Abstract

Extracts of a multiply peptidase-deficient (pepNABDPQTE iadA iaaA) Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain contain an aspartyl dipeptidase activity that is dependent on Mn2+. Purification of this activity followed by N-terminal sequencing of the protein suggested that the Mn2+-dependent peptidase is DapE (N-succinyl-l,l-diaminopimelate desuccinylase). A dapE chromosomal disruption was constructed and transduced into a multiply peptidase-deficient (MPD) strain. Crude extracts of this strain showed no aspartyl peptidase activity, and the strain failed to utilize Asp-Leu as a leucine source. The dapE gene was cloned into expression vectors in order to overproduce either the native protein (DapE) or a hexahistidine fusion protein (DapE-His6). Extracts of a strain carrying the plasmid overexpresssing native DapE in the MPD dapE background showed a 3,200-fold elevation of Mn2+-dependent aspartyl peptidase activity relative to the MPD dapE+ strain. In addition, purified DapE-His6 exhibited Mn2+-dependent peptidase activity toward aspartyl dipeptides. Growth of the MPD strain carrying a single genomic copy of dapE on Asp-Leu as a Leu source was slow but detectable. Overproduction of DapE in the MPD dapE strain allowed growth on Asp-Leu at a much faster rate. DapE was found to be specific for N-terminal aspartyl dipeptides: no N-terminal Glu, Met, or Leu peptides were hydrolyzed, nor were any peptides containing more than two amino acids. DapE is known to bind two divalent cations: one with high affinity and the other with lower affinity. Our data indicate that the form of DapE active as a peptidase contains Zn2+ in the high-affinity site and Mn2+ in the low-affinity site.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium contains at least 12 peptidases able to degrade intracellular peptides (25). These peptidases vary in their substrate specificity. Some show a very broad substrate specificity hydrolyzing peptides of various lengths and amino acid compositions. Others have a very narrow range of activity. In S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, four well-characterized peptidases have been reported to be active in vitro toward N-terminal aspartyl peptides: PepB, a broad-specificity, leucine aminopeptidase family enzyme that hydrolyzes N-terminal aspartyl peptides of various lengths (24); PepE, an Asp-X-specific dipeptidase (8, 10, 14, 20); IadA, an isoaspartyl dipeptidase (12, 19); and IaaA, an isoaspartyl aminopeptidase (19). The in vivo contribution of each of these peptidases to the utilization of N-terminal Asp peptides is unknown, but a strain containing null mutations in the genes encoding each of the N-terminal Asp-hydrolyzing peptidases can grow on Asp-Leu as a Leu source (19). An additional Asp-Leu-hydrolyzing activity was identified in extracts of this strain, but this activity has not been characterized. Peptidase activity in these extracts was only detectable in the presence of manganese. The goal of this work was to identify this Mn2+-dependent peptidase and the gene encoding it and to characterize its activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

Nickel chelate columns for purification of His-tagged proteins were purchased from Qiagen. Restriction endonucleases were purchased from New England BioLabs. T4 kinase, T4 ligase, and Taq polymerase were purchased from Life Technologies. Pfu polymerase was obtained from Stratagene. Peptides were purchased from Bachem, and oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. N-Succinyl-l,l-diaminopimelate was generously provided by Richard Holz. All other buffers, metal salts, and chemicals were purchased from Sigma.

Bacterial strains and media.

Escherichia coli Top10F′ (Invitrogen) was used as a cloning host for all PCR products, and DH5α (Life Technologies) was used as a cloning host for all other constructs. E. coli BL21 (Novagen) served as an expression strain for all T7 promoter constructs. Table 1 lists the E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains used in this study. All S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains were derived from LT2. E medium (32) supplemented with 0.4% glucose and a 0.4 mM concentration of the appropriate amino acid(s) or peptide was used as a minimal medium, and Lennox L broth (LB; Gibco BRL) was used as a rich medium. Solid medium contained 1.5% Select agar (Sigma). As a supplement, meso-diaminopimelate (DAP) was added at 1 mM, and Casamino Acids were added at 0.1%. Kanamycin sulfate, sodium ampicillin, and chloramphenicol were used at final concentrations of 50, 100, and 20 μg/ml, respectively, when added to either liquid or solid medium. Liquid cultures were aerated by shaking on a rotary shaker, and all growth incubations were at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | ||

| TN1379 | leuBCD485 | Lab collection |

| TN1715 | leuBCD485 supQ302Δ(proAB pepD) pepN90 pepA16 pepB11 pepP1 pepQ1 pepT1 | Lab collection |

| TN5307 | As TN1379 plus vector pSE380 | Lab collection |

| TN5538 | leuBCD485 iaaA1::chl | Lab collection |

| TN5771 | As TN1379 plus pKD46 | This study |

| TN5834 | leuBCD485 pepT7::MudJ iadA50::chl | This study |

| TN5860 | As TN1715 plus iadA50::chl | This study |

| TN5862 | As TN5860 plus iadA100 | This study |

| TN5874 | leuBCD485 pepE25::chl | This study |

| TN5875 | As TN5862 plus pepE25::chl | This study |

| TN5879 | As TN5875 plus pepE50 | This study |

| TN5889 | As TN5879 plus iaaA1::chl | This study |

| TN5891 | As TN5889 plus ΔsitA | This study |

| TN5893 | leuBCD485 pepT7::MudJ plus pDK46 | This study |

| TN5896 | As TN5891 plus dapE2 | This study |

| TN5909 | As TN5891 plus dapE1::kan | This study |

| TN5910 | As TN1379 plus dapE1::kan | This study |

| TN5911 | As TN5889 plus dapE1::kan | This study |

| TN5934 | As TN5911 plus pSE380 | This study |

| TN5935 | As TN5911 plus pCM655 | This study |

| TN5936 | As TN5918 plus pSE380 | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA)U169 endA1 hsdR17 (rk− mk−) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco, BRL |

