Abstract

The cell wall of the gram-positive bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum contains a channel (porin) for the passage of hydrophilic solutes. The channel-forming polypeptide PorA is a 45-amino-acid acidic polypeptide with an excess of four negatively charged amino acids, which is encoded by the 138-bp gene porA. porA was deleted from the chromosome of C.glutamicum wild-type strain ATCC 13032 to obtain mutant ATCC 13032ΔporA. Southern blot analysis demonstrated that porA was deleted. Lipid bilayer experiments revealed that PorA was not present in the cell wall of the mutant strain. Searches within the known chromosome of C. glutamicum by using National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST and reverse transcription-PCR showed that no other PorA-like protein is encoded on the chromosome or is expressed in the deletion strain. The porA deletion strain exhibited slower growth and longer growth times than the C. glutamicum wild-type strain. Experiments with different antibiotics revealed that the susceptibility of the mutant strain was much lower than that of the wild-type C. glutamicum strain. The results presented here suggest that PorA represents a major hydrophilic pathway through the cell wall and that C. glutamicum contains cell wall channels which are not related to PorA.

Corynebacterium glutamicum has been studied for production of the flavor-enhancing amino acid glutamate and other amino acids through fermentation processes on an industrial scale since its original isolation from a soil sample from the Tokyo Zoo (8, 17, 19, 21, 35, 47). Together with other corynebacteria, such as Corynebacterium callunae and members of the genera Rhodococcus,Gordona,Tsukamurella, Dietzia, Mycobacterium, and Nocardia, this bacterium belongs to a broad, diverse group of mycolic acid-containing actinomycetes, the mycolata. Besides the thick peptidoglycan layer, members of the mycolata contain large amounts of lipids in form of mycolic acids and other lipids in their cell walls (2, 11, 32). The mycolic acids are linked through ester bonds to the arabinogalactan attached to the murein of the cell wall (26). The chain lengths of these 2-branched, 3-hydroxylated fatty acids vary considerably within the mycolic acid-containing taxa. Thus, especially long mycolic acids have been found in mycobacteria (60 to 90 carbon atoms) and Tsukamurella species (64 to 74 carbon atoms); the mycolic acids are medium size in Gordona species (52 to 66 carbon atoms) and Nocardia species (46 to 58 carbon atoms) and short in corynebacteria (22 to 38 carbon atoms) (6, 7, 13, 26, 27, 51). The permeability of the cell walls of members of the mycolata for hydrophilic solutes is low (16), presumably because the mycolic acid layer represents a second permeability barrier in addition to the cytoplasmic membrane, similar to the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria (25, 31). On the other hand, it is also clear that the mycolic acids are not sufficient to cover the whole surface of corynebacteria, which means that the noncovalently linked lipids play an important role in the permeability barrier formed by the cell wall (33).

In recent years it has been demonstrated that like the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, the cell wall of mycobacteria contains channels that allow the permeation of hydrophilic solutes (44, 46). Similar channel-forming proteins have been identified in the cell walls of other members of the mycolata, including C. glutamicum (22, 23, 24, 29, 34). Two common features of these cell wall channels are that they form wide, water-filled pores and that they have negative charges, which results in cation selectivity. The gene encoding the cell wall channel of C. glutamicum has been identified (24). porA comprises only 138 bp and codes for a small 45-amino-acid acidic polypeptide with an excess of four negatively charged amino acids, which is consistent with the high cation selectivity of the PorA cell wall channel. The calculated molecular mass is close to 5 kDa, which is in agreement with the apparent molecular mass deduced from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis (22). In Southern blot analyses, two or three bands occurred when low-stringency conditions were used, compared to the single band observed when high-stringency conditions were used. This might indicate that the chromosome of C. glutamicum contains several genes that could encode cell wall channels. No hybridization of chromosomal DNA from other corynebacteria and a C. glutamicum porA probe was detected under high-stringency conditions. However, under low-stringency conditions, some hybridization indicated that C. callunae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, and Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis may contain porA-like genes (24). The PorA protein does not contain an N-terminal sorting signal for targeting to the cell wall. The absence of any obvious signal peptide suggests that translocation of this protein through the cytoplasmic membrane involves an export system that is different from the Sec system responsible for protein export in gram-positive bacteria (9, 24).

In this paper we describe deletion of the porA gene from the C. glutamicum chromosome. Deletion of the gene was confirmed and the absence of PorA was checked by lipid bilayer experiments. No PorA-like activity was detected in protein extracts obtained from mutant cells, and no PorA-like protein was synthesized in the mutant strain. The antibiotic susceptibility pattern for several drugs, including ampicillin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol, changed drastically, and a reduction in susceptibility to gentamicin was observed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

For most experiments C.glutamicum ATCC 13032 was grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 30°C. For growth experiments MM1 minimal medium was used (3). This medium contained (per liter of distilled water) 5 g of ammonium sulfate, 5 g of urea, 2 g of KH2PO4, and 2 g of K2HPO4; the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with NaOH, and the medium was supplemented with 40 g of glucose per liter, 10 mg of CaCl2per liter, and 0.25 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O per liter. Escherichia coli Top10F′ (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), which was used for cloning, and E. coli S17-1 (41), which was used for conjugation, were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Difco) at 37°C.

Glutamate excretion.

