Abstract

Telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme responsible for the addition of telomeres onto the ends of chromosomes. Short or dysfunctional telomeres can lead to cell growth arrest, apoptosis, and genomic instability. Telomerase uses its RNA subunit to copy a short template region for telomere synthesis. To probe for regions of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA essential for function, we assayed 27 circularly permuted RNA deletions for telomerase in vitro activity and binding to the telomerase reverse transcriptase catalytic protein subunit. We found that stem-loop IV is required for wild-type telomerase activity in vitro and will stimulate processivity when added in trans.

Telomeres provide chromosome stability by protecting the DNA ends from recombination, degradation, and fusions. Telomerase is a specialized reverse transcriptase that uses an intrinsic RNA to template the de novo synthesis of telomeres onto the 3′ ends of linear chromosomes (reviewed in reference 7). Synthesis of telomeres counteracts the natural loss of DNA ends that occurs with every cell division. Failure to maintain telomere sequence and length can result in growth arrest and a loss of cellular viability (17).

Telomerase contains both RNA and protein subunits. Telomerase RNA, first identified from the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila (16), has been cloned from a number of different organisms, including other ciliates (22, 25, 26, 30, 31), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (27, 32), and vertebrates (8, 10, 14). Phylogenetic analysis was used to determine the RNA secondary- structures of both the ciliate (22, 25, 30) and vertebrate telomerase RNAs (10). Although the RNA size and sequence varies among these groups of organisms, common secondary structure features suggest a conservation of telomerase RNA function. The protein component, telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), is the catalytic subunit and shares homology to reverse transcriptases (reviewed in references 9 and 23). In vitro activity can be reconstituted in rabbit reticulocyte lysates that express the TERT protein in the presence of telomerase RNA using either mammalian or Tetrahymena components (5, 12, 35).

Telomerase can repeatedly utilize an internal RNA template sequence from its integral RNA subunit to synthesize telomere repeats (16). The telomerase RNA template region anneals to the 3′ end of telomeric DNA substrate and the catalytic activity of TERT elongates the telomere substrate. Telomerase activity is measured in vitro by its ability to elongate single-stranded telomeric oligonucleotides. Tetrahymena telomerase is a processive enzyme such that it can elongate a single telomeric substrate with multiple telomere repeats before dissociation (15). Telomerase processivity requires an interaction between the telomere substrate and the enzyme in addition to the telomere-template complementary annealing. This additional interaction site is referred to as the anchor site (13, 18). The Tetrahymena TERT (tTERT) protein subunit alone has been shown to provide the anchor site for Tetrahymena telomerase (33).

There are defined structural and functional regions of the telomerase RNA that are important for efficient telomerase activity and processivity in vitro. First, tight interactions between telomerase RNA and tTERT, located upstream of the template region, are required for an active complex and for providing a 5′ template boundary (Fig. 1) (19). This tTERT-binding region overlaps with a conserved ciliate element originally shown to be required for template definition (Fig. 1) (1). Loss of a template boundary can cause read-through past the telomere sequence template that would prevent proper telomere-template annealing for the next round of repeat synthesis. Second, a template recognition element, located downstream of the template region, is required for repetitive template sequence usage (Fig. 1) (28). In this report we describe a region at the distal end of stem-loop IV that is required for telomerase activity and that can stimulate telomerase processivity in trans.

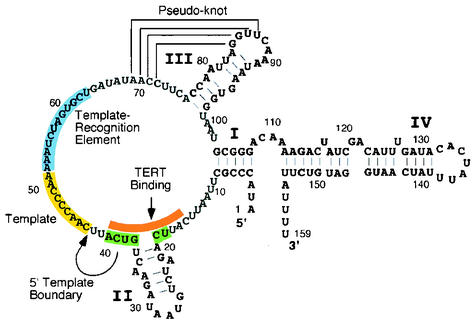

FIG. 1.

Summary of the functional regions identified in Tetrahymena telomerase RNA. The Tetrahymena RNA contains four helical regions, stem I to IV, and a conserved pseudoknot structure (brackets) (30). The specific helical regions are marked with a Roman numeral, and the nucleotide positions for each region are marked every 10 bases beginning at the 5′end. The template region is highlighted in yellow. A sequence conserved in ciliates that defines the template boundary is highlighted in green (1). This sequence overlaps with the defined tTERT-binding region shown in orange (19, 20). A region important for template utilization, the template-recognition element, is highlighted in blue (28).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Telomerase RNA synthesis.

To generate a tandem duplication of the Tetrahymena telomerase RNA gene, a two-step PCR strategy was carried out. Two different telomerase RNA genes were PCR amplified with 5′ and 3′ primers that anneal to the 5′ and 3′ regions of the telomerase RNA gene. Gene one included 5′ telomerase RNA sequences at the end of the 3′ primer while gene two included 3′ sequences at the end of the 5′ primer to generate an overlapping region. The pieces were then annealed and extended followed by PCR to amplify the tandem repeat. The PCR primers included a 5′ XbaI and 3′ BamHI restriction sites for cloning into the vector pT7159.

