Abstract

In an attempt to improve stress tolerance of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants, an expression vector containing an Arabidopsis C-repeat/dehydration responsive element binding factor 1 (CBF1) cDNA driven by a cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter was transferred into tomato plants. Transgenic expression of CBF1 was proved by northern- and western-blot analyses. The degree of chilling tolerance of transgenic T1 and T2 plants was found to be significantly greater than that of wild-type tomato plants as measured by survival rate, chlorophyll fluorescence value, and radical elongation. The transgenic tomato plants exhibited patterns of growth retardation; however, they resumed normal growth after GA3 (gibberellic acid) treatment. More importantly, GA3-treated transgenic plants still exhibited a greater degree of chilling tolerance compared with wild-type plants. Subtractive hybridization was performed to isolate the responsive genes of heterologous Arabidopsis CBF1 in transgenic tomato plants. CATALASE1 (CAT1) was obtained and showed activation in transgenic tomato plants. The CAT1 gene and catalase activity were also highly induced in the transgenic tomato plants. The level of H2O2 in the transgenic plants was lower than that in the wild-type plants under either normal or cold conditions. The transgenic plants also exhibited considerable tolerance against oxidative damage induced by methyl viologen. Results from the current study suggest that heterologous CBF1 expression in transgenic tomato plants may induce several oxidative-stress responsive genes to protect from chilling stress.

Many tropical and subtropical crops, e.g. tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum), bell pepper (Capsicum annuum), and avocado (Persea americana), are sensitive to cold (Saltveit and Morris, 1990). Because of the susceptibility to chilling, the growing season of the crops is limited, and the quality of produce is affected. On the other hand, plants originating in the temperate zone are generally more tolerant to cold and have protective processes, such as cold acclimation (Thomashow, 1999). It has been demonstrated that the ability to cold acclimate is related to specific signal transduction pathways resulting in the activation of many cold-regulated (COR) genes (Thomashow, 1998).

The COR genes, including RD29A (COR78), COR15a, KIN1, and COR6.6 of Arabidopsis, are inducible in response to cold treatment, ABA, and water-deficit stress (Thomashow, 1998). The C-repeat (CRT) and dehydration responsive element (DRE)-related motifs have been reported in the promoter sequences of these genes (Horvath et al., 1993; Nordin et al., 1993; Baker et al., 1994; Wang et al., 1995). The CRT/DRE binding factor 1 (CBF1) has been isolated using a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) one-hybrid system (Stockinger et al., 1997). Overexpression of CBF1 can induce COR gene expression and result in increased tolerance to freezing temperature treatment without cold-acclimation (Jaglo-Ottosen et al., 1998). Arabidopsis CBF1 is also heterologously effective in canola (Brassica napus) plants, improving freezing tolerance and activating the expression of COR homologous genes at nonacclimating temperature (Jaglo et al., 2001). In addition, Arabidopsis DRE binding factor genes, DREB1A and DREB2A, containing the EREBP/AP2 DNA-binding domain (Stockinger et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1998) operate in two cellular signal transduction pathways, i.e. in response to low-temperature and water deficit, respectively (Liu et al., 1998). Results from these studies suggest that these newly identified gene products including, CBF1, DREB1A, and DREB2A, play a role as a main switch in the control of stress responses.

The availability of low-temperature-regulated genes from wheat (Triticum aestivum) has been invaluable in studies of freezing stress in the Gramineae family (Sarhan et al., 1997). It has been shown that the wheat WCS120/COR39 gene, containing several CCGAC sequences like CRT/DREs in its promoter, is cold inducible in those monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants tested (Ouellet et al., 1998). Studies using chilling-tolerant and chilling-sensitive species have revealed that all tested cereal plants contain homologs of the low-temperature-regulated wheat genes in their genomes (Sarhan et al., 1997). The CBF1 homologs have recently been isolated from wheat, rye (Secale cereale), canola, and tomato (Jaglo et al., 2001). COR homologs are also identified in these plant species except for tomato, showed responsiveness to their CBF1 homologs (Jaglo et al., 2001), and were found to be cold responsive. Tomato is generally considered a chilling-sensitive plant (Saltveit and Mangrich, 1998). Genetic engineering technology has already been effectively used as a relatively fast, precise, and often cost-effective means of improving stress-tolerance in certain plant species (Holmberg and Bulow, 1998; Bajaj et al., 1999; Zhang et al., 2000; Zhang and Blumwald, 2001). It would be interesting to evaluate the effect of overexpressing CBF1 protein in a chilling-sensitive plant. In this study, we show that constitutive expression of the heterologous Arabidopsis CBF1 gene in transgenic tomato plants can effectively regulate genes involved with stress responses, such as CATALASE1, and confers stress tolerance to the transgenic tomato.

