Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine whether the net efficiency of mammalian muscles depends on muscle fibre type. Experiments were performed in vitro (35°C) using bundles of muscle fibres from the slow-twitch soleus and fast-twitch extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles of the mouse. The contraction protocol consisted of 10 brief contractions, with a cyclic length change in each contraction cycle. Work output and heat production were measured and enthalpy output (work + heat) was used as the index of energy expenditure. Initial efficiency was defined as the ratio of work output to enthalpy output during the first 1 s of activity. Net efficiency was defined as the ratio of the total work produced in all the contractions to the total, suprabasal enthalpy produced in response to the contraction series, i.e. net efficiency incorporates both initial and recovery metabolism. Initial efficiency was greater in soleus (30 ± 1%; n = 6) than EDL (23 ± 1%; n = 6) but there was no difference in net efficiency between the two muscles (12.6 ± 0.7% for soleus and 11.7 ± 0.5% for EDL). Therefore, more recovery heat was produced per unit of initial energy expenditure in soleus than EDL. The calculated efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation was lower in soleus than EDL. The difference in recovery metabolism between soleus and EDL is unlikely to be due to effects of changes in intracellular pH on the enthalpy change associated with PCr hydrolysis. It is suggested that the functionally important specialization of slow-twitch muscle is its low rate of energy use rather than high efficiency.

Muscles convert the chemical free energy obtained from ATP hydrolysis into heat and, if allowed to shorten, mechanical work. The fraction of the energy used that is converted into work is the efficiency. Efficiency can be calculated using several experimental approaches that can be distinguished by the index of energy consumption measured. Precise measurements of the efficiency of individual muscles can be made only using an isolated muscle or fibre preparation. One experimental approach is to calculate the efficiency of an isolated muscle by measuring just the energy consumed during a brief period of shortening (Hill, 1939, 1964; Woledge et al. 1988; Barclay et al. 1993; Barclay, 1996). In this case, energy is used by the actomyosin cross-bridge interactions (which generate the mechanical work) and by ion pumps involved in excitation–contraction coupling. Efficiency calculated using the energy that is consumed simultaneously with work production is called initial efficiency (ɛI). If a skinned muscle fibre preparation (i.e. a fibre with its sarcolemma removed) is used, then it is possible to eliminate the ion pump contribution to energy use so that all the energy consumed can be attributed to cross-bridge activity (e.g. Reggiani et al. 1997; He et al. 1999).

Another approach is to measure all the energy consumed by a muscle in response to a period of contractile activity. In this case, energy is used not only by cross-bridges and ion pumps but also by the mitochondria for oxidative reversal of the high-energy phosphate breakdown that occurred during the contractions (Woledge, 1968; Gibbs & Gibson, 1972; Wendt & Gibbs, 1973; Heglund & Cavagna, 1987). Furthermore, the measured energy cost also includes that associated with force development and relaxation. In thermodynamic terms, the reversal of the initial chemical breakdown is accompanied by absorption of an amount of energy equivalent to the initial energy output so that the net amount of heat and work, or enthalpy, produced is proportional to the mitochondrial activity required to regenerate all the high-energy phosphate used (Crow & Kushmerick, 1982; Paul, 1982; Lou, Van der Laarse, Curtin & Woledge, 2000). The net enthalpy output is typically about twice as great as the initial enthalpy output so that the value of efficiency calculated using the net enthalpy output (i.e. the net efficiency, ɛNet) is about half ɛI.

The focus of this study is the relative efficiency of fast-twitch and slow-twitch mammalian muscles. In most, but not all, studies of initial efficiency, slow-twitch muscles have been reported to be more efficient than fast twitch muscles. For example, skinned fibres from rat soleus (a slow-twitch muscle) were more efficient than fast-twitch tibialis anterior fibres (Reggiani et al. 1997) and intact mouse soleus muscles were more efficient than EDL muscles (Barclay, 1996). In an earlier study (Barclay et al. 1993), using the same two mouse muscles but at a lower temperature (21°C versus 25°C), no fibre-type dependence was found in peak efficiency (maximum ɛI ∼30%). However, in subsequent experiments at 20°C, using a similar contraction protocol but improved heat recording apparatus (for apparatus details, see Mellors et al. 2001), the slow-twitch soleus was found to be more efficient than EDL (maximum ɛI40% and 30%, respectively; see Fig. 7 of Smith et al. 2004). The difference between those two sets of experiments was that variability in measurement of rate of heat output was greatly reduced in the more recent experiments. The peak efficiency of skinned human muscle fibres has been reported to be independent of fibre type (He et al. 2000), although the variability in those data restricted the ability to resolve fibre-type differences. On balance, it seems likely that the initial efficiency of slow-twitch muscles is greater than that of fast-twitch muscles.

Figure 7. Summary of kinetics of postcontractile recovery heat production.

Characteristics of recovery heat production after the contraction series was completed were quantified by measuring the time constant for the decline in rate of heat production (A) and the maximum rate of recovery heat production (B). These were determined by fitting a single exponential curve through the rate of heat production data through 50 s of data after the end of the last strain cycle (Fig. 4). Symbols are mean values (± s.e.m.) for soleus (□) and EDL (▪). There was no significant effect of contraction frequency on maximum rate of recovery heat for soleus. The values for EDL varied significantly with contraction frequency. Note that, except at the lowest contraction frequencies, the rates of recovery heat are not steady state values because the duration of the contractions was too short for a steady state to be achieved. For both muscles, recovery time constant was independent of contraction frequency and the values for soleus and EDL were similar.

A small number of studies of isolated muscle efficiency have used suprabasal O2 consumption or its energetic equivalent, the net enthalpy output (ΔHNet), as the index of energy cost. The results of these studies are contradictory. Gibbs and colleagues (Gibbs & Gibson, 1972; Wendt & Gibbs, 1973), using a series of afterloaded isotonic contractions, found the maximum ɛNet of rat slow-twitch muscles (19%) to be greater than that of fast-twitch muscles (10%). However, it was also observed that ɛNet of EDL could be increased to > 15% if tetanus duration was reduced from 1 s to 0.5 s. In contrast, Heglund & Cavagna (1987), using O2 uptake measurements and a cyclic strain pattern involving isovelocity length changes, found the maximum ɛNet of rat fast-twitch muscles was greater than that of slow-twitch muscles (19% and 15%, respectively). Not only were different protocols used in these studies, but also the experimental temperatures differed (27°C, Gibbs & Gibson, 1972; Wendt & Gibbs, 1973; 20°C, Heglund & Cavagna, 1987).

Therefore, it remains unclear whether maximumɛNet depends on muscle fibre type. The aim of the current study was to compare ɛNet of isolated fast- and slow-twitch muscles using a protocol in which ɛI was close to maximum values for each muscle type. A cyclic contraction protocol, similar to that devised by Heglund & Cavagna (1987), was used. Muscles from mice were used because their mechanical, energetic and histochemical properties are well characterized (Close, 1965; Crow & Kushmerick, 1982; Barclay et al. 1993; Barclay, 1994, 1996). The mouse soleus and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles provide preparations with contrasting fibre type characteristics. Mouse soleus muscle is composed of 75% slow-twitch (or type 1) fibres whereas the EDL is > 90% fast-twitch (types 2a and 2b) fibres (Crow & Kushmerick, 1982; Lynch et al. 2001). Consistent with these histochemical characteristics, the two muscles have distinctive energetic profiles (Barclay et al. 1993; Barclay, 1994, 1996). For each preparation used, both initial efficiency and net efficiency were determined using the same set of contractions.