| Top10F′ | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 deoR araD139 d(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| BL21 | F−ompT hsdSb(rB−mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Novagen |

| TN5697 | BL21/pCM652 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR 2.1-TOPO | Cloning vector for PCR products | Invitrogen |

| pET28 | T7 promoter | Novagen |

| pSE380 | tac promoter | Stratagene |

| pKD46 | λ Red recombinase | B. L. Wanner |

| pKD2 | kan flanked by FRT recombinase sites | B. L. Wanner |

| pKD3 | cat flanked by FRT recombinase sites | B. L. Wanner |

| pCM651 | dapE-his6 on pCR2.1 TOPO | This study |

| pCM652 | dapE-his6 on pET28 | This study |

| pCM653 | dapE on pCR2.1 TOPO | This study |

| pCM655 | dapE on pSE380 | This study |

Isolation of an Mn2+-dependent peptidase overexpression mutant.

Strain TN5891 was mutagenized with nitrosoguanidine as described previously (23) and plated on minimal medium containing glucose, proline and Asp-Leu as a leucine source. Colonies showing increased diameter were purified. Extracts were prepared from these colonies and assayed for Mn2+-dependent Asp-Leu activity. TN5896, a strain that showed a threefold increase in activity (data not shown), was used for purification.

Purification of the Mn2+-dependent dipeptidase.

Strain TN5896 was grown aerobically to stationary phase in 30 liters of LB medium containing 2% glucose by the University of Illinois Fermentation Facility. Cells were concentrated to a slurry and pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C for 1 h at 5,000 rpm in a Beckman JA-10 rotor. The cell pellet was resuspended at 4°C in 500 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5 (Tris). Cells were lysed by sonication, and the sonicate was centrifuged at 17,000 rpm in a Beckman JA17 rotor for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant was precipitated with [NH4]2SO4 in three cuts at 0 to 25, 25 to 40, and 40 to 60% saturation. The precipitate from each fraction was collected by centrifugation and stored at −70°C until dialysis. Precipitates were resuspended in Tris and dialyzed 4 h in Pierce Snakeskin dialysis tubing (molecular weight cutoff of 10,000) against two changes of 20 liters of Tris at 4°C. The active fraction (25 to 40%) was loaded onto a Q-Sepharose 26/10 ion-exchange column. Chromatography was carried out with a flow rate of 3 ml/min in Tris with a gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl over an 800-ml volume, and 20-ml fractions were collected. Fractions were assayed for Asp-Leu hydrolysis in microtiter plates by using the amino acid oxidase assay (see below). Active fractions 28 and 29 eluted at 0.18 M NaCl. These fractions were pooled and dialyzed against 12 liters of Tris at 4°C. The dialyzed sample was concentrated in a Millipore Ultrafree 15 filter (molecular weight cutoff of 10,000) and loaded onto a Superdex 200 gel filtration column. Chromatography was carried out in Tris with 0.15 M NaCl at a flow rate of 1 ml/min over a 250-ml volume, and 2.5-ml fractions were collected. Fractions 65 to 67, which exhibited the highest activity, were pooled and concentrated in an Ultrafree 15 filter as described above and loaded onto a MonoQ HR 10/10 ion-exchange column, and chromatography was carried out at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min with a gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl over a volume of 80 ml. Active fractions were acetone precipitated, resuspended in 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Protein bands were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) by standard techniques and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Candidate peptidase bands were submitted for N-terminal sequencing to the University of Illinois Protein Sciences Facility.

Transduction.

Chromosomal mutations were transferred between S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains by using the generalized transducing phage P22HT 12/4 int-3 (30).

Construction of dapE, pepE, and iadA knockouts.

The oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table 2. Chromosomal disruptions of dapE, pepE, and iadA were constructed by the λ Red recombinase method of Datsenko and Wanner (11). For the dapE knockout, a 1.5-kb PCR product was amplified from plasmid pKD2 with oligonucleotides DapE1 and DapE2. This PCR product was gel purified and electroporated directly into strain TN5771, and transformants were selected on kanamycin to create TN5910. Insertion into dapE was confirmed by PCR with oligonucleotides DapE2, DapE3, and DapE4. In addition, this mutant was unable to grow in the absence of exogenously supplied DAP. We have termed this allele “dapE1::kan.”

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| DapE1 | 5′-TGAATCCCGTTATCAGCAGTTTTTTGATGAGGTGTAGTCTTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG-3′ |

| DapE2 | 5′-CCAGCCAGTCCATGCTTATTTCCTCTTACCGGAACGCTCACATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′ |

| DapE3 | 5′-GCTCTGCGCGCCCGGGAAGCCTCTG-3′ |

| DapE4 | 5′-GATAGGCGACGTGCCCCTGAACGCC-3′ |

| DapE5 | 5′-AAGCTTAAGGAGATATACCATGTCGTGCCCGGTTATTGAGC-3′ |

| DapE6 | 5′-CTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGCTCGAGGGCGACGAGCTGTTCC-3′ |

| DapE7 | 5′-TTTCCTCTTACCGGAAAGCTTATCAGGCGACGAGC-3′ |

| PepE1 | 5′-ATGGAACTGCTTTTATTAAGTAACTCGACGCTGCCGGGTATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG-3′ |

| PepE2 | 5′-TTAAAAGCGATGACCCGCTTCCAGCGCCACGGCCTCTTCGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG-3′ |

| IadA1 | 5′-ATGCCTGATTTATCCGCCGCGGAGTTTACCTTATTACAGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG-3′ |

| IadA2 | 5′-TTACGCTTCAAAGGTACCTTTTACGCAGGCTTTCCCCTATGAATATCCTCCTTAGTT-3′ |

| IadA3 | 5′-GCTGTCGATCTGGGTCATGCA-3′ |

| IadA4 | 5′-GGGGCAGCCTGAAACTAGCGGG-3′ |

For the pepE knockout, a 1.0-kb PCR product was amplified from plasmid pKD3 with oligonucleotides PepE1 and PepE2. This PCR product was gel purified and electroporated directly into strain TN5771, and transformants were selected on chloramphenicol to create TN5874. Insertion of the chloramphenicol resistance element was confirmed by loss of activity toward Asp-p-nitroanilide in extracts, loss of Asp-Leu peptidase activity of extracts subjected to nondenaturing PAGE and peptidase activity stain as described previously (27), and cotransduction of Chlr with these phenotypes. We have termed this pepE allele “pepE25::chl.”