RESULTS

Identification of Transgenic Tomato Plants That Overexpress CBF1

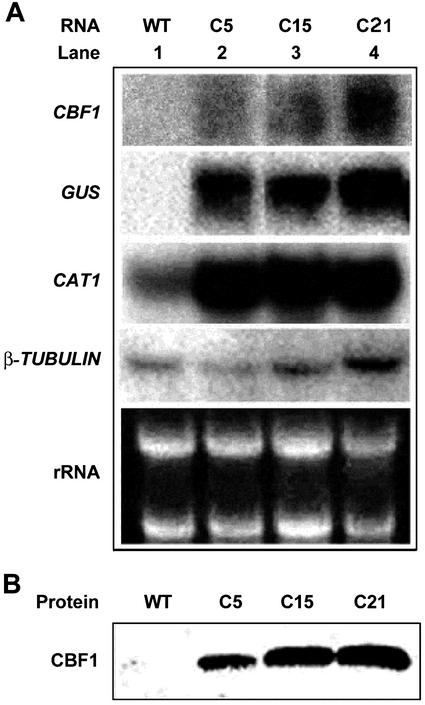

To evaluate the effect of overexpression of CBF in tomato plants, an Arabidopsis CBF1 and the marker gene β-glucuronidase (GUS) were transferred into the tomato genome using Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. After selection on kanamycin-containing medium, the putative transgenic tomato plants were further identified by GUS histochemical staining assays to screen for transgenic tomato plants expressing the transgenes. Twenty-two independent lines were obtained, and Southern-blot analysis showed that 35S:CBF1 transgene was integrated into the genome of the transformed plants (data not shown). Northern-blot analysis was performed to evaluate the 35S:CBF1 transgene expression in three transgenic tomato lines (Fig. 1A). CBF1 and GUS RNA transcripts were detected only in the transgenic lines (Fig. 1A), whereas the amount of β-TUBULIN RNA was similar in the transgenic and wild-type tomato plants (Fig. 1A). These plants were further characterized by western-blot analysis of protein extracts from the leaf tissues with polyclonal antibodies raised against the recombinant CBF1 protein (Fig. 1B). The antibodies recognized a protein of approximately 25-kD molecular mass in the samples from the transgenic tomato plants, whereas there was no signal in the wild-type plants. These results indicated that the transgene was successfully expressed transcriptionally and translationally in the transgenic plants. However, using Arabidopsis COR47, KIN1, and COR15a cDNA as probes, we did not detect any corresponding COR homologous gene expression in wild-type or transgenic tomato plants even in low-stringent hybridization conditions (data not shown). Neither did we observe any accumulation in transgenic tomato plants of the tomato dehydrin TAS14 (data not shown). Tomato dehydrin TAS14 is responsive to salinity, ABA, and mannitol (Godoy et al., 1990, 1994; Parra et al., 1996).

Figure 1.

RNA and protein analyses of the transgenic plants overexpressing CBF1. A, Total RNA (10 μg) was extracted from wild type (WT; lane 1) and three lines of transgenic tomatoes overexpressing CBF1 (C5, C15, and C21). cDNA probes used were 32P-labeled Arabidopsis CBF1, GUS, tomato CATALASE 1 (CAT1), and β-TUBULIN. B, Detection of the CBF1 protein by western-blot analysis in leaf protein extracts (20 μg per lane) of WT and the transgenic tomato plants (C5, C15, and C21).

Transgenic Tomatoes Exhibited Enhanced Chilling Tolerance But Not Freezing Tolerance

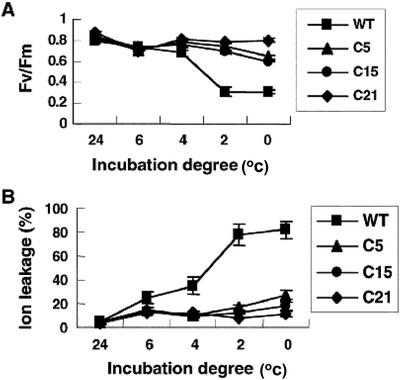

Because overexpression of CBF1 in Arabidopsis confers freezing tolerance, we were interested to know whether CBF1 has a similar effect on transgenic tomato plants. We found that neither transgenic nor wild-type plants were able to survive −2°C for 2 d followed recovery at 24°C. However, the transgenic plants exhibited enhanced chilling tolerance compared with wild-type plants. Photosynthesis efficiency as measured by light-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm) and ion leakage was measured to reflect the level of cellular damage after chilling treatment at various temperature (0°C, 2°C, 4°C, 6°C, or 24°C) for 7 d. The Fv/Fm ratio decreased in the wild-type plants after 3 d at 2°C and 0°C, however, the transgenic plants appeared to be less affected (Fig. 2A). Cold stress also caused severe ion leakage in the wild-type plants, whereas the transgenic plants were much less affected (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of CBF1 enhances tomato chilling tolerance. Tomato T1 plants were exposed to various temperatures (24°C, 6°C, 4°C, 2°C, and 0°C) for 7 d and a photoperiod of 16 h. Fv/Fm values (A) and percent leakage of ions (B) were measured. Results were obtained from an average of five measurements with less than 5% sd.

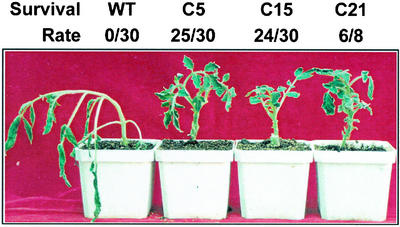

After treatment at 0°C for 1 d, leaves of the wild-type plants became wilted and curled. However, after recovery at 24°C from chilling treatment, young leaves of the wild-type plants resumed vigorous growth. To estimate the survival rate after cold treatment, we decide to extend the time of low-temperature treatment (0°C) to 7 d, then returned the plants to 24°C for recovery. The transgenic tomatoes were more tolerant to the chilling treatment without showing severe stress symptoms, whereas virtually all leaves of the wild-type plants became wilted and curled (Fig. 3). All of the wild-type plants eventually died, whereas 83.3%, 80%, and 75% of C5, C15, and C21 plants survived, respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Transgenic tomato plants overexpressing CBF1 display high level of tolerance to chilling stresses. A wild-type (WT) plant and three transgenic plants (C5, C15, and C21) were incubated at 0°C for 2 d. The photograph shows whole plants. Leaves of C5, C15, and C21 did not significantly curl and wilt, a sign of tolerance shown in the photograph. For survival rate test, WT, C5, C15, and C21 were incubated at 0°C for 7 d and returned to 24°C for 5 d. Numbers of surviving plants per total number of tested plants are indicated at the top of the image.

