Abstract

Hindlimb unloading (HU) is an animal model of microgravity and bed rest. In these studies, we examined the role of ingestive behaviours in regulating body fluid balance during 24 h HU. In the first experiment, all rats were given distilled water to drink while two groups were also given access to a sodium chloride solution (0.9% or 1.8%). Water and saline intakes were measured before, during and after 24 h of HU. Rats reduced water intake during 24 h HU in all conditions. During HU, rats increased their intakes of both saline solutions (0.9% NaCl (n = 11): control 7.8 ± 3 ml; HU 18.2 ± 4 ml; recovery 8.9 ± 2.5 ml; 1.8% NaCl (n = 7): control 1.0 ± 0.4 ml; HU 3.8 ± 0.3 ml; recovery 1.2 ± 0.5 ml). Although water intake decreased there was no reduction in total fluid intake when saline was available. Plasma volumes were reduced during HU compared to rats in a normal posture when only water was available to drink (control (n = 11) versus HU (n = 11): 4.0 ± 0.2 versus 3.4 ± 0.2 ml (100 g body weight)−1). When 0.9% saline was available in addition to water, plasma volumes after 24 h HU were not different from rats in a normal posture (control (n = 11) versus HU (n = 12): 4.3 ± 0.4 versus 4.3 ± 0.1 ml (100 g body weight)−1). Plasma aldosterone but not plasma renin activity was significantly elevated after 24 h HU. Central infusions of spironolactone blocked the increased intake of 1.8% saline that was associated with 24 h HU. Thus, HU results in an aldosterone-dependent sodium appetite and the ingestion of sodium may help maintain plasma volume.

The cardiovascular system of humans and animals is adapted to the force of gravity. This force creates a hydrostatic gradient, which must be overcome to prevent the pooling of blood in the lower extremities and to maintain the perfusion of tissue above heart level. During exposure to microgravity and during bed rest, this hydrostatic effect is eliminated or attenuated. Central shifts in fluids occur (Grigor'ev et al. 1979; Greenleaf, 1984; Rubin, 1988) and the body responds as though blood volume has increased. Diuresis and natriuresis ensue, accompanied by a reduction in water intake, culminating in a reduction in plasma volume (Grigor'ev et al. 1979; Harper & Lyles, 1988; Greenleaf, 1984; Leach et al. 1996). The decrease in plasma volume is believed to contribute to orthostatic intolerance observed upon return to normal gravity or upright posture (Chenault et al. 1992).

The hindlimb-unloaded (HU) rat is a model of microgravity and bed rest (Morey-Holton & Globus, 2002). In this rat model, the hindlimbs are elevated above the floor of the cage such that the weight of the animal is borne by the forelimbs. Blood volume is shifted to the head and thoracic cavity (Tipton et al. 1996). Diuresis and natriuresis follow and a reduction in plasma volume occurs (Deavers et al. 1980; Musachia et al. 1992; Martel et al. 1996). Attenuation of water intake (Steffen et al. 1984) and baroreflex control of sympathetic nerve activity (Moffitt et al. 1998) have also been reported. In addition to the cephalic pooling of body fluid, hypokinesia may also contribute to the diuresis and natriuresis associated with HU (Bouzeghrane et al. 1996; Zorbas et al. 1996).

In these studies we examined the behavioural component of body fluid regulation by measuring water ingestion and voluntary sodium intake during a brief (24 h) period of HU. Since the diuresis and natriuresis associated with HU occurs during the first 24 h (Deavers et al. 1980; Musachia et al. 1992; Martel et al. 1996), we chose to focus the study on this time period in order to more clearly determine how these early responses to HU would influence water and sodium intake. Based on Kaufman's observations (Kaufman, 1984; Toth et al. 1987) and previous studies that have demonstrated that HU produces cephalic pooling of body fluids followed by diuresis and natriuresis (Deavers et al. 1980; Tucker et al. 1987) it was hypothesized that both water intake and intake of sodium chloride solutions would be diminished during acute HU, contributing to the decrease in plasma volume. After observing that 24 h HU was associated with an increase in sodium intake, we tested the specifity of the sodium appetite by giving HU rats access to a potassium chloride solution and examined the effects of sodium availability on changes in plasma volume during 24 h HU. We also tested the roles of aldosterone and the renin–angiotensin system in the sodium appetite produced by 24 h HU by measuring plasma aldosterone and plasma renin activity during HU and by administering an aldosterone antagonist, spironolactone during 24 h HU.

Methods

Male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g at the beginning of the study were individually housed in 40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm Plexiglas cages designed for hindlimb unloading and measurement of fluid intake. Rats were housed in an AAALAC accredited animal facility under a 12: 12 h light: dark cycle at 25°C. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with guidelines of the Public Health Service, the American Physiological Society and the Society for Neuroscience. Purina rat diet and distilled water were available ad libitum except during specific periods as noted below. Depending on the protocol, some of the animals also had access to a sodium chloride solution (0.9 or 1.8%).

In order to address the role of restraint stress in this paradigm, the rats were all subjected to a training protocol in which they were HU for 1 h over 3 days. To accomplish HU, a harness was attached to the base of the tail and hooked to a swivel on a nylon line above the cage such that the animal was at an approximately 45 deg angle (Moffitt et al. 1998). The animal could move freely about the cage using its front paws.

