Abstract

Inward rectifier K+ channels commonly exhibit long openings (slow gating) punctuated by rapid open–close transitions (fast gating), suggesting that two separate gates may control channel open–closed transitions. Previous studies have suggested possible gate locations at the selectivity filter and at the ‘bundle crossing’, where the two transmembrane segments (M1 and M2) cross near the cytoplasmic end of the pore. Wild-type Kir2.1 channels exhibit only slow gating, but mutations in the cytoplasmic pore domain at E224 and E299 have been shown to induce fast flickery gating. Since these mutations also affect polyamine affinity, we conjectured that the fast gating mechanism might affect the kinetics of polyamine block/unblock if located more intracellularly than the polyamine blocking site in the pore. Neutralization of either E224 or E299 induced fast gating and slowed both block and unblock rates by the polyamine diamine 10. The slowing of polyamine block/unblock was partly relieved by raising pH from 7.2 to 9.0, which also slowed fast gating kinetics. These findings indicate that the fast flickery gate is located intracellularly with respect to the polyamine pore-plugging site near D172, thereby excluding the selectivity filter, and implicating the bundle crossing or more intracellular site as the gate. As additional proof, fast gating induced at the selectivity filter by disrupting P loop salt bridges in WT-E138D–E138D-WT tandem had no effect on polyamine block and unblock rates. The pH sensitivity of fast gating in E224 and E299 mutants was attributed to the protonation state of H226, since the double mutant E224Q/H226K induced fast gating which was pH insensitive. Moreover, introducing a negative charge in the 224–226 region was sufficient to prevent fast gating, since the double mutant E224Q/H226E rescued wild-type Kir2.1 slow gating. These observations implicate E224 and E299 as allosteric modulators of a fast gate, located at the bundle crossing or below in Kir2.1 channels. By suppressing fast gating, these negative charges facilitate polyamine block and unblock, which may be their physiologically important role.

Inward rectifier K+ (Kir) channels are essential for maintaining resting membrane potential and regulating excitability (Doupnik et al. 1995; Hille, 2001). Inward rectification is primarily caused by voltage-dependent block of outward currents by Mg2+ and polyamines (Matsuda et al. 1987; Vandenberg, 1987; Ficker et al. 1994; Lopatin et al. 1994; Fakler et al. 1995). In strong inward rectifiers such as Kir2.1, negatively charged residues in two different pore-lining regions are critical for high affinity polyamine block: D172 in the second transmembrane domain (M2) (Lu & MacKinnon, 1994; Stanfield et al. 1994; Wible et al. 1994; Yang et al. 1995), and E224 and E299 in the cytoplasmic C-terminus (Taglialatela et al. 1995; Yang et al. 1995; Kubo & Murata, 2001). Together, these residues coordinate the binding and entry of polyamines into their pore-occluding site (Lee et al. 1999; Kubo & Murata, 2001; Xie et al. 2002, 2003).

However, Kir channels also exhibit intrinsic gating (spontaneous open–close transitions) in the absence of polyamines and Mg2+. In Kir2.1 channels, the relationship of this intrinsic gating mechanism to inward rectification is controversial (Shieh et al. 1996; Guo & Lu, 2000; Matsuda et al. 2003). Channel activities are regulated by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) in all Kir channels, including Kir2.1. In addition, ligand-binding-dependent gating is regulated by Gβγ in Kir3 and by ATP in Kir6 channels. Identifying the physical location of these intrinsic and ligand-dependent gates has been a topic of intense study recently. Single channel recordings reveal that Kir3 and Kir6 channels open in bursts (a slow gating process), during which the channel rapidly flickers between open and closed states (a fast gating process). Two putative locations for Kir channel gates have been proposed (Lu et al. 2001; Bichet et al. 2003; Phillips et al. 2003; Phillips & Nichols, 2003; Proks et al. 2003; Xiao et al. 2003), at the selectivity filter and at the ‘bundle crossing’, where the M1 and M2 transmembrane segments cross near the cytoplasmic end of the transmembrane pore, according to recent structural data (Doyle et al. 1998; Jiang et al. 2002; Kuo et al. 2003). Point mutation studies in Kir6.2 channels suggest that fast gating may be controlled by a gate located at the selectivity filter (Proks et al. 2001), whereas slow gating may be regulated at the bundle crossing (Trapp et al. 1998; Tucker et al. 1998; Loussouarn et al. 2000). The idea of two independent gates is further supported in Kir3.2 channels (Yi et al. 2001).

Unlike Kir3 or Kir6 channels, however, Kir2.1 channels exhibit only slow gating: when channels are open, they do not show fast flickery openings and closings. This slow gating has been attributed to movement of the selectivity filter gate (Choe et al. 1999; Lu et al. 2001; So et al. 2001). However, it has been shown that mutations in the cytoplasmic pore domain of Kir2.1 channels at E224 and E299 can cause fast gating to appear (Yang et al. 1995; Kubo & Murata, 2001; Xie et al. 2002). When E224 or E299 were replaced with neutral residues (G, A, Q, or S), single channel openings became very flickery with reduced conductance. Interestingly, these mutations are at the same sites that are also important for regulating inward rectification by polyamines. It has been also reported that the disruption of P loop salt bridges in selectivity filter (WT-E138D–E138D-WT tandem) caused a fast flickery gating, which did not affect polyamine blocking affinity (Yang et al. 1997).

