Abstract

In a previous study, we established that leptin acts on chemosensitive intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors and that its excitatory effects are blocked by the endogenous interleukin-1β receptor antagonist (Il-1ra). To determine how interleukin-1β (Il-1β) is involved in the action of leptin, we studied the effects of this drug on the single vagal afferent activities of intestinal mechanoreceptors in anaesthetized cats. For this purpose, the activity of 34 intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors was recorded via glass microelectrodes implanted in the nodose ganglion. Il-1β (1 μg) administered into the artery irrigating the upper part of the intestine activated both the 16 leptin-activated units (type 1 units; P < 0.01) and the 12 leptin-inhibited units (type 2 units; P < 0.001), but had no effect on the six leptin-insensitive units. Cholecystokinin (CCK, 10 μg) induced an activatory response only in the two types of Il-1β-sensitive units. When Il-1β was administered after CCK, its excitatory effects on type 1 units were enhanced, whereas the excitatory effects on type 2 units were abolished. Pre-treatment with Il-1ra (250 μg) blocked all the effects of Il-1β and the excitatory effects of leptin on type 1 units, whereas it enhanced the inhibitory effects of leptin on type 2 units. It can therefore be concluded that (i) leptin acts on intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors via Il-1β in the case of the type 1 units and independently of Il-1β in the case of the type 2 units, and (ii) type 1 and type 2 units belong to two different populations of vagal afferents that transmit different information about ingestion or inflammation to the CNS, depending on the chemical environment.

Leptin, the product of the ob gene, regulates food intake and energy expenditure through central effects on the hypothalamus. Previous data have indicated that in addition to its direct effects on brain targets via hormonal pathways (Langhans, 2000), leptin can act on hepatic (Shiraishi et al. 1999; Yuan et al. 1999), gastric (Wang et al. 1997, 2000) and intestinal (Gaigéet al. 2002) vagal afferent nerve fibres by sending rapid signals to the central nervous system (CNS) via neuronal pathways. We previously established that leptin affects two kinds of intestinal vagal afferent fibres in different ways: it activates the type 1 fibres and inhibits the type 2 fibres (Gaigéet al. 2002, 2003). Only the excitatory effects of leptin are present in rat stomach vagal afferents, however (Wang et al. 1997). Interactions between CCK and leptin have been observed in the stomach as well as the intestine, which suggests that these afferent fibres play a role in the control of food intake. However, the excitatory effects of leptin on type 1 intestinal units involve Il-1β, since they are blocked by Il-1ra, which indicates that type 1 units might be involved in regulating food intake under pathological conditions (Gaigéet al. 2002). This is consistent with data obtained from rats by Luheshi et al. (1999), showing that the effects of leptin on food intake and body temperature involve Il-1β. Numerous authors have pointed out the existence of a correlation between Il-1β release and the plasmatic leptin levels (Barbier et al. 1998; Faggioni et al. 1998; Arnarlich et al. 1999; Francis et al. 1999). In addition, many published data have suggested that leptin is involved not only in the control of food intake and body weight, but also in immune responses (Bik et al. 2001). Recent studies have shown that leptin enhances cytokine production and phagocytosis by macrophages, thus stimulating the immune system (Loffreda et al. 1998). The results of the other studies have suggested that leptin and Il-1β may co-operatively mediate anorexia during inflammatory processes (Sarraf et al. 1997; Barbier et al. 1998; Francis et al. 1999; Luheshi et al. 1999). It is well known that Il-1β coordinates peripheral immune responses as well as carrying information to the CNS (Dunn, 1993; Maier et al. 1993), which contributes to inducing the general symptoms of illness (fever, hyperalgesia, anorexia, etc.) and activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (Gaykema et al. 1995). Like leptin, Il-1β transmits information to the CNS via at least two pathways (Schwartz, 2002): there is not only a hormonal pathway, but also a neural component, namely the vagus nerves. Many published data are consistent with this hypothesis: peripheral administration of Il-1β induces an increase in the hepatic (Niijima, 1996) and gastric (Kurosawa et al. 1997; Ek et al. 1998) vagal afferent fibre activities. The mRNA corresponding to the Il-1β receptors has been identified in vagal sensory neurones (Ek et al. 1998). In addition, previous studies have shown that Il-1β binds to receptors located on sensory vagal endings and vagal paraganglia closely associated with afferent vagal fibres (Goehler et al. 1997), thus activating afferent vagal fibres (Goehler et al. 1998). It has by now been clearly established that vagus nerves constitute the main pathway whereby Il-1β mediates pathological responses, such as fever (Watkins et al. 1995; Hansen & Krueger, 1997; Gordon, 2000), sleep disturbances (Hansen & Krueger, 1997), hyperalgesia (Watkins et al. 1994) and anorexia (Bret-Dibat et al. 1995).

With a view to elucidating how Il-1β is involved in the effects of leptin, it was proposed here to investigate the effects of this drug on leptin-sensitive intestinal vagal units to determine in particular whether its inhibitory effects on type 2 units may also involve Il-1β. In order to establish whether each type of unit is specifically involved in the transmission of information about either inflammation or ingestion, and whether this information may vary depending on the chemical environment, we also investigated the interactions between leptin and CCK and the interactions between Il-1β and CCK.

Methods

The experimental procedures described here were carried out in accordance with the European guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals (Council Directive 86/6009/EEC) and receive approval from the local ethics committee (Comité Régional d'Ethique pour l'Expérimentation Animale, Provence). These experimental methods were practically the same as those described by Abysique et al. (1999) and Gaigéet al. (2002). Thirty-four adult European cats of either sex weighing 2.7–4.8 kg (mean: 3.4 kg) were used in these acute experiments. The animals had fasted (water ad libitum) for 24 h before undergoing surgery.

Anaesthesia

Anaesthesia was induced by administering a gaseous mixture (2% halothane, 98% air; Bélamont, Neuilly sur-Seine, France). The trachea was cannulated and a catheter was inserted into a radial vein, through which the main anaesthetic (chloralose, 80 mg kg−1, i.v., Sigma, Saint Quentin-Fallavier, France) was administered intravenously. The depth of anaesthesia was monitored by checking that the palpebral reflex was absent and the pupils constricted. In addition, the blood pressure and heart rate were systematically monitored throughout the experiment to detect any changes in the level of anaesthesia. The appropriate depth of anaesthesia was characterized by constricted pupils, stable blood pressure (114.3 ± 8.2 mmHg, n = 34) and heart rate (119 ± 0.7 beats min−1, n = 34), and by the absence of the palpebral reflex. Whenever any of these parameters changed, showing that the anaesthesia was weakening, a flush of chloralose (8 mg kg−1, i.v.) was administered. To prevent the occurrence of any movement artefacts due to electrical stimulation of the nerves, the animals were paralysed by intravenously administering Flaxedil (gallamine triethiodide, 4 mg kg−1, i.v., Sigma, Saint Quentin-Fallavier, France) and ventilated with a respiratory pump. The cats were fixed in a Horsley-Clarke apparatus in the supine position, and their body temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1°C by means of a heating blanket.

In each experiment, the surgical procedure began when the values of the parameters characterizing the appropriate depth of anaesthesia were reached (after approximately 40–60 min). The stabilization time allowed to elapse between the end of the surgery and the start of the tests with the compounds was 2 h.

At the end of each experiment, the cats were killed by administering an overdose of barbiturates (sodium thiopentone, 70 mg kg−1, i.v., Sanofi, Libourne, France).

Electrophysiological recording techniques

The activity of the vagal interoceptors was routinely recorded at the level of the right nodose ganglion (Mei, 1978, 1983; Gaigéet al. 2002), which was reached via a short lateral incision in the neck. The ganglion was then placed on a special metallic plate, designed to prevent any artefacts from occurring as the result of the respiratory and carotid movements. The activity of the vagal afferent units was recorded by means of extracellular glass microelectrodes filled with 3 m KCl solution, as previously described (Mei, 1970). It has been reported that recordings obtained by means of glass electrodes filled with KCl (3 m) are similar to those obtained with glass electrodes filled with NaCl (2 m; Mei, 1968), or with metal electrodes (S. Gaigé, unpublished observations), which clearly indicates that using KCl (3 m) does not affect the discharge pattern of vagal afferent neurones under our experimental conditions. The electrodes were fixed to a micromanipulator (Mei, 1983) by means of a surgical microscope so that they could be implanted exactly into the gastro-intestinal region of the nodose ganglion, which is located in its caudal part (Mei, 1970; Zhuo et al. 1997). Electrodes were made using a vertical glass-stretching apparatus to obtain tips ranging between 1 and 3 μm in diameter with resistances from 2 to 5 MΩ. The discharge patterns of the vagal afferent units were displayed on an oscilloscope (TEKTRONIX, type R564B, Beaverton, OR, USA) and a thermosensitive paper recorder (Astromed, type DASH IV, 78190 Trappes, France). The activity of these units was also recorded on magnetic tape (DTR biologic, 38640 Claix, France) for further data processing. With the amplitude discrimination (WPI, model 121, New Haven, CT, USA) and shape recognition (Mac Laboratory, New Haven, CT, USA) procedures used, it was possible to select the electrical activity of a single afferent fibre, and thus to work under unitary recording conditions. Data were processed by computer in the form of frequency histograms showing the number of action potentials per second (AP s−1). To ensure that the full effects were displayed, the recordings were started 2 min before the injections were administered and lasted for 17 min.

