Abstract

Although alkaline phosphatases are common in a wide variety of bacteria, there has been no prior evidence for alkaline phosphatases in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Here we report that transposon insertions in the pst operon, encoding homologues of an inorganic phosphate transporter, leads to constitutive expression of a protein with alkaline phosphatase activity. DNA sequence analysis revealed that M. smegmatis does indeed have a phoA gene that shows high homology to other phoA genes. The M. smegmatis phoA gene was shown to be induced by phosphate starvation and thus negatively regulated by the pst operon. Interestingly, the putative M. smegmatis PhoA has a hydrophobic N-terminal domain which resembles a lipoprotein signal sequence. The M. smegmatis PhoA was demonstrated to be an exported protein associated with the cell surface. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of PhoA from [14C]acetate-labeled M. smegmatis cell lysates demonstrated that this phosphatase is a lipoprotein.

Inorganic phosphate (Pi) is the primary source of phosphorus for bacteria. Pi is transported in Escherichia coli by two transporters, Pst (phosphate-specific transporter) and Pit (phosphate intake transporter), across the inner cell membrane (43). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that Pi can be generated in the periplasmic space from various organophosphate and phosphonate sources by dephosphorylating enzymes, such as pH 2.5 acid phosphatase (appA gene product) (18), hexose 6-phosphatase (19), glucose 1-phosphatase (agp gene product) (38), cyclic phosphodiesterase (cdpB gene product) (12), and alkaline phosphatase (phoA gene product) (12, 24). All of these proteins are exported to the periplasm, but the alkaline phosphatase (PhoA) is the most prominent one (32, 47, 54, 57). Whereas E. coli has only one copy of phoA (E. coli phoA), Bacillus subtilis possesses four functional homologues, but only the phoA and phoB genes encode structural homologues of E. coli PhoA (25). E. coli phoA is part of the phosphate regulon, which includes more than 80 genes, and phoA expression is upregulated more than 100-fold upon Pi starvation (56).

E. coli PhoA has been studied extensively and used as a reporter for the identification of secreted proteins (9, 31, 32, 46, 48, 50, 57), because it is an exported enzyme which is activated only after its translocation into the bacterial periplasmic space. PhoA homologues have also been described in other bacteria (2, 3, 20, 30, 34). The PhoA precursor protein in E. coli has a classic amino-terminal signal peptide and is translocated via a Sec-dependent pathway to the periplasmic side of the cytoplasmic membrane. The leader peptide of the precursor protein is then removed by a signal peptidase I (LepB), and the mature PhoA protein is released in the periplasm (8). The protein undergoes two additional modifications involving DsbA (thiol-disulfide interchange protein) (6), DsbB (disulfide bond formation protein B) (22), and Iap (alkaline phosphatase conversion protein) (26), resulting in the formation of two intramolecular disulfide bonds and the removal of the N-terminal arginine from the mature protein. Finally, after dimerization of two processed protein subunits, the enzyme achieves its active state. Thus, the formation of an active PhoA in E. coli is a complex process which depends explicitly on efficient export of PhoA outside the cell, posttranslational processing, and dimerization (1, 36).

Despite the functional and structural similarities observed among the bacterial PhoA enzymes, the mechanisms of phoA induction (25, 40), as well as the mechanisms of the enzyme secretion, seem to differ in different bacterial species (2). The alkaline phosphatase enzymes of mycobacteria have not previously been identified or studied. Although constitutive phosphatase activity has been observed in Mycobacterium bovis BCG (10), this activity was apparently not related to a PhoA homologue because no such homologues can be found in either the Mycobacterium tuberculosis or M. bovis genome database. In Mycobacterium smegmatis, alkaline phosphatase activity has not been detected previously, and it has been presumed that M. smegmatis lacked a functional alkaline phosphatase. In fact, due to the apparent absence of PhoA activity in M. smegmatis, the truncated phoA gene of E. coli (′phoA) has been used as a reporter for protein export in M. smegmatis (53). E. coli ′phoA encodes a truncated protein lacking the signal sequence, and the enzyme is not exported to the periplasm and is enzymatically inactive. If a signal sequence is fused to E. coli ′phoA, the resulting fusion protein will be exported and can be assayed as an enzymatically active fusion in M. smegmatis. Such a strategy has been used successfully to identify exported mycobacterial proteins (7, 11, 13, 27, 29, 53).

In this article we present data for the existence of cryptic phoA in M. smegmatis. Here we show that M. smegmatis phoA is constitutively expressed in strains with mutations in genes of the pst operon and that M. smegmatis phoA expression in M. smegmatis is upregulated upon phosphate starvation. In addition, we present data that M. smegmatis PhoA is a lipoprotein that is exported to the cell surface but remains associated with the cell membrane.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, bacteriophages, transposons, and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli and M. smegmatis strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: kanamycin, 40 μg/ml for E. coli and 20 μg/ml for M. smegmatis; carbenicillin, 50 μg/ml for E. coli; and hygromycin, 150 μg/ml for E. coli and 50 μg/ml for M. smegmatis. LB agar containing 60 μg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) (Sigma, Inc.) per ml was used for screening of E. coli phoA- and M. smegmatis phoA-expressing clones. Plasmid or cosmid DNA was introduced into M. smegmatis mc2155 by electroporation as previously described (49). After expression for 2 h at 37°C, cells were plated on LB agar containing 0.5% glucose, 0.05% Tween 80, 60 μg of BCIP per ml, and either 20 μg of kanamycin per ml or 50 μg of hygromycin per ml.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids, phages, and strains used in this study

| Plasmid, phage, or strain | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pJK212 | lpqH(150)::′phoA ColE aphA L5 attP L5 int | This work |

| pJK207 | lpqH(150)::′phoA ColE aphA | This work |

| pYUB412 | hyg bla L5 attP L5 int ColE1 | 5, 31 |

| Phages | ||

| phAE159 | Deletion mutant of mycobacteriophage TM4 | J.K., unpublished |

| phAE180 | phAE159(Tn5371) | S.H.L., unpublished |

| phAE185 | phAE159(Tn5370) | J.K., unpublished |

| E. coli K-12 | ||

| DH5α | F [φ80dΔlacZM15] Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 glnV44 thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Life Technologies, Inc. |

