Abstract

In this study we investigated the roles of cytoplasmic ATP as both an energy source and a regulatory molecule in various steps of the excitation–contraction (E–C) coupling process in fast-twitch skeletal muscle fibres of the rat. Using mechanically skinned fibres with functional E–C coupling, it was possible to independently alter cytoplasmic [ATP] and free [Mg2+]. Electrical field stimulation was used to elicit action potentials (APs) within the sealed transverse tubular (T-) system, producing either twitch or tetanic (50 Hz) force responses. Measurements were also made of the amount of Ca2+ released by an AP in different cytoplasmic conditions. The rate of force development and relaxation of the contractile apparatus was measured using rapid step changes in [Ca2+]. Twitch force decreased substantially (∼30%) at 2 mm ATP compared to the level at 8 mm ATP, whereas peak tetanic force only declined by ∼10% at 0.5 mm ATP. The rate of force development of the twitch and tetanus was slowed only slightly at [ATP]≥ 0.5 mm, but was slowed greatly (> 6-fold) at 0.1 mm ATP, the latter being due primarily to slowing of force development by the contractile apparatus. AP-induced Ca2+ release was decreased by ∼10 and 20% at 1 and 0.5 mm ATP, respectively, and by ∼40% by raising the [Mg2+] to 3 mm. Adenosine inhibited Ca2+ release and twitch responses in a manner consistent with its action as a competitive weak agonist for the ATP regulatory site on the ryanodine receptor (RyR). These findings show that (a) ATP is a limiting factor for normal voltage-sensor activation of the RyRs, and (b) large reductions in cytoplasmic [ATP], and concomitant elevation of [Mg2+], substantially inhibit E–C coupling and possibly contribute to muscle fatigue in fast-twitch fibres in some circumstances.

The cytoplasmic [ATP] is very important in all cells because it is ATP hydrolysis that provides the energy for vital cellular processes. ATP may also act as a regulatory molecule. In resting skeletal muscle fibres the cytoplasmic [ATP] is ∼7–8 mm (expressed per litre cytoplasmic water), and it is maintained near this level in most circumstances by aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis, and in the short term, by the creatine kinase reaction, which utilizes the high concentration of creatine phosphate (PCr) normally present (∼40 mm) (Fitts, 1994; Allen et al. 1995). However, it has been recently shown that when human subjects perform a fatiguing 25-s maximal cycling bout, the [ATP] in fibres containing type IIX myosin heavy chain drops to as low as 0.7–1.7 mm (2–5 μmol (g dry weight)−1) (Karatzaferi et al. 2001). This immediately raises the question of what effect such low cytoplasmic [ATP] has on the various steps in the excitation–contraction (E–C) coupling process in skeletal muscle fibres and in particular whether a low [ATP] and the associated changes could contribute to muscle fatigue.

Muscle fatigue is the term used to describe the decrease in force and power output that occurs with activity, and it is clear that muscle fatigue has many forms and many causes (Fitts, 1994; Allen et al. 1995). In certain circumstances, in particular with high frequency stimulation, muscle force can decline at least in part owing to failure of excitability, that is, failure in the generation and propagation of action potentials (APs) on the sarcolemma and in the transverse tubular (T-) system, caused by changes in the electrochemical gradients for K+ and Na+ (Sejersted & Sjøgaard, 2000; Nielsen et al. 2004). With repeated or strenuous activity, force can also decline because of changes in the ‘metabolic state’ of the cytoplasm. This is due to the high usage of ATP which, depending on the relative contributions of aerobic and anaerobic pathways of ATP re-synthesis, can cause various changes including decreased levels of PCr, ATP and glycogen, and increased levels of inorganic phosphate (Pi), H+, free Mg2+, ADP, AMP, inosine monophosphate (IMP) and lactate (Edwards et al. 1975; Nagesser et al. 1992, 1993; Karatzaferi et al. 2001). With repeated tetani, force shows an initial moderate decline to a plateau level, followed some time later by a large and steep decline (Allen et al. 1995). The initial decline is evidently due to reductions in the maximum force production and Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus, possibly caused mostly by the increased [Pi] (Allen et al. 1995; though see Debold et al. 2004). The later steep decline in force, on the other hand, is due to a decline in Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), though the cause(s) of this has not been clearly established, and quite possibly it differs in different circumstances and muscle fibre types. The decrease in Ca2+ release is evidently not caused by the rise in concentrations of H+ (Lamb et al. 1992; Lamb & Stephenson, 1994; Bruton et al. 1998; Chin & Allen, 1998), lactate (Westerblad & Allen, 1992a; Posterino et al. 2001) or IMP (Blazev & Lamb, 1999b; Laver et al. 2001). Instead, it may be the result of cytoplasmic Pi entering the SR and precipitating with Ca2+, thereby reducing the amount of Ca2+ available for rapid release (Fryer et al. 1995; Allen & Westerblad, 2001; but see Steele & Duke, 2003).

Of importance to the present study, in some circumstances reduced Ca2+ release might also be caused by low cytoplasmic [ATP] and related changes, such as the concomitant rise in free [Mg2+] (Westerblad & Allen, 1992b; Owen et al. 1996; Westerblad et al. 1998; Steele & Duke, 2003). As mentioned, measurements made in single fibres show that cytoplasmic [ATP] can drop to low levels with intense exercise in certain fibre types (Nagesser et al. 1992, 1993; Karatzaferi et al. 2001). Furthermore, as ATP usage and re-synthesis is compartmentalized, the [ATP] in local regions of high usage probably drops lower than the average level present in the cytoplasm (Korge & Campbell, 1995). In apparent support of the proposal that low cytoplasmic [ATP] limits Ca2+ release, Allen et al. (1997) found that photolysis of caged ATP produced an increase in Ca2+ release and force in fatigued fibres of the mouse. However, these authors subsequently showed that photolysis of caged ADP and caged phosphate had a similar effect, leading them to conclude that the increase in Ca2+ release resulted from the reduction in the amount of caged compound rather than the release of biologically active molecules (Allen et al. 1999).

We have previously shown, using ionic substitution to depolarize the T-system in skinned muscle fibres, that depolarization-induced Ca2+ release is inhibited substantially by either raising the free [Mg2+] in the cytoplasm from 1 mm (approximately the normal resting level, Westerblad & Allen, 1992b,c) to 3 mm (Lamb & Stephenson, 1991, 1994), or by decreasing [ATP] to 0.5 mm (Owen et al. 1996), although in mammalian muscle fibres no reduction in Ca2+ release could be detected by lowering [ATP] unless it was also accompanied by an increase in [Mg2+] (Blazev & Lamb, 1999a). However, it is not certain that these findings can be extrapolated to infer what happens in normal E–C coupling when Ca2+ release is triggered by APs. This is because (a) the voltage-sensors were activated about two orders of magnitude more slowly than with an AP (∼200 ms versus < 1 ms), and (b) the depolarization was applied for much longer (∼2–3 s versus∼2–3 ms). Thus, the ionic substitution experiments, which assessed the total amount of Ca2+ release in response to comparatively slow, prolonged stimulation, may not have detected even large differences in the rate of Ca2+ release in the various conditions. Furthermore, it is quite possible that depolarization by APs, where the whole array of voltage sensors in the T-system are activated in a rapid, co-ordinated fashion, might be a particularly potent stimulus to the apposing array of ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channels (RyRs), activating them irrespective of the prevailing cytoplasmic conditions.

In the present study we used electrical stimulation to trigger AP-induced Ca2+ release in mechanically skinned fibres (Posterino et al. 2000), and report the effects of low [ATP] and related changes on individual steps and the overall behaviour of E–C coupling. The study provides evidence that ATP must be bound to a cytoplasmic regulatory site on the RyR for the RyR to be properly activated by the voltage sensors in the T-system during physiological activation by APs. This is important for understanding the coupling mechanism between the voltage sensors and RyRs and also for identifying a possible cause of muscle fatigue in fast-twitch fibres in certain circumstances. Finally, the beneficial side of such muscle fatigue could be that it would help prevent complete exhaustion of ATP levels and the damage that otherwise may ensue.

Methods

Skinned fibre preparation and force recording

Male Long-Evans hooded rats (∼5 months old) were killed with an overdose of halothane as approved by La Trobe University Animal Ethics Committee. An extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle was excised and pinned at resting length under paraffin oil in a dish kept on an icepack. Individual fibres were mechanically skinned with jeweller's forceps and a segment (length, ∼3 mm; diameter, 30–50 μm) was mounted on a force transducer (AME801, Horten, Norway) with a resonance frequency > 2 kHz at 120% of resting length. The paraffin oil was then replaced with a Perspex bath containing 2 ml of the appropriate potassium-based solution according to whether AP-induced or Ca2+-activated force responses were being examined. Force responses were amplified with a Bioamp pod (ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia) attached to a 400 series Powerlab and simultaneously recorded on both chart recorder and computer using Chart software (version 4.2). All experiments were carried out at 23 ± 2°C.

Solutions

Unless otherwise stated all chemicals used were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St Louis, MO, USA). The standard K-HDTA solution contained (mm): hexamethylene-diamine-tetraacetate (HDTA2−, Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) 50, total ATP 8, Na+ 37, K+ 126, total Mg2+ 8.5 (giving 1 mm free [Mg2+]), PCr, 10; EGTA 0.05, Hepes 90 and N3− 1; pH 7.1 and pCa (− log10[Ca2+]) 7.0, except where stated. Low [ATP] solutions (i.e. 0.1, 0.5, 1 or 2 mm) were made by replacing appropriate amounts of ATP by PCr, with all other parameters maintained constant. This was achieved by mixing appropriate amounts of the standard solution (e.g. 8 mm ATP and 10 mm PCr) and a matching solution with no ATP and 18 mm PCr. The latter solution contained only 1.66 mm total Mg2+ so as to keep the free [Mg2+] constant at 1 mm. This amount of Mg2+ was calculated based on apparent affinity constants for Mg2+ binding to PCr, ATP and HDTA of 15 m−1, 6.9 × 10−3m−1 and 8 m−1, respectively (Stephenson & Williams, 1981). K-HDTA solutions with 3 mm free Mg2+, and various [ATP] were made in a similar way.