Stimulation techniques

Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve

The right cervical vagus nerve was dissected along 1 cm in the neck, 4–5 cm below the nodose ganglion, and was placed on stimulating electrodes consisting of two platinum wires placed in a Plexiglass gutter. Rectangular stimulation shocks (1 ms in duration and 15–30 V in amplitude) were delivered via a Grass stimulator connected in series to an isolation unit. This electrical stimulation made it possible to monitor all the responses via the recording electrode and to check whether the location of the electrode tip was accurate. This set-up was also used to record the conduction velocity (approximately 1 m s−1) of the unmyelinated vagal fibres.

Mechanical stimulation of the mechanoreceptors

A segment of small intestine including the duodenum and the proximal part of the jejunum was isolated between two cannulas. The more anterior of these, which was connected to a vertically adjustable reservoir containing physiological saline at 37°C, was inserted into the proximal jejunum so that various perfusion pressures could be obtained. The posterior cannula used to empty the intestinal loop was placed 20 cm lower down, and was connected to a pressure transducer (Telco, 94250 Gentilly Seine, France). The isolated intestinal loop was distended by moving the reservoir vertically. With the experimental protocol used here, it is possible to make pressure adjustments ranging between 0 and 100 cmH2O. With distensions of 20 cmH2O, it was possible to selectively activate the intestinal mechanoreceptors. Moderate digital pressure was also applied to locate these endings more exactly.

Chemical stimulation of the mechanoreceptors

Whenever an interoceptor was identified mechanically, intra-arterial chemical stimuli were applied. Pharmacological drugs were administered by performing close intra-arterial injections through a catheter introduced into the right femoral artery so that its tip was located at the level of the coeliac artery irrigating the upper part of the small intestine. A post mortem 1% methylene blue injection (Sigma, Saint Quentin-Fallavier, France) was carried out to check that the substances injected irrigated only the upper part of the small intestine. To prevent the occurrence of any tachyphylaxic events, the time elapsing between successive injections was set at 60 min. When testing whether CCK, SP and phenylbiguanide (PBG) modified the effects of Il-1β and leptin, and to ensure that the discharge frequency had returned to its baseline value, we chose an interval of 20 min: in our experiments, the activatory effects of CCK on the discharge frequency of intestinal afferents lasted about 11 min and previous authors have indicated a similar duration of 12 min for these effects (Schwartz et al. 1991). In addition, we reported in a previous paper that the excitatory effects of Il-1β on intestinal motility, which were probably mediated via the activation of vagal mechanoreceptors, were present 20 min after pretreatment by CCK (Gaigéet al. 2003). Likewise, when testing whether Il-1ra modified the effects of Il-1β and leptin, this interval was reduced to 5 min, since this is the time this antagonist takes to block the interleukin-1 receptors (Gaigéet al. 2002, 2003).

Drugs

The following drugs were used: recombinant human interleukin-1β (Il-1β, AMGEN Thousand Oaks, USA), murine leptin lyophilized from a sterile filtered solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; AMGEN Thousand Oaks, USA), recombinant human interleukin-1β receptor antagonist (Il-1ra; AMGEN), sulphated cholecystokinin-8 (CCK; Sigma, Saint Quentin-Fallavier, France), substance P (SP; Sigma), phenylbiguanide (PBG; Sigma) and atropine sulphate salt (Sigma), CCK-A (lorglumide sodium salt) and CCK-B (CR 2945) receptor antagonists (Sigma).

All the substances were diluted in 1 ml of physiological saline and administered within 5 s. Each injection was followed by a flush with 1 ml of saline solution. Il-1β (Bucinskaite et al. 1997; Kurosawa et al. 1997) and leptin were injected at the following doses: 0.1, 1 and 10 μg (99.50, 995.02, 9950.25 pmol and 6.25, 62.50, 625.00 pmol, respectively). CCK, SP and PBG were injected in a 10 μg dose (8.75, 7.42 and 56.43 nmol, respectively). All these doses were similar to those previously used by Gaigéet al. (2002) to activate vagal afferent fibres. Il-1ra and atropine were administered in a 250 μg dose (14.71 and 369.39 nmol, respectively; Bouvier & Gonella, 1981; Gaigéet al. 2002). CCK-A and CCK-B receptor antagonists were administered in a 250 μg dose (Kurosawa et al. 2000). The weight of the animals was not taken into account, since the drugs were injected by performing close intra-arterial injections into the intestine.

Statistical analysis

When the activity of several mechanoreceptors was recorded in the same animal, only the first unit recorded was included in the statistical analysis. At each injection, the mean discharge frequencies (AP s−1) of the afferent neurones were calculated during 30 s periods before (controls) and after the time of drug administration (effects). At each injection, we calculated the percentage difference between the mean discharge frequencies. Results are expressed as mean percentages ±s.e.m. The values given in parentheses are the mean discharge frequency before the injection ±s.e.m.versus the mean discharge frequency after the injection ±s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's paired or unpaired t test to assess the significance of the results. An analysis of variance followed by a Scheffépost hoc test were also carried out to compare the effects of multiple drug injections. The significance level was taken to be P < 0.05.

Results

Thirty-four vagal neurones of the small intestine responding to mechanical stimulation were studied in 34 cats (one neurone per cat). All these neurones had unmyelinated fibres with conduction velocities ranging between 0.8 and 1.2 m s−1. Their basal discharge frequencies ranged from 1.27 to 2.43 AP s−1 (mean value: 1.82 ± 0.59 AP s−1).

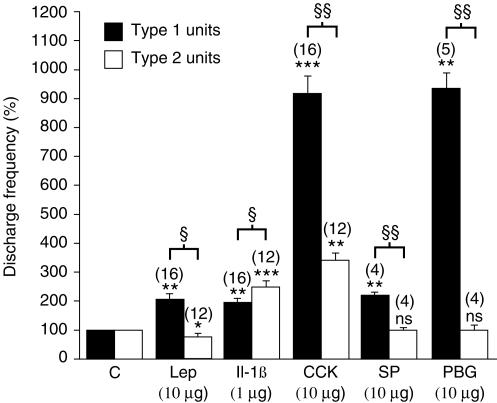

Effects of leptin on the activity of intestinal mechanoreceptors

Leptin was injected intra-arterially (i.a.) at a dose of 10 μg to 34 mechanoreceptors. In 16 mechanoreceptors, leptin significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 110 ± 21% with a latency of 9 ± 1 s and a duration of 308 ± 43 s (Table 1; Fig. 1). In 12 mechanoreceptors, leptin significantly decreased the mean discharge frequency by 20 ± 6% with a latency of 8 ± 1 s and a duration of 143 ± 21 s (Table 1; Fig. 1). In the six remaining mechanoreceptors, leptin had no effect on the mean discharge frequency. These results are similar to those obtained in our previous study (Gaigéet al. 2002). The mechanoreceptors are therefore again referred to here as type 1 units in the case of the 16 neurones which were activated and type 2 units in that of the 12 neurones which were inhibited.

Table 1.

