Abstract

The cell wall of the environmental pathogen Mycobacterium avium is important to its virulence and intrinsic antimicrobial resistance. To identify genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis, “transposome” insertion libraries were screened for mutants with altered colony morphology on medium containing the lipoprotein stain Congo red. Nineteen such mutants were isolated and mapped, including 10 with insertions in a functional island of cell wall biosynthetic genes that spans approximately 40 kb of the M. avium genome.

The Mycobacterium avium complex is an environmental pathogen that causes serious disease in susceptible individuals (10, 14, 15, 21). The most well-characterized member of the group is M. avium subsp. avium. The virulence and intrinsic multidrug resistance of this pathogen have been attributed in part to its unique cell wall (6, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20). The M. avium subsp. avium cell wall is a complex array of hydrocarbon chains containing the arabinogalactan-peptidoglycan-mycolic acid core found in all mycobacteria, surrounded by a second electron-dense layer made up, in part, of serovar-specific glycopeptidolipids (ssGPL) found only in M. avium complex (2-4, 15, 22). ssGPL consist of core nonspecific GPL (nsGPL) common to many environmental mycobacteria, modified by the addition of serovar-specific oligosaccharide side chains.

Most clinical isolates of M. avium subsp. avium form multiple colony-type variants (morphotypes). Analysis of the irreversible switch that results in the rough colony type has yielded good information about the genetics of cell wall biosynthesis (2-4, 8). Rough mutants fall into two categories: those that lack all traces of GPL and those that produce a lipopeptide core of GPL that is not glycosylated. Both categories result from spontaneous deletions within a cluster of genes involved in ssGPL biosynthesis. The ssGPL gene cluster, named ser2, is 17 to 27 kb long, depending upon polymorphisms related to insertion elements (2, 3, 8).

Additional morphotypic switches in M. avium subsp. avium are less well understood. Smooth transparent variants are more virulent and more drug resistant than their smooth opaque counterparts (15). A separate switch, termed red-white, becomes visible when clinical isolates are grown on agar media containing the lipoprotein stain Congo red (CR) (6, 7, 17). Compared to red variants, white variants are more resistant to multiple antibiotics in vitro, more common in patient samples, and more virulent in disease models (6, 17).

We have taken a mutational approach to identifying genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis and colony morphotype. Genetic analysis of M. avium subsp. avium is challenging due to the organism's low growth rate, genetic instability, and intrinsic multidrug resistance. Transposon mutagenesis, a powerful tool for analyzing gene function, has not previously been applied to M. avium subsp. avium (a system was reported for M. avium subspecies paratuberculosis, a more stable subspecies of M. avium) (11). Therefore, we developed and applied a protocol for random “transposome” mutagenesis of M. avium subsp. avium. The commercial EZ::TN 〈KAN-2〉 system (Epicentre, Madison, Wis.) has a 1.2-kb transposon-like DNA element derived from Tn903. It carries a Kmr gene but no transposase gene. A transposome is a complex of this element with the transposase that recognizes its terminal inverted repeats (9). When the complex is introduced into bacterial cells, the element integrates at random sites in the host genome.

Cells were grown on Middlebrook 7H10 agar with albumin enrichment, glycerol, and CR (7). Stable red opaque (RO) and white opaque (WO) clones of M. avium subsp. avium clinical isolate HMC02 (7) were mutagenized. M. avium subsp. avium cells were prepared for electroporation by glycine treatment as described previously (12). Suspensions of treated cells in 10% glycerol (100 μl) were mixed with 20 ng (1 μl) of EZ::TN 〈KAN-2〉 Tnp transposome complex. Each suspension was transferred to a 0.2-cm-electrode gap cuvette and electroporated with a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser at parameters of 2.5 kV, 1,000 Ω, and 25 μF. Middlebrook 7H9 broth with albumin-dextrose-catalase enrichment (1 ml) was added. Cells were transferred to a culture tube, incubated for 24 h (one doubling time) at 37°C, and plated onto Middlebrook 7H10 agar with albumin enrichment, glycerol, and CR plates containing 100 μg of kanamycin per ml. Plates were incubated for 3 to 4 weeks at 37°C. CR staining and colony morphotype were used to identify mutations in genes involved in cell wall biosynthesis.

When the RO variant was mutagenized, ≥85% of Kmr colonies were found by PCR analysis to carry the transposome element. Southern blot analysis of 13 randomly chosen clones showed that each insertion was in a separate genomic site. Mutagenesis of WO, red transparent, and white transparent clones was less efficient than mutagenesis of RO clones, possibly because of barriers to DNA uptake (data not shown).

