Abstract

Recently, we and others have shown that luminal K+ recycling via KCNQ1 K+ channels is required for gastric H+ secretion. Inhibition of KCNQ1 by the chromanol 293B strongly diminished H+ secretion. The present study aims at clarifying KCNQ1 subunit composition, subcellular localization, regulation and pharmacology in parietal cells. Using in situ hybridization and immunofluorescence techniques, we identified KCNE2 as the β subunit of KCNQ1 in the luminal membrane compartment of parietal cells. Expressed in COS cells, hKCNE2/hKCNQ1 channels were activated by acidic pH, PIP2, cAMP and purinergic receptor stimulation. Qualitatively similar results were obtained in mouse parietal cells. Confocal microscopy revealed stimulation-induced translocation of H+,K+-ATPase from tubulovesicles towards the luminal pole of parietal cells, whereas distribution of KCNQ1 K+ channels did not change to the same extent. In COS cells the 293B-related substance IKs124 blocked hKCNE2/hKCNQ1 with an IC50 of 8 nm. Inhibition of hKCNE1- and hKCNE3-containing channels was weaker with IC50 values of 370 and 440 nm, respectively. In conclusion, KCNQ1 coassembles with KCNE2 to form acid-activated luminal K+ channels of parietal cells. KCNQ1/KCNE2 is activated during acid secretion via several pathways but probably not by targeting of the channel to the membrane. IKs124 could serve as a leading compound in the development of subunit-specific KCNE2/KCNQ1 blockers to treat peptic ulcers.

KCNQ1 has a ‘Shaker’-type structure with six transmembrane domains and one pore-forming loop. To form native channels, KCNQ1 coassembles with small β subunits, so-called KCNE proteins (Warth, 2003). KCNE1 (IsK or minK) associates with KCNQ1 in heart muscle and the inner ear resulting in a voltage-dependent K+ channel with slow activation kinetics (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Barhanin et al. 1996; Warth & Barhanin, 2002). In mammalian cells, KCNE2 coexpression with KCNQ1 leads to a decrease in current amplitude and abolishes the voltage and time dependence of channel activation (Tinel et al. 2000; Dedek & Waldegger, 2001). Mutations in KCNQ1, KCNE1 and KCNE2 can lead to prolongation of the heart action potential, i.e. ‘Long QT Syndrome, types 1, 5 and 6’, respectively (Wang et al. 1996; Abbott et al. 1999; Priori et al. 1999; Keating & Sanguinetti, 2001). In respiratory and intestinal epithelia KCNE3/KCNQ1 form a basolateral cAMP-activated K+ channel which is voltage independent and constitutively open (Schroeder et al. 2000; Warth & Barhanin, 2003).

Gastric H+ secretion by the H+,K+-ATPase is coupled to K+ uptake and therefore requires a K+ recycling pathway over the luminal membrane (Wolosin & Forte, 1984; Reenstra & Forte, 1990). We and others identified KCNQ1 as a K+ channel in the luminal membrane of gastric parietal cells (Grahammer et al. 2001; Dedek & Waldegger, 2001). Other K+ channels identified in gastric parietal cells and possibly involved in supporting acid secretion are the inward rectifiers Kir4.1 (KCNJ10) (Fujita et al. 2002), Kir2.1 (KCNJ2) (Malinowska et al. 2004) and ROMK (KCNJ1) (Aihara et al. 2003). It is still a matter of debate whether all these channels are involved in gastric acid secretion. Functional experiments suggested an important role of KCNQ1 for K+ recycling over the luminal membrane of parietal cells. The KCNQ1 inhibitor 293B almost completely blocked acid secretion in vivo and in vitro (Grahammer et al. 2001). Moreover, KCNQ1 knockout mice have an impaired gastric acid secretion, high plasma gastrin levels and hypertrophy of gastric oxyntic mucosa (Lee et al. 2000).

KCNE2 and, to a lesser extent, KCNE3 are expressed in human stomach. Both β subunits, when coexpressed with KCNQ1 in mammalian cells, produce a K+ conductance which is active at low extracellular pH – a requirement for luminal K+ channels in gastric parietal cells (Grahammer et al. 2001). In situ hybridization experiments indicated strong KCNE2 expression in mouse parietal cells; therefore, KCNE2 is the likely candidate to associate with KCNQ1 (Dedek & Waldegger, 2001). However, at present the subcellular distribution of KCNE2 in parietal cells has not been examined.

The present study was aimed at characterizing KCNQ1 subunit composition in gastric parietal cells, its regulatory and pharmacological properties and its subcellular localization in the resting and stimulated parietal cell.

Methods

Animals

Animal experiments were performed in full compliance with French regulations on animal care or were approved by the Kantonales Veterinäramt Zürich.

Immunofluorescence

After overnight fasting, gastric acid secretion in mice was stimulated for 20 min by histamine (150 μg kg−1 i.p.), pentagastrin (150 μg kg−1 i.p.) and carbachol (CCH) (70 μg kg−1 i.p.). The animals were then anaesthetized with ketamine (100 mg kg−1 i.p.) plus xylazine (4 mg kg−1 i.p.). After incision of the inferior vena cava, they were transcardially perfused with 3% paraformaldehyde-containing PBS. After the removal and freezing of gastric tissue, cryosections (10 μm) were used for immunostaining. Control animals were not stimulated. For KCNE2 immunofluorescence, stomach tissue of fasted rats was harvested in the same way. As primary antibodies, polyclonal affinity-purified KCNQ1 antibody (Grahammer et al. 2001), polyclonal affinity-purified rKCNE2 antibody (epitope: CEDSKATIHENLGATG; raised in rabbit; Davids, Regensburg, Germany) and a monoclonal antibody against H+,K+-ATPase (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany; Chow & Forte, 1993) were used. Cy3 goat-antirabbit (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands) and Cy5 goat-antimouse (Dianova) were applied as secondary antibodies; HOE 33342 (0.5 μm; Molecular Probes) was used for nuclear staining. The sections were examined with a filter wheel-based imaging system (Universal Imaging Corporation, Dowingtown, PA, USA) mounted on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200M, Zeiss, Jena, Germany; Cy5: excitation 630–650 nm, emission 665–695 nm; Cy3: excitation 528–552 nm, emission 578–637 nm; HOE 33342: excitation 325–390 nm, emission 435–485 nm) and with confocal microscopy (LSM 510, Zeiss, Jena, Germany; Cy3: excitation 543 nm, emission > 560 nm; Cy5 excitation 633 nm, emission > 650 nm).

