Abstract

Rhodobacter sphaeroides is a motile bacterium that has multiple chemotaxis genes organized predominantly in three major operons (cheOp1, cheOp2, and cheOp3). The chemoreceptor proteins are clustered at two distinct locations, the cell poles and in one or more cytoplasmic clusters. One intriguing possibility is that the physically distinct chemoreceptor clusters are each composed of a defined subset of specific chemotaxis proteins, including the chemoreceptors themselves plus specific CheW and CheA proteins. Here we report the subcellular localization of one such protein, CheA2, under aerobic and photoheterotrophic growth conditions. CheA2 is predominantly clustered and localized at the cell poles under both growth conditions. Furthermore, its localization is dependent upon one or more genes in cheOp2 but not those of cheOp1 or cheOp3. In E. coli, the polar localization of CheA depends upon CheW. The R. sphaeroides cheOp2 contains two cheW genes. Interestingly, CheW2 is required under both aerobic and photoheterotrophic conditions, whereas CheW3 is not required under aerobic conditions but appears to play a modest role under photoheterotrophic conditions. This suggests that R. sphaeroides contains at least two distinct chemotaxis complexes, possibly composed of proteins dedicated for each subcellular location. Furthermore, the composition of these spatially distinct complexes may change under different growth conditions.

It has been well documented that the localization of some bacterial proteins to specific regions in the cell is essential for their correct functioning. Examples of these include proteins involved in Caulobacter crescentus development, Bacillus subtilis sporulation, and Escherichia coli cell division (for a review, see reference 20). The chemotaxis pathway, which allows bacteria to move in a favorable direction, also has components that are specifically localized within the cell (14). In enteric bacteria, chemotaxis is mediated by a classical two-component signal transduction pathway (for reviews, see references 2, 4, and 26). The protein kinase CheA is phosphorylated on a conserved histidine residue due to a change in the signaling state of a trans-membrane chemoreceptor (trans-MCP). The phosphoryl group is transferred to the response regulator CheY. CheY-P binds to the flagellar switch protein FliM, causing the direction of flagellar rotation to change from counterclockwise to clockwise and ultimately resulting in a change of swimming direction. Adaptation to stable chemoeffector concentrations is accomplished by modification of the chemoreceptors using two enzymes working antagonistically. The constitutively active methyltransferase CheR adds methyl groups to specific glutamate residues of the trans-MCPs, thereby increasing the activity of CheA (1). CheB, when phosphorylated by CheA, removes these methyl groups, thus decreasing CheA activity (12).

In all bacteria and archaea examined thus far, the chemoreceptor complexes are clustered (6, 9, 13, 14). Although the function of clustering is currently unknown, one possibility is that clustering may allow cooperative interactions between receptors, facilitating signal generation, signal amplification and/or adaptation (3, 5, 10, 11, 21). In E. coli, the kinase CheA and the scaffolding protein CheW are also specifically localized to the cell poles (14), where they may form higher order signaling arrays with the chemoreceptors (3, 10, 11, 21).

Many motile bacteria sense and respond to environmental changes by employing variations of the E. coli paradigm. The α-subgroup bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides is a metabolically diverse species that has multiple homologs of the E. coli signaling proteins encoded in three operons and at other unlinked loci (www.jgi.doe.gov/JGI_microbial/html/rhodobacter). cheOp1 contains cheY1, cheA1, cheW1, cheR1, and cheY2. cheOp2 contains cheY3, cheA2, cheW2, cheW3, cheR2, cheB1, and tlpC. cheOp3 contains cheA4, cheR3, cheB2, cheW4, slp, tlpT, cheY6, and cheA3. In total, there are four CheAs, four CheWs, six CheYs, three CheRs, and two CheBs. In addition, there are a CheBRA fusion protein (encoded at a separate locus) and 13 chemoreceptors. Nine chemoreceptors are membrane-spanning and four are cytoplasmic, known as transducer-like proteins (Tlps). Immunoelectron microscopy using an antibody against the highly conserved domain of trans-MCPs showed that receptor proteins are clustered at both the cell poles and in the cytoplasm (9). Specific green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusions showed that the trans-membrane receptor, McpG, was located at the poles (24) and the putative cytoplasmic receptor, TlpC, formed discrete foci within the cytoplasm of the cell (25). Defining the distribution of these Che proteins in the cell and determining their interplay is critical for truly understanding chemotaxis in R. sphaeroides.

