Abstract

In the present study we have investigated an inhibitory pathway regulating a constitutively active Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation conductance (Icat) in rabbit ear artery smooth muscle cells. Constitutive single channel activity of Icat was recorded in cell-attached and inside-out patches with similar unitary conductance values. In inside-out patches with relatively high constitutive activity the G-protein activator GTPγS inhibited channel activity which was reversed by the protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor chelerythrine indicating a G-protein pathway inhibits channel activity via PKC. Spontaneous channel activity was also suppressed by the G-protein inhibitor GDPβS suggesting a G-protein is also involved in initiation of constitutive channel activity. Bath application of antibodies to Gαq/Gα11 enhanced channel activity whereas anti-Gα1−3/Gαo antibodies decreased basal channel activity which suggests that Gαq/Gα11 and Gαι/Gαo proteins initiate, respectively, the inhibitory and excitatory cascades. The phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U73122 increased spontaneous activity which implies a role for PLC in the inhibitory pathway. Bath application of the diacylycerol (DAG) analogue 1-oeoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) decreased the probability of channel opening (NPo) and this was reversed by chelerythrine. Application of the PKC activator phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate (PDBu) and chelerythrine, respectively, decreased and increased NPo. These data indicate that spontaneously active cation channels are inhibited by a tonic inhibitory pathway involving Gαq/Gα11-mediated stimulation of PLC to generate DAG which activates PKC to inhibit channel opening. There were some patches with relatively low NPo and it was evident that the inhibitory pathway was particularly marked in these cases. Moreover in the latter patches GTPγS and OAG caused marked increases in NPo. Together with inhibitory effects of GDPβS and anti-Gα1−3/Gαo antibodies the results suggest that there is constitutive Gαi/Gαo protein activity leading to channel opening via a DAG-mediated but PKC-independent mechanism. Finally, with whole-cell recording it is shown that noradrenaline increases Icat and the noradrenaline-evoked response is markedly potentiated by PKC inhibition. This latter observation shows that PKC also limits agonist-evoked Icat in these arterial myocytes.

Recently we have described a constitutively active non-selective cation current (Icat) in freshly dispersed rabbit ear artery smooth muscle cells (Albert et al. 2003). It was proposed that the physiological role of this channel was to contribute to the resting membrane conductance and accounts for, at least in part, a resting membrane potential, commonly −40 to −65 mV in smooth muscle, which is more depolarized than the potassium equilibrium potential. Moreover since the channel has a significant permeability to Ca2+ ions this conductance may also contribute to the basal Ca2+ influx in unstimulated cells.

There are several similarities between the tonically active Icat in ear artery myocytes and the noradrenaline-evoked non-selective cation current in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells (Albert et al. 2003). For example, Icat in ear artery displays three unitary conductance states of about 15, 25 and 40 pS (Albert et al. 2003) while in portal vein the cation channels exhibit two levels of about 13 and 23 pS (Albert & Large, 2001b). Moreover both conductances have similar Ca2+ permeabilities (PCa/PNa of about 2–3 in ear artery and 4–5 in portal vein) and are activated by the diacylglycerol (DAG) analogue 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) in a protein kinase C (PKC)-independent manner (Helliwell & Large, 1997; Albert & Large, 2001a; Albert et al. 2003). However, there are some marked differences in the properties of these two conductances. Notably, removal of external Ca2+ ions increased six-fold the probability of channel opening (NPo) of Icat in ear artery (Albert et al. 2003) but produced no significant effect on NPo in portal vein (Albert & Large, 2001b). Also in ear artery myocytes Icat is tonically suppressed by PKC activity (Albert et al. 2003) but this is not apparent with the cation channels in portal vein (Helliwell & Large, 1997). It has been shown that a member of the transient receptor potential protein family (TRPC6) is an important component of the cation channel in rabbit portal vein myocytes (Inoue et al. 2001). The above comparison of the properties suggest that Icat in ear artery is not identical to the TRPC6-like conductance in portal vein but is likely to belong to the same family/subfamily of proteins.

In the present work we have investigated the transduction mechanism regulating the inhibitory effect of PKC on Icat in rabbit ear artery myocytes using cell-attached and inside-out patches isolated from freshly dispersed cells. The data indicate that Gαq/Gα11 and phospholipase C (PLC) generate DAG to stimulate PKC-mediated inhibition of Icat. Also it is shown that noradrenaline enhances Icat and this response is also limited by PKC activity.

Methods

Cell isolation

New Zealand White rabbits (2–3 kg) were killed by an i.v. injection of sodium pentobarbitone (120 mg kg−1, in accordance with the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and ear arteries from both ears were removed into normal physiological salt solution (PSS). The tissue was dissected free of connective tissue before being cut into strips and placed in 50 μm Ca2+-PSS. The strips of tissue were enzymatically dispersed by incubation in 50 μm Ca2+-PSS with 1 mg ml−1 papain (Sigma), 1.5 mg ml−1 collagenase type IA (Sigma), 5 mg ml−1 BSA and 2.5 mmdl-dithiothreitol (DTT) for 30 min and were then washed twice in 50 μm Ca2+-PSS. All enzyme and wash procedures were carried out at 37°C. After the enzyme treatments the strips were incubated in 50 μm Ca2+-PSS at room temperature (20–25°C) for 10 min before the cells were released into the solution by gentle mechanical agitation of the strips of tissue using a wide-bore Pasteur pipette. The suspension of cells was then centrifuged (1000 r.p.m.) to form a loose pellet, which was resuspended in 0.75 mm Ca2+-PSS. The cells were then plated onto glass coverslips and stored at 4°C before use (1–6 h).

