Abstract

To investigate mechanisms underlying the transmission of spontaneous Ca2+ signals in the bladder, changes in intracellular concentrations of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) were visualized in isolated detrusor smooth muscle bundles of the guinea-pig urinary bladder loaded with a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, fura-PE3 or fluo-4. Spontaneous increases in [Ca2+]i (Ca2+ transients) preferentially originated along the boundary of muscle bundles and then spread to the other boundary (Ca2+ waves). The synchronicity of Ca2+ waves across the bundles was disrupted by 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (18β-GA, 40 μm), carbenoxolone (30 μm) or 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate (2-APB, 50–100 μm), while CPA (10 μm), ryanodine (100 μm), xestospongin C (3 μm) and U-73122 (10 μm) had no effect. Intracellular recordings using two independent microelectrodes demonstrated that 2-APB (100 μm) blocked electrical coupling between detrusor smooth muscle cells. Nifedipine (10 μm) but not nominal Ca2+-free solution diminished the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves before preventing their generation. Staining for c-kit identified interstitial cells (IC) located along both boundaries of muscle bundles. IC were also scattered amongst smooth muscle cells and were more dominantly distributed in connective tissue between muscle bundles. IC generated nifedipine-resistant spontaneous Ca2+ transients, which occurred independently of those of smooth muscles. In conclusion, the propagation of Ca2+ transients in the bladder appears to be exclusively mediated by the spread of action potentials through gap junctions being facilitated by the regenerative nature of L-type Ca2+ channels, without significant contribution of intracellular Ca2+ stores. IC in the bladder may modulate the transmission of Ca2+ transients originating from smooth muscle cells rather than being the pacemaker of spontaneous activity.

Electrophysiological recordings have demonstrated that both intact and isolated detrusor smooth muscle cells of the bladder exhibit spontaneous action potentials (Montgomery & Fry, 1992; Hashitani et al. 2000). Since both spontaneous contractions and action potentials are readily blocked by L-type Ca2+ channel blockers, a critical role of these channels in the generation of spontaneous excitation has been suggested (Herrera et al. 2000; Hashitani & Brading, 2003). Simultaneous recordings of electrical and mechanical activity and changes in the concentration of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) in isolated muscle bundles clearly demonstrated that action potentials and associated Ca2+ transients result in contractions, and thus confirm that spontaneous excitation in the bladder results from action potentials (Hashitani et al. 2004). However, the mechanisms underlying the generation of this excitation in the bladder are still to be elucidated.

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) are now considered to play a key role in pacemaking and signal transmission in gastrointestinal tissues (Sanders, 1996; Hirst & Ward, 2003). Interstitial cells (IC) have also been identified in spontaneously active urinary tract smooth muscle, either by their immunoreactivity for c-kit, a specific marker for ICC, or through morphological criteria (Klemm et al. 1999; Sergeant et al. 2000; McCloskey & Gurney, 2002; Pezzone et al. 2003). In the urethra, isolated IC spontaneously discharge electrical events which are very similar to those recorded from intact smooth muscle preparations, suggesting that IC may be pacemaking the smooth muscle (Hashitani et al. 1996; Sergeant et al. 2001).

In the bladder, IC are found preferentially located on the boundary of muscle bundles from where spontaneous Ca2+ transients originate, suggesting that they may be crucial in generating spontaneous excitation (McCloskey & Gurney, 2002). However, there are several dissimilarities between the properties of spontaneous excitation in the bladder and those in gastrointestinal and urethral smooth muscle in which ICC or IC are likely to act as the pacemaker. First, isolated detrusor smooth muscles are capable of generating spontaneous action potentials, which are very similar to those recorded from multicellular preparations (Montgomery & Fry, 1992). Conversely, isolated ICC or IC, but not smooth muscle cells taken from gastrointestinal tissues or the urethra, are spontaneously active, although small populations of smooth muscle cells are also capable of exhibiting spontaneous activity (Farrugia, 1999; Sergeant et al. 2000; Ward et al. 2000). Second, regardless of their varied sensitivity to L-type Ca2+ channel blockers (Hashitani et al. 1996; Suzuki & Hirst, 1999; Yoneda et al. 2002), slow waves are readily blocked by chemicals which disrupt the function of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Hashitani et al. 1996; Van Helden et al. 2000; Fukuta et al. 2002; Yoneda et al. 2002). Underlying currents recorded from isolated ICC or IC are also highly sensitive to those chemicals, indicating that Ca2+ handling by intracellular Ca2+ stores is crucial in generating slow waves (Ward et al. 2000; Sergeant et al. 2001). On the other hand, spontaneous action potentials in the bladder were readily blocked by Ca2+ channel blockers but not by chemicals that disrupt intracellular Ca2+ stores (Hashitani & Brading, 2003). Furthermore, unlike smooth muscles in the gastrointestinal tissues or the urethra, which need to generate peristalsis or to maintain sustained tone, the bladder spends the majority of its time collecting urine and needs to maintain a low intraluminal pressure, and thus coordinated activity is undesirable during the filling phase. Neuronal signals are used to empty urine, and smooth muscle cells are densely innervated (Gabella, 1990). Therefore, while IC are indeed present in the bladder, their physiological role may not be identical to that of ICC or IC in the gastrointestinal tissues or the urethra.

Irrespective of whether spontaneous excitations originate from IC or smooth muscle cells, the signals in multicellular preparations require intact gap junctions to spread to neighbouring cells. Evidence is accumulating for the presence of gap junctions in bladders taken from several animals, including humans (Hashitani et al. 2001; Neuhaus et al. 2002; John et al. 2003). Recently, increased connexin43-mediated intercellular communications in a rat model of bladder overactivity has been reported, and the role of gap junctions in the pathophysiology of the ‘overactive bladder’ is now implicated (Haefliger et al. 2002; Christ et al. 2003). In the guinea-pig bladder, the blockade of gap junctions inhibited electrical coupling between detrusor smooth muscles and prevented dye communication, indicating a critical role of gap junctions in the signal transmission of the bladder (Hashitani et al. 2001). However, whether or not the propagation of spontaneous excitation in the bladder is exclusively mediated by the spread of action potentials via gap junctions remains to be established.

In the present study, the distribution of IC in the bladder was investigated using immunohistochemistry to label c-kit, a known specific marker of ICC. Attempts were also made to visualize Ca2+ signals from IC in preparations loaded with a Ca2+ indicator, fluo-4. Ca2+ waves across detrusor smooth muscle bundles were visualized in preparations loaded with a Ca2+ indicator, fura-PE3, and the effects of gap junction blockers, inhibitors of intracellular Ca2+ stores and Ca2+ entry were examined. Possible roles of IC and gap junctions in the generation and propagation of spontaneous excitation in the bladder are discussed.

Methods

General

The procedures described have been approved by the animal experimentation ethics committee at Nagoya City University Medical School. Male guinea-pigs weighing 200–500 g, were killed by a blow to the head followed by cervical dislocation. The urinary bladder was removed, and its ventral wall was opened longitudinally from the top of the dome to the bladder neck. The mucosal layer, connective tissues and several smooth muscle layers were then removed, leaving an underlying single layer of smooth muscle bundles attached to the serosal layer. A serosal sheet, which contained a single bundle of smooth muscle, 1–2 mm long and 0.2–0.5 mm wide was then prepared as previously described (Hashitani et al. 2001).