Methods

Experiments were performed in vitro using bundles of muscle fibres dissected from the slow-twitch soleus and fast-twitch EDL muscles of adult mice (Swiss strain). Muscles were obtained after the mice had been rendered unconscious by inhalation of CO2 and then killed by cervical dislocation. All animal-handling procedures were approved by the Griffith University Animal Ethics Committee. During dissection and experiments, muscles were bathed in oxygenated (95% O2–5% CO2) Krebs-Henseleit solution of the following composition (mm): NaCl, 118; KCl, 4.75; KH2PO4, 1.18; MgSO4, 1.18; NaHCO3, 24.8; CaCl2, 2.54; glucose, 10. Aluminium foil clips were crimped onto each tendon to provide low compliance links between the muscles and the recording apparatus. The number of muscle fibres in the bundles can be estimated on the basis that each whole soleus or EDL muscle contains about 1200 fibres (Luff & Atwood, 1971) and the mass of the fibre bundles was ∼20% of the mass of the whole muscle; therefore, the bundles would have contained ∼250 fibres. The mean values (± s.e.m., n = 18 of each muscle type) of preparation mass and length were: EDL, 3.9 ± 0.3 mg, 8.9 ± 0.2 mm; soleus, 4.1 ± 0.3 mg, 11.0 ± 0.2 mm.

During experiments, fibre bundles were attached, via fine stainless steel rods, to a force transducer (SensoNor AE801, Horten, Norway) at one end and a servo-controlled motor (322B, Aurora Scientific Instruments, Toronto, Canada) at the other. The muscles lay along the active junctions of an antimony–bismuth thermopile (Mulieri et al. 1972; Barclay et al. 1995) that was used to measure changes in muscle temperature. The recording region of the thermopile was 4 mm long, contained 16 thermocouples and produced 1.38 mV K−1. At either end of the recording region was an additional 4 mm of thermocouples, not connected to the recording region but ensuring a constant rate of heat loss along the muscle's length (Hill, 1937). The temperature of the experimental chamber was maintained at 35°C, which is close to the in vivo temperature of the legs of small rodents (Ardevol et al. 1998).

At the start of each experiment, stimulus amplitude was set to 110% of that required to elicit maximum twitch force. The stimulus amplitude and width were typically 5 V and 1 ms. The optimum length for tetanic force output (Lo) was then found using a series of brief tetanic contractions and length was set to 110% Lo. This ensured that shortening occurred across the plateau region of the force–length relationship.

Recordings and calculations

Enthalpy output, which is the sum of the work and heat produced, was measured and used as the index of muscle energy use. Work output was calculated from measurements of force output and change in muscle length and was the integral of force output with respect to the change in length (Josephson, 1985). Heat output was calculated from the change in muscle temperature, measured using the thermopile, and muscle heat capacity. During recording, heat was continually lost from the preparation through the thermocouple wires into the frame holding the thermopile. The rate of heat loss and the heat capacity of the preparation and any adhering saline were calculated from the time course of cooling after the muscle was heated using the Peltier effect (Kretzschmar & Wilkie, 1972). This was done before each series of contractions. Heat produced in the muscle by the stimulus current was determined by stimulating a muscle made inexcitable by procaine (muscle immersed for 15 min in Krebs solution containing 30 mm procaine). Its amplitude was < 3% of the total heat produced and was not subtracted from the total heat output. When measuring net heat output, recovery metabolism was considered complete when muscle temperature returned to within ± 0.5 × 10−3°C of its pre-contraction value (compared to maximum temperature changes of > 20 × 10−3°C) and remained constant for > 10 s.

Contraction protocols

The contraction protocol used was designed in accord with the following ideas. (1) A short series of contractions was used to ensure that the amplitude of the temperature signal was large enough to allow the relatively low rate of recovery heat to be measured accurately. Longer series of contractions were avoided to minimize the possibility of anoxia developing in the centre of the muscles. (2) A pattern of length changes that included a short isometric period at the start of each contraction was used so that shortening would only commence once force was well developed. This maximized the work output in each cycle. (3) Contraction frequencies were chosen to span the range of stride frequencies used by mice for walking, trotting and running (Clarke & Still, 1999).

The contraction protocol used consisted of a series of 10 brief contractions with a cyclic change in muscle length (i.e. strain) associated with each contraction (Fig. 1). Cycles were defined as starting when the first stimulus pulse in each contraction was delivered. The strain pattern in each cycle consisted of three phases. (1) An isometric phase during which force developed to at least 40% of the isometric force (the shortening force at which efficiency is maximum in these muscles; Barclay, 2003). (2) Isovelocity shortening, at the velocity at which ɛI was maximum (calculated as described below), which continued until active force generation had ceased. (3) Isovelocity lengthening of the relaxed muscle back to the initial length. This strain pattern is similar to that used by Heglund & Cavagna (1987) and its energetically important feature was that shortening occupied the majority of the contraction and relaxation thus minimizing the contribution to net enthalpy output of energy produced by the muscle when not shortening.

Figure 1. Contraction protocol.

A, an example of the strain (i.e. muscle length change) protocol used to measure ɛNet. Cycles were defined as starting when the first stimulus pulse in the cycle was delivered. Muscle length was altered in three phases: an isometric phase followed by constant velocity shortening at the velocity at which efficiency was maximum and then constant velocity lengthening back to the starting length. B, the time course of force output for an EDL preparation in response to the stimuli and strain shown in A. Force increased to above the shortening force during the isometric phase then during shortening declined to a steady lower value and eventually relaxed. Force output was low during lengthening. Records are from an EDL preparation (mass, 2.12 mg; length, 10.0 mm). The muscle's maximum isometric force output was 38 mN or 179 mN mm−2.

A series of preliminary experiments (n = 5 of each muscle type) was performed to estimate the shortening velocity at which ɛI was maximal using this strain pattern at 35°C. For each muscle, ɛI was measured (for a description of this measurement, see Fig. 2A) at a range of shortening velocities between 0.5 and 3 muscle lengths s−1 (ML s−1) for soleus and 1 and 5 ML s−1 for EDL. Data describing efficiency as a function of shortening velocity were fitted with second-order polynomials using the method of least squares and the velocity at which the maximum value of the fitted curve was reached was measured. Maximum ɛI occurred when the velocity of the second phase (mean ± s.e.m.) was 1.3 ± 0.2 ml s−1 for soleus and 2.8 ± 0.3 ml s−1 for EDL fibre bundles. These velocities were used for the isovelocity lengthening phase of the strain cycle.

Figure 2. Calculation of initial and net mechanical efficiency.

A, initial mechanical efficiency (ɛI) was calculated using the first 1 s of each record, during which almost all the heat produced could be attributed to initial metabolism (i.e. PCr breakdown) and little heat was produced by recovery processes. In the example shown, from an EDL preparation contracting at 1 Hz, work and heat were produced at a high rate during the contraction (duration of each contraction, ∼0.2 s). In the interval between the first and second contractions, there was no additional heat production, consistent with the idea that no detectable recovery metabolism was occurring at this time. Enthalpy output was calculated by adding the work and heat produced and ɛI was calculated by dividing the amount of work produced in the first 1 s (ΔW) by the amount of enthalpy produced during the same interval (ΔHI). The time scale indicates the time elapsed since the delivery of the first stimulus pulse. B, net mechanical efficiency (ɛNet) was calculated using the total work produced in all the contractions in a series (ΔWTotal) and the cumulative total of the enthalpy produced, in excess of resting metabolism, during and after the series of contractions (ΔHNet). The records illustrated are from an EDL preparation contracting at 1 Hz.

