Abstract

Arabinoxylan arabinosyltransferase (AX-AraT) activity was investigated using microsomes and Golgi vesicles isolated from wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings. Incubation of microsomes with UDP-[14C]-β-l-arabinopyranose resulted in incorporation of radioactivity into two different products, although most of the radioactivity was present in xylose (Xyl), indicating a high degree of UDP-arabinose (Ara) epimerization. In isolated Golgi vesicles, the epimerization was negligible, and incubation with UDP-[14C]Ara resulted in formation of a product that could be solubilized with proteinase K. In contrast, when Golgi vesicles were incubated with UDP-[14C]Ara in the presence of unlabeled UDP-Xyl, the product obtained could be solubilized with xylanase, whereas proteinase K had no effect. Thus, the AX-AraT is dependent on the synthesis of unsubstituted xylan acting as acceptor. Further analysis of the radiolabeled product formed in the presence of unlabeled UDP-Xyl revealed that it had an apparent molecular mass of approximately 500 kD. Furthermore, the total incorporation of [14C]Ara was dependent on the time of incubation and the amount of Golgi protein used. AX-AraT activity had a pH optimum at 6, and required the presence of divalent cations, Mn2+ being the most efficient. In the absence of UDP-Xyl, a single arabinosylated protein with an apparent molecular mass of 40 kD was radiolabeled. The [14C]Ara labeling became reversible by adding unlabeled UDP-Xyl to the reaction medium. The possible role of this protein in arabinoxylan biosynthesis is discussed.

Plant cells are surrounded by an extracellular matrix known as the cell wall, which plays an important role in development, defense against pathogen attack, and mechanical resistance. The cell wall is composed mainly of polysaccharides, which can be divided in cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin. The synthesis of these polymers takes place in different subcellular compartments. Cellulose and callose are made at the plasma membrane, whereas other hemicelluloses and pectin are believed to be synthesized in the Golgi apparatus (Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993).

Xylans are common polysaccharides in plant cell walls, particularly in secondary walls where they are deposited as the major noncellulosic polysaccharide. Xylans consist of a backbone of (1→4)-linked β-xylosyl residues. About 10% of the Xyl residues typically have single residues of 4-O-methyl-GlcUA and/or GlcUA attached, usually through α-(1→2) linkages. The xylosyl residues may also be substituted with short side chains containing l-Ara, Gal, and Xyl, and they may be acetylated at C-2 and/or C-3. In type II walls, which are present in grasses and some related plants, xylans are also the major noncellulosic polysaccharides in the primary walls. The xylans in type II walls have abundant α-l-arabinofuranosyl side chains attached through (1→3) and (1→2) linkages and have only a small amount of glucuronosyl side chains (Aspinall, 1980; McNeil et al., 1984). This type of xylan is known as arabinoxylan and may have a role in the cross-linking of cellulose microfibrils and may thereby regulate cell expansion and strengthen the wall (Gibeaut and Carpita, 1991; Carpita, 1996). In the endosperms of grasses, arabinoxylans are also abundant and their properties are important for the functionality of flour (Cleemput et al., 1997) and the nutritional value of animal feed (Bedford, 1995).

Heteropolysaccharide biosynthesis can be divided into four steps: chain or backbone initiation, elongation, side chain addition, and termination and extracellular deposition (Waldron and Brett, 1985; Iiyama et al., 1993). Our understanding of these different steps in biosynthesis is still very incomplete. The main enzymes responsible for heteropolysaccharide biosynthesis are glycosyltransferases, but only very few genes for these have been identified. Notable exceptions include the genes encoding a galactomannan galactosyltransferase from legume seeds (Edwards et al., 1999) and a xyloglucan fucosyltransfease (Perrin et al., 1999). Both of these enzymes are responsible for adding single, terminal residues to a polysaccharide backbone. The enzymes responsible for synthesizing the backbone of xylans are not known. The backbone-synthesizing enzymes may belong to the cellulose synthase-like proteins, but this assumption may be false as it is now known that callose synthase does not resemble cellulose synthase (Hong et al., 2001).

The biosynthesis of (1→4)-linked β-xylosyl backbones in xylans is catalyzed by β-1,4-xylosyltransferase. This enzyme has been investigated in a number of plants by different groups (e.g. Bailey and Hassid, 1966; Odzuck and Kauss, 1972; Baydoun et al., 1989; Gibeaut and Carpita, 1990), and we have recently reported the characterization of β-1,4-xylosyltransferase activity from microsomal membranes isolated from wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings (Porchia and Scheller, 2000). The addition of side chains to xylans has been less investigated and little is known about the way in which the different glycosyltransferases interact to form the complete polysaccharide. A study of glucuronosyltransferase has shown an interaction with xylosyltransferase (Baydoun et al., 1989). The incorporation of arabinosyl groups into (arabino) xylans remains to be explored. Although l-Ara is a common monosaccharide in plant polysaccharides and glycoproteins, there are very few reports of the arabinosyltransferases involved in polysaccharide synthesis, and no l-arabinosyltransferase has yet been identified in any organism. The difficulty and expense in obtaining the UDP-β-l-arabinopyranose substrate are probably major reasons for the relatively few investigations of arabinosyltransferases. Arabinosyltransferase has been investigated in French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), but the main polysaccharide product was arabinan rather than xylan (Odzuck and Kauss, 1972; Bolwell and Northcote, 1981, 1983a, 1983b). Also, these studies have shown that arabinosylated protein was sometimes formed (Bolwell, 1986). The partial purification of arabinan arabinosyltransferase from Golgi membranes isolated from French bean has been reported, but final identification of the enzyme was not achieved (Rodgers and Bolwell, 1992).

This work is the first to report the presence of arabinoxylan arabinosyltransferase (AX-AraT) in microsomal and Golgi membranes isolated from wheat seedlings. In addition, we present the characterization of the enzyme activity and its product. Furthermore, we demonstrate the presence of an arabinosylated protein and we discuss the possibility that this protein could participate in arabinoxylan biosynthesis.