Approximately 2,500 RO colonies mutagenized in five separate procedures and 530 WO colonies mutagenized in two separate procedures were screened for altered colony morphology, including rough appearance and reduced CR staining. Approximately 45 such mutants were picked and stored. Eleven rough mutants and eight CR staining (“colortype”) mutants were subjected to further analysis. Genomic regions adjoining transposome insertions were amplified by arbitrary-primer PCR (18). Purified PCR products were submitted for automated sequencing at the Seattle Biomedical Research Institute. The Unfinished Microbial Genomes searching tool at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) website (http://tigrblast.tigr.org/ufmg/) was used to locate the sequences within the draft M. avium subsp. avium strain 104 genome sequence. Regions of 2 to 3 kb surrounding the insertion sites were then analyzed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and the ORF Finder tool at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to identify sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant database that are closely homologous to open reading frames (ORFs) disrupted by transposome insertions.

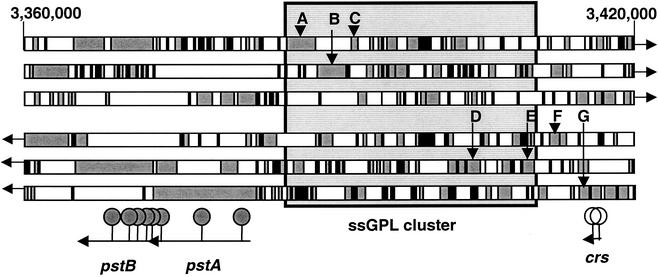

Rough mutant colonies were identical in appearance to those of the Rg-0 and Rg-4 mutants of M. avium subsp. avium strain 2151, which synthesize no ssGPL (2-4). Six rough mutants derived from the RO parent strain and two derived from the WO parent strain had insertions into a pair of neighboring genes, pstA and pstB (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Both genes are large (10,247 bp and 7,658 bp, respectively) and code for putative peptide synthetases. They read in the same direction and are separated by less than 18 bp in M. avium subsp. avium strain 2151 (GenBank accession number AF143772) as well as in the genome sequence of M. avium subsp. avium strain 104 (www.tigr.org). They may represent a single transcriptional unit.

TABLE 1.

Rough mutants of strain HMC02 generated by transposome mutagenesis

| Mutant | Parent morphotype | Mutant morphotype | GenBank accession no. | Description of closest homolog to disrupted ORF (expect value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRg-1 | RO | Rough | AAD44233 | M. avium peptide synthetase PstA (0.0) |

| RRg-2 | RO | Rough | AAD44234 | M. avium peptide synthetase PstB (0.0) |

| RRg-3 | RO | Rough | H70555 | M. tuberculosis probable transmembrane protein RV1159 (1e-176) |

| RRg-4 | RO | Rough | NP_336573 | M. tuberculosis probable polyketide synthase (0.0) |

| RRg-5 | RO | Rough | NP_216593 | M. tuberculosis hypothetical protein Rv2077c (7e-60) |

| RRg-6 | RO | Rough | AAD44234 | M. avium peptide synthetase PstB (0.0) |

| RRg-B | RO | Rough | AAD44234 | M. avium peptide synthetase PstB (0.0) |

| RRg-D | RO | Rough | AAD44234 | M. avium peptide synthetase PstB (0.0) |

| RRg-G | RO | Rough | AAD44233 | M. avium peptide synthetase PstA (0.0) |

| WRg-1 | WO | Rough | AAD44234 | M. avium peptide synthetase PstB (0.0) |

| WRg-2 | WO | Rough | AAD44233 | M. avium peptide synthetase PstA (0.0) |

FIG. 1.

Map of the 40,000-bp region of the M. avium subsp. avium strain 104 genome surrounding the GPL cluster. The six bars are ORF Finder results, with the shaded areas representing ORFs. At the top are position numbers within the M. avium subsp. avium genome sequence available at the time of this publication (www.tigr.org). The large shaded rectangle marks the ssGPL cluster identified previously (2-4, 8). This region was located within the genome sequence by searching for genes situated near the two borders of the ssGPL region (GenBank accession number AF143772), namely, tmtpB (A), tmtpC (B), drrA (C), rtfA (D), mtfA (E), bacteriophage MX1 A protein-like protein (F), and unknown protein AAD44199.1 (G). Shown at the bottom are the approximate positions of genes discussed in the text and the positions of EZ::TN insertions in rough mutants (filled markers) and colortype mutants RW1 and RW2 (open markers).

