Abstract

We have recently shown that carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) binds in vitro to the C-terminus of the electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter kNBC1 (kNBC1-ct). In the present study we determined the molecular mechanisms for the interaction between the two proteins and whether kNBC1 and CAII form a transport metabolon in vivo wherein bicarbonate is transferred from CAII directly to the cotransporter. Various residues in the C-terminus of kNBC1 were mutated and the effect of these mutations on both the magnitude of CAII binding and the function of kNBC1 expressed in mPCT cells was determined. Two clusters of acidic amino acids, L958DDV and D986NDD in the wild-type kNBC1-ct involved in CAII binding were identified. In both acidic clusters, the first aspartate residue played a more important role in CAII binding than others. A significant correlation between the magnitude of CAII binding and kNBC1-mediated flux was shown. The results indicated that CAII activity enhances flux through the cotransporter when the enzyme is bound to kNBC1. These data are the first direct evidence that a complex of an electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter with CAII functions as a transport metabolon.

The electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter NBC1 plays an important role in transepithelial bicarbonate absorption, and regulation of intracellular pH in the kidney (Romero et al. 1997; Burnham et al. 1997; Abuladze et al. 1998; Gross & Kurtz, 2002) and pancreas (Abuladze et al. 1998; Marino et al. 1999; Gross et al. 2001a, 2003). The kidney-specific variant of NBC1, kNBC1, is localized on the basolateral membrane of renal proximal tubule (Abuladze et al. 1998; Schmitt et al. 1999) where it mediates cellular efflux of bicarbonate derived from intracellular hydration of CO2 catalysed by the cytoplasmic enzyme carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) (Burckhardt et al. 1984; Sasaki & Marumo, 1989; Seki & Fromter, 1992; Tsuruoka et al. 2001). Previous studies have demonstrated that inhibition of CA activity in the proximal tubule significantly decreases the rate of transepithelial bicarbonate absorption and basolateral sodium bicarbonate efflux (Burg & Green, 1977; McKinney & Burg, 1977; Burckhardt et al. 1984; Sasaki & Marumo, 1989; Seki & Fromter, 1992). Using as a model system the mPCT cell line, which does not mediate electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransport (Gross et al. 2001a,b), we have shown that the complete inhibition of CA by 0.1 mm acetazolamide (ACTZ) decreases the flux through exogenously expressed kNBC1 by ∼65% when the transporter functions with a HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry of 3: 1 (Gross et al. 2002). No inhibition of kNBC1-mediated flux was found when the stoichiometry of the cotransporter was switched to 2: 1 following a protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation of kNBC1-Ser982. In addition, we demonstrated that the C-terminus of kNBC1 (kNBC1-ct) binds CAII in vitro with high (Kd < 0.2 μm) affinity (Gross et al. 2002) suggesting that CAII and kNBC1 may physically interact in vivo. Binding of CAII and kNBC1 would be predicted to replace cytoplasmic diffusion of bicarbonate from CAII to kNBC1 with more efficient intermolecular transfer of bicarbonate between the two proteins thereby potentially enhancing the transport rate of kNBC1.

Reithmeier and colleagues were first to show that another member of the SLC4 bicarbonate cotransporter superfamily, the anion exchanger AE1 also binds CAII (Vince & Reithmeier, 1998; Reithmeier, 2001). AE1 interacts electrostatically via acidic L886DADD motif in its C-terminus with basic residues in the N-terminus of CAII (Vince & Reithmeier, 2000). In addition to acidic aspartate residues, a non-polar leucine has been shown to be required for CAII binding (Vince et al. 2000). Functional studies have demonstrated that CAII stimulates the transport function of AE1, and the anion exchangers AE2 and AE3 (Sterling et al. 2001a). As a model for the CAII-mediated enhancement of HCO3− transport through AE1, it was hypothesized that a complex of AE1 and CAII functions in red blood cells as a transport metabolon. In this model, the efficiency of bicarbonate transport via AE1 is enhanced by the intermolecular transfer of bicarbonate between CAII and AE1, thereby eliminating the slower cytoplasmic diffusion of HCO3− between the two proteins (Vince & Reithmeier, 1998, 2000; Vince et al. 2000; Reithmeier, 2001; Sterling et al. 2001a,b). A similar mechanism had been originally hypothesized to exist in multienzyme complexes catalysing sequential metabolic reactions termed metabolons allowing metabolites to transfer directly between the active sites of the enzymes (Srere, 1985; Velot et al. 1997; Miles et al. 1999).

Our previous finding that the kNBC1-ct binds with high affinity to CAII and that inhibition of CA activity decreases kNBC1-mediated flux (Gross et al. 2002) suggests that these proteins may also form a transport metabolon on the basolateral membrane of proximal tubule cells. Unlike AE1, which transports Cl− and HCO3− with a 1: 1 stoichiometry, kNBC1-mediated transport is electrogenic (Gross & Kurtz, 2002; Kurtz et al. 2004). Whether the electrogenicity of kNBC1 is affected by its interaction with CAII is currently unknown. We have shown that in mPCT cells transfected with exogenous wild-type kNBC1 (wt-kNBC1), the stoichiometry of kNBC1 is 3: 1 (Gross et al. 2001b), similar to the stoichiometry of the electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransport in the basolateral membrane of the renal proximal tubule (Yoshitomi et al. 1987; Muller-Berger et al. 1997a,b; Kunimi et al. 2000; Gross & Kurtz, 2002). Importantly, the stoichiometry was shifted to 2: 1 following treatment of mPCT cells expressing kNBC1 with cAMP (Gross et al. 2001b). This process involved a PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Ser982 in the C-terminus of the cotransporter (Gross et al. 2001b). A similar mechanism of regulation of the cotransporter stoichiometry was shown recently with the pancreatic variant of NBC1, pNBC1 (Gross & Kurtz, 2002; Gross et al. 2003). We have previously shown that Asp986 and Asp988 required for the cAMP induced stoichiometry shift of kNBC1 are located in close proximity to the PKA phosphorylation site, K979KGS (Gross et al. 2002). These aspartate residues are part of a putative D986NDD motif of acidic amino acids that in addition to another putative acidic kNBC1 motif, L958DDV, could be involved in CAII binding. Based on these considerations we hypothesized that a potential mechanism for the cAMP-induced shift in stoichiometry of kNBC1 via phosphorylation of Ser982 may require binding/dissociation of CAII (Gross et al. 2002; Gross & Kurtz, 2002). Whether phosphorylation of Ser982 affected the binding of CAII to kNBC1 or whether binding of CAII interferes with phosphorylation of Ser982 was not determined.