Immunohistochemistry

To identify cells expressing c-kit immunoreactivity, preparations which contained a few muscle bundles were incubated for 1 h in physiological saline containing rat monoclonal antibodies raised against the c-kit protein (ACK-2, diluted 1: 250, Cymbus Biotechnology Ltd, Hants, UK). The tissue was washed and then incubated for another 1 h in anti-rat IgG antibody labelled with a fluorescent marker (IgG-Alexa Fluor 488, diluted 1: 250, Molecular Probes, OR, USA). After washing with physiological saline, the preparations were observed using either a confocal laser microscopy (LSM5 PASCAL, Zeiss) or a conventional fluorescence microscope (IX70, Olympus).

Intracellular calcium measurements

For measurements of changes in the concentration of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i), bladder preparations were pinned out on a block of Sylgard plate (silicone elastomer, Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, MI, USA) which had a window of some 1 mm × 3 mm in the centre. The Sylgard block was turned over and then was placed at the bottom of the recording chamber so that the preparation faced a cover glass. After 30 min incubation with warmed (35°C) physiological saline, spontaneous muscle movements of the tissues were visually detected, and then the preparations were loaded with fluorescent dye, fura-PE3, by incubation in low-Ca2+ physiological saline (Ca2+, 1 mm) containing 10 μm fura-PE3 AM (Calbiochem-Novabiochem Ltd, San Diego, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. After loading, preparations were superfused with dye-free, warmed (35°C) physiological saline at a constant flow (about 2 ml min−1) for 30 min.

Preparations, loaded with fura-PE3, were viewed under either an oil-immersion objective (UPlanApo 40, Olympus) or air objective (UPlanApo 20, Olympus), and were alternately illuminated with ultraviolet light, wavelengths 340 and 380 nm, alternating at a frequency of higher than 40 Hz. The ratio of the emission fluorescence (R340/380) in a rectangular window was measured through a barrier filter of 510 nm (sampling interval 35–70 ms), using a micro photoluminescence measurement system (ARGUS/HiSCA, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan).

For visualizing Ca2+ signals from IC, preparations similar to those used for fura-PE3 experiments were incubated in nominally Ca2+-free solution containing 5 μm fluo-4 AM (FluoroPure™. grade special packaging, Molecular Probes, OR, USA) for 45 min at room temperature. Following incubation, the preparations were superfused with dye-free, warmed (35°C) physiological saline at a constant flow (about 2 ml min−1) for 30 min.

Preparations, loaded with fluo-4, were viewed under a water-immersion objective (UPlanApo 60, Olympus) and were illuminated at 495 nm. To identify unstained IC in the preparations, Nomarski optics was used (Hanani et al. 1999). The fluorescence emission in a desired size of rectangular window was measured through a barrier filter above 515 nm (sampling interval 145–325 ms), using a micro photoluminescence measurement system (ARGUS/HiSCA, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan), and relative changes in [Ca2+]i were expressed as the ratio (F/F0) of the fluorescence generated by an event (F) against baseline (F0).

Microelectrode recordings

Individual bladder smooth muscle cells were impaled with glass capillary microelectrodes, filled with 0.5 m KCl (tip resistance, 120–250 MΩ). Membrane potential changes were recorded using a high input impedance amplifier (Axoclamp-2 A, Axon Instruments, Inc., Union City, CA, USA), and displayed on a cathode-ray oscilloscope (SS-9622, Iwatsu, Tokyo, Japan). After low-pass filtering (cut-off frequency, 1 kHz), membrane potential changes were digitized using a DigiData 1200 interface (Axon Instruments, Inc.) and stored on a personal computer for later analysis.

In experiments in which electrical coupling between detrusor smooth muscle cells was examined, the preparation was impaled with two independent microelectrodes and the distance and location of two electrodes were estimated with an inverted microscope. After detecting synchronous action potentials from both electrodes, one electrode was used to inject current and the other was used to record resultant electrotonic potentials.

Solutions

The composition of physiological saline was (mm): NaCl, 120; KCl, 4.7; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 2.5; NaHCO3, 15.5; KH2PO4, 1.2 and glucose, 11.5. The solution was bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, and pH was 7.2–7.3. Low-Ca2+ or nominally Ca2+-free solution was prepared either by reducing or omitting CaCl2.

Drugs used were 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborate (2-APB), ryanodine, U-73122 and xestospongin C (from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Ltd, San Diego, CA, USA), carbenoxolone, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (18β-GA) and nifedipine (from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Nifedipine was dissolved in 100% ethanol, 2-APB, CPA, 18β-GA, ryanodine, U-73122 and xestospongin C were dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). The final concentration of these solvents in the physiological saline did not exceed 1: 1000.

Measured values were expressed as means ± standard deviation (s.d.). Statistical significance was tested using two-sided Student's t test, and probabilities of less than 5% were considered significant.

Results

Distribution of interstitial cells in the bladder

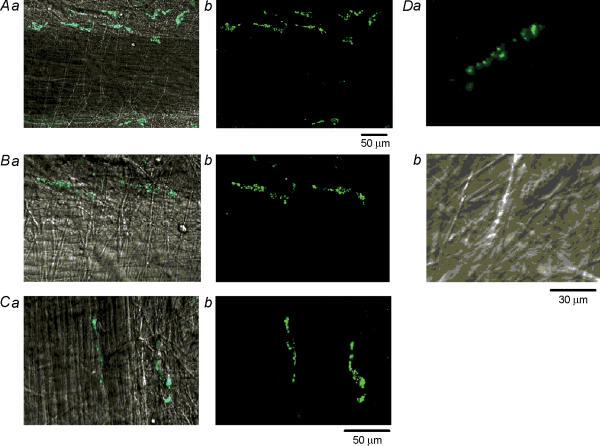

Consistent with a previous study (McCloskey & Gurney, 2002), IC which expressed immunoreactivity for c-kit, were abundantly distributed in the bladder preparations and ran parallel with the smooth muscle bundles (Fig. 1Aa and b). IC had spindle-shaped cell bodies, some 80 μm in length and less than 10 μm in width. Based on their location, IC in the bladder could be divided into three subpopulations. IC were found adjacent to the boundary of muscle bundles (boundary IC, Fig. 1Ba and b). IC were also scattered amongst smooth muscle cells within muscle bundles (intramuscular IC, Fig. 1Ca and b). In addition, IC were more dominantly distributed in connective tissues between muscle bundles (interbundle IC, Fig. 1Ca and b).