In situ hybridization

Paraffin-embedded sections of human oxyntic gastric biopsy specimens (archive material) were used. After removal of paraffin, the sections were boiled for 3 min. For construction of antisense and sense probes, a fragment of hKCNE2 was used (bp 136–514 of AF302095). In situ hybridization for the detection of hKCNE2 transcripts was performed under RNase-free conditions. In situ hybridization was carried out in a hybridization cocktail containing 5 × 105 c.p.m. of 35S-labelled RNA probe. The sections were dipped into LM-1 photoemulsion (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and exposed for up to 10 weeks. They were then developed for 3 min in Kodak D-19 developer (Kodak, Hemel Hempstead, UK), rinsed in 1% acetic acid and fixed in Kodak fixer for 3 min. Counterstaining was performed with eosin–haematoxylin. Specimens with counts that were more than four times the background signals were scored as positive. Consecutive sections probed with sense RNA were used as negative controls.

Patch-clamp experiments

hKCNE1, hKCNE2 and hKCNE3 were cloned into the pIRES-CD8 mammalian expression vector (Fink et al. 1998). COS cells were transiently co-transfected with pCI-hKCNQ1 and one of the subunits KCNE1, KCNE2 or KCNE3 (each 0.5 μg per dish) using the FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Whole-cell recordings were performed on transfected cells, as visualized by CD8 expression (Dynabeads M-450 CD8, Dynal GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). The patch pipette solution consisted of (mm): 95 potassium gluconate, 30 KCl, 4.8 Na2HPO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 5 glucose, 2.38 MgCl2, 0.73 CaCl2, 1 EGTA, 3 ATP, pH 7.2. For KCNQ1 pharmacology, cAMP (100 μm) was added to the pipette solution. The extracellular Ringer-type solution consisted of (mm): 145 NaCl, 0.4 KH2PO4, 1.6 K2HPO4, 5 glucose, 1 MgCl2, 1.3 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, pH 7.4 (or pH 5.5). Whole-cell current and conductance were normalized to cell capacitance (pA pF−1 and pS pF−1, respectively) as a measure of cell surface area.

For patch-clamp experiments on parietal cells, mouse gastric glands were harvested after incubation of mouse stomach mucosa in Ringer-type solution containing collagenase IV and pronase E (each 1 mg ml−1; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) for 20 min at 37°C. After shaking, the supernatant was centrifuged at 150 g and gastric glands were re-suspended in enzyme-free Ringer-type solution (4°C). For patch-clamp experiments, parietal cells were identified by differential interference contrast (×40 objective).

Fura-2 Ca2+ measurements

Intracellular Ca2+ was measured with a filter wheel-based imaging system (Universal Imaging Corporation, Dowingtown, PA, USA) mounted on an inverted microscope (Axiovert 200, Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using the acetoxymethyl ester form of the ratiometric Ca2+ dye fura-2 (fura-2-AM, Molecular Probes; excitation at 340 nm and 380 nm, emission 490–530 nm). COS cells grown on glass cover slips were loaded with fura-2-AM (10 μm) for 30 min at 20°C. Mean fluorescence ratios were calculated for single cells using the Metafluor software (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA, USA).

Chemicals

Standard chemicals and substances were purchased from Sigma and Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany); 293B, IKs124, IKs224 and IKs420 were synthesized by Aventis Pharma GmbH (Frankfurt a. M., Germany). 293B, IKs124, IKs224 and IKs420 were dissolved in DMSO (0.1 m) and diluted to their final concentration in the experimental solutions. PIP2 (l-α-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, dipalmitoyl-, pentaammonium salt) was purchased from Calbiochem (VWR, Nürnberg, Germany) and prepared as previously described (Loussouarn et al. 2003).

Statistics

Data are shown as mean values ± s.e.m. from n observations. Student's paired and unpaired t tests were used as appropriate. A P value ≤ 0.05 was accepted to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Association of KCNQ1 and KCNE2 in parietal cells

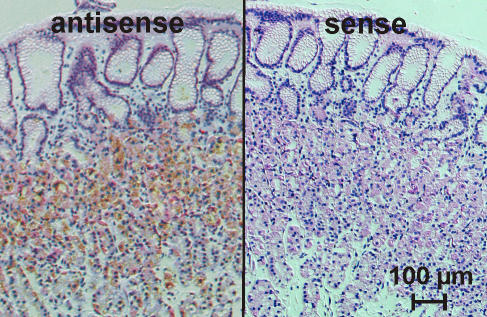

PCR experiments indicated differences in the KCNE1–3 expression pattern between mouse and human with KCNE1 being solely expressed in mouse stomach (Grahammer et al. 2001; Warth & Barhanin, 2002). KCNE2 in situ hybridization experiments in mouse gastric mucosa revealed a predominant staining of parietal cells (Dedek & Waldegger, 2001). In similar experiments on human oxyntic mucosa we could confirm a predominant expression of KCNE2 in human parietal cells (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. KNCE2 in situ hybridization on human gastric mucosa.

