Abstract

Arabidopsis seeds store triacylglycerol (TAG) as the major carbon reserve, which is used to support postgerminative seedling growth. Diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) catalyzes the final step in TAG synthesis, and two isoforms of DGAT have previously been identified in Arabidopsis. It has been shown that DGAT1 plays an important role in seed development because Arabidopsis with mutations at the TAG1 locus accumulate less seed oil. There is also evidence showing that DGAT1 is active after seed germination. The aim of this study is to investigate the effect of mutations of DGAT1 on postembryonic development in Arabidopsis. We carried out detailed analyses of two tag1 mutants in different ecotypic backgrounds of Arabidopsis. Results show that during germination and seedling growth, seed storage TAG degradation was not affected in the tag1 mutants. However, sugar content of the mutant seedlings is altered, and activities of the hexokinases are significantly increased in the tag1 mutant seedlings. The tag1 mutants are also more sensitive to abscisic acid, glucose, and osmotic strength of the medium in germination and seedling growth.

Germination and seedling development are critical phases in the life cycle of seed plants, during which seedlings must adapt their developmental and metabolic programs to the prevailing environmental conditions (Holdsworth et al., 1999). Seed reserves serve as an initial carbon and energy source for seedling growth (Bradbeer, 1988). Many seeds store oil, in the form of triacylglycerol (TAG), as the major reserve (Bewley and Black, 1994). The biosynthesis of TAG has been proposed to take place in the endoplasmic reticulum by the action of the acyltransferases of the Kennedy pathway (Gurr, 1980; Ohlrogge and Browse, 1995). Diacylglycerol lies at the branch point between membrane phospholipid synthesis via sn-1,2-diacylglycerol (DAG):cholinephosphotransferase and storage TAG synthesis catalyzed by diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT). DGAT catalyzes the acylation of position 3 of DAG, the final step of TAG synthesis (Ohlrogge and Browse, 1995). Two sequence-unrelated genes coding for DGAT have been cloned (Hobbs et al., 1999; Lardizabal et al., 2001). Arabidopsis mutants with mutations at the TAG1 locus encoding the DGAT1 enzyme can only accumulate about 55% to 75% (w/w) of seed triacylglycerols of the wild type (Katavic et al., 1995; Routaboul et al., 1999). Therefore, TAG1 plays an important role in TAG biosynthesis in developing seeds. The fact that the seeds can still synthesize more than one-half of their normal complement of TAG suggests that the DGAT2 gene or other mechanisms for TAG synthesis are also at work (Dahlqvist et al., 2000; Lardizabal et al., 2001).

TAG synthesis mainly occurs during the seed maturation phase before the seed enters the period of desiccation (Mansfield and Briarty, 1991). However, several lines of evidence suggest that TAG synthesis and DGAT activity are not restricted to the embryo. Developing pollen grains accumulate a large amount of TAG (Piffanelli et al., 1997); DGAT activity was also found in germinating soybean (Glycine max) cotyledons (Wilson and Kwanyuen, 1986). TAG1 transcripts have been detected in many tissues in Arabidopsis, including developing siliques, flowers, germinating seeds, and young seedlings (Zou et al., 1999). Our previous studies also detected low levels of TAG1 expression in leaves and stems, in addition to its strong expression in embryo and flowers in oilseed rape (Brassica napus; Hobbs et al., 1999). These findings raised the possibility that DGAT activity and/or TAG synthesis may also play roles during postembryonic development of the plant life cycle. To investigate these possible roles, we have carried out detailed analyses of the previously isolated tag1 mutants: the tag1-1 (AS11) from the Columbia (Col) wild type and the tag1-2 (ABX45) derived from the Wassilewskija (WS) ecotype background, respectively. Here, we demonstrate that DGAT1 deficiency causes an alteration to carbohydrate metabolism in the tag1 mutant seedlings. In addition, both mutants display increased sensitivity to ABA (abscisic acid), sugars, and stress conditions during germination and seedling development.

