Abstract

The interbacterial communication system known as quorum sensing (QS) utilizes hormone-like compounds referred to as autoinducers to regulate bacterial gene expression. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) serotype O157:H7 is the agent responsible for outbreaks of bloody diarrhea in several countries. We previously proposed that EHEC uses a QS regulatory system to “sense” that it is within the intestine and activate genes essential for intestinal colonization. The QS system used by EHEC is the LuxS/autoinducer 2 (AI-2) system extensively involved in interspecies communication. The autoinducer AI-2 is a furanosyl borate diester whose synthesis depends on the enzyme LuxS. Here we show that an EHEC luxS mutant, unable to produce the bacterial autoinducer, still responds to a eukaryotic cell signal to activate expression of its virulence genes. We have identified this signal as the hormone epinephrine and show that β- and α-adrenergic antagonists can block the bacterial response to this hormone. Furthermore, using purified and in vitro synthesized AI-2 we showed that AI-2 is not the autoinducer involved in the bacterial signaling. EHEC produces another, previously undescribed autoinducer (AI-3) whose synthesis depends on the presence of LuxS. These results imply a potential cross-communication between the luxS/AI-3 bacterial QS system and the epinephrine host signaling system. Given that eukaryotic cell-to-cell signaling typically occurs through hormones, and that bacterial cell-to-cell signaling occurs through QS, we speculate that QS might be a “language” by which bacteria and host cells communicate.

Keywords: enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli, quorum sensing, type III secretion, epinephrine

EHEC O157:H7 is responsible for major outbreaks of bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) throughout the world. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) colonizes the large bowel and causes a lesion on intestinal epithelial cells termed attaching and effacing (AE), characterized by the destruction of the microvilli and rearrangement of the cytoskeleton to form pedestal-like structures that cup the bacteria individually (1). The genes involved in the formation of the AE lesion are contained on the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (2), which is present in EHEC but absent in commensal and K-12 E. coli. The LEE contains genes encoding a type III secretion system, an adhesin (intimin), and a receptor (Tir) for this adhesin (3). The majority of the LEE genes are organized in five operons (LEE1–5). The first gene of the LEE1 operon encodes a transcriptional activator (Ler) essential for the expression of the LEE genes (4, 5). EHEC also produces a potent Shiga toxin (Stx) responsible for the major symptoms of hemorrhagic colitis and HUS (1). We recently reported that several virulence-associated genes in EHEC such as the LEE genes, Stx genes, and the flagella regulon are activated through the bacterial cell-to-cell signaling mechanism known as quorum sensing (QS) (6, 7). This QS signaling is used for bacterial interspecies communication; the autoinducer (referred to as autoinducer 2 or AI-2) is a furanosyl borate diester (8), and the enzyme responsible for its synthesis is encoded by the luxS gene (9). LuxS is an enzyme involved in the detoxification of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), and it converts ribosehomocysteine into homocysteine and 4,5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentanedione, the precursor of AI-2 (10).

QS regulatory cascades have been extensively studied in organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Vibrio harveyi and have proven to be very complex (11, 12). Regarding EHEC, we recently described two novel regulatory systems in its QS cascade named QS E. coli regulator A (QseA) and QseB and C (13, 14). QseA activates transcription of the LEE genes, and an EHEC qseA mutant had a striking reduction in type III secretion (13). QseBC is a two-component system that is involved in activation of flagella and motility genes (14).

In this study, we demonstrate that the LuxS enzyme is involved in the synthesis of yet another autoinducer (AI-3), which is the actual signal activating transcription of the LEE and flagella genes. Our results also suggest that AI-3 cross-talks with the mammalian hormone epinephrine (Epi), because a luxS mutant has its virulence phenotypes restored by exogenous AI-3 and/or Epi, and that both α- and β-adrenergic antagonists are able to block this signaling. Taken together these results suggest that QS, a bacterial cell-to-cell signaling system, may be also involved in bacterium–host communication.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Plasmids. EHEC O157:H7 strain 86-24 was isolated from an outbreak of bloody diarrhea (15). Strain VS94 is a luxS isogenic mutant of 86-24 and VS95 is VS94 complemented with pVS84, which is luxS cloned into pACYC177 (7). All E. coli strains were grown aerobically at 37°C in LB or DMEM. Details on strains and plasmids can be found in Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Reporter Gene Assays. Transcriptional fusions with lacZ were constructed, and strains containing the operon::lacZ fusions were grown in fresh or preconditioned (PC) medium at 37°C as described in ref. 6. These assays were also performed by growing these strains in the presence of 50 μM Epi or norepinephrine (NE), and 50 and 500 μM of phentolamine (PE) and/or propranolol (PO), purified AI-2, AI-3, or in vitro-synthesized AI-2 (10 μM and 100 μM). Cultures were diluted 1:10 in Z buffer and assayed for β-galactosidase activity by using o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as a substrate as described (16). Details on the purification of AI-2 and AI-3 can be found in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