Glutamate excretion experiments were performed in the minimal medium (17) supplemented with 0.5 μg of biotin per liter. The bacteria were grown overnight in this medium. For glutamate production the preculture was diluted 1:10,000 in the same minimal medium without biotin. The glutamate content of the culture supernatant was determined every hour (12).

Concentrations of antibiotics.

Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany), 100 μg/ml; kanamycin (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany), 25 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany), 40 and 20 μg/ml; nalidixic acid (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany), 50 μg/ml; gentamicin (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany), 5 μg/ml; norfloxacin (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany), 5 μg/ml; and tetracycline (AppliChem), 12.5 μg/ml.

Test for susceptibility to antibiotics.

Qualitative tests were performed by using filter disks obtained from Oxoid (Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom). Overnight cultures in the appropriate medium were diluted 1:100; then 100 μl of each culture containing approximately 107 cells/ml was spread onto BHI agar medium (Difco) at 30°C. Five-microliter portions of the diluted 1:1,000 stock solutions of the different antibiotics were added to each disk. The diameters of the inhibition zones were measured after 16 and 24 h.

Construction of plasmids.

Shuttle plasmid pK18mobsacB (38), which confers kanamycin resistance and sucrose sensitivity, was opened at the multiple cloning site with EcoRI-BamHI. For amplification of porA flanking regions, we used primers that contained EcoRI and PspAI sites (upstream primers Por3EcoRI and Por4PspAI) (Table 1) and PspAI and BamHI sites (downstream primers Por5PspAI and Por6BamHI) (Table 1). After 30 cycles of PCR, performed with a proofreading polymerase (AccuTaq; Sigma, Steinheim, Germany), the two products (F1 and F2) were separately digested with PspAI and ligated overnight with T4 DNA ligase (MBI Fermentas, St. Leon-Roth, Germany). The ligated product (approximately 1,400 bp) was amplified by PCR and double digested with EcoRI-BamHI (MBI Fermentas). This product was ligated to the linear vector to obtain plasmid pNC01.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this studya

| Oligonucleotide | Positionb | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Por1 | 1-21 (downstream) | ATGGAAAACGTTTAGAGTTCC |

| Por2 | 138-117 (downstream) | TTAGCCAAGCAGACCGATGAG |

| Por3 | 800-779 (upstream) | ACCTCAATTGCCCTCCCGC |

| Por4 | 0-24 (upstream) | TTTAAATTCTCCTATTAAGAGTTG |

| Por5 | 139-167 (downstream) | TTAACTTCGCCCACGGGC |

| Por6 | 862-841 (downstream) | TCAGTGTCGGTGTAACGGAAC |

| Por7 | 45-24 (upstream) | CCTTCCCCCTTCCCCCTCATC |

| GlutOD | 105-138 (downstream) | GCAGTTGCTGACCTCATCGGTCTGCTTGGCTAA |

| Por3EcoRI | 760-734 (upstream) | GCGTGTCAAAAGGAATTCCTTTTCGA |

| Por4PspAI | 18-20 (downstream) | GAGTTGAGATGCCCGGGAAG |

| Por5PspAI | 139-158 (downstream) | TTAACTTCGCCCCCGGGCAA |

| Por6BamHI | 766-745 (downstream) | CGCACAGGATCCACCTGGCGG |

Construction of the porA deletion mutant of C. glutamicum.

E. coli S17-1 was transformed with pNC01 and selected on kanamycin-containing LB agar plates overnight at 37°C. Single colonies were grown in liquid LB medium at 37°C until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1 was reached. To transfer pNC01 into C. glutamicum, the E. coli cells were mixed with C. glutamicum recipient cells on cellulose nitrate filters (HAW P02400; pore size, 0.45 μm; Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany) on LB agar containing 50 μg of kanamycin/ml and 50 μg of nalidixic acid/ml (to eliminate the donor E. coli). After transfer of the construct pNC01 into C. glutamicum, the plasmid could establish itself only by integration into the chromosome via homologous recombination. Transconjugants were selected on BHI agar containing either 10% sucrose or 50 μg of kanamycin/ml. Six colonies were able to grow on kanamycin and not on sucrose (Kanr Sucr phenotype). To select excision of the plasmid after the second crossover event, one of the colonies was grown in nonselective BHI medium at 30°C for 2 days. This culture was plated onto BHI agar containing 10% sucrose and incubated overnight at 30°C. Cells able to grow in this medium lost the plasmid due to a second crossover event, which either restored the wild-type phenotype or led to the mutant strain. Approximately 200 colonies were picked and streaked onto BHI agar plates containing either kanamycin or sucrose. About 50% of the colonies (98 of 200 colonies) were kanamycin sensitive and could grow in sucrose, indicating that there had been excision of the plasmid by a second crossover event. Twenty of these colonies were tested by PCR screening with Por1 and Por2 primers specific for porA to select the deletion mutant from the restored wild-type genotype. Four colonies were negative, indicating that there was deletion of the porA gene in C. glutamicum ATCC 13032. One of these colonies was selected for further experiments and was designated C. glutamicum ATCC 13032ΔporA.

Southern blot analysis.

