Abstract

Loss of hypocretin cells or mutation of hypocretin receptors causes narcolepsy. In canine genetic narcolepsy, produced by a mutation of the Hcrtr2 gene, symptoms develop postnatally with symptom onset at 4 weeks of age and maximal symptom severity by 10–32 weeks of age. Canine narcolepsy can readily be quantified. The large size of the dog cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cerebellomedullary cistern allows the withdrawal of sufficient volumes of CSF for accurate assay of hypocretin levels, as early as postnatal day 4. We have taken advantage of these features to determine the relation of CSF hypocretin levels to symptom onset and compare hypocretin levels in narcoleptic and normal dogs. We find that by 4 days after birth, Hcrtr2 mutants have significantly higher levels of Hcrt than normal age- and breed-matched dogs. These levels were also significantly higher than those in adult narcoleptic and normal dogs. A reduction followed by an increase in Hcrt levels coincides with symptom onset and increase in the narcoleptics. The Hcrtr2 mutation alters the normal developmental course of hypocretin levels.

Doberman pinschers with a mutation of the hypocretin/orexin (Hcrt) receptor 2 (Hcrtr2 mutants) show cataplexy, sleepiness and responses similar to human narcoleptics to drugs that alter symptom expression (Nishino & Mignot, 1997; Aldrich, 1998; Riehl et al. 1998; Lin et al. 1999). Mice with a knockout of the preprohypocretin gene or with knockouts of the Hcrtr1 or Hcrtr2 genes also show symptoms of narcolepsy as adults (Chemelli et al. 1999; Kisanuki et al. 2000; Willie et al. 2003). Most cases of human narcolepsy are caused by a loss of Hcrt cells (Peyron et al. 2000; Thannickal et al. 2000a). Neurotoxic (saporin) lesion of the Hcrt cells in rats also causes symptoms of narcolepsy (Gerashchenko et al. 2001).

Symptoms of cataplexy in canine genetic narcolepsy are not present at birth. Rather they appear at 4 weeks of age and progressively increase in intensity, reaching adult levels by 6 months of age (Riehl et al. 1998). We and others have shown that Hcrtr2 mutant narcoleptic dogs have normal numbers of Hcrt cells and normal levels of Hcrt as adults (Thannickal et al. 2000b; Ripley et al. 2001; Wu et al. 2002). Canine narcoleptics have several unique advantages for the investigation of the effects of Hcrt mutations. The developmental time course of symptoms in these animals has been thoroughly investigated and can easily be quantified. In contrast to Hcrt mutant mice, adequate amounts of CSF for Hcrt assay can be extracted at an early developmental age, allowing the study of the developmental changes in Hcrt levels in parallel with the behavioural changes in cataplexy tendency. In the present study we have examined the development of cataplexy in relation to changes in Hcrt levels.

Methods

Animals

This study was carried out on genetically narcoleptic (Lin et al. 1999) and normal Doberman pinschers in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal use protocols were approved by the Animal Research Committee of the University of California at Los Angeles and by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Health Care System.

CSF collection and hypocretin assay

Thirty-two narcoleptic (18 puppies from 4 litters and 14 adults from 5 litters) and 20 normal dogs (14 puppies from 2 litters and 6 adults from 3 litters) were used in this study. CSF was collected from the narcoleptic (10 male, 8 female) and normal puppies (5 male, 9 female) at 4 days and at 2, 4, 6, 8 10, 14, 18, 26 and 32 weeks after birth under isoflurane anaesthesia and aseptic conditions. CSF was also collected from narcoleptic adults and normal adult dogs under thiopental sodium anaesthesia (12.5 mg kg−1, i.v.).

All CSF collections were done between 9.00 and 10.30 h to minimize circadian effects on Hcrt levels. Collections were performed before the morning meal in the adult dogs (food was given after the collection), whereas narcoleptic and normal puppies were nursed ad libitum until they were anaesthetized for the collection. In all cases, CSF was collected from the cerebellomedullary cistern. After disinfecting the area with application of a surgical scrub and 70% alcohol, a 22 or 20 gauge, 3.8 or 8.9 cm spinal needle was inserted perpendicular to the skin in the mid-line half-way between the occipital protuberance and the line joining the wings of the atlas. Once the cistern was punctured, 0.3–1.0 ml CSF was collected in a sterilized polypropylene vial within 5 min of induction of anaesthesia and then quickly frozen at −20°C. Vital signs (electrocardiogram, oxygen saturation, respiration and temperature) were monitored and kept within normal limits during and after the procedure.