To generate the set of 27 circularly permuted deleted telomerase RNAs, PCR was carried out using the appropriate 5′ and 3′ primers using the telomerase RNA gene duplication as a template. PCR also was performed to create DNA templates for transcription for the wild-type, stem-loop IV nucleotides (nt) 112 to 159 and other RNA mutants. Unless RNAs already had a 5′ G residue, each 5′ primer included the T7 RNA polymerase promoter followed by the nucleotides GA at the start site for enhanced in vitro transcription. PCR products were gel purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen) and eluted in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5. RNA was in vitro transcribed as described by the manufacturer (Invitrogen) by T7 RNA polymerase from the PCR DNA template. RNA was gel purified on 4 or 8% denaturing gel electrophoresis by UV shadowing. The RNAs nt 15 to 40 (stem II) and nt 128 to 142 (distal stem-loop IV) of telomerase RNA were synthesized chemically (Dharmacon, Lafayette, Colo.) and gel purified. RNA concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically.

Rabbit reticulocyte lysate telomerase reconstitution and immunopurification.

To generate five tandem repeats of the T7-tag epitope sequence at the amino terminus of tTERT, complementary oligonucleotide primers were designed to create two units of the T7 epitope tag that overlapped by 20 bases. Extension and amplification by PCR generated a mixture of DNA products that contained two to hundreds of tandem T7 epitope DNA repeats. DNA products were electrophoresed and the band corresponding to five repeats was gel purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen). Another PCR step using 5′ and 3′ primers with the restriction sites was performed followed by cloning into the pCite/tTERT vector at MscI and NdeI restriction sites. Sequencing was performed to confirm the correct sequence was generated.

5xT7-tTERT was expressed from pCITE-4a (Novagen) by using the TNT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation system (Promega). Protein synthesis was carried out for 60 min at 30°C. In vitro-transcribed telomerase RNA was added to reactions for additional 20 min to assemble with tTERT. Total yeast RNA was added at 1 μg/μl as a nonspecific competitor RNA for binding experiments. Lysates were diluted eightfold with immunopurification buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. T7-tag antibody-agarose beads (Novagen) were added to the diluted lysates and incubated for 4 to 16 h at 4°C. Beads were washed four times with immunopurification buffer before being assayed for telomerase activity and telomerase components.

Telomerase assay.

Telomerase assays were performed using immunopurified telomerase on beads in 10 μl of immunopurification buffer. Samples were added to a telomerase reaction mix that contained 1 μM primer d(GGGGTT)3, 250 μM dTTP, 5 μM dGTP, 0.17 μM [α-32P]dGTP (3,000 Ci/mmol), 1 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris acetate (pH 8.5), 1 mM spermidine, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 50 mM potassium chloride. Additionally, RNAs added in trans were included as indicated. Samples were assayed in a final volume of 20 μl at 30°C for 20 to 40 min. The reactions were phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and resolved on 8% (19:1) acrylamide-7 M urea-1× Tris-borate-EDTA gel. Dried gels were exposed to phosphorimager plates (Fuji) or X-ray film (Kodak). A 32P-radiolabeled 12-base DNA oligonucleotide (5,000 to 10,000 cpm) was added before phenol extraction as a control for DNA recovery and loading. Telomerase activity and processivity quantification was performed by summing the telomerase products + 7, +13, +19, +25, +31, and +37 from gels exposed to phosphorimager plates. Each measurement was then normalized to wild-type. Telomerase processivity was quantified as described previously (9a). In brief, the intensity of each major repeat band was measured, and normalized to both the intensity of the first band and the number of 32P-labeled nucleotides incorporated. Normalized intensities were then plotted versus the repeat number.

Northern blots.

RNA was extracted from telomerase immunopurification samples by acid phenol-chloroform and precipitated. RNA was then resolved on 8% (19:1) acrylamide-7 M urea-1× Tris-borate-EDTA gels and transferred to Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham) for 45 min at 1 A using an electroblotter. Telomerase RNA t108 was added before extraction as an RNA recovery and loading control. RNA was UV-cross-linked to the membrane with a UV Stratalinker (Stratagene) and then was subjected to hybridization in a solution containing 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 500 mM NaCl, 50% formamide, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.5% blocking reagent (Amersham) at 25 to 30°C. Telomerase RNA was probed with 32P-radiolabeled oligonucleotides that hybridize to sequences 3′ of the template and stem IV. The membrane was then washed three times with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 25 to 30°C and exposed to phosphorimager plates (Fuji) or X-ray film (Kodak).

RESULTS

To understand the role of telomerase RNA in telomerase enzyme function, we scanned the entire RNA with small deletions and tested enzyme activity and binding to tTERT. To generate the small deletions we used a circularly permuted RNA that changes the location of the wild-type 5′ and 3′ ends while leaving the sequence intact. We designed 27 circular permutations that also deleted 5 to 8 nt between the new 5′ and 3′ ends. Each RNA was generated by T7 RNA transcription and a G residue was added when the new 5′ end did not begin with G to allow for efficient transcription (see Materials and Methods). We designate these RNA mutants CPDs (for circularly permuted deletions).