Therefore in the present paper, we studied how binding of CAII to kNBC1 and the activity of the enzyme affect both the flux through the cotransporter and its transport stoichiometry. In addition, we examined the mechanism of the interaction of these proteins by mapping the amino acid residues in kNBC1 responsible for binding of CAII. ACTZ only inhibits kNBC1-mediated flux when the PKA phosphorylation site at Ser982 is not phosphorylated (Gross et al. 2002). Therefore we determined whether the PKA-dependent phosphorylation of kNBC1 affects the binding of CAII. Finally, we examined whether a complex of kNBC1 with CAII functions as a transport metabolon.

Methods

Evaluation of putative kNBC1 amino acid residues involved in binding of CAII

We have previously shown that the C-terminus of kNBC1 binds CAII with high affinity and with the molar ratio 1: 1 (Gross et al. 2002). Analysis of the C-terminus of kNBC1 has revealed two putative acidic motifs, L958DDV and D986NDD, which could potentially be involved in the binding of CAII (Fig. 1). The first motif is similar to the AE1-LDADD sequence involved in binding of CAII (Vince & Reithmeyer, 2000). In the second putative kNBC1 motif, Asp986 and Asp988 are known to be required for the cAMP-mediated shift of kNBC1 stoichiometry from 3: 1 to 2: 1 in proximal tubule cells (Gross et al. 2002).

Figure 1. The kNBC1 C-terminal sequence.

Putative CAII binding motifs are shown using larger size letters. The consensus PKA phosphorylation site is underlined. The target of the PKA phosphorylation in this site, the Ser982 residue, is marked with an asterisk.

Expression and purification of the wild-type and mutant C-terminus of kNBC1

We have recently shown that both the N- and C-termini of the human electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter NBC1 are localized in the cytoplasm (Tatishchev et al. 2003). The coding sequence of the cytoplasmic C-terminal 85 amino acids of the wild-type or mutant kNBC1 (Fig. 1) was inserted into XhoI–EcoRI site of pRSETB vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells as an N-terminally His6-tagged fusion protein (His6–kNBC1-ct). Approximately 25 g of cells were collected by centrifugation at 6000 g for 20 min, washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, containing 140 mm NaCl), and suspended in 250 ml of BugBusterHT reagent (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) containing protease inhibitors: 1 mm phenylmethylsulphonylfluoride (PMSF), 1 mm EDTA, 1 μg ml−1 pepstatin, 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin, and 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin (all protease inhibitors were from Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, the homogenate was centrifuged at 18 000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was dialysed for 16 h at 4°C against PBS, spun at 18 000 g for 20 min, and purified on a Ni-Superflow resin (Novagen) column (2 cm × 8 cm) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Fractions containing His6–kNBC1-ct were combined, dialysed against 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and loaded into a 3 cm × 6 cm column of DEAE-cellulose DE52 (Whatman, Maidstone, Kent, UK) equilibrated with the same buffer. The proteins were eluted with a 0–100 mm gradient of NaCl in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. Fractions containing His6–kNBC1-ct were combined, and then concentrated and transferred to PBS using a Centriplus YM-3 centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). All purification procedures were performed at 4°C. A polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of sodium dodecylsulphate (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting (Fig. 2) showed one protein band, which reacted with a C-terminal NBC1-specific antibody, NBC1-4b2 (Tatishchev et al. 2003), and a penta-His antibody (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The size of the purified fusion protein was ∼15 kDa, in agreement with the size predicted based on the amino acid composition of the construct.

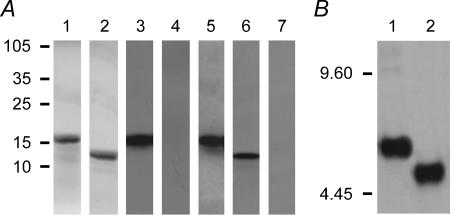

Figure 2. Characterization of kNBC1 C-terminus.

A, characterization of the purified His6-tagged kNBC1-Ct expressed in E. coli cells. SDS-PAGE of the purified His6-tagged C-terminus before (lane 1) and after digestion with enterokinase (lane 2); Coomassie staining. Western blotting of the purified wild-type His6-tagged kNBC1 C-terminus before (lanes 3–5) and after digestion with enterokinase (lanes 6 and 7) probed with the NBC1-4b2 antibody (lanes 3 and 6), with the NBC1-4b2 antibody pre-incubated with the immunizing peptide (lane 4), and with the penta-His antibody from Qiagen (lanes 5 and 7). Loading: 10 mg (lanes 1 and 2), 50 ng (lanes 3–5) and 40 ng (lanes 6 and 7). Positions of size markers in kilodaltons are shown on the left. B, isoelectrofocusing of the His6-tagged kNBC1-ct before (lane 1) and after (lane 2) of the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Ser982. Loading: 200 ng. Western blotting with penta-His antibody (Qiagen). Positions of pI markers are shown on the left.

Determination of the effect of the His6-tagged vector sequence on the binding of the His6–kNBC1-ct to CAII

The 36 amino acid His6-containing vector sequence of ∼3 kDa could potentially affect the binding characteristics of the C-terminus of kNBC1. Therefore the His6–kNBC1-ct construct was treated with a recombinant enterokinase (Novagen) to hydrolyse the enterokinase site between the vector and C-terminal coding region of kNBC1. After digestion was completed, which was determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with NBC1-4b2 and penta-His (Qiagen) antibodies (Fig. 2), the enterokinase was absorbed on enterokinase-capture beads (Novagen). The vector sequence containing His6-tag was purified on a Ni-Superflow resin (Novagen) column (2 cm × 8 cm). The binding of the un-tagged kNBC1-ct and His6–kNBC1-ct to CAII was measured and compared using Western blotting with the NBC1-4b2 antibody. The results indicated that the binding of His6–kNBC1-ct was not significantly different from the untagged kNBC1-ct. Silver staining of the SDS gels with a kit from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA) confirmed the results of Western blotting. Therefore, the His6-tagged wild-type or mutant kNBC1 constructs were used in binding experiments.

Mutagenesis of the full-length kNBC1 and kNBC1-ct

All mutations in the full-length human kNBC1 and the C-terminus of human kNBC1 were performed using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Sequences of all constructs were confirmed by bidirectional sequencing using a ABI 310 sequencer (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA, USA).

