Abstract

The management of thyroid nodules is multi-disciplinary and involves head and neck surgeons, pathologists and radiologists. Ultrasound is easy to perform, widely available, does not involve ionizing radiation and is readily combined with fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC). It is therefore an ideal investigation of choice for evaluating thyroid nodules. It evaluates specific features that help in identifying the nature of the nodule and FNAC helps in diagnostic accuracy. In addition, following treatment for thyroid cancer ultrasound provides a safe tool for disease surveillance. This paper discusses the role of ultrasound in the management of patients with thyroid cancer.

Keywords: Thyroid gland, cancer, ultrasound

Introduction

Patients presenting with a palpable thyroid nodule is a common clinical dilemma. The incidence of solitary thyroid nodule is approximately 3.2% of the population in the UK and 4.2% in the USA [1–4]. They are four times more common in women than in men and the prevalence increases with age [1–4]. The risk of malignancy in a euthyroid patient with a solitary thyroid nodule is estimated to be 5%–10% with a range of 3.4%–29% [5–10].

Overall thyroid cancer is a relatively uncommon malignancy which constitutes about 0.5% of all malignancies. However, imaging plays an important role in patients’ management as:

(1) Most thyroid nodules are benign, usually as a part of multinodular changes. Clinical examination is poor at detecting small thyroid nodules, highlighted by the fact that approximately 70% of normal thyroid glands contain nodules of less than 1 cm when examined sonographically [11–15]. The ultimate aim in the management of a thyroid nodule is to identify the small group of patients in whom the nodule is malignant and would benefit from early aggressive treatment while avoiding unnecessary investigation and surgery in the majority of patients who have a benign nodule. Imaging, especially with the use of high resolution ultrasound, helps to differentiate a malignant nodule from a more common benign thyroid nodule and identify a malignant nodule against a background nodular goitre, the incidence of which varies between 1% and 3% [16].

(2) Treatment planning and patients’ prognosis for thyroid cancer depend largely on the tumour staging. Imaging helps early detection of local invasion, regional nodal spread and presence of distant metastases.

(3) In the past, patients with thyroid cancer were invariably treated with total thyroidectomy. In contemporary surgical practice, more and more patients are treated with partial/hemi-thyroidectomy. Ultrasound therefore helps in detecting the presence of a small malignant lesion in the contralateral lobe and can be used as follow-up imaging for disease surveillance and early detection of tumour recurrence.

This review mainly focuses on the use of ultrasound, which, in our experience, is the most useful modality in thyroid cancer imaging. The role of supplementary imaging techniques is also briefly discussed.

Imaging modalities

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is an ideal imaging modality for detection and assessment of a thyroid nodule. It is easy to perform, widely available and does not involve ionizing radiation. The use of high frequency transducers has significantly improved the spatial and contrast resolution in evaluating superficial structures including the thyroid gland. One obvious advantage of ultrasound over other imaging modality is its ability to combine with fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) to increase the diagnostic accuracy.

The use of ultrasound in thyroid cancer imaging is dealt with in more detail in the later part of the review, but in brief, its major roles include:

–detection and characterization of thyroid cancer

–detection of cervical nodal metastases

–follow-up of patients after treatment for early detection of local or nodal tumour recurrence

–provide imaging guidance for FNAC or biopsy.

Radionuclide imaging

Radionuclide thyroid imaging was the mainstay in the past for the assessment of a solitary thyroid nodule. Our experience has been similar to other recent reports that scintigraphy has a limited role in routine clinical practice as it is unable to accurately differentiate a benign from a malignant thyroid nodule [17–21]. The major role of nuclear medicine is the detection and treatment with radioactive iodine for residual malignant thyroid tissue and metastatic disease in patients with well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma after total thyroidectomy.

Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

In our experience both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have a limited role in the initial investigation of a patient presenting with a thyroid nodule. In invasive thyroid malignancy, cross-sectional imaging (CT, MRI) help to evaluate extrathyroid spread of tumour to adjacent structures such as the larynx, trachea and vessels within the carotid sheath [18, 22] and provide evidence of regional or distant metastases.

Management protocol

The vast majority of patients with thyroid malignancy are euthyroid. Although of limited value, patients usually have a baseline thyroid function test, as a hyperfunctioning nodule with suppressed TSH is associated with a low risk of malignancy [23].

The imaging investigation of a thyroid nodule varies between different centres, and is based on local expertise and availability of imaging modalities. In most centres, ultrasound with FNAC is the initial investigation of choice. The main aim of any imaging investigation is to accurately identify those patients with malignant thyroid nodules so that prompt and appropriate treatment can be offered.

FNAC is inexpensive, widely available and easy to perform, and is therefore regarded as a part of the initial investigation for a thyroid nodule. Acute complications are rare and there is no reported case of cutaneous implantation of malignant cells following FNAC of thyroid nodule [18]. It has a pre-operative predictive accuracy of more than 90% [18] and aids the surgeon in selecting the most appropriate procedure prior to surgery. It has reduced the cost of work-up compared with either ultrasound or scintigraphy [9]. However, the utility of FNAC depends on the skill of the person performing the procedure and on the experience of the cytopathologists [18]. FNAC has an overall false negative rate of between 0.5% and 11.8% (pooled rate of 2.4%) and a false positive rate of 0%–7.1% (pooled rate of 1.2%) [9, 24]. The false negative rates can be reduced by better sampling techniques, meticulous follow-up and serial FNAC examinations [18].

