Abstract

There is a rapid increase in blood flow to active skeletal muscle with the onset of exercise, but the mechanism(s) eliciting this increase remains elusive. We hypothesized that the rapid increase in blood flow to active skeletal muscle with the onset of exercise is attributable to vasodilatation as a consequence of smooth muscle hyperpolarization. To test this hypothesis we examined the blood flow response to a brief tetanic contraction in which potassium (K+) was infused intra-arterially to elevate the [K+]o and clamp the smooth muscle membrane potential within the skeletal muscle vascular bed. In six anaesthetized beagle dogs control contractions increased hindlimb blood flow by 97 ± 14 ml min−1. During K+ infusion the hyperaemic response to contraction was 8 ± 3 ml min−1. Since the hindlimb blood flow was reduced during K+ infusion, a similar reduction in baseline blood flow was produced with phenylephrine infusion. During phenylephrine infusion the hyperaemic response to contraction was preserved (89 ± 23 ml min−1). Recovery contractions performed after the discontinuation of the K+ infusion elicited blood flow responses similar to control (100 ± 11 ml min−1). In a separate experimental protocol using the isolated gastrocnemius muscle of mongrel dogs (n = 6) K+ infusion did not alter force production by the skeletal muscle. Our data indicate that in the absence of vasodilatation, there is virtually no change in blood flow. One implication of this finding is that the muscle pump cannot be responsible for the initial contraction-induced hyperaemia. We conclude that the increase in blood flow immediately following a single muscle contraction is due to vasodilatation, presumably as a consequence of smooth muscle hyperpolarization.

There is an immediate increase in blood flow to active skeletal muscle with the onset of exercise (Corcondilas et al. 1964; Lind & Williams, 1979; Leyk et al. 1994; Tschakovsky et al. 1996; Shoemaker et al. 1998; Naik et al. 1999; Valic et al. 2002). Whether this initial blood flow response represents vasodilatation is not known. Studies employing in situ and in vitro techniques have suggested that the vascular response to contraction (Gorczynski et al. 1978; Jacobs & Segal, 2000) or to topical application of vasodilator agents (Wunsch et al. 2000) is too slow for vasodilatation to play a role in the initial active hyperaemia. Some researchers have used these observations as evidence that instantaneous activation of the skeletal muscle pump must account for the initial increase in blood flow (Sheriff et al. 1993). Although the muscle pump is an inviting explanation for the rapid increase in blood flow following muscle contraction, recent data from our laboratory do not support the muscle pump hypothesis (Hamann et al. 2003). Our perspective is that the rapid increase in blood flow observed in in vivo models is attributable to vasodilatation as a consequence of smooth muscle hyperpolarization. We reasoned that preventing changes in vascular smooth muscle membrane potential would permit assessment of the role of vasodilatation in the immediate change in blood flow following contraction.

To accomplish this, we have adapted an established model for clamping membrane potential in isolated in vitro vessels (Ishizaka & Kuo, 1997; Miura & Gutterman, 1998; Nishikawa et al. 1999; Woodman et al. 2000). This experimental model clamps the membrane potential of isolated vessels by elevating the external potassium concentration ([K+]o). Although this approach has been widely used in vitro, to our knowledge, this approach has never been applied to in vivo studies. Thus, we examined the blood flow response to a brief tetanic contraction in which potassium (K+) was infused intra-arterially to elevate the [K+]o which we assumed would clamp the smooth muscle membrane potential within the skeletal muscle vascular bed. These experiments tested the hypothesis that vasodilatation can occur rapidly due to smooth muscle hyperpolarization following skeletal muscle contraction.

