Abstract

We investigated quantal release and ultrastructure in the neuromuscular junctions of synapsin II knockout (Syn II KO) mice. Synaptic responses were recorded focally from the diaphragm synapses during electrical stimulation of the phrenic nerve. We found that synapsin II affects transmitter release in a Ca2+-dependent manner. At reduced extracellular Ca2+ (0.5 mm), Syn II KO mice demonstrated a significant increase in evoked and spontaneous quantal release, while at the physiological Ca2+ concentration (2 mm), quantal release in Syn II KO synapses was unaffected. Protein kinase inhibitor H7 (100 μm) suppressed quantal release significantly stronger in Syn II KO synapses than in wild type (WT), indicating that Syn II KO synapses may compensate for the lack of synapsin II via a phosphorylation-dependent pathway. Electron microscopy analysis demonstrated that the lack of synapsin II results in an approximately 40% decrease in the density of synaptic vesicles in the reserve pool, while the number of vesicles docked to the presynaptic membrane remained unchanged. Synaptic depression in Syn II KO synapses was slightly increased, which is consistent with the depleted vesicle store in these synapses. At reduced Ca2+ frequency facilitation of synchronous release was significantly increased in Syn II KO, while facilitation of asynchronous release was unaffected. Thus, at the reduced Ca2+ concentration, synapsin II suppressed transmitter release and facilitation. These results demonstrate that synapsin II can regulate vesicle clustering, transmitter release, and facilitation.

Synapsins are phosphoproteins associated with presynaptic vesicles. Synapsins regulate vesicle clustering (Li et al. 1995; Hilfiker et al. 1998) and neurotransmitter release (Llinas et al. 1985, 1991; Hackett et al. 1990; Rosahl et al. 1995; Li et al. 1995; Hilfiker, 1998; Jovanovic et al. 2000, 2001; Cousin et al. 2003). However, the mechanisms by which synapsins act are not fully understood. In their dephosphorylated form, synapsins attach to synaptic vesicles and trigger actin polymerization (Greengard et al. 1993; Hilfinker, 1999 for review; Bloom et al. 2003), and phosphorylation of synapsins causes their dissociation from vesicles (Hosaka & Sudhof, 1998). Biochemical and optical studies suggest that dephosphorylated synapsins cage synaptic vesicles and prevent the release of neurotransmitter, while synapsin phosphorylation initiates the mobilization of vesicles into the releasable pool (Murthy, 2001 for review; Jovanovic et al. 2001; Cousin et al. 2003; Chi et al. 2003). A second role that has been proposed for synapsin is to regulate the kinetics of the release process (Hilfiker et al. 1998).

In mammals, synapsins are encoded by three different genes: synapsin I, II and III. These three forms of synapsin play different roles in vesicle trafficking and in the formation of synaptic terminals. Synapsin I deficiency disrupts the clustering of synaptic vesicles (Li et al. 1995). Intracellular injection of synapsin I into a squid (Llinas et al. 1985, 1991) or goldfish (Hackett et al. 1990) axon reduced neurotransmitter release. Mice deficient in synapsin I demonstrated decreased glutamate release from their synaptosomes (Li et al. 1995) and increased pair pulse facilitation in their hippocampal synapses (Rosahl et al. 1995).

Synapsin II is involved in the formation of synapses during nerve cell development (Han et al. 1991; Ferreira et al. 1994, 1995, 1998). As in the case of synapsin I, synapsin II is able to bind to both synaptic vesicles and actin filaments (Greengard et al. 1993 for review), and its association with synaptic vesicles is controlled by phosphorylation (Hosaka et al. 1999). These common properties of synapsin I and synapsin II suggest that synapsin II would have a role in the regulation of transmitter release and synaptic plasticity. Synapsin II-deficient mice demonstrated increased synaptic depression (Rosahl et al. 1995), and imaging experiments suggested that synapsin II might regulate the releasable pool of synaptic vesicles (Sugiyama et al. 2000).

The objective of the present study was to investigate the effect of synapsin II on the release of neurotransmitter, short-term synaptic plasticity, and vesicle stores employing a preparation where quantal release can be accurately monitored. The mouse neuromuscular junction is an excellent experimental preparation, which enables rigorous quantal analysis and exhibits prominent facilitation and depression. To understand the properties of vesicle clustering and quantal release, we combined quantal analysis of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) with an ultrastructural study of presynaptic terminals in synapsin II knockout (Syn II KO) mice.

Methods

Animals

All experiments conformed with the guidelines laid down by the Lehigh University Animal Welfare Committee. Mice homozygous for the Syn2tm1Sud targeted mutation, Syn II KO, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (strain B6129-Syn2tm1Sud). Strain B6129SF2/J (Jackson Laboratory) was used as a control (WT) to provide an approximate genetic match to the synapsin II knockout mice.

Dissection and treatments

Adult mice were killed by an overdose of ether, their diaphragms were rapidly removed, and the phrenic nerves were isolated. The preparation was pinned to Sylgard and superfused with a physiological solution containing (mm): 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 Hepes, and 11 glucose, pH adjusted to 7.4. The Mg2+ concentration was increased to 5 mm in order to minimize muscle twitching. In some experiments the Ca2+ concentration in the bath was reduced to 0.5 mm in order to reduce synaptic transmission, to enhance facilitation, and to prevent muscle contraction. Experiments with normal Ca2+ (2 mm) were performed on a cut muscle or after μ-connotoxin B treatment (2 μm for 20 min) to prevent muscle twitching. Kinase inhibitors (H7, 100 μm; KT5720, 10 μm) were applied to the bath solution 15 min prior to the recording. Since KT5720 is DMSO soluble, DMSO (0.5%) was also added to the bath solution in the control recordings.