Effects of leptin, Il-1β, CCK, SP and PBG alone or in combinations on the discharge frequency of type 1 and type 2 units intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors

| Type 1 units (n = 16) Discharge frequency | Type 2 units (n = 12) Discharge frequency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs (doses) | Before injection | After injection | P < | n | Before injection | After injection | P < | n |

| Leptin (10 μg) | 2.09 ± 0.23 | 4.41 ± 0.47 | 0.01 | 16 | 1.76 ± 0.15 | 1.42 ± 0.20 | 0.05 | 12 |

| Il-1β (0.1 μg) | 1.99 ± 0.35 | 2.74 ± 0.52 | 0.05 | 7 | 2.12 ± 0.29 | 3.82 ± 0.44 | 0.01 | 6 |

| Il-1β (1 μg) | 1.88 ± 0.41 | 3.74 ± 0.24 | 0.01 | 16 | 2.00 ± 0.36 | 5.16 ± 0.40 | 0.001 | 12 |

| Il-1β (10 μg) | 2.08 ± 0.41 | 4.89 ± 0.77 | 0.01 | 7 | 2.23 ± 0.57 | 8.23 ± 0.72 | 0.001 | 6 |

| CCK (10 μg) | 2.01 ± 0.53 | 18.81 ± 2.03 | 0.001 | 16 | 1.89 ± 0.58 | 6.43 ± 0.69 | 0.01 | 12 |

| SP (10 μg) | 2.08 ± 0.48 | 4.82 ± 0.43 | 0.01 | 4 | 2.01 ± 0.34 | 1.99 ± 0.51 | n.s. | 4 |

| PBG (10 μg) | 1.94 ± 0. 29 | 17.96 ± 0.99 | 0.01 | 5 | 1.96 ± 0.23 | 1.96 ± 0.31 | n.s. | 4 |

| Leptin (10 μg) after CCK (10 μg) | 1.76 ± 0.42 | 7.25 ± 0.55 | 0.001 | 16 | 1.81 ± 0.33 | 1.82 ± 0.47 | n.s. | 12 |

| IL-1β (0.1 μg) after CCK (10 μg) | 1.88 ± 0.19 | 3.47 ± 0.55 | 0.01 | 7 | 1.92 ± 0.24 | 1.99 ± 0.30 | n.s. | 6 |

| IL-1β (1 μg) after CCK (10 μg) | 1.96 ± 0.31 | 7.96 ± 0.43 | 0.001 | 16 | 1.98 ± 0.57 | 1.93 ± 0.42 | n.s. | 12 |

| IL-1β (10 μg) after CCK (10 μg) | 1.93 ± 0.41 | 8.67 ± 0.38 | 0.001 | 7 | 1.89 ± 0.49 | 1.91 ± 0.53 | n.s. | 6 |

| IL-1β (1 μg) after SP (10 μg) | 2.08 ± 0.61 | 4.19 ± 0.67 | 0.01 | 4 | 1.89 ± 0.38 | 4.75 ± 0.43 | 0.01 | 4 |

| IL-1β (1 μg) after PBG (10 μg) | 1.79 ± 0.76 | 3.75 ± 0.92 | 0.01 | 5 | 1.76 ± 0.32 | 4.31 ± 0.52 | 0.01 | 4 |

| IL-1β (1 μg) after CCK-RA (250 μg) | ||||||||

| and CCK-RB (250 μg) | 1.87 ± 0.31 | 3.72 ± 0.48 | 0.05 | 3 | 1.94 ± 0.32 | 4.99 ± 0.28 | 0.01 | 3 |

| CCK (10 μg) after CCK-RA (250 μg) | ||||||||

| and CCK-RB (250 μg) | 2.01 ± 0.27 | 2.00 ± 0.32 | n.s. | 3 | 1.96 ± 0.19 | 1.98 ± 0.23 | n.s. | 3 |

| IL-1β (1 μg) after IL-1ra (250 μg) | 1.97 ± 0.32 | 1.97 ± 0.26 | n.s. | 4 | 2.01 ± 0.51 | 2.00 ± 0.54 | n.s. | 4 |

| Leptin (10 μg) after IL-1ra (250 μg) | 1.96 ± 0.40 | 1.95 ± 0.37 | n.s. | 4 | 2.07 ± 0.21 | 0.93 ± 0.16 | 0.01 | 4 |

| Distension | 1.85 ± 0.26 | 4.52 ± 0.12 | 0.01 | 13 | 2.11 ± 0.53 | 8.16 ± 0.94 | 0.01 | 9 |

Values for discharge frequency are means ±s.e.m. The number of units (n) and the significance are indicated. n.s., non-significant, CCK-RA, CCK-A receptor antagonist, CCK-RB, CCK-B receptor antagonist.

Figure 1. Statistical analysis of the effects of leptin (Lep), Il-1β, CCK, SP and PBG on the activity of type 1 and type 2 intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors.

The black columns give the mean value of the effects of the drug on the type 1 units and the open columns give the mean value of the effects of the drug on the type 2 units. Columns labelled C give the mean value of the control responses expressed as 100%. The effects of various drugs are expressed as mean values compared with the control value. In type 1 units, all the drugs injected had excitatory effects. In type 2 units, only CCK and Il-1β had excitatory effects, whereas SP and PBG had no effect, while leptin had inhibitory effects. The vertical bars at the top of the columns give the s.e.m. n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001: Student's paired t test was carried out to compare the effects of the drug with those of the control. §P < 0.05; §§P < 0.01: Student's unpaired t test with Scheffépost hoc test refers to the comparisons between the effects of the various drugs tested on the 2 types of units. The number of units (n) is indicated in parentheses above the histograms.

Effects of Il-1β on the activity of the three types of intestinal mechanoreceptors defined in terms of the effects of leptin

Il-1β was injected intra-arterially (i.a.) at the following doses: 0.1, 1 and 10 μg (99.50, 995.02, 9950.25 pmol). The effects of Il-1β on the three types of units defined in terms of their response to leptin were analysed. The effects of Il-1β administered to the 34 mechanoreceptors were as follow: the 16 type 1 units were slightly activated (Fig. 2), the 12 type 2 units were more strongly activated (Fig. 3) and the six leptin-insensitive units showed no effect (not illustrated).

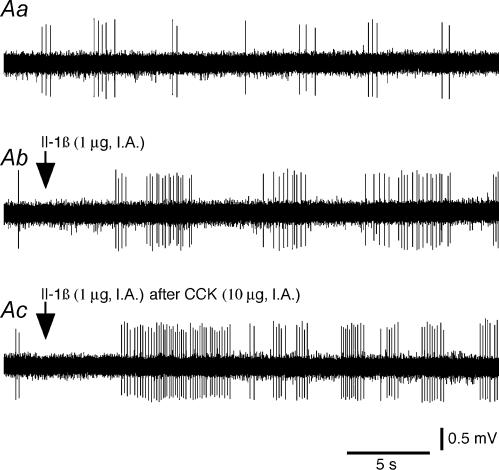

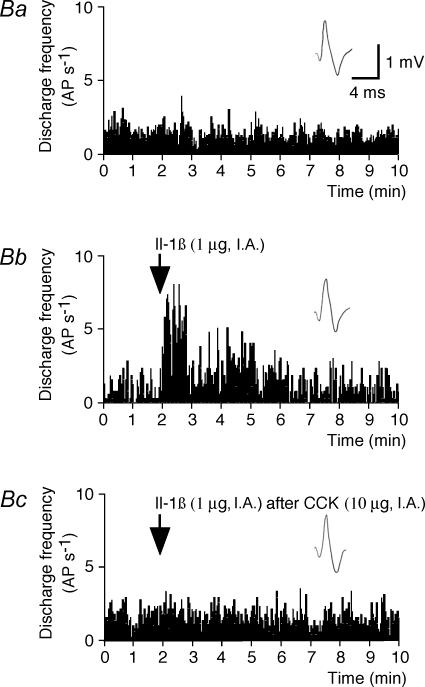

Figure 2. Effects of Il-1β on the activity of a type 1 intestinal vagal mechanoreceptor before and after CCK.

A, effects of Il-1β before and after CCK on the activity of a type 1 unit. Aa(control), the basal activity consisted of a few bursts of spikes. Ab, Il-1β administration (arrow) induced an activation of the receptor discharge. Ac, Il-1β administered (arrow) 20 min after CCK induced a practically continuous discharge of the receptor, which indicates that the effects of Il-1β were enhanced by the prior injection of CCK. Ab, 10 s after Aa; Ac, 80 min after Ab. B, histograms comparing the effects of Il-1β and those of Il-1β after CCK on the activity of the same type 1 unit. Ba, control. Bb, Il-1β administration (arrow). Bc, Il-1β administered (arrow) 20 min after CCK. Top traces in insets in Ba–c are the same reference waveform as that recorded at the beginning of Ba. AP s−1: action potential per second.