| TransforMax EC100D pir-116 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZ ΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara, leu)7697 galU galK λ−rpsL nupG pir-116(DHFR) | Epicentre Technologies (30) |

| HB101 | F supE44 ara14 galK2 Δ(gpt-proA)62 lacY1 hsdS20 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 recA13 Δ(mcrC-mrr) | Stratagene |

| M. smegmatis | ||

| mc2155 | ept-1 mutation conferring high efficiency of plasmid transformation | 45 |

| mc21279 | ept-1 [pJK212∗(lpqH::′phoA aph int attP)] | This work |

| mc21280 | mc2 1279::Tn5370 (hyg, aph) inb (intense blue on BCIP) | This work |

| mc21281 | Tn5370 inb (hyg) | This work |

| mc21282 | mc2155 ΔphoA::hyg | This work |

| mc21283 | mc2 1282 containing pMV361(aph)::M. smegmatisphoA | This work |

| mc21240 | pstS-1 mutation conferring constitutive expression of M. smegmatisphoA, PhoA+ phenotype | This work |

| mc21241 | pstS-3 mutation conferring constitutive expression of M. smegmatisphoA, PhoA+ phenotype | This work |

| mc21242 | pstS-3 mutation conferring constitutive expression of M. smegmatisphoA, PhoA+ phenotype | This work |

| mc21243 | pstS-4 mutation conferring constitutive expression of M. smegmatisphoA, PhoA+ phenotype | This work |

| mc21244 | phoU mutation conferring constitutive expression of M. smegmatisphoA, PhoA+ phenotype | This work |

| mc21245 | pstA mutation conferring constitutive expression of M. smegmatisphoA, PhoA+ phenotype | This work |

| mc21246 | pstC mutation conferring constitutive expression of M. smegmatisphoA, PhoA+ phenotype | This work |

Molecular biology procedures.

All molecular biology techniques for cloning were done by standard protocols as described by Sambrook et al. (45). The restriction enzymes and Vent DNA polymerase were obtained from New England BioLabs, Inc. KspI was obtained from Boehringer Mannheim, Inc. 32P for DNA labeling and Southern analysis was purchased from Dupont, New Products, Boston, Mass.

The plasmids and cosmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Plasmid pJK212 is shuttle vector constructed by cloning attP and int from mycobacteriophage L5 (28) into the EcoRV site of pJK207. Plasmid pJK207 was created by EcoRV rescuing lpqH(150 aa)::Tn522′phoA from genomic DNA prepared from M. smegmatis strain mc22746 (11). To generate pJK212, pJK207 was digested with EcoRV, and the int gene and attP site from pYUB412 (4) were cloned in. When integrated into the M. smegmatis chromosome, strain mc21279 (Table 1), pJK212 confers a blue phenotype (PhoA+) on BCIP-containing medium.

Transposon mutagenesis and generalized transduction in M. smegmatis.

In this study, Tn5370(hyg) (17) and Tn5371(hyg) (Sun Hee Lee, unpublished data) were used for transposon mutagenesis of M. smegmatis. Tn5370 is an IS1096-based transposon (33), and Tn5371 is a mariner derivative (44). Both were cloned into a mycobacteriophage TM4-based vector, the temperature-sensitive phage phAE159 (J. Kriakov, unpublished data), resulting in phAE159(Tn5370) and phAE159(Tn5371), respectively. These phages were used as vehicles for transposon delivery and for random mutagenesis of M. smegmatis. The isolation of mutant strains and the identification of the transposon insertion sites were performed as described previously (5, 16).

Mycobacteriophage I3 (42) was used for generalized transduction of M. smegmatis. High-titered phage lysates (1010 PFU/ml) of phage I3 were prepared on the donor strain as a host, and then the phage lysates were used to transfer the marker of interest into the recipient strain. Briefly, recipient strains were grown to optical density at 600 nm of 0.8 to 1.0 in 50 ml of liquid medium. Cells were washed twice with LB, brought to 1/50 of the initial volume, and infected with 1010 PFU of transducing phages per ml at a multiplicity of infection of 1:10. After incubation for 6 h at 37°C, cells were washed once with LB containing 0.1% Tween 80, resuspended in 50 ml of LB, and expressed for 3 h. Finally, the cells were collected and plated on selective medium.

DNA and protein sequence analysis.

DNA sequencing was performed with an Applied Biosystems Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer) and an Applied Biosystems 377 automated DNA sequencer. Tn5370 transposition junctions at the target site in genomic DNA were obtained with the HOP1 and HOP2 (33) primers, directed outward from inside both transposon ends. The primers phoMS-A (5′-ATCCACGTCATCGAGGAGT-3′) and phoMS-B (5′-CCGTCGAGATCGAGTTGTA-3′) were used for PCR amplification to obtain from genomic DNA of M. smegmatis the 2.23-kb DNA fragment containing the M. smegmatis phoA gene, including its flanking regions. The 2.23-kb fragment was cloned and sequenced, and the putative phoA gene sequence has been deposited to GenBank, accession number AY069934.

For DNA and protein analysis, the following servers were used: NCBI Advanced Blast and GenBank sequence data submission (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/ and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/, respectively), the Sanger Centre M. tuberculosis Sequencing Project (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_tuberculosis/), Tuberculist (http://www.pasteur.fr./Bio/Tuberculist/), PSORT (http://psort.nibb.ac.jp:8800/), TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-1.0/), and opPred2 (http://www.biokemi.su.se/≈server/toppred2Server.cgi). Preliminary sequence data for M. smegmatis were obtained from the Institute for Genomic Research website at http://www.tigr.org.

Alkaline phosphatase activity.

