Abstract

The organization of the fatty acid synthetic genes of Haemophilus influenzae Rd is remarkably similar to that of the paradigm organism, Escherichia coli K-12, except that no homologue of the E. coli fabF gene is present. This finding is unexpected, since fabF is very widely distributed among bacteria and is thought to be the generic 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) synthase active on long-chain-length substrates. However, H. influenzae Rd contains a homologue of the E. coli fabB gene, which encodes a 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthase required for unsaturated fatty acid synthesis, and it seemed possible that the H. influenzae FabB homologue might have acquired the functions of FabF. E. coli mutants lacking fabF function are unable to regulate the compositions of membrane phospholipids in response to growth temperature. We report in vivo evidence that the enzyme encoded by the H. influenzae fabB gene has properties essentially identical to those of E. coli FabB and lacks FabF activity. Therefore, H. influenzae grows without FabF function. Moreover, as predicted from studies of the E. coli fabF mutants, H. influenzae is unable to change the fatty acid compositions of its membrane phospholipids with growth temperature. We also demonstrate that the fabB gene of Vibrio cholerae El Tor N16961 does not contain a frameshift mutation as was previously reported.

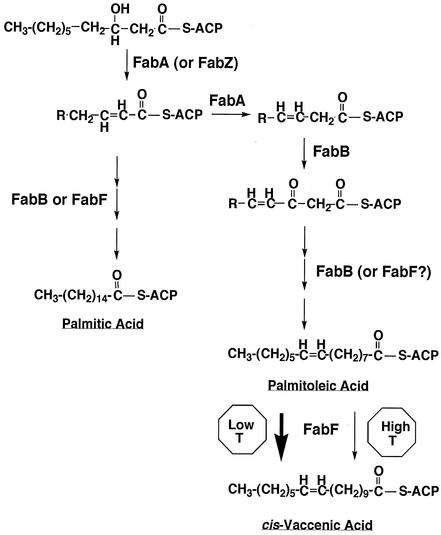

The fatty acid synthetic pathway of Escherichia coli has provided a very successful model for fatty acid synthesis in bacteria and plant chloroplasts (13, 38). Indeed, not only are the sequences of the E. coli fatty acid synthetic proteins highly conserved in other bacteria, but surprisingly, in many cases the arrangements of the genes encoding the synthetic enzymes are also conserved. As discussed elsewhere (7), the major exception to the E. coli paradigm is in the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. In E. coli, synthesis of the normal fatty acid content requires three enzymes, the products of the fabA, fabB, and fabF genes. FabA is the key enzyme of the classic anaerobic pathway of unsaturated fatty acid synthesis (2) and introduces the cis (or Z) double bond into a 10-carbon intermediate (Fig. 1). This intermediate is then elongated by FabB and FabF to form the unsaturated fatty acids found in the membrane phospholipids (14, 15, 18) and (at low growth temperatures) in lipid A (9). FabB and FabF are 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) synthase (KAS) enzymes (often referred to as condensing enzymes) that catalyze fatty acid chain elongation by the addition of two-carbon units originally derived from acetyl coenzyme A until the ACP-bound chains become 12, 14, 16, or 18 carbons in length and are then substrates for incorporation into complex lipids (11). The fabB gene is defined by a class of mutants defective in unsaturated fatty acid synthesis and encodes 3-KAS I (KAS I) (12, 18, 19). The E. coli fabF gene encoding synthase II (KAS II) was found to be defective in a class of mutants defective in the elongation of palmitoleic acid (cis-9-hexadecenoic acid) to cis-vaccenic acid (cis-11-octadecenoic acid), a phenotype expected for a defect in chain elongation (i.e., KAS) activity (18-20). Therefore, FabB and FabF have distinct and nonoverlapping roles in E. coli unsaturated fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 1). FabB is thought to elongate the product of the FabA gene to the C12 unsaturated intermediate, whereas FabF is required to convert the C16 unsaturated species to the C18 species, which is the key reaction in the thermal adaptation response of E. coli lipids (18-20). Strains of E. coli having deletions of either the fabB or fabF gene synthesize saturated fatty acids normally (15, 18-20), which indicates that either KAS I or KAS II can do all of the elongation reactions of the saturated fatty acid synthetic pathway. These findings suggested that double mutants deficient in both FabB and FabF would be defective in overall long-chain fatty acid synthesis, and this defect has been demonstrated previously (41). Strains carrying null mutations in both fabB and fabF are nonviable; thus, a temperature-sensitive fabB allele was used together with a null allele of fabF.

FIG. 1.

Unsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic pathway of E. coli. The pathway is described in the text.