Telomerase activity and tTERT binding of circularly permuted deletions.

Each telomerase RNA CPD was tested for telomerase activity in vitro. Reconstitution of telomerase was performed with rabbit reticulocyte lysates programmed to express tTERT protein in the presence of telomerase RNA. The tTERT protein also included five repeats of the T7-tag epitope at the amino terminus to allow for immunopurification (see Materials and Methods). Immunopurification from lysates expressing tTERT and different telomerase RNAs was performed with anti-T7-tag antibody-agarose beads followed by the conventional telomerase activity assay with the telomeric primer d(GGGGTT)3. A representative gel showing the activity of each mutant is shown in Fig. 2A. A summary of the relative activity of each CPD from three independent experiments is shown in Fig. 2B. Telomerase activity levels were divided into five categories based on the sum of synthesized products + 7, +13, +25, +31, and +36. Thus, the summary represents changes in both catalytic activity as well as changes in enzyme processivity (Fig. 2B). As negative controls, we also tested two RNAs that were not expected to reconstitute wild-type telomerase activity: a CPD of nt 14 to 40 (CPD14-40) and a 3′ truncation up to nt 108 (t108). CPD14-40 deletes the defined tTERT-binding site (19, 20) and t108 deletes stem-loop IV which has been shown to be required for full enzyme activity (2, 21, 33). As expected these two RNAs reconstituted no or little telomerase activity (Fig. 2A).

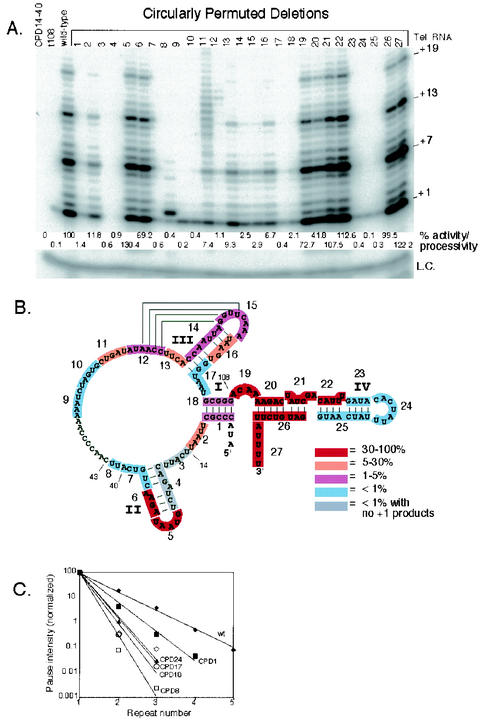

FIG. 2.

Telomerase activity reconstituted with telomerase RNA CPDs. (A) Telomerase activity assays were reconstituted with the telomerase RNAs indicated in the figure. +1, +7, +13, and +19 on the right indicate telomerase extension products from the d(GGGGTT)3 primer. Quantified telomerase activity/processivity is shown below each lane expressed as % of wild-type (see methods). L.C., loading control added for all reactions. (B) Summary of the reconstituted telomerase activity levels of all 27 CPDs shown with the telomerase RNA secondary structure. The highlighted sequence indicates the RNA region deleted in each CPD. The CPD number is shown next to each highlighted RNA sequence from 5′ to 3′ along the RNA. The color indicates the relative level of telomerase activity. Red (50 to 100%) indicates wild-type activity. Orange (5 to 50%), purple (1 to 5%), and light blue (less than 1%) indicate activity less than that of the wild type. Gray indicates no activity, since no products at +1 were observed. Relevant telomerase RNA nucleotide positions are indicated on the figure. (C) Telomerase processivity quantification of selected CPDs. The intensity of each major band (+1, +7, +13, +19, and +25) from telomerase assay in panel A was quantified as described in the Materials and Methods and plotted for each repeat number. The processivity of each mutant is inversely related to the slope of the line.

Many of the CPDs reconstituted wild-type telomerase activity as indicated by the presence of a repeat ladder of telomerase products at + 1, +7, +13, etc. (Fig. 2). This showed that connecting the native wild-type 5′ and 3′ ends and creating new ends at some positions does not disrupt telomerase RNA function as was also recently reported (28). The RNA sequences deleted that had little or no effect on telomerase activity include the distal end of stem-loop II (CPDs 5 and 6), the linker sequence between stem I and stem IV (CPD 19), the proximal end of stem IV (CPDs 20 to 22 and CPD 26) and the 3′ end of the RNA (CPD 27) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, CPDs 3 and 4 and CPD14-40 showed no detectable telomerase products even at + 1. CPDs 3 and 4 lack sequences upstream of and within stem II while CPD14-40 combines both CPDs 3 and 4 and deletes sequences further downstream to residue 40. This region is known to be important for tTERT binding to telomerase RNA (20). CPDs 7 to 10, CPDs 23 to 25, and t108 that include template flanking regions and the distal end of stem-loop IV reconstituted lower activity as judged by the lower intensity of the telomerase products. Further analysis showed these deletions had the most severe disruption of telomerase processivity as well (Fig. 2C). This was judged by plotting the relative intensity of products of +7 and higher compared to products at +1 (Fig. 2C) (9a). The remaining CPDs (1, 2, and 11 to 18) that deleted sequences near or part of stem I, stem-loop III or the pseudoknot region, all had lower and variable levels of activity compared to wild-type and processivity was also modestly affected (Fig. 2A and C). CPD 17 had the most severe processivity defect from this group of deletions comparable to RNA deletions of the distal end of stem-loop IV (Fig. 2C).