RESULTS

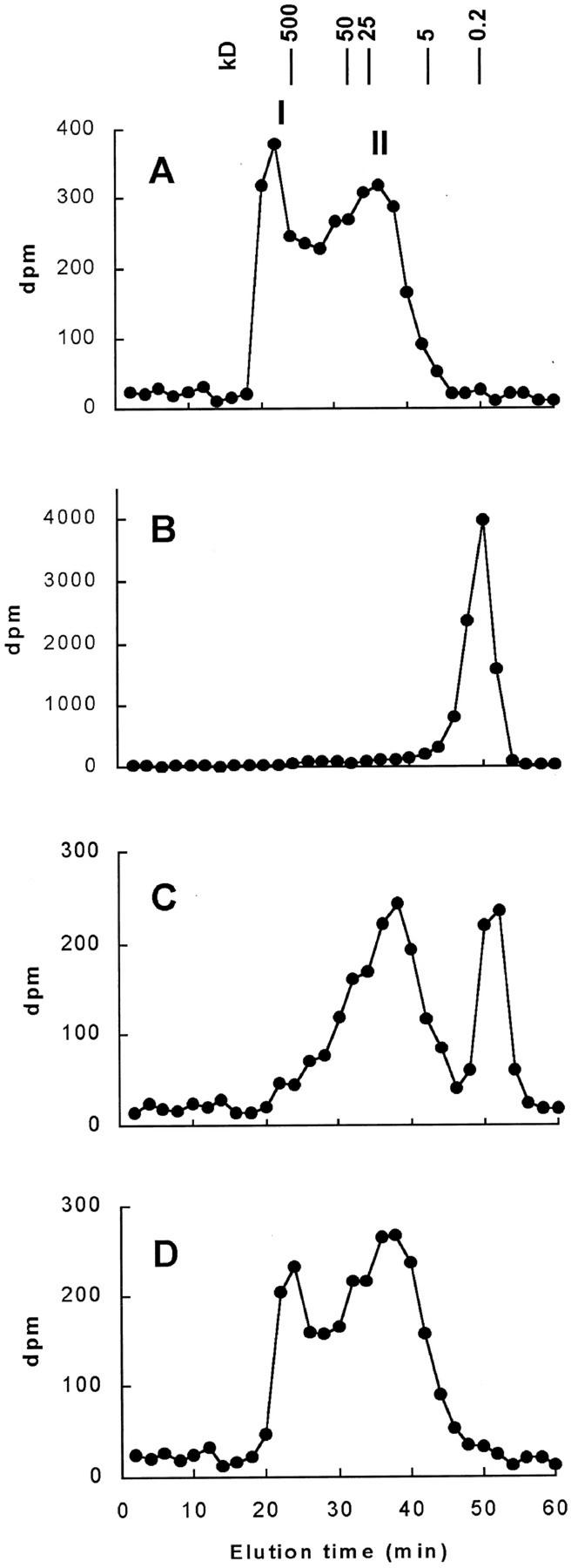

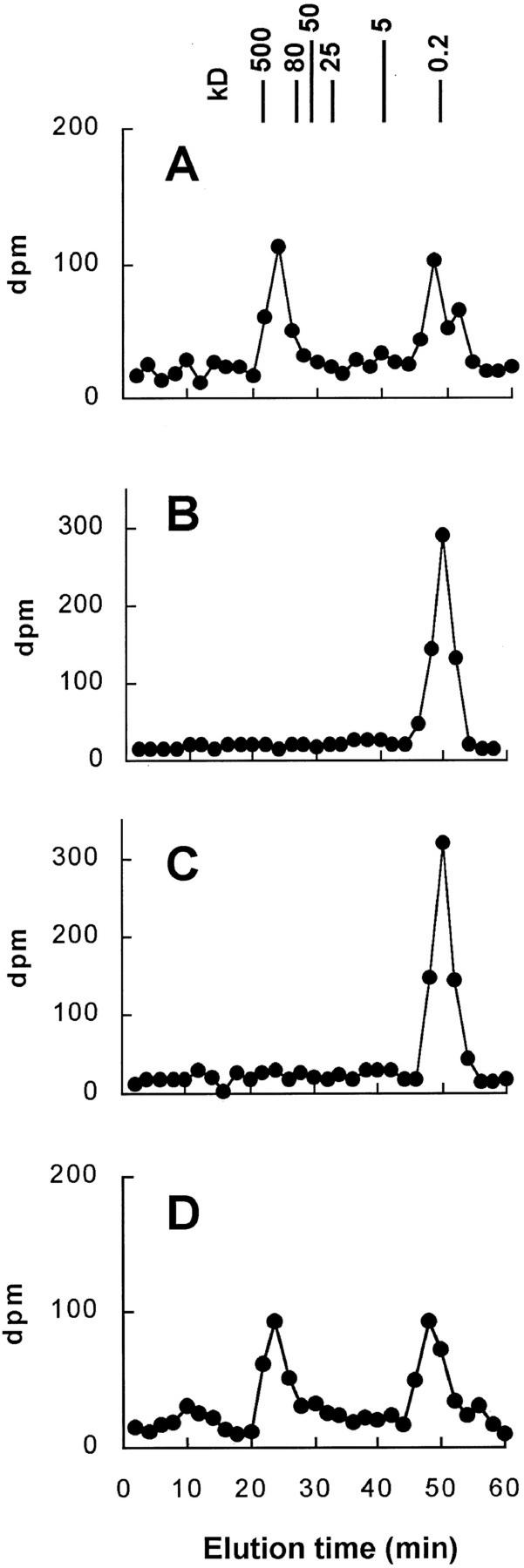

Arabinosyltransferase Activity in Microsomes

We have previously investigated the presence of β-1,4-xylosyltransferase activity in microsomal membranes isolated from wheat seedlings. The microsomes efficiently incorporated radioactivity from UDP-[14C]Xyl into xylan (Porchia and Scheller, 2000). In the present work, we have used similar conditions to investigate the presence of arabinosyltransferase by incubating microsomal membranes with UDP-[14C]Ara. Particulate enzyme preparations obtained from wheat seedlings catalyzed the synthesis of a polymeric product from UDP-[14C]Ara. The product was characterized by digestion with well-defined, monospecific enzymes and by gel-filtration chromatography (Fig. 1). The intact product eluted in two peaks (I and II) with molecular masses of ∼500 and ∼15 kD, respectively (Fig. 1A). After digestion of the radiolabeled product with endo-xylanase A, a major peak eluted with an elution time corresponding to Xyl, xylobiose, and xylotriose (Fig. 1B). Treatment with arabinofuranosidase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes terminal α-l-arabinofuranosyl residues, resulted in a partial digestion of peak I, whereas peak II remained in the original position (Fig. 1C), indicating that only peak I contains α-l-arabinofuranosyl residues. Treatment with proteinase K did not affect the elution of the products, indicating that radiolabeled protein was not present (Fig. 1D). To confirm the composition of the two peaks eluted from the Superose 12 column, the corresponding fractions were subjected to complete acid hydrolysis in 2 m trifluoroacetic acid, and the hydrolysates were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Peak I contained 22% of [14C]Ara and 78% of [14C]Xyl, whereas peak II contained only [14C]Xyl (data not shown). From these data, it was concluded that microsomal membranes would be difficult to use for characterization of arabinosyltransferase because 4-epimerization of UDP-Ara by the membrane preparations was very high. Therefore, we decided to prepare Golgi vesicles for the further investigation of arabinosyltransferase.

Figure 1.

Gel-filtration chromatography of solubilized 14C-labeled product. 14C-Labeled product was generated under standardized conditions using microsomes corresponding to 180 μg of protein and 22,000 dpm (1 μm) of UDP-[14C]Ara. The product was then solubilized using buffer (A), endo-xylanase A (B), arabinofuranosidase (C), and proteinase K (D) as described in “Materials and Methods.” The solubilized material was then separated over a Superose 12 column, and the radioactivity was determined in collected fractions. The elution of monosaccharide and Dextran standards is indicated.

