Abstract

Recently a novel cGMP-activated Ca2+-dependent Cl−channel has been described in rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. In the present work we have investigated the actions of calmodulin (CaM) on single channel cGMP-activated Ca2+-dependent Cl−current (ICl(cGMP,Ca)) in inside-out patches. When 1 μm CaM was applied to the intracellular surface of inside-out patches bathed with 10 μm cGMP and 100 nm [Ca2+]i there was approximately a 10-fold increase in channel open probability (NPo). This effect of CaM was not observed with lower [Ca2+]i and 100 nm [Ca2+]i with 1 μm CaM did not activate Cl−channels in the absence of cGMP. The unitary conductance, reversal potential and mean open time of the single-channel currents were similar in the absence or presence of CaM. With 10 μm cGMP and 100 nm [Ca2+]i the relationship between NPo and CaM concentration was well fitted by the Hill equation yielding an equilibrium constant for CaM of about 1.9 nm and a Hill coefficient of 1.7. With 1 μm CaM (+10 μm cGMP) the relationship between [Ca2+]i and NPo was also fitted by the Hill equation which yielded an apparent equilibrium constant of 74 nm [Ca2+]i and a Hill coefficient of 4.8. When [Ca2+]i was increased from 300 nm to 1 μm there was a decrease in NPo. The potentiating effect of CaM was markedly reduced by the selective CaM binding peptide Trp (5 nm) but not by the Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) inhibitor autocamtide II related inhibitory peptide (AIP). It is concluded that CaM potentiates the activity of single channel ICl(cGMP,Ca) by increasing the probability of channel opening via a CaMKII-independent mechanism.

It is well established that Ca2+-activated Cl−channels are expressed in the sarcolemma of smooth muscle cells and that this conductance is involved in producing smooth muscle contraction (e.g. see reviews by Large & Wang, 1996 and Large et al. 2002). However, recently a novel Ca2+-dependent Cl−conductance was described in rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells (Matchkov et al. 2004; Piper & Large, 2004).

A key difference between these two Ca2+ dependent Cl− conductances is the absolute requirement for cGMP for activation of the Cl−channels in rat mesenteric arteries whereas the ‘classical’ Ca2+-activated Cl−conductance (ICl(Ca)), e.g. in the rabbit pulmonary artery, does not need the presence of cGMP at the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane for activation of the Cl−channel, which can readily be activated by application of Ca2+ ions to the internal surface of the membrane (Piper & Large, 2003). In contrast in rat mesenteric myocytes intracellular Ca2+ ions did not activate the Cl−channels in the absence of cGMP but increased the channel open probability (NPo) in the presence of cGMP (Piper & Large, 2004). Moreover cGMP did activate Cl−channel opening in the absence of Ca2+i in some patches. Hence we termed this conductance a cGMP-activated Ca2+-dependent Cl−current or ICl(cGMP,Ca). Moreover there are several other differences in the properties of ICl(cGMP,Ca) and ICl(Ca) including the value of the unitary conductance, channel kinetics, voltage dependence and pharmacology (Piper & Large, 2004; Matchkov et al. 2004).

In our previous study of ICl(cGMP,Ca) in inside-out patches of rat mesenteric artery myocytes we observed a very steep relationship between the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and NPo in the presence of a constant concentration of cGMP (Piper & Large, 2004). Thus the threshold concentration of [Ca2+]i to increase NPo was approximately 50 nm and the maximal effect was produced with 100 nm [Ca2+]i (Piper & Large, 2004). This yielded a Hill slope of approximately 8, which prompted us to consider the involvement of Ca2+ binding proteins, specifically calmodulin (CaM), in the regulation of ICl(cGMP,Ca) by Ca2+ ions. In the present work we demonstrate that CaM produces marked potentiation of ICl(cGMP,Ca) by increasing NPo with no change in the unitary conductance or mean open channel lifetime. Moreover this effect is not mediated by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII).