In this paper, we explore the mechanism of this fast gating and its relationship to polyamine block. In contrast to the fast gating in Kir6 or Kir3 channels thought to occur at the selectivity filter, we present evidence that the induced fast flickery gating in the mutant Kir2.1 channels occurs more intracellularly, at bundle crossing or lower, where it affects the ability of polyamines to access their pore-blocking site. Negative charge in the E224 and E299 region plays a key role in preventing fast gating and enhancing polyamine block/unblock kinetics in the wild-type (WT) channel.

Methods

Molecular biology and preparation of oocytes

The Kir2.1 cDNA (Kubo et al. 1993) was generously provided by Dr Lily Y. Jan. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) mutagenesis was carried out by the QuickChange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) (Ho et al. 1989) to generate the Kir 2.1 mutants. cRNAs were synthesized using T7 polymerase (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX, USA) and injected into stage IV–V Xenopus oocytes.

Oocytes were isolated by partial ovariectomy from mature female Xenopus anaesthetized with 0.1% tricaine. All of the frogs were humanely killed at the end of the oocyte collection. The use and care of the animals in these experiments were approved by the Chancellor's Animal Research Committee at UCLA. The oocytes were then defolliculated by treatment for 1 h with 1 mg ml−1 collagenase (Type II, Life Technologies) in Barth's solution containing (mm): 88 NaCl, 1 KCl, 2.4 NaHCO3, 0.3 Ca(N2O6).4H2O, 0.41 CaCl2, 0.82 MgSO4, 15 Hepes and 50 mg ml−1 gentamicin, 10 mg ml−1 Baytril (Bayer, Shawnee, Kansas, USA), pH 7.6. The day after collagenase treatment, selected oocytes were pressure-injected with ∼50 nl RNA (1–100 ng ml−1). Oocytes were maintained at 18°C in Barth's solution and electrophysiological studies were conducted 1–3 days later. Immediately before recording, the vitelline membrane was removed.

Electrophysiology and data analysis

Macroscopic currents recording from excised inside-out giant patches from injected oocytes with an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) at room temperature, as previously described (Shieh et al. 1996). Patch electrodes were pulled from thin-wall borosilicate glass (Garner Glass Co., Claremont, CA, USA) and had a tip diameter of 20–30 μm after fire polishing. The patch electrode solution contained: 85 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 K2HPO4, 5 KH2PO4, pH 7.2 with KOH. The standard bath solution contained (mm): 85 KCl, 5 EDTA, 5 K2HPO4, 5 KH2PO4, pH adjusted to the desired level with KOH. Spermine or spermidine was added to the bath solution. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). The leak current corrections were made in most of the patches by subtracting current in the presence of 30 mm TEA or after complete rundown. The currents were measured at the beginning of the test potential pulses after capacitance transients. Data were filtered with an eight-pole Bessel filter (Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA, USA) at 2 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz via a DigiData 1200 interface (Axon Instruments). Since the outward currents (at positive voltage) in WT channel were nearly completely blocked by 100 μm diamine 10 (DA10), with kinetics too rapid to resolve, we chose to measure blocking rate of inward current at −20 mV (Fig. 2B bottom panel, left). Unblock rate was measured at −60 mV (Fig. 2B bottom panel, right). The kinetics of polyamine block and unblock were fitted to a single exponential function I = B exp(−t/τ) + Bo, where I is the current amplitude, B the scaling factor, Bo the offset, and τ a time constant.

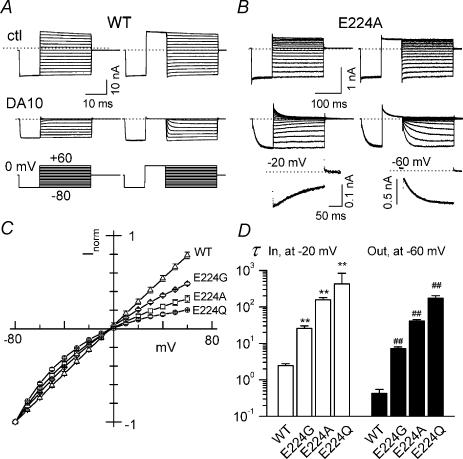

Figure 2. Replacement of E224 with neutral residues induces intrinsic inward rectification in Kir2.1 channels and slows polyamine blocking and unblocking.

A and B, representative macroscopic current traces recorded from inside-out giant patches from Xenopus oocytes expressing WT and E224A channels. Upper panel: control recordings ∼5 min after patch excision. Lower panel: in the presence of 100 μm diamine 10 (DA10). Notice the different time scales for WT and E224A. The voltage pulse protocols are illustrated at the bottom of A. Example of how block rate at −20 mV and unblock rate at −60 mV were measured are shown at the bottom of B. The data were well fitted to a single exponential function as indicated by a continuous line in each case. C, I–V relationship for WT and E224-neutralized channels, showing a blocker-independent intrinsic inward rectification in the mutant channels. D, time constants (τ) for DA10 blocking (in) at −20 mV and unblocking (out) at −60 mV obtained by a single exponential fit. ** and ##P < 0.05 compared with WT.

