Abstract

Previous studies have documented the expression of four kinetically distinct voltage-gated K+ (Kv) currents, Ito,f, Ito,s, IK,slow and Iss, in mouse ventricular myocytes and demonstrated that Ito,f and Ito,s are differentially expressed in the left ventricular apex and the interventricular septum. The experiments here were undertaken to test the hypothesis that there are further regional differences in the expression of Kv currents or the Kv subunits (Kv4.2, Kv4.3, KChIP2, Kv1.5, Kv2.1) encoding these currents in adult male and female (C57BL6) mouse ventricles. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings revealed that mean (± s.e.m.) peak outward K+ current and Ito,f densities are significantly (P < 0.001) higher in cells isolated from the right (RV) than the left (LV) ventricles. Within the LV, peak outward K+ current and Ito,f densities are significantly (P < 0.05) higher in cells from the apex than the base. In addition, Ito,f and IK,slow densities are lower in cells isolated from the endocardial (Endo) than the epicardial (Epi) surface of the LV wall. Importantly, similar to LV apex cells, Ito,s is not detected in RV, LV base, LV Epi or LV Endo myocytes. No measurable differences in K+ current densities or properties are evident in RV or LV cells from adult male and female mice, although Ito,f, Ito,s, IK,slow and Iss densities are significantly (P < 0.01) higher, and action potential durations at 50% (APD50) are significantly (P < 0.05) shorter in male septum cells. Western blot analysis revealed that the expression levels of Kv4.2, Kv4.3, KChIP2, Kv1.5 and Kv2.1 are similar in male and female ventricles. In addition, consistent with the similarities in repolarizing Kv current densities, no measurable differences in ECG parameters, including corrected QT (QTc) intervals, are detected in telemetric recordings from adult male and female (C57BL6) mice.

In large mammals, it is well documented that there are marked regional variations in ventricular action potential waveforms, reflecting, at least in part, differences in the expression of repolarizing voltage-gated K+ (Kv) currents (Antzelevitch & Dumaine, 2002; Nerbonne & Kass, 2003). These differences impact on the normal spread of excitation and influence the dispersion of repolarization in the ventricles (Antzelevitch & Dumaine, 2002; Nerbonne & Guo, 2002). Changes in the densities, distributions or properties of Kv currents, such as occur in hypertrophied or failing myocardium (Näbauer and Käab, 1998; Tomaselli & Marbán, 1999), therefore, are expected to influence propagation and decrease rhythmicity, effects which could lead to increased dispersion of repolarization and to the development of life threatening ventricular arrhythmias (Fu et al. 1997; Wolk et al. 1999).

Ventricular repolarization, reflected in the QT interval in surface electrocardiographic (ECG) recordings, is longer in women than in men (Surawicz, 2001), and female sex is an important variable for risk stratification in individuals with inherited long QT syndromes (Priori et al. 2003). QT prolongation in women has been attributed to differences in early repolarization, suggesting a role for Kv currents, probably mediated by steroid hormones (Bidoggia et al. 2000). The increased incidence of drug-induced QT prolongation and ventricular arrhythmias in female rabbits (Liu et al. 1998; Lu et al. 2001) had also been attributed to hormone-dependent differences in Kv currents (Drici et al. 1998; Pham et al. 2001). In spite of the potential clinical importance of these observations, there have been relatively few studies focused on exploring the impact of sex on the functional expression of repolarizing, ventricular Kv currents (Drici et al. 1998; Leblanc et al. 1998; Trépanier-Boulay et al. 2001; Wu & Anderson, 2002).

In recent years, mice have been used increasingly in studies of the cardiovascular (and other) systems primarily because of the ease with which molecular genetic approaches can be exploited (Nerbonne et al. 2001). To facilitate phenotypic analysis of gene-targeted animals, as well as to evaluate the potential and limitations of mouse models, the physiology of the normal mouse heart needs to be understood in detail. Considerable progress has now been made in characterizing repolarizing Kv currents in the mouse and in identifying the molecular correlates of the underlying (Kv) channels (Barry et al. 1998; Fiset et al. 1998; London et al. 1998, 2001; Zhou et al. 1998; Guo et al. 1999, 2000, 2002; Xu et al. 1999a,b; Mitarai et al. 2000). Previous studies, for example, have identified four distinct Kv currents, Ito,f, Ito,s, IK,slow and Iss, in adult mouse (C57BL6) ventricles and demonstrated that Ito,f and Ito,s are differentially expressed in left ventricular (LV) apex and septum cells (Xu et al. 1999a).

The experiments here were undertaken to test the hypothesis that there are further heterogeneities in the expression of Kv currents and Kv subunits in adult male and female (C57BL6) mouse ventricles. The results presented demonstrate marked differences in peak outward K+ current and Ito,f densities in right ventricular (RV), LV apex and LV base cells, as well as in cells from the epicardial and endocardial surfaces of the LV wall. The Kv currents in RV and LV cells from adult male and female animals, however, are indistinguishable, and there are no sex differences in the expression of the Kv subunits (Kv4.2, Kv4.3, KChIP2, Kv1.5 and Kv2.1) encoding (C57BL6) mouse ventricular Kv channels (Barry et al. 1998; London et al. 1998, 2001; Guo et al. 1999, 2000, 2002; Xu et al. 1999b). Peak K+ current, as well as Ito,f, IK,slow, Ito,s, and Iss, densities, however, are lower in female septum cells, although no significant sex differences in ECG parameters, including QTc intervals, are observed.

Methods

All procedures for animal care and experimentation were approved by the Washington University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Myocyte isolation

For most of the experiments here, ventricular myocytes were isolated from adult (8–12 week) female (n = 23) and male (n = 8) C57BL6 mice (Jackson) by enzymatic dissociation and mechanical dispersion using previously described methods (Xu et al. 1999a,b; Guo et al. 1999, 2000). Briefly, hearts were removed from anaesthetized (5% halothane–95% O2) animals, mounted on a Langendorf apparatus and perfused retrogradely through the aorta with 40 ml of a (0.8 mg ml−1) collagenase-containing solution (Xu et al. 1999a, b; Guo et al. 1999). Following the perfusion, the right (RV) and left (LV) ventricles and the interventricular septum were separated using a fine scalpel and iridectomy scissors. The top and bottom ∼2 mm of the LV were separated to allow isolation of cells from the base and apex, respectively. The resulting tissue pieces were briefly (5 min) incubated in fresh collagenase-containing solutions and dispersed by gentle trituration. Following low-speed centrifugation, myocytes were resuspended in serum free medium 199 (Irvine), plated on laminin-coated coverslips and maintained in a 95% air−5% CO2 incubator until electrophysiological recordings were obtained (within 24 h of plating).

In some experiments, the LV free wall was further dissected. A small incision was first made from the epicardial (Epi) side, and layers of LV Epi cells were peeled away with fine forceps. The resulting tissue pieces were mechanically dispersed and plated as described above. This procedure was repeated on the endocardial (Endo) surface, and layers of LV Endo cells were removed, dissociated and plated. With a thickness of ∼1–1.5 mm and myocyte diameters of ∼20 μm, the adult mouse LV wall contains ∼50–75 layers of cells. For these experiments, ∼10–15 cell layers were removed to represent the Endo and Epi surfaces only; no attempt was made to further examine/compare cells through the thickness of the LV wall.

Initial experiments, focused on examining regional differences in repolarizing Kv currents, were completed on RV and LV cells from female animals; a total of 124 cells from 17 animals were studied. In experiments aimed at exploring the impact of sex on repolarizing K+ currents, RV, LV and septum cells were isolated from age-matched (8 week) adult male (n = 8) and female (n = 6) C57BL6 mice; a total of 203 cells from these 14 animals were studied. In addition, in some experiments, myocytes were obtained from the LV apex of hearts isolated from adult (10 week) male (n = 3) and female (n = 3) CD-1 mice (Charles River Laboratories); a total of 40 cells from these (6) animals were studied.

Electrophysiological recordings

Whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments were conducted within 24 h of cell isolation at room temperature (22–24°C). Previous studies have demonstrated no measurable differences in the time- or voltage-dependent properties of the K+ currents, in resting membrane potentials and/or in the waveforms of action potentials in adult mouse ventricular myocytes during the first ∼48 h in vitro (Xu et al. 1999a,b; Guo et al. 1999, 2000). Recording pipettes contained (in mmol l−1): KCl 135; EGTA 10; Hepes 10; and glucose 5 (pH 7.2; 310 mosmol l−1). The bath solution contained (in mmol l−1): NaCl 136; KCl 4; MgCl2 2; CaCl2 1; CoCl2 5; tetrodotoxin (TTX) 0.02; Hepes 10; and glucose 10 (pH 7.4; 300 mOsm). For current-clamp experiments, TTX and CoCl2 were omitted from the bath solution, and action potentials were recorded in response to brief (1 ms) depolarizing current injections delivered at 1 (or 3) Hz. All voltage- and current-clamp experiments were performed using an Axopatch 1D amplifier (Axon Instrument) interfaced to either a Gateway 600-MHz or a Dell Dimension 4100 Pentium 4 computer with a Digidata 1200/1332 analog/digital interface and the pCLAMP 8 software package (Axon Instrument). Data were filtered at 5 kHz before storage.

Series resistances were routinely compensated electronically (by ∼85%); voltage errors resulting from the uncompensated series resistance were always ≤ 9 mV and were not corrected. Voltage-gated K+ (Kv) currents were recorded in response to 4.5 s voltage steps to test potentials between −40 and +40 mV from a holding potential (HP) of −70 mV. Inwardly rectifying K+ currents (IK1) were recorded in response to 350 ms voltage steps to test potentials between −40 and −120 mV from the same HP.