For Southern blot analysis, chromosomal DNA was isolated from both the wild-type strain and the ATCC 13032ΔporA mutant strain (49). The Southern blot analysis was performed by using standard procedures (18, 37). A 3′ digoxigenin-labeled 33-bp fragment of the 3′ end of the porA gene (sequence positions 105 to 138) (GlutOD) was used as the probe (Table 1). High-stringency conditions were achieved by hybridizing blots at 60°C, and medium-stringency hybridization was performed at 57°C. The hybridized digoxigenin probe was detected with an enzyme immunoassay by using anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (anti-digoxigenin Fab fragments conjugated with alkaline phosphatase) and a subsequent enzyme-catalyzed color reaction with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) and nitroblue tetrazolium salt; this produced a blue precipitate, which was used to visualize hybrid molecules.

PCR.

Primers Por1 and Por2 (Table 1) were used for PCR amplification of the porA gene. For PCR screening of the mutant DNA, one big colony was picked and boiled in 50 μl of water, and 1 μl was used as a template. When chromosomal DNA had to be amplified, 1 μl of a 1:10 dilution of the DNA extract was used. Annealing was performed at 60°C with 1 min of extension at 72°C by using Taq polymerase (36). For an additional control, primers Por3 and Por6 (Table 1) for the 1,800-bp fragment containing the porA gene and flanking regions were also used for PCR with the chromosomal DNA extracted from a ΔporA colony and wild-type strain ATCC 13032 as the template. The annealing temperature in this case was 64°C. Primer Por7 (Table 1) was used for sequencing the PCR product.

RT-PCR.

Total mRNA was isolated from disrupted cells by using an RNeasy kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Purified RNA was treated with 2 U of DNase I (Ambion, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom) in 0.1 volume of 10× DNase buffer for 30 min at 37°C to remove the DNA. After this treatment, 5 μl was loaded onto a 0.8% agarose gel to test the integrity. Two sharp bands (23S rRNA and 16S rRNA) were visible with each of the samples. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed in a two-step reaction with an enhanced avian HS RT-PCR kit (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) with random nonamers. The cDNA product was used for PCR (20) with the porA-specific primers Por1 and Por2 (Table 1). The annealing temperature was 60°C. For a negative control, 5 μl of the DNase-treated RNA was used for a direct PCR with both primers specific for porA, and the same program was used for the PCR after the RT reaction.

Isolation and purification of the channel-forming protein from the cell wall of whole bacteria.

The cell wall channel-forming protein of C. glutamicum was extracted and purified as described previously (22).

Solid-phase synthesis of PorA.

The 45-amino-acid PorA molecule was synthesized by using solid-phase synthesis of polypeptides. The polypeptide was purified by high-performance liquid chromatography.

SDS-PAGE.

SDS-PAGE was performed with Tricine-containing gels (39). The gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or with colloidal Coomassie blue (28).

Electrotransformation.

Electrotransformation was performed by using a slightly modified standard method (48).

Lipid bilayer experiments.

The methods used for the lipid bilayer experiments have been described previously in detail (5).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Deletion of porA.

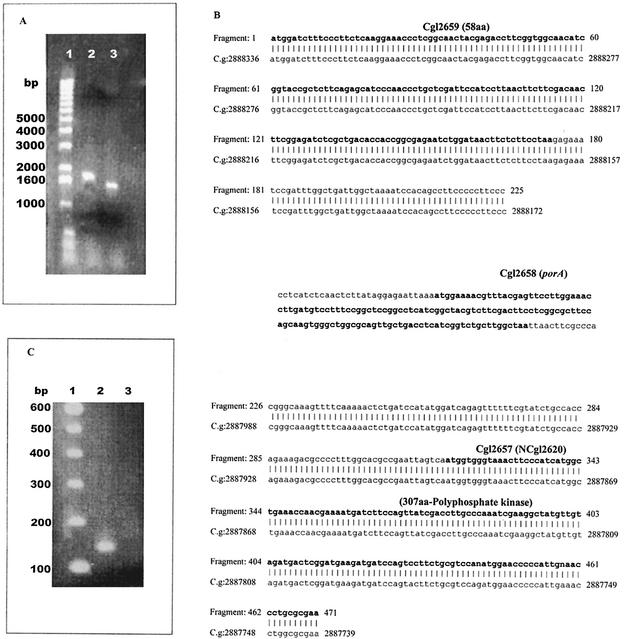

In previous studies it was shown that the cell wall of C. glutamicum contains a cation-selective channel with high conductance (22). Investigation of the single-channel properties demonstrated that the channel is wide and water filled and has a diameter of about 2.2 nm. Further studies of PorA revealed that its permeability is controlled by negative point charges. PorA is a small hydrophobic polypeptide that is 45 amino acids long. The gene that encodes it, porA, comprises 138 bp (24). To elucidate the function of the cell wall channel (porin) formed by the PorA protein of C. glutamicum, the porA gene was deleted from the chromosome of C. glutamicum wild- type strain ATCC 13032 by using the vector pK18mobsacB as described previously (14, 38). This vector contains two selectable markers, the Kmr gene conferring resistance to kanamycin and the sacB gene, which confers sucrose sensitivity to gram-negative bacteria and some gram-positive bacteria (10, 15, 40, 43). Two selectable markers were used to reduce the number of possible mutants which might contain crossovers (38). Both up- and downstream flanking regions of the gene (F1 and F2, respectively) (Table 1 and Fig. 1B) were amplified with primers Por3EcoRI and Por4PspAI and with primers Por5PspAI and Por6BamHI. The final product was ligated to the shuttle vector and transformed into C. glutamicum. From the six colonies which had the Kanr Sucs phenotype, one colony was chosen to continue with the second crossover event; 98 colonies from this event were able to grow in the presence of sucrose but not in the presence of kanamycin. By using PCR screening, 20 colonies were tested with the PorA primers (Por1 and Por2), and 4 colonies were found to be negative. Primers for the whole flanking region of porA (Por3 to Por6) (Table 1) were used again in a PCR, and wild-type and ΔporA chromosomal DNA were used as templates. Two different bands were observed in an 0.8% agarose gel (Fig. 2A); one band was at about 1,800 bp after hybridization with the wild-type product, and one band was at a little more than 1,600 bp after hybridization with the deletion product, indicating that an approximately 150-bp region (containing the porA gene) was deleted. Deletion of porA within the genome of C. glutamicum is shown in Fig. 2B. Together with porA 30 bp before the start codon and 13 bp after the stop codon were removed from the chromosome of C. glutamicum, but no open reading frame before or after porA was touched by the deletion. This means that only the deletion of porA was responsible for the phenotype observed.