For examination of the properties of the contractile apparatus, solutions similar to the standard HDTA solution were made in which the 50 mm HDTA was replaced by 50 mm EGTA for strong Ca2+ buffering. The standard ‘relaxing solution’ had no added Ca2+ (pCa > 10) and the ‘maximum activation’ solution (max) had 49.5 mm added Ca2+ (pCa 4.7), with total magnesium of 10.3 and 8.1 mm, respectively, to maintain the free [Mg2+] at 1 mm (see Stephenson & Williams, 1981). These solutions were mixed in various proportions to produce solutions at intermediate pCa values. Similar EGTA solutions were also made with low [ATP] in the same manner as for the HDTA-based solutions. Free [Ca2+] of solutions in the range pCa 3–7.3 was measured with a Ca2+-sensitive electrode (Orion Research Inc, Boston, MA, USA).

Other additions to solutions

Glybenclamide (GLYB) was prepared as a 100 mm stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and then diluted 2000-fold to give a concentration of 50 μm in the final solution, with the same volume of DMSO added to the matching control solution. In experiments where exogenous creatine phosphokinase (CPK) was added, it was made up as a stock in the relevant solution at 10 times the required level and then diluted to give a CPK activity of ∼30 or 150 units ml−1 in the final solution. Adenosine stock (8 mm) solutions were prepared simply by dissolving the adenosine in either the K-HDTA standard solution or in the zero ATP-containing K-HDTA solution. This was possible because adenosine negligibly binds Mg2+. Solutions of various [adenosine] could then be made without changing the concentration of the other constituents (e.g. Mg2+, PCr, HDTA, Na+, K+, etc.) in the final test solution. There was only a very slight increase in osmolality (and no change in the ionic strength), and this would have had negligible effects on the properties of either the contractile apparatus or Ca2+ release (Lamb et al. 1993).

The amount of Ca2+ released by an AP was assayed in the appropriate K-HDTA solutions (control and low [ATP]) with the addition of 50 μm 2,5-di-tert-butyl-1, 4-hydroquinone (TBQ), a blocker of the SR Ca2+-ATPase, and set amounts of the fast Ca2+-buffer BAPTA (120–200 μm) (and with all EGTA omitted). A 50 mm TBQ stock solution (dissolved in DMSO) was diluted 1000-fold in the final solution. BAPTA (Molecular Probes, OR, USA) was added from a 50 mm stock that was similar to the standard K-HDTA solution except that all 50 mm HDTA was replaced by BAPTA.

AP-induced force responses triggered by transverse electric field stimulation

When examining twitch and tetanic force responses, the skinned fibre segment was bathed in the standard (weakly Ca2+-buffered) K-HDTA solution (8 mm ATP, 1 mm free Mg2+, 50 μm EGTA, pCa 7.0). The segment was positioned midway between two platinum stimulating electrodes and electric field pulses (duration, 2 ms; 70 V cm−1) were applied by an in-house stimulator in order to generate APs in the sealed T-system (see Posterino et al. 2000). Twitch and tetanic force responses were elicited with single pulse and 50 Hz stimulation, respectively. When measuring the effect of a given treatment (e.g. lowered [ATP] or raised [Mg2+]), the fibre segment was equilibrated in the appropriate solution for > 30 s and bracketing measurements were obtained in the same fibre segment under the control conditions (i.e. in the standard solution with 8 mm ATP and 1 mm free Mg2+). Where appropriate, the magnitude of the applied voltage was varied in order to ascertain the threshold for AP generation, or pairs of supra-maximal pulses were applied with the interpulse interval varied from 2 to 20 ms in order to study the refractory behaviour of AP generation.

TBQ-BAPTA assay of amount of Ca2+ released by an AP

The amount of Ca2+ released from the SR in response to an AP was determined using the technique described by Posterino & Lamb (2003). The twitch response was first measured in the standard conditions as described in the previous section. Then the fibre segment was transferred into a K-HDTA solution with 50 μm TBQ and a known [BAPTA] for 15 s before being stimulated electrically. The TBQ completely blocks uptake by the SR Ca2+-ATPase and the Ca2+ released by the AP rapidly binds to the BAPTA and the troponin C (TnC) sites on the contractile apparatus. The size of the resulting force response can then be used to quantify the total amount of Ca2+ released by the AP, as described by Posterino & Lamb (2003), with two small adjustments being made to take into account: (a) the greatly reduced amount of Ca2+ binding to ATP in the solutions with only 0.5 mm ATP (i.e. Ca2+ binding to ATP reduced by a factor of 16); and (b) the +0.2 pCa unit shift in the Ca2+ sensitivity (i.e. pCa50) of the contractile apparatus in solutions with 3 mm Mg2+ (Blazev & Lamb, 1999a). In some experiments, the SR was loaded with additional Ca2+ by bathing the fibre segment for a set period (30–60 s) in a loading solution (standard K-HDTA solution, with 1 mm total EGTA at pCa 6.7) prior to being exposed to the TBQ-BAPTA solution.

Rapid activation and relaxation of force by the contractile apparatus

When examining the steady-state Ca2+-dependence of the contractile apparatus, the freshly skinned fibre segment was activated in a set of solutions in which the [Ca2+] was heavily buffered with 50 mm EGTA at progressively higher [Ca2+] (pCa 6.7–4.7), first under control conditions (8 mm ATP and 1 mm Mg2+), then under the given test conditions (e.g. 0.5 mm ATP), and then again under control conditions, as done by Lamb & Posterino (2003). In other experiments the contractile apparatus was rapidly activated by changing the bathing solution from one with weak Ca2+ buffering (100 μm EGTA) at pCa 7.0 to one with heavy Ca2+ buffering (all HDTA replaced by 50 mm CaEGTA) at pCa 4.7. This method greatly reduces the diffusional delays limiting the rise in [Ca2+] within the skinned fibre (for details see Moisescu, 1976). The two bathing solutions (weakly and heavily Ca2+-buffered) contained the same concentration of all other constituents (e.g. PCr, ATP and Mg2+). In such experiments, the fibre segment was first treated with Triton X-100 to remove the SR and other membranous compartments (5 min exposure to 2% (v/v) Triton X-100 in relaxing solution, followed by two washes without detergent). Similar experiments were also performed in which the fibre was relaxed by rapidly lowering the [Ca2+] by exchanging a solution weakly Ca2+-buffered at pCa 5 (1 mm total EGTA) for one very strongly buffered at pCa > 10 with 50 mm free EGTA. In such experiments, all other constituents were maintained constant (e.g. at 8 mm ATP or at 0.5 mm ATP).

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as means ± s.e.m. with n indicating the number of fibres examined. Statistical significance was determined with Student's t test (1-tailed, paired or unpaired, as appropriate), with mean values considered significantly different if P < 0.05.

Results

Effect of low [ATP] on twitch and tetanic force responses

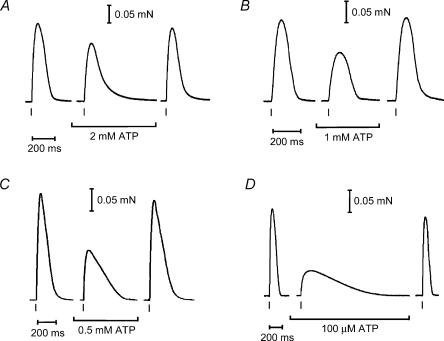

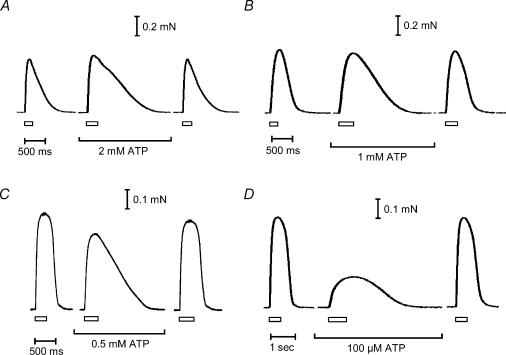

Twitch and tetanic force responses could be elicited in the skinned EDL fibres by triggering APs in the T-system with brief electric field pulses, as previously described (Posterino et al. 2000; Posterino & Lamb, 2003). When the cytoplasm contained 8 mm ATP and 1 mm free Mg2+, the tetanic response to 50 Hz stimulation typically reached close to the maximum Ca2+-activated force level measured in the same fibre (94 ± 5%, n = 43). Tetanic stimulation was always applied for a sufficiently long enough period for the force to reach its peak level under the given conditions. With the free [Mg2+] maintained at 1 mm, reducing the cytoplasmic [ATP] to very low levels caused a marked reduction in the peak size of both the twitch (Fig. 1) and tetanic (Fig. 2) responses. These responses were also slower to develop and to relax (Figs 1 and 2, summarized in Table 1). The peak of the twitch force declined progressively as [ATP] was decreased. At 2 mm ATP the peak twitch force was only ∼70% of the control level measured with 8 mm ATP, and with 100 μm ATP it was only ∼30% of the control level (Table 1). The peak tetanic force was less sensitive to reductions in [ATP], the response with 0.5 mm ATP still being ∼90% of the control level. However, when the [ATP] was decreased to 100 μm, the peak tetanic force only reached ∼47% of the control level. Both the rate of force development and the rate of relaxation of the tetanic response became substantially slower even at 2 mm ATP (∼1.4-fold and 1.7-fold, respectively) (Table 1), showing that such a reduction in [ATP] had a major effect on the response of the muscle fibres.

Figure 1. Low cytoplasmic [ATP] decreases and slows the twitch response.

A–D, representative examples of twitch responses at various low [ATP]; each panel shows data from a different skinned fibre. Unless indicated otherwise, the skinned fibre was bathed in the control conditions (8 mm ATP and 1 mm free Mg2+). Several twitches were elicited under each condition with similar results. Timing of stimulus (2 ms pulse, 70 V cm−1) is indicated by a vertical bar below each force recording. See Table 1 for mean data.