Ideally ultrasound guided FNAC is the diagnostic procedure of choice as it clearly directs and identifies the position of the needle during the procedure, thus increasing the diagnostic yield and safety. However, in routine clinical practice, conventional FNAC is more cost-effective than ultrasound guided FNAC as an initial investigation procedure [25]. An ultrasound guided FNAC is recommended for [26–28]:

–impalpable or poorly palpable nodules (<2 cm)

–non-diagnostic or failed previous conventional FNAC.

Use of ultrasound in thyroid cancer imaging

Equipment and technique

An advanced ultrasound machine with a high frequency transducer (7.5–12 MHz) is the basic equipment required. High frequency transducers allow superior near field resolution and form the basis of characterization of benign and malignant thyroid nodules. Colour flow applications are now standard, and a high sensitivity colour flow and power Doppler system is ideal. When using colour flow and power Doppler the machine should be calibrated to allow depiction of slow flowing vessels in the head and neck.

In evaluating the thyroid gland, scanning in the transverse and longitudinal planes is the most commonly used method. Adequate extension of the neck is required to ensure complete assessment of the inferior aspect of the thyroid gland, though this may be difficult in the elderly. Adjusting the depth and gain settings is essential to ensure the whole of both lobes and the superficial isthmus are fully assessed. To evaluate large goitres a lower frequency (5 MHz) transducer may be required to assess extension into the retroclavicular/retrosternal region.

Ultrasound examination of the thyroid must always include a detailed examination of the neck for any cervical lymphadenopathy. Metastatic cervical lymph nodes are frequently seen in thyroid cancers and may affect the surgical management and prognosis of patients.

Ultrasound features of thyroid nodules

The vast majority of thyroid nodules are benign, and the role of a radiologist in assessment of the thyroid gland is to differentiate a malignant thyroid nodule from the more commonly seen benign ones. It is therefore important to evaluate the sonographic features of thyroid nodules as these aid in their characterization.

Echogenicity

The incidence of malignancy is 4% when a solid thyroid nodule is hyperechoic. If the lesion is hypoechoic (Fig. 1), the incidence of malignancy rises to 26% [29]. However, hypoechogenicity alone is inaccurate in predicting malignancy, and if used as a sole predictive sign, it has a relatively poor specificity (49%) and positive predictive value (40%) [30].

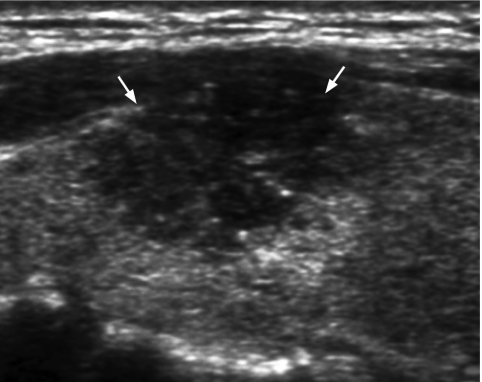

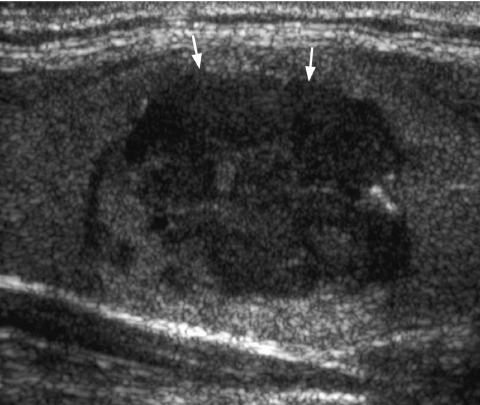

Figure 1.

Longitudinal grey scale sonogram shows a solid, hypoechoic thyroid nodule (arrows) with ill-defined margins anteriorly. Histology: papillary carcinoma.

Margins

A malignant thyroid nodule tends to have ill-defined margins on ultrasound (Fig. 1). A peripheral halo of decreased echogenicity is seen around hypoechoic and isoechoic nodules and is caused by either the capsule of the nodule or compressed thyroid tissue and vessels [31]. The absence of a halo has a specificity of 77% and sensitivity of 67% in predicting malignancy [32].

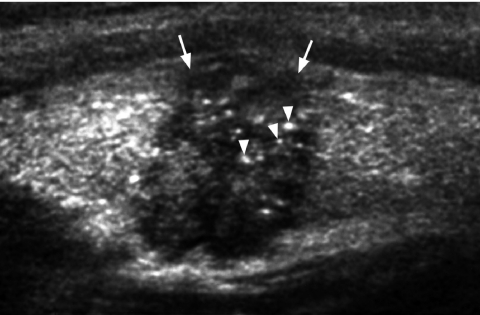

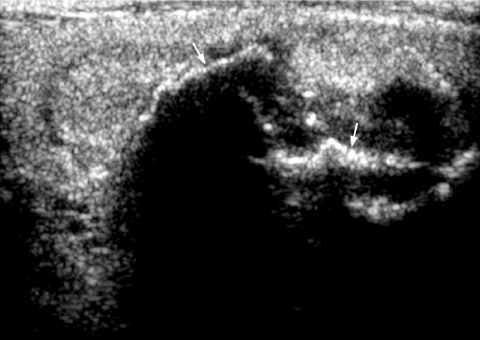

Calcification

Fine punctate calcification (Fig. 2) due to calcified psammoma bodies within the nodule is seen in papillary carcinoma in 25%–40% of cases [16]. If used as the sole predictive sign of malignancy, microcalcification is the most reliable one with an accuracy of 76%, specificity of 93% and a positive predictive value of 70% [30]. Coarse, dysmorphic or curvilinear calcifications commonly indicate benignity (Fig. 3).