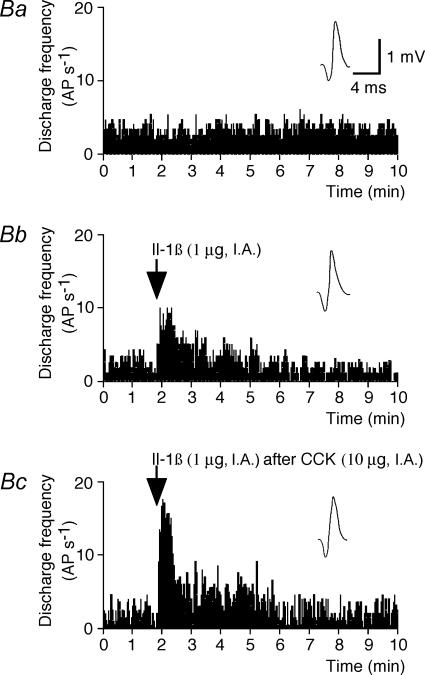

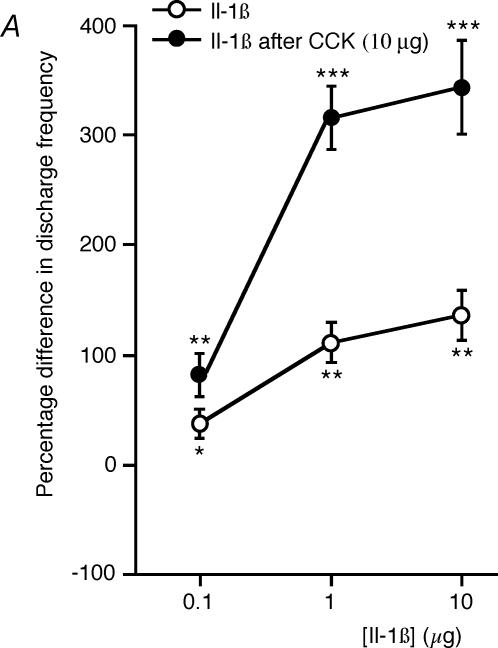

Figure 3. Effects of Il-1β on the activity of a type 2 intestinal vagal mechanoreceptor before and after CCK.

A, effects of Il-1β before and after CCK on the activity of a type 2 unit. Aa(control), the basal activity consisted of a few bursts of spikes. Ab, Il-1β administration (arrow) induced a strong activation of the receptor. Ac, Il-1β administration (arrow) 20 min after CCK had no further effect on the discharge frequency of the receptor, which indicates that the effects of Il-1β were inhibited by the prior injection of CCK. Ab, 10 s after Aa; Ac, 80 min after Ab. B, histograms comparing the effects of Il-1β and those of Il-1β after CCK on the activity of the same type 1 unit. Ba, control. Bb, Il-1β administration (arrow). Bc, Il-1β administered (arrow) 20 min after CCK. Top traces in insets in Ba–c are the same reference waveform as that recorded at the beginning of Ba. AP s−1: action potential per second.

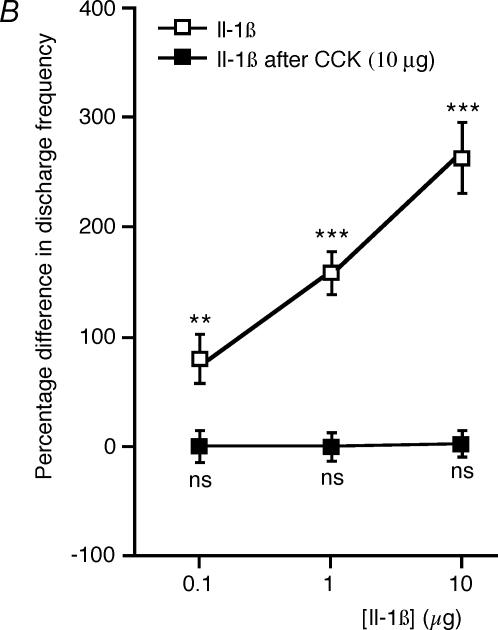

The responses of seven type 1 units were studied at three increasing doses of Il-1β: 0.1, 1 and 10 μg. Il-1β significantly increased (P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively) the mean discharge frequency (37 ± 7, 108 ± 16 and 136 ± 24%, respectively; Table 1, Fig. 4A, ◯). These effects had the following latencies: 5 ± 1, 6 ± 1 and 6 ± 1 s, respectively, and the following durations: 253 ± 38, 288 ± 31 and 308 ± 34 s, respectively. The responses of six type 2 units were also studied at three increasing doses (0.1, 1 and 10 μg) of Il-1β. Il-1β increased (P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively) the mean discharge frequency (80 ± 10, 158 ± 14 and 262 ± 26%, respectively; Table 1, Fig. 4B, □). These effects had the following latencies: 6 ± 1, 6 ± 1 and 6 ± 2 s, respectively, and the following durations: 189 ± 26, 207 ± 24 and 230 ± 33 s, respectively. Significant differences between the responses to three doses (0.1, 1 and 10 μg) of Il-1β were observed in the type 1 units and the type 2 units: the type 2 unit responses to Il-1β were significantly (P < 0.05, P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) more intense and (P < 0.05 at all these doses) had shorter durations than the type 1 unit responses. It is worth noting that there was no significant difference between the spontaneous responses recorded from type 1 units (1.98 ± 0.41 AP s−1) and type 2 units (2.05 ± 0.38 AP s−1).

Figure 4. Dose–response curve of the effects of Il-1β on the activity of type 1 and type 2 intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors before and after CCK.

A, dose–response curve showing the effects of Il-1β on the activity of type 1 units before and after CCK (n = 7). At each dose, the excitatory effects of Il-1β were enhanced after CCK administration. B, dose–response curve showing the effects of Il-1β on the activity of type 2 units before and after CCK (n = 6). At each dose, the excitatory effects of Il-1β were inhibited after CCK administration. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

The dose–response curves indicate that a dose of 1 μg of Il-1β can be routinely employed to stimulate these two types of intestinal vagal chemosensitive mechanoreceptors, since this is the normal dose used to induce a strong response (Fig. 4). In the 16 type 1 units, 1 μg Il-1β significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 98 ± 17% (Table 1, Fig. 1), with a latency of 6 ± 1 s and a duration of 297 ± 31 s. In the 12 type 2 units studied, 1 μg Il-1β significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 152 ± 24% (Table 1, Fig. 1), with a latency of 6 ± 1 s and a duration of 197 ± 26 s. In the six leptin-insensitive mechanoreceptors, 1 and 10 μg of Il-1β did not affect the mean discharge frequency (not illustrated).

The effects of the vehicle were investigated in the case of each unit and no significant changes in spontaneous activity were recorded after intra-arterial administration. In three type 1 units and three type 2 units, atropine (250 μg, i.a.), a muscarinic receptor blocking agent, administered before Il-1β (1 μg) did not affect the excitatory responses (not illustrated). Sectioning the vagus nerve caudally to the nodose ganglion abolished the spontaneous activity of all three types of units (type 1, n = 3; type 2, n = 3; Il-1β-insensitive, n = 4), and no effects of Il-1β on the chemosensitive mechanoreceptors were observed (n = 6) (not illustrated). At all the doses tested, Il-1β injection did not affect the intraluminal intestinal pressure, the arterial pressure (103.42 ± 7.59 versus 107.72 ± 9.51 mmHg) and the cardiac frequency (71.52 ± 0.84 versus 72.87 ± 0.58 beats min−1, n = 34).

The activity of several mechanoreceptors was recorded in six cats. In three of these cats, type 1 and type 2 units were identified; and in the others, all three types of units (type 1, type 2, and Il-1β-insensitive) were detected (not illustrated).

Effects of CCK, SP and PBG on the activity of intestinal mechanoreceptors

Effects of CCK

CCK (10 μg, i.a.) increased the mean discharge frequency in all the units tested (n = 28), whether they were type 1 units (n = 16) or type 2 units (n = 12). The mean discharge frequency of the leptin- and Il-1β-insensitive units was not affected by the injection of CCK (n = 6). In the type 1 units, a significant increase in the mean discharge frequency (Table 1, Fig. 1) was observed, amounting to 832 ± 87%, with a latency of 7 ± 1 s and a duration of 481 ± 76 s. The significant increase in the mean discharge frequency of 240 ± 40% observed with the type 2 units after CCK (Table 1, Fig. 1) had a latency of 7 ± 1 s and a duration of 244 ± 25 s. A significant difference (P < 0.01) was found to exist between the activatory effects of CCK on type 1 and type 2 units (Fig. 1).

