mice per treatment group from one of three independent experiments with similar results. #P < 0.001.

CHS responses in IL-10–/– mice were markedly increased as compared with IL-10+/+ mice (Figure 1). This is in line with reports showing that IL-10 is produced and released by activated keratinocytes during the induction and elicitation phase of CHS and that IL-10 controls CHS responses by inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines (12, 13).

Regulatory CD8+ effector T cells of LZT reportedly produce and secrete large amounts of the immunosuppressive T cytotoxic 2 (Tc2) cells cytokines IL-4 and IL-10. Speculating that LZT development in IL-10–/– mice is impaired because LZT effector T cells in these mice cannot produce IL-10, we compared LZT responses in IL-10–/– mice that were reconstituted with rmIL-10 during the effector phase of LZT or treated with vehicle. Unexpectedly, IL-10 did not normalize LZT in IL-10–/– mice when given during its effector phase. This suggests that IL-10 is a dispensable effector cytokine of LZT and that IL-10 is not important for preventing the development of allergen-specific cytotoxic CHS effector T cells in the context of LZT.

In contrast, injection of IL-10 during the induction phase of LZT (i.e., during repeated applications of low-dose TNCB) completely restored LZT development in IL-10–/– mice (Figure 1). These findings prove that IL-10 is critical for the induction of LZT. They also show that LZT in IL-10–/– mice is impaired due to the absence of IL-10 during tolerization and not developmental defects in these mice.

Previous studies and the results described above demonstrate that regulatory LZT effector T cells differ from “classical” regulatory T cells, that is, CD4+/CD25+ cells or Tr1 cells, in several important aspects (4, 5). Unlike CD4+/CD25+ cells, Tr1 cells, and Tr1-like cells (all of which are CD4+), LZT effector cells are CD8+ T cells (9, 10, 14, 15). In contrast to CD4+/CD25+ cells, LZT effector T cells are antigen specific, and, unlike Tr1 cells, they do not suppress ongoing antigen-specific immune responses, but rather prevent their development (14–16). Here, we have identified yet another unique feature of LZT effector T cells. While Tr1 cells and CD4+/CD25+ cells exert their regulatory effects by IL-10, LZT effector T cells prevent immune responses independent of IL-10 (14–19). Thus, LZT effector T cells represent a novel population of regulatory T cells. These regulatory T cells are also clearly different from other CD8+ “suppressor” T cells, including a recently described IL-10–producing CD8+ T cell population (20, 21). This T cell subset reportedly develops from naive T cells after priming with allogeneic CD40 ligand-activated plasmacytoid DCs or immature DCs (20, 21). Unlike the regulatory T cells responsible for LZT, these immunosuppressive CD8+ T cells require IL-10 to down-modulate immune responses, for example, by inhibiting the allospecific proliferation of naive T cells to monocytes or DCs (20, 21).

The development of LZT effector T cells is IL-10 dependent.