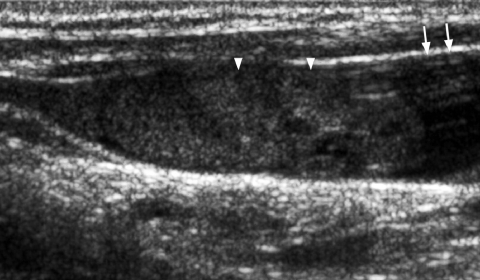

Figure 2.

Longitudinal grey scale sonogram shows characteristic punctate calcification (arrowheads) within an ill-defined solid hypoechoic thyroid nodule (arrows) which is highly suggestive of papillary carcinoma.

Figure 3.

Longitudinal grey scale sonogram shows coarse calcifications (arrows) with dense shadowing within a thyroid nodule suggestive of benign calcification.

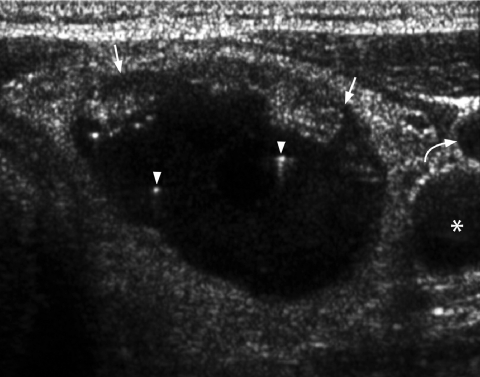

Comet tail sign

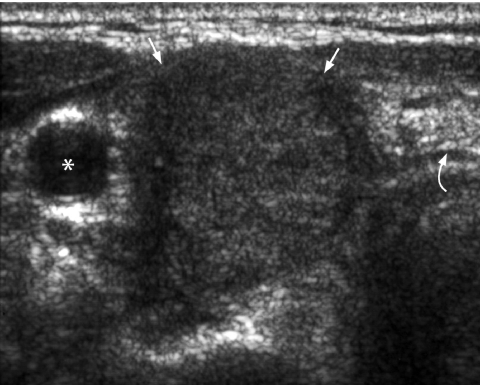

The presence of a comet tail (Fig. 4) sign in a thyroid nodule indicates the presence of colloid within a benign colloid nodule [33] and is a strong predictor of benignity.

Figure 4.

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows the presence of comet-tail artifacts (arrowheads) within a predominantly cystic thyroid nodule (arrows). Features are of a benign colloid nodule. Curved arrow identifies the internal jugular vein and asterisk marks the common carotid artery.

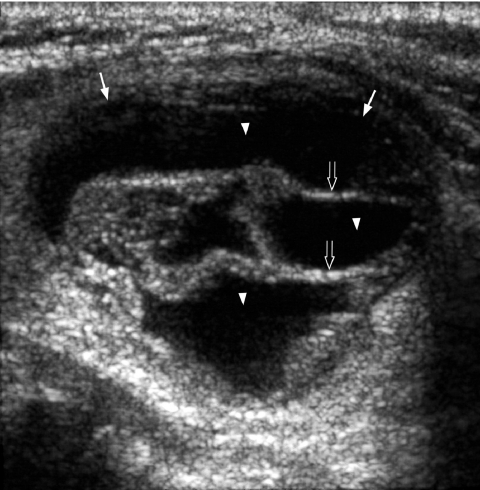

Solid/cystic

It is generally believed that thyroid nodules with large cystic components are usually benign nodules that have undergone cystic degeneration or haemorrhage (Fig. 5). However, papillary carcinoma occasionally demonstrates a cystic component and may mimic a benign nodule, though the presence of punctate calcification within the solid component helps in its identification (Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

Longitudinal grey scale sonogram shows a well-defined heterogeneous thyroid nodule (arrows) with a large cystic component (arrowheads) and septation (open arrows). Features are compatible with a benign hyperplastic nodule.

Figure 6.

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows a cystic component (open arrows) within a papillary carcinoma (arrows) of the thyroid. The presence of punctate calcification (arrowheads) identifies its malignant nature.

Multinodularity

It is a myth that multinodularity implies benignity, as approximately 10%–20% of papillary carcinomas may be multicentric [31, 34]. In those with true solitary nodules confirmed at surgery the risk of cancer is the same as in those with multinodular goitres [35]. Therefore against a background of multinodular changes, extra caution should be taken not to miss a suspicious nodule.

Colour flow patterns

In general there are three patterns of vascular distribution within a thyroid nodule [36]:

–Type I: complete absence of flow signal within the nodule

–Type II: exclusive perinodular flow signals

–Type III: intranodular flow with multiple vascular poles chaotically arranged, with or without significant perinodular vessels.

Type III pattern is generally associated with malignancy. Types I and II are more commonly seen in benign hyperplastic nodules [36, 37]. Unfortunately if used as the sole predictor of malignancy, colour flow characteristics are not accurate [32], and have to be used in combination with other features seen on grey scale ultrasound.

It is well recognized that the predictive ability of ultrasound for malignancy is effective only when multiple signs are present in the same nodule. Although their predictive value increases in summation, it is at the cost of sensitivity [32].