Surgical procedures

Catheter implantation

Forty-five rats were instrumented with femoral venous and carotid arterial catheters for plasma volume measurements. Each rat was anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg kg−1i.p.) and the skin around the incision site was shaved and cleaned. Using aseptic technique, an incision was made and a blunt dissection performed to isolate the vessels from the surrounding tissue. The vessel was tied proximally and clamped. A small incision was made and a catheter was introduced into the vessel, advanced into the abdominal aorta or vena cava and secured in place with suture. Each catheter was constructed of PE 10 heat-melded to PE 50 tubing. The catheters were tunnelled subcutaneously and exteriorized between the scapulae. Each catheter was filled with heparinized saline and plugged with a 23 g obturator. An additional group of rats was implanted with only carotid artery catheters for withdrawing blood for plasma renin measurements. Each rat was anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg kg−1i.p.) and prepared as described above. Once the carotid artery was isolated and clamped a small incision was made, a Silastic-tipped PE 50 catheter was inserted into the vessel and advanced just into the descending aorta. These catheters were exteriorized between the scapulae. Each rat was allowed to recover for at least 3–5 days prior to being used in another protocol.

Osmotic minipump implantation

Thirty-seven rats were implanted with osmotic mini-pumps (Alzet model 2004, 0.25 μl h−1; Cupertino, CA, USA) for either intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) or subcutaneous (s.c.) infusions. Osmotic mini-pumps were filled with either spironolactone (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (400 μg ml−1) containing 1% alcohol or only the alcohol-containing vehicle (Francis et al. 2001). The pumps were incubated for at least 48 h in a 37°C water bath and weighed prior to implantation. Surgeries were performed using aseptic technique and the rats were anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg kg−1i.p.). For i.c.v. infusions, the pumps were connected to a piece of 23 gauge stainless steel tubing (Small Parts Miami Lakes, FL, USA), which was bent at a 90 deg angle, with polyethylene tubing. The free end of the 23 gauge tubing was placed in the left lateral ventricle using stereotaxic technique. A small hole was drilled in the skull at 1.0 mm posterior and 1.5 mm lateral to bregma (using the level skull technique, Paxinos & Watson, 1997). The cannula was put into the hole so that it extended 6 mm down into the brain from the surface of the skull and then it was cemented into place with dental acrylic and jeweller's screws. The osmotic pumps were then sutured into a small pocket made under the skin at the base of the neck. For s.c. infusions, the pumps were prepared and placed under the skin at the base of the neck just as they were implanted for the i.c.v. infusions.

Sodium and water intake

Rats were trained to the HU procedure as described above. Rats were randomly divided into five different groups. Distilled water, and rat chow was available to all the animals ad libitum. One group was given only distilled water to drink (n = 10). In a second group of rats 0.9% sodium chloride was available in addition to water (n = 11). Water intake and sodium chloride solution intake were monitored daily. Each cage was outfitted with calibrated tubes containing either water or a salt solution so that fluid intake could be measured to the nearest 0.1 ml. In addition calibrated centrifuge tubes were hung below the tubes containing distilled water or salt solution to collect any fluid that was lost due to leakage or spilling. Water and saline solution that was recovered in these tubes was subtracted from the total measured. Total fluid intake was determined by adding the amounts of water and saline solution that were ingested. Measurements were made at the same time each day.

At least 2 days following training, rats were hindlimb unloaded for 24 h. HU was accomplished in the same manner as training. Water and sodium chloride solution intakes were monitored over the 24 h. Rats were returned to normal posture following 24 h HU and water and sodium chloride solution intakes were monitored during a 24 h recovery period.

Because 0.9% NaCl may be palatable to the rats, we examined NaCl intake using a solution that is less palatable. To accomplish this, the identical testing protocol was repeated in a third group of rats using a 1.8% NaCl solution (n = 7). In order to test the specificity of the effects of HU on sodium intake, a fourth group was trained and suspended (HU) as previously described but had access to a 1.8% KCl and water rather than a NaCl solution (n = 6). Another group of rats was trained for HU and given 1.8% KCl and water to drink but was not suspended (n = 4).

Plasma volume measurements

Rats were trained for the HU protocol as above with 0.9% sodium chloride solution available in addition to distilled water. For this study the rats were instrumented with chronic indwelling catheters. The sodium chloride solution was withdrawn and rats were implanted with a carotid artery and femoral vein catheter. After 3 days recovery (during which the sodium chloride solution was not available (Lane et al. 1997), the 0.9% sodium chloride solution was returned to half the rats. The remainder of the animals had only water available, and served as controls.Half of the control group and half of the rats with 0.9% sodium chloride were then suspended for 24 h. Thus, there were four experimental groups: control posture, water only (n = 11); HU, water only (n = 11); control posture, 0.9% sodium chloride and water available (n = 11); and HU, 0.9% sodium chloride and water available (n = 12). At the end of this 24 h period, plasma volumes were measured using the Evans blue dye method as previously described (Campbell et al. 1958; Farjanel et al. 1997). Briefly, 25 μg of dye in 100 μl saline was injected via the femoral venous catheter. The catheter was flushed with 200 μl saline. After 5 min the arterial catheter was cleared of saline and a blood sample was drawn into a heparinized syringe. The HU rats remained suspended until the blood samples were drawn. The blood was centrifuged and plasma sample obtained. The dye content of the sample was determined spectrophotometrically at 610 nm and compared to a standard curve constructed using known amounts of Evans blue dye and plasma from donor rats. Plasma volume per 100 g body weight was calculated for statistical analysis.