Western blot analysis

Ventricular homogenates and membrane preparations were prepared from the RV, LV apex, LV base and interventricular septum of adult (8 week) C57BL6 male (n = 6) and female (n = 6) mice and from the RV and LV of adult (10 week) CD-1 male (n = 6) and female (n = 6) mice using previously described methods (Guo et al. 1999, 2000, 2002; Xu et al. 1999b; London et al. 2001). The protein content of each solubilized sample was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit with BSA as the standard. In initial experiments, different amounts (10–80 μg) of isolated ventricular proteins were fractionated on SDS-PAGE gels and immunoblotted with varying dilutions of the anti-Kv subunit-specific antibodies. The polyclonal and monoclonal anti-peptide antibodies targeted against Kv4.2, Kv4.3, Kv2.1 and KChIP2 have been previously described (Guo et al. 1999, 2002; An et al. 2000). The polyclonal anti-Kv1.5 antibody was generated against the sequence (C)EQGTQSQGPGLDRGVQR (amino acids 537–553) in the C-terminus of human Kv1.5, and affinity purified using a SulfoLink Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) (Fedida et al. 2003). The anti-Kvβ1.2 antibody (Nakahira et al. 1996) used was obtained from Dr James Trimmer at UC Davis. In addition, a monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody was purchase from Sigma and used (at 1 μg) as an external/internal control. These experiments revealed the optimal protein (40 μg) and antibody (0.25–5 μg) concentrations for immunoblot analysis.

To examine the impact of region and sex on Kv subunit expression levels, equal amounts of proteins (40 μg) from adult male and female C57BL6 mouse RV, LV apex, LV base and septum were fractionated on 8, 12 or 15% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), and incubated in 0.2% I-Block (Tropix) in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (blocking buffer) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C with one of the anti-Kv channel subunit-specific antibodies (at 0.25–5 μg ml−1) or the monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody. In each experiment, after washing, membrane strips were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG (Tropix) diluted 1:5000 in blocking buffer, and bound antibodies were detected using CPSD, a chemiluminescent alkaline phosphate substrate (Tropix). The membranes probed with the anti-Kv subunit-specific antibodies were subsequently stripped (using 0.2 m NaOH) and re-probed with the monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody to ensure equal protein loading of different lanes and different gels. In addition, in some experiments, the membranes (after protein transfer) were incubated simultaneously with a mixture of one of the anti-Kv subunit specific antibodies and the anti-β-actin antibody (followed by the secondary antibodies, also applied as a mixture). This procedure eliminated the stripping and reprobing steps and allowed direct comparison of Kv subunit and β-actin expression from the same film.

In all experiments, films of the Western Blots were obtained at varying exposure times to ensure that films were neither under- nor over-exposed. Films were scanned into a Molecular Dynamics Densitometer using Image Quant (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and the densities of the individual Kv subunit (and β-actin) bands were quantified by summing the pixel values above background within a defined area surrounding each protein band. To compare the Kv subunit expression levels in different regions of adult male and female C57BL6 (or CD-1) mouse ventricles, these values were then expressed relative to the values for the male RV value measured from analysis of the same film (blot). Mean ± s.e.m. values from six independent determinations are presented in Figs 7 and 8 (C57BL6) or in the text (CD-1).

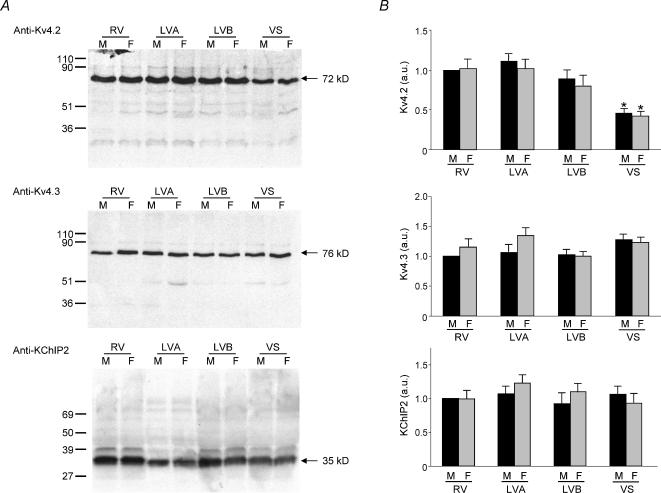

Figure 7. Expression of voltage-gated K+ channel subunits contributing to Ito,f in adult mouse ventricles.

A, ventricular homogenates were prepared from the RV, LV apex, LV base and septum of adult male and female mice, fractionated and immunoblotted with the anti-Kv4.2, anti-Kv4.3, or anti-KChIP2 antibody as described in Methods. Representative Western blots with-anti-Kv4.2 (top), anti-Kv4.3 (middle) and anti-KChIP2 (bottom) are presented in A. Films from individual experiments were scanned directly into a Molecular Dynamics densitometer using Image Quant. The density of the Kv4.2, Kv4.3 or KChIP2 bands in each lane were measured and normalized to the density of the male RV sample on the same blot. Mean ± s.e.m. values from six separate determinations are plotted in B. As reported previously (Guo et al. 2002), Kv4.2 expression is significantly (P < 0.001) lower in the interventricular septum than in the RV or LV and parallels the regional differences in Ito,f density. The expression levels of Kv4.2, Kv4.3 and KChIP2, however, are similar in adult male and female mouse right and left ventricles and in the interventricular septum.

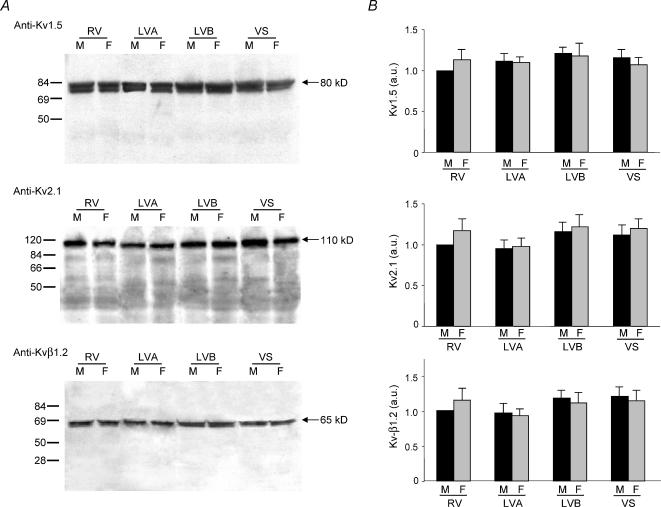

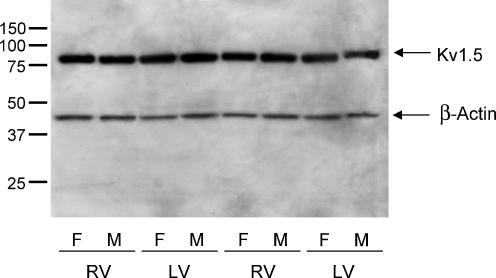

Figure 8. Expression of voltage-gated K+ channel subunits contributing to IK,slow in adult mouse ventricles.

A, ventricular homogenates were prepared from the RV, LV apex, LV base and septum of adult male and female mice, fractionated and immunoblotted with the anti-Kv1.5, anti-Kv2.1 or anti-Kvβ1.2 antibody as described in Methods. Representative Western blots with the anti-Kv1.5 (top), anti-Kv2.1 (middle) and anti-Kvβ1.2 (bottom) antibodies are presented in A. Films were scanned as described in the legend to Fig. 7, and the densities of the individual bands were normalized to the density of the male RV sample on the same film. Mean ± s.e.m. values from six separate determinations are plotted in B. The expression levels of Kv1.5, Kv2.1 and Kvβ1.2 are similar in adult male and female mouse RV, LV apex, LV base and interventricular septum.

Electrocardiograms

ECG recordings were obtained from adult (8 week) male (n = 14) and female (n = 12) C57BL6 mice and from adult (10 week) male (n = 11) and female (n = 11) CD-1 mice using Data Sciences International implantable Physiotel TA10ETA-F20 or TA10EA-F20 radio frequency transmitters and receivers, as previously described (Guo et al. 2000; Li et al. 2004). Briefly, after anaesthetizing an animal (intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg kg−1) and xylazine (16 mg kg−1)), the chest was opened, leads were tunnelled under the skin, sutured, and glued to muscles in the thorax. Cathodal leads were routinely placed on the upper right portion of the thorax, and anodal leads were placed on the chest wall near the apex. The transmitters were placed either in the abdominal cavity or on the back. After implantation of the transmitters, the animals were allowed to recover for at least 72 h. Four-minute recordings every hour for 48 consecutive hours were obtained from each animal; data were acquired at 1 kHz. Unfiltered data were analysed, and QT, QRS, PR, and RR intervals were measured; average values for individual animals were determined, and mean ± s.e.m. values for experiments completed on age-matched (8–10 week) male and female (C57BL6 and CD-1) mice are reported.

Data analysis

Voltage-clamp data were compiled and analysed using Clampfit (Axon Instruments) and Excel (Microsoft). Integration of the capacitative transients recorded during brief ± 10 mV voltage steps provided whole-cell membrane capacitances (Cm). Leak currents were always < 10 pA, and were not corrected. Peak currents were defined as the maximal outward K+ current; IK1 amplitudes were measured at the end of 350 ms voltage steps.