Methods

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the American Physiological Society's Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals. Six purpose-bred beagle dogs (9–13 kg) and six mongrel dogs (17–23 kg) of either sex were studied under separate experimental protocols. For both protocols, each animal was obtained following an overnight fast. Anaesthesia was induced with 100 mg kg−1α-chloralose and 500 mg kg−1 urethane i.v. and a deep surgical plane of anaesthesia maintained with a constant infusion of 20 mg kg−1 h−1α-chloralose and 100 mg kg−1 h−1 urethane. The animals were intubated with a cuffed endotracheal tube and ventilated with room air using a mechanical ventilator (Harvard Apparatus, Dover, MA, USA). End-tidal CO2 was measured with an infrared analyser (Ohmeda, Miami, FL, USA) and adjusted to 35–40 mmHg by alterations in respiratory frequency. Core temperature was measured with a rectal thermometer and maintained at ∼37°C with a heating pad placed under the animal. Arterial blood pressure was measured using a cannula inserted retrogradely into the lumen of the carotid artery and attached to a solid-state pressure transducer (Ohmeda). All dogs were humanely killed with an overdose of potassium chloride at the end of the experiments.

Protocol I: beagles (n = 6)

This protocol was designed to determine whether clamping the membrane potential of vascular smooth muscle of skeletal muscle attenuates the hyperaemic response to contraction.

Hindlimb blood flow was measured using transit-time ultrasound flow probes (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY, USA) placed around the external iliac arteries approximately 1–2 cm below the terminal aorta. A catheter in a side branch of one femoral artery provided a site for intra-arterial drug infusion (K+ and phenylephrine). Following instrumentation, the dogs were placed in the prone position in a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL, USA). The torso was suspended through caudal tension applied via a hip-pin clamp. With the dog in the stereotaxic frame, the hindlimb was positioned below heart level. In order to prevent movement during contraction, the hindlimb was secured to the stereotaxic platform, so that all contractions would be isometric. The sciatic nerve was exposed unilaterally and cut. Two stimulating electrodes were wrapped around the nerve for stimulation. The minimum current required to elicit a visible contraction was defined as the motor threshold. The sciatic nerve was stimulated (2 ms duration, 30 Hz frequency) for 1 s at 10 × motor threshold to produce a brief tetanic contraction of the left hindlimb muscles. Just prior to initiation of the experimental protocol, arterial blood samples were taken for the measurement of blood gases and pH (Radiometer ABL520, Copenhagen). When these values were within normal limits, the experiment commenced. If necessary, metabolic acidosis was corrected with intravenous infusion of sodium bicarbonate.

Following a control contraction, each dog received, in random order, a potassium chloride (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) solution containing 100 mg ml−1 K+, or a phenylephrine (α1 adrenergic agonist) solution containing 10 μg ml−1 infused into the femoral artery. Potassium was infused at a constant rate to produce an estimated [K+]o of ∼40 mm. It was determined from preliminary experiments that an arterial [K+] of ∼40 mm reduced blood flow 50% from baseline, so phenylephrine was infused at a concentration that also resulted in a 50% reduction in baseline blood flow. When blood flow stabilized to the infusion, the contraction was repeated. Total duration of infusion was 1–2 min. Ten minutes after discontinuing the infusion, the contraction was repeated again (‘Recovery’).

Protocol II: mongrel dogs (n = 6)

This protocol was designed to provide evidence as to whether skeletal muscle force production is altered during K+ infusion.

The left gastrocnemius–plantaris muscle group (GP) was surgically isolated as previously described (Stainsby & Otis, 1964; Gladden & Yates, 1983). Briefly, a medial incision was made through the skin of the left hindlimb from the midthigh to the ankle. The insertion tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus muscles were cut and folded back to expose the GP. The arterial circulation to the GP was isolated by ligating all vessels from the popliteal artery that did not directly enter the GP. All vessels draining into the popliteal vein except those from the GP were ligated to isolate the venous outflow. Blood flow was measured with transit-time ultrasonic flow probes (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY, USA) placed around the left popliteal artery and vein. A cannula in a side branch of the left popliteal artery provided the site for intra-arterial administration of the K+ solution.

A portion of the calcaneus, with the two tendons of the GP attached, was cut and connected via a short coupler to an isometric load cell (Interface SM-250, Scottsdale, AZ, USA). The load cell was calibrated with known weights prior to each experiment. Following isolation, the GP was bathed in saline heated to 37°C and covered with saline-soaked gauze and a thin piece of plastic to prevent drying and cooling. Both the femur and the tibia were fixed to the base of the force platform using bone screws and connecting rods. The sciatic nerve was exposed and isolated near the GP. The distal stump of the nerve, 1.5–3.0 cm in length, was wrapped with two wire loops for stimulation. Single isometric tetanic contractions were evoked by stimulation with trains of stimuli (2 ms duration, 30 Hz frequency) at 10 × motor threshold for 1 s.