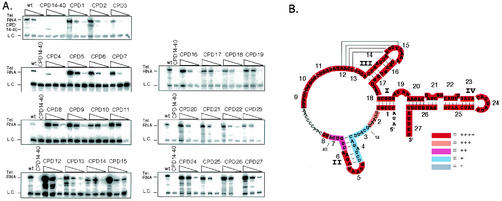

To determine whether the CPDs that reconstituted lower activity was due to a loss of binding to the catalytic tTERT component, we carried out Northern analysis after immunopurification. Binding of each CPD to tTERT in the in vitro transcription and translation lysates was tested in the presence of three different input RNA concentrations, high (100 nM), medium (10 nM) and low (1 nM), to better detect differences in tTERT binding. Wild-type telomerase RNA served as the positive control while CPD14-40, which deletes the high-affinity tTERT-binding site, served as a negative control. At the highest concentration of input RNA (100 nM) all CPDs bound including the CPD14-40 negative control (Fig. 3A). This suggests there may be background binding or low-affinity binding from another RNA region other than the defined tTERT-binding region. However, differences in binding were detected using the middle (10 nM) and low RNA concentrations (1 nM). CPDs 2, 3, 4, and 7 all had reduced levels of tTERT binding (Fig. 3A). CPDs 3 and 4 had the most dramatic reduction while CPDs 2 and 7 had a small yet reproducible reduction in binding. tTERT binding experiments were repeated at least three times for each CPD (summarized in Fig. 3B). Previous evidence has shown substituting positions 15 to 18, unpairing the proximal end of stem II or substituting the conserved GUCA boundary element at positions 37 to 40 reduced telomerase RNA binding to tTERT (19-21). CPD 3 deletes nt 14 to 18, CPD 4 unpairs the proximal end of stem II and CPD 7 deletes the conserved GUCA element. Although CPD 2 deletes nucleotides upstream of the defined tTERT-binding region, in the context of this circular permutation those sequences may be playing a small role in tTERT binding. Thus, we conclude that the low or absent activity seen with, CPDs 2, 3, 4, and 7 is due to loss of functional binding to tTERT. The remaining CPDs showed tTERT binding that was similar to wild-type telomerase RNA (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

tTERT binding of telomerase RNA circularly permuted deletions (CPDs). (A) Wild-type RNA and CPDs tested for tTERT binding are indicated in the figure. Note the CPD14-40 RNA migrates significantly faster than wild-type and CPD RNAs due to the larger deletion of residues. For each set of binding reactions three different RNA concentrations were used (100, 10, and 1 mM from left to right). Except for the top panel (CPDs 1 to 3), wild-type and CPD14-40 telomerase RNAs were only tested at the 10 mM RNA concentration as positive and negative controls. (B) Summary of the tTERT binding to telomerase RNA CPDs compared to wild-type shown with the telomerase RNA secondary structure. The highlighted sequence indicates the RNA region deleted in each CPD. The CPD number is shown next to each highlighted RNA sequence from 5′ to 3′ along the RNA. The color indicates the relative level of tTERT binding. Red (++++) indicates wild-type binding. Orange (+++), purple (++), and light blue (+) indicate binding less than that of wild-type tTERT. Gray indicates no tTERT binding. Relevant telomerase RNA nucleotide positions are indicated on the figure.

Tight tTERT binding to telomerase RNA is not only important for reconstituting telomerase activity but important for efficient telomere sequence fidelity and telomerase processivity (19). The tTERT protein-RNA interaction is important for establishing the 5′ boundary of the template region. To determine if lower processivity observed with CPDs 7 to 10 and CPDs 23 to 25 was due to a lack of 5′ template definition, dATP was included in the telomerase reactions to determine if there is read-through past the template boundary (1, 19). Only CPDs 7 and 8 showed a disruption of the 5′ template boundary in the presence of dATP (24). In fact, CPD 8 showed a 5′ template boundary defect under normal reaction conditions, since its 5′ end starts with GA followed by the template sequence (see methods and materials). The A residue preceding C43 specifies the addition of dTTP which is already present in the telomerase reaction. Since there is no dCTP in the reaction, the G residue cannot be used as a template and products accumulate at +2 (Fig. 2A). This loss of template boundary function for CPDs 7 and 8 is consistent with previous findings that the conserved sequence GUCA is essential to define the 5′ template boundary (1, 19).