Single channel activities were recorded from inside-out patches excised from oocytes injected with WT and mutant channel. Patch electrodes were pulled from thick-wall borosilicate glass (Warner Instruments Inc., Hamden, CT, USA) and had a resistance of 5–8 MΩ when filled with the pipette solution. Electrodes were coated near their tips with Sylgard (Dow Corning Co., Midland, MI, USA) or N,N-dimethyltrimethylsilylamine (Fluka) to reduce electrical capacitance. The patch electrode solution contained: 140 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 5 K2HPO4, 5 KH2PO4, pH 7.2 with KOH. The standard bath solution contained (mm): 140 KCl, 5 EDTA, 5 K2HPO4, 5 KH2PO4, pH adjusted to the desired level with KOH. The rundown of channel activity was delayed by treating inside-out patches with 2 mm MgATP in the EDTA-free bath solution. In some experiments, 5 mm NaF and 0.1 Na3VO4 were also included in the bath solution to retard hydrolysis of endogenous PIP2 (Huang et al. 1998). Data were filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. Data acquisition and analysis were carried out using pCLAMP8 or 9 software (Axon Instruments). The all-point histograms were constructed with a bin width of 0.1 pA from data records of ∼10 s. The current variances for the open (δ2O) and closed states (δ2C) were calculated using Clampfit 9 (Axon Instruments). The ratios of δ2O/δ2C were used in order to normalize the noise level at closed state and evaluate the open channel noise levels under various conditions.

All experiments were conducted at room temperature (20–24°C). The paired or unpaired Student's t test was conducted with P-value < 0.05 being considered as statistically significant.

Results

E224 mutations induce fast gating and reduce polyamine block and unblock rates

Single channel activities were recorded from inside-out patches excised into Mg2+- and polyamine-free solution. WT Kir2.1 channels show long open and closed times, with a high Po (> 0.9), indicating that Kir2.1 exhibits slow gating, but not fast intraburst gating characteristic of other Kir channels (Fig. 1A). However, mutations in the cytoplasmic pore region at E224 or E299 cause channels to flicker during the long openings (Yang et al. 1995; Kubo & Murata, 2001; Xie et al. 2002). As shown in Fig. 1A and B, neutralization of E224 to either Gly (G) or Ala (A) induced an extremely fast flickery gating process that was not fully resolved at the recording bandwidth, as indicated by high δ2O/δ2C values and wide distribution in the all-point histograms compared to WT channel. It is notable that there are two open-state peaks in E224G and E224A histograms, suggesting the existence of substates (indicated by arrows) and the flickery gating may represent the fast transitions between fully open states, substates and closed states. The slow gating transitions defining the bursts of flickery openings with intervening long closed times remained unchanged. The unitary amplitude–voltage (i–V) relations for WT, E224G and E224A are plotted in Fig. 1C. Since the i–V relationship is not linear in the mutant channel, we compared the chord conductance at −160 mV. The single channel conductance for WT channel was 30.0 ± 1.8 pA (n = 10), and was reduced to 26.6 ± 1.5 pA (n = 12) and 15.5 ± 0.9 pA (n = 5) in the E224G and E224A mutants, respectively. Figure 1D illustrates that when the single channel current amplitudes at −160 mV were normalized, the chord conductance was voltage dependent. We attempted to record the single channel currents from E224Q channels, but were unsuccessful due to their much reduced single channel conductance. Instead, we only obtained indistinct multiple channel recording (data not shown).

Figure 1. Replacement of E224 with neutral residues induces fast flickery gating kinetics and reduces single channel chord conductance.

A, single channel traces recorded from inside-out patches excised from Xenopus oocytes expressing WT, E224G or E224A channels. Holding potentials (0, −80 and −160 mV) are indicated above each trace. The ratio of current variances for the open (δ2O) and closed states (δ2C) is indicated for each channel at −160 mV. Segments of the traces at −160 mV are expanded to compare open-channel kinetics. The arrows indicate long dwell time at a sublevel. B, all-point histograms from the single channel traces of wild-type (WT), E224G and E224A at holding potential of −160 mV. The arrows indicate substate peaks corresponding to that in A (bottom trace). C, left: Single channel i–V relation for WT (○), E224G (▵) and E224A (□) channels. Compared with the linear i–V relation in WT, mutant channels show voltage-dependent reduction of chord conductance (dotted lines show chord conductances at −160 mV). Right: normalized i–V curve from the same data.

Figure 2A and B shows representative recordings of macroscopic currents of WT and E224A channels obtained using inside-out giant-patches excised from Xenopus oocytes. After extensively washing with polyamine and Mg2+-free solution, the WT current displayed a liner current–voltage (I–V) relationship. In contrast, E224A channels showed inward rectification in the absence of Mg2+ or polyamines, as reported previously (Yang et al. 1995; Xie et al. 2002). Figure 2C shows I–V curves for WT, E224A, E224G and E224Q channels under control conditions. Intrinsic inward rectification occurred, to different degrees, with all three mutants, corresponding to the voltage-dependent change of single channel chord conductance in Fig. 1D. The extent of the intrinsic inward rectification depended on the size of side chain of the substituting residue. Using the ratio of current at +60 mV to that at −60 mV (I+60mV/I−60mV) as an index of inward rectification, Fig. 2C shows that I+60mV/I−60mV decreased from 0.71 ± 0.02 (n = 4) to 0.50 ± 0.02 (n = 8) to 0.34 ± 0.06 (n = 4) when the size of side chain of substituted residue increased from –H (E224G) to −CH3 (E224A) to −CH2CH2CONH2 (E224Q). These results are consistent with a recent simulation study with Brownian dynamics showing that the inward rectification was caused by reducing the dipole charges near the intercellular entrance, and the extent of the non-linearity depended on the radius of the intracellular pore (Chung et al. 2002). Therefore the voltage dependence of the fast flickery gating might reflect allosteric modulation of the electric field (membrane pore) domain transmitted from the cytoplasmic pore (E224/H226/E299) domain after mutation.