Samples (0.3–0.5 ml) were acidified with 1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA) and loaded onto a C18 SEP-Column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The peptide was eluted with 1% TFA–40% acetonitrile. The eluant was then dried and resuspended in RIA buffer (0.15 m K2HPO4, 0.2 mm ascorbic acid, 0.1% Tween-20, 0.1% gelatin and red phenol). The solid-phase radioimmunoassay (Maidment & Evans, 1991) provided an IC50 of 2–3 fmol and a limit of detection of ∼0.1 fmol. The Hcrt-1, iodinated Hcrt-1, and Hcrt-1 antiserum were obtained from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Belmont, CA, USA), catalogue no. RK-003-30. Hcrt-1 and Hcrt-2 are cleaved from the same precursor peptide and are generally thought to be found in the same neurones (De Lecea et al. 1998; Sakurai et al. 1998). Hcrt-2 is much less stable than Hcrt-1 (Kastin & Akerstrom, 1999) and was not measured in the present study.

Cataplexy testing

The onset and development of cataplexy was monitored from birth in narcoleptic puppies (n = 8). Cataplexy is defined as an abrupt loss of muscle tone occurring in the alert waking state. During cataplexy, eyes typically remain open, animals are able to track moving objects and appear alert. Dogs display both partial and complete cataplexy. During partial cataplexy, only the hindlimbs collapse, and the episodes typically last less than 5 s. In complete cataplexy, all four limbs collapse and the whole body contacts the floor. Complete attacks last from 10 to as long as 90 s. Cataplexy normally terminates with the dog lifting its head up from the floor and demonstrating increased muscle tone.

In this study, puppies were observed for 1 h per day between noon and 16.00 h to detect spontaneous episodes of cataplexy. If spontaneous cataplexy did not occur, we attempted to induce cataplexy for an additional 15 min by the introduction of soft food, novel toys and play objects (John et al. 2000). The modified food-elicited cataplexy test (mFECT) measures the time it takes to consume a fixed amount of food (Pedigree by Kalkan Foods, Vemon, CA, USA) and the number of cataplexy attacks that occur (John et al. 2000). A non-symptomatic animal eats the food in a minimal amount of time. However, a symptomatic animal has cataplectic attacks elicited by food consumption. These attacks increase the time taken to complete the mFECT.

Results

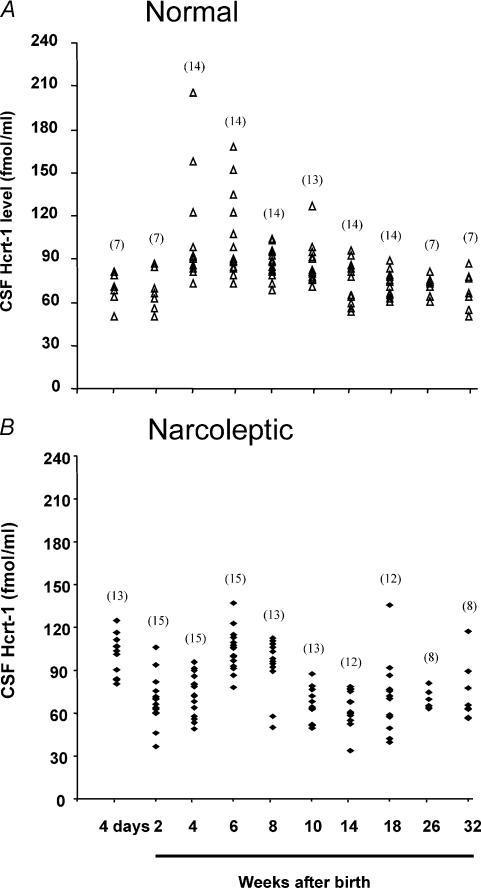

CSF Hcrt-1 concentration was monitored from 4 days after birth in both normal and narcoleptic Doberman pinschers (Figs 1 and 2A). The data were subjected to two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors of genotype (normal or narcoleptic) and age. There was an overall difference in Hcrt-1 concentration as a function of age (F9,126 = 17.1, P < 0.0001). This variation differed between the normal and the narcoleptic animals (interaction between age and genotype of dog, F9,126 = 10.1, P < 0.0001).

Figure 1. Developmental changes in CSF Hcrt-1 concentration in normal (A) and narcoleptic puppies (B).

CSF Hcrt-1 levels measured from 4 days to 32 weeks after birth. The number of dogs used for each time point is indicated in parentheses.

