Abstract

A small family of novel basic leucine zipper proteins that includes abscisic acid (ABA)-INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) binds to the promoter region of the lea class gene Dc3. The factors, referred to as AtDPBFs (Arabidopsis Dc3 promoter-binding factors), were isolated from an immature seed cDNA library. AtDPBFs bind to the embryo specification and ABA-responsive elements in the Dc3 promoter and are unique in that they can interact with cis-elements that do not contain the ACGT core sequence required for the binding of most other plant basic leucine zipper proteins. Analysis of full-length cDNAs showed that at least five different Dc3 promoter-binding factors are present in Arabidopsis seeds; one of these, AtDPBF-1, is identical to ABI5. As expected, AtDPBF-1/ABI5 mRNA is inducible by exogenous ABA in seedlings. Despite the near identity in their basic domains, AtDPBFs are distinct in their DNA-binding, dimerization, and transcriptional activity.

LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) genes as a group are highly expressed during late stages of embryo development (Hughes and Galau, 1991; Thomas, 1993; Parcy et al., 1994). lea gene products are ubiquitous among higher plants, and they are probably involved in the protection of cells from dehydration (Dure et al., 1989; Dure, 1993; Ingram and Bartels, 1996; Xu et al., 1996). Expression of many lea genes is not only seed specific but is also inducible by abscisic acid (ABA) or environmental stresses such as drought and high salinity (Skriver and Mundy, 1990; Chandler and Robertson, 1994; Ingram and Bartels, 1996).

Dc3 is a carrot (Daucus carota) lea class gene that is abundantly expressed during somatic embryogenesis (Wilde et al., 1988). The Dc3 promoter drives β-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene expression in developing seeds of transgenic tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and in nonembryonic tissues exposed to exogenous ABA and conditions of water deficit (Seffens et al., 1990; Vivekananda et al., 1992; Siddiqui et al., 1998). Analysis of the Dc3 promoter revealed minimal sequences necessary for embryo-specific expression residing within a 117-bp region including the transcription start site (Thomas, 1993; Chung, 1996; Thomas et al., 1997). However, this proximal promoter region (PPR) is not sufficient for ABA-induced expression; the distal promoter region (DPR), located between −314 and −287, is also required for ABA response in addition to the PPR (Chung, 1996; Thomas et al., 1997). The PPR contains five related cis regulatory elements required for expression in embryogenesis; these elements (E motifs) share the consensus sequence ACACNNG. Elements with NNNCGTGT consensus are repeated within the minimal DPR. These latter elements are similar to the E motifs. The function of these elements has been demonstrated in planta (Chung, 1996).

Protein-binding studies showed that similar, seed-specific, or ABA-inducible protein factors bind to the PPR and the DPR. Competition DNA-binding assays indicated that similar factors can bind to both the PPR and the DPR. Genes encoding these Dc3 promoter-binding factors (DPBF) were initially isolated from a sunflower (Helianthus annuus) immature seed library using a modified yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) one-hybrid system (Kim et al., 1997; Kim and Thomas, 1998). The factors, referred to as DPBF-1, -2, and -3, are basic Leu zipper (bZIP) proteins and interact not only with the PPR but also with individual E motifs and the DPR. Recently, four homologs of the sunflower DPBFs were isolated from young Arabidopsis plants under stress conditions (Choi et al., 2000). These factors, named ABA-responsive element binding factors (ABFs), are similar to the DPBFs in their basic regions, and their expression is inducible by ABA and various stress treatments. In addition, cloning and analysis of the ABA-insensitive gene ABI5 showed that it encodes a bZIP transcription factor that shared extensive sequence identity with the sunflower DPBFs.

To further explore these novel transcription factors, we isolated the Arabidopsis DPBF homologs expressed in seeds. These are hereafter referred to as AtDPBFs. We showed that five distinct AtDPBFs are expressed in Arabidopsis seeds in addition to the previously described ABFs and ABRE-binding proteins (AREBs) expressed in ABA-treated seedlings (Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000). One of them (AtDPBF-1) is inducible by ABA in vegetative tissues. It is noteworthy that AtDPBF-1 is identical to ABI5 (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000).

RESULTS

Five AtDPBF Genes Are Expressed in Seeds

A cDNA library prepared from immature Arabidopsis seed mRNA was screened with DNA probes corresponding to the basic regions of sunflower DPBFs. From a screen of 650,000 recombinant phage plaques, nine positives were isolated with the sunflower DPBF-1 probe. Sequence analysis showed that two of them encoded an open reading frame composed of 442 amino acid (aa) residues. It is noteworthy that AtDPBF-1 is identical to the ABA-insensitive gene ABI5 (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000). The remaining seven clones all encoded a different protein composed of 331 aa. Because the DPBF-2 and -3 basic regions are identical but differ in their Leu zipper regions, mixtures of their bZIP regions were used in a second screen. More than 130 positives were identified, among which 14 random clones were sequenced. Seven of these encoded a protein containing 297 aa residues, and the other seven encoded a 262-aa protein. An additional round of screening performed much later with the sunflower DPBF-2 and -3 bZIP region probes led to the isolation of a fifth gene encoding a 449-aa bZIP protein. The predicted amino acid sequences of the basic domain and the Leu zipper region of the AtDPBFs, ABFs (Choi et al., 2000), and AREBs (Uno et al., 2000) are shown in Figure 1A.