For the iadA knockout, a 1.0-kb PCR product was amplified from plasmid pKD3 with oligonucleotides IadA1 and IadA2. This PCR product was gel purified and electroporated directly into strain TN5893, and transformants were selected on chloramphenicol to create TN5834. Insertion into the iadA gene was confirmed by PCR with oligonucleotides IadA3 and IadA4. Loss of IadA activity was also confirmed by analysis of activity in extracts subjected to nondenaturing PAGE. We have termed this iadA allele “iadA50::chl.”

Construction of TN5911.

The multiply peptidase-deficient (MPD) strain TN5911 was constructed from TN1715 by a series of transduction crosses. All selections were carried out on minimal glucose medium supplemented with Casamino Acids. The iad50::chl mutation was introduced into TN1715 by using TN5834 as a donor and with selection for chloramphenicol resistance to produce TN5860. The Chlr element in TN5860 was excised (11) to produce TN5862 carrying the deletion mutation iadA100. The pepE25::chl allele was introduced into TN5862 by transduction with TN5874 as a donor and selection for chloramphenicol resistance to produce TN5875. Excision of the Chlr element in TN5875 led to TN5879 carrying the deletion pepE50. TN5879 was used as a recipient and TN5538 was used as a donor in a cross-selecting chloramphenicol resistance to generate TN5889 containing iaaA1::chl. The dapE1::kan mutation was introduced into TN5889 by selection for kanamycin resistance to create TN5911. TN5911 (pepNABDPQTE iadA iaaA dapE) lacks all cytoplasmic peptidases known to produce free amino acids from peptides, except PepM, which is required for viability (26). The mutations in the pepN, pepA, pepB, pepD, pepE, iadA, iaaA, and dapE genes present in this strain are stable null alleles.

Construction of expression plasmids.

To construct a polyhistidine-tagged derivative of DapE, the dapE gene was cloned into vector pET28 (Novagen) under control of the T7 promoter. The 1.2-kb dapE gene was PCR amplified from strain TN1379 with Pfu polymerase with oligonucleotides DapE5 and DapE6. The 1.2-kb fragment was agarose gel purified, treated with Taq polymerase to add A tails, and cloned into vector pCR 2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen) to create plasmid pCM651. The 1.2-kb XhoI-HindIII fragment from pCM651 was cloned into pET28 (Novagen) to create pCM652. A native DapE-overproducing plasmid was also constructed. The 1.2-kb dapE gene was PCR amplified from strain TN1379 with oligonucleotides DapE5 and DapE7. The 1.2-kb fragment was agarose gel purified and cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO to create plasmid pCM653. The 1.2-kb HindIII fragment from pCM653 was cloned into plasmid pSE380 (Stratagene) to create plasmid pCM655. All clones were confirmed by restriction digest and sequencing. In addition, pCM655 was able to complement TN5910 in vivo for growth in the absence of DAP.

Expression and purification of recombinant DapE-His6.

Strain TN5697 was grown aerobically in LB with kanamycin. At an A600 of ≈0.4, the culture was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG) and grown for an additional 4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. The lysed sample was then centrifuged for 10 min at 17,000 rpm in a Beckman JA-17 rotor at 4°C, and the supernatant was applied to a nickel-chelate column (Qiagen). The column was eluted with imidazole according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified protein was homogeneous as judged by SDS-PAGE.

Preparation of metal-free buffer and vessels.

Metal was removed from all vessels, dialysis tubing, and stir bars by soaking overnight in 6 N nitric acid and rinsing five times with water deionized by a Milli-Q Plus Ultrapure water system (Millipore). Metal was removed from all buffers by initial preparation with metal-free water and subsequent passage over a Chelex-100 (Bio-Rad) column.

Preparation of apoenzyme and metal analysis.

Purified protein was dialyzed in metal-free Snakeskin dialysis tubing with a molecular weight cutoff of 10,000 (Pierce) against two changes of 2 liters of metal-free buffer in the presence of 1,10-phenanthroline [1 mM] and EDTA [5 mM] at 4°C for 4 h each. The preparation was then dialyzed against the same buffer in the absence of chelators. Samples were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry by the University of Illinois Waste Management Resources Center for zinc, manganese and cobalt content.

Peptidase assay.

DapE peptidase assays were performed in 100 mM Tricine (pH 8.0) at 37°C. Forty micrograms of protein for extracts and 50 to 500 ng of protein (depending on the substrate) for pure DapE were preincubated in a 0.5-ml reaction volume with or without metal at 37°C for 30 min. Reactions were initiated by the addition of substrate to a final concentration of 5 mM unless otherwise indicated. All assays for determining the specificity and kinetics of DapE by using high-performance liquid chromatography to monitor product formation were carried out essentially as described previously (20). DapE desuccinylation assays were performed in the same manner by monitoring the production of DAP. Because DAP was not completely derivatized by trinitrobenzenesulfonate in 5 min, the protocol was modified by extending the derivatization time to 1.5 h.

