Abstract

Imaging plays a crucial role in the staging of oral cancers. Imaging information is essential for determining tumour resectibility, post resection surgical reconstruction and radiation therapy planning. The aim of this paper is to highlight the natural history of oral cancer spread and how malignant infiltration can be accurately mapped. It focuses on buccal mucosa, hard palate, tongue and floor of mouth carcinoma.

Keywords: Buccal carcinoma, hard palate carcinoma, tongue carcinoma, floor of mouth carcinoma, retromolar trigone carcinoma

Introduction

The vast majority of oral cancers are squamous cell carcinomas (SCCa). They account for more than 90% of all oral malignant lesions. These lesions are thought to result from multiple genetic alterations that affect cell growth regulation. These alterations may be genetically determined or caused by prolonged exposure to environmental factors such as tobacco and alcohol [1]. Other malignancies that may arise in this area include lymphomas, sarcomas and minor salivary gland tumours.

Oral cavity cancers are classified into the following subsites [2]: (1) buccal mucosa; (2) upper alveolus and gingival; (3) lower alveolus and gingival; (4) hard palate; (5) tongue; and (6) floor of mouth. The T1 to T3 classifications are based purely on the greatest dimension (T1 tumours are less than 2 cm; T2 tumours are more than 2 cm but less than 4 cm; and T3 tumours are more than 4 cm). T4a tumours involve bone, extrinsic muscles of the tongue, maxillary sinus, or skin. T4b tumours involve the masticator space, pterygoid plates, skull base or encase the carotid sheath. The role of imaging, therefore, is to determine whether tumours involve the anatomic structures specified in the UICC staging manual [2].

Buccal mucosa

The buccal mucosa is the mucosa that lines the inner surface of the lips and cheeks. Buccal SCCa are usually low grade cancers and are most commonly found in the lateral walls of the buccal cavity. These lesions spread along the submucosal surface and may eventually involve skin (Fig. 1). Advanced lesions may erode the adjacent alveolar margin. A search for bone or skin involvement is important as infiltration of these structures constitutes T4a disease.

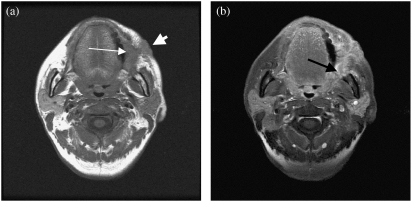

Figure 1.

(a) Axial T1-weighted MRI shows a left buccal mucosa carcinoma (thin arrow) with skin infiltration (thick arrow). (b) Axial contrast enhanced MRI shows tumour enhancement. Note tumour infiltration of the left buccal space (arrow).

The retromolar trigone, as the name suggests, is a small area posterior to the last molar. Retromolar trigone SCCa are therefore classified as buccal mucosa tumours. These tumours often show posterior spread with early involvement of the mandible (Fig. 2). The pterygomandibular raphe can be found beneath the mucosal surface of the retromolar trigone. This ligament (originates in the mandible and inserts into the pterygoid process) is the common insertion of the buccinator muscle, obicularis oris and the superior constrictor muscles. Tumour may extend superiorly along this raphe to erode the pterygoid process or the adjacent maxilla. Alternatively the tumour may extend into the adjacent buccal space or medially into the oropharynx and base of tongue [3].

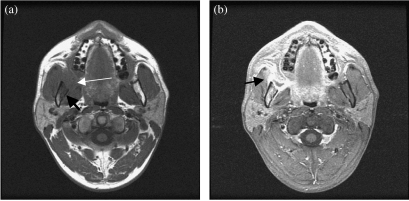

Figure 2.

(a) Axial T1-weighted MRI shows a right intermediate signal intensity retromolar trigone carcinoma (thin arrow). There is adjacent mandibular marrow involvement (thick arrow). (b) Axial contrast enhanced MRI shows tumour enhancement. Note the marrow enhancement and involvement of the right masseter muscle (arrow).

The choice of imaging modality is often determined by clinical findings. CT is adequate for early mucosal lesions and the staging for lymph node metastasis. As early cortical bone erosion is not well demonstrated on MRI, CT is indicated when bone involvement is clinically suspected.

Hard palate

Primary malignant tumours of the hard palate are rare. The hard palate has one of the highest concentrations of minor salivary glands in the upper aerodigestive tract. It is therefore not surprising that a large number of malignant neoplasms in this location are tumours of salivary gland origin (adenoid cystic carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma). As the mucosa of the hard palate is closely applied to the underlying bone, early osseous erosion is often encountered. It is therefore important to obtain coronal CT sections of the oral cavity for adequate staging of hard palate carcinoma.