CheA2 (encoded in cheOp2) is essential for aerotaxis, phototaxis, and chemotaxis to all compounds tested and for the localization of McpG to the cell pole (15). Deletion of CheA2 results in some, but not total, delocalization of TlpC (25). In contrast, deletion of cheA1 has only minor effects on chemosensing and is not required for either the localization of McpG (15) or TlpC (25). In this study we examined the subcellular localization of CheA2 in R. sphaeroides and systematically investigated the requirement for other signaling proteins in that localization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Strains of R. sphaeroides (Table 1) were grown in succinate medium (22) containing nalidixic acid (25 μg/ml) at 30°C either aerobically with shaking in the dark or anaerobically with illumination at 50 μmol m−2 s−1.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Characteristic | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| WS8 | Wild-type R. sphaeroides | Gift from W. Sistrom |

| WS8N | Spontaneous nalidixic acid-resistant mutant of WS8 | 23 |

| JPA117 | ΔcheOp1 derivative of WS8N | 7 |

| JPA1301 | ΔcheOp3 derivative of WS8N | 17 |

| JPA1340 | ΔcheBRA derivative of WS8N | Gift from S. L. Porter |

| JPA1349 | Δ cheBRA cheY7 derivative of WS8N | Gift from S. L. Porter |

| JPA211 | ΔcheA2 derivative of WS8N | 7 |

| JPA470 | ΔtlpC derivative of WS8N | 25 |

| JPA514 | ΔcheW2 derivative of WS8N | 15 |

| JPA517 | ΔcheB1 derivative of WS8N | 16 |

| JPA527 | ΔcheW3 derivative of WS8N | 15 |

| JPA531 | WS8N containing an Ω cartidge interrupting transcription and translation of mcpG | 24 |

| JPA565 | ΔcheR2 derivative of WS8N | 16 |

Antibody production.

Purified His-tagged CheA2 was made as described previously (17). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to His-tagged CheA2 (Eurogentec) detect both His-tagged CheA2 protein and a protein from R. sphaeroides WS8N extracts of the expected molecular mass (69.4 kDa). This immunoreactive protein was absent from the ΔcheA2 control strain (JPA211). The antiserum was immunodepleted before use with acetone powders prepared from JPA211 by standard methods (8).

Electron microscopy.

Motile cultures of R. sphaeroides were fixed, embedded in LR-White resin, sectioned and placed on nickel grids as described previously (9). Immunoelectron microscopy was performed using a 1:500 dilution of primary antibody and a 1:30 dilution of secondary antibody (12-nm-diameter colloidal gold particles conjugated to goat antibody to rabbit immunoglobulin G; Jackson Immunoresearch) as described previously (9).

The intracellular positions of all gold particles in longitudinal sections of predivisional cells were recorded. Gold particles within 20 nm of the membrane were scored as being membrane associated. These were further subdivided into those along the lateral membrane (lateral) and those associated with the polar membrane (polar). We also tracked the colocalization (clustering) of gold particles. For this study, a cluster was defined as three or more gold particles each located no more than 20 nm from its neighbor, together with any outlying particles that were no more than 40 nm from the core cluster. Statistical analysis was performed using the χ2 test.

Immunoblotting.