Effects of SP

SP in a 10 μg dose (i.a.) had no effect on the type 2 units (n = 4; Table 1, Fig. 1); whereas SP significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 137 ± 11% with a latency of 7 ± 2 s and a duration of 116 ± 21 s in the case of the type 1 units (n = 4; Table 1, Fig. 1).

Effects of PBG

PBG in a 10 μg dose (i.a.) had no effect on the type 2 units (n = 4; Table 1, Fig. 1), but significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 857 ± 91% with a latency of 9 ± 3 s and a duration of 73 ± 29 s in the case of the type 1 units (n = 5; Table 1, Fig. 1).

Effects of leptin on the activity of intestinal mechanoreceptors after administration of CCK

In all the 16 type 1 units, leptin injected 20 min after CCK (10 μg, i.a.) induced a significant increase in mean discharge frequency of 308 ± 49% with a latency of 9 ± 1 s and a duration of 323 ± 51 s. CCK was found to enhance (P < 0.01) the effects of leptin alone (Table 1). In all the 12 type 2 units, CCK administered 20 min before leptin was found to inhibit (P < 0.05) the effects of leptin (Table 1).

Effects of Il-1β on the activity of intestinal mechanoreceptors before and after administration of CCK, SP and PBG

Effects of Il-1β before and after CCK

In seven type 1 units, Il-1β was administered in doses of 0.1, 1 and 10 μg 20 min after CCK injection (10 μg, i.a.). In all seven units tested, significant increases (P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively) of 82 ± 22%, 321 ± 32% and 342 ± 47%, respectively, were observed in the mean discharge frequency (Table 1; Fig. 4A, ◯). In all the cases studied, CCK was found to significantly enhance (P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively) the effects of Il-1β described above (Figs 1 and 4A, •). On the other hand, the latencies (6 ± 2, 6 ± 1 and 6 ± 2 s, respectively) and durations (273 ± 33, 314 ± 47 and 310 ± 36 s, respectively) were not significantly different from those obtained with Il-1β prior to CCK administration. Nor did the latencies of the effects of Il-1β differ significantly from those of the effects of CCK.

In the 16 type 1 units, Il-1β was administered at 1 μg 20 min after CCK injection (10 μg, i.a.). In all 16 units tested (n = 16 including the seven units presented in Fig. 4A, ◯ and •), a significant enhancement of the effects of Il-1β (98 ± 17 versus 314 ± 29%) was observed (P < 0.01) (Table 1). An example of the effects of Il-1β on a type 1 unit after CCK is given in Fig. 2.

In six type 2 units tested with the three doses (0.1, 1 and 10 μg) of Il-1β, CCK was found to significantly inhibit (P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively) the effects of Il-1β described above (Table 1; Fig. 4B, ▪). In the 12 type 2 units, CCK injection performed 20 min before Il-1β (1 μg) significantly (P < 0.001) inhibited the excitatory effects of Il-1β described above (n = 12 including the 6 units presented in Fig. 4B, □ and ▪) (Table 1). An example of the effects of Il-1β on a type 2 unit after CCK is illustrated in Fig. 3.

It is worth noting that the injection of vehicle performed 20 min after CCK affected neither type 1 units (n = 3) nor type 2 units (n = 3) (not illustrated). Two injections of 1 μg Il-1β performed at an interval of 20 min both induced a similar increase in the discharge frequencies of the type 1 units (n = 3) and those of the type 2 units (n = 3) (not illustrated). In four type 1 units and three type 2 units, the responses of Il-1β (1 μg) administered 20 min after CCK were not affected by atropine (250 μg, i.a.) pretreatment (not illustrated).

Effects of Il-1β before and after SP

In the four type 1 units tested with Il-1β and SP, injecting Il-1β alone (1 μg) significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 107 ± 24% with a latency of 6 ± 1 s and a duration of 307 ± 38 s (Table 1). Il-1β administered to these four units 20 min after SP injection (10 μg, i.a.) also induced a significant increase of 109 ± 25% in the mean discharge frequency with a latency of 6 ± 1 s and a duration of 294 ± 37 s. Four type 2 units were tested with Il-1β and SP. Il-1β injected alone (1 μg) significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 157 ± 19% with a latency of 6 ± 1 s and a duration of 185 ± 22 s (Table 1). Il-1β administered 20 min after SP injection (10 μg, i.a.) also significantly inhibited the mean discharge frequency by 155 ± 16% with a latency of 6 ± 1 s and a duration of 196 ± 20 s. The excitatory effects of Il-1β on type 1 and type 2 units observed before SP did not differ significantly from those observed after SP.

Effects of Il-1β before and after PBG

In the five type 1 units tested with Il-1β and PBG, injecting Il-1β alone (1 μg) significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 100 ± 28% with a latency of 5 ± 1 s and a duration of 294 ± 40 s (Table 1). Il-1β administered in the same dose 20 min after PBG (10 μg, i.a.) induced a significant increase in the mean discharge frequency of 102 ± 21% with a latency of 6 ± 2 s and a duration of 298 ± 16 s. Four type 2 units were tested with Il-1β and PBG. Il-1β injected alone (1 μg) significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 155 ± 12% with a latency of 7 ± 1 s and a duration of 185 ± 37 s (Table 1). Il-1β administered in the same dose 20 min after PBG injection also significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 157 ± 12% with a latency of 7 ± 0 s and a duration of 205 ± 46 s. Previously administering PBG did not significantly affect the responses of the units of either type to Il-1β injection.

Effects of CCK-A and CCK-B receptor antagonist on the responses to Il-1β

In three type 1 units and three type 2 units tested with CCK-A and CCK-B receptor antagonists, 1 μg Il-1β injection alone significantly increased (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) the mean discharge frequency by 99 ± 18 and 164 ± 21% with latencies of 5 ± 1 and 6 ± 1 s and durations of 297 ± 52 and 187 ± 38 s, respectively. Injecting CCK-A and CCK-B receptor antagonist (250 μg, i.a. each) 5 min before Il-1β (1 μg) did not affect these two types of excitatory responses (Table 1).

In these type 1 and type 2 units, CCK injection (10 μg, i.a.) significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 807 ± 92 and 239 ± 59% with latencies of 7 ± 2 and 7 ± 1 s and durations of 476 ± 61 and 236 ± 54 s, respectively. The two antagonists administered together in the same doses before CCK (10 μg, i.a.) completely blocked (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively) the CCK-excitatory responses in the type 1 and type 2 units (Table 1). In those cases where both antagonists were administered 5 min before CCK, Il-1β (1 μg) injected 20 min after CCK (10 μg, i.a.) induced the same response as that obtained when Il-1β was injected alone (n = 3, type 1 units; n = 3, type 2 units) (not illustrated). CCK-A and CCK-B receptor antagonist pretreatment applied before CCK therefore blocks the effects of CCK pretreatment on the effects of Il-1β in the type 1 and type 2 units (not illustrated).

In addition, Il-1β administered 20 min after CCK and 5 min after both antagonists induced the same response as that obtained when Il-1β was injected 20 min after CCK (n = 3, type 1 units; n = 3, type 2 units) (not illustrated).

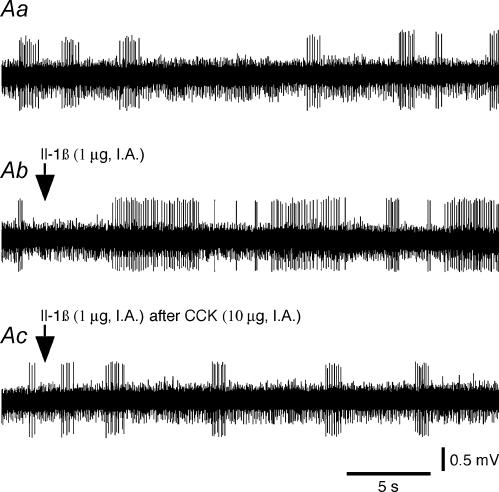

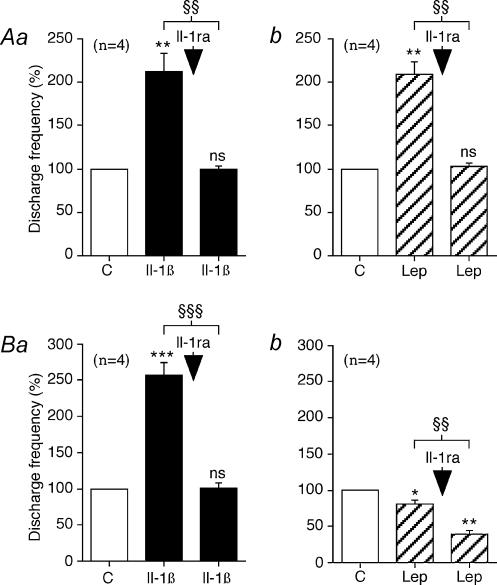

Effects of Il-1ra on the responses to Il-1β and leptin

In the four type 1 units tested with Il-1ra, the endogenous antagonist of Il-1β receptor, 1 μg Il-1β injection alone significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 108 ± 34% with a latency of 6 ± 1 s and a duration of 290 ± 46 s (Fig. 5Aa). Injecting Il-1β at the same dose 5 min after Il-1ra (250 μg, i.a.) had no further significant effects (Table 1, Fig. 5Aa). The same result was obtained in the four type 1 units tested with Il-1ra and leptin. Injection of 10 μg (i.a.) leptin alone significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 103 ± 25% with a latency of 8 ± 1 s and a duration of 304 ± 53 s (Fig. 5Ab). Leptin injected at the same dose 5 min after Il-1ra (250 μg, i.a.) had no further significant effects (Table 1, Fig. 5Ab).