Methods

Preparation of mesenteric artery smooth muscle myocytes

All experiments were performed on freshly dispersed rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Male or female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g were stunned and killed by cervical dislocation, as approved under Schedule 1 of the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, and the mesenteric vascular bed excised. Single smooth muscle cells were isolated as previously described (Piper & Large, 2004).

Solutions

In order to record single ICl(cGMP,Ca) currents from inside-out patches the pipette solution contained (mm): N-methyl-d-glucamine chloride (NMDG-Cl; prepared by equimolar addition of NMDG and HCl), 126; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 10; Hepes, 10; pH adjusted to 7.2 with NMDG or HCl as appropriate. The external solution (intracellular surface of patch) contained (mm): NMDG-Cl, 126; MgCl2, 1.2; EGTA, 0.1; MgATP, 1; pH adjusted to 7.2 with NMDG or HCl as appropriate. Both external and pipette solutions contained TEA (10 mm) and 4-AP (10 mm). CaCl2 (6.5, 41, 67 or 88 μm) was added to obtain free [Ca2+] of 10, 100, 300 or 1000 nm (calculated using Eqcal for Windows, Biosoft Cambridge, UK).

Papain, collagenase 1A, bovine serum albumin, dithiothreitol, Hepes, NMDG, Mg-ATP, EGTA, cGMP, TEA and 4-aminopyridine were all supplied by Sigma-Aldrich. Autocamtide II related inhibitory peptide (AIP) was supplied by Calbiochem. Human recombinant calmodulin, Trp and Tyr peptides were a kind gift from Dr Katalin Török (St George's Hospital Medical School, London, UK).

Electrophysiological recording

All experiments were carried out on inside-out patches at room temperature (20–25°C). For details of recording conditions and analysis see Piper & Large (2004). Briefly, current records were low pass filtered off line at 1 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz. Analysis of channel openings and closings to provide a channel events list was carried out using Clampfit 9 (Axon Instruments), using a 50% threshold crossing analysis as previously described (Piper & Large, 2004). As channel activity was often intermittent and appeared at least in some patches to occur in discrete bursts, particularly with low (< 10 nm) CaM concentrations or in the absence of CaM, NPo was calculated over recording lengths of between 3 and 4 min. In the case of the comparison of NPo in the absence and presence of the CaM binding peptides Trp and Tyr, NPo was calculated for the 60 s before the peptides were applied and again for 60 s 4 min later. As there was variability in NPo between patches, wherever possible experiments were designed such that the comparison of NPo with, e.g., different [Ca2+]i was carried out with the same group of patches using paired t tests.

The relationship between NPo and calmodulin concentration or [Ca2+]i was fitted by the Hill equation as previously described (Piper & Large, 2004). In order to generate log open time distributions channel, events were grouped into 1 ms bins and the resultant distributions were fitted by exponential functions using Clampfit 9 software.

Results

Effect of CaM on single cGMP-activated Ca2+-dependent channel currents recorded in inside-out patches

In control conditions single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channels were activated at −50 mV by bathing the cytoplasmic surface of inside-out patches with 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 10 μm cGMP (Piper & Large, 2004). When 1 μm CaM was applied there was a marked potentiation of NPo (e.g. Fig. 1A) from a mean control value of 0.20 ± 0.10 to 1.66 ± 0.26 (n = 7, P < 0.01) in the presence of 1 μm CaM.

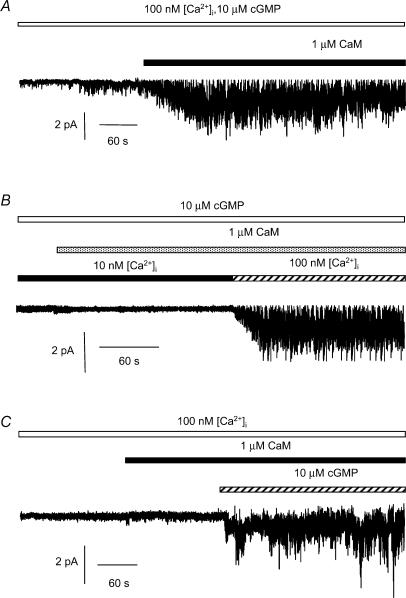

Figure 1. Effect of CaM on single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents recorded in inside-out patches.

