Abstract

The mdx mouse, a model of the human disease Duchenne muscular dystrophy, has skeletal muscle fibres which display incompletely understood impaired contractile function. We explored the possibility that action potential-evoked Ca2+ release is altered in mdx fibres. Action potential-evoked Ca2+-dependent fluorescence transients were recorded, using both low and high affinity Ca2+ indicators, from enzymatically isolated fibres obtained from extensor digitorum longus (EDL) and flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) muscles of normal and mdx mice. Fibres were immobilized using either intracellular EGTA or N-benzyl-p-toluene sulphonamide, an inhibitor of the myosin II ATPase. We found that the amplitude of the action potential-evoked Ca2+ transients was significantly decreased in mdx mice with no measured difference in that of the surface action potential. In addition, Ca2+ transients recorded from mdx fibres in the absence of EGTA also displayed a marked prolongation of the slow decay phase. Model simulations of the action potential-evoked transients in the presence of high EGTA concentrations suggest that the reduction in the evoked sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release flux is responsible for the decrease in the peak of the Ca2+ transient in mdx fibres. Since the myoplasmic Ca2+ concentration is a critical regulator of muscle contraction, these results may help to explain the weakness observed in skeletal muscle fibres from mdx mice and, possibly, Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients.

The absence of dystrophin causes Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), the most common debilitating genetic disorder affecting boys (for a review, see Emery, 2002). It has been shown that DMD is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene, located on the X-chromosome, which results in the improper expression of the protein dystrophin (Hoffman et al. 1987a).

Much of our knowledge of the properties of dystrophin, and the pathological consequences of its absence, comes from experimental evidence obtained studying the mdx mouse, an animal model of DMD that also lacks the expression of dystrophin protein. Importantly, although the pathophysiology of the mdx mouse is not identical to that of the DMD patient (Gillis, 1999), it has been reported that muscle fibres from both DMD patients and mdx mice exhibit significantly reduced active force development (Wood et al. 1978; Coirault et al. 1999). Using the mdx mouse model, it has been shown that the absence of dystrophin leads to the absence of the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex (DAG) (for review see Emery, 2002). In an attempt to explain the overall weakness of mdx muscle, it has been proposed that the DAG complex serves as a membrane anchor and that without it, the overall membrane integrity is compromised and the Ca2+ homeostasis of the dystrophic muscle is disrupted, leading to necrosis of the muscle (Turner et al. 1988). Although these results are controversial (for a review see Gillis, 1999), neither this mechanism nor any other proposed to date seems to account for the impaired force production of single fibres (Watchko et al. 2002; for a review see Emery, 1993).

Under physiological conditions, impairment in sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release in response to an action potential (AP) could cause skeletal muscle fibre weakness since Ca2+ is the trigger for contraction and the dependence of tension development on myoplasmic free Ca2+ concentration is very steep (Godt, 1974; Fink et al. 1990). Previous authors have investigated this possibility by recording AP-evoked Ca2+ transients. However, these authors reported only minimal differences in the kinetic properties and no significant differences in the amplitude of transients recorded from normal and mdx muscles (Turner et al. 1988; Head, 1993; Tutdibi et al. 1999).

In this paper, we have revisited the issue of evoked Ca2+ signalling in normal and mdx muscle fibres. We used low and high affinity Ca2+ indicators, in the presence of intracellular concentrations of either EGTA or N-benzyl-p-toluene sulphonamide (BTS) (Cheung et al. 2002; Shaw et al. 2003) to block contraction, in order to record AP-evoked Ca2+ transients without movement artifacts. Moreover, by measuring AP-evoked Ca2+ transients using a low affinity indicator in the presence of an EGTA concentration ([EGTA]) of 5 mm, we were able to infer the properties of SR Ca2+ release (Song et al. 1998; Novo et al. 2003) in normal and mdx fibres. Our results demonstrate that the peak free [Ca2+] changes recorded in response to AP stimulation are significantly smaller in mdx muscle fibres compared to normal counterparts. We propose that an alteration in the SR Ca2+ release flux in dystrophic muscle fibres may be responsible for this decrease. A preliminary version of this work has been presented to the Biophysical Society (Woods et al. 2003).

Methods

Isolation of fibres

All experiments were carried out according to the guidelines laid down by the UCLA Animal Care Committee. Single muscle fibres were enzymatically isolated from flexor digitorum brevis (FDB) and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles dissected from normal (C57BL/10SnJ) and mdx (C57BL/10ScSn-mdx/J) (Jackson Laboratories, ME, USA) mice. Both of these muscles have been reported to be composed mostly of fast-twitch (type II) fibres (Parry & Parslow, 1981; Raymackers et al. 2000). All experiments were done in 8- to 18-week-old normal and post-necrotic mdx mice (McArdle et al. 1995). Mice were deeply anaesthetized with halothane (loss of righting reflex) and killed by cervical dislocation. Muscles were removed, stored in cold (5°C) Tyrode solution (see below) and utilized within 30 min.

The digestion and dissociation protocol is a modification of those described in the literature (Head et al. 1990; Szentesi et al. 1997). Each muscle was placed in a Sylgard-bottomed Petri dish with its tendons held in place by pins and bathed in 0 Mg2+, 0 Ca2+ Tyrode solution supplemented with 262 units ml−1 of collagenase Type IV (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and 0.5 mg ml−1 of bovine serum albumin. The muscles were incubated for 45 min at 37°C under mild agitation. Collagenase activity was stopped by washing the muscle with 0 Mg2+, Ca2+ Tyrode solution at 37°C. The muscle mass was gently sucked in and out of a fire-polished Pasteur pipette until muscle fibres were isolated. For FDB fibres, the average diameter and length were ∼30 μm and ∼300 μm, respectively. For EDL fibres, the average diameter and length were ∼60 μm and ∼6 mm, respectively. We have found that immediately following this dissociation procedure, only very few of the large number of fibres isolated actively twitched in response to external electrical stimulation when bathed in external solutions containing 2.0 mm[Ca2+]. However, after incubation for 30 min in L-15 media (Sigma) supplemented with 0.1 mg ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma) in an O2 saturated environment at 25°C, approximately 25% of the fibres responded to external stimulation with vigorous twitches. Only this population of fibres was used. All of these observations and procedures applied identically to both normal and dystrophic muscle fibres.

Solutions

The internal solution contained (mm): 140 potassium aspartate; 20 K-Mops; 2.5 or 5 MgSO4, 5 Na2-PCr, 5 K-ATP, 5 dextrose, 2.5 glutathione, and 0.1 mg ml−1 creatine phospho-kinase. The [EGTA] of the internal was adjusted to 5 or 10 mm as specified in text. In the presence of 5 mm EGTA, the free [Mg2+] of the internal solution was calculated, using the Maxchelator program (Bers et al. 1994), to be 77 μm and 0.53 mm, for 2.5 and 5 mm total Mg2+, respectively. For experiments in the absence of EGTA, only 5 mm total Mg2+ was used, and the free [Mg2+] under these conditions was 0.6 mm. The composition of the external Tyrode solution was (mm): 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Na-Mops, 10 dextrose. The 0 Mg2+, 0 Ca2+ Tyrode solution was as above without added Ca2+ and Mg2+. In some experiments, N-benzyl-p-toluene sulphonamide (BTS), an inhibitor of the myosin II ATPase, was added to the external solution at a concentration of 50 μm as we found that this was the minimum concentration necessary to completely arrest shortening of the fibre in response to AP stimulation. All solutions were adjusted to an osmolarity of 300 mosmol kg−1 of water and a pH of 7.4. Experiments were performed at 22°C.

Electrophysiological techniques

The electrophysiological method used for enzymatically dissociated EDL fibres was similar to the triple Vaseline gap technique previously described for mechanically dissected frog muscle fibres (Hille & Campbell, 1976; Palade & Vergara, 1982; Kim & Vergara, 1998). The main change was the use of a silicone compound (Chemplex 825, NFO Technologies, KS, USA) to construct the seals, instead of petroleum jelly compounds, and the inclusion of 1% fetal calf serum (FCS, Irvine Scientific) in the external solution to further improve the tolerance of the fibres to Chemplex 825 (Szentesi et al. 1997). The fibres were straightened across the gaps, maintained at slack sarcomere length (∼2 μm) and loaded with internal solution (see below) through the cut ends. The holding potential of the central pool was set at −95 mV.