Electrophysiology

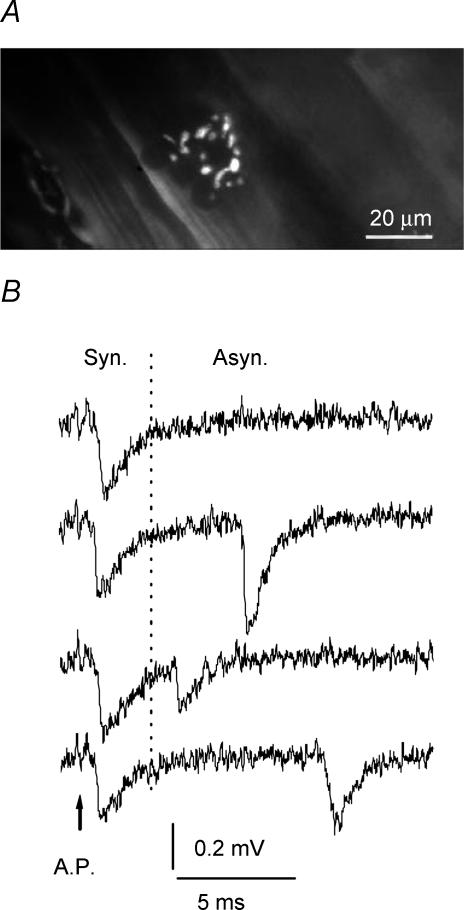

The phrenic nerve was stimulated via a suction electrode. EPSPs and miniature EPSPs (mEPSPs) were recorded focally using a 3–8 μm diameter tip macropatch electrode. The electrode was positioned over the ends of fine nerve branches visualized using a Nikon compound microscope equipped with DIC optics and a 60 × water-immersion objective. The tip of the electrode was manually bent to enable recordings under the objective with a 2 mm working distance. In several experiments the preparations were stained with fluorescent dye (2 min in 4 μm 4-Di-2-Asp, Molecular Probes), and the nerve endings were visualized (Fig. 1A). Recordings were acquired with 10 μs resolution using a Dagan 2400 A extracellular amplifier, A/D Board Digidata 1322 and Axoscope software (Axon Instruments).

Figure 1. Focal recordings from nerve endings.

A, a nerve endplate visualized with the fluorescent dye 4-Di-2-Asp. B, recordings of synchronous and asynchronous quanta (0.5 mm Ca2+ and 5 mm Mg2+ in the bath solution). The nerve action potential is marked with an arrow.

Quantal analysis

A temporal interval of 50 ms after the nerve action potential was analysed. Quantal latencies were measured from the negative peak of the action potential to the quantal peaks. According to their latencies, quanta were classified as synchronous or asynchronous (Fig. 1B). The synchronous release component decays within 3 ms, while asynchronous release component does not decay during the temporal interval analysed. Synchronous release was evaluated by the quantal content of EPSPs (m), and asynchronous release was evaluated by the frequency of mEPSPs.

Two methods were employed for the evaluation of the quantal content (m) in EPSPs: direct counts and amplitude analysis. The method of direct counts was used either to detect asynchronous quanta or to detect synchronous quanta at 0.5 mm Ca2+ and a stimulation frequency of 0.5 Hz. Under these conditions, synaptic transmission is low, and quantal counts are reliable. Quanta were counted as inflections or peaks of EPSP traces using in-house software (Bykhovskaia et al. 1996).

At higher stimulation frequencies or at physiological Ca2+ concentration, quantal content was calculated as the ratio between EPSP amplitude and quantal amplitude. At low Ca2+, we calculated the quantal amplitude from synchronous quanta recorded at 0.5 Hz stimulation frequency. To do this we collected all the unitary EPSPs with a single peak and with no inflections recorded at the stimulation frequency of 0.5 Hz, and we calculated their average amplitude. At normal Ca2+ concentrations, quantal amplitude was calculated as the average amplitude of asynchronous quanta, since under these conditions most of the EPSPs are multiquantal.

Electron microscopy

Muscle fibres innervated by nerve branches were dissected out and fixed in 2.4% glutaraldehyde−1.6% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m collidine buffer, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol and acetone, embedded in Embed-812 resin, and sectioned on a Sorvall MT-2 ultramicrotome. Ultrathin sections (70–90 nm) were mounted on Formvar-coated grids, stained with lead citrate and examined under a Phillips 420 transmission electron microscope.

The density of synaptic vesicles was quantified from electron micrographs at 11 000 ×. For the analysis, each micrograph was subdivided by squares of 0.04 μm2. Synaptic vesicles were counted only in the squares which included evenly distributed vesicles and excluded organelles. Vesicles were considered ‘docked’ if they were within 20 nm distance of the presynaptic membrane. To evaluate the pool of docked vesicles, we divided the number of docked vesicles by the length of the presynaptic membrane.

Statistical analysis

Unpaired t test (Origin 6.1) was used to evaluate statistical significance. Differences at the 5% level were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Synapsin II suppresses transmitter release at the reduced Ca2+ but not at physiological Ca2+ concentrations

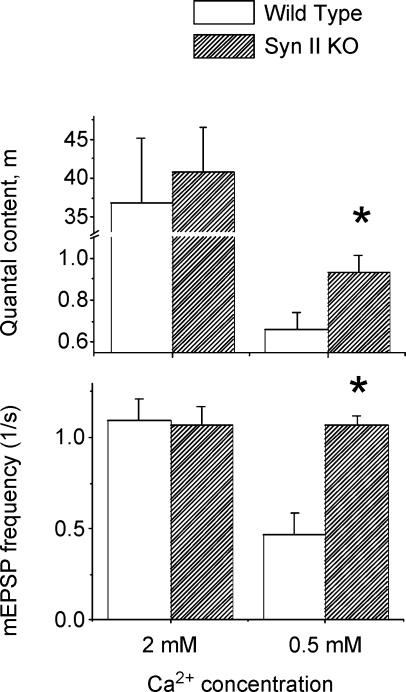

First, we investigated how synapsin II affects quantal release. We found that at physiological Ca2+ concentration evoked and spontaneous quantal release in Syn II KO mice is normal. However, at the reduced extracellular Ca2+ concentration (0.5 mm), both evoked and spontaneous release components were significantly increased in Syn II KO mice (Fig. 2). Spontaneous neurosecretion more than doubled in Syn II KO animals (1.07 ± 0.07 s−1 versus 0.46 ± 0.12 s−1), and action potential-evoked neurosecretion was increased by approximately 50% (0.93 ± 0.08 versus 0.66 ± 0.07). Thus, at reduced Ca2+ concentration, synapsin II suppresses transmitter release while at physiological Ca2+, presynaptic terminals are able to compensate for the synapsin II deficiency.