Silver grain labelling of parietal cells was detected in antisense probe-treated sections but not in sense controls.

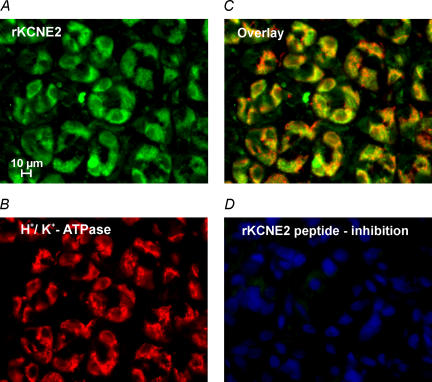

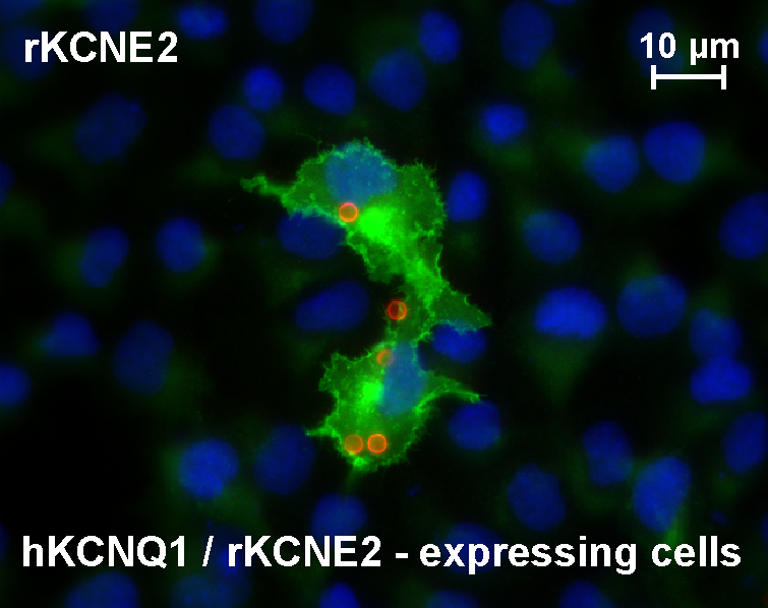

In order to examine the subcellular distribution of KCNE2 in gastric mucosa, we raised a polyclonal antibody against rat KCNE2 which specifically labelled rKCNE2/hKCNQ1-transfected COS cells (Fig. 2). Immunostaining experiments on non-stimulated rat gastric mucosa showed a localization of KCNE2 and H+,K+-ATPase in intracellular compartments similar to that observed for KCNQ1 and H+,K+-ATPase. These observations suggest that KCNE2 is the β subunit of KCNQ1 in the luminal membrane compartment of parietal cells (Fig. 3A–D).

Figure 2. Antibody labelling of COS cells co-transfected with rat KCNE2 and human KCNQ1.

KCNE2-specific staining is shown in the central area (polyclonal, affinity-purified antibody); within this area anti-CD8 beads (circles) indicate transfected cells. HOE33342 nuclear staining is in the background.

Figure 3. KCNE2 in non-stimulated rat gastric mucosa.

A, epifluorescence images of rat oxyntic mucosa stained with polyclonal, affinity-purified KCNE2 antibody. B, H+,K+-ATPase labelling with monoclonal antibody. C, overlay of KCNE2 and H+,K+-ATPase staining shows partial co-localization in parietal cells as described for KCNQ1 and H+,K+-ATPase. D, no staining was observed with the KCNE2 antibody after absorption to the peptide used for immunization; nuclear staining with HOE33342 is visible.

Regulation of KCNQ1/KCNE2

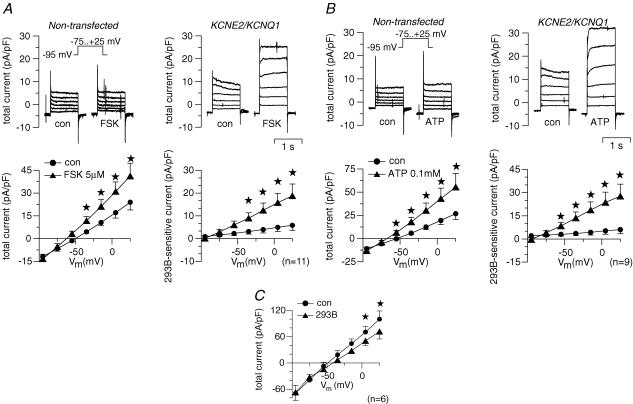

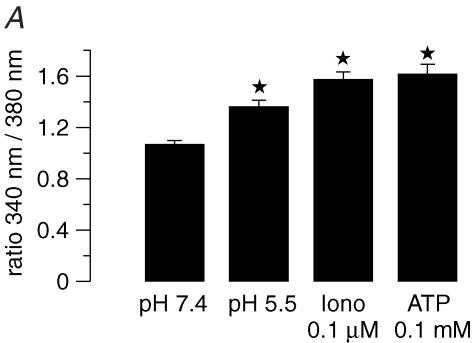

Here we examined whether the putative gastric KCNQ1 channel complex is activated by stimuli known to activate acid secretion. Human KCNQ1 and human KCNE2 were coexpressed in COS cells and whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed to measure 293B-sensitive conductance as a measure for KCNE2/KCNQ1 activity. Stimulation of the cAMP pathway by forskolin (5 μm) increased 293B-sensitive conductance from 50 ± 21 pS pF−1 under control conditions to 187 ± 56 pS pF−1 (n = 11; Fig. 4A). ATP activates the IP3–Ca2+ pathway via purinergic receptor stimulation in COS cells (Fig. 5A). In whole-cell experiments, ATP (100 μm) led to a strong increase in 293B-sensitive conductance from 40 ± 25 to 281 ± 81 pS pF−1 (n = 9) (Fig. 4B). Since ATP can stimulate additional pathways distinct from IP3–Ca2+, ionomycin was used to increase cytosolic Ca2+ independently from purinergic receptors (Fig. 5). In fact, the effect of ionomycin was much lower compared to ATP: ionomycin (100 nm) led to a slight, but not significant, increase in whole-cell current of 23.9 ± 11.4% (clamp voltage, Vc=+5 mV; n = 7; P = 0.08).

