Abstract

The CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) of the marine eustigmatophycean microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana consists of an active HCO3− transport system and an internal carbonic anhydrase to facilitate accumulation and conversion of HCO3− to CO2 for photosynthetic fixation. Aqueous inlet mass spectrometry revealed that a portion of the CO2 generated within the cells leaked to the medium, resulting in a significant rise in the extracellular CO2 concentration to a level above its chemical equilibrium that was diagnostic for active HCO3− transport. The transient rise in extracellular CO2 occurred in the light and the dark and was resolved from concurrent respiratory CO2 efflux using H13CO3− stable isotope techniques. H13CO3− pump-13CO2 leak activity of the CCM was unaffected by 10 μm 3(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea, an inhibitor of chloroplast linear electron transport, although photosynthetic O2 evolution was reduced by 90%. However, low concentrations of cyanide, azide, and rotenone along with anoxia significantly reduced or abolished 13CO2 efflux in the dark and light. These results indicate that H13CO3− transport was supported by mitochondrial energy production in contrast to other algae and cyanobacteria in which it is supported by photosynthetic electron transport. This is the first report of a direct role for mitochondria in the energization and functioning of the CCM in a photosynthetic organism.

In many species of cyanobacteria and microalgae, the uptake of CO2 for photosynthesis is mediated by an energy-dependent CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM). Several key components of the system have been identified in cyanobacteria and include metabolic influx pumps that actively transport and accumulate inorganic carbon (CO2 + HCO3− = Ci), carbonic anhydrase (CA), which catalyzes the conversion of accumulated HCO3− to CO2 near the site of Rubisco, and structurally intact carboxysomes, which house the majority of the cellular complement of Rubisco and CA (Kaplan and Reinhold, 1999; So et al., 2002). Physiological and biochemical studies indicate that there are multiple transport systems for Ci that recognize and use HCO3− and CO2 as substrates (Miller et al., 1990; Espie et al., 1991). It is widely accepted that Ci transport is light dependent and that photosynthetic electron transport provides the energy required for the active transport of both HCO3− and CO2 at the plasma membrane (Kaplan and Reinhold, 1999). In the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp., there appears to be a division of labor within the photosystems in that HCO3− transport is supported by linear electron flow, whereas cyclic electron transport supplies the energy for CO2 uptake (Li and Canvin, 1998).

The CCM is more complex in eukaryotic algae because of the increased number of metabolic compartments. Species diversity in terms of the required components for the CCM and its specific mode of operation in microalgae have been extensively documented (Badger et al., 1998; Badger and Spalding, 2000). Diversity in the functional elements of the CCM include the participation (or absence thereof) of various forms of perplasmic CA (Spalding et al., 1983b; Fujiwara et al., 1990), one or more plasma membrane-localized and/or chloroplast envelope-localized, Ci transport systems (Badger and Spalding, 2000), pyrenoid-localized Rubisco (Lacoste-Royal and Gibbs, 1987), and intracellular CA localized within the pyrenoid and thylakoid membranes (Karlsson et al., 1998) and mitochondria (Eriksson et al., 1998). Early experiments using Chlamydomonas reinhardtii indicated that photosynthetic processes provided the energy for the operation of the CCM (Spalding et al., 1983a; Sultemeyer et al., 1993). The details of energy supply are yet to be fully established, however, inhibition of light-dependent Ci accumulation in isolated chloroplasts of C. reinhardtii by 3(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1-dimethylurea (DCMU) strongly suggested a role for linear electron transport in Ci transport in this organelle (Spalding, 1998; Badger and Spalding, 2000).

In marine microalgae, studies of the CCM have concentrated largely on examining the Ci species transported during photosynthesis and on the role of CA (Raven, 1997). Recent studies with the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. WH7803 and the eustigmatophyte alga Nannochloropsis spp. have, however, identified a new phenomenon associated with the operation of the CCM (Sukenik et al., 1997; Tchernov et al., 1997; Huertas et al., 2000). In these species, illumination resulted in a significant and sustained rise in the external CO2 concentration as photosynthesis proceeded, rather than the expected draw-down of the external CO2 due to active Ci transport and photosynthesis (Miller et al., 1990; Colman et al., 2002). In other words, the cells acted as point-source CO2 generators substantially elevating both the internal and external CO2 concentration above their chemical equilibrium, in what might be considered a shot-gun approach to circumventing CO2 limitation. CO2 generation required two elements in Nannochloropsis spp.: an active HCO3− transport system to accumulate intracellular Ci and an intracellular CA to convert HCO3− to CO2. It appeared that a substantial portion of the internal CO2 subsequently leaked to the surroundings, and this leakage accounted for the unexpected rise in the external concentration. Inhibition of HCO3− transport by 4,4′-diisothiocyanatolstilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) or the inhibition of intracellular CA activity by ethoxyzolamide (EZ) both prevented the rise in CO2 concentration in the surroundings and reduced the rate of photosynthesis (Huertas et al., 2000). As a consequence, the CCM of Nannochloropsis spp. may be described minimally as HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity.