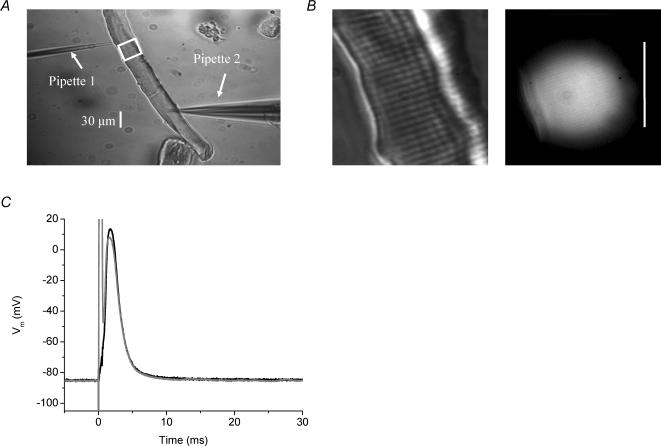

FDB muscle fibres were transferred to an optical chamber (DiGregorio et al. 1999) containing Tyrode solution and impaled with two micropipettes. These micropipettes were placed ∼150 μm apart in un-stretched fibres with a sarcomere length of ∼2 μm, as shown in the phase contrast image in Fig. 1A. The first one was a high resistance micropipette (pipette 1, Fig. 1A), which had ∼40 MΩ resistance when filled with 3 m KCl, and the second one was a low resistance micropipette (pipette 2, Fig. 1A), which had a resistance of ∼30 MΩ when filled with internal solution. Pipette 1 was used to record the transmembrane potential (Vm). No current was passed through this electrode. Pipette 2 was used to load the fibre with internal solution, to maintain its resting potential, and to stimulate it. Both micropipettes were connected to a TEV-200A amplifier (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN, USA). To rule out differences in the passive electrical properties between normal and mdx fibres used in our experiments, we compared the current necessary to set the Vm to −90 mV and found that, from a large population of twitching fibres, including those reported in Results, in the absence of BTS, 11.7 ± 1 and 12.3 ± 1 nA of current was necessary in normal and mdx fibres, respectively (n = 49 fibres from 12 normal mice; n = 43 fibres from 14 mdx mice) and in the presence of BTS, 33 ± 7 and 35 ± 5 nA of current was necessary for normal and mdx fibres, respectively (n = 12 fibres from 5 normal mice; n = 28 fibres from 6 mdx mice). In comparison to the steady-state holding current, APs were elicited using suprathreshold current pulses of 0.5 ms duration and 0.2−0.5 μA amplitude (upper and lower limits for experiments in both the presence and absence of BTS), with no observed difference in the magnitude of the pulses necessary for AP stimulation between normal and mdx fibres. For FDB fibre experiments described in this report, the resting Vm was adjusted to the values indicated in the figure legends with the aid of constant hyperpolarizing current injection. The area enclosed by the white square in Fig. 1A is shown at higher magnification in Fig. 1B in order to illustrate the striation pattern of the fibre (left panel) and the disc-shaped illumination area where the fluorescence signals were recorded from in a typical fibre. Figure 1C shows the APs recorded at both pipettes superimposed. As expected, the recordings from pipette 2 show a saturating stimulus artifact that prevents the recording of the initial part of the rising phase of the AP. As the artifact could not be eliminated, we included a second microelectrode (pipette 1) to faithfully acquire the AP. As can be seen Fig. 1C, the record of the AP from pipette 1 does not show the artifact. All AP records from FDB fibres in the paper were recorded by pipette 1.

Fig. 1. Two-pipette stimulating and recording method.

A, 10 × phase contrast image of a normal FDB fibre impaled with two electrodes as described in text. B, 40 × magnification images of same fibre showing phase image and corresponding OGB-5N fluorescence image from the region circumscribed by the white square in A. Calibration bar is 30μm. C, surface AP from a normal mouse FDB from pipette 1 (black) and pipette 2 (grey). Internal solution contained 5mm EGTA and the external solution was normal Tyrode solution.

The FDB fibres were loaded passively with the internal solution by a mechanism comparable to that described for patch clamp experiments (Pusch & Neher, 1988; Mathias et al. 1990; Wang et al. 1999). Accordingly, the loading rates of relevant pipette constituents were calculated using the measured value for the pipette resistance, published values for the diffusion coefficients and resistivity, and an estimated cell volume for a FDB muscle fibre of typical dimensions and geometry, assuming that 70% of the fibre volume is free for diffusion of exogenous constituents without binding (Melzer et al. 1987). The resistivity for the internal solution was assumed to be 240 Ω cm (Pusch & Neher, 1988), and the values for the diffusion coefficients were 1.8 × 10−5, 9 × 10−6, and 5.6 × 10−6 cm2 s−1, for K+ ions, fluorescein (a molecule of comparable molecular weight to EGTA) and Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-5N (OGB-5N), respectively (Pusch & Neher, 1988; Woods & Vergara, 2002). Assuming that the diffusion coefficient of EGTA equals that of fluorescein, our calculations show that 30 min after impalement, the intracellular concentrations of K+, EGTA and OGB-5N were 94, 78 and 60%, respectively, of their pipette values. At 60 min after impalement the corresponding percentages were: 99.8, 95 and 84%, respectively. A final caveat to these results is that, for at least the Ca2+ indicator, binding to intracellular constituents most likely occurs as reported previously (Maylie et al. 1987; DiFranco et al. 2002). In fact, the resting fluorescence continued to rise throughout the experiment (∼1 h) without reaching a steady-state value, as would be expected for a process of diffusion with binding (Maylie et al. 1987).

In agreement with the theoretical calculations for loading, by 30 min following impalement, the properties of ΔF/F transients (see below) were stable within 8% of each other (standard deviation/mean). In addition, in the presence of at least 5 mm EGTA, fibre movement was arrested by 30 min as judged both by the absence of movement artifacts in the electrical and optical records, as well as by visual inspection of the fibre imaged with 100× magnification on the screen of a monitor. Thus, all optical measurements were initiated 30 min after fibre impalement. After recordings were started, the fluorescence transients were stable, typically for 30 more minutes and in some cases for as long as 90 more minutes. In addition, ΔF/F transients measured near pipette 2 and at the ends of the fibre had similar properties. Thus, after the equilibration period, the concentrations of solutes in the fibre were assumed to approximate that of the internal solution in pipette 2, with the caveat that binding to internal constituents of the fibre may prevent the attainment of a true steady state.

Ca2+ measurements and data analysis

[Ca2+] was measured using the cell-impermeant forms of the Ca2+ indicators OGB-5N (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) or Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 (OGB-1, Molecular Probes). The concentration of OGB-5N in the internal solution was 500 μm and that of OGB-1 was 50 μm. The equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd values) and the Fmax/Fmin ratio (R) of OGB-5N and OGB-1 were determined in vitro using protocols similar to those described elsewhere (Escobar et al. 1997; Nagerl et al. 2000). Briefly, the free [Ca2+] of a set of standard solutions (pCa 9 to 3, in increments of 0.5 pCa units) was measured and adjusted with custom-made Ca2+-sensitive electrodes. These were made of a small plastic (PVC) tube (10–20 mm long, 0.7 mm in diameter) of which 0.5–1 mm of one side was filled with a 1: 1 mixture of 10% (w/w) Ca2+-selective ionophore II (Fluka/Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) plus 2% (w/w) sodium tetraphenylborate dissolved in 2-nitrophenyloctyl ether and 8–10% (w/w) polyvinylchloride dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF). A thin Ca2+-selective membrane formed after evaporation of the THF, and the electrodes were stored at room temperature for at least 2 days before use. Electrodes were used only if they exhibited linear (Nernstian) behaviour in the pCa range of 3–8 with a slope of at least 27 mV pCa−1 and a measurable responsivity to pCa 9. Both Ca2+ dyes were dissolved in every standard solution to a concentration of 20 μm and the fluorescence of a sample of each solution (10 μl) was measured using the optical set-up described below. The fluorescence values were used to generate fluorescence versus pCa calibration curves which were fitted with eqn (2) from Escobar and collaborators (Escobar et al. 1997). For the particular batch of OGB-5N (lot No. 34B2-1) used in this report, Kd and R were 48 ± 7 μm and 11 ± 0.26, respectively. For OGB-1 these values were 155 ± 29 nm and 11 ± 1.1, respectively. The free [Ca2+] of the internal solutions were determined by interpolation from the OGB-1 calibration curve. Fluorescence measurements of the internal solution samples containing 20 μm OGB- (with or without EGTA) were made and pCa values were interpolated from the dye calibration curves. In so doing, the free [Ca2+] of the internal solution was estimated to be 64 ± 5 nm in the absence of EGTA and 2 ± 1 nm in the presence of 5–10 mm EGTA. Using the flash photolysis method (Escobar et al. 1997; Nagerl et al. 2000), we calculated the in vitro association and dissociation rate constants for OGB-5N to be: kon= 1.57 μm−1 s−1 and koff= 7520 s−1, respectively. For EGTA, we adopted previously reported values of Kd= 71 nm, kon= 10.5 μm−1 s−1 and koff= 0.75 s−1 (Nagerl et al. 2000).

Spatially averaged AP-evoked fluorescence transients were recorded with OGB-5N or OGB-1 using either an inverted microscope (FDB experiments) or an upright microscope (EDL experiments). Both optical set-ups have been described previously (Kim & Vergara, 1998; DiGregorio et al. 1999). The fluorescence transients were normalized to ΔF/F units and characterized according to the following parameters as previously described (Vergara & DiFranco, 1992; DiFranco et al. 2002): (ΔF/F)peak; duration, expressed as the full-duration–half-maximum (FDHM); and delay to peak (tp), measured from the initiation of the rising phase of the transient to (ΔF/F)peak. The decay phase of the OGB-5N transients was fitted, using a least-squares fitting routine (Origin 6.1, Microcal, Northhampton, MA, USA), to the following biexponential function:

| (1) |

where t is the time (in ms) after the peak of the transient, and Afast and Aslow are fitted amplitudes of the fast and slow components, the sum of which cannot exceed the (ΔF/F)peak.