Figure 2. Quantal release is increased in Syn II KO mice at the reduced extracellular Ca2+ concentration (0.5 mm Ca2+) but not at physiological Ca2+ (2 mm).

Data collected from 21 recording sites for WT (17 animals) and 10 recording sites for Syn II KO (6 animals). The nerve was stimulated at the frequency 0.5 or 0.2 Hz; at least 100 sweeps were collected at each recording site. mEPSPs were recorded for 5 min in the absence of stimulation. * Significant (0.05) difference between WT and Syn II KO.

Synapsin II deficiency causes depletion of the vesicle store but does not affect vesicle docking

To understand how Syn II KO terminals compensate for the synapsin II deficiency, we carried out electron microscopy analysis of vesicle stores. We examined the presynaptic ultrastructure of WT and Syn II KO neuromuscular junctions.

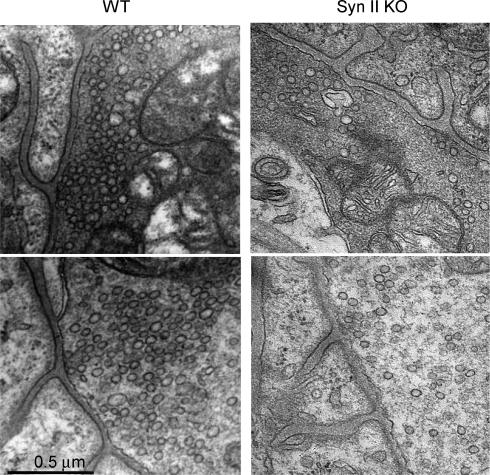

The mammalian diaphragm is formed by three types of muscle fibres (Gauthier & Padykula, 1966), which have morphologically distinct neuromuscular junctions (Padykula & Gauthier, 1970). After examining over a hundred neuromuscular junctions in four WT and in three Syn II KO animals, we identified two types of synapses: those densely packed with filamentous matrix and evenly distributed vesicles, and those with relatively sparse matrix and clustered vesicles. ‘Dense’ terminals are morphologically similar to innervations of ‘white’ fast twitch fibres, while ‘sparse’ nerve endings are likely to represent innervations of ‘red’ slow twitch fibres (Padykula & Gauthier, 1970). These two groups of terminals were analysed separately.

In both types of nerve endings, the density of vesicles was substantially reduced in Syn II KO animals (Figs 3 and 4). This effect was more pronounced in the ‘sparse’ synapses. In Syn II KO mice, ‘sparse’ synapses had a significantly lower density of vesicles (106.2 ± 8.2 μm−2) than ‘dense’ synapses (134 ± 7.5 μm−2), whereas in WT mice the density of vesicles was similar in the two types of nerve endings (199.7 ± 6.4 μm−2 in ‘dense’ synapses versus 197.9 ± 9.4 μm−2 in ‘sparse’ synapses, Fig. 4A). Apparently, the presence of dense filamentous matrix can partially compensate for the lack of synapsin II.

Figure 3. Vesicle density is reduced in Syn II KO mice.

Electron micrographs showing ‘dense’ (top) and ‘sparse’ (bottom) neuromuscular junctions of WT (left) and Syn II KO (right) mice. Scale bar is 0.5 μm.

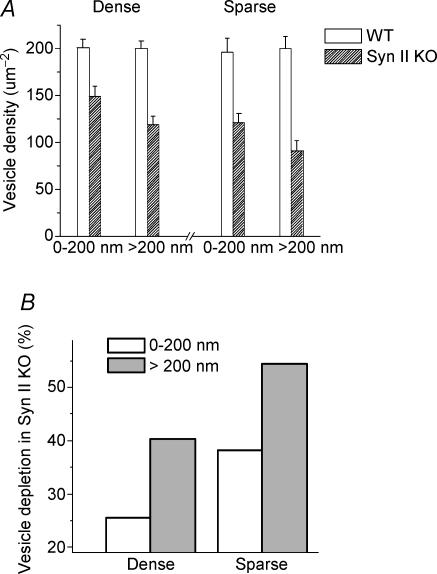

Figure 4. Quantitative analysis of vesicle density in ‘dense’ and ‘sparse’ terminals in the vicinity (within 200 nm distance) of the presynaptic membrane and in the interior area of the terminal (more than 200 nm away from the presynaptic membrane).

Data collected from 18 WT and 18 Syn II KO nerve terminals (12 dense and 6 sparse), from 2 WT and 2 Syn II KO animals. A, density of presynaptic vesicles. B, depletion of vesicles in Syn II KO mice compared with WT: (WT – Syn II KO)/WT.

Detailed spatial analysis revealed that disruption of synapsin II function has a higher impact on the density of vesicles inside the terminal (at a distance of more than 200 nm from the presynaptic membrane) than on the density of vesicles in the vicinity of the presynaptic membrane (within a 200 nm distance). Even in the vicinity of presynaptic membrane, the density of vesicles in Syn II KO terminals (139.7 ± 8.4 μm−2) was significantly lower than in WT terminals (198.7 ± 8.0 μm−2). The decrease in vesicle density was even stronger (109.6 ± 7.0 μm−2 in Syn II KO versus 199.6 ± 8.0 μm−2 in WT) for the vesicles situated at the distance of more than 200 nm from the presynaptic membrane. These results are summarized in Fig. 4B: in the membrane vicinity (0–200 nm), the density of vesicles in Syn II KO was reduced by 26% in ‘dense’ terminals and by 38% in ‘sparse’ terminals while inside the terminal (more than 200 nm from the membrane), the vesicle depletion in Syn II KO was 40% in ‘dense’ terminals and 54% in ‘sparse’ terminals.