Figure 1. Distribution of interstitial cells in the guinea-pig bladder.

a, fluorescent images of interstitial cells (IC) stained using ACK2 antibody against c-kit labelled with Alexa 488 to allow visualization of IC (spindle-shaped cells) in the bladder of the guinea-pig. b, the same images superimposed on the plane images of smooth muscle bundles. A, IC are shown to distribute in parallel with a muscle bundle. B, a pair of IC having spindle-shaped cell bodies, some 80 μm in length and less than 10 μm in width are shown located adjacent to the muscle bundle (boundary IC). C, shows an IC penetrating between smooth muscle cells (intramuscular IC) and another located in the connective tissue (interbundle IC). Da, an interbundle IC expressing spotty fluorescence. Db, the IC had a spindle shaped cell body and numerous small dimples on the surface membrane. The scale bar at the bottom of Ab refers to both panels in A. The scale bar at the bottom of Cb refers to panels in B and C. The scale bar at the bottom of Db refers to both panels in D.

Using a water-immersion 60 × objective and Nomarski optics, attempts were also made to establish morphological criteria for IC. IC which had been identified by their immunoreactivity for c-kit generally expressed spotty fluorescence (Fig. 1Da). They were characterized by their spindle-shaped cell bodies, and typically had numerous small dimples with a diameter of about one micrometre on the surface (Fig. 1Db), suggesting that the small dimples preferentially expressed c-kit immunoreactivity.

Asynchronous Ca2+ waves in the bladder

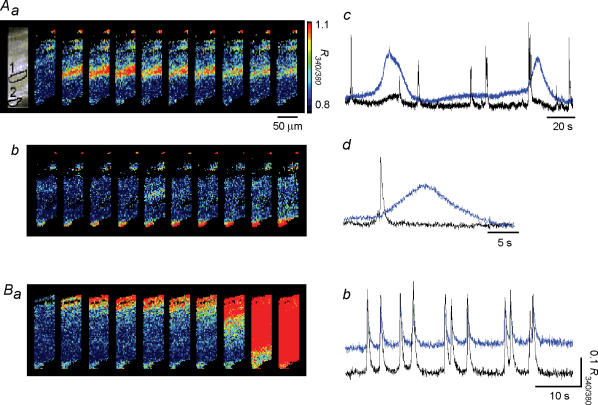

All muscle bundle preparations were observed to generate spontaneous Ca2+ transients which originated preferentially along one boundary of a muscle bundle and then spread to the other boundary (Ca2+ waves) some 30 min after superfusion with dye-free physiological saline (n = 35). However, during the early stage, there were some Ca2+ transients that did not propagate, and the synchronicity of Ca2+ transients in the transverse direction (i.e. at right angles to the long axis of muscle bundles) successively increased over time for another 30 min. On some occasions, brief measurements of Ca2+ transients were carried out during the dye-washing periods to observe the development of the synchronicity of Ca2+ transients. Generally, the synchronicity of Ca2+ transients was substantially lower during the initial period. Ca2+ transients were generated from multiple sites, presumably from smooth muscle cells, but did not spread to the neighbouring cells (Fig. 2Aa and c). In three preparations, Ca2+ transients arising from the cells on the muscle boundary, which were assumed IC by their location, occurred independently from those generated in smooth muscle cells (Fig. 2Ab). The ‘IC’ Ca2+ transients had lower frequencies (0.79 ± 0.17 min−1, 4.5 ± 1.7 min−1 in smooth muscle cells, n = 3) and much longer half-widths than those of smooth muscle Ca2+ transients (8.2 ± 3.5 s; 0.76 ± 0.25 s in smooth muscle cells, n = 3, Fig. 2Ad). After some 20 min, the ‘IC’ Ca2+ transients invariably disappeared and synchronous Ca2+ waves with increased frequencies swept across the muscle bundles (Fig. 2Ba and b). At this stage, both boundary and interbundle IC which were identified by their c-kit immunoreactivity (Fig. 3Aa) had higher basal F340 fluorescence (Fig. 3Ab), however, they did not exhibit any measurable Ca2+ transients.

Figure 2. Asynchronous Ca2+ waves in the guinea-pig bladder.

Aa, a series of frames taken every 35 ms demonstrates a Ca2+ transient originating from the middle of the muscle bundle that did not spread. Ab, another series of frames with intervals of 780 ms demonstrates a Ca2+ transient originating from a cell located adjacent to the lower boundary of the muscle bundle but failing to spread to the other boundary. Ac and d, two types of Ca2+ transients occurred, one (recorded from area 2) with lower frequency and a much longer duration than the other (recorded from area 1) that was seen more frequently. B, in the same preparation as A, after some 20 min, synchronous Ca2+ waves were generated across the muscle bundle. Ba, a series of frames taken every 35 ms demonstrates Ca2+ waves originating from the upper boundary of the muscle bundle and spreading to the other boundary. Bb, upper traces were recorded from area (1) and lower traces were recorded from area (2) in the fluorescence image of Aa.

Figure 3. Spontaneous Ca2+ transients recorded from interstitial cells in the bladder.

Aa, a pair of interstitial cells (IC) having spindle-shaped cell bodies, some 60 μm in length and less than 10 μm in width are visualized using ACK2 antibody against c-kit labelled with Alexa 488. In the same preparations loaded with fura-PE3, identified IC had higher F340 fluorescence than that of smooth muscle (Ab), while having similar F380 fluorescence to that of smooth muscle (Ac). In a different preparation loaded with fluo-4, IC located near the muscle boundary again had a higher fluorescence than that of smooth muscle (Ba). A plane image with Nomarski optics visualized the cell body of IC (Bb). When Ca2+ transients were recorded from IC (area 1) and from two smooth muscle areas (area 2 and 3) located with a separation between each of some 50 μm, synchronous Ca2+ waves were detected at areas 2 and 3 (Bc). However, IC generated slow Ca2+ transients independently from those of smooth muscles (Bc). In another fluo-4-loaded preparation which had been exposed to nifedipine (10 μm) for some 30 min, IC continued to generate slow Ca2+ transients (Ca). A series of frames with intervals of 2 s demonstrates a Ca2+ transient originating from IC (Cb).

Properties of Ca2+ transients recorded from interstitial cells

Since we were seldom able to investigate Ca2+ transients from IC in fura-PE3-loaded preparations, a different series of experiments was carried out to visualize Ca2+ signals from IC, using fluo-4-loaded detrusor muscle bundle preparations. In the following experiments, IC were identified by their morphological characteristics using Nomarski optics to avoid possible disturbance of their function with ACK-2.

Spontaneous Ca2+ transients preferentially originating along the boundary of muscle bundles and then spreading to the other boundary (Ca2+ waves) were observed about 30 min after superfusion with dye-free physiological saline at 35°C (n = 12). After synchronous Ca2+ waves across the muscle bundles had developed, IC which were identified by their location and morphology using Nomarski optics (Fig. 3Ba), invariably had higher basal fluorescence than smooth muscle cells did (Fig. 3Bb), but only some 10% of IC exhibited spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Consistent with the observation in fura-PE3-loaded preparations, IC discharged spontaneous Ca2+ transients with low frequencies (0.66 ± 0.27 min−1, n = 4). They had amplitudes of 0.43 ± 0.18 F/F0 and half-widths of 16.1 ± 3.3 s (n = 4). In all four preparations, ‘IC’ Ca2+ transients occurred independently of those of smooth muscles, even when synchronous Ca2+ waves swept across the muscle bundles (Fig. 3Bc).