Consistent with the above picture, the fabA and fabB genes show covariance within organisms; fabB genes are found only in genomes that contain fabA (7). Indeed, in the genomes of the alpha-proteobacteria and pseudomonads, fabA and fabB are adjacent genes and are probably cotranscribed (which has been demonstrated for Pseudomonas aeruginosa [26]). Thus far, the fabA and fabB genes are restricted to the alpha- and gamma-proteobacteria, and it remains a mystery how most other organisms capable of anaerobic growth (e.g., clostridia) make unsaturated fatty acids. In contrast, FabF homologues are found throughout the bacteria and are considered the generic KAS of long-chain fatty acid synthesis (7, 23, 31). However, members of the Pasteurellaceae of gamma-proteobacteria lack a FabF homologue recognizable by sequence alignments. Indeed, each of the complete genomes of Haemophilus influenzae (17) and Pasteurella multocida (29) contains only a single FabB/FabF homologue that appears to be a FabB protein (the sequences are 74% identical with that of E. coli FabB versus 38% with E. coli FabF). Moreover, no FabF homologues have yet been found in the incomplete genome sequences of other Pasteurellaceae: Haemophilus ducreyi, Haemophilus somnus, Mannheimia haemolytica, and three serovars of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. All of these organisms have fabA genes, which together with sequence alignments argues that the FabB/FabF homologue is a FabB protein. Do the Pasteurellaceae FabB proteins also do the job of FabF in these organisms, or is KAS II activity simply not required? The unique function that FabF plays in E. coli is its role in the thermal regulation of fatty acid composition (14, 16). E. coli cultures grown at low temperatures have considerably more unsaturated fatty acids than cultures grown at higher temperatures. E. coli strains with fabF null mutations are viable, although these strains are unable to regulate their unsaturated fatty acid contents upon shifts in growth temperature (28, 37). Therefore, thermal regulation of fatty acid composition plays a growth optimization function in free-living bacteria. However, the Pasteurellaceae grow only in commensal association with warm-blooded animals and are locked into this ecological niche by their inability to synthesize several essential metabolites. Therefore, it seems possible that these organisms have dispensed with the thermal regulation of fatty acid composition.

However, the situation is not straightforward since other bacteria commensal with warm-blooded animals (e.g., Helicobacter pylori and Neisseria meningitidis) contain fabF genes. Moreover, the sequence distinctions between genes encoding FabB versus those encoding FabF are based only on gross alignments, not on the conservation (or lack of conservation) of residues known to be responsible for the differing substrate specificities that the E. coli enzymes display in vivo. Indeed, despite the fact that we have high-resolution-X-ray crystal structures of both the E. coli FabB and FabF proteins, the structural basis of the differing specificities of the two enzymes remains unclear (27, 31, 32, 34, 35). Therefore, it may be possible for a FabB protein to gain the specificity of FabF by undergoing only a few mutational alterations. In H. influenzae and P. multocida, this seemed a distinct possibility since the FabB proteins of these organisms showed somewhat more divergence from their E. coli homologue than did their covariant FabA partners. The FabBs of Pasteurellaceae were 74% identical to those of E. coli, whereas the FabAs were 80 to 83% identical. Finally, there are KAS-encoding sequences present in other bacteria that are difficult to label as either FabBs or FabFs (7), suggesting that proteins that perform the functions of both FabB and FabF may exist.

For these reasons, we believed that direct analyses were needed to test the inferences of genomic analyses. In this paper, we report the expression of the H. influenzae FabB protein in E. coli, having found that the in vivo properties of this protein are indistinguishable from those of E. coli FabB and distinct from those of E. coli FabF. Therefore, it is clear that H. influenzae lacks a protein having FabF activity. As expected from the E. coli paradigm, H. influenzae was shown to be deficient in the temperature adaptation of its membrane phospholipids in comparison to E. coli. We have also reexamined the report (24) that Vibrio cholerae has a frameshift in fabB, which by analogy with E. coli FabB should result in an inactive protein since the active site would be destroyed. Upon assembly and expression of the gene in E. coli, we found that the encoded protein is fully functional and show that the prior conclusion was due to a sequencing error.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth media.

The E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Luria-Bertani medium (30) was used as the rich medium for E. coli growth. The phenotypes of fab strains were assessed on rich broth (RB) medium (41). Oleate neutralized with KOH was added to RB medium at a final concentration of 0.1% and solubilized by the addition of Brij 58 detergent to a final concentration of 0.1 to 0.2%. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (in milligrams per liter): 100 for sodium ampicillin, 30 for chloramphenicol, 30 for kanamycin sulfate, and 25 for tetracycline-HCl. Strains HW1, HW2, and HW3 were constructed by transduction of strains K1060(pHW1), K1060(pHW2), and CY1049, respectively, with a P1vir phage lysate grown on strain MR52 with selection for kanamycin resistance. H. influenzae Rd strain KW20 (ATCC 51907) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Sourcea or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | F′φ80ΔlacZΔM15/Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 | Laboratory collection |

| CY244 | fabB15(Ts) fabF | 41 |

| JWC275 | fabB15(Ts) fabF::kan | 8 |

| CY242 | fabB15(Ts) | 8, 41 |

| K1060 | fabB5 | 39 |

| CY1049 | K1060 harboring pCY304, which is pACYC184 carrying E. coli fabB | Laboratory collection |

| MR52 | Kmr | 28 |

| MG1655 | Wild type | Laboratory collection |

| HW2 | Transductant of K1060(pHW2) with P1 grown on MR52 | This work |

| HW1 | Transductant of K1060(pHW1) with P1 grown on MR52 | This work |

| HW3 | Transductant of CY1049 with P1 grown on MR52 | This work |

| YYC1273 | cfa::kan of MG1655 | 10 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGHIS94 | Apr, fragment from bp 1604860 to 1607247 of H. influenzae KW20 genomic DNA cloned into SmaI site of pUC18, containing grx and fabB | ATCC |

| pHSG576 | Cmr, cloning vector, low-copy-number plasmid | 40 |

| pSU19 | Cmr, medium-copy-number cloning vector | 1 |

| pSU21 | Cmr, medium-copy-number cloning vector | 1 |

| pCY9 | Apr, E. coli fabB in ClaI-SalI sites of pBR322 | Laboratory collection |

| pCR2.1 | Apr Kmr, cloning vector | Invitrogen |

| pHW1 | Cmr, H. influenzae fabB, medium copy number | This work |

| PHW2 | Cmr, H. influenzae fabB, low copy number | This work |

| pHW4 | Cmr, complete V. cholerae fabB gene in fragment from bp 2265331 to 2268914 of V. cholerae El Tor N16961, genomic DNA inserted into pHSG576 | This work |

| pGVCCX51 | V. cholerae El Tor N16961 genomic DNA fragment from bp 2267058 to 2268914 in the pUC18 SmaI site | ATCC |

| pGVCER86 | V. cholerae El Tor N16961 genomic DNA fragment from bp 2265331 to 2267182 in the pUC18 SmaI site | ATCC |

ATCC denotes the American Type Culture Collection.