The alkaline phosphatase activity of M. smegmatis strains was estimated as described previously (11) with small modifications. Strains were grown at 37°C, and at days 2, 4, 6, and 8, cells were pelleted and resuspended in 0.1 ml of 1 M Tris (pH 8.0); 1.0 ml of PhoA substrate, consisting of 2 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate plus disodium salt (Sigma, Inc.) dissolved in 1 M Tris (pH 8.0), was added to the cell suspension. Alkaline phosphatase units were determined by the following formula: 1,000 × [optical density at 420 nm/(minutes of reaction) (optical density at 600 nm)]. The negative control strain used in these assays was M. smegmatis mc2155 phoA::hyg.

The effect of inorganic phosphate on phoA induction was studied at low (500 μM) and high (10 mM) concentrations of phosphate in the medium as suggested before (15, 30), with some modifications. The strains were grown in 7H9 medium (Difco) to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0, and then the cultures were washed twice with 500 μM phosphate buffer and the cells were resuspended to a final optical density at 600 nm of 0.2 in a home-prepared 7H9 medium containing either 500 μM or 10 mM K2NaH2PO4 buffer, pH 7.0. The cell suspensions were incubated at 37°C, and PhoA activity was measured at different time points.

Lipoprotein analysis and immunoprecipitation.

Cellular lipoproteins of M. smegmatis were labeled with [14C]acetate as described by Fernandez et al. (21); 10 ml of 7H9 broth was inoculated with overnight culture of M. smegmatis to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.2. Next, [14C]acetate was added to a final concentration of 50 μCi/ml, and the cells were incubated for 8 h at 37°C. For removal of the high background of radiolabeled material, phospholipids were extracted as follows. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min and washed twice with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. Cells were sonicated on ice and centrifuged at 1,000 × g to remove cell debris. The supernatant, 0.4 ml, was transferred into a new Eppendorf tube, 0.04 ml of 5 M NaCl was added, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 30 min. The cell membranes were collected by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 1 h.

For solubilization of membrane lipids, the membrane pellet was extracted with 0.5 ml of chloroform-methanol (2:1, vol/vol) by shaking for 30 min at room temperature. Membrane proteins were pelleted at 14,000 × g for 1 h and subjected two more times to chloroform-methanol extraction. Finally, the air-dried pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 50 μl of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample buffer and boiled for 5 min (45). Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and 14C-labeled proteins were detected by autoradiography, followed by Western analysis for detection of M. smegmatis PhoA.

For immunoprecipitation of M. smegmatis PhoA, whole-cell lysates of [14C]acetate-labeled M. smegmatis cells were used. PhoA was precipitated for 2 h at 4°C with anti-PhoA rabbit polyclonal antibody (Research Diagnostics, Inc.). Precipitates were collected by use of protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer's protocol and analyzed by SDS-PAGE, autoradiography, and Western blot.

Protein gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

Cell lysate preparation, SDS-PAGE (10 to 20% gradient gels, Bio-Rad), and protein transfer (Trans Blot SD; Bio-Rad) onto a membrane (Hybond-C extra, catalog no. RPN303E; Amersham Life Science) were performed as described (45).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences of the M. smegmatis phoA gene and of the M. smegmatis pst operon, including their flanking regions, have been deposited to the GenBank database with the accession numbers AY069934 and AY228478, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isolation of M. smegmatis mutant expressing elevated levels of PhoA.

In an effort to study mutations conferring protein export defects in mycobacteria, we constructed a Tn5370 library in a reporter strain of M. smegmatis, mc21279 (Table 1). The reporter strain, mc21279, was designed to constitutively express and export a recombinant fusion of the secreted M. tuberculosis 19-kDa antigen (LpqH) (15, 23) and the truncated E. coli PhoA (′PhoA). The secreted fusion protein was detected by its extracellular alkaline phosphatase activity, assayed by blue color production on plates containing the chromogenic substrate of PhoA, BCIP. Tn5370 insertion mutants that are defective in protein export would be expected to form white to pale blue colonies (decreased export) or colonies with intense blue color (increased export) compared to the parent strain (Fig. 1A). After transposon mutagenesis of mc21279 with Tn5370 (17), 12 mutants with altered PhoA activities were isolated. From approximately 10,000 transposon mutants, 12 white mutants and one intensely blue mutant were isolated. Eleven of the white mutants had insertions into the recombinant lpqH-′phoA fusion and one had an insertion in a gene homologous to cyaA (data not shown). We focused on characterization of mc21280, the intensely blue mutant expressing elevated PhoA enzymatic activity.

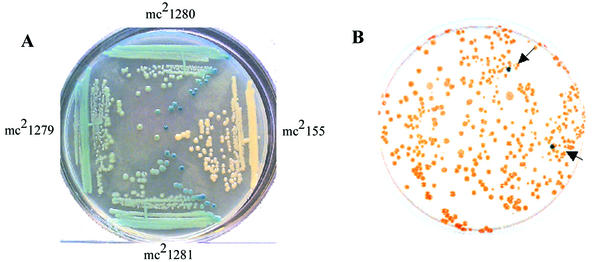

FIG. 1.

Isolation of M. smegmatis mutant expressing elevated alkaline phosphatase activity. The strains were plated on a BCIP-containing LB agar plate. White colonies, PhoA−; blue colonies, PhoA+. Panel A: mc2155, wild-type, PhoA−; mc21279, expresses the fusion LpqH-′PhoA, PhoA+; mc21280, Tn5370 insertion mutant of mc21279, intensely PhoA+; mc21281, transduction donor of the Tn5370 mutation from mc21280, intensely PhoA+. Panel B: identification of M. smegmatis mutants (arrows) constitutively expressing phoA (see text).

Genetic transfer of Tn5370 insertion by generalized transduction transfers the elevated alkaline phosphatase phenotype.