Immediately upstream of pstA in strains 2151 and 104 is the ssGPL (ser2) cluster identified previously (2-4, 8) (Fig. 1). The integrity of this region was not assessed in the rough mutants, nor could we rule out the possibility that mutations elsewhere in the genome might have caused the rough morphotype. However, eight separate rough mutants isolated in five independent mutagenesis procedures had insertions into pstA or pstB, each at a separate site within the two contiguous genes. Therefore, it is likely that these genes are directly involved in the mutant phenotype. The possibility of polar effects on downstream genes cannot yet be excluded; however, no significant downstream ORFs were observed within 550 bp downstream of pstB in the genomes of strains 104 and 2151.

The mps gene of M. smegmatis codes for a peptide synthetase involved in the synthesis of the core lipopeptide of nsGPL (5). A BLAST comparison showed that portions of mps are strongly homologous to pstA and pstB of M. avium subsp. avium (expect value, 0.0). Mps has four modules distributed along its length, each containing an amino acid recognition and adenylation domain (5). The first three modules also have racemase domains that presumably isomerize the first three amino acids of the core GPL tetrapeptide. This supposition is consistent with the structure of the tetrapeptide in M. smegmatis as well as M. avium subsp. avium (fatty acyl-NH-d-phenylalanine-d-allothreonine-d-alanine-l-alaninol-O-[Me3]rhamnose). Given that the two species have identical core GPL, it was unexpected to find two peptide synthetases in M. avium subsp. avium versus only one in M. smegmatis. However, comparison of PstA, PstB, and Mps suggested that the difference is one of organization rather than function. Mps has 5,990 amino acids and is about equal in size to PstA (2,552 amino acids) and PstB (3,445 amino acids) combined. Structural motifs within the three proteins were analyzed using the Multiple EM for Motif Elicitation tool (1). The four modules identified previously in Mps (5), each containing amino acid recognition, modification, and (in the first three modules) racemase domains, were distributed two apiece in PstA and PstB. Racemase domains were present in both modules of PstA and in the first module of PstB. Thus, it appears that PstA plus PstB of M. avium subsp. avium and Mps of M. smegmatis perform similar functions and differ from each other mainly by virtue of the stop and start codons situated between the second and third modules in M. avium subsp. avium.

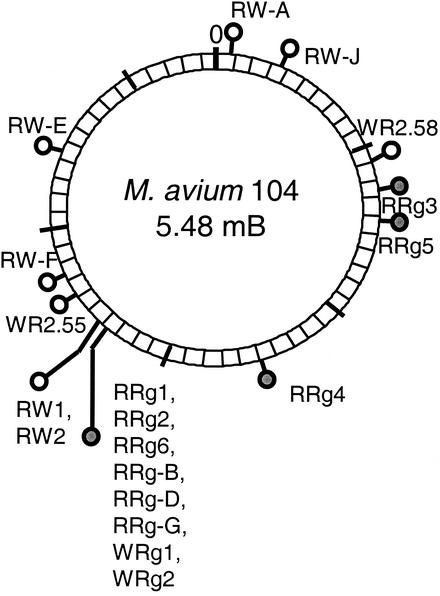

In addition to the eight pstA-pstB mutants, three rough mutants derived from the RO parent clone (RRg-3, RRg-4, and RRg-5) had insertions into putative genes that map elsewhere in the genome of strain 104 (Fig. 2). Each of these genes was disrupted in only one mutant, so their direct role in colony morphotype must be considered tentative.

FIG. 2.

Positions of EZ::TN insertions in the M. avium subsp. avium genome. The diagram represents the 5,475,491-bp contig that constitutes the M. avium subsp. avium strain 104 genome sequence at the time of this publication (www.tigr.org). Filled symbols mark the positions of EZ::TN insertions in rough mutants. Open symbols mark the positions of EZ::TN insertions in colortype mutants.

Mutagenized smooth colonies were also examined for altered CR staining characteristics. Two CR-binding (red) colonies were seen among the 530 mutagenized white colonies. Six non-CR-binding (white) colonies were seen among approximately 2,500 mutagenized red colonies (Table 2). The appearance of eight colortype mutants among ∼3,000 mutagenized RO and WO cells was well above the expected background of spontaneous red-white colony type switches (6).

TABLE 2.