Since tissue movements often caused serious artifacts in the Ca2+ measurements, the following experiments were carried out in the presence of nifedipine (10 μm) to prevent smooth muscle Ca2+ transients and associated contractions.

In the presence of nifedipine (10 μm), again some 10% of IC generated spontaneous Ca2+ transients with low frequencies (0.88 ± 0.24 min−1, n = 12, Fig. 3Ca and b). They had amplitudes of 0.39 ± 0.22 F/F0 and half widths of 17.3 ± 5.5 s (n = 12). Besides relatively large Ca2+ transients, some small Ca2+ transients, which occurred more irregularly than the larger events, were also observed (Fig. 3Bc and Cb).

Bursting Ca2+ transients in the bladder

Propagation of Ca2+ transients across detrusor smooth muscle bundles was further investigated in fura-PE3-loaded preparations.

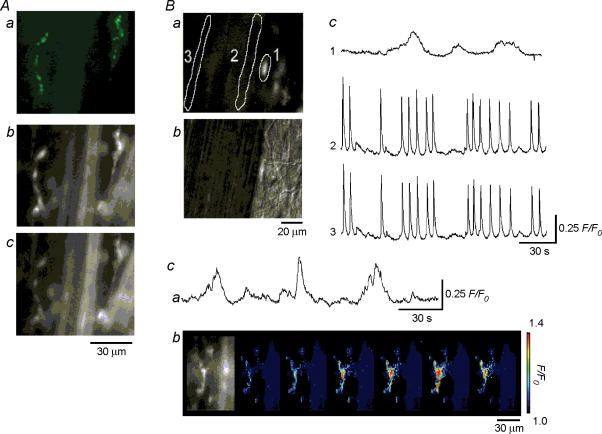

In 30 out of 35 preparations, Ca2+ transients were generated individually. In the remaining five preparations, clustered Ca2+ transients were generated with a following Ca2+ transient occurring before a preceding Ca2+ transient had returned to the baseline (bursting Ca2+ transients). When bursting Ca2+ transients were generated, they consistently originated at one of the muscle bundle boundaries and then spread to the other boundary as did individual Ca2+ waves (Fig. 4Aa). When Ca2+ waves were recorded from three areas located transversely, synchronous Ca2+ waves were observed in all areas (Fig. 4Ab). During the burst, however, Ca2+ waves originated from multiple sites, and the correspondence between Ca2+ transients was diminished (Fig. 4Ac). Figure 4Ad shows an example of a Ca2+ wave originating from the middle of the muscle bundle and then spreading to both sides.

Figure 4. Bursting Ca2+ waves in the guinea-pig bladder.

Bursting Ca2+ waves were generated in a bladder smooth muscle bundle. Aa, a series of frames taken every 38 ms demonstrates bursting Ca2+ waves originating from one boundary of the muscle bundle and spreading to the other boundary. Ab, when Ca2+ waves were recorded from three areas (areas 1, 2 and 3 in Aa) with a separation between each of some 70 μm, synchronous Ca2+ waves were observed in all areas. Ac, during the burst, however, Ca2+ transients recorded from three areas occurred independently, and had their own frequencies. Upper, middle and lower traces were recorded from area 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Ad, another series of frames taken every 38 ms demonstrates a Ca2+ wave originating from the middle of the same muscle bundle as in Aa (indicated by an arrow) during the burst and then spreading to both sides. Ba and b, synchronous bursting action potentials were recorded from two independent microelectrodes placed some 50 μm apart transversely. During the burst, there were some action potentials that did not propagate (stars). The calibration bar for pseudo colour on the right of Aa also refers to Ac.

To investigate electrical responses underlying the bursting Ca2+ transients, the preparations were impaled with two independent microelectrodes. Consistent with the observations of Ca2+ waves, when two independent electrodes were placed with transverse separation of some 50 μm, synchronous bursting action potentials were recorded from both electrodes; however, there were some action potentials that did not propagate during the bursts (Fig. 4Ba and b).

Role of gap junctions in Ca2+ waves of the bladder

It has been reported that both electrical and chemical communication between detrusor smooth muscle cells were inhibited by 18β-GA, a gap junction blocker (Hashitani et al. 2001). To further investigate the role of gap junctions in the spread of Ca2+ waves in the bladder, the effects of 18β-GA and carbenoxolone, a water soluble gap junction inhibitor, on Ca2+ waves were examined.

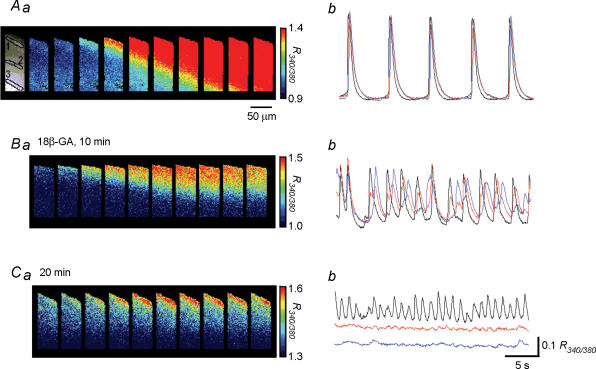

In control conditions, Ca2+ waves preferentially originated from one boundary of the muscle bundles and then spread to the other boundary with a mean conduction velocity of 1.43 ± 0.45 mm s−1 in the transverse direction (n = 15, 150 sets of Ca2+ waves, Fig. 5Aa and b). In nine out of 15 preparations, 18β-GA (40 μm) initially reduced the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves and diminished their synchronicity transversely across the muscle bundles in some 10 min (Fig. 5Ba and b). After some 20 min, Ca2+ transients were generated only on the boundary from which the Ca2+ wave had originated, and Ca2+ signals in other areas became undetectable (Fig. 5Ca and b). In the remaining six preparations, 18β-GA again disrupted the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves. During the application of 18β-GA, however, asynchronous Ca2+ transients were generated randomly in multiple areas within the muscle bundles and did not propagate to neighbouring cells (data not shown).

Figure 5. Effects of 18β-GA on calcium waves in the guinea-pig bladder.

Changes in [Ca2+]i were simultaneously recorded from separate areas located with a separation between each area of some 60 μm. Aa, a series of frames taken every 28 ms demonstrates Ca2+ waves originating from the upper boundary and spreading to the other boundary (Ab). When changes of [Ca2+]i were simultaneously recorded from three areas, Ca2+ transients occurred synchronously in all areas. Bb, in the same preparation, 18β-GA (40 μm) initially increased the frequency of Ca2+ transients, reduced their amplitude, and disrupted the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves. Ba, a series of frames taken every 28 ms demonstrates Ca2+ waves originating from the boundary of muscle bundle but failing to reach the other boundary. Cb, after some 15 min, 18β-GA almost completely prevented the propagation of Ca2+ signals leaving Ca2+ transients in a localized area. Ca, a series of frames taken every 28 ms demonstrates Ca2+ waves originating from the upper boundary but not spreading. Black, red and blue traces were recorded from area 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The calibration bars for pseudo colour on the right frames refer to each series of images.