Efficiency calculations

In general terms, muscle efficiency is the ratio of work produced to energy consumed to produce that work. Three definitions of efficiency were used in this study: (1) initial mechanical efficiency, (2) net mechanical efficiency and (3) thermodynamic efficiency of oxidative recovery. Precise definitions and the methods for calculating each of these follow.

Initial mechanical efficiency

Initial mechanical efficiency (ɛI) was defined as the ratio of the work output to the initial enthalpy output (ΔHI). ΔHI is the enthalpy arising from the net breakdown of PCr during a contraction and excludes any contribution from mitochondrial activity (i.e. recovery metabolism). The method for calculating work output excluded contributions to the work performed during shortening by both parallel and series elastic elements (Mellors et al. 2001). To minimize the effects of recovery metabolism on calculated values of ɛI, ΔHI was calculated using the amounts of work and heat produced during only the first 1 s of the contraction protocol (Fig. 2A). When contraction frequency had a non-integer value, the measurement time was increased so that work and heat produced were measured over an integral number of cycles (e.g. if frequency was 2.5 Hz, energy output was measured over 3 cycles or 1.2 s). This ensured that the force output was the same at the start and end of the interval over which heat was measured, thus avoiding contributions to heat output from tension-dependent thermal changes and to work output from series elastic elements. The contribution of recovery metabolism to heat production during the first 1 s of activity was estimated on the basis of recovery metabolism increasing with a time constant of ∼10 s (Fig. 8) and assuming that in the steady state the amount of recovery metabolism per contraction cycle was approximately the same as the amount of initial heat (i.e. the recovery/initial enthalpy ratio (R/I) = 1; see Results). It was estimated that recovery metabolism would have contributed at most ∼4% of the heat produced in the first 1 s of a contraction protocol which corresponds to a difference in ɛI values of < 0.9%.

Figure 8. Estimated partial pressure of O2 profiles through cylindrical muscle.

The pO2 profile through muscles calculated for steady state conditions. Profiles are shown for muscles at rest and when active. For active muscle, profiles corresponding to maximum recovery heat rates of 10 and 20 mW g−1 are shown. These values span the range of measured recovery heat rates (Fig. 7A). The concentric circles (lower right) illustrate the fraction of the cross-section that would be anoxic during steady state activity giving rise to a recovery heat rate of 20 mW g−1. The outer circle represents the circumference of the cylinder and the black region is the potentially anoxic area. The anoxic region corresponds to 9% of the total cross-sectional area. The average radii of soleus and EDL muscles used at 35°C in this study were 0.37 ± 0.02 and 0.40 ± 0.02 mm; a radius of 0.4 mm was used for these calculations. Other data used in the calculations: PO2 at muscle surface, 100 kPa; diffusivity of O2, 2.39 × 10−5 cm2 atm−1 min−1 at 27°C (Mahler et al. 1985), adjusted to 35°C using a Q10 of 1.04 (Mahler, 1978); basal metabolic rate, 1.2 mW g−1 at 20°C (Crow & Kushmerick, 1982), Q10 = 1.3 (Mahler, 1978).

Net mechanical efficiency

Net mechanical efficiency was defined as the ratio of the total work produced during a series of 10 contractions (WTotal) to total, suprabasal enthalpy output associated with the series of contractions (ΔHNet; Fig. 2B). WTotal was calculated by summing the net work produced in each contraction cycle over all the contractions in a series. ΔHNet was calculated by adding WTotal to the heat produced, in excess of that due to resting metabolism, in response to the contraction series. The rate of heat production remained greater than the pre-contraction value for almost 1 min after the end of contractile activity at 35°C (Fig. 2B). All this heat, which can be attributed to oxidative reversal of PCr splitting (e.g. Leijendekker & Elzinga, 1990; Curtin et al. 1997; Lou et al. 2000), was included in the measured enthalpy output. ɛNet differs from ɛI in that the energy consumption term includes both initial and recovery metabolisms.

Thermodynamic efficiency of oxidative recovery

If both ɛI and ɛNet are known, then the efficiency of the oxidative recovery processes can be estimated. The net thermodynamic efficiency of muscle contraction (ηNet) is the product of the efficiency with which free energy of ATP hydrolysis (ΔGATP) is converted into work (i.e. the initial thermodynamic efficiency, ηI) and the efficiency with which free energy from metabolic substrates is transferred into ΔGATP (i.e. recovery thermodynamic efficiency, ηR) (Wilkie, 1974; Smith et al. 2004). The free energy change and enthalpy change for substrate oxidation are similar (∼2870 and 2810 kJ mol−1, respectively, for glucose oxidation) so ηNet is approximately equal to ɛNet. Therefore, ηR can be estimated as follows.

|

ηI can be estimated from ɛI knowing the ratio of the molar enthalpy of PCr hydrolysis (ΔHmPCr) to molar free energy of ATP hydrolysis (ΔGmATP).

|

Substituting eqn (3) into eqn (2),

|

At 35°C and pH 7, ΔHmPCr is ∼35 kJ mol−1 (Woledge & Reilly, 1988). ΔGmATP for mouse soleus and EDL muscles was calculated using reported intracellular concentrations of ATP, ADP and Pi (Kushmerick et al. 1993) and assuming that the standard free energy for ATP hydrolysis (ΔG0ATP) is 28 kJ mol−1 (at pH 7.0, 37°C, ionic strength 0.2, [Mg2+] 1 mm; Rosing & Slater, 1972); this calculation gave values of 63 and 58 kJ mol−1 for EDL and soleus muscles, respectively. The different ΔGmATP values arise from the different inorganic phosphate concentrations in fast and slow muscles.

In addition to calculating ηR, the ratio of the ΔHR to ΔHI (the ratio of recovery/initial enthalpy; R/I ratio) was also calculated from the values for ɛI and ɛNet. The basis of this calculation is that ɛNet is lower than ɛI by a factor equal to the amount of recovery metabolism produced.

|

Substituting R/I for ΔHR/ΔHI and rearranging eqn (5) gives the following.

|

Protocol for determining efficiency

To determine values of ɛI and ɛNet, each muscle performed 6–8 series of 10 contractions at contraction frequencies between 0.5 and 4.5 Hz (soleus) or 8 Hz (EDL). Contraction frequency was varied by altering the duration of the lengthening phase of the strain cycle only. Each contraction consisted of 10 stimulus pulses delivered at a frequency sufficient to produce a fused contraction (80 Hz for soleus and 160 Hz for EDL); the duration of stimulation in each cycle was 125 ms for soleus and 63 ms for EDL preparations.

This protocol provided a series of combinations of average power output and average rate of enthalpy output for each muscle preparation. ɛI and ɛNet were calculated from the slopes of the relationships between power output and rate of initial and net enthalpy output, respectively (Fig. 3). Power output and rate of enthalpy output, averaged over the entire protocol, were varied by varying contraction frequency (Josephson, 1985). Average power output was the product of the average work output per contraction and contraction frequency and average rate of enthalpy output was the product of enthalpy output per contraction and contraction frequency. ɛI and ɛNet were calculated as the inverse of the slope of a line fitted, by minimizing the sum of the squared deviations, through the rate of enthalpy output versus power output data (Fig. 3). Thus, for each muscle ɛI and ɛNet were determined using data from six to eight recordings.

Figure 3. Efficiency determined from relationship between power output and rate of enthalpy output.