Plasma renin activity and aldosterone assays

Rats were trained for HU as previously described. One group of the rats was suspended for 24 h (n = 9) while another group served as controls (n = 7). Both groups were given only water to drink since the ingestion of a sodium-containing solution may influence aldosterone and renin release. At the end of the 24 h period each rat was anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg kg−1i.p.) and immediately decapitated. A 2–4 ml volume of whole blood from each rat was collected in tubes containing EGTA and centrifuged for 10 min at 4 g in a refrigerated centrifuge. The plasma from each sample was removed and separated into two different samples. Plasma renin activity (PRA) was determined using a RIANEN angiotensin I 125I radioimmunoassay kit (DuPont NEN, Boston, MA, USA) designed to measure PRA by the quantification of generated angiotensin I. The assay sensitivity (defined as the concentration of hormone at 95%B/Bo) was 6.0 pg and the intra- and intercoefficients of variation averaged 8% and 10%, respectively. Serum (or plasma) aldosterone was measured using a Coat-A-Count solid-phase 125I radioimmunoassay kit from Diagnostic Products Corporation (Los Angeles, CA, USA). The assay sensitivity was 9 pg ml−1 and the intra- and intercoefficients of variation averaged 5.6% and 12.8%, respectively. All assays were performed at the RIA core at the University of Iowa. Control experiments indicate that the PRA levels obtained by anaesthesia and decapitation are not significantly different from samples obtained from plasma collected from unanaesthetized rats using catheters placed in the carotid artery (decapitation (n = 7) 4.19 ± 1.7 ng ml−1 h−1 angiotensin I versus catheter (n = 10) 3.18 ± 1.6 ng ml−1 h−1 angiotensin I, P > 0.05).

Spironolactone experiments

Based on the results of the study on plasma aldosterone, we tested the role of aldosterone on the salt appetite generated during 24 h HU by blocking aldosterone receptors with the antagonist spironolactone (Francis et al. 2001). Rats were randomly assigned to five groups: controls (n = 8); i.c.v. infused with vehicle (n = 8); i.c.v. infused with spironolactone (400 μg ml−1; n = 9); s.c. infused with vehicle (n = 7); s.c. infused with spironolactone (400 μg ml−1; n = 13). The four groups receiving i.c.v. or s.c. infusions were implanted with osmotic minipumps as described above. The fifth group did not receive osmotic minipumps and served as unoperated controls.

Each rat was individually housed in the Plexiglas cages for HU 3–4 days prior to receiving the minipumps and baseline water and 1.8% NaCl intakes were recorded. After receiving the minipumps the rats were allowed 7 days to recover from surgery and daily water and 1.8% NaCl intakes were recorded. During this period the rats were trained for HU after which they were suspended for 24 h as described above. Body weight was also measured daily during these experiments. At the end of the 24 h HU, the rats were deeply anaesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (100 mg kg−1i.p.) and the osmotic minipumps were removed and weighed to ensure that they worked properly. In addition, the rats with i.c.v. cannulae implants were given injections of Evans blue dye (2% w/v) through the cannulae to verify that the cannulae terminated in the lateral ventricle.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed by ANOVA. When appropriate, multiple comparisons of significant results were made using Student-Newman-Keuls tests. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05. The relationship between PRA and plasma aldosterone in HU and control posture rats was determined using a Pearson product moment correlation coefficient. In situations when data were not normally distributed or variance was non-homogeneous (spironolactone experiment) a natural log transformation was used. Statistical analyses were performed using commercially available software (SigmaStat, v. 2.03, Jandel Scientific). All data are presented as means ±s.e.m.

Results

Water and sodium chloride intake

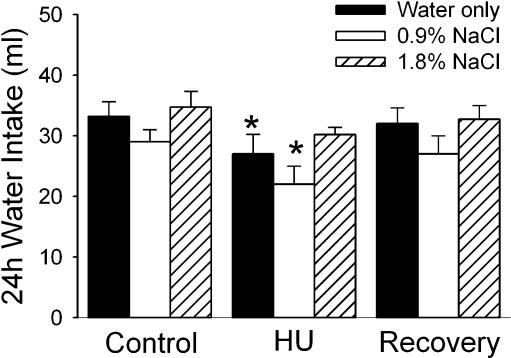

The water intake of the experimental groups is illustrated in Fig. 1. Rats offered only distilled water to drink exhibited a decrease in water intake during the 24 h of HU. Intakes returned to baseline levels during the 24 h recovery period following HU.

Figure 1. Water intake.

Water intake under control conditions, during 24 h hindlimb unloading (HU) and during 24 h following return to normal posture (Recovery) in rats with only water (filled columns, n = 10), water and 0.9% NaCl (open columns, n = 11) or water and 1.8% NaCl (hatched columns, n = 7) available to drink. Water intake was significantly attenuated during a 24 h period of HU compared to intakes in a 24 h control period before HU (Control) and 24 h following return to normal posture (Recovery) when only water was available to drink. When a 0.9% NaCl solution was available in addition to water (white columns, n = 11), water intake was significantly attenuated compared to pre- and post-HU intakes as well. While the same trend was apparent when a 1.8% NaCl solution was available (hatched columns, n = 7), intakes were not significantly lower during HU. *Significantly different from Control and Recovery values within the experimental group.

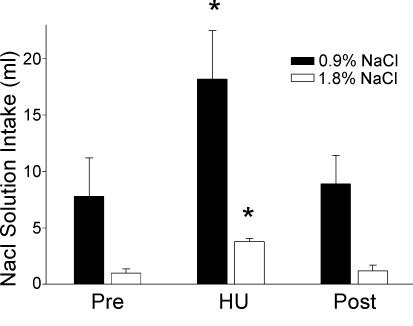

When 0.9% sodium chloride was offered in addition to distilled water, an intake of 7.8 ± 3.4 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride was observed in the control period prior to HU (Fig. 2). A significant increase in 0.9% sodium chloride intake was observed during the 24 h period during which the animals were suspended. The rats drank more than twice as much 0.9% sodium chloride (18.2 ± 4.3 ml) as during the control period (P < 0.05). Basal water intake was not significantly different from the intake of rats having only distilled water to drink (Fig. 1). Water intake, however, was again significantly reduced during the period of HU. Both water and sodium chloride intakes returned to normal values in the 24 h following return to normal posture.

Figure 2. NaCl solution intake.