Similarly, carbenoxolone (30 μm), initially reduced the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves and diminished their synchronicity transversely across the muscle bundles in some 10 min (n = 6). During the application of carbenoxolone, asynchronous Ca2+ transients were generated randomly within the muscle bundles, but did not propagate to neighbouring cells.

Role of intracellular Ca2+ stores in Ca2+ waves of the bladder

Although the contribution of intracellular Ca2+ stores to the initiation of Ca2+ waves in the bladder is not fundamental (Hashitani et al. 2001), they may be involved in intercellular transmission of Ca2+ waves. To clarify the role of Ca2+ stores in the propagation of Ca2+ waves in the bladder, the effects of CPA, ryanodine, two types of InsP3 receptor blockers, namely 2-APB and xestospongin C, and U-73122, a phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor were studied.

Prolonged exposure to either CPA (10 μm for 30 min) or ryanodine (100 μm for 30 min) did not alter the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves across detrusor smooth muscle bundles. In the presence of CPA (10 μm), the conduction velocity of Ca2+ waves in the transverse direction was 1.55 ± 0.61 mm s−1 (1.54 ± 0.61 mm s−1 in control, n = 7, P > 0.05). In preparations which had been exposed to ryanodine (100 μm), the conduction velocity was 1.61 ± 0.68 mm s−1 (1.63 ± 0.45 mm s−1 in control, n = 5, P > 0.05).

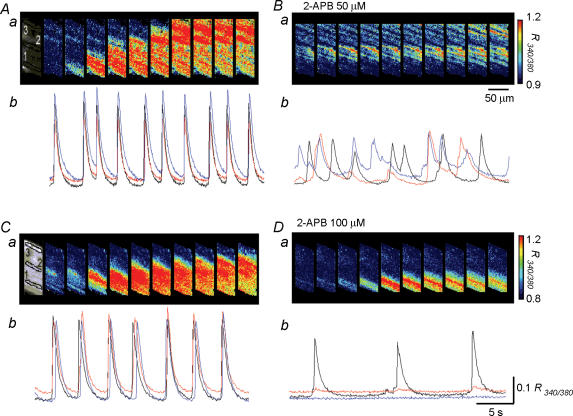

2-APB (10 or 30 μm) did not alter the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves (n = 5 for 10 μm, n = 4 for 30 μm). However, in five preparations, in which synchronous Ca2+ waves were generated (Fig. 6Aa and b), a higher concentration of 2-APB (50 μm) increased the frequency of Ca2+ transients and diminished their synchronicity (Fig. 6Bb). In the presence of 2-APB (50 μm), Ca2+ transients occurred in multiple sites but did not spread to neighbouring cells (n = 5, Fig. 6Ba). In four preparations, in which synchronous Ca2+ waves were generated (Fig. 6Ca and b), 2-APB (100 μm) initially increased but then reduced the frequency of Ca2+ transients, and completely blocked the spread of Ca2+ waves (n = 4, Fig. 6Db). In preparations which had been exposed to 2-APB (100 μm) for some 15 min, Ca2+ transients were generated only near the boundary of muscle bundles (Fig. 6Da).

Figure 6. Effects of 2-APB on Ca2+ waves in the guinea-pig bladder.

Aa, a series of frames taken every 38 ms shows Ca2+ waves originating from the lower boundary and spreading to the other boundary. Ab, when changes in [Ca2+]i were simultaneously recorded from three separate areas located with a separation between each area of some 60 μm, Ca2+ transients occurred synchronously in all areas. Bb, in the same preparation, 2-APB (50 μm) reduced the amplitude of Ca2+ transients, and disrupted the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves. Ba, a series of frames taken every 38 ms demonstrates Ca2+ transients originating from the middle of the muscle bundle but failing to spread. Ca, a series of frames taken every 38 ms shows Ca2+ waves originating from the lower boundary and spreading to the other boundary. Cb, in another preparation, when changes of [Ca2+]i were simultaneously recorded from three areas, Ca2+ transients occurred synchronously in all areas. Db, in the same preparation, 2-APB (100 μm) almost completely prevented the propagation of Ca2+ waves leaving Ca2+ transients in a localized area. Da, a series of frames taken every 38 ms shows Ca2+ transients originating from the lower boundary of the muscle bundle but failing to spread. Black, red and blue traces were recorded from area 1, 2 and 3, respectively. The calibration bar for pseudo colour on the right of Ba also refers Aa. The calibration bar for pseudo colour on the right of Da also refers to Ca.

Xestospongin C (3 μm) did not change the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves across muscle bundles. In three preparations which had been exposed to xestospongin C (3 μm) for 30 min, the conduction velocity of Ca2+ waves in the transverse direction was 1.63 ± 0.28 mm s−1 (1.61 ± 0.35 mm s−1 in control, n = 3, P > 0.05).

U-73122 (10 μm) apparently reduced the amplitude of spontaneous Ca2+ transients by some 70% but did not change the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves across muscle bundles. In five preparations which had been exposed to U-73122 (10 μm) for 20 min, the conduction velocity of Ca2+ waves in the transverse direction was 1.49 ± 0.12 mm s−1 (1.51 ± 0.15 mm s−1 in control, n = 5, P > 0.05).

Possible effects of 2-APB on electrical coupling between detrusor smooth muscle cells

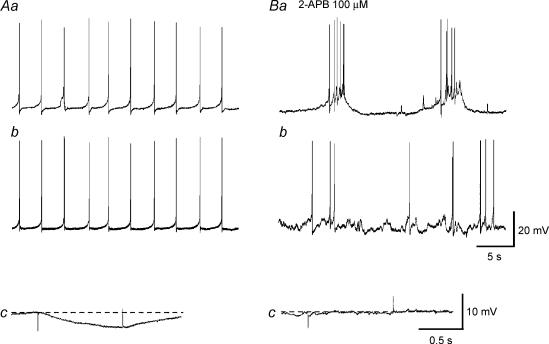

Since only high concentrations of 2-APB were able to diminish the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves, their possible effects on electrical coupling were examined by impaling the muscle bundles with two independent microelectrodes. In all preparations, synchronous action potentials were recorded from both electrodes located some 50 μm apart transversely (n = 5, Fig. 7Aa and b). 2-APB (100 μm) initially increased and then reduced the frequency of action potentials. In three preparations, either bursting or individual action potentials were recorded from the first electrode, while asynchronous individual action potentials were recorded from the second electrode (Fig. 7Ba and b). In the remaining two bundles, individual action potentials were recorded from the first electrode, while no spontaneous electrical responses were recorded from the second electrode. Regardless of the pattern of action potentials generated, 2-APB blocked electrotonic potentials induced by intracellular current injection through the first electrode and recorded at the second electrode (n = 5; Fig. 7Ac and Bc).

Figure 7. Effects of 2-APB on electrical coupling in the guinea-pig bladder.