A, single-channel currents recorded at a patch potential of −50 mV with 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 10 μm cGMP (open bar) in the absence and presence of CaM (1 μm, filled bar). B, single-channel currents recorded at −50 mV in the presence of 10 μm cGMP (open bar). [Ca2+]i was either 10 nm (filled bar) or 100 nm (hatched bar). CaM (1 μm) was added as indicated by the shaded bar. C, single-channel currents recorded at −50 mV with 100 nm [Ca2+]i (open bar), 1 μm CaM (filled bar) and 10 μm cGMP (hatched bar). In A–C up to three channels were present in each patch and in this and all subsequent figures the inward currents are represented as downward deflections.

The potentiating effect of CaM on single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents was dependent on the presence of Ca2+ ions (Fig. 1B). Similar to our previous data (Piper & Large, 2004) single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents with a low mean NPo of 0.05 ± 0.02 were recorded in the presence of 10 μm cGMP and 10 nm [Ca2+]i in 3 of 5 patches. When 1 μm CaM was added to the internal solution there was no change in NPo (Fig. 1B, mean NPo was 0.05 ± 0.04 in 3 of 5 patches) but when [Ca2+]i was raised to 100 nm, there was a significant increase in NPo to 1.70 ± 0.49 in all five patches (P < 0.05, Fig. 1B).

Single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents were not activated by either 100 nm [Ca2+]i alone or a mixture of 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 1 μm CaM (e.g. Fig. 1C, 6 patches). However, when 10 μm cGMP was applied to the same patches the mean NPo was greatly increased (0.59 ± 0.13, n = 6; Fig. 1C).

These data confirm that ICl(cGMP,Ca) channels require cGMP for activation and also that CaM potentiates activity in a Ca2+-dependent manner.

Properties of single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents recorded in the presence of 1 μm CaM

In the next series of experiments we investigated the properties of the Cl−channels recorded in the presence of 1 μm CaM. Figure 2A shows an expanded trace of single-channel currents recorded from an inside-out patch at a patch potential of −100 mV exposed to 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 10 μm cGMP in the absence (Fig. 2Aa) and presence of 1 μm CaM (Fig. 2Ab). Three separate current levels could be discerned in each of these traces (denoted by the dotted lines) as reported previously (Piper & Large, 2004), and transitions between the closed level to each of the three current levels could be seen, suggesting that they were not multiple channel openings. It is clear from Fig. 2Ab that in the presence of 1 μm CaM the amplitude of the single-channel currents were not altered and this conclusion is confirmed in the all points histograms shown in Fig. 2Ba and b. The peak at 0 pA amplitude in Fig. 2Ba represents the closed current level, while there were three further peaks representing open channel states. In the presence of 1 μm CaM the peaks representing both closed and open current levels were unchanged (Fig. 2Bb).

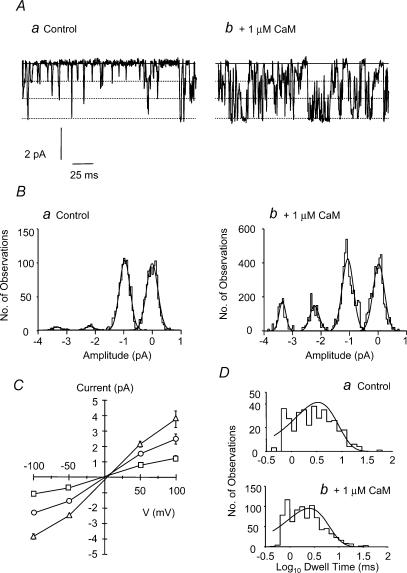

Figure 2. Properties of single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents in the absence and presence of CaM (1 μm).