For each muscle, the relationship between power output and rate of enthalpy output was determined by performing contraction protocols at a series of contraction frequencies. The data points on each line correspond to values determined from different contraction frequencies. Initial values (▪) refer to values measured at the start of a contraction series, when recovery metabolism contributed little to the enthalpy output (see Fig. 2A). Net values (□) refer to measurements made using all the work and suprabasal enthalpy produced during and after a series of contractions (see Fig. 2B). Average power output and average enthalpy output were calculated by multiplying the average work and enthalpy output per contraction by the contraction frequency. Straight lines were fitted through the data using linear regression and initial and net efficiency values were calculated by taking the inverse of the slopes of the lines for initial values and net values, respectively. The data shown are for a soleus muscle preparation. Contraction frequencies were between 0.5 and 4.5 Hz. ɛI for this example was 31% and ɛNet was 14%.

Effect of temperature on ɛI and ɛNet

Additional experiments were performed to establish the dependence of ɛI and ɛNet on temperature, contraction number and duration and the duration of the isometric phase. In these experiments, ɛNet was determined using a single series of 20 contractions under each condition tested. A contraction frequency (3.4 Hz), within the range of stride frequencies for trotting in the mouse (Clarke & Still, 1999), was used. For experiments at 20°C, the temperature used by Heglund & Cavagna (1987), cycle frequency was reduced to 1.2 Hz to accommodate the increased contraction duration at the lower temperature and stimulation frequencies were reduced to 50 and 100 Hz for soleus and EDL, respectively. The shortening velocity during the second phase of the strain cycle was also reduced (soleus, 0.4 ml s−1; EDL, 0.9 ml s−1; ∼20% maximal velocity (Vmax) at 20°C; Barclay et al. 1993) so that efficiency remained close to its maximum value.

Assessment of O2 diffusion into isolated muscles

The adequacy of diffusive O2 supply to the isolated muscles was assessed by calculating the profile of O2 partial pressure (PO2) through the cross-section of a cylindrical muscle. The analysis, which has been described in detail previously (Loiselle, 1985; Baxi et al. 2000; Barclay et al. 2003), was based on Hill's (1928) analysis of diffusion into a cylindrical muscle but, rather than assuming mitochondrial function to be independent of PO2, the analysis incorporated a more realistic, sigmoidal relationship between the rate of mitochondrial oxygen consumption and PO2 (slope = 3, PO2 at which mitochondrial rate is 50% maximal = 0.13 kPa; Wittenberg & Wittenberg, 1985). It was also assumed that muscles were uniform cylinders, metabolic rate was constant and diffusion of O2 into the ends of the cylinder was negligible.

The maximum rate of O2 consumption was calculated from the rate of enthalpy output measured immediately after the last contraction cycle. At this time, the energetically important biochemical reactions likely to be occurring are resynthesis of PCr, absorbing 35 kJ (mol PCr)−1, and substrate (i.e. glucose) oxidation, producing 460 kJ (mol O2)−1 (Woledge, 1971). Assuming a P/O2 ratio of 6.3, then during recovery the net enthalpy output is 460–(6.3 × 35) = 240 kJ (mol O2)−1 or ∼9 mJ (μl O2)−1. This value was used to convert recovery enthalpy rates to an equivalent O2 consumption.

The rate of recovery heat production was determined by differentiating the cumulative heat signal, low pass filtering the resulting heat rate signal (cut-off frequency 10 Hz, performed in the frequency domain: pp. 558–559, Press et al. 1998) and then fitting a single exponential curve through the postcontractile heat rate data using the Marquardt method (pp. 683–687, Press et al. 1998) (Fig. 4). The maximum rate of heat production and time constant for decline in rate of heat production were taken from the parameters of the fitted line. The maximum rate of recovery heat production was taken to be the value of the fitted curve at the end of the last strain cycle in a series.

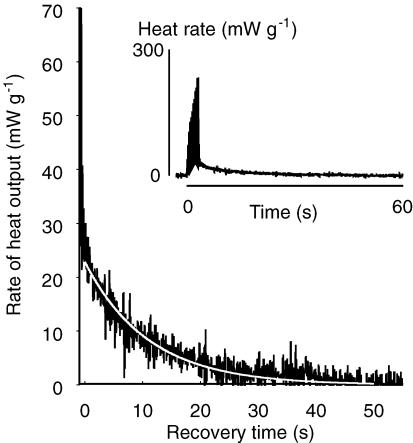

Figure 4. Example of time course of rate of recovery heat output.

Rate of heat output from a soleus preparation (black trace) following a series of 10 contractions at 3.5 Hz and at a temperature of 35°C. The time scale indicates the time elapsed since the end of the last contraction cycle. A single exponential curve was used to describe the time course of the change in recovery heat rate after the contractions ended (white line). In the example shown the rate of recovery heat immediately after the contraction series was 22.8 mW g−1 and the time constant of the decline was 12.1 s. The inset shows the rate of heat output during both the contraction protocol and subsequent recovery. During the contraction series, the peak rate of heat output was greater than that during recovery, reflecting the relatively high rate of initial heat production. Preparation mass, 3.59 mg; length, 10.3 mm.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

Efficiency values are expressed as percentages and all energetic variables are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Energetic variables were normalized by blotted, wet muscle mass. Student's t test was used to compare the slopes of enthalpy rate–power relationships, the values of ηR and R/I for EDL and soleus. A paired t test was used to analyse the influence on ɛNet of the duration of isometric phase. Analysis of variance was used to determine the effects on ɛNet of temperature, contraction number and contraction duration and to determine whether recovery kinetics depended on contraction frequency. All statistical decisions were made with respect to the 95% level of confidence.

Results

Efficiency of soleus and EDL muscles

Efficiency was determined from the relationship between rate of enthalpy output and power output (Fig. 3). Rate of enthalpy output depended linearly on mechanical power output (mean values of the square of the correlation coefficient > 0.9 for both muscles). Across most of the range of contraction frequencies used, power output and rate of enthalpy output increased with increasing contraction frequency. At the upper end of the frequency ranges used, power output sometimes decreased when contraction frequency was increased because the mean force output decreased. In these cases, rate of enthalpy output also declined, in proportion to the decline in power output, so efficiency was unaltered.

Power output–enthalpy rate relationships for both initial and net energy measurements were determined for six muscles of each type. The initial mechanical efficiency of soleus muscles was significantly greater than that of EDL muscles (30 ± 1% versus 23 ± 1%, respectively; Fig. 5). Note that the energy consumption term for this efficiency definition included not only the energy used during shortening but also that used for force development at the start of the contraction. Furthermore, during part of the shortening phase, muscles were being stimulated and for the remainder, force relaxation was occurring. These protocol characteristics most likely account for ɛI values being lower than those reported previously for these muscles, when energy output was measured only during shortening (Barclay, 1996).

Figure 5. Initial and net efficiencies of soleus and EDL.

Initial and net mechanical efficiencies were determined as illustrated in Fig. 2 using 6 muscles of each type. Initial mechanical efficiency of EDL muscles was significantly lower than that of soleus muscles. There was no significant difference in net efficiency between the two muscle types.

Net efficiency values included the energy costs of both initial and recovery processes. There was no significant difference in the values of ɛNet from the fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscles (Fig. 5, Table 1). Mean ɛNet values were 12.6 and 11.7%, for soleus and EDL, respectively. That is, about 88% of the energy used by both muscles was converted into heat. The thermodynamic efficiency of oxidative recovery was calculated for each muscle using that muscle's ɛI and ɛNet values (eqn (4)). The mean value of ηR for soleus muscles was 72 ± 4%, which was significantly lower than the value of 86 ± 3% calculated for EDL muscles. The R/I ratios, also calculated from ɛI and ɛNet (eqn (6)), were 1.3 ± 0.1 and 1.00 ± 0.07 for soleus and EDL muscles, respectively. These values differed significantly.