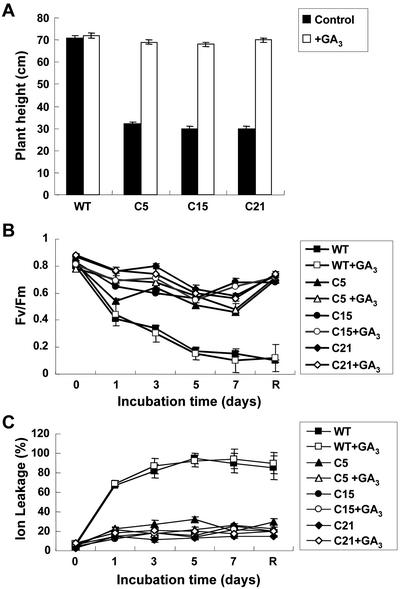

CBF1 Transgenic Tomatoes Exhibited Dwarf Phenotype That Can Be Overcome by Exogenous GA3 Treatment

When comparing the phenotypes of the transgenic tomato plants with those of the wild-type plants, severe growth retardation of the transgenic tomato plants was observed. All transgenic plants were considerably shorter than the wild-type plants (Fig. 4A). The average height of various transgenic plants was less than 50% of that of the wild-type plant, due to shorter internodes in the transgenic plants. We also observed a significant reduction of the number of fruit and seed set in transgenic plants under normal condition. Because gibberellin (GA) content has been shown to correlate with internode length (Ross et al., 1989), we were interested to know whether application of GA could overcome the dwarf phenotype of the transgenic plants. Application of GA3 to the transgenic tomatoes permitted essentially normal height growth (Fig. 4A). These results suggested that the heterologous CBF1 protein may affect the genes for hormone production that are involved in growth.

Figure 4.

Growth retardation of CBF1 transgenic plants can be recovered by treatment with exogenous GA3, without affecting chilling tolerance. The average height (A) of each line grown for 60 d was measured. Three-week-old wild-type and transgenic T1 tomato plants were treated with GA3 or buffer (control) three times within 1 week, and the height was measured after treatment for 39 d. After GA3 treatment, whole plants were incubated at 0°C for 1, 3, 5, and 7 d, and then the Fv/Fm values (B) and percent leakage of ions (C) were measured. After incubation at 0°C for various time, the wild-type and transgenic tomato plants were transferred to room temperature for another 5 d. The results are an average of seven measurements with less than 5% sd.

Chilling Tolerance of Transgenic Tomato Plants Is Not Affected by Exogenous GA3 Treatment

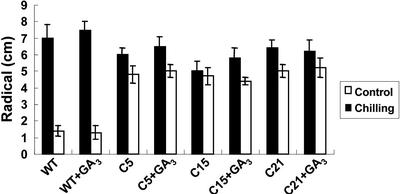

After GA3 treatment, plants were incubated at 0°C for various times (1, 3, 5, and 7 d), and ion leakage and Fv/Fm value were measured (Fig. 4, B and C). After recovery from chilling (0°C), the percent leakage of ions and Fv/Fm value were less affected in transgenic tomato plants, despite GA3 treatment, than wild type (Fig. 4, B and C). There was no discernible effect of GA3 treatment on any of the stress-resistance parameters tested, regardless of genotype (Fig. 4, B and C). The results showed that chilling tolerance of transgenic tomato plants was not affected by application of exogenous GA3. Moreover, after recovered from 5 d of storage at 2°C, the radical growth of wild-type seedlings was significantly reduced compared with those without cold treatment (Fig. 5). However, the T2 CBF1 transgenic seedlings were able to ameliorate the growth inhibition resulting from chilling treatment with or without GA3 pretreatment (Fig. 5). These results also showed that chilling tolerance of transgenic tomato T2 seedlings was not affected by the application of exogenous GA3.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of CBF1 conferred chilling tolerance in the transgenic tomato T2 seedlings. Chilling tolerance was expressed by radical elongation assay as described in “Materials and Methods.” The results are an average of 10 to 15 measurements with less than 5% sd.

Constitutive Activation of Catalase Gene in Transgenic Tomatoes

Overexpression of CBF1 can induce expression of COR genes in Arabidopsis (Jaglo-Ottosen et al., 1998). To see whether overexpression of CBF1 could induce the expression of COR homologs in tomato, we performed northern-blot analysis of the transgenic plants by employing Arabidopsis COR genes as probes. RNA transcripts from transgenic tomato plants did not cross-hybridize to the Arabidopsis COR47, KIN1, and COR15a even in low-stringent hybridization conditions (data not shown). These results suggested that the increased tolerance against chilling stress may not attributable to the expression of known COR gene homologs in transgenic tomato. To determine which tomato genes may be induced by CBF1 protein, a subtractive hybridization experiment was performed. We isolated several cDNAs that accumulated either to a greater or to a lesser amount in the transgenic plants compared with the wild type (data not shown). The identities of these cDNA clones were revealed by BLAST searching the GenBank database; no known COR homologs were among the cDNAs we isolated, whereas, the CATALASE1 (accession no. M93719) gene transcript was the most prominent. Northern-blot analysis using the tomato CAT1 cDNA as a probe showed that the level of CAT1 RNA transcripts was about 2-fold greater in the three transgenic tomato lines than in wild-type plants in the unstressed condition (Figs. 1A and 6A). Arabidopsis CBF1 was only expressed in the three transgenic tomato lines, and transgene expression did not perturb the expression of β-TUBULIN (Fig. 1A). These results indicated that the expression of CBF1 in transgenic plants influenced the expression of CAT1 gene either directly or indirectly.