The normal PSS contained (mm): NaCl (126), KCl (6), CaCl2 (1.5), MgCl2 (1.2), glucose (10) and Hepes (11), and pH was adjusted to 7.2 with 10 m NaOH; 50 μm Ca2+-PSS and 0.75 mm Ca2+-PSS had the same composition except that 1.5 mm CaCl2 was replaced by 50 μm CaCl2 and 0.75 mm CaCl2, respectively.

Electrophysiology

Whole-cell and single channel currents were recorded with a List L/M-PC patch clamp amplifier at room temperature using whole-cell recording, cell-attached and inside-out configurations of the patch clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981). Patch pipettes were manufactured from borosilicate glass and had pipette resistances of approximately 6–10 MΩ when filled with patch pipette solution. Series resistance was not compensated. Liquid junction potentials were minimized using an agar bridge and were calculated to be < 3 mV and therefore were not compensated for in the final records. The bath chamber (vol. 0.5 ml) was perfused by two syringes in a ‘push–pull’ system.

To evaluate the current–voltage (I–V) characteristics of the whole-cell currents, voltage was stepped to −150 mV for 50 ms from a holding potential of −50 mV before a voltage ramp was applied to +100 mV (0.5 V s−1). The voltage ramps were generated and the data captured with a Pentium III personal computer (Research Machines, UK) using a digidata 1322A acquisition system and pCLAMP software (version 9.0, Axon Instruments, Inc., CA, USA) at a sample rate of 5 kHz and with filtering set at 1 kHz. At least three ramps were used to create each I–V curve. To obtain mean I–V relationships, the current values of the I–V curve from each myocyte were measured at 10 or 20 mV intervals and then ± s.e.m. values were calculated. Long-term whole-cell currents were filtered at 10 Hz and acquired at a sample rate of 25 Hz.

To evaluate the I–V curves of single channel currents the voltage was manually changed from a holding potential of −50 mV to between −90 and +50 mV. Single channel currents were initially recorded onto a DAT recorder (DRA-200, Bio-Logic Scientific Instruments) at a bandwidth of 5 kHz and a sample rate of 48 kHz. For off-line analysis channel currents were re-digitized by filtering the events at 1 kHz (−3 db, low pass 8-pole Bessel filter, Frequency Devices, model LP02, Scensys) and then acquiring these events onto a Pentium III personal computer using a digidata 1322A acquisition system and pCLAMP software at a sample rate of 10 kHz.

Mean channel current amplitudes were calculated from idealized traces produced from raw data of at least 10 s duration which had a stable baseline using the 50% threshold method. The ideal traces were able to compute events which had a duration of > 0.664 ms (two times the rise time of a 1 kHz filter) and this maximum resolution also enabled over 90% of each event amplitude to be resolved (Colquhoun, 1987).

I–V relationships of single channel currents were plotted from values obtained from peaks of channel amplitude histograms for individual patches and then unitary conductance and reversal potential (Er) were determined by linear regression (Origin software 6.1, OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). As we could not accurately determine the number of channels in a patch we measured channel activity by calculating open probability (NPo) at maximum or minimum channel activity using;

|

Constitutive channel currents were observed in about 60% of all patches tested although there was quite a large variation in activity between patches (NPo < 0.01 to over 3). Therefore we initially conducted studies on patches with activity greater than NPo > 0.01, which we have termed patches with relatively high activity and in these studies there were no significant differences between the NPo of the controls. Then we carried out further experiments on patches, which had much lower activity (NPo < 0.01).

Solutions and drugs

In whole-cell recording experiments the cells were bathed in a standard K+-free external solution containing (mm): NaCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10), glucose (11), DIDS (0.1), niflumic acid (0.1) and nicardipine (0.005), pH to 7.2 with NaOH (267 ± 5 mosmol l−1). The standard whole-cell pipette solution contained (mm): CsCl (18), caesium aspartate (108), MgCl2 (1.2), Hepes (10), glucose (11), BAPTA (1), CaCl2 (0.1, free internal calcium concentration approximately 14 nm as calculated using EQCAL software), Na2ATP (1), NaGTP (0.2), pH 7.2 with Tris (300 ± 5 mosmol 1−1). In cell-attached patch experiments the membrane potential was set at 0 mV by perfusing cells with a KCl external solution containing (mm): KCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10) and glucose (11), pH to 7.2 with 10 m KOH. Nicardipine (5 μm) was included to prevent smooth muscle cells contraction by blocking Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. The cell-attached patch pipette solution was K+-free and contained (mm): NaCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10), glucose (11), TEA (10), 4-AP (5), DIDS (0.1), niflumic acid (0.1) and nicardipine (0.005), pH adjusted to 7.2 with 10 m NaOH. The inside-out patches were perfused with a bathing solution (i.e. intracellular solution) containing (mm): CsCl (18), caesium aspartate (108), MgCl2 (1.2), Hepes (10), glucose (11), BAPTA (1), CaCl2 (0.1, free internal calcium concentration approximately 14 nm as calculated using EQCAL software), Na2ATP (1), NaGTP (0.2), pH 7.2 with Tris and the standard inside-out patch pipette solution (i.e. extracellular solution) contained (mm): NaCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10), glucose (11), pH to 7.2 with NaOH.