Expression and purification of GST-tagged human CAII

The coding sequence of human CAII was inserted into the XhoI–NotI site of pGEX-4T-3 vector (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and expressed in E. coli BL21 cells as a fusion glutathione transferase (GST) construct (GST-CAII). Approximately 50 g of cells were collected by centrifugation at 6000 g for 20 min, washed 3 times with PBS, and suspended in 250 ml of BugBusterHT reagent (Novagen) containing protease inhibitors. After incubation for 20 min at room temperature, the homogenate was centrifuged at 18 000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was purified on a 2 cm × 6 cm Glutathione Sepharose Fast Flow column (Amersham Biosciences) using the manufacturer's protocol. The purity of the GST-CAII construct was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using anti-GST antibody (Amersham Biosciences). Part of the purified construct was dialysed against deionized water, lyophilized and used for CAII quantification in binding experiments using the Western blotting technique. The rest of the purified GST-CAII was incubated with 20 ml of Glutathione Sepharose for 16 h at 4°C. The unbound GST-CAII was washed with PBS, and the amount of bound GST-CAII per 1 ml of the beads was detected using Western blotting with the anti-GST antibody.

Binding of His6–kNBC1-ct to GST-CAII

Glutathione Sepharose beads (20 μl) with coupled GST-CAII (see previous protocol) were incubated with 1 ml of 1 μm wild-type or mutant His6–kNBC1-ct in PBS for 16 h at 4°C. After centrifugation at 12 000 g for 15 s in an Eppendorf 5415C microcentrifuge, the supernatant was collected and combined with supernatants derived from three washes of the beads with 1 ml of PBS each. The amount of the His6–kNBC1-ct in the supernatant and bound to the beads was measured using Western blotting with both NBC-4b2 and penta-His (Qiagen) antibodies. Each blot was calibrated with the known amounts of His6–kNBC1-ct. The measurements were only performed in the linear range of each calibration curve. Each binding experiment was repeated 4–5 times. For quantification of His6–kNBC1-ct, different amounts of His6–kNBC1-ct and lysozyme (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) were resolved on SDS-PAGE. The gels were stained with Coomassie blue R (Sigma), scanned on an UMAX PowerLook III scanner and analysed using Adobe Photoshop 7 software (Adobe Systems). The intensity of the His6–kNBC1-ct bands was determined by comparison of their intensity with the intensity of lysozyme bands of known amounts.

In vitro phosphorylation of the His6–kNBC1-ct

The His6–kNBC1-ct contains one putative PKA phosphorylation site at Ser982. We have previously shown that Ser982 is the only kNBC1 amino acid that can be phosphorylated by PKA (Abuladze et al. 1998; Gross et al. 2001b). Approximately 100 μg of the purified His6–kNBC1-ct was incubated in 1 ml of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 10 mm ATP, 2 mm MgCl2 and 200 U of bovine heart PKA (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). After incubation for 20 h at 20°C, the solution was passed consecutively through a Centriplus YM-30 and a Centriplus YM-3 centrifugal filter devices (Millipore). The concentrate was transferred into PBS and analysed by isoelectrofocusing on Criterion IEF ready gels (Bio-Rad), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and analysed by Western blotting with both NBC1-4b2 and penta-His (Qiagen) antibodies. A single band with an isoelectric point more acidic than the non-phosphorylated His6–kNBC1-ct was detected (Fig. 2). The concentrate did not have PKA activity.

Binding of kNBC1 to CAII in mouse kidney extracts

Mice were killed on the day of study by exposure to CO2 and the kidneys removed and used for the binding studies. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of California, Los Angeles. Approximately 1 g of mouse kidney was disrupted in 20 ml BugBusterHT reagent (Novagen) containing protease inhibitors. After incubation for 2 h at 4°C, the homogenate was centrifuged at 18 000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was dialysed for 16 h at 4°C against PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, spun at 18 000 g for 20 min, and the resulting supernatant was passed through a Glutathione Sepharose column (1 cm × 1 cm) with bound full-length CAII. After washing with 500 ml PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100, proteins bound to the column were eluted with 1 × SDS buffer and analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the NBC1-4b2 antibody.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

SDS-PAGE was performed using 15% polyacrylamide ready gels from Bio-Rad. Proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were electrotransferred onto PVDF membrane (Amersham Biosciences). Non-specific binding was blocked by incubation for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 140 mm NaCl) containing 5% dry milk and 0.05% Tween 20 (Bio-Rad). The NBC-4b2 NBC1-ct-specific antibody and mouse penta-His antibody (Qiagen) were used at dilutions 1: 1000 and 1: 5000, respectively. Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated species-specific antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) were used at a dilution 1: 20 000. Bands were visualized using ECL kit and ECL hyperfilm (Amersham Biosciences).

Cell culture and transfection

The experiments were performed with the mouse proximal tubule mPCT cell line, which lacks endogenous electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransport (Gross et al. 2001a). Cells were studied between passages 15 and 25. Cells were transiently transfected with kNBC1constructs as previously described (Gross et al. 2001a). For transfection, cells were grown in mouse renal tubular epithelium (mRTE) medium containing a 1: 1 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F12 medium and the following additives: 10 ng ml−1 EGF, 5 μg ml−1 insulin, 5 μg ml−1 transferrin, 4 μg ml−1 dexamethasone, 10 units ml−1 interferon-γ, 2 mm glutamine and 5% fetal bovine serum, on filters. Cells were transfected with the corresponding plasmid using Lipofectamine (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Mock-transfected cells were transfected with the vector only. All plasmids were purified with Endofree™ plasmid purification kit (Qiagen) prior to their use.

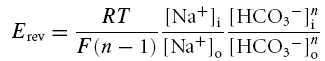

HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry and cotransporter flux

mPCT cells were grown on permeable filter supports, mounted in an Ussing chamber, and permeabilized with amphotericin B as previously described (Gross et al. 2001a,b). The stoichiometry of the cotransporter was determined from Erev and eqn (1) (Gross et al. 2001a,b):

|

where n is the number of bicarbonate anions cotransported with each sodium cation, the subscripts i and o represent intra- and extracellular concentrations of the indicated ion and R, T and F have their usual meaning. The HCO3−: Na+ transport stoichiometry refers generically to the ratio of the anion charge to cation charge transported by kNBC1 without making a distinction as to whether HCO3− and/or CO32− is the transported species (Kurtz et al. 2004). Briefly, Erev of the cotransporter was determined from measurements of the current—voltage (I–V) relationships at a 5-fold Na+ concentration gradient as previously described (Gross et al. 2001a,b). Flux through the cotransporter was defined as the dinitrostilbene disulphonate (DNDS)-sensitive current. Only transfected cell monolayers for which the DNDS-sensitive current was at least 10-fold larger then that of the corresponding mock-transfected cells were included in this study. About 30% of all transfected cell monolayers met the inclusion criterion.

Statistics

Experiments were performed at least 4 times. The results for the reversal potential and stoichiometry are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. Student's unpaired t test was used for statistical analysis, with P < 0.05 considered significant. Dunnet's t test was used to compare multiple experimental groups with controls.