Intake of a 0.9% NaCl (n = 11) and a 1.8% NaCl (n = 7) solution was significantly increased to more than two times the intake observed during a 24 h period before HU (Pre). Intakes returned to normal levels during the 24 h following return of the rat to a normal posture (Post). *Significantly different from Pre and Post values.

Baseline intake of 1.8% sodium chloride was 0.9 ± 0.4 ml in 24 h when a 1.8% sodium chloride solution was offered in addition to distilled water. However, during HU, intake increased significantly to 3.8 ± 0.3 ml in 24 h (Fig. 2; P < 0.05). Again, intakes returned to baseline values in the 24 h following return to normal posture. Water intakes were reduced in the presence of 1.8% sodium chloride but the reduction was not statistically significant (Fig. 1).

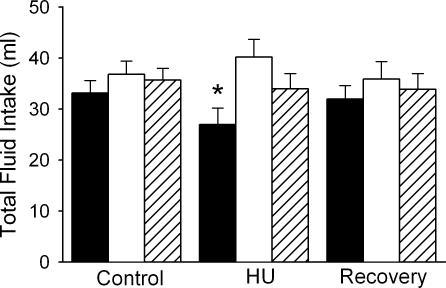

Examination of the total fluid volume ingested revealed that only rats allowed access to distilled water as their sole source of fluid decreased total fluid intake (Fig. 3). When sodium chloride solutions were available in addition to distilled water, fluid intake (ml water + ml sodium chloride solution) was not different from control during the 24 h HU or 24 h recovery period.

Figure 3. Total fluid intake.

Fluid intake was significantly reduced when water was the only liquid offered during 24 h HU (filled columns, n = 10). However, no significant change in fluid intake (ml water + ml NaCl solution) occurred when either 0.9% NaCl (open columns, n = 11) or 1.8% NaCl (hatched columns, n = 7) were available in addition to water. *Significantly different from Control and Recovery values.

The mean daily baseline intakes of 1.8% KCl were 1.2 ± 0.4 ml for the HU groups versus 1.5 ± 0.9 ml for the control group. During 24 h HU, the HU rats drank an average of 1.8 ± 1 ml of 1.8% KCl, while the controls drank an average of 1.3 ± 1 ml. HU did not significantly influence KCl intake (P > 0.05). The average daily baseline water intakes for the two groups were 33.7 ± 6 ml for the HU rats and 25.0 ± 3 for the controls. Water intake was decreased by 24 h HU to 21.0 ± 4 ml although the decrease was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The water intake for the controls during the testing period was 24.5 ± 2.5 ml.

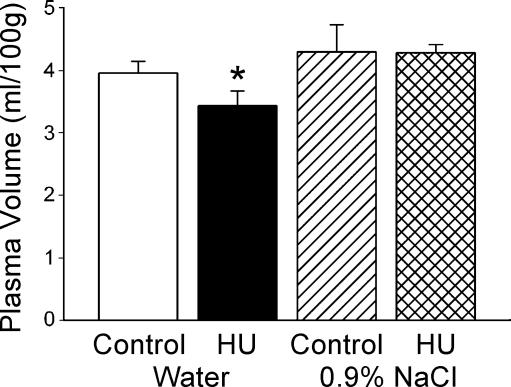

Plasma volume

HU resulted in a significant decrease in plasma volume in animals having distilled water alone available to drink Fig. 4). Plasma volume was reduced approximately 13% by the end of 24 h HU compared to the control group. There was no significant difference in plasma volume between animals in the control posture with or without 0.9% sodium chloride available. In contrast to animals with access to water alone, HU did not result in decreased plasma volume in rats that had also 0.9% sodium chloride available during HU. Consistent with the plasma volume measurements, rats in the control posture with water or with water and sodium chloride solution available, and HU rats with sodium chloride available showed little change in weight during the 24 h period (0.4 ± 1.9 g, −1.4 ± 1.4 g and 0.6 ± 2.6 g, respectively). However, HU rats with only water available to drink had a significant decrease in weight (−4.8 ± 2.1 g) during the 24 h of HU.

Figure 4. Plasma volume.

When water was the sole fluid available, plasma volume was significantly reduced following 24 h HU (filled column, n = 11) compared to control rats (open column, n = 11). However, when 0.9% NaCl was available in addition to water, plasma volume following HU (cross-hatched column, n = 12) was not different from the control value (hatched column, n = 11). *Significantly different from all other values.

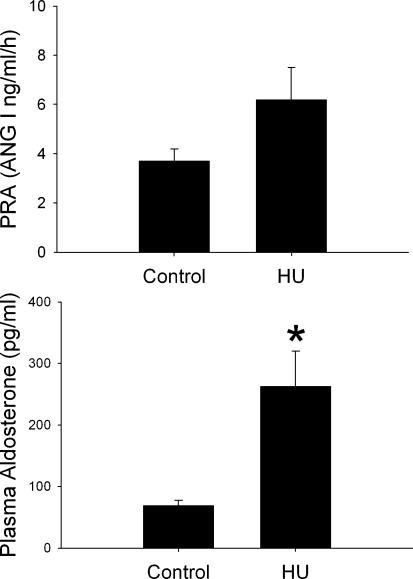

Plasma renin activity and aldosterone

HU was associated with a significant increase in plasma aldosterone compared to the control posture rats (Fig. 5, P < 0.05). HU did not significantly affect PRA (Fig. 5, P > 0.05). In the control posture rats, plasma aldosterone was positively correlated with PRA (r2= 0.693). However, aldosterone was not positively correlated with PRA in the HU rats (r2=−0.37).

Figure 5. Plasma renin activity and plasma aldosterone.

Plasma renin activity (PRA) and plasma aldosterone in rats HU for 24 h (n = 9) and normal posture controls (n = 8). Both groups had access only to water to drink. PRA was not significantly affected by 24 h HU (top). Plasma aldosterone, on the other hand, was significantly increased by 24 h HU (bottom). *Significantly different from Control.