Thus, the density of synaptic vesicles in Syn II KO animals was significantly reduced. This effect is less pronounced for the vesicles situated in the vicinity (within 200 nm) of the presynaptic membrane, and it is stronger for the vesicles in the interior area of the terminals.

Since vesicle depletion was less in the vicinity of the plasma membrane, and since transmitter release was not reduced in Syn II KO, we suggested that the pool of vesicles physically docked to the membrane might be unaffected by synapsin II. To test this hypothesis, we counted all of the vesicles physically docked to the presynaptic membrane (Fig. 5A). The pools of docked vesicles were found to be remarkably similar in Syn II KO and WT terminals (Fig. 5B).

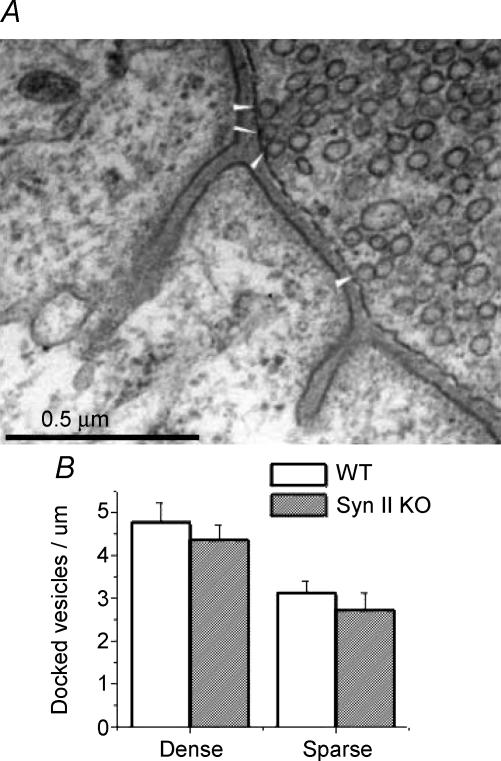

Figure 5. The pools of docked vesicles are similar in WT and Syn II KO synapses.

A, examples of vesicles docked to the presynaptic membrane (white arrowheads). B, the number of docked vesicles per μm of presynaptic membrane in ‘dense’ and ‘sparse’ terminals of WT and Syn II KO mice. Data collected from 7 ‘dense’ and 10 ‘sparse’ WT terminals, and 18 ‘dense’ and 8 sparse Syn II KO terminals.

Interestingly, the number of docked vesicles in ‘dense’ WT terminals was significantly higher than that in ‘sparse’ terminals, even though their reserve vesicle stores were not significantly different (Fig. 4A). For both types of terminals, Syn II KO demonstrated less than 10% reduction in the docked pool, and this reduction was not statistically significant. Thus, even though the lack of synapsin II results in substantial depletion of the vesicle store (Figs 3 and 4), docking (Fig. 5) and release (Fig. 2) are not reduced.

Synaptic depression is increased in Syn II KO synapses

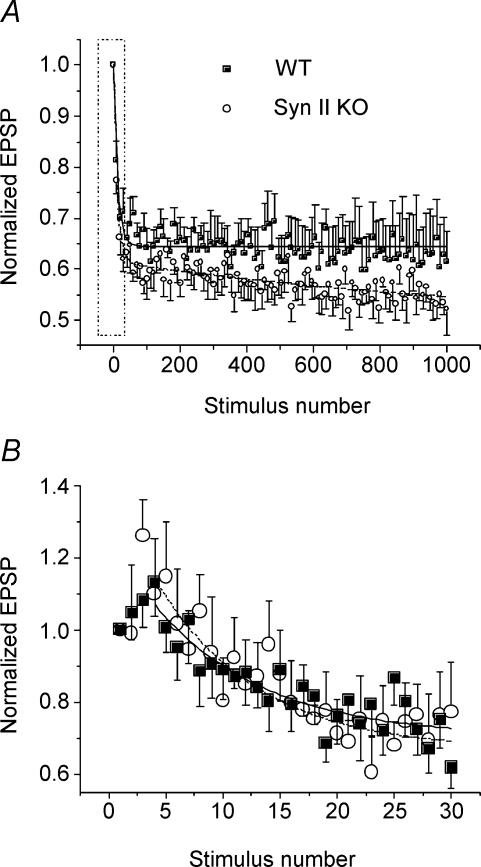

It could be expected that the depletion of the vesicle store would be manifested in increased synaptic depression. To test whether synapsin II affects depression, we recorded EPSPs evoked by 1000 stimuli delivered at the frequency of 15 Hz at physiological Ca2+ concentration.

At the mouse neuromuscular junction at normal Ca2+, short-term facilitation (four initial EPSPs) is followed by biphasic depression of transmitter release (Fig. 6). At the initial depression phase (50–100 stimuli) transmitter release decays exponentially; the second depression phase is well fitted by linear regression. Facilitation and the initial exponential phase of depression are similar in WT and Syn II KO synapses (Fig. 6B; exponential decay is 0.59 ± 0.31 s in WT versus 0.64 ± 0.23 s in Syn II KO). However, at the second phase transmitter release decays faster in Syn II KO (Fig. 6A): the slope of linear regression in Syn II KO (−3.61 ± 00.45 h−1) is significantly different from the regression slope in WT (−1.56 ± 00.45 h−1). Thus, the second phase of synaptic depression is significantly increased in Syn II KO terminals.

Figure 6. The second phase of depression is enhanced in Syn II KO.