Distal stem-loop IV is required for telomerase processivity.

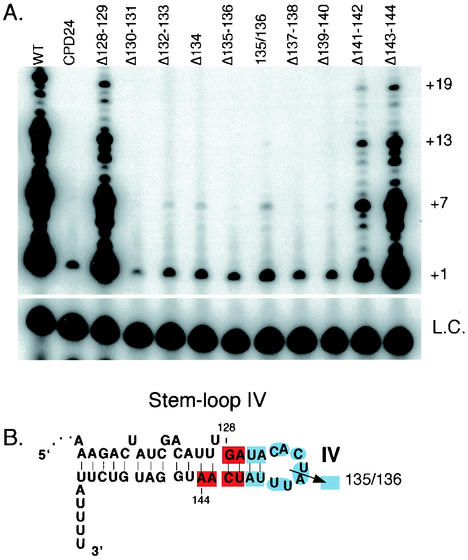

The template-recognition element has been suggested to be required during telomerase translocation, to allow for processivity (28). CPDs 9 and 10 that disrupt this template-recognition element reconstituted telomerase activity with low processivity as expected. In addition to these known elements, CPDs 23 to 25, which delete sequences from the distal end of stem-loop IV, also reconstituted a less processive telomerase. These CPDs did not affect template boundary definition (24), and thus they may also have a direct role in some aspect of telomerase translocation. To define the sequences and/or structure whose deletion is responsible for the low processivity of stem-loop IV, we created smaller CPDs that delete only 1 to 2 nt from positions 128 to 144. Each CPD was reconstituted and tested for telomerase activity (Fig. 4A). Wild-type and CPD 24, which deleted the loop IV sequence from positions 132 to 138, were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. CPDs that removed residues 128 to 129, 141 to 142, and 143 to 144 all reconstituted telomerase activity levels comparable to the wild type, while CPDs of residues 130 to 131, 132 to 133, 134, 135 to 136, 137 to 138, and 139 to 140 reconstituted low activity and were less processive. Finally, a simple disruption of the phosphodiester backbone in loop IV between residues 135 and 136, without deletion of any residues, also reconstituted a less processive telomerase (summarized in Fig. 4B). Previous studies showed that substitution of residues within loop IV can diminish telomerase activity but it was not clear whether a specific structure was required for activity (33). Our data suggest that both the residues at positions 130 to 140 and the structure of loop IV are critical for telomerase function.

FIG. 4.

Telomerase activity reconstituted with small telomerase RNA circularly permuted deletions (CPDs) within stem-loop IV. (A) Telomerase activity assays were reconstituted with wild-type or mutant telomerase RNAs as indicated in the figure. +1, +7, +13, and +19 on the right indicate telomerase extension products from the d(GGGGTT)3 primer. L.C., loading control added to each reaction. (B) Summary of the reconstituted telomerase activity levels for the stem-loop IV CPDs. The residue numbers 128 and 144 indicate the RNA region targeted for smaller deletions. Each highlighted sequence indicates the RNA residues deleted in each smaller CPD. The color indicates the relative level of reconstituted activity; red indicates wild-type or near-wild-type activity, and light blue indicates low and less processive activity, similar to that of CPD 24. The arrow between residues 135 and 136 indicates relative level of reconstituted activity for a circular permutation that breaks the phosphodiester bond between residues 135 and 136 (135/136).

Distal stem-loop IV can promote telomerase processivity in trans.