We also examined the blocking/unblocking kinetics of the polyamine analogue diamine 10 (DA10, 100 μm) on WT and mutated channels (Fig. 2A and B lower traces). Figure 2D compares the time constant of block (τin, at −20 mV) and unblock (τout, at −60 mV), respectively. Both block and unblock rates by DA10 were well-fitted by single exponentials (see Methods). Both blocking and unblocking kinetics were slowed in the E224-neutralized channels, in proportion to the size of side chain of the substituted amino acid. For example, the unblocking rate of DA10 slowed down by ∼17-, ∼100-, and ∼400-fold when E224 was replaced by G, A and Q, respectively.

Thus, the data obtained from WT and mutant channels showed a correlation between the fast flickery gating, the degree of intrinsic inward rectification and polyamine block/unblock rates in the E224-neutralized channels.

pH affects channel gating in E224 mutants

Unlike WT Kir2.1 channels, mutant E224 channels were sensitive to cytoplasmic pH (pHi). In single channel recordings (Fig. 3), raising pHi from 7.2 to 9.0 reduced the flickeriness of channel openings (δ2O/δ2C decreased from 10.4 to 5.7) and eliminated the substates. The apparent unitary amplitude increased from 1.1 to 2.0 pA. Consistent with these effects, Fig. 4 shows that whereas macroscopic currents from WT channels were not significantly affected by raising pHi from 7.2 to 9.0, both inward and outward currents from E224A, E224G, and E224Q channels increased (Fig. 4A, B and D). The increase in current at −80 mV averaged 55 ± 10%, 86 ± 14% and 200 ± 12% in E224G, E224A and E224Q channels, respectively. In addition, the degree of intrinsic inward rectification was reduced at pHi 9.0, as indicated by the ratio of current at +60 mV and −60 mV (Fig. 4C).

Figure 3. Raising pH slows fast flickery gating kinetics in E224A channels.

A, single channel activity recorded at a holding potential of −100 mV. The pH of the solution was changed from 7.2 to 9.0 at the arrow under the trace. B, the expanded traces from the periods a (pH 7.2) and b (pH 9.0) in A. The ratios of current variances for the open (δ2O) and closed states (δ2C) are indicated for pH 7.2 and pH 9.0, respectively. C, all-point histograms from the single channel traces at pH 7.2 (left) and pH 9.0 (right). A substate observed only at pH 7.2 is as indicated by the arrow.

Figure 4. Raising pH from 7.2 to 9.0 increases both inward and outward current and weakens intrinsic inward rectification in the E224-neutralized channels.

A, macroscopic current traces of WT and E224A channels at pH of 7.2 (upper panels) and 9.0 (lower panels). B, I–V relationship for WT (left) and E224A (right) at pH of 7.2 (□) and 9.0 (○), respectively. The curve at pH 7.2 for E224A is normalized (▪, 7.2N) at −80 mV to that at pH 9.0. C, the ratios of the current at +60 and −60 mV as an index of rectification intensity. ##P < 0.05 compared with pH 7.2. D, percentage increase in current at −80 mV induced by the elevation of pH from 7.2 to 9.0 in WT and mutant channels. **P < 0.05 compared with WT.

E299S and E299Q channels also showed flickery openings in their single channel currents and exhibited intrinsic inward rectification, but to a lesser extent than the E224-neutralized channels. This is consistent with previous results (Kubo & Murata, 2001). Raising pHi from 7.4 to 9.0 also increased macroscopic currents in E299Q channels by 39.8 ± 4.0% at −80 mV. The pHi effect was less apparent in E299S channels, however.

pHi also affects polyamine block and unblock rates in E224 mutants

Raising pHi from 7.2 to 9.0 had no effect on block and unblock rates for DA10 in WT channels (Fig. 5A, C and D). Thus, the protonation state change of the DA10 molecule over this pH range does not affect its blocking or unblocking kinetics. In E224A channels, however, Fig. 5 shows that raising pHi from 7.2 to 9.0 increased both the block and unblock rates of DA10 by ∼28- and 18-fold (Fig. 5B, C and D). Thus, the slowing of the flicker rate at pHi 9.0 (Fig. 3) enhanced the access of DA10 to and exit from its binding site in the pore of E224A channels. The effect was reversible when pH was returned to 7.2.

Figure 5. pH-induced gating changes affect DA10 blocking and unblocking rates in E224A channels.

A, macroscopic current traces recorded from WT channels in the presence of 100 μm DA10. The elevation of pH from 7.2 (upper panels) to 9.0 (lower panels) has no effect on the rates of DA10 blocking (left) and unblocking (right). B, the same protocol for E224A channels. The elevation of pH from 7.2 to 9.0 speeds up both blocking and unblocking rates. The voltage protocols in A and B are the same with that in Fig. 1. C, summary of pH effect on DA10 unblocking rates in WT and E224A.

