Abstract

Puroindoline a, a wheat endosperm-specific protein containing a tryptophan-rich domain, was reported to have antimicrobial activities. We found that a 13-residue fragment of puroindoline a (FPVTWRWWKWWKG-NH2) (puroA) exhibits activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. This suggests that puroA may be a bactericidal domain of puroindoline a. PuroA interacted strongly with negatively charged phospholipid vesicles and induced efficient dye release from these vesicles, suggesting that the microbicidal effect of puroA may be due to interactions with bacterial membranes. A variety of biophysical and biochemical methods, including fluorescence spectroscopy and microcalorimetry, were used to examine the mode of action of puroA. These studies showed that puroA is located at the membrane interface, probably due to its high content of Trp residues that have a high propensity to partition into the membrane interface. The penetration of these Trp residues in negatively charged phospholipid vesicles resembling bacterial membranes was more extensive than the penetration in neutral vesicles mimicking eukaryotic membranes. Peptide binding had a significant influence on the phase behavior of the former vesicles. The three-dimensional structure of micelle-bound puroA determined by two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy indicated that all the positively charged residues are oriented close to the face of Trp indole rings, forming energetically favorable cation-π interactions. This characteristic, along with its well-defined amphipathic structure upon binding to membrane mimetic systems, allows puroA to insert more deeply into bacterial membranes and disrupt the regular membrane bilayer structure.

Antimicrobial peptides play an important role in the host defense systems of all living organisms, including plants, insects, amphibians, and mammals, serving as the first line of defense against invading pathogens (4, 38, 66). Because of the dramatic increase in the frequency of appearance of multiple-drug-resistant bacteria, antimicrobial peptides are thought to be potential alternatives to conventional antibiotics due to their rapid killing action, highly selective toxicity, and low potential for development of resistance (19). Many antimicrobial peptides have been found to exert activity on bacterial membranes by forming ion channels or pores, by dissolving the membranes like a detergent, or by inducing membrane defects (13, 40, 46). Spontaneous uptake followed by inhibition of DNA or protein synthesis, leading to cell death, has also been suggested as an alternative mechanism for a number of antimicrobial peptides (5, 41, 62). Furthermore, it has been found that many factors, such as peptide length, amino acid sequence, charge, hydrophobicity, and amphipathicity, can dramatically affect the potency and action spectrum of antimicrobial peptides. Understanding these factors should help in designing novel peptides with increased potency and directed activity.

Plant seeds contain high concentrations of many antimicrobial proteins. Puroindolines (13 kDa) are the most abundant proteins isolated from wheat endosperm by phase partitioning with the nonionic detergent Triton X-114 (2). Two isoforms, designated puroindoline a (major component) and puroindoline b (minor component), have been purified. The puroindolines are unique among plant proteins because they contain a tryptophan-rich hydrophobic domain. It appears that the puroindolines have two functions in vivo. First, puroindoline proteins form the molecular basis of wheat grain hardness that determines the end use quality of wheat. With both puroindolines in their functional state, the grain is soft; when either one of the puroindolines is absent or altered by mutation, the grain is hard (37). The second function is that wheat puroindolines greatly enhance disease resistance in transgenic rice (27), indicating that they could also play an important role in defending wheat seeds against various pathogens. Indeed, puroindolines have been reported to possess broad antimicrobial activity in vitro and have a synergistic inhibitory effect on fungal growth when they are mixed with other wheat antimicrobial proteins (32). Therefore, puroindolines can be considered potential new tools for the control of a wide range of plant pathogens. The antimicrobial activity of intact puroindoline a is thought to involve interactions with cell membranes due to its ability to bind tightly to polar lipids (18).

In this paper, we report that a 13-residue fragment of puroindoline a, including its Trp-rich domain (puroA), exhibits activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, indicating that puroA might be a bactericidal domain of puroindoline a. Like many other antimicrobial peptides, puroA could potentially be developed into a new antibiotic. Furthermore, the antimicrobial activity of puroindoline a may be improved by mutating the corresponding gene sequences encoding puroA. For comparison, we also determined the antimicrobial activity of the related puroB peptide. In an attempt to unravel the mechanism of action of puroA, we studied its interaction with model membranes having various compositions. In addition, we determined the structure of puroA bound to membrane-mimicking sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) micelles by conventional two-dimensional (2D) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods, which helped demonstrate the structural characteristics that are important for the interaction of puroA with membranes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

puroA (FPVTWRWWKWWKG-NH2) and puroB (FPVTWPTKWWKG-NH2) were synthesized by the Peptide Synthesis Facility at the University of Western Ontario and were purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (purity, >95%). Perdeuterated SDS and D2O (99.9%) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. Sodium 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate was purchased from MSD isotopes. Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC), dipalmitoylphosphatidylglycerol (DPPG), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol, (POPG), and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, Ala.) and were used without further purification. All other chemicals and solvents were reagent grade.

Antimicrobial activity.

The bacterial strains Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 were grown in 2% Bacto Peptone Water (Difco 1807-17-4) until the exponential phase. The cell concentrations were calculated on the basis of a predetermined relationship, 3.8 × 108 CFU/ml = 1 U of A600. Each cell suspension was diluted in 2% Bacto Peptone Water to a concentration of 2 × 106 CFU/ml, and the inoculum was then added to the wells of 96-well polystyrene plates. The peptide samples were added to the wells and incubated overnight at 37°C. The concentration range used for the peptides was 300 to 1.0 μg/ml. Changes in the turbidity of the peptone-based growth medium were detected at 540 nm. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of a peptide that inhibited growth. All peptides were tested in triplicate.

Hemolytic activity.

The hemolytic activities of the peptides were determined by using human erythrocytes. Briefly, erythrocytes were isolated from heparinized human blood by centrifugation after it was washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (5 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl). Aliquots containing ∼107 cells/ml were incubated with different concentrations of peptides for 30 min at 37°C with gentle mixing. The tubes were then centrifuged, and the absorbance of each supernatant was measured at 540 nm. Zero hemolysis (blank) and 100% hemolysis were determined in phosphate buffer and 1% Triton X-100, respectively.

Preparation of multilamellar and unilamellar vesicles.

Multilamellar vesicles consisting of DPPG and DPPC used for differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments were prepared as follows. Appropriate amounts of a phospholipid stock solution were dried under a stream of nitrogen and stored under a vacuum overnight to completely remove trace amounts of organic solvent. The dried lipid films were then dispersed in excess buffer (20 mM phosphate buffer, 130 mM NaCl; pH 7.4), and an appropriate amount of a peptide stock solution was added to give the desired lipid-to-peptide molar ratio. Samples were then hydrated at temperatures 10°C above the liquid crystalline phase of the lipids for 2 h with intermittent, vigorous vortex mixing. The concentrations of phospholipids were calculated on the basis of the weight of dried lipid. The concentration of the peptide stock solution was determined by using UV absorbance and a theoretically calculated molar extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 27,825 M−1 cm−1.

Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) for isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were prepared by the extrusion method by using an Avanti small-volume extrusion apparatus. After a final trace amount of organic solvent was evaporated, the dried lipid film was suspended by vortexing it in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 130 mM NaCl (pH 7.4). The multilamellar vesicle suspension was freeze-thawed five times and then successively extruded through two stacked polycarbonate filters (pore size, 0.1 μm) 13 times. To reduce the effect of light scattering of LUVs, small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were used for fluorescence experiments. SUVs were prepared by sonication. LUVs were sonicated in ice water by using a titanium tip ultrasonicator until the solution became transparent.

Calcein-entrapped LUVs for dye leakage experiments were also prepared by the extrusion method as described above. The dried lipid films were hydrated with 2 ml of Tris-HCl buffer containing 70 mM calcein and then extruded to make LUVs. Calcein-entrapped vesicles were separated from free calcein by gel filtration by using a Sephadex G-50 column equilibrated with the same buffer. The lipid concentration was determined by phosphorus analysis (1).

Leakage experiments.

Tris-HCl buffer in a cuvette was added to vesicles containing 70 mM calcein to obtain a vesicle solution with a final lipid concentration of 50 μM. The fluorescence intensity of calcein released from vesicles was monitored at 520 nm (after excitation at 490 nm) with a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer and was measured 1.0 min after addition of the peptide. To measure the fluorescence intensity for 100% dye leakage, 20 μl of Triton X-100 (20% in Tris buffer) was added to completely dissolve the vesicles. The percentage of dye leakage caused by the peptide (% leakage) was calculated by using the following equation: % leakage = 100 × (F − F0)/(Ft − F0), where the F0 and Ft are the initial fluorescence intensities observed without the peptide and after Trition X-100 treatment, respectively, and F is the fluorescence intensity observed with the peptide.

DSC.

DSC was performed with a high-sensitivity VP-DSC instrument (Microcal, Northampton, Mass.). For all samples a scan rate of 60°C/h was used. Sample runs were repeated at least twice to ensure reproducibility. The total lipid concentration used for DSC was 1.0 mg/ml. Data acquisition and analysis were done by using Microcal's Origin software (version 5.0). The enthalpy change of the phase transition was obtained from the area under the peak and the mass of the phospholipid in each sample.

ITC.

ITC was performed with a Microcal high-sensitivity VP-ITC instrument. Solutions were degassed under a vacuum prior to use. LUVs consisting of POPG or POPC were injected into the chamber containing a peptide solution. The heats of dilution were determined in control experiments by injecting corresponding lipid vesicles into buffer and were subtracted from the heats produced in the peptide-lipid binding experiments. Data acquisition and analysis were performed by using Microcal′s Origin software (version 5.0).

Fluorescence spectroscopy.

Fluorescence spectra were obtained with a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer by using an excitation wavelength of 295 nm, and emission was scanned from 300 to 450 nm at a scan rate of 10 nm/s. Each spectrum was the average of 10 scans. Spectra were baseline corrected by subtracting blank spectra of the corresponding solutions without peptide. All samples contained 2 μM peptide in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4)-130 mM NaCl, and the concentration of phospholipids was 2 mM. For fluorescence quenching experiments, a 4 M acrylamide stock solution was added to obtain final concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 M. The effect of acrylamide on peptide fluorescence was analyzed by using the quenching constant (Ksv) as determined from the Stern-Volmer equation (11): F0/F = 1 + Ksv [Q], where F0 and F are the fluorescence intensities in the absence and in the presence of the quencher (Q), respectively.

CD spectroscopy.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were obtained with a Jasco J-715 spectrophotometer. Each spectrum (190 to 260 nm) was the average of four scans obtained by using a quartz cell with a 1-mm path length at room temperature. The scanning speed was 50 nm/min at a step size of 0.1 nm with a 2-s response time and a 1.0-nm bandwidth. All samples contained 40 μM peptide in 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4), and the concentration of the detergents was 20 mM. Spectra were baseline corrected by subtracting a blank spectrum containing all components except the peptide. After noise correction, ellipticities were converted to mean residue molar ellipticities expressed in degree · square centimeter per decimole.

NMR spectroscopy.

The sample of puroA was prepared by adding a solution of perdeuterated SDS in H2O-D2O (9:1) to lyophilized peptide, and the pH was adjusted to 4.3 by using dilute HCl or NaOH. SDS rather than dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) was used because its negatively charged headgroup more closely approximates a bacterial membrane. The concentration of puroA was determined by using UV absorbance and a theoretically calculated molar extinction coefficient at 280 nm of 27,825 M−1 cm−1. The final samples contained 2.65 mM puroA and 200 mM SDS-d25. Sodium 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate was added as an internal chemical shift reference compound.

NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker Avance 500-MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a Cryo-probe (Bruker Analytische Messtechnik GmbH). One-dimensional 1H, 2D total correlation spectroscopy (43) (mixing time, 120 ms), and 2D nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) (6) (mixing time, 100 ms) spectra were recorded at 25°C. The 2D data were acquired with 2,048 × 512 data points in the F2 and F1 dimensions by using spectral widths of 6,500 Hz. Water suppression was achieved by using the excitation sculpting technique (22). In addition, a z gradient pulse was applied during the mixing time in the NOESY experiment. The data were zero filled and processed with a shifted sine bell function by using the NMRPIPE software package (9). All the data processing was performed with a PC workstation by using the Redhat Linux operating system.

Structure calculations.

Distance restraints were obtained from the NOESY spectra by using NMRVIEW 4.1.3 (24). On the basis of nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) peak intensities, distance restraints were classified as strong, medium, and weak, corresponding to upper boundaries of 2.8, 3.3, and 5.0 Å, respectively. Structures were calculated by using CNS 1.0 (7) first and then were refined by using the program ARIA (39). No hydrogen bond restraints were applied. Because the peptide was bound to the surface of micelles, the resonances were relatively broad. Therefore, the coupling constants could not be resolved, and the dihedral angles were constrained only to the broad region between −35° and −180°. Of the 100 resulting structures, the 20 lowest-energy structures were kept. Structures were analyzed with the MOLMOL program (26).

RESULTS

Antibacterial and hemolytic activities.

E. coli ATCC 25922 and S. aureus ATCC 25923 were used to determine the antimicrobial activities of puroA and puroB. The MICs of puroA for E. coli and S. aureus were 7 and 16 μM, respectively, indicating that puroA exhibits activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. The MICs of puroB for E. coli and S. aureus were over 200 μM. The hemolytic activities of the puroA and puroB peptides were extremely low (concentration necessary for 50% hemolysis, >1,000 μg/ml). Because of the poor antimicrobial activity of puroB, this peptide was not studied further.