In Vitro Synthesis of AI-2. In vitro synthesis of AI-2 was performed as described (10). Briefly, the luxS and pfs genes were amplified from E. coli MG1655 with Pfx polymerase (Invitrogen) by using primers LuxSFHis (GGTACCCCGTTGTTAGATAGCTTCAC), LuxSRHis (AAGCTTCTAGATGTGCAGTTCCTGCAACT), PfsFHis (GGTACCATCGGCATCATTGGTGCA), and PfsRHis (AAGCTTTTAGCCATGTGCAAGTTTCTGC), and cloned into pQE30 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) digested with KpnI and HindIII, generating plasmids pVS212 and pVS214, respectively. Both His-tagged Pfs and LuxS were purified by using a nickel resin (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In vitro synthesis of AI-2 was performed with 1 mM S-adenosylhomocysteine (Sigma), 1 mg/ml His-LuxS, and 1 mg/ml His-Pfs in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 and 37°C for 1 h. The AI-2 was size-fractionated by using a Centrifuge Biomax-5 column (Millipore). Quantification of AI-2 was scored indirectly through quantification of homocysteine produced through the reaction described above by using Ellman's test for the sulfhydryl group as described (10).

V. harveyi Luminescence Assay. The presence of AI-2 in PC medium was assayed by using the V. harveyi BB170 (luxN::Tn5) reporter strain, which responds only to AI-2 (17). The luminescence assays were performed as described (17), and the assays were read in a Wallac (Gaithersburg, MD) 1420 multilabel counter.

Western Blotting. Secreted proteins from EHEC 86-24, VS94, and VS95 strains were prepared as described by Jarvis et al. (18) after growing these strains to an OD600 of 1.0 in DMEM medium at 37°C, and in the presence of 50 μM Epi or NE and/or 500 μM PE or PO, 100 μM in vitro synthesized AI-2, and 4 μM purified AI-3. Western blotting procedures were performed as previously described and probed with polyclonal antisera directed against secreted proteins (18) or Tir.

Fluorescent Actin Staining (FAS) Test. FAS tests were performed as initially described by Knutton et al. (19). Briefly, bacterial strains were incubated with HeLa cells for6hat 37°C and 5% CO2, after which epithelial cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton and treated with FITC-phalloidin or Alexa-phalloidin to visualize the accumulation of actin beneath and around the bacteria attached to the HeLa cells (which is the hallmark of AE lesions). The bacteria were stained by using either propidium iodide or anti-O157 antiserum conjugated with FITC.

Results

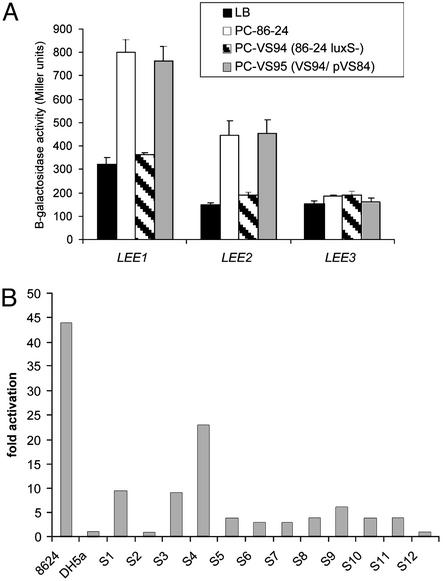

Activation of the LEE Genes by the LuxS/AI-2 QS System. To confirm the role of QS in the activation of the LEE genes, we generated an EHEC luxS mutant (VS94). We measured transcription of the LEE genes by using transcriptional fusions of the LEE promoters to a lacZ reporter introduced into the chromosome of an E. coli K-12 strain. As expected, culture supernatants from the EHEC luxS mutant (which do not contain AI-2) failed to activate transcription of the LEE genes, whereas culture supernatants from either the WT or complemented strains activated transcription of the LEE genes (Fig. 1A). We observed QS activation of transcription of LEE1 and LEE2 operons in a K-12 background, suggesting that the transcriptional regulators involved in this activation are shared between EHEC and K-12. We recently described one such activator, QseA (13), which activates transcription of Ler, which then in turn activates transcription of the other LEE genes (6). QS activation of transcription of LEE3 and LEE5 does not occur in a K-12 background because of the absence of Ler (6). We have proposed that activation of the LEE genes by the AI-2/luxS QS system would occur in response to the AI-2 produced by the intestinal flora, and that this intraintestinal signaling could be one explanation for the low infectious dose of EHEC (6). To support this hypothesis, we examined stool specimens from 12 healthy individuals and detected AI-2 activity [using the V. harveyi AI-2 luminescence assay (17)] in 10 of 12 filtrates from normal human stools (Fig. 1B), indicating that AI-2 is normally present in the human intestine. We were also able to detect AI-2 activity in culture supernatants from human bacterial flora (Table 1) that have been cultured in an in vitro artificial intestine model (ref. 20; described in Supporting Text). These bacterial flora supernatants also activated transcription of a LEE1::lacZ reporter fusion (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Transcription of LEE::lacZ fusions integrated into the K-12 chromosome in fresh medium (LB) and medium preconditioned by growth of WT strain 86-24, the luxS mutant (VS94), or the complemented mutant (VS95). (B) Induction of luminescence in V. harveyi strain BB170 by fecal filtrates from volunteers from the Center for Vaccine Development at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. As positive and negative controls we used PC medium with 86-24 and DH5α (which does not produce AI-2), respectively.