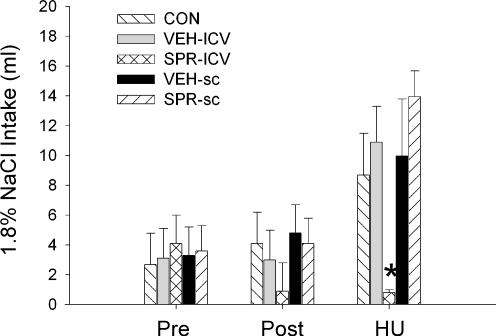

Spironolactone experiments

There were no significant differences in any group between pre-surgical and post-surgical baseline daily water or 1.8% NaCl intakes. During 24 h HU, water intake was significantly decreased across all of the groups (Table 1). Thus, spironolactone administered either i.c.v. or s.c. did not significantly affect the decrease in water intake associated with HU.

Table 1.

Water intake (ml) before surgery (Pre), following surgery (Post) and during 24 h hindlimb unloading (HU)

| Control (n = 8) | i.c.v.–Veh (n = 6) | i.c.v.–SPR (n = 9) | s.c.–Veh (n = 7) | s.c.–SPR (n = 13) | Treatment (n = 43) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 30.7 ± 1.3 | 30.6 ± 1.5 | 31.0 ± 1.8 | 30.5 ± 2.0 | 30.7 ± 1.2 | 30.7 ± 0.6 |

| Post | 28.2 ± 1.0 | 31.4 ± 1.6 | 32.8 ± 1.6 | 31.2 ± 2.3 | 30.0 ± 1.2 | 30.7 ± 0.6 |

| HU | 20.1 ± 3.8 | 30.3 ± 2.6 | 28.1 ± 2.6 | 27.1 ± 3.9 | 24.2 ± 2.1 | 26.0 ± 0.6* |

Veh, vehicle; SPR, spironolactone. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA indicated no significant interaction or main effect for group. There was a significant main effect for treatments (Ftreat(2, 76) = 18.85, P < 0.05). Follow-up analysis indicated that the amount of water drunk during HU was significantly lower than during the two baseline periods

P < 0.05, Student-Newman-Keuls test. All values are means and s.e.m. except for the combined means that have the standard error for the least-square mean from the ANOVA.

As in the previous experiments, HU resulted in increased intake of 1.8% NaCl compared to their baseline daily intakes (Fig. 6). This response was not altered by i.c.v. or s.c. vehicle or by s.c. administration of spironolactone. However, the group receiving i.c.v.

Figure 6. Effect of spironolactone on NaCl intake.

Mean intakes of 1.8% NaCl in untreated rats (CON, n = 8), rats given intracerebral ventricular (i.c.v.) infusions of vehicle (VEH-ICV, n = 6), rats infused i.c.v. with spironolactone (SPR-ICV, n = 9), rats infused subcutaneously (s.c.) with vehicle (VEH-SC, n = 7) and rats infused s.c. with spironolactone (SPR-SC, n = 13) prior to surgery to implant the minipumps (Pre), following implantation of the minipumps (Post) and during 24 h hindlimb unloading (HU). Statistical analysis indicated no differences among the groups during either of the baseline periods (Pre and Post) and that all of the groups except the rats infused i.c.v. with spironolactone significantly increased their 1.8% intake during 24 h HU. *Significantly different from all other groups (P < 0.05).

spironolactone failed to show the increased intake of 1.8% NaCl during HU (Fig. 6). The average amount of 1.8% NaCl ingested by the i.c.v. spironolactone group during HU was significantly less than all of the other groups. All five groups lost weight during HU and the decreases in their body weights were not significantly different among the groups.

Discussion

Overall, the results from these studies indicate that 24 h HU is associated with a decrease in water intake but an increased intake of NaCl-containing solutions. Furthermore, the increased NaCl intake appears to prevent the significant decrease in plasma volume produced by 24 h HU. We also observed that in 24 h HU rats with access only to water, circulating aldosterone is significantly increased without a significant increase in plasma renin activity. The results also demonstrate that the sodium appetite associated with 24 h HU is blocked by central administration of an aldosterone antagonist.

HU and water intake

In the present studies, water intake was decreased during 24 h HU although this decrease was not statistically significant in every group. Water intake is not commonly measured during HU and the results of such studies have been variable. Decreases in water intake have been observed in HU rats and mice (Deavers et al. 1980; Steffen et al. 1984). However, other investigators using the rat model have observed a non-significant trend toward a decrease in water intake (McCombs et al. 1996) or no reduction in water intake during HU (Martel et al. 1996). Bouzeghrane et al. (1996) did not observe changes in water intake in either HU rats or tethered non-suspended controls. Important differences exist between these investigations and the present study. Variation in the angle of HU might contribute to the differences in the results as could the age or weights of the animals (Morey-Holton & Globus, 2002).

Hypokinesia has also been shown to influence water intake and body fluid balance (Zorbas et al. 1996). In rats subjected to 90 days of hypokinesia water intake significantly decreased while fluid and electrolyte excretion significantly increased (Zorbas et al. 1996). The decrease in water intake during hypokinesia is also associated with decreased food intake (Zorbas et al. 1996). Some investigators have observed a decrease in food intake during HU (Steffen et al. 1984; McCombs et al. 1996) believed to be associated with a reduced energy expenditure that accompanies the limited use of the hindlimbs (Cintron et al. 1990; Stein & Gaprindashvili, 1994). Thus, hypokinesia could contribute to the decrease in water intake related to a decrease in energy expenditure as well as produce the diruesis and natriuresis that is associated with HU although urine output was not measured in the present study. Nevertheless, this hypothesis seems unlikely given the fact that the rats are clearly able to drink, and they maintain their fluid intake when they are given NaCl solutions.

