Abstract

Using a combination of protein isolation/characterization and molecular cloning, we have demonstrated that the bark of the black mulberry tree (Morus nigra) accumulates large quantities of a galactose-specific (MornigaG) and a mannose (Man)-specific (MornigaM) jacalin-related lectin. MornigaG resembles jacalin with respect to its molecular structure, specificity, and co- and posttranslational processing indicating that it follows the secretory pathway and eventually accumulates in the vacuolar compartment. In contrast, MornigaM represents a novel type of highly active Man-specific jacalin-related lectin that is synthesized without signal peptide or other vacuolar targeting sequences, and accordingly, accumulates in the cytoplasm. The isolation and cloning, and immunocytochemical localization of MornigaG and MornigaM not only demonstrates that jacalin-related lectins act as vegetative storage proteins in bark, but also allows a detailed comparison of a vacuolar galactose-specific and a cytoplasmic Man-specific jacalin-related lectin from a single species. Moreover, the identification of MornigaM provides the first evidence, to our knowledge, that bark cells accumulate large quantities of a cytoplasmic storage protein. In addition, due to its high activity, abundance, and ease of preparation, MornigaM is of great potential value for practical applications as a tool and bioactive protein in biological and biomedical research.

Many flowering plants from diverse taxonomic groups accumulate large quantities of so-called vegetative storage proteins (VSPs) in various vegetative storage organs. These VSPs play a primary role in nitrogen accumulation, storage, and distribution in biennial and perennial plants, and, accordingly, are believed to contribute to the survival of the plant in its natural environment (Staswick, 1994). Moreover, some VSPs with a particular enzymatic or other biological activity act as aspecific defense proteins against herbivorous animals or phytophagous invertebrates, for example, and hence may play a dual storage/defense role (Peumans and Van Damme, 1995; Yeh et al., 1997).

The concept of functional “vegetative” homologs of the classic seed storage proteins was originally developed for two proteins, called VSPα and VSPβ, that accumulate in large quantities in soybean (Glycine max) leaves, seed pods, and hypocotyls forced to act as a nitrogen sink (Staswick, 1989a, 1989b). However, it is evident that the term VSP also applies to the previously identified major tuber proteins from potato (Solanum tuberosum; patatin, Mignery et al., 1984) and sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas; sporamin, Maeshima et al., 1985), as well as to all other abundant proteins found in various vegetative storage organs like bulbs, tubers, and rhizomes. VSPs are also common in the bark of deciduous trees. Studies with poplar (Populus deltoides; Coleman et al., 1991), elderberry (Sambucus nigra; Nsimba-Lubaki and Peumans, 1986), and several legume trees not only demonstrated the occurrence of abundant bark-specific VSPs, but also led to the identification of some of these bark VSPs.

All bark VSPs identified thus far are carbohydrate-binding proteins (lectins) or are closely related homologs devoid of carbohydrate-binding activity. Most of these lectins or lectin-related proteins have been found in legume trees and belong to the family of legume lectins. Well-known examples are the abundant lectins in the bark of yellow wood (Cladrastis lutea; Van Damme et al., 1995a), Maackia amurensis (Van Damme et al., 1997b), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia; Van Damme et al., 1995c), and Japanese pagoda tree (Sophora japonica; Hankins et al., 1988; Van Damme et al., 1997a). In contrast, the abundant bark lectins found in elderberry and other Sambucus species (Nsimba-Lubaki et al., 1986) belong to the family of type-2 ribosome-inactivating proteins, which are structurally and evolutionarily unrelated to the legume lectins (Van Damme et al., 1998). Thus far, no representatives of any of the other five lectin families (i.e. the amaranthins, the chitin-binding lectins comprising hevein domains, the Cucurbitaceae phloem lectins, the jacalin-related lectins [JRLs], and the monocot Man-binding lectins) have been identified as bark-specific VSPs (Van Damme et al., 1998). The apparent absence of these lectin families from bark is somewhat surprising because numerous monocot Man-binding lectins, several jacalins, and some chitin-binding lectins are abundant VSPs in bulbs, tubers, or rhizomes (Van Damme et al., 1998). To corroborate the possible occurrence of abundant bark lectins other than legume lectins or type-2 ribosome-inactivating proteins, several Moraceae species were checked for the presence of bark-specific JRLs. Thereby, it was observed that the bark of the black mulberry (Morus nigra) tree accumulates high concentrations of a Gal- and a Man-specific JRL.