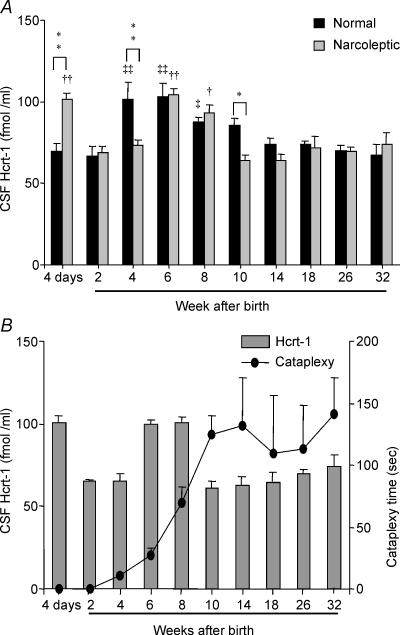

Figure 2. Developmental changes in CSF Hcrt-1 concentration and cataplexy.

A, comparison of changes in Hcrt-1 concentration (means + s.e.m.) in normal and narcoleptic puppies. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to values of normal and narcoleptic dog at each time point (same age group); †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 compared with 32-week-old narcoleptic dog; and ‡P < 0.01, ‡‡P < 0.01 compared with 32-week-old normal dog. B, developmental changes in cataplexy and Hcrt-1 monitored in a subgroup of narcoleptic dogs (n = 8). The reduced level of CSF Hcrt-1 concentration compared to age-matched normal dogs (A) coincides with the onset of cataplexy (•) between the second and fourth postnatal week. The severity of cataplexy reaches its peak and remains high from the tenth postnatal week onward, continuing into adulthood.

Normal dogs: developmental variation of CSF Hcrt-1 concentration

CSF collected from normal Doberman puppies at 4 days after birth had Hcrt levels comparable to those seen in normal adults. These levels then increased significantly from those 4 days after birth by 4 weeks and remained significantly higher at 6 and 8 weeks (P < 0.01, P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively; Tukey–Kramer test; Figs 1 and 2). Hcrt-1 levels at 4–8 weeks after birth were 30–53% higher than those 4 days after birth. Levels declined after 6–8 weeks of age, diminishing to adult levels by 10 weeks (Figs 1A and 2A).

Narcoleptic dogs: developmental variation of CSF Hcrt-1 concentration and cataplexy

In narcoleptic puppies, CSF Hcrt-1 concentration at 4 days of age (101.5 ± 3.9 fmol/ml) was significantly elevated relative to narcoleptic adult levels (P < 0.01; Tukey–Kramer test). The Hcrt-1 levels in narcoleptics were also significantly higher at 6 and 8 weeks (41 and 26%, respectively; P < 0.01, P < 0.05, respectively; Tukey–Kramer test; Figs 1B and 2A) as compared to levels in adult narcoleptics. A significant reduction in Hcrt-1 concentration from levels at 4 days was seen at 2 and 4 weeks of age (P < 0.01, P < 0.01, respectively; Tukey–Kramer test).

Cataplexy onset was observed at about 4 weeks after birth and the severity of cataplexy increased with age, reaching a plateau at the adult level by 10–14 weeks (Fig. 2B).

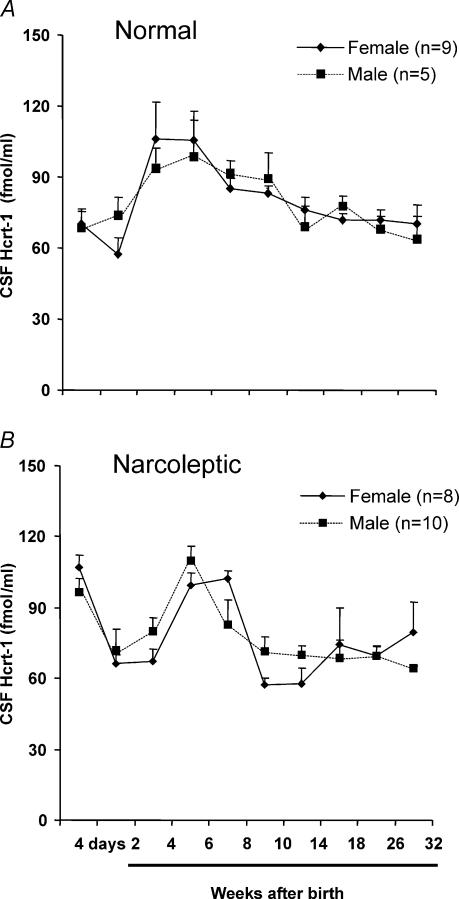

The trend of changes in Hcrt-1 during development did not differ significantly between males and females in either normal or narcoleptic dogs (Figs 3A, B). The age of onset and severity of cataplexy did not differ between male (n = 3) and female (n = 5) narcoleptic dogs. Cataplexy levels at four weeks in male (15.7 ± 2.0 s) and female (7.1 ± 4.0 s) narcoleptics were not significantly different. The severity of cataplexy by 32 weeks in male (147.4 ± 39.8 s) and female narcoleptics (137.3 ± 45.0 s) was also comparable.