Anti-Gαq/Gα11, anti-Gαι1/Gαι2 and anti-Gαι3/Gαo antibodies were purchased from Calbiochem (UK) and all other drugs were from Sigma (UK). The affinity-purified antibodies were diluted in bathing solution just prior to use. In control experiments antibodies were inactivated by heating to 80–90°C for 10 min. Noradrenaline, GTPγS and GDPβS were dissolved in distilled H2O. GTPγS and GDPβS were used as lithium salts and application of 0.5 mm LiCl2 had no effect on channel activity. Solutions containing noradrenaline included 1 μm propranolol. OAG, PDBu, chelerythrine, U73122 and U73343 were dissolved in DMSO so that the final concentration of DMSO in the bathing solution was < 0.2%. Control experiments showed that 1% DMSO had no effect on constitutive channel activity. The anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody was raised against a decapeptide (QLNLKEYNLV) sequence specifically found in the C-terminal region of rabbit Gαq and Gα11 subunits. The anti-Gαι1/Gαι2 and anti-Gαι3/Gαo antibodies were also raised against selective C-terminal regions (KNNLKDCGLF and KNNLKECGLY, respectively) of these subunits from the rabbit. The values are the mean of n cells ± s.e.m. and statistical analysis was carried out using Student's t test (paired and unpaired) and one-way ANOVA with the level of significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

Properties of single channel currents recorded in cell-attached and inside-out configurations from rabbit ear artery myocytes

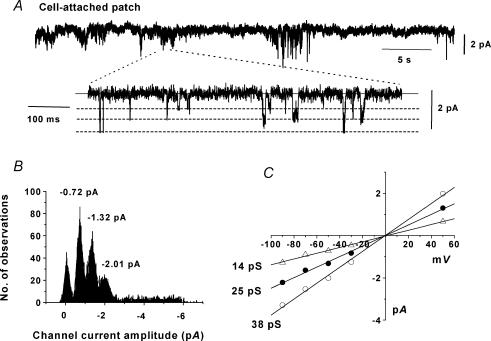

Previously we have described spontaneous cation channel activity in rabbit ear artery myocytes with whole-cell recording and outside-out patches in which the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane is subjected to experimental solutions. Therefore we initially investigated whether constitutively active cation channel currents could be recorded in cell-attached patches where the intracellular milieu is not disturbed. Figure 1A shows a typical cell-attached patch recorded at −50 mV containing constitutive cation channel activity which was present immediately upon obtaining a giga-ohm seal and which was maintained for the duration of the recording (up to 1 h) and in 32 patches this activity had a mean open probability (NPo) of 0.337 ± 0.086. The faster time scale in Fig. 1A illustrates that the channel currents reached three discrete open levels which were represented by three major peaks in the amplitude histogram shown in Fig. 1B which could be fitted by three Gaussian curves. In 32 patches the mean values were −0.66 ± 0.04, −1.29 ± 0.07 and −2.08 ± 0.05 pA at −50 mV. Figure 1C shows that these three current levels corresponded to conductance values of 14, 25 and 38 pS which all had reversal potentials (Er) of about 0 mV. In six cell-attached patches the three conductance levels had mean values of 14 ± 3.2, 23 ± 2.8 and 36 ± 3.1 pS and previously it has been discussed that these are subconductance states of the same channel (Albert et al. 2003). These experiments indicate that constitutively active cation channel currents can be recorded in cell-attached patches from ear artery myocytes.

Figure 1. Constitutively active cation channel currents in cell-attached patches from rabbit ear artery myocytes.

A, a typical cell-attached patch recording showing constitutively active cation channel currents at a holding potential of −50 mV. Openings are represented as downward deflections. On the lower faster time scale channel currents are shown allowing transitions to three different levels to be observed. The continuous line represents the closed state and the dashed lines the three different open levels. B, amplitude histogram from the patch shown in A which could be fitted with Gaussian curves representing three open channel current levels of −0.72, −1.32 and −2.01 pA and the closed state at 0 pA. Note that in all following figures the holding potential was −50 mV. C, current–voltage relationship of the three channel current levels recorded from the patch shown in A showing that the three levels correspond to conductances of 14, 25 and 38 pS.