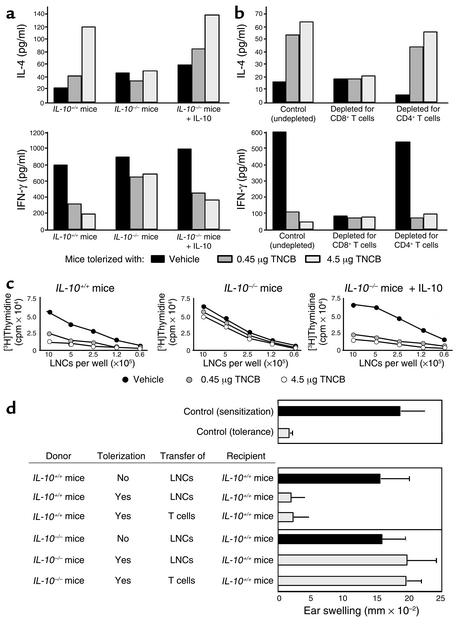

Impaired LZT in IL-10–/– mice can be repaired by adoptively transferring IL-10 before, but not after, sensitization. This clear-cut difference shows that LZT is composed of two separate and successive phases: the LZT induction phase, in which IL-10 is needed, followed by the LZT effector phase, which is IL-10 independent. Hypothesizing that IL-10 is needed during LZT induction to promote the development of LZT effector T cells, we asked whether two crucial LZT effector mechanisms, namely, skewing a CHS-promoting Tc1 cytokine pattern toward Tc2 and preventing clonal expansion of allergic T cells after sensitization and challenge, are impaired in the absence of IL-10 (12, 22). We pretreated IL-10–/– mice, IL-10+/+ mice, and IL-10–/– mice reconstituted with IL-10 during the induction phase of LZT with low doses of TNCB or vehicle and then sensitized with TNCB. When LNCs obtained from these mice were assayed for TNCB-induced release of cytokines, we found that tolerized IL-10+/+ mice exhibited markedly reduced IFN-γ release and greatly increased IL-4 secretion as compared with vehicle-pretreated mice (Figure 2a). In contrast, LNCs from low-dose TNCB-treated IL-10–/– mice failed to develop such Tc2-skewed cytokine release patterns (4, 5). Reconstitution of IL-10–/– mice with IL-10 during tolerization repaired this defect and resulted in Tc2 cytokine patterns characteristic for impaired CHS responses in tolerized animals (Figure 2a). Figure 2b shows that this IL-10–dependent Tc2 skewing observed in tolerized mice indeed requires CD8+ LZT effector cell development. Virtually no upregulation of IL-4 levels or reduction of IFN-γ production is seen in antigen-challenged T cells from tolerized mice depleted for CD8+ T cells (Figure 2b), that is, the T cell subset we have recently reported to be required for transferring LZT to naive mice (4).

Figure 2.

The development of LZT effector T cells is IL-10 dependent. Mice were treated with solvent or tolerizing doses of TNCB (0.45 or 4.5 μg) and subsequently sensitized and challenged. After 24 hours, LNCs from (a) IL-10+/+, IL-10–/–, or IL-10–/– mice reconstituted with IL-10–/– or (b) whole LNCs or LNCs depleted of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells from IL-10+/+ mice were obtained to measure the release of IL-4 (Tc2/Th2 cytokine) and IFN-γ (Tc1/Th1 cytokine) by ELISA (48 hours after hapten-specific restimulation). (c) LNCs were isolated 24 hours after challenge from IL-10+/+, IL-10–/–, or IL-10–/– mice reconstituted with IL-10 and treated as described above. Thirty-six hours after hapten-specific restimulation, the proliferation of LNCs was measured by incorporation of [3H]thymidine. In each case, one of three independent experiments with similar results is shown. (d) In some experiments LNCs or T cells isolated from LNCs (> 95% purity) 24 hours after tolerization or treatment with solvent were transferred to untreated mice (one single intravenous injection of 5 × 107 LNCs or 1 × 107 T cells per mouse), and expression of LZT in these animals was assessed after sensitization and challenge by measuring ear-swelling responses.

Along the same line, LNCs from IL-10–/– mice subjected to repeated low-dose TNCB treatment failed to inhibit TNCB-induced LNC proliferation upon restimulation. In contrast, LNCs obtained from identically treated IL-10+/+ mice or IL-10–reconstituted IL-10–/– mice showed significantly reduced TNCB-specific proliferative responses (Figure 2c). Taken together, these findings show that Tc2 skewing of LNC cytokine production and downregulation of LNC proliferation in low zone tolerized and sensitized mice are IL-10 dependent and require the presence of LZT effector T cells. Therefore, we attempted to prove that IL-10 is required during LZT induction to facilitate regulatory LZT effector CD8+ T cell development. As shown in Figure 2d, animals that had received LNCs or purified T cells from tolerized IL-10+/+ mice developed robust LZT responses confirming that LZT effector cells had developed during tolerization in the presence of IL-10. In contrast, LNCs or T cells obtained from IL-10–/– mice treated with low-dose TNCB did not transfer LZT to naive recipient IL-10+/+ mice. Thus, the generation of LZT effector cells during the induction phase of LZT is IL-10 dependent. These data provide further direct evidence that LZT effector CD8+ T cells represent a distinct subgroup of regulatory T cells, because IL-10 is essential for their development, whereas other regulatory T cell populations (e.g., CD4+/CD25+ T cells) are not induced by IL-10 (9, 14, 23, 24).