Table 1.

Efficiency of soleus and EDL muscles

| 35°C | 20°C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soleus (n = 6) | EDL (n = 6) | Soleus (n = 11) | EDL (n = 11) | |

| Initial efficiency (%) | 30 ± 1 | 23 ± 1* | 25 ± 1 | 19.2 ± 0.7* |

| Net efficiency (%) | 12.6 ± 0.7 | 11.7 ± 0.5 | 12.5 ± 0.9 | 11.0 ± 0.6 |

| Recovery efficiency (%) | 72 ± 4 | 86 ± 3* | ||

| R/I ratio | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.00 ± 0.07* | ||

Differs significantly from value for soleus (P < 0.05).

The values of the various measures of efficiency for soleus and EDL muscles are summarized in Table 1. The finding that the initial efficiency of soleus muscles was greater than that of EDL but that there was no difference in net efficiency is consistent with the idea that each unit of initial metabolism was associated with more recovery metabolism in the slow muscle than the fast muscle; hence, the R/I ratio was greater for soleus. That idea is, in turn, consistent with efficiency of the recovery processes being lower in the slow-twitch muscle compared to the fast-twitch muscle.

Effect of temperature on efficiency

The independence of net efficiency from fibre type differs from the observation of Heglund & Cavagna (1987) who found rat EDL muscle to be more efficient than soleus. One difference between that study and the current one was that the earlier study used a temperature of 20°C whereas 35°C was used in the current study. To see whether this affected the relative efficiencies of fast and slow muscles, ɛI and ɛNet of mouse EDL and soleus preparations were determined at 20°C. The results (Table 1) were similar to those at 35°C: ɛI of soleus was greater than that of EDL and yet ɛNet did not differ between the two muscles. Furthermore, ɛNet was not significantly altered by increasing the number of stimulus pulses per contraction from 10 to 20 or by increasing the number of contractions from 20 to 40.

Did the duration of the isometric phase affect the efficiency?

During the isometric phase at the start of each contraction, muscles used energy but performed no work. To find out whether the duration of the isometric phase affected either the absolute efficiency or the relative efficiencies of soleus and EDL muscles, ɛNet was measured using either the standard phase 1 duration (EDL, 30 ms; soleus, 50 ms) or half the standard duration (EDL, 15 ms; soleus, 25 ms) (Fig. 6A). When the duration of the isometric phase was reduced, the work output from both muscle types was reduced because the brief isometric period restricted the level to which force output increased before the start of shortening. The net enthalpy output was also reduced and in proportion to the decrease in work output so, for the isometric durations tested, there was no significant effect of duration of the isometric phase on ɛNet (Fig. 6B). In addition, there was no significant effect of duration of the isometric phase on ɛI for either muscle: the mean difference in ɛI between short and long isometric phases was 0.38 ± 0.6% for EDL and 0.1 ± 0.1% for soleus (n = 4 of each type of muscle).

Figure 6. Effect of isometric duration on ɛNet.

A, the duration of the isometric phase at the start of each contraction cycle was varied to determine whether it affected ɛNet. The example shows force records from a soleus with isometric durations of 25 ms (dashed line) and 50 ms (continuous line). Peak force and shortening were reduced when the isometric duration was shorter. B, ɛNet values for soleus (open symbols) and EDL (filled symbols) with different isometric durations. Different symbols represent data from different preparations and lines join the points for the same preparation at different isometric durations. Isometric durations were 15 and 25 ms for EDL and 25 and 50 ms for soleus preparations. There was no significant effect, for either muscle, of isometric duration of ɛNet.

Kinetics of recovery metabolism

The magnitude of the rate of heat production immediately after the final contraction cycle and the time constant for its subsequent decline were measured. The time constants (Fig. 7A) for the decline in rate of recovery heat were between 5 and 15 s. The values did not differ significantly between soleus and EDL, over the range of contraction frequencies that both muscles performed, nor did they vary significantly with contraction frequency. The mean time constants, averaged over all the contraction frequencies used, were 10.9 ± 0.5 s for soleus (47 measurements from 6 preparations) and 9.1 ± 0.6 s for EDL (54 measurements from 6 preparations).

In Fig. 7B, the magnitude of recovery heat output at the end of the contraction series is shown. Note these values are not the maximum rates of recovery heat output that could be attained at each frequency nor are they steady state values. The durations of the contraction series were too brief for an energetic steady state to be attained. For example, if it is assumed that at the start of contractile activity the rate of recovery heat increased with a time course similar to that for its decline at the end of the contraction protocol, then at the lowest frequency used (0.5 Hz), recovery heat rate would have required ∼4 × 12 s = 48 s to reach a steady value. However, the contraction protocol lasted only 20 s. At the highest frequencies used, soleus muscles contracted for 2.5 s and EDL muscles for 1.25 s. So, an energetic steady state would not have been reached within the time of the contractions and the maximum rates of recovery metabolism measured were attained only briefly. The importance of these values was that they were used to estimate the maximum rate of O2 consumption for each protocol to allow an assessment of the adequacy of O2 supply to the isolated muscles (see Discussion).

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that, despite the initial efficiency being greater in slow-twitch soleus than in fast-twitch EDL muscles, there was no difference in the net efficiency of the two muscle types. The distinct fibre-type dependences of ɛI and ɛNet is indicative of a difference in the efficiency of the oxidative recovery processes. It was calculated that the efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation was 14% lower in mouse soleus than in EDL. One conclusion that can be drawn from these findings is that initial efficiency does not necessarily provide a good indication of likely net efficiency. A second conclusion is that the relationship between initial energy use and recovery metabolism appears to be different in mouse soleus and EDL. Before discussing these points, it is important to assess the likely oxygenation of the preparations, which is particularly relevant because most of the experiments were performed at a relatively high temperature for isolated muscle studies. This was done so that muscle energetics could be studied under conditions as close as possible to in vivo conditions. Both metabolic rate and O2 diffusivity increase with temperature but metabolic rate is more temperature sensitive than O2 diffusivity (Mahler, 1978) so the likelihood of developing an anoxic region in the core of an isolated preparation increases with temperature.

Adequacy of diffusive O2 supply

To assess the likely adequacy of oxygenation, the intramuscular PO2 profile was estimated by modelling diffusive O2 supply. At rest, muscle O2 consumption is low relative to that during activity and the estimated PO2 profile indicates that diffusive O2 supply was adequate to support resting metabolism (upper line, Fig. 8). The measured recovery heat rates (Fig. 7B) corresponded to O2 uptake rates ∼20-fold greater than the resting rates. The analysis indicates that under steady state conditions, active muscles would be likely to develop an anoxic centre. However, for a recovery heat rate of 20 mW g−1, the anoxic region would correspond to only ∼10% of the total muscle cross-section (Fig. 8). This is an overestimate of what would have happened during the protocols used in this study because, as described in Results, even the lowest contraction frequency protocol (0.5 Hz) was too brief for the rate of O2 uptake to reach a steady state. Given that the muscles started from a well-oxygenated state and would have progressed towards, but not reached, an energetic steady-steady state, it is unlikely that intracellular PO2 would have fallen sufficiently for an anoxic core to develop. However, as an additional test of whether muscle efficiency may have been affected by O2 supply, the relationship between ɛNet and muscle radius was investigated. There was no significant relationship between these variables: for neither soleus nor EDL did the slope of a line fitted through the data differ significantly from zero. Therefore, muscle size, and thus presumably diffusive O2 supply, did not affect net efficiency values.