Results

Binding of the wild-type and mutant kNBC1-ct to CAII

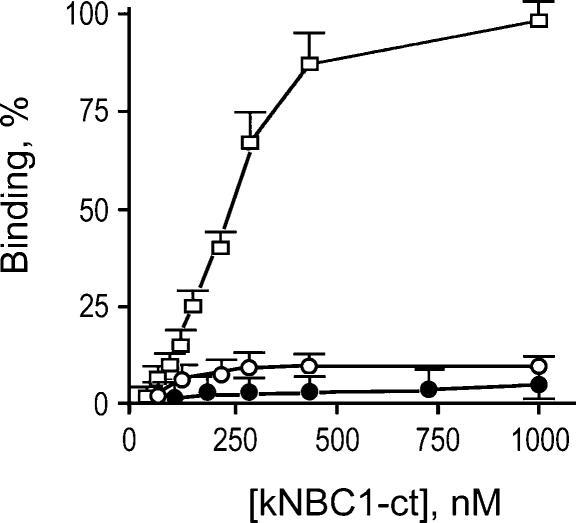

Binding of human wt-kNBC1-ct to the human CAII is illustrated in Fig. 3. The data indicate that non-specific binding to Glutathione Sepharose is ∼5% of the total binding at 1 μm concentration of the binding peptide. This concentration was utilized in the binding studies with the wild-type or mutant kNBC1-ct variants. Binding of the N986NNN mutant of kNBC1-ct to CAII at this concentration was ∼10% of the wild-type kNBC1-ct (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Binding of wild-type and mutated kNBC1-ct to CAII.

The binding of wild-type (□) and the N986NNN mutant His6–kNBC1-ct (○) constructs to GST-CAII bound to Glutathione Sepharose beads was determined. In control experiments binding of the purified human His6-tagged wild-type kNBC1-ct to Glutathione Sepharose beads alone was studied (•). The data are shown as a percentage of maximum wild-type kNBC1-ct binding.

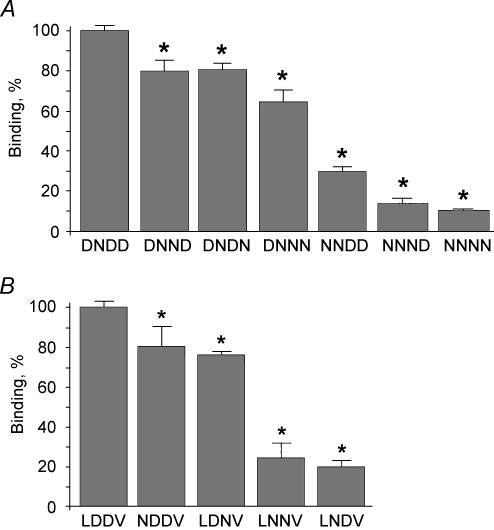

Figure 4A summarizes the results of binding to CAII of the kNBC1-ct constructs mutated in the D986NDD motif. The replacement of all three aspartates with asparagines decreased CAII binding by ∼90% supporting the hypothesis of the involvement of acidic amino acid residues in this process. Replacement of Asp986 with asparagine decreased the binding by ∼70%. Asp988 and Asp989 were responsible for ∼20% and ∼15% of total binding, respectively. Therefore Asp988 and Asp989 play a significantly less important role in the interaction between the kNBC1-ct and CAII than Asp986.

Figure 4. Binding of kNBC1-ct constructs to CA II.

A, binding of the kNBC1-ct constructs mutated in the D986NDD site to CAII bound to Glutathione Sepharose beads. The experiments were performed using wild-type and mutant kNBC1-ct constructs (1 μm). The data are depicted as a percentage of the wild-type kNBC1-ct value. The asterisk represents statistical significance. B, binding of the kNBC1-ct constructs mutated in the L958DDV site to CAII bound to Glutathione Sepharose beads. The experiments were performed using wild-type and mutant kNBC1-ct constructs (1 μm). The data are depicted as a percentage of the wild-type kNBC1-ct value. The asterisk represents statistical significance.

The data presented in Fig. 4B indicate that more than one acidic amino acid motif in the C-terminus of kNBC1 is involved in CAII binding. The replacement of both aspartates in the L958DDV motif decreased CAII binding by ∼75% indicating that the acidic amino acid residues in this motif are also important for CAII binding. Comparison of the single residue mutants L958DNV and L958NDV indicated that Asp959 in the L958DDV motif is significantly more important for CAII binding than Asp960 (80% versus 25%). The replacement of Leu958 with asparagine decreased the binding by ∼20%, contrary to the lack of binding shown for replacement of leucine in the LDADD motif of AE1 (Vince et al. 2000). The data indicate that Asp959 plays a key role in binding of CAII to the L958DDV motif of kNBC1 and that Leu958 and Asp960 play a minor role in binding to CAII.

The data shown in Fig. 4 indicate that two clusters of acidic amino acids in the C-terminus of kNBC1 are involved in binding of CAII. Furthermore, the data suggest that the first aspartates in these clusters, Asp959 and Asp986, are very important for the strength of the interaction, whereas Asp988 and Asp989 in the D986NDD motif, and Asp960 and also Leu958 in the L958DDV motif play significantly smaller roles.