Common thyroid carcinomas

Papillary carcinoma

Papillary carcinoma accounts for 60%–70% of all thyroid malignancies [38], with a peak incidence in the third and fourth decades. Females are more commonly affected than males. The tumour commonly spreads along the rich lymphatic system within and adjacent to the thyroid gland accounting for the multifocal nature of the tumour within the thyroid gland and its spread to regional lymph nodes. Venous invasion occurs in 7% of papillary carcinomas and distant metastases to bone and lung are seen in 5%–7% [39].

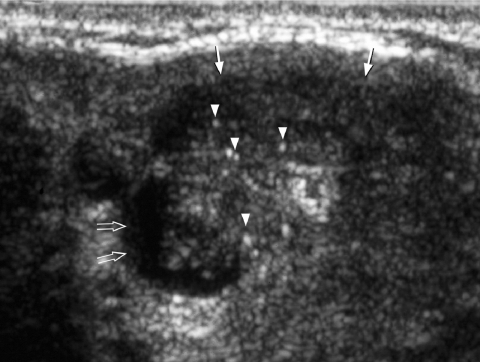

Ultrasound features of papillary carcinoma include (Figs 7–9):

–predominantly solid (70%) and hypoechoic (77%–90%) [16, 37]

–presence of punctate microcalcification (25%–90%) [16, 37], correspond to psammomas bodies on microscopy

–chaotic intranodular vascularity on colour flow imaging [37]

–adjacent characteristic lymph nodes [44]: cystic necrosis in 25%, microcalcification in 50%, located in the pre-/paratracheal regions and along the cervical chains.

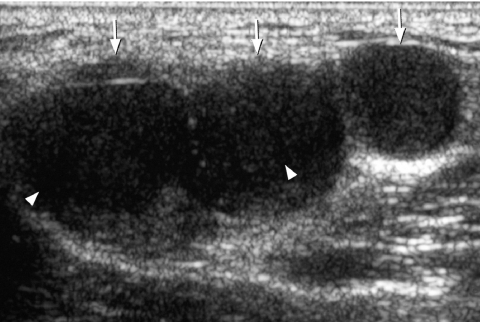

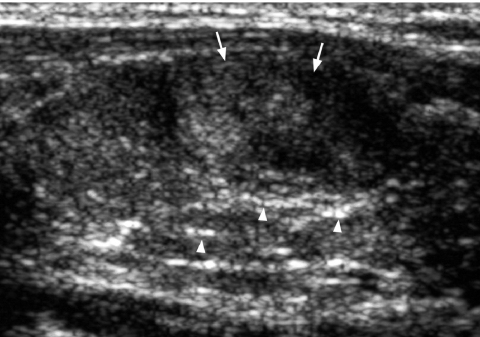

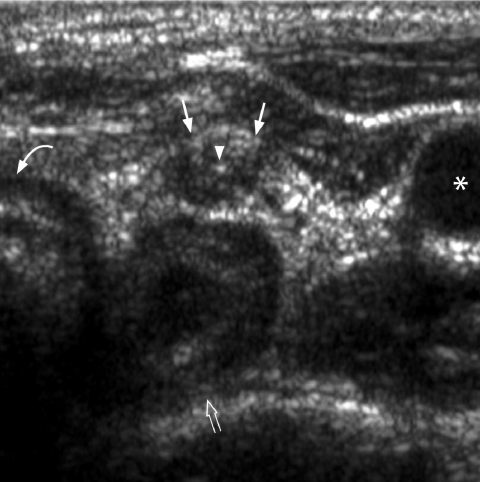

Figure 7.

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows a solid, ill-defined, hypoechoic nodule (arrows) containing punctate calcification (arrowheads) in the right lobe of thyroid gland. Features are typical of papillary carcinoma of thyroid. Asterisk identifies the common carotid artery and curved arrow the trachea.

Figure 8.

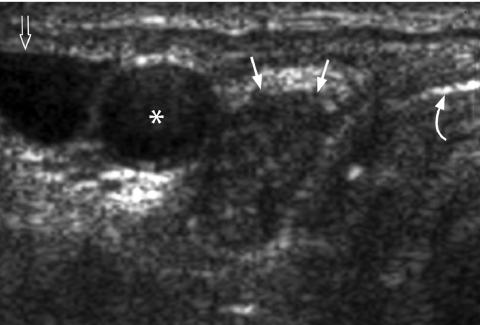

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows multiple round, solid, slightly hyperechoic cervical lymph nodes (arrows) with punctate calcification (arrowheads) in upper jugular chain. Features are suggestive of metastatic lymph nodes from primary papillary carcinoma of thyroid. Curved arrow identifies the internal jugular vein and asterisk marks the common carotid artery.

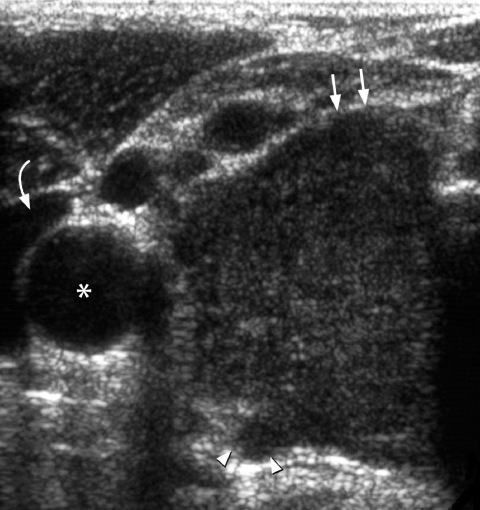

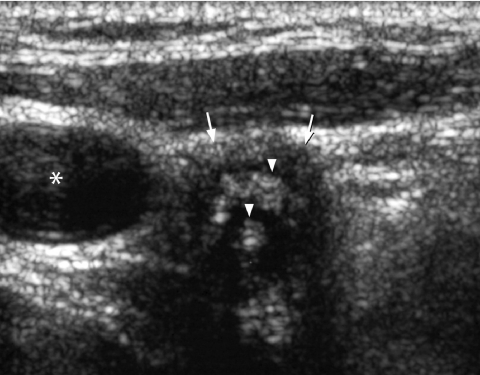

Figure 9.