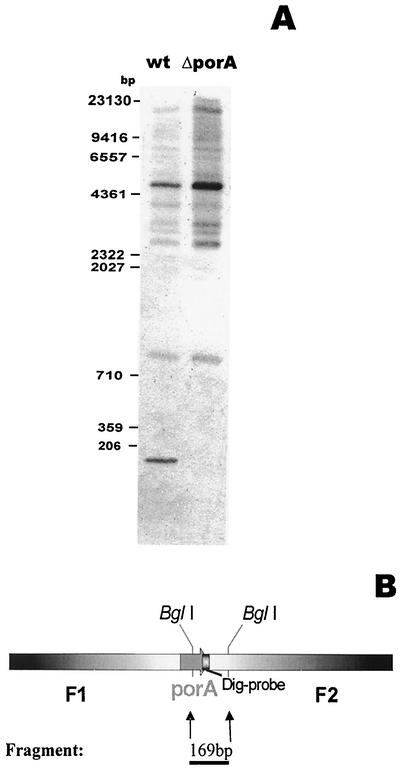

FIG. 1.

Southern blot analysis of C. glutamicum wild-type ATCC 13032 and C. glutamicum ATCC 13032ΔporA cells. (A) Chromosomal DNA from wild-type cells (wt) and the ΔporA mutant strain (ΔporA) were digested with restriction enzyme BglI, subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred onto a nylon membrane, and probed with a digoxigenin-labeled oligonucleotide corresponding to the last 33 bp of the porA gene. (B) Schematic representation from the 169-bp fragment released in the chromosome of the wild-type C. glutamicum strain after cleavage with BglI. Dig, digoxigenin

FIG. 2.

(A) Agarose (0.8%) gel from PCR. DNA from C. glutamicum wild-type and ΔporA mutant strains were used as templates for PCR performed with primers Por3 to Por6 (Table 1) for the 1,800-bp fragment of the whole flanking region of porA. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 0.8% agarose gel. Lane 1, 1-kb ladder; lane 2, PCR product obtained by using wild-type DNA; lane 3, PCR product obtained by using DNA from the ΔporA mutant strain. Note that the PCR product obtained with the ΔporA mutant DNA (lane 3) is smaller, indicating that there was an approximately 150-bp deletion. (B) Alignment of the deletion PCR product with the wild-type sequence. To see how many base pairs were deleted by homologous recombination, the PCR product from lane 3 of the gel was used for sequencing. The missing base pairs are shown without alignment. The boldface type indicates the three open reading frames (the numbers above the sequences are accession numbers). The GenBank accession number of the genome of C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 is NC_003450. Proteins smaller than 60 amino acids (aa) were excluded from the sequence when it was reviewed. This is the reason why porA and the 58-amino-acid protein upstream have just one accession number, whereas the polyphosphate kinase has two accession numbers, one from the first submission and the second from the reviewed submission (in parentheses). As the data show, the homologous recombination did not affect any other protein; it affected only the entire porA gene and some base pairs from the intergenic regions up- and downstream. The numbers before the chromosomal DNA from the GenBank are the positions in the whole genome. (C) RT of total mRNA from wild-type C. glutamicum and the ΔporA mutant strain. Total mRNA was converted into cDNA and amplified with the porA-specific primers Por1 and Por2 (Table 1). Lane 1, 100-bp ladder: lane 2, PCR amplification of the wild-type strain; lane 3, PCR amplification of the ΔporA mutant. Note that no amplification product was detected for the deletion mutant (lane 3).

To determine whether another porA-like gene(s) was transcribed in the deletion mutant, total RNA was isolated from both C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 and the ΔporA mutant, which was essentially free of genomic DNA (data not shown). By using RT, the total mRNA of the C. glutamicum wild-type strain and the ΔporA mutant were converted into cDNA with random nonamers and then amplified with the porA-specific primers Por1 and Por2. As shown in Fig. 2C only the mRNA of the C. glutamicum wild-type strain contained a signal that was amplified with primers Por1 and Por2. No signal was detected by RT-PCR when RNA from the ΔporA mutant amplified with porA-specific primers Por1 and Por2 was used. This result suggested that the ΔporA mutant did not contain the mRNA for any PorA-like protein.