Binding of the full-length kNBC1 to CAII in mouse kidney extracts

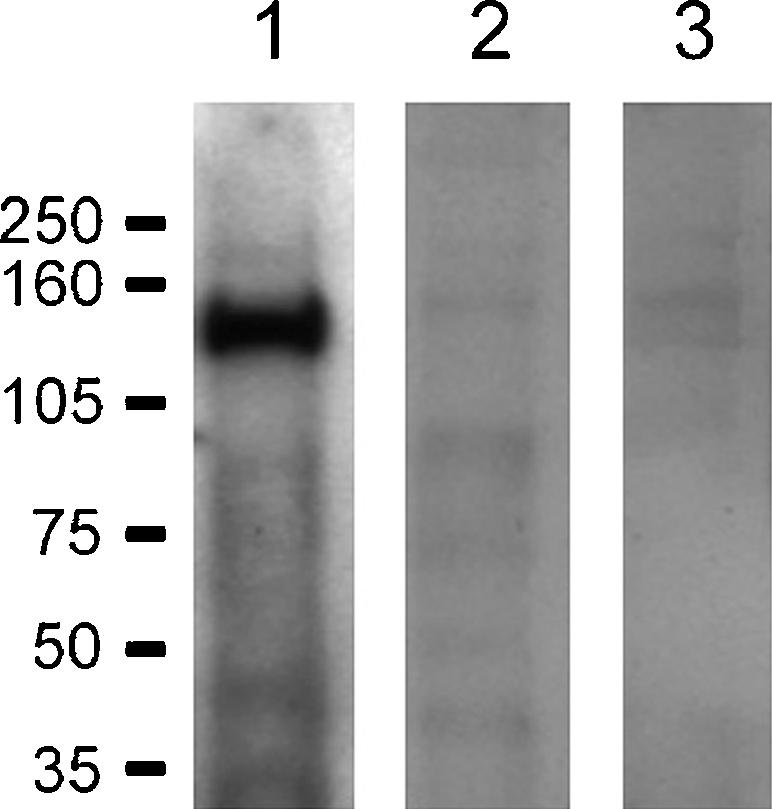

Additional studies were performed to determine whether the full-length wt-kNBC1 could bind CAII. The wt-kNBC1 extracted from mouse kidney, which is highly homologous (97% identity) to the full-length human kNBC1 with identical L958DDV and D986NDD motifs in the C-terminus, was passed through a Glutathione Sepharose column with the bound wt-CAII. The results of this experiment, presented in Fig. 5, indicate that CAII binds to the full-length wt-kNBC1 confirming results of the in vitro binding of the recombinant kNBC1-ct to CAII.

Figure 5. CAII binding to mouse kidney kNBC1.

A mouse kidney extract was passed through a Glutathione Sepharose column with (lanes 1 and 2) and without (lane 3) bound purified CAII and analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Probed with the NBC1-4b2 (lanes 1 and 3) and NBC1-4b2 antibody pre-incubated with the immunizing peptide (lane 2).

Effect of the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Ser982 in kNBC1 on CAII binding

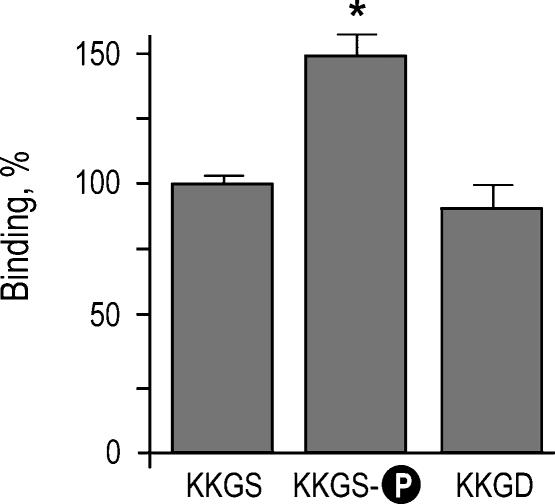

We have previously shown that ACTZ inhibits flux through kNBC1 in mPCT cells when it functions with a transport stoichiometry of 3 : 1 and does not affect the flux in the 2 : 1 mode (Gross et al. 2002). The stoichiometry of the cotransporter was shifted from 3 : 1 to 2 : 1 following the PKA-dependent phosphorylation of kNBC1-Ser982 (Gross et al. 2001b). Furthermore, we hypothesized (Gross & Kurtz, 2002) that the phosphorylation of kNBC1-Ser982 might prevent binding of CAII to the cotransporter. Therefore in the present study we determined how phosphorylation of Ser982 affects the binding of CAII. For these experiments, the C-terminal His6-tagged kNBC1 construct was in vitro phosphorylated by PKA and used in the CAII binding assay. The results (Fig. 6) show that phosphorylation of Ser982 increases the binding of CAII. The replacement of Ser982 with acidic aspartate residue known to mimic negatively charged phosphate at physiological pH (Hoeffler et al. 1994; Kwak et al. 1999; Lin et al. 2000) did not significantly change the binding of kNBC1-ct to CAII, indicating that the interaction is not only charge but also size specific.

Figure 6. Effect of phosphorylation of Ser982 and replacement of Ser982 with aspartate on binding of kNBC1 to CAII.

The experiments were performed using wild-type and modified kNBC1-ct at 1 μm. The data are depicted as a percentage of the wild-type kNBC1-ct value. The asterisk represents statistical significance.

We have previously shown (Gross et al. 2002) that the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of kNBC1-Ser982 required for the shift in the cotransporter stoichiometry from 3: 1 to 2: 1 is also dependent on two aspartate residues in the C-terminus of the cotransporter, Asp986 and Asp988. These two residues were also shown in the present study to also be involved in CAII binding with Asp986. The involvement of Asp986 and Asp988 in both binding of CAII and the cAMP-mediated shift of kNBC1 stoichiometry suggests that binding of CAII may be necessary for the cotransporter stoichiometry shift.

Lack of effect of CAII binding on the baseline HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry of kNBC1

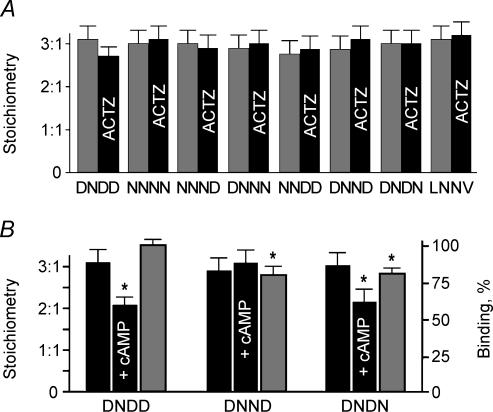

The functional significance of the binding data was evaluated in electrophysiological studies using mPCT cells transfected with the wild-type and mutant kNBC1 constructs. Two functional parameters were determined in these studies: the HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry of kNBC1 and the flux through the cotransporter. Figure 7A summarizes the effect of CAII binding on kNBC1 stoichiometry. All the L958DDV and D986NDD motif mutants retain a stoichiometry of 3: 1 as in wt-kNBC1, indicating that binding of CAII to wt-kNBC1 does not affect the baseline cotransporter stoichiometry. In order to determine whether loss of CAII activity without perturbing its binding to kNBC1 affected the cotransporter stoichiometry, additional experiments were done using mPCT cells expressing wt-kNBC1. Following inhibition of CAII activity with 0.1 mm ACTZ, the stoichiometry of kNBC1 remained 3 : 1. In mutants with decreased binding ACTZ also did not affect the kNBC1 stoichiometry indicating inhibition of CA activity not associated with kNBC1 also does not affect the cotransporter stoichiometry. Therefore neither binding of CAII to kNBC1 nor inhibition of its enzymatic activity affects the baseline stoichiometry of the cotransporter.

Figure 7. Stoichiometry of kNBC1 constructs.

A, lack of effect of ACTZ (0.1 mm) on the HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry of the wild-type and mutant kNBC1 constructs expressed in the mPCT cells. Control (grey bars); ACTZ (black bars). B, role of kNBC1-Asp986 and Asp988. The Asp986 and Asp988 in the D986NDD motif of kNBC1 are involved in the PKA-mediated shift of the cotransporter stoichiometry (black columns) and in CAII binding (grey columns). The asterisk represents statistical significance.