We have recently discovered that the CO2 generating system in Nannochloropsis gaditana continues to function for up to 20 min in the dark. Like its counterpart in the light, the CO2 generating system was sensitive to DIDS and EZ, suggesting that the same components involved in the HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity of the CCM participated in CO2 generation in the dark. This observation seriously challenges the notion that the CCM is exclusively energized by the light-dependent photosynthetic electron transport chain. In the present work, we use mass spectrometry and stable isotope techniques to measure fluxes of 12CO2 and 13CO2 in cell suspensions of the marine microalga N. gaditana to distinguish between fluxes arising from respiratory metabolism and the HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity of the CCM in the dark and light. Flux measurements were made in the absence or presence of inhibitors of mitochondrial respiration and chloroplast linear electron transport to investigate the role of these organelles in providing energy for HCO3− transport. Our results demonstrate that HCO3− uptake in the dark and light is driven by mitochondrial respiration and, thus, identify a novel component of the CCM in this alga.

RESULTS

N. gaditana Generates CO2 in the Dark and Light

Illuminated cells of N. gaditana were allowed to reach the CO2 compensation point, and the light was switched off (Fig. 1a). The 12CO2 concentration in the medium rose to a very high level over the initial 5 min of the experiment and then gradually declined over the next 10 min. Addition of bovine CA to the reaction vessel (Fig. 1b) during any part of the time course resulted in a rapid diminution of the CO2 signal, indicating that CO2 was present in the medium at levels well above its chemical equilibrium value with HCO3−. The creation and maintenance of this chemical disequilibrium is indicative of the involvement of an energy-dependent step in this process. Such a large rise in CO2 after darkening has been observed thus far only in N. gaditana (Huertas et al., 2000). The subsequent decline in CO2 concentration would not be anticipated, however, because respiratory metabolism should contribute to a continuous, though slow, increase in the external CO2 concentration.

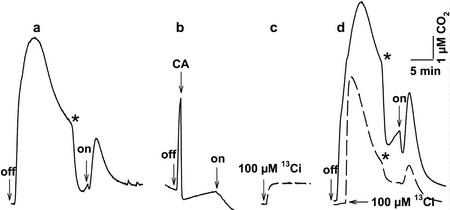

Figure 1.

Measurement of 12CO2 (———) and 13CO2 (— — —) fluxes in the dark and light. a, An illuminated (1 mmol m−2 s−1, photosynthetically active radiation) cell suspension of N. gaditana was allowed to reach the CO2 compensation point, and the light was turned off. Changes in 12CO2 concentration were followed with time, and the light was then turned on. The asterisk indicates the transition from the slow to the fast phase of 12CO2 decline. b, As in a except that bovine CA (40 μg mL−1) was added to the darkened cell suspension during the rise in 12CO2. c, K213CO3 (100 μm) was added to reaction buffer (-cells) to determine the equilibrium 13CO2 concentration at pH 8.0 and 25°C. d, As in a except that 100 μm K213CO3 was added 2 min after darkening and both 12CO2 and 13CO2 concentrations were measured over time. The time courses are superimposed for comparison.

When the light was turned on (Fig. 1a), a new transient rise in CO2 concentration was observed that was then followed by a persistent decline as photosynthesis proceeded. Addition of bovine CA during the light phase also resulted in a diminution of the CO2 signal, indicating that the CO2 concentration was above its chemical equilibrium level (data not shown; Huertas et al., 2000). A similar sustained evolution of CO2 in the light during CO2 fixation has been previously reported for N. gaditana and the marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. WH7803(Sukenik et al., 1997; Tchernov et al., 1997) and Synechococcus spp. (Badger and Andrews, 1982). In contrast to these results, other eukaryotic algae and cyanobacteria draw-down the CO2 concentration after illumination. Clearly, CO2 fluxes in N. gaditana are complex and cannot be accounted for simply by considering photosynthetic CO2 consumption in the light and respiratory CO2 production in the dark, because in several instances the net flux was opposite in direction to the major metabolic flux of CO2.