The finding that the chromosome of C. glutamicum contains only one gene for a cation-selective, wide PorA-like channel is in contrast to the situation in another member of the group mycolata, Mycobacterium smegmatis. In the latter organism mspA codes for the 20-kDa subunit of the cell wall channel, MspA, which forms wide, cation-selective channels similar to those formed by PorA (45, 30, 22). The chromosome of M. smegmatis contains four genes coding for MspA-like proteins (42), which have only minor differences in the primary sequence compared to the MspA sequence. porA is definitely unique in the chromosome of C. glutamicum.

Southern blot hybridization.

When the DNA of wild-type C. glutamicum was digested with BglI, the porA sequence was released as a 169-bp fragment (Fig. 1). This fragment was detected in Southern blot experiments performed with wild-type chromosomal DNA but not with the DNA of the deletion mutant (Fig. 2A, lane 2). This result demonstrated that the porA gene was not present in the mutant strain C. glutamicum ATCC 13032ΔporA. Figure 1A shows that there were many hybridization events with wild-type and ΔporA DNA when restriction enzyme BglI was used. The reason for this is the G+C-rich chromosome of C. glutamicum, which leads to many cleavage sites for BglI and allows many mismatches. A National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST search for sequences homologous to porA within the known genome of C. glutamicum suggested that there are many short stretches homologous to the 33-bp fragment at the 3′ end of the porA gene (GlutOD) used as a probe that are between 15 and 20 bp long. However, these stretches are parts of genes that are much longer than porA and that have nothing to do with the function of PorA as a cell wall channel. This result indicated that the chromosome of C. glutamicum does not code for a second porA-like gene and that porA is unique. This result was supported by the RT-PCR experiment. Similarly, cleavage of the chromosome with BamHI followed by Southern hybridization with CorYSB1 under high-stringency conditions (60°C) showed that there was only one hybridization event (24).

Antibiotic resistance.

The antibiotic susceptibility of the ΔporA mutant was tested qualitatively by using the filter disk method and measuring the diameter of the zone of growth inhibition. The results obtained for the wild-type strain and the ΔporA mutant are summarized in Table 2. Deletion of PorA had a substantial influence on the antibiotic susceptibility of the ΔporA mutant strain, which was resistant to ampicillin and tetracycline under these conditions. The results showed that the wild-type cells were susceptible to a variety of antibiotics, such as ampicillin, kanamycin, streptomycin, and tetracycline, and were somewhat less susceptible to gentamicin. Norfloxacin, chloramphenicol, and cephaloridine did not inhibit growth at the concentrations used. Deletion of PorA resulted in a substantial increase in antibiotic resistance. No inhibition of growth was observed for ampicillin and tetracycline under the conditions tested here. The zones of inhibition for kanamycin and streptomycin were drastically reduced. This result indicated that PorA plays an important role in the transport of antibiotics across the cell wall of C. glutamicum, probably because of its large diameter and its preference for positively charged solutes.

TABLE 2.

Diameters of the zones of inhibition of growth of the C. glutamicum wild-type and ΔporA mutant strains with different antibioticsa

| Antibiotic | Diam of inhibition zone (mm)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| C. glutamicum wild type | C. glutamicum ΔporA mutant | |

| Ampicillin | >25 | NI |

| Kanamycin | >25 | 5 |

| Streptomycin | >25 | 4 |

| Tetracycline | >25 | NI |

| Gentamicin | 5 | 2 |

Five-microliter portions of the diluted 1:1,000 stock solutions of the different antibiotics (see Materials and Methods) were added to the discs. The diameters of the inhibition zones were measured after 16 and 24 h. NI, no inhibition of growth.

Growth experiments and glutamate production.

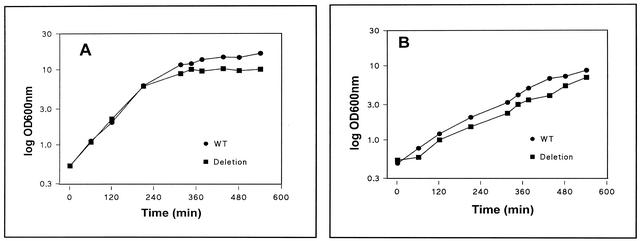

The effect of deletion of PorA on the growth of C. glutamicum was also studied (Fig. 3). Both the wild-type and ΔporA strains exhibited approximately the same growth rate during the exponential phase in BHI medium. However, the ΔporA mutant showed impaired growth in the late logarithmic and stationary phases (Fig. 3A). The ΔporA mutant showed reduced growth on minimal medium at all stages (Fig. 3B). The mutant cells tended to clump when they were centrifuged, and the cell pellet was difficult to resuspend, which suggested that deletion of PorA changed the cell wall structure. To check that the clumping did not occur during growth, the C. glutamicum wild-type and ΔporA mutant strains were grown in parallel cultures. Samples were taken at different times, and appropriate dilutions were plated to determine the number of CFU. The experiments were performed in duplicate. Independent of the growth phase, similar numbers of CFU were obtained for the two strains. For example, an OD600 of 1 corresponded to 1.4 × 108 and 1.5 × 108 CFU for wild-type and mutant cells, respectively. These results indicate that secondary effects of cell aggregation on the OD600 are very unlikely.

FIG. 3.