Peptide-induced dye leakage.

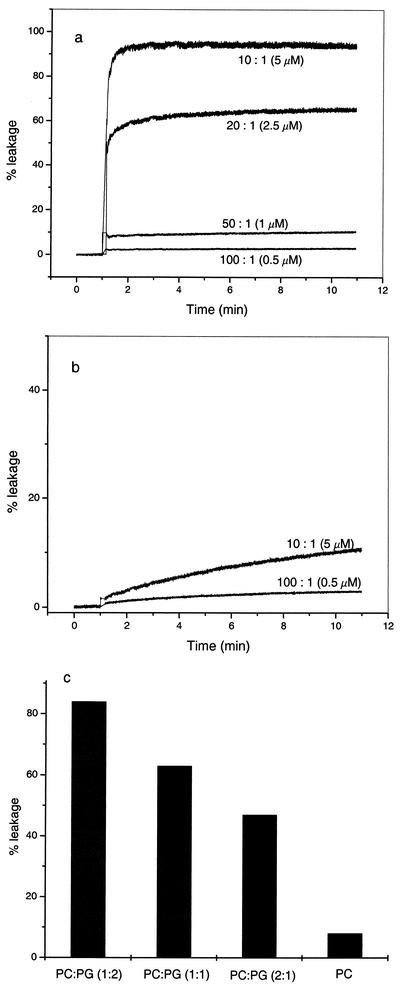

The ability of puroA to disrupt membranes was investigated by studying dye release from phospholipid vesicles. Upon addition of puroA to the vesicles, the entrapped calcein was released into the buffer due to lysis or leakage induced by the peptide. We used neutral POPC LUVs to mimic eukaryotic membranes and negatively charged mixed POPC-POPG LUVs to mimic bacterial membranes. Figures 1a and b show the levels of calcein leakage from 50 μM POPC-POPG (1:1) LUVs and 50 μM POPC LUVs after different incubation times when different lipid-to-peptide molar ratios were used. To look at the importance of acidic headgroups for triggering susceptibility to calcein release, we also studied the leakage efficiency induced by 2.5 μM puroA (lipid-to-peptide molar ratio, 20:1) using vesicles with different negatively charged lipid contents (Fig. 1c). PuroA induced more efficient dye release from LUVs containing larger amounts of POPG.

FIG. 1.

Calcein release from 50 μM POPG-POPC (1:1) LUVs (a) and 50 μM POPC LUVs (b). The responses to different puroA peptide concentrations are shown. (c) Extent of leakage from 50 μM LUVs induced by 2.5 μM puroA when vesicles with different POPC (PC)/POPG (PG) molar ratios were used. For details see Materials and Methods.

DSC.

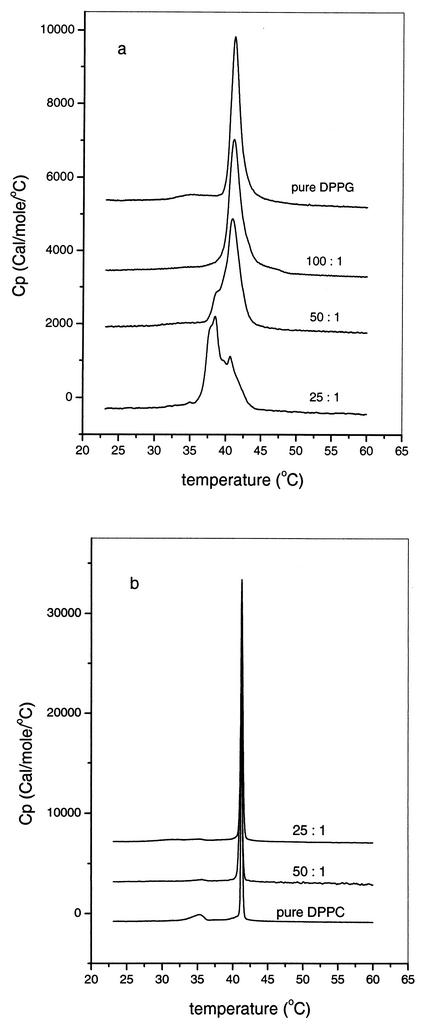

The thermotropic phase behavior of model membranes was studied by DSC, which is very sensitive to effects caused by minor components partitioning into the lipid matrix (36). DSC thermograms of DPPG vesicles in the absence and presence of puroA at different lipid-to-peptide molar ratios are shown in Fig. 2a. The pretransition from the lamellar gel phase to the lamellar ripple phase of DPPG around 34.8°C and the main transition from the gel phase to the liquid-crystalline Lα phase at 40.5°C are consistent with previously published data (67). Addition of puroA significantly influenced the phase behavior of DPPG vesicles, as shown in Fig. 2a. At a lipid-to-peptide molar ratio of 100:1, the pretransition disappeared, while little effect on the main phase was observed. At a lipid-to-peptide molar ratio of 50:1, two components appeared for the main phase transition, which suggests that there is separation of the membrane into domains rich in peptide (the shoulder at a lower temperature) and a region where the lipid is unperturbed (29). The area of the peptide-rich domain increased as the amount of peptide increased. At a lipid-to-peptide molar ratio of 25:1, the main transition of the DPPG vesicles for the most part reflected domains rich in peptide; however, the enthalpy change calculated for the whole transition range (8.53 kcal/mol) is comparable to the value for pure DPPG (8.87 kcal/mol).

FIG. 2.

Heating scans for DPPG (a) and DPPC (b) multilamellar vesicles with and without puroA in 20 mM phosphate buffer containing 130 mM NaCl (pH 7.4) at a scan rate of 60°C/h. puroA was added to preparations containing 1 mg of lipid vesicles per ml to give lipid-to-peptide molar ratios of 100:1, 50:1, and 25:1, as indicated.

DSC heating thermograms illustrating the effect of puroA on the thermotropic phase behavior of DPPC vesicles are shown in Fig. 2b. Aqueous dispersions of DPPC also exhibited a pretransition around 35.2°C and a main phase transition at 41.4°C. Addition of puroA had very little effect on the phase behavior of DPPC even at high concentrations of the peptide.