Light-Enhanced Dark Respiration (LEDR) and HCO3− Pump-CO2 Leak Activity Are Required for Dark CO2 Generation

The initial rise in CO2 concentration in the dark can be attributed to a number of different sources including the release of an internal Ci pool, a photorespiratory postillumination CO2 burst, and mitochondrial respiration. By definition, the Ci pool at the compensation point is small, and in other algal species, it was released to the medium within 1 to 2 min after darkening, resulting in only a minimal rise in the extracellular CO2 concentration. Similarly, the postillumination CO2 burst would contribute only a small portion of the CO2 because the CCM of N. gaditana suppressed the formation of photorespiratory substrates required to initiate the burst (Sukenik et al., 1997; Huertas et al., 2000). As a consequence, respiratory processes would be expected to be a major source of the CO2 appearing in the medium. N. gaditana is one of a number of plant and algal species that display a LEDR (Xue et al., 1996; Hoefnagel et al., 1998), where the respiration rate immediately after a period of photosynthesis is substantially higher than the steady-state rate. Under our conditions, LEDR measured immediately after darkening (O2 uptake) was on average 2.7-fold higher than the steady-state respiration rate measured 20 min after darkening (e.g. Fig. 2). The rate of LEDR gradually declined to the steady-state over a period of 5 to 6 min. Thus, the period of LEDR (O2 uptake) was clearly associated with the postillumination period of maximum CO2 release (Fig. 2), indicating that they are linked, probably through mitochondrial respiration. We have recently discovered that the HCO3− transport system in N. gaditana remained active in the dark (Huertas et al., 2000), and it may, therefore, also contribute to the rise in CO2 through its HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity.

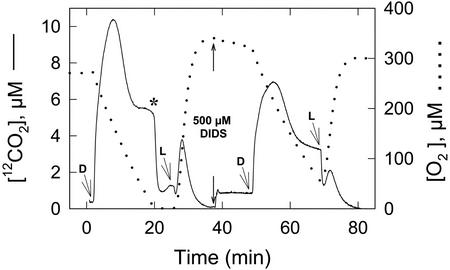

Figure 2.

Measurement of 12CO2 (———) and 16O2 (. . . . .) fluxes in a cell suspension of N. gaditana in the light (L) and dark (D) and in the absence and presence of the HCO3− transport inhibitor DIDS (500 μm). The experimental procedure was essentially the same as that for Figure 1. The asterisk indicates the transition from the slow to the fast phase of 12CO2 decline.

To follow CO2 fluxes between the medium and the cells independent of respiratory 12CO2 production, we added 100 μm 13Ci to the cell suspension 2 min after turning the light off (Fig. 1, c and d). In the absence of cells, the 13CO2 concentration in the medium rose to the expected equilibrium level and then remained constant (Fig. 1c). In the presence of cells, the 13CO2 concentration also increased with time (Fig. 1d) but to a level 5.6-fold the equilibrium value and then declined gradually over time in parallel with the 12CO2 signal. Thus, the 13CO2 signal displayed the same dynamics as the 12CO2 signal, but in this case, the rise in 13CO2 cannot be attributed to LEDR or steady-state respiration because mitochondrial substrates were not enriched with 13C. Participation of H12CO3− in this energy-driven pump-leak activity would also be expected to occur because it is the natural substrate for the transporter. The rise in CO2 concentration may also be due to a cellular acidification of the medium. However, measurement of extracellular pH indicated that this parameter remained constant during the experiments (data not shown). As a consequence, the unusually large rise in 12CO2 concentration in the dark (Fig. 1a) can be attributed to two superimposed processes. First, LEDR-generated CO2, which was rapidly released to the medium, and some of it was hydrated to form HCO3−. Second, this HCO3− then served as substrate for the HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity in the dark resulting in a further increase in CO2 efflux. The combined processes of CO2 formation occurred at a rate faster than the uncatalyzed conversion of CO2 to HCO3− in the medium as evidenced by the rapid diminution in CO2 concentration when CA was added (Fig. 1b). In the light, similar processes occurred that accounted for the initial rise in CO2 upon illumination. The rise was considerably smaller, however, because Rubisco-mediated fixation consumed a portion of the CO2. Both the 12CO2 and 13CO2 signals ultimately declined to the CO2 compensation concentration because the Ci was consumed in photosynthesis (Fig. 1d).

Contribution of HCO3− Transport

To estimate the relative contributions of respiration and the HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity to the rise in CO2 concentration, experiments were conducted in the absence and presence of the HCO3− transport inhibitor DIDS (Fig. 2). The addition of 500 μm DIDS to illuminated cells at the CO2 compensation point significantly reduced the level of CO2 efflux once the cells were darkened. However, DIDS only had a small, negative effect (10%) on the rate of LEDR dark O2 consumption, indicating that the major effect of DIDS was on the HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity. At the DIDS concentration used, HCO3− transport was inhibited by about 90% (Huertas et al., 2000). Using the difference in peak heights in the dark as an estimate of activity (e.g. Fig. 2), HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity contributed approximately 40% to 50% to the total rise in CO2. Illumination of the cell suspension resulted in a rapid rise in extracellular CO2 concentration, which was greatly reduced in cells treated with the HCO3− transport inhibitor (Fig. 2), indicating that DIDS-sensitive HCO3− transport activity was essential for the rise in CO2 in the light and in the dark. Thus, the rise in 13CO2 concentration above the equilibrium level was diagnostic for HCO3− transport activity in N. gaditana.