RESULTS

Germination and Seedling Development of the tag1 Mutants Are More Sensitive to ABA, Glc, and Osmotic Stress

As previously described, although the tag1 mutant seeds accumulated less oil and seed maturation was delayed for nearly 1 week, no significant morphological changes were observed compared with the wild-type plants (Katavic et al., 1995). Routaboul et al. (1999) reported that seed germination was also delayed in the tag1 mutants especially for the tag1-2. We similarly observed that germination was slower in the mutants, although the tag1-1 mutant was only delayed for about 6 h compared with the wild-type Col (data not shown). It is known that the plant hormone ABA can affect seed germination and that soluble sugar levels dramatically alter the response of Arabidopsis seeds to ABA (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000; Finkelstein and Gibson, 2002). Therefore, we sowed the mutant and wild-type seeds on media containing a range of concentrations of ABA or Glc. To minimize the possible environmental effects such as those of plant growth and seed storage conditions, mutants were raised side by side with the wild types, and the same age seeds were used in this study. Seeds from different batches were used in replicated experiments.

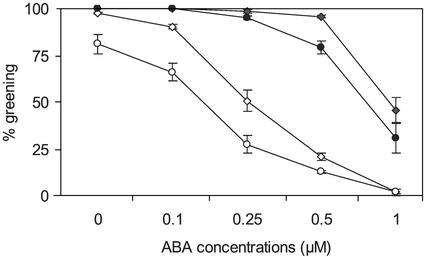

Figure 1 shows that the mutants and the wild types have similar responses to ABA in germination (radicle emergence) because mutants and wild types were not inhibited by up to 1 μm ABA (Fig. 1A). However, ABA has a stronger effect on the mutants in inhibiting cotyledon emergence and seedling growth compared with wild types (Fig. 1B). When Glc was added to the medium, cotyledon emergence and root growth were improved; however, further seedling development was compromised in the mutants. For mutants and wild types, seedling growth was arrested on medium containing 1 μm ABA in the presence of 60 mm Glc. Mutants appeared to be more severely affected, as most tag1 seedlings failed to turn green on media containing as low as 0.25 μm ABA, whereas wild-type seedlings were only slightly affected (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Seed germination and seedling development of wild types and the tag1 mutants in response to ABA. About 100 seeds were plated on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog media containing different concentrations (micromoles) of ABA, and were incubated at 23°C after cold treatment at 4°C for 3 d. Germination determined by radicle emergence (A) and seedling growth indicated by cotyledon emergence and axis elongation (B) were scored at 7 d postimbibition. Data represent mean values of three independent experiments using seeds harvested from different batches of plants. Error bars indicate se.

Figure 2.

The response of seedling development of the tag1 mutants to ABA in the presence of Glc. Growth conditions are the same as that in Figure 1. Values are from three independent experiments and are expressed as the percentage of seedlings based on germinated seeds.

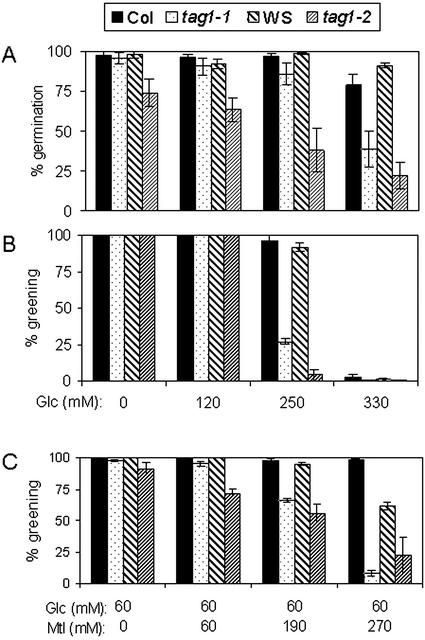

The germination potential of the mutants was not improved by added sugar (Fig. 3A; Routaboul et al., 1999). On the contrary, germination was inhibited by supplying elevated concentrations of sugar, especially for the tag1-2 mutant (Fig. 3A). For both mutants, the severity of inhibition of germination increased with increasing concentration of Glc (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Seed germination and seedling development of wild type and the tag1 mutants in response to Glc. About 100 mutant and 100 wild-type seeds were grown on media supplemented with different concentrations (millimoles) of Glc in the absence (A and B) or presence of different concentrations (millimoles) of mannitol (C). Germination and greening were scored 7 d postimbibition, and the mean values of three experiments are presented. The greening rate was expressed as the percentage of greening seedlings based on germinated seeds. Error bars indicate se.