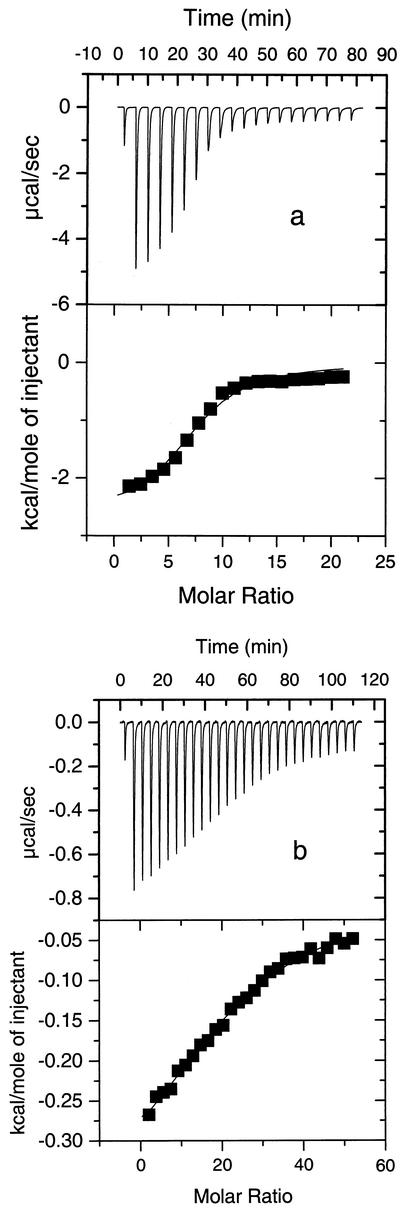

ITC.

Figures 3a and b show the titration traces determined when 10 mM POPG LUVs and 10 mM POPC LUVs, respectively, were injected into a solution containing 40 μM puroA. Each injection produced an exothermic heat of reaction which decreased with consecutive injections. The ITC data were used to compare the affinities of puroA for vesicles containing different headgroups. The binding constants determined for puroA bound to POPG and POPC LUVs were 1.6 × 105 and 4.4 × 104 M−1, respectively. These data clearly indicate that there was tighter binding of puroA to the negatively charged POPG vesicles, which is consistent with the outcome of the DSC measurements.

FIG. 3.

Titration calorimetry of a 40 μM puroA solution with POPG LUVs (a) and POPC LUVs (b) in 20 mM Tris buffer containing 130 mM NaCl (pH 7.4).

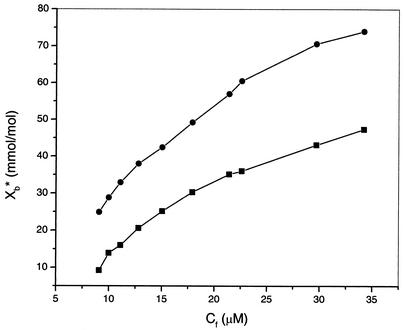

Detailed analysis of the ITC data provided a binding isotherm. For calculation of the binding isotherm, only the lipid in the outer layer of the lipid vesicles (60% of the total lipid) was considered (58). Figure 4 shows the binding isotherms for puroA binding to POPG or POPC LUVs, which indicate that there was stronger binding of puroA to POPG vesicles than to POPC vesicles and that there was a simple binding process in each case (53).

FIG. 4.

Isotherms for binding of puroA to POPG LUVs (•) and POPC LUVs (▪) derived from ITC data. Xb∗ is the molar ratio of bound peptide for 60% of the lipid; Cf is the equilibrium concentration of the free peptide in solution.

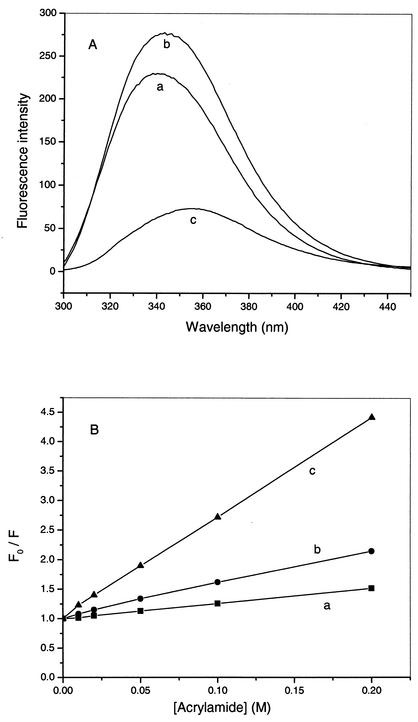

Tryptophan fluorescence.

The fluorescence spectra of puroAin buffer and puroA bound to different lipid LUVs are shown in Fig. 5A. The emission maximum of puroA in aqueous solution alone was around 355 nm, which was equal to that of a tryptophan control. Binding of puroA to POPG and POPC SUVs caused 15- and 10-nm blue shifts in the emission maximum, respectively, along with concomitant increases in intensity, indicating that the Trp side chain had partitioned into a more hydrophobic environment (28).

FIG. 5.

Fluorescence emission spectra (A) and Stern-Volmer plots (B) for 2 μM puroA bound to POPG SUVs (lines a) and to POPC SUVs (lines b) and in buffer (lines c). The concentration of POPG and POPC was 2 mM.

To determine the relative extent of penetration of the Trp residues of puroA into model membranes, a fluorescence quenching experiment was performed with the neutral fluorescence quencher acrylamide by determining the Stern-Volmer constant (Ksv). The more extensively Trp residues are shielded from the quenching agent, the smaller the Ksv (11). The Ksv for puroA was 17 M−1 in aqueous solution, and the values were 3.25 and 1.2 M−1 in POPC and POPG SUVs, respectively (Fig. 5B). These values confirm that when the peptide is free in solution, the quencher can approach the Trp side chains more readily than when the peptide is bound to model membranes. In addition, quenching of Trp fluorescence is less efficient with POPG than with POPC, suggesting that the Trp residues of puroA are buried more extensively in POPG vesicles than in POPC vesicles.

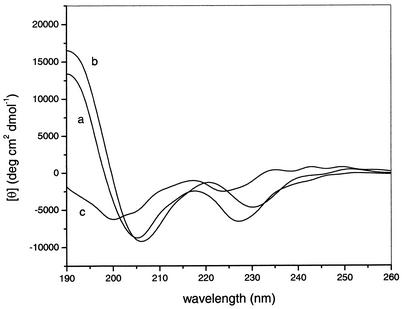

CD spectroscopy.

The CD spectra of free and micelle-bound puroA are shown in Fig. 6. In aqueous solution alone, the spectrum had two negative bands around 200 and 225 nm. The minimum at 200 nm is typical for the backbone of peptides in a random coil conformation (42). The minimum at 225 nm was likely caused by side chain absorption of the tryptophan residues (61). Upon binding to SDS or DPC micelles, minima at 205 and 218 nm and a maximum at 195 nm were enhanced, indicating that there may be induction of a helical structure upon binding (42). However, because of the presence of numerous Trp residues in the peptide, these CD data are difficult to interpret directly in terms of secondary structure alone (61).

FIG. 6.

CD spectra for 40 μM puroA bound to 20 mM SDS (line a) or 20 mM DPC (line b) and in buffer (line c). θ, mean residue molar ellipticity.