Growth curves for wild-type C. glutamicum and the ΔporA mutant shown on a semilogarithmic scale. (A) C. glutamicum wild type (WT) and ΔporA mutant grown in rich medium (BHI medium) for about 9 h at 30°C. (B) C. glutamicum and ΔporA mutant grown in minimal medium for about 9 h at 30°C.

The growth experiments suggest that the wild-type and ΔporA mutant strains show the same growth in the early log phase but not in the late log phase. In principle, mutant cell growth should slow in this phase because of a decreased rate of nutrient influx. A possible explanation for the unexpected behavior might be the extremely high concentrations of nutrients in typical C. glutamicum media, which exceed the concentrations in E. coli media by far. In this case, diffusion might be sufficient to promote growth at high nutrient concentrations and low cell densities (as observed). Consequently, at the end of the culture period, at high cell densities and low nutrient concentrations, simple diffusion pathways should become limiting, which corresponds exactly to the growth phenotype observed. It is noteworthy that it has been demonstrated that cell walls are only rate limiting for diffusion of nutrients at low substrate concentrations (50) or when porins are modified or deleted (1). In fact, growth experiments with the wild-type and mutant strains at lower substrate concentrations (diluted BHI medium) showed that growth in the early log phase was always the same but the growth of the wild type and the growth of the ΔporA mutant differed at earlier times (and lower OD600). We also checked the production of glutamate by the ΔporA mutant and found no difference from the production of glutamate by the wild-type strain (data not shown), probably because the cell walls of the two C. glutamicum strains do not have different permeability properties for export of the negatively charged glutamate.

Lipid bilayer experiments.

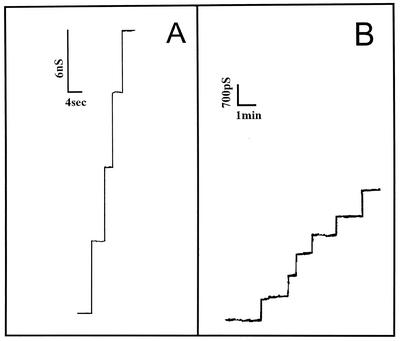

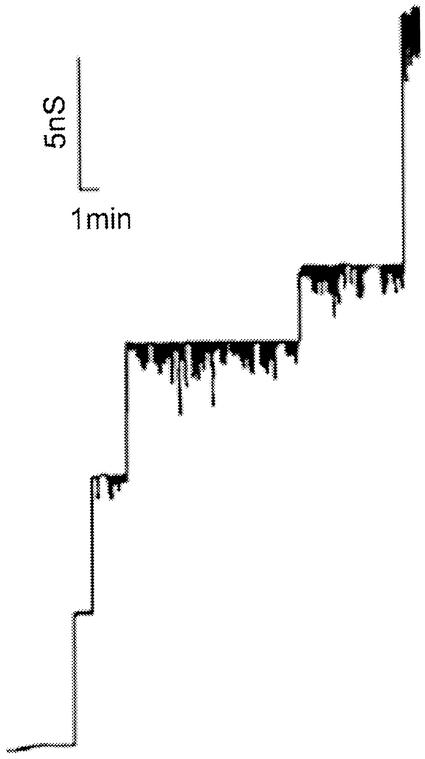

Lipid bilayer membrane measurements were obtained with cell wall extracts of the deletion mutant. First, an organic extract precipitated with cold ether (dissolved in 0.4% N,N-dimethyldodecylamine-N-oxide [LDAO]) from each strain was added to one side of a membrane. Only in the case of the wild-type strain did we observe the typical 5.5-nS channels in 1 M KCl (Fig. 4A). In the case of extracts from the ΔporA mutant no 5.5-nS channels were observed even when the concentration of the extract was more than 50-fold higher than the concentration of the extract from the wild-type cells (Fig. 4B). Instead, we observed channels which had a single-channel conductance of about 0.7 nS in 1 M KCl. Histograms of the current fluctuations measured under both conditions supported the hypothesis that the 5.5-nS channels were found exclusively in extracts of wild-type cells, whereas the 0.7-nS channels were observed in extracts of the ΔporA mutant (data not shown). These channels seemed to be anion selective because their single-channel conductance in 1 M LiCl was the same as that in 1 M KCl, whereas it was considerably less in 1 M potassium acetate (0.25 nS). These results indicate that the cell wall of the mutant strain also contains pores that are either induced in the mutant or are present together with PorA but are difficult to detect because they have a much smaller single-channel conductance than PorA pores. This means that gram-positive bacteria can contain several different cell wall channels, similar to the situation in the outer membrane of the well-studied gram-negative bacteria (4). At least for high substrate concentrations, these channels are able to take over part of the function of PorA and allow substrate uptake from the external medium. We are trying to identify these channels. The presence of other channels may explain why deletion of porA is not lethal for the cell.

FIG. 4.

Single-channel recordings of diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine-phosphatidylserine (molar ratio, 4:1)-n-decane membranes in the presence of 5 μg of a chloroform methanol extract of whole C. glutamicum wild-type cells per ml precipitated with ether and dissolved in 0.4% LDAO-10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) (A) and 250 μg of the chloroform methanol extract of whole C. glutamicum ΔporA mutant cells per ml precipitated with ether and dissolved in 0.4% LDAO-10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). The aqueous phase contained unbuffered 1 M KCl (pH 6). The applied voltage was 20 mV, and the temperature was 20°C.