A, single-channel currents recorded at a patch potential of −100 mV with 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 10 μm cGMP in the absence (a) and presence (b) of 1 μm CaM. Continuous lines represent the closed channel current level while the dotted lines denote the three conductance levels. B, amplitude histograms derived from 60 s sections of the above traces in the absence (a) and presence (b) of 1 μm CaM. Data were fitted by the sum of four Gaussian curves. C, mean single-channel I–V relationships for both subconductance (12 pS, □ 27 pS, ▵) and full-conductance openings (43 pS, □) of single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channels in the presence of 10 μm cGMP, 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 1 μm CaM. Data are the mean ± s.e.m., n = 17–20. D, plots of log10 dwell time for the smallest subconductance level derived from 60-s periods in the absence (a) and presence (b) of 1 μm CaM. Data were fitted by a single exponential function (see text for mean values).

Figure 2C shows the mean I–V curves from 17 to 20 inside-out patches in the presence of 100 nm [Ca2+]i, 10 μm cGMP and 1 μm CaM for each conductance level. The slope conductances estimated from the linear portion of the I–V relationships were 12.4 ± 0.5 pS (n = 20), 27.5 ± 0.8 pS (n = 19) and 43.2 ± 1.3 pS (n = 17), respectively, which were similar to the values of slope conductance for each current level recorded in the absence of CaM in our previous study (15 ± 2 pS (n = 6), 34 ± 3 pS (n = 5) and 43 ± 9 pS (n = 4); Piper & Large, 2004).

To determine if Ca2+–CaM had any effect on the kinetics of single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents the single-channel open time distributions were studied. Figure 2Da and b shows data for transitions to the smallest sublevel although data from both the intermediate and full-conductance levels were similar (data not shown). The log open time distribution for the inside-out patch shown in Fig. 2Aa is shown in Fig. 2Da. The distribution could be fitted by a single exponential function to give a mean open time of 3.3 ms at −100 mV (mean 4.1 ± 0.5 ms, n = 7) while in the presence of 1 μm CaM the mean open time was 2.5 ms (Fig. 2Db) mean 4.0 ± 0.6 ms, n = 7, P = 0.89).

These data show that modulation of single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents by Ca2+–CaM is not via an increase in the unitary conductance, or an increase in the single channel mean open time but by an increase in the open channel probability. These data also show that Ca2+–CaM does not activate any additional conductances.

Relationship between CaM concentration and NPo for single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents

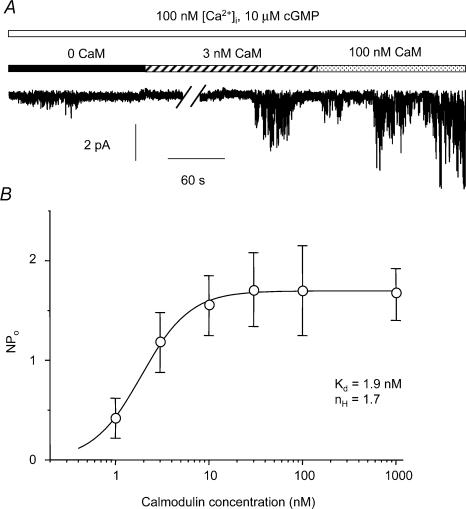

To determine the relationship between CaM concentration and NPo for single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents inside-out patches were exposed to a range of CaM concentrations from 1 nm to 1 μm in the presence of 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 10 μm cGMP. The increase in NPo produced by Ca2+–CaM was concentration-dependent. Figure 3A shows a trace of single-channel currents in the absence of CaM (NPo was 0.17), and in the presence of 3 nm and 100 nm CaM where NPo was 0.59 and 3.45, respectively. The mean data from five to seven patches are shown in Fig. 3B where NPo was plotted against CaM concentration. The resultant relationship could be well fitted by the Hill equation, giving a Kd (concentration to produce 50% of the maximum NPo) of 1.9 nm and a Hill coefficient (nH) of 1.7.

Figure 3. Concentration dependence of the potentiating effect of CaM on single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents.