Efficiency of fast and slow muscle

This is the first study to measure both initial and net efficiency in the same set of contractions and is thus the first time that the combination of different ɛI values and the same ɛNet values has been described. The independence of ɛNet from fibre type differs from the findings of both previous reports of ɛNet values for fast and slow mammalian muscles. However, in the studies by Gibbs and colleagues (Gibbs & Gibson, 1972; Wendt & Gibbs, 1973), who found ɛNet to be greater for rat soleus muscles than EDL muscles, determination of maximum efficiency values was not the primary aim and no attempt was made to optimize the contraction protocols to determine the maximum ɛNet (C. L. Gibbs, personal communication). It was, however, apparent that the ɛNet of EDL could be increased substantially by reducing tetanus duration, providing a hint that the difference in maximum ɛNet of soleus and EDL may not have been great. Heglund & Cavagna (1987) found ɛNet of rat EDL (19%) to be greater than that for soleus (15%). However, there was considerable variation in the efficiency values, particularly for EDL muscles. For example, at shortening velocities between 20 and 30% Vmax, where efficiency was highest, ɛNet for EDL ranged between 10 and 25%. As no statistical analysis was presented for those data, it is difficult to conclude that there really was a difference in ɛNet between the two muscles. For comparison, ɛNet values for mouse EDL in this study, determined from the slopes of enthalpy rate–power relationships, ranged from 10.4 to 13.2%. In summary, the previous evidence did not provide strong support for the idea that ɛNet was fibre type dependent and the current study provides the clearest evidence that net efficiency differs little with fibre type, despite initial efficiency being higher in the slow-twitch muscle.

It is interesting to contrast the similarity of the net efficiency of fast and slow muscles with the great difference in the rate of energy expenditure during isometric contraction (i.e. the economy of contraction). Slow-twitch muscles use energy at rates that are typically 20–40% of the rate at which a corresponding fast-twitch muscle uses energy both when contracting isometrically and when shortening at either comparable relative or absolute shortening velocities (Gibbs & Gibson, 1972; Wendt & Gibbs, 1973; Crow & Kushmerick, 1982; Heglund & Cavagna, 1987; Barclay et al. 1993; Barclay, 1994, 1996; Reggiani et al. 1997; He et al. 2000). Therefore, in protocols involving shortening, such as those used in this study, slow-twitch muscles use energy at a lower rate than fast-twitch muscles but both convert the same fraction of the energy used into mechanical work. This suggests that the functionally important feature of slow-twitch muscles is not their efficiency but rather their economy or moderate absolute rate of energy use.

Efficiency was found to be independent of the duration of the isometric phase. Although this may seem surprising, it is likely that the effects of isometric duration on efficiency are small because the rates of energy output during isometric and shortening contraction differ greatly. For example, the rate of initial enthalpy output from mouse soleus and EDL muscles during shortening at the velocity at which efficiency is maximal is 2- to 3-fold greater than that during isometric contraction (Barclay, 1996). In the current protocols, the isometric phase occupied ∼25% of the time during which the muscles actively developed force (i.e. from the start of stimulation until complete force relaxation). Using a conservative estimate that the rate of enthalpy output during shortening was twice that during the isometric phase and ignoring recovery heat production, then the enthalpy output during the isometric phase would be 25/(25 + (2 × 75)) ≈ 15% of the total enthalpy output while contracting. Reducing that component by half, by reducing the isometric duration, would reduce the total energy output by 6%, which would result in a change in net efficiency of less than 0.9%. Including the ongoing recovery heat output would further reduce the expected difference in efficiency with isometric duration; such a small difference would be difficult to detect. Furthermore, when the isometric duration was reduced, shortening force was lower. It is not possible, using the data from the current study, to determine whether the lower force per se affected efficiency, and if so in what manner.

Energetics of recovery processes

The processes that account for the different fibre type dependence of ɛI and ɛNet are those involved in reversing the chemical changes that occur during contraction. In both soleus and EDL, under aerobic conditions and with moderate activity levels, metabolic recovery is almost exclusively due to oxidative metabolism (Crow & Kushmerick, 1982; Leijendekker & Elzinga, 1990). The expected R/I ratio can be estimated on the basis that PCr breakdown underlies the initial enthalpy output and the recovery process is fuelled by glucose oxidation. Intracellular pH of resting mouse muscle in bicarbonate-buffered saline at 35°C is close to 7 (Aickin & Thomas, 1977) so ΔHmPCr is 35 kJ mol−1 (Woledge & Reilly, 1988). If it is assumed that each mole of O2 consumed produces 460 kJ and the P/O2 ratio is 6.5 (i.e. 39 ATP are produced for 6 mol of O2 used; for a discussion of this stoichiometry, see Kushmerick, 1978), then (Woledge, 1971),

|

This is the value estimated in this study for mouse EDL but is lower than that for soleus (Table 1). The R/I ratio has been estimated for fast- and slow-twitch muscles in two previous studies. Wendt & Gibbs (1976) used pharmacological agents to block oxidative and glycolytic recovery in rat EDL and soleus. They found R/I of soleus to be 1.3 but were less certain about the value for EDL. They estimated that R/I for EDL was likely to be slightly less than 1. Leijendekker & Elzinga (1990), using mouse EDL and soleus, found values of 0.95 and 1.54, respectively. The relative values for EDL and soleus from both those studies and the current study (Table 1) are consistent: R/I for EDL is close to 1 and that for soleus 30–50% higher.

The R/I ratio does not necessarily reflect only the metabolic processes occurring in the recovering muscle. Because R/I depends on ΔHmPCr, its value can be affected by changes in intracellular composition that alter ΔHmPCr. In particular, ΔHmPCris very sensitive to pH (Woledge & Reilly, 1988). For example, if intracellular pH were assumed to be 7.1 (Kushmerick et al. 1983) instead of 7 (Aickin & Thomas, 1977), then ΔHmPCr ≈ 36 kJ mol−1 and the theoretical R/I would be reduced to 0.97. Transient changes in intracellular pH can occur during contraction and recovery. During moderate activity, muscle cells become more alkaline during contractile activity and more acidic during recovery (Kushmerick et al. 1983). During more vigorous activity, intracellular pH may decrease while a muscle is active and then slowly return to resting levels during recovery (Juel, 1988). This can potentially affect R/I because the ΔHmPCrterm in the numerator of eqn (7) refers to its value during recovery whereas that in the denominator is the value during contraction. The intracellular pH in fast-twitch cat muscle, but not slow-twitch, is relatively stable during and after moderate activity (Kushmerick et al. 1983). If this also applies to mouse EDL muscle, then there are unlikely to be differences in ΔHmPCr between the contraction and recovery periods due to pH changes. Thus, the recovery energy use by EDL muscles is consistent with expectations based on complete oxidative reversal of PCr used during the contraction series.

R/I for soleus muscle was higher than the expected value. It is unlikely that this is due to an effect of pH on ΔHmPCr. For example, if ΔHmPCr was constant during the contraction protocol and recovery, then for R/I to be 1.3 ΔHmPCr would have to be 31 kJ mol−1. This is the probable value when pH is 6.7, which is unlikely in rested muscle but could possibly occur in response to contractile activity (Juel, 1988). If, as described by Kushmerick et al. (1983), intracellular pH increased during contraction and then decreased during recovery, R/I would be lower than the expected value, not higher. On the other hand, if intracellular pH was lower on average during recovery than during the contractile activity, then R/I would be greater than the expected value. However, to take an extreme case, even if pH was 6.5 throughout recovery and 7 during the contractions, then R/I would only increase to 1.16, still much lower than the measured value.