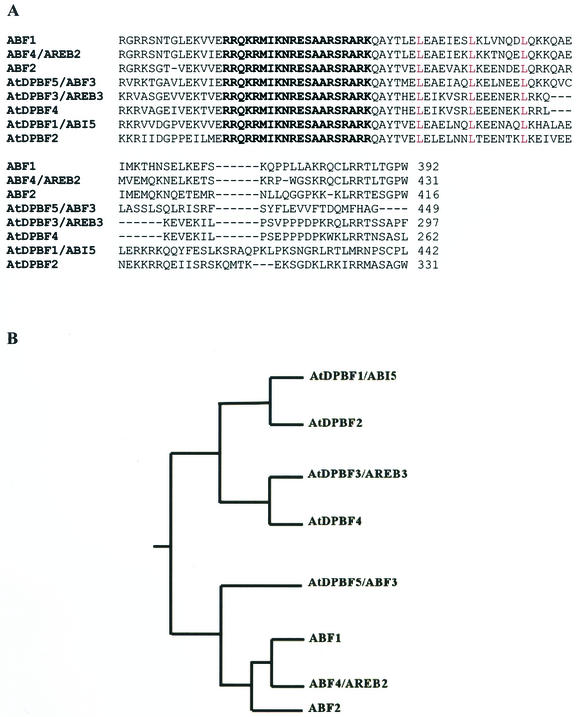

Figure 1.

Alignment and sequence relationships of the ABI5 subfamily members. A, Deduced amino acid sequences of ABI5 subfamily members were aligned with ClustalW (http://clustalw.genome.ad.jp/); the aligned regions including the bZIP domain are shown. The basic domains are in bold, and the Leu residues defining the Leu zipper are in red. B, Sequence relationships among the ABI5 bZIP subfamily. Results of ClustalW were used to generate the dendrogram. ABI5/AtDPBF-1, AC006921/AF334206; AtDPBF-2, AF334207; AtDPBF-3/AREB3, AF334208/AB017162; AtDPBF-4, AF334209; AtDPBF-5/ABF3, AF334210/AF093546; ABF1, AF093544; ABF2/AREB1, AF093545/AB017160; ABF3, AF093546; ABF4/AREB2, AF093547/017161.

Further analysis revealed that in addition to the identity of AtDPBF-1 and ABI5, AtDPBF-3 and AREB3 are identical as are AtDPBF-5 and ABF3. ABF4 is also identical to AREB2. The sequence relationships of these bZIPs as determined by ClustalW (http://clustalw.genome.ad.jp/) are illustrated in Figure 1B. These eight genes comprise what we call the ABI5 bZIP subfamily because ABI5 is the prototypical gene of this subfamily based on the extent of its functional definition at the molecular genetic and physiological level. It is interesting that all but one of the seed-expressed AtDPBFs fall in one cluster in the dendrogram and all but one of the ABI5 subfamily members expressed in seedlings fall in a second cluster.

The overall structure of AtDPBFs is very similar to that of sunflower DPBFs and ABFs. bZIP regions are located near C termini and Leu repeats are relatively short (Fig. 1A). The basic domain amino acid sequences of the AtDPBFs, ABFs, and AREBs are identical except for one conservative substitution (i.e. Lys to Arg) in AtDPBF-2. The first two Leu repeat regions are also highly conserved between sunflower and Arabidopsis clones and also between all members of the ABI5 subfamily.

AtDPBFs are divergent from each other and from ABFs outside their bZIP regions. However, there are short regions that are highly conserved among ABI5 bZIP subfamily members. These regions (not shown) contain two or three potential phosphorylation sites (Kemp and Pearson, 1990). For example, a calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation site (X-R-X-X-S-X) is conserved in all five AtDPBFs. A CKII phosphorylation site (T/S-X-X-D/E) and a PKC phosphorylation site (S-X-K/R) are also present. These phosphorylation sites are also highly conserved in sunflower DPBFs (Kim and Thomas, 1998) and suggest that phosphorylation events may play an important role in regulating DPBF function(s).

Expression of AtDPBFs in Seeds

AtDPBF mRNA expression was investigated by RNA gel-blot analysis. Total RNAs were isolated from stems, silique coats, immature seeds (3–5 d after flowering [DAF]), seeds at 1 DAF, roots, leaves, and flowers, transferred to nylon membranes after electrophoresis, and hybridized with gene-specific probes. As shown in Figure 2A, AtDPBF-1/ABI5 hybridized most intensely with RNA from seeds, but there was detectable expression of AtDPBF-1/ABI5 in flowers. This latter result is consistent with previous results of Lopez-Molina and Chua (2000). Similarly, hybridization signals were detected only with immature seed RNAs for AtDPBF-2, -3, and -4, suggesting that expression of AtDPBF-1 to -4 is seed specific. AtDPBF-5 was isolated later in this study and consequently was not subjected to this analysis. However, based on the identities of AtDPBF-5 and ABF3 and AtDPBF-3 and AREB3 and the tissues from which ABF3 and AREB3 were isolated, AtDPBF-1, 3, and 5 no doubt are expressed/induced in vegetative tissues in addition to being expressed in seeds.

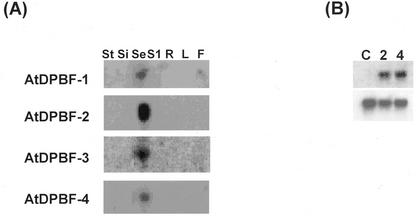

Figure 2.

Expression pattern of AtDPBFs. A, RNA gel blot analysis of AtDPBF transcripts. Ten micrograms of total RNA from various tissues was run on 1.2% (w/v) agarose/formaldehyde gels, transferred to nylon membranes, and hybridized with gene-specific probes. St, Stems; Si, silique coats; Se, 3- to 5-DAF seeds; S1, 1-DAF seeds; R, root; L, leaf; F, flower. B, ABA inducibility of AtDPBF-1. Poly(A+) RNA from ABA-treated Arabidopsis seedlings (1.5 μg) was run on an agarose/formaldehyde gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized to an AtDPBF-1 probe. The numbers indicate the duration of ABA treatment in hours. Probes, Upper, AtDPBF-1; lower, EF1α.