We have previously provided evidence that protein kinase C (PKC) has a tonic inhibitory influence on constitutive channel activity in ear artery myocytes (Albert et al. 2003). The aim of the present study was to elucidate the upstream transduction mechanisms which drive the PKC-mediated inhibition of Icat. Since the study necessitated the application of cell-impermeable agents to the cytoplasmic surface of the membrane we investigated whether constitutive activity could also be recorded in inside-out patches. Figure 2A shows a typical inside-out patch whereby channel activity could be observed immediately after excision, and in 45 patches this channel activity had a mean NPo of 0.471 ± 0.105 which was not significantly different from activity recorded in cell-attached patches. The single channel currents recorded in inside-out patches also had three discrete open levels with mean values of −0.71 ± 0.12, −1.36 ± 0.15 and −2.04 ± 0.18 pA at −50 mV which corresponded to three conductances states which in six patches had mean values of 13 ± 3.4, 24 ± 2.5 and 37 ± 4.6 pS and Er of about 0 mV.

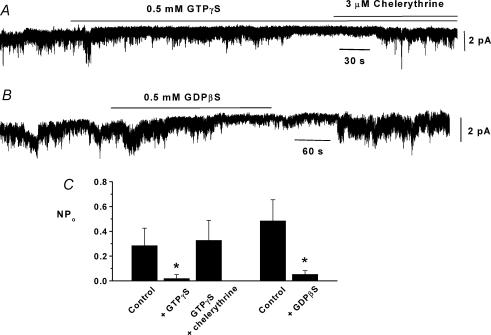

Figure 2. The role of G-proteins on constitutive cation channel activity in inside-out patches.

A, inhibition of constitutively active channel currents by bath application of 0.5 mm GTPγS which is reversed by 3 μm chelerythrine. B, reversible inhibition of constitutive activity by bath application of 0.5 mm GDPβS. C, mean data showing significant reduction of constitutive activity by GTPγS (n = 6) and GDPβS (n = 6) in inside-out patches (*P < 0.05).

Effect of G-proteins on constitutively active cation channel currents

It is well established that the phosphoinositol transduction pathway is linked to activation of PKC. Stimulation of phospholipase C (PLC) by G-proteins (probably the Gαq/Gα11 subunit) causes hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into its two immediate products, diacylglycerol (DAG) and Ins(1,4,5)P3, with DAG binding to and then activating PKC. Therefore we investigated the role of this pathway by initially studying the effect of G-proteins on constitutive channel activity.

Figure 2A and C shows that bath application of 0.5 mm GTPγS, a non-hydrolysable G-protein activator, to inside-out patches significantly reduced constitutive channel activity by about 80%. In addition Fig. 2A and C shows that the GTPγS-induced inhibition of channel activity could be reversed by bath application of the PKC inhibitor 3 μm chelerythrine. Figure 2B and C shows that bath application of 0.5 mm GDPβS, an inhibitor of G-protein activity, to inside-out patches also significantly inhibited channel activity by about 85%. These data suggest that G-protein-linked stimulation of PKC is involved in inhibiting constitutive activity and in addition a G-protein pathway is also required to initiate channel activity. Moreover these pathways are present in inside-out patches providing further evidence that processes involved in regulating constitutive activity are membrane-delimited.

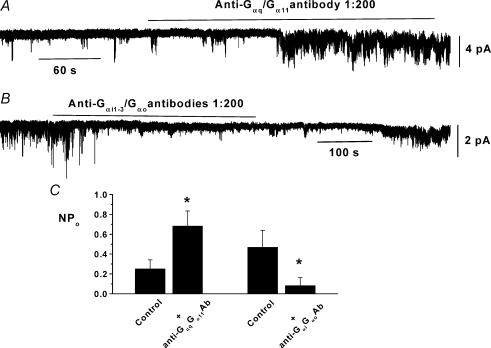

To investigate the identity of G-proteins involved in regulating constitutive activity we studied the effect of anti-G-protein α subunit antibodies, which bind to selective sequences within specific G-protein α subunits to prevent function, on spontaneous channel activity in inside-out patches. Figure 3A and C illustrates that bath application of an anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody at 1: 200 dilution significantly increased channel activity by about 2-fold whereas Fig. 3B and C shows that a combination of anti-Gαι1−3/Gαo antibodies at 1: 200 dilutions significantly reduced channel activity by about 90%. In control experiments bath application of boiled anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody (1: 200, n = 4) or anti-Gαi1−3/Gαo antibodies (1: 200, n = 5, see Methods) to inside-out patches for 5 min had no effect on channel activity whereas subsequent application of non-boiled antibodies had similar effects to those described above. These data suggest that constitutive Gαq/Gα11 subunits are involved in inhibiting spontaneous channel activity, and constitutive Gαι/Gαo subunits are implicated in the cascade leading to channel opening.

Figure 3. The effect of anti-G-protein antibodies on cation channel activity in inside-out patches.

A, bath application of an anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody at 1 : 200 dilution increased channel activity. B, bath application of a combination of anti-Gαι1/Gαι3 and anti-Gαι3q/Gαo antibodies at a dilution of 1 : 200 reversibly inhibited constitutive channel activity. C, mean data of effect of anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody (n = 10) and anti-Gαι1−3q/Gαo antibodies (n = 10, *P < 0.05).