Arabinosyltransferase Activity in Golgi Vesicles

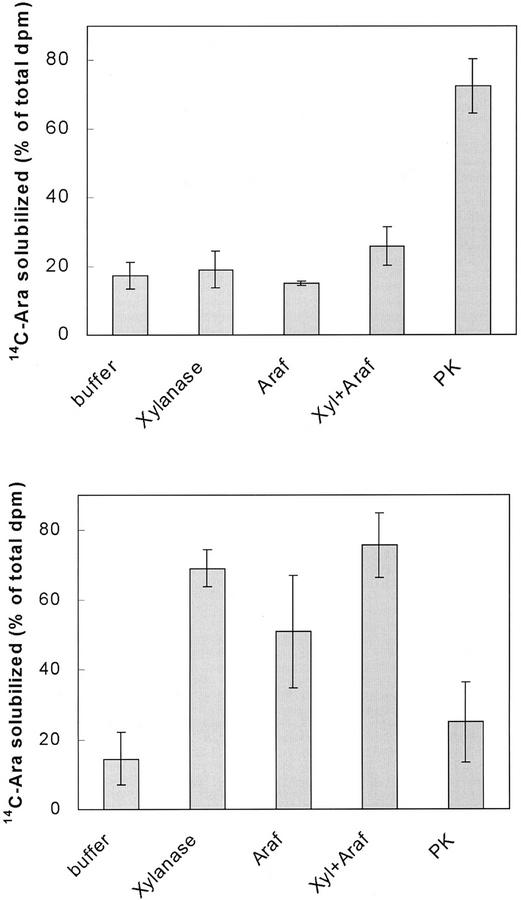

Solubilization of the 14C-Labeled Product Formed from UDP-[14C]Ara

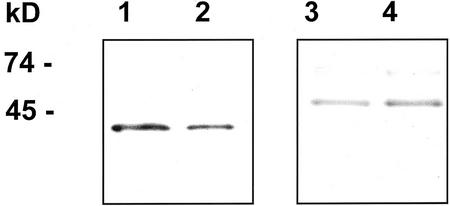

Preparations enriched in Golgi membranes were obtained by centrifugation on Suc density gradients. The identity of the fractions from the gradients was confirmed using antibodies against marker proteins (Fig. 2). The Golgi-enriched membranes synthesized a radiolabeled product, which was hydrolyzed in 2 m trifluoroacetic acid and analyzed by TLC. The radioactive product was composed mainly of Ara, whereas only traces (<5%) of Xyl were present. Thus, epimerization of UDP-Ara by Golgi membranes was very low compared with microsomal membranes. The nature of the 14C-Ara-containing product was determined by treatment with well-defined enzymes (Fig. 3A). Incubation of the radioactive product with pure endo-xylanase solubilized no more of the radioactive product than treatment with buffer alone, i.e. 15% to 20%. In a similar manner, treatment with xylanase or arabinofuranosidase alone or in combination had no significant effect. In contrast, proteinase K solubilized 73% of the radioactive product. Thus, we conclude that most of the 14C-Ara was incorporated into protein, whereas no detectable radioactivity was incorporated into arabinoxylan. The inability of arabinofuranosidase to solubilize the product indicates that Ara was not linked to the protein as α-arabinofuranoside residues.

Figure 2.

Identification of Golgi-enriched fraction. Microsomal membranes were separated by Suc gradient centrifugation as described in “Materials and Methods.” The vesicles at the upper interphase (between 0.25 and 1.1 m Suc; lanes 1 and 3) and lower interphase (between 1.1 and 1.3 m Suc; lanes 2 and 4) were collected. Vesicles corresponding to 1 μg of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against a Golgi marker (RGP, lanes 1 and 2) and an endoplasmic reticulum marker (calnexin/calreticulin, lanes 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Solubilization of 14C-labeled product. 14C-Labeled product was generated under standard conditions using Golgi membranes corresponding to 10 μg of protein and 22,000 dpm (1 μm) of UDP-[14C]Ara. The incubation was carried out in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of 1 mm of unlabeled UDP-Xyl. The product was solubilized using buffer, a combination of xylanase and arabinofuranosidase (Araf), or proteinase K (PK). After incubation, ethanol was added to precipitate undigested material. The suspension was then centrifuged to remove nonsolubilized material, and the radioactivity in the supernatant was determined. The data represent the average of duplicated samples from two to four separate experiments. The total radiolabel in the products varied between 300 and 500 dpm in the different experiments.

Analysis of the 14C-Labeled Product Obtained by Addition of Unlabeled UDP-Xyl in the Reaction Mixture

To determine if xylan backbone synthesis is a requirement for incorporation of 14C-Ara, we analyzed the radioactive product formed from UDP-[14C]Ara in the presence of unlabeled UDP-Xyl (Fig. 3B). In the presence of 1 mm of cold UDP-Xyl during the reaction, a very different product was obtained. Proteinase K had no significant effect, whereas xylanase A and a combination of xylanase A and arabinofuranosidase solubilized 69% and 76% of the radioactive product, respectively (Fig. 3B). Arabinofuranosidase alone solubilized 51% of the radioactivity. Similar results were obtained in the presence of 0.5 mm of unlabeled UDP-Xyl (data not shown). Thus, the addition of unlabeled UDP-Xyl directed the flow of 14C-Ara to a product that was sensitive to digestion with xylanase while eliminating the formation of a product sensitive to digestion with proteinase K.