Colortype mutants of strain HMC02 generated by transposome mutagenesisa

| Mutant | Parent morphotype | Mutant morphotype | CR binding (A488/OD600)b | GenBank accession no. | Description of closest homolog to disrupted ORF (expect value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RO | NA | NA | 0.471 ± 0.004 | Parent strain | |

| WO | NA | NA | 0.008 ± 0.001 | Parent strain | |

| RW1 | RO | WO | 0.026 ± 0.001 | AAF05992 | M. smegmatis acetyltransferase (1e-122) (65% identity) |

| RW2 | RO | WO | 0.055 ± 0.006 | AAF05992 | M. smegmatis acetyltransferase (1e-122) (65% identity) |

| RW-A | RO | WO | 0.367 ± 0.003 | NP_215371 | M. tuberculosis hypothetical protein RV0856 (5e-54) |

| RW-E | RO | WO | 0.194 ± 0.001 | CAA17111 | M. tuberculosis probable isocitrate dehydrogenase Icd1 |

| RW-F | RO | WO | 0.146 ± 0.013 | X91407 | M. tuberculosis SOS regulatory protein LexA (7e-48) |

| RW-J | RO | WO | 0.182 ± 0.001 | ≈0.8-kb ORF, no homologs detected | |

| WR2.55 | WO | RO | ND | AAK45292 | M. tuberculosis polyketide synthase (0.0) |

| WR2.58 | WO | RO | ND | NP_217098 | M. tuberculosis probable peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase PpiB (1e-128) |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; ND, not determined; OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

CR binding was quantified by a previously described procedure (7) that yields a relative value for CR binding defined as the absorbance at 488 nm of CR extracted from stained cells and normalized to the optical density at 600 nm of the cell suspension. Means and standard deviations of results from triplicate samples are shown.

Two red-to-white colortype mutants had identical phenotypes. The mutants, designated RW1 and RW2, bound very little CR relative to the parent strain (Table 2). Both mutants had insertions into a gene belonging to a family of acetyltransferases involved in glycolipid synthesis. This gene, which we named crs for CR staining, maps adjacent to the ssGPL cluster, opposite the pst genes (Fig. 1). The two mutants were independently generated in separate mutagenesis procedures, and their insertion sites were separated by approximately 700 bp within the crs gene. Therefore, they were not siblings and it is unlikely that they were related by virtue of transpositional bias.

Four additional mutants of the RO parent strain exhibited reduced CR binding. In addition, two mutants of the WO parent strain exhibited increased CR binding, such that they were indistinguishable from the RO parent strain. All of these mutants had insertions into putative genes that map outside the vicinity of the ssGPL cluster in strain 104 (Fig. 2). Each of these genes was disrupted in only one mutant, so their direct role in determining colony morphotype must be considered tentative. Further mutagenesis and genetic complementation analysis are needed to confirm the roles of these genes in colortyping.

Conclusions.

The GPL cluster defined by previous studies (2-4, 8) covers 17 to 27 kb of DNA centered around base 3400000 of the draft M. avium subsp. avium strain 104 genome sequence. The size of the region varies between strains because of insertion elements that seem to cluster here. The addition of the pstA and pstB genes, along with intervening sequences, extends the GPL cluster by >17 kb. Combined with the neighboring crs gene, this region of the genome appears to be dedicated to cell wall synthesis.

The red-white morphotypic switch, visible among colonies grown on CR agar, is significant because it occurs naturally in most M. avium subsp. avium clinical isolates and affects virulence as well as drug resistance (6, 17). Disruption of a single gene, crs, was sufficient to decrease CR binding by >90%. The residual CR binding exhibited by crs mutants (Table 2) and the fact that we isolated other colortype mutants that had insertions elsewhere in the genome suggest that other genes in addition to crs are also involved in CR binding. The Crs protein is a putative acetyltransferase similar to proteins involved in glycolipid synthesis in other mycobacteria. It may catalyze the synthesis of one or more major CR-binding ligands. Alternatively, mutations in crs may perturb the cell wall in such a way as to elicit the synthesis of unknown permeability barriers that reduce CR uptake or block access to CR-binding ligands.

Transposome mutagenesis and CR staining allowed us to assign functions to three previously uncharacterized genes in the GPL region of the M. avium subsp. avium genome and tentatively to five more genes. The transposome mutagenesis system has several advantages for use in M. avium subsp. avium. Its high efficiency of transposition, activated once the complex is introduced into the cell, appears to compensate for the organism's low efficiency of DNA uptake. The EZ::TN element, which lacks its own transposase gene, is stable once it is inserted into the host genome. The transposome system might become a valuable tool for genetic analysis of these environmental pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Julia Inamine and Delphi Chatterjee for providing strains, lipid samples, and helpful advice and to David Sherman for critical review of the manuscript. Preliminary M. avium genome sequence data were obtained from TIGR website at http://www.tigr.org. Sequencing of the M. avium genome is being carried out by TIGR with support from the National Institutes of Health.