A semiquantitative l-amino acid oxidase-based assay was used for determination of peptidase activity in column fractions and for preliminary characterization of peptidase activities. Assays were carried out in the wells of plastic depression plates by preincubation of the protein sample in 50 mM Tricine (pH 8.0) in the presence or absence of metal for 30 min at 37°C. Substrate was then added, and the reaction mixture was incubated for an additional 30 min. The amino acid oxidase mixture, described previously (8), was then added, and color development was monitored either visually or by A420 in a plate reader.

RESULTS

Purification and N-terminal sequence.

The Mn2+-dependent peptidase activity was purified 39-fold by (NH4)2SO4 precipitation, anion-exchange chromatography, and gel filtration (Materials and Methods). The active fractions from the final purification step were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The elution volume of the activity on gel filtration indicated a native molecular mass of approximately 80 kDa, so we looked for protein bands on the SDS-PAGE gel that showed maximum staining intensity in the peak fraction of activity and had a molecular mass that might indicate a monomer, dimer, or trimer of a native 80-kDa protein. Protein bands at 35 and 40 kDa seemed to increase and decrease in intensity with the activity of the fractions, and we submitted these for N-terminal sequencing. The quality of the sequence for each was poor, but all reasonable sequences were used to query the S. enterica genome sequence in a BLAST search. The results indicated that both bands had the N-terminal sequence of DapE, N-succinyl-l,l-diaminopimelate desuccinylase, an enzyme required for the biosynthesis of DAP and of lysine. Because this enzyme carries out the same chemical reaction as a peptidase (amide hydrolysis), because succinate is structurally similar to aspartate, and because DapE is a member of a structural family that includes peptidases (3, 6, 22) we decided to test the hypothesis that DapE can act as an aspartic-specific dipeptidase as well as a desuccinylase.

The Mn2+-dependent aspartyl peptidase is DapE.

To show that dapE encodes the Mn2+-dependent aspartyl peptidase activity, we first constructed a strain containing no other peptidases that would interfere with our peptidase assay. Strain TN5889 contains mutations in each of the genes encoding peptidases that can produce free amino acids, except pepM, which is vital. This strain contains null mutations in all of the genes encoding broad specificity peptidases (pepN, pepA, pepB, and pepD) and all of those encoding Asp-specific peptidases (pepE, iadA, and iaaA). The strain also contains point mutations in genes encoding the X-Pro-specific enzymes (pepP and pepQ) and in pepT, a gene encoding an anaerobically induced aminotripeptidase. Extracts of TN5889 are able to catalyze the hydrolysis of Asp-Leu, but only in the presence of Mn2+ (Table 3). A chromosomal disruption of dapE was constructed and introduced into TN5889. Unlike the parent strain, extract from the dapE mutant, TN5911, was inactive toward Asp-Leu even in the presence of Mn2+ (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Asp-Leu hydrolysis by crude extracts and pure DapE-His6

| Sample | MnCl2 concn (mM) | Sp act (nmol/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| TN5889 (MPD dapE+)a | 0.0 | <0.5 |

| 1.0 | 25.0 | |

| TN5911 (MPD dapEI)a | 0.0 | <0.5 |

| 1.0 | <0.5 | |

| TN5935 (MPD dapE1/pCM655)a | 0.0 | <0.5 |

| 1.0 | 80,500 | |

| DapE-His6b | 0.0 | <0.5 |

| 1.0 | 222,200 |

Crude extract.

Purified by nickel-chelate chromatography.

The dapE gene was cloned into the Taq promoter vector, pSE380, for expression as the native protein. Peptidase activity from extracts of TN5935 overexpressing DapE from this construct was nearly 3,200-fold greater than that found in the single-copy genomic dapE+ strain, TN5889 (Table 3). To demonstrate that the product of the dapE gene was the peptidase, we cloned the dapE gene into vector pET28 under the IPTG-inducible T7 promoter to be expressed as a C-terminal hexahistidine fusion protein (DapE-His6). Purification of this protein by nickel-chelate chromatography yielded a pure preparation that hydrolyzed Asp-Leu in the presence of MnCl2 (Table 3).

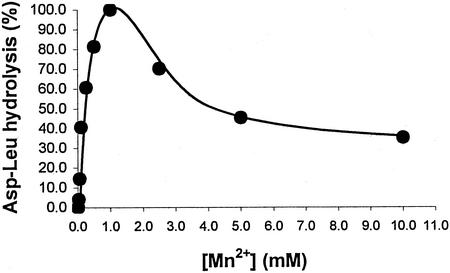

Metal activation of DapE.

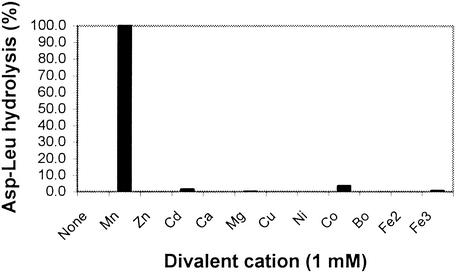

The specificity of metal ion activation of hydrolysis of Asp-Leu by DapE-His6 was examined. Mn2+ activated DapE at least 15-fold more efficiently than any other cation (Fig. 1). Activity was detectable, but very low, for the Co2+-, Cd2+-, and Fe3+-activated enzymes. In addition, DapE-His6 metal activation by combinations of cations was analyzed qualitatively using the amino acid oxidase assay (Materials and Methods). The cations tested were MnCl2, ZnCl2, MgCl2, CdCl2, NiSO4, CuCl2, FeCl2, FeCl3, CaCl2, and CoCl2, each at 0.1 mM in pairs. No combination of metal that did not include MnCl2 was able to stimulate DapE-His6-catalyzed hydrolysis of Asp-Leu better than Mn2+ alone (data not shown). The dependence of the rate of DapE-His6-catalyzed hydrolysis of Asp-Leu on Mn2+ is shown in Fig. 2. There is a sharp maximum at 1 mM, with inhibition at higher Mn2+ concentrations. Half-maximal activity is achieved at 160 μM Mn2+. Previous work with DapE revealed a Km of 4.0 μM for cobalt activation of desuccinylase activity (21).