Because the packing of proteins can influence the number of gold particles, using immunoelectron microscopy, CheA2 levels were monitored by immunoblotting. Motile cells (1 ml, optical density at 700 nm = 0.6) were harvested and resuspended in 100 μl of sample buffer (0.05 M Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 10% glycerol, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.05 M dithiothreitol, 0.01% bromophenol blue), and 10 μl was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12% polyacrylamide) and electroblotted by standard methods (18). The membranes were blocked in 5% dried milk, incubated for 1 h in preabsorbed sera diluted 1/2,000 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% dried milk, and washed extensively with PBS. The membrane was then blocked in PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20, incubated for 1 h with a 1/1,000 dilution of anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Dako), and washed, and bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

To determine the copy number of CheA2 in the cell, quantitative immunoblots of dilution series of WS8N extracts (prepared as above) and CheA2 protein were performed. The mean of results frp, three independent experiments was taken.

RESULTS

Localization of CheA2.

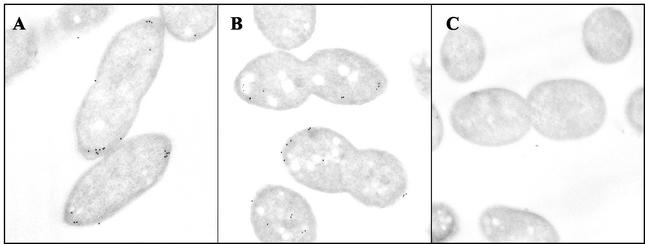

To determine the localization of CheA2 in aerobically grown cells, immunoelectron microscopy experiments were performed using CheA2 antibody on ultrathin sections of wild-type cells. Of the gold particles, 78% were associated with the membrane, and 86% of these were polar (67% of the total particles) (Fig. 1; Table 2). Analysis of the polar signal revealed that typically, more gold particles were seen at one pole than at the other (71% of cells had at least two more particles at one pole than at the other), perhaps reflecting a bias for the localization of CheA2 to the older pole. Polar CheA2 was moderately clustered (52%). There were on average 8.6 gold particles per cell section, with very little noise evident (0.4 particles per cell in the ΔcheA2 control strain, JPA211). Therefore, the antibody does not cross-react with the other CheA species. Some CheA2 is found in the cytoplasm (1.9 cytoplasmic particles per cell compared to 0.2 in JPA211), but no specific positioning of the gold particles was observed and they were not clustered. Thus, the majority of CheA2 is localized to the poles of the R. sphaeroides cell.

FIG. 1.

CheA2 localizes predominantly to the cell poles in R. sphaeroides cells. Ultrathin sections of wild-type cells grown aerobically (A) and photoheterotrophically (B) were incubated with an antibody to CheA2 and detected with an anti-rabbit colloidal gold conjugate. Few gold particles are present in JPA211, a strain lacking cheA2 (C). The micrographs show the location of CheA2 as detected by immunoelectron microscopy experiments using an antibody to CheA2.

TABLE 2.

Spatial distribution of CheA2 in aerobically grown wild-type strains and deletion mutantsa

| Strain | No. polar | Polar in clusters | No. lateral | No. cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic in clusters | No. of particles/section | No. of polar particles/section | No. of cytoplasmic particles/section |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WS8N | 930 | 482 | 146 | 304 | 9 | 8.6 | 5.8 | 1.9 |

| ΔcheA2 | 33 | 10 | 14 | 33 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| ΔcheR2 | 838 | 364 | 100 | 186 | 3 | 7.0 | 5.2 | 1.2 |

| ΔcheB1 | 817 | 321 | 90 | 171 | 6 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 1.1 |

| ΔtlpC | 781 | 320 | 89 | 199 | 0 | 6.7 | 4.9 | 1.2 |

| ΔcheW2 | 175 | 9 | 222 | 743 | 0 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| ΔcheW3 | 651 | 259 | 171 | 258 | 12 | 6.8 | 4.1 | 1.6 |

For each strain 160 longitudinal sections were scored.

Dependence of CheA2 localization on components of cheOp1 and cheOp3, on CheBRA, and on McpG under aerobic conditions.