This work was supported by grant AI25767 from the National Institutes of Health and grant G8E10521 from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. J.-P.L. was supported in part by NIH training grant T32AI07509.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey, T. L., and M. Gribskov. 1998. Combining evidence using p-values: application to sequence homology searches. Bioinformatics 14:48-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belisle, J. T., K. Klaczkiewicz, P. J. Brennan, W. R. Jacobs, and J. M. Inamine. 1993. Rough morphological variants of Mycobacterium avium. J. Biol. Chem. 268:10517-10523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belisle, J. T., L. Pascopella, J. M. Inamine, P J. Brennan, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1991. Isolation and expression of a gene cluster responsible for biosynthesis of the glycopeptidolipid antigens of Mycobacterium avium. J. Bacteriol. 173:6991-6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belisle, J. T., M. R. McNeil, D. Chatterjee, J. M. Inamine, and P. J. Brennan. 1993. Expression of the core lipopeptide of the glycolipid surface antigens in rough mutants of Mycobacterium avium. J. Biol. Chem. 268:10510-10516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billman-Jacobe, H., M. J. McConville, R. E. Haites, S. Kovacevic, and R. L. Coppel. 1999. Identification of a peptide synthetase involved in the biosynthesis of glycopeptidolipids of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 33:1244-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cangelosi, G. A., C. O. Palermo, and L. E. Bermudez. 2001. Phenotypic consequences of red-white colony type variation in Mycobacterium avium. Microbiology 147:527-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cangelosi, G. A., C. O. Palermo, J. P. Laurent, A. M. Hamlin, and W. H. Brabant. 1999. Colony morphotypes on Congo red agar segregate along species and drug susceptibility lines in the Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex. Microbiology 145:1317-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckstein, T. B., J. M. Inamine, M. L. Lambert, and J. T. Belisle. 2000. A genetic mechanism for deletion of the ser2 gene cluster and formation of rough morphological variants of Mycobacterium avium. J. Bacteriol. 182:6177-6182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goryshin, I. Y., J. Jendrisak, L. M. Hoffman, R. Meis, and W. S. Reznikoff. 2000. Insertional transposon mutagenesis by electroporation of released Tn5 transposition complexes. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:97-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guthertz, L. S., B. Damsker, E. J. Bottone, E. G. Ford, M. F. Thaddeus, and M. J. Janda. 1989. Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare infection in patients with and without AIDS. J. Infect. Dis. 160:1037-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris, N. B., Z. Feng, X. Liu, S. L. G. Cirillo, J. D. Cirillo, and R. G. Barletta. 1999. Development of a transposon mutagenesis system for Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 175:21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatfull, G. F., and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 2000. Molecular genetics of mycobacteria. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 13.Heifets, L. 1996. Susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium avium complex isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1759-1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horsburgh, C. R., Jr., J. Gettings, L. N. Alexander, and J. L. Lennox. 2001. Disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus, 1985-2000. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33: 1938-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inderlied, C. B., C. A. Kemper, and L. E. M. Bermudez. 1993. The Mycobacterium avium complex. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 6:266-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarlier, V., and H. Nikaido. 1994. Mycobacterial cell wall: structure and role in natural resistance to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 123:11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukherjee, S., M. Petrofsky, K. Yaraei, L. E. Bermudez, and G. A. Cangelosi. 2001. The white morphotype of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare is common in infected humans and virulent in infection models. J. Infect. Dis. 184: 1480-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Initiation of biofilm formation is Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signaling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 28:449-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plum, G., and J. E. Clark-Curtiss. 1994. Induction of Mycobacterium avium gene expression following phagocytosis by human macrophages. Infect. Immun. 62:476-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portillo-Gomez, L., J. Nair, D. A. Rouse, and S. L. Morris. 1995. The absence of genetic markers for streptomycin and rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium avium complex strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 36:1049-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Von Reyn, C. F., J. N. Maslow, T. W. Barber, J. O. I. Falkinham, and R. D. Arbeit. 1994. Persistent colonisation of potable water as a source of Mycobacterium avium infection in AIDS. Lancet 343:1137-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wayne, L. G., R. C. Good, A. Tsang, R. Butler, D. Dawson, D. Groothuis, W. Gross, J. Hawkins, J. Kilburn, and M. Kubin. 1993. Serovar determination and molecular taxonomic correlation in Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, and Mycobacterium scrofulaceum: a cooperative study of the international working group on mycobacterial taxonomy. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43:482-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]