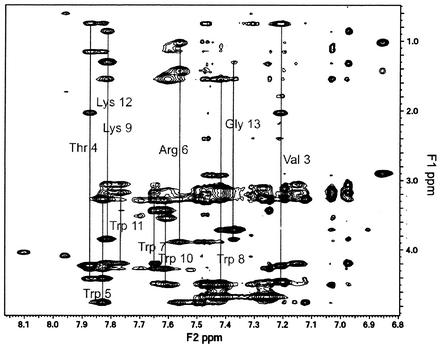

NMR spectroscopy.

The structure of puroA was determined with the peptide bound to SDS micelles. Use of micelles (rather than phospholipid vesicles) was necessary to allow acquisition of high-resolution solution state NMR data. Peptide structures cannot be determined in vesicles by this method due to the increase in the rotational correlation time of the much larger vesicles (31).

The 2D NOESY spectra of puroA in solution in the absence of micelles gave only intraresidual and sequential NOEs, indicating that there was no defined and stable secondary structure under these conditions (data not shown).

The 2D NOESY spectra of puroA in the presence of SDS micelles displayed a significant number of interresidual NOEs, indicating that there was a preferred conformation arising from the interaction with the SDS micelles. The chemical shift assignments were obtained by using the standard 2D NMR methodology of Wüthrich (63). Figure 7 shows the fingerprint region of the NOESY spectrum of puroA bound to SDS micelles. A nearly complete assignment was obtained. Due to the spectral overlap and the broad resonances, it was not possible to unambiguously resolve all the proton resonances for the two Lys residues. Additionally, inspection of the 2D total correlation spectroscopy spectrum revealed two spin systems for Val3 and Thr4, which could be attributed to their proximity to Pro2 with cis and trans conformations for this amino acid. However, the relative NOE intensities of the second set of resonances for Val3 and Thr4 were too small to use for structure calculation for the minor conformer. The structural analysis of puroA presented below represented the major conformation. The Pro residue of the major conformer is in the trans conformation, as indicated by the presence of an NOE between the δ-protons of Pro2 and the α-proton of Phe1. Additionally, there were a number of unusual chemical shifts for Arg6, Lys9, and Lys12. The side chain resonances of these three residues were shifted upfield. The shifts in resonance frequencies for these protons can be explained by an orientation near the planar face of a Trp aromatic ring due to its diamagnetic anisotropic shielding (63).

FIG. 7.

Fingerprint region of the NOESY spectrum for 2.65 mM puroA in 90% H2O-10% D2O containing 200 mM SDS (pH 4.3) at 298 K with a mixing time of 100 ms.

Many of the sequential HNi-HNi+1 cross-peaks were stronger than the corresponding sequential Hαi-HNi+1 peaks. This backbone connectivity is typical for an α-helical structure. Additionally, a number of nonsequential NOE connectivities characteristic of an α-helix, i.e., dαβ(i, i+3), dNN(i, i+2), dαN(i, i+3), and dαN(i, i+4) correlations, were also observed for residues 7 to 12. The chemical shift values determined for the α-protons also supported the tendency toward a helical character for residues 7 to 12 of puroA.

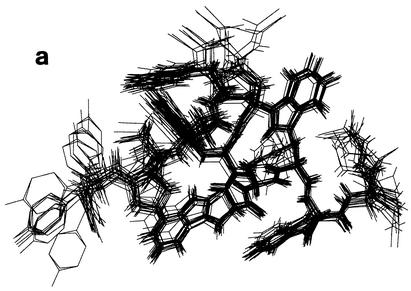

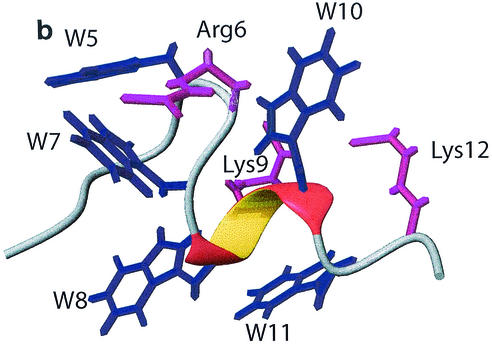

The structure of puroA bound to SDS micelles was calculated by using 246 NOE-based distance restraints; 217 of the NOEs were unambiguous, and 29 were ambiguous. The root mean square deviations from ideal geometry were as follows: covalent bonds, 0.0036 ± 0.0001 Å; covalent angles, 0.48 ± 0.017°; improper angles, 0.39 ± 0.023°; and dihedral angles, 0.75 ± 0.037°. The energies were as follows: overall, 101.83 ± 3.26 kcal/mol; bonds, 2.55 ± 0.15 kcal/mol; improper, 1.47 ± 0.27 kcal/mol; VDW, 45.93 ± 1.99 kcal/mol; and NOE, 24.66 ± 1.46 kcal/mol. On average, about 17 distance restraints per residue were applied, which resulted in a very well-defined structure. The 20 final structures with the lowest energy had root mean square deviations of 1.287 Å for the heavy atoms and 0.522 Å for the backbone atoms when all residues were fitted (Fig. 8a). Overall, puroA bound to SDS micelles had a helical segment from Trp8 to Trp10 preceded by a turn from Thr4 to Trp7 (Fig. 8b). Indeed, the Arg6 side chain was oriented between the two aromatic indole rings of Trp5 and Trp7, and the side chains of both Lys9 and Lys12 were in the vicinity of Trp10, which is consistent with the unusual chemical shift data observed for these three positively charged residues. The driving force for this arrangement can be attributed to the formation of energetically favorable cation-π interactions (10).

FIG. 8.

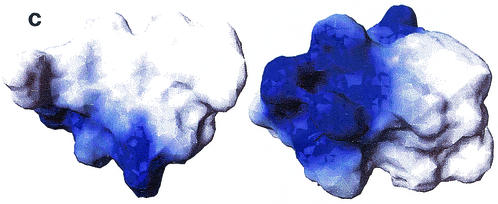

(a) Stick diagrams of the 20 final structures of puroA bound to SDS. (b) Ribbon diagram of the averaged structure of puroA. The side chains of all Trp residues (blue) and positively charged residues (pink) are visible. (c) Charge distribution on the surface of puroA. Positive and neutral potentials are blue and white, respectively.

Figure 8c shows the electrostatic potential map of the lowest energy structure of puroA bound to SDS micelles. The charge distribution exhibits an amphipathic structure, with the positively charged Lys and Arg residues forming a small hydrophilic face and the hydrophobic residues forming the large hydrophobic face.