The time constants of inactivation (τdecay) and the amplitudes of Ito,f, Ito,s, IK,slow and Iss were determined from exponential fits to the decay phases of the outward K+ currents, as previously described (Xu et al. 1999a,b; Guo et al. 1999, 2000). In all experiments here therefore the total IK,slow amplitude/density in each cell was determined. Although previous studies have clearly documented the presence of two components of IK,slow, the Kv1.5-encoded IK,slow1 and the Kv2.1-encoded IK,slow2, the relative amplitudes of the currents cannot be determined reliably by kinetic analyses of the macroscopic currents because the inactivation time constants (of IK,slow1 and IK,slow2) only differ by approximately a factor of two (Xu et al. 1999a,b; London et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2003). In addition, although these currents display differential sensitivities to millimolar concentrations of TEA (IK,slow2) and micromolar concentrations of 4-aminopyridine (IK,slow1), these pharmacological tools do not allow the accurate determination of IK,slow1 and IK,slow2 amplitudes/densities in mouse ventricular myocytes primarily because other K+ currents (in addition to IK,slow1 and IK,slow2) are also affected (Xu et al. 1999a,b; London et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2003). Indeed, the definitive demonstration of the presence of IK,slow1 and IK,slow2 was only provided from molecular genetic studies in which the roles of Kv2.1 and Kv1.5 in the generation of these currents were clearly identified (Xu et al. 1999b; London et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2003). As a result, only the total IK,slow amplitude/density in each cell was determined and reported here.

Current amplitudes were normalized to whole-cell membrane capacitance, and current densities (in pA pF−1) are reported. Resting membrane potentials, action potential amplitudes and action potential durations at 50% (APD50) and 90% (APD90) were measured using Clampfit. All data are presented as means ± s.e.m. Differences between ventricular myocytes isolated from different regions of the ventricles and/or from male and female animals were assessed using ANOVA or Student's t test (when only two data sets are compared); P values are presented in the text.

For analysis of ECGs, the onsets and offsets of the P, Q, R, S and T waves were determined by measuring the earliest (onset) and the latest (offset) times from the two leads (London, 2001). Measured QT intervals were also corrected for differences in heart rate using the formula QTc = QTo/(RR/100)1/2, as previously described (Mitchell et al. 1998; Brunner et al. 2001).

Results

Peak outward Kv current densities are higher in RV than in LV myocytes

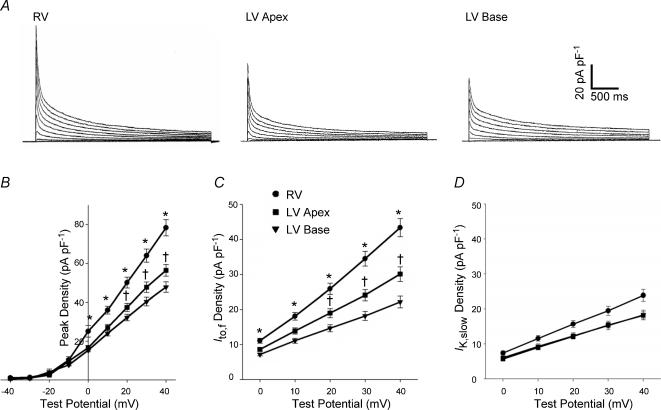

Representative outward K+ current waveforms recorded from adult (female) C57BL6 mouse RV, LV apex and LV base myocytes are presented in Fig. 1A. As is evident, peak outward K+ current densities are higher in RV than in LV apex or LV base myocytes (Fig. 1B). Mean ± s.e.m. peak outward K+ current densities at +40 mV, for example, were 78.4 ± 4.2 pA pF−1 (n = 26), 56.3 ± 3.0 pA pF−1 (n = 25) and 47.8 ± 2.7 pA pF−1 (n = 26) in (female) RV, LV apex and LV base cells, respectively (Table 1). As previously reported for LV apex cells (Xu et al. 1999a), the decay phases of the outward K+ currents evoked during long (4.5 s) depolarizations in RV myocytes are well described by the sum of two exponentials with mean ± s.e.m. (n = 26) inactivation time constants (τdecay) of 65 ± 2 and 1151 ± 33 ms (Table 1). These τdecay values are not significantly different from those determined for Ito,f (76 ± 4 ms) and IK,slow (1277 ± 35 ms) in LV apex (n = 25) cells (Table 1), suggesting that Ito,f and IK,slow are also expressed in mouse RV cells. Consistent with this suggestion, Ito,f is eliminated in RV myocytes from transgenic mice expressing a mutant Kv4 α-subunit (Kv4.2W362F) that functions as a dominant negative, Kv4.2 DN (Guo et al. 1999, 2000).

Figure 1. Peak outward K+ current and Ito,f densities are higher in adult mouse RV than in LV apex or base myocytes.

A, depolarization-activated outward K+ currents, evoked during 4.5 depolarizing voltage steps to potentials between −40 and +40 mV from a HP of −70 mV, were recorded and analysed as described in Methods. B, mean ± s.e.m. peak current densities are significantly (*P < 0.001) higher in RV (n = 26) than in either LV apex (n = 25) or LV base (n = 26) myocytes. In addition, mean ± s.e.m. peak current densities are significantly (+P < 0.05) higher in LV apex (n = 25) than in LV base (n = 26) cells. Analysis of the decay phases of the currents revealed that mean ± s.e.m. Ito,f density (C) is significantly (*P < 0.001) higher in RV (n = 26) than in LV apex (n = 25) or LV base (n = 26) myocytes, and that mean Ito,f density is higher (†P < 0.01) in LV apex than in LV base cells. IK,slow densities in RV, LV apex and LV base myocytes (D), in contrast, are not significantly different.

Table 1.

Regional differences in K+ currents in mouse ventricular myocytes

| Cells | Ipeak1 | Ito,f1 | IK,slow1 | ISS1 | IK12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RV | τdecay (ms) | 65 ± 2 | 1151 ± 33 | |||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 78.4 ± 4.2a | 43.4 ± 2.6a | 23.9 ± 1.7 | 7.2 ± 0.3 | −13.0 ± 0.7 | |

| n | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 22 | |

| LV wall | ||||||

| Apex | τdecay (ms) | 76 ± 4 | 1277 ± 35 | |||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 56.3 ± 3.0b | 30.1 ± 2.1c | 18.2 ± 1.0 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | −13.8 ± 0.7 | |

| n | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 23 | |

| Base | τdecay (ms) | 82 ± 4 | 1288 ± 43 | |||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 47.8 ± 2.7. | 22.2 ± 1.7 | 18.3 ± 1.4 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | −12.0 ± 0.7 | |

| n | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 24 | |

| Epi | τdecay (ms) | 89 ± 6 | 1191 ± 42 | |||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 58.9 ± 2.7d | 28.6 ± 1.7d | 22.1 ± 1.2d | 5.4 ± 0.2 | −9.7 ± 0.5 | |

| n | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Endo | τdecay (ms) | 95 ± 9 | 1441 ± 40e | |||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 37.3 ± 2.0 | 16.5 ± 1.1 | 15.1 ± 0.8 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | −11.0 ± 0.5 | |

| n | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 | 27 |

n = number of cells.

Current densities determined at +40 mV (HP = −70 mV).

Current densities determined at −120 mV (HP = − 70 mV).

Densities are significantly (P < 0.001) higher in RV than in LV cells.

Densities are significantly (P < 0.05) higher in LV apex than base cells.

Densities are significantly (P < 0.01) higher in LV apex than base cells.

Densities are significantly (P < 0.001) higher in LV Epi than Endo cells.

Values are significantly (P < 0.001) higher in LV Endo than Epi cells.

The decay phases of the outward K+ currents in LV base cells are also well described by the sum of two exponentials, with τdecay values that are not significantly different from those in LV apex or RV cells (Table 1), consistent with the expression of Ito,f and IK,slow. In addition, the time- and voltage-dependent properties of the currents in LV apex and LV base cells are indistinguishable. Similar to LV apex cells, and in contrast to septum cells (Xu et al. 1999a; Guo et al. 1999, 2000), there is no evidence for Ito,s expression in adult mouse RV or LV base myocytes. Also similar to LV apex cells, a steady-state, non-inactivating K+ current, Iss, is present in all RV and LV base myocytes (Fig. 1A, Table 1).

Further analysis revealed that Ito,f amplitudes and densities are significantly (P < 0.001) higher in RV than in LV apex (and base) myocytes (Fig. 1C). Mean ± s.e.m. Ito,f densities at +40 mV, for example, were 43.4 ± 2.6 pA pF−1 (n = 26), 30.1 ± 2.1 pA pF−1 (n = 25) and 22.2 ± 1.7 pA pF−1 (n = 26) in RV, LV apex and LV base cells, respectively (Table 1). The densities of IK,slow and Iss, as well as IK1, in RV and LV cells, in contrast, are not significantly different (Fig. 1D and Table 1). Within the LV, Ito,f densities are significantly (P < 0.01) higher in LV apex than in LV base myocytes (Fig. 1C; Table 1), whereas IK,slow (Fig. 1D) and Iss densities in LV apex and LV base cells are similar (Table 1). The marked differences in peak outward K+ current densities in RV, LV apex and LV base cells (Fig. 1, Table 1) therefore reflect the differential expression of Ito,f (see Discussion).