FIG. 1.

Effect of divalent cations on DapE-His6-catalyzed hydrolysis of Asp-Leu. An activity level of 100% is 222 μmol/min/mg. Divalent cations (as chloride salts) were present at 1 mM.

FIG. 2.

Mn2+ dependence of DapE-His6-catalyzed hydrolysis of Asp-Leu.

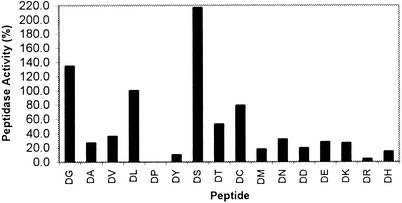

DapE substrate specificity.

Purified DapE-His6 was tested for its ability to catalyze the hydrolysis of a variety of dipeptides. As shown in Fig. 3, DapE-His6 was able to hydrolyze all Asp-X (where “X” represents any standard amino acid) peptides tested, except Asp-Pro. Asp-Ser was the best substrate, followed by Asp-Gly, Asp-Leu, and Asp-Cys at rates greater than 30% that of Asp-Ser. Several larger N-terminal Asp peptides (DLG, DLF, DLW, DYM, DDD, DLK, DLKK, and DLKKK) were tested, and none was detectably hydrolyzed. We were unable to detect DapE-His6-catalyzed hydrolysis of any of the other X-Leu peptides or any Leu-X peptides by using the amino acid oxidase assay. We estimate that a rate of 0.05% of the rate of Asp-Leu hydrolysis would have been detected in this assay. Of particular note was the failure of DapE-His6 to catalyze the hydrolysis of β-Asp-Leu, Glu-Leu, or Asp-p-nitroanilide (DpNA), distinguishing its specificity from the previously identified S. enterica aspartyl peptidases, IadA (β-Asp-Leu), IaaA (β-Asp-Leu), PepB (Glu-Leu), and PepE (DpNA). These results taken together indicate that DapE can act as an Mn2+-dependent aspartyl dipeptidase.

FIG. 3.

Substrate specificity of DapE-His6 for aspartyl peptides. The activity for Asp-Leu is set as 100%.

Mn2+ activation of DapE peptidase activity occurs by Mn2+ binding to the weaker of two metal-binding sites.

Metal-binding residues in DapE have been identified based on sequence similarity to proteins in the MH clan of peptidases (3): carboxypeptidase G2 (CPG2), peptidase T (PepT), and acetylornithine deacetylase (ArgE). The evolutionary and structural relationship of these enzymes has been pointed out previously, and it has been proposed that theses enzymes are in the same superfamily of cocatalytic metallohydrolases as leucine aminopeptidase (6, 22). Enzymes in this superfamily contain two metal-binding sites of unequal affinities, and proposed mechanisms for several of these enzymes suggest that both metal ions act catalytically (5, 9, 15, 31). Many of these enzymes purify with zinc bound to the high-affinity site, but the weakly bound metal is variable and can be easily exchanged in vitro (5, 7, 17, 28). DapE from Haemophilus influenzae was shown to purify with 0.838 mol of zinc/monomer, and attempts to exchange this metal with cobalt were only partially successful, even when the enzyme was dialyzed in the presence of 100 mM cobalt (5). Presumably, activation of DapE desuccinylase by Co2+ occurs by binding to the weak binding site to create a Zn2+/Co2+ enzyme. To determine if Mn2+ activation of peptidase activity involves the formation of a Zn2+/Mn2+ enzyme, DapE was dialyzed in metal-free buffer with and without the metal chelators EDTA and 1,10-phenanthroline, followed by dialysis in metal-free buffer to remove the chelators. Analysis of the metal content of the material dialyzed in the absence of chelators revealed that it contained 0.802 mol of zinc/monomer. The material dialyzed in the presence of chelators contained 0.422 mol of zinc/monomer of DapE-His6, indicating that removal of the tightly bound zinc is partial even after prolonged treatment with chelators. Maximal Mn2+ activation of both these preparations occurred at 1 mM Mn2+, with the metal-free-dialyzed and chelator-dialyzed samples exhibiting 77.4 and 64.4% of the activity of the undialyzed control, respectively. We assumed that the dialyzed samples could not be fully activated with Mn2+ as a result of partial loss of the tightly bound Zn2+, but attempts to reactivate the samples by addition of Zn2+ and Mn2+ failed to restore activity.

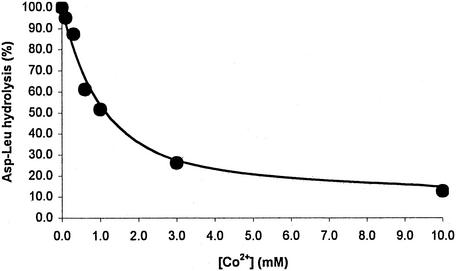

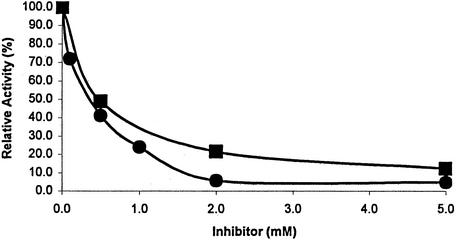

Since Co2+-activated DapE-His6 has very little peptidase activity, Co2+ should compete with Mn2+ and inhibit peptidase activity if they occupy the same binding site. As shown in Fig. 4, increasing concentrations of cobalt inhibited the activity of the Mn2+-activated peptidase. In the presence of 1 mM Co2+, the activity of the Mn2+-activated enzyme was 50% that observed in the absence of Co2+.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition by Co2+ of Mn2+-activated DapE-His6-catalyzed hydrolysis of Asp-Leu.