DISCUSSION

Trp-rich cationic antimicrobial peptides have recently attracted increased interest from researchers because Trp residues are known to play important roles in the antimicrobial and hemolytic activities of antimicrobial peptides (14, 23, 48, 54, 56, 57). A well-studied representative of the group of Trp-rich antimicrobial peptides is indolicidin. Indolicidin (ILPWKWPWWPWRR-NH2), a 13-residue linear antimicrobial peptide isolated from the cytoplasmic granules of bovine neutrophils (52), has been shown to be able to act by disrupting membranes. The same mechanism of action has been proposed for tritrpticin, a short peptide found in porcine white blood cells, which contains three adjacent Trp residues in its sequence (30). Interestingly, in contrast, CP10A, an indolicidin analog in which the three Pro residues are replaced by Ala, has been proposed to affect the intracellular synthesis of proteins (15). The potential to design closely related peptides with distinct or dual bacterial killing mechanisms makes Trp-rich antimicrobial peptides ideal molecules for studies of antimicrobial peptides as novel therapeutic agents.

We report here that the 13-amino-acid peptide puroA (FPVTWRWWKWWKG-NH2) derived from the plant antimicrobial protein puroindoline a exhibits activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. These data suggest that puroA is a functional bactericidal domain of puroindoline a. Showing some sequence similarity with indolicidin and tritrpticin, puroA is characterized by a high tryptophan residue content (39%). This, along with the fact that it has a broad antimicrobial activity, should make puroA another interesting Trp-rich antimicrobial peptide for study.

Like many other antimicrobial peptides, such as magainin (59) and tritrpticin (64), which are believed to exert their main antimicrobial effects on the cytoplasmic membranes of microorganisms, puroA strongly binds to vesicles containing phospholipids with negatively charged headgroups and in doing so induces efficient dye leakage from the vesicles. These results indicate that puroA also acts through binding to and destabilization of the microbial membrane rather than through a specific protein receptor.

The relative capacity of puroA to lyse membranes depends on the composition of the vesicles. The calcein leakage from vesicles containing negatively charged lipid headgroups is much greater than the leakage from vesicles containing neutral zwitterionic lipids. This is consistent with the DSC results, which showed that puroA markedly influences the phase behavior of negatively charged DPPG vesicles while it leaves the neutral DPPC vesicles almost intact. These results indicate that electrostatic interactions play an important role in the interaction of puroA with membranes. As indicated by the ITC results, the stronger binding of puroA to negatively charged POPG LUVs than to neutral POPC LUVs further supports this point. The preference for inducing perturbations in negatively charged lipids explains in part the selective activity of antimicrobial peptides with negatively charged bacterial membranes rather than mammalian cells, in agreement with the fact that puroA has low hemolytic activity.

Membrane leakiness can be induced either by perturbation of lipid packing or by formation of peptide pores (12, 13). Peptide pores usually require peptides oligomerized on the membrane surface, followed by transmembrane orientation of the peptides that are involved. The slopes of the binding isotherms of channel or pore peptides, such as pardaxin (44) and δ-endotoxin (17), have been found to increase sharply as the equilibrium concentration of the free peptide in solution increases. However, we did not observe such a phenomenon for puroA (Fig. 4). In addition, although the phase transition of DPPG was altered by a high concentration of puroA, the enthalpy of the main transition is comparable to the enthalpy for pure DPPG, thus suggesting that puroA does not penetrate deeply into the hydrophobic region of DPPG vesicles. Based on these data, puroA most likely resides at the solvent-lipid interface because peptides or proteins interacting with the hydrophobic regions of membranes often exhibit large reductions in transition enthalpy (33). This, along with the observation that puroA decreased the temperature and cooperativity of the main phase transition of DPPG, is characteristic of an interfacial location in the phospholipid bilayer (35). Furthermore, partial quenching of Trp fluorescence was still detected for membrane-bound puroA, indicating that the peptide is not fully sequestered in the hydrophobic interior of membranes. Thus, we concluded that puroA resides in the interface region of membranes and does not penetrate deeply into the membrane to form stable channels or pores, which suggests that puroA may exert its antimicrobial effect by perturbing the bilayer structure of membranes through a process such as inducing positive curvature strain in membranes (34).

The peptide's preferential location at the membrane interface appears to result in part from its high content of Trp residues. It has been found that the amino acid Trp prefers to partition into the interfacial region of membranes, specifically near the lipid carbonyl region (45, 60, 65). The importance of tryptophan as a membrane interface binding moiety has been observed for various antimicrobial peptides, such as gramicidin A (25), tritrpticin (49), indolicidin (47), and some membrane-proximal or transmembrane segments of membrane proteins (50, 51). We suggest that the exact location of puroA in the lipid bilayer may vary with the charge and structure of the lipid polar headgroup. As indicated by our fluorescence experiments, Trp residues in puroA are more effectively shielded from the neutral acrylamide quencher in POPG vesicles than in POPC vesicles. Therefore, puroA can markedly influence the phase behavior of DPPG, but at the same concentration it has no effect on the phase behavior of DPPC.

puroA is unstructured in aqueous solution, as expected for a linear peptide consisting of 13 residues. However, puroA forms a well-defined amphipathic structure with the positively charged side chains localized to the polar face upon binding to SDS micelles (Fig. 8c). The structure bound to a biological bilayer is expected to be very similar if not the same. Formation of an amphipathic structure has been postulated to be a requirement for interactions of some cationic antimicrobial peptides with bacterial membranes (3, 20, 21). The various structures determined to date for a variety of Trp-rich antimicrobial peptides lead us to believe that different peptides may have different antimicrobial spectra, different potencies, and even different mechanisms of action. It is interesting that puroA has two consecutive WWK(R) sequences which have also been found in other antimicrobial proteins found in plants. These sequences have been proposed to play an important role in the function of the molecule (8, 55). Structurally, all the positively charged residues of puroA are oriented close to the planar face of Trp indole rings and are shielded by Trp indole rings by the formation of energetically favorable cation-π interactions. Statistical analysis of high-resolution protein structures indicated that such interactions occur frequently, particularly when they involve Trp and Arg residues (16). Such interactions would facilitate deeper embedding of puroA specifically into bacterial membranes.

Finally, we found that the corresponding peptide puroB (FPVTWPTKWWKG-NH2), derived from puroindoline b, had a much lower antimicrobial activity than puroA. The lower potency of puroB is likely due to the lower number of positively charged and Trp amino acids in this peptide. We are currently attempting to improve the antimicrobial activity of puroB by rational design.