The Tn5370 insertion from the intensely blue mutant was transferred as an independent mutation into M. smegmatis mc2155 by generalized transduction with mycobacteriophage I3 (41). Transductants were selected as hygromycin resistant (Hygr) colonies, as Tn5370 carries the hyg gene. We screened for Hygr, kanamycin susceptible (Kans) and alkaline phosphatase-negative (PhoA−) transductants, where the Kans phenotype marks the loss of the LpqH-PhoA fusion. To our surprise, the Hygr Kans clones, which lacked the ′PhoA fusion, still exhibited the elevated PhoA+ phenotype (Fig. 1), and we designated this strain mc21280. Several independent transductants were analyzed, and all exhibited the same phenotype, Hygr, Kans, and PhoA+. One of these transductants used for further study was designated mc21281. These results indicated that the elevated PhoA phenotype, caused by the Tn5370 insertion, was unrelated to the LpqH-PhoA fusion in mc21280. Both strains, the transductant mc21281 and its parent mc21280, were used in the subsequent analysis.

Immunoblot analysis reveals that an endogenous PhoA reactive protein is produced by mc21280 and mc21281.

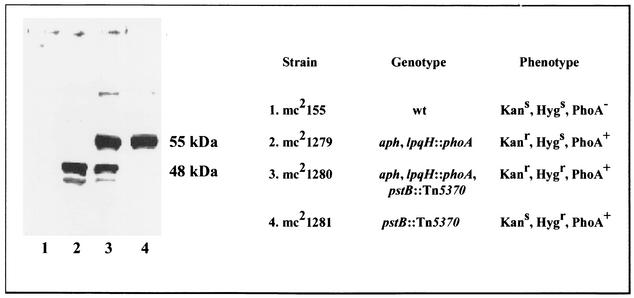

Whole-cell lysates of M. smegmatis mc2155 and the recombinant strains mc21279, mc21280, and mc21281 were separated on SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-E. coli PhoA polyclonal serum. As expected, M. smegmatis was negative for E. coli ′phoA expression (Fig. 2, lane 1). Strain mc21279, which contains the lpqH::′phoA fusion, expressed the fusion product and had an immunoreactive protein band approximately 48 kDa in size (Fig. 2, line 2). In mc21280, the intensely blue mutant which contains the lpqH-′phoA fusion and Tn5370 insertion, a larger 55-kDa band was detected in addition to the 48-kDa band. Strikingly, the lysate from the transductant mc21281 contained only the 55-kDa immunoreactive protein (Fig. 2, line 4). The Western blot analysis indicated that the Tn5370 insertion, which led to elevated alkaline phosphatase activity in M. smegmatis, also led to expression of a protein in mc21281 that was recognized by anti-E. coli PhoA antibodies. These data strongly suggested that M. smegmatis has an alkaline phosphatase which is not expressed under normal growth conditions and that the Tn5370 mutation in mc21280 and mc21281 disrupts a gene that normally acts to negatively regulate phoA and repress its expression in M. smegmatis.

FIG. 2.

Immunodetection of PhoA in M. smegmatis cell lysates. The protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted on a membrane, and PhoA was detected with anti-PhoA polyclonal antibodies. Lane 1, mc2155; lane 2, mc21279; lane 3, mc21280; lane 4, mc21281. wt, wild type.

M. smegmatis has a phoA gene encoding an alkaline phosphatase.

Low-stringency hybridization of E. coli phoA DNA to M. smegmatis genomic DNA (data not shown) and analysis of the DNA sequence of M. smegmatis at the Institute for Genomic Research website at http://www.tigr.org identified a phoA homologue. The protein alignment search (TBlastN) with E. coli K-12 PhoA (NP_414917) revealed that M. smegmatis has a phoA-homologous gene (M. smegmatis phoA) with a putative open reading frame, yielding a predicted product of 511 amino acids (M. smegmatis PhoA) homologous to other bacterial PhoAs. The wild-type M. smegmatis phoA gene was cloned and constitutively expressed from the hsp60 promoter in M. smegmatis (52). The resulting recombinant, mc21283, exhibited a PhoA+ phenotype (Table 2), confirming that the phoA gene encodes a functional alkaline phosphatase in M. smegmatis, and therefore the gene in M. smegmatis was named phoA (GenBank AY069934). The predicted M. smegmatis PhoA had high similarity (72%) to Escherichia fergusonii PhoA.

TABLE 2.

Alkaline phosphatase activity in different M. smegmatis strains

| Strain | Genotypea | Mean PhoA activityb (APU) ± SD

|

Mean induction (± SD) of PhoA & by Pic at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | Supernatantsd | 500 μM | 10 mM | ||

| mc2155 | Wild type | 0 | 0 | 1.41 ± 0.12 | 0.2 ± 0.04 |

| mc21279 | lpqH::EC ′phoA | 2.81 ± 0.1 | 0.13 ± 0.1 | 2.50 ± 0.14 | 2.15 ± 0.1 |

| mc21280 | lpqH::EC ′phoA pstB::Tn5370 | 3.45 ± 0.16 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | NA | NA |

| mc21281 | pstB::Tn5370 | 2.50 ± 0.11 | 0.12 ± 0.1 | No growth | No growth |

| mc21282 | ΔphoA::hyg | 0 | 0 | 0.8 ± 0.11 | 0.3 ± 0.08 |

| mc21283 | ΔphoA(pMV361::phoA) | 2.25 ± 0.14 | 0.12 ± 0.08 | 2.2 ± 0.17 | 2.11 ± 0.2 |

EC, E. coli.

Alkaline phosphatase units (APU) were estimated as described previously (11).

The effect of inorganic phosphate on phoA induction was investigated by growing the strains in minimal medium containing either a low (500 μM) or high (10 mM) concentration of K2NaH2PO4, and cell-associated PhoA activity was determined (see Materials and Methods). NA, not available.

The supernatants were concentrated 100-fold, and then PhoA activity was measured.