Assuming that OGB-5N was at equilibrium with the free peak [Ca2+] and that the resting fluorescence of the indicator in the fibres was equal to Fmin, the free peak [Ca2+] underlying the (ΔF/F)peak values of the OGB-5N transients could be estimated according to the following equation:

| (2) |

The validity of these assumptions for fluorescence transients recorded with low affinity indicators, such as OGB-5N, has been demonstrated previously (Escobar et al. 1995, 1997). The values for R for OGB-5N were measured in vivo as described elsewhere (Vergara & DiFranco, 1992; Vergara et al. 2001) and found to be 11 ± 3 (n = 3), comparable to the in vitro condition (see above).

To determine the AP-evoked SR Ca2+ release flux, OGB-5N ΔF/F transients recorded in the presence of high internal [EGTA] were analysed using the closed form equilibrium approximation of Song and collaborators (eqn (5) in Song et al. 1998) and a single compartment kinetic model including EGTA, the Ca2+ indicator, and Ca2+ as the reactants with rate constants determined in vitro. The model generated ΔF/F transients according to the following equation:

| (3) |

where [BCa(t)] is the time-dependent concentration of the Ca-bound indicator and [Btot] is the total concentration of indicator in the cell. The initial concentration of the Ca-bound indicator ([BCa(0)]) was calculated according the following formula:

| (4) |

where [Ca2+(0)] is the resting (initial) [Ca2+] taken as the value in the internal solution in the presence of 5 mm[EGTA]. The kinetics of the Ca2+ release flux (J(t)) was described by the equation:

| (5) |

where t is time (in ms) beginning at the rising phase of the transient. Jmax (in μm ms−1), A1, A2 and A3 (dimensionless), and τon, τoff1, τoff2 and τoff3 (in ms) were adjusted until the time course of the simulated ΔF/F transient closely approximated the measured transient.

Statistics

For statistical analysis of the data, the parameters described above were determined from a minimum of 10 individual AP-evoked transients per fibre, separated in time such that the (ΔF/F)peak remained within the stability definition above, and averaged to determine a set of mean values for the fibre. The data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). An unpaired two-population Student's t test, assuming unequal variance, was used to compare the mean fibre values between mdx and normal mice. P values are given in the text.

Results

OGB-5N fluorescence transients recorded in FDB muscle fibres with 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution

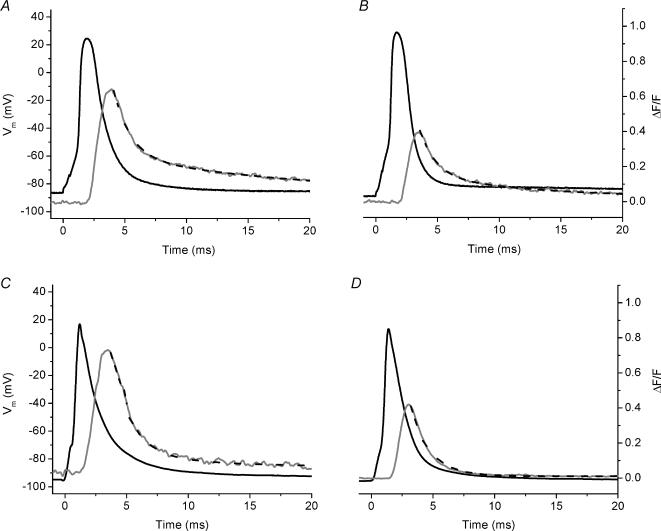

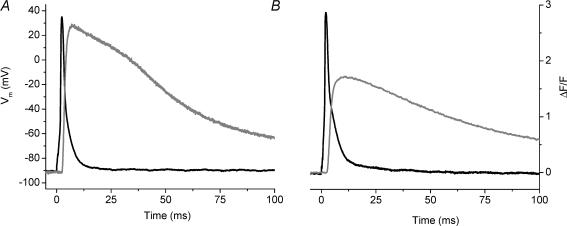

Our goal was to examine the AP-evoked SR Ca2+ release of normal and dystrophic fibres. We chose to record Ca2+ transients in fibres loaded with EGTA since this Ca2+ buffer at pipette concentrations of ≥5 mm is able to effectively arrest fibre movement in response to AP stimulation. As has been suggested previously, the reason for this is that high intracellular [EGTA] constrains the evoked changes in free myoplasmic [Ca2+] to regions near the Ca2+ release sites (Pape et al. 1995; DiGregorio et al. 1999; Novo et al. 2003). Empirically, our results reflect this situation because fibre movement was blocked. An additional advantage of using sufficiently high [EGTA] is that global fluorescence transients recorded using the low affinity Ca2+ indicator OGB-5N can closely track the time course of the SR Ca2+ release flux (Song et al. 1998; DiFranco et al. 2002; Novo et al. 2003). Figure 2A shows superimposed traces of the surface AP and the evoked OGB-5N transient recorded from a normal FDB fibre with 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution. The OGB-5N transient had a rising phase that reached a (ΔF/F)peak of 0.66 in a tp of 1.4 ms and a FDHM of 3.2 ms. Moreover, the decay of the transient displayed an initial rapid phase, followed by a slower decay phase towards baseline. We fitted this decay portion of the ΔF/F transient with a biexponential function (see Methods) yielding a τfast of 1.4 ms and a τslow of 23 ms. The magnitude of the contribution of the fast component was larger than that of the slow component (Aslow/Afast= 0.6). Figure 2B shows corresponding signals recorded from a FDB fibre isolated from an mdx mouse. While the AP amplitude is similar to that of a normal mouse (Fig. 2A), the (ΔF/F)peak of the OGB-5N fluorescence transient was 0.39, which is 41% reduced compared to that of the normal transient (Fig. 2A). The kinetic features of the ΔF/F transient were quite similar between the two, with the normal fibres displaying a slightly longer τslow (1.4 ± 0.2 times), and similar tp and FDHM (see figure legend for values). Rows 1 and 2 of Table 1 summarize these results from multiple experiments. There was a highly significant 43 ± 2% decrease in the (ΔF/F)peak of the AP-evoked OGB-5N transient in mdxversus normal FDB fibres. While the τfast of mdx FDB fibres was significantly prolonged, neither the AP amplitude nor any of the other kinetic properties of the OGB-5N transients were significantly different between normal and mdx FDB fibres under these conditions. Moreover, we have performed these experiments with the total [Mg2+] set at 2.5 or 5 mm in the internal solution and have observed no difference in the results. Therefore, data from fibres in both conditions have been merged in the Table 1. All FDB experiments presented throughout the rest of the Results section were performed with 5 mm Mg2+ in internal solution.

Fig. 2. AP-evoked OGB-5N global fluorescent transients from normal and mdx single fibres recorded in the presence of 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution.

A, AP (black) and evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from an 8-week-old normal mouse FDB fibre. ΔF/Fpeak= 0.66, tp= 1.4 ms, FDHM = 3.2 ms, τfast= 1.4 ms, τslow= 23 ms, A1= 0.44 ms, A2= 0.25. Fibre diameter = 30 μm. Resting Vm=−86 mV. B, AP (black) and evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from an 8-week-old mdx mouse FDB fibre. ΔF/Fpeak= 0.39, tp= 1.4 ms, FDHM = 2.8 ms, τfast= 1.4 ms, τslow= 10.4 ms, A1= 0.27, A2= 0.12. Fibre diameter = 29 μm. Resting Vm=−90 mV. C, superimposed AP (black) and evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from a 16-week-old normal mouse EDL fibre. Fibre diameter = 54 μm. Holding potential of the central pool was set to −95 mV. D, AP (black) and OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from an 18-week-old mdx EDL. Fibre diameter, 65 μm. Holding potential of the central pool was set to −95 mV. The black dashed lines in all panels are the corresponding two-exponential (Figure 2A and B) and single exponential (Figs 2C, D) fits to the fluorescence data. For all panels, t = 0 corresponds to the onset of stimulation.