High concentrations of exogenous sugars are known to inhibit early seedling development of Arabidopsis. Wild-type seeds plated on media containing high concentrations of Suc or Glc germinate but fail to develop true leaves and have purple/white cotyledons that show little expansion (Jang and Sheen, 1994; Gibson, 2000; Laby et al., 2000). We similarly observed that wild-type seedling development was inhibited by 330 mm Glc (Fig. 3B). It is interesting that the tag1 mutants are more sensitive to Glc-induced seedling developmental arrest. In the presence of 250 mm Glc, over 70% of the mutant seedlings failed to develop green expanded cotyledons and true leaves, whereas wild-type seedlings were only slightly affected (Fig. 3B).

To determine whether the increased sensitivity of the tag1 mutants to Glc and ABA was caused by the osmotic strength of the medium, seedling development of the tag1 mutants was examined by growing them on media supplemented with the same concentrations of mannitol. Germination of the mutants was found to be more severely inhibited by high concentrations of mannitol (data not shown), so it appears that osmotic stress may be the important factor in reducing germination potential rather than Glc per se. However, high concentrations of mannitol did not affect greening of the seedlings in mutants or wild types, indicating that osmotic stress alone could not induce the seedling development defect that was induced by high Glc. It is interesting that increasing the osmotic strength of the media caused by mannitol increased the seedling's sensitivity to Glc because in such conditions, 60 mm Glc can induce seedling developmental arrest that was induced by high (330 mm) Glc alone, and the mutants also showed increased sensitivity in this aspect compared with the wild types (Fig. 3C).

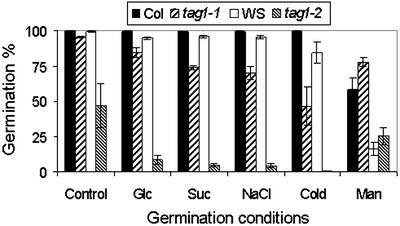

The increased sensitivity of the mutants to ABA and osmotic stress suggested that the mutation may have an impact on tolerance to other environmental stress because there is evidence of crosstalk between the signaling pathways involved (Smeekens, 2000). As expected, germination of the mutants was also more sensitive to salt and cold (Fig. 4). It is interesting to mote that the mutants were less sensitive to Man in inhibiting germination (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Seed germination of wild types and the tag1 mutants in response to different stress conditions. Germination was tested by growing seeds on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog media at 4°C (cold) or 23°C (control) supplemented with 250 mm Glc, 250 mm Suc, 100 mm NaCl, or 2.5 mm Man. Data represent mean values from three replicated experiments.