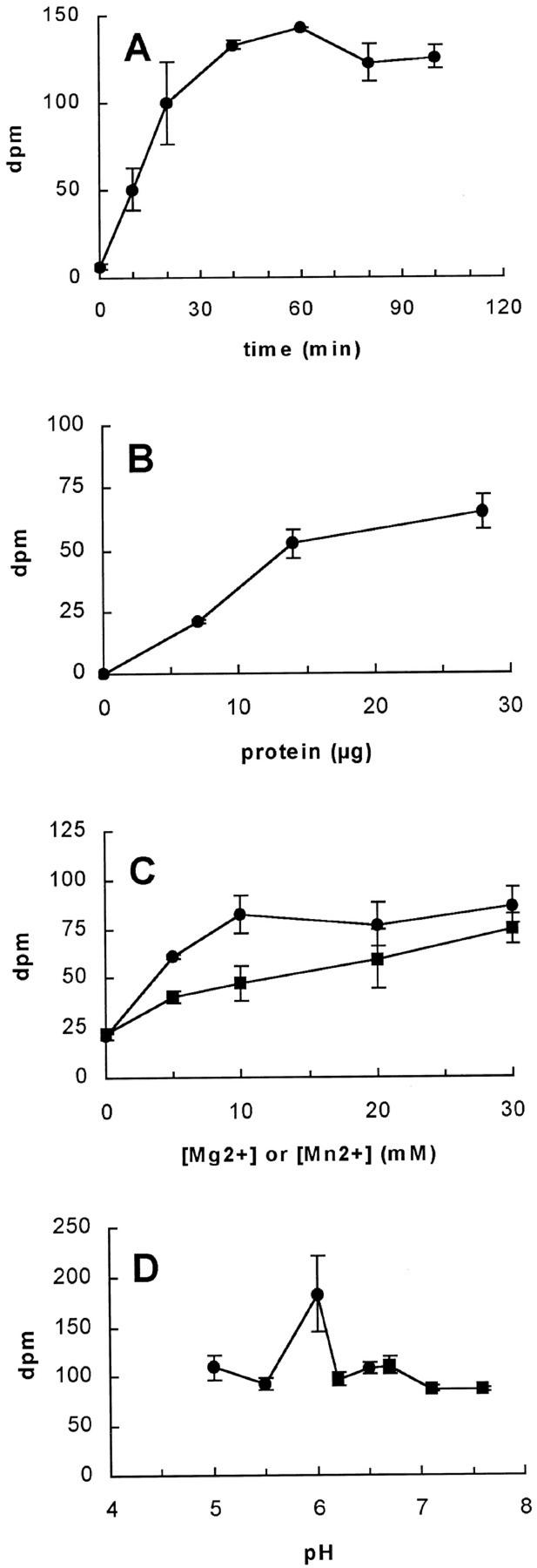

Characterization of AX-AraT Activity

From the above results, we concluded that the presence of unlabeled UDP-Xyl results in a radiolabeled product consisting primarily of arabinoxylan. Therefore, we have optimized the AX-AraT assay in presence of unlabeled UDP-Xyl (Fig. 4). The time and protein concentration dependence were determined by stopping the reaction mixture, washing the product, and measuring the total radioactivity incorporated by scintillation counting. The total incorporation of 14C-Ara into radiolabeled product was dependent on the amount of protein used and the reaction time (Fig. 4, A and B) as expected for an enzymatic reaction. The incorporation reached a maximum when Golgi vesicles with a protein content of ∼30 μg were used (Fig. 4B) and after 40 min of incubation (Fig. 4A). The total incorporation was proportional to the amount of UDP-[14C]Ara used up to 5 μm (data not shown). Due to the limited amounts of substrate available, it was unfortunately not feasible to determine the apparent Km. The effect of divalent cations and pH was determined by stopping the reaction mixture, washing the products, and incubating them with a combination of xylanase and arabinofuranosidase. After incubation with the enzymes, insoluble and higher molecular mass materials were reprecipitated by the addition of ethanol and were then pelleted by centrifugation. In all cases, most of the radioactivity was present in the supernatant, indicating that the major product was arabinoxylan. AX-AraT activity was enhanced by the addition of divalent cations, but the addition of divalent cations was not an absolute requirement (Fig. 4C). At a concentration of 10 mm Mn2+ or Mg2+, the AX-AraT activity increased approximately 4- and 2-fold, respectively. AX-AraT was active in the investigated pH range of 5.0 to 7.6, with peak activity at pH 6 (Fig. 4D). The remaining experiments reported below were carried out under the optimal conditions determined from the experiments reported in Figure 4 (see “Materials and Methods”).

Figure 4.

Characterization of 14C-incorporation and arabinosyltransferase activity. 14C-Labeled product was generated under standard conditions as described in “Materials and Methods. ” Golgi membranes corresponding to 10 μg of protein (except in B), 0.5 mm of UDP-Xyl, and 22,000 dpm (1 μm) of UDP-[14C]Ara were used. A, The incubation time was varied. B, The amount of Golgi vesicles (protein) used was varied. C, The concentrations of Mn 2+ (●) or Mg 2+ (▪) were varied. D, The pH was varied using MES buffer (●) and phosphate buffer (▪). Dpm in A and B represents total incorporation of 14C-Ara into ethanol-insoluble product, and dpm in C and D represents radioactivity measured in the supernatant after digestion with a combination of xylanase A and arabinofuranosidase. The data represent the average of duplicate or triplicate samples. Similar results were obtained in two separate experiments.

Analysis of the 14C-Labeled Product by Gel-Filtration Chromatography

The radiolabeled product resulting from incubation of Golgi vesicles with UDP-[14C]Ara in the presence of 0.5 mm of unlabeled UDP-Xyl was further analyzed by gel-filtration chromatography (Fig. 5). The intact product eluted in a peak corresponding to a molecular mass of ∼500 kD (Fig. 5A). The peak with an elution time similar to monosaccharides and small oligosaccharides represents residual unincorporated substrate (Fig. 5A). Treatment with xylanase A or a combination of xylanase A and arabinofuranosidase resulted in the disappearance of the high molecular mass peak and the appearance of a much smaller product that eluted in the included volume similar to monosaccharides and small oligosaccharides (Fig. 5, B and C). When the radioactive product was treated with proteinase K, the pattern obtained was the same as for the intact product (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Gel-filtration chromatography of solubilized 14C-labeled product. 14C-Labeled product was generated in the presence of 0.5 mm of unlabeled UDP-Xyl using Golgi membranes corresponding to 30 μg of protein and 95,000 dpm (5 μm) of UDP-[14C]Ara. The incubation time was 60 min. The recovered product was solubilized using buffer (A), xylanase A (B), a combination of xylanase A and arabinofuranosidase (C), or proteinase K (D). The solubilized material was then separated over a Superose 12 column, and the radioactivity was determined in collected fractions.

Reversibility of 14C-Arabinosylation of Protein

Polypeptides that become labeled upon incubation with UDP-[14C]Glc have been reported in membrane and soluble enzyme preparations from different species, including pea (Pisum sativum; Dhugga et al., 1991, 1997), Arabidopsis, maize (Zea mays), and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Delgado et al., 1998). These polypeptides have been suggested to facilitate the channeling of UDP-activated sugars from the cytoplasm through Golgi membranes to lumenal sites, where they can be used as substrates for glycosyltransferases to synthesize products such as xyloglucan (Faik et al., 2000).

In the present work, it was demonstrated that when Golgi vesicles were incubated in absence of cold UDP-Xyl, 14C-Ara was incorporated into protein. To determine the reversibility of 14C-Ara labeling onto the protein, we carried out the following experiment. Golgi vesicles were first incubated with UDP-[14C]Ara for 30 min to produce the labeled protein, and aliquots were removed as controls to be analyzed. Following this incubation, cold UDP-Xyl was added to the reaction, and incubation was continued for an additional 30 min. After this second incubation, the reaction was stopped and the samples were analyzed by enzymatic treatment. After the initial incubation with only UDP-[14C]Ara, 62% of the radioactivity (318 ± 13 dpm) could be solubilized with proteinase K, whereas the combination of xylanase A and arabinofuranosidase did not solubilize more radioactivity than the buffer control (116 ± 8 dpm). After the addition of unlabeled UDP-Xyl and incubation for an additional 30 min, 78% of the product (407 ± 23 dpm) could be solubilized with a combination of xylanase A and arabinofuranosidase, whereas treatment with proteinase K released no more radioactivity than treatment with buffer (130 ± 12 dpm). Thus, the protein was reversibly labeled and the removal of label took place simultaneously with the transfer of label to de novo synthesized xylan. Similar results were obtained with several different preparations of Golgi vesicles.