Figure 5. Statistical analysis of the effects of Il-1β (1 μg, i.a.) and leptin (Lep; 10 μg, i.a.) before and after Il-1ra (250 μg, i.a.) on the type 1 and type 2 intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors.

In each group of traces: Aa and Ab show the effects on the type 1 units; Ba and Bb show the effects on the type 2 units. Aa and Ba: effects of Il-1ra (arrow) on the responses of Il-1β. Ab and Bb: effects of Il-1ra (arrow) on the responses of leptin. With each group of traces, the columns labelled C give the mean value of the control response (taken to be equal to 100%). Note that Il-1ra inhibited the excitatory effects of Il-1β on the type 1 and type 2 units. Il-1ra also inhibited the excitatory effects of leptin on the type 1 units, whereas it enhanced the inhibitory effects of leptin on the type 2 units. The vertical bars at the top of the columns give the s.e.m. n.s., not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001: Student's paired t test refers to the effects of the drug as compared to the control responses. §§P < 0.01; §§§P < 0.001: Scheffépost hoc test refers to the comparisons between the effects of the various drugs tested. The number of units (n) is indicated in parentheses.

In the four type 2 units tested, Il-1β administration (1 μg) alone significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 252 ± 42% with a latency of 6 ± 1 s and a duration of 201 ± 28 s. In all these type 2 units, the excitatory effects of Il-1β were significantly (P < 0.001) inhibited by Il-1ra (Table 1, Fig. 5Ba). In the four type 2 units tested, leptin administration (10 μg, i.a.) alone significantly decreased the mean discharge frequency by 22 ± 5% with a latency of 8 ± 1 s and a duration of 180 ± 22 s (Fig. 5Bb). In the four type 2 units, the inhibitory effects of leptin were significantly (P < 0.01) enhanced by Il-1ra, and leptin (10 μg, i.a.) injected 5 min after Il-1ra significantly decreased the mean discharge frequency by 55 ± 8% with a latency of 8 ± 1 s and a duration of 216 ± 34 s (Table 1, Fig. 5Bb).

Effects of intestinal distension on the three types of mechanoreceptors depending on the effects of leptin and Il-1β

The effects of a 20 cmH2O distension of the intestine on the three types of units defined in terms of their response to leptin and Il-1β were analysed. The three types of units responded differently to mechanical stimulation. In the 13 type 1 units, distension significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 143 ± 16% (Table 1). In the nine type 2 units, distension significantly increased the mean discharge frequency by 295 ± 55% (Table 1). In the six leptin- and Il-1β-insensitive units, distension significantly (P < 0.01) increased the mean discharge frequency by 278.54 ± 69.74% (1.98 ± 0.24 versus 7.61 ± 0.87 AP s−1). There was no significant difference between the responses to intestinal distension observed in type 2 units and leptin- and Il-1β-insensitive units, whereas these responses differed significantly (P < 0.01) from those of type 1 units.

Discussion

In a previous paper (Gaigéet al. 2002), we have shown that leptin affected the spontaneous discharge patterns of vagal chemosensitive mechanoreceptors in the intestine by increasing the discharge frequency of type 1 units and decreasing that of type 2 units and that the excitatory effect of leptin on type 1 units was blocked by Il-1ra.

In the present work, we show that the inhibitory effects of leptin on type 2 units were increased by Il-1ra. In addition, we demonstrate that Il-1β induced excitatory responses in both types of units. After pretreatment with CCK, these excitatory effects were enhanced in type 1 units and blocked in type 2 units. Our results strongly suggest that leptin has direct effects on type 2 units, whereas on type 1 units, these effects are mediated through the release of Il-1β.

Effects of Il-1β on intestinal vagal afferents

As demonstrated for leptin in a previous paper (Gaigéet al. 2002), the effects of Il-1β are definitely of peripheral origin and are not related to arterial distension associated with drug injection. Moreover, these effects are not due to motor activation, since Il-1β injection did not affect intestinal intraluminal pressure (Gaigéet al. 2003) and atropine, generally used to inhibit motor activity, did not modify these effects of Il-1β.

Our results are in agreement with electrophysiological data specifically indicating that Il-1β enhances the spontaneous activity of hepatic (Niijima, 1996) and gastric (Kurosawa et al. 1997, 2000; Ek et al. 1998) vagal nerve fibres. Contrary to what was observed by these studies; in which excitatory effect latencies of approximately 30 min were recorded, in our experiments, for the first time, the latencies of these effects were found to be very short (about 5 s). In addition, the short latencies of the excitatory effects observed here suggest that this substance acts directly on sensory endings. It is worth noting that this short latency is similar to that recorded in the case of CCK, with which a direct effect can also occur (Mei, 1978; Mei et al. 1996). In our study, the excitatory effects of Il-1β disappeared after the injection of Il-1ra, which suggests that Il-1β acts on specific receptors. Furthermore, cell bodies and fibres of the vagal sensory neurones express the mRNA corresponding to the Il-1β receptor (Ek et al. 1998). The excitatory effects of Il-1β on intestinal vagal afferent fibres are consistent with numerous data showing that the peripheral Il-1β message is transmitted via a vagal pathway to the brain, where it serves to depress food-motivated behaviour (Bret-Dibat et al. 1995), to induce fever (Watkins et al. 1995; Gordon, 2000) and hyperalgesia (Watkins et al. 1994), and to increase the extracellular noradrenaline concentration in the paraventricular nucleus in the hypothalamus (Fleshner et al. 1995; Hansen & Krueger, 1997; Ishizuka et al. 1997).

