Abstract

The TtgGHI efflux pump of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E plays a key role in the innate and induced tolerance of this strain to aromatic hydrocarbons and antibiotics. The ttgGHI operon is expressed constitutively from two overlapping promoters in the absence of solvents and at a higher level in their presence, but not in response to antibiotics. Adjacent to the ttgGHI operon is the divergently transcribed ttgVW operon. In TtgV-deficient backgrounds, although not in a TtgW-deficient background, expression of the ttgGHI and ttgVW operons increased fourfold. This suggests that TtgV represses expression from the ttgG promoters and controls its own. TtgW plays no major role in the regulation of expression of these promoters. Primer extension revealed that the divergent ttgG and ttgV promoters overlap, and mobility shift assays indicated that TtgV binds to this region with high affinity. DNaseI footprint assays revealed that TtgV protected four DNA helical turns that include the −10 and −35 boxes of the ttgV and ttgG promoters.

In their natural habitats, living organisms are exposed to a wide range of natural and human-made toxic compounds, and survival in sites that have become hostile involves an extensive series of protective mechanisms. Multidrug efflux pumps are one of the most efficient tools that eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells use to extrude toxic chemicals and are very efficient in the removal of anticancer agents, antibiotics, dyes, superoxide-generating chemicals, organic solvents, and other toxic chemicals (31, 33, 34, 39). Efflux pumps of the resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family are very efficient in the removal of different drugs (33, 37, 45). These bacterial efflux pumps are made of three components (20, 28, 54): an efflux pump transporter located in the cytoplasmic membrane that recognizes substrates in the periplasm or in the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane (11, 28, 50), an outer membrane protein which forms a trimeric channel that penetrates into the periplasm (20) and contacts the efflux pump transporter, and a lipoprotein anchored to the inner membrane which expands into the periplasmic space and may serve as a bracket for the other two components (54).

Toluene, xylene, and styrene are among the most toxic chemicals that bacterial cells can be exposed to because they dissolve in the cytoplasmic membrane, disorganize it, and collapse the cell's membrane potential. This, together with the loss of lipids and proteins, leads to irreversible damage, resulting in the death of the cell (8, 47). However, a number of Pseudomonas putida strains are able to grow in the presence of high concentrations of toluene and other aromatic hydrocarbons (7, 14, 18, 41, 52). Tolerance to these chemicals in these strains is achieved mainly by a series of RND efflux pumps, called Ttg (toluene tolerance genes) in P. putida DOT-T1E (15-18, 21, 27, 29, 42, 43). In P. putida DOT-T1E, three different efflux pumps, TtgABC, TtgDEF, and TtgGHI, function additively to prevent the accumulation of toluene and other aromatic hydrocarbons in the cell membrane (43). Two of these efflux pumps, TtgABC and TtgGHI, also extrude antibiotics such as chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ampicillin (40, 43), and, in the case of TtgABC, probably also heavy metals (P. Godoy and J. L. Ramos, unpublished data).

Some of these efflux pumps have a relatively high basal level of expression and confer so-called intrinsic resistance, whereas others are inducible by the transported product and confer induced resistance. In P. putida DOT-T1E, the ttgABC operon is expressed at a certain basal level, which increases slightly in response to solvents and significantly in response to chloramphenicol (9; W Terán, A. Felipe, A. Segura, A. Rojas, J. L. Ramos, and M. T. Gallegos, submitted for publication), whereas the ttgDEF operon is induced by aromatic hydrocarbons such as toluene or styrene (27). The ttgGHI operon seems to be expressed from two overlapping promoters at a certain basal level in the absence of solvents, and its expression increases severalfold in the presence of aromatic hydrocarbons (43). The RND efflux genes are often regulated by the gene product of an adjacent and divergently transcribed regulatory gene (1, 5, 9, 22, 24, 29, 30, 31, 33, 43, 45). In fact, the ttgR gene is adjacent to the ttgABC operon and is transcribed divergently from ttgA. In a TtgR-deficient background, expression from the ttgA promoter increased about 10-fold, suggesting that TtgR represses expression from the ttgA promoter (9). In this mutant background, expression from the ttgD and ttgG promoters followed the same pattern of expression as in the wild type, suggesting that other regulators are involved in the control of expression of the other two efflux pumps.

In this study, we report the identification of two genes, ttgV and ttgW, that form an operon and that are transcribed divergently from the ttgGHI operon. In the ttgV-deficient background, but not in the ttgW-deficient background, the ttgGHI and ttgVW operons are expressed at a higher level. This suggests that TtgV is a repressor of the expression from the ttgG and ttgV promoters. We overexpressed and purified TtgV and showed that this repressor binds to the ttgV-ttgG intergenic region protecting a region covering four DNA helical turns where the overlapping ttgV and ttgG promoters lie.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture medium.

The bacterial strains, cloning vectors, and plasmids constructed in this study are shown in Table 1. Bacterial strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (4). Escherichia coli cultures were incubated at 37°C, whereas P. putida cultures were incubated at 30°C. Liquid cultures were shaken on an orbital platform operating at 200 strokes per min. When P. putida cultures were supplemented with toluene via the gas phase, we used culture flasks with a central vessel in which 0.15 ml of toluene was introduced to avoid direct contact with the liquid medium. The flasks were tightly closed with a Teflon screw cap. Under these culture conditions, the concentration of toluene in the liquid medium was about 2 mM.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. putida DOT-T1E | Rifr | 41 |

| P. putida DOT-T1E-PS52 | Rifr KmrttgW::ΩKm | This study |

| P. putida DOT-T1E-PS61 | Rifr KmrttgV::ΩKm | This study |

| P. putida DOT-T1E-PS62 | Rifr KmrttgV::aphA3 | This study |

| E. coli DH5αF′ | F′/endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) glnV44 thi1 recA1 gyrA (Nalr) relA1 Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 deoR [φ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15] | 4 |

| E. coli B834 (DE3) | F−omp (rB− mB−) gal dcm met auxotroph | Promega |

| pANA82 | pUC18Not plasmid bearing a 4.5-kb BamHI-EcoRV insert with the ttgVW genes | This study |