Low zone tolerization markedly upregulates IL-10 production in LN CD4+ T cells.

We next tried to clarify what cells provide the IL-10 that is required for the generation of CD8+ LZT effector T cells and the induction of LZT. MCs are known to produce considerable amounts of IL-10 (25), and IL-10 released from MCs is thought to be crucial for hapten-specific tolerance induced by low-dose UVB irradiation of the skin (26, 27). To test whether MC-derived IL-10 may also be involved in the induction of LZT we elicited CHS responses in genetically MC-deficient KitW/KitW-v mice and normal Kit+/+ mice that had been pretreated repeatedly with low doses of TNCB or vehicle. KitW/KitW-v mice, however, showed normal development of LZT, indicating that IL-10 released from MCs is not necessary to induce normal LZT (Figure 3a). Because IL-10 can also be produced by non-MC cutaneous cell populations, including keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (7, 8), we measured IL-10 production in murine skin that had been treated with tolerizing doses of TNCB. As assessed by ELISA, low zone tolerization did not result in increased cutaneous IL-10 levels as compared with vehicle-treated control skin (Figure 3b). In contrast, sensitization with TNCB induced markedly upregulated IL-10 levels in the skin as soon as 1 hour and up to 24 hours after application (Figure 3b). This indicates that IL-10 production in the skin can be induced by contact allergens but is not increased during normal LZT development (Figure 3b) (12).

Figure 3.

Low zone tolerization upregulates IL-10 production in LN CD4+ T cells. (a) LZT quantified by assessing contact hypersensitivity reaction (ear swelling) after TNCB challenge in KitW/KitW-v mice, which are genetically deficient for IL-10–producing MCs, and Kit+/+ mice that were treated repeatedly with low doses of contact allergen (TNCB) to induce LZT and then were sensitized to TNCB. (b) At various time points after application of sensitizing or tolerizing doses of TNCB or AOO alone, ears were excised, and supernatants of the tissue extracts were prepared as described in Methods. Amounts of IL-10 were measured by ELISA, and the results were normalized to amounts of total protein. Results are presented as picograms per milligram of protein of the tissue extract. #P < 0.001. (c and d) IL-10 release from T cells (CD4+ or CD8+) and non–T cells isolated from LNCs obtained from control (–) or tolerized (+) mice after induction of LZT was measured by ELISA (c) or by ELISPOT (d) after hapten-specific restimulation in vitro.

Consequently, we asked whether relevant amounts of IL-10 are produced in draining LNs after tolerization. We found that LNCs obtained from tolerized mice secrete considerable amounts of IL-10 as early as 24 hours after a single low-dose application of TNCB (Figure 3c). When we characterized IL-10–producing LNCs from tolerized mice in greater detail, we found that only T cells, specifically CD4+ T cells, produced increased amounts of IL-10 after low zone tolerization as shown by two different methods, ELISA (Figure 3c) and ELISPOT assay (Figure 3d). These data rule out CD8+ T cells, including LZT effector T cells, as a source of IL-10 during LZT induction. This clearly shows that low zone tolerization results in the development of CD8+/IL-10 negative pre-effector T cells, which differentiate into CD8+/IL-10–producing LZT effector T cells upon re-exposure to the specific antigen in vivo or in vitro.

CD4+ LN T cells provide the IL-10 required for LZT induction.