Table 1. AP amplitude, OGB-5N transient parameters, and peak [Ca2+] for normal and mdx muscle fibres in the presence of 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution.

| AP amplitude (mV) | (ΔF/F)peak | Peak [Ca2+] (μm) | tp (ms) | FDHM (ms) | τ1 (ms) | τ2 (ms) | Aslow/Afast | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal FDB | 111 ± 4.4 | 0.72 ± 0.05* | 3.7 ± 0.3* | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2** | 21 ± 3 | 0.4 ± 0.05 |

| mdx FDB | 108 ± 3 | 0.41 ± 0.03* | 2.1 ± 0.2* | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.2** | 16 ± 1 | 0.3 ± 0.03 |

| Normal EDL | 92 ± 29 | 0.80 ± 0.04** | 4.1 ± 0.4** | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | — | — |

| mdx EDL | 100 ± 24 | 0.40 ± 0.02** | 1.9 ± 0.4** | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | — | — |

For FDB fibres: fluorescence transient parameters and peak [Ca2+] were obtained from n= 9 fibres from 4 normal mice, and n= 14 fibres from 4 mdx mice (n= 6 fibres from 2 normal mice for and n= 4 fibres from 2 mdx mice in the absence of BTS, with 2.5 mm total [Mg2+] and the rest obtained in the presence of 50 μm BTS with 5 mm total [Mg2+]). AP amplitudes were obtained from n= 8 fibres from 4 normal mice and n= 14 fibres from 4 mdx mice. For EDL fibres: for both normal and mdx mice, all the parameters were obtained from n= 3 fibres from 3 mice each.

Statistical significance between normal and mdx fibres within muscle type (P < 0.0001);

statistical significance between mdx and normal EDL fibres (P < 0.05).

OGB-5N fluorescence transients recorded in EDL fibres with 5 mm EGTA in the cut ends

Since it was possible that the degree of impairment of AP-evoked Ca2+ release in mdx fibres was dependent on the muscle from which the fibres were derived, we measured evoked OGB-5N transients in the presence of 5 mm EGTA in EDL muscle fibres. The length of these fibres is too long to allow an approximate equilibration of the pipette contents within the fibre in a reasonable time using the microelectrode methodology. Consequently, we used the triple Vaseline gap technique for EDL fibres, instead. Figure 2C and D shows superimposed records of the AP and the evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient recorded for either a normal or an mdx EDL fibre, respectively, which show that the (ΔF/F)peak is decreased for the mdx transient compared to the normal transient, while the kinetic features of the transients are not different (see figure legend for values). In parallel to the findings for the FDB fibres, the results from multiple experiments demonstrate that the (ΔF/F)peak of the OGB-5N transient is significantly decreased by 51 ± 3% in mdx compared to normal EDL fibres. Comparison of the (ΔF/F)peak between normal FDB and EDL fibres (first and third row, Table 1) as well as between mdx FDB and EDL fibres (second and fourth row, Table 1), demonstrated no significant difference (P > 0.5) within each population. Consequently, by pooling the results from FDB and EDL fibres shown in Table 1, we calculate an average 45 ± 6% decrease in the (ΔF/F)peak of the OGB-5N transients in mdx compared with normal muscle fibres (P < 0.0001, n = 14 fibres from 8 normal mice, n = 18 fibres from 8 mdx mice). Analogous to the results in FDB fibres, we observed no differences in the kinetic parameters of ΔF/F transients between normal and mdx EDL fibres. However, in contrast to the FDB fibre transients, the decay phase of EDL fibres was best fitted by a single exponential function (Table 1, rows 3 and 4). It can also be observed that the OGB-5N transients from EDL fibres from both normal and mdx fibres have briefer FDHM values than the corresponding transients obtained from FDB fibres. These differences may result from differences between EDL and FDB fibres or between the techniques used to load of the fibre with EGTA: the gap isolation technique versus the two pipette method. Given the similarity in the (ΔF/F)peaks between EDL and FDB fibres within strains of fibres, it seems likely, however, that this reflects an intrinsic difference between the two muscles.

OGB-5N fluorescence transients recorded in FDB fibres in the presence of BTS, and in the absence of EGTA

It is possible that the high [EGTA] in the internal solution used in the experiments above, by lowering the intracellular [Ca2+] and artificially increasing the Ca2+ buffering, exacerbates an underlying Ca2+ signalling abnormality of mdx fibres. To test this possibility, we recorded AP-evoked Ca2+ transients in the absence of EGTA from normal and mdx fibres. In order to block contraction without using EGTA, we bathed the fibre in 50 μm BTS, a potent and specific blocker of force production (Cheung et al. 2002; Shaw et al. 2003), 50 μm being the minimum concentration of this drug necessary to completely arrest movement of unstretched FDB fibres. While Cheung et al. (2002) and Shaw et al. (2003) reported no alteration in the Ca2+ signalling of frog muscle fibres exposed to BTS, it was important to verify that the properties of both the electrical and Ca2+ signals in mammalian fibres were unaltered by BTS. Thus, we first measured AP-evoked Ca2+ signals from normal and mdx FDB fibres using the conditions for Fig. 2 but in the presence of 50 μm BTS in the external solution (Fig. 3A and B). It can be observed that 50 μm BTS prolongs the decay phase of the AP in FDB fibres, which is lower than the concentration suggested by Cheung and collaborators which produces a similar effect in frog muscle fibres (Cheung et al. 2002). However, this prolongation does not seem to significantly affect the properties of evoked Ca2+ signalling in mammalian muscle fibres. The results from these and other experiments demonstrate that (ΔF/F)peak and the kinetic parameters of OGB-5N fluorescence transients recorded from normal and mdx fibres in the presence of 5 mm EGTA and 50 μm BTS do not differ from those of transients recorded in the absence of BTS (compare legends of Fig. 3A and B and Fig. 2A and B). Therefore, the results obtained from FDB fibres in the presence of 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution, both with and without BTS, were pooled together in Table 1.

Fig. 3. 1AP-evoked OGB-5N global fluorescent transients from normal and mdx single FDB fibres recorded in the presence of 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution and 50 μm extracellular BTS.

A, AP (black) and evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from a 14-week-old normal mouse FDB fibre. ΔF/Fpeak= 0.95, tp= 2.1 ms, FDHM = 3.7 ms, τfast= 1.9 ms, τslow= 17 ms, A1= 0.73, A2= 0.25. Fibre diameter = 30 μm. Resting Vm=−96 mV. B, AP (black) and evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from a 13-week-old mdx mouse FDB fibre. ΔF/Fpeak= 0.43, tp= 2.0 ms, FDHM = 3.9 ms, τfast= 1.9 ms, τslow= 14 ms, A1= 0.3, A2= 0.09. Fibre diameter = 31 μm. Resting Vm=−92 mV. The black dashed lines in all panels are the corresponding two-exponential fits to the fluorescence data. For all panels, t = 0 corresponds to the onset of stimulation.

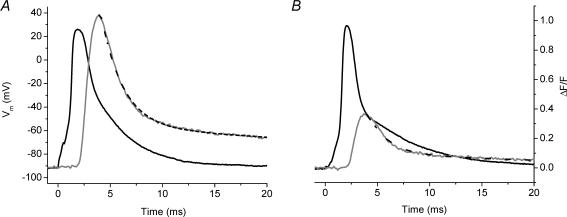

The importance of the preceding observations is that they show BTS does not alter AP-induced Ca2+ release, thus allowing us to examine whether AP-evoked Ca2+ transients recorded from mdx fibres were altered with respect to those of normal fibres in the absence of EGTA. Figure 4A shows superimposed traces of the membrane AP and the evoked OGB-5N transient recorded from a normal FDB fibre in the absence of EGTA in the internal solution and in the presence of 50 μm BTS in the extracellular solution. As expected, in the absence of EGTA the OGB-5N transient displayed a larger (ΔF/F)peak (1.1) and a longer FDHM (8.5 ms) than in its presence, while tp was quite similar (for comparison see Fig. 2A). In addition, both τfast and τslow (1.9 and 29 ms, respectively) were longer than in the presence of EGTA. This trend is also seen in the transient recorded under similar conditions from an mdx FDB fibre (Fig. 4B). The (ΔF/F)peak was 0.53, which is a 55% decrease compared to that of the normal transient (Fig. 4A), and parallels values observed in the presence of high [EGTA] (Fig. 2A and B). Surprisingly, while the tp and τfast (see figure legend for values) of this transient were similar to those of the normal fibre shown in Fig. 4A, the FDHM (53 ms) and τslow (109 ms) of the mdx transient were significantly longer than the corresponding values of the normal transient (Fig. 4A). These data suggest that mdx fibre transients differ from normal not only in (ΔF/F)peak, but also in the decay phase. The two transients are shown superimposed in Fig. 4C to illustrate that at late times (>25 ms), the ΔF/F transient from the mdx fibre was higher than that of the normal fibre, even though its (ΔF/F)peak was smaller.

Fig. 4. AP-evoked OGB-5N global fluorescent transients from normal and mdx single FDB fibres recorded in the absence of EGTA and in the presence of 50 μm extracellular BTS.

A, AP (black) and evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from a 13-week-old normal mouse FDB fibre. ΔF/Fpeak= 1.13, tp= 2.0 ms, FDHM = 8.52 ms, τfast= 1.9 ms, τslow= 29 ms, A1= 0.54, A2= 0.53 Fibre diameter = 28 μm. Resting Vm=−92 mV. B, AP (black) and evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from an 8-week-old mdx mouse FDB fibre. ΔF/Fpeak= 0.53, tp= 2.4 ms, FDHM = 53 ms, τfast= 2.1 ms, τslow= 109 ms, A1= 0.14, A2= 0.41. Fibre diameter = 29 μm. Resting Vm=−94 mV. C, the normal (black) and the mdx (grey) ΔF/F transients shown in Fig. 4A and B are shown superimposed. The black dashed lines in panels A and B are the corresponding two-exponential fits to the fluorescence data. For all panels, t = 0 corresponds to the onset of stimulation.