| pANA83 | ttgW::ΩKm, derived from pANA82 | This study |

| pANA95 | Promoter of ttgV cloned in pMP220 | This study |

| pANA96 | Promoters of ttgG cloned in pMP220 | This study |

| pANA117 | 2.3-kb fragment cloned in pGEM-T, bearing ttgV and ttgW genes | This study |

| pANA118 | ttgV::aphA3, derived from pANA117 | This study |

| pANA119 | ttgV::ΩKm, derived from pANA117 | This study |

| pANA125 | 0.8-kb NdeI-BamHI fragment bearing ttgV in pGEM-T | This study |

| pANA126 | ttgV-His6 tag cloned in pET28b(+) | This study |

| pET-28b(+) | Kmr, expression vector | Novagen |

| pGEM-T | Apr, cloning vector | Promega |

| pGG1 | pUC18 bearing an 8-kb BamHI fragment with ttgGHI and ttgVW | 43 |

| pHP45Ω-Km | Apr, carries the 2.25-kb ΩKm fragment | 37 |

| pMP220 | Tcr, promoterless lacZ vector | 48 |

| pSBaphA | pSB plasmid with a nonpolar Kmr cassette | 25 |

| pUC18Not | Apr, cloning vector | 32 |

Apr, Kmr, Nalr, Rifr, and Tcr, resistance to ampicillin, kanamycin, nalidixic acid, rifampin, and tetracycline, respectively.

E. coli DH5αF′ (4) was used as a recipient for recombinant plasmids, and E. coli B834(DE3) was chosen as a host for the production of His6-tagged TtgV protein. When required, cultures were supplied with the following antibiotics (at the indicated concentrations unless otherwise stated): ampicillin (100 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (100 μg/ml), piperacillin (100 μg/ml), rifampin (20 μg/ml), streptomycin (300 μg/ml), and tetracycline (20 μg/ml).

DNA techniques.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA, digestion with restriction enzymes, electrophoresis, and Southern blotting were done using standard methods (4). For hybridizations, we used a digoxigenin DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche Laboratories) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. A Qiagen kit was used for plasmid isolation. Plasmid DNA was sequenced on both strands with universal, reverse, or specifically designed primers by using an automatic DNA sequencer (ABI-PRISM 3100; Applied Biosystems). Electroporation of P. putida cells was done as described previously (43).

Preparation of RNA, primer extension analysis, and RT-PCR.

P. putida DOT-T1E was grown overnight in LB medium. Cells were then diluted 100-fold in fresh medium, and aliquots were incubated in the absence or presence of 3 mM toluene, 1.5 mM styrene, or sublethal concentrations of antibiotics (chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml; nalidixic acid, 30 μg/ml; tetracycline, 1 μg/ml; gentamicin, 0.25 μg/ml; and carbenicillin, 120 μg/ml) until the culture reached a turbidity of about 1.0 at 660 nm. Cells (30 ml for primer extension and 1.5 ml for reverse transcriptase [RT] PCR) were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g for 10 min) and processed for RNA isolation according to the method of Marqués et al. (23). Extracts were treated with RNase-free DNase I (50 U) in the presence of 3 U of an RNase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Laboratory). For primer extension analysis, we used as primers specific oligonucleotides complementary either to the ttgV mRNA or the ttgG mRNA. Primers were labeled at their 5′ ends with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase as described previously (4). About 105 cpm of the labeled primer was hybridized to 20 μg of total RNA, and extension was carried out using avian myeloblastosis virus RT as described previously (23). Electrophoresis of cDNA products was done in a urea-polyacrylamide sequencing gel to separate the reaction products. The relative intensity of the bands was quantitated using the Molecular Imager System GS 525 (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with the Multianalyst program.

RT-PCR was done with 1 μg of RNA in a final volume of 20 μl using the Titan OneTube RT-PCR system according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Laboratories). The annealing temperature used for RT-PCR was 60°C, and the cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min. Positive and negative controls were included in all assays. The primers used to test contiguity in the mRNA of the ttgV and ttgW genes are available from the authors upon request.

Construction of ttgV and ttgW knockout mutant strains.

To facilitate site-directed mutagenesis, the 4.5-kb BamHI-EcoRV fragment from pGG1 (43) harboring the ttgV and ttgW genes was ligated to pUC18Not digested with BamHI-SmaI to produce pANA82. Plasmid pANA82 was in turn digested with BglII (which cuts once in the plasmid within the ttgW gene), made blunt with the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates and Klenow enzyme, and then ligated to a 2.25-kb BamHI fragment (blunted as above) from pHP45Ω-Km (37) that contained the kanamycin resistance cassette to yield pANA83 (Apr Kmr). About 600 ng of the suicide pANA83 plasmid was electroporated into P. putida DOT-T1E cells, and transformants that integrated the pANA83 plasmid into the host chromosome via homologous recombination were selected on LB solid medium with kanamycin and piperacillin. Successful integration was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). A random merodiploid clone was grown overnight in LB medium to allow for a second recombination event in which the wild-type gene was replaced by the mutant allele. For this selection, colonies were plated again on LB medium with kanamycin. Among these colonies, those that did not grow in the presence of piperacillin were selected as putative resolved clones. The mutant clones were checked again by Southern blotting, and one of the clones, which exhibited the correct replacement (data not shown), was kept for further studies and named P. putida strain DOT-T1E-PS52.

To construct a ttgV polar mutant, we first amplified by PCR the ttgV gene by using appropriate primers and pGG1 as a source of the gene. The amplified DNA was ligated to pGEM-T to yield pANA117. This plasmid was digested with XcmI (which cuts once in the plasmid within the ttgV gene), and the sticky ends were made blunt. The plasmid was then ligated to an EcoRI 2.25-kb blunt-end Ω-Km fragment from pHP45Ω-Km to yield plasmid pANA119. Plasmid pANA119 was subsequently electroporated into P. putida DOT-T1E cells. Transformants and resolved clones were selected as described above to generate P. putida DOT-T1E-PS52. The ttgV polar mutant was called P. putida strain DOT-T1E-PS61.

A nonpolar mutation in ttgV was constructed using the strategy described above, except that we inactivated the ttgV gene with the nonpolar aphA3 gene cassette (25) to produce pANA118. The mutation was then transferred into the host chromosome to produce P. putida strain DOT-T1E-PS62.

MIC assays.