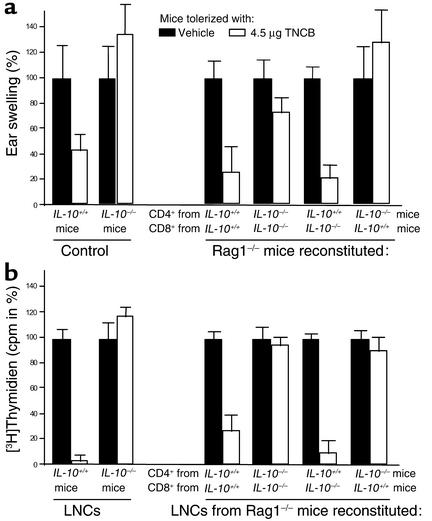

LN CD4+ T cells were found to be the only skin cells or LNCs that produce relevant amounts of IL-10 after tolerization, but does CD4+ T cell–derived IL-10 contribute to LZT induction? To address this question we performed adoptive transfer experiments using T cell–deficient Rag1–/– mice as recipients of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells obtained from naive IL-10–/– and/or IL-10+/+ mice (Figure 4a). Subsequently, host animals were tolerized by repeated applications of low doses of TNCB, and LZT responses were assessed measuring ear swelling after sensitization and challenge. As demonstrated in Figure 4a, animals receiving CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from IL-10+/+ mice developed robust tolerance to TNCB. LZT could not be induced, however, after reconstitution with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from IL-10–/– mice, confirming our results in IL-10–/– and IL-10+/+ animals (Figure 4a). Notably, mice injected with CD4+ T cells obtained from IL-10–/– mice and CD8+ T cells derived from IL-10+/+ mice also failed to develop LZT. To the contrary, reconstitution of Rag1–/– with IL-10+/+ CD4+ T cells and IL-10–/– CD8+ T cells resulted in normal LZT responses (Figure 4a). These findings formally prove that the IL-10 produced by CD4+ T cells is required for the induction of LZT. In contrast, CD8+ effector T cell–derived IL-10 is not required for normal LZT responses.

Figure 4.

IL-10–producing regulatory CD4+ T cells are required for the induction of LZT. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were separated from LNCs obtained from naive IL-10+/+ and IL-10–/– mice as described above and adoptively transferred into T cell–deficient Rag1–/– mice (2 × 107 CD4+ and 1 × 107 CD8+ T cells). Subsequently, the mice were treated repeatedly with low doses of contact allergen (TNCB) to induce LZT and were then sensitized and challenged. IL-10–/– and IL-10+/+ served as control mice for CHS and LZT induction. (a) Ear thickness (percentage ± SEM) and (b) proliferation (cpm in % of sensitized control mice) of LNCs after hapten-specific restimulation in vitro pooled from six or more mice per treatment group from one of two independent experiments with similar results was shown.

In confirmation of these results we found that LNCs obtained from Rag1–/– mice reconstituted with IL-10+/+ CD4+ T cells and IL-10–/– CD8+ T cells exhibited significantly reduced TNCB-specific proliferative response after restimulation, as was to be expected after normal development of LZT. In contrast, LNCs from Rag1–/– mice adoptively transferred with IL-10–/– CD4+ T cells and IL-10+/+ CD8+ T cells (which did not develop LZT) showed uninhibited antigen-specific proliferation. These observations clearly show that IL-10 is a critical signal in the interaction and sequential activation of the two distinct regulatory T cell populations required for normal LZT induction: CD4+ regulatory T cells promote the generation of CD8+ LZT effector T cells by IL-10.

CD4+ regulatory T cells are known to be pivotal players in several settings of suppression of immune cell functions, including peripheral tolerance. Yet, precise effector mechanisms remain to be defined for most types of CD4+ regulatory T cells. Some CD4+ regulatory T cells (i.e., Tr1) can suppress immune responses by cell-cell interactions and/or the production of IL-10 and TGF-β (9, 10). Other subsets of CD4+ regulatory T cells (i.e. CD4+/CD25+ T cells) can also exert immunosuppressive effects by cell-cell contact, whereas IL-10 and other cytokines may be less important (14–16).