A, biphasic depression during a tetanus. Each data point is the average from 10 successive EPSPs. Lines (continous, WT; dashed, Syn II KO) represent the fit by exponential (initial 100 stimuli) and linear (stimulus 100–1000) functions. The slope of the linear (second) depression phase is increased in Syn II KO. Boxed area is shown in detail in panel B. B, facilitation and the early (exponential) phase of depression are not affected in Syn II KO. Lines (continuous, WT; dotted, Syn II KO) represent the fit by exponential decay. Data collected from 10 WT and 6 Syn II KO preparations at physiological Ca2+.

The biphasic depression can be interpreted as a rapid release of the docked vesicles (initial phase) followed by reluctant release of vesicles supplied from the store. The similarity of the initial depression phases in Syn II KO and WT synapses is consistent with the observation that their docked vesicle pools are similar (Fig. 5). The cytomatrix vesicle store is depleted in Syn II KO, therefore it is logical to suggest that the vesicle supply from the cytomatrix store would be reduced in these synapses. Consistent with this suggestion, in Syn II KO transmitter release decays more rapidly at the second depression phase (Fig. 6A), indicating insufficient vesicle supply.

Thus, the combined electrophysiology and electron microscopy analysis establishes the role of synapsin II as a molecule which maintains the reserve vesicle store, so that a timely supply of vesicles to the presynaptic membrane can be provided. Under physiological conditions, however, synapses manage to compensate for the lack of synapsin II and the depleted vesicle store. Possibly, the probability of vesicle docking to the active zones is very high, so even a depleted vesicle store is sufficient to maintain normal docking under physiological conditions. Alternatively, Syn II KO synapses could develop a compensatory mechanism, for example, a faster recycling, in order to provide for normal docking in a depleted synapse.

Protein kinase inhibitor H7 differentially affects Syn II KO and WT synapses

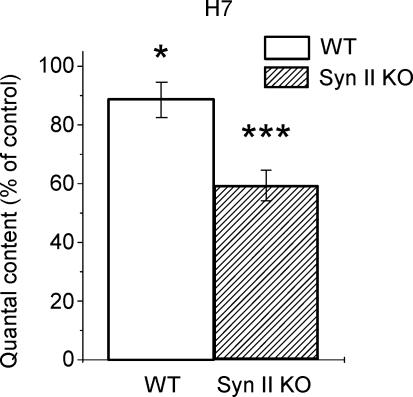

In an attempt to understand how Syn II KO synapses compensate for the depleted vesicle stores, we investigated the effect of protein kinase inhibitors on WT and Syn II KO synapses. Since synapsin is active in its dephosphorylated form, it could be expected that interfering with phosphorylation processes would increase vesicle ‘caging’ by synapsin II and thus inhibit transmitter release in WT but not in Syn II KO mice. The non-specific protein kinase inhibitor H7 was reported to inhibit evoked quantal release in the CNS (Oleskevich & Walmsley, 2000). We tested the effect of H7 (100 μm) on quantal release at the neuromuscular junction.

We found that H7 has an inhibitory effect on the evoked synaptic transmission in WT synapses (Fig. 7). Since synapsin could be one of the H7 targets, it could be expected that the effect of H7 on neurosecretion would be smaller in Syn II KO. Strikingly, the result was strictly opposite. After H7 application, quantal content was reduced to 0.88 ± 0.06 of control in WT synapses and to 0.59 ± 0.05 of control in Syn II synapses (Fig. 7). Thus, H7 reduced quantal content in Syn II KO synapses by 41%, significantly stronger than in WT (12%).

Figure 7. Protein kinase inhibitor H7 differentially affects quantal content in WT and Syn II KO synapses.

Data collected from 5 WT and 6 Syn II KO preparations. In each experiment, 100 EPSPs were recorded at 0.2 Hz stimulation frequency.

This effect was not reproduced by a specific protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor KT5720 (10 μm), which had no effect on transmitter release at either WT (quantal content 99.5 ± 5.9% of control) or Syn II KO (quantal content 96.2 ± 4.4% of control) synapses.

A stronger inhibitory effect of H7 on Syn II KO synapses indicates that H7 might interfere with compensatory mechanisms which allow Syn II KO synapses to maintain normal docking at the depleted terminal. Thus, our data support the hypothesis that Syn II KO synapses develop a compensatory phosphorylation-dependent mechanism, which enables the presynaptic terminal to maintain normal docking with a reduced vesicle store.

Synapsin II suppresses frequency facilitation at reduced Ca2+

Synapsin II suppressed transmitter release at the reduced Ca2+ concentration (0.5 mm, Fig. 1) but not at physiological Ca2+. Since at reduced Ca2+ concentration transmitter release is substantially decreased, it is possible that the effect of synapsin II is pronounced only when the release rate is low. To test this possibility, we enhanced the transmitter release at the reduced Ca2+ concentration by repetitive stimulation and investigated how synapsin II affects frequency facilitation.

We stimulated the nerve repetitively at the frequencies of 0.5, 4 and 15 Hz; higher stimulation frequencies sometimes elicited depression of transmitter release. When the nerve was stimulated repetitively, quantal release increased during the initial 5–10 pulses and then remained at a steady plateau level. The plateau facilitation was calculated as:

where m is quantal content at the stimulation frequency tested and m0.5Hz is quantal content in the absence of facilitation (at 0.5 Hz stimulation frequency).