Table 2 presents a summary of the properties of the OGB-5N transients obtained without EGTA from mdx and normal FDB fibres. Overall, it can be observed that there is a highly significant 42 ± 4% decrease in the (ΔF/F)peak of mdx fibres under these conditions, which is not statistically different from that observed for OGB-5N transients in the presence of 5 mm EGTA (P > 0.5). In contrast to the finding for OBG-5N transients with 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution (Table 1), the FDHMs of mdx fibre transients recorded in the absence of EGTA were significantly longer than their normal counterparts (P < 0.0001, Table 2). Since both the tp values and the τfast values of the mdx transients recorded in the absence of EGTA were similar to those of the normal fibre transients (Table 2), while the τslow and the ratio Aslow/Afast were significantly larger (by 3.0 ± 0.8 and 1.9 ± 0.1 times, respectively; P < 0.05), this lengthening of the FDHM can most easily be explained by a prolongation of the slow component of the decay phase.

Table 2. OGB-5N transient parameters and peak [Ca2+] for normal and mdx muscle fibres in the absence of EGTA.

| (ΔF/F)peak | Peak [Ca2+] (μm) | tp (ms) | FDHM (ms) | τ1 (ms) | τ2 (ms) | Aslow/Afast | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal FDB | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 8.0 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 37 ± 3 | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

| mdx FDB | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 48 ± 6 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 113 ± 18 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

For experiments, fluorescence transient parameters and peak [Ca2+] were obtained from n= 5 FDB fibres from 2 normal mice and n= 11 fibres from 2 mdx mice. All transients were obtained with 5 mm total [Mg2+].

Statistical significance between normal and mdx FDB fibres (P < 0.05);

statistical significance between normal and mdx FDB fibres (P < 0.0001)

Calculation of the peak [Ca2+] in response to AP stimulation

Making the assumption that OGB-5N is able to track accurately the changes in free [Ca2+] during an AP-evoked SR Ca2+ release, we calculated (see Methods) the peak myoplasmic free [Ca2+] which yields the measured (ΔF/F)peak of the transients and these values are shown in Table 1 (column 3) and Table 2 (column 2). From these data, we calculated that the myoplasmic free peak [Ca2+] was decreased by 46 ± 9 and 45 ± 4% in the presence of 5 and 0 mm EGTA in internal solution for mdx FDB fibres, and 54 ± 13% for mdx EDL fibres in the presence of 5 mm EGTA in the cut ends, compared to the respective normal counterparts.

AP-evoked fluorescence transients recorded with a high affinity Ca2+ indicator from FDB fibres

In contrast to the significant decrease in the amplitude of AP-evoked Ca2+ signals in mdx compared to normal fibres described above, previous studies have reported that Ca2+ transients were similar in the two strains of mice (Turner et al. 1991; Head, 1993; Tutdibi et al. 1999). However, all these studies used high affinity Ca2+ indicators (Fura-2 and Indo-1) in the absence of EGTA to measure Ca2+ transients. In an attempt to emulate these conditions, we examined the properties of AP-evoked Ca2+ signals in FDB fibres loaded with 50 μm OGB-1, a closely related analogue of OGB-5N with a significantly higher affinity for Ca2+ (see Methods), and no EGTA. It was necessary to include 50 μm BTS in the external solution to block contraction, as discussed above (Fig. 3). Panels A and B in Figure 5 show an AP superimposed on the evoked OGB-1 fluorescence transient from a normal and an mdx FDB fibre, respectively, recorded under these conditions. In agreement with our OGB-5N results in 0 EGTA (Fig. 4), the (ΔF/F)peak of the OGB-1 transient was smaller in an mdx fibre (Fig. 5B) than in a normal fibre (Fig. 5A). As expected, though, because of the slowness of the indicator, the time course of both transients was longer (see Fig. 5 legend for values) than the corresponding OGB-5N transients (Fig. 4A and B). In addition, it can be observed that in the case of the normal fibre, the transient decays with an early sloping plateau phase followed by a late decay, findings which are consistent with the possibility that OGB-1 is near saturation at the peak of the transient. These misrepresentations of the time course of the underlying Ca2+ signals makes a comparison between normal and mdx OGB-1 transients less valuable. For example, the clear prolongation in the FDHM of OGB-5N transients from mdx fibres without EGTA in the internal solution (Table 2, column 2) is no longer significantly manifested in OGB-1 transients recorded under similar conditions (50 ± 6 ms versus 68 ± 11 ms, n = 5 fibres from 2 normal mice versusn = 6 fibres from 2 mdx mice, respectively). Nevertheless, in agreement with all of the other data in this report, we found that OGB-1 transients from mdx fibres displayed a highly significant 36 ± 6% (P < 0.0001) decrease in the (ΔF/F)peak compared to that of normal transients (n values as above for normal and mdx experiments).

Fig. 5. AP and evoked OGB-1 global transients from normal and mdx FDB fibres.

A, superimposed AP (black) and evoked OGB-1 fluorescence transient (grey) from a 16-week-old normal FDB fibre loaded with 0.05 mm OGB-1 and in the presence of 50 μm extracellular BTS. (ΔF/F)peak= 2.7, tp= 4.32 ms, FDHM = 50 ms. Fibre diameter = 31 μm. B, superimposed AP (black) and evoked OGB-5N fluorescence transient (grey) from a 12-week-old mdx FDB fibre loaded with 0.05 mm OGB-1 and in the presence of 50 μm extracellular BTS. (ΔF/F)peak= 1.7, tp= 8.0 ms, FDHM = 65 ms. Fibre diameter = 29 μm. For all panels, t = 0 corresponds to the onset of stimulation.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of DMD is poorly understood. In particular, the weakness observed in isolated fibres from mdx mice and DMD patients has not been fully explained (Emery, 1993; Watchko et al. 2002). These results could be explained by lower evoked myoplasmic free [Ca2+] changes in dystrophic fibres. In contrast to previous reports (Turner et al. 1991; Head, 1993; Tutdibi et al. 1999), we demonstrate that mdx skeletal muscle fibres display a significant impairment in AP-evoked SR Ca2+ signalling which may provide a mechanism for the observed contractile dysfunction of these mice, and potentially for impaired force production of humans afflicted with DMD.

We began these studies using FDB muscles fibres obtained by collagenase dissociation since this afforded us high yields of twitching normal and mdx fibres. Since these FDB fibres are too short for gap isolation procedures, we developed a microelectrode-based technique for electrical and fluorescence recording. Similar to an approach used previously (Eusebi et al. 1980), we used two microelectrodes, one for loading the fibre with internal solution and passing current and the second for recording Vm without distortion.

In order to achieve accurate measurements of both optical and electrical signals, it was critical that fibre movement was arrested. To accomplish this, we used two different approaches. On the one hand, we included millimolar concentrations of EGTA in the internal solution for FDB fibres (or in the cut ends for EDL fibres). It has been reported previously that high intracellular [EGTA] reduces the amplitude, accelerates the time course, and constrains the free myoplasmic [Ca2+] changes to narrow regions circumscribing the Ca2+ release sites (Pape et al. 1995; DiGregorio et al. 1999; Novo et al. 2003). Empirically, the results reported here confirm these facts since fibres electrically stimulated in the absence of EGTA contracted vigorously, while those in the presence of ≥ 5 mm EGTA did not contract. Thus, the relatively large calculated [Ca2+] changes in the presence of EGTA (up to 4 μm peak [Ca2+]) reported above did not occur throughout the myofibril and/or were brief enough to prevent the effective activation of the Ca2+ dependent conformational change by troponin in the region of actin/myosin overlap. Indeed, since the measured fluorescence change arises from small regions of the myofibril, whereas the baseline fluorescence arises from the entire myofibril, it is likely that the true local value of the peak [Ca2+] is significantly larger than the values reported in Table 1. Second, for experiments done in the absence of EGTA, we pharmacologically blocked contraction by adding BTS, a specific inhibitor of the muscle myosin ATPase (Cheung et al. 2002), to the extracellular solution. We extended the study by Cheung and collaborators by demonstrating that BTS is also an effective blocker of AP-evoked contraction in mammalian muscle fibres at a concentration of 50 μm without having any obvious impact on Ca2+ signalling of these fibres. It is worth noting, however, that an ∼3-fold increase in the current necessary to maintain the resting Vm, and a prolongation of the falling phase of the AP was observed under these conditions.