We tested ABA inducibility of AtDPBF expression. Two-week-old seedlings were treated with ABA, and AtDPBF expression was examined by RNA gel-blot analysis employing poly(A+) RNA. Under these conditions, no hybridization was detected even after ABA treatment with AtDPBF-2, -3, and -4 probes (not shown). However, hybridization was clearly detected with an AtDPBF-1/ABI5 probe after 2 and 4 h of ABA treatment (Fig. 2B). Thus, AtDPBF-1/ABI-5 is inducible by exogenous ABA in seedlings, whereas other AtDPBFs are not inducible under identical conditions. The results with AtDPBF-1/ABI-5 are consistent with the results of Finkelstein and Lynch (2000) and Lopez-Molina et al. (2001). Also, based on the identity of AtDPBF-5 and ABF3, it is likely that AtDPBF-5 is ABA inducible.

AtDPBFs Bind to the Dc3 Promoter

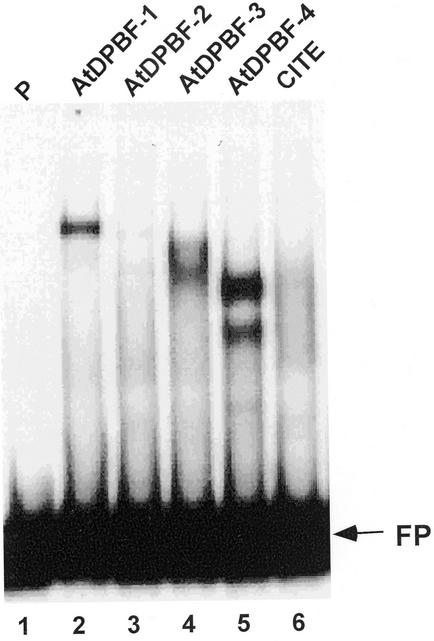

The near-perfect identity between Arabidopsis and sunflower DPBFs in their bZIP regions suggested that AtDPBFs would have binding specificity similar to the sunflower DPBFs. This was confirmed by in vitro binding assays. The coding regions of AtDPBF-1 to -4 were individually cloned into an in vitro expression vector, and AtDPBF proteins were prepared by coupled in vitro transcription/translation. Binding of each factor was then examined by an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) using the Dc3 PPR as a probe. A shifted band was detected with AtDPBF-1, -3, or -4 extracts (Fig. 3). In this experiment, a limited gel shift was observed with AtDPBF-2. This result demonstrates robust interactions of AtDPBF-1, -3, and -4 with the Dc3 gene promoter in vitro. It is noteworthy that AtDPBF-4 forms two shifted bands with the Dc3 promoter. This is possibly due to discrete interactions with two or more of the five binding sites present in this promoter.

Figure 3.

Binding of AtDPBFs to the Dc3 PPR in vitro. Binding of AtDPBFs was examined by a mobility shift assay employing in vitro translation products of AtDPBFs and Dc3 PPR as a probe. P, Probe only; FP, free probe; pCITE, in vitro translation product of the pCITE expression vector.

Dimerization of AtDPBFs

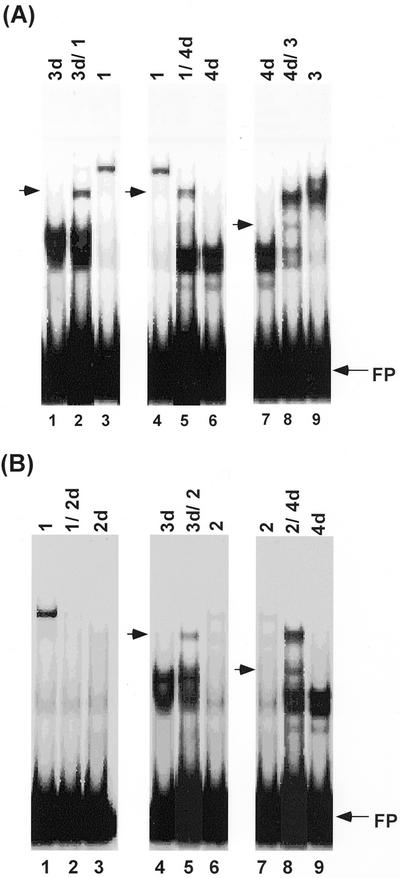

Previous work (Kim and Thomas, 1998) showed that heterodimer formation between sunflower DPBFs is selective. DPBF-2 can form a heterodimer with both DPBF-1 and -3, whereas no dimerization was observed between DPBF-1 and -3. Therefore, we investigated whether such selective heterodimerization was operative between AtDPBFs. First, we tested dimer formation between AtDPBFs that have demonstrable DNA-binding activity. AtDPBF-1 and -3, -1 and -4, or -3 and -4 were cotranslated, and the resulting extracts were employed in an EMSA using the Dc3 PPR as a probe. To distinguish between homo-and heterodimers, a set of constructs were made with short deletions in regions of the AtDPBFs outside of the bZIP regions; these deletions did not interfere with the binding characteristics of the AtDPBFs (Kim et al., 1997). When the cotranslation product of AtDPBF-1 and -3 was used in EMSA, a shifted band with a mobility between those of AtDPBF-1 and -3 was observed (Fig. 4A, lane 2). Similarly, a shifted band with an intermediate mobility was also detected using AtDPBF-1 and -4 (Fig. 4A, lane 5) or AtDPBF-3 and -4 (Fig. 4A, lane 8) cotranslation products. These results show that AtDPBF-1, -3, and -4 can form dimers interacting with the Dc3 PPR.

Figure 4.