If R/I for soleus is not due to alterations in ΔHmPCr, then it is possible that the P/O2 ratio really is less than 6.5 in soleus. If ηR is 74% (Table 1), then the number of ATP molecules produced per glucose is:

(cf. 39 for EDL). That is, the characteristics of recovery in soleus are consistent with fewer ATP being produced per glucose molecule oxidized. There are some reports that are consistent with mouse muscles using more O2 during contractile activity than is required simply to regenerate PCr; the extra O2 consumption is thought to be related to mitochondrial proton cycling (Rolfe et al. 1999). However, a previous comparison of the extent of chemical breakdown and amount of O2 consumed by mouse soleus found values consistent with a P/O2 ratio of ∼6.3 (Crow & Kushmerick, 1982), which is not consistent with the relatively low ηR value calculated for soleus. One difference between Crow & Kushmerick's study and the current one is that in the former case no exogenous substrate was provided. The effects of exogenous substrate on isolated skeletal muscle metabolism have not been well characterized so it is not known whether the provision of glucose affects the R/I ratio. However, comparison with cardiac muscle suggests that the substrate provided can affect both the amount and the kinetics of recovery metabolism (Chapman & Gibbs, 1974). Further insight into the differences in recovery metabolism of soleus and EDL may be gained by manipulating substrate provision.

Another process that could potentially affect R/I is the interaction of Ca2+ with parvalbumin. Parvalbumin is a myoplasmic Ca2+ buffer, present in mouse EDL but not soleus (Heizman et al. 1982), that binds Ca2+ when intracellular Ca2+ levels are high (an exothermic reaction) and releases Ca2+ relatively slowly when intracellular Ca2+ levels fall once contractile activity ends. There is a net absorption of energy associated with Ca2+−parvalbumin dissociation and return of Ca2+ to the sarcoplasmic reticulum. An estimate can be made of the how much the Ca2+−parvalbumin energy exchanges could affect R/I values. The following data, mostly obtained from frog parvalbumin, were used for this estimate. The concentration of parvalbumin in mouse EDL is 0.4 mm (Heizman et al. 1982), there are 2 Ca2+ binding sites per molecule, 40% of sites have Ca2+ bound at rest (Hou et al. 1991), the enthalpy output for Ca2+−Mg2+ exchange on parvalbumin is 33 kJ mol−1 (Smith & Woledge, 1985) and 2 Ca2+ are pumped into the SR for each ATP used. The total enthalpy output from Ca2+−parvalbumin interactions, assuming all the possible sites were filled just once, would be 0.6 × 0.8 mmol l−1 × 33 J mmol−1 = 15 mJ g−1. During recovery, the same amount of energy would be absorbed when Ca2+ dissociated and PCr splitting would produce 0.6 × 0.8 mmol l−1 × 0.5 × 33 J mmol−1 = 8 mJ g−1. The net enthalpy change during recovery would thus be absorption of 15–8 = 7 mJ g−1. The total amounts of initial and recovery energy produced by EDL were typically ∼250 mJ g−1 so Ca2+−parvalbumin interactions may have accounted for ∼6% of initial enthalpy and could have reduced recovery enthalpy output by ∼3%. If these contributions were removed to get an estimate of enthalpy output due to metabolic reactions only, then the calculated R/I = 1 would be reduced only slightly, to 0.97. Thus, it seems that the presence of parvalbumin can neither greatly affect the R/I value for EDL nor account for the different R/I values for soleus and EDL.

Finally, it is interesting to note that the R/I ratio is also increased in mouse soleus muscle when mitochondrial uncoupling protein-3 (UCP-3) is overexpressed (Curtin et al. 2002). Although neither the exact physiological role nor the mechanism of action of UCP-3 are clear, UCP-3 does appear to be involved in metabolism of fatty acids but probably not carbohydrates (e.g. Moore et al. 2001). It is possible that UCP-3 activity differs between mouse EDL and soleus in vitro with glucose provided as an exogenous substrate. Comparison of R/I ratios of both muscles in the presence of either carbohydrate or fats may provide some insight into the possible role that UCP-3 plays in modulating R/I ratios in mouse skeletal muscle.

Implications for energetics of exercise

The idea that the net efficiency of fast and slow muscles is the same has interesting implications for not only for muscle energetics but also for energetics of exercise. In relation to the former, it has been proposed that the progressive increase in rate of oxygen consumption observed in humans working at a constant workload reflects recruitment of motor units containing less efficient fast-twitch muscle fibres (e.g. Whipp, 1994). Also, people with a greater percentage of slow-twitch muscle fibres are more efficient when cycling at a fixed pedal frequency of 80 r.p.m. (Coyle et al. 1992). If the current results are applicable to human muscle, then both these observations would be unlikely to reflect an inherent difference in maximum efficiency among fibre types but rather are more likely to arise because the mechanical conditions typically used in cycling ergometry allow slow-twitch muscles to function closer to their maximum efficiency than can fast-twitch motor units (Coyle et al. 1992).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the observation that net efficiency, but not initial efficiency, is independent of fibre type indicates that there are differences between fibre types in the coupling of oxidative recovery metabolism to initial metabolism. The differences in R/I between EDL and soleus cannot be explained by differences in intracellular pH, by likely changes in pH during contraction and recovery or by the presence of parvalbumin in EDL muscles. It is possible that slow-twitch mouse soleus produces fewer ATP for each molecule of substrate consumed than the fast-twitch EDL muscle. It is also interesting that for soleus there does not appear to be any overall energetic benefit due to its relatively high initial efficiency. It may be that the greater initial efficiency of slow muscles is simply a consequence of slower cross-bridge cycling which underpins the low rate of energy use that characterizes slow-twitch muscles (Barclay et al. 1993). In that case, low rate of energy use rather than high efficiency may be the functionally important feature of muscles that work for protracted periods.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Griffith University Heart Foundation Research Grant and Griffith University Research Grant.