A key finding of this report is that the amplitude of the AP-evoked OGB-5N transients of mdx muscle fibres was significantly decreased by ∼40% compared to normal fibres with no difference in the AP. This decrease was observed in the presence and absence of intracellular EGTA, and therefore presumably at different resting free myoplasmic [Ca2+], as well as with high and low affinity indicators. Moreover, this decrement in the Ca2+ signalling of FDB fibres from mdx mice was also observed in EDL fibres loaded with 5 mm EGTA. Another major finding was that in the absence of EGTA, the decay phase of Ca2+ transients from mdx FDB fibres was significantly prolonged compared to normal fibres, in agreement with a previous report using a high affinity indicator (Turner et al. 1988). It should be emphasized that since there was no difference between our measurements of the surface AP in normal and mdx fibres, these alterations in AP-evoked Ca2+ signalling were measured in electrically indistinguishable populations of fibres. Moreover, all of our experiments were done in animals between 8 and 18 weeks of age, which corresponds to the postnecrotic phase of the mdx phenotype (McArdle et al. 1995). We found that within this age range there is little dispersion in the properties of the AP-evoked Ca2+ transients, as evidenced by the small value of the s.e.m. within each strain of mouse (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, we believe that the measured alterations in mdx Ca2+ signalling represent a physiologically relevant impairment in the excitation–contraction (EC) coupling process of dystrophic mice.

As mentioned above, this report contradicts a number of previous reports on mdx muscle AP Ca2+ signalling (Turner et al. 1988; Head, 1993; Tutdibi et al. 1999). In our view, these studies have a number of limitations which may affect the findings. First, these studies used high affinity indicators which may not have been able to track accurately in skeletal muscle fibres rapid [Ca2+] changes (Hirota et al. 1989; Escobar et al. 1997). To test whether a similar high affinity indicator missed the depression in the (ΔF/F)peak of mdx fibres observed using OGB-5N, we repeated our measurements using the high affinity indicator OGB-1 in the absence of EGTA (Fig. 5A and B). The ΔF/F transients obtained from normal fibres using OGB-1 (Fig. 5A) suggest that the myoplasmic free [Ca2+] changes in response to AP stimulation in these fibres are large enough to approach the region of saturation for OGB-1. However, we still observed a similar reduction in the (ΔF/F)peak of the mdx fibre transients under these conditions. Second, two of the previous studies presented calibrated Ca2+ transients obtained with Fura-2 and Indo-1 using an equation (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985) which assumes that the dye is at equilibrium with the free [Ca2+] (Turner et al. 1988; Head, 1993). This assumption is known to be in error for high affinity indicators (Escobar et al. 1997). Because of this error, we chose not to deconvolve the OGB-1 transients using similar assumptions, but we did so for the low affinity indicator OGB-5N since it has been demonstrated to be at near equilibrium with AP-evoked free [Ca2+] changes (Escobar et al. 1997). Thus, it is not possible for us to compare directly our high affinity transients with theirs. Nevertheless, we calculated peak [Ca2+] for normal and mdx fibres of 6.0 and 3.3 μm, respectively, in 0 EGTA (Table 2, columns 2 and 3). These values are up to 10-fold higher than those previously published for comparisons between mdx and normal fibres (Turner et al. 1991; Head, 1993; Tutdibi et al. 1999). In fact, our prediction for the peak [Ca2+] in mdx fibres in response to AP stimulation is considerably higher than those reported for normal fibres in these previous studies. In addition, our values are more in line with values reported for mammalian muscle fibres using low affinity indicators (Delbono & Stefani, 1993; Hollingworth et al. 1996). Another weakness of these studies is that they did not provide simultaneous measurements of the AP and the evoked Ca2+ signals (Turner et al. 1988; Head, 1993; Tutdibi et al. 1999). We measured both of these signals simultaneously and found that the surface AP is not altered in mdx fibres. This observation extends previous findings that both the passive electrical properties (Hollingworth et al. 1990) and the major conductances responsible for the AP are similar in the two strains of mice (Mathes et al. 1991; Hocherman & Bezanilla, 1996).

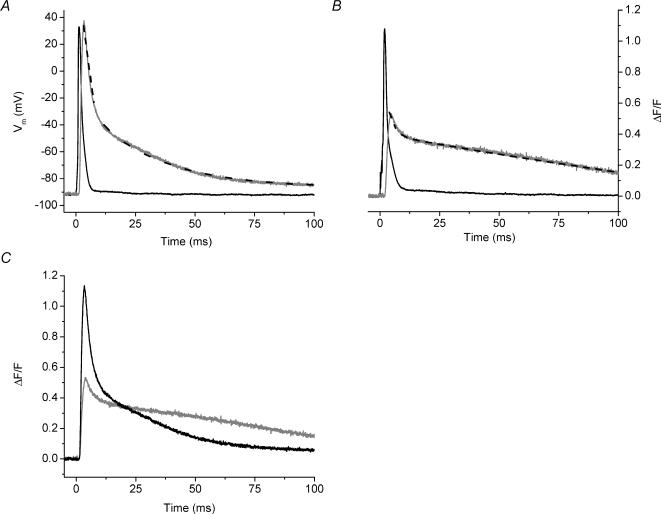

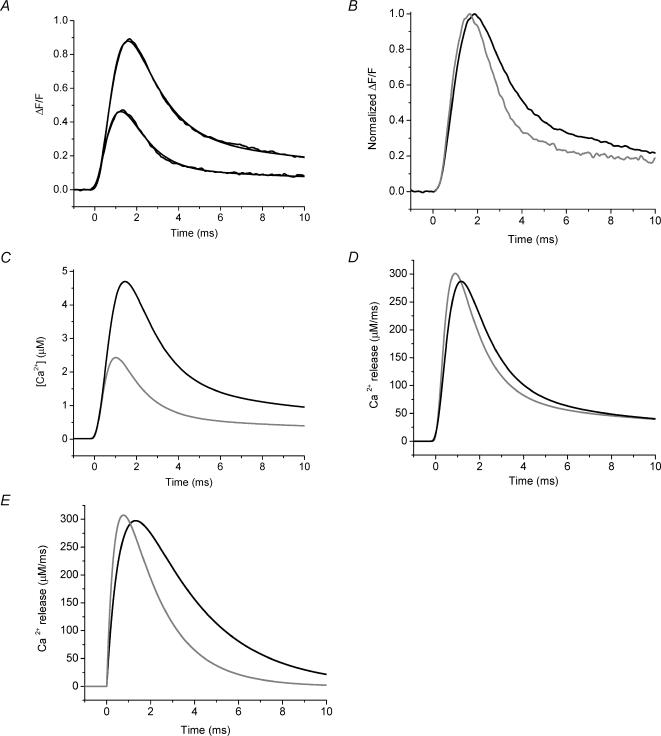

Because the impairments in Ca2+ signalling of mdx fibres we have reported here could result from an alteration in the evoked SR Ca2+ release time course and/or the Ca2+ buffering/sequestration properties of these fibres, it is important to clarify the potential contributions of these two processes. It is worth emphasizing that, along with blocking contraction, another advantage of using high EGTA to study AP-evoked Ca2+ transients is that the endogenous buffering capacity of the fibres can be dominated. In turn, under this condition, the measured Ca2+ transient is representative of the AP-evoked SR Ca2+ release flux and, thus, any differences between the transients of normal and mdx mice represent differences in the properties of the release flux alone. The validity of this approach has been demonstrated in cardiac and skeletal muscle by using high intracellular [EGTA] and OGB-5N (Song et al. 1998; DiFranco et al. 2002; Novo et al. 2003). As discussed in the Methods section, it is unlikely that the [EGTA] in the impaled fibre in these studies was able to reach the pipette [EGTA]. However, the dramatic reduction of the FDHM for OGB-5N transients measured in the presence of 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution (Table 1), compared with the values in the absence of EGTA (Table 2), along with the concomitant blockage of contraction, suggests that a situation is reached where the exogenous buffer overwhelms the endogenous buffering capacity of the fibre. To assess this more directly, we compared the rates of release predicted by our kinetic model for the two internal solution EGTA concentrations. Figure 6A shows superimposed representative AP-evoked OGB-5N transients recorded from normal FDB fibres in the presence of 5 mm (larger black trace) and 10 mm (smaller black trace) EGTA. The (ΔF/F)peak in 10 mm EGTA was decreased by 53% compared with that in 5 mm EGTA. Figure 6B shows the ΔF/F transients presented in Fig. 6A normalized to their respective maxima. Since the time courses of these two transients are similar, but much faster than those observed in the absence of EGTA (see Fig. 4A and Table 2), it is possible to suggest that 5 mm EGTA in the internal solution may be sufficient to unmask the time course of the flux itself. In order to more quantitatively analyse this possibility, ΔF/F transients were simulated by our kinetic model (see Methods) using adjustable Ca2+ release waveforms. Results designed to simulate the measured ΔF/F traces are superimposed on these experimental data (Fig. 6A). The predicted free [Ca2+] changes are shown in Fig. 6C. As expected, the model predicted smaller free [Ca2+] changes for the higher [EGTA] used but, importantly, the predicted fluxes for the 5 and 10 mm conditions were very similar (Fig. 6D). Moreover, when this analysis was performed using the analytical approximation of Song and collaborators (eqn (5) in Song et al. 1998), the predicted Ca2+ release fluxes were also very similar to each other and to our model predictions (compare Figs 6D and 6E). While the absolute values of the fluxes may be incorrect because of the uncertainty about the exact myoplasmic [EGTA], it is clear that the kinetics of the OGB-5N ΔF/F transients measured with 5 mm[EGTA] in the internal solution approximate the underlying AP-evoked SR Ca2+ release flux. Therefore, the decrease in the amplitude of the AP-evoked Ca2+ transients observed in mdx mice in the presence of high [EGTA] (Figs 2B and 3B) reflects an intrinsic impairment in the AP-evoked SR Ca2+ release flux of these mice. By deconvolving these ΔF/F transients using our kinetic model, we calculate that the AP-evoked SR Ca2+ release flux goes from 230 ± 22 μm ms−1 in normal fibres to 125 ± 12 μm ms−1 in mdx fibres (n = 12 fibres from 7 normal mice, n = 17 fibres from 7 mdx mice), which represents a 46 ± 9% flux reduction in dystrophic fibres. We can infer that, most likely, this decrement in the flux is also the cause of the decreased signals observed in 0 EGTA (Figs 4 and 5), but model simulations for this case will depend on the dynamic endogenous buffering in these fibres which, at present, has not been quantitatively characterized (see below).