Glc Metabolism in the tag1 Mutants

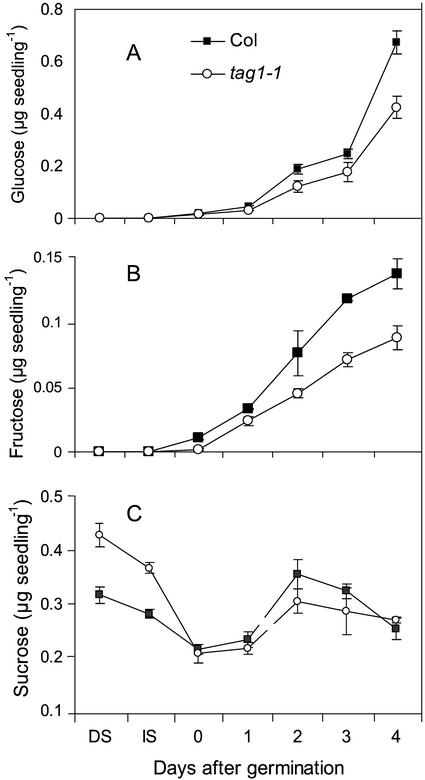

It is clear that the mutants are more sensitive to Glc during seedling development, therefore it was important to investigate whether the DGAT1 deficiency affected sugar metabolism. Both tag1 mutants contain significantly higher amounts of Suc in dry seeds than their corresponding wild types (only data of the tag1-1 mutant and Col wild-type are shown in Fig. 5), but Glc and Fru were almost undetectable. During imbibition the amount of Suc in the seeds of mutants and wild types decreased to a similar value at germination. Following germination, the Suc level in mutant and wild-type seedlings increased during the first 2 d and then decreased. It is interesting that the wild-type seedlings contained a slightly higher Suc level than did the mutant seedlings at 2d after germination (Fig. 5C). The amount of Glc and Fru increased with seedling growth, although the wild-type seedlings contained significantly more of these sugars at all stages after germination and especially d 3 and 4 (Fig. 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

Time courses of soluble sugar levels in wild types and the tag1-1 mutants after germination. Glc (A), Fru (B), and Suc (C) contents were measured in triplicate extracts of two replicated experiments in the following time points: dry seeds (DS), immediately after imbibition at 4°C for 3 d (IS), and 0 to 4 d after germination. Mean values and se are presented.

Because the sugar contents of the mutant seedlings were altered, we also determined the activities of a number of glycolytic enzymes in the tag1-1 mutant and wild-type (Col) seedlings at 2 d after germination. In addition, we measured the activity of UDP-Glc pyrophosphorylase, which catalyzes the conversion of UDP-Glc to Glc-1-P. The results of these experiments are summarized in Table I. The activities of the hexokinases (glucokinase and fructokinase) were 3- to 4-fold higher than that of the wild type. There was little significant variation in the activities of the other enzymes measured. Similar results were obtained for 5-d-old seedlings in which the hexokinase activity was still 1.5 to 2 times higher in the tag1-1 mutants. The tag1-2 mutants also showed significantly increased hexokinase activity compared with the wild type (WS; data not shown). For seedlings grown in the presence of 120 mm Glc, the hexokinase activity was increased by about 2-fold in tag1-1 and Col seedlings, thus the difference in activity was preserved. The sugar content of 2-d-old seedlings grown on 120 mm Glc was found to be elevated about 4- to 5-fold and was very similar in mutant and wild types (data not shown).

Table I.

Activities of different enzymes involved in Glc metabolism in the Col wild-type and in the tag1-1 mutant seedlings

| Enzyme | Enzyme Activity

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Col (wild type) | tag1-1 | |

| nmol min−1 μg−1 protein | ||

| Glucokinase | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 33.6 ± 1.0 |

| Fructokinase | 11.4 ± 1.5 | 33.4 ± 1.4 |

| Phosphoglucose isomerase | 426.3 ± 18.8 | 535.9 ± 13.8 |

| ATP-dependent phosphofructokinase | 11.9 ± 1.2 | 13.9 ± 1.9 |

| PPi-dependent phosphofructokinase | 34.5 ± 1.7 | 31.5 ± 6.8 |

| Aldolase | 219.6 ± 8.3 | 211.5 ± 6.6 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-P dehydrogenase | 857.7 ± 22.6 | 979.1 ± 88.9 |