Figure 4. Whole-cell patch-clamp measurements of hKCNE2/hKCNQ1-transfected COS cells (A and B) and mouse parietal cells (C).

Cells were clamped stepwise from –95 to +25 mV. A, effect of forskolin (FSK) on a non-transfected cell (whole-cell current normalized to cell capacitance; left upper panel) and a KCNE2/KCNQ1 co-transfected cell (right upper panel). Left lower panel shows the summary of the FSK effect on whole-cell current in KCNE2/KCNQ1 co-transfected cells. Note the shift of reversal potential of the whole-cell current indicating FSK-induced hyperpolarization of the cells. Right lower panel shows the effect of FSK on the 293B-sensitive current as a measure of KCNE2/KCNQ1-specific current. B, effect of ATP on whole-cell current and 293B-sensitve current. Arrangement of panels as described for A. C, effect of 293B on whole-cell current of freshly isolated mouse parietal cells in the continuous presence of forskolin (5 μm) plus carbachol (100 μm). Error bars: s.e.m. Stars: significantly different from control (con). Number of experiments shown in parentheses.

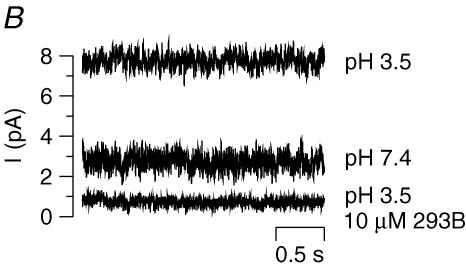

Figure 5. Effect of acidic pH on cytosolic [Ca2+] and KCNQ1/KCNE2 induced current.

A, effect of acidic extracellular pH and ionomycin (0.1 μm) on intracellular Ca2+ activity of COS cells as measured by fura-2 fluorescence (n = 10). For comparison, the peak value of ATP (100 μm, pH 7.4) is depicted. Error bars: s.e.m. Stars: significantly different from control. B, original current recordings of an outside-out patch of COS cells co-transfected with hKCNE2/hKCNQ1 (Vc = 0 mV, pipette and bath solution as described in Methods). Note the increase in current due to acidic pH and the almost complete inhibition by 293B.

Recently, it has been shown that l-α-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) activates KCNQ channels in expression systems (Zhang et al. 2003; Loussouarn et al. 2003) and gastric acid secretion (Omi et al. 2001). Here, we tested the effect of PIP2 on hKCNE2/KCNQ1 channels in COS cells. In the presence of PIP2 (5 μm) whole-cell current was enhanced significantly by 22.4 ± 26.1% (Vc = +5 mV; n = 9; P = 0.03) compared to control.

Another set of experiments aimed at investigating the whole-cell current of native parietal cells. After prestimulation with forskolin (5 μm) and carbachol (100 μm), 293B (10 μm) inhibited a K+ conductance (303 ± 98 pS pF−1 293B-inhibitable conductance; n = 6; Fig. 4C) suggesting the presence of KCNQ1 current in mouse parietal cells.

KCNE2/KCNQ1 K+ channels are activated by acidic pH

In a recent study (Grahammer et al. 2001), we have observed that the reduction of extracellular pH from 7.4 to 5.5 increases the 293B-sensitive current of hKCNE2/hKCNQ1-expressing COS cells. In order to rule out an indirect activation of KCNE2/KCNQ1 by acidic pH, e.g. via cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 4A), we performed excised outside-out patches on transfected COS cells. Reduction of external pH from 7.4 to 3.5 strongly increased K+ current which could be inhibited by 293B (10 μm). Figure 5B shows typical traces of one out of four similar experiments.

Does activation of KCNE2/KCNQ1 involve membrane targeting?

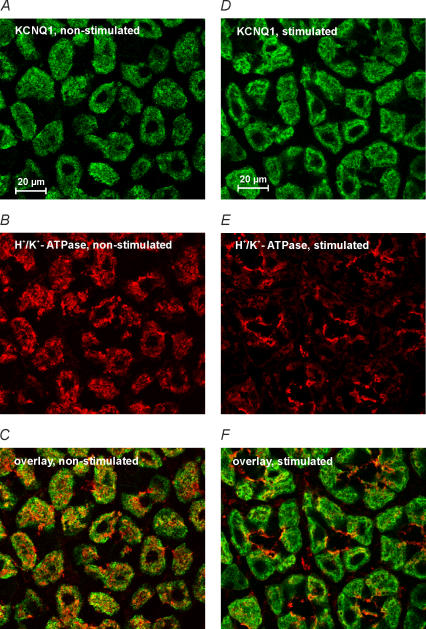

In resting parietal cells, H+,K+-ATPase is localized in intracellular vesicles which fuse with the luminal membrane upon stimulation thus allowing H+ to be pumped into the lumen. We addressed the question of whether KCNE2/KCNQ1 channels are regulated by membrane insertion and retrieval as well. Cryosections of stomach mucosa of fasted mice and of mice after the stimulation of acid secretion were co-stained for H+,K+-ATPase and KCNQ1. As expected, H+,K+-ATPase staining changed from a cytosolic distribution in non-stimulated tissue to a more pronounced localization at the apical pole of parietal cells in specimens of stimulated animals (Fig. 6). Interestingly, for KCNQ1 such targeting to the luminal pole could not be observed. Therefore, luminal KCNQ1 K+ channels and H+,K+-ATPase are probably not co-localized in the same vesicles and regulation by membrane insertion/retrieval is presumably restricted to H+,K+-ATPase.