Role of CAII in shifting the HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry of kNBC1 from 3 : 1 to 2 : 1

We have previously shown (Gross et al. 2001b) that the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Ser982 in kNBC1 shifts the cotransporter stoichiometry from 3 : 1 to 2 : 1. The stoichiometry shift is dependent on two aspartate residues in the C-terminus of the cotransporter, Asp986 and Asp988 (Gross et al. 2002), which are components of the D986NDD motif also involved in CAII binding (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that CAII binding to the D986NDD motif is associated with the PKA-mediated shift of kNBC1 stoichiometry. Nevertheless, two mutants with similar binding of CAII were identified, D986NND and D986NDN (Fig. 7A), of which only one (D986NDN) was able to shift the stoichiometry from 3 : 1 to 2 : 1. Both mutants were associated with a ∼20% decrease in CAII binding (Fig. 7A). Therefore, the inability of cAMP treatment to shift the HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry in the D986NND mutant was not associated with decreased CAII binding. These findings suggest that Asp988 and Asp989 play similar roles in CAII binding, but that factor(s) other than CAII binding are also likely to be involved in the PKA-mediated shift in kNBC1 transport stoichiometry.

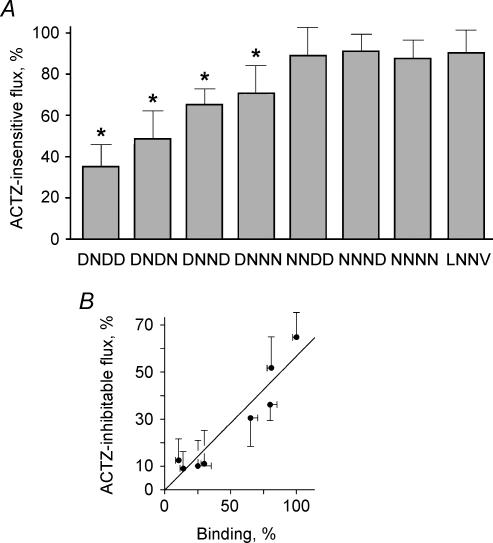

Effect of CAII on kNBC1-mediated flux: evidence that the complex of kNBC1 and CAII functions as a transport metabolon

Inhibition of CAII activity decreased the flux through kNBC1 by ∼65% when the cotransporter functions with a 3 : 1 transport stoichiometry (Fig. 8A). Further studies were done to determine whether the ability of the enzymatic activity of CAII to modulate the flux through the cotransporter requires that the proteins bind normally. In these experiments, the ability of ACTZ to inhibit the flux through kNBC1 was assessed in mPCT cells expressing kNBC1 mutants with different ability to bind CAII in vitro. As shown in Fig. 8A, in the kNBC1 mutants, which had impaired CAII binding, the ability of ACTZ to inhibit kNBC1-mediated flux was also significantly diminished. Moreover, mutation of the L958DDV and D986NDD motifs showed that there was a significant positive linear correlation (r = 0.95) between CAII binding and flux inhibition by ACTZ (Fig. 8B). The flux through the kNBC1 N986NNN and N986NND mutants with significantly impaired binding to CAII was not affected by ACTZ (Figs 8A and B). The data indicate that when CAII is bound to kNBC1, its enzymatic activity can efficiently enhance the current through the cotransporter, whereas the activity of unbound (cytoplasmic) CAII does not appear to play a role in kNBC1-mediated transport. Based on these findings, we propose that a complex of kNBC1 and CAII exists on the basolateral membrane of the proximal tubule cells that functions as a transport metabolon.

Figure 8. kNBC1 and CA II form a transport metabolon.

A, effect of ACTZ (0.1 mm) on the flux mediated by wild-type and mutant kNBC1 constructs expressed in mPCT cells. In these experiments, the baseline flux measured without ACTZ was in a range of 8.1 ± 1 to 18.1 ± 2 μA cm−2. The ACTZ-insensitive flux was measured in the presence of ACTZ (0.1 mm) and is shown as a percentage of the flux measured on the same filter without ACTZ. B, positive linear correlation between the ACTZ-inhibitable flux through wild-type and mutant kNBC1 constructs and binding to CAII (r = 0.95). The asterisk represents statistical significance.

Discussion

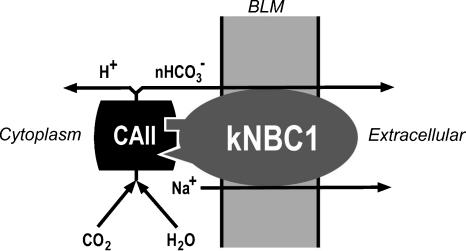

In this study we have shown that the electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter kNBC1 and CAII form a complex and that the enzymatic activity of CAII bound to kNBC1 enhances the flux through kNBC1. The data are compatible with a model wherein the complex of kNBC1 and CAII functions as a transport metabolon in proximal tubule cells (Fig. 9). This is the first report of a transport metabolon involving an electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter. The finding that ACTZ significantly inhibits the flux through wt-kNBC1 without altering the stoichiometry of the cotransporter indicates that the enzymatic activity of CAII is involved in the modulation of the flux through the cotransporter and not its baseline HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry. We hypothesize that elimination of the bicarbonate diffusion step between the active sites of CAII and transport site of kNBC1 is responsible for enhancing the flux through the cotransporter.

Figure 9. Hypothetical model of the kNBC1-CAII transport metabolon at the basolateral membrane of the proximal tubule cells.

Our results indicate that the enzymatic activity of CAII bound to kNBC1 plays a role in modulating flux through the cotransporter and not its baseline HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry. The finding that Asp986 and Asp988 in kNBC1 are involved in the interaction of the two proteins and are required in the PKA-dependent shift of the cotransporter stoichiometry suggests that binding of CAII to kNBC1 might be required to shift the cotransporter stoichiometry in response to cAMP. The C-terminal PKA phosphorylation site in kNBC1 has been shown to be involved in regulation of its HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry (Gross et al. 2001b, 2002). The phosphorylation of Ser982, which is located in close proximity to the D986NDD motif, did not decrease but rather increased the binding of kNBC1 to CAII. This finding suggests that CAII is bound to kNBC1 whether or not it is phosphorylated. Comparison of two mutants, D986NND and D986NDN with near identical binding characteristics indicate that the Asp988 and Asp989 play different roles in the stoichiometry shift. Exposure of the D986NDN mutant to 8-Br-cAMP shifted its transport stoichiometry from 3: 1 to 2: 1 similar to wt-kNBC1. In contrast, 8-Br-cAMP failed to shift the stoichiometry of the D986NND mutant. The results suggest that although the contribution of the Asp988 and Asp989 to CAII binding is minor and similar, their requirement for the cAMP-mediated shift of kNBC1 stoichiometry differs. Whether other protein(s) might be involved in this process requires further study.