H226 mediates the pHi sensitivity of gating in E224 mutants

We examined the amino acid sequence of Kir2.1 to identify pH-sensitive residues near E224 which might mediate the effects of pHi on gating, and identified a histidine (pK value 6.04) at position H226 as a possible candidate. From the cytoplasmic pore structure of Kir2.1 (Xie et al. 2003) predicted from Kir3.1 crystal structure (Nishida & MacKinnon, 2002), the side chain of H226 is ∼7 Å away from E224 and, like E224, points towards the channel pore. When H226 was mutated to the non-titratable charged residues K or E in the background of E224Q, neither of the double mutant channels exhibited pHi sensitivity. As shown in Fig. 6, E224Q/H226K channels exhibited strong intrinsic inward rectification in the absence of Mg2+ or polyamines, similar to E224Q channels. However, raising pHi from 7.2 to 9.0 had no significant effect on the current amplitude or degree of inward rectification. In contrast, the double mutant E224Q/H226E behaved similar to wild-type channels, with a linear I–V relation in macroscopic current, non-flickery single channel kinetics with a unitary conductance of 29.6 ± 0.5 pS (n = 4) and absent pHi sensitivity. Thus, the replacement of histidine with a negatively charged residue reversed the effects of neutralizing E224. Based on these observations, we conclude fast gating in E224A channels is modulated by the protonation state of H226.

Figure 6. H226 is responsible for the pH sensitivity of channel gating in E224-neutralized channels.

A, macroscopic current recordings from the double mutation E224Q/H224K (upper panels) and E224K/H226E (lower panels) at pH 7.2 (left) and 9.0 (right), respectively. B, normalized I–V relationships. While E244Q/H226K shows strong intrinsic inward rectification, E224Q/H226E has a WT-like linear relation. However, elevation of pH from 7.2 (squares) to 9.0 (circles) has no effect on either double mutant. C, single channel recording from E224Q/H226E exhibits a WT-like open–close kinetics without fast flickery openings.

The effects of pHi on the kinetics of DA10 block and unblock in E224 mutants could also be attributed to the protonation state of H226. In the double mutation E224Q/H299K, DA10 block and unblock rates were very slow, similar to E224Q. Raising pHi from 7.2 to 9.0 had no effect on block (not shown) or unblock rate by DA10 (Fig. 7A). E224Q/H229E channels behaved like WT channels, exhibiting fast block (not shown) and unblock by DA10 which was insensitive to pHi (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. H226 is responsible for the pH sensitivity of DA10 unblocking rates in the E224-neutralized channels.

A and B, the elevation of pH has no effect on DA10 unblocking rate in the double mutant channels E224Q/H226K and E224Q/H226E. The voltage pulse protocol for A is illustrated at the bottom of the panel. The voltage protocol for B is the same with that shown in Fig. 2A. C, summary of pH effect on DA10 unblocking rate in the double mutant channels.

Fast flickery gating in the selectivity filter does not affect DA10 block and unblock kinetics

The finding that fast gating in E224 mutants markedly slowed DA10 block and unblock rates suggests that the fast gate is located intracellularly with respect to the DA10 binding site in the pore, such that the gate restricts the ability of DA10 to access or leave this site. Of the two proposed gates in Kir channels, the bundle crossing is located intracellularly, and the selectivity filter extracellularly, with respect to D172, the putative polyamine pore binding site in the transmembrane pore (Fig. 8). Based on this reasoning, the fast gate regulated by E224 is not likely to be located at the selectivity filter. To test the hypothesis that fast gating at the selectivity filter does not markedly affect the kinetics of DA10 block, we examined the block and unblock rates of DA10 in the WT-E138D–E138D-WT tandem Kir2.1 channel, which has been shown to exhibit fast flickery single channel kinetics by disruption of a critical salt bridge at selectivity filter (Yang et al. 1997). Figure 9A shows that at −120 mV, the tandem channel displayed rapid flickery openings (δ2O/δ2C = 8.7), with reduced single channel amplitude. Representative sets of macroscopic currents of the tandem in the presence of 100 μm DA10 are shown in Fig. 9B. No difference was observed in the blocking (left panel) and unblocking (right panel) process between WT-E138D–E138D-WT tandem and WT channels (compared to Fig. 2A). The unblock time constant τout at −60 mV averaged 0.4 ms for both WT-E138D–E138D-WT tandem and WT channels, and the block time constant τin 2.4 and 2.3 ms, respectively (Fig. 9C). Thus, unlike the E224 and E299 mutants, in which DA10 unblock rate was slowed by orders of magnitude, fast flickery gating at the selectivity filter had no effect on the ability of DA10 to exit from its putative blocking site near D172.

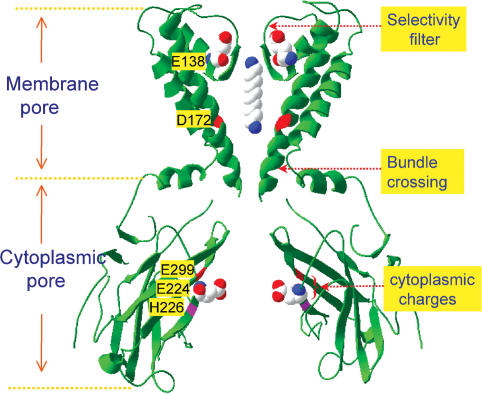

Figure 8. Structure and putative gating locations in Kir channels (based on the structure of KirBac1.1 in closed state).