Interactions between Il-1β and CCK

In the type 1 units, the excitatory effects of Il-1β were enhanced by CCK, whereas in the type 2 units, they were inhibited by CCK. This cannot have been due to a tachyphylactic disorder, since two injections of Il-1β given 20 min apart had identical effects on both types of intestinal vagal afferent fibres. In the type 1 units, the excitatory effects of Il-1β after CCK were blocked by applying Il-1ra pretreatment, which shows that the enhancement of the effects was due to the binding of Il-1β to specific receptors. In addition, the effects of Il-1β alone on both types of units, and after CCK on the type 1 units, had the same latencies, which indicates that the same activation mechanisms were involved. In addition, the enhancement of the Il/1β effects observed in the type 1 units was a peripheral process, since afferent neurone activation (latency about 5 s) always occurs prior to the motor effects (latency about 20–25 s) (Gaigéet al. 2003). This was confirmed by the fact that the effects of Il-1β after CCK persisted under atropine. SP and PBG, which are routinely used to activate sensory visceral receptors (Paintal, 1973; Mei et al. 1996), activate type 1 units and have no effect on type 2 units. The fact that in both types of units, neither SP nor PBG alter the activatory effects of Il-1β indicates that these Il–1β–CCK interactions are actually specific. The enhancement of the Il-1β effects observed after applying CCK pretreatment to type 1 units cannot have been due to the well known excitatory effect of CCK on the basal activity (see Gaigéet al. 2002). CCK is known to activate vagal afferent nerve fibres via CCK-A and CCK-B receptors (Schwartz et al. 1994; Wank, 1995). This was confirmed by our results showing that the excitatory effects of CCK on the intestinal afferent nerve fibres are blocked by CCK-A and CCK-B receptor antagonists. There exist data in the literature indicating that Il-1β-induced excitation of vagal afferent nerve fibres is partly mediated by a release of CCK, which acts on specific receptors and thus directly activates mechanosensitive intestinal and gastric afferent fibres (Bucinskaite et al. 1997; Kurosawa et al. 1997, 2000). However, the results of the present study indicate that the excitatory effects of Il-1β on intestinal vagal fibres are not mediated by CCK-A or CCK-B receptors, since the effects of Il-1β on these two types of units are not blocked after pretreatment by CCK-A and CCK-B receptor antagonists. Moreover, the enhancement and blockade of the effects of Il-1β induced by CCK on the type 1 and type 2 units, respectively, are abolished upon applying CCK-A and CCK-B receptor antagonists, which indicates that for CCK/Il–1β interactions to occur, it is necessary for CCK to bind to specific receptors. This result also seems to indicate that Il-1β is able to directly activate intestinal vagal afferent nerve fibres. In addition, this blockade of the responses to CCK suggests that independent transduction mechanisms may mediate the response to CCK and to Il-1β. This idea is corroborated by studies showing that vagal sensory fibres express the mRNA corresponding to the Il-1β receptors (Ek et al. 1998) and by the presence of CCK-A and CCK-B receptor binding sites in the vagus nerve (Corp et al. 1993). Furthermore, in type 2 units, CCK pretreatment blocks the Il-1β excitatory effects, whereas CCK administration enhances spontaneous discharge patterns. These results show that a CCK binding step is required to modify the effects of Il-1β on both types of units. The changes in the effects of Il-1β induced by CCK pretreatment probably occur at the sensory ending level, since the process of CCK binding to specific receptors seems to modify the sensitivity of the Il-1β receptors on the vagal sensory endings so as to mediate or control various pathological responses as well as food intake behaviour. Bucinskaite et al. (1997) have described a sensitization of the responses of gastric vagal afferent nerve fibres to CCK. Our results show the existence of a different mechanism whereby CCK sensitizes Il-1β receptors on type 1 units. This is consistent with previous reports that CCK plays a role in the Il-1β-induced excitation of gastric vagal afferents and with data showing that the responses of gastric vagal afferent nerves in CCK-A receptor-deficient rats were more sensitive to intravenous administration of Il-1β than those of the control animals (Kurosawa et al. 1997, 2000). The present results on type 2 units are in agreement with the latter data, since CCK seems to be able to desensitize the Il-1β receptors present on intestinal sensory endings. Our findings on the interactions between CCK and Il-1β do not yield any information about the transductive mechanisms underlying the potentiation of the intestinal vagal mechanosensitive responses. However, interestingly, the fact that CCK is able to interfere with the effects of Il-1β as well as with those of leptin 20 min after its application supports the hypothesis that CCK may affect membrane permeability: previous data obtained on the myenteric sensory neurones indicate that these changes in membrane permeability may have long-term effects (Clerc et al. 1999; Rugiero et al. 2003).

Interactions between Il-1β and leptin

As established in our previous study (Gaigéet al. 2002) and confirmed by the present results, leptin induces an excitatory response which is enhanced by CCK in type 1 units, as well as an inhibitory response which is blocked by CCK in type 2 units. Il-1ra pretreatment blocks the excitatory effects of leptin in type 1 units, also providing evidence for the existence of functional links between leptin and Il-1β. These findings are supported by numerous data showing that leptin is not only involved in the control of food intake and body weight, but also in regulating immune responses (Bik et al. 2001). Leptin receptors have been described in macrophages and granulocytes in the lamina propria of the rat jejunum (Lostao et al. 1998).

As regards the excitatory effects of leptin on type 1 units, it is possible that leptin may induce a release of Il-1β, which in turn may activate the vagal sensory endings. Il-1β and leptin have similar excitatory effects, which are potentiated by CCK and blocked by Il-1ra. The existence of functional links between leptin and Il-1β has been corroborated by data showing that leptin induces Il-1β transcript by binding to the leptin receptors present in glial cells in the brain (Hosoi et al. 2000), that the effects of leptin on food intake and body temperature are mediated by a release of Il-1β (Luheshi et al. 1999) and that leptin up-regulates the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines both in vivo and in vitro (Loffreda et al. 1998).

As regards the inhibitory effects of leptin on type 2 units, our results show that these effects are not due to a release of Il-1β, since the type 2 units are activated by Il-1β. It is therefore possible that leptin may act directly on the vagal afferents, as suggested by several authors showing the existence of leptin receptors in vagal afferents (Buyse et al. 2001; Burdyga et al. 2002; Peiser et al. 2002). The fact that the inhibitory effects of leptin are enhanced in the presence of Il-1β may be due to the fact that leptin is able to induce the secretion of Il-1ra, as found to occur in human monocytes by Gabay et al. (2001). The intensity of the inhibitory effects of leptin on type 2 units therefore varies depending on the Il-1ra levels.

As strongly suggested in a previous study (Gaigéet al. 2002), our present results confirm that at least two different types of intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors are involved in the effects of leptin and Il-1β. It is worth noting that these units were both present in the same animal, which confirms that the various effects obtained were not due to the physiological condition of each animal. Although these two types of neurones cannot be differentiated in terms of their basal discharge frequency, morphology or conduction velocity (Harper & Lawson, 1985), they respond differently to mechanical stimulation and to various substances such as SP, PBG, CCK, leptin and Il-1β (Gaigéet al. 2002). These stimuli may act either independently or together on neural endings. The responses to combined stimuli may differ from responses to single stimuli. The responses of these various units therefore depend on the chemical environment. Thanks to these characteristics, they are able to transmit a variety of information to the CNS, mainly about peripheral inflammatory states and ingestion.