| Phosphoglycerate kinase | 1,203.5 ± 91.9 | 1,469.9 ± 206.2 |

| Enolase | 149.5 ± 6.4 | 181.4 ± 9.4 |

| Pyruvate kinase | 1,312.2 ± 75.8 | 1,258.9 ± 53.6 |

| UDP-Glc pyrophosphorylase | 436.0 ± 63.6 | 528.7 ± 56.2 |

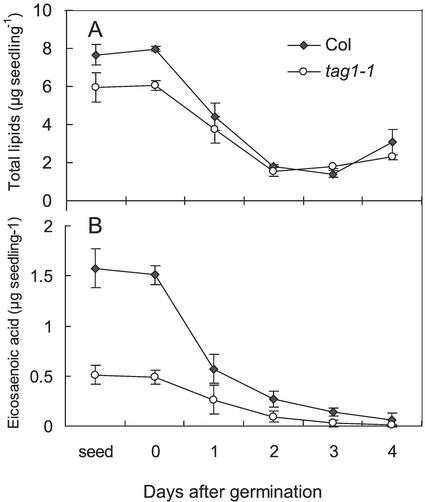

Lipid Breakdown

The total lipid and fatty acid contents of seeds were assayed during seed germination and seedling growth on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium. The TAG content of the tag1 seeds is reduced to 75% (w/w; tag1-1) or 55% (w/w; tag1-2) of the wild-type levels (Katavic et al., 1995; Routaboul et al., 1999). The rate of lipid degradation was similar in the tag1-1 mutant and wild type, and at 2 d after germination, both sets of seedlings contained similar amounts of lipid. From d 3, the amount of total lipid increased as the seedlings grew (Fig. 6A). The amount of storage TAG was estimated from the amount of eicosaenoic acid (20:1), which is specific for TAG (Lemieux et al., 1990), although the mutant contains only 30% (w/w) as much eicosaenoic acid as the wild type (Katavic et al., 1995). The storage TAG was more rapidly depleted to zero in the mutant compared with wild type (Fig. 6B), although when compared as a proportion of 20:1 at the start, the difference is not great.

Figure 6.

Lipid content of Col wild type and the tag1-1 seeds and seedlings during germination and early postgerminative growth. Total fatty acid content (A) and eicosaenoic acid (B; 20:1) in 20 seeds or seedlings were determined on two batches of triplicate extracts, and values of mean ± se are presented.

It was shown previously that DGAT1 is expressed in seedlings at similar levels to other tissues (Zou et al., 1999), and we have found that DGAT1 mRNA is present at similar levels in seedlings from 1 to 10 d after germination (data not shown). It has previously been suggested that DGAT might play a role during mobilization of TAG by catalyzing the reverse reaction or by regenerating TAG from excess DAG and acyl-coenzyme A (CoA) generated by the action of lipase and acyl-CoA synthetase on TAG (Feussner et al., 2001). This could act to keep the supply of acyl-CoA in check with the requirement by seedling growth. However, the rate of lipid degradation in the mutant was little different to that of wild type.

DISCUSSION

Storage TAG is essential for successful seedling establishment in Arabidopsis (Hayashi et al., 1998; Eastmond et al., 2000). DGAT catalyzes the final step of the TAG biosynthesis pathway and presumably has the highest activity during seed development, although postembryonic activity of DGAT has been demonstrated or implicated by previous studies (Wilson and Kwanyuen, 1986; Hobbs et al., 1999; Zou et al., 1999). In an attempt to understand the effect of loss of DGAT1 activity on postembryonic development, we analyzed the previously isolated tag1 mutants in Arabidopsis (Katavic et al., 1995; Routaboul et al., 1999). The striking effect of the tag1 mutations in WS and Col Arabidopsis backgrounds is the significantly increased sensitivity to ABA, sugars, and osmotic stress. Germination rate and seedling establishment were inhibited by lower concentrations of sugars or mannitol than were required to cause the same effect in wild type. It is interesting that although a significantly higher level of sugar was observed in the mutant seeds, it did not confer increased tolerance to osmotic stress during germination. On the contrary, germination of the mutants was more severely inhibited by elevated sugar or osmotic strength of the medium (Fig. 3). That the tag1 mutants were slightly less sensitive to Man in inhibiting germination may be explained by the fact that sugar level is higher in the mutant seeds than wild types in dry seeds and during imbibition (Fig. 5). This is in agreement with a previous report that low concentrations of exogenous sugars may relieve the effect of Man (Pego et al., 1999).