The LZT-promoting CD4+ T cell population identified here is the first CD4+ regulatory T cell subset that can induce the generation of regulatory CD8+ T cells. Our findings also indicate that this interaction is antigen specific and mediated by IL-10. Whether these cells represent a previously characterized or a distinct subset of CD4+ regulatory T cells will need to be clarified in further experiments.

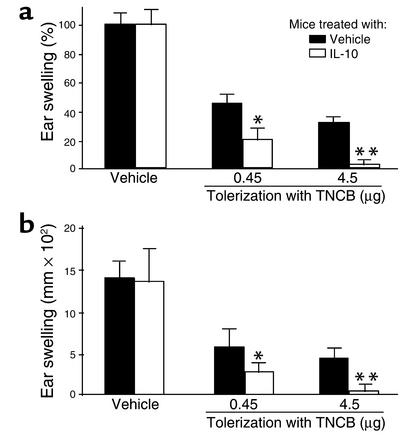

IL-10 enhances the development of LZT to contact allergens.

Finally, we asked whether LZT development can be enhanced by treating normal mice with IL-10 during the induction phase of LZT. Repeated systemic application of IL-10 to C57BL/6 mice during tolerization significantly improved LZT in these mice (Figure 5). Whereas normal LZT in control mice reduced allergic inflammatory responses about 60–70%, LZT in IL-10–treated mice almost completely inhibited (up to 96% reduction) allergic inflammation (Figure 5). Thus, exogenous IL-10, when applied together with low doses of contact allergen, can be used to substantially improve the prevention of CHS in mice.

Figure 5.

Exogenous IL-10 improves the development of tolerance to contact allergen. Ear-swelling responses after sensitization and challenge with TNCB in normal mice that had been treated with IL-10 (intraperitoneal injection of 100 ng per mouse three times a day) or vehicle during low zone tolerization. Data represent absolute (a) and relative (b) changes in ear thickness (means ± SEM pooled from six or more mice per treatment group from one of three independent experiments with similar results). **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05 for IL-10–treated versus vehicle-treated animals.

In summary, our data provide formal evidence that IL-10 is essential for the induction of LZT to contact allergens and suggest that LZT requires a sequential activation and complex interaction of at least two distinct regulatory T cell populations: (a) skin exposure to low-dose contact allergen results in the release of IL-10 by CD4+ T cells in draining LNs, which promote (b) the IL-10–dependent development of CD8+ pre-effector cells of LZT that exhibit negligible production of IL-10. (c) Re-exposure to sensitizing doses of the contact allergen leads to the differentiation of these pre-effector cells into IL-10–producing LZT effector CD8+ T cells, which (d) impede the generation of CHS effector T cells independent of IL-10. Thus, IL-10–dependent LZT induction requires both CD4+ T cells, which provide IL-10, and CD8+ T cells, which depend on this IL-10 to become pre-effector cells and, ultimately, effector cells of LZT. Because these IL-10–dependent LZT effector cells impede allergic inflammation independent of IL-10, they can be readily distinguished by phenotype and function from all other known regulatory T cell populations, including immunosuppressive CD8+ T cells and classical CD4+ regulatory T cells such as Tr1 cells and CD4+/CD25+ T cells. Our findings suggest that IL-10–driven LZT effector T cell generation may be used to prevent the development of contact allergies and encourage the examination of the role of this novel subclass of regulatory T cells in further harmful immune responses, for example other allergic or autoimmune disorders.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the University of Mainz (Mainzer Foerderungsprogramm) to K. Steinbrink (STE/791-4) and M. Maurer (SFB548/B10). We thank Schering-Plough USA for rmIL-10; Stephen Galli, Mark Udey, and Esther von Stebut for helpful discussion; Jodie Urcioli for help with the manuscript; and Ruth Alt for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

M. Maurer and W. Seidel-Guyenot contributed equally to this paper.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: low zone tolerance (LZT); contact hypersensitivity (CHS); regulatory T cell (Tr cell); mast cell (MC); 2,4,6-trinitro-1-chlorobenzene (TNCB); 2,4,6-trinitro-benzenesulfonic acid (TNBS); recombinant murine IL-10 (rmIL-10); acetone/olive oil (AOO); LN cell (LNC); normal mouse serum (NMS); enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT).