Figure 2. Effect of low cytoplasmic [ATP] on tetanic responses.

A–D, representative examples of tetanic responses at various low [ATP]; each panel shows data from a different skinned fibre. A period of 2 min was allowed between successive tetani. Period of stimulation (50 Hz) is indicated by the rectangle below each force recording; the duration of the stimulation was longer in low [ATP] to ensure that peak force was obtained. The rates of rise and decay of the tetani were slowed as [ATP] was decreased, and peak tetanic force was reduced at [ATP] ≤ 1 mm (see Table 1 for mean data).

Table 1.

Summarized data on the effect of low [ATP] on AP-induced force responses

| Treatment | n | Peak (%) | RT10–90 (%) | RFD10–90 (mN s−1) | FT90–10 (%) | RFR90–10 (mN s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twitch | ||||||

| 8 mm ATP | 82 | 100 | 100 | 8.3 ± 0.9 | 100 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

| 2 mm ATP | 7 | 71 ± 4%* | 107 ± 6% | 5.5 ± 4.7 | 136 ± 11%* | 1.7 ± 0.5* |

| 2 mm ATP + GLYB | 3 | 74 ± 16% | 106 ± 7% | 5.9 ± 4.5 | 131 ± 12%* | 1.8 ± 0.7* |

| 1 mm ATP | 24 | 66 ± 3%* | 121 ± 9%* | 4.5 ± 1.9* | 163 ± 18%* | 1.3 ± 0.5* |

| 0.5 mm ATP | 51 | 56 ± 3%* | 120 ± 4%* | 3.9 ± 0.8* | 176 ± 10%* | 1.0 ± 0.1* |

| 0.5 mm ATP + CPK | 11 | 54 ± 7%* | 128 ± 6%* | 3.5 ± 0.8* | 172 ± 17%* | 1.0 ± 0.2* |

| 0.5 mm ATP + GLYB | 3 | 61 ± 4%* | 123 ± 7%* | 4.1 ± 1.3* | 188 ± 14%* | 1.0 ± 0.2* |

| 0.1 mm ATP + GLYB + CPK | 8 | 28 ± 4%* | 182 ± 18%* | 1.3 ± 0.3* | 502 ± 18%* | 0.2 ± 0.0* |

| Tetani | ||||||

| 8 mm ATP | 43 | 100 | 100 | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 100 | 1.4 ± 0.4 |

| 2 mm ATP | 6 | 102 ± 2% | 141 ± 10%* | 3.2 ± 0.8* | 174 ± 22%* | 0.8 ± 0.3* |

| 1 mm ATP | 10 | 92 ± 3%* | 127 ± 10%* | 3.2 ± 1.2* | 245 ± 36%* | 0.5 ± 0.1* |

| 0.5 mm ATP | 27 | 90 ± 2%* | 158 ± 12%* | 2.5 ± 0.5* | 255 ± 25%* | 0.5 ± 0.1* |

| 0.5 mm ATP + CPK | 23 | 87 ± 5%* | 151 ± 17%* | 2.5 ± 0.8* | 249 ± 36%* | 0.5 ± 0.1* |

| 0.1 mm ATP + CPK + GLYB | 7 | 47 ± 7%* | 340 ± 55%* | 0.6 ± 0.1* | 456 ± 104%* | 0.2 ± 0.0* |

Twitch and tetanic force responses elicited as in Figs 1 and 2. Values are the mean ± s.e.m. in n fibres for the given parameter, as a percentage of that in 8 mm ATP. The mean twitch peak in 8 mm ATP was 58 ± 5% of maximum Ca2+-activated force, the mean rise time from 10 to 90% of peak force (RT10–90) was 29 ± 3 ms, and the mean fall time from 90 to 10% of peak force (FT90–10) was 76 ± 10 ms. The mean RT10–90 for the tetani in 8 mm ATP was 92 ± 9 ms and the mean FT90–10 was 282 ± 25 ms. The average rate of force development from 10 to 90% maximum (RFD10–90), and rate of force relaxation from 90 to 10% of maximum (RFR90–10) (both in absolute units, mN s−1) are also given. Such values, which are influenced by the changes in maximum force Ca2+-activated force occurring at the different [ATP], can be directly compared with the force responses to applied Ca2+ (Table 2). GLYB, glybenclamide (50 μm); CPK, exogenous CPK (30 units ml−1).

Significantly different from that in 8 mm ATP (paired t test). With glybencamide and CPK, data were obtained with and without treatment in the same fibre.

It should be noted that the [ATP] within the skinned fibres here is likely to be better controlled than would be the case in metabolically exhausted intact fibres at similar low [ATP]. This is because the [ATP] in the skinned fibre is continuously replenished by diffusion of the bathing solution into the fibre and, more importantly, because the low [ATP] solutions contained 16–18 mm PCr (and no creatine) which would have greatly stimulated resynthesis of ATP from ADP. Mechanically skinned fibres normally retain appreciable amounts of CPK for prolonged periods (Stephenson et al. 1999), and only ∼5% of the endogenous CPK is evidently required to support normal activity in CPK-knockout mice (Dahlstedt et al. 2003). In accord, we found that addition of 30 units ml−1 (Table 1) or even 150 units ml−1 (data not shown) of CPK had no significant effect on the reduction in twitch and tetanic force responses occurring in low [ATP].

The reduction in the AP-induced force responses at low [ATP] was evidently not caused by alterations in T-system membrane potential or AP generation. Firstly, the threshold electric field required for AP generation (detected by the sudden transition in twitch force from 0 to > 70% of maximum twitch force) was not significantly altered at low [ATP] (36.0 ± 0.8 V cm−1 with 8 mm ATP, 34.3 ± 1.3 V cm−1 with 0.5 mm ATP, n = 8 fibres; paired observations). Secondly, the refractory behaviour of the T-system AP was not detectably altered in low [ATP]. This was assessed by applying a pair of closely spaced, supramaximal pulses and determining the minimum interpulse interval required to elicit a quantal increase in force (typically ∼30%), which was indicative that the second pulse occurred sufficiently long enough after the first pulse to elicit another AP (see Fig. 3 in Posterino et al. 2003). This interval was not significantly different at 8 mm and 0.5 mm ATP (5.1 ± 0.4 ms and 5.3 ± 0.4 ms, respectively, n = 7 fibres; paired observations). This behaviour was not assessed at 100 μm ATP because the twitch response even to single pulses did not stay constant enough over the number of repetitions required. Finally, because it is known that reducing [ATP] to very low levels can open ATP-sensitive K+ channels (Fink & Lüttgau, 1976; Spruce et al. 1985), which might alter the resting membrane potential or AP, we examined the effect of glybenclamide, a potent and specific blocker of ATP-sensitive K+ channels (Light & French, 1994; Barrett-Jolley & Davies, 1997). It was found that the presence of 50 μm glybencamide did not significantly alter the effect of low [ATP] on the twitch response (see data for 2 mm and 0.5 mm ATP in Table 1; paired responses), indicating that the reduction in twitch force was not due to opening of ATP-sensitive K+ channels.

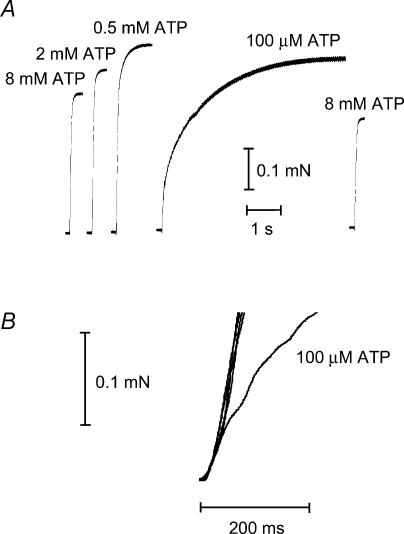

Figure 3. Force development in response to a rapid rise in [Ca2+] at various [ATP].

A, the [Ca2+] within a skinned fibre was rapidly raised by transferring the fibre from a weakly Ca2+-buffered solution (100 μm EGTA) at pCa 7.0 to a strongly buffered solution (∼50 mm CaEGTA) at pCa 4.7. The procedure was repeated with [ATP] set at each of the levels indicated. The SR and other membranous compartments were removed beforehand by treating the fibre with TritonX-100. All solutions had 30 units ml−1 exogenous CPK added. B, superimposed and expanded records of the force responses from A. The unevenness in the trace for 100 μm ATP was caused by movement during the solution exchange procedure. See Table 2 for mean data.

Effect of low [ATP] on Ca2+-activated force development by the contractile apparatus

The properties of the contractile apparatus were examined in order to ascertain whether the reduction in twitch and tetanic peak force occurring at low [ATP] was due to effects on the contractile apparatus or due to a reduction in SR Ca2+ release. First, the steady-state properties of the contractile apparatus were examined in freshly skinned fibres that had not been treated with Triton X-100, and which were thus fully comparable to the fibres used in the AP-stimulation experiments. Each fibre was exposed to sequences of heavily Ca2+-buffered solutions (50 mm total EGTA) with 8 mm ATP (control) or with 0.5 mm ATP, containing progressively higher free [Ca2+] until maximum Ca2+-activated force was achieved (at pCa 4.7) (data not shown). Force was plotted against pCa, and a Hill curve fitted individually for each condition in each fibre (as by Lamb & Posterino, 2003). In the four fibres examined, 0.5 mm ATP caused a significant potentiation of maximum Ca2+-activated force (113 ± 3%, compared to bracketing controls), but the [Ca2+] eliciting 50% of maximum Ca2+-activated force (pCa50) was unchanged (difference in pCa50, −0.004 ± 0.036 pCa units). This potentiation of maximum force without change in Ca2+ sensitivity is very similar to that found previously when decreasing [ATP] to 1 mm (Godt & Nosek, 1989).