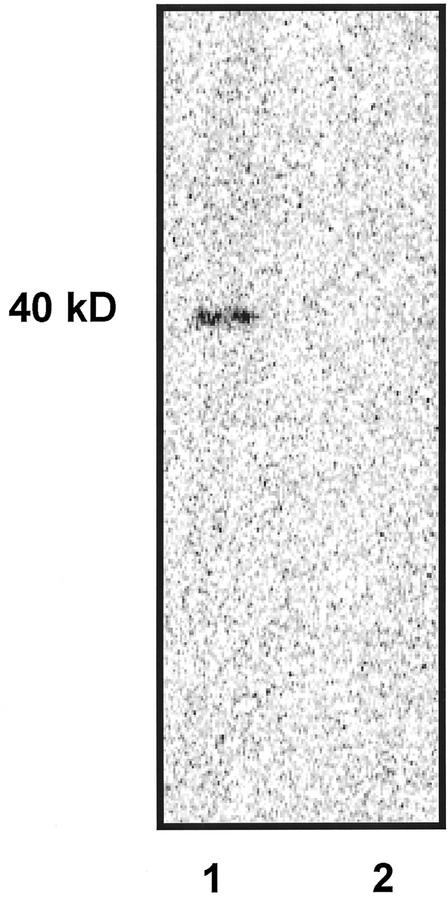

Presence of Radiolabeled Protein

To further investigate the presence of arabinosylated protein, we carried out the same experiment described above in which samples were removed after the first incubation with only UDP-[14C]Ara and after the second incubation with the addition of unlabeled UDP-Xyl. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and were exposed to PhosphorImager screens (Fig. 6). A single labeled band of approximately 40 kD was found in samples removed after the first incubation containing only UDP-[14C]Ara (Fig. 6, lane 1), whereas no band was detected in samples removed after the second incubation with addition of unlabeled UDP-Xyl (Fig. 6, lane 2).

Figure 6.

Reversibility of protein arabinosylation. 14C-Labeled product was generated under optimized conditions using Golgi membranes corresponding to 30 μg of protein and 66,000 dpm (3 μm) of UDP-[14C]Ara. The reaction products were formed after initial incubation of 30 min with UDP-[14C]Ara (lane 1) and after subsequent incubation of 30 min in the presence of 0.5 mm unlabeled UDP-Xyl (lane 2). The products were precipitated with ethanol and were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gel was exposed to PhosphorImager screens.

DISCUSSION

We have previously used microsomal membranes from wheat seedlings to investigate xylosyltransferase involved in arabinoxylan biosynthesis (Porchia and Scheller, 2000). The microsomal preparation would be expected to contain UDP-Xyl 4-epimerase, and this enzyme is responsible for the production of UDP-l-[14C]Ara from UDP-d-[14C]Xyl. However, the radioactive product obtained in this earlier work consisted mainly of Xyl, whereas only traces of Ara were found, indicating a low 4-epimerization of UDP-Xyl (Porchia and Scheller, 2000). Attempting to detect the presence of arabinosyltransferase activity, we have incubated microsomal membranes with UDP-[14C]Ara. Two radioactive products were separated by gel-filtration chromatography (Fig. 1A). In contrast to the earlier results, one of the products consisted of 78% of Xyl, whereas the other consisted exclusively of Xyl, indicating a high 4-epimerase activity. The equilibrium of the epimerase reaction favors UDP-Xyl (Fan and Feingold, 1970; Pauly et al., 2000), but the very pronounced difference in the degree of epimerization when microsomal membranes were incubated with UDP-[14C]Ara or UDP[14C]Xyl was nevertheless surprising. Other previous studies of xylan synthesis have also been hampered by the presence of UDP-Xyl-4-epimerase (Bailey and Hassid, 1966; Odzuck and Kauss, 1972; Dalessandro and Northcote, 1981a, 1981b; Baydoun et al., 1989). Because hemicelluloses and pectin are synthesized in the Golgi apparatus (Carpita and Gibeaut, 1993) and the interference of 4-epimerase makes the properties of the enzyme difficult to study in microsomal preparations, we decided to use Golgi-enriched vesicles for the investigation of arabinosyltransferase.

Golgi vesicles were incubated with UDP-[14C]Ara and the resultant radioactive product consisted mainly of [14C]Ara, whereas only traces of [14C]Xyl were found, indicating an insignificant 4-epimerase activity. Similar results were found for particulate enzyme preparations obtained from bean that were incubated with UDP-l-[l-3H]Ara (Bolwell and Northcote, 1981). In bean, most radioactivity was incorporated into pectin, and radioactive Xyl only accounted for 6% to 8% of the radioactivity. In the present investigation, characterization of the radioactive product revealed that most of the labeling was incorporated into protein and only traces of [14C]Ara were incorporated into xylan (Fig. 3A).

In the presence of unlabeled UDP-Xyl, most of the radioactive product was arabinoxylan, whereas no radiolabeled protein was detected (Fig. 3B). Thus, nascent xylan acted as an acceptor for the further incorporation of [14C]Ara from UDP-[14C]Ara. Xylan xylosyltransferase is presumably a processive enzyme and its synergy with the arabinosyltransferase suggests that the two enzymes form a complex with the nonreducing end of the growing polysaccharide. Similar interactions between backbone-synthesizing enzymes and decorating enzymes have been reported for the xylan glucuronosyltransferase (Waldron and Brett, 1983; Baydoun et al., 1989). Sustained incorporation of [14C]GlcUA from UDP-d-[14C]GlcUA into glucuronoxylan only occurred in the presence of UDP-d-Xyl, indicating that xylan was being synthesized and acted as an acceptor for the further incorporation of GlcUA. A similar interaction is also known between the galactosyltransferase and mannosyltransferase involved in galactomannan biosynthesis (Reid et al., 1995).

Because the presence of UDP-Xyl results in a product consisting mainly of arabinoxylan, the AX-AraT activity was further characterized in the presence of nonradioactive UDP-Xyl during the incubation. AX-AraT activity was dependent on time and protein concentration. The maximum yield of product occurs within 40 min, and the enzyme was active over a broad pH range, with optimum at pH 6.0. Optimum pH values between 6 and 6.5 were reported for arabinosyltransferase from mung bean (Vigna radiata) shoots involved in arabinan synthesis (Odzuck and Kauss, 1972). Xylan xylosyltransferase from wheat is also active over a wide range, but has peak activity at pH 6.8 (Porchia and Scheller, 2000). The AX-AraT activity was enhanced by addition of Mg2+ or Mn2+ as has been found for arabinosyltransferases involved in arabinan biosynthesis (Odzuck and Kauss, 1972; Bolwell and Northcote, 1981) and in general for other glycosyltransferases. The xylan xylosyltransferase from wheat was also enhanced in the presence of Mg2+ or Mn2+, although the effect was less pronounced (Porchia and Scheller, 2000).