In conclusion, we found that the 13-residue synthetic peptide FPVTWRWWKWWKG-NH2 encompassing the Trp-rich domain of puroindoline a has antimicrobial activity, suggesting that it is a functional domain of puroindoline a. This peptide binds strongly to negatively charged vesicles and induces dye release from these vesicles, suggesting that it acts, at least in part, on bacterial membranes. It forms a partially helical amphipathic structure upon binding to membrane-mimicking systems. The peptide resides in the membrane interface, which is also the preferred location for tryptophan indole rings. The amphipathic structure and cation-π interactions between positively charged Lys and Arg residues and the Trp aromatic indole ring may allow puroA to penetrate more deeply into bacterial membranes and disrupt the membrane structure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) to H.J.V. H.J.V. and W.G.J. received a senior scientist award and a postdoctoral fellowship award, respectively, from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR). The fluorescence and microcalorimetry equipment was purchased through a grant from the Alberta Network of Proteomics Innovation. The NMR spectrometer used was recently upgraded with funds from the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Alberta Science and Research Authority, and the AHFMR. NMR maintenance is supported by the CIHR.

We are indebted to Howard N. Hunter and David J. Schibli for many helpful suggestions and to Gilles Lajoie and his staff at the University of Western Ontario for peptide synthesis. We also thank Ø. Rekdal and his coworkers at the University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway, for testing the antimicrobial and hemolytic activities of the two peptides.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames, B. N. 1966. Assay of inorganic phosphate, total phosphate and phosphatases. Methods Enzymol. 8:115-118.

- 2.Blocher, J. E., C. Chevalier, and D. Marion. 1993. Complete amino acid sequence of puroindoline, a new basic and cystine-rich protein with a unique tryptophan-rich domain, isolated from wheat endosperm by Triton X-114 phase partitioning. FEBS Lett. 3:336-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blondelle, S. E., and R. A. Houghten. 1992. Design of model amphipathic peptides having potent antimicrobial activities. Biochemistry 31:12688-12694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boman, H. G. 1995. Peptide antibiotics and their role in innate immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 13:61-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boman, H. G., B. Agerberth, and A. Boman. 1993. Mechanisms of action on Escherichia coli of cecropin P1 and PR-39, two antibacterial peptides from pig intestine. Infect. Immun. 61:2978-2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braunschweiller, L., and R. R. Ernst. 1983. Coherence transfer by isotropic mixing: application to proton correlation spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 53:521-528. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunger, A. T., P. D. Adams, G. M. Clore, W. L. Delano, P. Gros, R. W. Grosse Kunstleve, J. S. Jiang, J. Kuszwski, M. Nilges, N. S. Pannu, R. J. Read, L. M. Rice, T. Simonson, and G. L. Warren. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 54:905-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cammue, B. P., K. Thevissen, M. Hendriks, K. Eggermont, I. J. Goderis, P. Proost, J. Van Damme, R. W. Osborn, F. Guerbette, and J. C. Kader. 1995. A potent antimicrobial protein from onion seeds showing sequence homology to plant lipid transfer proteins. Plant Physiol. 109:445-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delaglio, F., S. Grzesiek, G. W. Vuister, G. Zhu, J. Pfeifer, and A. Bax. 1995. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6:277-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dougherty, D. A. 1996. Cation-pi interactions in chemistry and biology: a new view of benzene, Phe, Tyr, and Trp. Science 271:163-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eftink, M. R., and C. A. Ghiron. 1976. Fluorescence quenching of indole and model micelles system. J. Phys. Chem. 80:486-493. [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Jastimi, R., K. Edwards, and M. Lafleur. 1999. Characterization of permeability and morphological perturbations induced by nisin on phosphatidylcholine membranes. Biophys. J. 77:842-852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epand, R. M., and H. J. Vogel. 1999. Diversity of antimicrobial peptides and their mechanisms of action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1462:11-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fimland, G., V. G. Eijsink, and J. Nissen-Meyer. 2002. Mutational analysis of the role of tryptophan residues in an antimicrobial peptide. Biochemistry 41:9508-9515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedrich, C. L., A. Rozek, A. Patrzykat, and R. E. W. Hancock. 2001. Structure and mechanism of action of an indolicidin peptide derivative with improved activity against gram-positive bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 276:24015-24022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallivan, J. P., and D. A. Dougherty. 1999. Cation-pi interactions in structural biology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9459-9464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gazit, E., and Y. Shai. 1993. Structural and functional characterization of the alpha 5 segment of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin. Biochemistry 32:3429-3436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerneve, C. L., M. Seigneuret, and D. Marion. 1998. Interaction of the wheat endosperm lipid-binding protein puroindoline-a with phospholipids. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 360:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hancock, R. E. W., and R. Lehrer. 1998. Cationic peptides: a new source of antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 16:82-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hancock, R. E. W., T. Falla, and M. Brown. 1995. Cationic bactericidal peptides. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 37:135-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang, P. M., and H. J. Vogel. 1998. Structure-function relationships of antimicrobial peptides. Biochem. Cell Biol. 76:235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeener, J., B. H. Meier, P. Bachmann, and R. R. Ernst. 1979. Investigation of exchange processes by two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 71:4546-4553. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jing, W., H. N. Hunter, J. Hagel, and H. J. Vogel. 2003. The structure of the antimicrobial peptide Ac-RRWWRF-NH2 bound to micelles and its interactions with phospholipid bilayers. J. Pept. Res. 61:219-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson, B. A., and R. A. Blevins. 1994. NMRView: a computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR 4:603-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Killian, J. A., J. W. Timmermans, S. Keur, and B. De Kruijff. 1985. The tryptophans of gramicidin are essential for the lipid structure modulating effect of the peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 820:154-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koradi, R., M. Billeter, and K. Wüthrich. 1996. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graphics 14:51-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnamurthy, K., C. Balconi, J. E. Sherwood, and M. J. Giroux. 2001. Wheat puroindolines enhance fungal disease resistance in transgenic rice. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:1255-1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakowicz, J. R. 1999. Principles of fluorescence spectroscopy. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 29.Latal, A., G. Degovics, R. F. Epand, R. M. Epand, and K. Lohner. 1997. Structural aspects of the interaction of peptidyl-glycylleucine-carboxyamide, a highly potent antimicrobial peptide from frog skin, with lipids. Eur. J. Biochem. 248:938-946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawyer, C., S. Pai, M. Watabe, P. Borgia, T. Mashimo, L. Eagleton, and K. Watabe. 1996. Antimicrobial activity of a 13 amino acid tryptophan-rich peptide derived from a putative porcine precursor protein of a novel family of antibacterial peptides. FEBS Lett. 390:95-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKenzie, K. R., J. H. Prestegard, and D. M. Engelman. 1997. A transmembrane helix dimer: structure and implications. Science 276:131-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marion, D., M. F. Gautier, P. Joudrier, M. Ptak, M. Pezolet, M. Forest, D. C. Clark, and W. Broekaert. 1994. In Processing of the wheat kernel proteins—molecular and functional aspects, p. 175-180. Universita della Tuscia, Viterbo, Italy.