Before each experiment, the GP was set to optimal length (Lo) by progressively lengthening as the muscle was stimulated until a peak in developed tension (total minus resting tension) was observed. Once surgical isolation of the GP was complete, all equipment was in place, and Lo was determined, the muscle was allowed to rest for a minimum of 10 min while blood gases and pH were measured (Radiometer ABL520, Copenhagen). If necessary, metabolic acidosis was corrected with intravenous infusion of sodium bicarbonate. When all blood values were within normal limits, the experiment commenced.

Following a contraction under baseline conditions (Control), a potassium chloride solution containing 100 mg ml−1 K+ was infused into the popliteal artery at a constant rate to produce an estimated [K+]o of ∼40 mm. When blood flow stabilized to the infusion, the contraction was repeated. Total duration of infusion was 1–2 min. Ten minutes after discontinuing the K+ infusion, the contraction was repeated again (Recovery). Phenylephrine 10 μg ml−1 was infused as a control to determine the effect of reduced blood flow on force production.

Measurements

Arterial blood pressure, arterial and venous blood flow, and muscle force production were displayed continuously and stored using a MacLab data acquisition system sampling at 100 Hz (ADInstruments, Castle Hill, Australia). Data were analysed off-line using MacLab software for the calculation of the haemodynamic and muscle force data. Baseline measurements were averaged over the 5 s immediately preceding muscle contraction. For arterial blood flow, the peak response was determined as the highest blood flow observed after contraction. For venous blood flow, the peak response was determined as the highest blood flow observed during contraction. Since the arterial blood flow response to contraction during K+ infusion was often indistinguishable from baseline, the peak blood flow was taken at the same time blood flow peaked during the control. The change in blood flow following contraction was determined as the peak blood flow after contraction minus the baseline blood flow. Muscle force was determined as the peak muscle force minus the resting Lo force.

Statistical analysis

To examine the response to muscle contraction for Protocol I, blood pressure and hindlimb blood flow were analysed using a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (Condition × Treatment). To examine the response to muscle contraction in Protocol II, blood pressure, blood flow and muscle force production were analysed using one-way repeated measures analyses of variance. Tukey's post hoc contrasts were used when necessary to determine where significant differences occurred. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Protocol 1

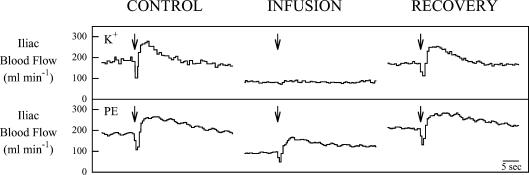

Figure 1 contains original tracings of the hindlimb blood flow response obtained in one dog following a single contraction during K+ infusion and in the same dog following a single contraction during phenylephrine infusion. Control contractions resulted in a rapid increase in hindlimb blood flow and were of a magnitude typical of those observed for this preparation in our laboratory. As expected, the infusion of K+ resulted in a reduction in baseline blood flow of about 50%. During K+ infusion the hyperaemic response to a single tetanic contraction was less than 10% of the control. In contrast, despite a similar reduction in baseline blood flow with phenylephrine infusion the hyperaemic response to contraction was preserved. Recovery contractions performed after the discontinuation of the infusions resulted in blood flow responses similar to control. Summary data for six dogs showed the same pattern (Fig. 2). Baseline haemodynamic values for Protocol I are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Original tracings showing the mean Iliac blood flow response to a 1 s contraction of the hindlimb of one dog during the K+ and phenylephrine (PE) infusion conditions of Protocol I. Arrows indicate the start of contraction. Note the rapid and marked increase in blood flow for all the contractions except for K+ infusion.