If Mn2+ binds to the weak binding site, we would expect that it would not remain associated with the enzyme after dialysis. To test this, DapE-His6 was activated with Mn2+ (1 mM) and dialyzed in metal-free buffer. As shown in Table 4, this preparation was inactive for Asp-Leu hydrolysis, but could be reactivated by the addition of Mn2+. A control that was not activated prior to dialysis showed slightly lower reactivation (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Effect of dialysis on Mn2+-activated DapE peptidase activity

| Sample | Concn (mM) of MnCl2:

|

Relative activity (%)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Added before dialysisa | In assay | ||

| Not activated | 0.0 | 0.0 | <0.1 |

| 0.0 | 1.0 | 70.1 | |

| Activated | 1.0 | 0.0 | <0.1 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 100.0 | |

Samples were dialyzed against two 4-h changes of metal-free 50 mM Tris-HCl at 4°C.

A total activity of 100% is 222 μmol/min/mg.

Because (i) DapE-His6 purifies with approximately 1 mol of Zn2+/monomer, and this Zn2+ cannot be completely removed even by dialysis in the presence of chelators; (ii) Co2+ competitively inhibits Mn2+-dependent peptidase activity; and (iii) Mn2+-activated DapE is inactive after dialysis, it is likely that Mn2+ activation of DapE-His6 peptidase activity involves the formation of a Zn2+/Mn2+ enzyme with Zn2+ bound to the high-affinity binding site and Mn2+ bound to the low-affinity binding site.

Kinetics of peptide hydrolysis and desuccinylation.

DapE-His6 was tested for its ability to hydrolyze N-succinyl-l,l-diaminopimelate (SDAP). In the presence of 1 mM Co2+, our enzyme preparation catalyzed the hydrolysis of this substrate with kinetic constants (Km = 0.63 mM, kcat = 242 s−1) similar to those observed by previous workers under somewhat different conditions (Km = 0.41 mM, kcat = 267 s−1 [21]; Km = 1.3 mM, kcat = 200 s−1 [5]). The kinetic constants observed for DapE catalyzed hydrolysis of Asp-Leu in the presence of 1.0 mM Mn2+ were Km = 3.3 mM and kcat = 113 s−1. The ratio (kcat/Km)SDAP/(kcat/Km)DL is approximately 11, indicating that the peptide is a poorer substrate than SDAP by only an order of magnitude. It should be noted that Asp-Leu is not the best peptide substrate for DapE (Fig. 3). Indeed, kinetic constants for Mn2+-activated DapE hydrolysis of Asp-Ser, the best peptide substrate, were Km = 0.66 mM and kcat = 96 s−1. The (kcat/Km)SDAP/(kcat/Km)DS ratio is only 2.6, indicating that DapE is only a slightly better desuccinylase than peptidase.

Asp-Leu inhibits DapE desuccinylase activity, and SDAP inhibits DapE peptidase activity.

Given the similarities in the catalytic reactions between these two substrates, we expected that both are hydrolyzed at the same active site and that each would be a competitive inhibitor of the hydrolysis of the other. As shown in Fig. 5, hydrolysis of Asp-Leu by Mn2+-activated DapE-His6 is inhibited by SDAP, and Co2+-activated DapE is inhibited by Asp-Ser. Asp-Ser was used in these experiments rather than Asp-Leu because it has a lower Km and would be expected to inhibit at lower concentrations.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of Mn2+-activated DapE-His6 Asp-Leu hydrolysis by SDAP (squares) and Co2+-activated DapE-His6 SDAP hydrolysis by Asp-Ser (circles). A peptidase activity level of 100% is 222 μmol/min mg. A desuccinlyase activity level of 100% is 353 μmol/min mg.

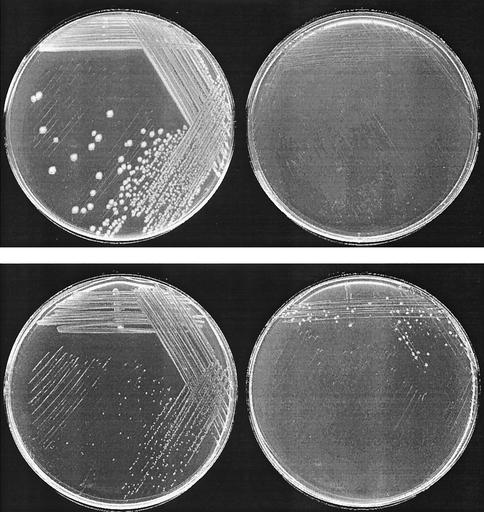

DapE can contribute to the utilization of Asp-Leu.

As shown in Fig. 6, the fully peptidase-deficient strain, TN5934, fails to grow on Asp-Leu as a leucine source. The dapE+ parent, TN5889, forms visible colonies in about 9 days. These colonies are tiny, but a few larger colonies are also observed. These larger colonies may be mutants expressing higher levels of DapE, but we have not characterized them further. TN5935 (pep/pDapE), however, grows quite well on Asp-Leu, yielding visible colonies in 24 h in the presence of 1 mM IPTG. This demonstrates that DapE can function as a significant peptidase in vivo when overproduced. In addition, it suggests that at least some of the enzyme in vivo must contain bound manganese.

FIG. 6.

Growth on Asp-Leu and as a leucine source. Shown counterclockwise from the top left are results for TN5307 (pep+/pSE380) at 24 h, TN5935 (pep/pDapE) at 24 h, TN5936 (dapE+/pSE380) at 9 days, and TN5934 (pep/pSE380) at 9 days.