Although radicle emergence in the mutants showed a similar response to ABA compared with that of the wild types, cotyledon emergence and seedling growth of the mutants were more severely inhibited by ABA in the tag1 mutants (Fig. 1). After germination, sugar levels in the tag1 mutants were found to be slightly lower than that of the wild types, possibly caused by the lower TAG content in the mutant seeds (Fig. 5). This may explain the increased sensitivity of the tag1 mutants to ABA because sugars have been shown to have an antagonistic effect on ABA response during germination (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000). It has been suggested that ABA inhibits germination and seedling growth by limiting the availability of energy and nutrients (Garciarrubio et al., 1997). Recent studies also show that although the glyoxylate cycle is not essential for germination, postgerminative growth is inhibited without an exogenous carbon supply (Hayashi et al., 1998; Eastmond et al., 2000). However, the growth of tag1 mutants was more severely inhibited than wild type by ABA or osmoticum in the presence of low concentrations of Glc, as were seedlings grown on media supplemented with high concentrations of sugars but no ABA (Fig. 2). In the presence of exogenous sugar, TAG breakdown is slowed and seedlings use the supplied sugar to support growth (Eastmond et al., 2000). Therefore, the effect of reduced TAG in the tag1 mutant seeds would not become apparent in the presence of added sugar. The sugar content of wild-type and mutant seedlings grown on the Glc-containing media was greatly increased, masking the relatively small difference found on media without added sugar. Therefore, the difference of sugar levels between the mutant and wild type after germination did not explain the increased sugar sensitivity in the tag1 mutants.

The sugar-sensing mechanisms in plants is not yet well understood, and the existing models are largely derived from the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) system in which a number of transcription factors and their regulation are already known (Smeekens and Rook, 1997; Gancedo, 1998; Gibson and Graham, 1999; Gibson, 2000; Koch et al., 2000). By overexpressing the hexokinases in transgenic plants, Jang et al. (1997) demonstrated that Arabidopsis seedlings displayed increased sensitivity to sugars and proposed that hexokinases may serve as sugar sensors in higher plants. However, the role of hexokinases in sugar sensing remains controversial (Halford et al., 1999). We also found that increased sugar sensitivity of the tag1 mutants coincided with significantly higher hexokinase activity in the tag1 mutants compared with that of the wild types. This difference was preserved in 5-d-old seedlings when seed storage TAG is almost depleted and photosynthesis is fully in operation.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that DGAT1 deficiency alters carbohydrate metabolism in the tag1 mutants. The seeds accumulate significantly more Suc, and the activity of hexokinase is significantly increased in the mutant seedlings compared with the wild types. The altered carbohydrate metabolism in the tag1 mutants may have, in turn, resulted in the increased sensitivity of seedlings to ABA, sugars, and osmotic stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

For germination and seedling development tests, Arabidopsis ecotypes Col and WS and the tag1 (AS11 and ABX45) mutant seeds were surface sterilized with 30% (w/v) household bleach for 7 min, rinsed with sterile water at least three times, and plated on half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962). To ensure a homogenous germination, plated seeds were kept at 4°C for 3 d and then transferred to a controlled environment cabinet at 23°C for germination under a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle.

All determinations of germination and seedling development frequencies were made at d 7 after imbibition unless stated otherwise. In the absence of a universal definition, germination was defined as the emergence of 1 mm or more of the radicle from the seed coat.

Sugar Assays

Sugars were extracted by heating triplicate samples of 10 seeds or seedlings in 500 μL of 80% (v/v) ethanol in a 1.5-mL polypropylene tube at 70°C for 90 min (Focks and Benning, 1998). The ethanol was transferred to a separate tube and the seedlings washed twice more with 80% (v/v) ethanol. The ethanol was removed under a stream of N2 gas and once the volume had reduced to about 300 μL, the remaining aqueous solvent was removed by lyophilization. The residue was dissolved in 100 μL of water. To quantify the sugars, 20-μL aliquots were added to 980 μL of buffer containing 50 mm HEPES buffer (pH 7.0), 5 mm MgCl2, 2 mm NADP+, 1 mm ATP, and 2 units of mL−1 Glc-6-P dehydrogenase. To determine Glc, Fru, and Suc, 5 units of hexokinase, 1 unit of phosphoglucomutase, and 5 μL of a 100 μg μL−1 invertase were added in succession. Duplicated assays were performed, and the production of NADPH was followed using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto) at 340 nm.