Concentration assays were done in LB medium using the microtiter broth dilution method (3). Microtiter plates were inoculated with 105 CFU/ml and incubated for 20 h at 30°C.

Survival in response to toluene shocks.

Cells were grown overnight in 30 ml of LB medium with or without toluene in the gas phase. On the following day, cultures were diluted 1:100 and grown under the same conditions until the cultures reached a turbidity of about 0.8 at 660 nm. These cultures contained about 108 CFU/ml. The cultures were divided in two halves; to one we added 0.3% (vol/vol) toluene, and the other was kept as a control. The number of viable cells was determined before toluene was added and 10, 30, and 60 min later.

β-Galactosidase assays.

We constructed fusions of the promoters of the ttgGHI and ttgVW operons to a promoterless lacZ gene in the low-copy-number pMP220 vector (48). The ttgV-ttgG intergenic region (196 bp) was amplified by PCR with primers incorporating restriction sites (an EcoRI site in the primer designed to meet the 5′ end and a PstI site in the primer designed to meet the 3′ end) to create a fusion of the promoters of the ttgGHI operon to ′lacZ. The same oligonucleotides, except with a PstI site in the one meeting the 5′ end and an EcoRI site in the one meeting the 3′ end, were used to create a fusion of the ttgVW operon promoter to ′lacZ. Upon amplification, DNA was digested with EcoRI and PstI and ligated to EcoRI-PstI-digested pMP220 to produce pANA95 (PttgV::lacZ) and pANA96 (PttgG::lacZ). Plasmids pANA95 and pANA96 were sequenced to make sure that no mutations were introduced in the corresponding promoter regions. These plasmids were electroporated into the wild-type P. putida DOT-T1E strain and the mutant strains DOT-T1E-PS52, DOT-T1E-PS61, and DOT-T1E-PS62. The corresponding transformants were grown overnight on LB medium with tetracycline, and then the cultures were diluted 100-fold in the same medium. After 1.5 h of incubation at 30°C with shaking, the cultures were supplemented or not with 3 mM toluene, and 4 h later β-galactosidase activity was assayed in permeabilized whole cells according to Miller's method (26). We also tested the response to other solvents by adding 3 mM benzene, p-xylene, ethylbenzene, or propylbenzene and 1.5 mM styrene. Assays were run in duplicate and were repeated for at least three independent experimental rounds.

Overexpression and purification of His-tagged TtgV.

The ttgV gene was amplified by PCR from plasmid pGG1 (43) with primers incorporating NdeI and BamHI restriction sites at their 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, and cloned in pGEM-T to yield pANA125. The 0.8-kb NdeI-BamHI fragment was subsequently subcloned in pET28b(+) to produce pANA126 so that the gene product, when expressed, would carry an N-terminal histidine tag. For His6-tagged N-TtgV purification, pANA126 was transformed in E. coli B834(DE3). Cells were grown in 1-liter batches at 30°C in LB medium (4) with 50 μg of kanamycin/ml to an A660 between 0.5 and 0.7 and induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Cells were harvested after 3 h of induction at 20°C; resuspended in 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 0.5 M NaCl, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete; Roche); and broken in a French press after treatment with 20 μg of lysozyme/ml. Following centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min, the protein was found predominantly (more than 80%) in the soluble fraction. His6-tagged TtgV was purified by nickel affinity chromatography using a Ni+-Sepharose matrix (Amersham-Biosciences) as described by the supplier, and the bound protein was eluted with an imidazole gradient in the abovementioned buffer. Homogenous peak fractions were pooled and dialyzed against TGED (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol), to which 50% (vol/vol) glycerol and 50 mM NaCl were added, and stored at −70°C (long-term storage) or −20°C (short-term storage). Protein concentrations were determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit.

Electrophoresis mobility shift assay.

A 210-bp DNA fragment containing the divergent ttgG and ttgV promoters was amplified by PCR from plasmid pGG1 and isolated from agarose gels. This fragment was end-labeled with 32P as described above. Labeled DNA (about 1 nM; 1.5 × 104 cpm) was incubated with increasing amounts of TtgV-His6 for 10 min at 30°C in 10 μl of TGED binding buffer containing 20 μg of poly(dI-dC)/ml and 200 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml. Reaction mixtures were then electrophoresed in a nondenaturing 4.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel in Tris-glycine buffer (0.2 M glycine-0.025 M Trizma base [pH 8.6]). Results were analyzed using a Molecular Imager GS525. Competition experiments were performed using increasing amounts of unlabeled probe, with unlabeled-to-labeled DNA ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1,000:1.

DNase I footprinting.

For these assays, a 228-bp PCR fragment generated with the primers indicated below was used. For the footprint on the top strand of the ttgGHI operon, we amplified DNA using primers 5′-GTTCATATGTTTCCTCTGCG-3′ (end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP as described above) and 5′-GTTTGGCTCCATCTCTCTGC-3′. For the footprint on the bottom strand, the same primers were used but the latter primer rather than the former primer was end labeled. About 10 nM concentrations (∼104 cpm) of each labeled probe was incubated in 10-μl reaction mixtures with or without His6-tagged TtgV (1 and 3 μM) in TGED supplemented with poly(dI-dC) (20 μg/ml) and bovine serum albumin (200 μg/ml). Reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at 30°C before being treated with 40 μl of DNase I (final concentration, 10−5 U/μl) diluted in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) supplemented with 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 100 mM KCl. After 4 min at 30°C, reactions were stopped with 2 μl of 0.5 mM EDTA, the sample was extracted with phenol, and then DNA was precipitated with 2 volumes of ethanol and resuspended in 6 μl of TE (10 mM Tris-0.1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) and 3 μl of loading dye. Equal amounts of DNA (5,000 to 6,000 cpm) were heated at 90°C for 3 min and electrophoresed through a 6.5% (wt/vol) denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Sequencing ladders were generated in each case with the corresponding labeled primer using a T7 DNA polymerase sequencing kit (USB-Amersham) and the pGG1 plasmid.

Computer analysis.

Open reading frames (ORFs) in DNA sequences were predicted with various programs included in the DNA Strider 1.1 package. Sequences were compared with those in the BlastX programs (2), available from the National Institute for Biotechnology Information server. Protein sequences were aligned with the multiple-sequence alignment ClustalW program (49).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of an operon upstream from the ttgGHI genes that is divergently transcribed with respect to the efflux pump genes.