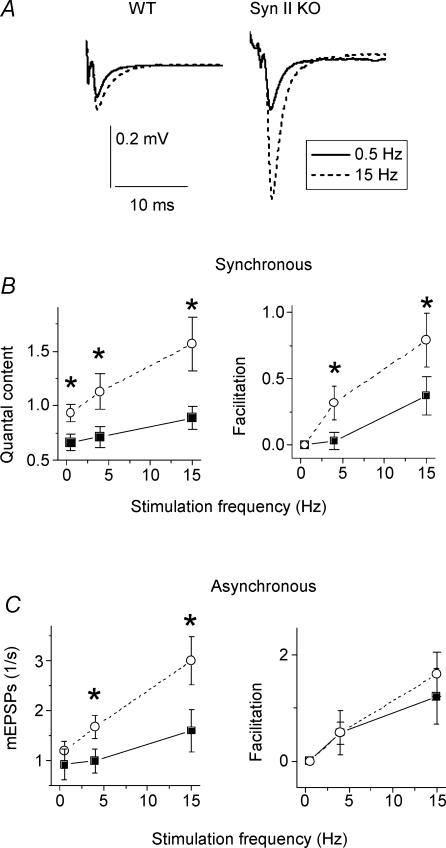

When the nerve was stimulated at 15 Hz, quantal content was almost two times higher in Syn II KO mice than in WT (1.57 ± 0.25 versus 0.89 ± 0.10; Fig. 8A). Correspondingly, facilitation in Syn II KO animals was significantly higher than in WT (Fig. 8B). This increase in facilitation in Syn II KO animals was clearly manifested as early as during 4 Hz stimulation frequency. When the nerve of WT animals was stimulated at 4 Hz, facilitation was observed only in some terminals, and the average facilitation was weak and not statistically significant (0.03 ± 0.06). In contrast, Syn II KO mice demonstrated consistent and statistically significant facilitation (0.37 ± 0.14) at the stimulation frequency of 4 Hz (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8. Frequency facilitation is increased in Syn II KO mice.

Continuous line, WT; dashed line, Syn II KO. A, average EPSPs recorded in a single experiment at the stimulation frequencies of 0.5 Hz (1000 sweeps) and 15 Hz (200 sweeps). B and C, frequency facilitation of synchronous (B) and asynchronous (C) release. Each data point represents the average of 16 experiments (14 animals) for WT and 9 experiments (6 animals) for Syn II KO. In each experiment, 1000 sweeps at 0.5 Hz, 200 sweeps at 4 Hz, and 200 sweeps at 15 Hz were recorded. * Statistically significant (at 5% level) difference between WT and Syn II KO synapses. ▪, WT; ○, Syn II KO.

Interestingly, facilitation of asynchronous release in Syn II KO mice did not differ from the control (Fig. 8C). Even though asynchronous release itself at stimulation frequencies of 4 and 15 Hz was significantly higher in Syn II KO (Fig. 8C), the difference between Syn II KO and WT was proportional across all the stimulation frequencies tested. Therefore, facilitation of asynchronous release was similar in Syn II KO and WT. Thus, lack of synapsin II affects facilitation of synchronous and asynchronous release differently, suggesting that facilitation of synchronous and asynchronous release might involve different mechanisms.

These results suggest another role of synapsin II in regulating the release process and facilitation of evoked release. This effect was manifested only at reduced Ca2+ concentration.

Discussion

We found that synapsin II maintains the store of synaptic vesicles. Animals lacking synapsin II have a depleted vesicle store; however, docking and release in Syn II KO synapses are normal. Since the protein kinase inhibitor H7 substantially suppressed release in Syn II KO synapses, we hypothesize that Syn II KO synapses compensate for the depleted store via phosphorylation-dependent mechanisms.

At reduced Ca2+ concentration, quantal release and frequency facilitation are significantly increased in Syn II KO synapses. This finding implies that synapsin II controls the release process and its enhancement by repetitive stimulation.

Synapsin II deficiency results in a depleted vesicle store but does not reduce docking and release

Our results indicate that synapsin II maintains the store of intra-terminal vesicles. Indeed, vesicle store in Syn II KO synapses is significantly depleted (Figs 3 and 4). This result is consistent with the proposed role of synapsins as regulators of the reserve pool of synaptic vesicles (Hilfiker et al. 1999 for review). It has already been demonstrated at the ultrastructure level that vesicle clustering in the reserve store is impaired in synapsin I-deficient mice (Li et al. 1995). It has also been shown that disrupting synapsin function in lamprey (Pieribone et al. 1995) and squid (Hilfiker et al. 1998) axon terminals results in dramatic impairment of vesicle clustering. In contrast, synapsin III had no effect on the vesicle density (Feng et al. 2002). Our study demonstrated that vesicle density is drastically reduced in synapsin II-deficient mice, thus establishing synapsin II as a necessary component for maintaining the reserve vesicle store.

Synapsin II affects vesicle density in the interior area of the terminal more strongly than in the vicinity of the presynaptic membrane (Fig. 4). This result is in agreement with similar findings made for synapsin I (Li et al. 1995), as well as lamprey (Pieribone et al. 1995) and squid (Hilfiker et al. 1998) synapsins. Furthermore, the pool of docked vesicles remains unaffected by synapsin II (Fig. 5). In agreement with this last finding, at physiological conditions Syn II KO synapses demonstrate normal transmitter release (Fig. 2).

Continuous stimulation, however, results in a stronger decay of transmitter release in Syn II KO synapses (Fig. 6), suggesting that the reserve vesicle store is required to sustain the release of transmitter in response to high levels of neuronal activity. A similar observation has been made at the hippocampal synapse (Rosahl et al. 1995). It should be noted, however, that at the neuromuscular junction the effect of synapsin II on synaptic depression, although statistically significant, was very small. Indeed, normalized transmitter release at the end of the tetanus (Fig. 6) was not significantly different in Syn II KO and WT synapses. A stronger effect could be expected based on the difference in ultrastructure. It appears that at the neuromuscular junction only a fraction of the vesicle store is sufficient to maintain continuous synaptic transmission, possibly, because of rapid vesicle recycling (Richards et al. 2000; Rizzoli & Betz, 2004).