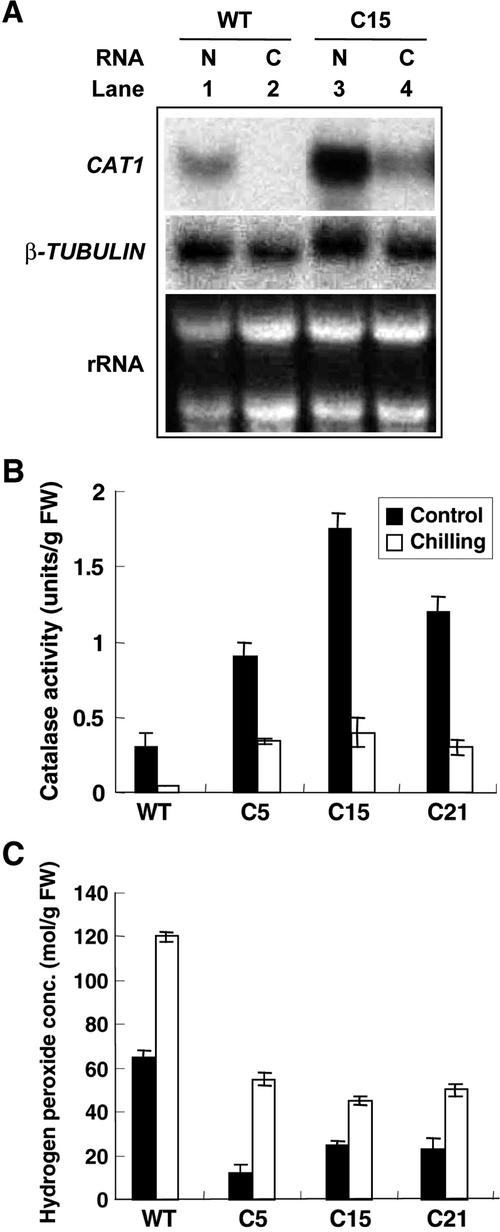

Figure 6.

Constitutive expression of CBF1 increases CAT1 and GST-like transcripts and CAT activity and reduces the H2O2 concentration in the transgenic plants. Total RNA (10 μg) was extracted from leaves of wild-type and transgenic tomato plant C15 line grown at 24°C (N) and was exposed to chilling for 3 d (C), respectively. The northern blots were hybridized with the probes for CAT1 and β-TUBULIN (A). The activities of CAT (B) and H2O2 concentration (C) in the transgenic tomato plants are shown. Tomato plants were grown at 24°C growth condition (control) and exposed to 0°C for 7 d (chilling), respectively. The hydrogen peroxide concentration was also measured in the same condition.

Expression of the CAT1 Gene and Catalase Activity Were Maintained at High Levels in Chilling-Stressed Transgenic Tomato Plants

Northern blot was performed to examine the response of tomato CAT1 toward low-temperature treatment. The amount of CAT1 transcript was significantly reduced in both the wild-type and transgenic plants, but remained high in transgenic plants under chilling stress (Fig. 6A). We also measured the level of CAT activity in crude leaf extracts, from the transgenic and wild-type plants under normal and chilling conditions (Fig. 6B). The results were consistent with those of northern-blot analysis of CAT1 transcripts. CAT activities decreased after chilling stress both in the transgenic and wild-type plants, however, the enzyme activities in the transgenic plants were still higher than that of the wild-type plants under the same condition (Fig. 6B). Because CAT activity was affected, we also determined the H2O2 content in the transgenic tomato plants. The amount of H2O2 in the transgenic plants was significantly lower than that in the wild-type plants under normal or chilling conditions (Fig. 6C). The mRNA expression patterns of CAT1 gene were similar in the three transgenic tomato plant lines under chilling stress (data not shown).

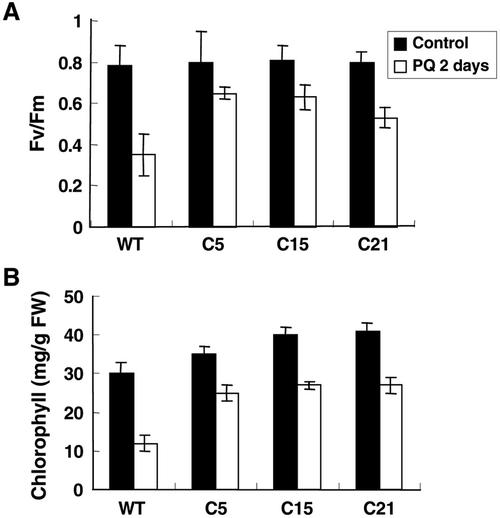

Enhanced Tolerance to Oxidative Stress in Transgenic Tomatoes

Because the catalase activity and H2O2 content in the transgenic plants were altered, we investigated the response of transgenic plants to methyl viologen, an oxidative stress-inducing agent. Methyl viologen treatment caused about 50% reduction in the Fv/Fm value in the wild-type plants, whereas the transgenic plants suffered a lesser loss (Fig. 7A). The damage caused by methyl viologen was also reflected by the degree of bleaching of the tissues. The total chlorophyll content decreased up to 60% in the wild type by methyl viologen treatment, but the loss in the transgenic plants was less than 30% (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Improved tolerance of CBF1 transgenic tomato plants under methyl viologen-induced oxidative stress condition. Five leaf discs were incubated in water or 10 μm methyl viologen for 2 d. Light-activated fluorescence (A) and loss of chlorophyll (B) in transgenic and wild-type tomato plants were measured after treatment. The results are an average of five measurements with less than 5% sd.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that the constitutive expression of CBF1 in tomato increased the degree of tolerance to chilling (Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5), which is an interesting and unique feature because tomato is generally considered a chilling-sensitive plant and does not cold-acclimate like Arabidopsis. Although CBF1 or DREB1A confers increased freezing tolerance to transgenic Arabidopsis, the transgenic tomato plants were not able to survive subzero temperature (data not shown). This is probably because of the lack of expression of known COR homologs in transgenic tomatoes, which have been shown to be associated with freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis (Jaglo-Ottosen et al., 1998; Liu et al., 1998; Kasuga et al., 1999). Indeed, we did not detect any transcripts in the transgenic plants using the Arabidopsis COR47, COR15a, and KIN1 as probes even in low stringent hybridization conditions (data not shown). So far, we cannot rule out the possibility that there are homologs of other COR genes in the tomato genome. COR proteins are quite hydrophilic and are believed to function by acting as a molecular shield for plant cells against freezing and drought stress (Thomashow, 1998). It has recently been shown that overexpression of the Arabidopsis CBF3 mimics multiple biochemical changes associated with cold acclimation (Gilmour et al., 2000). Moreover, several novel genes controlled by the DREB1A protein have been cloned (Seki et al., 2001). These results suggest that the cold acclimation phenomenon may be conferred by multiple defense systems. Using known Arabidopsis COR cDNAs as probes on CBF1 transgenic tomato did not hybridize to any transcripts in tomato; this may imply that the CBF1 transgenic tomato plants are tolerant to chilling and oxidative stresses through the induction of alternative tomato protein(s) that function as stress protectant(s).