Equivalent residues critical for polyamine block and fast gating in the Kir2.1 channel are indicated. The side chains of E224 at cytoplasmic pore and E138 at selectivity filter are also shown in space-filling models. In the space-filling models, blue indicates positive charges, red negative charges.

Figure 9. Fast flickery gating induced by mutation at the selectivity filter (WT-E138D–E138D-WT) does not affect DA10 block and unblock kinetics.

A, single channel trace with both long and short time scales, and all-point histogram of the tandem mutant at holding potential of −120 mV. The ratio of current variances for the open (δ2O) and closed states (δ2C) is indicated. B, macroscopic current traces in the presence of 100 μm DA10. C, bar graphs comparing the block time constant τin at −20 mV and unblock time constant τout at −60 mV for WT-E138D–E138D-WT tandem and homologous WT channels.

Discussion

We have previously proposed that E224 and E299 in the cytoplasmic pore region of Kir2.1 channels serve as negative surface charges which bind polyamines, concentrating and pre-positioning them to enter the pore-blocking site near D172 (Xie et al. 2002, 2003). A key piece of evidence supporting this hypothesis came from mutagenesis studies in which neutralization of E224 and/or E299 markedly slowed the blocking and unblocking kinetics of polyamines. We initially speculated that the slower blocking kinetics might be due to the lower effective polyamine concentration in the cytoplasmic pore when the negative charges at E224 and E299 were removed. We also speculated that E224 and E299 might enhance unblock rate by electrostatically attracting the trailing positively charged amine group of the polyamine, thereby facilitating its exit from its pore-plugging site deeper in the pore near D172. However, crystal structures of related K+ channels show that D172 and E224/E299 are ∼35 Å apart (Kuo et al. 2003), while the lengths of DA10, spermidine and spermine are only ∼13, ∼11 and ∼16 Å, respectively. Thus, if the leading amine group of the polyamine is located near D172, its trailing amine group would be too far from E224/E299 (> 20 Å) to interact electrostatically. One possibility is that the pore-plugging position of polyamines is located between D172 and E224/E299, as recently suggested by Guo and Lu (Guo & Lu, 2003; Guo et al. 2003). However, other evidence supports a deeper location between D172 and selectivity filter (Chang et al. 2003; Dibb et al. 2003; Phillips & Nichols, 2003; John et al. 2004). Our present findings are compatible with both possibilities, since we show that the ability of E224/E299 to facilitate unblock of DA10 is not due to an electrostatic interaction between E224/E299 and the polyamine. Rather, our results indicate that E224 and E299 allosterically regulate an intrinsic gating mechanism which affects the access of polyamines to and from their blocking site deeper in the pore near D172. Since this gate must be located intracellularly with respect to D172, the selectivity filter is excluded, and the bundle crossing or an even more intracellular site is the likely location of the fast gate in E224 and E299 mutation. The results in the WT-E138D–E138D-WT tandem channel, in which flickery block is known to be due to the selectivity filter (Fig. 9), further support this conclusion, since flickery block did not affect diamine 10 block and unblock kinetics.

The regulation of this fast gate depends on negative charges in the vicinity of E224. Negative charge at positions 224 and 299 specifically is not required, since the WT gating phenotype (i.e. slow gating without fast gating) was rescued in E224Q channels by placing a negative charge at position 226 in the double mutant E224Q/H226E (Fig. 6). In addition, the protonation state of H226 also influenced the characteristics of fast gating, the degree of intrinsic rectification and DA10 block/unblock rates. However, negative charge in this region is not the only factor influencing the fast gating. Different neutral substitutions (G, A, and Q) had different effects on fast gating, which correlated appropriately with their effects on polyamine block and unblock rates. Generally, larger side chains had bigger effects on fast gating, the degree of intrinsic inward rectification and DA10 block/unblock rates. Since all the side chains of E224/E299/H226 protrude into the cytoplasmic pore, which forms the K+ ion permeation pathway, this side chain size effect could be due to a steric hindrance of the pathway at the cytoplasmic pore region for both K+ permeation and polyamine blocking. However, it is also possible that the 224 and 299 sites control fast gating by an allosteric mechanism. For example, if E224 or E299 are involved in forming ion pairs between subunits (as reported for the Kir6.2 channel in which E229 pairs with R314; Lin et al. 2003), this might explain a destabilization of the permeation pathway when these residues are neutralized. Alternatively, the possible conformational changes induced by pre-binding of permeant ions (K+) with the negative charged rings at E224/E299 in the cytoplasmic pore might also affect channel gating. The similar mechanism has been proposed to explain the single channel kinetic changes (including substates) induced by backbone mutations in the selectivity filter (Lu et al. 2001). Further experiments will be necessary to test these possibilities.