To determine whether Che proteins encoded by cheOp1, cheOp3, or cheBRA were required for the polar localization of CheA2, immunoelectron microscopy was performed on sections of strains with deletions of cheOp1 (JPA117), cheOp3 (JPA1301) and cheBRA (JPA1340). Since both CheA2 and CheW2 are required for the localization of McpG under aerobic conditions (15), we also examined the requirement for McpG in CheA2 localization in a strain in which mcpG had been insertionally inactivated by an Ω cartridge (JPA531) (24). The data obtained from all these strains were very similar to those obtained from wild-type cells (data not shown). Therefore, none of the components of cheOp1 or cheOp3 (which include genes encoding CheA1, CheA3, CheA4, CheW1, and CheW4), cheBRA, or mcpG are required for CheA2 localization.

Dependence of CheA2 localization on components of cheOp2 under aerobic conditions.

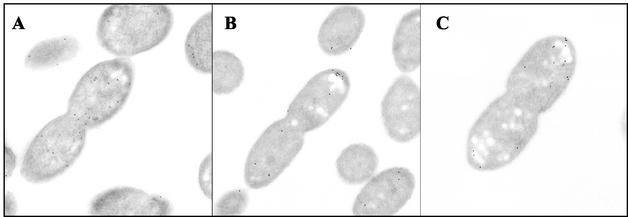

Proteins encoded within the same operon as CheA2 were examined, individually, for any role in CheA2 localization. The pattern of CheA2 localization in strains from which cheW3 (JPA527), cheR2 (JPA565), cheB1 (JPA517), and tlpC (JPA470) were deleted was not significantly different from that of the wild-type strain (P > 0.05) (Table 2). In the absence of CheW2 (JPA514), however, the number of polar gold particles decreased dramatically (1.0 and 5.8 polar membrane particles in cells lacking cheW2 and in the wild type, respectively) (Table 2; Fig. 2). Only 15% of the signal was polar (compared to 67% for the wild type) and very few polar particles were in clusters (5%). There was a concomitant 2.4-fold increase in the number of cytoplasmic particles and an apparent 1.5-fold increase in the number of lateral membrane particles. Despite there being an increase in the number of cytoplasmic and lateral particles, they were not clustered. These data show that CheW2 is required for normal CheA2 polar localization and clustering.

FIG. 2.

The localization of CheA2 in aerobically grown cells is significantly affected by a deletion of cheW2 (A), only slightly affected by the deletion of cheW3 under aerobic conditions (B), and moderately affected by the deletion of cheW3 under photoheterotrophic conditions (C). The micrographs show the location of CheA2 as detected by immunoelectron microscopy experiments using an antibody to CheA2.

Dependence of CheA2 localization under photoheterotrophic conditions.

We have previously shown that CheW3 has a more pronounced role in chemotaxis and in McpG localization under photoheterotrophic conditions than under aerobic conditions (15). Therefore, we addressed whether CheW3 had a role in the localization of CheA2 in cells grown photoheterotrophically.

The pattern of CheA2 localization in photoheterotrophically grown wild-type cells was very similar (P > 0.05) to that observed in aerobically grown cells (Fig. 1). The amount of signal, however, was approximately twofold lower (3.9 and 8.6 spots per cell section under photoheterotrophic and aerobic conditions, respectively). When grown photoheterotrophically, 75% of the gold particles were associated with the membrane and 88% of these were polar (Table 3). Clustering of the polar particles was lower than in aerobically grown cells (27 and 52%, respectively) but may be a consequence of the lower signal observed (2.6 and 5.8 polar membrane particles under photoheterotrophic and aerobic conditions, respectively).

TABLE 3.

Spatial distribution of CheA2 in photoheterorophically grown wild-type strains and deletion mutantsa

| Strain | No. polar | Polar in clusters | No. lateral | No. cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic in clusters | No. of particles/section | No. of polar particles/section | No. of cytoplasmic particles/section |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WS8N | 415 | 113 | 59 | 154 | 3 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 1.0 |

| ΔcheA2 | 105 | 0 | 14 | 50 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| ΔcheW2 | 103 | 0 | 123 | 444 | 23 | 4.2 | 0.6 | 2.8 |

| ΔcheW3 | 368 | 188 | 104 | 188 | 16 | 4.1 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

For each strain 160 longitudinal sections were scored.