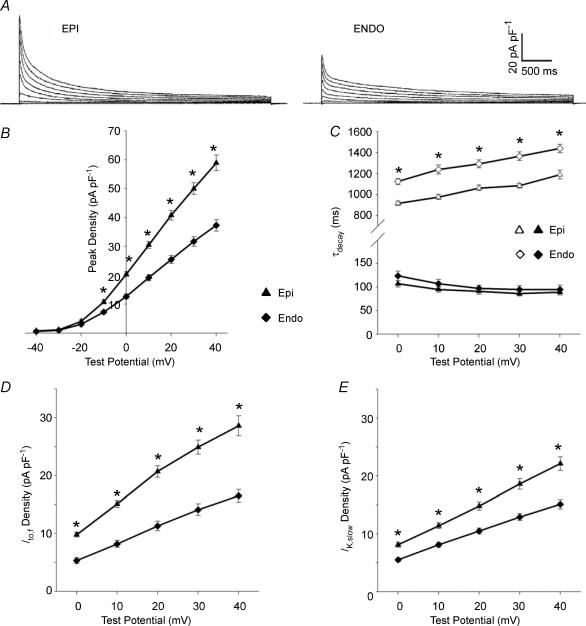

Heterogeneities in Kv currents in the LV wall

Subsequent experiments revealed that the waveforms of the outward K+ currents recorded from myocytes isolated from the epicardial (Epi) and endocardial (Endo) surfaces of the LV wall are similar (Fig. 2A), although peak outward K+ current amplitudes are substantially larger in LV Epi, compared with LV Endo, cells. There are no significant differences in mean ± s.e.m. whole cell membrane capacitances in LV Epi (149 ± 9 pF; n = 20) and LV Endo (137 ± 8 pF; n = 27) myocytes, and peak outward K+ current densities are significantly (P < 0.001) higher in LV Epi than in LV Endo cells (Fig. 2B). In both LV Epi and Endo cells, however, the decay phases of the outward currents were well fitted by the sum of two exponentials. The faster decay time constants are indistinguishable (Fig. 2C; Table 1), consistent with the expression of Ito,f in both mouse LV Endo and LV Epi cells. The mean ± s.e.m. τdecay value (1441 ± 40 ms) for IK,slow, in LV Endo cells, however, is significantly larger than the mean ± s.e.m. τdecay (1191 ± 42 ms) for IK,slow in LV Epi cells (Fig. 2C; Table 1).

Figure 2. Peak outward K+ current and Ito,f and IK,slow densities are higher in LV Epi than Endo myocytes.

A, outward K+ currents in LV Epi and Endo myocytes were recorded and analysed as described in the legend to Fig. 1. B, mean ± s.e.m. peak outward current densities are significantly (*P < 0.001) higher in LV Epi (n = 20) than LV Endo (n = 27), myocytes. C, the τdecay values for Ito,f (filled symbols) in LV Epi and Endo myocytes are indistinguishable, whereas the τdecay values for IK,slow (open symbols) are significantly (*P < 0.001) larger in LV Endo myocytes. Mean ± s.e.m. Ito,f (D) and IK,slow (E) densities are significantly (*P < 0.001) higher in LV Epi than LV Endo cells.

Consistent with the marked differences in peak outward K+ currents (Fig. 2A and B), the densities of Ito,f (Fig. 2D) and IK,slow (Fig. 2E) are significantly (P < 0.001) higher in LV Epi than in LV Endo myocytes. The mean ± s.e.m. (n = 20) Ito,f and IK,slow densities (at +40 mV) in LV Epi myocytes, for example, were 28.6 ± 1.7 and 22.1 ± 1.2 pA pF−1 (Table 1), whereas mean ± s.e.m. (n = 27) Ito,f and IK,slow densities (at +40 mV) in LV Endo myocytes were 16.5 ± 1.1 and 15.1 ± 0.8 pA pF−1 (Table 1). In contrast, mean ± s.e.m. Iss densities in LV Epi and Endo cells are not significantly different (Table 1).

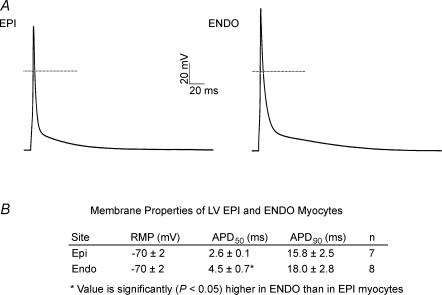

Similar to recently published findings (Anumonwo et al. 2001), current-clamp recordings revealed that action potential waveforms in adult mouse LV Epi and Endo myocytes are remarkably similar (Fig. 3A). Also similar to previous findings (Anumonwo et al. 2001), however, the mean ± s.e.m. APD50 is significantly (P < 0.05) longer in LV Endo (4.5 ± 0.7 ms; n = 8) than LV Epi (2.6 ± 0.1 ms; n = 7) myocytes, whereas mean ± s.e.m. APD90 values in LV Epi and LV Endo cells are not significantly different (Fig. 3B, see Discussion).

Figure 3. Action potential waveforms in adult mouse LV Endo and LV Epi myocytes are similar.

A, representative action potential waveforms recorded from LV Epi and LV Endo myocytes are displayed; the dotted lines indicate the 0 mV levels. B, summary of the resting and active membrane properties of LV Epi and Endo cells.

Impact of sex on Kv currents in adult mouse ventricles

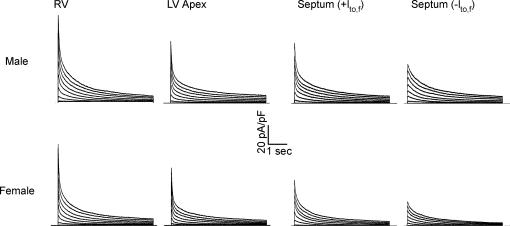

The marked differences in QT intervals and in arrhythmia susceptibility in males and females (Bidoggia et al. 2000; Surawicz, 2001) suggest sex-dependent differences in the expression of repolarizing, Kv currents (Drici et al. 1998; LeBlanc et al. 1998; Bidoggia et al. 2000; Surawicz, 2001). To test the hypothesis that there are sex differences in repolarizing Kv currents in mouse ventricular myocytes, depolarization-activated outward K+ currents were examined in cells isolated from the RV, LV apex and interventricular septum of adult male (n = 8) and female (n = 6) (C57BL6) mice. Consistent with the observations that the hearts are larger and that heart (and body) weights are higher in males, the mean ± s.e.m. Cm determined in female mouse ventricular myocytes (122 ± 3 pF; n = 77) is significantly (P < 0.001) lower than in male ventricular cells (147 ± 3 pF; n = 123).

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the waveforms of the depolarization-activated outward K+ currents in adult male and female (C57BL6) mouse RV and LV apex myocytes are very similar. Peak outward K+ current densities are, however, higher in septum cells isolated from male mice (Fig. 4; Table 2). Kinetic analyses of the outward K+ current waveforms revealed that mean ± s.e.m. Ito,f, IK,slow and Iss densities in adult male and female RV and LV apex cells are indistinguishable, whereas mean ± s.e.m. peak current, Ito,f, Ito,sIK,slow and Iss densities are significantly (P < 0.01) higher in septum cells from male than female animals (Table 2). The mean ± s.e.m. Ipeak densities (at +40 mV) determined in male (n = 39) and female (n = 21) septum cells with Ito,f, for example, were 54.2 ± 2.4 and 36.5 ± 2.6 pA pF−1 (Table 2), respectively.

Figure 4. Ventricular outward K+ current waveforms in cells from male and female mice are similar.

Representative outward K+ current waveforms, recorded as described in the legend to Fig. 1, in ventricular myocytes isolated from the RV, LV apex and septum of adult female and male (C57BL6) mice. Although no significant differences in outward K+ current densities or properties were seen in RV or LV myocytes from male and female mice, K+ current densities are higher in septum cells isolated from adult male (than female) mice (see text and Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of K+ currents in ventricular myocytes from male and female (C57BL6) mice

| Ipeak1 | Ito,f1 | Ito,s1 | IK,slow1 | ISS1 | IK12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | |||||||

| RV | τdecay (ms) | 79 ± 3 | — | 1230 ± 46 | |||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 83.5 ± 3.9a | 44.8 ± 2.4a | — | 27.4 ± 1.6 | 8.0 ± 0.3 | −14.0 ± 0.4 | |

| n | 44 | 44 | — | 44 | 44 | 35 | |

| LV apex | τdecay (ms) | 73 ± 2 | 1302 ± 48 | ||||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 63.8 ± 2.9b | 35.0 ± 1.8 b | — | 20.1 ± 1.2 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | −11.1 ± 0.4 | |

| n | 38 | 38 | — | 38 | 38 | 37 | |

| Septum | τdecay (ms) | 59 ± 2 | 410 ± 17 | 2092 ± 84 | |||

| (with Ito,f) | Density (pA pF−1) | 54.2 ± 2.4c | 17.0 ± 1.0c | 15.0 ± 1.2c | 17.0 ± 0.8c | 7.7 ± 0.2c | −10.9 ± 0.6 |

| n | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 35 | |

| Septum | τdecay (ms) | — | 153 ± 15 | 1668 ± 125 | |||

| (without Ito,f) | Density (pA pF−1) | 38.1 ± 4.0c | — | 9.8± 0.9c | 21.0 ± 2.8c | 7.4 ± 0.5c | −10.7 ± 1.5 |

| n | 7 | — | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| Female | |||||||

| RV | τdecay (ms) | 65 ± 2 | — | 1151 ± 33 | |||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 78.5 ± 4.2a | 43.4 ± 2.6a | — | 23.9 ± 1.7 | 7.2 ± 0.3 | −13.0 ± 0.7 | |

| n | 26 | 26 | — | 26 | 26 | 22 | |

| LV apex | τdecay (ms) | 76 ± 4 | — | 1277 ± 35 | |||

| Density (pA pF−1) | 56.3 ± 3.0b | 30.1 ± 2.1b | — | 18.2 ± 1.0b | 5.9 ± 0.2 | −13.8 ± 0.7 | |

| n | 25 | 25 | — | 25 | 25 | 23 | |

| Septum | τdecay (ms) | 56 ± 2 | 396 ± 21 | 2280 ± 163 | |||

| (with Ito,f) | Density (pA pF−1) | 36.5 ± 2.6 | 11.1 ± 1.4 | 9.3 ± 1.2 | 11.9 ± 0.8 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | −11.2 ± 0.6 |

| n | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 23 | |

| Septum | τdecay (ms) | — | 211 ± 37 | 1787 ± 135 | |||

| (without Ito,f) | Density (pA pF−1) | 21.4 ± 3.8 | — | 6.5 ± 2.4 | 11.9 ± 1.9 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | −11.0 ± 0.9 |

| n | 3 | — | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

n = number of cells.