Table 1. Activation of LEE1 transcription and bioluminescence in V. harveyi by intestinal flora.

| Media | LEE1::lacZ transcription* | Luminescence V. harveyi BB170† |

|---|---|---|

| SHIME | 239 ± 23 | 1 ± 0.1 |

| PC§-SHIME-flora | 2,910 ± 100 | 38 ± 3.5 |

| PC-86-24 | 1,367 ± 209 | 78 ± 20 |

| PC-DH5α | 220 ± 20 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

Expressed in fold-induction of bioluminescence compared with media alone.

‡ SHIME media from the artificial intestine (Supporting Text)

LEE1::lacZ transcription is expressed in Miller units of β-galactosidase.

BB170 is a V. harveyi luxN::Tn5 that only produces light in response to AI-2.

PC, media preconditioned with the intestinal flora, EHEC strain 86-24 (which produces AI-2), or K-12 strain DH5α (which does not produce AI-2).

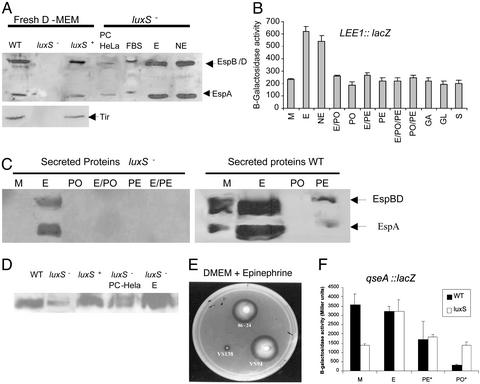

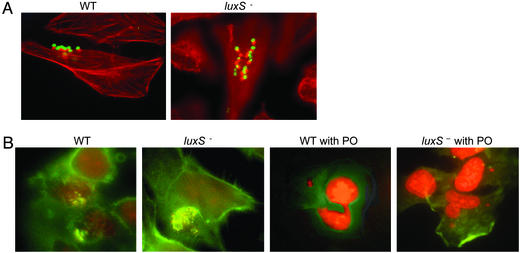

Activation of Type III Secretion by QS and Host Factors. Because transcription of the genes encoding the EHEC type III secretion system is activated through the luxS/AI-2 QS system, we examined the effect of a luxS mutation on type III secretion. We could not detect the type III-secreted proteins EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir in the supernatant of the EHEC luxS mutant when using polyclonal antiserum raised against total secreted proteins (18) or Tir (21), but, as expected, we were able to detect these proteins in the supernatants of both the WT and luxS-complemented strains (Fig. 2A). These results suggested that type III secretion may be abrogated in the luxS mutant in vitro, and, based on these data, we expected the luxS mutant to be unable to produce AE lesions on cultured HeLa epithelial cells. However, the luxS mutant was still able to produce AE lesions on HeLa cells, indistinguishable from WT (Fig. 3). This latter result led us to investigate whether there was yet another level of regulation either through bacterial–epithelial cell contact or through signaling. Because QS in bacteria is a cell-to-cell signaling system, we hypothesized that a eukaryotic signaling compound could complement the bacterial mutation. This hypothesis was supported by the fact that type III secretion was restored in the luxS mutant with medium that had been incubated with HeLa cells for 24 h (PC-HeLa) and size-fractionated for compounds smaller than 1 kDa (Fig. 2 A). These results suggested that there was some sort of signaling occurring between the epithelial cell and the bacterial cell, resulting in activation of type III secretion, and that this signaling could substitute for the AI-2/luxS QS regulation.

Fig. 2.