Neurosecretion in Syn II KO synapses is strongly reduced by the protein kinase inhibitor H7 (Fig. 7). Quantitatively, the inhibitory effect of H7 on Syn II KO synapses (approximately 40%) matches the depletion of the vesicle store in Syn II KO synapses. These results suggest an H7-sensitive mechanism, which accelerates the refilling of the releasable pool and thus compensates for the vesicle depletion in Syn II KO terminals. Since it has been demonstrated (Gillis et al. 1996; Stevens & Sullivan, 1998; Smith et al. 1998) that the releasable pool of vesicles is regulated by protein kinase C (PKC), it is possible that H7 acts via a PKC pathway. We hypothesize that H7 interferes with the processes of fast vesicle recycling, and thus neurosecretion in H7-treated synapses becomes more dependent on the reserve vesicle store. Alternatively, it is possible that H7 interferes with vesicle mobilization from the reserve store, and thus docking significantly diminishes in the depleted Syn II KO synapses after H7 treatment. Further experimentation is needed to discriminate between these possibilities.

Synapsin II suppresses quantal release and frequency facilitation at the reduced Ca2+ concentration

An important novel result of our study is that at the reduced (0.5 mm) extracellular Ca2+ concentration, synapsin II suppresses quantal release and facilitation. It has been shown by Rosahl et al. (1995) that paired-pulse facilitation is increased in synapsin I-deficient mice. The present study demonstrated that frequency facilitation is regulated by synapsin II.

The question remains whether synapsin II acts to suppress release and facilitation by ‘caging’ vesicles in the reserve store or by affecting the downstream stage of the release process. Hilfiker et al. (1998) demonstrated that synapsin domain E directly regulates the kinetics of neurotransmitter release. Since synapsin II did not affect the pool of docked vesicles (Fig. 5), it could be suggested that it directly affects downstream exocytosis steps and thus regulates release and facilitation at reduced Ca2+.

The regulation of facilitation by synapsins points to facilitation mechanisms that are not yet understood. Facilitation is traditionally explained by accumulation of residual Ca2+ at the active zones (Zucker & Regehr, 2002 for review). Thus, it could be suggested that synapsin imposes a limit on the processes regulated by residual Ca2+. This explanation, however, does not agree with the observation that only facilitation of synchronous release is suppressed by synapsin II. Facilitation of asynchronous release remains unchanged in Syn II KO mice, even though the asynchronous release component is increased (Fig. 8).

An earlier quantitative study of facilitation of synchronous and asynchronous release at the mouse neuromuscular junction (Bain & Quastel, 1992) led to the suggestion that facilitation of asynchronous release arises from the accumulation of residual Ca2+, while facilitation of synchronous release also modifies a sensitivity of the release machinery to Ca2+. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been demonstrated that synchronous and asynchronous release components have different sensitivity to Ca2+ and Sr2+ ions, thus suggesting that different Ca2+ sensors regulate synchronous and asynchronous release components (Goda & Stevens, 1994). Recently, it has been demonstrated that synchronous but not asynchronous release is governed by Ca2+ binding to synaptotagmin I (Nishiki & Augustine, 2004). Thus, synchronous and asynchronous release components are selectively regulated, and therefore facilitation of synchronous and asynchronous release could involve different mechanisms.

Our study demonstrated that synapsin II inhibits facilitation of the synchronous release component without affecting facilitation of asynchronous release. We believe that facilitation of asynchronous release arises from accumulation of residual Ca2+, while frequency facilitation of synchronous release is additionally accelerated by a molecular mechanism regulated by synapsin II.

Facilitation is not a uniform process, but it is comprised of several distinguishable components with different decay times (Zucker & Regehr, 2002 for review). It is possible that frequency facilitation at continuous stimulation (Fig. 8) may involve mechanisms different from accumulation of free residual Ca2+ which underlies paired-pulse facilitation. It has already been demonstrated that frequency facilitation can be parsimoniously explained by accumulation of releasable vesicles (Bykhovskaia et al. 2000, 2001), and it is associated with the increase in the releasable pool (Bykhovskaia et al. 2004). Furthermore, at continuous stimulation synaptic enhancement is regulated by the vesicle priming factor Munc 13 (Rosenmund et al. 2002). Our present study suggests that the mechanisms of vesicle priming and release, which affect frequency facilitation, may involve synapsin II.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIH grant (R01 MH61059).