The changes in drinking behaviour observed in HU rats in this study are consistent with the changes observed in humans during bed rest (Grigor'ev & Egorov, 1992) and exposure to microgravity (Grigor'ev et al. 1979; Grigor'ev & Egorov, 1992; Smith et al. 1997). Common to both space flight and bed rest is a reduction in water intake (Grigor'ev et al. 1992; Smith et al. 1997). This change in behaviour contributes to the reduction of body fluid volume.

HU and NaCl intake

Contrary to our initial hypothesis that water and sodium intake both would be suppressed by HU, intake of NaCl-containing solutions increased during 24 h HU. This increased intake was not observed when the rats were offered a KCl-containing solution with water. This suggests that the increase was specific for NaCl. Total fluid intake was significantly reduced from baseline by 24 h HU when the rats had access only to water. When the rats also had access to a NaCl-containing solution, their total fluid intake during 24 h HU was not different from baseline. These results indicate that 24 h HU is associated with a significant increase in the consumption of NaCl-containing solutions that prevents a significant decrease in total fluid intake during 24 h HU. Toth et al. (1987) demonstrated that stretch of the aortocaval junction attenuated sodium intake induced by volume depletion with a hyperoncotic colloid and to treatment with deoxycorticosterone acetate. Since it has been reported that in this model rats experience an increase in central venous pressure during HU (Musachia et al. 1992; Martel et al. 1996), we hypothesized that similar mechanisms might be activated that would suppress NaCl ingestion. However, we observed a marked increase in intake of sodium chloride solutions. It could be that a natriuresis associated with restraint stress or hypokinesia (Bouzeghrane et al. 1996; Zorbas et al. 1996) stimulated the increased sodium consumption. Hypokinesia-induced diuresis and natriuresis may have prevented significant cephalic pooling of body fluids and prevented the activation of cardiac afferents that would have suppressed the ingestion of the NaCl-containing solutions.

The possibility that the sodium appetite is produced by stress seems unlikely because previous studies have shown that in the rat restraint stress either significantly reduces (Bensi et al. 1997) or does not affect sodium appetite (Howell et al. 1999). Furthermore, studies have shown that some forms of stress produce a decrease in sodium excretion (Koepke & Dibona, 1985; Veelken et al. 1996). Thus the increase in drinking of NaCl solutions associated with 24 h HU is not likely to be a stress response.

We conducted additional experiments in an attempt to determine the mechanism responsible for the increased sodium intake associated with 24 h HU. Aldosterone is thought to contribute to the production of sodium appetite with the renin–angiotensin system (Sakai et al. 1986; Epstein, 1990) and circulating angiotensin has been demonstrated to be important in stimulating sodium appetite (Thunhorst & Fitts, 1994). In the current study, PRA and plasma aldosterone were measured in rats after 24 h of HU with only water to drink. Aldosterone was significantly increased in the HU animals while we failed to find a significant change in PRA. This result is consistent with previous studies measuring plasma renin activity in HU rats that show that plasma renin activity is reduced during chronic HU (Tucker et al. 1987; McCombs et al. 1996). Aldosterone has been found to be elevated during HU in one study (McCombs et al. 1996). Perhaps the natriuresis observed during HU results in hyponatraemia that promotes aldosterone production.

Based on our measurements of aldosterone, we hypothesized that increased plasma aldosterone may contribute to the increased sodium intake that we observed during HU. To test this hypothesis we administered an aldosterone antagonist centrally and peripherally during HU. This protocol was selected based on the results of a previous study that demonstrated selective actions of spironolactone in the central nervous system (Francis et al. 2001). The results show that central aldosterone receptor blockade with spironolactone significantly decreased sodium intake during 24 h HU. These results suggest that the sodium appetite produced by 24 h HU is mediated by centrally acting aldosterone. However, aldosterone appears to be acting independently of the peripheral renin–angiotensin system.

Adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) also promotes the release of aldosterone. ACTH release might be expected due to the stress of HU and in fact ACTH has been demonstrated to be elevated early in HU (Thomason & Booth, 1990). Additionally, ACTH has been demonstrated to produce a sodium appetite following several days of administration (Blaine et al. 1975; Weisinger et al. 1978; Blair-West et al. 1989). The long time course usually required for the production of sodium appetite in this model would make ACTH an unlikely candidate. The mechanism that produced the increase in plasma aldosterone associated with 24 h HU remains to be determined.

A decrease in plasma volume of approximately 13% was apparent in HU rats that had only distilled water available to drink. This is consistent with previous literature (Martel et al. 1996). Presumably, the increase in central venous pressure results in a withdrawal of renal sympathetic nerve activity and decrease in vasopressin secretion (Kaczmarczyk et al. 1983; DiBona & Kopp, 1997; Grindstaff et al. 2000) thus promoting the excretion of sodium and water. Reduction in water intake would also contribute to the reduction in body fluid volume. Kaufman (1990) has also suggested that atrial stretch leads to atrial natriuretic factor release that promotes shunting of fluid from the vascular space into the lymphatic system to reduce vascular volume. Additionally, hypokinesia may also contribute to the decrease in plasma volume (Zorbas et al. 1996).

In this experiment, HU rats ingesting a sodium solution maintained plasma volume. Thus, it is possible that rats given NaCl solutions to drink during HU may be less susceptible to orthostatic intolerance if reduced plasma volume is one of its major contributing factors (Convertino, 1996). Previous studies suggest that increased salt intake or salt loading can reduce orthostatic intolerance in humans following space flight (Bungo et al. 1985) and improve orthostatic tolerance in patients with orthostatic-related syncope (El Sayed & Hainsworth, 1996; Mtinangi & Hainsworth, 1998). A recent study by Bayorh et al. 2000) demonstrated that placing rats on a high sodium diet significantly affected the changes in baroreflex function produced by 7 days of HU. Their data show that HU rats on a 8% NaCl diet failed to show a rightward shift in the baroreflex control of heart rate (Bayorh et al. 2000). Thus salt loading may be an effective countermeasure for some of the effects of cardiovascular deconditioning.