In the absence of added UDP-Xyl, only protein was radiolabeled with [14C]Ara. A single labeled protein migrated on SDS-PAGE with an apparent molecular mass of 40 kD (Fig. 6). However, upon subsequent incubation with UDP-Xyl, the label disappeared. The addition of UDP-Glc similarly led to a disappearance of the radiolabel. These properties are similar to what has been described for reversibly glycosylated proteins (RGPs), which are soluble proteins found in association with the Golgi membranes. During studies of polysaccharide synthesis in pea Golgi membranes, Dhugga et al. (1991) identified a 41-kD protein doublet that they suggested was involved in polysaccharide synthesis. The authors showed that this protein could be glycosylated by radiolabeled UDP-Glc, but that this labeling could be reversibly competed with unlabeled UDP-Glc, UDP-Xyl, and UDP-Gal, the sugars that make up xyloglucan, but not by other nucleotide sugars. The effect of UDP-Ara was not reported in these previous investigations. The 41-kD protein was named Pisum sativum reversibly glycosylated polypeptide-1 [PsRGP1]; Dhugga et al., 1997), and antibodies raised against PsRGP1 showed that it is soluble and localized to the Golgi compartment (Dhugga et al., 1997).

Delgado et al. (1998) have isolated and characterized a cDNA clone encoding the Arabidopsis homolog of PsRGP1, named AtRGP1. Sequence comparisons with previously defined UDP-Glc-binding sites (Delmer and Amor, 1995; Pear et al., 1996; Saxena and Brown, 1997) showed that AtRGP1 contains a similar motif, which may be involved in the binding of UDP-sugars. A single amino acid, Arg-158, was found to be labeled with [14C]Glc, in accordance with the single glycosylation of PsRGP1 (Dhugga et al., 1991). Several authors have speculated that RGPs may in some way be involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis, as protein primers, as intermediates involved in transport, or as real glycosyltransferases (Dhugga et al., 1997; Saxena and Brown, 1999; Faik et al., 2000). There is no evidence for a primer function of RGP other than an analogy to protein-primed starch and glycogen synthesis (Moreno et al., 1986). However, the ability of RGPs to be reversibly glycosylated, their exposure to the cytoplasm in which nucleotide sugars are found, and their association with Golgi membranes support the notion that RGPs could act as carriers of UDP-sugars from the cytoplasm to the Golgi apparatus (Delgado et al., 1998). The existence of RGP in dicots (Dhugga et al., 1991) and monocots (Singh et al., 1995), but apparently not in other organisms, suggests a plant-specific function. Most authors have assumed that the RGPs contained glycosidic bonds, as this would agree with the behavior of the protein on SDS-PAGE. However, a recent report provides evidence that the glycosylated RGP is an unreactive glycoprotein formed relatively slowly by glycosyl transfer from a rapidly formed UDP-sugar-binding polypeptide (Faik et al., 2000). The authors suggest that it is the evanescent-bound sugar nucleotide that is capable of acting as a sugar donor and not the final stable glycoprotein.

Arabinoxylan formation is enhanced by addition of unlabeled UDP-Xyl in the reaction medium. We cannot conclude through our experiments that [14C]Ara is transferred from the labeled protein onto arabinoxylan. The alternative that UDP-Xyl is replacing the Ara on the protein in a reaction unrelated to xylan biosynthesis cannot be excluded. A chase experiment with excess unlabeled UDP-Ara would be required to make this conclusion, but unfortunately, the substrate was not available. It is interesting that [14C]ferulic acid has also been shown to be transiently incorporated into a 40-kD protein in wheat (N. Obel and H.V. Scheller, unpublished data). In this protein, ferulic acid appeared to be bound to C5 of an arabinofuranosyl residue. If the two 40-kD proteins are identical, the linkage of ferulic acid eliminates the possibility that UDP-Ara is bound as an intact nucleotide sugar as found for the protein studied by Faik et al. (2000). This would make it more likely that the 40-kD protein in wheat is directly involved in arabinoxylan biosynthesis. We are currently investigating the identity of the labeled proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals, Reagents, and Enzymes

UDP-l-[14C]Ara with specific activity of 9.9 GBq mm−1 was prepared as described in Pauly et al. (2000). Wheat (Triticum aestivum cv Cadenza) arabinoxylan and arabinofuranosidase from Aspergillus niger were purchased from Megazyme International (Bray, Ireland). Homogeneous endo-xylanase A from A. niger was a gift from Drs. Troels Gravesen and Susan Madrid (Danisco Biotechnology, Copenhagen). The xylanase had no detectable arabinanase, xyloglucanase, or arabinofuranosidase activity, and the arabinofuranosidase had no detectable xylanase activity. Proteinase K was from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany) and had no detectable hydrolytic activity with arabinoxylan. Dextran molecular mass standards were purchased from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland).

Plant Material

Wheat seedlings were grown in trays of vermiculite in controlled environment chambers at 20°C with 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1 and a 16-h photoperiod. Four-day-old seedlings were used for preparation of microsomes and Golgi vesicles.

Preparation of Microsomes

The entire preparation of microsomes took place in a cold room (∼4°C). Shoots and coleoptiles were harvested with a razor blade and were ground with a mortar and pestle in a buffer (1 mL g−1 of plant material) of 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 10% (w/v) polyvinylpolypyrrolidone, 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mm MgCl2, and 0.4 m Suc. The suspension was filtered through a nylon cloth (30-μm mesh), and was centrifuged for 15 min at 3,000g to remove debris. The resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 48,000g for 1 h to pellet the microsomes, which were resuspended in homogenization buffer without polyvinylpolypyrrolidone at a ratio of approximately 30 μL of buffer g−1 fresh weight of plant tissue. Total protein was determined according to Bradford (1976) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

Preparation of Golgi Vesicles

The method to obtain Golgi-derived vesicles was based on the procedure of Leelavathi et al. (1970) with minor modifications. Shoots and coleoptiles (8–12 g) were homogenized by hand with razor blades in a buffer (1 mL g−1 fresh weight) of 0.5 m Suc, 0.1 m potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 5 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm DTT. After the tissue was finely chopped, it was homogenized for 2 min in a mortar. This procedure was carried out at 0°C. The homogenate was filtered through nylon cloth (30-μm mesh) and was centrifuged at 1,000g for 2 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a 4-mL 1.3 m Suc cushion and was centrifuged at 100,000g for 90 min. The upper phase was removed without disturbing the interphase fraction. A discontinuous gradient was then formed by overlaying the solution with 5 mL of 1.1 m Suc and 4 mL of 0.25 m Suc. The Suc solutions were prepared in a buffer containing 0.1 m potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 5 mm MgCl2, and 1 mm DTT. The gradients were centrifuged for 90 min at 100,000g. The interphase at 0.25/1.1 Suc was collected and stored at −80°C until use. The identity and purity of the fractions was analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against representative marker proteins. Polyclonal antibodies against RGP from pea (Pisum sativum; Dhugga et al., 1997) and calnexin/calreticulin from barley (Hordeum vulgare; Møgelsvang and Simpson, 1998) were kind gifts from Dr. Kanwarpal S. Dhugga (Pioneer Hi-Bred International, Des Moines, IA) and Dr. David J. Simpson (Carlsberg Laboratory, Copenhagen), respectively. The immunoblots were visualized using secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and a chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Standard Assay for Arabinosyltransferase