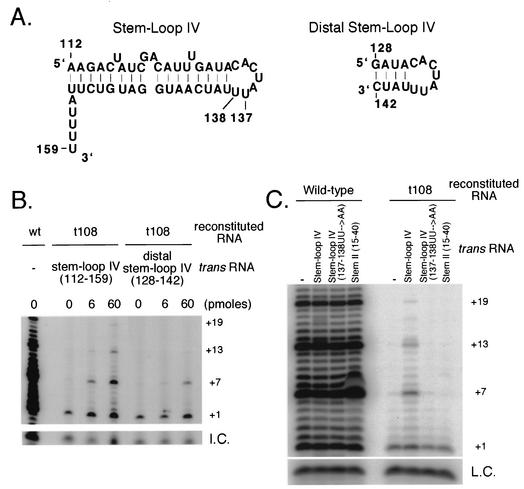

The 3′ telomerase RNA truncation mutant t108 has low telomerase activity that is also less processive likely due to the absence of stem-loop IV (Fig. 2A) (2, 21). Previous studies suggest that the region spanning positions 108 to 111 serves as a flexible linker between two RNA domains (6, 37). Therefore, we reasoned it might be possible to restore telomerase activity with two separate telomerase RNA molecules that comprise each of the two domains. To test this hypothesis, telomerase reconstituted with t108 was immunopurified and then assayed for telomerase activity in the presence of stem-loop IV nt 112 to 159 or nt 128 to 142 (Fig. 5A). Activity reconstituted with t108 RNA in the absence of stem-loop IV RNAs was low and less processive showing products only at +1. However, telomerase processivity was stimulated in a dose dependent manner upon the addition of increasing amounts of stem-loop IV RNA nt 112 to 159 or nt 128 to 142 in trans to the telomerase reaction (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Stem-loop IV stimulates telomerase processivity. (A) Secondary structures of stem-loop IV nt 112 to 159 (left) and distal stem-loop IV nt 128 to 142 (right) are shown. Residue numbers are indicated on the structures. (B) Telomerase reconstituted with wild-type (wt) or t108 telomerase RNA was assayed for telomerase activity in the presence of 0, 6, or 60 pmol of stem-loop IV RNA (nt 112 to 159) or distal stem-loop IV RNA (nt 128 to 142). +1, +7, +13, and +19 on the right indicate telomerase extension products from the d(GGGGTT)3 primer. I.C., internal control for loading. (C) Telomerase reconstituted with wild-type or t108 telomerase RNA was assayed for telomerase activity alone or in the presence of 500 pmol of stem-loop IV, stem-loop IV (137-138 UU→AA) double point mutant or stem II nt 15 to 40. +1, +7, +13, and +19 on the right indicate telomerase extension products from the d(GGGGTT)3 primer. L.C., loading control for telomerase reactions.

To test the specificity of stem-loop IV RNA stimulation of telomerase processivity, we added stem-loop IV (nt 112 to 159) in trans that contained a double point mutation at positions 137 and 138 (137-138 UU→AA) to the reaction (Fig. 5C). In the context of the full-length RNA, this mutation decreased telomerase activity similar to the activity reconstituted with t108 (Fig. 2A) and (33). The addition of a stem-loop IV containing this double point mutant in trans did not stimulate telomerase processivity. Similarly, an unrelated small RNA from stem II (nt 15 to 40) also did not stimulate processivity when added to the t108 reconstituted telomerase reaction (Fig. 5C). These results suggest specific residues in the proper structural context within loop IV are required for telomerase processivity.

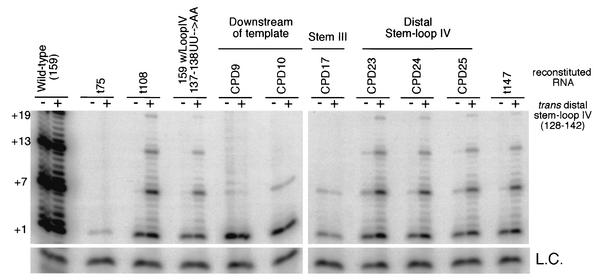

Stem-loop IV in trans rescues a specific subset of CPDs with low processivity.

Distal stem-loop IV likely stimulates processivity through interactions with another region of telomerase RNA, tTERT, the telomere substrate or any combination of these components. To investigate this further, we first sought to examine whether the addition of distal stem-loop IV (nt 128 to 142) in trans would rescue the processivity defects or low activity observed with other CPDs. All CPDs that disrupt the distal stem-loop IV (CPDs 23 to 25) were rescued with the addition of distal stem-loop IV in trans (Fig. 6). The stem-loop IV double point mutant (137-138 UU→AA) was also rescued. In contrast, the less processive telomerase activity reconstituted with CPDs 9 and 10, which disrupts the telomerase RNA template-recognition element (28), was not rescued by the addition of distal stem-loop IV.

FIG. 6.

Stem-loop IV in trans rescues a specific subset of CPDs with low processivity. (A) Telomerase was reconstituted with various telomerase RNA CPDs and mutants as indicated in the figure. +1, +7,+13, and +19 on the left indicate telomerase extension products from the d(GGGGTT)3 primer. For telomerase CPDs, the corresponding RNA region is indicated above each deletion or group of deletions. Each reconstituted telomerase was assayed for telomerase activity in the absence or presence of 500 pmol of distal stem-loop IV (nt 128 to 142). L.C., loading control for telomerase reactions.

It has been proposed that stem-loop IV functions to promote pseudoknot formation of telomerase RNA to yield an active telomerase by RNA-RNA interactions (33). To address this possibility, we examined whether the addition of stem-loop IV in trans would increase the low telomerase activity of truncation mutant t75 or the less processive activity of RNA mutant CPD 17. Both of these mutants delete part of stem III that forms the pseudoknot structure. The addition of stem-loop IV in trans did not rescue the decreased activity in those mutants (Fig. 6). Interestingly, the RNA pseudoknot disruptions also resulted in lower processivity than wild-type (Fig. 2A and C). This suggests that stem III in addition to stem-loop IV plays a role in processivity.