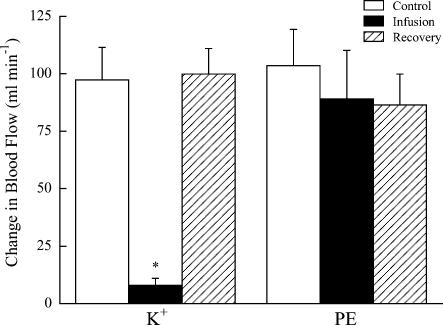

Figure 2.

Summary of the change in blood flow following hindlimb contraction in 6 dogs during the K+ and phenylephrine (PE) infusion conditions of Protocol I. Values are means ± s.e.m.*Significantly different from all other contractions (P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline haemodynamic values for the 6 dogs in Protocol I

| Potassium | Phenylephrine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Infusion | Recovery | Control | Infusion | Recovery | |

| ABP (mmHg) | 159 ± 9 | 177 ± 8 | 163 ± 8 | 164 ± 7 | 166 ± 8 | 170 ± 8 |

| BF (ml min−1) | 132 ± 27 | 60 ± 13* | 129 ± 27 | 124 ± 25 | 66 ± 12* | 128 ± 36 |

ABP, arterial blood pressure; BF, blood flow. Values are means ± s.e.m.

Significantly different from Control and Recovery (P < 0.01).

Protocol II

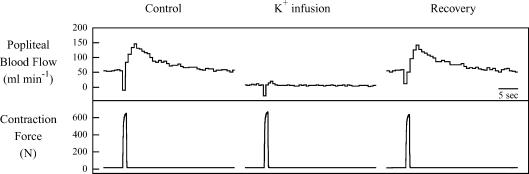

Raw tracings from an individual animal of the GP blood flow response to contraction under control, K+ infusion, and recovery are presented in Fig. 3. As can be seen in Fig. 3, a 1 s tetanic contraction produced a rapid increase in flow. When K+ was infused into the popliteal artery, the elevated [K+]o elicited the expected vasoconstriction and abolished the hyperaemic response to contraction. It is noteworthy that this K+ concentration did not alter force production by the skeletal muscle. Several minutes after discontinuation of the K+ infusion, contraction elicited an increase in flow similar to control.

Figure 3.

Original tracings showing the response to a 1 s tetanic contraction for mean popliteal blood flow and muscle force from the gastrocnemius–plantaris muscle group (GP) of one dog during Protocol II. Note the rapid and marked increase in blood flow response to contraction during the control and recovery conditions and virtually no blood flow response to contraction during K+ infusion. Also note that muscle force production was unchanged by K+ infusion.

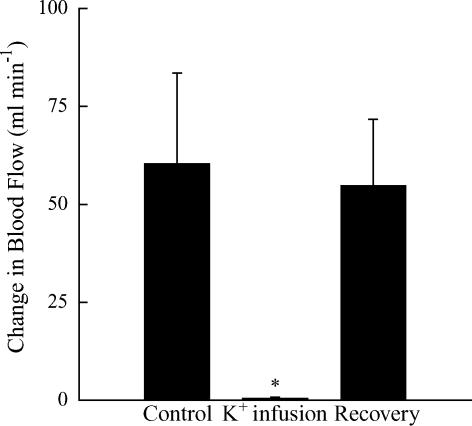

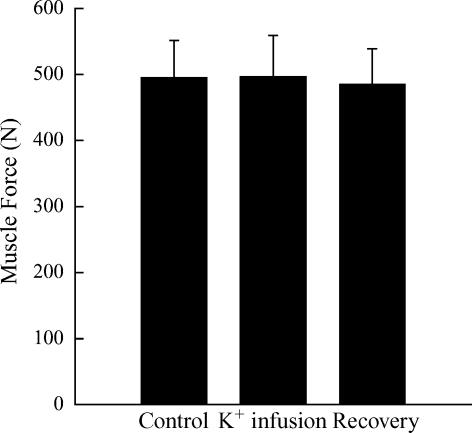

A summary of the mean blood flow response to muscle contraction is presented in Fig. 4. In response to muscle contraction, blood flow under control conditions rose 160% above the baseline. As planned, K+ infusion reduced baseline blood flow (Table 2) and abolished the contraction-induced hyperaemia (1% of control response). Muscle contraction during recovery from K+ infusion resulted in a hyperaemic response similar to control. There were no differences in the muscle force production (P > 0.05; Fig. 5) and no alterations were observed in arterial blood pressure (Table 2). Phenylephrine infusion also had no effect (P > 0.05) on muscle force production (531 ± 63 versus 532 ± 63 N, n = 5). The increase in venous outflow during contraction was the same (P > 0.05) during control (190 ± 80 ml min−1) and K+ infusion (195 ± 86 ml min−1).