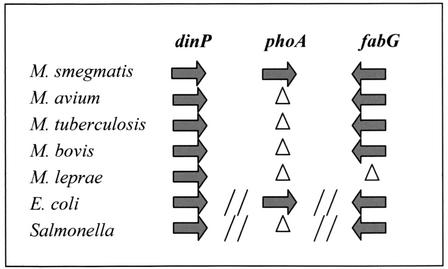

After a search of genome databases, genes similar to M. smegmatis phoA were not found in slow-growing mycobacteria such as M. tuberculosis, M. avium, M. leprae, and M. bovis. By gene comparison of the mycobacterial genomes, we found that the genes flanking phoA in M. smegmatis exist in these organisms and are preserved in the same orientation but lack the phoA gene (Fig. 3). Whether phoA has been lost in these organisms or M. smegmatis has acquired it during evolution waits to be determined by bioinformatic analysis. In addition, Southern analysis with M. smegmatis phoA as a probe and genomic DNAs from variety of mycobacterial species, including M. avium, M. microti, M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, M. vaccae, M. kansasii, M. scrofulaceum, M. xenopi, M. bovis BCG, M. leprae, M. tuberculosis, and M. marinum (data not shown), revealed that only M. vaccae and M. scrofulaceum had putative phoA homologues that cross-hybridized with the M. smegmatis phoA gene.

FIG. 3.

Gene organization of phoA genomic region in different bacterial species. Gene products: dinP, DNA damage-inducible protein; phoA, alkaline phosphatase; fabG, 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein reductase. Arrows show the gene orientation. Δ, gene does not exist; //, discontiguous region. “Salmonella” refers to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium.

Analysis of the M. smegmatis phoA DNA sequence indicated that M. smegmatis PhoA had an amino-terminal hydrophobic domain harboring an atypical lipoprotein signal sequence (39). The predicted molecular mass of the precursor and the mature M. smegmatis PhoA were calculated as 53.7 kDa and 51.1 kDa, respectively (http://us.expasy.org/cgi-bin/pi_tool). The analysis of the M. smegmatis PhoA protein sequence and the experimental data revealed a discrepancy. The predicted molecular mass of the mature product (51 kDa) differed from the molecular size estimated by Western blot experiments (55 kDa). One possible explanation for the difference is that PhoA is subject to additional lipid modification. Another possible explanation is that the predicted M. smegmatis PhoA cleavage site is not recognized and the enzyme remains attached to the cell as a transmembrane protein via its hydrophobic domain.

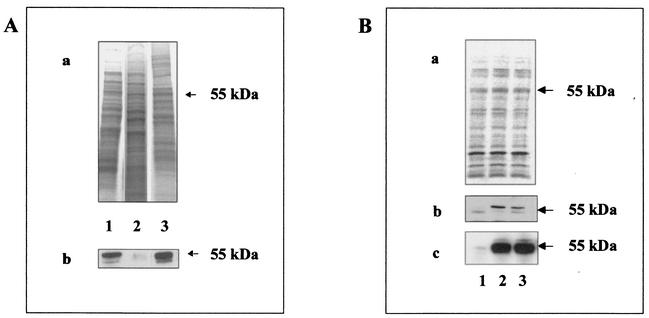

M. smegmatis PhoA is a cell surface-associated lipoprotein.

The data from the protein structure prediction analysis of M. smegmatis PhoA indicated that it may have a different cell topology than other bacterial alkaline phosphatases. In order to investigate this, we performed fractionation studies on whole-cell lysates prepared from M. smegmatis expressing phoA. The fractionation studies and subsequent immunoblot detection of PhoA revealed that M. smegmatis PhoA was recovered in the cell membrane fraction (Fig. 4A, lane 3) but was not found in the cleared cell lysate (Fig. 4A, lane 2), which is in accordance with the prediction analysis indicating the presence of a hydrophobic N-terminal domain. The lipidation motif found in M. smegmatis PhoA indicated that the exported enzyme might also be acylated posttranslationally.

FIG. 4.

Cellular localization of M. smegmatis PhoA. Panel A, fractionation of M. smegmatis PhoA. (a) SDS-PAGE of cell lysate fractions; (b) Western blot detection of PhoA. Lanes: 1, whole-cell lysate; 2, supernatant fraction after centrifugation of the whole-cell lysate; 3, membrane fraction of the whole-cell lysate (see Materials and Methods). Panel B, immunoprecipitation of M. smegmatis PhoA. (a) Autoradiography of [14C]acetate-labeled whole-cell lysate proteins separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted on a membrane; (b) autoradiography of M. smegmatis PhoA recovered by immunoprecipitation with anti-PhoA antibody from [14C]acetate-labeled cell lysates; (c) Western blot detection of the immunoprecipitated fractions. Lanes: 1, M. smegmatis mc2155 (M. smegmatis phoA not induced); 2, M. smegmatis mc2155 (M. smegmatis phoA induced); 3, M. smegmatis mc21281 (M. smegmatis phoA constitutively expressed).

To determine whether M. smegmatis PhoA is indeed a lipoprotein, M. smegmatis cells constitutively expressing phoA were grown in the presence of [14C]acetate, and labeled lipoproteins were subjected to a fractionation analysis (see Materials and Methods) (data not shown). The experiment revealed that many proteins of the membrane fraction were acylated, and more than 30 of them could be separated by PAGE. The most abundant fractions of lipoproteins were found in the size ranges of 40 and 60 kDa. In contrast to E. coli, in which PhoA has been found after induction to account for as much as 6% of the total protein synthesized in the cell (56, 59), we were not able to determine a predominant protein band that would represent the PhoA protein in M. smegmatis.

In order to specifically recover the [14C]acetate-labeled M. smegmatis PhoA, the protein was immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates by use of E. coli anti-PhoA antibody, separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a membrane for subsequent autoradiography and Western analysis. Autoradiography of the immunoprecipitate detected a defined band of 55 kDa (Fig. 4B, section b), indicating that PhoA is acylated. The same membrane was immunoprobed with anti-PhoA antibodies, and when compared to the imuno-precipitation autoradiographs, a defined protein band of 55 kDa was detected by Western blotting (Fig. 4B, section c). The immunoprecipitation of an acylated protein with the anti-PhoA antibody provides direct evidence that the PhoA of M. smegmatis is acylated. This observation is consistent with the sequence analysis revealing a putative lipidation motif. The experimental data and the prediction analysis support the suggestion that M. smegmatis PhoA is a membrane-associated protein.