In the absence of CheW2, under photoheterotrophic conditions, the percentage of particles that were polar decreased from 66 to 15% (P < 0.001) (Table 3), consistent with a critical requirement for CheW2 under these conditions. The 4.3-fold decrease in the average number of polar particles was accompanied by a 2.8-fold increase in the cytoplasmic signal and a 2.1-fold increase in the lateral membrane signal. Interestingly, in the absence of CheW3, the percentage of polar particles decreased to 56%, a much smaller but nevertheless statistically significant reduction (P < 0.05) (Table 3). In addition, a concomitant increase in the number of cytoplasmic and lateral particles was observed in cells lacking CheW3 (Fig. 2). These data demonstrate that CheW2 and, to a lesser extent, CheW3 are required for the normal localization of CheA2 under photoheterotrophic conditions.

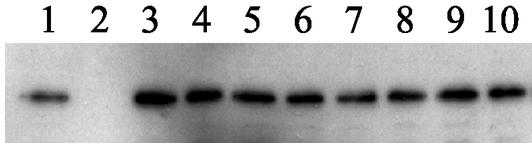

Expression of CheA2 is not affected by the deletion of other che genes.

Quantitative immunoblots of CheA2 in the appropriate deletion strains were performed to ensure that any observed differences in the pattern of CheA2 localization was not due to changes in CheA2 expression levels. In aerobic cells the level of CheA2 remained constant in all the strains used in this study, with the exception of JPA211, the negative control (Fig. 3). Under photoheterotrophic conditions, the total level of CheA2 was reduced, but at a consistent level, in all strains except the negative control strain. Therefore, the CheA2 localization pattern in the deletion strains was not influenced by CheA2 levels under either environmental condition.

FIG. 3.

Expression of CheA2 is not affected by the deletion of other Che proteins. Shown is a quantitative immunoblot of CheA2 in the wild type (lane 1) and in all the appropriate deletion strains under aerobic conditions: ΔtlpC (lane 3), ΔcheB1 (lane 4), ΔcheR2 (lane 5), ΔcheW3 (lane 6), ΔcheW2 (lane 7), ΔcheBRA (lane 8), ΔcheOp3 (lane 9), and ΔcheOp1 (lane 10). There is no band in the ΔcheA2 negative control (lane 2).

Quantitative immunoblots using known amounts of purified CheA2 protein showed that the number of copies of CheA2 in R. sphaeroides was approximately 7,000 and 1,000 per cell under aerobic and photoheterotrophic conditions, respectively. This is consistent with the lower signal observed in photoheterotrophic cells by immunoelectron microscopy.

DISCUSSION

CheA2 is the most highly expressed CheA in R. sphaeroides (19) and is essential for all measured responses under both aerobic and photoheterotrophic conditions (15). Here we show that CheA2 is clustered at the cell pole. It is now well established that the chemoreceptors form clusters or signaling complexes at the cell poles of a variety of bacterial species (6, 14). In R. sphaeroides, however, receptors are clustered at the cell poles and in the cytoplasm (9). We have previously shown using GFP fusions that McpG predominately localizes to the poles (24) whereas TlpC localizes to cytoplasmic foci. It seems probable that CheA2 forms part of a polar signaling complex that includes McpG.

CheA2 was only moderately clustered at the cell pole (52% of polar membrane particles are clustered). One intriguing possibility is that CheA1, CheA3, and/or CheA4 is in the same signaling array and, therefore, reduces the density of CheA2 within this array. It remains to be determined, however, if these other CheA homologs localize to the cell poles or to the cytoplasmic cluster. Interestingly, the pattern of localization of CheA2 was the same in cells grown aerobically and photoheterotrophically even though the copy number of CheA2 protein was sevenfold higher in aerobically grown cells, suggesting no significant redistribution of CheA2 under these different environmental conditions.