Effect of the PLC inhibitor U73122 on constitutive cation channel activity

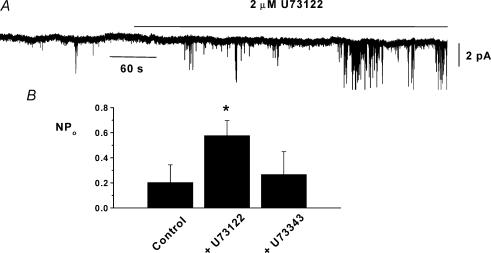

To investigate the inhibitory pathway which links G-proteins (probably Gαq/Gα11) to activation of PKC we studied the effect of the PLC inhibitor U73122 and its inactive analogue U73343 on channel activity in cell-attached patches. Figure 4 shows that bath application of 2 μm U73122 significantly enhanced channel activity by approximately 3-fold but bath application of 2 μm U73343 had no effect (n = 5, Fig. 4B). These data indicate that tonic PLC activity is also involved in inhibiting constitutive channel activity in ear artery myocytes.

Figure 4. U73122-sensitive PLC is involved in inhibiting constitutively active cation channel activity in cell-attached patches.

A, bath application of 2 μm U73122 increased cation channel activity. B, mean data of the effect of U73122 (n = 6) and U73343 (n = 5) on constitutive activity (*P < 0.05).

Effect of the DAG analogue, OAG, and the phorbol ester, PDBu, on constitutively active cation channel currents

The previous experiments suggest that a tonic G-protein-coupled pathway linked to activation of PKC is involved in inhibiting constitutive channel activity and that this pathway may utilize Gαq/Gα11 and PLC. Therefore the following experiment investigated whether the immediate product of PLC-mediated hydrolysis of PIP2, DAG, is also involved in this inhibitory pathway. Figure 5A and C shows that bath application of 40 μm OAG significantly reduced channel activity in cell-attached patches by over 95% and that this reduction could be reversed by application of 3 μm chelerythrine.

Figure 5. The effect of OAG and PKC on cation channel activity.

A, bath application of 40 μm OAG reduced constitutive channel activity in a cell-attached patch which was reversed by 3 μm chelerythrine. B, bath application of 1 μm PDBu reversibly inhibited constitutively active channel activity in an inside-out patch. C, mean data of the effects of OAG (n = 6), PDBu (n = 5) and chelerythrine (n = 6) on constitutive activity (*P < 0.05).

To confirm earlier data showing that PKC activity has a pronounced inhibitory effect on constitutive activity recorded using whole-cell and outside-out configurations of the patch clamp technique (Albert et al. 2003) we investigated whether this marked suppression of channel activity by PKC could be observed in inside-out patches. Figure 5B and C shows that bath application of 1 μm PDBu, a PKC activator, significantly reduced constitutive channel activity by over 90% in inside-out patches. Moreover we also showed that bath application of 3 μm chelerythrine significantly enhanced channel activity by about 4-fold in cell-attached patches (Fig. 5C).

These results suggest that DAG is involved in inhibiting constitutive channel activity via a PKC-dependent pathway and that tonic PKC activity has a pronounced inhibitory effect on constitutive cation channel activity in cell-attached patches as previously demonstrated with isolated patches (Albert et al. 2003).

Investigation of G-protein, PLC and PKC activity on inside-out patches containing low constitutive channel activity

The above data suggest that a pathway involving constitutive Gαq/Gα11 linked to stimulation of PLC and activation of PKC via production of DAG has a marked inhibitory effect on channel currents in patches with a relatively high constitutive activity in ear artery myocytes. As stated in Methods, there were patches which had relatively low constitutive activity which might result from low activity of the ‘driver’ mechanism or from a marked influence of the inhibitory pathway. Therefore we carried out experiments to distinguish between these possibilities.

Figure 6A shows that bath application of 0.5 mm GTPγS to an inside-out patch containing low spontaneous activity evoked significant channel activity by increasing NPo by over 100-fold (Table 1) which is in direct contrast to the effect of GTPγS in patches with relatively high activity where the agent significantly reduced NPo (see Fig. 2A and C). The GTPγS-evoked channel currents had three distinct amplitude levels with mean values of −0.70 ± 0.04, −1.35 ± 0.03 and −2.03 ± 0.06 pA (n = 8, Fig. 6A) at −50 mV which were not significantly different from the mean amplitudes of constitutively active channel currents (see above).

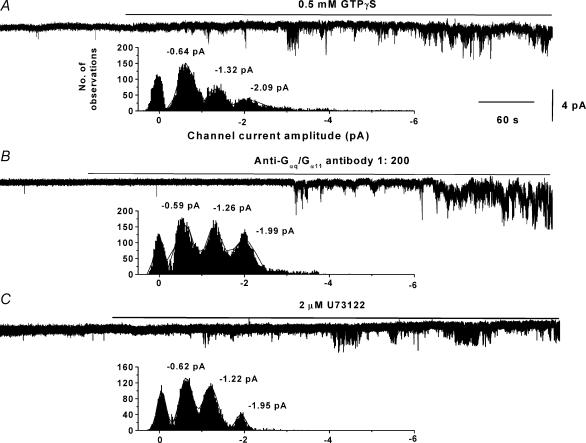

Figure 6. Effect of G-protein and PLC activity on inside-out patches containing low channel activity.