Oxygen Is Required for HCO3− Pump-CO2 Leak Activity in the Dark

The decline in CO2 concentration in the dark often displayed two distinct phases, an initial slow phase followed by a second and more rapid rate of disappearance (e.g. Figs. 1a and 2, *). The accelerated phase of CO2 disappearance was also observed in the 13CO2 signal (Fig. 1d, *) and its onset corresponded with the approach to anaerobic conditions in the medium, brought about by respiratory O2 consumption (Fig. 2). Because the 13CO2 signal solely reflects HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity, this observation suggests a dependence of a component of the pump-leak activity on O2 availability. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effect of O2 concentration on the magnitude of CO2 efflux (Fig. 3). The O2 concentration in the medium was initially set by gassing with a stream of N2, or by the addition of dithionite to achieve zero O2. In the absence of O2, darkening of a cell suspension at the CO2 compensation point resulted in a very small rise in 12CO2, consistent with the suggestion that O2-dependent LEDR was responsible for part of the large rise in CO2 concentration in the dark. The addition of 100 μm 13Ci, 2 min after darkening, resulted in a rise in 13CO2 concentration only to the expected equilibrium level (Fig. 3a). In either case, illumination did not result in a rise in the CO2 signals, as observed in the control (Fig. 1d, 230 μm O2). As the O2 concentration was increased, the 13CO2 concentration also increased progressively in the dark, although the absolute amount of 13Ci added was the same in each case (Figs. 3, b–d, and 1, c and d). These data support the concept that the pump-leak activity associated with HCO3− transport required O2. The 12CO2 concentration also rose progressively due to combined mitochondrial respiration and HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity. The rise in CO2 concentration expected upon illumination was also restored with increasing O2 concentration (Figs. 3, a–d, and 1c).

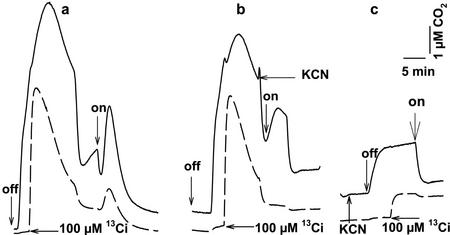

Figure 3.

Measurement of 12CO2 (———) and 13CO2 (— — —) fluxes in the dark and light in the presence of 0 (a), 1.5 (b), 5.6 (c), and 130 (d) μm O2. The plots obtained at 230 μm O2 are shown in Figure 1d. The time courses are superimposed for comparison. The experimental procedure was essentially the same as that for Figure 1; off, light turned off; on, light turned on.

Mitochondrial Respiration Energizes HCO3− Transport

The occurrence of HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity in the dark and its dependence on O2 suggested that mitochondrial respiration may be involved in energizing a component of that system. The most likely candidate is HCO3− transport because CA is a freely reversible enzyme, whereas the uptake of HCO3− would be against its electrochemical potential. To assess mitochondrial involvement, CO2 flux experiments were carried out in the presence of various inhibitors of respiration (Fig. 4; Table I). The addition of 250 μm KCN to cell suspensions during the dark CO2 efflux phase mimicked the effect of anoxia and resulted in a rapid decline in both 12CO2 and 13CO2 concentrations (Fig. 4b). Upon illumination, the efflux of 13CO2 was abolished and that of 12CO2 was markedly reduced. Inclusion of KCN in the cell suspension at the CO2 compensation point in the light resulted in a significant inhibition of 12CO2 efflux after darkening (Fig. 4c) and a 82% decrease in O2 consumption (data not shown), confirming inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. Inhibition of HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity was also evident because the addition of 100 μm 13Ci resulted in a rise in 13CO2 only to its equilibrium level. The efflux of both 12CO2 and 13CO2 was abolished during a subsequent dark-light transition. Concentrations of KCN as low as 25 μm were also effective in inhibiting CO2 efflux in the dark and in the light (Table I), suggesting a requirement for mitochondrial complex IV in HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity. Consistent with this hypothesis was the observation that NaN3, another inhibitor of complex IV, inhibited 12CO2 and 13CO2 efflux in the dark and light (Table I) and could also mimic the effect of anoxia (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Measurement of 12CO2 (———) and 13CO2 (— — —) fluxes in the dark and light in the absence (a; control) and presence (b and c) of 250 μm KCN. KCN was added during the slow decline in CO2 (b) or 2 min before darkening (c). The time courses are superimposed for comparison. The experimental procedure was essentially the same as that for Figure 1; off, lights turned off; on, lights turned on.

Table I.

Effect of inhibitors on 13CO2 efflux

| Inhibitor | 13CO2 Efflux: Dark | 13CO2 Efflux: Light |

|---|---|---|

| % Control | ||

| Controla | 100 | 100 |

| 25 μm KCN | 0 | 0 |

| 100 μm NaN3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 mm NEM | 60 | 0 |

| 500 μm Rotenone | 60 | 20 |

| 50 μm DCMU | 86 | 0 |

Effect of inhibitors on CO2 efflux was calculated as a percentage of the 13CO2 peak height of the treatment versus control using data from experiments similar to those in Fig. 4. Data are the average of three determinations ± 10%.