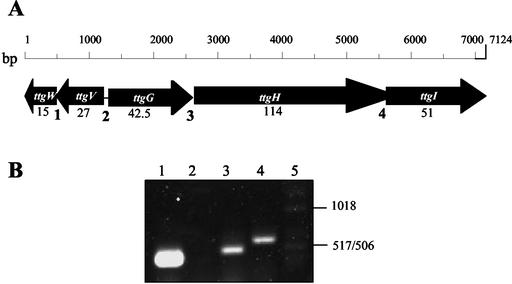

DNA sequencing upstream from the ttgGHI genes by using plasmid pGG1 as a template (43) revealed two ORFs, of 780 and 405 bp (Fig. 1A), separated from each other by 5 bp. These genes were transcribed divergently with respect to the ttgGHI operon. Sequence homology search of the deduced 259- and 134-amino-acid proteins with sequences deposited in several databases showed that the first ORF showed an overall 50 to 60% similarity with a number of transcriptional regulators belonging to the IclR family (i.e., PsrA, IclR, GltR, PcaR, PcaU, PobR, SrpS, etc. [35, 36, 53]), whereas the second ORF showed similarity to members of the TetR family of repressors (i.e., TetR, TtgR, AcrR, MtrR, SrpR, and QacR [6, 9, 12, 13, 19, 22, 24, 46, 53]). We hypothesized that these ORFs encoded proteins involved in the transcriptional control of the ttgGHI efflux pump operon, and we called the first and second ORFs ttgV and ttgW, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Physical organization of the ttgGHI-ttgVW cluster and evidence that ttgVW is an operon. (A) The sequence of the ttgGHI and ttgVW operons can be accessed from GenBank (accession no. AF299253.2). The approximate sizes of the products of each ORF are given in kilodaltons below each gene. (B) The products resulting from each RT-PCR were separated on agarose gels, as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, ttgV-ttgW amplification (expected size, 398 bp); lane 2, ttgV-ttgG amplification (expected size, 437 bp); lane 3, ttgG-ttgH amplification (expected size, 503 bp); lane 4, ttgH-ttgI amplification (expected size, 606 bp); lane 5, molecular weight markers, whose sizes are provided on the right.

To test whether ttgV and ttgW were part of the same transcriptional unit, we prepared total RNA from P. putida DOT-T1E growing on LB medium and RT-PCR assays were done with primers based on ttgV and ttgW on the one hand and ttgV and ttgG on the other. Amplification was obtained only when the ttgV and ttgW primers were used, with the size of the amplified fragment being that predicted from the DNA sequence (Fig. 1B). This result confirmed the presumed operon structure of the cluster. Using primers based on ttgG, ttgH, and ttgI, we also showed that ttgGHI was transcribed as a single transcriptional unit (Fig. 1B).

Transcriptional analysis of the ttgVW operon.

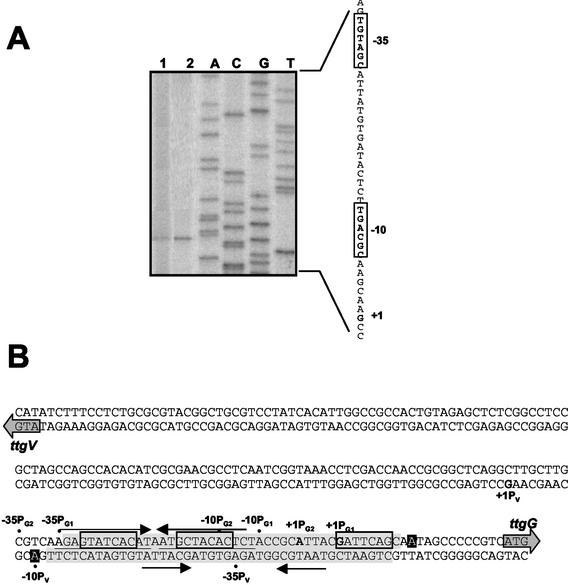

The transcription initiation point of the ttgVW operon was mapped, as described in Materials and Methods, in cells growing in the absence or presence of toluene. Regardless of the growth conditions, the operon was transcribed from a single promoter (Fig. 2A). The 5′ end of the ttgVW mRNA starts at the G marked +1 in the sequence shown in Fig. 2A. The −10 and −35 regions of the ttgV promoter exhibit low similarity to promoters recognized by RNA polymerase with sigma-70 at the −10 region (5′-TGACGC-3′) and the −35 region (5′-TGTAGC-3′). The location of the start sites of the ttgV and ttgG genes indicates that the promoters of the divergently transcribed operons overlap (Fig. 2B). In fact, the −10 and −35 boxes of the ttgVW promoter totally overlap the −35 and −10 boxes, respectively, of the PG2 promoter (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Transcription initiation point of the ttgV gene in P. putida DOT-T1E growing in the absence or presence of toluene. (A) Transcription initiation mapping of the ttgV gene. RNA in lane 1 was isolated from cells grown in LB medium, whereas RNA in lane 2 was extracted from cells grown in LB medium with toluene supplied via the gas phase. The other lanes correspond to a sequencing ladder. The DNA sequence corresponding to the ttgV promoter region is shown on the right. The transcription initiation point is in boldface type and marked +1. The proposed −10 and −35 regions are boxed. (B) Overlap of the ttgV and ttgG promoters and binding region of TtgV protein as determined by in vitro DNaseI footprinting assays. The directions of transcription of ttgVW and ttgGHI are indicated by arrows followed by the notation ttgV or ttgG. The +1 of the single promoter for ttgV and the +1 of the tandem promoters for ttgG are in boldface type and designated +1PV, +1PG1, and +1PG2, respectively. The −10 and −35 positions of each promoter are indicated. The region protected by TtgV is shaded, and hyperreactive sites are shown with white letters in black boxes. The potential inverted repeats are indicated by thin arrows, and potential direct repeats are boxed.