References

- 1.Strobel S, Mowat AM. Immune responses to dietary antigens: oral tolerance. Immunol. Today. 1998;4:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swartz RP. Role of UVB-induced serum factor(s) in suppression of contact hypersensitivity in mice. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1984;83:305–307. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12340434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Battisto JR, Miller J. Immunological unresponsiveness produced in adult guinea pigs by parenteral introduction of minute quantities of hapten or protein antigen. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1962;11:111–115. doi: 10.3181/00379727-111-27717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinbrink K, Sorg C, Macher E. Low zone tolerance to contact allergens in mice: a functional role for CD8+ T helper type 2 cells. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:759–768. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinbrink K, Kolde G, Sorg C, Macher E. Induction of low zone tolerance to contact allergens in mice does not require functional Langerhans cells. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1996;107:243–247. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12329721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinbrink K, Pior J, Vogl T, Sorg C, Macher E. Contact tolerance. Pathobiology. 1999;67:311–313. doi: 10.1159/000028087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore KW, de Waal Malefy R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mocellin S, Panelli MC, Wang E, Nagorsen D, Marincola FM. The dual role of IL-10. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:36–43. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R, Bordignon C, Narula S, Levings MK. Type 1 T regulatory cells. Immunol. Rev. 2001;182:68–79. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Schuler G, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of interleukin 10-producing, nonproliferating CD4+ T cells with regulatory properties by repetitive stimulation with allogeneic immature human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1213–1222. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enk A, Katz SI. Early molecular events in the induction phase of contact sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:1398–1402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe H, Unger M, Tuvel B, Wang B, Sauder DN. Contact hypersensitivity: the mechanism of immune responses and T cell balance. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:407–412. doi: 10.1089/10799900252952181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson TA, Dube P, Griffith TS. Regulation of contact hypersensitivity by interleukin 10. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1597–1604. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:389–400. doi: 10.1038/nri821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakaguchi S, et al. Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells: their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol. Rev. 2001;182:18–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1820102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suri-Payer E, Amar AZ, Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ T cells inhibit both the induction and effector function of autoreactive T cells and represent a unique lineage of immunoregulatory cells. J. Immunol. 1998;160:1212–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asseman C, Mauze S, Leach MW, Coffman RL, Powrie F. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:995–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groux H, et al. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature. 1997;389:737–742. doi: 10.1038/39614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Izikson L, Liu L, Weiner HL. Activation of CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells by oral antigen administration. J. Immunol. 2001;167:4245–4253. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilliet M, Liu YJ. Generation of human CD8 T regulatory cells by CD40 ligand-activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:695–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhodapkar MV, Steinman RM, Krasovsky J, Munz C, Bhardwaj N. Antigen-specific inhibition of effector T cell function in humans after injection of immature dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:233–238. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu H, DiIulio NA, Fairchild RL. T cell populations primed by hapten sensitization in contact sensitivity are distinguished by polarized patterns of cytokine production: interferon gamma-producing (Tc1) effector CD8+ T cells and interleukin (IL) 4/IL-10-producing (Th2) negative regulatory CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1001–1012. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suto A, et al. CD4+CD25+ T-cell development is regulated by at least 2 distinct mechanisms. Blood. 2002;99:555–560. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levings MK, et al. IFN-alpha and IL-10 induce the differentiation of human type 1 T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 2001;166:5530–5539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishizuka T, Okayama Y, Kobayashi H, Mori M. Interleukin-10 is localized to and released by human lung mast cells. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 1999;29:1424–1432. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beissert S, et al. Impaired immunosuppressive response to ultraviolet radiation in interleukin-10-deficient mice. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1996;107:553–557. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12582809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alard P, Kurimoto I, Niizeki H, Doherty JM, Streilein JW. Hapten-specific tolerance induced by acute, low-dose ultraviolet B radiation of skin requires mast cell degranulation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:1736–1746. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1736::aid-immu1736>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]