(A) Western blot of type III-secreted proteins from strains 86-24, VS94, and VS95 in fresh DMEM; secreted proteins from VS94 in DMEM preconditioned with HeLa cells, nonpreconditioned DMEM + 10% FBS, DMEM + 50 μM of Epi (E), or 50 μM of NE. (B) β-galactosidase activity of a LEE1::lacZ chromosomal fusion in K-12 grown in fresh DMEM to an OD600 ≤ 0.2 in the presence of 50 μM Epi, NE, PO, PE, gastrin (GA), galanin (GL), and secretin (S) or with no additives (M). (C) Western blot of secreted proteins from VS94 and 86-24 grown in fresh DMEM (M), DMEM + 50 μM Epi, DMEM + 500 μM PO, DMEM + 50 μM Epi and 500 μM PO (E/PO), DMEM + 500 μM PE, and DMEM + 50 μM Epi and 500 μM PE (E/PE). (D) Western blot of flagellin from 86-24, VS94, VS95, VS94 + PC medium with HeLa cells, and VS94 + 50 μM of Epi. (E) Motility in DMEM + 50 μM Epi of EHEC 86-24, luxS (VS94), and qseC (VS138) mutants. (F) Transcription of qseA::lacZ in fresh medium (M) and in DMEM + 50 μM of Epi, PE, and PO in WT and luxS– backgrounds. *, Transcription in the luxS mutant with PE and PO was performed in the presence of Epi; no Epi was added to the WT strain.

Fig. 3.

(A) Formation of AE lesions, by using the fluorescein actin staining (FAS) test, by WT and luxS mutant in HeLa cells. The actin cytoskeleton is stained in red with Alexa-phalloidin, and EHEC is stained in green with anti-O157 antiserum conjugated with FITC. (B) FAS test of the WT and luxS mutant without and with PO (500 μM). The actin cytoskeleton is stained in green with FITC-phalloidin, and EHEC is stained in red with propidium iodide.

Eukaryotic cell-to-cell signaling occurs through hormones. There are three major groups of endocrine hormones: polypeptide hormones, steroid hormones, and hormones derived from the amino acid tyrosine, which include the catecholamines NE and Epi (22). Two of the Gram-negative bacterial autoinducers [acylhomoserine lactones (AHLs) and the AI-2] are also derived from amino acid metabolism (12). NE has been demonstrated to induce bacterial growth (23) and to be taken into bacteria (24). Using purified Epi and NE, we observed that both hormones (in physiological concentrations, 50 μM) activated type III secretion in the luxS mutant and transcription of LEE1 (Fig. 2 A and B), indicating that both of these host hormones are involved in bacteria–host cell signaling. One report suggested that epithelial cells could synthesize and release catecholamines (25). However the source of Epi and NE was not the epithelial cells, because inhibitors of both synthesis and release of these catecholamines did not abrogate this signaling (data not shown). Rather, both catecholamines are present in the FBS used to grow the epithelial cells, because DMEM + 10% FBS can restore type III secretion in the luxS mutant (Fig. 2A), and because we detected the presence of 36 μM of Epi in DMEM + 10% FBS by using a commercial ELISA for Epi detection (IBL, Hamburg, Germany).

It has been shown that there is a considerable amount of Epi and NE in the human gastrointestinal tract (26), and that Epi induces chloride and potassium secretion in the colon (27). The neuronally mediated response to Epi can be suppressed in the distal colon by the nonselective β-adrenergic receptor antagonist PO and in the proximal colon by the nonselective α-adrenergic receptor antagonist PE (27). Because the luxS mutant responded to Epi, we investigated whether we could block this response by using either PO or PE. Type III secretion and transcription of the LEE genes in the luxS mutant were no longer activated by Epi in the presence of either PO or PE (Fig. 2 C and B). Neither PO nor PE alone had any effect on these phenotypes (Fig. 2 C and B). Finally, the presence of PO prevented the formation of AE lesions on epithelial cells with the luxS mutant, further suggesting that Epi was responsible for this cross-talk, and that we can specifically block it by using adrenergic receptor antagonists (Fig. 3B). Other intestinal hormones (gastrin, galanin, and secretin) did not activate transcription of LEE1, implying that they are not involved in this signaling (Fig. 2B).