Figure 4.

Summary of the change in blood flow to a 1 s tetanic contraction in 6 dogs during the three conditions of Protocol II. Values are means ± s.e.m.*Significantly different from Control and Recovery (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Baseline haemodynamic values for the 6 dogs in Protocol II

| Potassium | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Infusion | Recovery | |

| ABP (mmHg) | 162 ± 8 | 169 ± 9 | 160 ± 9 |

| BF (ml min−1) | 39 ± 16 | 5 ± 2* | 40 ± 16 |

Values are means ±s.e.m.

Significantly different from Control and Recovery (P < 0.01).

Figure 5.

Summary of the muscle force production in response to a 1 s tetanic contraction in 6 dogs during the three conditions of Protocol II. Values are means ±s.e.m. Note that there was no difference in muscle force production across conditions (P > 0.05).

Discussion

In this investigation, we examined the blood flow response to a brief tetanic contraction during which potassium (K+) was infused intra-arterially to elevate the [K+]o and clamp the smooth muscle membrane potential within the skeletal muscle vascular bed. The absence of vasodilatation virtually abolished the contraction-induced change in blood flow, indicating that vasodilatation is obligatory for a normal blood flow response to contraction. One implication of the observation that blood flow was unchanged despite preserved skeletal muscle contractile function is that the contribution of the muscle pump to the initial increase in blood flow is negligible. These results provide evidence that rapid vasodilatation is essential to increase skeletal muscle blood flow following contraction and that this rapid vasodilatation is presumably the result of smooth muscle hyperpolarization.

The notion that vasodilatation can occur rapidly and could be responsible for the increase in blood flow following muscle contraction has been a topic of investigation for more than a century and a source of continued controversy. Experiments performed in vivo support the concept that vasodilatation can occur rapidly following muscle contraction (Tschakovsky et al. 1996; Shoemaker et al. 1998; Naik et al. 1999). A common observation of in vivo investigations is that following release of muscle contraction there is an immediate and rapid increase in muscle blood flow. For example, Naik et al. (1999) observed that hindlimb blood flow was significantly elevated within 1 s following the release of a brief tetanic contraction. Following the release of contraction, the blood flow continued to rise progressively to a peak (6–7 s) with a prolonged elevation for at least 20 s. The kinetics of the blood flow response suggest a pattern of release and washout of a vasodilator substance. Although the above studies provide indirect data suggesting that vasodilatation occurs rapidly, there are direct observations of vessel diameter which also indicate rapid vasodilatation following muscle contraction (Marshall & Tandon, 1984). Marshall & Tandon showed that 1 s tetanic contractions of rat spinotrapezius muscle evoked dilatation of terminal arterioles in less than 2 s with peak dilatation occurring by 8 s, which is in general agreement with experiments performed in vivo. Furthermore, extrapolation of their dilatation response curves back to the beginning of muscle twitch contractions suggests that all arterioles of the terminal system began to dilate within 1 s of the onset of stimulation. These indirect observations (Tschakovsky et al. 1996; Shoemaker et al. 1998; Naik et al. 1999) along with direct observations (Marshall & Tandon, 1984) suggest that vasodilatation may play a role in contraction-induced hyperaemia.