In contrast, in six other fibres that were treated with Triton X-100 to destroy all membranes (leaving only the contractile elements), 0.5 mm ATP caused a substantial increase in Ca2+ sensitivity (change in pCa50, +0.149 ± 0.012 pCa units). The increase in maximum Ca2+-activated force in 0.5 mm ATP was no different between fibres that were treated or not treated with Triton X-100 (114 ± 5% and 113 ± 3% of that with 8 mm ATP, respectively). Of importance, when 30 units ml−1 of exogenous CPK was present in the solutions, the increase in Ca2+ sensitivity seen with 0.5 mm ATP was no longer manifested, and the pCa50 value was not appreciably different from that in 8 mm ATP (final difference in pCa50, +0.007 and +0.006 pCa units, examined in two of the six Triton X-100-treated fibres above). This strongly suggests that the endogenous CPK normally present in mechanically skinned fibres was lost during the Triton X-100-treatment and washing procedure, and that the shift in Ca2+ sensitivity was due to accumulation of ADP within the myofibrils (Godt & Nosek, 1989). It also demonstrates that the exogenously added CPK was active and sufficient to replace the endogenous CPK normally present in the skinned fibres.

The ability of the contractile apparatus to develop force in response to rapid rises in [Ca2+] was then examined, in order to make comparisons with the time course of the twitch and tetanic force responses. This was achieved by transferring the mechanically skinned fibre from a weakly Ca2+-buffered (100 μm EGTA) solution at pCa 7.0 to a heavily Ca2+-buffered (50 mm CaEGTA) solution at high [Ca2+] (pCa 4.7) (see Moisescu, 1976). The fibre segment was pre-treated with Triton X-100 to eliminate any effect of the SR on Ca2+ movements and to improve diffusional access to the contractile apparatus. With this procedure, the free [Ca2+] within the skinned fibre rises to the micromolar level within tens of milliseconds (Moisescu & Thieleczek, 1978). As seen in Fig. 3, this resulted in rapid contractile activation, with the force reaching more than 50% of maximum in less than 100 ms in the presence of 8 mm ATP. As in the measurements of steady-state activation, the level of maximum Ca2+-activated force was potentiated in low [ATP] conditions (maximum force: 115 ± 1%, n = 4; 117 ± 2%, n = 27; 127 ± 4%, n = 4; and 124 ± 8%, n = 4, compared to the control level (8 mm ATP) for 2 mm, 1 mm, 0.5 mm and 100 μm ATP, respectively). In the presence of very low [ATP] (i.e. 100 μm), the rate of isometric force development (RFD) was dramatically slowed compared to control conditions (Fig. 3 and Table 2) and appeared to exhibit at least two distinct ‘phases’ (initially the force developed rapidly but then slowed markedly). In contrast, at [ATP] ≥ 0.5 mm, the rate of force development from 10 to 50% of maximum force development (RFD10–50) was not detectably different from that under the control conditions (8 mm ATP) (Table 2). Thus, from these experiments it seems that the slowing of force development by the contractile apparatus observed at 100 μm ATP was a major factor contributing to the slow rise and reduced peak of the tetanic response under such conditions. With 0.5–2 mm ATP, it appeared that the rate of force development by the contractile apparatus was not greatly slowed; however, it is not possible to conclude that slowing of force development by the contractile apparatus played no part at all in the reduction in the twitch response at 0.5 mm ATP. This is because the highest rate of force development measured in the Ca2+-activation experiments with 0.5–8 mm ATP (RFD10–50, 2.8–3.0 mN s−1; Table 2) was evidently limited by the speed of Ca2+ diffusion into and throughout the fibre; even though the force development was quite fast, it was not as fast as the highest rate of force development measured over a comparable force range during a twitch (rate of force development from 10 to 90% maximum (RFD10–90), 8.3 mN s−1; Table 1). The rate of force development during a twitch and when applying exogenous Ca2+ would both be similarly affected by the kinetic properties of contractile apparatus events subsequent to Ca2+ binding to TnC. The faster rate of force development during a twitch stems from the fact that an AP induces within several milliseconds the release of a large bolus of Ca2+ (∼230 μmoles Ca2+ per litre fibre volume; Posterino & Lamb, 2003) at release zones less than 1–2 μm from the TnC binding sites. This pulse of Ca2+ delivered simultaneously throughout the fibre effectively ‘supercharges’ Ca2+ binding to TnC and consequently force development is even faster than when applying Ca2+ exogenously with the heavy-buffering technique. In view of this, the question of what caused the reduced twitch and tetanic responses at 0.5 mm ATP was instead addressed by determining whether there was any reduction in Ca2+ release from the SR (see later).

Table 2.

Force development by the contractile apparatus when rapidly raising [Ca2+]

| RT10–50 (%) | RFD10–50 (mN s−1) | RT10–90 (%) | RFD10–90 (mN s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 mm ATP (n = 4) | 100 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 100 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| 2 mm ATP | 119 ± 6* | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 113 ± 4* | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| 0.5 mm ATP | 125 ± 6* | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 189 ± 36 | 1.1 ± 0.2* |

| 0.1 mm ATP | 1641 ± 548* | 0.4 ± 0.2* | 3203 ± 810* | 0.1 ± 0.0* |

| 8 mm ATP (n = 27) | 100 | 3.1 ± 0.2 | 100 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| 1 mm ATP | 117 ± 3* | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 153 ± 14* | 1.0 ± 0.1* |

The contractile apparatus was directly activated by rapidly raising the [Ca2+] as shown in Fig. 3. The rise time between 10 and 50% (RT10–50) and between 10 and 90% (RT10–90) of peak force in low [ATP] were expressed as a percentage of that in control conditions (8 mm ATP) in the same fibre. The mean rate of force development (RFD) over the respective ranges is shown in units of mN s−1. Data were obtained at each of the indicated concentrations in the same fibres.

Significantly different from value in 8 mm ATP (paired t test). Exogenous CPK (30 units ml−1) was present in all solutions.

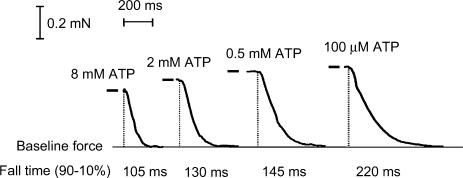

Effect of low [ATP] on force relaxation

Noting the very slow decline in the tetanic responses at low [ATP] (Fig. 2), it was also relevant to examine the rate at which the contractile apparatus relaxed when [Ca2+] was rapidly decreased. This was achieved in a manner analogous to that used to rapidly raise [Ca2+]. After treating a fibre with Triton X-100, it was activated maximally in a high [Ca2+] solution (pCa 4.7) buffered with 1 mm CaEGTA and then plunged into a zero Ca2+ solution (pCa > 10) buffered with 50 mm EGTA, with the [ATP] kept the same in both solutions. The fall time from 90 to 10% peak force (FT90–10) was examined at various [ATP] in each of four fibres with exogenous CPK present (e.g. Fig. 4) and in every case the fall time became progressively longer as [ATP] was reduced (Table 3, fibre subset 3). This direct effect of low [ATP] on the contractile apparatus suggests that a reduction in [ATP] in this range in muscle fibres would slow relaxation even if there were no reduction in the rate of Ca2+ uptake by the SR Ca2+ pump. It was also found that this slowing of relaxation was very greatly enhanced in Triton X-100-treated fibres when no exogenous CPK was added and the [ATP] was low (≤ 0.5 mm) (e.g. FT90–10 > 3 s in 100 μm ATP; see Table 3). This demonstrates the great importance of the creatine kinase reaction in keeping [ATP] from decreasing to very low levels in regions of high usage (see Discussion).

Figure 4. Relaxation upon rapidly lowering [Ca2+] is slowed at low [ATP].

Maximum force (at various [ATP]) was elicited by exposing the Triton X-100-treated fibre to a solution with moderate Ca2+ buffering (1 mm CaEGTA) at pCa 4.7. Force was then rapidly abolished by transferring the fibre (at vertical dotted line) to a very strongly buffered relaxing solution (50 mm free EGTA) at pCa > 10, with the [ATP] unchanged. The horizontal bar indicates the maximum Ca2+-activated force level in each condition. The unevenness in force traces was caused by the solution exchange procedure. The time for the response to fall from 90 to 10% of maximum (FT90–10) is shown under each trace. All solutions contained 30 units ml−1 exogenous CPK. See Table 3 for mean data.

Table 3.

Comparison of FT90–10 at the end of a tetanus and when rapidly lowering [Ca2+]

| Decline of tetanic force | Decline in force to lowered [Ca2±] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No added CPK | With CPK | No added CPK | With CPK | |

| 8 mm ATP | 282 ± 25 (43) | 357 ± 46 (20) | 170 ± 14 (15) | 172 ± 14 (13) |

| 2 mm ATP | 491 ± 146 (6) | — | — | 154 ± 14 (4) |

| 0.5 mm ATP | 718 ± 108 (27) | 771 ± 99 (23) | 347 ± 45 (8) | 216 ± 15 (12) |

| 0.1 mm ATP | — | 983 ± 200 (7) | 3186 ± 1832 (7) | 327 ± 43 (8) |

| Subset 1 | ||||

| 8 mm ATP | — | 421 ± 20 (5) | — | 215 ± 10 (5) |

| 0.5 mm ATP | — | 990 ± 191 (5) | — | 227 ± 9 (5) |

| Subset 2 | ||||

| 8 mm ATP | 276 ± 22 (7) | 278 ± 22 (7) | — | — |

| 0.5 mm ATP | 1090 ± 169 (7) | 877 ± 177 (7) | — | — |

| Subset 3 | ||||

| 8 mm ATP | — | — | — | 134 ± 16 (4) |

| 2 mm ATP | — | — | — | 154 ± 14 (4) |

| 0.5 mm ATP | — | — | — | 181 ± 18 (4) |

| 0.1 mm ATP | — | — | — | 254 ± 12 (4) |

Values are means ± s.e.m. (n fibres) for the force decline for the tetani (as in Fig. 2) and when lowering [Ca2+] to nanomolar levels by solution change (as in Fig. 4), both with and without exogenous CPK (30 units ml−1). Top section shows the grand mean for all fibres examined. Lower sets of data show three subsets of fibres where the indicated parameters were all compared in each fibre. The decline in force when lowering the [Ca2+] was considerably faster than the decline of tetanic force (subset 1). Addition of exogenous CPK did not significantly affect the decline of tetanic force (subset 2, P > 0.05). The rate of force decline when lowering [Ca2+] slowed as [ATP] was lowered (subset 3), and was much slower at low [ATP] in the absence of CPK (also confirmed by pairwise comparison in some fibres, not shown).