The observations that M. smegmatis PhoA is acylated and remains linked to the membrane protein fractions (Fig. 4), as well as its functional association with the cellular fraction (Table 2), led us to propose that this alkaline phosphatase is functioning as a membrane-bound lipoprotein in M. smegmatis. Its cell surface association is most likely explained by the presence of a hydrophobic domain and a lipoprotein modification signal peptide at the amino terminus, which may anchor the protein to the cell membrane, in contrast to the secreted E. coli PhoA. Whether additional posttranslational modifications are needed (as for E. coli PhoA) for activation of M. smegmatis PhoA following its export remains to be investigated.

Mutations in the pst operon confer constitutive expression of M. smegmatis phoA.

In order to further characterize the mutation responsible for the induction of M. smegmatis phoA in M. smegmatis mc21280 and mc21281, the Tn5370 insertion sites in these mutants were sequenced. DNA sequencing revealed that Tn5370 was inserted into a gene homologous to E. coli pstB (68% homology to the pstB gene product in E. coli, gi:16131593). The pstB gene in E. coli encodes an ATPase (14, 51) and is a part of Pst, the phosphate-specific transporter located in an operon structure comprising the pstB, pstA, pstC, pstS, and possibly phoU genes (14, 54, 56). Homologues of pst genes in other bacteria are also involved in the transport of Pi (37, 40). In E. coli, mutations in the pst genes negatively regulate the expression of phoA (14, 35). Our finding that disruption of the pstB gene induces phoA expression in M. smegmatis suggests that a similar Pi transporter very likely exists in M. smegmatis, because this mutation also negatively regulates the expression of phoA. To test this hypothesis, we sought to find other mutations that also conferred constitutive expression of the phoA gene in M. smegmatis.

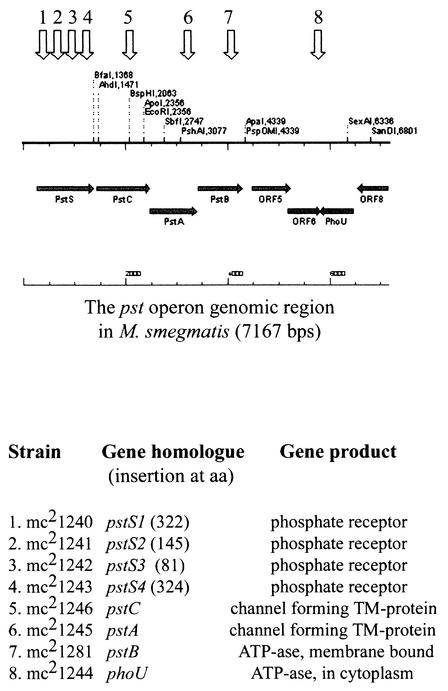

In a separate transposon mutagenesis experiment, we mutagenized wild-type M. smegmatis with Tn5371 and isolated more M. smegmatis mutants constitutively expressing phoA (Fig. 1B). All of the transposon insertion sites were sequenced and found to map in contiguous genomic regions, including pstS, pstA, pstC, and phoU gene homologues, all part of the pst operon (Fig. 5) (GenBank accession number AY228478). This experiment unambiguously confirms that a functional phoA gene exists in M. smegmatis and clearly demonstrates that its expression is tightly regulated by the pst operon.

FIG. 5.

Organization of pst operon in M. smegmatis (GenBank accession number AY228478). The transposon insertion sites were sequenced, and the corresponding open reading frame were designated according to observed homology to other bacterial pst genes in the database (see Materials and Methods). Arrows show the mutation sites in the corresponding genes, and the mutant strains are listed below. TM, transmembrane.

In E. coli, the pst operon has been studied extensively, and its function has been found to be not only related to the uptake of inorganic phosphates but also linked to the intracellular regulation of phosphate accumulation (35, 54, 55). As in other bacteria, we found that M. smegmatis phoA is induced in M. smegmatis upon phosphate starvation (Table 2). M. smegmatis phoA was found to be expressed at low concentrations of Pi, but the levels of the enzyme activity did not reach those of PhoA constitutively expressed by the pst mutants. Surprisingly, the pst mutants which were isolated and grew successfully on complex medium were not able to grow on 10 mM phosphate (Table 2). M. smegmatis growth curve studies confirmed these results (data not shown), demonstrating that the genes from the pst operon in M. smegmatis may be conditionally essential, which is contrary to the situation in E. coli.

These results suggest that the constitutive expression of phoA in M. smegmatis, observed as the result of mutations in the pst operon, may have a different mechanism of induction than phosphate starvation. Under similar conditions for Pi uptake, E. coli uses the Pit system, which operates constitutively and delivers the necessary phosphate for cell growth even at phosphate concentrations as low as 20 μM (58). Therefore, the Pit system may not exist in M. smegmatis, or if it exists, it is not efficient under the conditions used for phoA induction. Low levels of phosphatase activity were observed in the phoA mutant strain (Table 2), which could be explained by the presence of other phosphatases.

More comprehensive studies of phosphate uptake in M. smegmatis are needed for a better understanding of how this system functions in mycobacteria. Recent studies have suggested a lack of inducible phosphatase activity in M. bovis BCG upon phosphate starvation (10), which is in agreement with the fact that no identifiable structural homologues of M. smegmatis phoA can be found in the M. bovis BCG or M. tuberculosis genome database. Whether more complex regulation of phosphate uptake exists in M. smegmatis requires further investigation with different mycobacterial species.

Conclusions.