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows multiple enlarged hypoechoic cervical lymph nodes (arrows) with internal cystic necrosis (arrowheads) in a patient with metastatic lymphadenopathy from papillary carcinoma of thyroid.

Anaplastic carcinoma

Anaplastic carcinoma is one of the most aggressive head and neck cancers and has a grave prognosis. It accounts for 15%–20% of all thyroid cancers [38]. The diagnosis is suspected clinically with rapid growth in a long-standing thyroid nodule. Patients frequently present with signs and symptoms of airway compression.

Ultrasound features of anaplastic carcinoma include (Fig. 10):

–hypoechoic tumour diffusely involving the entire lobe or gland

–ill-defined margin

–areas of necrosis in 78% [16]

–nodal or distant metastases in 80% of patients [45, 46]; the involved lymph nodes show evidence of necrosis in 50% [16]

–multiple small intranodular vessels on colour flow imaging

–extracapsular spread and vascular invasion in a third of patients [45, 46].

Figure 10.

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows a large, solid, hypoechoic mass (arrows) occupying the right lobe of thyroid gland. Note the presence of extra-thyroid spread posteriorly (arrowheads). Histology: anaplastic carcinoma. Curved arrow identifies the internal jugular vein and asterisk marks the common carotid artery.

Medullary carcinoma

Medullary carcinoma is believed to arise from parafollicular C-cells that secrete thyrocalcitonin. It represents 5% of all thyroid cancers [38]. In 10%–20% of all cases there is a family history of phaechromocytoma or hypercalcaemia. At presentation, 50% of cases have nodal metastases and 15%–25% have distant metastases to liver, lungs and bone [39]. Medullary carcinoma may be associated with MEN syndrome, and these patients have a biologically more aggressive tumour and may develop metastases earlier with a 55% 5-year survival rate [47, 48]. Recurrence in the neck and mediastinum is common in medullary carcinoma and is reflected biochemically with increased serum calcitonin levels.

Ultrasound features of medullary carcinoma include (Fig. 11):

–solid hypoechoic nodule

–echogenic foci in 80%–90% of tumours due to amyloid deposition and associated calcification [16, 38]; similar deposits are also seen in 50%–60% of associated nodal metastases

–chaotic intranodular vessels within the tumour on colour flow imaging.

Figure 11.

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows an ill-defined, solid, hypoechoic mass (arrows) occupying the left lobe of the thyroid gland. Multiple echogenic foci (arrowheads) casting dense posterior acoustic shadowing probably related to amyloid deposition and associated calcification. Appearance is that of a medullary carcinoma. Note how it closely resembles a papillary carcinoma. Curved arrow identifies the trachea and asterisk marks the common carotid artery.

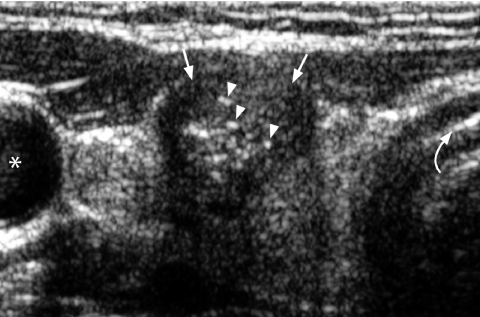

Follicular lesions

A follicular thyroid lesion comprises follicular adenoma and follicular carcinoma which can only be distinguished on histology of the surgical specimen by the presence/absence of vascular and capsular invasion. Therefore it is often not possible to differentiate a benign from a malignant follicular lesion with FNAC or core biopsy. Some clinicians therefore prefer to use the collective term ‘follicular lesion’ for both a benign follicular adenoma and a malignant follicular carcinoma.

Although it is not possible to differentiate benign from malignant follicular lesion on FNAC/core biopsy, some cytologists will try and classify these into microfollicular and macrofollicular types. The latter is associated with a low risk of carcinoma, whereas in 20%–25% a microfollicular lesion may be a follicular carcinoma [49].

A follicular carcinoma accounts for 2%–5% of all thyroid cancers [37] and is more prevalent (25%–30%) in iodine deficient areas [50]. In most cases it develops from a pre-existing adenoma and has propensity for haematogenous metastases to lungs, liver, bone and brain. Nodal metastases in the neck are less commonly encountered.

Ultrasound features of follicular lesions include:

–hyperechoic/isoechoic in echotexture (Fig. 12); hypoechoic lesions have a higher risk of being malignant (Fig. 13) [51]

–predominantly solid and homogeneous in 70% [51]

–well-defined, haloed in 80% [51]

–benign lesions have a type II vascularity, whereas malignant lesions have a type III vascularity [37].

Figure 12.