These findings suggest that gating processes may differ among Kir subfamilies. Previous studies in Kir3 and Kir6 channels have suggested that fast gating may be controlled by a gate at the selectivity filter (Guo & Kubo, 1998; Choe et al. 2000, 2001; Proks et al. 2001; Yi et al. 2001), while the slow gate might correspond to a gate at the bundle crossing (Trapp et al. 1998; Tucker et al. 1998; Loussouarn et al. 2000; Yi et al. 2001). In the WT Kir2.1 channel, on the contrary, slow gating appears to be regulated at the selectivity filter (Choe et al. 1999; Lu et al. 2001; So et al. 2001). To our knowledge, the polyamine trapping results shown here are the first evidence to indicate that a fast gating process can occur at or below bundle crossing and affect polyamine blockage. In conclusion, the present study reveals a novel fast gating mechanism in Kir2.1 channels which is located at or below bundle crossing and is regulated by a ring of negative charges at E224 and E299 in the cytoplasmic pore. These negative charges prevent fast gating in Kir2.1 channels, and, by doing so, serve the physiologically important function of ensuring rapid blocking and unblocking kinetics of polyamines conferring strong inward rectification.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr L. Y. Jan for providing the Kir2.1 clone and the WT-E138D–E138D-WT tetramer structure. This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI R37 HL60025 (to J.N.W), by American Heart Association, Western States Affiliate Beginning Grant-in-Aid (to L.H.X), and the Kawata and Laubisch Endowments.