Genetic and recombinant DNA techniques.

Phage P1 transduction was done according to the method of Miller (30). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and Taq polymerase were obtained from Invitrogen and New England Biolabs. All enzymatic reactions were carried out according to the manufacturers' specifications. Plasmid DNA was purified by using a Plasmid Mini Kit from QIAGEN. Plasmids were introduced by CaCl2-mediated transformation. DNA sequencing and the synthesis of oligonucleotides were done at the University of Illinois Keck Center.

Function of V. cholerae fabB in E. coli.

Two plasmids, pCCX51 and pCER86, which contain overlapping fragments of the fabB gene of V. cholerae, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (no clone containing the complete gene was available). We assembled an intact fabB gene from the fragments by using a ClaI site within the fabB sequence that was common to the two gene fragments. Since this ClaI site overlaps a Dam methylation site, plasmid DNA was prepared from strain CY487, which lacks the Dam methylase. The BamHI-ClaI fragment from pCER86 was inserted into pSU21 (1) digested with both enzymes to give pWY11. The EcoRI-HindIII fabB fragment in pWY11 was then inserted into pUC18 digested with both enzymes to give pUWY11. The EcoRI-HindIII fragment of pUWY11 was then cloned between the same sites of pHSG576 (40) to give pH 6W12. A HindIII fragment of p34S-Km encoding a kanamycin resistance determinant was then ligated to HindIII-digested pH 6W12, and the ligation mixture was transformed into strain CY487 (to obtain DNA lacking Dam modification), which resulted in pH 6W12-Km. The HindIII-ClaI fragment of pH 6W12-Km was replaced with the HindIII-ClaI fragment from pCCX51 to give plasmid pHW4, which carries the intact V. cholerae fabB. Plasmid pHW4 was transformed into E. coli fabB(Ts) or fabB(Ts) fabF mutant strains, and the growth of these transformants was scored on RB and RB-oleate plates. Although fabB was oriented such that it could be transcribed from the vector lac promoter, the lac promoter was not induced and the copy number of the plasmid is such that effective titration of the cellular supply of LacI should not occur. Hence, it seems likely that transcription largely originated in the V. cholerae sequences upstream of the coding region.

Phospholipid fatty acid compositions.

The cultures were grown aerobically at 37°C in RB medium overnight. Cultures (10 ml) were harvested and washed three times with RB at room temperature. The phospholipids were extracted for 1 h with 6 ml of chloroform-methanol at 2:1 (vol/vol). Then the supernatant was added to 2 ml of water and 2 ml of chloroform, and the solution was mixed and centrifuged. The top aqueous phase was removed, and an equal volume of 2 M KCl was added, followed by mixing and centrifugation. The top phase was removed, and an equal volume of water was added, followed by mixing and centrifugation. The resulting top phase was removed, and the bottom organic phase was dried under a stream of nitrogen in a fume hood. Collision-induced dissociation electrospray mass spectrometry (CID ES-MS) was performed on a VG Quattro instrument by using the negative ion mode. Samples were dissolved in chloroform-methanol at a dilution of 1/2 (vol/vol). MS results were acquired with a cone voltage of 50 V over the m/z range of 650 to 800 in 1 s. In-source collusion-induced dissociation was achieved by increasing the cone voltage to 150 V, with the quadrupole being scanned from 100 to 400 mass units in 1 s. The values for any cyclopropane fatty acids present were added to the values for the unsaturated species from which they were derived (20).

For analysis of radioactive fatty acids, cultures were grown overnight in the presence of 5 μCi of sodium [1-14C]acetate (52 mCi/mmol; American Radiolabeled Chemicals) per ml. The medium used for H. influenzae Rd was brain heart infusion medium (BHI medium; Difco) supplemented with NADH and hemin. Both untreated and lipid-depleted BHI media were used, with equivalent results. RB medium was used for E. coli K-12. The phospholipids were extracted as described above. The acyl chains were then converted to their methyl esters, which were separated by argentation thin-layer chromatography and autoradiography (20, 41).

Nucleotide sequence accession number. The corrected DNA sequence determined by this study has been communicated to GenBank (accession no. AY290864) and TIGR.

RESULTS

Fatty acid composition of H. influenzae.