Longitudinal grey scale sonogram shows a well-defined hyperechoic nodule (arrows) in the left lobe of thyroid gland suggestive of a follicular lesion.

Figure 13.

Longitudinal grey scale sonogram shows an ill-defined heterogeneous thyroid nodule (arrows). The hypoechoic nature of the follicular lesion raises the suspicion of follicular carcinoma which was confirmed on subsequent thyroidectomy.

Ultrasound, in most cases, cannot accurately distinguish a benign from malignant follicular lesion. The suspicion of malignancy is raised if the nodule is ill-defined, hypoechoic, has a thick irregular capsule and chaotic intranodular vascularity. The only reliable signs of malignancy on ultrasound include frank vascular invasion to adjacent vessels (such as internal jugular vein and common carotid artery) (Fig. 14) and extracapsular spread.

Figure 14.

Longitudinal grey scale sonogram shows the presence of floating hypoechoic thrombus (arrowheads) within the distended internal jugular vein (arrows). Colour/power Doppler will demonstrate vascularity in a tumour thrombus which distinguishes it from a stasis venous thrombus.

Thyroid metastases

Metastases to the thyroid gland is infrequent; the incidence in patients with known primary is 2%–17% [52]. Metastases to the thyroid are due to haematogenous spread, most commonly from primary melanoma, breast carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, lung carcinoma and colonic carcinoma.

Ultrasound features of thyroid metastases include [52]:

–homogeneous, hypoechoic mass (Fig. 15)

–well-defined margins

–predominantly in the lower pole

–heterogeneous echopattern when the gland is diffusely involved

–multiple, hypoechoic solid, thyroid nodules

–chaotic intranodular vascularity.

Figure 15.

Transverse grey scale sonogram in a patient with known breast carcinoma shows a well-defined, solid, homogeneous hypoechoic mass (arrows) occupying the right lobe of thyroid. FNAC confirmed a metastatic carcinoma. The curved arrow identifies the trachea and the asterisk marks the common carotid artery.

Lymphoma

Lymphoma accounts for 1%–3% of all thyroid malignancies. An antecedent history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is commonly present [16, 38]. Thyroid involvement is more commonly seen in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma than in Hodgkin’s disease. The typical clinical presentation is an elderly female with a rapidly enlarging neck mass. Thyroid involvement may be focal or diffuse, extrathyroid spread and vascular invasion are seen in 50%–60% and 25%, respectively [53, 54].

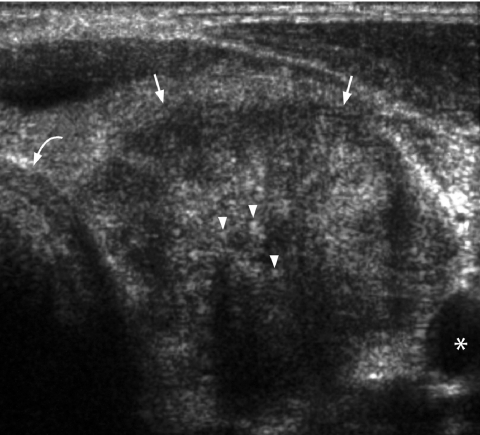

Ultrasound features of lymphoma of thyroid gland include:

–focal thyroid involvement may be seen as a well-defined nodule with pseudocystic appearance or heterogeneous appearance (Fig. 16)

–diffuse involvement may result in heterogeneous echopattern or simple enlargement of the gland with normal echopattern

–associated round, hypoechoic, reticulated lymphomatous nodes in the neck

–background of previous Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in the form of echogenic fibrous strands within the thyroid gland is often seen (Fig. 16).

Figure 16.

Longitudinal grey scale sonogram shows an ill-defined, solid, hypoechoic nodule (arrows) in the thyroid gland. Thin echogenic lines (arrowheads) in the adjacent thyroid glandular parenchyma indicate background Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Biopsy confirmed non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the thyroid gland.

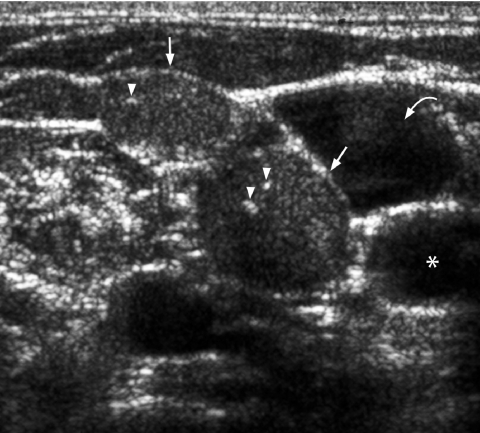

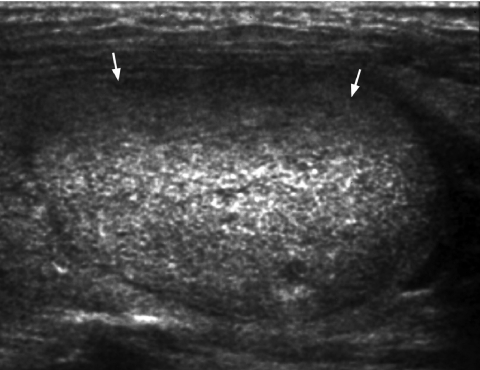

Use of ultrasound in follow-up

Evaluation of recurrent disease is often a diagnostic dilemma. Thyroglobulin levels (for well-differentiated carcinoma), total body iodine-131 scans and serum calcitonin (for medullary carcinoma) assays form an integral part of detection of tumour recurrence. In the postoperative state ultrasound may be difficult to perform. However, in experienced hands it can clearly evaluate the postoperative thyroid bed for the presence or absence of any residual disease (Fig. 17). The patient can be regularly followed up with ultrasound examination of the neck for the early detection of local and nodal tumour recurrence (Fig. 18). One has to be aware that post-operative suture granulomas may appear sonographically as hypoechoic nodules with coarse echogenic foci casting posterior acoustic shadowing in the thyroid bed (Fig. 19). The appearance may mimic that of recurrent papillary carcinoma, especially for radiologists not familiar with ultrasound of the neck. In patients where probable recurrent disease is identified, ultrasound is supplemented by a guided FNAC for a definitive diagnosis of tumour recurrence.