DISCUSSION

The results reported in this paper show that DapE is an Mn2+-activated Asp-specific dipeptidase. Mutations in DapE lead to the loss of the Mn2+-dependent peptidase activity, overproduction of DapE leads to greatly elevated levels of the activity, and purified DapE hydrolyzes all N-terminal Asp dipeptides tested except Asp-Pro.

The observation that SDAP is a competitive inhibitor of Asp-Leu hydrolysis and vice versa strongly suggests that DapE uses the same active site to hydrolyze both SDAP and peptide substrates. From one perspective, it is perhaps not surprising that DapE can act as a peptidase as well as a desuccinylase: the two chemical reactions are basically identical (amide hydrolysis), and aspartate can be viewed as a structural analog of succinate, differing only by the presence of a charged alpha amino group. From the perspective of previous studies of the specificity of DapE, however, the discovery that it can hydrolyze Asp dipeptides is more surprising. Among a number of structural analogs of SDAP, Zn2+-activated DapE hydrolyzed only N-succinyl-l,d-diaminopimelate at a rate comparable to that of SDAP, and most other succinylated analogs of l,l-DAP were not hydrolyzed at all. DapE has therefore been considered a highly specific enzyme (21). It is perhaps even more surprising that, for its best peptide substrates, the enzymatic efficiency of DapE is almost as great as it is for its normal substrate, SDAP.

DapE belongs to the same structural family as several peptide-hydrolyzing enzymes, the M20 family (3). Crystal structures have been determined for two peptidases in this family: Pseudomanas carboxypeptidase G2 (CPG2) (29) and the S. enterica tripeptidase, peptidase T (13). Although these proteins share only 16% amino acid sequence identity, they have the same structural fold, and their active sites are nearly superimposable. The amino acids involved in metal binding are conserved between the two proteins and the geometric orientations of the ligands and metal ions in the active site are essentially superimposable. These ligands are conserved in DapE as well as in other related hydrolases, including the dipeptidase, PepD, and the N-acetyl ornithine deacetylase, ArgE. It seems likely, therefore, that the three-dimensional structure of DapE is very similar to those of CPG2 and PepT.

All of the enzymes in the M20 family can bind two divalent cations. One ion is tightly bound, usually requiring extensive dialysis in presence of chelators for its removal. The other metal is more loosely associated and can be removed by dialysis in the absence of chelators. In many cases, the loosely bound metal is lost during enzyme purification, and any one of a number of divalent metal ions can activate enzymes of this family lacking the weakly bound ion. Zn2+ is usually found in the tight binding site regardless of the metal ions present during purification, and it seems likely that this ion occupies this site in vivo. The nature of the cation in the loose binding site in vivo cannot usually be specified, nor can it be assumed that the ion that most efficiently activates catalysis in vitro is actually present in vivo. In the case of DapE, for example, the Co2+-activated enzyme is more active as a desuccinylase than enzyme containing any other ion, but it has been proposed that cytosolic enzymes likely do not use Co2+ in vivo, since Co2+ is insoluble in physiological concentrations of reduced glutathione (33). DapE purifies with Zn2+, and this Zn2+ remains bound after dialysis in chelators. Co2+ inhibits the Mn2+-activated hydrolysis of Asp peptides, suggesting they compete for the same exchangeable site. In addition, the Mn2+-activated enzyme loses its peptidase activity after dialysis in the absence of chelators but can be reactivated by the readdition of Mn2+. We believe that this evidence suggests that the form of DapE that is active as a peptidase contains Zn2+ in the tight binding site and Mn2+ in the low-affinity site.

We have considered two possibilities for the mechanistic basis for Mn2+ activation of peptide hydrolysis. Given the great specificity for Asp peptides, we thought it possible that there might be some direct interaction between the Asp residue of the substrate and the bound Mn2+. The observation that Asp-Ser inhibits the Co2+-activated hydrolysis of SDAP suggests to the contrary that Asp peptides do not require Mn2+ to bind to the active site. It seems more likely therefore that the architecture of the active site is subtly different, depending on which metal ion is present at the low-affinity site. It has been suggested that relatively minor differences in the coordination of metal ions at enzyme active sites may have significant consequences for enzyme specificity (1).