CPDs 20 to 22 and CPD 26, which removed sequences of the proximal end of stem IV, all reconstituted wild-type or near wild-type levels of telomerase activity. This suggests the residues within stem IV are not critical for function. However, a 3′ deletion that removed residues up to position 147 (t147) did not reconstitute processive telomerase activity despite having distal stem-loop IV intact. The addition of distal stem-loop IV in trans did stimulate of processivity when reconstituted with t147 (Fig. 6). CPD 26 disrupted the same sequence within stem IV as t147. However, wild-type levels of telomerase activity were reconstituted with CPD 26 and not with t147. Thus, it is likely that the structure and not the sequence of this region is important. t147 creates an unpaired stem IV that may mispair with some other region of the RNA and thus interfere with the position or function of the distal end of stem-loop IV. Addition of distal stem-loop IV on a separate molecule relieves that restriction, suggesting that the flexibility of stem IV is essential for function. Whereas in CPD 26, the correct folding of the RNA maintains the structure of stem IV. CPD 21 deletes the conserved GA bulge. As previously described, the bulge structure and not the sequence is required for function (2, 33). CPD 21 may maintain the flexibility of this region by opening the structure with 5′ and 3′ ends. Thus, these data suggest specific residues of the proximal end of stem IV are not required for function but structural integrity of stem IV is important possibly to orient the end of stem-loop IV into a functional conformation.

DISCUSSION

We used circularly permuted deletions (CPDs) of the Tetrahymena telomerase RNA to define regions of the RNA that are important for enzyme activity. Loss of function in this assay may occur because the sequences deleted are required for catalysis or for forming a structure required for catalysis. Alternatively, the sequences deleted may be required for binding to tTERT. It is also possible that some of the CPDs may not fold properly. However, our analysis is consistent with previously published data on the functional regions of the RNA (2, 19-21, 28, 33). This suggests that most if not all of the CPD RNAs are folding properly. Hence, the telomerase activity levels reconstituted with the CPD mutants are directly attributable to the function of residues deleted.

The analysis of the set of CPDs highlighted the role of stem IV in telomerase processivity. Stem-loop IV added in trans on a separate RNA molecule will stimulate the processivity of an RNA defective in this region. The loop IV sequence of this region is 100% conserved in Tetrahymena species (36), suggesting that it plays an important role in enzyme function. Stem-loop IV may function through interactions with tTERT or with other regions of telomerase RNA including the template recognition element, to stimulate processivity (28). Alternatively stem-loop IV may stimulate processivity by interactions directly with the telomeric substrate.

This stem-loop IV may be functionally analogous to the CR4-CR5 region of vertebrate telomerase. In human or mouse telomerase the pseudoknot domain is not sufficient for activity, but addition of the CR4-CR5 domain in trans stimulates catalysis (3, 4, 11, 29, 34). The Tetrahymena stem-loop IV is located in a similar location in the secondary structure as the CR4-CR5 region of the vertebrate telomerase RNA (10). Furthermore, within CR4-CR5 there is a small stem-loop structure, P6.1, that is critical for telomerase activity in vitro and in vivo (11).

While stem-loop IV shares structural similarities with the vertebrate CR4-CR5 domain, and can act in trans, there are also some differences in the function of these regions between the species. Stem-loop IV stimulates telomerase processivity while CR4-CR5 is required for catalytic activity. The CR4-CR5 domain binds to human or mouse TERT directly independent of the pseudoknot domain (3, 4, 11, 29, 34). We tested stem-loop IV binding to tTERT and found only a very low-affinity interaction although, the double point mutant 137-138 UU→AA of stem-loop IV abolished this low-affinity interaction (data not shown) indicating sequence specificity. This low-affinity interaction may explain the requirement for a large excess of the stem-loop IV RNA to stimulate processivity in trans.