While studying the secretion machinery of mycobacteria, we discovered the existence of a previously unknown phoA gene in M. smegmatis. In similarity to its phoA gene homologue in E. coli, which is negatively regulated by the pst operon, M. smegmatis phoA expression was found to be upregulated as a result of mutations in the pst operon genes pstA, pstB, pstC, pstS, and phoU. Unlike E. coli PhoA, the putative M. smegmatis phoA gene product contained a lipoprotein signal sequence, suggesting that it could be a lipoprotein. Membrane localization studies revealed that the M. smegmatis PhoA protein and its enzyme activity were associated with the cell wall. Moreover, immunoprecipitation analysis of acetate-labeled M. smegmatis confirmed that M. smegmatis PhoA is a lipoprotein. Further studies are in progress to investigate the precise posttranslational modifications required for M. smegmatis PhoA activity. The discovery of a mycobacterial PhoA may help delineate specific aspects of phosphate metabolism in mycobacteria. Furthermore, this gene is likely to contribute to our understanding of the processes by which lipoproteins are exported from mycobacterial cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle Larsen, Paul Morin, Suzanne Hingley-Wilson and Apoorva Bhatt for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. We are also thankful to Miriam Braunstein for intellectual inspiration and discussions concerning the manuscript and the development of tools for the study of mycobacterial secretion pathways.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI26170.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyama, Y., and K. Ito. 1993. Folding and assembly of bacterial alkaline phosphatase in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 268:8146-8150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelini, S., R. Moreno, K. Gouffi, C. Santini, A. Yamagishi, J. Berenguer, and L. Wu. 2001. Export of Thermus thermophilus alkaline phosphatase via the twin-arginine translocation pathway in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 506:103-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Au, S., K. L. Roy, and R. G. von Tigerstrom. 1991. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of the gene for secreted alkaline phosphatase from Lysobacter enzymogenes. J. Bacteriol. 173:4551-4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bange, F. C., F. M. Collins, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1999. Survival of mice infected with Mycobacterium smegmatis containing large DNA fragments from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberc. Lung Dis 79:171-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardarov, S., J. Kriakov, C. Carriere, S. Yu, C. Vaamonde, R. A. McAdam, B. R. Bloom, G. F. Hatfull, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1997. Conditionally replicating mycobacteriophages: a system for transposon delivery to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:10961-10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardwell, J. C., K. McGovern, and J. Beckwith. 1991. Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell 67:581-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berthet, F. X., J. Rauzier, E. M. Lim, W. Philipp, B. Gicquel, and D. Portnoi. 1995. Characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis erp gene encoding a potential cell surface protein with repetitive structures. Microbiology 141:2123-2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black, M. T. 1993. Evidence that the catalytic activity of prokaryote leader peptidase depends upon the operation of a serine-lysine catalytic dyad. J. Bacteriol. 175:4957-4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd, D., C. Manoil, and J. Beckwith. 1987. Determinants of membrane protein topology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:8525-8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braibant, M., and J. Content. 2001. The cell surface associated phosphatase activity of Mycobacterium bovis BCG is not regulated by environmental inorganic phosphate. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 195:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braunstein, M., T. I. Griffin, J. I. Kriakov, S. T. Friedman, N. D. Grindley, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 2000. Identification of genes encoding exported Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins with a Tn552′phoA in vitro transposition system. J. Bacteriol. 182:2732-2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brockman, R. W., and L. A. Heppel. 1968. On the localization of alkaline phosphatase and cyclic phosphodiesterase in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 7:2554-2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll, J. D., R. C. Wallace, J. Keane, H. G. Remold, and R. D. Arbeit. 2000. Identification of Mycobacterium avium DNA sequences that encode exported proteins by with phoA gene fusions. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 80:117-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan, F. Y., and A. Torriani. 1996. PstB protein of the phosphate-specific transport system of Escherichia coli is an ATPase. J. Bacteriol. 178:3974-3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins, M. E., A. Patki, S. Wall, A. Nolan, J. Goodger, M. J. Woodward, and J. W. Dale. 1990. Cloning and characterization of the gene for the ‘19-kDa’ antigen of Mycobacterium bovis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:1429-1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Connell, N. D. 1994. Mycobacterium: isolation, maintenance, transformation, and mutant selection. Methods Cell Biol. 45:107-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox, J. S., B. Chen, M. McNeil, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1999. Complex lipid determines tissue-specific replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Nature 402:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dassa, J., C. Marck, and P. L. Boquet. 1990. The complete nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli gene appA reveals significant homology between pH 2.5 acid phosphatase and glucose 1-phosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 172:5497-5500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dvorak, H. F., R. W. Brockman, and L. A. Heppel. 1967. Purification and properties of two acid phosphatase fractions isolated from osmotic shock fluid of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 6:1743-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eymann, C., H. Mach, C. R. Harwood, and M. Hecker. 1996. Phosphate starvation-inducible proteins in Bacillus subtilis: a two-dimensional gel electrophoresis study. Microbiology 142:3163-3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez, D., T. A. Dang, G. M. Spudich, X. R. Zhou, B. R. Berger, and P. J. Christie. 1996. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virB7 gene product, a proposed component of the T-complex transport apparatus, is a membrane-associated lipoprotein exposed at the periplasmic surface. J. Bacteriol. 178:3156-3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guilhot, C., G. Jander, N. L. Martin, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Evidence that the pathway of disulfide bond formation in Escherichia coli involves interactions between the cysteines of DsbB and DsbA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:9895-9899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrmann, J. L., P. O'Gaora, A. Gallagher, J. E. Thole, and D. B. Young. 1996. Bacterial glycoproteins: a link between glycosylation and proteolytic cleavage of a 19-kDa antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. EMBO J. 15:3547-3554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horiuchi, T., S. Horiuchi, and D. Mizuno. 1959. A possible negative feedback phenomenon controlling formation of alkaline phosphomonoesterase in Esherichia coli. Nature 183:1529-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hulett, F. M., J. Lee, L. Shi, G. Sun, R. Chesnut, E. Sharkova, M. F. Duggan, and N. Kapp. 1994. Sequential action of two-component genetic switches regulates the PHO regulon in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 176:1348-1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishino, Y., H. Shinagawa, K. Makino, M. Amemura, and A. Nakata. 