We identified in the C-terminus of kNBC1 two acidic motifs, L958DDV and D986NDD involved in binding to CAII. Since kNBC1 binds CAII in a 1: 1 molar ratio (Gross et al. 2002) and therefore has one CAII binding site, our data suggest that the CAII binding site in kNBC1 consists of at least two acidic motifs (Fig. 9). In contrast, only one acidic motif, LDADD, in the C-terminus of AE1 was shown to be responsible for the binding to CAII (Vince et al. 2000). The reason for this difference is not clear but could arise from the different experimental techniques used for CAII binding assay in our study and by Vince et al. (2000). Specifically, in the current study, immobilization techniques were not used, which could potentially modify the CAII binding sites on the cotransporter. Of interest, Dahl et al. (2003) have shown that additional C-terminal amino acid residues in the kidney variant of AE1 (kAE1) are required for the CAII-enhanced kAE1-mediated bicarbonate transport. In contrast to AE1, the leucine residue in the L958DDV motif in kNBC1 is not absolutely required for the CAII binding since its replacement with asparagine decreased the binding only by 20%. The difference between L958DDV (kNBC1) and LDADD (AE1) motifs in CAII binding suggested that additional amino acid residues in the C-terminus of kNBC1 might be involved in the enzyme binding. This hypothesis was further supported in the experiments demonstrating the role of a second kNBC1 acidic motif, D986NDD, in CAII binding.

Analysis of the homology between members of the SLC4 bicarbonate transporter superfamily suggests that they might bind CAII through their C-termini. Recent data indicate that CAII binds not only to AE1, but also in addition to AE2 and AE3 (Sterling et al. 2002), NBC3 (Loiselle et al. 2004), and NBC4 (Kurtz et al. unpublished observations). In addition, Alvarez et al. (2003) have shown that carbonic anhydrase IV interacts with pNBC1. It is interesting to note that a bicarbonate transporter down-regulated in adenoma (DRA), which belongs to the SLC26 gene family, binds CAII to a significantly lesser extent than kNBC1 and AE1 (Sterling et al. 2003). It was therefore suggested that the transport activity of DRA is not modulated by CAII binding. Importantly, the 42 amino acid C-terminus of DRA used by Sterling et al. (2003) in their binding experiments did not contain clusters of acidic amino acids that could potentially bind CAII. The membrane topology prediction analysis (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/TMPRED_form.html) indicates that the C-terminal domain of DRA is longer than 42 residues and contains acidic amino acid clusters that might be involved in CAII binding. Importantly, treatment of the DRA-expressing HEK293 cells with 0.1 mm ACTZ decreased their bicarbonate transport activity by 53% indicating that CA activity is important for the DRA-mediated bicarbonate transport. Therefore, additional experiments are required to determine whether CAII binds to DRA, and to evaluate the importance of this potential interaction for the DRA-mediated bicarbonate transport as well as other bicarbonate transporting members of the SLC26 family.

In the proximal tubule, intracelluluar CAII enhances the rate of hydration of CO2 to form H2CO3, which dissociates to H+ that is recycled across the apical membrane via the Na+–H+ exchanger isoform NHE3 (Biemesderfer et al. 1997, 2001), and HCO3−, which is transported across the basolateral membrane via kNBC1. Recently, it has been shown that CAII binds another member of the Na+–H+ exchanger gene family, NHE1 (Li et al. 2002), and the two proteins may function as a transport metabolon. (Li et al. 2002). Whether NHE3 is capable of interacting with CAII has not been addressed. Ion flux through NHE3 and kNBC1 is currently thought to be coupled via various factors including intracellular Na+ and pH/HCO3−, and PKA-dependent phosphorylation of each transporter (Kurashima et al. 1977; Gross et al. 2001b). Whether changes in intracellular Na+ and pH/HCO3− can alter the extent of binding of CAII to kNBC1 and provide an additional mechanism for modulating its transport properties remains to be determined. Furthermore, the concept that not only kNBC1 but in addition NHE3 can bind CAII and function as a transport metabolon is an attractive hypothesis that requires further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DK63125, DK58563, and DK07789, the Max Factor Family Foundation, the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation, the Frederika Taubitz Foundation, the National Kidney Foundation of Southern California J891002, and AHA (Western State Affiliate) grant 0365022Y.