The suppression-subtractive hybridization technique allowed us to isolate differentially expressed genes from CBF1 transgenic tomato. Our results suggest that the heterologous transcriptional activator CBF1 protein can regulate the expression of certain tomato genes. By identifying these genes, we attempt to provide a molecular basis to explain why CBF1 conferred chilling- and oxidative-stress tolerance to tomato. In our study, up-regulation of CAT1 expression in the transgenic tomato plants was observed (Figs. 1A and 6A). Moreover, the level of catalase activity was also increased in the transgenic plants (Fig. 6B). In addition, the H2O2 content was lower in the transgenic plants (Fig. 6C). Catalase is believed to scavenge the H2O2 that is produced when plants respond to environmental and physiological stress (Scandalios et al., 1997). In maize (Zea mays), CAT1 expression is induced by osmotic stress through two alternative signal transduction pathways, an ABA-signaling pathway and an ABA-independent pathway, mediated by two different DNA binding factors, CAT1 binding factor 1 and 2, respectively (Guan et al., 2000). Tomato CAT1, maize CAT3, and rice (Oryza sativa) CAT-A belong to class II catalase and are expressed mainly in vascular tissues (Dat et al., 2000). It had been reported that the CAT3 gene expression and its enzymatic activities are increased during acclimation in chilling-sensitive maize. The improvement of chilling tolerance conferred by acclimation in maize is correlated with the up-regulation of the CAT3 gene (Anderson et al., 1994; Prasad, 1997; Dat et al., 2000). Transgenic tomato plants overexpressing antisense CAT1 were more sensitive to oxidative stress and chilling injury (Kerdnaimongkol and Woodson, 1999), suggesting CAT1 plays an important role in protecting the plant from oxidative and chilling stresses. Taken together, these results suggest that the enhancement of stress tolerance in transgenic tomato expressing CBF1 may be partially, if not solely, due to the induction of the CATALASE1 gene.

CBF1 contains a conserved DNA-binding AP2 domain, which is known to be involved in floral morphogenesis (Ohme-Takagi and Shinshi, 1995; Okamuro et al., 1997; Gilmour et al., 1998; Medina et al., 1999). The AP2 domain has been shown to be present in many plant genes, such as EREBP, APETALA2, AINTEGUMENTA, and TINY (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 2000). EREBP proteins can bind to the ethylene-responsive element (GCC box), and DREB/CBF proteins bind to the common sequence of PuCCGNC (Liu et al., 1998). Based on DNA sequence analysis, we suggest that a putative CRT/DRE binding site may exist on the maize CAT3 and rice CAT-A promoter. The TGGCCGAC sequence in the rice CAT-A promoter and the GGCCCGAC sequence in the maize CAT3 promoter are very similar to the TGGCCGAC sequence in the Arabidopsis COR15a promoter, which is recognized by the CBF1 protein (Thomashow, 1999). The Arabidopsis CAT3 gene was recently found to be induced by cold, drought, and the overexpression of DREB1A, a member of CBF family (Seki et al., 2001). Although the promoter sequence of tomato CAT1 is not currently available, the up-regulation of CAT1 in transgenic tomato plants may be due to the existence of a CRT/DRE sequence in the promoter that was recognized by Arabidopsis CBF1. However, more evidence is needed to determine whether the heterologous CBF1 activates CAT1 directly or indirectly.

One interesting feature of the CBF1 transgenic plants is the dwarf phenotype (Fig. 4A). Similar growth retardation was also observed in transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing DREB1A (Kasuga et al., 1999). The transgenic tomato plants exhibited an apparent dwarfism along with a reduction in fruit set and seed number per fruit. The dwarf phenotype was due to shorter internodes of the transgenic tomatoes compared with those of the wild-type plants. However, these phenomena could be reversed by GA3 treatment (Fig. 4A), suggesting that either hyperaccumulation of CBF1 protein in the transgenics or overexpression of CBF1 may be interfering with GA biosynthesis in the transgenic plants. Preliminary results also shown that application of GA3 to the transgenic tomatoes increased the number of fruit and seed of GA3-treated transgenic plants to a level similar to that of the wild-type plants (T.-H. Hsieh, Y.-y. Charng, and M.-T. Chan, unpublished data). The chilling tolerance of transgenic tomato plants was not affected by GA3 treatment (Figs. 4 and 5), suggesting that the dwarf phenotype is not correlated with the ability to tolerate chilling stress. The benefit of using an inducible promoter to drive DREB1A has been demonstrated (Kasuga et al., 1999). By replacing the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter with inducible promoter such as RD29A in transgenic Arabidopsis, enhanced stress tolerance was achieved without a penalty on plant growth (Kasuga et al., 1999). Therefore, the observed growth retardation and the reduction of fruit and seed production in the transgenic tomatoes may be similarly preventable by replacing the constitutive 35S promoter with stress-inducible promoter.