Heterodimerization of AtDPBFs. Dimerization between AtDPBFs was examined by EMSAs, using cotranslation products of AtDPBFs and the Dc3 PPR. A, Dimerization between AtDPBF-1, -3, and -4. B, Dimerization between AtDPBF-2 and other AtDPBFs. Numbers above each lane indicate corresponding AtDPBFs. d, Deletion constructs of AtDPBFs (see text and “Materials and Methods”). Shifted bands with intermediate mobility are highlighted by arrows. FP, Free probe.

Similar experiments were performed using cotranslation products containing AtDPBF-2. As shown in Figure 4B (lane 2), no shifted band was observed when the extract prepared by cotranslation of AtDPBF-1 and -2 was employed, whereas a shifted band was detected with an extract containing only AtDPBF-1 in the same assay. This suggests that AtDPBF-1 and -2 can dimerize, but that the resulting heterodimer cannot bind to Dc3 PPR. The absence of a homodimer of AtDPBF-1 shifted band in lane 3 (Fig. 4B) is puzzling, but could be due to a stochiometric excess of AtDPBF-2 so that most of AtDPBF-1 is sequestered in heterodimers. AtDPBF-2 did form functional heterodimers with AtDPBF-3 and -4. A shifted band with a different mobility than AtDPBF-3 or -4 alone was observed in EMSA (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 8, respectively). Thus, AtDPBFs can form heterodimers between each other and these heterodimers have distinct DNA-binding activities.

Transcriptional Activity of AtDPBFs in Yeast

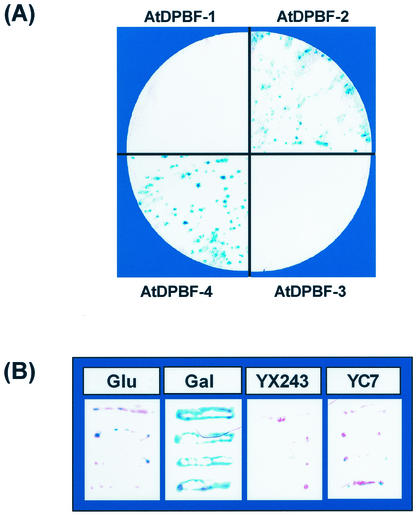

Transcriptional activity of AtDPBFs was tested using a yeast one-hybrid system (Li and Herskowitz, 1993). The coding regions of AtDPBFs were fused with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (Ma and Ptashne, 1987). These constructs were transformed into yeast (SFY526) harboring GAL4-binding sites fused upstream of a lacZ reporter gene. Thus, the reporter gene will be turned on if AtDPBFs have activation function in yeast. The result of a β-gala-ctosidase filter lift assay is presented in Figure 5A. No β-galactosidase activity was observed for colonies obtained after transformation with AtDPBF-1 or -3 fusion constructs, whereas in the same assay, colonies harboring AtDPBF-2 or -4 fusion constructs exhibited strong β-galactosidase activity, indicating that AtDPBF-2 and -4 can function as transcriptional activators in yeast.

Figure 5.

Transcriptional activation function of AtDPBFs. Individual AtDPBFs were fused to a GAL4 DNA-binding domain in a yeast expression vector pGBT9 and the resulting constructs were introduced into a yeast strain harboring a lacZ reporter gene fused to GAL4-binding sites. The reporter activity was monitored by a filter lift assay.

Our results so far showed that AtDPBF-4 has both DNA-binding and transcriptional activity, suggesting that it can turn on Dc3 expression by itself. We tested this hypothesis using the yeast transactivation assay. AtDPBF-4 was cloned into a yeast expression vector pYX243 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). This vector contains an inducible GAL1 promoter to drive foreign gene expression, in this case AtDPBF-4. This construct was introduced into a yeast reporter strain harboring a Dc3PPR-lacZ reporter. β-Galactosidase activity was measured by a filter lift assay. As shown in Figure 5B, strong β-galactosidase activity was observed with yeast colonies harboring AtDPBF-4 when grown on Gal media. Blue color development was much slower when the yeast transformants were grown on Glc plates. In control experiments, no activity was observed with the reporter construct missing the Dc3PPR or with the pYX243 vector only. This result shows that AtDPBF-4 can transactivate a Dc3PPR-containing reporter in yeast.

Transcriptional Activity of AtDPBF-1 in Plants

To further confirm the Dc3 gene promoter transactivation by AtDPBFs, we designed a chimeric promoter derived from the Dc3 PPR fused to the −90 cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S minimal promoter and a GUS reporter gene. Wild-type Arabidopsis plants were cotransformed with this reporter construct and AtDPBF-1 driven by the constitutive 35S CaMV promoter. GUS expression in seedlings was monitored by quantitative GUS assays (Table I). Although GUS expression was not totally silent in the absence of AtDPBF-1, there was a significant increase in GUS expression due to the presence of AtDPBF-1. The mean for three individual lines transformed with both the Dc3-derived promoter and AtDPBF-1 exhibited a 40-fold increase in GUS expression. Additional results using different promoters derived from the Dc3 PPR further validated the capability of AtDPBF-1 to transactivate the Dc3 promoter in planta (P. Perret and T.L. Thomas, unpublished data).

Table I.

AtDPBF-1 transactivates the Dc3 promoter in planta

| Construct | Average GUS Expression |

|---|---|

| −90CaMV35S::GUS | 0.0079 |

| −90CaMV35S::GUS + 35S::AtDPBF-1 | 0.0065 |

| Dc3 promoter::GUS | 0.0189 |

| Dc3 promoter::GUS + 35S::AtDPBF-1 | 0.7542 |

Seedlings of R2 transgenic plants expressing a minimal 35S promoter/GUS reporter with and without AtDPBF-1 and a chimeric promoter derived from the Dc3 PPR fused to the GUS reporter with and without AtDPBF-1 were assayed for GUS activity. The results are expressed in picomoles of 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronide per micrograms total protein per minute.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we reported the cloning of novel bZIP factors from sunflower interacting with seed specification and/or ABA-responsive elements in the lea gene promoter Dc3 (Kim et al., 1997; Kim and Thomas, 1998). In addition, homologs for DPBFs called ABF1–4 and AREBs were isolated from stress-treated Arabidopsis seedlings (Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000). Here, we report the isolation of five distinct Arabidopsis DPBFs (AtDPBFs) that are expressed as mRNA in Arabidopsis seeds. Thus, DPBFs are encoded by a small gene family both in Arabidopsis and sunflower. The properties of the AtDPBFs are summarized in Table II.