Enzyme Assays

To determine the activity of different enzymes during seedling development, approximately 300 mg of seedlings grown on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog medium was harvested 2 or 5 d after germination and were transferred into 300 μL of chilled (4°C) extraction buffer containing 20 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.0, 10 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mm dithiothreitol, and small amount of polyvinylpolypyrrolidone. The subsequent manipulations were at 4°C. Seedlings were homogenized in 1.5-mL polypropylene test tubes using a motor-driving motor. Following centrifugation at 16,000g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube and kept on ice. The protein content of the supernatant was determined using the Bradford method.

Enzyme activity assays were performed immediately after the above extraction. The following enzymes were assayed as previously described (Focks and Benning, 1998): glucokinase (EC 2.7.1.1), fructokinase (EC 2.7.1.4), phosphoglucoisomerase (EC 5.3.1.9), ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase (EC 2.7.1.11), pyrophosphate-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase (EC 2.7.1.90), Fru-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase (EC 4.1.2.13), glyceraldehyde 3-P dehydrogenase (EC 1.2.1.12), phosphoglycerate kinase (EC 2.7.2.3), enolase (EC 4.2.1.11), pyruvate kinase (EC 2.7.1.40), and UDP-Glc-pyrophosphorylase (EC 2.7.7.9). Different amounts of extract were used, depending on the enzyme activity, to give a linear reaction for 5 to 10 min. All assays were performed in a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu) at 340 nm.

Lipid Analysis

The fatty acid content of germinating seeds and seedlings was determined according to the method described previously (Browse et al., 1986) using triheptadecanoin as an internal standard. Fatty acid methyl esters were analyzed with an Autosampler Gas Chromatograph (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) using a 50-m capillary column using isothermal separation at 190°C.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Loic Lepiniec and Ljerka Kunst for supplying the tag1-1 (AS11) and tag1-2 (ABX45) mutant seeds. We also thank Drs. Des Bradley and Fred Rook for helpful discussions, and Dr. Alison Smith for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by The Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council through the Competitive Strategic Grant to the John Innes Centre and through a research grant under the “Genome Analysis of Agriculturally Important Traits” initiative.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.006122.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bewley JD, Black M. Seeds: Physiology of Development and Germination. 2nd ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbeer JW. Seed Dormancy and Germination. Glasgow: Blackie; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Browse J, McCourt PJ, Somerville CR. Fatty acid composition of leaf lipids determined after combined digestion and fatty acid methyl ester formation from fresh tissue. Anal Biochem. 1986;152:141–145. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlqvist A, Stahl U, Lenman M, Banas A, Lee M, Sandager L, Ronne H, Stymne S. Phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase: an enzyme that catalyzes the acyl-CoA-independent formation of triacylglycerol in yeast and plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6487–6492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120067297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond PJ, Germain V, Lange PR, Bryce JH, Smith SM, Graham IA. Postgerminative growth and lipid catabolism in oilseeds lacking the glyoxylate cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5669–5674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feussner I, Kuhn H, Wasternack C. Lipoxygenase-dependent degradation of storage lipids. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:268–273. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01950-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein RR, Gibson SI. ABA and sugar interactions regulating development: cross-talk or voices in a crowd? Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2002;5:26–32. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(01)00225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein RR, Lynch TJ. Abscisic acid inhibition of radicle emergence but not seedling growth is suppressed by sugars. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:1179–1186. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focks N, Benning C. wrinkled1: a novel, low-seed-oil mutant of Arabidopsis with a deficiency in the seed-specific regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:91–101. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancedo JM. Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:334–361. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.334-361.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garciarrubio A, Legaria JP, Covarrubias AA. Abscisic acid inhibits germination of mature Arabidopsis seeds by limiting the availability of energy and nutrients. Planta. 1997;203:182–187. doi: 10.1007/s004250050180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson SI. Plant sugar-response pathways: part of a complex regulatory web. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:1532–1539. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.4.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson SI, Graham IA. Another player joins the complex field of sugar-regulated gene expression in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4746–4748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurr MI. Triacylglycerol biosynthesis. In: Stumpf PK, editor. The Biochemistry of Plants. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 205–248. [Google Scholar]