The HU rat has emerged as one of the major animal models used for land-based studies of the possible effects of microgravity associated with space flight (Morey-Holton & Globus, 2002). Similar to microgravity and bed rest, HU is reported to produce a shift of body fluids to the head and thorax resulting in increases in central venous pressure (Martel et al. 1996; McCombs et al. 1996). This increase in central blood volume is sensed by cardiac atrial baroreceptors which mediate the diuresis and natriuresis observed during the early phases of HU (Deavers et al. 1980; Tucker et al. 1987; Martel et al. 1996; McCombs et al. 1996). The resulting reduction in plasma volume contributes to the return of central venous pressure to normal levels between 12 and 24 h later (Martel et al. 1996). This reduction in plasma volume is believed to contribute to the development of cardiovascular deconditioning observed following HU (Martel et al. 1996). In addition to cephalic shifts in body fluid, hypokinesia may also contribute to changes in body fluid balance produced by HU. Bouzeghrane et al. (1996) showed that many of the changes in body fluid balance that are associated with HU may be the results of stress or hypokinesia related to connecting the rats to the suspension system without changing their posture. These findings may challenge the validity of the HU rat model since the cephalic fluid shift that is normally observed in humans (Grigor'ev et al. 1979; Greenleaf, 1984; Harper & Lyles, 1988; Leach et al. 1996) may not be the primary cause of the changes in body fluid homeostasis associated with HU.

The control of body fluid balance is complex, requiring the central integration of neural and humoral inputs related to volume, pressure and osmolality. We had expected to find that the HU rat exhibited coordinated behavioural responses that were consistent with the reduction of body fluid volume, namely decreased water and sodium intake. Rather, we observed that 24 h HU is associated with an aldosterone-dependent increase in sodium intake despite the fact that water intake is reduced. This increased sodium intake produced a normal total fluid intake that apparently kept the HU rats from reducing their plasma volume. It could be that opposing systems, those contributing to reduction of body fluid through diuresis, natriuresis, and the reduction of water intake and those promoting the maintenance of body fluid through ingestion of sodium, may be activated simultaneously. Alternatively, the sodium appetite could be the result of the diuresis and natriuresis although water intake remains suppressed. Whether these changes in body fluid balance are related to cephalic pooling associated with suspension during HU or produced by hypokinesia remains to be determined. Future experiments will examine changes in water and sodium intake in chronic HU rats since it is a more clinically relevant model for cardiovascular deconditioning and determine whether or not sodium loading is an effective countermeasure for the chronic effects of cardiovascular deconditioning.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association (AHA-97-30246 to M.J.S and AHA-98-4100X to J.A.M), the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 DK57822 to M.J.S.; NIH R01 HL55306 to E.m.H.; NIH K02 HL03620 to J.T.C) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NAGW-4991 to E.m.H.). The authors would like to acknowledge the technical assistance of Jennifer Cornelius and Donna Farley and the University of Iowa RIA core. M.J.S. died June 2, 2001.