References

- Bain AI, Quastel DM. Multiplicative and additive Ca2+-dependent components of facilitation at mouse endplates. J Physiol. 1992;455:383–405. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom O, Evergren E, Tomilin N, Kjaerulff O, Low P, Brodin L, Pieribone VA, Greengard P, Shupliakov O. Colocalization of synapsin and actin during synaptic vesicle recycling. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:737–747. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykhovskaia M, Polagaeva E, Hackett JT. Hyperosmolarity reduces facilitation by a Ca2+-independent mechanism at the lobster neuromuscular junction: possible depletion of the releasable pool. J Physiol. 2001;537:179–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0179k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykhovskaia M, Polagaeva E, Hackett JT. Mechanisms underlying different facilitation forms at the lobster neuromuscular synapse. Brain Res. 2004;1019:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykhovskaia M, Worden MK, Hackett JT. An algorithm for high-resolution detection of postsynaptic quantal events in extracellular records. J Neurosci Meth. 1996;65:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykhovskaia M, Worden MK, Hackett JT. Stochastic modeling of facilitated neurosecretion. J Comput Neurosci. 2000;8:113–126. doi: 10.1023/a:1008917130947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi P, Greengard P, Ryan TA. Synaptic vesicle mobilization is regulated by distinct synapsin I phosphorylation pathways at different frequencies. Neuron. 2003;38:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousin MA, Malladi CS, Tan TC, Raymond CR, Smillie KJ, Robinson PJ. Synapsin I-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediates synaptic vesicle delivery to the readily releasable pool. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29065–29071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Chi P, Blanpied TA, Xu Y, Magarinos AM, Ferreira A, Takahashi RH, Kao HT, McEwen BS, Ryan TA, Augustine GJ, Greengard P. Regulation of neurotransmitter release by synapsin III. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4372–4380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04372.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Chin LS, Li L, Lanier LM, Kosik KS, Greengard P. Distinct roles of synapsin I and synapsin II during neuronal development. Mol Med. 1998;4:22–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Han HQ, Greengard P, Kosik KS. Suppression of synapsin II inhibits the formation and maintenance of synapses in hippocampal culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9225–9229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A, Kosik KS, Greengard P, Han HQ. Aberrant neurites and synaptic vesicle protein deficiency in synapsin II-depleted neurons. Science. 1994;264:977–979. doi: 10.1126/science.8178158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier GF, Padykula HA. Cytological studies of fiber types in skeletal muscle. A comparative study of the mammalian diaphragm. J Cell Biol. 1966;28:333–354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.28.2.333. 10.1083/jcb.28.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis KD, Mossner R, Neher E. Protein kinase C enhances exocytosis from chromaffin cells by increasing the size of the readily releasable pool of secretory granules. Neuron. 1996;16:1209–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80147-6. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda Y, Stevens CF. Two components of transmitter release at a central synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12942–12946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P, Valtorta F, Czernik AJ, Benfenati F. Synaptic vesicle phosphoproteins and regulation of synaptic function. Science. 1993;259:780–785. doi: 10.1126/science.8430330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett JT, Cochran SL, Greenfield LJ, Jr, Brosius DC, Ueda T. Synapsin I injected presynaptically into goldfish mauthner axons reduces quantal synaptic transmission. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63:701–706. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han HQ, Nichols RA, Rubin MR, Bahler M, Greengard P. Induction of formation of presynaptic terminals in neuroblastoma cells by synapsin IIb. Nature. 1991;349:697–700. doi: 10.1038/349697a0. 10.1038/349697a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilfiker S, Pieribone VA, Czernik AJ, Kao HT, Augustine GJ, Greengard P. Synapsins as regulators of neurotransmitter release. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:269–279. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0378. 10.1098/rstb.1999.0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilfiker S, Schweizer FE, Kao HT, Czernik AJ, Greengard P, Augustine GJ. Two sites of action for synapsin domain E in regulating neurotransmitter release. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:29–35. doi: 10.1038/229. 10.1038/229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka M, Hammer RE, Sudhof TC. A phospho-switch controls the dynamic association of synapsins with synaptic vesicles. Neuron. 1999;24:377–387. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80851-x. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80851-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka M, Sudhof TC. Synapsins I and II are ATP-binding proteins with differential Ca2+ regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1425–1429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1425. 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic JN, Czernik AJ, Fienberg AA, Greengard P, Sihra TS. Synapsins as mediators of BDNF-enhanced neurotransmitter release. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:323–329. doi: 10.1038/73888. 10.1038/73888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic JN, Sihra TS, Nairn AC, Hemmings HC, Jr, Greengard P, Czernik AJ. Opposing changes in phosphorylation of specific sites in synapsin I during Ca2+-dependent glutamate release in isolated nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7944–7953. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-07944.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Chin LS, Shupliakov O, Brodin L, Sihra TS, Hvalby O, Jensen V, Zheng D, McNamara JO, Greengard P. Impairment of synaptic vesicle clustering and of synaptic transmission, and increased seizure propensity, in synapsin I-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9235–9239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Gruner JA, Sugimori M, McGuinness TL, Greengard P. Regulation by synapsin I and Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II of the transmitter release in squid giant synapse. J Physiol. 1991;436:257–282. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, McGuinness TL, Leonard CS, Sugimori M, Greengard P. Intraterminal injection of synapsin I or calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alters neurotransmitter release at the squid giant synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:3035–3039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy VN. Spreading synapsins. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1155–1157. doi: 10.1038/nn1201-1155. 10.1038/nn1201-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiki T, Augustine GJ. Synaptotagmin I synchronizes transmitter release in mouse hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6127–6132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1563-04.2004. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1563-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleskevich S, Walmsley B. Phosphorylation regulates spontaneous and evoked transmitter release at a giant terminal in the rat auditory brainstem. J Physiol. 2000;526:349–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00349.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padykula HA, Gauthier GF. The ultrastructure of the neuromuscular junctions of mammalian red, white, and intermediate skeletal muscle fibers. J Cell Biol. 1970;46:27–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.46.1.27. 10.1083/jcb.46.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieribone VA, Shupliakov O, Brodin L, Hilfiker-Rothenfluh S, Czernik AJ, Greengard P. Distinct pools of synaptic vesicles in neurotransmitter release. Nature. 1995;375:493–497. doi: 10.1038/375493a0. 10.1038/375493a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards DA, Guatimosim C, Betz WJ. Two endocytic recycling routes selectively fill two vesicle pools in frog motor nerve terminals. Neuron. 2000;27:551–559. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00065-9. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzoli SO, Betz WJ. The structural organization of the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. Science. 2004;303:2037–2039. doi: 10.1126/science.1094682. 10.1126/science.1094682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosahl TW, Spillane D, Missler M, Herz J, Selig DK, Wolff JR, Hammer RE, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC. Essential functions of synapsins I and II in synaptic vesicle regulation. Nature. 1995;375:488–493. doi: 10.1038/375488a0. 10.1038/375488a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Sigler A, Augustin I, Reim K, Brose N, Rhee JS. Differential control of vesicle priming and short-term plasticity by Munc13 isoforms. Neuron. 2002;33:411–424. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00568-8. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Moser T, Xu T, Neher E. Cytosolic Ca2+ acts by two separate pathways to modulate the supply of release competent vesicles in chromaffin cells. Neuron. 1998;20:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80504-8. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Sullivan JM. Regulation of the readily releasable vesicle pool by protein kinase C. Neuron. 1998;21:885–893. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80603-0. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Shinoe T, Ito Y, Misawa H, Tojima T, Ito E, Yoshioka T. A novel function of synapsin II in neurotransmitter release. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;85:133–143. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00231-x. 10.1016/S0169-328X(00)00231-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]