Figure 17.

Transverse grey scale sonogram in a patient 1 year after total thyroidectomy for papillary carcinoma shows a small hypoechoic nodule (arrows) with punctate calcification (arrowhead) in the left thyroid bed. FNAC confirmed local tumour recurrence. The curved arrow identifies the trachea, the open arrow the oesophagus and the asterisk marks the common carotid artery.

Figure 18.

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows an enlarged hypoechoic right paratracheal lymph node (arrows) 6-months after thyroidectomy for papillary carcinoma. Surgical excision confirmed regional nodal recurrence. The curved arrow identifies the trachea, the open arrow the internal jugular vein and the asterisk marks the common carotid artery.

Figure 19.

Transverse grey scale sonogram shows an ill-defined hypoechoic nodule (arrows) in the right thyroid bed containing coarse echogenic foci (arrowheads). Features are suggestive of a suture granuloma. The asterisk identifies the common carotid artery.

Conclusion

The management of a thyroid nodule is multi-disciplinary and involves head and neck surgeons, radiologists and pathologists. Radiologists must be familiar with the various signs on ultrasound that help to distinguish benign from malignant thyroid nodules and the typical appearance of common thyroid cancer. In addition, ultrasound provides a safe tool for disease surveillance in patients with thyroid cancer after treatment.