References

- Bayorh MA, Socci RR, Wang M, Emmett N, Theirry-Palmer M. Salt-loading and simulated microgravity on baroreflex responsiveness in rats. J Gravit Physiol. 2000;7:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensi N, Bertzzi M, Armario A, Guana HF. Chronic immobilization stress reduces sodium intake and renal excretion in rats. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaine EH, Corvelli MD, Denton DA, Nelson JF, Shulkes AA. The role of ACTH and adrenal glucocorticoids in the salt appetite of wild rabbits (Oryctolagus cunicilus (L) Endocrinology. 1975;97:793–801. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-4-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair-West JR, Denton DA, McBurnie M, Tarjan E, Weisinger RS. Influence of steroid hormones on sodium appetite of Balb/c mice. Appetite. 1989;24:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(95)80002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzeghrane F, Fagette S, Somody L, Allevaed A-M, Gharib C, Gauquelin G. Restraint vs. hindlimb suspension on fluid and electrolyte balance in rats. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:1993–2001. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.6.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungo MW, Charles JB, Johnson PC. Cardiovascular deconditioning during space flight and the use of saline as a countermeasure to orthostatic intolerance. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1985;56:985–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell TT, Frohman B, Reeve EB. A simple rapid and accurate method of extracting T-1824 from plasma adapted to the routine measurement of blood. J Lab Clin Med. 1958;52:7686–7677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenault VM, Morris M, Lynch CD, Maultsby SJ, Hutchins PM. Neurohumoral responses to isohemic hypervolemia: a model for weightlessness. Physiologist. 1992;35:S109–S110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintron NM, Lane HW, Leach CS. Metabolic consequences of fluid shifts induced by microgravity. Physiologist. 1990;33:S16–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convertino VA. Clinical aspects of the control of plasma volume at microgravity and during return to one gravity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:S45–S52. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199610000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deavers DR, Musicchia XJ, Meininger GA. Model for antiorthostatic hypokinesia: head-down tilt effect on water and salt excretion. J Appl Physiol. 1980;49:576–582. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBona GF, Kopp UC. Neural control of renal function. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:75–197. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Sayed H, Hainsworth R. Salt supplement increases plasma volume and orthostatic tolerance in patients with unexplained syncope. Heart. 1996;75:134–140. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AN. Prospectus: Thirst and salt appetite. Handbook Behav Neurobiol. 1990;10:489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Farjanel J, Denis C, Chartard JC. An accurate method of plasma volume measurement by direct analysis of Evans blue spectra in plasma without dye extraction: origins of albumin-space variations during maximal exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1997;75:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s004210050129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis J, Wiess RM, Wei S-G, Johnson AK, Beltz TG, Zimmerman K, Felder RB. Central mineralocortioid receptor blockade improves volume regulation and reduces sympathetic drive in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Cir Physiol. 2001;281:H2241–H2251. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf JE. Physiological responses to bed rest and fluid immersion in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1984;57:619–633. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigor'ev AI, Dorokhova BR, Kozyrevskaya GI, Natochin YV, Arzamazov GS, Noskov VB. Effect of duration of bed rest on water and mineral metabolism and kidney function. Human Physiol. 1979;5:483–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigor'ev AI, Egorov AD. Physiological adaptations of main human body systems during and after spaceflights. Adv Space Biol Med. 1992;2:43–82. doi: 10.1016/s1569-2574(08)60017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindstaff RR, Grindstaff RJ, Cunningham JT. Effects of atrial stretch on vasopressin and oxytocin supraoptic neurons in the rat. Am J Physiol Reg Int Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R1605–R1615. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.6.R1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper CM, Lyles YM. Physiology and complications of bed rest. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:1047–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb04375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LA, Harris RBS, Clarke C, Youngblood BD, Ryan DH, Gilbertson TA. The effects of restraint stress on intake of preferred and nonpreferred solutions in rodents. Physiol Behav. 1999;65:697–704. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarczyk G, Christe W, Mohnhaupt R, Reinhardt HW. An attempt to quantitate the contribution of antidiuretic hormone to the diuresis of the left atrial distention in conscious dogs. Pflugers Arch. 1983;396:101–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00615512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman S. Role of right atrial receptors in the control of drinking in the rat. J Physiol. 1984;349:389–396. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman S. Renal and hormonal responses to prolonged atrial stretch. Am J Physiol Comp Reg Int. 1990;258:R1286–R1290. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.5.R1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepke JP, DiBona GF. Central beta-adrenergic receptors mediate renal nerve activity during stress in conscious spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1985;7:350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JR, Louise S, Lee P, Fitts DA. Induced preference or conditioned taste aversion for sodium chloride in rats with chronic bile duct ligation. Physiol Behav. 1997;63:537–543. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach CS, Alfrey CP, Suki WN, Leonard JI, Rambaut PC, Inners LD, Smith SM, Lane HW, Kraus JM. Regulation of body fluid compartments during short term spaceflight. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:105–116. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombs GB, Ott CE, Jackson BA. Effects of thoracic volume expansion on cardiorenal functions in the conscious rat. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1996;67:1086–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel E, Champeroux P, Lacolley P, Richard S, Safer M, Cuche J-L. Central hypovolemia in the conscious rat: a model of cardiovascular deconditioning. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:1390–1396. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.4.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt JA, Foley CM, Schadt JC, Laughlin MH, Hasser EM. Attenuated baroreflex control of sympathetic nerve activity after cardovascular deconditioning. Am J Physiol Comp Reg Int. 1998;274:R1397–R1405. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.5.r1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey-Holton ER, Globus RK. Hindlimb unloading rodent model: techinal aspects. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1367–1377. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00969.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mtinangi BL, Hainsworth R. Early effects of oral salt on plasma volume, orthostatic tolerance and baroreceptors sensitivity in patients with syncope. Clin Auton Res. 1998;8:231–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02267786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musachia XJ, Steffen JM, Dombrowski J. Rat cardiovascular responses to whole body suspension: head-down and non-head-down tilt. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:1504–1509. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.4.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 3. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin M. The physiology of bed rest. Am J Nursing. 1988;88:50–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai RR, Nicolaidis S, Epstein AN. Salt appetite is suppressed by interference with angiotensin II and aldosterone. Am J Physiol Comp Reg Int. 1986;251:R762–R768. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.4.R762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Krauhs JM, Leach CS. Regulation of body fluid volume and electrolyte concentrations in spaceflight. Adv Space Biol Med. 1997;6:123–165. doi: 10.1016/s1569-2574(08)60081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen JM, Robb R, Dombrowsk MJ, Musacchia XJ, Sonnenfeld G. A suspension model for hypokinetic/hypodynamic and antiorthostatic responses in the mouse. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1984;55:612–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein TP, Gaprindashvili T. Spaceflight and protein metabolism, with special reference to humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:806S–819S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.806S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason DB, Booth FW. Atrophy of the soleus muscle by hindlimb unweighting. J Appl Physiol. 1990;68:1–12. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thunhorst RL, Fitts DA. Peripheral angiotensin causes salt appetite in rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R171–R177. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.1.R171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tipton CM, Greenleaf JE, Jackson CGR. Neuroendocrine and immune system responses with spaceflights. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:988–998. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199608000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth E, Stelfox J, Kaufman S. Cardiac control of salt appetite. Am J Physiol Comp Int Reg. 1987;252:R925–R929. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.5.R925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker BJ, Mundy CA, Ziegler MG, Baylis C, Blantz RC. Head-down tilt and restraint on renal function and glomerular dynamics in the rat. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:505–513. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.2.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veelken R, Hilgers KF, Stetter A, Sibert H-G, Schmieder RE, Mann JFE. Nerve-mediated antidiuresis and antinaturesis after air-jet stress is modulated by angiotensin II. Hypertension. 1996;28:825–832. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisinger RS, Denton DA, McKinley MJ, Nelson JF. ACTH induced sodium appetite in the rat. Pharm Biochem Behav. 1978;8:339–342. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(78)90067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorbas YG, Verentsov GE, Bobylev VR, Yarshenko YN, Federenko YF. Electrolyte metabolic changes in rats during and after exposure to hypokinesia. Physiol Chem Phys Med NMR. 1996;28:267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]