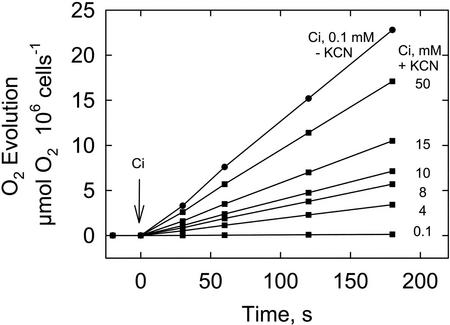

In the light, KCN may also inhibit photosynthetic electron transport directly at plastocyanin and lead to the inhibition of CO2 fixation and O2 evolution. At an external Ci concentration (0.1 mm) just sufficient to saturate photosynthesis (Huertas and Lubian, 1998), 250 μm KCN abolished O2 evolution (Fig. 5). However, increasing the external Ci to 50 mm resulted in a restoration of the photosynthetic rate to 75% of the control rate. Although KCN has a clear effect on photosynthesis, these results also indicate that the ability of the photosynthetic electron transport system to supply energy to the Calvin cycle remained largely functional and that it was the availability of Ci that was the limiting factor, consistent with an impairment of the CCM not directly related to chloroplast energy supply.

Figure 5.

Effect of 250 μm KCN on the time course of photosynthetic O2 evolution in the presence of various levels of external Ci (▪). For comparison, O2 evolution in the absence of KCN at 0.1 mm Ci (●) is also shown.

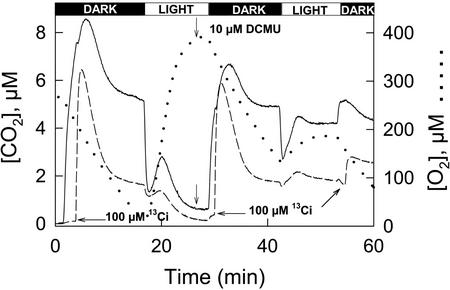

The results obtained with KCN and NaN3 were in marked contrast to those observed with DCMU, an inhibitor of chloroplast linear electron transport (Fig. 6). At 10 μm, the rise in 13CO2 was unaffected by the inhibitor in the dark or the light, indicating that the HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity could be sustained when the energy supply from photosynthetic linear electron transport was restricted. As anticipated, photosynthetic O2 evolution was strongly inhibited (6.4-fold), indicating that DCMU effectively blocked linear electron transport in N. gaditana. At 5 times the DCMU concentration (Table I), 13CO2 efflux in the dark occurred at 86% of the control level, but 13CO2 efflux in the light was abolished, indicating that chloroplast energy supply may also contribute to some extent in the pump-leak activity (Table I).

Figure 6.

Measurement of 12CO2 (———), 13CO2 (— — —), and 16O2 (. . . . .) fluxes in the dark and light in the absence and presence of 10 μm DCMU. The time courses are superimposed for comparison. The experimental procedure was essentially the same as that for Figure 1.

DCMU reduced 12CO2 efflux in the dark, but had no effect on 13CO2 efflux (Fig. 6) or on the steady-state rate of O2 uptake. The effect of DCMU on LEDR-dependent 12CO2 efflux was likely indirect and the result of a decreased supply of oxidizable substrate to the mitochondria from the chloroplasts, leading to less CO2 production and ultimately to reduced availability of HCO3− for the pump-leak activity. This possibility seems reasonable because Xue et al. (1996) have shown that LEDR was substantially, but indirectly, reduced by DCMU in C. reinhardtii.

The effects of two additional inhibitors of mitochondrial energy metabolism on 13CO2 efflux were also examined (Table I). The respiratory electron transport inhibitor rotenone, which blocks complex I, reduced 13CO2 efflux in the dark and the light by 40% and 80%, respectively. The transport inhibitor N-ethylmaleimide, which prevents ATP export from the mitochondria, reduced 13CO2 efflux to 60% of the control level in the dark and abolished it in the light. With time (> 45 min), NEM ultimately reduced dark efflux to zero (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

N. gaditana generated CO2 internally in the light and dark, which raised the extracellular CO2 concentration to levels well above its equilibrium with HCO3−. CO2 generation was associated, in part, with HCO3− transport and intracellular CA activity (Sukenik et al., 1997; Tchernov et al., 1997; Huertas et al., 2000). This HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity was resolved from respiratory 12CO2 release by using 13Ci (H13CO3−) as the substrate for the HCO3− transporter and monitoring the rise in 13CO2 in the medium.13CO2 concentrations above the measured equilibrium value were diagnostic for HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity (Fig. 1).