Our findings confirm that single vagal afferent neurones possess a polymodal sensitivity, since they respond to mechanical stimulation and to endogenous administration of substances such as CCK, Il-1β and leptin. This polymodal sensitivity is a general characteristic of the vagal mechanosensitive afferents (Schwartz et al. 1991). The results of the present study show that the information mediated by intestinal vagal afferent neurones is integrated first at peripheral level and secondly in the CNS, where it is used to produce the appropriate responses, such as variations in intestinal motility (Gaigéet al. 2003). Since type 1 and type 2 units are CCK-sensitive, they might be involved in the control of food intake. They are also Il-1β-sensitive and might therefore also be involved in the transmission of information about peripheral inflammation to the CNS. The main difference between type 1 and type 2 units is that type 1 units require a release of Il-1β to be responsive to leptin, whereas type 2 units do not. This difference may have some functional relevance. It is possible that type 2 units may generate acute satiety signals under physiological conditions whereas type 1 units may control food intake under pathological conditions (during inflammatory conditions, for instance).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank AMGEN (Thousand Oaks, USA) for their generous gifts of leptin, Il-1β and Il-1ra. We appreciated the helpful assistance of Mrs F. Farnarier in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Abysique A, Lucchini S, Orsoni P, Mei N, Bouvier M. Effects of alverine citrate on cat intestinal mechanoreceptor responses to chemical and mechanical stimuli. Aliment Pharm Therap. 1999;13:561–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnarlich F, Lopez J, Codoceo R, Jimenez M, Madero R, Montiel C. Relationship of plasma leptin to plasma cytokines and human survival in sepsis and septic shock. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:908–911. doi: 10.1086/314963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbier M, Cherbut C, Aube AC, Blottiere HM, Galmiche JP. Elevated plasma leptin concentrations in early stages of experimental intestinal inflammation in rats. Gut. 1998;43:783–790. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.6.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bik W, Wolinska-Witort E, Chmielowska M, Rusiecka-Kuczalek E, Baranowska B. Does leptin modulate immune and endocrine response in the time of LPS-induced acute inflammation. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2001;22:208–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier M, Gonella J. Nervous control of the internal anal sphincter of the cat. J Physiol. 1981;310:457–469. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bret-Dibat JL, Bluthe RM, Kent S, Kelley KW, Dantzer R. Lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-1 depress food-motivated behavior in mice by a vagal-mediated mechanism. Brain Behav Immun. 1995;9:242–246. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucinskaite V, Kurosawa M, Miyasaka K, Funakoshi A, Lundeberg T. Interleukin-1β sensitizes the response of the gastric vagal afferent to cholecystokinin in rat. Neurosci Lett. 1997;229:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00406-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdyga G, Spiller D, Morris R, Lal S, Thompson DG, Saeed S, Dimaline R, Varro A, Dockray GJ. Expression of the leptin receptor in rat and human nodose ganglion neurones. Neuroscience. 2002;109:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyse M, Ovesjo ML, Goiot H, Guilmeau S, Peranzi G, Moizo L, Walker F, Lewin MJ, Meister B, Bado A. Expression and regulation of leptin receptor proteins in afferent and efferent neurons of the vagus nerve. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:64–72. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc N, Furness JB, Kunze WA, Thomas EA, Bertrand PP. Long-term effects of synaptic activation at low frequency on excitability of myenteric AH neurons. Neuroscience. 1999;90:279–289. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corp ES, McQuade J, Moran TH, Smith GP. Characterization of type A and type B CCK receptor binding sites in rat vagus nerve. Brain Res. 1993;623:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90024-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ. Role of cytokines in infection-induced stress. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;697:189–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb49932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek M, Kurosawa M, Lundeberg T, Ericsson A. Activation of vagal afferents after intravenous injection of interleukin-1β: role of endogenous prostaglandins. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9471–9479. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faggioni R, Fantuzzi G, Fuller J, Dinarello CA, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. IL-1 beta mediates leptin induction during inflammation. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R204–R208. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.1.R204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleshner M, Goehler LE, Hermann J, Relton JK, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Interleukin-1 beta induced corticosterone elevation and hypothalamic NE depletion is vagally mediated. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37:605–610. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(95)00051-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis J, MohanKumar PS, MohanKumar SM, Quadri SK. Systemic administration of lipopolysaccharide increases plasma leptin levels: blockade by soluble interleukin-1 receptor. Endocrine. 1999;10:291–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02738628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay C, Dreyer M, Pellegrinelli N, Chicheportiche R, Meier CA. Leptin directly induces the secretion of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in human monocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:783–791. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaigé S, Abysique A, Bouvier M. Effects of leptin on cat intestinal vagal mechanoreceptors. J Physiol. 2002;543:679–689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaigé S, Abysique A, Bouvier M. Effects of leptin on cat intestinal motility. J Physiol. 2003;546:267–277. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaykema RPA, Dijkstra I, Tilders FJH. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy supresses endotoxin-induced activation of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons and ACTH secretion. Endocrinology. 1995;136:4717–4720. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.10.7664696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehler LE, Gaykema RPA, Hammack SE, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Interleukin-1 induces c-Fos immunoreactivity in primary afferent neurons of the vagus nerve. Brain Res. 1998;804:306–310. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00685-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehler LE, Relton JK, Dripps D, Keichle R, Tartaglia N, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Vagal paraganglia bind biotinylated interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: a possible mechanism for immune-to-brain communication. Brain Res Bull. 1997;43:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon FJ. Effect of nucleus tractus solitarius lesions on fever produced by interleukin-1β. Auton Neurosci-Basic. 2000;85:102–110. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(00)00228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen MK, Krueger JM. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy blocks the sleep- and fever-promoting effects of interleukin-1β. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R1246–R1253. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.4.R1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper AA, Lawson SN. Conduction velocity is related to morphological cell type in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones. J Physiol. 1985;359:31–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi T, Okuma Y, Nomura Y. Expression of leptin receptors and induction of IL-1β transcript in glial cells. Biochem Bioph Res Commun. 2000;273:312–315. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka Y, Ishida Y, Kunitake T, Kato K, Hanamori T, Mitsuyama Y, Kannan H. Effects of area postrema lesion and abdominal vagotomy on interleukin-1 beta-induced norepinephrine release in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus region in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1997;223:57–60. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa M, Bucinskaite V, Miyasaka K, Funakoshi A, Lundeberg T. Effects of systemic injection of interleukin-1β on gastric vagal afferent activity in rats lacking type A cholecystokinin receptors. Neurosci Lett. 2000;293:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa M, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Miyasaka K, Lundeberg T. Interleukin-1 increases activity of the gastric vagal afferent nerve partly via stimulation of type A CCK receptor in anesthetized rats. J Autonom Nerv Syst. 1997;62:72–78. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(96)00111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhans W. Anorexia of infection: current prospects. Nutrition. 2000;16:996–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loffreda S, Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Karp CL, Brengman ML, Wang DJ, Klein AS, Bulkley GB, Bao C, Noble PW, Lane MD, Diehl AM. Leptin regulates proinflammatory immune responses. FASEB J. 1998;12:57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lostao MP, Urdaneta E, Martinez-Anso E, Barber A, Martinez JA. Presence of leptin receptors in rat small intestine and leptin effect on sugar absorption. FEBS Lett. 1998;423:302–306. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luheshi GN, Gardner JD, Rushforth DA, Loudon AS, Rothwell NJ. Leptin actions on food intake and body temperature are mediated by IL-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7047–7052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SF, Wiertelak EP, Martin D, Watkins LR. Interleukin-1 mediates the behavioral hyperalgesia produced by lithium chloride and endotoxin. Brain Res. 1993;623:321–324. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91446-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei N. Thèse Doctorat en Sciences Naturelles. Marseille: 1968. Contribution à l'étude du nerf vague. [Google Scholar]

- Mei N. Disposition anatomique et propriétés électrophysiologiques des neurones sensitifs vagaux chez le chat. Exp Brain Res. 1970;11:465–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei N. Vagal glucoreceptors in the small intestine of the cat. J Physiol. 1978;282:485–506. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei N. Sensory structures in the viscera. In: Ottoson D, editor. Progress in Sensory Physiology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1983. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Mei N, Lucchini S, Grovum WL, Garnier L. Chemical sensitivity of digestive vagal mechanoreceptors with special reference to ‘in series' intestinal receptors. Prim Sensory Neuron. 1996;1:263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Niijima A. The afferent discharges from sensors for interleukin-1β in the hepatoportal system in the anesthetized rat. J Autonom Nerv Syst. 1996;61:287–291. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(96)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paintal AS. Vagal sensory receptors and their reflex effects. Physiol Rev. 1973;53:159–226. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1973.53.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiser C, Springer J, Groneberg DA, McGregor GP, Fischer A, Lang RE. Leptin receptor expression in nodose ganglion cells projecting to the rat gastric fundus. Neurosci Lett. 2002;320:41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugiero F, Mistry M, Sage D, Black JA, Waxman SG, Crest M, Clerc N, Delmas P, Gola M. Selective expression of a persistent tetrodotoxin-resistant Na+ current and NaV1.9 subunit in myenteric sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2715–2725. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02715.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarraf P, Frederich RC, Turner EM, Ma G, Jaskowiak NT, Rivet DJ, 3rd Flier JS, Lowell BB, Fraker DL, Alexander HR. Multiple cytokines and acute inflammation raise mouse leptin levels: potential role in inflammatory anorexia. J Exp Med. 1997;185:171–175. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GJ. Neural-immune gut-brain communication in the anorexia of disease. Nutrition. 2002;18:528–533. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(02)00781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GJ, McHugh PR, Moran TH. Integration of vagal afferent responses to gastric loads and cholecystokinin in rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R64–R69. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.1.R64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GJ, McHugh PR, Moran TH. Pharmacological dissociation of responses to CCK and gastric loads in rat mechanosensitive vagal afferents. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R303–R308. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.1.R303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi T, Sasaki K, Niijima A, Oomura Y. Leptin effects on feeding-related hypothalamic and peripheral neuronal activities in normal and obese rats. Nutrition. 1999;15:576–579. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Barrachina MD, Martinez V, Wei JY, Tache Y. Synergistic interaction between CCK and leptin to regulate food intake. Regul Peptides. 2000;92:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YH, Tache Y, Sheibel AB, Go VL, Wei JY. Two types of leptin-responsive gastric vagal afferent terminals: an in vitro single-unit study in rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R833–R837. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.2.R833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wank SA. Cholecystokinin receptors. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G628–G646. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.5.G628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LR, Goehler LE, Relton JK, Tartaglia N, Silbert L, Martin D, Maier SF. Blockade of interleukin-1 induced hyperthermia by subdiaphragmatic vagotomy: evidence for vagal mediation of immune-brain communication. Neurosci Lett. 1995;183:27–31. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)11105-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LR, Wiertelack EP, Goehler LE, Smith KP, Martin D, Maier SF. Characterization of cytokine-induced hyperalgesia. Brain Res. 1994;654:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C-S, Attele AS, Wu JA, Zhang L, Shi ZQ. Peripheral gastric leptin modulates brain stem neuronal activity in neonates. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G26–G30. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.3.G626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo H, Ichikawa H, Helke CJ. Neurochemistry of the nodose ganglion. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;52:79–107. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]