The intensity of the cDNA bands determined densitometrically in Fig. 2A was used to estimate variations in the expression of ttgV in the absence or presence of toluene. We observed that in the presence of toluene the level of expression of the ttgVW operon was three- to fourfold higher than in the absence of the aromatic hydrocarbon. Our group has shown before that there was also a similar level of induction of the ttgGHI operon in the presence of toluene (43). Given that the TtgGHI efflux pump expels a large number of solvents and antibiotics, we decided to determine which of these compounds induced expression from the ttgV and ttgG promoters by analyzing the relative levels of mRNA expressed from these promoters in P. putida DOT-T1E cells growing in LB medium in the presence of solvents and of sublethal concentrations of antibiotics. We observed that both operons were induced about fourfold by toluene and styrene, but not in response to any of the antibiotics tested (i.e., carbenicillin, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, tetracycline, or gentamicin). The same results were obtained when expression was analyzed using fusions of the corresponding promoters to ′lacZ in the low-copy-number promoter probe pMP220 (data not shown).

The set of results presented above indicates that the pattern of inducibility of the ttgVW operon is similar to that of the efflux pump ttgGHI operon, probably because the two promoters are regulated in the same way.

The ttgV gene product, but not that of the ttgW gene, is a repressor of the ttgV and ttgG promoters.

We constructed three different mutant strains in the ttgVW operon as described in Materials and Methods: DOT-T1E-PS62 (TtgV− TtgW+); DOT-T1E-PS61 (TtgV− TtgW−), and DOT-T1E-PS52 (TtgV+ TtgW−). To determine the effect of these mutations on the expression of the ttgGHI and ttgVW operons, we used transcriptional fusions of the corresponding promoters to ′lacZ. Plasmids pANA96 (PttgG::lacZ) and pANA95 (PttgV::lacZ) were transformed in the wild-type DOT-T1E strain and in the three mutant strains. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in the presence and absence of 3 mM toluene (Table 2), and we found that expression from the ttgG promoter was about four times higher in DOT-T1E-PS62 than in the wild-type strain in the absence of toluene (Table 2). This indicates that TtgV is a repressor that prevents the expression of the ttgGHI operon. Expression of the ttgVW promoter was about threefold higher in the ttgV mutant than in the wild-type strain in the absence of toluene, indicating that TtgV controls negatively its own expression.

TABLE 2.

Transcription from the ttgVW and ttgGHI operon promoters determined as β-galactosidase activity using fusions of the operon promoters to ′lacZa

| Fusion and strain | Genetic background | β-Galactosidase activity and growth conditions

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Without toluene | With toluene | ||

| PttgG::lacZ | |||

| Wild type | V+ W+ | 320 ± 20 | 1,400 ± 60 |

| PS62 | V− W+ | 1,100 ± 120 | 1,600 ± 250 |

| PS61 | V− W− | 1,350 ± 120 | 1,500 ± 130 |

| PS52 | V+ W− | 470 ± 50 | 1,230 ± 70 |

| PttgV::lacZ | |||

| Wild type | V+ W+ | 440 ± 80 | 1,600 ± 30 |

| PS62 | V− W+ | 1,100 ± 200 | 1,420 ± 200 |

| PS61 | V− W− | 1,050 ± 150 | 1,720 ± 180 |

| PS52 | V+ W− | 470 ± 30 | 1,310 ± 190 |

The strains were transformed with pANA95 (PttgG::lacZ) or pANA96 (PttgV::lacZ), and cells were grown in LB medium in the absence or presence of 3 mM toluene. β-Galactosidase activity was determined 4 h later in duplicate samples. The data are rounded values of the averages of at least three independent assays.

Expression from the ttgG and ttgV promoters in the mutant background DOT-T1E-PS52 deficient in TtgW but proficient in TtgV was similar to that found in the wild-type strain (Table 2), which suggested that the TtgW protein, under our assay conditions, does not play a major role in the regulation of the expression from either of these two operons. The level of expression from the ttgV and ttgG promoters in the DOT-T1E-PS61 mutant deficient in TtgV and TtgW was similar to that obtained in mutant DOT-T1E-PS62 (ttgV− ttgW+) (Table 2). These results suggest that the TtgV protein is a repressor of its own synthesis as well as of the expression of the ttgGHI operon.

To further corroborate that TtgV is a repressor of expression from ttgG and ttgV, transcription from pANA95 and pANA96 was assayed in the heterologous E. coli DH5αF′ host with or without pANA126 that overproduced TtgV. We found that in the constructions in which TtgV was overproduced the level of expression for PttgG and PttgV was 10 to 20% of the level found in the strain without TtgV, which confirms that TtgV is a repressor of the expression of both operons.

The ttgV mutant is more resistant to toluene than is the wild-type strain.

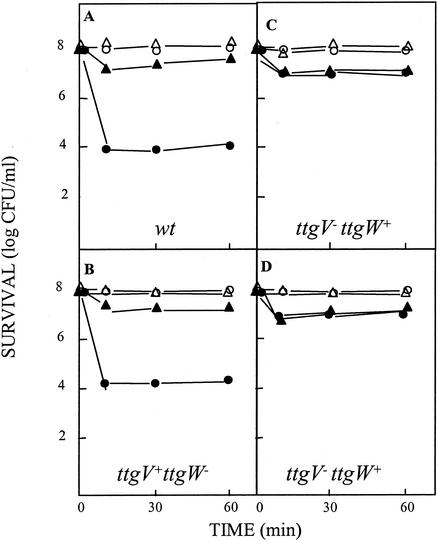

It has previously been reported that the TtgGHI efflux pump is involved in both intrinsic and induced resistance to organic solvents of P. putida DOT-T1E (43). Given that expression from PttgG increased in the mutant deficient in the TtgV protein, we analyzed solvent tolerance in the three mutant strains by determining the survival rate of the cells after a sudden 0.3% (vol/vol) toluene shock when the cultures were pregrown on LB liquid medium with or without toluene in the gas phase. Strain DOT-T1E-PS52 (TtgV+ W−) survived the toluene shock to the same extent as wild-type DOT-T1E (Fig. 3A and C). The survival rate when the cells were not preinduced was around 1 cell per 10,000, whereas almost 1 in 10 cells survived the shock when the cultures were preinduced with toluene in the gas phase. These results correlate with the data presented above, i.e., since the expression of the efflux pump is not significantly increased in this mutant, the tolerance to toluene remains as in the wild type. However, in DOT-T1E-PS62 (ttgV− ttgW+) and in the double mutant DOT-T1E-PS61 (ttgV− ttgW−), we observed an increase in the survival rate of about 2 orders of magnitude, with the levels of survival being almost identical to the levels obtained when the cells were preinduced (compare Fig. 3A, B, and D). These results indicate that an increase in the expression of the TtgGHI efflux pump, such as that found in the mutant deficient in TtgV, increased the survival rate of cells that were suddenly exposed to toluene. Therefore, these results support the notion that TtgV is strongly involved in the solvent-dependent induction of the TtgGHI pump.