Figure 6. Effect of parietal cell activation on the subcellular localization of KCNQ1 and H+, K+-ATPase.

Confocal images of mouse gastric mucosa: A–C non-stimulated; D–F after stimulation with pentagastrin plus histamine plus carbachol. A–C: KCNQ1 (A) partially co-localized with H+,K+-ATPase (B) in non-stimulated tissue. Overlay is shown in C. D–F: activation of acid secretion did slightly change the distribution of KCNQ1 (D) but led to a marked targeting of H+,K+-ATPase to the luminal pole of parietal cells (E). Overlay is shown in F.

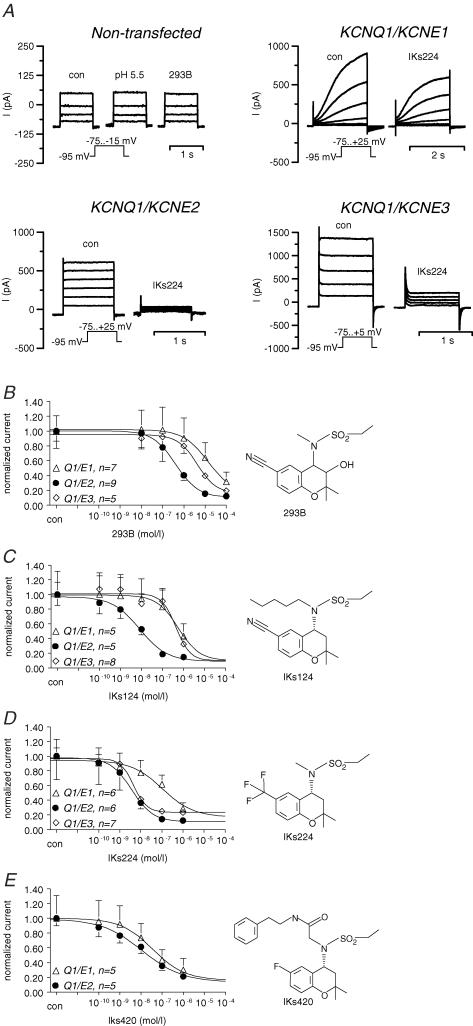

KCNE β subunits determine KCNQ1 pharmacology

We examined the effect of 293B and derivatives on whole-cell currents of COS cells expressing hKCNQ1 together with one of the subunits hKCNE1, hKCNE2 or hKCNE3 (Fig. 7). Typical current traces of non-transfected cells and cells co-transfected with KCNQ1 together with KCNE1–3 are shown in Fig. 7A. The IC50 values for KCNE1/KCNQ1, KCNE2/KCNQ1 and KCNE3/KCNQ1 were as follows: IKs224: 110 nm (E1/Q1), 4 nm (E2/Q1), 4.5 nm (E3/Q1); IKs124: 370 nm (E1/Q1), 8 nm (E2/Q1), 440 nm (E3/Q1); IKs420: 33 nm (E1/Q1), 11 nm (E2/Q1); 293B: 9800 nm (E1/Q1), 400 nm (E2/Q1), 4300 nm (E3/Q1). Among the substances tested, IKs124 was very potent in inhibiting KCNE2/KCNQ1 and it appeared to be rather specific for KCNE2/KCNQ1 (Fig. 7B–E). The inhibition of KCNQ1 was also observed at an extracellular pH of 3.5 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 7. Pharmacology of hKCNE1/hKCNQ1 (Q1/E1), hKCNE2/hKCNQ1 (Q1/E2) and hKCNE3/hKCNQ1 (Q1/E3) expressed in COS cells.

A, typical biophysical and pharmacological properties of the ‘cardiac’ KCNE1/KCNQ1 channel complex heteromeric KCNE2/KCNQ1 and KCNE3/KCNQ1 channels (Dedek & Waldegger, 2001). Currents of non-transfected cells are shown as control. Note the slow activation kinetics of KCNE1/KCNQ1 and the linear current–voltage relationship of KCNE2/KCNQ1 and KCNE3/KCNQ1. IKs224 (0.1 μm) was more effective in blocking KCNE2/KCNQ1 compared to KCNE1/KCNQ1 and KCNE3/KCNQ1 currents. For concentration–response curves, 293B (B), IKs124 (C), IKs224 (D) and IKs420 (E) were applied in rising concentrations to the bath solution. For calculations, whole-cell currents (I) at the most depolarized voltage step were normalized to control values. Error bars: s.e.m.; number of experiments are indicated in the panels.

Discussion

The acid secretion of parietal cells is mediated by the H+,K+-ATPase and thus ion channels in the luminal membrane are required, in addition, to recycle K+ and to secrete Cl−. Recently, four K+ channels (KCNJ1, KCNJ2, KCNJ10 and KCNQ1) have been observed in the luminal membrane compartment of parietal cells, where they are involved in recycling the K+ necessary for ongoing acid secretion (Grahammer et al. 2001; Dedek & Waldegger, 2001; Fujita et al. 2002; Aihara et al. 2003; Warth & Barhanin, 2003; Waldegger, 2003; Malinowska et al. 2004). However, little is known about mechanisms regulating luminal K+ channels. The present study was aimed at investigating the properties of KCNQ1 K+ channels in parietal cells.

