Abstract

The application of X-ray diffraction has allowed the structure of the ligand-binding core of AMPA receptors to be determined. Here I review the insights that this has given into the molecular mechanisms of activation and desensitization of these receptors.

Ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) are ligand-gated ion channels that couple the binding of agonists to a soluble ligand-binding core to the opening and desensitization of a transmembrane ion channel (Madden, 2002). Because iGluRs are essential to the development and function of the human nervous system, are linchpins of learning and memory and are implicated in a number of disease and injury states ranging from schizophrenia to stroke, there is substantial motivation to understand their molecular structures and develop relationships between structure and function (Dingledine et al. 1999; Lees, 2000). Moreover, because iGluRs are accessible to a wide range of biophysical probes, detailed molecular studies of iGluRs may provide important paradigms for understanding ion channels and receptor proteins in general.

iGluRs are composed of four subunits in which each protomer comprises four discrete regions (Paas, 1998), as illustrated in Fig. 1. In 1995, the Keinanen group took advantage of previous studies which defined, to a significant extent, the boundaries of the agonist binding core, or the so-called S1 and S2 regions of the receptor (Stern-Bach et al. 1994) and designed a water-soluble, mini-receptor that only included the agonist binding core (Kuusinen et al. 1995). Kuusinen et al. made an S1S2 construct of the AMPA-sensitive GluR4 (or GluRD) receptor that was secreted from either insect or Escherichia coli cells as a soluble protein and that retained the essential ligand-binding characteristics of the intact receptor (Kuusinen et al. 1995). While these early studies demonstrated the potential feasiblility of S1S2 constructs as vehicles for investigating structure and function relationships in iGluRs, there was not yet a convenient mechanism for over-producing the S1S2 receptor fragments in sufficiently large quantities for structural studies. My laboratory found that the rat GluR2 (flop) S1S2 construct could be produced in large quantities in a functionally active state, and we subsequently produced well-ordered crystals in the presence of the partial agonist kainate (Chen et al. 1998), thus enabling structural analysis by X-ray diffraction.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the domain architecture of single GluR2 receptor polypeptide.

The amino terminus, which begins the amino terminal domain (ATD), is located extracellularly. The ligand-binding core, also located in the extracellular space is composed of discontinuous polypeptide segments S1 and S2. The ion channel is formed by the membrane-embedded domains 1, P, 2 and 3 while the carboxy terminal domain (CTD) is located on the inside of the cell. The GluR2 S1S2 constructs are generated by deleting the ATD, coupling the end of S1 to the beginning of S2 via a Gly-Thr linker and deleting the final transmembrane segment by ending the polypeptide near the end of S2.

The crystal structure of the GluR2 S1S2–kainate complex showed that the receptor fragment had a ‘clam-shell’-like shape and that agonist was bound in the cleft between each shell (Armstrong et al. 1998). The fold of the GluR2 S1S2 protein bore great similarity to the fold of its bacterial relatives, as previously suggested (Nakanishi et al. 1990; Stern-Bach et al. 1994). Nevertheless, there were also important differences, the most significant being the mode by which ligands bound to the protein and the presence of additional elements of secondary structure, such as helix F (Armstrong et al. 1998). In addition, the structure of the GluR2 S1S2 fragment defined the location of the disulphide bond conserved in all iGluRs and the location of conserved hydrophobic residues, predicted to form subunit–subunit contacts in the intact receptor. Lastly, this first structure provided a view of the agonist binding pocket and defined the location of key residues mediating agonist-specific interactions. However, we did not yet have structures for a number of key states that included the apo form, the antagonist-bound state, and complexes of the S1S2 core with agonists such as glutamate, AMPA and quisqualate.

Forming crystals of the GluR2 S1S2 construct under a wide range of conditions, with a variety of ligands, required the development of a new construct because the construct employed in the initial structure determination did not form sufficiently diffractive crystals with other ligands. By removing a few amino acids from the amino terminus of S1 and the carboxy terminus of S2, as well as shortening the linker between S1 and S2 to a Gly-Thr dipeptide, we obtained a construct that has crystallized in the presence of every ligand examined to date (Armstrong & Gouaux, 2000). Subsequent studies involved determination of the structures of the apo form, the complex formed with 5,6-dinitroquinoxalinedione (DNQX), and the glutamate/AMPA-bound states (Armstrong & Gouaux, 2000). As a result of these experiments, we reached a few basic conclusions. First, the GluR2 S1S2 ‘clamshell’ was most open in the apo state, i.e. the cleft was most expanded, and antagonists such as DNQX stabilized the cleft-open state, interacting primarily with preorganized residues on domain 1. In addition, the competitive nature of DNQX was clearly visualized as the consequence of its binding to residues that had previously been shown to be essential for agonist binding.