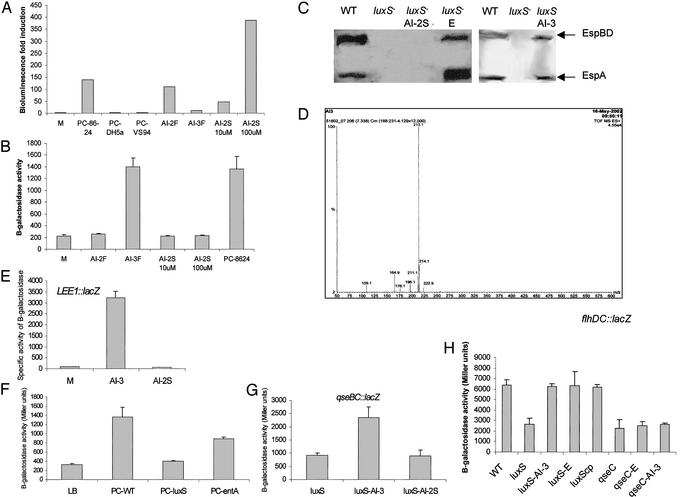

AI-2 Is Not the Autoinducer Responsible for Activation of the LEE Genes. Bacterial–eukaryotic cell communication appears to be crucial for the activation of the LEE genes in EHEC and seems to have a connection with the luxS/AI-2 QS system. At the time we initiated these studies, purified AI-2 was unavailable and we therefore proceeded to purify this compound (details may be found in Supporting Text). The subsequent report of the AI-2 structure (8) showed that AI-2 (a furanone), NE, and Epi (catecholamines) have very different structures (Fig. 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Although 2,3-dihydroxy-4,5-pentanedione (an AI-2 precursor) is known to react with amines and could thus react with these catecholamines, our data suggested that this cross-talk is due to yet another bacterial autoinducer. Unlike AI-2, which is very polar and does not bind to C-18 Sep Pack columns, catecholamines bind to these columns and can only be eluted with organic solvents. The fraction containing AI-2 activated luminescence in V. harveyi (Fig. 4A) but did not activate transcription of LEE1 (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we synthesized AI-2 in vitro, and the in vitro-synthesized AI-2 [active in the V. harveyi luminescence test (Fig. 4A)] failed to activate transcription of LEE1 and to restore type III secretion in the luxS mutant (Fig. 4 B and C). In contrast, the fraction eluted with methanol (AI-3F) activated LEE1 transcription but did not activate luminescence in V. harveyi (Fig. 4 A and B). Taken together, these results suggest that there is another autoinducer in this extract that is retained in the column and released with methanol, and that this is the autoinducer, which we have named AI-3, that is involved in activation of the LEE genes. A small amount of AI-3 has been purified (see Supporting Text), and a 4-μM portion of this fraction activated transcription of LEE1 34-fold (Fig. 4E) and restored type III secretion to the luxS mutant (Fig. 4C). Electrospray mass spectrometry analysis of the AI-3 fraction showed a major peak with a mass of 213.1 Da and minor peaks at 109.1, 164.9, 176.1, 196.1, 211.1, 214.1, and 222.9 Da (Fig. 4D), which is different from AI-2 (192.9 Da; ref. 8), Epi (183.2 Da), and NE (169.2 Da), suggesting that AI-3 is a novel compound. Purifying enough AI-3 for further analysis has proved to be quite a challenging task, and we are attempting to scale up purification to determine the chemical structure of this compound.

Fig. 4.

(A) V. harveyi AI-2 luminescence assay in the presence of the purified fractions containing AI-2 (AI-2F) and AI-3 (AI-3F), in vitro synthesized AI-2 (AI-2S) (10 and 100 μM), and PC medium prepared with 86-24 (positive control), DH5α, and VS94. (B) Transcription of LEE1::lacZ in fresh medium (M), in the presence of the purified fractions AI-2 and AI-3, and in in vitro synthesized AI-2. (C) Western blot of secreted proteins from strain 86-24, VS94, VS94 + 100 μM of AI-2S, VS94 + 50 μM of Epi (Sigma), and VS94 + 4 μM of AI-3. (D) Electrospray mass spectrometry of the AI-3 purified fraction. (E) Transcription of LEE1::lacZ in fresh medium (M), in the presence of AI-3 (4 μM), and in AI-2S (100 μM). (F) Transcription of LEE1::lacZ in fresh medium (LB), PC medium with strain 86-24 (PC-WT), PC medium with strain VS94 (PC-luxS), and PC medium with an E. coli entA mutant (PC-entA). (G) Transcription of qseBC::lacZ in a luxS mutant in the presence of AI-3 (4 μM) and AI-2S (100 μM). (H) Transcription of flhDC::lacZ in a luxS or qseC mutant background in the presence of AI-3 (4 μM) or Epi (E; 50 μM).

Because E. coli is known to produce the catechol enterobactin that is involved in iron uptake, we wanted to rule out the possibility that the observed signaling was due to enterobactin. PC medium derived from an entA mutant (unable to produce enterobactin) still activates transcription of a LEE1::lacZ fusion (Fig. 4F), thereby ruling out enterobactin involvement in this signaling. As a further indication that this signaling is not due to enterobactin or iron uptake, we observed that an EHEC tonB mutant had no defect in type III secretion, which is a hallmark of QS regulation in EHEC, and that Epi was still able to induce type III secretion in a tonB mutant (data not shown).

Another EHEC phenotype regulated by QS is flagella expression (7, 14). The flagella regulon is controlled by QS through the two-component system QseBC (14). Transcription of qseBC has been described to be controlled by QS through the luxS system (14); we now show that transcription of qseBC is also activated by AI-3 and not AI-2 (Fig. 4G).