Mitochondrial Energization of the CCM

The locations of the internal sites of CO2 generation are not known other than that they coincide with sites where CA is located (Huertas et al., 2000). Net diffusion of CO2 away from these sites would occur randomly, following the chemical potential between the cells and the medium. As a consequence, high levels of internal CO2 would be distributed more or less evenly throughout the cells and would be dependent on HCO3− transport. Minimally, the internal CO2 concentration would be expected to be equal to the highest extracellular CO2 concentration observed. In the light, HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity would function as a rudimentary CCM increasing the CO2 concentration in the chloroplast (and other compartments), thereby facilitating high rates of CO2 fixation and suppressing photorespiration. N. gaditana lacks CO2 transport capability, extracellular CA, and pyrenoids (Santos and Leedale, 1995; Huertas et al., 2000), features that in other algae play an important role in the efficient and refined operation of the CCM.(Spalding, 1998; Badger and Spalding, 2000). It is this unique set of circumstances in N. gaditana that allow us to detect HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity in this organism by mass spectrometry.

HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity in the light and dark was inhibited by DIDS (Fig. 2), by EZ (Huertas et al., 2000), and by anoxia (Fig. 3). The common effect of these very different treatments on reducing CO2 generation indicated that the same biochemical components mediated HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity in the light and dark. Thus, information obtained from experiments in the dark is relevant in interpreting the results of the experiment in the light and vice versa. The O2 requirement of active HCO3− transport (Fig. 3) and its occurrence in the dark was inconsistent with light being the sole or primary energy source to drive this process. Inhibitors of respiration such as KCN, NEM, and others (Table I) reduced or completely inhibited HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity in the light and dark, consistent with a requirement for mitochondrial energy supply in the process. A primary role for light in energizing HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity (CCM) was further challenged by the observation that low concentrations of DCMU had little effect on 13CO2 efflux, but significantly reduced the photosynthetic rate. Energy supply from the mitochondrion, therefore, was critical to HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity, whereas energy from chloroplast linear electron transport was not. We cannot, however, completely exclude a role for light in HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity because high levels of DCMU blocked 13CO2 efflux in the light, but not in the dark. Thus, complex interactions between chloroplasts and mitochondria may also be associated with the process.

In other algae and cyanobacteria, active Ci transport rapidly ceases after darkening, reflecting a requirement for photosynthetically derived energy to fuel Ci accumulation (Kaplan and Reinhold, 1999; Badger and Spalding, 2000). In N. gaditana, HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity continues for at least 20 min in the dark before it stops. Thus, regulation of HCO3− transport by chloroplast energy supply seems unlikely. Restoration of dark HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity can be achieved by briefly (15–45 s) interrupting the dark phase with white light (Huertas et al., 2000). Thus, light may activate, but not energize, HCO3− transport. The continuation of HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity in the dark may, therefore, reflect a rather prolonged deactivation process that is more in tune with the gradual decrease in light during the natural day-night cycle than with the abrupt light-dark transition of our experiments.

One hypothesis that can account for the experimental data is that mitochondria-derived ATP is exported to the cytoplasm where it is used to drive, either directly on indirectly, a plasma membrane-localized active HCO3− transport system in the dark and light. The accumulated HCO3− is converted by a thermodynamically reversible CA to CO2 resulting in a high level within the cell and a rise in the external CO2 concentration. In the light, the effect is to concentrate CO2 in the chloroplast and to provide saturating levels of substrate for Rubisco. In the dark, LEDR releases CO2 to the medium, some of which is converted nonenzymatically to HCO3−. This HCO3− serves as the substrate for the HCO3− pump, and the resulting leakage of CO2 is superimposed upon the respiratory efflux. As LEDR diminishes with time, the rate of CO2 production declines, but HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity and the uncatalyzed conversion of CO2 to HCO3− continue with the net result being a decline in CO2 in the medium. This decline corresponds to the slow decline phase seen in the time course experiments (e.g. Figs. 1a and 2). When respiration depletes the available O2, oxidative ATP and CO2 production stop, causing a cessation in CO2 release to the medium and in HCO3− pump-CO2 leak activity. But conversion of CO2 to HCO3− in the medium continues, causing a further decrease in CO2 concentration that corresponds to the second, more-rapid phase in the CO2 decline curve.

At present, we cannot rule out involvement of a chloroplast-localized HCO3− transport system powered by mitochondria-derived ATP. However, either the ATP-binding site of the transporter would need to be oriented toward the cytosol or an import of mitochondria-derived ATP to the chloroplast would have to occur (Neuhaus and Wagner, 2000).

In the light, it is also possible that a complex shuttle of reductant from the chloroplast to the mitochondria may also contribute to ATP generation in the mitochondrion, which is used to transport HCO3−. This situation could explain the inhibition by high concentrations of DCMU of 13CO2 efflux in the light.