Table 3 also presents data on the effect of low [ATP] on the rate of relaxation after a tetanus. As mentioned earlier, the rate of relaxation slowed considerably when the [ATP] was decreased to ≤ 0.5 mm. The decline of tetanic force was not affected by addition of exogenous CPK, indicating that increasing the total amount of CPK above the amount already present in the skinned fibres conferred no benefit. It is also very apparent that the force declined more slowly after a tetanus than it did when the [Ca2+] was rapidly decreased by the solution change method. This is evident in Table 3 both from the mean data from all fibres examined and from the subset of five fibres (subset 1) in which tetanic responses were first recorded in each fibre and then the fibre was treated with Triton X-100 (and CPK added) and its response to lowering [Ca2+] recorded. The latter data show that in 8 mm ATP it took ∼200 ms longer to relax after a tetanus than it did when the [Ca2+] was rapidly decreased, and in 0.5 mm ATP this difference was ∼760 ms. At least some of the difference in the time course of force decline must be accounted for by the time taken for the SR to remove Ca2+ from the cytoplasmic space at the end of a tetanus.

Measurement of Ca2+ release with AP stimulation at different [ATP]

We next measured how much Ca2+ was released from the SR by AP stimulation at different [ATP]. This was done using the method described recently by Posterino & Lamb (2003) in which all Ca2+ uptake by the SR is blocked with TBQ and the amount of Ca2+ released by an AP is ascertained from the size of the force response produced in the presence of a known amount of the fast Ca2+ buffer, BAPTA. When all Ca2+ uptake is blocked, the [Ca2+] within the fibre declines only very slowly (time constant, > 600 ms), limited primarily by diffusion of Ca-BAPTA out of the fibre. This means that even if reduced [ATP] slows the rate of force development of the contractile apparatus to some extent, the peak of the force response should still be indicative of the total amount of Ca2+ released by an AP. It is apparent from Fig. 3B that the rate of force development in response to a rapid rise in [Ca2+] is little if at all slower in 0.5 mm ATP compared to that at 8 mm ATP, which means that the TBQ-BAPTA method should allow reliable estimation of the amount of Ca2+ released by an AP in 0.5 mm ATP. Figure 5 shows the protocol used. The amount of Ca2+ released by an AP in 0.5 mm ATP was compared to bracketing measurements of release in 8 mm ATP. Measurements were made (a) in fibres with the SR Ca2+ content close to its normal endogenous level and with 140 or 160 μm BAPTA present to chelate the released Ca2+, and (b) in fibres with the SR loaded ∼50% above the endogenous level and with 200 μm BAPTA present. The results with 8 mm ATP were similar to those obtained by Posterino & Lamb (2003): the peak amplitude of the first response in 140, 160 and 200 μm BAPTA was 53 ± 8 (n = 5), 44 ± 4 (n = 7) and 36 ± 4%(n = 10) of maximum force, respectively, corresponding to release of 210 ± 14, 218 ± 11 and 237 ± 5 μm Ca2+ (values expressed as Ca2+ per unit fibre volume; see Posterino & Lamb, 2003). When the [ATP] was reduced to 0.5 mm ATP, the amount of Ca2+ released by an AP decreased by ∼20%, irrespective of loading and buffering conditions used (release relative to bracketing measurements in 8 mm ATP: 140 μm BAPTA, 81 ± 2%, n = 5; 160 μm BAPTA, 80 ± 2%, n = 7; 200 μm BAPTA, 81 ± 3%; n = 8). This demonstrates that the ability of the voltage sensor to activate the Ca2+ release channels is adversely affected at low cytoplasmic [ATP]. This reduction in AP-induced Ca2+ release at 0.5 mm ATP accounts for much if not all of the reduction in twitch force (Fig. 1 and Table 1) (see below and Discussion).

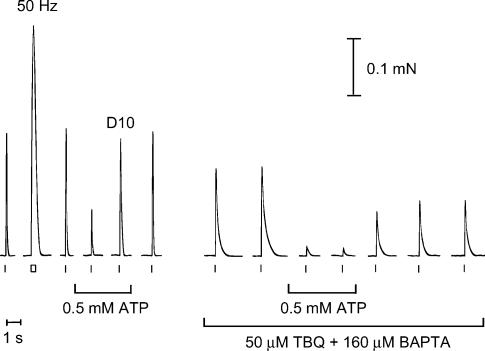

Figure 5. Assay of amount of Ca2+ released by AP-stimulation at different [ATP].

Twitch and tetanic (50 Hz) force responses were first elicited under control conditions (8 mm ATP) as in Figs 1 and 2. In the presence of 0.5 mm ATP, the twitch response (to a single pulse) reached only ∼40% of the control twitch, and a double pulse stimulus (D10; two pulses 10 ms apart to elicit two successive APs) produced a peak force that was ∼95% of that produced by a single pulse in 8 mm ATP. The same fibre was then transferred to corresponding solutions with 50 μm TBQ and 160 μm BAPTA added, and stimulated by single pulses at 15 s intervals. In TBQ-BAPTA the force response declined very slowly (∼1 s) because all Ca2+ re-uptake by the SR was blocked. The peak of the force response was indicative of the amount of Ca2+ released by the stimulus; this amount could be calculated from the size of the force response and the known amount and Ca2+-binding properties of the BAPTA and TnC (see Methods). The single AP stimuli elicited the release of ∼206 μm Ca2+ on each of the first two trials in 8 mm ATP, only ∼141 μm Ca2+ in the two trials in 0.5 mm ATP, and then ∼174–183 μm Ca2+ after returning to 8 mm ATP. Note that the presence of BAPTA meant that force was detected only when the Ca2+ release exceeded a certain threshold level, and also that the SR became progressively depleted of Ca2+ during the successive stimuli in TBQ-BAPTA. The 50 Hz tetanic response reached the maximum Ca2+-activated force level (latter not shown).

Ca2+ release in response to pairs of APs was also measured. In intact mammalian fibres, the second and subsequent APs in a train (all 10 ms apart) only release ∼25% as much Ca2+ as the first AP, apparently owing to Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the release channels (Hollingworth et al. 1996). In accord, when a skinned EDL fibre with 8 mm ATP present in the cytoplasm is stimulated by two APs (10 ms apart) rather than by a single AP, the total Ca2+ release is only increased by 25 ± 2%(n = 30) (Posterino & Lamb, 2003). When this double pulse stimulation was applied to the fibres here with 0.5 mm ATP present, the total amount of Ca2+ release was 77 ± 3% (n = 7, 200 μm BAPTA) of that released by the same double pulse stimulus in bracketing measurements in 8 mm ATP. This indicates that the amount of Ca2+ released in the low [ATP] by the second AP in a pair is reduced to a similar (or perhaps slightly greater) extent as occurred with the first AP (i.e. reduced to ≤ 80% of that at 8 mm ATP).

The above data are fully consistent with the responses observed with single and double pulse stimuli in the absence of TBQ-BAPTA. As seen in the lefthand side of Fig. 5, the peak of the force response in 0.5 mm ATP to a pair of APs 10 ms apart (D10 response) was only slightly smaller than the response to a single AP in 8 mm ATP (mean data, 95 ± 5% in 10 fibres). This fits with Ca2+ release in 0.5 mm ATP being only 80% of that in 8 mm ATP and with a pair of APs eliciting ∼25% more Ca2+ release than a single AP, as this means that the total Ca2+ released by a pair of APs in 0.5 mm ATP would be almost exactly the same as that released by a single AP in 8 mm ATP.

Effect of adenosine on twitch responses

The reduction in AP-stimulated Ca2+ release at low cytoplasmic [ATP] is most likely due to there being insufficient ATP present to saturate the stimulatory ATP-binding sites on the RyR (Ka, ∼0.4 mm ATP; Meissner et al. 1986; Laver et al. 2001). Further evidence supporting this was obtained by examining the effect of adenosine, which is a competitive weak agonist for the ATP binding site of the RyR (Duke & Steele, 1998; Laver et al. 2001). As force was used as an indicator of Ca2+ release, it was first necessary to determine whether adenosine altered the ability of the contractile apparatus to develop force. Blazev & Lamb (1999b) previously showed that 3 mm adenosine had little effect on the steady-state properties of the contractile apparatus compared to the control level without adenosine (maximum Ca2+-activated force decreased < 2%, without altering either the Hill coefficient or the pCa50). Using the rapid [Ca2+] procedure shown in Fig. 3, it was found here that addition of 2 mm adenosine to solutions with 1 mm ATP had no significant effect on either the level of maximum Ca2+-activated force or the rate of force development (maximum force, 101.8 ± 1.6%; RFD10–90, 99.8 ± 7.4%, n = 13, with adenosine compared to bracketing measurements without adenosine). This indicates that any changes in twitch force occurring in the presence of adenosine are not due to effects on the contractile apparatus, and instead must be due to changes in Ca2+ release. Twitch responses were elicited in the presence of various ratios of ATP:adenosine. As seen in the examples in Fig. 6, the presence of 2 mm adenosine had little or no effect when the [ATP] was high (8 mm) but caused progressively greater depression of the twitch response as the [ATP] was decreased. The mean peak size of the twitch response (as a percentage of the response in 8 mm ATP) for various ratios of ATP:adenosine (in mm) was 95.5 ± 2.0% (n = 3) for the 8:2 ratio, 53.6 ± 5.6% (n = 4) for the 2:2 ratio, 30.9 ± 3.5% (n = 17) for the 1:2 ratio, and 19.1 ± 2.9% (n = 7) for the 1:4 ratio. These data are fully consistent with adenosine competitively interfering with ATP binding to its stimulatory site on the RyR, thereby making the voltage sensor less effective at releasing Ca2+. The reduction in Ca2+ release in the presence of adenosine was further confirmed using the TBQ-BAPTA assay described above (with the initial Ca2+ content of the SR increased ∼50% above the endogenous level in order to make all the measurements in the sequence required before the SR became depleted of Ca2+). When 4 mm adenosine was present with 1 mm ATP the mean amount of Ca2+ released by an AP in the six fibres examined was only 131 ± 12 μm, whereas in the bracketing measurements in 1 mm ATP without adenosine in the same fibre it was 204 ± 10 μm (note the [BAPTA] had to be decreased to 120 μm in the solution with adenosine in order to observe any force response at all upon AP stimulation). Thus, decreasing the [ATP] from 8 to 1 mm reduced the amount of Ca2+ release by ∼10%, and the presence of 4 mm adenosine reduced it by approximately a further 36% (see Fig. 7).