A, single-channel currents recorded at −50 mV with 10 μm cGMP and 100 nm [Ca2+]i (open bar) in the absence of CaM (filled bar) and with 3 nm (hatched bar) or 100 nm (shaded bar) CaM. There were at least 3 channels present in the patch. B, plot of NPo versus CaM concentration at a patch potential of −50 mV. Data were fitted by the Hill equation to give the apparent dissociation constant (Kd) and the Hill coefficient (nH). Data are the mean ± s.e.m., n = 5–7.

Effect of varying [Ca2+]i in the presence of 1 μm CaM on single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents

In order to study further the relationship between channel activation, [Ca2+]i and calmodulin, a series of experiments were carried out in the presence of 1 μm CaM (+10 μm cGMP) and varying [Ca2+]i. Figure 4Aa shows a trace of current recorded from an inside-out patch in the presence of 10 μm cGMP and 1 μm CaM when [Ca2+]i was raised from 50 nm to 300 nm. There was a significant increase in NPo from 0.21 ± 0.10 (n = 9) with 50 nm [Ca2+]i to 1.99 ± 0.43 (n = 6, P < 0.05) with 300 nm [Ca2+]i,which can be seen in more detail in Fig. 4Ab and Ac. Interestingly, when [Ca2+]i was increased to 1 μm, there was an significant reduction in NPo. Figure 4B shows an experiment from a patch in which [Ca2+]i was increased from 300 nm to 1 μm and there was a marked reduction in NPo. The mean NPo with 300 nm [Ca2+]i was 2.20 ± 0.50 (n = 5) while with 1 μm [Ca2+]i the mean NPo was 1.32 ± 0.52 (n = 5, P < 0.05).

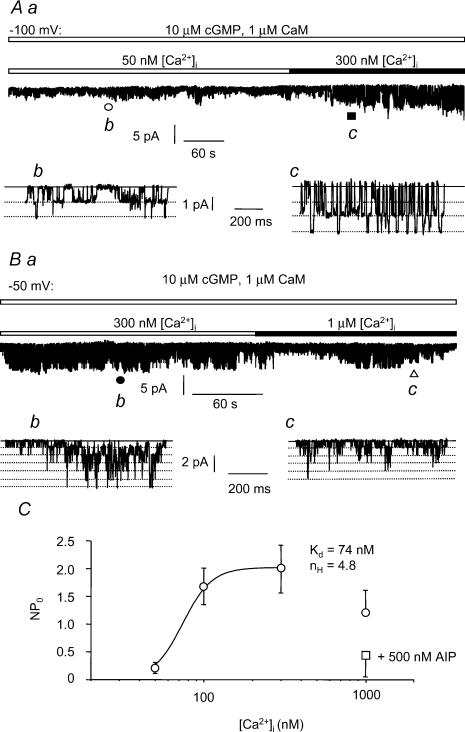

Figure 4. Effect of varying [Ca2+]i in the presence of 1 μm CaM on single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents.

Aa, single channel currents recorded at −50 mV with 10 μm cGMP and 1 μm CaM in the presence of 50 nm [Ca2+]i (open bar) and 300 nm [Ca2+]i (filled bar). Ab and c are 1 s sections of trace from Aa as indicated by the open circle and filled square, respectively, on an expanded time scale. The continuous lines represent the closed channel current level while the dotted lines denote the sub- and full-conductance levels. Ba, trace of single channel currents recorded at −100 mV with 10 μm cGMP and 1 μm CaM in the presence of 100 nm [Ca2+]i (open bar) and 1 μm [Ca2+]i (filled bar). Bb and c are 1 s sections of trace from Ba as indicated by the filled circle and open triangle, respectively, on an expanded time scale. The continuous lines represent the closed channel current level while the dotted lines denote the sub- and full-conductance levels. N.B. this patch contained at least two channels. C, plot of NPo versus [Ca2+]i at a patch potential of −50 mV in the presence of 10 μm cGMP and 1 μm CaM (□) and 10 μm cGMP, 1 μm CaM and 500 nm AIP (□). Data were fitted by the Hill equation to give the apparent dissociation constant (Kd) and the Hill coefficient (nH). Data are the mean ± s.e.m., n = 5–7.