A, B and C show that bath application of, respectively, 0.5 mm GTPγS, anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody at 1 : 200 dilution and 2 μm U73122 to three separate patches evoked marked channel activity which had similar amplitude histograms indicating three open channel levels.

Table 1.

Effect of GTPγS, anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody, U73122, chelerythrine and RO-31-8220 on inside-out patches containing low constitutively active cation channel currents (NPo < 0.01)

| Agent | Control | Mean evoked NPo | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mm GTPγS | 0.008 ± 0.007 | 1.191 ± 0.274*** | 8 |

| Anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.383 ± 0.151*** | 8 |

| 2 μm U73122 | 0.004 ± 0.003 | 0.603 ± 0.132*** | 7 |

| 3 μm chelerythrine | 0.005 ± 0.004 | 2.055 ± 0.334*** | 6 |

| 3 μm RO-31-8220 | 0.004 ± 0.003 | 0.992 ± 0.442*** | 5 |

P < 0.001.

The excitatory and inhibitory effects of GTPγS confirm the previous assertion that G-proteins can initiate pathways leading to both excitation and inhibition of channel activity. Figure 6B shows that bath application of the anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody to another inside-out patch containing low activity also evoked significant channel activity by increasing NPo by over 25-fold (Table 1), which was an order of magnitude greater than Gαq/Gα11 antibody-induced increase in activity from patches with relatively high spontaneity (2-fold, see Fig. 3A and C) although the mean maximum NPo values reached were similar in both conditions (Table 1, Fig. 2C). The anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody-induced channel currents also had three amplitude levels with mean values of −0.65 ± 0.03, −1.25 ± 0.06 and −1.97 ± 0.12 pA (n = 5) at −50 mV which again were not significantly different from the values for constitutively active channel currents. In this series of experiments bath application of 0.5 mm GDPβS, anti-Gαι1−3/Gαo antibodies or boiled anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody to inside-out patches containing low activity did not evoke any channel activity.

Figure 6C shows that bath application of 2 μm U73122 to an inside-out patch significantly evoked channel activity by increasing NPo by about 50-fold (Table 1) which is much greater than increases in activity observed by U73122 on patches with relatively high activity (3-fold, see Fig. 4) although again the mean maximum NPo values were similar in both cases (Table 1, Fig. 4B). Furthermore U73122-evoked channel currents had three mean amplitude levels of −0.64 ± 0.05, −1.24 ± 0.02 and −1.99 ± 0.12 pA (n = 6, Fig. 6C) at −50 mV which were not significantly different than the amplitude levels of constitutive channel currents. Bath application of the inactive analogue U73343 had no effect on patches containing low levels of constitutive activity (n = 4, Fig. 6C). Table 1 also shows mean data from inside-out patches containing low channel activity where bath application of chelerythrine (3 μm) enhanced channel activity about 200-fold to a similar level recorded with patches containing relatively high activity (Fig. 5C). In addition 3 μm RO-31-8220, another PKC inhibitor, also markedly increased NPo (Table 1).

The effects of anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody, U73122 and PKC inhibitors were more pronounced in these patches of relatively low activity than observed in patches where NPo was relatively higher. Therefore an explanation of relatively low channel activity is that the inhibitory pathway is particularly pronounced in these patches for some unknown reason. However, we do not rule out that there may also be a reduced ‘driver’ pathway in some of these patches.

Effect of noradrenaline on Icat and role of PKC

It was of interest to investigate whether the physiological neurotransmitter noradrenaline modified constitutively active Icat in ear artery myocytes. For these experiments we investigated the responses of noradrenaline on whole-cell currents. Previously we have characterized in detail the properties of constitutive Icat using the whole-cell recording configuration (Albert et al. 2003) and in this study the properties of noradrenaline-evoked responses were compared with constitutive Icat.

Figure 7A shows that bath application of 100 μm noradrenaline evoked a rapidly activating Icat at −50 mV which declined towards the baseline level after about 2 min in the continued presence of the agonist. Figure 7D shows that the mean peak amplitude of the noradrenaline-activated Icat in 1.5 mm Ca2+ was −18 ± 2 pA (n = 7) and that the peak amplitude of noradrenaline-evoked Icat was increased about 3-fold in Ca2+-free solution (0 Ca2+o). Figure 7C shows that the mean current–voltage relationship of noradrenaline-evoked Icat was relatively linear and had an Er of about 0 mV. Moreover Fig. 7D shows that noradrenaline activated Icat when Ca2+ was the main charge carrier (89 mm Ca2+o). With 89 mm Ca2+o the I–V relationship of noradrenaline-evoked Icat exhibited inward and outward rectification at negative and positive potentials, respectively. Moreover in 89 mm Ca2+oEr was shifted positively to about +10 mV (data not shown) showing that noradrenaline-evoked Icat is permeable to Ca2+ ions.

Figure 7. Effect of noradrenaline on whole-cell Icat in ear artery myocytes.