Subunit composition of KCNQ1 in parietal cells

KCNQ1 α subunits are known to associate with small regulatory proteins of the KCNE family to form native channels (Sanguinetti et al. 1996; Barhanin et al. 1996; Schroeder et al. 2000; Tinel et al. 2000; Grunnet et al. 2002; Angelo et al. 2002). In situ hybridization and Northern blot experiments of mouse tissue suggested a coassembly of KCNE2 and KCNQ1 in gastric parietal cells (Dedek & Waldegger, 2001). In the present study we obtained similar results for human gastric mucosa by in situ hybridization. In immunofluorescence experiments on rat stomach mucosa, partial co-localization of H+, K+-ATPase and KCNE2 was observed as described for H+,K+-ATPase and KCNQ1. These results suggest that KCNQ1 and KCNE2 co-assemble in the luminal membrane compartment.

KCNE3 is also expressed in human stomach mucosa, but so far we do not know the cell type in which KCNE3 is localized. In enterocytes of small and large intestine, KCNE3/KCNQ1 is a basolateral K+ channel (Schroeder et al. 2000; Dedek & Waldegger, 2001; Warth et al. 2002). Immunofluorescence of human stomach suggested, besides localization in parietal cells, that KCNQ1 is present in the basolateral membrane of mucous-producing cells of the surface and neck regions (Grahammer et al. 2001). Therefore, KCNE3 might be the β subunit of basolateral KCNQ1 in mucous-producing cells (Grahammer et al. 2001).

Activation of KCNE2/KCNQ1 during acid secretion

Physiologically, the activation of gastric acid secretion involves cAMP and Ca2+. Here we examined the effect of cAMP and Ca2+ on KCNE2/KCNQ1-expressing COS cells. After stimulation of the cAMP pathway, KCNE2/KCNQ1 channels were strongly activated. In contrast to stimulation by ATP activating Ca2+–IP3 pathways via purinergic receptors, the effect of ionomycin-induced Ca2+ increase on KCNE2/KCNQ1 current was smaller, although the effects on cytosolic Ca2+ were in the same range. Probably, ATP activates KCNE2/KCNQ1 not only via Ca2+ but by the activation of other pathways, e.g. G-proteins, the activation of kinases or changes in phospholipid metabolism.

After stimulation of cAMP and Ca2+ pathways, the KCNQ1 blocker 293B (which blocked gastric acid secretion almost completely) inhibited a K+ conductance in native mouse parietal cells indicating the activity of KCNE2/KCNQ1 K+ channels during acid secretion. In contrast to over-expressing transfected COS cells, the inhibitory effect of 293B on native parietal cells was relatively small, because other conductances such as luminal Cl− and basolateral K+ channels were not blocked by 293B. In that respect, the effect of 293B resembled the one observed in the colon: in the colonic mucosa, the effect of 293B on whole-cell current is relatively small (Schroeder et al. 2000); however, 293B inhibits some 90% of electrogenic Cl− secretion in Ussing chamber experiments (Lohrmann et al. 1995), because no other basolateral K+ channel is able to replace KCNE3/KCNQ1 during cAMP-activated secretion.

Recently, it has been shown that the luminal K+ conductance of parietal cells is activated by phosphatidylinositol (Omi et al. 2001). Interestingly, homomeric KCNQ1 channels (Zhang et al. 2003) and KCNE1/KCNQ1 channels (Loussouarn et al. 2003) are also stimulated by phosphatidylinositol. Here, we observed a similar activation of KCNE2/KCNQ1 in COS cells suggesting that KCNE2/KCNQ1 is part of the PIP2-activated K+ conductance of parietal cell vesicles (Omi et al. 2001).

Since the luminal fluid of gastric glands is very acidic, luminal K+ channels of parietal cells have to be acid resistant. In a first series of experiments in COS cells, we have shown that KCNE2/KCNQ1 are active at low pH (Grahammer et al. 2001). These experiments were performed on intact cells so it was not clear whether low pH acts via indirect effects such as changes in intracellular [Ca2+] (Fig. 5A). In the present study we could demonstrate on excised outside-out patches the direct activation of KCNE2/KCNQ1 channels by an acidic extracellular pH of 3.5 (Fig. 5B). Since KCNQ1 alone is inhibited by acidic pH (Freeman et al. 2000) the associated KCNE2 subunit not only modulates activation kinetics and regulation but appears to mediate the pH sensitivity of the heteromeric channel. Because of this remarkable activation at pH 3.5, KCNE2/KCNQ1 is a good candidate to fulfil the requirements of luminal K+ channels of gastric parietal cells.

Localization of KCNQ1 in stimulated parietal cells

A key event during the activation of gastric acid secretion is the translocation of H+,K+-ATPase from intracellular tubulovesicles towards so-called canaliculi that invaginate from the luminal surface (an excellent overview is provided by Yao & Forte, 2003). The ultrastructural changes of parietal cells due to fusion of H+,K+-ATPase-containing vesicles with canaliculi upon stimulation led to the so-called recruitment-recycling model (Forte et al. 1977; Duman et al. 2002). We addressed the question of whether KCNQ1 is targeted to the luminal pole of parietal cells in a similar manner. In immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy, H+,K+-ATPase labelling was shifted to the luminal pole after the activation of acid secretion. Such an evident translocation could not be observed for KCNQ1. Although confocal imaging suggests differential activation/translocation mechanisms for H+,K+-ATPase and KCNQ1, we cannot rule out that both proteins partially co-localize in the same vesicles of resting parietal cells. Unfortunately, electron microscopy did not provide reliable results for KCNQ1 labelling which would have allowed the determination of the precise subcellular localization of both proteins, especially in the resting state. In conclusion, these data suggest that the activation of native KCNE2/KCNQ1 channels probably occurs mainly via cAMP- and PIP2-mediated activation of channels already located in membranes which are in contact with canaliculi.