Current densities determined at +40 mV (HP = −70 mV).

Current densities determined at −120 mV (HP = −70 mV).

Densities are significantly (P < 0.05) higher in RV than in LV cells.

Densities are significantly (P < 0.05) higher in LV apex than in septum cells.

Densities are significantly (P < 0.05) higher in male than female LV septum cells.

Similar differences in mean ± s.e.m. current densities were evident in septum cells lacking Ito,f (Table 2). Although there are large differences in current densities, the time- (Table 2) and voltage-dependent properties of Ito,f, Ito,s and IK,slow in adult male and female (C57BL6) mouse septum cells are indistinguishable. Also, in contrast to the outward K+ currents, and similar to the findings with male and female RV and LV cells, no significant differences in IK1 densities were detected in male and female (C57BL6) interventricular septum cells (Table 2).

The observed similarities in Kv currents in male and female (C57BL6) mouse ventricles (Fig. 4, Table 2) are at variance with the findings of Trépanier-Boulay et al. (2001) who reported that IKur (IK,slow1) density is lower in epicardial RV and LV myocytes isolated from adult female, compared with male, CD1 mice. To test the hypothesis that there might be strain differences in sex-dependent effects on Kv current expression, additional experiments were completed on LV apex myocytes isolated from adult male and female FVB, Sv129 and CD-1 animals. Similar to the results obtained in the detailed studies described above on C57BL6 myocytes, these analyses revealed no significant differences in peak outward Kv, Ito,f, IK,slow or Iss densities and/or in the properties of these currents in LV apex cells from male and female FVB or Sv129 animals, both of which, like C57BL6, are inbred strains.

Similar to the previously reported findings (Trépanier-Boulay et al. 2001), however, significant (P < 0.01) differences in peak outward Kv current densities were evident in LV cells isolated from adult male, compared with female, CD-1 mice. The mean ± s.e.m. peak outward K+ current densities (at +40 mV), for example, were 57.1 ± 4.8 pA pF−1 (n = 20) and 42.5 ± 3.1 pA pF−1 (n = 20) in LV cells from adult CD-1 male (n = 3) and female (n = 3) mice, respectively. Analysis of the Kv current waveforms in these cells further revealed that mean ± s.e.m. IK,slow density is significantly (P < 0.02) higher in adult male (22.0 ± 1.8 pA pF−1; n = 20) than in adult female (15.8 ± 1.4 pA pF−1; n = 20), CD-1 LV myocytes. Mean ± s.e.m. Ito,f and Iss densities in LV myocytes from adult male and female CD-1 animals, however, are not significantly different. These results are consistent with the findings reported previously by Trépanier-Boulay et al. (2001) and demonstrate small, albeit statistically significant, differences in IK,slow 1 (IKur) densities in the ventricles of male and female CD-1 mice.

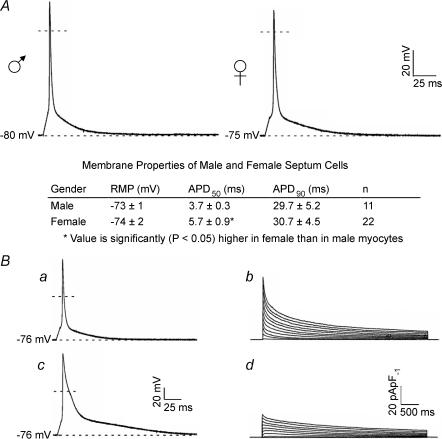

Impact of sex on action potential repolarization in adult mouse ventricles

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the waveforms of action potentials recorded from adult male and female (C57BL6) interventricular septum cells are quite similar. There is a small, but statistically significant (P < 0.05), difference in mean ± s.e.m. APD50 values, whereas mean ± s.e.m. APD90 values in adult male and female septum cells are not significantly different (Fig. 5A). Thus, in spite of the differences in outward K+ currents, action potential amplitudes and durations are similar in adult male and female C57BL6 interventricular septum cells (Fig. 5A). Nevertheless, action potential durations in individual (male and female) septum cells are variable, probably owing to the (cellular) heterogeneity in outward K+ current waveforms and densities. Consistent with this hypothesis, combined current- and voltage-clamp recordings revealed that action potential durations in individual septum cells are directly correlated with outward K+ current densities and the expression of Ito,f (Fig. 5B). Action potential durations are longer (Fig. 5Bc), for example, in septum cells with low peak outward K+ current densities and lacking Ito,f (Fig. 5Bd) than in septum cells (Fig. 5Ba) with higher peak K+ current densities and expressing Ito,f (Fig. 5Bb). Linear regression analysis revealed that APD50 and APD90 values in individual cells are highly (P < 0.02 and P < 0.01, respectively) correlated with the density of Ito,f.

Figure 5. Action potential durations in septum cells are correlated with differences in voltage-gated outward K+ current densities.

A, representative action potential waveforms recorded from adult mouse septum cells; the dashed lines indicate the 0 mV levels. A summary of the resting and active membrane properties of adult male and female septum cells is provided below the records. B, action potential durations in septum cells vary with peak outward K+ current densities. Action potentials and depolarization-activated outward K+ currents were recorded from isolated (adult female) septum cells as described in the legends to Figs 3 and 1, respectively; the voltage- and current-clamp recordings in a and b, and c and d were obtained from the same cell. Similar results were obtained in experiments on seven cells.

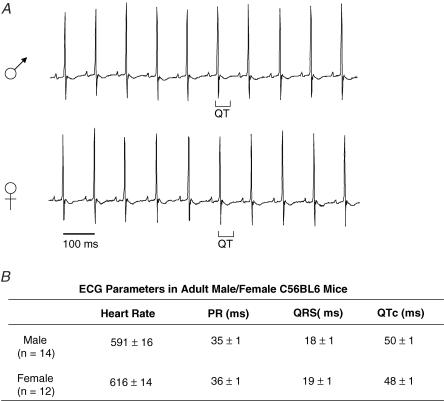

Consistent with the similarities in ventricular K+ currents and action potential waveforms, telemetric ECG recordings from (freely moving, unanaesthetized) adult male and female (C57BL6) mice are indistinguishable (Fig. 6). In addition, analyses of telemetric ECG recordings revealed no significant differences in any ECG parameters between adult male (n = 14) and female (n = 12) (C57BL6) mice (Table 3). Mean ± s.e.m. heart rates, for example, were 591 ± 16 and 616 ± 14 bpm, and mean ± s.e.m. QTc intervals were 50 ± 1 and 48 ± 1 ms, in adult male (n = 14) and female (n = 12) (C57BL6) mice, respectively. Similarly, no significant differences in mean ± s.e.m. PR intervals (35 ± 1 and 36 ± 1 ms) or in mean ± s.e.m. QRS durations (18 ± 1 and 19 ± 1 ms) were evident in recordings from adult female and male (C57BL6) mice (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. QTc intervals in adult (C57BL6) male and female animals are indistinguishable.

Telemetric ECG recordings were obtained from adult male and female C57BL6 animals as described in Methods. A, telemetric ECG recordings from representative male and female animals are displayed; QT intervals are indicated below the records. B, analyses of ECG recordings revealed no significant differences in any ECG parameters in adult male (n = 14) and female (n = 12) C57BL6 mice. Mean ± s.e.m. heart rate, PR QRS and QTc intervals are indistinguishable in male and female C57BL6 animals.

It has previously been reported that corrected (but not uncorrected) QT, i.e. QTc, intervals are longer in adult female than in adult male CD-1 mice (Brouillette et al. 2003). To determine if the disparity between these findings and the results obtained here in C57BL6 mice reflect strain differences and/or the fact that the recordings were obtained under different experimental conditions, telemetric ECG recordings were also obtained from unanaesthetized adult male and female CD-1 mice. Analyses of the data obtained in these experiments revealed no significant differences in QT intervals or heart rates and therefore no differences in QTc intervals, in (unanaesthetized) adult male and female CD-1 mice. Mean ± s.e.m. QTc intervals determined in male and female CD-1 mice, for example, were 47 ± 1 ms (n = 11) and 46 ± 1 ms (n = 11), respectively. These observations suggest that the pentobarbitone anaesthesia used in the previous study (Brouillette et al. 2003) probably contributes to the observed differences in QTc intervals in male and female CD-1 animals (see Discussion).