Figure 3. Developmental variation of CSF Hcrt-1 concentration in male and female dogs.

Hcrt-1 levels measured from 4 days to 32 weeks after birth. A, normal dogs; B, narcoleptic dogs. The variation of Hcrt-1 throughout development is similar in male and female puppies in both the normal and narcoleptic group.

Narcoleptic versus normal dogs

At 4 days after birth the Hcrt-1 levels in narcoleptic puppies were significantly higher than those in the normal puppies (P < 0.01; Tukey–Kramer test: Fig. 2A). However, at 4 and 10 weeks after birth CSF Hcrt-1 levels were significantly lower in narcoleptic dogs compared to normal dogs (P < 0.01 and P < 0.01, respectively; Tukey–Kramer test). Although there are three outliers in the normal dog group (at 4 weeks), they are not the cause of the significant elevation we detected. There is significant elevation of Hcrt-1 even if these three values are excluded (t = 2.6, d.f. = 24, P < 0.02; t test). This demonstrates that narcoleptic puppies have a low level of Hcrt at this time point compared to the age-matched normal animals. The time point of cataplexy onset coincides with a significantly lower level of Hcrt-1 in narcoleptic dogs compared to age-matched normal dogs (Fig. 2). From 14 weeks on, Hcrt-1 concentration in normal (66.1 ± 2.3 fmol ml−1) and narcoleptic Dobermans (67.9 ± 2.7 fmol ml−1) did not differ significantly.

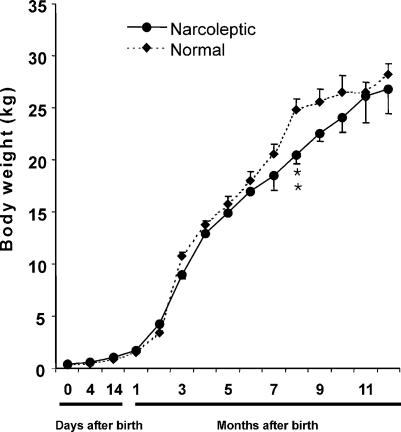

The birth weight did not differ significantly between normal (394 ± 15.2 g) and narcoleptic dogs (423 ± 11.6 g). The weight throughout development was also not different between narcoleptic and normal dogs overall, but normal dogs weighed significantly more than narcoleptic animals at 8 months of age (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Developmental changes in body weight in normal and narcoleptic Doberman Pinchers.

There was no significant difference in body weight between normal and narcoleptic animals over development. Although normal dogs had somewhat higher weights between 7 and 12 months, the number of dogs available at these ages was reduced and this difference was significant only at 8 months. **P < 0.01 compared to normal.

Discussion

An earlier study concluded that cataplexy onset in Hcrtr2 mutant dogs was linked to a progressive postnatal decrease of Hcrt levels in the narcoleptic canines (Ripley et al. 2001). Our present findings show a more complex relationship between cataplexy onset and Hcrt levels. Both normal dogs and Hcrtr2 mutants show a significant increase in Hcrt levels between birth and 6–8 weeks of age. Hcrtr2 mutants differ from the controls in their significantly elevated Hcrt levels at birth, their significantly decreased levels at 4 weeks of age and their significantly decreased levels at 10 weeks of age. Cataplexy symptom onset begins at 4 weeks of age and increases during elevation of Hcrt levels between 6 and 8 weeks of age and its subsequent diminution after 8 weeks of age.