It is possible that PorA is an essential part of a channel-forming complex that requires other components for activity. Therefore, we performed single-channel experiments with a synthetic PorA peptide produced by solid-phase synthesis. Figure 5 shows that we observed the same channels that we observed with PorA purified from wild-type C. glutamicum, although the activity was somewhat lower. This result suggests that PorA alone is responsible for the formation of the 5.5-nS channels in 1 M KCl. The activity of the synthetic polypeptide that forms the smaller channels may be caused by an unidentified modification of the serine at position 15 of PorA (24).

FIG. 5.

Single-channel recording of a diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine-phosphatidylserine (molar ratio, 4:1)-n-decane membrane in the presence of 100 ng of synthetic PorA per ml dissolved in 0.4% LDAO-10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8). The aqueous phase contained 1 M unbuffered KCl (pH 6). The applied voltage was 20 mV, and the temperature was 20°C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elke Maier for help with the membrane experiments, A. Wittmann for help with the growth experiments, and Christian Andersen for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Be 865/9-4) and by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achouak, W., T. Heulin, and J. M. Pages. 2001. Multiple facets of bacterial porins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 199:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barksdale L. 1981. The genus Corynebacterium, p. 1827-1837. In M. P. Starr, H. Stoll, H. G. Truper, A. Balows, and H. G. Schlegel (ed.), The prokaryotes. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 3.Beckers, G., L. Nolden, and A. Burkovski. 2000. Glutamate synthase of Corynebacterium glutamicum is not essential for glutamate synthesis and is regulated by the nitrogen status. Microbiology 147:2961-2970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benz, R. 2001. Porins—structure and function, p. 227-246. In G. Winkelmann (ed.), Microbial transport systems. WILEY-VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 5.Benz, R., K. Janko, W. Boos, and P. Lauger. 1978. Formation of large, ion-permeable membrane channels by the matrix protein (porin) of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 511:305-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan, P. J., and H. Nikaido. 1995. The envelope of mycobacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64:29-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daffé, M., P. J. Brennan, and M. McNeil. 1990. Predominant structural features of the cell wall arabinogalactan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as revealed through characterization of oligoglycosyl alditol fragments by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and by 1H and 13C NMR analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6734-6743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggeling, L., and H. Sahm. 1999. Glutamate and l-lysine: traditional products with impetuous developments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 52:146-153. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freudl, R. 1992. Protein secretion in gram-positive bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 23:231-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gay, P., D. Le Coq, M. Steinmetz, T. Beckelmann, and C. I. Kado. 1985. Positive selection procedure for entrapment of insertion sequence elements in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 164:918-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodfellow, M., M. D. Collins, and D. E. Minnikin. 1976. Thin-layer chromatographic analysis of mycolic acid and other long-chain components in whole-organism methanolysates of coryneform and related taxa. J. Gen. Microbiol. 96:351-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutmann, M., C. Hoischen, and R. Krämer. 1992. Carrier-mediated glutamate secretion by Corynebacterium glutamicum under biotin limitation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1112:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt, J. G., N. R. Krieg, P. H. A. Sneath, J. T. Staley, and S. T. Williams. 1994. Nocardioform actinomycetes, p. 625-650. In Bergey's manual of determinative bacteriology, 9th ed. The Williams & Wilkins Co, Baltimore, Md.

- 14.Husson, R. N., B. E. James, and R. A. Young. 1990. Gene replacement and expression of foreign DNA in mycobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:519-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jäger, W., A. Schäfer, A. Pühler, G. Labes, and W. Wohlleben. 1992. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis sacB gene leads to sucrose sensitivity in the gram-positive bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum but not in Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 174:5462-5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarlier, V., and H. Nikaido. 1990. Permeability barrier to hydrophilic solutes in Mycobacterium chelonei. J. Bacteriol. 172:1418-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keilhauer, C., L. Eggeling, and H. Sahm. 1993. Isoleucine synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum: molecular analysis of the ilvB-ilvN-ilvC operon. J. Bacteriol. 175:5595-5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khandjian, E. W. 1987. Optimized hybrization of DNA blotted and fixed to nitrocellulose and nylon membranes. Bio/Technology 5:165. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinoshita, S., S. Udaka, and M. Shimono. 1957. Studies on the amino acid fermentation. Production of l-glutamate by various microorganisms. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 3:193-205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohler, T., D. Aautrost, A. K. Laner, A. K. Rost, B. Thamm, Pustowoi, and D. Labner. 1995. Quantitation of mRNA by polymerase chain reaction: nonradioactive PCR methods. Editorial Springer, Berlin, Germany.

- 21.Leuchtenberger, W. 1996. Amino acids—technical production and use. Products of primary metabolism, p. 455-502. In M. Roehr (ed.), Biotechnology, vol. VI. VCH, Weinheim, Germany.