References

- Abuladze N, Lee I, Newman D, Hwang J, Boorer K, Pushkin A, Kurtz I. Molecular cloning, chromosomal localization, tissue distribution, and functional expression of the human pancreatic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17689–17695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez BV, Loiselle FB, Supuran CT, Schuartz GJ, Casey JR. Direct extracellular interaction between carbonic anhydrase IV and the human NBC1 sodium/bicarbonate co-transporter. Biochemistry. 2003;42:12321–12329. doi: 10.1021/bi0353124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemesderfer D, DeGray B, Aronson PS. Active (9.6 S) and inactive (21, S0 oligomers of NHE3 in microdomains of the renal brush border. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10161–10167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemesderfer D, Rutherford PA, Nagy T, Pizzonia JH, Abu-Alfa AK, Aronson PS. Monoclonal antibodies for high-resolution localization of NHE3 in adult and neonatal rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:F289–F299. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.2.F289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt BC, Cassola AC, Fromter E. Electrophysiological analysis of bicarbonate permeation across the peritubular cell membrane of rat kidney proximal tubule. II. Exclusion of HCO3− effects on other ion permeabilities and of coupled electroneutral HCO3− transport. Pflugers Arch. 1984;401:43–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00581531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg M, Green N. Bicarbonate transport by isolated perfused rabbit proximal tubules. Am J Physiol. 1977;233:F307–F314. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1977.233.4.F307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham C, Amlal H, Wang Z, Shull GE, Soleimani M. Cloning and functional expression of a human kidney Na+-HCO3− cotransporter. J Biol Chem. 1997;72:19111–19114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl NK, Jiang L, Chernova MN, Stuart-Tilley AK, Shmukler BE, Alper SL. Deficient HCO3− transport in an AE1 mutant with normal Cl− transport can be rescued by carbonic anhydrase II presented on an adjacent AE1 protomer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44949–44958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Fedotoff O, Pushkin A, Abuladze N, Newman D, Kurtz I. Phosphorylation-induced modulation of pNBC1 function. distinct roles for the amino- and carboxy-termini. J Physiol. 2003;549:673–682. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Hawkins K, Abuladze N, Pushkin A, Cotton CU, Hopfer U, Kurtz I. The stoichiometry of the electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter NBC1 is cell-type dependent. J Physiol. 2001a;531:597–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0597h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Hawkins K, Pushkin A, Abuladze N, Hopfer U, Sassani P, Dukkipati R, Kurzt I. Phosphorylation of Ser982 in kNBC1 shifts the HCO3−: Na+ stoichiometry from 3: 1 to 2: 1 in proximal tubule cells. J Physiol. 2001b;537:659–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00659.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Kurtz I. Structural determinants and significance of regulation of electrogenic Na+-HCO3− cotransporter stoichiometry. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:F876–F587. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00148.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Pushkin A, Abuladze N, Fedotoff O, Kurtz I. Regulation of the sodium bicarbonate cotransporter kNBC1 function: role of Asp986, Asp988 and kNBC1-carbonic anhydrase II binding. J Physiol. 2002;544:679–685. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffler WK, Levinson AD, Bauer EA. Activation of c-Jun transcription factor by substitution of a charged residue in its N-terminal domain. Nucl Acid Res. 1994;22:1305–1312. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.7.1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunimi M, Muller-Berger S, Hara C, Samarzija I, Seki G, Fromter E. Incubation in tissue culture media allows isolated rabbit proximal tubules to regain in-vivo-like transport function: response of HCO3− absorption to norepinephrine. Pflugers Arch. 2000;440:908–917. doi: 10.1007/s004240000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurashima K, Yu FH, Cabado AG, Szabo EZ, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Identification of sites required for down-regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 activity by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1977;272:28672–28679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz I, Petrasek D, Tatishchev S. Molecular mechanisms of electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransport: structural and equilibrium thermodynamic considerations. J Membr Biol. 2004;197:77–90. doi: 10.1007/s00232-003-0643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak YG, Hu N, Wei J, George AL, Jr, Grobaski TD, Tamkun MM, Murray KT. Protein kinase A phosphorylation alters Kvβ1.3 subunit-mediated inactivation of the Kv1.5 potassium channel. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13928–13932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Alvarez B, Casey JR, Reithmeier RAF, Fleigel L. Carbonic anhydrase II binds to and enhances activity of Na+/H+ exchanger. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36085–36091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YF, Jan YN, Jan LY. Regulation of ATP-sensitive potassium channel function by protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation in transfected HEK293 cells. EMBO J. 2000;19:942–955. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle FB, Molgan PE, Alvarez BV, Casey JR. Regulation of the human NBC3 Na+/HCO3− cotransporter by Carbonic anhydrase II & PKA. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:C1423–C1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00382.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney TD, Burg M. Bicarbonate and fluid absorption by renal proximal straight tubules. Kidney Int. 1977;12:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.1977.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino CR, Jeanes V, Boron WF, Schmitt BM. Expression and distribution of the Na+-HCO3− cotransporter in human pancreas. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G487–G494. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.2.G487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles EW, Rhee S, Devies DR. The molecular basis of substrate channeling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12193–12196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Berger S, Coppola S, Samarzija I, Seki G, Fromter E. Partial recovery of in vivo function by improved incubation conditions of isolated renal proximal tubule. I. Change of amiloride-inhibitable K+ conductance. Pflugers Arch. 1997b;434:373–382. doi: 10.1007/s004240050410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Berger S, Nesterov VV, Fromter E. Partial recovery of in vivo function by improved incubation conditions of isolated renal proximal tubule. II. Change of Na-HCO3 cotransport stoichiometry and of response to acetazolamide. Pflugers Arch. 1997a;434:383–391. doi: 10.1007/s004240050411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reithmeier RAF. A membrane metabolon linking carbonic anhydrase with chloride/bicarbonate anion exchangers. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:85–89. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2000.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero MF, Hediger MA, Boulpaep EL, Boron WF. Expression cloning and characterization of a renal electrogenic Na+/HCO3− cotransporter. Nature. 1997;387:409–413. doi: 10.1038/387409a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Marumo F. Effects of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors on basolateral base transport of rabbit proximal straight tubule. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:F947–F952. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.6.F947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt BM, Biemesderfer D, Romero MF, Boulpaep EL, Boron WF. Immunolocalization of the electrogenic Na+-HCO3− cotransporter in mammalian and amphibian kidney. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:F27–F38. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.1.F27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki G, Fromter E. Acetazolamide inhibition of basolateral base exit in rabbit renal proximal tubule S2 segment. Pflugers Arch. 1992;422:60–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00381514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srere PA. The metabolon. Trends Biochem Sci. 1985;10:109–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling D, Alvarez BV, Casey JR. The extracellular component of a transport metabolon. Extracellular loop 4 of the human AE1 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger binds carbonic anhydrase IV. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25239–25246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling D, Brown NJ, Supuran C, Casey JR. The functional and physical relationship between the DRA bicarbonate transporter and carbonic anhydrase II. Am J Physiol. 2003;283:C1522–C1529. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00115.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling D, Reithmeier RAF, Casey JR. A transport metabolon. Functional interaction of carbonic anhydrase II and chroride/bicarbonate exchangers. J Biol Chem. 2001a;276:47886–47894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling D, Reithmeier RAF, Casey JR. Carbonic anhydrase: in the driver's seat for bicarbonate transport. J Pancreas. 2001b;2:165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatishchev S, Abuladze N, Pushkin A, Newman D, Lu W, Weeks D, Sachs G, Kurtz I. Identification of membrane topography of the electrogenic sodium bicarbonate cotransporter pNBC1 by in vitro transcription/translation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:755–765. doi: 10.1021/bi026826q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruoka S, Swenson ER, Petrovic S, Fujimura A, Schwartz GJ. Role of basolateral carbonic anhydrase in proximal tubular fluid and bicarbonate absorption. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:F146–F154. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.1.F146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velot C, Mixon MB, Tiege M, Srere PA. Model of the quinary structure between Krebs TCA cycle enzymes. a model for the metabolon. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14271–14276. doi: 10.1021/bi972011j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince JW, Carlsson U, Reithmeier RA. Localization of the Cl−/HCO3− anion exchanger binding site to the amino-terminal region of carbonic anhydrase II. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13344–13349. doi: 10.1021/bi0015111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince JW, Reithmeier RAF. Carbonic anhydrase II binds to the carboxyl-terminus of human band 3, the erythrocyte Cl−/HCO3− exchanger. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28430–28437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince JW, Reithmeier RAF. Identification of the carbonic anhydrase II binding site in the Cl−/HCO3− anion exchanger AE1. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5527–5533. doi: 10.1021/bi992564p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshitomi K, Burckhardt BC, Fromter E. Rheogenic sodium-bicarbonate transport in the peritubular cell membrane of rat renal proximal tubule. Pflugers Arch. 1987;405:360–366. doi: 10.1007/BF00595689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]