Expression of Kv channel subunits in adult mouse ventricles

Subsequent experiments were focused on examining regional differences in the expression of the Kv subunits, shown previously to play a role in the generation of Ito,f and IK,slow, in adult (C57BL6) male (n = 6) and female (n = 6) ventricles. Exploiting a combination of molecular genetic and biochemical approaches, previous studies have revealed that mouse ventricular Ito,f channels reflect the heteromeric assembly of Kv4.2, Kv4.3 and KChIP2 (Barry et al. 1998; Guo et al. 2000, 2002; Kuo et al. 2001). In addition, several previous studies have demonstrated that there are two distinct components of mouse ventricular IK,slow: IK,slow1, encoded by Kv1.5 (London et al. 1998, 2001; Brunner et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2003; Li et al. 2004) and IK,slow2, encoded by Kv2.1 (Xu et al. 1999b; Zhou et al. 2003). The molecular identity of Iss has not been determined to date. To examine and compare Kv subunit expression levels, Western blots were performed in fractionated proteins from adult male and female ventricles using anti-Kv subunit-specific antibodies. Immunoblots were also performed with an antibody targeted against the accessory Kvβ subunit, Kvβ1.2, which is expressed in the mammalian heart and is has been hypothesized that this plays a role in the formation of functional voltage-gated cardiac K+ channels (Nerbonne & Kass, 2003).

To allow comparison of the expression levels of each of the Kv subunits in different regions of the ventricles (and septum) and in samples prepared from male and female animals, equal amounts of proteins (prepared as described in Methods) were loaded onto the same gel for blotting. Parallel gels were run and probed with each of the anti-Kv subunit-specific antibodies, as well as an anti-β-actin antibody, to ensure equal loading of proteins in different gels and to facilitate comparisons among samples. In addition, the membranes that were probed with each of the anti-Kv subunit-specific antibodies were stripped and reprobed with the anti-β-actin antibody to allow direct assessment of the loading of each lane and to enable comparison and normalization of the Kv subunit protein bands in each sample following quantification of the films by densitometry. In some experiments, membranes were incubated simultaneously with a mixture of one of the anti-Kv subunit-specific antibodies and the anti-β-actin antibody (followed by the secondary antibodies, also applied as a mixture). This procedure eliminated the stripping and reprobing steps and allowed direct comparison of Kv subunit and β-actin expression from the same film. To facilitate comparisons between different samples, the intensities of the each of the labelled (Kv subunit) bands on each of the blots were normalized to the density of the protein band detected in the male right ventricular (RV) sample on the same blot. The mean ± s.e.m. relative densities of the protein bands corresponding to Kv4.2, Kv4.3, KChIP2, Kv1.5, Kv2.1 and Kvβ1.2 in adult male and female C57BL6 mouse RV, LV apex, LV base and interventricular septum samples were then determined.

Typical results obtained using the antibodies targeted against Kv4.2, Kv4.3 and KChIP2 are presented in Fig. 7A, and cmulative mean ± s.e.m. normalized data for these three Kv subunits are presented in Fig. 7B. The intensities of the bands detected with the anti-Kv4.3 antibody is similar in (male and female) RV, LV apex, LV base and septum, whereas Kv4.2 protein expression is higher in RV, LV apex and LV base than in septum (Fig. 7A and B). The lower expression levels of Kv4.2 in (both male and female) septum compared with RV and LV parallels the marked differences in Ito,f densities in septum compared with RV and LV myocytes (Fig. 4, Table 2). Although there are also statistically significant (P < 0.001) differences in Ito,f densities in RV, LV apex and LV base myocytes (Fig. 1, Table 2), there are no significant differences in Kv4.2 expression levels in Western blots of membrane proteins from these regions (Fig. 7B).

These observations may reflect the fact that differences in Kv4.2 expression in these regions are too small to detect reliably or, alternatively, that something other than (or in addition to) Kv4.2 determines the gradient in Ito,f expression in the (right and left) ventricles. Similar to previously published findings for LV apex and septum (Guo et al. 2002), the experiments here revealed no measurable regional variations in the relative expression levels of the Kv4 channel accessory subunit, KChIP2, in the RV, LV apex, LV base or septum of either adult male or female (C57BL6) mice (Fig. 7A and B).

Western blot analyses were also completed to examine the expression levels of Kv1.5 and Kv2.1, the two Kvα subunits shown previously to encode the two components of mouse ventricular IK,slow, IK,slow1 (Kv1.5) and IK,slow2 (Kv2.1) (London et al. 1998, 2001; Zhou et al. 1998, 2003; Xu et al. 1999b). These experiments revealed no significant regional differences in Kv1.5 or Kv2.1 expression in adult (C57BL6) mouse RV, LV apex, LV base and septum (Fig. 8). There were also no measurable regional differences in the expression levels of the Kvβ1.2 accessory subunit (Fig. 8). Finally, and similar to the findings with Kv4.2, Kv4.3 and KChIP2 (Fig. 7), the expression levels of Kv1.5, Kv2.1 and Kvβ1.2 are similar in adult male and female C57BL6 mouse RV, LV apex, LV base and septum (Fig. 8).

The similarity in Kv1.5 expression in adult male and female C57BL6 mouse ventricles (Fig. 8) is at variance with a previous report that Kv1.5 expression is lower in the RV and LV of adult female, compared with male, CD-1 mice (Trépanier-Boulay et al. 2001). Further Western blot experiments were completed therefore to examine Kv subunit expression patterns in adult male and female CD-1 mouse ventricles. Representative Western blot data for Kv1.5 and β-actin expression in the RV and LV of two adult male and two adult female CD-1 mice are presented in Fig. 9. As is evident, no differences in Kv1.5 protein expression were detected; similar results were obtained in Western blots completed on RV and LV samples from six adult male and six adult female CD-1 mice. There were also no measurable differences detected in the expression levels of Kv4.2, Kv4.3, KChIP2, Kv2.1 or Kvβ1.2 in adult male and female CD-1 LV or RV (not illustrated).

Figure 9. Expression of Kv1.5, which encodes IK,slow1, in adult male and female CD-1 mouse ventricles.

Ventricular homogenates were prepared from the RV and LV of adult male (n = 6) and female (n = 6) CD-1 mice, fractionated and immunoblotted with the anti-Kv1.5 and anti-β-actin antibodies as described in Methods. Representative data from two male and two female RV and LV are presented. Films were scanned as described in the legend to Fig. 7, and no significant differences in Kv1.5 expression were evident in the RV or LV samples from the male and the female CD-1 animals (see text).

Discussion

Regional differences in repolarizing Kv current expression in adult mouse ventricles

The experiments described here revealed marked differences in peak outward Kv current densities in cells isolated from different regions of adult (C57BL6) mouse ventricles. The C57BL6 strain was selected for the detailed analysis reported here primarily because it is one of the commonly used (inbred) mouse strains exploited in studies aimed at generating/characterizing transgenic animals and in the analysis of the functional impact of gene targeting approaches. Qualitatively similar results were also obtained in (inbred) FVB and Sv129 strains (data not shown), which are also commonly used strains in the generation of transgenic and gene targeted animals. Peak outward Kv current densities are highest in RV, followed by LV apex and LV base, myocytes and are lowest in cells in the interventricular septum. Kinetic analysis of the outward K+ current waveforms revealed that the primary determinant of the differences in peak outward Kv currents is the differential expression of Ito,f. Mean ± s.e.m. Ito,f densities, for example, are significantly higher in RV than in LV myocytes and mean ± s.e.m. Ito,f densities are also higher in LV apex than LV base myocytes. In contrast, the densities of IK,slow and Iss in RV, LV apex and LV base cells are not significantly different. The biochemical studies revealed that the primary determinant of the difference in Ito,f densities is the differential expression of Kv4.2. No regional differences in the expression of Kv4.3 or of the Kv4 accessory subunit, KChIP2, which have been shown previously to contribute to the generation of (heteromeric) Ito,f channels (Guo et al. 2002; Kuo et al. 2001), were detected.

Within the LV wall, however, both Ito,f and IK,slow are expressed at higher densities in LV Epi than LV Endo cells (Table 1). In addition, the time constant for IK,slow decay is significantly larger in LV Endo than LV Epi cells, suggesting differences in the functional cell surface expression of the two IK,slow components, IK,slow1, encoded by Kv1.5 (London et al. 1998, 2001) and IK,slow2, encoded by Kv2.1 (Xu et al. 1999b; Zhou et al. 2003). The biochemical studies here, however, did not reveal measurable regional differences in Kv1.5 or Kv2.1 expression, suggesting either that regional differences in (Kv1.5/Kv2.1) protein expression are too small to detect reliably or, alternatively, that additional subunits are involved in the generation of IK,slow1 and IK,slow2 channels and/or that post-translational processing of Kv2.1/Kv1.5 α subunits plays a role in determining the functional cell surface expression of IK,slow1 and IK,slow2 channels. Consistent with the differences in Ito,f and IK,slow densities and with previously published findings (Anumonwo et al. 2001), current-clamp recordings revealed that APD50 values are longer in LV Endo than in LV Epi myocytes, although, interestingly, APD90 values in LV Epi and LV Endo myocytes are indistinguishable.