Very recently, the importance of luminal ion channel activation for the stimulation of gastric acid secretion has been underlined by a study on genetically modified mice expressing of a mutated H+,K+-ATPase, which is permanently resident in the luminal membrane (Nguyen et al. 2004). Those mice did not exhibit an increased basal acid secretion and acid secretion could be activated by histamine as in wild-type mice. In this mouse model, cAMP-mediated activation of KCNE2/KCNQ1 channels could represent the key step to enable luminal H+ secretion.

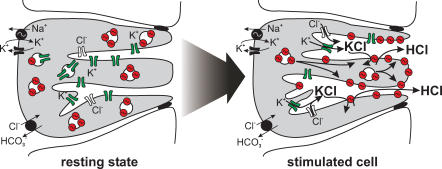

Further studies are required to test whether there is a preferential secretion of K+ (and Cl−) in the depth of canaliculi and H+–K+ exchange by H+,K+-ATPase at the luminal pole of parietal cells. Such a mechanism could serve the self protection of parietal cells in as much as high H+ gradients would be created towards the gland lumen but not at the cytosolic end of canaliculi (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Putative model of H+, K+-ATPase and K+ channel activation during gastric acid secretion.

In the resting state of the parietal cell, H+,K+-ATPase is located in so-called tubulovesicles beneath the luminal membrane and is functionally silent. At the present time, it is not known whether H+,K+-ATPase and K+ channels are located in the same tubulovesicles. Upon stimulation of gastric acid secretion, K+ channels (probably KCNE2/KCNQ1, KCNJ1, KCNJ2 and KCNJ10) are activated via cAMP and other pathways, resulting in KCl secretion. H+,K+-ATPase is predominantly targeted to the luminal pole of canaliculi, where it pumps out H+ in exchange for K+.

Subunit-specific pharmacology of KCNQ1 channels

Therapeutical use of KCNQ1 inhibitors for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease would require stomach- and subunit-specific modes of action since the blocking of KCNQ1 channels in heart, inner ear, intestinal mucosa or airways could cause adverse effects. Thus, we examined the effects of the chromanol 293B and three related substances (IKs124, IKs224 and IKs420) on COS cells co-expressing hKCNQ1 together with hKCNE1, hKCNE2 or hKCNE3. Interestingly, IKs124 had a 46-fold lower IC50 for KCNE2/KCNQ1 compared to KCNE1/KCNQ1 channels and a 55-fold lower IC50 compared to KCNE3/KCNQ1 channels. In contrast to this, IKs224 blocked KCNE2 and KCNE3 channels with an almost similar potency and was less effective on KCNE1-containing channels. Therefore, the development of subunit-specific KCNQ1 blockers allowing tissue-specific treatment could be feasible (Gerlach et al. 2001; Warth et al. 2002).

Conclusion

KCNE2 appears to assemble with KCNQ1 to form a functionally important luminal K+ channel of gastric parietal cells. The activation of this acid-activated KCNE2/KCNQ1 channel complex is induced via PIP2 and cAMP pathways but does not primarily involve translocation towards the luminal pole of parietal cells, as it is the case for H+,K+-ATPase. So far, KCNQ1 is the only putative luminal K+ channel of parietal cells for which it has been shown that its pharmacological inhibition blocks acid secretion in vivo. IKs124 could serve as a leading compound in the development of subunit-specific inhibitors of KCNE2/KCNQ1 K+ channels in parietal cells. Besides KCNQ1, other likely candidates for luminal K+ channels in parietal cells are KCNJ1, KCNJ2 and KCNJ10. Data from genetically modified mice suggest an important role for KCNQ1 and KCNJ1 in acid secretion (Lee et al. 2000); however, for the KCNJ2 and KCNJ10 knockout mice no parietal cell phenotype has yet been reported (Aihara et al. 2003). Further studies are required to elucidate whether all these K+ channels act in concert during acid secretion or whether they serve distinct functions in gastric mucosa.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert assistance of I. Tegtmeier, C. Sterner, B. Weinhold, S. Haxelmanns and M. M. Larroque, and thank Dr S. Waldegger for fruitful discussions.