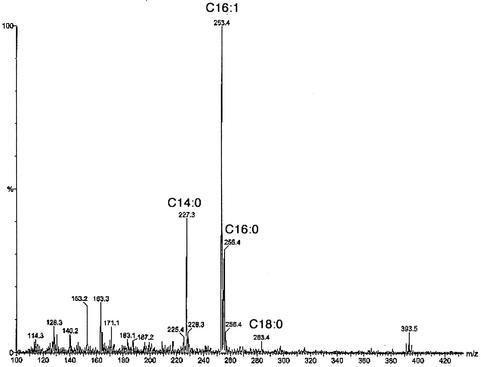

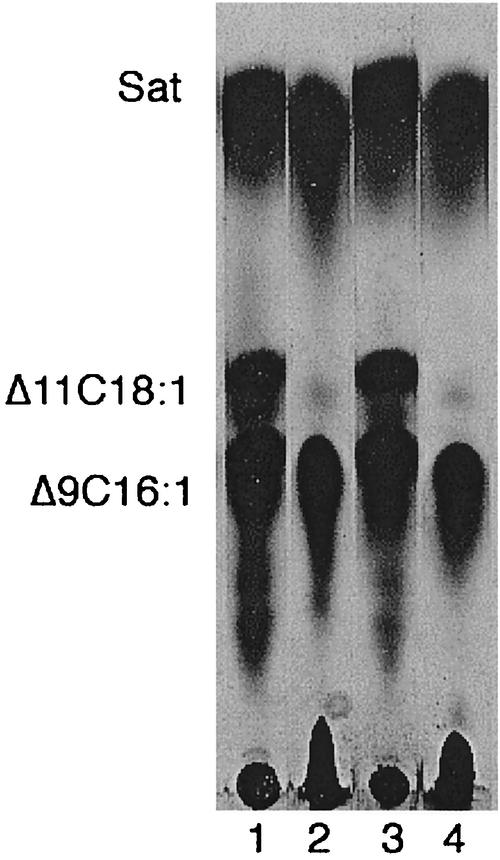

To our knowledge, no fatty acid composition has previously been published for any H. influenzae strain; therefore, we have determined the composition of the chloroform-methanol-extractable lipids of strain Rd KW20 (the strain of known genome sequence) of this organism. The primary method used was CID ES-MS, which gave a very simple fatty acid composition (Fig. 2): 23% tetradecanoic acid (C14:0, myristic acid); 17% hexadecanoic acid (C16:0, palmitic acid); and 55% monounsaturated hexadecenoic acid (C16:1, probably cis-9-hexadecenoic or palmitoleic acid from the E. coli paradigm) with a small amount (5%) of octadecanoic acid (C18:0, stearic acid) and only traces of a monounsaturated octadecenoic acid, which is cis-11-octadecenoic (cis-vaccenic) acid (see below). Fragments of higher mass (data not shown) indicate that the major phospholipids of the organism are phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylglycerol, as was expected from the genomic sequence (17) and analysis of Haemophilus parainfluenzae (42). However, a concern was that the very rich BHI medium generally used for growth of this organism could contain sources of fatty acids that could be incorporated into the lipids of the bacterium. H. influenzae encodes a protein with strong homology to E. coli FadD (acyl coenzyme A synthetase), so it seemed possible that H. influenzae might be able to take up fatty acids from the medium and incorporate them into the membrane phospholipids. However, the lipids of H. influenzae cells grown in BHI medium showed no oleic or linoleic acids, unsaturated fatty acids that are major components of the lipids of the eucaryotic sources from which the medium is derived. Although the lack of oleic and linoleic acids in the bacterial lipids argued against the medium as a source of H. influenzae membrane lipid fatty acids, it remained possible that the putative fatty acid uptake and incorporation proteins of H. influenzae discriminate against these fatty acids (although both acids are readily incorporated by E. coli). Therefore, we prepared a lipid-extracted form of BHI medium by acidification with acetic acid (to decompose any fatty acid salts present) followed by several extractions with chloroform. Residual chloroform and much of the acetic acid were removed by autoclaving. The pH was then adjusted to 7.0 with NaOH. The medium was then supplemented with NAD plus hemin and sterilized by filtration through a 0.25-μm pore-size filter. The lipid-extracted medium supported growth well, and the cells had the same fatty acid composition as cells grown on the standard BHI medium. An independent means to confirm that the fatty acids observed were the products of de novo synthesis rather than incorporation from the medium was provided by biosynthetic incorporation of a radioactive precursor into lipids. H. influenzae was grown on the lipid-extracted BHI medium supplemented with [1-14C]acetate. The lipids were extracted, and the fatty acid moieties were then converted to their methyl esters. The radioactive methyl esters were then separated by argentation thin-layer chromatography by using a fatty acid methyl ester mixture derived from the phospholipids of an E. coli strain defective in cyclopropane fatty acid synthesis (10) as the standard. Argentation chromatography readily discriminates monounsaturated fatty acids on the basis of the double-bond configuration and position relative to the ester function (22, 33). The thin-layer plates were autoradiographed (Fig. 3) and showed fatty acid components that were consistent with those of the mass spectroscopic analyses. Moreover, since the unsaturated fatty acids were cochromatographed with those of E. coli, the unsaturated fatty acids were identified as palmitoleic (cis-9-hexadecenoic) and cis-vaccenic (cis-11-octadecenoic) acids.

FIG. 2.

CID ES mass spectrum of H. influenzae Rd strain KW20 phospholipid fatty acids. The spectrum was obtained from the phospholipids of cells grown on lipid-depleted BHI medium. The masses and identifications of the peaks are given at the apexes. C14:0 indicates a 14-carbon fatty acid lacking double bonds, whereas C16:1 indicates a 16-carbon fatty acid with one double bond.

FIG. 3.

Argentation thin-layer chromatographic analysis of [1-14C]acetate-labeled H. influenzae Rd strain KW20 fatty acid methyl esters. An autoradiogram is shown. The methyl esters were obtained as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 1 and 3 are methyl esters from the phospholipids of E. coli strain YYC1273, which is defective in cyclopropane fatty acid synthesis. Lanes 2 and 4 are methyl esters from the phospholipids of H. influenzae Rd strain KW20. Sat, saturated fatty acids; Δ11C18:1, cis-vaccenic acid; Δ9C16:1, palmitoleic acid. The autoradiogram was overexposed in order to detect the traces of cis-vaccenic acid synthesized by H. influenzae.