On the contrary, others have argued that the time course of vasodilatation is too slow to account for the immediate and rapid increase in blood flow at the onset of exercise. Support for this view has come from investigations which have reported a rather long latency (4–20 s) to the onset of vasodilatation when measuring vessel diameter in vitro (Wunsch et al. 2000) and in situ (Gorczynski et al. 1978). One of the first studies to directly assess the role of vasodilatation following muscle contraction was performed by Gorczynski et al. They found that arteriolar diameters were not significantly increased until ∼5 s after the onset of cremaster muscle stimulation, supporting the idea that vasodilatation does not occur fast enough to be responsible for the rapid increase in blood flow following muscle contraction. However, the techniques employed in this investigation may have prolonged the latency of vasodilatation. The use of a superfusion solution provides an artificial pathway for the washout of tissue vasodilator agents which may have resulted in the delayed appearance of vasodilatation as a result of an increased time required to attain a threshold concentration of vasodilators. Jacobs & Segal (2000) have extended these findings by investigating the vasodilator response to contraction in feed arteries and arterioles in response to contractions of varying duty cycles. The latency of the onset of vasodilatation varied from approximately 5–14 s with the delay being directly proportional to vessel size. A delay in arteriolar vasodilatation has also been inferred from the time course of changes in red blood cell velocity following contractions of the spinotrapezius muscle (Kindig et al. 2002). Their results show that the velocity of red blood cells through capillaries is increased within 1–2 s of contraction despite only a modest increase in red blood cell flux. Recently, Wunsch et al. (2000) investigated the time course of the vasodilatory response of cannulated first-order arterioles to various vasodilator agents. Following introduction of vasodilator agents to the organ bath, there was a ≥4 s delay in the onset of vasodilatation. It is important to note that Wunsch et al. did not conclude that rapid vasodilatation does not occur, but rather that ‘none of the vasodilators produced a response rapid enough to contribute to the initial hyperaemia (1–2 s) at the onset of exercise.’ It is quite possible that the vasodilator agent(s) responsible for rapid vasodilatation was(were) not used in this investigation. In addition, it should be recognized that only first-order arterioles were studied and that these vessels may not be the most responsive portion of the skeletal muscle vasculature (Jacobs & Segal, 2000).

The controversy over the time course of vasodilatation following muscle contraction has been used to support an alternative mechanism to explain the initial blood flow response to contraction. It has been proposed that, if the initial increase in blood flow at the onset of exercise is not attributable to vasodilatation, it must be due to a widening of the arteriovenous pressure gradient by the skeletal muscle pump. According to this theory, muscle contraction facilitates an enhanced arterial inflow by emptying the venous circulation and increasing the pressure gradient across the muscle (Folkow et al. 1970; Laughlin, 1987; Sheriff et al. 1993). Unfortunately, a direct test of this hypothesis is not feasible because current methodologies do not permit the direct measurements of venous pressure within skeletal muscle. Because of these methodological constraints the conclusions as to the effectiveness of the skeletal muscle pump must be made from observations of blood flow. The strongest evidence for the muscle pump has come from investigations in which the blood flow response to contraction was determined following venous pressure manipulations by positioning the contracting limb above or below the heart (Folkow et al. 1971; Leyk et al. 1994; Tschakovsky et al. 1996; Shoemaker et al. 1998). The augmented blood flow response to a single contraction (Tschakovsky et al. 1996) or rhythmic contractions (Leyk et al. 1994; Shoemaker et al. 1998) with the limb positioned below the heart was attributed to the muscle pump. However, others have failed to demonstrate an influence of the muscle pump on the contraction-induced increase in blood flow (Magder, 1995; Naamani et al. 1995; Laughlin & Schrage, 1999; Dobson & Gladden, 2003). Data from our laboratory do not support the ability of the muscle pump to increase blood flow when the muscle vascular bed is unable to dilate (Hamann et al. 2003). The findings of the present study only strengthen this conclusion. When elevated [K+]o prevented presumptive contraction-induced changes in vascular smooth muscle membrane potential, vasodilatation did not occur. We considered whether depolarization of vascular smooth muscle in the veins and venules might have impaired muscle pump function by decreasing venous capacitance. This seems unlikely since venous outflow during contraction was unchanged by K+ infusion. Thus, any contribution of the muscle pump to arterial inflow should have been readily observable. The absence of a blood flow response to muscle contraction under these conditions provides strong evidence that the muscle pump does not regulate blood flow in skeletal muscle.