This study has demonstrated that a heterologous CBF1 gene could significantly enhance chilling- and oxidative-stress tolerance in tomato plants. A tomato CBF homolog has been recently discovered by searching the expressed sequence tag database (Jaglo et al., 2001). However, the function of the tomato CBF is not known. It may play a role similar to the Arabidopsis CBF1 and DREB genes in regulating a suite of stress-related genes during acclimation. Although tomato is generally considered as a subtropical plant that does not cold-acclimate, cold hardening of tomato seedlings is a commonly practiced cultivating process. Because no known COR homologous genes have been reported in tomato, this may explain why tomato is not a plant tolerant of freezing. It would be of interest to know whether overexpression of the tomato CBF homolog in Arabidopsis or tomato could also yield results similar to the overexpression of Arabidopsis CBF1 in these plants. We believed that a similar approach may be applicable to other important crops to improve tolerance against stressful conditions. This may be accomplished by transferring several (e.g. 3–4) key regulatory genes, rather than a large number of stress-related genes under inducible promoters. Overall, the engineering of stress-tolerant crops by incorporating (a) master switch gene(s) like CBF1 may be an efficient approach to minimize stress damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia was grown in controlled environment chambers at 24°C, 50% relative humidity, with a 24-h photoperiod (about 120 μmol m−2 s−1). Seeds of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum [L.] Miller cv CL5915-93D4-1-0-3), kindly provided by Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center (Tainan, Taiwan), were soaked at 32°C for 1 h, surface-sterilized for 10 min with 1% (w/v) NaOCl, washed twice with sterile water for 5 min, and subsequently germinated on Murashige and Skoog medium with a 16-h photoperiod at 26°C.

DNA Construct

A CBF1 gene was isolated by reverse transcriptase-PCR from 3-week-old Arabidopsis leaves as described previously (Chan and Yu, 1998). Two primers covering the whole CBF1 coding region were chosen to amplify a 640-bp DNA fragment. The 5′ primer (5′-ACGCGTCGACATGAACTCATTTTCAGCTTTT-3′) and the 3′ primer (5′-CGAGCTCTTAGTAACTCCAAAGCGACA-3′) were located at the translation initiation site (ATG) and the stop site (TAA) of the CBF1 coding region, respectively. A pfu DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) was used to amplify the DNA fragment to minimize the chance of sequence mutation. The 640-bp PCR product was cloned into the T7Blue(R) vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) to form pT7Blue-CBF1, and the DNA sequence was determined by a PRISM 373 automatic DNA sequencing system (ABI, Sunnyvale, CA). The CBF1 cDNA was then cloned into pJD301 (Luehrsen et al., 1992) by removing its luciferase gene to form the intermediate vector. The fragment containing a cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, tobacco mosaic virus Ω leader, a CBF1 gene, and a nos poly(A) was excised by digesting with BamHI and BglII from the intermediate vector and cloned into the BamHI site of pCAMBIA 2301 (Center for the Application of Molecular Biology of International Agriculture, Black Mountain, Australia) to form pJLM1. The pCAMBIA 2301 vector contains two other selectable markers, GUS and NPTII genes driven by two separate 35S promoters. Plasmid was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 cells by electroporation.

Production of Transgenic Tomato Plants

Cotyledons of 7- to 10-d-old tomato seedlings were used for transformation. Individual cotyledons were cross-cut into two pieces and precultured upside down on KCMS medium (Fillatti et al., 1987) containing 100 μm acetosyringone for 1 d. The subsequent plant transformation procedure was performed as described (Fillatti et al., 1987).

Analysis of Transgenic Tomato Plants

To identify positive transgenic lines for Southern analysis, genomic DNA from rooted putative transformants growing on Murashige and Skoog medium with 100 mg L−1 kanamycin sulfate were extracted as described previously (Chan et al., 1993). Total RNA isolation as well as DNA and northern-blot analyses were performed as described (Chan et al., 1994). The GUS DNA isolated from the BamHI-SacI restriction fragment of plasmid pBI221 (CLONTECH Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA) and the CBF1 gene isolated from pT7Blue-CBF1 were used as probes. Tomato β-TUBULIN cDNA fragment was isolated by reverse transcriptase-PCR from 3-month-old tomato plant leaves. The 5′ primer (5′-CCCGGGCACACTTGATCCCATTCGT-3′, SmaI site underlined) and the 3′ primer (5′-CCCGGGCATTCTGTCTGGGTACTCT-3′, SmaI site underlined) were chosen to amplify the 539-bp β-TUBULIN partial cDNA fragment. The PCR fragments were cloned into pT7Blue(R) and the DNA sequences were determined by an ABI PRISM 373 automatic DNA sequencing system. CAT1 (accession no. M93719) was isolated from subtractive hybridization and excised from pT7Blue(R) vector as probes. These fragments were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using the random primer method (Feinberg and Vogelstein, 1983). The GUS histochemical staining assay was performed according to previously described methods (Chan et al., 1993). Tomato seeds produced from transgenic tomato plants were collected, and selection procedures were performed as described above.

Analysis of Transgenic Plants under Cold and Oxidative Stress Conditions

To evaluate cold tolerance, the transgenic T1 and wild-type plants were placed into cold conditions under 16/8-h light (about 120 μmol m−2s−1) for various times (1, 3, 5, and 7 d), leaves were excised from the wild-type, and the transgenic tomato plants were immersed in deionized water and subjected to ion leakage determination with a conductivity meter. The sample was then autoclaved to destroy the cells and release all ions. The value obtained after autoclaving was designated as 100% electrolyte leakage. Survival rate was defined as the number of healthy plants after incubation at 0°C for 7 d and transfer to room temperature for 5 d divided by the total number of plants treated in this manner. Pictures were also taken to record the phenotypes.

Chlorophyll fluorescence values of methyl viologen-treated leaf discs and whole leaves of chilling-treated tomato plants were measured using a pulse-activated modulation fluorimeter (Walz, Effeltrich, Germany) according to the method described by Obershall et al. (2000). The amount of H2O2 was assayed as previously described by O'Kane et al. (1996).