In a bundle of detrusor smooth muscle, changes in the membrane potential were simultaneously recorded with two independent microelectrodes which were placed some 50 μm apart transversely. Aa and b, synchronous action potentials were recorded from both electrodes. Ac, inward current with amplitude of 0.5 nA, injected into the first electrode caused resultant hyperpolarization, which was detected at the second electrode. Ba and b, in the presence of 2-APB (100 μm), bursting action potentials were recorded from the first electrode, while individual action potentials were recorded from the second electrode. Bc, 2-APB almost completely blocked electrotonic potentials at the second electrode. Resting membrane potential was –46 mV at the first electrode (Aa), and –45 mV at the second electrode (Ab).

Role of extracellular Ca2+ in Ca2+ waves of the bladder

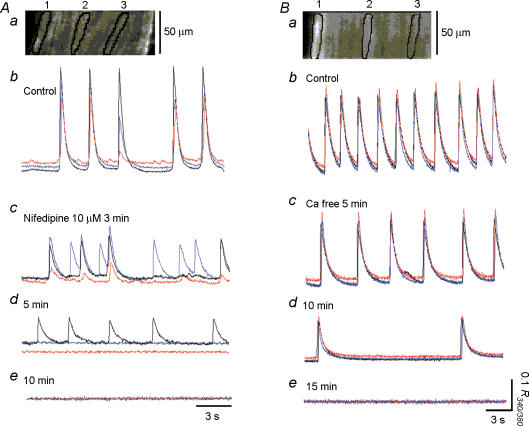

Since the role of action potentials in the propagation of spontaneous excitation has been suggested to be critical, the effects of nifedipine and nominally Ca2+-free solution on Ca2+ waves were examined.

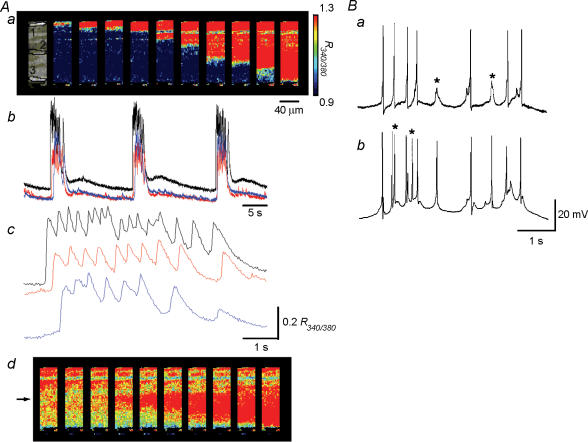

In three preparations, in which synchronous Ca2+ waves were generated (Fig. 8Ab), nifedipine (10 μm) initially diminished the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves (Fig. 8Ac and d), and then prevented their generation after some 10 min (Fig. 8Ae). In another four preparations, nifedipine (10 μm) simply abolished Ca2+ transients without first affecting their synchronicity.

Figure 8. Effects of nifedipine and nominally Ca2+-free solution on Ca2+ waves in the guinea-pig bladder.

Aa, changes in [Ca2+]i were simultaneously recorded from three separate areas located transversely with a separation between each area of some 50 μm. Blue, black and red traces were recorded from areas 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Ab, in control conditions when changes of [Ca2+]i were simultaneously recorded from three areas, Ca2+ transients occurred synchronously in all areas. Ac, nifedipine 10 μm initially reduced the synchronicity and amplitude of Ca2+ transients. Ad, after some 5 min, nifedipine prevented the generation of Ca2+ transients in the two areas, while leaving small Ca2+ transients in the remaining area. Ae, nifedipine abolished all Ca2+ transients after 10 min. Ba, in another preparation, changes of [Ca2+]i were simultaneously recorded from three areas located transversely with a separation between each area of some 60 μm. Blue, black and red traces were recorded from areas 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Bb, in control solution, Ca2+ transients occurred synchronously in all areas. Bc and d, nominally, Ca2+-free solution initially reduced the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ transients but did not disrupt the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves. Be, after some 15 min, nominally Ca2+-free solution prevented the generation of Ca2+ transients.

Switching from normal physiological saline to nominally Ca2+-free solution reduced the frequency of Ca2+ waves and prevented their generation in some 15–20 min (Fig. 8Bb–e). In a separate series of experiments, the effect of Ca2+-free solution on spontaneous action potentials was examined. Introduction of Ca2+-free solution transiently increased the frequency of action potentials, but then their frequency was reduced with depolarization of the membrane. In some 10–15 min, Ca2+-free solution depolarized the membrane by about 10 mV and abolished action potentials (n = 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we have investigated the putative role of IC in the generation of spontaneous activity in smooth muscle bundles in the guinea-pig bladder. Consistent with a previous report (McCloskey & Gurney, 2002), IC are abundantly distributed in the bladder and run parallel with the smooth muscle bundles. IC are located adjacent to the boundary of muscle bundles (boundary IC), scattered amongst smooth muscle cells (intramusclular IC) and more dominantly distributed over connective tissues between muscle bundles (interbundle IC).

McCloskey & Gurney (2002) have suggested that IC on the boundary of muscle bundles (boundary IC) could be ideally situated to signal to the bulk of smooth muscles. They also reported that isolated IC in the bladder were capable of generating intracellular Ca2+ waves spontaneously. In the same study, two types of spontaneous Ca2+ waves were generated, and larger waves occurred with the frequency of three waves min−1 and lasted for some 7 s. In our study, we were able to visualize Ca2+ transients from IC in fluo-4-loaded preparations. IC generated two types of spontaneous Ca2+ transients; large, slow Ca2+ transients and small, irregular Ca2+ transients. Slow Ca2+ transients occurred independently of those of smooth muscles even when synchronous Ca2+ waves swept across muscle bundles. Their duration and frequency were completely different from those of smooth muscle cells, but were similar to those of isolated IC. Ca2+ transients recorded from IC persisted in the presence of nifedipine as did carbachol-induced Ca2+ transients in isolated IC (McCloskey & Gurney, 2002), suggesting that voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels are not involved in the generation of this activity. Therefore, although the location of boundary IC seems to be ideal to drive the bulk of smooth muscles, we have no evidence to support this idea at least under our experimental conditions. In mouse ileum, no synchronicity was indeed observed between ICC and smooth muscle Ca2+ signals in some 40% of preparations, and Ca2+ signals in ICC had slower frequencies and longer durations than those of smooth muscle cells (Yamazawa & Iino, 2002). Furthermore, submucosal ICC generated spontaneous plateau potentials with rhythms different from those generated by smooth muscle cells in mouse proximal colon (Yoneda et al. 2002).