Table II.

Properties of AtDPBFs

| Properties | AtDPBF1 ABI5 | AtDPBF2 | AtDPBF3 AREB3 | AtDPBF4 | AtDPBF5a ABF3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 442 aa | 331 aa | 297 aa | 262 aa | 449 aa |

| ABA inducible | Yes | No | Possibleb | No | Yesc |

| Binding to PPR | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | N/Dd |

| Binding to DPR | Yes | No | Yes | No | N/D |

| Heterodimer | AtDPBF-3 and -4 | AtDPBF-3 and -4 | AtDPBF-1, -2, and -4 | AtDPBF-1, -2, and -3 | N/D |

| Transactivity in yeast | No | Yes | No | Yes | N/D |

AtDPBF-5 was cloned recently and all properties have not been investigated yet.

Based on conditions for cDNA library construction (Uno et al., 2000).

N/D, Not determined.

To date, a large number of bZIP proteins have been isolated from plants. With a few exceptions (de Pater et al., 1994; Yunes et al., 1994; Chern et al., 1996a), most of these plant bZIP proteins bind to cis-elements containing the ACGT core sequence, which is shown to be essential for their binding (Izawa et al., 1993; Foster et al., 1994). DPBFs can interact with the ACGT-containing, canonical G box sequence, like other bZIP proteins. However, they bind to cis-elements that do not have the ACGT core more strongly. The DPBF-binding sites within the Dc3 promoter can be represented by A/CCACNNG or ACACGNNN (Kim et al., 1997; Kim and Thomas, 1998). Thus, DPBFs have broader binding specificity than most other plant bZIP proteins.

Overall, the AtDPBFs are approximately 50% identical to corresponding sunflower DPBFs. The overall similarity between members of the ABI5 subfamily is within similar ranges. However, there are several regions that are highly conserved among all members of this subfamily (Fig. 1A). The basic DNA-binding regions are nearly identical, and the Leu zipper regions are also highly conserved. Three regions in the N-terminal side of the basic regions are also well conserved. These conserved regions contain potential phosphorylation sites. We speculate that these sites are important in modulating DPBF function, although their in vivo mechanism remains to be determined. Involvement of phosphorylation in transcription factor modulation is well established (Hunter and Karin, 1992). More specifically, phosphorylation is known to affect the binding activity of the maize (Zea mays) seed-specific factor O2 (Ciceri et al., 1997) and an Arabidopsis G box-binding factor GBF1 (Klimczak et al., 1992). Also, many studies show that phosphorylation is important in signaling steps of the ABA signal transduction pathways (Leung and Giraudat, 1998; Uno et al., 2000; Lopez-Molina et al., 2001).

The AtDPBFs are distinct from each other. They differ in their abundance, size, expression pattern, and DNA-binding and transcriptional activities (Table II). From the screen of 650,000 recombinant phage plaques, only two AtDPBF-1 clones were isolated, whereas seven isolates were obtained for AtDPBF-2. On the other hand, AtDPBF-3 and -4 were much more abundant; approximately 65 positives were identified for each. We do not know yet whether the difference in the number of isolates is due to differences in mRNA levels per se or due to temporal differences in expression pattern. RNA used in our library construction was prepared from immature seeds. Thus, AtDPBF-1 and -2 may be expressed in later stages of embryo development if the temporal expression pattern is different; thus, their expression level in young developing embryos may be lower than those of AtDPBF-3 and -4.

Our results show that AtDPBF-2 binds weakly to the Dc3 promoter in vitro, whereas other factors interact robustly with this promoter. This result is somewhat unexpected because the basic region of AtDPBF-2 is identical to the others. AtDPBF-1 and -2 are closely related and the difference in their bZIP regions is not readily apparent. It is possible that the nonpolar Thr residue at position e of the second Leu repeat and the Asn at the fourth Leu position of the zipper region are responsible for the limited binding of AtDPBF-2 to the Dc3 promoter. The e position is usually occupied by charged amino acids stabilizing dimer formation by providing salt bridges between monomeric units (Jelesarov et al., 1998). Also, the Asn residue might contribute to destabilize homodimer formation. However, AtDPBF-2 can form a functional heterodimer with other AtDPBFs, except AtDPBF-1. It is tempting to speculate that these subtle differences may be involved in modulating the function of AtDPBF-1/ABI5.

Our current study shows that AtDPBFs are seed-expressed transcription factors. In monocot plants, several bZIP factors that include the maize O2 (Schmidt et al., 1987; Hartings et al., 1989) and its homologous factors (Vettore et al., 1998) are known to be expressed specifically in seeds. These factors are usually expressed in endosperm and are involved in the regulation of storage protein genes. Few seed- or embryo-specific factors with known DNA-binding activity have been reported in dicot plants. ABI3, an Arabidopsis transcriptional activator isolated by positional cloning (Giraudat et al., 1992), is seed specific and affects expression of many seed-specific genes. However, its DNA-binding activity has not been clearly demonstrated. Two bZIP proteins, ROM1 and ROM2, are also seed specific, but they function as repressors rather than activators (Chern et al., 1996a, 1996b). Involvement of seed-specific activators that bind to the G box or its related sequences, however, was suggested by several studies (Lam and Chua, 1991; Bobb et al., 1997) in dicots. AtDPBF-2 and -4 are excellent candidates to function as seed-specific developmental regulators because they appear to be seed specific and interact with embryo specification elements (Kim and Thomas, 1998).