FIG. 3.

Survival of P. putida DOT-T1E (A), DOT-T1E-PS62 (B), DOT-T1E-PS52 (C), and DOT-T1E-PS61 (D) after a sudden toluene shock. Cells were grown in 30 ml of LB medium (circles) or LB medium with toluene in the gas phase (triangles) until the culture reached a turbidity of about 0.8 at 660 nm. The culture was divided in two halves; to one we added 0.3% (vol/vol) toluene (closed symbols), while the other was kept as a control (open symbols). The number of viable cells was determined at the indicated times.

Rojas et al. (43) showed that the TtgGHI efflux pump contributed to resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline only in a ΔttgABC mutant background. This indicated a modest role for the TtgGHI pump in antibiotic efflux from the cell. We have now compared the sensitivities of the wild-type and the DOT-T1-PS52, -PS61, and -PS62 mutants to the three antibiotics cited above by determining the MICs that prevented growth. We found no difference in antibiotic resistance between each of the mutants and the wild-type strain (data not shown). These results suggest that the primary role of the TtgGHI efflux pump is to extrude solvents, whereas other antibiotic extrusion pumps operate efficiently in DOT-T1E (Terán et al., unpublished) so that the increased level of TtgGHI in the ttgV mutant backgrounds does not result in a significant increase in antibiotic resistance.

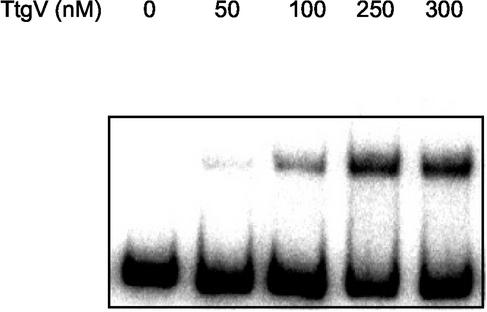

In vitro study of the interactions between the ttgV and ttgG promoter region and the TtgV protein.

The results presented above suggest that the ttgV and ttgG promoters overlap and that the TtgV protein is a transcriptional repressor of the expression of both promoters. A gel mobility shift assay was done to study protein-DNA interactions within the ttgV-ttgG promoter region. A 210-bp DNA fragment containing the sequence between the first nucleotide before the start codon of ttgV and ttgG was synthesized by PCR and labeled with 32P. When this fragment was incubated with increasing concentrations of TtgV, a single shifted band was found (Fig. 4). The retarded band was gradually lost in competition assays in which increasing concentrations of cold DNA probe were used, but not when unspecific competitor DNA [poly(dI-dC)] was used (data not shown). Based on the concentration of the protein that was used and on the degree of retard, we estimated that TtgV had a high affinity for its target, whose range is around 5 × 10−7 M.

FIG. 4.

Interaction of TtgV with the ttgG-ttgV intergenic region. The 210-bp (1 nM) fragment containing the ttgG-ttgV intergenic region was incubated without TtgV or with increasing concentrations of His6-tagged TtgV (from 50 to 300 nM).

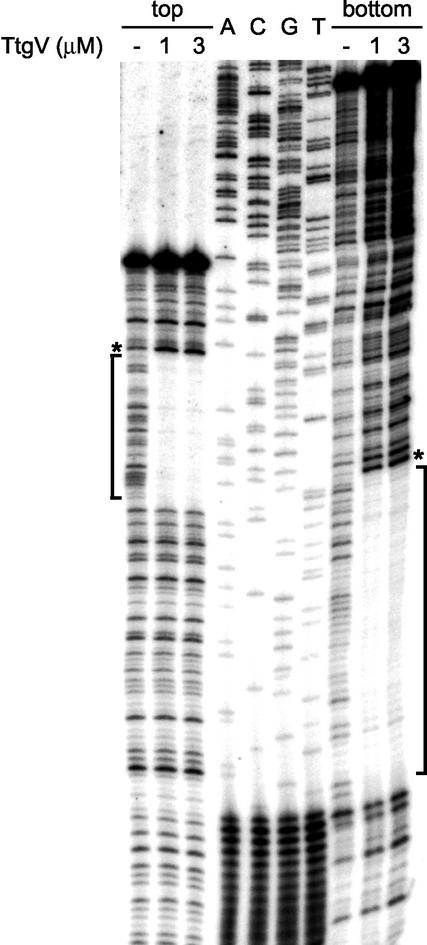

Footprinting assays were carried out to define the region in which TtgV binds within the ttgV-ttgG intergenic region. A 228-bp DNA fragment, which contained the region between +134 and −94 of the ttgV promoter, was generated by PCR and labeled at each of its 5′ ends, incubated with or without His6-TtgV, and then treated with DNase I as described in Materials and Methods. The digestion pattern for the two strands is shown in Fig. 5. The pattern revealed a 40-bp region where the abundance of certain fragments decreased as the TtgV concentration increased. The protected region covers the −10 and −35 regions of each of the ttgG promoters and the divergently oriented ttgV promoter (Fig. 1B). In fact, the protected region extends from +7 to −34 with respect to the ttgG1 promoter (+12 to −29 for the overlapping ttgG2 promoter) and from −13 to −55 for the ttgV promoter (Fig. 1B). Given the overlapping organization of these promoters and the fact that TtgV represses the expression of both operons to the same extent, it is likely that the binding of TtgV to the intergenic region blocks the entry of RNA polymerase to transcribe these promoters (44).

FIG. 5.

Identification of the TtgV operator in the ttgG-ttgV intergenic region by DNase I footprinting. PCR fragments comprising the ttgG-ttgV intergenic region were labeled at one 5′ end and incubated without (−) or with a 1 or 3 μM concentration of purified TtgV before being subjected to DNaseI digestion and electrophoresis as described in Materials and Methods. The regions protected from DNase I digestion by TtgV are shown in brackets; asterisks indicate hyperactive sites. The sequence of the TtgV operator is marked in Fig. 2B.