Putative H. influenzae fabB complements E. coli fabB mutants.

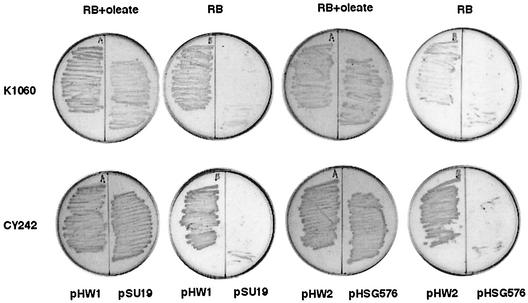

The fatty acid composition data suggested that the putative H. influenzae fabB encodes a protein with properties very similar to those of E. coli FabB. That is, the H. influenzae enzyme should catalyze a key step in unsaturated fatty acid synthesis but has little or no ability to catalyze elongation of cis-9-hexadecenoyl-ACP. The H. influenzae fabB gene was cloned into two vectors, pHSG576, which has the replication origin of pSC101 and thus a low copy number (1 to 5 copies/cell), and pSU19, a p15a origin plasmid (∼15 copies/cell), to give plasmids pHW2 and pHW1, respectively. Although in both plasmids fabB was oriented such that it could be transcribed from the vector lac promoter, we did not induce the lac promoter, and the copy numbers of these plasmids are too low to effectively titrate the cellular supply of LacI. Hence, it seems likely that transcription largely originated in the H. influenzae sequences upstream of the coding region. These plasmids were then introduced into several E. coli fabB strains by transformation. The fabB mutations tested included two point mutant strains, one of which gives temperature-sensitive growth. All of the resulting transformants grew in the absence of unsaturated fatty acid supplementation, and growth was identical to that given by introduction of pCY9, a plasmid carrying the E. coli fabB gene (Fig. 4). The plasmids were then introduced into a fabB(Ts) fabF strain and plated on medium containing the unsaturated fatty acid oleate at the nonpermissive temperature and subsequently tested on media containing or lacking oleate at 42°C. Growth at 42°C in the presence of oleate indicates complementation of the fabF mutation, whereas growth in the absence of oleate indicates complementation of the fabB mutation. The transformants grew at 42°C in the presence or absence of oleate (data not shown); thus, only the fabB mutation had been complemented. However, it remained possible that the putative H. influenzae Rd FabB protein could replace the functions of both E. coli genes. If so, this replacement would be reflected only in the fatty acid compositions of the complemented strains (41). If the H. influenzae protein possessed FabF activity in addition to FabB activity, then high levels of cis-vaccenate would be synthesized. Low levels of cis-vaccenate would indicate that only the fabB mutation was complemented (41).

FIG. 4.

Growth of transformants of E. coli strains K1060 and CY242 with plasmids carrying H. influenzae Rd strain KW20 fabB. Transformants of strain K1060 (an unconditional fabB mutant) were grown at 37°C, whereas the transformants of strain CY242 (a temperature-sensitive fabB mutant) were grown at 42°C, the nonpermissive temperature. Both plasmids carry the H. influenzae fabB gene. Plasmid pHW1 is derived from the medium-copy-number vector pSU19, whereas pHW2 is derived from the low-copy-number vector pHSG576. RB plus oleate is the permissive medium, whereas fabB strains fail to grow on unsupplemented RB medium.

The fatty acid compositions of fabB(Ts) fabF E. coli strains carrying various FabB-containing plasmids were determined by CID ES-MS (Fig. 5). The complemented strains clearly synthesized unsaturated fatty acids when they were grown at 42°C, the nonpermissive temperature (Fig. 5A). Indeed, the level of unsaturated fatty acid synthesis was similar to that seen upon introduction of a plasmid that encoded E. coli FabB (Fig. 5A). Moreover, despite the differing copy numbers, the two plasmids encoding H. influenzae Rd FabB gave similar levels of unsaturated fatty acids (Fig. 5B). Similar results were seen in another fabB(Ts) fabF strain, strain JWC275 (data not shown). Since expression of H. influenzae FabB from these plasmids did not give the large increase in cis-vaccenate expected of FabF function, it seemed that this KAS enzyme did not possess the ability to perform the function of FabF as well as that of FabB.

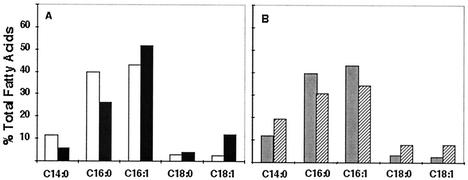

FIG. 5.

Fatty acid compositions of a fabB(Ts) fabF strain transformed with various fabB plasmids. (A) Strain CY244 [fabB(Ts) fabF] was transformed with plasmid pHW1 (open bars) carrying H. influenzae fabB or with plasmid pCY9 carrying E. coli fabB (filled bars). Both plasmids had a medium copy number. (B) Strain CY244 was transformed with the medium-copy-number plasmid pHW1 (gray bars) or with the low-copy-number H. influenzae fabB plasmid pHW2 (hatched bars). All cultures were grown at 42°C, and the fatty acid compositions were determined by CID ES-MS as described in Materials and Methods.