The regulatory elements to which AtDPBFs bind are not only involved in seed-specific expression, but also in ABA-induced expression of the Dc3 gene. Thus, AtDPBFs have the potential to mediate ABA induction as well. In our ABA induction experiment, AtDPBF-1 was inducible by exogenous ABA, suggesting the possible involvement of AtDPBF-1 in mediating the ABA response in vegetative tissues. The Arabidopsis gene ABI5 was isolated by positional cloning (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000). Subsequent sharing of unpublished sequences before this publication revealed that the AtDPBF1 isolated in our laboratory is identical to ABI5. This observation confirms the implication of AtDPBF-1 in ABA-regulated pathways, and recent work demonstrated that ABI5 is highly regulated by ABA (Lopez-Molina et al., 2001). Because of their similar properties, it is possible that the remaining AtDPBFs also function in ABA signaling.

There are many possible ways of regulating AtDPBF activities and, thus, expression of their target genes in Arabidopsis. As mentioned above, phosphorylation may be one of the factors regulating individual AtDPBF function. Control of spatial and temporal expression may be another factor. Heterodimerization is yet another way to regulate the activity of AtDPBFs. Only AtDPBF-4 exhibited both DNA-binding and transcriptional activities in our assays. The other AtDPBFs do not appear to be able to activate target genes by themselves in vitro. However, we showed that AtDPBF-1 was able to transactivate a Dc3-derived promoter when constitutively expressed in transgenic plants. This result suggests that additional partners, or modifications, are required in vivo for the exposure or activation of critical AtDPBF domains as suggested by previously documented trans-activation by the N-terminal region of ABI5/AtDPBF-1 (Nakamura et al., 2001). It is particularly tantalizing to speculate that phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of ABI5 could play a role in each of these other functions. In addition, several different combinations of activities could be generated using AtDPBF heterodimers and may provide differential DNA-binding and transcriptional activity not possible with individual factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA Manipulation

Standard techniques were used for the manipulation of DNA (Sambrook et al., 1989; Ausubel et al., 1994). Sequence analysis was carried out using DNA Strider, GeneWorks (Intelligenetics, Oxford Molecular Group, Oxford), and various applications in the Baylor College of Medicine search launcher (http://kiwi.imgen.bcm.tmc.edu).

Isolation of AtDPBF cDNAs

RNA isolation from immature seeds and other tissues, poly(A+) RNA selection, and construction of immature seed cDNA library using the lambda ZAP II vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) were described previously (Li and Thomas, 1998). Probe DNA fragments were prepared by PCR, using the following primer sets flanking the basic regions of sunflower (Helianthus annuus) DPBFs (Kim and Thomas, 1998): DPBF-1 probe, 5′-GCTACCACTCAGCTCGAT-3′ and 5′-TTGACACTTTGTCACACC-3′; DPBF-2 probe, 5′-ATGGGTAGTTTATCGGAC and 5′-ACCGCTGACCAGATTAGC-3′; and DPBF-3 probe, 5′-GGATATGGTTTATCCGG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCTACATAACATACT-3′

Radioactive probes were prepared by the random hexamer labeling method using 32P-dATP and gel-purified DNA fragments.

Recombinant phage (6.5 × 105) were plated at a density of 5 × 104 [supi] per plate and grown for 7 h at 37°C. Two sets of replica filters (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) were prepared (Ausubel et al., 1994). One set of the filters was hybridized with the radioactive DPBF-1 probe; the second set was hybridized with mixtures of DPBF-2 and -3 probes. In brief, filters were prehybridized for 3 h in 130 mL of solution II (1% [w/v] bovine serum albumin, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5 m sodium phosphate [pH 7.2], and 7% [w/v] SDS) at 50°C. 32P-Labeled probes (1–2 × 108 cpm) were added and hybridization was continued further for 30 h at the same temperature. After hybridization, filters were washed for 15 min at 50°C in 500 mL of high-wash buffer (1 mm EDTA, 40 mm sodium phosphate [pH 7.2], and 1% [w/v] SDS) twice. Positive plaques were identified by autoradiography.

Northern-Blot Analysis

RNA isolation from various tissues has been described elsewhere (Li and Thomas, 1998). For the ABA inducibility experiment, seeds were germinated and grown on Murashige and Skoog media (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) containing 0.2% (w/v) gelite for 2 weeks. For ABA treatment, seedlings were transferred to liquid media with or without 100 μm ABA (mixed isomers from Sigma, St. Louis) and incubated at room temperature for 2 or 4 h with gentle shaking. Seedlings were rinsed with water and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNAs were isolated (Chomczinsky and Mackey, 1995), and poly(A+) RNA was selected using Oligotex resin (Qiagen USA, Valencia, CA). For northern blots, 1 to 5 μg of poly(A+) RNA from each sample was separated on a 1.2% (w/v) agarose-formaldehyde gel and transferred to a nylon membrane (Micron Separations, Westborough, MA). Hybridization and washing of filters were performed as described (Li and Thomas, 1998). cDNA fragments outside the bZIP regions were used as gene specific probes and a β-tubulin gene fragment was used as a loading control.