We found two inverted repeats within the protected region: one located between −12 and −34 with respect to the ttgG1 promoter (−7 to −29 for the ttgG2 promoter and −12 to −36 with respect to ttgV) (Fig. 1B), and the other located between −2 and −24 in PttgG1 (+4 to −19 in PttgG2) and −24 to −46 in the ttgV promoter (Fig. 1B). If the first inverted repeat were the target for TtgV, then it is difficult to explain how TtgV protects the right-most region shown shaded in Fig. 2B. The position of the second inverted repeat is more central and could in principle explain why TtgV bound to this motif covers the adjacent region. It is also interesting to note the presence of three direct repeats in the protected region whose consensus sequence is 5′-GNA/TT/ACAC/G-3′ (Fig. 1B). Examples of transcriptional regulators that recognize direct repeats have been described in the AraC/XylS family of positive transcriptional regulators (10, 51). Although at present we cannot discern which nucleotides are specifically recognized by TtgV, it is worth noting that the QacR regulator interacts with its cognate promoters by recognizing direct repeats within inverted-repeat sequences (46). We cannot, therefore, exclude the possibility that TtgV binds to the left-most inverted repeat and that it recognizes a half site in the right-most protected region. Therefore, further in vitro assays using mutants in the potential target sequences and a wide series of footprint analyses are needed to define the precise motif recognized by TtgV.

In the acrAB operon of E. coli, the AcrR protein functions as the local specific regulator (22), but it has been shown that its level of expression is influenced by global regulators such as MarA, SoxS, and SdiA (22, 38). The genome of P. putida KT2440, a strain highly similar to DOT-T1E, was recently sequenced and annotated (30). Our BLASTN search revealed the presence of a SdiA homolog, but no MarA or SoxS homologs were found. Results from our laboratory seem to rule out the participation of SdiA in the control of ttg efflux pumps, because the overproduction of SdiA did not alter the expression pattern of a transcriptional fusion of each of the ttg promoters to ′lacZ (E. Duque and J. L. Ramos, unpublished results). At present, we have no evidence that the ttgGHI/ttgVW system is integrated in any of the global regulatory circuits that operate in Pseudomonas sp., but future work with the ttgGHI/ttgVW system should reveal more intimate details of its regulation.

Acknowledgments

The first two coauthors contributed equally to this study.

This study was supported by a grant from the European Commission (QLK3-CT-2001-00435) and a grant from the Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (BIO 2003-00515 CICYT-2003).

We thank C. Lorente and M. M. Fandila for assistance, E. Duque for plasmids, strains, and communication of unpublished results, and K. Shashok for checking the use of English in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adewoye, L., A. Sutherland, R. Srikumar, and K. Poole. 2002. The MexR repressor of the mexAB-oprM multidrug efflux operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: characterization of mutations compromising activity. J. Bacteriol. 184:4308-4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., F. W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amsterdam, D. 1991. Susceptibility testing of antimicrobials in liquid media, p. 72-78. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 4.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. F. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1992. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing, New York, N.Y.