GA3 and Cold Treatment of Wild-Type and Transgenic Tomato Plants

Wild-type and 3-week-old transgenic T1 tomato plants were sprayed with 5 μL L−1 GA3 three times for 1 week. After GA3 treatment, whole plants were incubated at 0°C for 1, 3, 5, and 7 d, and then chlorophyll fluorescence was tested. Total chlorophyll in leaf tissue was measured according to previously described methods (Deak et al., 1999).

The T2 seeds chilling tolerance test of homozygous transgenic lines and wild-type tomato plants was performed basically according to the method of Rab and Saltveit (1996) with some modification. T2 seeds were soaked overnight at 25°C and transferred to three layers of wet paper towel between two 19- × 19.5-cm glass plates that were oriented according to the protocol. For GA3 pretreatment, the transgenic and wild-type germinated seeds were soaked in water containing 5 μL L−1 GA3 at 25°C for 2 d before cold treatment. The cold treatment was set at 2°C for 5 d in the dark, and transferred to 25°C for 3 d under 16/8-h light (about 120 μmol m−2s−1) for radical regrowth after cold treatment. The subsequent radical elongation was measured and recorded at the end of the 3-d regrowth period.

Protein Extractions, Western-Blot Analysis, and Enzyme Assays

Whole leaves of the transgenic and wild-type tomato plants were used for enzyme extractions and analyses. The protein extraction and activity assay of catalase enzyme were carried out as described by Pinhero et al. (1997). The western-blot analysis was performed as previously described (Chan et al., 1994). To prepare anti-Arabidopsis CBF1 antibodies, the CBF1 cDNA isolated from pT7Blue-CBF1 was subcloned into the pET24b vector containing His tag (Novagen) and then transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). The expressed recombinant protein was purified with a His tag affinity column (Novagen). The overexpression and purification of the CBF1 protein were performed as previously described (Kanaya et al., 1999). CBF1 polyclonal antibodies were raised in rabbits according to standard procedure.

Subtractive Hybridization

Poly(A+) RNA (0.7 μg) extracted from wild-type and transgenic tomato plants was used to perform subtractive hybridization according to the CLONTECH PCR select cDNA subtraction kit manual. Amplified PCR products were cloned into pT7Blue(R) vector (Novagen). Next, DNA sequence was determined by an ABI PRISM 373 automatic DNA sequencing system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tuan-Hua David Ho for critical review of this manuscript. We also thank Dr. Virginia Walbot for providing pJD301 plasmid DNA. We are grateful to the Institute of Molecular Biology and the Institute of Botany, Academia Sinica, the Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center, and the Department of Agronomy, National Taiwan University, for providing experimental equipment and facility.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from Academia Sinica and grants NSC-88–2317-B-001–001 and NSC-88–2317-B-001–007 from the National Science Council of the Republic of China.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.003442.

LITERATURE CITED

- Anderson MD, Prasas TK, Martin BA, Stewart CR. Differential gene expression in chilling-acclimated maize seedlings and evidence for the involvement of abscisic acid in chilling tolerance. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:331–339. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj S, Targolli J, Liu LF, Ho THD, Wu R. Transgenic approaches to increase dehydration-stress tolerance in plants. Mol Breed. 1999;5:493–503. [Google Scholar]