AI-3 May Cross-Talk with Epi. Epi can substitute for AI-3 to activate transcription of the LEE genes, type III secretion, and AE lesions on HeLa cells (Figs. 2 and 3). Taken together, these results suggest that AI-3 and Epi cross-talk and that they may use the same signaling pathway. We recently described that QseA (13) is itself under QS regulation and that it activates transcription of the LEE genes. Using a qseA::lacZ transcriptional fusion, we were able to show that qseA transcription is induced by Epi in a luxS– background (Fig. 2F). Both adrenergic antagonists, PE and PO, inhibited the Epi-induced transcription of qseA in a luxS– background. In a WT background (in the absence of Epi) qseA transcription was also inhibited by both PE and PO, with PO being the best inhibitor. Finally, both PE and PO were able to inhibit type III secretion of WT EHEC, with PO having the most striking effect (Fig. 2C). In agreement with this phenotype, PO also inhibited AE lesion formation by WT EHEC in HeLa cells (Fig. 3F).

Concerning other QS-regulated phenotypes, Epi also induced expression of flagella (Fig. 2D). The flagella regulon is controlled by QS through QseBC, which activates transcription of the flagellar master activator flhDC (14). We previously reported (14) that a mutant in the QseC sensor was unable to respond to bacterial autoinducers given exogenously as PC medium. Motility of a luxS mutant can be restored by bacterial autoinducers present in PC medium (14) and Epi (Fig. 2E), whereas a qseC mutant is unable to respond to both AI-3 and Epi (Fig. 2E; ref. 14). As further suggestion of cross-signaling, transcription of flhDC is activated by both Epi and AI-3 in a luxS mutant but is not responsive to either one of these signaling compounds in a qseC mutant (Fig. 4H).

Taken together, these results suggest that AI-3 and Epi may signal through the same pathway, and that AI-3 may be a novel compound also inhibited by adrenergic antagonists. A putative model for this signaling cascade is depicted in Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Discussion

Bacteria–host communication has been increasingly recognized as an important aspect of both symbiosis and pathogenesis. Colonization of the light organ of the squid Euprymna scolopes by QS-proficient Vibrio fischeri is necessary for normal development of epithelial cells in this organ (28). In germ-free mice, colonization with high densities of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron modulates expression of numerous genes involved in important intestinal functions including nutrient absorption, mucosal barrier fortification, and angiogenesis (29). The mucosal lining of the human intestine is in contact with a diverse prokaryotic microflora, and it is known that the epithelia from the intestinal tract maintain an inflammatory hyporesponsiveness toward the luminal prokaryotic flora; inhibition of NF-κB in epithelial cells leading to reduced synthesis of inflammatory effector molecules is one reported mechanism (30). In addition, bacterial autoinducers (AHLs) have been demonstrated to have immunomodulatory activities (31–33). Because purified AHLs have been shown to induce IL-8 production (32) and inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and TNFα and IL-12 production (31), Smith et al. (32) proposed that the severe lung damage that accompanies P. aeruginosa infections is caused by an exuberant neutrophil response stimulated by AHL-induced IL-8. Gallio et al. (34) also showed that the function of RHO, the Rhomboid membrane protein involved in regulating the signaling due to the eukaryotic epidermal growth factor, is conserved between bacteria and eukaryotes. Taken together, these studies suggest that QS might be the language by which bacteria and host cells communicate, either through an amicable or detrimental interaction. This idea is especially tantalizing when one considers that eukaryotic cell-to-cell signaling occurs through hormones. Therefore, prokaryotic–eukaryotic communication might also occur through bacterial autoinducers (which are hormone-like compounds) and host hormones.

Our results imply a potential cross-communication between the luxS/AI-2 bacterial QS system and the Epi/NE host signaling system. However, AI-2 is not the autoinducer involved in this signaling. These results may seem contradictory in light of the phenotypes presented by the luxS mutant. However, unlike the LuxI enzymes, which are devoted to the production of AHLs (11), LuxS is actually a metabolic enzyme involved primarily in the detoxification of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM); AI-2 is a by-product of this process (10). A luxS mutation will not only prevent production of AI-2 but also block this detoxification pathway. We have purified another autoinducer compound, AI-3, that is not produced by a luxS mutant, thereby suggesting that the mutation of luxS interrupts another pathway involved in the synthesis of AI-3. If it were a matter of AI-2 signaling for the production of AI-3, transcription of LEE1 should have been induced by exposure to exogenous AI-2, which was not the case (Fig. 4). In eukaryotic cells, detoxification of SAM occurs in two steps rather than three (as in bacteria that harbor luxS), and there is no LuxS analogue. However, it is intriguing that one of these steps is involved in the metabolic pathway that derives Epi from NE (35). Also intriguing is the observation that the gene encoding the monoamine oxidase enzyme, which is involved in the oxidative deamination of catecholamines in eukaryotes, has been hypothesized to be inherited from bacteria (36).