References

- Aickin CC, Thomas RC. An investigation of the ionic mechanism of intracellular pH regulation in mouse soleus muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1977;273:295–316. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardevol A, Adan C, Remesar X, Fernandez-Lopez JA, Alemany M. Hind leg heat balance in obese Zucker rats during exercise. Pflugers Arch. 1998;435:454–464. doi: 10.1007/s004240050539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay CJ. Efficiency of fast- and slow-twitch muscles of the mouse performing cyclic contractions. J Exp Biol. 1994;193:65–78. doi: 10.1242/jeb.193.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay CJ. Mechanical efficiency and fatigue of fast and slow muscles of the mouse. J Physiol. 1996;497:781–794. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay CJ. Models in which many cross-bridges attach simultaneously can explain the filament movement per ATP split during muscle contraction. Int J Biol Macromol. 2003;32:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(03)00047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay CJ, Arnold PD, Gibbs CL. Fatigue and heat production in repeated contractions of mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1995;488:741–752. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay CJ, Constable JK, Gibbs CL. Energetics of fast- and slow-twitch muscles of the mouse. J Physiol. 1993;472:61–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay CJ, Widen C, Mellors LJ. Initial mechanical efficiency of isolated cardiac muscle. J Exp Biol. 2003;206:2725–2732. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxi J, Barclay CJ, Gibbs CL. Energetics of rat papillary muscle during contractions with sinusoidal length changes. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:H1545–H1554. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.5.H1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JB, Gibbs CL. The effect of metabolic substrate on mechanical activity and heat production in papillary muscle. Cardiovasc Res. 1974;8:656–667. doi: 10.1093/cvr/8.5.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KA, Still J. Gait analysis in the mouse. Physiol Behav. 1999;66:723–729. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close R. Force: velocity properties of mouse muscles. Nature. 1965;206:718–719. doi: 10.1038/206718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle EF, Sidossis LS, Horowitz JF, Beltz JD. Cycling efficiency is related to the percentage of type I muscle fibers. Med Sci Sports Ex. 1992;24:782–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow MT, Kushmerick MJ. Chemical energetics of slow- and fast-twitch muscles of the mouse. J General Physiol. 1982;79:147–166. doi: 10.1085/jgp.79.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin NA, Clapham JC, Barclay CJ. Excess recovery heat production by isolated muscles from mice overexpressing uncoupling protein-3. J Physiol. 2002;542:231–235. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin NA, Kushmerick MJ, Wiseman RW, Woledge RC. Recovery after contraction of white muscle fibres from the dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula. J Exp Biol. 1997;200:1061–1071. doi: 10.1242/jeb.200.7.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs CL, Gibson WR. Energy production of rat soleus muscle. Am J Physiol. 1972;223:864–871. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.223.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He ZH, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA, Ferenczi MA, Reggiani C. ATP consumption and efficiency of human single muscle fibers with different myosin isoform composition. Biophys J. 2000;79:945–961. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76349-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He ZH, Chillingworth RK, Brune M, Corrie JE, Webb MR, Ferenczi MA. The efficiency of contraction in rabbit skeletal muscle fibres, determined from the rate of release of inorganic phosphate. J Physiol. 1999;517:839–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0839s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heglund NC, Cavagna GA. Mechanical work, oxygen consumption, and efficiency in isolated frog and rat muscle. Am J Physiol. 1987;223:C22–C29. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.1.C22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heizman CW, Berchtold MW, Rowlerson AM. Correlation of parvalbumin concentration with relaxation speed in mammalian muscles. Proc Natl Acad Sciusa. 1982;79:7243–7247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.23.7243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AV. The diffusion of oxygen and lactic acid through tissue. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1928;104:39–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hill AV. Methods of analysing the heat production of muscle. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1937;124:114–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hill AV. The mechanical efficiency of frog muscle. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1939;127:434–451. [Google Scholar]

- Hill AV. The efficiency of mechanical power development during muscular shortening and its relation to load. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1964;159:319–324. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1964.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou TT, Johnson JD, Rall JA. Parvalbumin content and Ca2+ and Mg2+ dissociation rates correlated with changes in relaxation rate of frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1991;441:285–304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson RK. Mechanical power output from striated muscle during cyclic contraction. J Exp Biol. 1985;114:493–512. [Google Scholar]

- Juel C. Intracellular pH recovery and lactate efflux in mouse soleus muscles stimulated in vitro: the involvement of sodium/proton exchange and a lactate carrier. Acta Physiol Scand. 1988;132:363–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1988.tb08340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar KM, Wilkie DR. A new method for absolute heat measurement, utilizing the Peltier effect. J Physiol. 1972;224:18P–21P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick MJ. Energy balance in muscle contraction: a biochemical approach. Curr Topics Bioeng. 1978;6:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick MJ, Meyer RA, Brown TR. Phosphorus NMR spectroscopy of cat biceps and soleus muscles. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1983;159:303–325. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-7790-0_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushmerick MJ, Moerland TS, Wiseman RW. Two classes of mammalian skeletal muscle fibres distinguished by metabolite content. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1993;332:749–760. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2872-2_66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leijendekker WJ, Elzinga G. Metabolic recovery of mouse extensor digitorum longus and soleus muscle. Pflugers Arch. 1990;416:22–27. doi: 10.1007/BF00370217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiselle DS. A theoretical analysis of the rate of resting metabolism of isolated papillary muscle. Adv Myocardiol. 1985;6:205–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou F, Van der Laarse WJ, Curtin NA, Woledge RC. Heat production and oxygen consumption during metabolic recovery of white muscle fibres from the dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula. J Exp Biol. 2000;203:1201–1210. doi: 10.1242/jeb.203.7.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luff AR, Atwood HL. Changes in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and transverse tubular system of fast and slow skeletal muscles of the mouse during postnatal development. J Cell Biol. 1971;51:369–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch GS, Cuffe SA, Plant DR, Gregorevic P. IGF-I treatment improves the functional properties of fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscles from dystrophic mice. Neuromusc Dis. 2001;11:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler M. Diffusion and consumption of oxygen in the resting frog sartorius muscle. J General Physiol. 1978;71:533–557. doi: 10.1085/jgp.71.5.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler M, Louy C, Homsher E, Peskoff A. Reappraisal of diffusion, solubility, and consumption of oxygen in frog skeletal muscle, with applications to muscle energy balance. J General Physiol. 1985;86:105–134. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellors LJ, Gibbs CL, Barclay CJ. Comparison of the efficiency of rat papillary muscles during afterloaded isotonic contractions and contractions with sinusoidal length changes. J Exp Biol. 2001;204:1765–1774. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.10.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GB, Himms-Hagen J, Harper ME, Clapham JC. Overexpression of UCP-3 in skeletal muscle of mice results in increased expression of mitochondrial thioesterase mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2001;283:785–790. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulieri LA, Luhr G, Trefrey J, Alpert NR. Metal film thermopiles for use with rabbit right ventricular papillary muscles. Am J Physiol. 1972;233:C146–C156. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1977.233.5.C146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul RJ. Comparison of physical and biochemical energy balances: chemical breakdown, heat production, and oxygen consumption in frog sartorius muscle. Fed Proc. 1982;41:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press WH, Flannery BP, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT. Numerical Recipes in C. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reggiani C, Potma EJ, Bottinelli R, Canepari M, Pellegrino MA, Stienen GJM. Chemo-mechanical energy transduction in relation to myosin isoform composition in skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. J Physiol. 1997;502:449–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.449bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe DFS, Newman JMB, Buckingham JA, Clark MG, Brand MD. Contribution of mitochondrial proton leak to respiration rate in working skeletal muscle and liver and to SMR. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C692–C699. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.3.C692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosing J, Slater EC. The value of ΔGo for the hydrolysis of ATP. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;267:275–290. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NP, Barclay CJ, Loiselle DS. The efficiency of muscle contraction. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.11.014. 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SJ, Woledge RC. Thermodynamic analysis of calcium binding to frog parvalbumin. J Mus Res Cell Motil. 1985;6:757–768. doi: 10.1007/BF00712240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt IR, Gibbs CL. Energy production of rat extensor digitorum longus muscle. Am J Physiol. 1973;224:1081–1086. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.224.5.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt IR, Gibbs CL. Recovery heat production of mammalian fast- and slow-twitch muscles. Am J Physiol. 1976;230:637–643. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.6.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipp BJ. The slow component of O2 uptake kinetics during heavy exercise. Med Sci Sports Ex. 1994;26:1319–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie DR. The efficiency of muscular contraction. J Mechanochem Cell Motil. 1974;2:257–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg BA, Wittenberg JB. Oxygen pressure gradients in isolated cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:6548–6554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woledge RC. The energetics of tortoise muscle. J Physiol. 1968;197:685–707. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woledge RC. Heat production and chemical change in muscle. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1971;22:39–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woledge RC, Reilly PJ. Molar enthalpy change for hydrolysis of phosphorylcreatine under conditions in muscle cells. Biophys J. 1988;54:97–104. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)82934-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woledge RC, Wilson MG, Howarth JV, Elzinga G, Kometani K. The energetics of work and heat production by single muscle fibres from the frog. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;226:677–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]