The mean data from these experiments is shown in Fig. 4C where NPo is plotted against [Ca2+]i. The data up to 300 nm [Ca2+]i were fitted by the Hill equation to give an apparent Kd of 74 nm and a Hill coefficient of 4.8. As NPo was decreased with 1 μm [Ca2+]i it is likely that this may be an underestimation of the true Kd since it was not possible to determine the maximum NPo.

Effect of CaM binding peptides on Ca2+–CaM-mediated increase in NPo of single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channels

CaM-binding peptides derived from the amino acid sequence of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) have been shown to bind CaM (Török & Trentham, 1994) and inhibit the activity of CaM-activated MLCK in vitro (Török et al. 1998) suggesting that they may be useful inhibitors of Ca2+–CaM-dependent intracellular processes. The 17 amino acid peptide Trp binds to free CaM with picomolar affinity (Török & Trentham, 1994). Figure 5A shows a trace of single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents recorded with 100 nm [Ca2+]i, 10 μm cGMP and 1 μm calmodulin in the absence and presence of 5 nm Trp peptide. After 4 min in the presence of 5 nm Trp peptide the single channel NPo was significantly reduced (Fig. 5B). This was due to a specific interaction between Ca2+–CaM and Trp peptide as the closely related Tyr peptide, which differs by only one amino acid residue and binds CaM with more than 1000-fold less affinity (Török & Trentham, 1994), had no effect on single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents (Fig. 5B). After 4 min in the presence of 5 nm Tyr peptide the mean single channel NPo was unchanged (1.51 ± 0.65 with Tyr compared to the control mean NPo of 1.47 ± 0.57, n = 9, P = 0.96).

Figure 5. Effect of CaM-binding peptides and the CaMKII inhibitor AIP on CaM-mediated potentiation of single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel currents.

A, single-channel currents in the presence of 10 μm cGMP, 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 1 μm CaM in the absence and presence of 5 nm Trp peptide. The continuous lines represent the closed channel current level while the dotted lines denote the sub- and full-conductance levels. B, bar chart to show single-channel NPo in the presence of 10 μm cGMP, 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 1 μm CaM in the absence (open bar) and presence of 5 nm Trp peptide (filled bar), in the absence (hatched bar) and presence of 5 nm Tyr peptide (horizontally hatched bar) and in the absence (vertically hatched bar) and presence of 500 nm autocamtide II related inhibitory peptide (AIP, shaded bar). Data are the mean ± s.e.m., n = 9, **P < 0.01.

Role of Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II

We investigated whether the effects of Ca2+–CaM were mediated by Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII). For this purpose we used the selective CaMKII inhibitor autocamtide II-related inhibitory peptide (AIP) which inhibits CaMKII with an equilibrium constant of about 40 nm (Ishida et al. 1995; Bhatt et al. 2000). In the first series of experiments we explored whether the inhibitory action of 1 μm [Ca2+]i and 1 μm CaM is mediated by CaMKII. It is shown in Fig. 4C that in the presence of 500 nm AIP 1 μm [Ca2+]i significantly reduced NPo to 0.43 ± 0.27 (n = 5, P < 0.05), compared to 1.20 ± 0.50 (n = 5) with 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 1 μm CaM. This reduction with 1 μm [Ca2+]i is similar to the value in the absence of AIP, suggesting that activation of CaMKII does not mediate the reduction in single channel activity with high [Ca2+]i.

In addition the potentiating effect of Ca2+–CaM was not altered by 500 nm AIP (Fig. 5B). In these experiments it was shown that NPo with 10 μm cGMP, 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 1 μm CaM is similar in the absence and presence of 500 nm AIP.

These data indicate that Ca2+–CaM produces an increase in single ICl(cGMP,Ca) channel Po via a direct action, possibly on the channel protein itself, and not via the activation of CaMKII.