The association of active HCO3− transport with mitochondrial energy supply and the operation of the CCM has not been observed before. However, a role for mitochondria in the acclimation of the green algal C. reinhardtii to CO2-limiting growth conditions has been proposed, based on the observations that specific mitochondrial CAs were induced upon transfer to a low-CO2 environment and the relocation of mitochondria from central region of the cells to the periphery (Geraghty and Spalding, 1996; Eriksson et al., 1998). Participation of mitochondria in the CCM in other species may be masked by the presence of external CA, which would prevent the rise in external CO2 concentration, or by active CO2 transport, which would rapidly recycle CO2 that leaked from the cells (Espie et al., 1991). New experimental approaches will be needed to detect mitochondrial involvement in the CCM in these species and to determine whether this phenomenon is widespread. The dependence of HCO3− uptake on mitochondria energy supply may well be a primitive characteristic of algae and confined to a few species. The genus Nannochloropsis is a member of the class Eustigmatophyceae within the division Heterkonta and is considered to be one of its most primitive members (Whatley, 1995), based on the lack several photosynthetic pigments found in other members of the division (Hoek et al., 1995). Intracellular structures of eustigmatophycean algae indicate that they may have arisen by a secondary endosymbiosis where a eukaryotic alga was engulfed by a phagotrophic oomycete. This may explain the features of Nannochloropsis spp. in that the oomycete host may have had a constitutive HCO3− transporter, but is unlikely to have had either an external CA or an active transport of CO2 to facilitate Ci acquisition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organism and Growth

The unicellular marine microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana was grown at 20°C in artificial seawater (Sigma, St. Louis) supplemented with F/2 medium (Guillard and Ryther, 1962) and bubbled with air (0.035% [v/v] CO2) at a rate of 60 mL min−1 (Huertas et al., 2000). Cultures were continuously illuminated at a photon flux density of 75 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 provided by a combination of cool-white and Gro-lux fluorescent lamps. Cells were maintained in exponential growth phase by daily dilution.

Experimental Conditions

Cells were harvested by centrifugation (2,800g, 10 min), washed twice with and resuspended in a Ci-free medium containing 450 mm NaCl, 40 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl, 10 mm Na2SO4, and 5 mm CaCl2, and buffered at pH 8.0 with 25 mm TRIZMA-Base. The medium was depleted of Ci by gassing with N2. The cell suspension (6 mL) was placed in a glass reaction vessel at 25°C and 1 mmol quanta m−2 s−1 light (photosynthetically active radiation) and was allowed to fix residual Ci in the medium until the CO2 compensation point was reached. The final cell density was 2 × 108 cells mL−1 and corresponded to 30 μg chlorophyll a mL−1.

Mass Spectrometry

Washed cell suspensions (6 mL) were transferred to a glass reaction vessel containing a magnetic stirrer, and the chamber was closed with a plexiglass stopper leaving no head space. Gases and treatment solutions were introduced into the chamber through a capillary bore in the stopper. The reaction chamber was connected to the ion source of a magnetic sector mass spectrometer (model MM 14–80 SC, VG Gas Analysis, Middlewich, UK) by an inlet covered with a dimethyl silicone membrane that allowed dissolved gases to pass freely but not ions like HCO3− (Espie et al., 1991). The illuminated cells were allowed to consume residual Ci before experiments commenced and then were darkened and treated with inhibitors, if necessary. When used, 13Ci was supplied to the cells from a stock solution of K213CO3 (300 mm). Concentrations of 16O2, 12CO2, and 13CO2 (m/z = 32, 44, and 45, respectively) in cell suspensions were measured simultaneously. The mass spectrometer was calibrated for O2 and CO2 as described previously (Espie et al., 1991). Rates of O2 evolution or consumption were derived from the slopes of the m/z = 32 signal. In some experiments, net photosynthetic O2 evolution was measured using a temperature-controlled Clarke-type electrode (Hansatech, King's Lynn, UK; Huertas et al., 2000).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Harold Weger for providing detailed, critical comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (grants to B.C. and G.S.E.) and by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Spain (Postdoctoral Fellowship to I.E.H.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.004598.

LITERATURE CITED

- Badger MR, Andrews TJ. Photosynthesis and inorganic carbon usage by the marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. Plant Physiol. 1982;70:517–523. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.2.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Andrews TJ, Whitney SM, Ludwig M, Yellowlees DC, Leggat W, Price GD. The diversity and coevolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids, and chloroplast-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in algae. Can J Bot. 1998;76:1052–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Spalding MH. CO2 acquisition, concentration and fixation in cyanobacteria and algae. In: Leegood RC, Sharkey TD, von Caemmerer S, editors. Photosynthesis: Physiology and Metabolism. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. pp. 369–397. [Google Scholar]