What is responsible for causing vasodilatation following a single muscle contraction? There are many vasodilators which have been proposed to play a role in exercise hyperaemia, but currently there are none that have been shown to be essential for exercise hyperaemia. During steady-state exercise the close matching of blood flow and metabolic demand of the tissue suggest that a metabolic vasodilator from skeletal muscle controls local vasodilatation. However, following a single muscle contraction it is unlikely that a metabolic vasodilator would respond rapidly enough. The only muscle-derived vasodilator that could conceivably account for the prompt vasodilatation is K+ which has been shown to accumulate rapidly in the interstitium (Hnik et al. 1976). It is noteworthy that the time course of appearance of K+ in venous blood is similar to the time course of the changes in blood flow at the onset of exercise (Mohrman & Sparks, 1974; Kiens et al. 1989). An alternative mechanism for the rapid vasodilatation is release of a vasoactive substance from the endothelium due to mechanical deformation during muscle contraction (Olesen et al. 1988; Lamontagne et al. 1992; Koller & Bagi, 2002).

To investigate the role of vasodilatation in the initial hyperaemic response to contraction we adapted an established model for clamping smooth muscle membrane potential in vitro (Ishizaka & Kuo, 1997; Miura & Gutterman, 1998; Nishikawa et al. 1999; Woodman et al. 2000) and employed these techniques to the in vivo and in situ exercise models used in our laboratory. Elevating [K+]o holds the membrane potential in a depolarized state (Knot & Nelson, 1998) thus impairing the dilator response to agents which act by hyperpolarizing the vascular smooth muscle. To our knowledge this is the first time this approach has been applied to an intact vascular bed. A potential limitation to this approach is that with intra-arterial K+ infusion we cannot determine the experimental effects of K+ on the vascular endothelium. The ability of the endothelium to release vasoactive substances to produce smooth muscle hyperpolarization and the resulting vasodilatation may have been compromised. However, this investigation was designed to separate the effect of vasodilatation from the initial contraction-induced hyperaemia and not to determine the source of the vasodilator agents or the specific mechanism of vasodilatation.

In summary, the hyperaemic response to contraction was abolished during intra-arterial K+ infusion, a condition in which we assume that the smooth muscle membrane potential does not change. These findings raise doubts about the influence of the muscle pump on skeletal muscle blood flow. We conclude that the rapid increase in muscle blood flow following contraction is due to vasodilatation, presumably as a result of smooth muscle hyperpolarization.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Paul Kovac and Kelly Allbee for their valuable technical assistance. We also thank Andrew Williams and Richard Rys for their continuing assistance in engineering, fabrication, and maintenance of much of our laboratory equipment. This project was supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