The high levels of Hcrt 4 days after birth in narcoleptic puppies relative to the levels seen in control animals suggest that the absence of a functional Hcrtr2 caused an increase in Hcrt release throughout the period before and or immediately after birth. The onset of cataplexy symptoms during development (at 4 weeks of age) coincided with a significantly lower level of Hcrt compared to age-matched normal dogs (Fig. 2). We have reported that in adults Hcrt supplementation reduces cataplexy (John et al. 2000), consistent with the idea that the developmental fall in Hcrt levels may be linked to cataplexy onset. We also find that exercise, which elevates Hcrt levels, is associated with a reduction in the frequency and intensity of cataplexy (John et al. 2003). Activation of the Hcrtr1 receptors in the locus coeruleus neurones (Kiyashchenko et al. 2001; Willie et al. 2003) is particularly important in the suppression of cataplexy. Conversely, lesions that destroy Hcrt neurones cause symptoms of narcolepsy in rodents (Gerashchenko et al. 2001; Hara et al. 2001; Beuckmann et al. 2004) and the loss of Hcrt neurones is strongly associated with narcolepsy in humans (Thannickal et al. 2000a).

Although a low level of Hcrt coincided with onset of cataplexy in the Hcrtr2 mutant dogs, cataplexy continued to occur and to increase in intensity as Hcrt levels rose (Fig. 2). Other unobserved developmental changes in monoaminergic and amino acid transmitter levels secondary to the Hcrtr2 mutation are likely to contribute to the observed symptoms. Similarly, the relatively uncommon cases of human narcolepsy with normal Hcrt levels (Nishino et al. 2000) suggest that damage to other systems or reduced Hcrt input to other systems may produce symptoms of narcolepsy without a reduction of CSF Hcrt levels. Thus more studies monitoring other neurotransmitters in addition to Hcrt need to be done to enable understanding of cataplexy development and intensity. Our earlier studies in Hcrtr2 mutant narcoleptic dogs showed signs of neuronal degeneration at 4 weeks of age in the hypothalamus, amygdala and other regions, relative to age- and breed-matched controls (Siegel et al. 1999). The transmitter phenotype of the degenerating neurones remains to be determined.

Hcrt levels change with development in rodents. A low level of Hcrt mRNA was detected as early as embryonic day 18 and the concentration increased dramatically after the third postnatal week (De Lecea et al. 1998). In rats, prepro-orexin mRNA was present at a low level in the lateral hypothalamic area from 0 to 15 days, and markedly increased between postnatal days 15 and 20 (Yamamoto et al. 2000). Hcrt2 mRNA is significantly higher at day 20 postnatally than it is at other ages in rats (Volgin et al. 2002). There is an age-related decline in Hcrt2 mRNA levels in mouse hippocampus and brainstem regions from age 12–24 months (Terao et al. 2002). Hcrt mRNA expression is elevated about 2-fold in adult Hcrt2 knockout mice even though there is no change in whole brain Hcrt peptide levels (Willie et al. 2003). Narcolepsy symptom onset is reported by 3 weeks of age in Hcrt ligand knockout mice (Chemelli et al. 1999).

We find no difference between the rate of weight gain or weight of the Hcrtr2 mutant dogs and breed-matched controls raised under the same conditions. In other work we have shown that food deprivation and food intake has relatively minor effects on Hcrt levels (Wu et al. 2002). Others have shown that Hcrt ligand knockout mice are normal in weight (Chemelli et al. 1999). Thus the present results are in agreement with prior findings indicating that the Hcrt system is not required for weight regulation within the normal range.

The present results show that the intensity of cataplexy can be dissociated not only from the presence of the mutated receptor, which is presumably non-functional throughout the lifespan of the animal (Lin et al. 1999) but also from the Hcrt level. We have also recently reported a dramatic suppression of cataplexy throughout the lifespan in Hcrtr2 mutated narcoleptic dogs when they are immunosuppressed from birth (Boehmer et al. 2004). Together these studies demonstrate that factors other than Hcrt receptor function largely determine symptom severity in narcoleptic dogs. Although the mutation in the receptor is clearly the ultimate cause of the disorder, changes produced in non-Hcrt systems by the mutation are likely to play the major role in symptom expression. Similarly, in human narcolepsy, patients with an apparently identical loss of Hcrt can have varying intensity of symptoms (Thannickal et al. 2000a; Nishino et al. 2000). A better understanding of these changes resulting from Hcrt cell loss or receptor dysfunction might have important therapeutic implications.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Januz Jawien, Robert Nienhuis and Kristi Alderman for their help with animal care and technical assistance. This work was supported by the Medical Research Service of the US Department of Veterans Affairs, and USPHS grants NS14610, MH64109 and HL41370.