In all RV, LV base, LV Epi and LV Endo cells, the decay phases of the outward K+ currents are well described by the sum of two exponentials with mean ± s.e.m. τdecay values (Table 1) that are similar to those previously reported for Ito,f and IK,slow in LV apex cells (Xu et al. 1999b). In contrast to septum cells therefore Ito,f is evident in all RV, LV apex, LV base, LV Epi and LV Endo myocytes. In addition, there were no RV, LV apex, LV base, LV Epi or LV Endo cells in which two exponentials provided a poor fit to the experimental data. The simplest interpretation of these combined observations is that only Ito,f, IK,slow and Iss are expressed in RV, LV apex, LV base, LV Epi and LV Endo cells, and that Ito,s is not expressed in (wild-type) adult mouse ventricles, except in cells in the interventricular septum. It has been demonstrated, however, that Ito,s is up-regulated in (non-septum) mouse ventricular cells isolated from animals expressing a dominant negative Kv4.2α subunit, Kv4.2 DN, which lack Ito,f (Barry et al. 1998; Guo et al. 2000). Although the underlying mechanism involved in mediating the up-regulation of Ito,s in non-septum cells in Kv4.2 DN animals remains to be determined, these observations do demonstrate that mouse ventricular myocytes (in addition to septum cells) have the capacity to produce functional (cell surface) Ito,s channels when Ito,f is eliminated.

Sex differences in repolarizing Kv currents and Kv subunit expression

The results presented here also revealed that Kv current densities and properties in adult male and female (C57BL6) mouse RV and LV cells are indistinguishable, although there are statistically significant differences in Kv current densities in male versus female septum cells (Table 2). There is also a statistically significant difference in mean ± s.e.m. APD50 in male and female septum cells, whereas APD90 values are indistinguishable. Considerable heterogeneity in Kv current densities and waveforms is evident among septum cells, however, with ∼80% of the cells expressing Ito,f and Ito,s, and ∼20% of the cells expressing only Ito,s. Combined current-clamp–voltage-clamp experiments suggest that the major factor determining differences in action potential durations among septum cells is the heterogeneous expression of Ito,f (Fig. 5B). The differences in Kv current densities in individual septum cells are reflected directly in the durations of evoked action potentials, i.e. action potentials are briefer in cells with higher peak outward Kv current densities and expressing Ito,f.

In spite of the differences in Kv current densities and mean (± s.e.m.) APD50 in septum cells isolated from male and female C57BL6 animals, there are no statistically significant differences in ECG parameters, including QTc intervals, evident in telemetric recordings from adult male and female (C57BL6) mice. In addition, there are no significant differences in the relative expression levels of Kv4.2, Kv4.3, Kv1.5, Kv2.1, KChIP2 or Kvβ1.2 in male and female (C57BL6) mouse interventricular septum. These observations suggest that the differences in functional Kv current densities in the septum of male versus female C57BL6 mice must reflect a process or processes other than the regulation of the membrane expression of the known Kv subunits encoding the underlying Kv channels Ito,f, Ito,s, IK,slow and Iss. It seems likely that differences in the expression of yet to be identified accessory subunits and/or other regulatory proteins, or possibly differences in post-translational processing, may be involved. Importantly, the absence of any clear functional context precludes completing further studies focused on exploring the underlying molecular mechanisms until the molecular identities of the underlying regulatory element or elements have been identified. In addition, although it might be suggested that these observations belie the functional importance of the observed differences in Kv current densities in male versus female (C57BL6) mouse septum, it is certainly possible that regional differences in outward currents in other species contribute to sex-dependent differences in QTc intervals and arrhythmia susceptibility (Drici et al. 1998; Liu et al. 1998; Bidoggia et al. 2000; Lu et al. 2001; Surawicz, 2001). Experiments in large mammals focused on examining directly the impact of sex on the expression of ventricular Kv currents and on exploring the role of these currents in determining sex-dependent differences in QTc intervals, the dispersion of ventricular repolarization, and the susceptibility to drug-induced arrhythmias will clearly be necessary to test this hypothesis directly.

The absence of marked sex differences in Kv currents in C57BL6 mouse ventricular cells appears to be in conflict with a recent paper from Wu & Anderson (2002) reporting reduced repolarization reserve in female mouse (C57BL6/Sv129) ventricles, an effect attributed to lower Ito density in female, as compared with male, mouse (C57BL6/Sv129) ventricular myocytes. Also, in contrast to the findings presented here for C57BL6 ventricular myocytes, Wu & Anderson (2002) reported that the densities of the non-inactivating outward K+ currents, Isus (which probably actually reflects the sum of IK,slow and Iss) are higher in female (compared with male) ventricular cells. Interestingly, these results are opposite to those of Trépanier-Boulay et al. (2001) who reported lower (not higher) IKur (IK,slow1) densities in cells from female (CD-1) animals. Given the marked regional heterogeneity in peak outward ventricular K+ current and Ito,f densities detailed in the present study, however, it is clear that tissue sampling and cell numbers are crucial for quantitative determinations of Kv current expression in mouse myocardium.

The similarities in Kv currents and Kv subunit expression patterns in male and female (C57BL6) mouse ventricles demonstrated here are also at variance with the findings of Trépanier-Boulay et al. (2001) who reported that IKur (IK,slow1) density and Kv1.5 expression is lower in epicardial (RV and LV) myocytes isolated from adult female, compared with male (CD-1) mice. The Western blot analysis completed here, however, failed to reveal any significant differences in Kv1.5 protein expression in adult male and female CD-1 ventricles. Nevertheless, the electrophysiological studies completed here confirm the previous findings (Trépanier-Boulay et al. 2001) and demonstrate small, albeit statistically significant, differences in peak Kv currents, attributed to differences in IK,slow1 densities in the ventricles of male and female CD-1 mice. Similar to our findings in the septum of adult male and female C57BL6 mice discussed above, the fact that IKslow1 densities are different, whereas Kv1.5 expression levels appear indistinguishable in adult male and female CD-1 mouse ventricles suggests that differences in the expression of yet to be identified accessory subunits and/or other regulatory proteins contributing to the formation of Kv1.5-encoded IK,slow1 channels, or that differences in post-translational processing of these subunits/proteins, are likely to be important in determining functional IK,slow1 densities. Once the molecular mechanisms controlling the functional cell surface expression of IK,slow1 (and other cardiac ion) channels are delineated, it will be of interest to explore the impact of sex and the effects of steroid hormones on these pathways.

Taken together, the experiments described here reveal that sex has no impact on the expression and the functioning of ventricular Kv currents in several inbred strains (C57BL6, FVB, Sv129) of mice typically used in the generation of genetically altered animals, and that if one wants to explore hormonal (i.e. sex-dependent) regulation of Kv currents (and perhaps other currents as well), these experiments should probably be done on the outbred CD-1 strain. Clearly, however, the use of outbred strains compromises the power and potential of using mice for functional cardiovascular (and other) investigations and is almost certainly the reason that these strains are not typically used in molecular genetic studies.

Sex differences in electrocardiographic parameters

Telemetric ECG recordings revealed no statistically significant differences in any ECG parameters in unanaesthetized adult male and female C57BL6 mice. Similar results were obtained in the studies completed on adult male and female CD-1 animals. It has previously been reported, however, that corrected QT (QTc) intervals are longer in anaesthetized (pentobarbital) adult female, compared with male, CD-1 mice (Brouillette et al. 2003). The absence of any measurable differences in QT intervals, heart rates or QTc intervals in unanaesthetized adult male and female CD-1 mice in the studies here suggest that the pentobarbital anaesthesia used in the previous study probably contributes to the observed differences in QTc intervals in male and female CD-1 animals (Brouillette et al. 2003). In addition, because only QTc (and not QT) intervals were affected, it appears that these observations reflect sex-dependent differences in the effects of the (pentobarbital) anaesthesia on the heart rates of adult male and female CD-1 mice, rather than differences in ventricular repolarization.

Previous ECG studies on isolated adult male and female OF1 mice have also failed to detect any statistically significant differences in baseline electrophysiological properties (Drici et al. 2002). Halothane-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, however, is observed more frequently and, when observed, lasts significantly longer in adult female, compared with male, OF1 hearts (Drici et al. 2002). These observations again suggest that sex affects anaesthesia sensitivity and arrhythmia susceptibility, although no differences in ventricular repolarization in male and female OF1 mice were observed (Drici et al. 2002). Interestingly, a recently published, rather comprehensive study of ECG parameters and arrhythmia susceptibility in mice revealed marked strain- but not sex-dependent differences in QTc intervals, effective refractory periods and arrhythmia vulnerability (Maguire et al. 2003). Only inbred (including Sv129, C57BL6, FVB and Black Swiss) strains (and hybrids of these) were included in these studies (Maguire et al. 2003). No outbred strains were examined, probably because inbred strains are preferred for electrophysiological and molecular genetic studies.

Implications of heterogeneities in mouse ventricular Kv currents

The marked regional differences in the densities of the repolarizing Kv currents, Ito,f and Ito,s, in adult mouse ventricles are reflected in differences in action potential waveforms and will contribute therefore to the normal dispersion of repolarization and the propagation of excitation. Experimental manipulations that alter the densities and/or the functional properties of these currents are expected to have an impact on the repolarization gradients in the heart and the normal spread of activity. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been demonstrated that manipulations which increase the dispersion of ventricular repolarization in the mouse are pro-arrhythmic (London et al. 1998; Baker et al. 2000; Kodirov et al. 2004), whereas those that reduce the dispersion of repolarization are anti-arrhythmic (Barry et al. 1998; Guo et al. 2000; Brunner et al. 2001). It seems reasonable to suggest therefore that the regional differences in the expression of Ito,f and Ito,s should be considered when conducting (and interpreting) in vivo or in vitro electrophysiological experiments on the intact mouse heart. In addition, the observed differences in Kv current densities in adult male and female septum cells could have an impact on the dispersion of repolarization in the intact (male and female) heart and affect propagation. Taken together with previous findings (Drici et al. 2002; Brouillette et al. 2003), the results presented here suggest that sex should be considered a variable in electrophysiological studies in the mouse, particularly in studies involving ECG monitoring and analyses of spontaneous or induced arrhythmias in anaesthetized animals.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (HL-34161 and HL-66388 to J.M.N. and HL-66350 to K.A.Y.), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant to D.F.), the American Heart Association (Postdoctoral Fellowship to F.A.), the McDonnell Center for Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology (Postdoctoral Fellowship to W.G.). In addition, we thank Dr Haodong Xu for many helpful discussions and Rick Wilson for expert technical assistance.