References

- 1.Tunbridge WMG, Evered DC, Hall R, et al. The spectrum of thyroid disease in a community: the Whickham survey. Clin Endocrinol. 1977;7:481–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1977.tb01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vander JB, Gaston EA, Dawber TR. The significance of nontoxic thyroid nodules: final report of a 15-year study of the incidence of thyroid malignancy. Ann Intern Med. 1968;69:537–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-69-3-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rojeski MT, Gharib H. Nodular thyroid disease: evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:428–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198508153130707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rallison ML, Dobyns BM, Meikle AW, et al. Natural history of thyroid abnormalities: prevalence incidence, and regression of thyroid diseases in adolescent and young adults. Am J Med. 1991;91:363–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90153-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lahey FH, Hare HF. Malignancy in adenomas of the thyroid. J Am Med Assoc. 1951;145:689–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.1951.02920280001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liechty RD, Graham M, Freemeyer P. Benign solitary thyroid nodule. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;121:571–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watkinson JC, Maisey MN. Imaging head and neck cancer using radioisotopes: a review. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:653–7. doi: 10.1177/014107688808101114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gharib H. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of thyroid nodules: advantages, limitations, and effect. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:44–9. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JP, Pillsbury HC III. Management of the thyroid nodule. Head Neck. 1989;11:414–25. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880110507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siperstein A, Clark O. The Thyroid. 8th edn. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co; 2000. Carcinoma of follicular epithelium: surgical therapy; pp. 898–903. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brander A, Viikinkoski P, Nickels J, Kivisaari L. Thyroid gland: US screening in a random adult population. Radiology. 1991;181:683–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.3.1947082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ezzat S, Sarti DA, Cain DR, Braunstein GD. Thyroid incidentalomas. Prevalence by palpation and ultrasonography. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1838–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.154.16.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins CR, Reading CC. Thyroid and parathyroid imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1995;16:279–95. doi: 10.1016/0887-2171(95)90033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark KJ, Cronan JJ, Scola FH. Color Doppler sonography: anatomic and physiologic assessment of the thyroid. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23:215–23. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870230403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazzaferri EL. Management of solitary thyroid nodule. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:553–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302253280807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yousem DM, Scheff AM. Thyroid and parathyroid. In: Som PM, Curtin HD, editors. Head and Neck Imaging. third edn. St Louis: Mosby; 1996. pp. 953–75. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keston Jones M. Management of nodular thyroid disease. Br Med J. 2001;323:293–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh RM, Watkinson JC, Franklyn J. The management of the solitary thyroid nodule: a review. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1999;24:388–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1999.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giuffrida D, Gharib H. Controversies in the management of cold, hot, and occult thyroid nodules. Am J Med. 1995;99:642–50. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpi A, Nicolini A, Sagripanti A. Protocols for the preoperative selection of palpable thyroid nodules. Review and Progress. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:499–504. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199910000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freitas JE, Freitas AE. Thyroid and parathyroid imaging. Semin Nucl Med. 1994;24:234–45. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2998(05)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King AD, Ahuja AT, To EW, Tse GM, Metreweli C. Staging of papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: magnetic resonance imaging vs ultrasound of the neck. Clin Radiol. 2000;55:222–6. doi: 10.1053/crad.1999.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar H, Daykin J, Holder R, et al. Gender, clinical findings and serum thyrotrophin (TSH) measurements in the prediction of thyroid neoplasia in 1005 patients presenting with thyroid enlargement and investigated by fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) Thyroid. 1999;9:1105–9. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashcraft MW, Van Herle AJ. Management of thyroid nodules. II Scanning techniques, thyroid suppressive therapy, and fine needle aspiration. Head Neck Surg. 1981;3:297–322. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890030406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watkinson JC. The evaluation of solitary thyroid nodule. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1990;15:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1990.tb00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabel MS, Haque D, Velasco JM, Staren ED. Use of ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in the management of thyroid disease. Am Surg. 1998;64:738–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatada T, Okada K, Ishii H, Ichii S, Utsunomiya J. Evaluation of ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy for thyroid nodules. Am J Surg. 1998;175:133–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newkirk KA, Ringel MD, Jelinek J, et al. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and thyroid disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:700–5. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solbiati L, Giangrande A, De Pra L, et al. Percutaneous injection of parathyroid tumours and ultrasound guidance: treatment for secondary hyperparathyroidism. Radiology. 1985;155:607–10. doi: 10.1148/radiology.155.3.3889999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takashima S, Fukuda H, Nomura N, et al. Thyroid nodules: re-evaluation with ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23:179–84. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McIvor NP, Freeman JL, Salem S. Ultrasonography of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1993;55:303–8. doi: 10.1159/000276444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rago T, Vitti P, Chiovato L, et al. Role conventional ultrasonography and colour flow Doppler sonography in predicting malignancy in ‘cold’ thyroid nodules. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:41–6. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1380041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahuja A, Chick W, King W, Metreweli C. Clinical significance of the comet tail artifact in thyroid ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996;24:129–33. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0096(199603)24:3<129::AID-JCU4>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woolner LB, Beahrs OH, Black BM, et al. Classification and prognosis of thyroid cancer. Am J Surg. 1961;102:354–87. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(61)90527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCall A, Jarosz H, Lawrence AM, Paloyan E. The incidence of thyroid carcinoma in solitary cold nodules and in multinodular goiters. Surgery. 1986;100:1128–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagalla R, Cariso G, Midiri M, Cardinale AE. Echo-Doppler couleru et pathologie thyroidienne. J Echograph Med Ultrasons. 1992;13:44–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solbiati L, Livraghi T, Ballarati E, Ierace T, Crespi L. Thyroid gland. In: Solbiati L, Rizzatto G, editors. Ultrasound of Superficial Structures. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 49–85. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruneton JN, Normand F. Thyroid gland. In: Bruneton JN, editor. Ultrasonography of the Neck. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1987. pp. 22–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.LiVolsi VA. Pathology of thyroid disease. In: Flak SA, editor. Thyroid Disease: Endocrinology, Surgery, Nuclear Medicine and Radiotherapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 65–104. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simeone JF, Daniels GH, Mueller PR, et al. High resolution real time sonography of the thyroid. Radiology. 1982;145:431–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.145.2.7134448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solbiati L, Volterrani L, Rizzatto G, et al. The thyroid gland with low uptake lesions: evaluation with ultrasound. Radiology. 1985;155:187–91. doi: 10.1148/radiology.155.1.3883413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Propper RA, Skolnick ML, Weinstein BJ, Dekker A. The non-specificity of the thyroid halo sign. J Clin Ultrasound. 1989;8:129–32. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870080206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noyek AM, Finkelstein DM, Kirsch JC. Diagnostic imaging of the thyroid gland. In: Falk SA, editor. Thyroid Disease: Endocrinology, Surgery, Nuclear Medicine, and Radiotherapy. New York: Raven Press; 1990. pp. 952–75. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahuja AT, Chow L, Chick W, et al. Metastatic cervical nodes in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid: ultrasound and histological correlation. Clin Radiol. 1995;50:229–31. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)83475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takashima S, Morimoto S, Ikezoe J, et al. CT evaluation of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:61–3. doi: 10.2214/ajr.154.5.2108546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Compagno J. Diseases of the thyroid. In: Barnes L, editor. Surgical Pathology of the Head and Neck. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1985. pp. 1435–86. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaufman FR, Roe TF, Isaacs H Jr, Weitzman JJ. Metastatic medullary carcinoma in young children with mucosal neuroma syndrome. Pediatrics. 1982;70:263–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Norton JA, Froome LC, Farrell RE, Wells SA Jr. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIb: the most aggressive form of medullary carcinoma. Surg Clin North Am. 1979;59:109–18. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41737-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tambouret R, Szyfelbein WM, Pitman MB. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the thyroid. Cancer. 1999;87:299–305. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991025)87:5<299::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams ED, Doinach I, Bjarnason O, Michie W. Thyroid cancer in an iodide rich area. Cancer. 1977;39:215–22. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197701)39:1<215::aid-cncr2820390134>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin JD, Hsueh C, Chao TC, Weng HF, Huang BY. Thyroid follicular neoplasms diagnosed by high-resolution ultrasonography with fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:687–91. doi: 10.1159/000332685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ahuja AT, King W, Metreweli C. Role of ultrasonography in thyroid metastases. Clin Radiol. 1994;49:627–9. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81880-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anscombe AM, Wright DH. Primary malignant lymphoma of the thyroid – a tumour of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue: review of seventy-six cases. Histopathology. 1985;9:81–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1985.tb02972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burke JS, Butler JJ, Fuller LM. Malignant lymphomas of the thyroid. Cancer. 1977;39:1587–602. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197704)39:4<1587::aid-cncr2820390434>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]