NE has been reported to induce bacterial growth (23, 37), and there are reports in the literature, albeit conflicting, that imply that NE might function as a siderophore (24, 38). Recently, NE has been implicated as inducing expression of enterobactin and iron uptake in E. coli, suggesting that this is the mechanism involved in growth induction (39). However, the role of NE in bacterial pathogenesis seems to be more complex, because several reports suggested that NE was also activating virulence gene expression in E. coli, such as production of fimbriae and Shiga toxin (40, 41), by an unknown mechanism of induction. Here we show that both Epi and NE seem to cross-talk with a bacterial QS system to regulate virulence gene expression in EHEC (Figs. 2 and 3). This signaling is not due to enterobactin and is TonB-independent, suggesting that it is not dependent on the FepA outer membrane receptor for this siderophore (Fig. 4). The signaling depends on an autoinducer, AI-3, which is produced by intestinal flora (Table 1), given that culture supernatant from human intestinal flora contains this signal and activates transcription of the LEE genes. The line dividing QS signaling and iron uptake is becoming increasingly blurred, especially with the description that the siderophore pyoverdine from P. aeruginosa also acts as a signaling molecule (42).

Given the widespread nature of the luxS system in bacteria, an interesting extrapolation is that the luxS QS system might have evolved to mediate microflora–host interaction but ended up being exploited by EHEC to activate its virulence genes. In this manner, the luxS system alerts EHEC as to when it has reached the large intestine, where large numbers of commensal E. coli, Enterococcus, Clostridium, and Bacteroides, all of which contain the luxS QS system (10), are present. Production of AI-3, which depends on the presence of luxS, activates transcription of the type III secretion system and flagella genes, as do Epi and NE. In Fig. 6, we propose a model by which these signals might cross-talk. Our data suggest that both AI-3 and Epi are recognized by the same receptor, which is probably in the outer membrane of the bacteria because of the nonpolar nature of both AI-3 and Epi. These signals might be imported to the periplasmic space where they interact with either one major sensor kinase that directs the transcription of other sensor kinases or with more than one sensor kinase. We favor the latter hypothesis, given our results that a qseC mutant, which does not respond to either AI-3 or Epi (Figs. 2 and 4), only affects the QS regulation of the flagella regulon and not the LEE genes (14). The interaction of AI-3 and Epi with more than one sensor kinase would also give some “timing” to this system, which is a desirable feature, given that it would be inefficient for EHEC to produce both the LEE type III secretion system and flagella at the same time. EHEC could respond to both a bacterial QS signaling system and a mammalian signaling system to “fine tune” transcription of virulence genes at different stages of infection and/or different sites of the gastrointestinal tract. The specific mechanisms involved in this putative interkingdom communication are not yet understood, and further studies in this field will not only give insights into bacterial pathogenesis but also into the microbial flora–host interaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shelley Payne for EHEC tonB mutant; Charles Earhart for entA mutant; Bonnie Bassler for V. harveyi strain BB170; Jennifer Smart and Jennifer Abbott for technical help; and Drs. Leon Eidels, Robert Munford, Kevin McIver, Eric Hansen, Michael Norgard, and Jay Mellies for critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by start-up funds from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (to V.S.) and National Institutes of Health Grants AI41325 and AI21657 (to J.B.K.). A.G.T. was supported by a research supplement from the National Institutes of Health.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: AE, attaching and effacing; AHL, acylhomoserine lactone; AI, autoinducer; EHEC, enterohemorrhagic E. coli; Epi, epinephrine; LEE, locus of enterocyte effacement; NE, norepinephrine; PC, preconditioned; QS, quorum sensing; Qse, QS E. coli regulator.

References

- 1.Kaper, J. B. & O'Brien, A. D. (1998) Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Other Shiga Toxin-Producing E. coli Strains (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC).