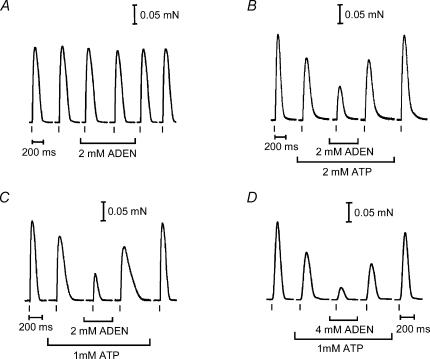

Figure 6. Effect of adenosine on the twitch response at various [ATP].

A–D, twitch responses were elicited by single 2 ms pulses as in Fig. 1. Different fibres shown in each panel. Control responses (8 mm ATP) were always produced before and after exposure to the different ratios of ATP:adenosine (ADEN). Several twitches were elicited under each condition (not shown). A, ratio 4:1 (i.e. 8 mm ATP and 2 mm ADEN). B, ratio 1:1 (2 mm ATP and 2 mm ADEN). C, ratio 1:2 (1 mm ATP and 2 mm ADEN). D, ratio 1:4 (1 mm ATP and 4 mm ADEN). Clearly, as the ratio ATP:ADEN was decreased so too was the relative peak of the twitch response.

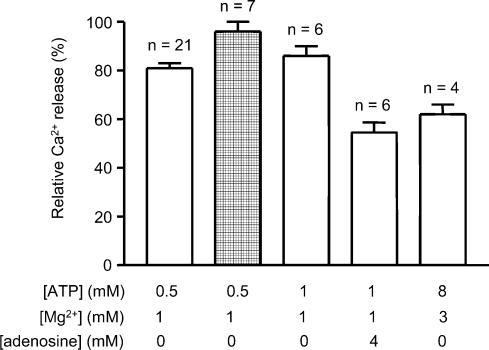

Figure 7. Relative amount of Ca2+ released by AP stimulation in different conditions.

The bars show the relative amount of Ca2+ released by a single AP (open bars) or a pair of APs (hatched bar) in the indicated conditions, expressed as a percentage of that released by a single AP in the control conditions with 8 mm total ATP and 1 mm free Mg2+. Data obtained by measurements in TBQ-BAPTA as shown in Fig. 5.

Effect of elevated free [Mg2+] on twitch and tetanic force responses

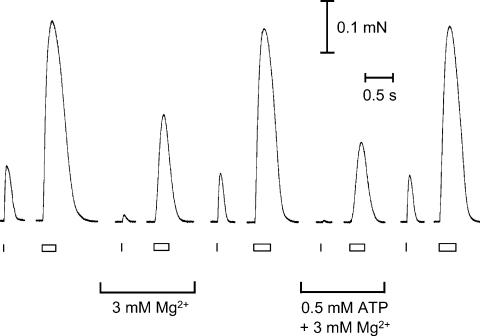

Finally, we investigated the effect of increased cytoplasmic [Mg2+] on twitch and tetanic responses, because if [ATP] in a fibre decreases to ∼1 mm the free [Mg2+] must rise very considerably (theoretically by up to ∼6 or 7 mm, depending on its buffering). As seen in the example in Fig. 8, when the free [Mg2+] was raised from the control level of 1 mm to 3 mm, with the total [ATP] kept constant at 8 mm, the peak of the twitch response was reduced about 6-fold and the tetanus reduced about 2-fold; in the 10 fibres examined, the mean twitch peak and mean tetanus peak in 3 mm Mg2+ were 15 ± 5% and 65 ± 5%, respectively, of their values in 1 mm Mg2+. When the [Mg2+] was raised to 3 mm and the [ATP] reduced to 0.5 mm, the twitch and tetanic responses were even further reduced (P < 0.05; mean twitch peak, 3 ± 2%, n = 5; mean tetanus peak, 40 ± 5%, n = 5, relative to response with 1 mm free Mg2+and 8 mm ATP). There was also a significant slowing in the rate of force development of the tetanus in the presence of 3 mm free Mg2+−8 mm ATP and 3 mm free Mg2+−0.5 mm ATP compared to the bracketing control responses (mean relative mean rise time from 10 to 90% of peak force (RT10–90), 117 ± 6% and 149 ± 13%, respectively).

Figure 8. Effect of 3 mm Mg2+ on twitch and tetanic responses at high and low [ATP].

Twitch and tetanic force responses recorded in the presence of 3 mm Mg2+ and 8 mm ATP or 0.5 mm ATP, with bracketing responses under control conditions (8 mm ATP and 1 mm Mg2+). Raising the [Mg2+] to 3 mm at constant 8 mm ATP reduced the twitch response by ∼6-fold and slowed and reduced the tetanic response by ∼2-fold. There was a greater reduction in both the twitch and tetanic response when the rise in [Mg2+] was accompanied by a decrease in [ATP] from 8 mm to 0.5 mm (see text for mean data in five fibres). Twitches elicited by single stimuli and tetani by 50 Hz stimulation (respectively indicated by ticks and rectangles under traces).

The reduction in tetanic force was due largely or entirely to a reduction in Ca2+ release and not to effects on the contractile apparatus. Maximum Ca2+-activated force was not altered in 3 mm Mg2+ (mean, 100 ± 2%; n = 5) and there was no detectable change in the rate of force development in response to a fast [Ca2+] step (applied as in Fig. 3; mean RFD10–90, 98 ± 4% of bracketing control in 1 mm Mg2+, n = 5). Previous measurements of steady-state properties showed that 3 mm Mg2+ only caused a moderate reduction in Ca2+ sensitivity (pCa50 decreased ∼0.21 pCa units, Blazev & Lamb, 1999a). When the [ATP] was decreased to 0.5 mm at 3 mm Mg2+, maximum Ca2+-activated force increased (to 125 ± 1% of that with 1 mm Mg2+−8 mm ATP, n = 5) and the rate of force development was slightly slowed (mean RFD10–90, 139 ± 17% of control, n = 5), just as seen in 1 mm Mg2+ (see earlier; Table 2). Thus, maximum Ca2+-activated force was unchanged or potentiated in 3 mm Mg2+, whereas tetanic force was markedly reduced (Fig. 8), with the disparity being greater at 0.5 mm ATP. This difference cannot be accounted for by the decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus occurring in 3 mm Mg2+, implying that Ca2+ release was inhibited. This was confirmed by measuring the amount of Ca2+ release in response to single AP stimulation with the TBQ-BAPTA assay procedure shown in Fig. 5. In the five fibres examined, it was found that Ca2+ release in 3 mm Mg2+ (with 8 mm ATP) was substantially reduced, being only 62 ± 4% of that in 1 mm Mg2+.

Discussion

This study documents the effects of low cytoplasmic [ATP] on E–C coupling in rat fast-twitch fibres, examining both the overall effects on twitch and tetanic responses, as well as the effects on individual steps in the process, in particular on AP-induced Ca2+ release and on force development and relaxation by the contractile apparatus. This was achieved using a mechanically skinned fibre preparation that retains functional E–C coupling, and in which it was possible to manipulate cytoplasmic [ATP] and other factors such as [Mg2+] independently and thus characterize their individual effects on the various processes. This enabled a parametric examination of the effects of low [ATP] on E–C coupling steps that could not be performed with intact fibres.

The force response, rather than an exogenous Ca2+ indicator, is used here to assay Ca2+ release because, even though it is a comparatively slow sensor of Ca2+ release, its dependence on cytoplasmic [Ca2+] can be accurately determined in situ under all the relevant conditions. Fluorescent and light absorbing Ca2+ indicators are the only way to gain information about the time course of rapid changes in free [Ca2+], but there can be considerable difficulties with Ca2+ saturation and with calibrating the indicators in situ to take account of their binding within the fibre and consequent changes in their properties. For example, there is currently more than a 10-fold disparity between the estimates of peak tetanic free [Ca2+] in intact fast-twitch fibres of the mouse obtained using different Ca2+ indicators (∼20 μm with furaptra, Baylor & Hollingworth, 2003; ∼1–2 μm with indo-1, Westerblad et al. 1998; Allen et al. 1999). Furthermore, such indicators show only the free [Ca2+], not the total amount of Ca2+ released, which is 10–100 times higher than the free [Ca2+] and has to be calculated based on many assumptions about the amount and properties of Ca2+ binding to various known and unknown sites within the fibre. Here, we instead assay the amount of Ca2+ release using our recently developed TBQ-BAPTA method (Posterino & Lamb, 2003) where most of the released Ca2+ binds to a known amount of exogenously applied buffer (BAPTA) and force can be used to determine the free [Ca2+] (and hence the total amount of Ca2+ on the BAPTA) because all re-uptake and Ca2+ binding by the SR Ca2+ pump is blocked with TBQ.