- Colman B, Huertas IE, Bhatti S, Dason JS. The diversity of inorganic carbon acquisition mechanisms in eukaryotic algae. Funct Plant Biol. 2002;29:261–270. doi: 10.1071/PP01184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson M, Villand P, Gardestrom P, Samuelsson G. Induction and regulation of expression of a low-CO2-induced mitochondrial carbonic anhydrase in Chlamydomonase reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:637–641. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie GS, Miller AG, Canvin DT. High affinity transport of CO2 in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:943–953. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.3.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara S, Fukuzawa H, Tachiki A, Miyachi S. Structure and differential expression of two genes encoding carbonic anhydrase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9779–9783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty AM, Spalding MH. Molecular and structural changes in Chlamydomonas under limiting CO2. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:1339–1347. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillard RRL, Ryther JH. Studies on marine phytoplantonic diatoms: I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt and Denotula confervaceae (cleve) Gran. Can J Microbiol. 1962;8:229–239. doi: 10.1139/m62-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoefnagel MHN, Atkin OK, Wiskich JT. Interdependence between chloroplasts and mitochondria in the light and the dark. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1998;1366:235–255. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek CVD, Mann DG, Jahns MH. Algae: An Introduction to Phycology. Toronto: Cambridge Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas E, Lubian LM. Comparative study of dissolved inorganic carbon utilization and photosynthesis responses in Nannochloris (Chlorophyceae) and Nannochloropsis (Eustigmatophyceae) species. Can J Bot. 1998;76:1104–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Huertas IE, Espie GS, Colman B, Lubian LM. Light-dependent bicarbonate uptake and CO2 efflux in the marine microalga Nannochloropsis gaditana. Planta. 2000;211:43–49. doi: 10.1007/s004250000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A, Reinhold L. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in photosynthetic microorganisms. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:539–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J, Clarke AK, Chen Z-Y, Hugghins SY, Husic HD, Moroney JV, Samuelsson G. A novel μ-type carbonic anhydrase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is required for growth in ambient air. EMBO J. 1998;17:1208–1216. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacoste-Royal G, Gibbs SP. Immunocytochemical localization of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase in the pyrenoid and thylakoid region of the chloroplast of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 1987;83:602–606. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.3.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QL, Canvin DT. Energy sources for HCO3− and CO2 transport in air-grown cells of Synechococcus UTEX 625. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:1125–1132. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.3.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AG, Espie GS, Canvin DT. Physiological aspects of CO2 and HCO3− transport by cyanobacteria: a review. Can J Bot. 1990;68:1291–1302. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus HE, Wagner R. Solute pores, ion channels and metabolite transporters in the outer and inner envelop membranes of higher plant plastids. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2000;1465:307–323. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. Inorganic carbon acquisition by marine autotrophs. Adv Bot Res. 1997;27:84–209. [Google Scholar]

- Santos LMA, Leedale GF. Some notes on the ultrastructure of small azoosporic members of the algal class Eustigmatophyceae. Nova Hedwigia. 1995;60:219–225. [Google Scholar]

- So AKC, John-McKay ME, Espie GS. Characterization of a mutant lacking carboxysomal carbonic anhydrase from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803. Planta. 2002;214:456–467. doi: 10.1007/s004250100638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding MH. CO2 acquisition: acclimation to changing carbon availability. In: Rochaix JD, Glodschmidt-Cleront M, Merchant S, editors. The Molecular Biology of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria in Chlamydomonas. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 529–547. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding MH, Critchley C, Govindjee, Ogren WL. Influence of carbon dioxide concentration during growth on fluorescence induction characteristics of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Photosynth Res. 1983a;5:169–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00028529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spalding MH, Spreitzer RJ, Ogren WL. Carbonic anhydrase-deficient mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii requires elevated carbon dioxide concentration for photoautophic growth. Plant Physiol. 1983b;73:268–272. doi: 10.1104/pp.73.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukenik A, Tchernov D, Kaplan A, Huertas E, Lubian LM, Livne A. Uptake, efflux, and photosynthetic utilization of inorganic carbon by the marine eustigmatophyte Nannochloropsis sp. J Phycol. 1997;33:969–974. [Google Scholar]

- Sultemeyer D, Biehler K, Fock H. Evidence for the contribution of pseudocyclic photophosphorylation to the energy requirement of the mechanism for concentrating inorganic carbon in Chlamydomonas. Planta. 1993;189:235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Tchernov D, Hassidim M, Luz B, Sukenik A, Reinhold L, Kaplan A. Sustained net CO2 evolution during photosynthesis by marine microorganisms. Curr Biol. 1997;7:723–728. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00330-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whatley JM. Chromophyte chloroplasts: a polyphyletic origin? In: Green JC, Leadbeater BSC, Diver WL, editors. The Chromophyte Algae: Problems and Perspectives. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1995. pp. 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Xue X, Gauthier DA, Turpin DH, Weger HG. Interactions between photosynthesis and respiration in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:1005–1014. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.3.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]