However, in E. coli, FabF is fully functional only at low growth temperatures, and since FabF function in the temperature-sensitive strains could be tested only at 42°C (where the mutant FabB is inactive), this assay lacked sensitivity. To avoid this complication, we constructed fabB fabF strains with an unconditional fabB mutation (39). Since strains lacking both FabB and FabF activities are nonviable (41), we first introduced plasmids pHW1 and pHW2 into a strain carrying the fabB mutation and then introduced a fabF null mutation by transduction with phage P1. These recombinant strains (called HW1 and HW2, respectively) grew well over a wide temperature range, which allowed us to more definitively test H. influenzae FabB for FabF function. The two strains showed no marked increase in cis-vaccenate synthesis with decreased growth temperatures (Fig. 6). Although the strain carrying the plasmid with the higher copy number (Fig. 6A) showed a modest increase in cis-vaccenate when it was grown at lower temperatures, the total cis-vaccenate content was fourfold lower than that seen in a wild-type E. coli strain. Moreover, the strain carrying the lower-copy-number H. influenzae fabB plasmid had the opposite behavior: the level of cis-vaccenate decreased with decreased growth temperature (Fig. 6B).

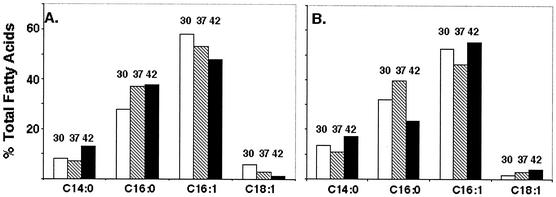

FIG. 6.

Effects of growth temperature on a fabB fabF strain carrying plasmids encoding H. influenzae FabB. A fabF null mutation was introduced by transduction into strain K1060 (fabB) carrying either the medium-copy-number plasmid pHW1 (A) or the low-copy-number plasmid pHW2 (B). The numbers above the bars indicate the growth temperature (30, 37, or 42°C). The fatty acid compositions were determined by CID ES-MS as described in Materials and Methods.

H. influenzae Rd is unable to thermally control membrane lipid composition.

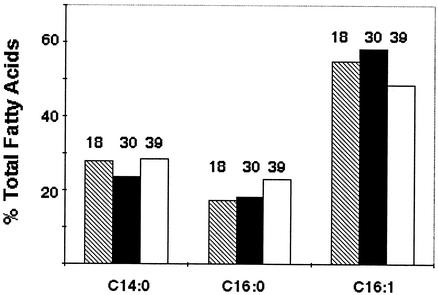

The data we obtained by expression of the H. influenzae fabB gene in mutant strains of E. coli indicated that the activity of the H. influenzae enzyme did not respond to temperature as does E. coli FabF (16, 18). Since the genomic data argued that this was the sole gene encoding a long-chain 3-KAS in H. influenzae, it seemed likely that H. influenzae might lack the ability to regulate its fatty acid composition with growth temperature. To test this hypothesis, we grew H. influenzae Rd strain KW20 at various temperatures. The range of temperatures over which the organism grew in the lipid-depleted medium was surprisingly broad, given its ecological niche. The extreme temperatures examined were 18 and 39°C. The organism failed to grow at 42°C, and temperatures below 18°C were not tested. Cells were isolated from cultures grown for at least five generations at a given temperature. The lipids were extracted and analyzed by CID ES-MS, and the fatty acid compositions did not significantly vary with temperature (Fig. 7). These results indicate that H. influenzae Rd lacks the ability to change its fatty acid composition with temperature.

FIG. 7.

Fatty acid compositions of H. influenzae cultures grown at different temperatures. Cultures were grown to saturation in the lipid-depleted BHI medium (Materials and Methods). The cellular phospholipids were then extracted and analyzed by CID ES-MS as described in Materials and Methods.

V. cholerae possesses a fully functional fabB gene.

The V. cholerae El Tor N16961 genome sequence (24) indicates that the fabB gene of this organism contains an authentic frameshift that blocks synthesis of the last third of the protein. If true, V. cholerae should be unable to make unsaturated fatty acids since the protein would lack both of the histidine residues of the His-His-Cys catalytic triad (34-36). We suspected that the reported frameshift was the result of sequencing errors for the following reasons. First, it seemed unlikely that V. cholerae could survive as an unsaturated fatty acid auxotroph in its native environment, the waters of marine estuaries. Second, a reading frame downstream of the putative frameshift could be translated into a protein segment more than 70% identical to that of the last third of E. coli FabB. If the gene had truly undergone a frameshift, there would have been no selection to preserve this amino acid sequence over the time elapsed since the divergence of V. cholerae and E. coli. Therefore, we assembled a full-length gene from the plasmid carrying the appropriate sequenced gene segments that had been deposited in the American Type Culture Collection. The assembled gene was then expressed in each of the E. coli fabB and fabB fabF strains in Table 1. All transformed strains grew readily under nonpermissive conditions in the absence of oleate; thus, the V. cholerae gene functionally complemented the E. coli fabB mutations (data not shown). Moreover, the fatty acid compositions of the complemented E. coli strains showed high levels of unsaturated fatty acids as determined by CID ES-MS (data not shown). Finally, to test the possibility that the gene with the frameshift somehow retained activity, we intentionally truncated the reconstructed gene by inserting a gene cassette encoding kanamycin resistance into the unique BssHII site located close to and downstream of the reported frameshift. This resulted in disruption of the coding sequence starting 30 bp downstream of the putative frameshift. This disruption construct was transformed into several E. coli fabB mutant strains and was found to completely lack complementation activity (data not shown). Finally, we sequenced both strands of the assembled full-length gene. We found that our construct has a G at base 711 of the open reading frame that is missing from the published TIGR genome sequence. Thus, in our sequence the deduced sequence of residues 231 to 240 of V. cholerae FabB is GGGGMVVVEE, a sequence identical to that found in E. coli FabB, whereas the sequence from TIGR gives the sequence GGGGMVVLKS for this segment of the protein.