- 2.McDaniel, T. K., Jarvis, K. G., Donnenberg, M. S. & Kaper, J. B. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 1664–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott, S. J., Wainwright, L. A., McDaniel, T. K., Jarvis, K. G., Deng, Y. K., Lai, L. C., McNamara, B. P., Donnenberg, M. S. & Kaper, J. B. (1998) Mol. Microbiol. 28, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mellies, J. L., Elliott, S. J., Sperandio, V., Donnenberg, M. S. & Kaper, J. B. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 33, 296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sperandio, V., Mellies, J. L., Delahay, R. M., Frankel, G., Crawford, J. A., Nguyen, W. & Kaper, J. B. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 38, 781–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sperandio, V., Mellies, J. L., Nguyen, W., Shin, S. & Kaper, J. B. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 15196–15201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperandio, V., Torres, A. G., Giron, J. A. & Kaper, J. B. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183, 5187–5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, X., Schauder, S., Potier, N., Van Dorssealaer, A., Pelczer, I., Bassler, B. L. & Hughson, F. M. (2002) Nature 415, 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surette, M. G., Miller, M. B. & Bassler, B. L. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1639–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schauder, S., Shokat, K., Surette, M. G. & Bassler, B. L. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 41, 463–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Kievit, T. R. & Iglewski, B. H. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 4839–4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schauder, S. & Bassler, B. L. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 1468–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperandio, V., Li, C. C. & Kaper, J. B. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 3085–3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sperandio, V., Torres, A. G. & Kaper, J. B. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 43, 809–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin, P. M., Ostroff, S. M., Tauxe, R. V., Greene, K. D., Wells, J. G., Lewis, J. H. & Blake, P. A. (1988) Ann. Intern. Med. 109, 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller, J. H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY).

- 17.Surette, M. G. & Bassler, B. L. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7046–7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarvis, K. G., Giron, J. A., Jerse, A. E., McDaniel, T. K., Donnenberg, M. S. & Kaper, J. B. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 7996–8000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knutton, S., Baldwin, T., Williams, P. H. & McNeish, A. S. (1989) Infect. Immun. 57, 1290–1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrens, M., Sheikh, J. & Nataro, J. P. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 2915–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott, S. J., Hutcheson, S. W., Dubois, M. S., Mellies, J. L., Wainwright, L. A., Batchelor, M., Frankel, G., Knutton, S. & Kaper, J. B. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 33, 1176–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson, B. W. M., McNab, R. & Lax, A. J. (2000) in Cellular Microbiology: Bacteria–Host Interactions in Health and Disease, eds. Henderson, B. W. M., McNab, R. & Lax, A. J. (Wiley, West Sussex, England), pp. 89–162.

- 23.Lyte, M., Frank, C. D. & Green, B. T. (1996) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 139, 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinney, K. S., Austin, C. E., Morton, D. S. & Sonnenfeld, G. (2000) Life Sci. 67, 3075–3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elwan, M. A. & Sakuragawa, N. (1997) NeuroReport 8, 3435–3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenhofer, G., Aneman, A., Friberg, P., Hooper, D., Fandriks, L., Lonroth, H., Hunyady, B. & Mezey, E. (1997) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82, 3864–3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horger, S., Schultheiss, G. & Diener, M. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275, G1367–G1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visick, K. L., Foster, J., Doino, J., McFall-Ngai, M. & Ruby, E. G. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 4578–4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hooper, L. V. & Gordon, J. I. (2001) Science 292, 1115–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neish, A. S., Gewirtz, A. T., Zeng, H., Young, A. N., Hobert, M. E., Karmali, V., Rao, A. S. & Madara, J. L. (2000) Science 289, 1560–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Telford, G., Wheeler, D., Williams, P., Tomkins, P. T., Appleby, P., Sewell, H., Stewart, G. S., Bycroft, B. W. & Pritchard, D. I. (1998) Infect. Immun. 66, 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, R. S., Fedyk, E. R., Springer, T. A., Mukaida, N., Iglewski, B. H. & Phipps, R. P. (2001) J. Immunol. 167, 366–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palfreyman, R. W., Watson, M. L., Eden, C. & Smith, A. W. (1997) Infect. Immun. 65, 617–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gallio, M., Sturgill, G., Rather, P. & Kylsten, P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12208–12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bender, D. A. (1985) Amino Acid Metabolism (Wiley, New York).

- 36.Lander, E. S., Linton, L. M., Birren, B., Nusbaum, C., Zody, M. C., Baldwin, J., Devon, K., Dewar, K., Doyle, M., FitzHugh, W., et al. (2001) Nature 409, 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freestone, P. P., Haigh, R. D., Williams, P. H. & Lyte, M. (1999) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 172, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freestone, P. P., Lyte, M., Neal, C. P., Maggs, A. F., Haigh, R. D. & Williams, P. H. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 6091–6098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton, C. L., Chhabra, S. R., Swift, S., Baldwin, T. J., Withers, H., Hill, S. J. & Williams, P. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 5913–5923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyte, M., Arulanandam, B. P. & Frank, C. D. (1996) J. Lab. Clin. Med. 128, 392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyte, M., Erickson, A. K., Arulanandam, B. P., Frank, C. D., Crawford, M. A. & Francis, D. H. (1997) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 232, 682–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamont, I. L., Beare, P. A., Ochsner, U., Vasil, A. I. & Vasil, M. L. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 7072–7077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.