- Halford NG, Purcell PC, Hardie DG. Is hexokinase really a sugar sensor in plants? Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi M, Toriyama K, Kondo M, Nishimura M. 2, 4-Dichlorophenoxybutyric acid-resistant mutants of Arabidopsis have defects in glyoxysomal fatty acid β-oxidation. Plant Cell. 1998;10:183–195. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs DH, Lu C, Hills MJ. Cloning of a cDNA encoding diacylglycerol acyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana and its functional expression. FEBS Lett. 1999;452:145–149. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00646-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth M, Kurup S, McKibbin R. Molecular and genetic mechanisms regulating the transition from embryo development to germination. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Jang JC, Leon P, Zhou L, Sheen J. Hexokinase as a sugar sensor in higher plants. Plant Cell. 1997;9:5–19. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang JC, Sheen J. Sugar sensing in higher plants. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1665–1679. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.11.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katavic V, Reed DW, Taylor DC, Giblin EM, Barton DL, Zou J, Mackenzie SL, Covello PS, Kunst L. Alteration of seed fatty acid composition by an ethyl methanesulfonate-induced mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana affecting diacylglycerol acyltransferase activity. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:399–409. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.1.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KE, Ying Z, Wu Y, Avigne WT. Multiple paths of sugar-sensing and a sugar/oxygen overlap for genes of sucrose and ethanol metabolism. J Exp Bot. 2000;51:417–427. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.suppl_1.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laby RJ, Kincaid MS, Kim D, Gibson SI. The Arabidopsis sugar-insensitive mutants sis4 and sis5 are defective in abscisic acid synthesis and response. Plant J. 2000;23:587–596. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardizabal KD, Mai JT, Wagner NW, Wyrick A, Voelker T, Hawkins DJ. DGAT2 is a new diacylglycerol acyltransferase gene family: purification, cloning, and expression in insect cells of two polypeptides from Mortierella ramanniana with diacylglycerol acyltransferase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38862–38869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux B, Miquel M, Somerville C, Browse J. Mutants of Arabidopsis with alterations in seed lipid fatty acid composition. Theor Appl Genet. 1990;80:234–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00224392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield SG, Briarty LG. Cotyledon cell development in Arabidopsis thaliana during reserve deposition. Can J Bot. 1991;70:151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Plant Physiol. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlrogge J, Browse J. Lipid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:957–970. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pego JV, Weisbeek PJ, Smeekens SC. Mannose inhibits Arabidopsis germination via a hexokinase-mediated step. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:1017–1023. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.3.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piffanelli P, Ross JH, Murphy DJ. Intra- and extracellular lipid composition and associated gene expression patterns during pollen development in Brassica napus. Plant J. 1997;11:549–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11030549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routaboul J, Benning C, Bechtold N, Caboche M, Lepiniec L. The TAG1 locus of Arabidopsis encodes for a diacylglycerol acyltransferase. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1999;37:831–840. doi: 10.1016/s0981-9428(99)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeekers S. Sugar-induced signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000;51:49–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeekens S, Rook F. Sugar-sensing and sugar-mediated signal transduction in plants. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:7–13. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RF, Kwanyuen P. Triacylglycerol synthesis and metabolism in germinating soybean cotyledons. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;877:231–237. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(90)90227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Wei Y, Jako C, Kumar A, Selvaraj G, Taylor DC. The Arabidopsis thaliana TAG1 mutant has a mutation in a diacylglycerol acyltransferase gene. Plant J. 1999;19:645–653. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]