The structural similarities combined with the significant functional differences suggest that stem-loop IV and the CR4-CR5 domain may be ancestrally related but that their functions have diverged during evolution. Alternatively, since the 3′ ends of Tetrahymena, vertebrate, and yeast telomerase RNAs differ significantly (10, 30, 32), it is possible that recombination generated species with telomerase RNAs containing different 3′ ends. To distinguish between these models, and to understand the functional relationships of the stem-loop IV and CR4-CR5 domain, it will be essential to determine the telomerase RNA secondary structure from yeast and many other species that may reveal clues to the evolutionary history of the telomerase RNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Autexier, C., and C. W. Greider. 1995. Boundary elements of the Tetrahymena telomerase RNA template and alignment domains. Genes Dev. 9:2227-2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autexier, C., and C. W. Greider. 1998. Mutational analysis of the Tetrahymena telomerase RNA: identification of residues affecting telomerase activity in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:787-795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bachand, F., I. Triki, and C. Autexier. 2001. Human telomerase RNA-protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:3385-3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beattie, T. L., W. Zhou, M. O. Robinson, and L. Harrington. 2000. Polymerization defects within human telomerase are distinct from telomerase RNA and TEP1 binding. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:3329-3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beattie, T. L., W. Zhou, M. O. Robinson, and L. Harrington. 1998. Reconstitution of human telomerase activity in vitro. Curr. Biol. 8:177-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya, A., and E. H. Blackburn. 1994. Architecture of telomerase RNA. EMBO J. 13:5521-5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackburn, E. H. 2001. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 106:661-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blasco, M. A., W. Funk, B. Villeponteau, and C. W. Greider. 1995. Functional characterization and developmental regulation of mouse telomerase RNA. Science 269:1267-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryan, T. M., and T. R. Cech. 1999. Telomerase and the maintenance of chromosome ends. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11:318-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Bryan, T. M., K. J. Goodrich, and T. R. Cech. 2000.. A mutant of Tetrahymena telomerase reverse transcriptase with increased processivity. J. Biol. Chem. 31:24199-24207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, J. L., M. A. Blasco, and C. W. Greider. 2000. Secondary structure of vertebrate telomerase RNA. Cell 100:503-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen, J. L., K. K. Opperman, and C. W. Greider. 2002. A critical stem-loop structure in the CR4-CR5 domain of mammalian telomerase RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:592-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins, K., and L. Gandhi. 1998. The reverse transcriptase component of the Tetrahymena telomerase ribonucleoprotein complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:8485-8490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins, K., and C. W. Greider. 1993. Tetrahymena telomerase catalyzes nucleolytic cleavage and nonprocessive elongation. Genes Dev. 7:1364-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng, J., W. D. Funk, S.-S. Wang, S. L. Weinrich, A. A. Avilion, C.-P. Chiu, R. R. Adams, E. Chang, R. C. Allsopp, J. Yu, S. Le, M. D. West, C. B. Harley, W. H. Andrews, C. W. Greider, and B. Villeponteau. 1995. The RNA component of human telomerase. Science 269:1236-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greider, C. W. 1991. Telomerase is processive. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:4572-4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greider, C. W., and E. H. Blackburn. 1989. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature 337:331-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington, L., and M. O. Robinson. 2002. Telomere dysfunction: multiple paths to the same end. Oncogene 21:592-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrington, L. A., and C. W. Greider. 1991. Telomerase primer specificity and chromosome healing. Nature 353:451-454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai, C. K., M. C. Miller, and K. Collins. 2002. Template boundary definition in Tetrahymena telomerase. Genes Dev. 16:415-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai, C. K., J. R. Mitchell, and K. Collins. 2001. RNA binding domain of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:990-1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Licht, J. D., and K. Collins. 1999. Telomerase RNA function in recombinant Tetrahymena telomerase. Genes Dev. 13:1116-1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lingner, J., L. L. Hendrick, and T. R. Cech. 1994. Telomerase RNAs of different ciliates have a common secondary structure and a permuted template. Genes Dev. 8:1984-1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lingner, J., T. R. Hughes, A. Shevchenko, M. Mann, V. Lundblad, and T. R. Cech. 1997. Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science 276:561-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason, D. X. 2002. Biochemical characterization of Tetrahymena telomerase. Ph. D. thesis. The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Md.

- 25.McCormick-Graham, M., and D. P. Romero. 1995. Ciliate telomerase RNA structural features. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:1091-1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCormick-Graham, M., and D. P. Romero. 1996. A single telomerase RNA is sufficient for the synthesis of variable telomeric DNA repeats in ciliates of the genus Paramecium. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1871-1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McEachern, M. J., and E. H. Blackburn. 1995. Runaway telomere elongation caused by telomerase RNA gene mutations. Nature 376:403-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller, M. C., and K. Collins. 2002. Telomerase recognizes its template by using an adjacent RNA motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6585-6590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell, J. R., and K. Collins. 2000. Human telomerase activation requires two independent interactions between telomerase RNA and telomerase reverse transcriptase. Mol. Cell 6:361-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero, D. P., and E. H. Blackburn. 1991. A conserved secondary structure for telomerase RNA. Cell 67:343-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shippen-Lentz, D., and E. H. Blackburn. 1990. Functional evidence for an RNA template in telomerase. Science 247:546-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer, M. S., and D. E. Gottschling. 1994. TLC1: Template RNA component of Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomerase. Science 266:404-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sperger, J. M., and T. R. Cech. 2001. A stem-loop of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA distant from the template potentiates RNA folding and telomerase activity. Biochemistry 40:7005-7016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tesmer, V. M., L. P. Ford, S. E. Holt, B. C. Frank, X. Yi, D. L. Aisner, M. Ouellette, J. W. Shay, and W. E. Wright. 1999. Two inactive fragments of the integral RNA cooperate to assemble active telomerase with the human protein catalytic subunit (hTERT) in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:6207-6216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinrich, S. L., R. Pruzan, L. Ma, M. Ouellette, V. M. Tesmer, S. E. Holt, A. G. Bodnar, S. Lichtsteiner, N. W. Kim, J. B. Trager, R. D. Taylor, R. Carlos, W. H. Andrews, W. E. Wright, J. W. Shay, C. B. Harley, and G. B. Morin. 1997. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component hTR and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat. Genet. 17:498-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye, A. J., and D. P. Romero. 2002. Phylogenetic relationships amongst tetrahymenine ciliates inferred by a comparison of telomerase RNAs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:2297-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaug, A. J., and T. R. Cech. 1995. Analysis of the structure of Tetrahymena nuclear RNAs in vivo: telomerase RNA, self-splicing rRNA and U2 snRNA. RNA 1:363-374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]