References

- An WF, Bowlby MR, Betty M, Cao J, Li H-P, Mendoza G, Hinson JW, Mattsson KI, Strassle BW, Trimmer JS, Rhodes KJ. Modulation of A-type potassium channels by a family of calcium sensors. Nature. 2000;403:553–556. doi: 10.1038/35000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Dumaine R. Electrical heterogeneity in the heart: Physiological, pharmacological, and clinical implications. In: Page E, Fozzard HA, Solaro RJ, editors. The Handbook of Physiology, section 2, The Cardiovascular System, The Heart. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. pp. 654–692. [Google Scholar]

- Anumonwo J, Tallini YN, Vetter FJ, Jalife J. Action potential characteristics and arrhythmogenic properties of the cardiac conduction system of the murine heart. Circ Res. 2001;89:329–335. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.095894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LC, London B, Choi BR, Koren G, Salama G. Enhanced dispersion of repolarization and refractoriness in transgenic mouse hearts promotes reentrant ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2000;86:396–407. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Xu H, Schuessler RB, Nerbonne JM. Functional knockout of the transient outward current, long–QT syndrome, and cardiac remodeling in mice expressing a dominant- negative Kv4 alpha subunit. Circ Res. 1998;83:560–567. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidoggia H, Maciel JP, Capalozza N, Mosca S, Blaksley EJ, Valverde E, Betran G, Arini P, Biagetti MO, Quinteiro RA. Sex-dependent electrocardiographic pattern of cardiac repolarization. Am Heart J. 2000;140:430–436. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.108510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillette J, Trépanier-Boulay V, Fiset C. Effect of androgen deficiency on mouse ventricular repolarization. J Physiol. 2003;546:403–413. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner M, Guo W, Mitchell GF, Buckett PD, Nerbonne JM, Koren G. Characterization of mice with a combined suppression of Ito and IK,slow. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:H1201–H1209. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drici MD, Baker L, Plan P, Barhanin J, Romey G, Salama G. Mice display sex differences in halothane-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2002;106:497–503. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023629.72479.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drici MD, Burklow TR, Haridasse V, Glazer RI, Woosley RL. Sex hormones prolong the QT interval and downregulate potassium channel expression in the rabbit heart. Circulation. 1998;94:1471–1474. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.6.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedida D, Eldstrom J, Hesketh C, Lamorgese M, Castel L, Steele DF, Van Wagoner DR. Kv1.5 is an important component of repolarizing K+ current in canine atrial myocytes. Circ Res. 2003;93:744–751. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000096362.60730.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiset C, Clark RB, Larsen TS, Giles WR. A rapidly activating, sustained K+ current modulates repolarization and excitation-contraction coupling in adult mouse ventricles. J Physiol. 1998;504:557–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.557bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu GS, Meissner A, Simon R. Repolarization dispersion and sudden cardiac death in patients with impaired left ventricular function. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:281–289. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Li H, Aimond F, Johns DC, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS, Nerbonne JM. Role of heteromultimers in the generation of cardiac transient outward currents. Circ Res. 2002;90:586–593. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012664.05949.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Li H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Functional consequences of elimination of Ito,f and Ito,s: early afterdepolarizations, atrioventricular block, and ventricular arrhythmias in mice lacking Kv1.4 and expressing a dominant-negative Kv4 α subunit. Circ Res. 2000;87:73–79. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Xu H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of transient outward K+ current diversity in mouse ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1999;521:587–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodirov S, Brunner M, Busconi L, Nerbonne JM, Buckett P, Mitchell G, Koren G. Attenuation of IK,slow1 and IK,slow2 in Kv1DN mice prolongs the APD and QT intervals but does not prevent spontaneous or inducible arrhythmias. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:H368–H374. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00303.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HC, Cheng CF, Clark RB, Lin JT, Lin JL, Hoshijima M, Nguyen-Tran VT, Gu Y, Ikeda Y, Chu PH, Ross J, Giles WR, Chien KR. A defect in the Kv channel-interacting protein 2 (KChip2) gene leads to a complete loss of I(to) and confers susceptibility to ventricular tachycardia. Cell. 2001;107:801–813. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc N, Chartier D, Gosselin H, Rouleau J-L. Age and gender differences in excitation-contraction coupling of the rat ventricle. J Physiol. 1998;511:533–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.533bh.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Guo W, Yamada KA, Nerbonne JM. Selective elimination of IK,slow1 in mouse ventricular myocytes expressing dominant negative Kv1.5α subunit. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H319–H328. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00665.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X-K, Katchman A, Drici M-D, Ebert SN, Ducic I, Morad M, Woosley RL. Gender differences in the cycle length-dependent QT and potassium currents in rabbits. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1998;285:672–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B. Cardiac arrhythmias: From (transgenic) mice to men. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:1089–1092. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.01089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Guo W, Pan X-H, Lee JS, Shusterman V, Rocco CJ, Logothetis Nerbonne JM, Hill JA. Targeted replacement of Kv1.5 in the mouse leads to loss of the 4-aminopyridine-sensitive component of IK,slow and resistance to drug-induced QT prolongation. Circ Res. 2001;88:940–946. doi: 10.1161/hh0901.090929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Jeron A, Zhou J, Buckett P, Han X, Mitchell GF, Koren G. Long QT and ventricular arrhythmias in transgenic mice expressing the N terminus and the first transmembrane segment of a voltage-gated potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2926–2931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HR, Remeysen P, Somers K, Saels A, DeClerck F. Female gender is a risk factor for drug-induced long QT and cardiac arrhythmias in an in vivo rabbit model. J Cardiovasc Electophys. 2001;12:538–545. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire CT, Wakimoto H, Patel VV, Hammer PE, Gauvreau K, Berul CI. Implications of ventricular arrhythmia vulnerability during murine electrophysiology studies. Physiol Genomics. 2003;15:84–91. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00034.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitarai S, Reed TD, Yatani A. Changes in ionic currents and beta-adrenergic receptor signaling in hypertrophied myocytes overexpressing Gα(q) Am J Physiol. 2000;279:H139–H148. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GF, Jeron A, Koren G. Measurement of heart rate and Q-T interval in the conscious mouse. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H747–H751. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.3.H747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Näbauer M, Käab S. Potassium channel downregulation in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:324–334. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahira K, Shi G, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Selective interaction of voltage-gated K+ channel β-subunits with α subunits. J Neurosci. 1996;271:7084–7089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM, Guo W. Heterogeneous expression of voltage-gated K+ channels in the heart: Roles in normal excitation and arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophys. 2002;13:406–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM, Kass RS. Physiology and molecular biology of ion channels contributing to ventricular repolarization. In: Gussak I, editor. Cardiac Repolarization: Bridging Basic and Clinical Sciences. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 2003. pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM, Nichols CG, Schwarz TL, Escande D. Genetic manipulation of cardiac K+ channel function in mice: What have we learned and where do we go from here? Circ Res. 2001;89:944–956. doi: 10.1161/hh2301.100349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TV, Sosunov E, Gainullin RZ, Danilo P, Rosen MR. Impact of sex and gonadal steroids on prolongation of ventricular repolarization and arrhythmias induced by IK blocking drugs. Circulation. 2001;103:2207–2212. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.17.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priori SG, Schwartz PJ, Napolitano C, Bloise R, Ronchetti E, Grillo M, Vicentini A, Spazzolini C, Nastoli J, Bottelli G, Folli R, Cappelletti D. Risk stratification in the long–QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1866–1874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surawicz B. Puzzling gender repolarization gap. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:613–615. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Marbán E. Electrophysiological remodeling in hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:270–283. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trépanier-Boulay V, St-Michel C, Tremblay A, Fiset C. Gender-based differences in cardiac repolarization in mouse ventricle. Circ Res. 2001;89:437–444. doi: 10.1161/hh1701.095644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk R, Cobbe SM, Hicks M, Kane K. Functional, structural, and dynamic basis of electrical heterogeneity in healthy and diseased cardiac muscle: Implications for arrhythmogenesis and anti-arrhythmic drug therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;84:207–231. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Anderson ME. Reduced repolarization reserve in ventricular myocytes from female mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:763–769. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Barry DM, Li H, Brunet S, Guo W, Nerbonne JM. Attenuation of the slow component of delayed rectification, action potential prolongation, and triggered activity in mice expressing a dominant-negative Kv2 alpha subunit. Circ Res. 1999b;85:623–633. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.7.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Guo W, Nerbonne JM. Four kinetically distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. J General Physiol. 1999a;113:661–678. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Jeron A, London B, Han X, Koren G. Characterization of a slowly inactivating outward current in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1998;83:806–814. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.8.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Kidorov S, Muratu M, Buckett PD, Nerbonne JM, Koren G. Regional upregulation of Kv2.1-encoded current, IK,slow2, in Kv1DN mice is abolished by crossbreeding with Kv2DN mice. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:H491–H500. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00576.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]