The standard assay was used unless otherwise indicated. The reaction mixture (final volume of 40 μL) consisted of 10 μL of reaction buffer (200 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 0.8 m Suc, 40 mm MgCl2, and 4 mm DTT), 7 mm MnCl2, 22,000 dpm of UDP-[14C]Ara (∼1 μm), and 20 μL of the microsomal membranes (containing approximately 180 μg of protein) or 20 μL of Golgi vesicles (containing approximately 10–15 μg of protein). The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min at 30°C, and the reaction was then terminated by boiling for 5 min, cooled on ice, and 500 μL of chloroform:methanol (3:2, v/v) was added. The sample was mixed on a vortex mixer, and the precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in 500 μL of aqueous 65% (v/v) ethanol, and 90 μg of wheat arabinoxylan was added as carrier. The sample was centrifuged again and the supernatant was removed. The resultant pellet was washed with 65% (v/v) ethanol until the washes were free of the radioactivity. The final pellet was suspended in 200 μL of water, boiled for 5 min, and counted in a liquid-scintillation counter after addition of 2 mL of scintillation fluid (Ecoscint, National Diagnostic, Manville, NJ), or was treated with different enzymes as described below.

Optimization of AX-AraT Assay

Time course and protein concentration dependence for enzyme activity was determined by using the standard assay. After reaction, the product was washed, and the total radioactivity in the final pellets was determined by liquid-scintillation counting after the addition of 2 mL of scintillation fluid. Effect of divalent cations and optimum pH for the enzyme activity was investigated by using the standard assay in which the buffer reaction did not contain any divalent ions and by adding different concentrations (0–30 mm) of MnCl2 or MgCl2 or by using the following buffers to obtain the required pH: MES, pH 5.0 to 6.7, and potassium phosphate, pH 6.2 to 7.6. After the reaction, the recovered product was washed and incubated with a combination of xylanase A and arabinofuranosidase at 30°C for 3 h (see below). After stopping the reaction by boiling, the products were reprecipitated by adding ethanol (70% [v/v] final concentration) and arabinoxylan (160 μg) as a carrier and they were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min. The supernatants containing the solubilized material and the pellets were subjected to liquid scintillation counting.

Optimized Assay for AX-AraT

The incorporation reaction (final volume of 60 μL) consisted of 15 μL of reaction buffer (200 mm MES, pH 6, 0.8 m Suc, and 4 mm DTT), 5 mm MnCl2, 4.5 μm of UDP-[14C]Ara (95,000 dpm), 0.5 mm UDP-Xyl, and Golgi vesicles corresponding to approximately 15 to 20 μg of protein. After the incubation at 30°C for 60 min, the sample was treated as described above for the standard assay.

Enzymatic Digestion of the 14C-Labeled Product

In general, the final pellet obtained was first suspended in 120 μL of water and boiled for 3 min. After cooling down, buffer and enzymes were added. The digests/solubilizations were incubated for 3 h at 30°C. Insoluble and higher molecular mass materials were reprecipitated by adding ethanol (70% [v/v] final concentration) and arabinoxylan (160 μg) as a carrier, they were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min, and the supernatants were counted in a liquid-scintillation counter or subjected to gel-filtration chromatography as described below.

Enzymes were used in the following concentrations and buffer systems: endo-xylanase A (0.002 U, 1 unit releases 1 μmol of reducing arabinoxylan oligosaccharide min−1) and arabinofuranosidase (0.01 U, 1 unit releases 1 μmol of Ara from arabinoxylan min−1) were incubated in 50 mm sodium acetate (pH 5.2). Proteinase K (0.2 mg) was incubated in water.

Gel-Filtration Chromatography of 14C-Labeled Product

The samples were treated with different enzymes as described above. Supernatants obtained after reprecipitation by the addition of ethanol and centrifugation were spin-filtered and analyzed by gel-filtration chromatography on a Superose 12 column (30 cm long, 1 cm i.d.; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The column was equilibrated in 50 mm ammonium formate (pH 5.0). The sample was applied and eluted with the same buffer at a flow rate of 0.4 mL min−1. Fractions (0.8 mL) were collected and the radioactivity was determined by liquid-scintillation counting. The Dextran standards were monitored in the eluate using a refractive-index detector (model 131; Gilson, Middleton, WI).

Total Acid Hydrolysis

The 14C-labeled product recovered was resuspended in water (250 μL) and was incubated for 120°C for 1 h after the addition of 44 μL of trifluoroacetic acid (13.5 m). The treated product was dried, resuspended in water, and separated on TLC plates (Silica Gel 60 F254; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in ethyl acetate:acetic acid:methanol:water (12:3:3:2, v/v) for 2 h. Unlabeled standards were detected by dipping the TLC plates into a solution of sulfuric acid:ethanol (1:9, v/v) and heating the plate until the sugars charred. Radiolabeled products were detected by cutting the sheet corresponding to the sample into 2.5-mm strips for scintillation counting.

To perform total acid hydrolysis of fractions collected from the Superose 12 column, the fractions were combined, dried, resuspended in water, and treated as described above.