Tongue

Nearly all tongue tumours occur on the lateral and undersurface (Fig. 3). Tumours tend to remain in the tongue but show well defined routes of infiltration in neglected cases. Anterior third tumours invade the floor of the mouth. Middle-third lesions invade the musculature of the tongue and subsequently floor of the mouth. Posterior-third lesions grow into the musculature of the tongue, the floor of the mouth, the anterior tonsillar pillar, tongue base, glossotonsillar sulcus and mandible.

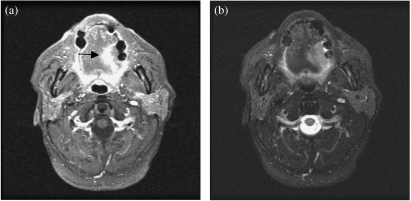

Figure 3.

(a) Axial contrast enhanced MRI shows an enhancing tumour on the lateral aspect of the left hemitongue (arrow). (b) Axial T2-weighted MRI shows a high signal intensity left tongue carcinoma. Fat saturated T2-weighted MRI is particularly useful in separating the lesion from normal tongue tissue.

It is known that the most important factor governing local recurrence is resection margin. Whereas 1 cm is generally considered adequate for most squamous cell carcinoma, for tongue cancer, the margins should be 1.5–2 cm. Tumours with deep margins are often difficult to assess during surgery. Hence, deep margins are frequently the site of positive or inadequate resection margins.

Up to 35% of patients have nodal metastasis on presentation; of these, 5% have bilateral lymph node involvement. It should be noted that in patients with clinically N0 neck, the overall occult metastasis rate is approximately 30%. Various clinical studies have been performed to correlate the depth of tumour invasion to the likelihood of cervical nodal metastasis [4, 5]. The first echelon nodes are the submandibular and subdigastric nodes. Submental node involvement is uncommon and these nodes are seen usually in patients with tumour at the tip of tongue.

Tongue carcinomas are sometimes difficult to see on CT. This is especially so when the tongue is obscured by dental streak artefacts. These artefacts are often serious enough to render the imaging study uninterpretable. MRI is better suited to the evaluation of tongue carcinoma. It provides valuable information both within and around the tongue.

Floor of the mouth

Floor of the mouth SCCa most commonly arise within 2 cm of the anterior midline. These carcinomas spread in a manner predictable by the anatomic location of the floor of the mouth. Superior spread may involve the ventral surface of the oral tongue; anterior and lateral spread may erode the mandible; inferior spread may infiltrate the genioglossus or mylohyoid muscles; while posterior spread often involves the tongue base (Fig. 4). The choice of imaging modality depends on clinical assessment. If the primary objective is to demonstrate or to rule out mandibular erosion, CT should be selected. However, the extent of soft tumour infiltration through the floor of the mouth or posteriorly into the tongue base is better achieved with MRI.

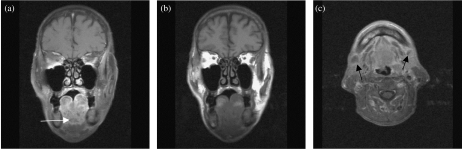

Figure 4.

(a) Coronal T1-weighted MRI shows an intermediate signal intensity mass with extensive involvement of the floor of the mouth. There is complete loss of the normal tissue planes. (b) Coronal contrast enhanced MRI shows heterogeneous enhancement in floor of mouth carcinoma. (c) Axial contrast enhanced MRI shows extensive floor of the mouth malignant infiltration. Note bilateral submandibular lymphadenopathy with central nodal necrosis (arrow).

References

- 1.Myers JN. Molecular pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. In: Myers EN, Syuen JY, editors. Cancer of Head and Neck. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1996. pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobin LH, Wittekind CH, eds. 6th edn. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2002. UICC TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherji SK, Fatterpekar G, Chong VFH. Malignancies of the oral cavity and oropharynx. In: Bragg DG, Rubin P, Hricak H, editors. Oncologic Imaging. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2002. pp. 202–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuen AP, Lam KY, Wei WI. A comparison of the prognostic significance of tumor diameter, length, width, thickness, area, volume, and clinicopathological features of oral tongue carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2000;180:139–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00433-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukukano H, Matsuura H, Hasegawa Y, Nakamura S. Depth of invasion as a predictive factor for cervical node metastasis in tongue carcinoma. Head Neck. 1997;19:205–10. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199705)19:3<205::aid-hed7>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]