Effect of low [ATP] on the rise and peak of the tetanic response

It was found here that reducing the [ATP] to 0.5 mm or 1 mm, with no change in [Mg2+], caused a significant reduction in peak tetanic force (by ∼10%; Fig. 2 and Table 1). This was evidently not due to effects on the contractile apparatus; maximum Ca2+-activated force actually increased ∼15% or more and Ca2+ sensitivity was not changed. The reduction in tetanic force was instead primarily due to a reduction in AP-induced Ca2+ release (by ∼20% and 10% at 0.5 and 1 mm ATP, respectively; Fig. 7). The rate of development of tetanic force was also significantly slowed in 0.5 and 1 mm ATP (by ∼60% and 30%, respectively; Table 1). This was probably due not only to the reduced Ca2+ release, but also to slowing of the rate of force development by the contractile apparatus, which was observed in the [Ca2+] step experiments to decrease by ∼35% at such [ATP] (Table 2, RFD10–90). This is consistent with previous findings showing that the velocity of shortening in chemically skinned mammalian fast-twitch fibres dropped by ∼25% when the [ATP] was decreased from 5 mm to 0.5 mm (Cooke & Bialek, 1979).

When the [ATP] was decreased even further, to 100 μm, tetanic force was reduced very substantially (to ∼28% of that in 8 mm ATP). This was probably caused not only by a further reduction in AP-induced Ca2+, but also by the marked slowing of force development by the contractile apparatus that occurs at such [ATP], as seen in Fig. 3 and Table 2. The latter is in accord with the substantial decrease in the velocity of shortening (> 3-fold) observed at 100 μm ATP (Cooke & Bialek, 1979). Thus, muscle power production drops precipitously if the [ATP] falls to such levels.

Effect of low [ATP] on twitch responses

The force response to single APs, while not of direct physiological relevance, was also examined because it enabled quantitative comparison of the Ca2+ release and the force response to a rapid, submaximal stimulus. The twitch response was attenuated to a greater degree by low [ATP] than was the tetanic response (Table 1); this is largely a consequence of the fact that the amount of Ca2+ released by a single AP under control conditions was sufficient to only partially activate, rather than fully activate, the contractile apparatus, and hence any change in the amount of Ca2+ release had a more severe effect on the peak force reached. It was found that the twitch response to a single AP in 0.5 mm ATP decreased to ∼50% of that in 8 mm ATP (e.g. Figs 1 and 5, and Table 1), even though the amount of Ca2+ released was only reduced by ∼20% (Fig. 7). It was established that the reduced force response was indeed due to the reduction in Ca2+ release and not to changes in the response of the contractile apparatus, because stimulating the fibre with two APs in close succession in 0.5 mm ATP elicited approximately the same total Ca2+ release as a single AP in 8 mm ATP (Fig. 7) and also approximately the same peak force (Fig. 5). Thus, the data obtained with single AP stimulation in 0.5 mm ATP demonstrated that a relatively small reduction in Ca2+ release causes a much larger reduction in twitch force. This could result from a relatively large proportion of the Ca2+ released by a single AP (perhaps ∼50% or ∼110 μm) rapidly binding to sites not directly involved in force generation. Possibly many of these sites are on the SR Ca2+ pumps, because such binding appears to be lost when these sites are occluded with TBQ (Posterino & Lamb, 2003). It is also apparent that these Ca2+-binding sites are close to fully saturated by the Ca2+ released by a single AP, because most if not all of the additional Ca2+ released by the second AP in a pair (∼25% more) appears to contribute directly to force development (Fig. 5). Thus, the first AP in a train elicits considerably more Ca2+ release (∼4-fold) than the subsequent APs (Hollingworth et al. 1996; Posterino & Lamb, 2003) and this seems well designed to rapidly fill the non-force generating Ca2+-binding sites in the fibre, hence ensuring that there is adequate Ca2+ available for activating force production. In intact fibres some of this initial Ca2+ released could also bind to any free parvalbumin (i.e. that not occupied by Mg2+), but this would not have occurred in the skinned fibres here, because the parvalbumin was rapidly lost when the fibre was transferred from oil to the aqueous solution (Stephenson et al. 1999).

Effect of raised [Mg2+]

It was also found here that when the free [Mg2+] was raised from 1 to 3 mm the tetanic force response was reduced to ∼65% of its control level (e.g. Fig. 8). This is similar to the ∼50% reduction in tetanic force occurring in intact murine fast-twitch fibres when the free [Mg2+] in the cytoplasm was raised to 3 mm by injection of Mg2+ (Westerblad & Allen, 1992b). That study did not ascertain how much of the reduction in force was due to effects on the contractile apparatus and how much to a reduction in cytoplasmic [Ca2+], and even if the cytoplasmic [Ca2+] had been measured it would not have been straightforward to determine whether or to what degree the total Ca2+ release was altered. The results of the present study show that AP-induced Ca2+ release is indeed substantially reduced (by ∼40%) when the free [Mg2+] is raised to 3 mm with the total [ATP] kept unchanged. The reduction in twitch force (to ∼15%) was much larger than the reduction in the amount of Ca2+ release, which is consistent with the non-linear relationship between twitch force and Ca2+ release in 0.5 mm ATP discussed above.

When the [Mg2+] was raised to 3 mm and the [ATP] lowered to 0.5 mm, tetanic force was reduced considerably more (to ∼40% of that with 1 mm Mg2+ and 8 mm ATP), despite the fact that maximum Ca2+-activated force was substantially increased and Ca2+ sensitivity was unchanged. This indicates that Ca2+ release under these conditions was substantially lower than in 3 mm Mg2+, and hence that low cytoplasmic [ATP] augments the inhibition of Ca2+ release occurring in 3 mm Mg2+. Thus, it is likely to be the combined effect of both these factors (and possibly also an associated build-up of ADP and AMP; Blazev & Lamb, 1999a), not the rise in [Mg2+] alone, which causes the decline in Ca2+ release underlying fatigue in fast-twitch fibres (Westerblad & Allen, 1992b,c).

Voltage-sensor control of Ca2+ release through the RyRs

By assaying the amount of Ca2+ released by AP-stimulation, this study provided clear evidence that the normal physiological mechanism of releasing Ca2+ from the SR is inhibited both by lowering [ATP] (to 0.5 mm) and by raising free [Mg2+] (to 3 mm) (Figs 5 and 7). Using skinned fibres it had been previously shown that the amount of Ca2+ released by T-system depolarization by ionic substitution was inhibited by raised [Mg2+], but no significant change was found when lowering [ATP] without raising [Mg2+] (Blazev & Lamb, 1999a). Such experiments involved applying relatively slow and prolonged depolarizations (∼2–3 s, see Introduction), and consequently they would not have been able to detect whether there were changes in the rate of Ca2+ release on a physiological timescale under the various conditions. The present experiments show that even when the whole array of voltage sensors are activated in a rapid, co-ordinated fashion by an AP, their ability to open the apposing RyRs is still modulated by the prevailing cytoplasmic conditions, in particular by the [ATP] and the free [Mg2+]. It is interesting to note that raising the [Mg2+] to 3 mm caused a quantitatively similar decrease in the amount of Ca2+ released by a single AP (∼40%, Fig. 7) as occurred with a 2–3 s maximal depolarization elicited by ion substitution (∼40%; Blazev & Lamb, 1999a). Given the great differences in speed and duration of the two methods of stimulation, this similarity may seem somewhat surprising. However, such a finding would be expected if raised [Mg2+] reduces RyR open probability (and consequently Ca2+ release) by a similar proportion regardless of how rapidly or for how long the stimulation occurs. Moreover, despite its much more rapid time course, a single AP elicits the release of a substantial fraction (∼25%) of the total Ca2+ present in the SR (Posterino & Lamb, 2003), and such substantial release might be expected to show broadly similar modulation by cytoplasmic factors as occurs when releasing almost all of the SR Ca2+ by depolarization by ion substitution.

The inhibitory action of raised [Mg2+] on AP-induced Ca2+ release is almost certainly due to increased Mg2+ occupation of both the Ca2+-activation site and the low-affinity Ca2+–Mg2+ inhibitory site on the RyR (Laver et al. 1997), leading to reduced activation of the RyR by the voltage sensors (Lamb & Stephenson, 1991, 1994; Lamb, 2002). Similarly, the inhibitory action of low [ATP] is almost certainly mediated by actions on the RyR. Skeletal muscle RyRs in synthetic bilayers are activated by ATP independently of Ca2+ binding to the Ca2+-activation site, with half maximal activation at ∼0.36 mm ATP and a Hill coefficient of ∼1.8 (Laver et al. 2001). The present results showing a 20% decrease in AP-induced Ca2+ in 0.5 mm ATP is quite consistent with this if ATP must be bound to its cytoplasmic regulatory site on the RyR in order for the RyR to be properly activated by the voltage sensor (dihydropyridine receptor) molecules in the T-system during an AP. This explanation is also strongly supported by the effects of cytoplasmic adenosine, which was found to reduce AP-induced Ca2+ release in a manner fully consistent with its known action as a weak competitive agonist for the ATP regulatory site on the RyR (Laver et al. 2001). Adenosine had little or no effect on AP-induced Ca2+ release in the presence of high [ATP] (e.g. Fig. 6A) but caused progressively more inhibition as the ratio of adenosine:ATP was increased. It is interesting that the degree of inhibition of AP-induced Ca2+ release occurring both (a) when lowering [ATP] alone (20% inhibition in 0.5 mm ATP), and (b) when adding adenosine (36% relative inhibition with 4 mm adenosine at 1 mm ATP), is only about half of that observed with isolated RyRs in bilayers (Laver et al. 2001). A difference of this magnitude is perhaps not surprising given the number of differences in the two types of experimental assays. Nonetheless, it may well be that this difference mainly reflects the fact that a ‘crystalline’ array of RyRs, such as that in a muscle fibre, is more easily activated than a single isolated RyR, owing to co-operative interactions between adjacent RyRs in the array.