Discussion

The present work demonstrates that CaM markedly potentiates ICl(cGMP,Ca) in inside-out patches from rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. Even though 1 μm CaM increased NPo by approximately tenfold in the presence of 10 μm cGMP and 100 nm [Ca2+]i, a combination of 100 nm [Ca2+]i and 1 μm CaM in the absence of cGMP did not evoke channel opening. In contrast cGMP in the absence of Ca2+–CaM did evoke channel opening in some patches. Therefore the presence of intracellular cGMP was essential for chloride channel activation, which could occur in the absence of Ca2+ and calmodulin in some cells but Ca2+–CaM was necessary for full channel activation.

Physiological relevance of Ca2+–CaM modulation of ICl(cGMP,Ca)

Experiments on the relationship between CaM concentration and NPo in the presence of 10 μm cGMP and 100 nm [Ca2+]i revealed that the potentiating effect of CaM was potent with an estimated equilibrium constant of about 2 nm. Since the intracellular CaM concentration may be 1–10 μm (Saimi & Kung, 2002) with an estimated cGMP concentration in smooth muscle of 2–4 μm (Matchkov et al. 2004) it is likely that the effects of CaM described in this report may be very important physiologically. The resting [Ca2+]i in smooth muscle is approximately 50–100 nm in which the potentiating effects of CaM are marked. Moreover increases in [Ca2+]i above this value lead to further activation of ICl(cGMP,Ca), which will produce depolarization and opening of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and subsequent contraction of vascular smooth muscle (see Large & Wang, 1996). However at 1 μm [Ca2+]i the current was inhibited compared to 300 nm [Ca2+]i, which represents a self-limiting inhibitory mechanism that may help to prevent over-activation of this excitatory mechanism.

Molecular mechanism of potentiating action of Ca2+–CaM on ICl(cGMP,Ca)

In the presence of 1 μm CaM (+10 μm cGMP) the relationship between NPo and [Ca2+]i yielded an apparent equilibrium constant of 74 nm, which is similar to the value in the absence of added CaM (about 80 nm, Piper & Large, 2004). This result indicates that the apparent affinity and therefore the mechanism of the potentiating effect of Ca2+ is similar in the absence and presence of added CaM, which suggests that CaM remains attached to some channels in excised inside-out patches. The Hill coefficient of 4.8 for Ca2+ binding in the presence of 1 μm CaM is close to the number of Ca2+ binding sites (4) on the CaM molecule. Moreover, the Hill coefficient derived from the relationship between NPo and CaM was 2 and these two latter factors may account for the high Hill coefficient (7.1) obtained from the plot between NPo and [Ca2+]i obtained in the absence of added CaM (Piper & Large, 2004). A simple explanation is that two CaM molecules, each with four Ca2+ ions, bind to the channel to produce a potentiating effect. In the absence of added CaM the Hill coefficient for Ca2+ binding close to 8 may represent Ca2+ binding to CaM molecules already bound to the channels. In the present study single-channel analysis revealed that the unitary conductance values and the channel mean open times were the same in the absence and presence of CaM indicating that Ca2+–CaM simply increases the probability of channel opening. Also the potentiating effect of CaM was not reduced by the CaMKII inhibitor AIP, indicating that this effect of CaM on ICl(cGMP,Ca) was not mediated by CaMKII but maybe by binding to the channel directly. It is possible that CaMKII may regulate this channel but the potentiating effect of CaM observed in the present experiments is not mediated by CaMKII. Interestingly, evidence has been provided to suggest that CAMKII may be involved in the inactivation of classical ICl(Ca) in equine tracheal myocytes (Wang & Kotlikoff, 1997) and in rabbit pulmonary and coronary smooth muscle cells (Greenwood et al. 2001).