Deletion of cheW2 resulted in a major reduction in the polarity and clustering of CheA2 in both aerobic and photoheterotrophic cells. In the absence of CheW2, CheA2 was predominantly in the cytoplasm although some CheA2 was also associated with the lateral membrane (Fig. 2). These data are consistent with those from E. coli, where CheW (the only CheW in E. coli) was found to be required for the polarity of both the chemoreceptors and CheA (14). Deletion of cheW3 resulted in a modest reduction in CheA2 polar localization only in photoheterotrophically grown cells, suggesting that CheW2 is absolutely essential for CheA2 localization while CheW3 may only be required for optimal CheA2 localization in photoheterotrophic cells. These results are consistent with previously published data that described the localization of McpG (15). There is evidence that the chemoreceptors of R. sphaeroides are differentially expressed according to the environmental condition (9); therefore, the receptors that are more highly expressed under photoheterotrophic conditions may require both CheW2 and CheW3 for optimal packing in the array.

Deletion of mcpG does not affect CheA2 localization. The absence of a single, albeit highly expressed chemoreceptor, is insufficient to disorder the polar CheA2 cluster. In E. coli, CheA and CheW polar clustering is disrupted in the absence of all of the chemoreceptors (14); however, expression of one chemoreceptor is sufficient to sequester both CheA and CheW to the cell poles (13, 14). Thus, CheA is targeted to the pole provided that at least one chemoreceptor is present (14). Given that R. sphaeroides has eight additional predicted membrane receptors, the localization of CheA2 in the absence of McpG is not surprising.

In R. sphaeroides, there appear to be two discrete regions in the cell that are absolutely required for chemotactic response: the cell poles and the cytoplasmic foci. Whether there is communication between the two loci to produce a balanced response at the single flagellar motor is the subject of ongoing experimentation. In the absence of CheA2 there was a small, yet consistent, delocalization of TlpC-GFP fluorescence. It seems likely that deletion of cheA2 affects the stoichiometry of other CheA, CheW, and receptor proteins, resulting in a modest TlpC delocalization as CheA2 was not found associated with the cytoplasmic clusters and therefore probably does not have a major role in signaling from the cytoplasmic receptors.

These data are consistent with a recently proposed model (15) which suggests that there are polar signaling arrays containing up to nine chemoreceptor homologs, CheA2, CheW2, and, under photoheterotrophic conditions when different receptors may be expressed, CheW3. Similarly, the cytoplasmic clusters may be composed of up to four soluble receptors, including TlpC (25) and other dedicated CheA and CheW proteins. Interestingly, it is also likely that these spatially distinct complexes also share one or more components and may be more dynamic, as evidenced by the dual role that CheW3 plays in signaling from both polar and cytoplasmic clusters (15, 25).

We have shown that genes in both cheOp2 and cheOp3 are essential for chemotaxis and that proteins encoded by the two operons are found in two locations, the cell poles and a cytoplasmic cluster. Disruption of either the polar or cytoplasmic cluster appears to result in the loss of taxis (15). The data presented here show that CheA2, itself essential for all tactic responses (15), is found only in the polar clusters and not in the cytoplasmic cluster. This suggests that essential chemosensory proteins may be differentially targeted to different cellular locations.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful for the numerous members of the Maddock laboratory for data collection help and to Ken Balazovich for keeping the TEM running optimally.