- 33.Matsuzaki, K., S. Nakai, T. Handa, Y. Takaishi, T. Fujita, and K. Miyajima. 1989. Hypelcin A, an alpha-aminoisobutyric acid containing antibiotic peptide, induced permeability change of phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biochemistry 28:9392-9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuzaki, K., K. Sugishita, N. Ishibe, M. Ueha, S. Nakata, K. Miyajima, and R. M. Epand. 1998. Relationship of membrane curvature to the formation of pores by magainin 2. Biochemistry 37:11856-11863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McElhaney, R. N. 1986. Differential scanning calorimetric studies of lipid-protein interactions in model membrane systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 864:361-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McElhaney, R. N. 1982. The use of differential scanning calorimetry and differential thermal analysis in studies of model and biological membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids 30:229-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris, C. F. 2002. Puroindolines: the molecular genetic basis of wheat grain hardness. Plant Mol. Biol. 48:633-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicolas, P., and A. Mor. 1995. Peptides as weapons against microorganisms in the chemical defense system of vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49:277-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nilges, M. 1995. Calculation of protein structures with ambiguous distance restraints. Automated assignment of ambiguous NOE crosspeaks and disulphide connectivities. J. Mol. Biol. 245:645-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oren, Z., and Y. Shai. 1998. Mode of action of linear amphipathic alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 47:451-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park, C.-B., H.-S. Kim, and S.-C. Kim. 1998. Mechanism of action of the antimicrobial peptide buforin II: buforin II kills microorganisms by penetrating the cell membrane and inhibiting cellular functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 244:253-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perczel, A., and M. Hollosi. 1996. Turns, p. 285-380. In G. D. Fasman (ed.), Circular dichroism and the conformational analysis of biomolecules. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 43.Rance, M., O. W. Sorenson, G. Bodenhausen, G. Wagner, R. R. Ernst, and K. Wüthrich. 1983. Improved spectral resolution in COSY 1H NMR spectra of proteins via double quantum filtering. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 117:479-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rapaport, D., and Y. Shai. 1991. Interaction of fluorescently labeled pardaxin and its analogues with lipid bilayers. J. Biol. Chem. 266:23769-23775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reithmeier, R. A. 1995. Characterization and modeling of membrane proteins using sequence analysis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5:491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rinaldi, A. C., M. L. Mangoni, A. Rufo, C. Luzi, D. Barra, H. Zhao, P. K. Kinnunen, A. Bozzi, A. Di Giulio, and M. Simmaco. 2002. Temporin L: antimicrobial, haemolytic and cytotoxic activities, and effects on membrane permeabilization in lipid vesicles. Biochem. J. 368:91-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rozek, A., C. L. Friedrich, and R. E. W. Hancock. 2000. Structure of the bovine antimicrobial peptide indolicidin bound to dodecylphosphocholine and sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles. Biochemistry 39:15765-15774. [PubMed]

- 48.Schibli, D. J., R. F. Epand, H. J. Vogel, and R. M. Epand. 2002. Tryptophan-rich antimicrobial peptides: comparative properties and membrane interactions. Biochem. Cell Biol. 80:667-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schibli, D. J., P. M. Hwang, and H. J. Vogel. 1999. Structure of the antimicrobial peptide tritrpticin bound to micelles: a distinct membrane-bound peptide fold. Biochemistry 38:16749-16755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schibli, D. J., R. C. Montelaro, and H. J. Vogel. 2001. The membrane-proximal tryptophan-rich region of the HIV glycoprotein, gp41, forms a well-defined helix in dodecylphosphocholine micelles. Biochemistry 40:9570-9578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schiffer, M., M. H. Chang, and F. J. Stevens. 1992. The functions of tryptophan residues in membrane proteins. Protein Eng. 5:213-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Selsted, M. E., M. J. Novotny, W. L. Morris, Y. Q. Tang, W. Smith, and J. S. Cullor. 1992. Indolicidin, a novel bactericidal tridecapeptide amide from neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 267:4292-4295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shai, Y. 1999. Mechanism of the binding, insertion and destabilization of phospholipid bilayer membranes by alpha-helical antimicrobial and cell non-selective membrane-lytic peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1462:55-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strom, M. B., O. Rekdal, and J. S. Svendsen. 2002. Antimicrobial activity of short arginine- and tryptophan-rich peptides. J. Pept. Sci. 8:431-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tassin, S., W. F. Broekaert, D. Marion, D. Acland, M. Ptak, F. Vovelle, and P. Sodano. 1998. Solution structure of Ace-AMP1, a potent antimicrobial protein extracted from onion seeds. Structural analogies with plant nonspecific lipid transfer proteins. Biochemistry 37:3623-3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tinoco, L. W., A. Silva, A. Leite, and A. Valente. 2002. NMR structure of PW2 bound to SDS micelles. A tryptophan-rich anticoccidial peptide selected from phage display libraries. J. Biol. Chem. 277:36351-36356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vogel, H. J., D. J. Schibli, W. Jing, E. M. Lohmeier-Vogel, R. F. Epand, and R. M. Epand. 2002. Towards a structure-function analysis of bovine lactoferricin and related tryptophan- and arginine-containing peptides. Biochem. Cell Biol. 80:49-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wenk, M. R., and J. Seelig. 1998. Magainin 2 amide interaction with lipid membranes: calorimetric detection of peptide binding and pore formation. Biochemistry 37:3909-3916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wieprecht, T., M. Beyermann, and J. Seelig. 1999. Binding of antibacterial magainin peptides to electrically neutral membranes: thermodynamics and structure. Biochemistry 38:10377-10387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wimley, W. C., and S. H. White. 1996. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:842-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woody, R. W. 1994. Contributions of tryptophan side chains to the far-ultraviolet circular dichroism of proteins. Eur. Biophys. J. 23:253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu, M., E. Maier, R. Benz, and R. E. W. Hancock. 1999. Mechanism of interaction of different classes of cationic antimicrobial peptides with planar bilayers and with the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 38:7235-7242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wüthrich, K. 1986. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids, p. 130-161. John Wiley and Sons, New York, N.Y.

- 64.Yang, S.-T., S. Shin, Y.-C. Kim, Y. Kim, K.-S. Hahm, and J. Kim. 2002. Conformation-dependent antibiotic activity of tritrpticin, a cathelicidin-derived antimicrobial peptide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 296:1044-1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yau, W.-M., W. C. Wimley, K. Gawrisch, and S. H. White. 1998. The preference of tryptophan for membrane interfaces. Biochemistry 37:14713-14718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zasloff, M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang, Y.-P., R. N. A. H. Lewis, and R. N. McElhaney. 1997. Calorimetric and spectroscopic studies of the thermotropic phase behavior of the n-saturated 1,2 diacylphosphatidylglycerols. Biophys. J. 72:779-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]