Previously it has been demonstrated that cGMP activates ICl(cGMP,Ca) via cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG, Piper & Large, 2004; Matchkov et al. 2004) and the present work illustrates that a Ca2+–CaM mechanism greatly potentiates channel activation. We propose that PKG-mediated phosphorylation of the channel interacts synergistically with a Ca2+–CaM mechanism to produce activation, probably mediated by two distinct sites on the channel protein, although more extensive studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Many different types of ion channel with differing ionic selectivities and diverse gating mechanisms are regulated by Ca2+–CaM (see review by Saimi & Kung, 2002). Many channels possess specific Ca2+–CaM binding sites and CaM may even act as a constituent of others. Thus the binding of Ca2+–CaM causes inhibition of cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel currents, inactivation of NMDA receptor currents and either activation or inhibition of transient receptor potential (TRP) channel currents (see Saimi & Kung, 2002). On the other hand CaM is a constituent of SK potassium channels and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Ca2+ binding to CaM present in SK channels causes channel activation while in the case of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels Ca2+ binding to constituent CaM is responsible for Ca2+-dependent inactivation (Saimi & Kung, 2002). With regard to anion channels and therefore relevant to the present study Ca2+–CaM has been shown to regulate anion conductances in T84 cells (Worrell & Frizzell, 1991), human biliary cells (Schlenker & Fitz, 1996) and human CLC-3 channels (Huang et al. 2001). However, in these cases Ca2+–CaM was shown to be acting via CaMKII and in the present study we have shown that the action of Ca2+–CaM on ICl(cGMP,Ca) currents is independent of CaMKII activation.

In summary rat mesenteric artery myocytes possess a Cl− channel which is activated by cGMP via protein kinase G-mediated phosphorylation (Piper & Large, 2004) and is regulated by Ca2+–CaM via a CaMKII-independent process. This represents a novel anion channel activation/regulation mechanism.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Katalin Török for her helpful discussions both during these experiments and in the preparation of this manuscript. This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust.

References

- Bhatt HS, Conner BP, Prasanna G, Yorio T, Easom RA. Dependence of insulin secretion from permeabilized pancreatic β-cells on the activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1655–1663. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood IA, Ledoux J, Leblanc N. Differential regulation of Ca2+-activated Cl−currents in rabbit arterial and portal vein smooth muscle cells by Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase. J Physiol. 2001;534:395–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Di Liu JA, Robinson NC, Musch MW, Kaetzel MA, Nelson DJ. Regulation of human CLC-3 channels by multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20093–20100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida A, Kameshita I, Okuno S, Kitani T, Fujisawa H. A novel highly specific and potent inhibitor of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1995;212:806–812. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA, Greenwood IA, Piper AS. Recent advances on the properties and role of Ca2+-activated chloride currents in smooth muscle. In: Fuller CA, editor. Current Topics in Membranes. Vol. 53. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl−conductance in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;268:C435–C454. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchkov V, Aalkjaer C, Nilsson H. A cyclic GMP-dependent calcium-activated chloride current in smooth-muscle cells from rat mesenteric resistance arteries. J General Physiol. 2004;123:121–134. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper AS, Large WA. Single Ca2+-activated Cl−channels in rabbit isolated pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2003;547:181–196. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper AS, Large WA. Single cGMP-activated Ca2+-dependent Cl−channels in rat mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2004;555:397–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.057646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saimi Y, Kung C. Calmodulin as an ion channel subunit. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:289–311. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.100301.111649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker T, Fitz JG. Ca2+-activated C1−channels in a human biliary cell line: regulation by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G304–G310. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.2.G304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Török K, Cowley DJ, Brandmeier BD, Howell S, Aiken A, Trentham DR. Inhibition of calmodulin-activated smooth-muscle myosin light-chain kinase by calmodulin-binding peptides and fluorescent (phosphodiesterase-activating) calmodulin derivatives. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6188–6198. doi: 10.1021/bi972773e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Török K, Trentham DR. Mechanism of 2-chloro-(ɛ-amino-Lys75)-[6-[4-(N,N-diethyamino) phenyl]-1,3,5-triazin-4-yl]calmodulin interactions with smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase and derived peptides. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12807–12020. doi: 10.1021/bi00209a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y-X, Kotlikoff MI. Inactivation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14918–14923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worrell RT, Frizzell RA. CaMKII mediates stimulation of chloride conductance by calcium in T84 cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:C877–C882. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.4.C877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]