This research was funded by the American Cancer Society, grant RSG-01-090-01-MCB (J.R.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Borkovich, K. A., L. A. Alex, and M. I. Simon. 1992. Attenuation of sensory receptor signaling by covalent modification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:6756-6760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourret, R. B., and A. M. Stock. 2002. Molecular information processing: lessons from bacterial chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 277:9625-9628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray, D., M. D. Levin, and C. J. Morton-Firth. 1998. Receptor clustering as a cellular mechanism to control sensitivity. Nature 393:85-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bren, A., and M. Eisenbach. 2000. How signals are heard during bacterial chemotaxis: protein-protein interactions in sensory signal propagation. J. Bacteriol. 182:6865-6873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gestwicki, J. E., and L. L. Kiessling. 2002. Inter-receptor communication through arrays of bacterial chemoreceptors. Nature 415:81-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gestwicki, J. E., A. C. Lamanna, R. M. Harshey, L. L. McCarter, L. L. Kiessling, and J. Adler. 2000. Evolutionary conservation of methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins location in Bacteria and Archaea. J. Bacteriol. 182:6499-6502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamblin, P. A., B. A. Maguire, R. N. Grishanin, and J. P. Armitage. 1997. Evidence for two chemosensory pathways in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1083-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harlow, E., and L. Lane. 1988. Antibodies: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 9.Harrison, D. M., J. Skidmore, J. P. Armitage, and J. R. Maddock. 1999. Localization and environmental regulation of MCP-like proteins in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 31:885-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, S. H., W. Wang, and K. K. Kim. 2002. Dynamic and clustering model of bacterial chemotaxis receptors: structural basis for signaling and high sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11611-11615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levit, M. N., Y. Liu, and J. B. Stock. 1998. Stimulus response coupling in bacterial chemotaxis: receptor dimers in signalling arrays. Mol. Microbiol. 30:459-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lupas, A. N., and J. Stock. 1989. Phosphorylation of an N-terminal regulatory domain activates the CheB methylesterase in bacterial chemotaxis. J. Biol. Chem. 264:17337-17342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lybarger, S., and J. R. Maddock. 2000. Differences in the polar clustering of the high- and low-abundance chemoreceptors of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:8057-8062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maddock, J. R., and L. Shapiro. 1993. Polar location of the chemoreceptor complex in the Escherichia coli cell. Science 259:1717-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin, A. C., G. H. Wadhams, and J. P. Armitage. 2001. The roles of the multiple CheW and CheA homologues in chemotaxis and in chemoreceptor localization in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1261-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin, A. C., G. H. Wadhams, D. S. H. Shah, S. L. Porter, J. C. Mantotta, T. J. Craig, P. H. Verdult, H. Jones, and J. P. Armitage. 2001. CheR- and CheB-dependent chemosensory adaptation system of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 183:7135-7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porter, S. L., A. V. Warren, A. C. Martin, and J. P. Armitage. 2002. The third chemotaxis locus of Rhodobacter sphaeroides is essential for chemotaxis. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1081-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook, J., and J. B. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 19.Shah, D. S., S. L. Porter, A. C. Martin, P. A. Hamblin, and J. P. Armitage. 2000. Fine tuning bacterial chemotaxis: analysis of Rhodobacter sphaeroides behaviour under aerobic and anaerobic conditions by mutation of the major chemotaxis operons and cheY genes. EMBO J. 19:4601-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro, L., H. H. McAdams, and R. Losick. 2002. Generating and exploiting polarity in bacteria. Science 298:1942-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu, T. S., and D. Bray. 2002. Modelling the bacterial chemotaxis receptor complex. Novartis Found. Symp. 247:162-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sistrom, W. R. 1960. A requirement for sodium in the growth of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. J. Gen. Microbiol. 22:778-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sockett, R. E., J. C. A. Foster, and J. P. Armitage. 1990. Molecular biology of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides flagellum. FEMS Symp. 53:473-479. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wadhams, G. H., A. C. Martin, and J. P. Armitage. 2000. Identification and localization of a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol. Microbiol. 39:223-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wadhams, G. H., A. C. Martin, S. L. Porter, J. R. Maddock, J. C. Mantotta, H. M. King, and J. P. Armitage. 2002. TlpC, a novel chemotaxis protein in Rhodobacter sphaeroides, localizes to a discrete region in the cytoplasm. Mol. Microbiol. 46:1211-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Webre, D. J., P. M. Wolanin, and J. B. Stock. 2003. Bacterial chemotaxis. Curr. Biol. 13:R47-R49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]