References

- Abbott GW, Sesti F, Splawski I, Buck ME, Lehmann MH, Timothy KW, Keating MT, Goldstein SA. MiRP1 forms IKr potassium channels with HERG and is associated with cardiac arrhythmia. Cell. 1999;97:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80728-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aihara T, Nakamura E, Amagase K, Tomita K, Fujishita T, Furutani K, Okabe S. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:109–127. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo K, Jespersen T, Grunnet M, Nielsen MS, Klaerke DA, Olesen SP. KCNE5 induces time- and voltage-dependent modulation of the KCNQ1 current. Biophys J. 2002;83:1997–2006. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73961-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhanin J, Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Lazdunski M, Romey G. KvLQT1 and IsK (minK) proteins associate to form the IKs cardiac potassium current. Nature. 1996;384:78–80. doi: 10.1038/384078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow DC, Forte JG. Characterization of the beta-subunit of the H+-K+-ATPase using an inhibitory monoclonal antibody. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C1562–C1570. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.6.C1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedek K, Waldegger S. Colocalization of KCNQ1/KCNE channel subunits in the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442:896–902. doi: 10.1007/s004240100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman JG, Pathak NJ, Ladinsky MS, McDonald KL, Forte JG. Three-dimensional reconstruction of cytoplasmic membrane networks in parietal cells. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1251–1258. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.6.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M, Lesage F, Duprat F, Heurteaux C, Reyes R, Fosset M, Lazdunski M. A neuronal two P domain K+ channel stimulated by arachidonic acid and polyunsaturated fatty acids. EMBO J. 1998;17:3297–3308. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forte TM, Machen TE, Forte JG. Ultrastructural changes in oxyntic cells associated with secretory function: a membrane-recycling hypothesis. Gastroenterology. 1977;73:941–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman LC, Lippold JJ, Mitchell KE. Glycosylation influences gating and pH sensitivity of I(sK) J Membr Biol. 2000;177:65–79. doi: 10.1007/s002320001100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita A, Horio Y, Higashi K, Mouri T, Hata F, Takeguchi N, Kurachi Y. Specific localization of an inwardly rectifying K+ channel, Kir4.1, at the apical membrane of rat gastric parietal cells; its possible involvement in K+ recycling for the H+–K+ pump. J Physiol. 2002;540:85–92. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach U, Brendel J, Lang HJ, Paulus EF, Weidmann K, Bruggemann A, Busch AE, Suessbrich H, Bleich M, Greger R. Synthesis and activity of novel and selective I(Ks)-channel blockers. J Med Chem. 2001;44:3831–3837. doi: 10.1021/jm0109255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahammer F, Herling AW, Lang HJ, Schmitt-Gräff A, Wittekindt OH, Nitschke R, Bleich M, Barhanin J, Warth R. The cardiac K+ channel KCNQ1 is essential for gastric acid secretion. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1363–1371. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunnet M, Jespersen T, Rasmussen HB, Ljungstrom T, Jorgensen NK, Olesen SP, Klaerke DA. KCNE4 is an inhibitory subunit to the KCNQ1 channel. J Physiol. 2002;542:119–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating MT, Sanguinetti MC. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. Cell. 2001;104:569–580. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MP, Ravenel JD, Hu RJ, Lustig LR, Tomaselli G, Berger RD, Brandenburg SA, Litzi TJ, Bunton TE, Limb C, Francis H, Gorelikow M, Gu H, Washington K, Argani P, Goldenring JR, Coffey RJ, Feinberg AP. Targeted disruption of the Kvlqt1 gene causes deafness and gastric hyperplasia in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1447–1455. doi: 10.1172/JCI10897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrmann E, Burhoff I, Nitschke RB, Lang HJ, Mania D, Englert HC, Hropot M, Warth R, Rohm W, Bleich M, Greger R. A new class of inhibitors of cAMP-mediated Cl− secretion in rabbit colon, acting by the reduction of cAMP-activated K+ conductance. Pflugers Arch. 1995;429:517–530. doi: 10.1007/BF00704157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loussouarn G, Park KH, Bellocq C, Baro I, Charpentier F, Escande D. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, PIP2, controls KCNQ1/KCNE1 voltage-gated potassium channels: a functional homology between voltage-gated and inward rectifier K+ channels. EMBO J. 2003;22:5412–5421. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska DH, Sherry AM, Tewari KP, Cuppoletti J. Gastric parietal cell secretory membrane contains PKA- and acid-activated Kir2.1 K+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C495–C506. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00386.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen NV, Gleeson PA, Courtois-Coutry N, Caplan MJ, Van Driel IR. Gastric parietal cell acid secretion in mice can be regulated independently of H/K ATPase endocytosis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:145–154. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omi N, Nagao T, Urushidani T. Phosphatidylinositol is essential determinant for K+ permeability involved in gastric proton pumping. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G786–G797. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priori SG, Barhanin J, Hauer RN, Haverkamp W, Jongsma HJ, Kleber AG, McKenna WJ, Roden DM, Rudy Y, Schwartz K, Schwartz PJ, Towbin JA, Wilde A. Genetic and molecular basis of cardiac arrhythmias; impact on clinical management. Study group on molecular basis of arrhythmias of the working group on arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:174–195. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reenstra WW, Forte JG. Characterization of K+ and Cl− conductances in apical membrane vesicles from stimulated rabbit oxyntic cells. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:G850–G858. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.5.G850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, Keating MT. Coassembly of KvLQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac IKs potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BC, Waldegger S, Fehr S, Bleich M, Warth R, Greger R, Jentsch TJ. A constitutively open potassium channel formed by KCNQ1 and KCNE3. Nature. 2000;403:196–199. doi: 10.1038/35003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinel N, Diochot S, Borsotto M, Lazdunski M, Barhanin J. KCNE2 confers background current characteristics to the cardiac KCNQ1 potassium channel. EMBO J. 2000;19:6326–6330. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldegger S. Heartburn: cardiac potassium channels involved in parietal cell acid secretion. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446:143–147. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Curran ME, Splawski I, Burn TC, Millholland JM, Vanraay TJ, Shen J, Timothy KW, Vincent GM, de Jager T, Schwartz PJ, Toubin JA, Moss AJ, Atkinson DL, Landes GM, Connors TD, Keating MT. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmisa. Nature Genet. 1996;12:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth R. Potassium channels in epithelial transport. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446:505–513. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth R, Barhanin J. The multifaceted phenotype of the knockout mouse for the KCNE1 potassium channel gene. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R639–R648. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00649.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth R, Barhanin J. Function of K+ channels in the intestinal epithelium. J Membr Biol. 2003;193:67–78. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-2001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warth R, Garcia AM, Kim K, Zdebik A, Nitschke R, Bleich M, Gerlach U, Barhanin J, Kim J. The role of KCNQ1/KCNE1 K+ channels in intestine and pancreas: lessons from the KCNE1 knockout mouse. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:822–828. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0751-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolosin JM, Forte JG. Stimulation of oxyntic cell triggers K+ and Cl− conductances in apical H+-K+-ATPase membrane. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:C537–C545. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1984.246.5.C537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X, Forte JG. Cell biology of acid secretion by the parietal cell. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:103–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.072302.114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Craciun LC, Mirshahi T, Rohacs T, Lopes CM, Jin T, Logothetis DE. PIP2 activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron. 2003;37:963–975. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00125-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]