- 5.Baranova, N., and H. Nikaido. 2002. The BaeSR two-component regulatory system activates transcription of the yegMNOB (mdtABCD) transporter gene cluster in Escherichia coli and increases its resistance to novobiocin and deoxycholate. J. Bacteriol. 184:4168-4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumeister, R., P. Flache, O. Melefors, A. von Gabain, and W. Hillen. 1991. Lack of a 5′ non-coding region in Tn1721 encoded tetR mRNA is associated with a low efficiency of translation and a short half-life in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:4595-4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruden, D. L., J. H. Wolfram, R. D. Rogers, and D. T. Gibson. 1992. Physiological properties of a Pseudomonas strain which grows with p-xylene in two-phase (organic-aqueous) medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2723-2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Smet, M. J., J. Kingma, and B. Witholt. 1978. The effect of toluene on the structure and permeability of the outer and cytoplasmic membranes of Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 506:64-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duque, E., A. Segura, G. Mosqueda, and J. L. Ramos. 2001. Global and cognate regulators control the expression of the organic solvent efflux pumps TtgABC and TtgDEF of Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1100-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egan, S. M. 2002. Growing repertoire of AraC/XylS activators. J. Bacteriol. 184:5529-5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkins, C. A., and H. Nikaido. 2002. Substrate specificity of the RND-type multidrug efflux pumps AcrB and AcrD of Escherichia coli is determined predominantly by two large periplasmic loops. J. Bacteriol. 184:6490-6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagman, K. E., and W. M. Shafer. 1995. Transcriptional control of the mtr efflux system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 177:4162-4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillen, W., and C. Berens. 1994. Mechanisms underlying expression of Tn10 encoded tetracycline resistance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48:345-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue, A., and K. Horikoshi. 1989. A Pseudomonas thrives in high concentrations of toluene. Nature 338:264-265. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isken, S., and J. A. de Bont. 1996. Active efflux of toluene in a solvent-resistant bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 178:6056-6058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieboom, J., J. J. Dennis, J. A. M. de Bont, and G. J. Zylstra. 1998. Identification and molecular characterization of an efflux pump involved in Pseudomonas putida S12 solvent tolerance. J. Biol. Chem. 273:85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kieboom, J., J. J. Dennis, G. J. Zylstra, and J. A. M. de Bont. 1998. Active efflux of organic solvents by Pseudomonas putida S12 is induced by solvents. J. Bacteriol. 180:6769-6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, K., S. Lee, K. Lee, and D. Lim. 1998. Isolation and characterization of toluene-sensitive mutants from the toluene-resistant bacterium Pseudomonas putida GM73. J. Bacteriol. 180:3692-3696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kojic, M., C. Aguilar, and V. Venturi. 2002. TetR family member PsrA directly binds the Pseudomonas rpoS and psrA promoters. J. Bacteriol. 184:2324-2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koronakis, V., A. Sharft, E. Koronakis, B. Luisi, and C. Hughes. 2000. Crystal structure of the bacterial membrane protein TolC central to multidrug efflux and protein export. Nature 405:914-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, X., L. Zhang, and K. Poole. 1998. Organic solvent-tolerant mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa display multiple antibiotic resistance. J. Bacteriol. 180:2987-2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma, D., M. Alberti, C. Lynch, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1996. The local repressor AcrR plays a modulating role in the regulation of the acrAB gene Escherichia coli by global stress signals. Mol. Microbiol. 19:101-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marqués, S., J. L. Ramos, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Analysis of the mRNA structure of the Pseudomonas putida TOL meta fission pathway operon around the transcription initiation point, the xylTE and the xylFJ region. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1216:227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier, I., L. V. Wray, and W. Hillen. 1988. Differential regulation of the Tn10-encoded tetracycline resistance genes tetA and tetR by the tandem tet operators O1 and O2. EMBO J. 7:567-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ménard, R., P. J. Sansonetti, and C. Parsot. 1993. Nonpolar mutagenesis of the ipa genes defines IpaB, IpaC, and IpaD as effectors of Shigella flexneri entry into epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 175:5899-5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 27.Mosqueda, G., and J. L. Ramos. 2000. A set of genes encoding a second toluene efflux system in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1.E is linked to the tod genes for toluene metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 182:937-943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murakami, S., R. Nakashima, E. Yamashita, and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. Crystal structure of bacterial multidrug efflux transporter AcrB. Nature 419:587-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagakubo, S., K. Nishino, T. Hirata, and A. Yamaguchi. 2002. The putative response regulator BaeR stimulates multidrug resistance of Escherichia coli via a novel multidrug exporter system, MdtABC. J. Bacteriol. 184:4161-4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson, K. E., I. T. Paulsen, C. Weinel, R. J. Dodson, H. Hilbert, D. Fouts, S. R. Gill, M. Pop, M. Holmes, V. Martins Dos Santos, H. Khouri, I. Hance, P. C. Lee, E. Holtzapple, D. Scanlan, K. Tran, R. Deboy, A. Moazzez, L. Brinkac, M. Beanan, S. Daugherty, J. Kolonay, R. Madupu, W. Nelson, O. White, T. Utterback, M. Rizzo, K. Lee, D. Kosack, D. Moestl, H. Wedler, J. Lauber, J. Hoheisel, M. Straetz, S. Heim, C. Kiewitz, J. Eisen, K. N. Timmis, A. Duesterhoft, B. Tümmler, and C. M. Fraser. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. 4:799-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paulsen, I. T., J. Chen, K. E. Nelson, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 2001. Comparative genomics of microbial drug efflux systems. J. Mol. Microbiol. 3:145-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pérez-Martin, J., and V. de Lorenzo. 1996. ATP binding to the sigma 54-dependent activator XylR triggers a protein multimerization cycle catalyzed by UAS DNA. Cell 86:331-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poole, K. 2001. Multidrug resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:500-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poole, K., and R. Srikumar. 2001. Multidrug efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: components, mechanisms and clinical significance. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 1:59-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poole, K., K. Tetro, Z. Zhao, S. Neshat, D. Heinrichs, and N. Bianco. 1996. Expression of the multidrug resistance operon mexA-mexB-oprM in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mexR encodes a regulator of operon expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2021-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popp, R., T. Kohl, P. Patz, G. Trautwein, and U. Gerischer. 2002. Differential DNA binding of transcriptional regulator PcaU from Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 184:1988-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prentki, P., and H. M. Krisch. 1984. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene 29:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahmati, S., S. Yang, A. L. Davidson, and E. L. Zechiedrich. 2002. Control of the AcrAB multidrug efflux pump by quorum-sensing regulator SdiA. Mol. Microbiol. 43:677-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramos, J. L., E. Duque, M. T. Gallegos, P. Godoy, M. I. Ramos-González, A. Rojas, W. Terán, and A. Segura. 2002. Mechanisms of solvent tolerance in gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56:743-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramos, J. L., E. Duque, P. Godoy, and A. Segura. 1998. Efflux pumps involved in toluene tolerance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 180:3323-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramos, J. L., E. Duque, M. J. Huertas, and A. Haïdour. 1995. Isolation and expansion of the catabolic potential of a Pseudomonas putida strain able to grow in the presence of high concentrations of aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Bacteriol. 177:3911-3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramos, J. L., E. Duque, J. J. Rodríguez-Herva, P. Godoy, A. Haïdour, F. Reyes, and A. Fernández-Barrero. 1997. Mechanisms for solvent tolerance in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 272:3887-3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rojas, A., E. Duque, G. Mosqueda, G. Golden, A. Hurtado, J. L. Ramos, and A. Segura. 2001. Three efflux pumps are required to provide efficient tolerance to toluene in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 183:3967-3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rojo, F. 1999. Repression of transcription initiation in bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 181:2987-2991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saier, M. H., and I. T. Paulsen. 2001. Phylogeny of multidrug transporters. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schumacher, M. A., M. C. Miller, S. Grkovic, M. H. Brown, R. A. Skurray, and R. G. Brennan. 2002. Structural basis for cooperative DNA binding by two dimers of the multidrug-binding protein QacR. EMBO J. 21:1210-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sikkema, J., J. A. M. de Bont, and B. Poolman. 1995. Mechanisms of membrane toxicity of hydrocarbons. Microbiol. Rev. 59:201-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spaink, H. P., R. J. H. Okker, C. A. Wijffelman, E. Pees, and B. J. J. Lugtenberg. 1987. Promoters in the nodulation of the Rhizobium leguminosarum Sym plasmid pRL1J1. Plant Mol. Biol. 9:27-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. Clustal W: improv-ing the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tikhonova, E. B., Q. Wang, and H. I. Zgurskaya. 2002. Chimeric analysis of the multicomponent multidrug efflux transporters from gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 184:6499-6507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tobes, R., and J. L. Ramos. 2002. AraC-XylS database: a family of positive transcriptional regulators in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:318-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weber, F. J., S. Isken, and J. A. M. de Bont. 1994. Cis/trans isomerization of fatty acids as a defence mechanism of Pseudomonas putida strains to toxic concentrations of toluene. Microbiology 140:2013-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wery, J., B. Hidayat, J. Kieboom, and J. A. M. de Bont. 2001. An insertion sequence prepares Pseudomonas putida S12 for severe solvent stress. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5700-5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zgurskaya, H., and H. Nikaido. 1999. AcrA is a highly asymmetric protein capable of spanning the periplasm. J. Mol. Biol. 285:409-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]