DISCUSSION

The H. influenzae Rd fabB gene encodes a protein that fully complements several E. coli fabB mutant strains, but the protein is unable to complement the fabF mutation of a fabB fabF strain. Upon expression of H. influenzae FabB in E. coli fabB fabF strains, no increase in cis-vaccenate content is observed at the nonpermissive temperature, showing that H. influenzae FabB does not have the properties of FabF. Therefore, the straightforward prediction from study of the genome is confirmed: H. influenzae Rd has indeed dispensed with the generic long-chain 3-KAS and retained the specialized enzyme. The result of the loss of FabF function is that H influenzae Rd is completely defective in the thermal regulation of the fatty acid composition of its membrane phospholipids and almost totally lacks cis-vaccenate. Therefore, relative to E. coli, H. influenzae Rd is a natural fabF mutant. The loss of this regulatory mechanism seems likely to be due to the lack of environmental selection, since H. influenzae exists in nature only in extremely close association with warm-blooded animals. This loss also seems likely to be the case in the other species of the family Pasteurellacae, since sequences encoding FabB but not FabF are found in these genomes and the sole unsaturated fatty acid reported in these cells is palmitoleic acid (3-6, 42). Indeed, species within the Pasteurellaceae cannot be distinguished by their fatty acid compositions (6). Except for fabF, the genes required for fatty acid synthesis in E. coli are completely conserved in the completed genomes available for Pasteurellaceae (H. influenzae Rd and P. multocida PM70). Indeed, even the fadR regulatory gene required for full expression of fabA and fabB in E. coli (8, 25) is conserved in these genomes, whereas the alpha-proteobacteria and pseudomonads lack a FadR homologue. The arrangements of the genes within the H. influenzae and P. multocida fab gene clusters, which encode most of the fatty acid synthetic proteins, are extremely similar to those found in E. coli. The order of the genes, fabH fabD fabG acpP, is the same as that seen in E. coli, but rather than finding a fabF gene downstream of acpP as in E. coli, H. influenzae and P. multocida have a gene encoding a putative membrane transporter. Therefore, it seems that fabF was deleted from the genomes of the Pasteurellaceae during the shrinking of the ancestral genome that accompanied adoption of a commensal lifestyle (E. coli and H. influenzae are thought to have diverged about 680 million years ago). It should be noted that the Pasteurellaceae also lack a second highly conserved gene of lipid synthesis, the cfa gene that encodes the enzyme catalyzing cyclopropane fatty acid synthesis (21). None of the genomic sequences available for this group of organisms contains a cfa gene homologue, and our lipid analyses (Fig. 2) as well as those available in the literature (3-6, 42) show that no cyclopropane fatty acids are present. The synthesis of cyclopropane fatty acids is thought to protect cells from environmental stresses and has been shown to allow E. coli to better survive shifts to low-pH environments (10). Therefore, the Pasteurellaceae lack two distinct mechanisms used by organisms to adapt their membrane lipids to environmental changes, indicating that the constant environment of the commensal lifestyle of these organisms has removed the necessity to select for retention (or reacquisition) of the fabF and cfa genes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI15650.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartolome, B., Y. Jubete, E. Martinez, and F. de la Cruz. 1991. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derived cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene 102:75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloch, K. 1963. The biological synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 24:1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boot, R., H. C. Thuis, and F. A. Reubsaet. 1999. Growth medium affects the cellular fatty acid composition of Pasteurellaceae. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 289:9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brondz, I., and I. Olsen. 1986. Chemotaxonomy of selected species of the Actinobacillus-Haemophilus-Pasteurella group by means of gas chromatography, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and bioenzymatic methods. J. Chromatogr. 380:1-17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brondz, I., and I. Olsen. 1992. Intra-injector methylation of free fatty acids from aerobically and anaerobically cultured Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Haemophilus aphrophilus. J. Chromatogr. 576:328-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brondz, I., I. Olsen, and M. Sjostrom. 1990. Multivariate analysis of quantitative chemical and enzymic characterization data in classification of Actinobacillus, Haemophilus and Pasteurella spp. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136:507-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell, J. W., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 2001. Bacterial fatty acid biosynthesis: targets for antibacterial drug discovery. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:305-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell, J. W., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 2001. Escherichia coli FadR positively regulates transcription of the fabB fatty acid biosynthetic gene. J. Bacteriol. 183:5982-5990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carty, S. M., K. R. Sreekumar, and C. R. H. Raetz. 1999. Effect of cold shock on lipid A biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Induction at 12°C of an acyltransferase specific for palmitoleoyl-acyl carrier protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274:9677-9685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, Y. Y., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1999. Membrane cyclopropane fatty acid content is a major factor in acid resistance of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33:249-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cronan, J. E., Jr., and C. O. Rock. 1996. Biosynthesis of membrane lipids, p. 612-636. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 12.Cronan, J. E., Jr., C. H. Birge, and P. R. Vagelos. 1969. Evidence for two genes specifically involved in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 100:601-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cronan, J. E., Jr., and G. L. Waldrop. 2002. Multi-subunit acetyl-CoA carboxylases. Prog. Lipid Res. 41:407-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Mendoza, D., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1983. Temperature regulation of membrane fluidity in bacteria. Trends Biochem. Sci. 8:49-52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Mendoza, D., A. Klages Ulrich, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1983. Thermal regulation of membrane fluidity in Escherichia coli. Effects of overproduction of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I. J. Biol. Chem. 258:2098-2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards, P., J. S. Nelsen, J. G. Metz, and K. Dehesh. 