- 22.Lichtinger, T., A. Burkovski, M. Niederweis, R. Kramer, and R. Benz. 1998. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of the cell wall porin of Corynebacterium glutamicum: the channel is formed by a low molecular mass polypeptide. Biochemistry 37:15024-15032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lichtinger, T., B. Heym, E. Maier, H. Eichner, S. T. Cole, and R. Benz. 1999. Evidence for a small anion-selective channel in the cell wall of Mycobacterium bovis BCG besides a wide cation-selective pore. FEBS Lett. 454:349-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichtinger, T., F. G. Rieß, A. Burkovski, F. Engelbrecht, D. Hesse, H. D. Kratzin, R. Krämer, and R. Benz. 2001. The low-molecular-mass subunit of the cell wall channel of the Gram-positive Corynebacterium glutamicum. Immunological localization, cloning and sequencing of its gene porA. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:462-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, J., C. E. Barry III., G. S. Besra, and H. Nikaido. 1996. Mycolic acid structure determines the fluidity of the mycobacterial cell wall. J. Biol. Chem. 271:29545-29551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minnikin, D. E. 1987. Chemical targets in cell envelopes, p. 19-43. In M. Hopper (ed.), Chemotherapy of tropical diseases. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, United Kingdom.

- 27.Minnikin, D. E., P. V. Patel, and M. Goodfellow. 1974. Mycolic acids of representative strains of Nocardia and the ′rhodochrous' complex. FEBS Lett. 39:322-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neuhoff, V., N. Arold, D. Taube, and W. Ehrhardt. 1988. Improved staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels including isoelectric focusing gels with clear background at nanogram sensitivity using Coomassie brilliant blue G-250 and R-250. Electrophoresis. 9:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niederweis, M., E. Maier, T. Lichtinger, R. Benz, and R. Krämer. 1995. Identification of channel-forming activity in the cell wall of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 177:5716-5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niederweis, M., S. Ehrt, C. Heinz, U. Klöcker, S. Karosi, K. M. Swiderek, L. W. Riley, and R. Benz. 1999. Cloning of the mspA gene encoding a porin from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 33:933-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikaido, H., S. H. Kim, and E. Y. Rosenberg. 1993. Physical organization of lipids in the cell wall of Mycobacterium chelonae. Mol. Microbiol. 8:1025-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ochi, K. 1995. Phylogenetic analysis of mycolic acid-containing wall-chemotype IV actinomycetes and allied taxa by partial sequencing of ribosomal protein AT-L30. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:653-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puech, V., M. Chami, A. Lemassu, M. A. Laneelle, B. Schiffler, P. Gounon, N. Bayan, R. Benz, and M. Daffe. 2001. Structure of the cell envelope of corynebacteria: importance of the non-covalently bound lipids in the formation of the cell wall permeability barrier and fracture plane. Microbiology 147:1365-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rieß, F. G., T. Lichtinger, R. Cseh, A. F. Yassin, K. P. Schaal, and R. Benz. 1998. The cell wall channel of Nocardia farcinica: biochemical identification of the channel-forming protein and biophysical characterization of the channel properties. Mol. Microbiol. 29:139-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sahm, H., L. Eggeling, B. Eikmanns, and R. Krämer. 1996. Construction of l-lysine-, l-threonine-, and l-isoleucine-overproducing strains of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 782:25-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saiki, R. K., C.-A. Chang, C. H. Levenson, T. C. Warren, C. D. Boehm, H. H. Kazazian, Jr., and H. A. Erlich. 1988. Diagnosis of sickle cell anemia and beta-thalassemia with enzymatically amplified DNA and nonradioactive allele-specific oligonucleotide probes. N. Engl. J. Med. 319:537-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1987. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jäger, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schägger, H., and G. von Jagow. 1987. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 166:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Pühler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology 1:784-794. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon, R., B. Hötte, B. Klauke, and B. Kosier. 1991. Isolation and characterization of insertion sequence elements from gram-negative bacteria by using new broad-host-range positive selection vectors. J. Bacteriol. 173:1502-1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stahl, C., S. Kubetzko, I. Kaps, S. Seeber, H. Engelhardt, and M. Niederweis. 2001. MspA provides the main hydrophilic pathway through the cell wall of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 40:451-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steinmetz, M., D. Le Coq, H. Ben Djemia, and P. Gay. 1983. Analyse génétique de sacB, géne de structure d'une enzyme secreétée, la levansucrase de Bacillus subtilis Marburg. Mol. Gen. Genet. 191:138-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trias, J., and R. Benz. 1993. Characterization of the channel formed by the mycobacterial porin in lipid bilayer membranes. Demonstration of voltage gating and of negative point charges at the channel mouth. J. Biol. Chem. 268:6234-6240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trias, J., and R. Benz. 1994. Permeability of the cell wall of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 14:283-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trias, J., V. Jarlier, and R. Benz. 1992. Porins in the cell wall of mycobacteria. Science 258:1479-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Udaka, S. 1960. Screening method for microorganisms accumulating metabolites and its use in the isolation of Micrococcusglutamicus. J. Bacteriol. 79:745-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Rest, M. E., C. Lange, and D. Molenaar. 1999. A heat shock following electroporation induces highly efficient transformation of Corynebacterium glutamicum with xenogeneic plasmid DNA. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 52:541-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Soolingen, D., P. W. Hermans, P. E. de Haas, D. R. Soll, and J. D. van Embden. 1991. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2578-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.West, I. C., and M. G. Page. 1984. When is the outer membrane of Escherichia coli rate-limiting for uptake of galactosides? J. Theor. Biol. 110:11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yano, I., and K. Saito. 1972. Gas chromatographic and mass spectrometric analysis of molecular species of corynomycolic acids from Corynebacterium ulcerans. FEBS Lett. 23:352-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]