A second insight gleaned from these studies came from comparing the conformation of the ‘clamshell’ in the apo and glutamate/AMPA-bound states. These comparisons showed that the conformations of the receptor fragment in the presence of glutamate and AMPA were identical within experimental error, and that the clamshell in the glutamate/AMPA conformation was ∼21 deg more ‘closed’ in comparison to the apo state. This result then immediately suggested that the fundamental conformational change involved in activation of the ion channel was the closure of the clamshell. Importantly, however, further comparisons to the kainate-bound state showed that kainate produced a degree of domain closure that was intermediate between the apo and glutamate/AMPA states. Because kainate is known to be a partial agonist, we therefore put forward the hypothesis that the degree of domain closure in the S1S2 construct is correlated with the extent of receptor activation.

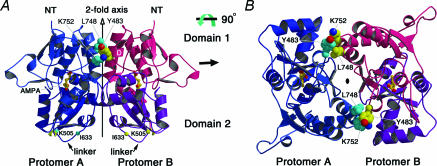

A third and perhaps more significant observation provided by the apo, DNQX and glutamate/AMPA structures was that the S1S2 fragment showed a strict propensity to crystallize in a specific, dimeric arrangement. Even though there was no evidence that the S1S2 construct formed dimers in solution, or that a dimeric S1S2 interface existed in the intact receptor, the dimer seen in the aforementioned crystal forms possessed a number of striking features. For example, a number of conserved and hydrophobic residues were present in the dimer interface, the dimer interface was large and buried ∼1500 Å2 on each subunit; and residues implicated in modulation of receptor activity were present in the dimer interface. Taken together, these observations all pointed to the biological relevance of the dimer interface (Armstrong & Gouaux, 2000). Shown in Fig. 2 is a cartoon of the GluR2 S1S2 dimer, in which a mutation of Leu to Tyr has been introduced at residue 483 in order to stabilize the dimer interface (Stern-Bach et al. 1998).

Figure 2. The GluR2 S1S2 ligand-binding core dimer.

A, view of the dimer perpendicular to the molecular two-fold axis with protomer A on the left and protomer B on the right. The two juxtamembrane linkers are on the ‘bottom’ of the dimer and the amino terminus of S1 is on the ‘top’. Residue 483, which when changed from a leucine to a tyrosine gives rise to a non-desensitizing phenotype, is located in the dimer interface and is sandwiched between Leu748 and Lys 752 on helix J of the two-fold-related subunit. B, view of the dimer from the ‘top’, parallel to the molecular two-fold axis, showing the two symmetry-related interaction sites between the protomers (Sun et al. 2002).

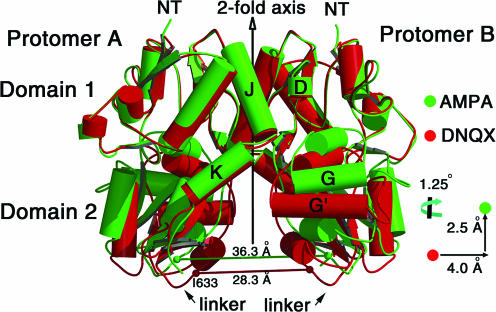

The crystallographic dimer observed in the apo, DNQX and glutamate/AMPA crystal forms provided a simple mechanism by which the binding of agonist and the closure of the clamshell could be coupled to the activation or opening of the ion channel gate. We found that, in the context of the dimer, the separation between the portions of the receptor coupled to the ion channel increased by ∼8 Å on going from the apo to the glutamate/AMPA-bound state. Therefore, we suggested that the fundamental mechanism for ion channel gating involved the direct mechanical coupling of agonist-induced domain closure to the opening of the ion channel by the physical separation of the so-called ‘linker’ regions of the protein (Armstrong & Gouaux, 2000), as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3. Liganded states of the GluR2 S1S2 L483Y dimer.

During the rearrangement between the antagonist-bound state and the agonist-bound state, the ‘linker’ regions that are proximal to the ion channel gate undergo an increase in their separation of ca 8 Å. Shown here are two different liganded states of the GluR2 S1S2 L483Y dimer. In red is the structure of the complex formed with the antagonist DNQX and in green is the structure of the complex formed with AMPA. Here, we suggest that the domain closure of each subunit that occurs upon agonist binding is coupled to a separation of the linker regions and that it is this conformational change that opens the ion channel.

A final significant observation that emanated from the comparison of the glutamate/AMPA complexes involved determining the molecular basis for agonist specificity. Surprisingly, we discovered that even though the α-substituents of AMPA and glutamate bound to the receptor identically, the γ-substituents occupied different subsites in the agonist binding pocket. In particular, the 5-methyl group of AMPA caused the isoxazole ring to shift to a different portion of the binding site compared to the shift caused by glutamate's γ-carboxylate, and in doing so the isoxazole ring displaced a water molecule present in the glutamate complex. Interestingly, AMPA recruited a water molecule to occupy one of the binding pockets utilized by a γ-carboxylate oxygen of glutamate. Thus, we see that the glutamate binding site of AMPA receptors contains a number of ordered water molecules, in addition to flexible side chains, and that both the ordered water molecules and selected side chains can rearrange in response to agonist or antagonist binding (Armstrong & Gouaux, 2000).