References

- Aldrich MS. Diagnostic aspects of narcolepsy. Neurology. 1998;50:S2–S7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.2_suppl_1.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuckmann CT, Sinton CM, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Hammer RE, Sakurai T, et al. Expression of a poly-glutamine-ataxin-3 transgene in orexin neurons induces narcolepsy-cataplexy in the rat. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4469–4477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5560-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer LN, Wu MF, John J, Siegel JM. Pharmacological treatment delays onset of canine narcolepsy and reduces symptom severity. Exp Neurol. 2004;188:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli RM, Willie J, Sinton C, Elmquist J, Scammell T, Lee C, et al. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lecea L, Kilduff T, Peyron C, Gao XB, Foye PE, Danielson PE, et al. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerashchenko D, Kohls MD, Greco M, Waleh NS, Salin-Pascual R, Kilduff TS, Lappi DA, Shiromani PJ. Hypocretin-2-saporin lesions of the lateral hypothalamus produce narcoleptic-like sleep behavior in the rat. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7273–7283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07273.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara J, Beuckmann CT, Nambu T, Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, et al. Genetic ablation of orexin neurons in mice results in narcolepsy, hypophagia, and obesity. Neuron. 2001;30:345–354. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John J, Wu M-F, Maidment N, Lam HA, Boehmer LN, Patton M, Siegel JM. Society for Neuroscience. Washington DC, USA: 2003. Exercise/locomotor activity increases CSF hypocretin-(orexin-A) level and reduces cataplexy in canine narcoleptics. Program No. 341.4 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. [Google Scholar]

- John J, Wu M-F, Siegel JM. Systemic administration of hypocretin-1 reduces cataplexy and normalizes sleep and waking durations in narcoleptic dogs. Sleep Res Online. 2000;3:23–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastin AJ, Akerstrom V. Orexin A but not orexin B rapidly enters brain from blood by simple diffusion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:219–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanuki Y, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Hammer RE, Yanagisawa M. The role of orexin receptor type-1 (OX1R) in the regulation of sleep. Sleep. 2000;23:A91. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyashchenko LI, Mileykovskiy BY, Lai YY, Siegel JM. Increased and decreased muscle tone with orexin (hypocretin) microinjections in the locus coeruleus and pontine inhibitory area. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2008–2016. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Faraco J, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qui X, et al. The REM sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maidment NT, Evans CJ. Microdialysis in the Neurosciences. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 1991. Measurement of extracellular neuropeptides in the brain: microdialysis linked to solid phase radioimmunoassays with subfemptomole limits of detection; pp. 275–303. [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S, Mignot E. Pharmacological aspects of human and canine narcolepsy. Prog Neurobiol. 1997;52:27–78. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S, Ripley B, Overeem S, Lammers GJ, Mignot E. Hypocretin (orexin) deficiency in human narcolepsy. Lancet. 2000;355:39–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, Ripley B, Overeem S, Charnay Y, et al. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat Med. 2000;6:991–997. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehl J, Nishino S, Cederberg R, Dement WC, Mignot E. Development of cataplexy in genetically narcoleptic dobermans. Exp Neurol. 1998;152:292–302. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripley B, Fujiki N, Okura M, Mignot E, Nishino S. Hypocretin levels in sporadic and familial cases of canine narcolepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:525–534. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, et al. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM, Nienhuis R, Gulyani S, Ouyang S, Wu M-F, Mignot E, et al. Neuronal degeneration in canine narcolepsy. J Neurosci. 1999;19:248–257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00248.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terao A, Apte-Deshpande A, Morairty S, Freund YR, Kilduff TS. Age-related decline in hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 messenger RNA levels in the mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332:190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000a;27:469–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal TC, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Turner K, Chestnut B, Siegel JM. Preservation of hypocretin neurons in genetically narcoleptic dogs. Sleep. 2000b;23:A296. [Google Scholar]

- Volgin DV, Saghir M, Kubin L. Developmental changes in the orexin 2 receptor mRNA in hypoglossal motoneurons. Neuroreport. 2002;13:433–436. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200203250-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie JT, Chemelli RM, Sinton CM, Tokita S, Williams SC, Kisanuki YY, et al. Distinct narcolepsy syndromes in Orexin receptor-2 and Orexin null mice: molecular genetic dissection of Non-REM and REM sleep regulatory processes. Neuron. 2003;38:715–730. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M-F, John J, Maidment N, Lam HA, Siegel JM. Hypocretin release in normal and narcoleptic dogs after food and sleep deprivation, eating, and movement. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:R1079–R1086. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00207.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Ueta Y, Hara Y, Serino R, Nomura M, Shibuya I, Shirahata A, Yamashita H. Postnatal development of orexin/hypocretin in rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;78:108–119. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]