1997. Cloning of the fabF gene in an expression vector and in vitro characterization of recombinant fabF and fabB encoded enzymes from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 402:62-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. F. Kirkness, A. R. Kerlavage, C. J. Bult, J. F. Tomb, B. A. Dougherty, J. M. Merrick, et al. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269:496-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garwin, J. L., A. L. Klages, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1980. β-Ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II of Escherichia coli. Evidence for function in the thermal regulation of fatty acid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 255:3263-3265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garwin, J. L., A. L. Klages, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1980. Structural, enzymatic, and genetic studies of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases I and II of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 255:11949-11956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelmann, E. P., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1972. Mutant of Escherichia coli deficient in the synthesis of cis-vaccenic acid. J. Bacteriol. 112:381-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grogan, D. W., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1997. Cyclopropane ring formation in membrane lipids of bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:429-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunstone, F. D., I. A. Ismail, and M. Lie Ken jie. 1967. Fatty acids, part 16. Thin layer and gas-liquid chromatographic properties of the cis and trans methyl octadecenoates and of some acetylenic esters. Chem. Phys. Lipids 1:376-385. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heath, R. J., and C. O. Rock. 2002. The Claisen condensation in biology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 19:581-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heidelberg, J. F., J. A. Eisen, W. C. Nelson, R. A. Clayton, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, L. Umayam, S. R. Gill, K. E. Nelson, T. D. Read, H. Tettelin, D. Richardson, M. D. Ermolaeva, J. Vamathevan, S. Bass, H. Qin, I. Dragoi, P. Sellers, L. McDonald, T. Utterback, R. D. Fleishmann, W. C. Nierman, and O. White. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henry, M. F., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1992. A new mechanism of transcriptional regulation: release of an activator triggered by small molecule binding. Cell 70:671-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoang, T. T., and H. P. Schweizer. 1997. Fatty acid biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: cloning and characterization of the fabAB operon encoding β-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein dehydratase (FabA) and β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I (FabB). J. Bacteriol. 179:5326-5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, W., J. Jia, P. Edwards, K. Dehesh, G. Schneider, and Y. Lindqvist. 1998. Crystal structure of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II from E. coli reveals the molecular architecture of condensing enzymes. EMBO J. 17:1183-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnuson, K., M. R. Carey, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1995. The putative fabJ gene of Escherichia coli fatty acid synthesis is the fabF gene. J. Bacteriol. 177:3593-3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.May, B. J., Q. Zhang, L. L. Li, M. L. Paustian, T. S. Whittam, and V. Kapur. 2001. Complete genomic sequence of Pasteurella multocida, Pm70. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:3460-3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Moche, M., K. Dehesh, P. Edwards, and Y. Lindqvist. 2001. The crystal structure of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase II from Synechocystis sp. at 1.54 Å resolution and its relationship to other condensing enzymes. J. Mol. Biol 305:491-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moche, M., G. Schneider, P. Edwards, K. Dehesh, and Y. Lindqvist. 1999. Structure of the complex between the antibiotic cerulenin and its target, β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 274:6031-6034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris, L. J., D. M. Wharry, and E. W. Hammond. 1967. Chromatographic behavior of isomeric long-chain aliphatic compounds. II. Argentation thin layer chromatography of isomeric octadecenoates. J. Chromatogr. 31:69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsen, J. G., A. Kadziola, P. von Wettstein-Knowles, M. Siggaard-Andersen, and S. Larsen. 2001. Structures of β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase I complexed with fatty acids elucidate its catalytic machinery. Structure (Cambridge) 9:233-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsen, J. G., A. Kadziola, P. von Wettstein-Knowles, M. Siggaard-Andersen, Y. Lindquist, and S. Larsen. 1999. The X-ray crystal structure of β-ketoacyl [acyl carrier protein] synthase I. FEBS Lett. 460:46-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price, A. C., Y.-M. Zhang, C. O. Rock, and S. W. White. 2001. Structure of β-ketoacyl-[acyl carrier protein] reductase from Escherichia coli: negative cooperativity and its structural basis. Biochemistry 40:12772-12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rawlings, M., and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1992. The gene encoding Escherichia coli acyl carrier protein lies within a cluster of fatty acid biosynthetic genes. J. Biol. Chem. 267:5751-5754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rock, C. O., and J. E. Cronan. 1996. Escherichia coli as a model for the regulation of dissociable (type II) fatty acid biosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1302:1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schairer, H. U., and P. Overath. 1969. Lipids containing trans-unsaturated fatty acids change the temperature characteristic of thiomethylgalactoside accumulation in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol 44:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeshita, S., M. Sato, M. Toba, W. Masahashi, and T. Hashimoto-Gotoh. 1987. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ alpha-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene 61:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ulrich, A. K., D. de Mendoza, J. L. Garwin, and J. E. Cronan, Jr. 1983. Genetic and biochemical analyses of Escherichia coli mutants altered in the temperature-dependent regulation of membrane lipid composition. J. Bacteriol. 154:221-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.White, D. C., and R. H. Cox. 1967. Identification and localization of the fatty acids in Haemophilus parainfluenzae. J. Bacteriol. 93:1079-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]