1987. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J. Bacteriol. 169:5429-5433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kremer, L., A. Baulard, J. Estaquier, J. Content, A. Capron, and C. Locht. 1995. Analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 85A antigen promoter region. J. Bacteriol. 177:642-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, M. H., L. Pascopella, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., and G. F. Hatfull. 1991. Site-specific integration of mycobacteriophage L5: integration-proficient vectors for Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and bacille Calmette-Guerin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:3111-3115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim, E. M., J. Rauzier, J. Timm, G. Torrea, A. Murray, B. Gicquel, and D. Portnoi. 1995. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA sequences encoding exported proteins with phoA gene fusions. J. Bacteriol. 177:59-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, W., Y. Qi, and F. M. Hulett. 1998. Sites internal to the coding regions of phoA and pstS bind PhoP and are required for full promoter activity. Mol. Microbiol. 28:119-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manoil, C., and J. Beckwith. 1986. A genetic approach to analyzing membrane protein topology. Science 233:1403-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manoil, C., J. J. Mekalanos, and J. Beckwith. 1990. Alkaline phosphatase fusions: sensors of subcellular location. J. Bacteriol. 172:515-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAdam, R. A., T. R. Weisbrod, J. Martin, J. D. Scuderi, A. M. Brown, J. D. Cirillo, B. R. Bloom, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1995. In vivo growth characteristics of leucine and methionine auxotrophic mutants of Mycobacterium bovis BCG generated by transposon mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 63:1004-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moura, R. S., J. F. Martin, A. Martin, and P. Liras. 2001. Substrate analysis and molecular cloning of the extracellular alkaline phosphatase of Streptomyces griseus. Microbiology 147:1525-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muda, M., N. N. Rao, and A. Torriani. 1992. Role of PhoU in phosphate transport and alkaline phosphatase regulation. J. Bacteriol. 174:8057-8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakata, A., M. Yamaguchi, K. Izutani, and M. Amemura. 1978. Escherichia coli mutants deficient in the production of alkaline phosphatase isozymes. J. Bacteriol. 134:287-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikata, T., Y. Sakai, K. Shibat, J. Kato, A. Kuroda, and H. Ohtake. 1996. Molecular analysis of the phosphate-specific transport (pst) operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Gen. Genet. 250:692-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pradel, E., C. Marck, and P. L. Boquet. 1990. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the Escherichia coli agp gene encoding periplasmic acid glucose-1-phosphatase. J. Bacteriol. 172:802-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pugsley, A. P. 1993. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:50-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qi, Y., Y. Kobayashi, and F. M. Hulett. 1997. The pst operon of Bacillus subtilis has a phosphate-regulated promoter and is involved in phosphate transport but not in regulation of the pho regulon. J. Bacteriol. 179:2534-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raj, C. V., and T. Ramakrishnan. 1970. Transduction in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Nature 228:280-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramakrishnan, T., and M. S. Shaila. 1979. Interfamilial transfer of amber suppressor gene for the isolation of amber mutants of mycobacteriophage I3. Arch. Microbiol. 120:301-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao, N. N., and A. Torriani. 1990. Molecular aspects of phosphate transport in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1083-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubin, E. J., B. J. Akerley, V. N. Novik, D. J. Lampe, R. N. Husson, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1999. In vivo transposition of mariner-based elements in enteric bacteria and mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:1645-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook, J. E., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 46.Sarthy, A., S. Michaelis, and J. Beckwith. 1981. Deletion map of the Escherichia coli structural gene for alkaline phosphatase, phoA. J. Bacteriol. 145:288-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlesinger, M. J., J. A. Reynolds, and S. Schlesinger. 1969. Formation and localization of the alkaline phosphatase of Escherichia coli. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. USA 166:368-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silhavy, T. J., H. A. Shuman, J. Beckwith, and M. Schwartz. 1977. Use of gene fusions to study outer membrane protein localization in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5411-5415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snapper, S. B., R. E. Melton, S. Mustafa, T. Kieser, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1990. Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 4:1911-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snyder, W. B., and T. J. Silhavy. 1995. Beta-galactosidase is inactivated by intermolecular disulfide bonds and is toxic when secreted to the periplasm of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:953-963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steed, P. M., and B. L. Wanner. 1993. Use of the rep technique for allele replacement to construct mutants with deletions of the pstSCAB-phoU operon: evidence of a new role for the PhoU protein in the phosphate regulon. J. Bacteriol. 175:6797-6809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stover, C. K., V. F. de la Cruz, T. R. Fuerst, J. E. Burlein, L. A. Benson, L. T. Bennett, G. P. Bansal, J. F. Young, M. H. Lee, G. F. Hatfull, et al. 1991. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Nature 351:456-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timm, J., M. G. Perilli, C. Duez, J. Trias, G. Orefici, L. Fattorini, G. Amicosante, A. Oratore, B. Joris, J. M. Frere, et al. 1994. Transcription and expression analysis, with lacZ and phoA gene fusions, of Mycobacterium fortuitum beta-lactamase genes cloned from a natural isolate and a high-level beta-lactamase producer. Mol. Microbiol. 12:491-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torriani, A. 1990. From cell membrane to nucleotides: the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli. Bioessays 12:371-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wanner, B. L. 1993. Gene regulation by phosphate in enteric bacteria. J. Cell Biochem. 51:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wanner, B. L. 1996. Phosphorus assimilation and control of the phosphate regulon, p. 1357-1381. In F. C. Neidhardt, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 57.Wanner, B. L., M. R. Wilmes, and D. C. Young. 1988. Control of bacterial alkaline phosphatase synthesis and variation in an Escherichia coli K-12 phoR mutant by adenyl cyclase, the cyclic AMP receptor protein, and the phoM operon. J. Bacteriol. 170:1092-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willsky, G. R., and M. H. Malamy. 1980. Characterization of two genetically separable inorganic phosphate transport systems in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 144:356-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willsky, G. R., and M. H. Malamy. 1976. Control of the synthesis of alkaline phosphatase and the phosphate-binding protein in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 127:595-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]