Even though the relationships between agonist binding and domain closure within a single ligand-binding core were relatively convincing, it was still unclear how the closure of a single ‘clamshell’ was coupled to the opening of the ion channel gate. Moreover, we still did not understand the structural basis for desensitization. Therefore, we embarked on a series of crystallographic, electrophysiological and sedimentation studies of the GluR2 S1S2 ligand-binding core in which we introduced mutations that had been previously been shown to modulate densensitization and in which we combined the GluR2 S1S2 ligand-binding core with cyclothiazide, a small molecule that blocks desensitization (Sun et al. 2002).

On the basis of these studies, we found that stabilization of the dimer interface blocked desensitization and that the more stable the GluR2 S1S2 dimer was in solution, as determined by sedimentation equilibrium studies, the less the full-length, membrane-bound receptor desensitized, as judged by rapid solution exchange, patch-clamp experiments (Fig. 4). Thus, rearrangement of the dimer interface was coupled to receptor desensitization and was the molecular ‘clutch’ of the receptor. Not only did these studies provide new insight into the molecular basis of desensitization, they also demonstrated that gating of the ion channel was the consequence of separation of regions of each subunit, in the dimer, that occurred upon agonist binding. Shown in Fig. 5 is a mechanistic scheme to describe the relationship beteen specific structural and functional states in the GluR2 receptor.

Figure 4. Strength of the dimer is inversely correlated with the free energy of receptor desensitization.

A graph showing that the strength of the dimer interface, as measured by the free energy of dimer dissociation, is inversely correlated to the free energy of receptor desensitization. In other words, the more tightly the dimer is held together, the less favourable is receptor desensitization. Mutations like L483Y and the small molecule cyclothiazide block desensitization by stabilizing the dimer interface, preventing it from rearranging, and thus ‘forcing’ the receptor to exclusively couple the conformational change of domain closure to the gating or opening of the ion channel.

Figure 5. Schematic diagram showing the relationships between the conformational changes at the ligand-binding core, the dimer interface and the ion channel gate.

Here, only two subunits of the tetrameric receptor are shown. One subunit is in front, with the ligand-binding domains in grey and blue, and the second, two-fold-related subunit is at the back, with the ligand-binding domains in pink and purple. Glutamate is schematized as a red sphere, binding in the cleft between domain 1 (D1) and domain 2 (D2) (Sun et al. 2002). In this figure, the mechanism shows the receptor entering a desensitized state from either a closed state or from an open state, although other mechanisms have been suggested.

In conclusion, while structural studies of the GluR2 receptor have advanced our understanding of central structure and function relationships, there are numerous questions that remain unanswered, the most prominent one being, of course, the structure of the intact receptor. In addition, we have no information, at the molecular level, on non-competitive antagonists, positive allosteric modulators, and channel blockers. Over the coming years, we hope that studies in this laboratory, as well as in others, will continue to advance our understanding of this important class of ligand-gated ion channels.

References

- Armstrong N, Gouaux E. Mechanisms for activation and antagonism of an AMPA-sensitive glutamate receptor: Crystal structures of the GluR2 ligand binding core. Neuron. 2000;28:165–181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong N, Sun Y, Chen G-Q, Gouaux E. Structure of a glutamate receptor ligand binding core in complex with kainate. Nature. 1998;395:913–917. doi: 10.1038/27692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G-Q, Sun Y, Jin R, Gouaux E. Probing the ligand binding domain of the GluR2 receptor by proteolysis and deletion mutagenesis defines domain boundaries and yields a crystallizable construct. Protein Sci. 1998;7:2623–2630. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560071216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuusinen A, Arvola M, Keinänen K. Molecular dissection of the agonist binding site of an AMPA receptor. EMBO J. 1995;14:6327–6332. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees GJ. Pharmacology of AMPA/Kainate receptor ligands and their therapeutic potential in neurological and psychiatric disorders. Drugs. 2000;59:33–78. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden DR. The structure and function of glutamate receptor ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:91–101. doi: 10.1038/nrn725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi N, Shneider NA, Axel R. A family of glutamate receptor genes: Evidence for the formation of heteromultimeric receptors with distinct channel properties. Neuron. 1990;5:569–581. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90212-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paas Y. The macro-and microarchitectures of the ligand-binding domain of glutamate receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:117–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern-Bach Y, Bettler B, Hartley M, Sheppard PO, O'Hara PJ, Heinemann SF. Agonist selectivity of glutamate receptors is specified by two domains structurally related to bacterial amino acid-binding proteins. Neuron. 1994;13:1345–1357. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern-Bach Y, Russo S, Neuman M, Rosenmund C. A point mutation in the glutamate binding site blocks desensitization of AMPA receptors. Neuron. 1998;21:907–918. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Olson RA, Horning M, Armstrong N, Mayer ML, Gouaux E. Mechanism of glutamate receptor desensitization. Nature. 2002;417:245–253. doi: 10.1038/417245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]