References

- Bichet D, Haass FA, Jan LY. Merging functional studies with structures of inward-rectifier K+ channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:957–967. doi: 10.1038/nrn1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HK, Yeh SH, Shieh RC. The effects of spermine on the accessibility of residues in the M2 segment of Kir2.1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 2003;553:101–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.052845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H, Palmer LG, Sackin H. Structural determinants of gating in inward-rectifier K+ channels. Biophys J. 1999;76:1988–2003. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77357-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H, Sackin H, Palmer LG. Permeation properties of inward-rectifier potassium channels and their molecular determinants. J General Physiol. 2000;115:391–404. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.4.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H, Sackin H, Palmer LG. Gating properties of inward-rectifier potassium channels: effects of permeant ions. J Membr Biol. 2001;184:81–89. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung SH, Allen TW, Kuyucak S. Modeling diverse range of potassium channels with Brownian dynamics. Biophys J. 2002;83:263–277. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibb KM, Rose T, Makary SY, Claydon TW, Enkvetchakul D, Leach R, Nichols CG, Boyett MR. Molecular basis of ion selectivity, block, and rectification of the inward rectifier Kir3.1/Kir3.4 K+ channel. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49537–49548. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307723200. 10.1074/jbc.M307723200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupnik CA, Davidson N, Lester HA. The inward rectifier potassium channel family. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:268–277. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80038-7. 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakler B, Brandle U, Glowatzki E, Weidemann S, Zenner HP, Ruppersberg JP. Strong voltage-dependent inward rectification of inward rectifier K+ channels is caused by intracellular spermine. Cell. 1995;80:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficker E, Taglialatela M, Wible BA, Henley CM, Brown AM. Spermine and spermidine as gating molecules for inward rectifier K+ channels. Science. 1994;266:1068–1072. doi: 10.1126/science.7973666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Kubo Y. Comparison of the open-close kinetics of the cloned inward rectifier K+ channel IRK1 and its point mutant (Q140E) in the pore region. Receptors Channels. 1998;5:273–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Lu Z. Pore block versus intrinsic gating in the mechanism of inward rectification in strongly rectifying IRK1 channels. J General Physiol. 2000;116:561–568. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.4.561. 10.1085/jgp.116.4.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Lu Z. Interaction mechanisms between polyamines and IRK1 inward rectifier K+ channels. J General Physiol. 2003;122:485–500. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308890. 10.1085/jgp.200308890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D, Ramu Y, Klem AM, Lu Z. Mechanism of rectiVication in inward-rectifier K; channels. J General#Physiol. 2003;121:261–276. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200208771. 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland MA USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ho S, Hont HD, Pullen JK, Peas LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CL, Feng S, Hilgemann DW. Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gβγ. Nature. 1998;391:803–806. doi: 10.1038/35882. 10.1038/35882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Lee A, Chen J, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure and mechanism of a calcium-gated potassium channel. Nature. 2002;417:515–522. doi: 10.1038/417515a. 10.1038/417515a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John SA, Xie LH, Weiss JN. Mechanism of inward rectification in kir channels. J General Physiol. 2004;123:623–625. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409017. 10.1085/jgp.200409017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y, Baldwin TJ, Jan YN, Jan LY. Primary structure and functional expression of a mouse inward rectifier potassium channel. Nature. 1993;362:127–133. doi: 10.1038/362127a0. 10.1038/362127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo Y, Murata Y. Control of rectification and permeation by two distinct sites after the second transmembrane region in Kir2.1 K+ channel. J Physiol. 2001;531:645–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0645h.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0645h.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Antcliff JF, Rahman T, Lowe ED, Zimmer J, Cuthbertson J, Ashcroft FM, Ezaki T, Doyle DA. Crystal structure of the potassium channel KirBac1.1 in the closed state. Science. 2003;300:1922–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.1085028. 10.1126/science.1085028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, John SA, Weiss JN. Novel gating mechanism of polyamine block in the strong inward rectifier K channel Kir2.1. J General Physiol. 1999;113:555–564. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.4.555. 10.1085/jgp.113.4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YW, Jia T, Weinsoft AM, Shyng SL. Stabilization of the activity of ATP-sensitive potassium channels by ion pairs formed between adjacent Kir6.2 subunits. J General Physiol. 2003;122:225–237. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308822. 10.1085/jgp.200308822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopatin AN, Makhina EN, Nichols CG. Potassium channel block by cytoplasmic polyamines as the mechanism of intrinsic rectification. Nature. 1994;372:366–369. doi: 10.1038/372366a0. 10.1038/372366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loussouarn G, Makhina EN, Rose T, Nichols CG. Structure and dynamics of the pore of inwardly rectifying KATP channels. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1137–1144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1137. 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, MacKinnon R. Electrostatic tuning of Mg2+ affinity in an inward-rectifier K+ channel. Nature. 1994;371:243–246. doi: 10.1038/371243a0. 10.1038/371243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Ting AY, Mainland J, Jan LY, Schultz PG, Yang J. Probing ion permeation and gating in a K+ channel with backbone mutations in the selectivity filter. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:239–246. doi: 10.1038/85080. 10.1038/85080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Oishi K, Omori K. Voltage-dependent gating and block by internal spermine of the murine inwardly rectifying K+ channel, Kir2.1. J Physiol. 2003;548:361–371. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.038844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Saigusa A, Irisawa H. Ohmic conductance through the inwardly rectifying K channel and blocking by internal Mg2+ Nature. 1987;325:156–159. doi: 10.1038/325156a0. 10.1038/325156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida M, MacKinnon R. Structural#bakis of inward rectification: cytoplasmic pore of the G protein-gated inward rectifier GIRK1 at 1.8 A resolution. Cell. 2002;111:957–965. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LR, Enkvetchakul D, Nichols CG. Gating dependence of inner pore access in inward rectifier K+ channels. Neuron. 2003;37:953–962. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00155-7. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LR, Nichols CG. Ligand-induced closure of inward rectifier Kir6.2 channels traps spermine in the pore. J General Physiol. 2003;122:795–805. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308953. 10.1085/jgp.200308953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P, Antcliff JF, Ashcroft FM. The ligand-sensitive gate of a potassium channel lies close to the selectivity filter. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:70–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proks P, Capener CE, Jones P, Ashcroft FM. Mutations within the P-loop of Kir6.2 modulate the intraburst kinetics of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel. J General Physiol. 2001;118:341–353. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.4.341. 10.1085/jgp.118.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh RC, John SA, Lee JK, Weiss JN. Inward rectification of the IRK1 channel expressed in Xenopus oocytes: effects of intracellular pH reveal an intrinsic gating mechanism. J Physiol. 1996;494:363–376. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So I, Ashmole I, Davies NW, Sutcliffe MJ, Stanfield PR. The K+ channel signature sequence of murine Kir2.1: mutations that affect microscopic gating but not ionic selectivity. J Physiol. 2001;531:37–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0037j.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0037j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanfield PR, Davies NW, Shelton PA, Sutcliffe MJ, Khan IA, Brammar WJ, Conley EC. A single aspartate residue is involved in both intrinsic gating and blockage by Mg2+ of the inward rectifier, IRK1. J Physiol. 1994;478:1–6. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taglialatela M, Ficker E, Wible BA, Brown AM. C-terminus determinants for Mg2+ and polyamine block of the inward rectifier K+ channel IRK1. EMBO J. 1995;14:5532–5541. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S, Proks P, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. Molecular analysis of ATP-sensitive K channel gating and implications for channel inhibition by ATP. J General Physiol. 1998;112:333–349. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.3.333. 10.1085/jgp.112.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Proks P, Trapp S, Ryder TJ, Haug T, Reimann F, Ashcroft FM. Molecular determinants of KATP channel inhibition by ATP. EMBO J. 1998;17:3290–3296. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3290. 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg CA. Inward rectification of a potassium channel in cardiac ventricular cells depends on internal magnesium ions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:2560–2564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.8.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wible BA, Taglialatela M, Ficker E, Brown AM. Gating of inwardly rectifying K+ channels localized to a single negatively charged residue. Nature. 1994;371:246–249. doi: 10.1038/371246a0. 10.1038/371246a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Zhen XG, Yang J. Localization of PIP2 activation gate in inward rectifier K+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:811–818. doi: 10.1038/nn1090. 10.1038/nn1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, John SA, Weiss JN. Spermine block of the strong inward rectifier potassium channel Kir2.1: dual roles of surface charge screening and pore block. J General Physiol. 2002;120:53–66. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028576. 10.1085/jgp.20028576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, John SA, Weiss JN. Inward rectification by polyamines in mouse Kir2.1 channels: synergy between blocking components. J Physiol. 2003;550:67–82. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043117. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Jan YN, Jan LY. Control of rectification and permeation by residues in two distinct domains in an inward rectifier K+ channel. Neuron. 1995;14:1047–1054. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90343-7. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JYuM, Jan YN, Jan LY. Stabilization of ion selectivity filter by pore loop ion pairs in an inwardly rectifying potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1568–1572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1568. 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi BA, Lin YF, Jan YN, Jan LY. Yeast screen for constitutively active mutant G protein-activated potassium channels. Neuron. 2001;29:657–667. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00241-0. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]