Fig. 6. AP-evoked and simulated OGB-5N global transients from normal FDB fibre at different EGTA concentrations.

A, AP-evoked OGB-5N transients recorded in the presence of 5 and 10 mm EGTA (larger and smaller black traces, respectively). The data were fitted to the predictions (grey traces) from a single compartment model in which the concentrations of OGB-5N and [EGTA] were those use in the experiments. The Ca2+ release function is described in the Methods. The fitted parameters (Jmax, N, τ1, τ2, τ3, τ4, A1, A2, A3) were, respectively, 103 μm ms−1, 4.6, 0.5 ms, 1.3 ms, 1.2 ms, 13.4 ms, 3.8, 5, 0.9 for the 5 mm transient and 149 μm ms−1, 5, 0.3 ms, 4 ms, 1.5 ms, 22 ms, 0.1, 3.8, 0.4 for the 10 mm transient. B, same ΔF/F transients as shown in Fig. 6A without fits shown normalized to their respective (ΔF/F)peaks. C, model predictions for the [Ca2+] changes in 5 mm (larger black trace) and 10 mm (smaller grey trace) EGTA as calculated from the single compartment model. D, Ca2+ release fluxes associated with the [Ca2+] change in 5 mm (black) and 10 mm (grey) EGTA presented in C, as calculated from the single compartment model. E, Ca2+ release fluxes associated with the [Ca2+] change in 5 mm (black) and 10 mm (grey) EGTA presented in C, as calculated from eqn (5) of Song et al. (1998). For A, APs were recorded but are not shown. For all panels, t = 0 corresponds to the start of each transient.

Since we measured spatially averaged, multisarcomeric, Ca2+ signals, we cannot distinguish between the possibilities that all of the Ca2+‘release units’ are impaired to the same degree, or that there is a mixture of functioning and non-functioning units in different sarcomeres of mdx fibres. To evaluate these possibilities, a detailed exploration of the spatio-temporal evolution of the [Ca2+] changes with intrasarcomeric resolution, akin to what we have accomplished previously in amphibian fibres (DiFranco et al. 2002; Novo et al. 2003), will be required for normal and mdx fibres. It will also be important to identify where in the cascade of events responsible for EC coupling the impairment occurs. It seems unlikely that the voltage sensitivity of the release process is different in mdx mice since we observed no difference in the kinetics of the Ca2+ transients in 5 mm EGTA (which approximate the kinetics of the release process) (Figs 2 and 3, Table 1) and since charge movements have been reported to be normal in dystrophic fibres (Hollingworth et al. 1990). Thus, it is intriguing to suggest that the cause of the reduced AP-evoked Ca2+ release reported here for mdx fibres occurs after the voltage-dependent coupling at the triads and there is both biochemical and physiological evidence in support of this possible explanation (Hoffman et al. 1987b; Knudson et al. 1988; Culligan et al. 2002; Friedrich et al. 2003). Alternatively, an explanation for this impairment may be that the T-tubule system is altered in mdx mice and we are currently investigating this issue.

The longer decay phase of mdx fibres observed with both indicators in the absence of intracellular EGTA (Fig. 4) suggests that mdx and normal fibres have different mechanisms of myoplasmic Ca2+ binding and/or subsequent sequestration by the SR. A possible explanation for the prolongation of the decay phase is the reduction in the parvalbumin protein content of mdx fibres, as reported previously (Sano et al. 1990), a decrease which has been reported for other adult dystrophic muscles as well (Klug et al. 1985). In addition, or alternatively, our results could be explained by the apparent reduction in the maximal velocity of Ca2+ transport by the SR Ca2+ pump in mdx mice (Kargacin & Kargacin, 1996). Fibres from mdx mice have been reported to have a higher proportion of slow (type I) fibres (Petrof et al. 1993) and it could be argued that the prolongation of the decay phase of mdx transients reported here is representative of this. We feel that this is unlikely, however, since the prolongation in the decay phase of the mdx fibre transients compared to normal fibre transients, recorded using OGB-5N in the absence of EGTA, is much greater than that shown in a previous study for slow fibres compared to fast fibres (Baylor & Hollingworth, 2003). Moreover, since BTS was effective at relatively low concentrations, it is likely that the mdx fibres used here were fast-twitch fibres, since slow-twitch fibres express the β-forms of myosin II, which is much less sensitive to BTS (Cheung et al. 2002). It is clear, however, that this alteration of Ca2+ signalling in mdx fibres is hidden when experiments are performed with 5 mm EGTA in internal solution since the kinetics of the transients from normal and mdx fibres are statistically similar under this condition (Table 1 and Figs 2 and 3). Whatever the cause, the prolongation of the decay phase of the AP-evoked Ca2+ transient of mdx fibres may explain the lengthening of the relaxation time of dystrophic muscle contraction (Parslow & Parry, 1981; Bressler et al. 1983; Dangain & Vrbova, 1984).

Finally, it will be important to examine AP-evoked SR Ca2+ release in fibres of young mdx mice (< 4 weeks of age) which are in the prenecrotic phase of development (Head et al. 1992; Gillis, 1999; Durbeej & Campbell, 2002) in order to clarify whether the pathophysiology caused by the absence of dystrophin leads to the impaired AP-evoked Ca2+ signalling we have observed either directly or indirectly by affecting the subsequent development muscle fibres in mdx mice.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank A. Grinnell and J. Tidball for their helpful comments and discussions on a previous version of the manuscript. We would also like to thank B. Criswell for help with muscle fibre preparation and G. Faas for help with in vitro[Ca2+] calibrations. C.E.W. was partially supported by National Institutes of Health Training Grant GM08042 (UCLA MSTP). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AR25201 and AR47664, a Grant in Aid from the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and a UC MEXUS grant to J.L.V., and a National Science and Engineering Research Council fellowship PGSB-242387- 2001, Canada, to D.N.