Effect of low [ATP] on force relaxation

A further, very prominent effect of low [ATP] was the slowing of relaxation, particularly for the tetani (Fig. 2 and Table 1). This effect, which was quite large even at 2 mm ATP, was not due to any change in the steady-state Ca2+ sensitivity of the contractile apparatus. When rapidly decreasing the [Ca2+] in Triton X-100-treated fibres, force was observed to decline relatively quickly even in 100 μm ATP (FT90–10, 250 ms) (e.g. Fig. 4), provided that exogenous CPK had been added to the bath to compensate for the loss of endogenous CPK caused by the Triton X-100-treatment (Table 3). However, when exogenous CPK was not added, the contractile apparatus displayed substantial slowing of relaxation when the bathing solution contained 0.5 mm ATP, and extreme slowing of relaxation with 100 μm ATP (FT90–10, 3000 ms; Table 3). This indicates that if the cytoplasmic [ATP] is initially ∼0.5 mm and poorly clamped by the creatine kinase reaction, as may occur in a severely exhausted fibre with almost no PCr, local depletion of ATP (and build-up of ADP) occurring near the contractile apparatus during activation is great enough to substantially modify the force response. However, such extreme effects at very low [ATP] do not readily account for the marked slowing of the relaxation of the tetanic response observed in 2 mm ATP when the [ATP] was presumably kept relatively constant by the creatine kinase reaction with 16 mm PCr present. (Note that these fibres were not treated with Triton X-100 and retained endogenous CPK (Stephenson et al. 1999) and that there was no effect of adding exogenous CPK; Table 3). One possibility is that the slowing of relaxation is due to effects of low [ATP] on the SR Ca2+ pump. In 8 mm ATP with CPK present, the tetanic response declined considerably more slowly than did the contractile apparatus when decreasing [Ca2+] directly (Table 3 subset 1: FT90–10, 421 ms and 215 ms, respectively). This difference presumably primarily reflects the additional time taken for the SR Ca2+ pump to resequester the Ca2+ in the cytoplasm at the end of the tetanus. When the [ATP] was decreased to 0.5 mm, the rate of relaxation measured in the contractile apparatus experiments only increased to a small degree (FT90–10, 227 ms), whereas that of the tetanus increased greatly (FT90–10, 990 ms). This seems to indicate that Ca2+ uptake by the SR Ca2+ pump was substantially slowed at 0.5 mm ATP, and this limited the rate of relaxation of the tetanus in the fibres here. This is consistent with studies of pump function showing that the maximum rate of Ca2+ uptake is modulated by ATP binding at a regulatory site with an apparent affinity of ∼1 mm (Dupont et al. 1985). This explanation of the slow decline of the tetanus in low [ATP] needs to be tested in future experiments by direct measurement of the time course of decline of cytoplasmic [Ca2+] with a Ca2+ indicator. Nevertheless, irrespective of its cause, the slowing of tetanic relaxation seen here in skinned fibres when the [ATP] was presumably kept close to 2 mm suggests that this effect is probably of some importance in fatigued muscle fibres. It should be borne in mind though that the slowing of the tetanic relaxation observed here at low [ATP] may well not be observed as such in an intact fibre, because when an intact fibre has been stimulated sufficiently to deplete the [ATP] to a low level, other factors, particularly the raised concentration of inorganic phosphate and free Mg2+, will also modify the overall response of the contractile apparatus and Ca2+ movements. Furthermore, the presence of parvalbumin in intact fibres may help mitigate the effects of a decline in the rate of Ca2+ uptake by the SR.

Muscle fatigue and the possible protective role of low [ATP]

Karatzaferi et al. (2001) measured PCr and ATP in various fibre types from the vastus lateralis muscle of human subjects immediately after a 25 s maximal cycling bout in which power output decreased to an approximately steady level of ∼50% of the initial level. In most fibres containing the fastest myosin heavy chain isoform (type IIX), the [ATP] dropped to between ∼0.7 and 1.7 mm. As the [ATP] presumably recovered to some degree while obtaining the biopsy (it recovered to ∼50% of control within 90 s), it is likely that the [ATP] was even lower at the end of exercise than that measured. Moreover, these values are the average levels in the cytoplasm, so given that the ATP was poorly buffered by the low PCr levels, the [ATP] in the triad junction (where there are many ATPases), and in the vicinity of the myosin heads, may well have dropped to 0.5 mm or below, with the free [Mg2+] increasing accordingly (i.e. to > 3 mm; see Westerblad & Allen, 1992b,c). The fact that the exercise regime rapidly depleted > 90% of the high energy phosphates, clearly shows that the average rate of ATP utilization over the exercise period greatly exceeded its rate of resynthesis. As the rate of recovery of ATP and PCr during the post-exercise period was very much lower than the average rate of utilization during the exercise, it has to be concluded that the rate of ATP utilization at the end of the exercise period was very much lower than the average rate during the exercise. If this were not the case and the exercise had continued even slightly longer, all cellular ATP would have been completely used up, and consequently (a) rigor force would have developed and (b) the SR Ca2+ pump would not have operated and Ca2+ would have stayed in the cytoplasm causing large-scale Ca2+-dependent damage (Lamb et al. 1995; Westerblad et al. 1998). Evidently this does not readily happen in normal exercise. Thus, the rate of ATP utilization must have been very low near the end of the exercise period and this implies a low power output. Of most importance, it also implies that there must have been very little release of Ca2+ from the SR, because ATP is consumed at a high rate during Ca2+ re-uptake into the SR (Szentesi et al. 2001). Even if myosin ATPase activity were to drop greatly, ATP could only be preserved by decreasing the rate of Ca2+ re-uptake, which means reducing Ca2+ release. Finally, as the [ATP] drops to very low levels in the type IIX fibres, but stops before actually reaching zero, it seems most likely that it is the low [ATP] itself that, directly or indirectly, causes the reduction in Ca2+ release from the SR.

The above considerations suggest that in some physiological circumstances (e.g. in strenuous exercise in the fastest twitch fibres) muscle fatigue may be caused, at least in part, by a reduction in cytoplasmic [ATP] and the concomitant rise in free [Mg2+] (possibly also compounded by local increase in ATP metabolites, ADP and AMP); this also agrees with conclusions of experiments in intact fibres from mouse and frog (Westerblad & Allen, 1992b,c). The present results show that such changes cause a large reduction in AP-induced Ca2+ release from the SR and force production, apparently by direct inhibitory effects of these changes on the responsiveness of the RyRs to activation by the voltage sensors. However, we note that the results here were obtained at room temperature, as were those concerning fatigue in mouse and frog fibres in vitro (Westerblad & Allen, 1992b,c), and we have not established that the same phenomenon occurs at mammalian body temperature, though we do expect this to be the case. In the skinned fibres here, reducing [ATP] to 0.5 mm inhibited Ca2+ release without any evident change in membrane excitability. However in some circumstances, low [ATP] may cause an additional reduction in Ca2+ release by also interfering with membrane excitability, as Duty & Allen (1995) found that in fatigued murine fast-twitch fibres addition of glybenclamide produced some degree of recovery of cytoplasmic [Ca2+] in three of the six fibres examined. Finally, it is important to note that other factors besides low [ATP] and raised [Mg2+] are likely to play a role in causing muscle fatigue in various circumstances. In particular, Pi released by PCr breakdown appears to precipitate with Ca2+ in the SR and thereby reduce Ca2+ release (Fryer et al. 1995; Allen & Westerblad, 2001). In view of this, it seems likely that this latter effect also contributes to the overall reduction in Ca2+ release that evidently occurs when fast-twitch fibres are stimulated sufficiently to deplete PCr and ATP levels, though as discussed above, it seems that it is some mechanism closely linked to cytoplasmic [ATP] itself, not [Pi], that must ultimately terminate Ca2+ release when cellular ATP is nearly completely exhausted.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor George Stephenson for helpful discussions and to the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia for financial support (grant no. 280623).

References

- Allen DG, Lännergren J, Westerblad H. Muscle cell function during prolonged activity: cellular mechanisms of fatigue. Exp Physiol. 1995;80:497–527. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DG, Lännergren J, Westerblad H. The role of ATP in the regulation of intracellular Ca2+ release in single fibres of mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1997;498:587–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DG, Lännergren J, Westerblad H. The use of caged adenosine nucleotides and caged phosphate in intact skeletal muscle fibres of the mouse. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999;166:341–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201x.1999.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DG, Westerblad H. Role of phosphate and calcium stores in muscle fatigue. J Physiol. 2001;536:657–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Jolley R, Davies NW. Kinetic analysis of the inhibitory effect glibenclamide on KATP channels of mammalian skeletal muscle. J Membr Biol. 1997;155:257–262. doi: 10.1007/s002329900178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor SM, Hollingworth S. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release compared in slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibres of mouse muscle. J Physiol. 2003;552:125–138. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazev R, Lamb GD. Low [ATP] and elevated [Mg2+] reduce depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in rat skinned skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1999a;520:203–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazev R, Lamb GD. Adenosine inhibits depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in mammalian skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve. 1999b;22:1674–1683. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199912)22:12<1674::aid-mus9>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruton JD, Lännergren J, Westerblad H. Effects of CO2-induced acidification on the fatigue resistance of single mouse fibers at 28 °C. J App Physiol. 1998;85:478–483. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.2.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin ER, Allen DG. The contribution of pH-dependent mechanisms to fatigue at different intensities in mammalian single muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1998;512:831–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.831bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R, Bialek W. Contraction of glycerinated muscle fibers as a function of the ATP concentration. Biophys J. 1979;28:241–258. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85174-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlstedt AJ, Katz A, Tavi P, Westerblad H. Creatine kinase injection restores contractile function in creatine-kinase-deficient mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2003;527:395–403. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debold EP, Dave H, Fitts RH. The fiber type and temperature dependence of inorganic phosphate: the implications for fatigue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00044.2004. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AM, Steele DS. Effects of caffeine and adenine nucleotides on Ca2+ release by the sarcoplasmic reticulum in saponin-permeabilized frog skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1998;513:43–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.043by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont Y, Pougeois R, Ronjat M, Verjovsky-Almeida S. Two distinct classes of nucleotide binding sites in sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase revealed by 2′,3′-0-(2,4,6-Trinitrocyclohexadienylidene)-ATP. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7241–7249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duty S, Allen DG. The effects of glibenclamide on tetanic force and intracellular calcium in normal and fatigued mouse skeletal muscle. Exp Physiol. 1995;80:529–541. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RH, Hill DK, Jones DA. Metabolic changes associated with the slowing of relaxation in fatigued mouse muscle. J Physiol. 1975;251:287–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]