A, bath application of 100 μm noradrenaline evoked a whole-cell Icat at −50 mV which declined in the continued presence of the agonist. B, bath application of 100 μm noradrenaline to a myocyte pre-incubated for 5 min with 3 μm chelerythrine activated a whole-cell Icat that had a much larger peak amplitude and was sustained in the continued presence of the agonist. In A and B the dashed lines represent zero holding current, and the current responses to voltage ramps have been truncated for the purpose of presentation. C, mean current–voltage relationships of noradrenaline (NA)-evoked whole-cell Icat in the absence and presence of chelerythrine. D, mean data showing peak amplitudes of noradrenaline-evoked Icat in control conditions (n = 7, 1.5 mm Ca2+o), in the presence of chelerythrine (n = 6) and in 0 Ca2+o (n = 6) and 89 mm Ca2+o (n = 5, P < 0.05).

The increase in amplitude of noradrenaline-evoked Icat in 0 Ca2+o, the change in shape of the I–V relationship and positive shift of Er of the whole-cell currents recorded in 89 mm Ca2+o are similar to properties of constitutively active whole-cell Icat previously described (see Albert et al. 2003). Therefore noradrenaline increases the constitutively active conductance.

We were interested to investigate whether PKC also inhibits the noradrenaline-evoked Icat. Figure 7B shows that bath application of 100 μm noradrenaline to an ear artery myocyte pre-incubated for 5 min with 3 μm chelerythrine evoked a rapidly activating Icat which had about a 4-fold larger peak amplitude (Fig. 7D) than the noradrenaline-evoked Icat recorded in the absence of chelerythrine. Moreover the noradrenaline-evoked Icat in the presence of chelerythrine was sustained during application of the agonist. Figure 7C shows that the I–V relationship of the noradrenaline-activated Icat in the presence of chelerythrine had a similar shape and Er to Icat recorded in the absence of chelerythrine. Preliminary data using outside-out and cell-attached patches show that noradrenaline enhances the activity of the constitutively active channel currents described in the present and previous studies (data not shown, Albert et al. 2003) indicating that noradrenaline is opening the same cation channel. Moreover, the maximum NPo of channels evoked by noradrenaline was 0.047 ± 0.013 (n = 6) in control conditions and was increased to 0.524 ± 0.072 (n = 5, P < 0.05) in the presence of 3 μm chelerythrine.

These data suggest that the physiological agonist noradrenaline can enhance constitutively active Icat in ear artery myocytes and that this response is limited by a marked inhibitory mechanism involving PKC activity.

Discussion

In the present study we have elucidated a tonic inhibitory pathway modulating the activity of a Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation current (Icat) in rabbit ear artery myocytes. Further support for the constitutive nature of this conductance was obtained using the cell-attached configuration which showed that spontaneous channel current activity was observed when the intracellular milieu was not disrupted and in the absence of an extracellular ligand. This provides further evidence that this conductance contributes to the resting membrane potential in this arterial preparation. Furthermore in this study we show that the neurotransmitter noradrenaline enhances the activity of constitutive Icat. Activation of Icat by noradrenaline will produce membrane depolarization and influx of Ca2+ ions and therefore Icat is also likely to be involved in the vasoconstrictor response to sympathetic nerve stimulation.

Inhibitory pathway regulating cation channel activity

In previous work we demonstrated with whole-cell recording and outside-out patches that tonic PKC activity suppresses Icat and in the present experiments we have focused on the upstream mechanisms which stimulate PKC. It was shown that GTPγS and OAG suppressed Icat when the constitutive activity was relatively high and these effects were reversed by the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine. These data suggest that a G-protein mechanism coupled to DAG production stimulates PKC-mediated inhibition of Icat. Moreover since the PLC inhibitor U73122 always increased Icat it is likely that this enzyme is involved in the pathway to produce DAG. Also the anti-Gαq/Gα11antibody enhanced basal Icat activity which suggests that Gαq/Gα11 is the constitutively active G-protein that initiates the inhibitory pathway. This anti-Gαq/Gα11 antibody displays significant selectivity inasmuch that it has been shown to be ineffective against a non-selective cation current activated by muscarinic receptor stimulation in guinea-pig ileal myocytes (Yan et al. 2003) and equine tracheal smooth muscle cells (Wang et al. 1997). However, anti-Gαq/Gα11 inhibits the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in this latter cell type (Wang et al. 1997). Moreover this antibody did not activate a cation current in these preparations. Therefore the simplest scheme for the inhibitory mechanism is as follows:

Since chelerythrine markedly potentiated the amplitude of the noradrenaline-evoked responses and inhibited the run-down of Icat in the continued presence of agonist it is apparent that this inhibitory pathway also antagonizes agonist-induced responses.

In patches with relatively low basal activity the agents U73122 and chelerythrine produced marked activation and NPo values approached the maximum values of patches with relatively high constitutive activity. This indicates that the inhibitory pathway described above was particularly marked in these patches although it cannot be discounted that there might be low ‘driver’ activity for channel opening in some of these patches.