References

- Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release compared in slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibres of mouse muscle. J Physiol. 2003;551:125–138. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM, Patton CW, Nuccitelli R. A practical guide to the preparation of Ca2+ buffers. Meth Cell Biol. 1994;40:3–29. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressler BH, Jasch LG, Ovalle WK, Slonecker CE. Changes in isometric contractile properties of fast-twitch and slow-twitch skeletal muscle of C57BL/6J dy2J/dy2J dystrophic mice during postnatal development. Exp Neurol. 1983;80:457–470. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(83)90297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung A, Dantzig JA, Hollingworth S, Baylor SM, Goldman YE, Mitchison TJ, Straight AF. A small-molecule inhibitor of skeletal muscle myosin II. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:83–88. doi: 10.1038/ncb734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coirault C, Lambert F, Marchand-Adam S, Attal P, Chemla D, Lecarpentier Y. Myosin molecular motor dysfunction in dystrophic mouse diaphragm. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:C1170–C1176. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.6.C1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culligan K, Banville N, Dowling P, Ohlendieck K. Drastic reduction of calsequestrin-like proteins and impaired calcium binding in dystrophic mdx muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:435–445. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00903.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangain J, Vrbova G. Muscle development in mdx mutant mice. Muscle Nerve. 1984;7:700–704. doi: 10.1002/mus.880070903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbono O, Stefani E. Calcium transients in single mammalian skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1993;463:689–707. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranco M, Novo D, Vergara J. Characterization of the calcium release domains during excitation contraction coupling in skeletal muscle fibres. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:508–519. doi: 10.1007/s004240100719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGregorio DA, Peskoff A, Vergara JL. Measurement of action potential-induced presynaptic calcium domains at a cultured neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7846–7859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07846.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej M, Campbell KP. Muscular dystrophies involving the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex: an overview of current mouse models. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:349–361. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AEH. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Emery AE. The muscular dystrophies. Lancet. 2002;359:687–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar AL, Cifuentes F, Vergara JL. Detection of Ca(2+)-transients elicited by flash photolysis of DM-nitrophen with a fast calcium indicator. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar AL, Velez P, Kim AM, Cifuentes F, Fill M, Vergara JL. Kinetic properties of DM-nitrophen and calcium indicators: rapid transient response to flash photolysis. Pflugers Arch. 1997;434:615–631. doi: 10.1007/s004240050444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eusebi F, Miledi R, Takahashi T. Calcium transients in mammalian muscles. Nature. 1980;284:560–561. doi: 10.1038/284560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink RH, Stephenson DG, Williams DA. Physiological properties of skinned fibres from normal and dystrophic (Duchenne) human muscle activated by Ca2+ and Sr2+ J Physiol. 1990;420:337–353. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich O, Both M, Gillis JM, Chamberlain JS, Fink RH. Mini-dystrophin restores L-type calcium currents in skeletal muscle of transgenic mdx mice. J Physiol. 2003;555:251–265. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.054213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis JM. Understanding dystrophinopathies: an inventory of the structural and functional consequences of the absence of dystrophin in muscles of the mdx mouse. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1999;20:605–625. doi: 10.1023/a:1005545325254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt RE. Calcium-activated tension of skinned muscle fibers of the frog. Dependence on magnesium adenosine triphosphate concentration. J General Physiol. 1974;63:722–739. doi: 10.1085/jgp.63.6.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head SI. Membrane potential, resting calcium and calcium transients in isolated muscle fibres from normal and dystrophic mice. J Physiol. 1993;469:11–19. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head SI, Stephenson DG, Williams DA. Properties of enzymatically isolated skeletal fibres from mice with muscular dystrophy. J Physiol. 1990;422:351–367. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Head SI, Williams DA, Stephenson DG. Abnormalities in structure and function of limb skeletal muscle fibres of dystrophic mdx mice. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1992;248:163–169. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1992.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B, Campbell DT. An improved vaseline gap voltage clamp for skeletal muscle fibers. J General Physiol. 1976;67:265–293. doi: 10.1085/jgp.67.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota A, Chandler WK, Southwick PL, Waggoner AS. Calcium signals recorded from two new purpurate indicators inside frog cut twitch fibers. J General Physiol. 1989;94:597–631. doi: 10.1085/jgp.94.4.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocherman SD, Bezanilla F. A patch-clamp study of delayed rectifier currents in skeletal muscle of control and mdx mice. J Physiol. 1996;493:113–128. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Jr, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell. 1987a;51:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman EP, Knudson CM, Campbell KP, Kunkel LM. Subcellular fractionation of dystrophin to the triads of skeletal muscle. Nature. 1987b;330:754–758. doi: 10.1038/330754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth S, Marshall MW, Robson E. Excitation contraction coupling in normal and mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 1990;13:16–20. doi: 10.1002/mus.880130105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth S, Zhao M, Baylor SM. The amplitude and time course of the myoplasmic free [Ca2+] transient in fast-twitch fibers of mouse muscle. J General Physiol. 1996;108:455–469. doi: 10.1085/jgp.108.5.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kargacin ME, Kargacin GJ. The sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium pump is functionally altered in dystrophic muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1290:4–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(95)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AM, Vergara JL. Fast voltage gating of Ca2+ release in frog skeletal muscle revealed by supercharging pulses. J Physiol. 1998;511:509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.509bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klug G, Reichmann H, Pette D. Decreased parvalbumin contents in skeletal muscles of C57BL/6J (dy2J/dy2J) dystrophic mice. Muscle Nerve. 1985;8:576–579. doi: 10.1002/mus.880080706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson CM, Hoffman EP, Kahl SD, Kunkel LM, Campbell KP. Evidence for the association of dystrophin with the transverse tubular system in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8480–8484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle A, Edwards RH, Jackson MJ. How does dystrophin deficiency lead to muscle degeneration?– evidence from the mdx mouse. Neuromuscul Disord. 1995;5:445–456. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(95)00001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathes C, Bezanilla F, Weiss RE. Sodium current and membrane potential in EDL muscle fibers from normal and dystrophic (mdx) mice. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:C718–C725. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.4.C718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias RT, Cohen IS, Oliva C. Limitations of the whole cell patch clamp technique in the control of intracellular concentrations. Biophys J. 1990;58:759–770. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82418-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maylie J, Irving M, Sizto NL, Chandler WK. Comparison of arsenazo III optical signals in intact and cut frog twitch fibers. J General Physiol. 1987;89:41–81. doi: 10.1085/jgp.89.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer W, Rios E, Schneider MF. A general procedure for determining the rate of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1987;51:849–863. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83413-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagerl UV, Novo D, Mody I, Vergara JL. Binding kinetics of calbindin-D (28k) determined by flash photolysis of caged Ca(2+) Biophys J. 2000;79:3009–3018. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76537-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novo D, DiFranco M, Vergara JL. Comparison between the predictions of diffusion-reaction models and localized Ca2+ transients in amphibian skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 2003;85:1080–1097. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74546-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade P, Vergara J. Arsenazo III and antipyrylazo III calcium transients in single skeletal muscle fibers. J General Physiol. 1982;79:679–707. doi: 10.1085/jgp.79.4.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape PC, Jong DS, Chandler WK. Calcium release and its voltage dependence in frog cut muscle fibers equilibrated with 20 mM EGTA. J General Physiol. 1995;106:259–336. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry DJ, Parslow HG. Fiber type susceptibility in the dystrophic mouse. Exp Neurol. 1981;73:674–685. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(81)90204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parslow HG, Parry DJ. Slowing of fast-twitch muscle in the dystrophic mouse. Exp Neurol. 1981;73:686–699. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(81)90205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrof BJ, Stedman HH, Shrager JB, Eby J, Sweeney HL, Kelly AM. Adaptations in myosin heavy chain expression and contractile function in dystrophic mouse diaphragm. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C834–C841. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.3.C834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch M, Neher E. Rates of diffusional exchange between small cells and a measuring patch pipette. Pflugers Arch. 1988;411:204–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00582316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymackers JM, Gailly P, Schoor MC, Pette D, Schwaller B, Hunziker W, Celio MR, Gillis JM. Tetanus relaxation of fast skeletal muscles of the mouse made parvalbumin deficient by gene inactivation. J Physiol. 2000;527:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano M, Yokota T, Endo T, Tsukagoshi H. A developmental change in the content of parvalbumin in normal and dystrophic mouse (mdx) muscle. J Neurol Sci. 1990;97:261–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(90)90224-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw MA, Ostap EM, Goldman YE. Mechanism of inhibition of skeletal muscle actomyosin by N-benzyl-p-toluenesulfonamide. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6128–6135. doi: 10.1021/bi026964f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L-S, Sham JSK, Stern MD, Lakatta EG, Cheng H. Direct measurement of SR release flux by tracking ‘Ca spikes’ in rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 1998;512:677–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.677bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szentesi P, Jacquemond V, Kovacs L, Csernoch L. Intramembrane charge movement and sarcoplasmic calcium release in enzymatically isolated mammalian skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1997;505:371–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.371bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner PR, Fong PY, Denetclaw WF, Steinhardt RA. Increased calcium influx in dystrophic muscle. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1701–1712. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner PR, Westwood T, Regen CM, Steinhardt RA. Increased protein degradation results from elevated free calcium levels found in muscle from mdx mice. Nature. 1988;335:735–738. doi: 10.1038/335735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutdibi O, Brinkmeier H, Rudel R, Fohr KJ. Increased calcium entry into dystrophin-deficient muscle fibres of MDX and ADR-MDX mice is reduced by ion channel blockers. J Physiol. 1999;515:859–868. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.859ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara J, DiFranco M. Imaging of calcium transients during excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle fibers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;311:227–236. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3362-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara JL, DiFranco M, Novo D. Dimensions of calcium release domains in frog skeletal muscle fibers. Proc SPIE. 2001;4259:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZM, Messi ML, Delbono O. Patch-clamp recording of charge movement, Ca(2+) current, and Ca(2+) transients in adult skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1999;77:2709–2716. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77104-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watchko JF, O'Day TL, Hoffman EP. Functional characteristics of dystrophic skeletal muscle: insights from animal models. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:407–417. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01242.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood DS, Sorenson MM, Eastwood AB, Charash WE, Reuben JP. Duchenne dystrophy: abnormal generation of tension and Ca++ regulation in single skinned fibers. Neurology. 1978;28:447–457. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.5.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CE, Novo D, Vergara J. Global calcium transients in normal and dystrophic muscle fibers. Biophysical Society Meeting. 2003;84:572a. [Google Scholar]

- Woods CE, Vergara JL. A combined method for confocal detection of Ca2+ signals and fluorescence-recovery-after-photobleaching (FRAP) Biophys J (Annu Meeting Abstracts) 2002;82:278a. [Google Scholar]