References

- Corcondilas A, Koroxenidis GT, Shepherd JT. Effect of a brief contraction of forearm muscles on forearm blood flow. J Appl Physiol. 1964;19:142–146. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson JL, Gladden LB. Effect of rhythmic tetanic skeletal muscle contractions on peak muscle perfusion. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:11–19. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00339.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkow B, Gaskell P, Waaler BA. Blood flow through limb muscles during heavy rhythmic exercise. Acta Physiol Scand. 1970;80:61–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1970.tb04770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkow B, Haglund U, Jodal M, Lundgren O. Blood flow in the calf muscle of man during heavy rhythmic exercise. Acta Physiol Scand. 1971;81:157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1971.tb04887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden LB, Yates JW. Lactic acid infusion in dogs: effects of varying infusate pH. J Appl Physiol. 1983;54:1254–1260. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.5.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczynski RJ, Klitzman B, Duling BR. Interrelations between contracting striated muscle and precapillary microvessels. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:H494–H504. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.235.5.H494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann JJ, Valic Z, Buckwalter JB, Clifford PS. Muscle pump does not enhance blood flow in exercising skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:6–10. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00337.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnik P, Holas M, Krekule I, Kriz N, Mejsnar J, Smiesko V, Ujec E, Vyskocil F. Work-induced potassium changes in skeletal muscle and effluent venous blood assessed by liquid ion-exchanger microelectrodes. Pflugers Arch. 1976;362:85–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00588685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaka H, Kuo L. Endothelial ATP-sensitive potassium channels mediate coronary microvascular dilation to hyperosmolarity. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H104–H112. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs TL, Segal SS. Attenuation of vasodilatation with skeletal muscle fatigue in hamster retractor. J Physiol. 2000;524:929–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00929.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiens B, Saltin B, Walloe L, Wesche J. Temporal relationship between blood flow changes and release of ions and metabolites from muscles upon single weak contractions. Acta Physiol Scand. 1989;136:551–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1989.tb08701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindig CA, Richardson TE, Poole DC. Skeletal muscle capillary hemodynamics from rest to contractions: implications for oxygen transfer. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2513–2520. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01222.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries or rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol. 1998;508:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.199br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller A, Bagi Z. On the role of mechanosensitive mechanisms eliciting reactive hyperemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2250–H2259. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00545.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne D, Pohl U, Busse R. Mechanical deformation of vessel wall and shear stress determine the basal EDRF release in the intact coronary vascular bed. Circ Res. 1992;70:123–130. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin MH. Skeletal muscle blood flow capacity: role of muscle pump in exercise hyperemia. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H993–H1004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin MH, Schrage WG. Effects of muscle contractions on skeletal muscle blood flow: when is there a muscle pump? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:1027–1035. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199907000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyk D, Essfeld D, Baum K, Stegemann J. Early leg blood flow adjustment during dynamic foot plantarflexions in upright and supine body position. Int J Sports Med. 1994;15:447–452. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind AR, Williams CA. The control of blood flow through human forearm muscles following brief isometric contractions. J Physiol. 1979;288:529–547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magder S. Venous mechanics of contracting gastrocnemius muscle and the muscle pump theory. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:1930–1935. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.6.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM, Tandon HC. Direct observations of muscle arterioles and venules following contraction of skeletal muscle fibres in the rat. J Physiol. 1984;350:447–459. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura H, Gutterman DD. Human coronary arteriolar dilation to arachidonic acid depends on cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase and Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Circ Res. 1998;83:501–507. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrman DE, Sparks HV. Role of potassium ions in the vascular response to a brief tetanus. Circ Res. 1974;35:384–390. doi: 10.1161/01.res.35.3.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naamani R, Hussain SNA, Magder S. The mechanical effects of contractions on blood flow to the muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1995;71:102–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00854966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik JS, Valic Z, Buckwalter JB, Clifford PS. Rapid vasodilation in response to a brief tetanic muscle contraction. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1741–1746. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.5.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa Y, Stepp DW, Chilian WM. In vivo location and mechanism of EDHF-mediated vasodilation in canine coronary microcirculation. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H1252–H1259. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen SP, Clapham DE, Davies PR. Haemodynamic shear stress activates a K+ current in vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1988;331:168–170. doi: 10.1038/331168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheriff DD, Rowell LB, Scher AM. Is rapid rise in vascular conductance at onset of dynamic exercise due to muscle pump? Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H1227–H1234. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.4.H1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker JK, Tschakovsky ME, Hughson RL. Vasodilation contributes to the rapid hyperemia with rhythmic contractions in humans. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;76:418–427. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-76-4-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stainsby WN, Otis AB. Blood flow, blood oxygen tension, oxygen uptake, and oxygen transport in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1964;206:858–866. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.206.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschakovsky ME, Shoemaker JK, Hughson RL. Vasodilation and muscle pump contribution to immediate exercise hyperemia. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H1697–H1701. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.4.H1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valic Z, Naik JS, Ruble SB, Buckwalter JB, Clifford PS. Elevation in resting blood flow attenuates exercise hyperemia. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:134–140. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00421.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman OL, Wongsawatkul O, Sobey CG. Contributions of nitric oxide, cyclic GMP and K+ channels to acetylcholine-induced dilatation of rat conduit and resistance arteries. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2000;27:34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2000.03199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunsch SA, Muller-Delp J, Delp MD. Time course of vasodilatory responses in skeletal muscle arterioles: role in hyperemia at onset of exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H1715–H1723. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]