Presence of Radiolabeled Protein

Optimized assay was used to generate six reaction samples, which were incubated for 30 min. After this first incubation, three samples were stopped by boiling and were combined. The remaining three reaction tubes were incubated for an additional 30 min after the addition of 0.5 mm cold UDP-Xyl after which the samples were stopped and combined. The pooled samples were dried and resuspended in 30 μL of SDS sample buffer and were subjected to SDS-PAGE in 8% to 25% (w/v) High-Tris gradient gels. The gels were dried and exposed to storage phosphor screens for approximately 3 d. The exposed screens were analyzed with a PhosphorImager (model 425F; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation and by the Danish Ministry of Food.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.003400.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aspinall GO. Chemistry of cell wall polysaccharides. In: Preiss J, editor. The Biochemistry of Plants. Vol. 3. London: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 473–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey RW, Hassid WZ. Xylan synthesis from uridine-diphosphate-d-xylose by particulate preparations from immature corncobs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;56:1586–1593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.5.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydoun EAH, Waldron KW, Brett CT. The interaction of xylosyltransferase and glucuronyltransferase involved in glucuronoxylan synthesis in pea (Pisum sativum) epicotyls. Biochem J. 1989;257:853–858. doi: 10.1042/bj2570853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford MR. Mechanism of action and potential environmental benefits from the use of feed enzymes. Animal Feed Sci Technol. 1995;53:145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP. Microsomal arabinosylation of polysaccharide and elicitor-induced carbohydrate-binding glycoprotein in French bean. Phytochemistry. 1986;25:1807–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP, Northcote DH. Control of hemicellulose and pectin synthesis during differentiation of vascular tissue in bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) callus and in bean hypocotyls. Planta. 1981;152:225–233. doi: 10.1007/BF00385148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP, Northcote DH. Arabinan synthase and xylan synthase activities of Phaseolus vulgaris: subcellular localization and possible mechanism of action. Biochem J. 1983a;210:497–507. doi: 10.1042/bj2100497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP, Northcote DH. Induction by growth factors of polysaccharide synthases in bean cell suspension cultures. Biochem J. 1983b;210:509–515. doi: 10.1042/bj2100509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita N, Gibeaut DM. Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the wall during growth. Plant J. 1993;3:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1993.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpita NC. Structure and biogenesis of the cell wall of grasses. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:445–476. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleemput G, Booijt C, Hessing M, Gruppen H, Delcour JA. Solubilization and changes in molecular weight distribution of arabinoxylans and protein in wheat flours during bread-making, and the effects of endogenous arabinoxylan hydrolysing enzymes. J Cereal Sci. 1997;26:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dalessandro G, Northcote DH. Xylan synthase activity in differentiated xylem cells of sycamore trees (Acer pseudoplatanus) Planta. 1981a;151:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00384237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalessandro G, Northcote DH. Increase of xylan synthase activity during xylem differentiation of the vascular cambium of sycamore and poplar trees. Planta. 1981b;151:61–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00384238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado IJ, Wang Z, Rocher A, Keegstra K, Raikhel N. Cloning and characterization of AtRGP1: a reversibly autoglycosylated Arabidopsis protein implicated in cell wall biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:1339–1349. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.4.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmer DP, Amor Y. Cellulose biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:987–1000. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhugga KS, Tiwari SC, Ray PM. A reversibly glycosylated polypeptide (RGP1) possibly involved in plant cell wall synthesis: purification, gene cloning and trans Golgi localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7679–7684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhugga KS, Ulvskov P, Gallagher SR, Ray PM. Plant polypeptides reversibly glycosylated by UDP-glucose: possible components of Golgi β-glucan synthase in pea cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21977–21984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards ME, Dickson CA, Chengappa S, Sidebottom C, Gidley MJ, Reid JSG. Molecular characterisation of a membrane-bound galactosyltransferase of plant cell wall matrix polysaccharide biosynthesis. Plant J. 1999;19:691–697. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faik A, Desveaux D, Maclachlan G. Sugar-nucleotide-binding and autoglycosylating polypeptide(s) from nasturtium fruit: biochemical capacities and potential functions. Biochem J. 2000;347:857–865. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan DF, Feingold DS. Nucleoside diphosphate-sugar 4-epimerases: uridine diphosphate arabinose 4-epimerase of wheat germ. Plant Physiol. 1970;46:592–595. doi: 10.1104/pp.46.4.592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut DM, Carpita NC. Separation of membranes by flotation centrifugation for in vitro synthesis of plant cell wall polysaccharides. Protoplasma. 1990;156:82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Gibeaut DM, Carpita NC. Tracing cell wall biogenesis in intact cells and plants: selective turnover and alteration of soluble and cell wall polysaccharides in grasses. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:551–561. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong ZL, Delauney AJ, Verma DPS. A cell plate specific callose synthase and its interaction with phragmoplastin. Plant Cell. 2001;13:755–768. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iiyama K, Lam TBT, Meikle PJ, Ng K, Rhodes DI, Stone BA. Cell wall biosynthesis and its regulation. In: Jung HG, Buxton DR, Hatfield RD, Ralph J, editors. Forage Cell Wall Structure and Digestibility. Madison, WI: Crop Science Society of America; 1993. pp. 621–683. [Google Scholar]

- Leelavathi DE, Estes LW, Feingold DS, Lombardi B. Isolation of a Golgi-rich fraction from rat liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1970;211:124–138. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil M, Darvill AG, Fry SC, Albersheim P. Structure and function of the primary cell walls of plants. Annu Rev Biochem. 1984;53:625–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.53.070184.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møgelsvang S, Simpson D. Changes in the levels of seven proteins involved in polypeptide folding and transport during endosperm development of two barley genotypes differing in storage protein localisation. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;36:541–552. doi: 10.1023/a:1005916427024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Cardini CE, Tandecarz JS. α-Glucan synthesis on a protein primer, uridine diphosphoglucose:protein transglycosylase: separation from starch synthetase and phosphorylase and a study of its properties. Eur J Biochem. 1986;157:539–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odzuck W, Kauss H. Biosynthesis of pure araban and xylan. Phytochemistry. 1972;11:2489–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly M, Porchia AC, Olsen CE, Nunan KJ, Scheller HV. Enzymatic synthesis and purification of uridine diphospho-β-l-arabinopyranose, a substrate for the biosynthesis of plant polysaccharides. Anal Biochem. 2000;278:69–73. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pear JR, Kawagoe Y, Schreckengost WE, Delmer DP, Stalker DM. Higher plants contain homologs of the bacterial celA genes encoding the catalytic subunit of cellulose synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12637–12642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin RM, DeRocher AE, Bar-Peled M, Zeng WQ, Norambuena L, Orellana A, Raikhel NV, Keegstra K. Xyloglucan fucosyltransferase, an enzyme involved in plant cell wall biosynthesis. Science. 1999;284:1976–1979. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5422.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porchia AC, Scheller HV. Arabinoxylan biosynthesis: identification and partial characterization of β-1,4-xylosyltransferase from wheat. Physiol Plant. 2000;110:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- Reid JSG, Edwards M, Gidley MJ, Clark AH. Enzyme specificity in galactomannan biosynthesis. Planta. 1995;195:489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers MW, Bolwell GP. Partial purification of Golgi-bound arabinosyltransferase and two isoforms of xylosyltransferase from French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Biochem J. 1992;288:817–822. doi: 10.1042/bj2880817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena IM, Brown RM., Jr Identification of cellulose synthase(s) in higher plants: sequence analysis of processive β-glycosyltransferases with the common motif “D,D,D35Q(R,Q) XRW.”. Cellulose. 1997;4:33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena IM, Brown RM., Jr Are the reversibly glycosylated polypeptides implicated in plant cell wall biosynthesis non-processive β-glycosyltransferases? Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:6–7. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(98)01358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh DG, Lomako J, Lomako WM, Whelan WJ, Meyer HE, Serwe M, Metzger JW. β-Glycosylarginine: a new glucose-protein bond in a self-glucosylating protein from sweet corn. FEBS Lett. 1995;376:61–64. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron KW, Brett CT. A glucuronyltransferase involved in glucuronoxylan synthesis in pea (Pisum sativum) epicotyls. Biochem J. 1983;213:115–122. doi: 10.1042/bj2130115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron KW, Brett CT. Interaction of enzymes involved in cell wall heteropolysaccharide biosynthesis. In: Brett CT, Hillman JR, editors. Biochemistry of Plant Cell Walls, SEB Seminar Series. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1985. pp. 79–97. [Google Scholar]