The presence of a single copy of the dapE gene in the absence of the other peptidase genes allows only very slow growth on Asp-Leu as a Leu source. It is likely that the level of DapE in such strains is very low, as evidenced by the 7,100-fold purification required to obtain pure DapE from E. coli extracts (21). Overproduction of DapE, however, leads to a clear growth phenotype. This observation establishes that DapE can function in vivo as a peptidase. We believe that growth on Asp-Leu conferred by DapE overproduction also reveals the in vivo metallated state of this enzyme. In order to contribute to growth, it must be present in the Mn2+-activated form. It is known that there are two Mn2+ transport systems in S. enterica and that these systems are capable of accumulating Mn2+ to concentrations of 100 μM under conditions in which its concentration in the medium is 50 nM (16). Considering the low affinity of DapE for Mn2+ and the clear growth phenotype, it seems likely that there is ample Mn2+ to bind and activate low-affinity targets. Mn2+ is nontoxic even when present at high concentrations and can actually benefit the cell by detoxifying reactive oxygen species (2, 4, 18). We therefore suggest that Mn2+ may play a more important role in the activation of metallohydrolases in vivo than previously recognized. Indeed, several previously characterized bimetallopeptide hydrolases (PepA, PepB, PepD, and PepT, for example) can be activated by Mn2+, and we intend to explore the effects of this cation on the specificities of these enzymes both in vitro and in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bill Metcalf, Jim Imlay, and Rachel Larsen for helpful discussions and insight. We also thank Rick Holz for generously providing us with N-succinyl-l,l-diaminopimelic acid and Barry Wanner for providing us with the genetic tools to perform λ Red recombinase genomic knockouts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott, J. J., J. Pei, J. L. Ford, Y. Qi, V. N. Grishin, L. A. Pitcher, M. A. Phillips, and N. V. Grishin. 2001. Structure prediction and active site analysis of the metal binding determinants in gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:42099-42107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Archibald, F. S., and I. Fridovich. 1982. The scavenging of superoxide radical by manganous complexes: in vitro. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 214:452-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett, A. J., N. D. Rawlings, and J. F. Woessner. 1998. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 4.Berlett, B. S., P. B. Chock, B. B. Yim, and E. R. Stadtman. 1990. Manganese(II) catalyzes the bicarbonate-dependent oxidation of amino acids by hydrogen peroxide and the amino acid-facilitated dismutation of hydrogen peroxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:389-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Born, T. L., R. Zheng, and J. S. Blanchard. 1998. Hydrolysis of N-succinyl-l, l-diaminopimelic acid by the Haemophilus influenzae dapE-encoded desuccinylase: metal activation, solvent isotope effects, and kinetic mechanism. Biochemistry 37:10478-10487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyen, A., D. Charlier, J. Charlier, V. Sakanyan, I. Mett, and N. Glansdorff. 1992. Acetylornithine deacetylase, succinyldiaminopimelate desuccinylase and carboxypeptidase G2 are evolutionarily related. Gene 116:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter, F. H., and J. M. Vahl. 1973. Leucine aminopeptidase (bovine lens). Mechanism of activation by Mg2+ and Mn2+ of the zinc metalloenzyme, amino acid composition, and sulfhydryl content. J. Biol. Chem. 248:294-304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter, T. H., and C. G. Miller. 1984. Aspartate-specific peptidases in Salmonella typhimurium: mutants deficient in peptidase E. J. Bacteriol. 159:453-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, G., T. Edwards, V. M. D'Souza, and R. C. Holz. 1997. Mechanistic studies on the aminopeptidase from Aeromonas proteolytica: a two-metal ion mechanism for peptide hydrolysis. Biochemistry 36:4278-4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conlin, C. A., K. Håkensson, A. Liljas, and C. G. Miller. 1994. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the cyclic AMP receptor protein-regulated Salmonella typhimurium pepE gene and crystallization of its product, an α-aspartyl dipeptidase. J. Bacteriol. 176:166-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gary, J. D., and S. Clarke. 1995. Purification and characterization of an isoaspartyl dipeptidase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270:4076-4087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Håkansson, K., and C. G. Miller. 2002. Structure of peptidase T from Salmonella typhimurium. Eur. J. Biochem. 269:443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Håkansson, K., A. H. Wang, and C. G. Miller. 2000. The structure of aspartyl dipeptidase reveals a unique fold with a Ser-His-Glu catalytic triad. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14097-14102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Javid-Majd, F., and J. S. Blanchard. 2000. Mechanistic analysis of the argE-encoded N-acetylornithine deacetylase. Biochemistry 39:1285-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kehres, D. G., A. Janakiraman, J. M. Slauch, and M. E. Maguire. 2002. SitABCD is the alkaline Mn2+ transporter of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 184:3159-3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, H., and W. N. Lipscomb. 1993. Differentiation and identification of the two catalytic metal binding sites in bovine lens leucine aminopeptidase by X-ray crystallography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:5006-5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozlov, Y., A. A. Kazakova, and V. V. Klimov. 1997. Changes in the redox potential and catalase actvity of Mn2+ ions during formation of Mn-bicarbonate complexes. Membr. Cell Biol. 11:115-120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen, R. A., T. M. Knox, and C. G. Miller. 2001. Aspartic peptide hydrolases in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 183:3089-3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassy, R. A. L., and C. G. Miller. 2000. Peptidase E, a peptidase specific for N-terminal aspartic dipeptides, is a serine hydrolase. J. Bacteriol. 182:2536-2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin, Y. K., R. Myhrman, M. L. Schrag, and M. H. Gelb. 1988. Bacterial N-succinyl-l-diaminopimelic acid desuccinylase. Purification, partial characterization, and substrate specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 263:1622-1627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makarova, K. S., and N. V. Grishin. 1999. The Zn-peptidase superfamily: functional convergence after evolutionary divergence. J. Mol. Biol. 292:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maniatis, T., E. F. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1982. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 24.Mathew, Z., T. M. Knox, and C. G. Miller. 2000. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium peptidase B is a leucyl aminopeptidase with specificity for acidic amino acids. J. Bacteriol. 182:3383-3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller, C. G. 1996. Protein degradation and proteolytic modification, p. 938-954. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed., vol. 1. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 26.Miller, C. G., A. M. Kukral, J. L. Miller, and N. R. Movva. 1989. pepM is an essential gene in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 171:5215-5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller, C. G., and K. Mackinnon. 1974. Peptidase mutants of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 120:355-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prescott, J., F. Wagner, B. Holmquist, and B. Vallee. 1983. One hundred fold increased activity of Aeromonas aminopeptidase by sequential substitutions with Ni(II) or Cu(II) followed by zinc. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 114:646-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowsell, S., R. A. Pauptit, A. D. Tucker, R. G. Melton, D. M. Blow, and P. Brick. 1997. Crystal structure of carboxypeptidase G2, a bacterial enzyme with applications in cancer therapy. Structure 5:337-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmieger, H. 1972. Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol. Gen. Genet. 119:75-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sträter, N., L. Sun, E. R. Kantrowitz, and W. N. Lipscomb. 1999. A bicarbonate ion as a general base in the mechanism of peptide hydrolysis by dizinc leucine aminopeptidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:11151-11155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogel, H. J., and D. M. Bonner. 1956. Acetylornithinase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J. Biol. Chem. 218:97-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker, K. W., and R. A. Bradshaw. 1998. Yeast methionine aminopeptidase I can utilize either Zn2+ or Co2+ as a cofactor: a case of mistaken identity? Protein Sci. 7:2684-2687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]