- Baker SS, Wilhelm KS, Thomashow MF. The 5′-region of Arabidopsis thaliana COR15a has cis-acting elements that confer cold-, drought- and ABA-regulated gene expression. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;24:701–713. doi: 10.1007/BF00029852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MT, Chang HH, Ho SL, Tong WF, Yu SM. Agrobacterium-mediated production of transgenic rice plants expressing a chimeric α-amylase promoter/β-glucuronidase gene. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:491–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00015978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MT, Chao YC, Yu SM. Novel gene expression system for plant cells based on induction of α-amylase promoter by carbohydrate starvation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17635–17641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MT, Yu SM. The 3′ untranslated region of a rice α-amylase gene mediated sugar-dependent abundance of mRNA. Plant J. 1998;15:685–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dat J, Vandenabeele S, Vranová E, Van Montagu M, Inzé D, Breusegem FV. Dual action of the active oxygen species during plant stress responses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:779–795. doi: 10.1007/s000180050041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deak M, Horvath GV, Davletova S, Torok K, Sass L, Vass I, Barna B, Kiraly Z, Dudits D. Plants ectopically expressing the iron-binding protein, ferritin, are tolerant to oxidative damage and pathogens. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:192–196. doi: 10.1038/6198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillatti JJ, Kiser J, Rose R, Comai L. Efficient transfer of a glyphosate tolerance gene into tomato using a binary Agrobacterium tumefaciens vector. Biotechnology. 1987;5:726–730. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour SJ, Sebolt AM, Salazar MP, Everard JD, Thomashow MF. Overexpression of the Arabidopsis CBF3 transcriptional activator mimics multiple biochemical changes associated with cold acclimation. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1854–1865. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour SJ, Zarka DG, Stockinger EJ, Salazar MP, Houghton JM, Thomashow MF. Cold regulation of the Arabidopsis CBF family of AP2 transcriptional activators as an early step in cold-induced COR gene expression. Plant J. 1998;16:433–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy JA, Lunar R, Torres-Schumann S, Moreno J, Rodrigo RM, Pintor-Toro JA. Expression, tissue distribution and subcellular localization of dehydrin TAS14 in salt-stressed tomato plants. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;26:1921–1934. doi: 10.1007/BF00019503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy JA, Pardo JM, Pintor-Toro JA. A tomato cDNA inducible by salt stress and abscisic acid: nucleotide sequence and expression pattern. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15:695–705. doi: 10.1007/BF00016120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan ML, Zhao J, Scandalios JG. Cis-elements and trans-factors that regulate expression of the maize Cat1 antioxidant gene in response to ABA and osmotic stress: H2O2 is the likely intermediary signaling molecule for the response. Plant J. 2000;22:87–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg N, Bulow L. Improving stress tolerance in plants by gene transfer. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath DP, McLarney BK, Thomashow MF. Regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana L. (Heynh) COR78 in response to cold. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:1047–1053. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.4.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglo KR, Kleff S, Amundsen KL, Zhang X, Haake V, Zang JZ, Deits T, Thomashow MF. Components of the Arabidopsis C-repeat/dehydration-responsive element binding factor cold-response pathway are conserved in Brassica napus and other plant species. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:910–917. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaglo-Ottosen KR, Gilmour SJ, Zarka DG, Schabenberger O, Thomashow MF. Arabidopsis CBF1 overexpression induces COR genes and enhances freezing tolerance. Science. 1998;280:104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya E, Nakajima N, Morikawa K, Okada K, Shimura Y. Characterization of the transcriptional activator CBF1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16068–16076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasuga M, Liu Q, Miura S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Improving plant drought, salt, and freezing tolerance by gene transfer of a single stress-inducible transcription factor. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:287–291. doi: 10.1038/7036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerdnaimongkol K, Woodson W. Inhibition of catalase by antisense RNA increases susceptibility to oxidative stress and chilling injury in transgenic tomato plants. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1999;124:330–336. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Kasuga M, Sakuma Y, Abe H, Miura S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transcription pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1391–1406. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luehrsen KR, de Wet J, Walbot V. Transient expression analysis in plants using firefly luciferase reporter gene. Methods Enzymol. 1992;216:397–441. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)16037-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina J, Bargues M, Terol J, Pérez-Alonso M, Salinas J. The Arabidopsis CBF gene family is composed of three genes encoding AP2 domain-containing proteins whose expression is regulated by cold but not abscisic acid or dehydration. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:463–469. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.2.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin K, Vakala T, Palva ET. Differential expression of two related, low-temperature-induced genes in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;21:641–653. doi: 10.1007/BF00014547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obershall A, Deak M, Torok K, Sass L, Vass I, Kovacs I, Feher A, Dudits D, Horvath GV. A novel aldose/aldehyde reductase protects transgenic plants against lipid peroxidation under chemical and drought stresses. Plant J. 2000;24:437–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohme-Takagi M, Shinshi H. Ethylene-inducible DNA binding protein that interacts with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell. 1995;7:173–182. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamuro JK, caster B, Villarroel R, Van Montagu M, Jufuku KD. The AP2 domain of APETALA2 defines a large new family of DNA binding proteins in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7076–7081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kane D, Gill V, Boyd P, Burdon RH. Chilling, oxidative stress and antioxidant responses in Arabidopsis thaliana callus. Planta. 1996;198:366–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00620053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet F, Vazquez-Tello A, Sarhan F. The wheat wcs120 promoter is cold-inducible in both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous species. FEBS Lett. 1998;423:324–328. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra MM, del Pozo O, Luna R, Godoy JA, Pintor-Toro JA. Structure of the dehydrin tas14 gene of tomato and its developmental and environmental regulation in transgenic tobacco. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:453–460. doi: 10.1007/BF00019097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhero RG, Rao MV, Paliyath G, Murr DP, Fletcher RA. Changes in activities of antioxidant enzymes and their relationship to genetic and paclobutrazol-induced chilling tolerance of maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:695–704. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.2.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad TK. Role of catalase inducing chilling tolerance in pre-emergent maize seedlings. Plant J. 1997;114:1369–1376. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.4.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rab A, Saltveit ME. Sensitivity of seedling radicles to chilling and heat-shock-induced chilling tolerance. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1996;121:711–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JJ, Reid JB, Gaskin P, Macmillan J. Internode length in Pisum. estimation of GA1 level in genotypes Le, le and led. Physiol Plant. 1989;76:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Saltveit ME, Mangrich M. Induction of chilling tolerance by brief abiotic shock. In: Li PH, Chen THH, editors. Plant Cold Hardiness. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Saltveit ME, Morris LL. Overview on chilling injury of horticultural crops. In: Wang CY, editor. Chilling Injury of Horticultural Crops. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sarhan F, Ouellet F, Vazquez-Tollo A. The wheat wcs120 gene family: a useful model to understand the molecular genetics of freezing tolerance in cereals. Physiol Plant. 1997;101:439–445. [Google Scholar]

- Scandalios JG, Guan LMM, Polidoros A. Catalases in plants: gene structure, properties, regulation, and expression. In: Scandalios JG, editor. Oxidative Stress and the Molecular Biology of Antioxidant Defenses. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 343–406. [Google Scholar]

- Seki M, Narusaka M, Abe H, Kasuga M, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Carninci P, Hayashizaki Y, Shinozaki K. Monitoring the expression pattern of 1300 Arabidopsis genes under drought and cold stresses by using a full-length cDNA microarray. Plant Cell. 2001;13:61–72. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Molecular responses to dehydration and cold: differences and cross-talk between two stress signal pathways. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2000;3:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger EJ, Gilmour SJ, Thomashow MF. Arabidopsis thaliana CBF1 encodes an AP2 domain-containing transcriptional activator that binds to the C-repeat/DRE, a cis-acting DNA regulatory element that stimulates transcription in response to cold and water deficit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1035–1040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow MF. Role of cold-responsive genes in plant freezing tolerance. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1–7. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomashow MF. Plant cold acclimation: freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanisms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:571–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Datla R, Georges F, Loewen M, Cuter AJ. Promoters from kin1 and COR6.6, two homologous Arabidopsis thaliana genes: transcriptional regulation and gene expression induced by cold, ABA, osmoticum and dehydration. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;28:605–617. doi: 10.1007/BF00021187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HX, Blumwald E. Transgenic salt-tolerant tomato plants accumulate salt in foliage but not in fruit. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:765–768. doi: 10.1038/90824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Klueva NY, Wang Z, Wu R, Ho THD, Nguyen HT. Genetic engineering for abiotic stress resistance in crop plants. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2000;36:108–114. [Google Scholar]