Since IC in the bladder are located along the boundary of muscle bundles, they may act as a conducting system in signal transmission between smooth muscle cells. Indeed, the conduction velocity of action potentials in the axial direction is about 30 times larger than that in transverse direction (Hashitani et al. 2001). However, unlike septal ICC in canine gastric antrum (Horiguchi et al. 2001), the physiological significance of IC-mediated communication between bundles is likely to be minor, since the normal bladder does not generate coordinated contractions until activated by the parasympathetic excitatory neurones. Furthermore, in multibundle detrusor smooth muscle preparations, spontaneous action potentials or Ca2+ transients were not associated with corresponding contractions, while transmural nerve stimulation invariably produced synchronous contractions (Hashitani et al. 2000). Bladder overactivity has been suggested to result from the increased coupling between detrusor smooth muscle cells (Brading, 1997). However, the electrical coupling between the cells in a guinea-pig model of bladder outflow obstruction has been reported to be reduced (Seki et al. 1992). Recently, increased connexin43-mediated intercellular communications in a rat model of bladder overactivity has been reported (Christ et al. 2002; Haefliger et al. 2002). Micromotion of the bladder wall, which may be attributed to spontaneous contractions of individual muscle bundles, has also been reported to be enhanced in a rat model of bladder overactivity (Drake et al. 2003). Therefore, either quantitative or qualitative alterations in interbundle IC could account for the increased excitability in the overactive bladder. Interestingly, developmental changes in spontaneous smooth muscle activity in the rat bladder have been reported (Széll et al. 2003). The authors suggested that development of multiple pacemaker sites in older animals would reduce coordination within the bladder wall and improve storage function.

When the spread of Ca2+ waves in the muscle bundles was carefully observed, they did not always travel from one boundary to the other boundary at constant conduction velocity. Some Ca2+ waves originating from one boundary travelled rapidly to the middle of the bundles, followed by a delay, and then continued to spread to the other boundary. Occasionally, Ca2+ waves ceased halfway across the muscle bundle. Although we do not know the detailed relationship between the distribution of intramuscular IC and the propagation of Ca2+ waves, IC may modulate communication between subgroups of smooth muscles in which Ca2+ waves travel very rapidly. Similar observations have been made in the murine large intestine, and the authors suggested that the interaction between muscle zones gives a large degree of flexibility in the muscle behaviour (Hennig et al. 2002). Furthermore, in the guinea-pig renal pelvis, ICC-like cells have been suggested to provide a preferential pathway, conducting and amplifying pacemaker signals originating from ‘atypical’ smooth muscles (Klemm et al. 1999).

It has been reported that both electrical and morphological coupling between detrusor smooth muscle cells are readily blocked by 18β-GA, a gap junction blocker (Hashitani et al. 2001). In the current work, the propagation of Ca2+ waves was again disrupted by 18β-GA or carbenoxolone, indicating that their propagation in the bladder exclusively resulted from the spread of spontaneous action potentials. In gastrointestinal tissues, Ca2+ waves were also disrupted by gap junction blockers (Hennig et al. 2002). Therefore, regardless of the basis of the underlying electrical activity, intercellular communication appears to be mediated by gap junctions in smooth muscle tissues. In the presence of 18β-GA, Ca2+ transients were generated only in the area near the muscle boundary, and the remaining parts had almost no Ca2+ transients in some 60% of preparations. In the remaining 40% of preparations, however, asynchronous Ca2+ waves were generated randomly within the muscle bundles. These differences could be attributed to the different distribution of pacemaker cells in the muscle bundles. Alternatively, 18β-GA may activate the generation of Ca2+ transients in some populations of follower cells presumably by depolarizing the cell membrane. Since isolated detrusor smooth muscle cells are capable of generating spontaneous action potentials, which are almost identical to those recorded from multicellular preparations (Montgomery & Fry, 1992), smooth muscle cells themselves are capable of generating spontaneous activity. Indeed, under particular circumstances, such as dye-washing periods and during bursting Ca2+ waves, individual smooth muscle cells generated asynchronous Ca2+ transients. During bursting action potentials, some individual action potentials did not propagate successfully, presumably due to an increased intracellular Ca2+ level which may inhibit both voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels and gap junction channels (Dhein, 1998).

Unlike slow waves in gastrointestinal tissues, action potentials in the bladder were abolished by blockers of L-type Ca2+ channels but not by inhibitors of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Hashitani & Brading, 2003), indicating a critical role of L-type Ca2+ channels in the generation of spontaneous excitation. The propagation of Ca2+ waves was also considered to be mediated by the spread of action potentials by means of their regenerative nature (Hashitani et al. 2001). However, a contribution of Ca2+ stores to the propagation of Ca2+ waves has not been excluded. In gastric smooth muscle, the linkage between voltage and Ca2+ release has been suggested to provide a means for stores to interact as strongly coupled oscillators, resulting in synchronous Ca2+ waves (Van Helden & Imtiaz, 2003). Alternatively, Ca2+ release from intracellular Ca2+ stores may act on gap junctions to reduce their conductivity (Dhein, 1998). In the bladder, however, CPA, ryanodine, xestospongin C and U-73122 failed to alter the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves. Therefore, neither InsP3 nor ryanodine receptors on the store membrane in detrusor smooth muscles were necessary for the propagation of Ca2+ waves.

Interestingly, 2-APB but neither xestospongin C nor U-73122 disrupted the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves. In gastrointestinal tissues, Ca2+ waves were blocked by both 2-APB and xestspongin C (Hennig et al. 2002). Since neither the generation nor propagation of Ca2+ waves was inhibited by CPA, the contribution of Ca2+ handling by the stores to Ca2+ waves in the bladder may not be important. In the bladder, low concentrations of 2-APB (10–30 μm), which blocked electrical slow waves in gastric smooth muscles (Fukuta et al. 2002), had no effect on either the amplitude or synchronicity of Ca2+ waves, while higher concentrations of 2-APB (50–100 μm) disrupted the synchronicity and suppressed the residual Ca2+ transients. Recently, the blockade of gap junctions by high concentrations of 2-APB has been reported (Harks et al. 2003). In the present study, a high concentration of 2-APB (100 μm) indeed blocked electrical coupling between detrusor smooth muscle cells examined using two independent microelectrodes as did 18β-GA (Hashitani et al. 2001). Therefore, the uncoupling effects of 2-APB appear to be related to the blockade of gap junctions rather than the inhibition of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release.

Nominally, Ca2+-free solutions reduced the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ transients and prevented their generation after some 15 min, without affecting the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves before blockade, suggesting that Ca2+ transients in the bladder largely rely on Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space. Since nominally Ca2+-free solution depolarized the membrane and reduced the frequency of action potentials, its effects on Ca2+ waves were not due to membrane hyperpolarization. Ca2+ waves in the bladder were also blocked by nifedipine, a blocker of L-type Ca2+ channels. In four preparations, nifedipine simply blocked the generation of Ca2+ transients as did nominally Ca2+-free solutions, while in three preparations it disrupted the synchronicity of Ca2+ waves before preventing their generation. These differences may result from a heterogeneous sensitivity of detrusor smooth muscle cells for nifedipine. Since the propagation of Ca2+ waves required electrical coupling through gap junctions and the regenerative action potential, even small numbers of cells which are relatively sensitive to nifedipine could prevent the successful propagation of Ca2+ waves through the muscle bundles.