Plasmid Constructs

For in vitro transcription/translation, AtDPBF coding regions were cloned into pCITE vectors (Novagen, Madison, WI). pCITE-AtDPBF-1 was constructed by cloning a NcoI-XhoI fragment into the corresponding restriction sites of pCITE-4a. To construct pCITE-AtDPBF-2 and pCITE-AtDPBF-4, coding regions were amplified by PCR using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). The amplified fragments were digested with NcoI and cloned into NcoI-HincII sites of pCITE-4c. pCITE-AtDPBF-3 was prepared by cloning the PCR-amplified coding region into the EcoRV site of pCITE-4a. Integrity of the junction sequence for each construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The deletion constructs used for dimerization experiments were prepared by excising NcoI-HincII (AtDPBF-2 and -4 constructs) or NdeI-NcoI fragments (AtDPBF-4) from individual CITE constructs. Resulting fragments were filled in with Klenow and self-ligated.

Plasmids used for transcriptional activation assays were prepared by cloning a HincII-XhoI fragment of AtDPBF-1 into the SmaI-SalI sites of pGBT9 (CLONTECH Laboratories, Palo Alto, CA). To prepare the constructs containing other AtDPBFs, entire coding regions were PCR amplified and cloned into pGBT9 after BamHI digestion and Klenow fill-in reaction.

Binary plasmids used for plant transformation were constructed by cloning a BamHI-XbaI PCR fragment derived from the Dc3 promoter into the pBIN19.90 vector, obtained by inserting a CaMV −90.35S (−90 to +8)::GUS fusion into the pBIN19 binary vector (Bevan, 1984). An EcoRI/XhoI fragment of AtDPBF-1 cDNA was cloned into the pCam1201 vector (Cambia, Canberra, Australia).

In Vitro Transcription/Translation and DNA-Binding Assay

Extracts containing individual AtDPBFs were prepared by coupled in vitro transcription/translation employing 1 μg of each AtDPBF construct and the TNT Kit (Promega, Madison, WI). EMSAs were performed as previously described (Kim et al., 1997).

Transcriptional Activation Assay

Transcriptional activation in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) was performed as described (Kim et al., 1997). Similar numbers of yeast transformants containing each pGBT9-AtDPBF construct were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and β-galactosidase activity was measured by filter lift assay (Breeden and Nasmyth, 1985).

In Planta Transactivation by AtDPBF-1/ABI5

Wild-type Arabidopsis was transformed according to standard described procedures with just the reporter constructs or a mixture of the activator and reporter constructs in Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Bechtold et al., 1993; Clough and Bent, 1998). For plants transformed with both activator and reporter constructs, transformants were selected by plating bleach-sterilized seeds on Murashige and Skoog plates containing 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin, 20 μg mL−1 hygromycin, and 500 μg mL−1 carbenicillin. A second round of selection for R1 seeds was carried out on Murashige and Skoog-kanamycin/hygromycin plates. Seeds expressing the reporter constructs were selected on Murashige and Skoog plates containing 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin and 500 μg mL−1 carbenicillin (R0) or 50 μg mL−1 kanamycin (R1 and R2).

Enzymatic assays of GUS activity with 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-d-glucuronide were performed as described (Jefferson et al., 1987). Protein concentration for each sample was determined by a Bradford assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard (Bradford, 1976). Three to five individual lines were analyzed for each construct and there were four plants within each line.

Distribution of Materials

All novel materials, unfettered by third party restrictions, described in this publication will be made available expeditiously for noncommercial research purposes.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative (grant nos. 94–37304–1228 and 97–35304–4552) and by RhoBio, a joint venture between Aventis Crop Science and Biogemma.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.003566.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R, Moore D, Seidman J, Smith J, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Green Publishing Associates/Wiley Interscience; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold N, Ellis J, Pelletier G. In planta Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. C R Acad Sci Paris Life Sci. 1993;316:1194–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan M. Binary Agrobacterium vectors for plant transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:8711–8721. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.22.8711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobb A, Chern MS, Bustos M. Conserved RY-repeats mediate transactivation of seed-specific promoters by the developmental regulator PvALF. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:641–647. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.3.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of proteins utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeden L, Nasmyth K. Regulation of the yeast HO gene. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1985;50:643–650. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1985.050.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler P, Robertson M. Gene expression regulated by abscisic acid and its relation to stress tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mo Biol. 1994;45:113–141. [Google Scholar]