Mechanisms initiating constitutive channel activity

Although the main objective of this study was to investigate the inhibitory pathway, the experiments also reveal some clues on the mechanism underlying the initiation of the constitutive activity of Icat. The compound GDPβS, which inhibits G-protein activity, produced marked depression of basal Icat activity. Moreover in patches with low spontaneous activity GTPγS (in contrast to its effect on patches with high activity) increased Icat, which indicates that a G-protein-coupled mechanism initiates channel opening and that a G-protein is the basis for spontaneous channel activity. Since anti-Gαι/Gαo antibody also suppressed tonic Icat it seems likely that Gαι/Gαo is constitutively active in these cells, which leads to channel opening. In contrast to its inhibitory action on patches with relatively high spontaneous activity OAG increased Icat in patches where channel opening was less frequent. Above it was suggested that in these patches the inhibitory pathway was particularly active and therefore these experiments show that DAG appears to have a dual action. There is an inhibitory action of DAG to stimulate PKC, which inhibits channel opening, but also DAG initiates channel opening, presumably via a PKC-independent mechanism. A similar bimodal effect was also observed with noradrenaline which initially activated/increased Icat which subsequently declined in its continued presence. In the presence of a PKC inhibitor the peak response to noradrenaline was greatly enhanced and did not decline in the continued presence of noradrenaline. A simple interpretation is that noradrenaline evokes Icat via a PKC-independent mechanism but then the response declines due to a PKC-dependent inhibition of Icat. It is proposed that DAG mediates both initial activation and subsequent inhibition which is supported by the observation that with whole-cell recording OAG produces initial activation and subsequent inhibition of Icat (Albert et al. 2003). A similar bimodal effect of OAG was recently reported on expressed TRPC3 channels (Venkatachalam et al. 2003). The transduction pathway by which noradrenaline produces DAG to produce channel opening in ear artery myocytes is not known but presumably it does not involve U73122-sensitive PLC since U73122 potentiated or activated Icat.

In patches of relatively high activity the inhibitory actions of OAG and GTPγS are predominant, presumably because the inhibitory pathway is relatively weak. In contrast, in patches with relatively infrequent channel openings due to high activity of the inhibitory pathway (see above), the excitatory actions of OAG and GTPγS are revealed. Hence the variation of spontaneous channel activity in different patches reflects an uneven balance of the excitatory and inhibitory pathways.

In conclusion, the data indicate that there are two pathways regulating Icat activity in rabbit ear artery myocytes: an inhibitory pathway is mediated by Gαq/Gα11 as outlined above and an excitatory mechanism initiated by a G-protein, possibly Gαι/Gαo, which also generates DAG to produce channel opening. The transduction pathway linking Gαι/Gαo to generation of DAG and the mechanism by which DAG opens the ion channel need to be elucidated in future experiments.

Comparison with Icat in rabbit portal vein myocytes

The present experiments have revealed further differences between Icat in rabbit ear artery and portal vein. U73122-sensitive PLC is pivotal to activation of noradrenaline-evoked Icat in portal vein (Helliwell & Large, 1997) whereas in ear artery U73122-sensitive PLC is involved in suppressing channel activity. Also with identical recording conditions there does not appear to be a PKC-mediated inhibitory mechanism in portal vein. Neither phorbol esters nor chelerythrine altered the amplitude of noradrenaline- or OAG-induced currents in portal vein (Helliwell & Large, 1997) in contrast to the marked inhibitory influence of PKC on constitutively active and noradrenaline-evoked Icat in ear artery. In ear artery Icat has constitutive activity as revealed in whole-cell recording (Albert et al. 2003) and isolated patches but also can be increased by noradrenaline. In portal vein TRPC6-like currents have much lower constitutive activity and appear to be predominantly involved in agonist-induced responses (Large, 2002).

In conclusion, we have elucidated an inhibitory pathway regulating constitutive and noradrenaline-evoked Icat in ear artery myocytes. This inhibitory pathway utilizes Gαq/Gα11 and PLC which are usually involved in the activating mechanisms of some native G-protein-coupled non-selective cation channels and expressed TRPC channels.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust.

References

- Albert AP, Large WA. Comparison of spontaneous and noradrenaline-evoked non-selective cation channels in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2001a;530:457–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0457k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Large WA. The effect of external divalent cations on spontaneous non-selective cation channel currents in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2001b;536:409–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0409c.xd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Piper AS, Large WA. Properties of a constitutively active Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channel in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;549:143–156. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.038190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D. Practical analysis of single channel recordes. In: Standen NB, Gray PTA, Whitaker MJ, editors. Microelectrode Techniques. Cambridge: The Company of Biologists; 1987. pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell RM, Large WA. α-Adrenoceptor activation of a non-selective cation current in rabbit portal vein by 1, 2-diacyl-sn-glycerol. J Physiol. 1997;499:417–428. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Okada T, Onoue H, Harea Y, Shimizu S, Naitoh S, Ito Y, Mori Y. The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular α-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ Res. 2001;88:325–337. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA. Receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channels in vascular smooth muscle: a physiologic perspective. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:493–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K, Zheng F, Gill DL. Regulation of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channel function by diacylglycerol and protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29031–29040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y-X, Fleischmann BK, Kotlikoff MI. M2 receptor activation of non-selective cation channels in smooth muscle cells: calcium and Gi/Go requirements. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C500–508. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H-D, Okamoto H, Unno T, Tsysyura YD, Prestwich SA, Komori S, Zholos AV, Bolton TB. Effects of G-protein-specific antibodies and Gβγ subunits on the muscarinic receptor-operated cation current in guinea-pig ileal smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:605–615. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]