In conclusion, the propagation of Ca2+ waves in the bladder appears to be mediated by L-type Ca2+ channels and the spread of action potentials through gap junctions. Both the generation and propagation of Ca2+ signals rely on these channels, while the contribution of Ca2+ stores may not be essential. Although IC are abundantly distributed in the bladder and are capable of generating spontaneous Ca2+ transients, they do not have an obvious role in pacemaking. Rather, spontaneous excitation in the bladder may be initiated by detrusor smooth muscle cells themselves, with the main role of IC being to modulate the signal transmission.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor A.F. Brading and Dr D.F. Van Helden for their valuable comments on the manuscript. The authors also grateful to Drs F.R. Edwards and Y. Kito and Mr P.J. Dosen for their technical advice with the c-kit immunohistochemical studies. This work was supported by a grant from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (No. 15591704) to H.H.

References

- Brading AF. A mynogenic basis for the overactive bladder. Urology. 1997;50:57–67. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ GJ, Day NS, Day M, Zhao W, Persson K, Pandita RK, Andersson KE. Increased connexin43-mediated intercellular communication in a rat model of bladder overactivity in vivo. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:R1241–R1248. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00030.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhein S. Gap junction channels in the cardiovascular system: pharmacological and physiological modulation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:229–241. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake MJ, Hedlund P, Harvey IJ, Pandita RK, Andersson KE, Gillespie JI. Partial outlet obstruction enhances modular autonomous activity in the isolated rat bladder. J Urol. 2003;170:276–279. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000069722.35137.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia G. Ionic conductances in gastrointestinal smooth muscles and interstitial cells of Cajal. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:45–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuta H, Kito Y, Suzuki H. Spontaneous electrical activity and associated changes in calcium concentration in guinea-pig gastric smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2002;540:249–260. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabella G. Intramural neurons in the urinary bladder of the guinea-pig. Cell Tissue Res. 1990;261:231–237. doi: 10.1007/BF00318664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haefliger JA, Tissieres P, Tawadros T, Formenton A, Beny JL, Nicod P, Frey P, Meda P. Connexins 43 and 26 are differentially increased after rat bladder outlet obstruction. Exp Cell Res. 2002;274:216–225. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanani M, Belzer V, Rich A, Faussone-Pellegrini S. Visualization of interstitial cells of Cajal in living, intact tissues. Microsc Res Techniq. 1999;47:336–343. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19991201)47:5<336::AID-JEMT5>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harks EG, Camina JP, Peters PH, Ypey DL, Scheenen WJ, Van Zoelen EJ, Theuvenet AP. Besides affecting intracellular calcium signaling, 2-APB reversibly blocks gap junctional coupling in confluent monolayers, thereby allowing measurement of single-cell membrane currents in undissociated cells. FASEB J. 2003;17:941–943. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0786fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Brading AF. Ionic basis for the regulation of spontaneous excitation in detrusor smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig urinary bladder. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:159–169. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Brading AF, Suzuki H. Correlation between spontaneous electrical, calcium and mechanical activity in detrusor smooth muscle of the guinea-pig bladder. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:183–193. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Bramich NJ, Hirst GDS. Mechanisms of excitatory neuromuscular transmission in the guinea-pig urinary bladder. J Physiol. 2000;524:565–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Fukuta H, Takano H, Klemm M, Suzuki H. Origin and propagation of spontaneous excitation in smooth muscle of the guinea-pig urinary bladder. J Physiol. 2001;530:273–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0273l.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashitani H, Van Helden DF, Suzuki H. Properties of spontaneous depolarizations in circular smooth muscle cells of rabbit urethra. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1627–1632. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig GW, Smith CB, O'Shea DM, Smith TK. Patterns of intracellular and intercellular Ca2+ waves in the longitudinal muscle layer of the murine large intestine in vitro. J Physiol. 2002;543:233–253. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera GM, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of urinary bladder smooth muscle contractions by ryanodine receptors and BK and SK channels. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:R60–R68. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.1.R60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst GDS, Ward SM. Interstitial cells: involvement in rhythmicity and neural control of gut smooth muscle. J Physiol. 2003;550:337–346. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi K, Semple GS, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Distribution of pacemaker function through the tunica muscularis of the canine gastric antrum. J Physiol. 2001;537:237–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0237k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John H, Wang X, Wehrli E, Hauri D, Maake C. Evidence of gap junctions in the stable nonobstructed human bladder. J Urol. 2003;169:745–749. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000045140.86986.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm MF, Exintaris B, Lang RJ. Identification of the cells underlying pacemaker activity in the guinea-pig upper urinary tract. J Physiol. 1999;519:867–884. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0867n.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey KD, Gurney AM. Kit positive cells in the guinea pig bladder. J Urol. 2002;168:832–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery BS, Fry CH. The action potential and net membrane currents in isolated human detrusor smooth muscle cells. J Urol. 1992;147:176–184. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus J, Wolburg H, Hermsdorf T, Stolzenburg JU, Dorschner W. Detrusor smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig are functionally coupled via gap junctions in situ and in cell culture. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;309:301–311. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzone MA, Watkins SC, Alber SM, King WE, De Groat WC, Chancellor MB, Fraser MO. Identification of c-kit-positive cells in the mouse ureter: the interstitial cells of Cajal of the urinary tract. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:F925–F929. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00138.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders KM. A case for interstitial cells of Cajal as pacemakers and mediators of neurotransmission in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:492–515. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki N, Karim OM, Mostwin JL. Changes in electrical properties of guinea pig smooth muscle membrane by experimental bladder outflow obstruction. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:F885–F891. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.5.F885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant GP, Hollywood MA, Mccloskey KD, McHale NG, Thornbury KD. Role of IP3 in modulation of spontaneous activity in pacemaker cells of rabbit urethra. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:C1349–C1356. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.5.C1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant GP, Hollywood MA, McCloskey KD, Thornbury KD, McHale NG. Specialised pacemaking cells in the rabbit urethra. J Physiol. 2000;526:359–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Hirst GDS. Regenerative potentials evoked in circular smooth muscle of the antral region of guinea-pig stomach. J Physiol. 1999;517:563–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0563t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Széll EA, Somogyi GT, De Groat WC, Szigeti GP. Developmental changes in spontaneous smooth muscle activity in the neonatal rat urinary bladder. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:R809–R816. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00641.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Helden DF, Imtiaz MS. Ca2+ phase waves: a basis for cellular pacemaking and long-range synchronicity in the guinea-pig gastric pylorus. J Physiol. 2003;548:271–296. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Helden DF, Imtiaz MS, Nurgaliyeva K, Von Der Weid PY, Dosen PJ. Role of calcium stores and membrane voltage in the generation of slow wave action potentials in guinea-pig gastric pylorus. J Physiol. 2000;522:245–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Ordog T, Koh SD, Baker SA, Jun JY, Amberg G, Monaghan K, Sanders KM. Pacemaking in interstitial cells of Cajal depends upon calcium handling by endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. J Physiol. 2000;525:355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazawa T, Iino M. Simultaneous imaging of Ca2+ signals in interstitial cells of Cajal and longitudinal smooth muscle cells during rhythmic activity in mouse ileum. J Physiol. 2002;538:823–835. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneda S, Takano H, Takaki M, Suzuki H. Properties of spontaneously active cells distributed in the submucosal layer of mouse proximal colon. J Physiol. 2002;542:887–897. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.018705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]