- Chern MS, Bobb A, Bustos M. The regulator of MAT2 (ROM2) protein binds to early maturation promoters and represses PvALF-activated transcription. Plant Cell. 1996a;8:305–321. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chern MS, Eiben HG, Bustos MM. The developmentally regulated bZIP factor ROM1 modulates transcription from lectin and storage protein genes in bean embryos. Plant J. 1996b;10:135–148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.10010135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Hong J, Ha J, Kang J, Kim SY. ABFs, a family of ABA-responsive element binding factors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1723–1730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczinsky P, Mackey K. Short technical reports: modification of the TRI reagent procedure for isolation of RNA from polysaccharide- and proteoglycan-rich sources. Biotechniques. 1995;19:942–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HJ. Analysis of 5′ upstream region of the carrot Dc3 gene: bipartite structure of the Dc3 promoter for embryo-specific expression and ABA-inducible expression. PhD thesis. College Station: Texas A&M University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ciceri P, Gianazza E, Lazzari B, Lippoli G, Genga A, Hoschek G, Schmidt RJ, Viotti A. Phosphorylation of Opaque2 changes diurnally and impacts its DNA binding activity. Plant Cell. 1997;9:97–108. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S, Bent A. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pater S, Katagiri F, Kijne J, Chua NH. bZIP proteins bind to a palindromic sequence without an ACGT core located in a seed-specific element of the pea lectin promoter. Plant J. 1994;6:133–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6020133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dure L., III A repeating 11-mer amino acid motif and plant desiccation. Plant J. 1993;3:363–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1993.t01-19-00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dure L, III, Crouch M, Harada J, Ho TH, Mundy J, Quatrano R, Thomas T, Sung Z. Common amino acid sequence domains among the LEA proteins of higher plants. Plant Mol Biol. 1989;12:475–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00036962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R, Lynch T. The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response gene ABI5 encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Plant Cell. 2000;12:599–609. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.4.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster R, Izawa T, Chua NH. Plant bZIP proteins gather at ACGT elements. FASEB J. 1994;8:192–200. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.2.8119490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudat J, Hauge B, Valon C, Smalle J, Parcy F, Goodman H. Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1251–1261. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartings H, Maddaloni M, Lazzaroni N, DiFonzo N, Motto M, Salamini F, Thompson R. The O2 gene which regulates zein deposition in maize endosperm encodes a protein with structural homologies to transcriptional activators. EMBO J. 1989;8:2795–2801. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Galau G. Developmental and environmental induction of Lea and LeaA mRNAs and the postabscission program during embryo culture. Plant Cell. 1991;3:605–618. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.6.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T, Karin M. The regulation of transcription by phosphorylation. Cell. 1992;70:375–387. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J, Bartels D. The molecular basis of dehydration tolerance in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:377–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa T, Foster R, Chua NH. Plant bZIP protein DNA binding specificity. J Mol Biol. 1993;230:1131–1144. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson R, Kavanagh T, Bevan M. GUS fusions: β-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 1987;6:3901–3907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelesarov I, Durr E, Thomas R, Bosshard H. Salt effects on hydrophobic interaction and charge screening in the folding of a negatively charged peptide to a coiled coil (Leucine zipper) Biochemistry. 1998;37:7539–7550. doi: 10.1021/bi972977v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp B, Pearson R. Protein kinase recognition sequence motifs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:342–346. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90073-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Chung HJ, Thomas TL. Isolation of a novel class of bZIP transcription factors that interact with ABA-responsive elements and embryo-specification elements in the Dc3 promoter using a modified yeast one-hybrid system. Plant J. 1997;11:1237–1251. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.11061237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Thomas TL. A family of basic leucine zipper proteins bind to seed-specification elements in the carrot Dc3 gene promoter. J Plant Physiol. 1998;152:607–613. [Google Scholar]

- Klimczak L, Schindler U, Cashmore A. DNA binding activity of the Arabidopsis G-box binding factor is stimulated by phosphorylation by caseine kinase II from broccoli. Plant Cell. 1992;4:87–98. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam E, Chua NH. Tetramer of a 21-base pair synthetic element confers seed expression and transcriptional enhancement in response to low water stress and abscisic acid. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17131–17135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J, Giraudat J. Abscisic acid signal transduction. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:199–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Herskowitz I. Isolation of ORC6, a component of the yeast origin recognition complex by a one-hybrid system. Science. 1993;262:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.8266075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Thomas T. PEI1, an embryo-specific zinc finger protein gene required for heart-stage embryo formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1998;10:383–398. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Molina L, Chua NH. A null mutation in a bZIP factor confers ABA-insensitivity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:541–547. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, Chua NH. A postgermination developmental arrest checkpoint is mediated by abscisic acid and requires the ABI5 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4782–4787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081594298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Ptashne M. Deletion analysis of GAL4 defines two transcriptional activating segments. Cell. 1987;48:847–853. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Lynch TJ, Finkelstein RR. Physical interactions between ABA response loci of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2001;26:627–635. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parcy F, Valon C, Raynal M, Gaubier-Comella P, Delseny M, Giraudat J. Regulation of gene expression programs during Arabidopsis seed development: roles of the ABI3 locus and of endogenous abscisic acid. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1567–1582. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.11.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R, Burr F, Burr B. Transposon tagging and molecular analysis of the maize regulatory locus opaque-2. Science. 1987;238:960–963. doi: 10.1126/science.2823388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seffens W, Almoguera C, Wilde H, Haar R, Thomas T. Molecular analysis of a phylogenetically conserved carrot gene: developmental and environmental regulation. Dev Genet. 1990;11:65–76. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020110108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui NU, Chung HJ, Thomas TL, Drew MC. Abscisic acid- dependent and -independent expression of carrot LEA-class gene Dc3 in transgenic tobacco seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1181–1190. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skriver K, Mundy J. Gene expression in response to abscisic acid and osmotic stress. Plant Cell. 1990;2:503–512. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.6.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T, Chung HJ, Nunberg A. ABA signaling in plant development and growth. In: Aducci P, editor. Signal Transduction in Plants. Basel: Birkhaeuser Verlag; 1997. pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas TL. Gene expression during plant embryogenesis and germination: an overview. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1401–1410. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.10.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno Y, Furihata T, Abe H, Yoshida R, Shinozaki K. Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper transcription factors involved in an abscisic acid-dependent signal transduction pathway under drought and high-salinity conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11632–11637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190309197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vettore A, Yunes J, Cord Neto G, da Silva M, Arruda P, Leite A. The molecular and functional characterization of an Opaque2 homologue gene from Coix and a new classification of plant bZIP proteins. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;36:249–263. doi: 10.1023/a:1005995806897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivekananda J, Drew MC, Thomas TL. Hormonal and environmental regulation of the carrot lea-class gene Dc3. Plant Physiol. 1992;100:576–581. doi: 10.1104/pp.100.2.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde H, Nelson W, Booij H, de Vries S, Thomas TL. Gene-expression programs in embryonic and non-embryonic carrot cultures. Planta. 1988;176:205–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00392446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Duan X, Wang B, Hong B, Ho TH, Wu R. Expression of a late embryogenesis abundant protein gene, HVA1, from barley confers tolerance to water deficit and salt stress in transgenic rice. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:249–257. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.1.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunes J, Cord Neto G, da Silva M, Leite A, Ottoboni L, Arruda P. The transcriptional activator Opaque2 recognizes two different target sequences in the 22-kd-like α-prolamin genes. Plant Cell. 1994;6:237–249. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]