It should be mentioned here that at present, the family of JRLs is subdivided into Gal- and Man-specific agglutinins (Van Damme et al., 1998; Peumans et al., 2000a). Jacalin and its Gal-specific homologs are made up of four identical protomers each consisting of a heavy (α) and a light (β) polypeptide chain. Both chains are derived from a large preproprotein through a complex co- and posttranslational processing, but they remain together by noncovalent interactions. Jacalin follows the secretory pathway and eventually accumulates in storage protein vacuoles (Peumans et al., 2000a). Hitherto, Gal-specific homologs of jacalin have exclusively been found in seeds of Artocarpus species (Moreira and Ainouz, 1981) and Osage orange (Maclura pomifera; Bausch and Poretz, 1977), indicating that the Gal-specific JRLs are confined to a small taxonomic group. The Man-specific JRLs consist of two, four, or eight “intact” protomers. They are synthesized and located in the cytoplasm and undergo no co- or posttranslational proteolytic modification (Peumans et al., 2000a). Man-specific JRLs have been isolated from species belonging to a wide range of taxonomic groups, including hedge bindweed (Calystegia sepium, family Convolvulaceae; Van Damme et al., 1996; Peumans et al., 1997), Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus, family Asteraceae; Van Damme et al., 1999), jack fruit (Artocarpus integrifolia, Moraceae; Rosa et al., 1999), rice (Oryza sativa, family Gramineae; Zhang et al., 2000), banana (Musa acuminata, family Musaceae; Peumans et al., 2000b), Japanese chestnut (Castanea crenata, family Fagaceae; Nomura et al., 2000), Parkia platycephala (family Fabaceae; Mann et al., 2001), and oilseed rape (Brassica napus, Brassicacea) plants (Geshi and Brandt, 1998). At present, the exact relationships between the two subfamilies of JRLs are still unclear because thus far no detailed study was made of a Gal- and a Man-specific JRL from a single species. Therefore, the fortunate presence of large quantities of a Gal- and a Man-specific lectin in mulberry bark offered a unique opportunity to corroborate the structural, functional, and evolutionary relationships between the two distinct subfamilies of the JRLs.

This paper describes the isolation, characterization, molecular cloning, and subcellular localization of two very abundant bark lectins from the black mulberry tree. One of these lectins is a Gal-specific JRL (called black mulberry tree agglutinin G or MornigaG), whereas the other is a Man-specific homolog (called black mulberry tree agglutinin M or MornigaM). Our results not only unambiguously demonstrate the occurrence of JRLs in bark, but they also provide for the first time, to our knowledge, evidence for the presence of an abundant cytoplasmic VSP in bark.

RESULTS

The Bark of the Black Mulberry Tree Contains Large Quantities of a Mixture of Two Different Lectins

Crude extracts from the bark of the black mulberry tree exhibited a titer >500,000 in agglutination tests with trypsin-treated rabbit erythrocytes, indicating that the black mulberry bark has an unusually high lectin content. SDS-PAGE further demonstrated that the most abundant bark proteins correspond to a set of polypeptides with an Mr of approximately 16 kD (Fig. 1, lane 4). Because this Mr is reminiscent to that of jacalin, it was checked whether black mulberry bark contains one or more vegetative homolog(s) of the seed-specific Artocarpus lectins. Hapten inhibition assays demonstrated that the agglutination activity of the black mulberry bark was, unlike that of jacalin, not abolished by Gal. To find out whether black mulberry tree bark contains a lectin with a different specificity or possibly a mixture of two or more lectins with a different specificity, the hapten inhibition assays were extended with a series of simple sugars and equimolar mixtures of different combinations of two simple sugars. No simple sugar caused a visible effect on the agglutination activity of the crude extract, but a mixture of 50 mm methyl α-d-galactopyranoside and 50 mm methyl α-d-mannopyranoside yielded a complete inhibition, indicating that the bark contains a mixture of Man-specific and Gal-specific lectins.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE of crude extracts and purified lectins from black mulberry tree and jack fruit. Samples were loaded as follows: lane 1, crude extract from black mulberry tree seeds; lane 2, purified MornigaG; lane 3, crude extract from black mulberry tree summer bark; lane 4, crude extract from black mulberry tree winter bark; lane 5, MornigaG; lane 6, MornigaM; lane 7, KM+; lane 8, jacalin; and lane 9, crude extract from jack fruit seeds. Extracts loaded in lanes 3 and 4 were made from equal amounts of frozen bark tissue (and hence reflect the in situ protein concentration and composition). All samples were reduced with β-mercaptoethanol. Molecular mass reference proteins (lane R) were lysozyme (14 kD), soybean trypsin inhibitor (20 kD), carbonic anhydrase (30 kD), ovalbumin (43 kD), bovine serum albumin (67 kD), and phosphorylase b (94 kD).

MornigaG and MornigaM could be completely resolved from the lectin mixture by consecutive affinity chromatography on immobilized Gal and Man, respectively. The total yield was approximately 8 mg MornigaG and 16 mg MornigaM g−1 dry bark meal (containing approximately 30 mg total soluble protein g−1). In accordance with this, MornigaG and MornigaM account for roughly 26.7% and 53.3%, respectively, of the soluble bark protein.

Molecular Structure of MornigaG and MornigaM

To determine the molecular structure of MornigaG and MornigaM the affinity-purified lectins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, mass spectrometry, and gel filtration. MornigaG migrated as a single polypeptide of approximately 16 kD upon SDS-PAGE, irrespective of whether the protein was reduced with β-mercaptoethanol (Fig. 1, lane 5). Mass spectrometry revealed the presence of a single small polypeptide of 2,175 D and a mixture of seven polypeptides with a molecular mass ranging between 15,776 and 16,032 D (15,776; 15,786; 15,811; 15,828; 15,976; 15,992; and 16,032 D, respectively). Mass spectrometry/fragmentation of the small peptide yielded a sequence of 12 residues (IVVGTWGAQVTS), which shares high sequence identity with the β-chain of jacalin (Yang and Czapla, 1993). Sequencing of the 16-kD polypeptide by Edman degradation yielded 20 residues (GVAFDDGAYTGIREINFEYN), reminiscent of the N terminus of the α-chain of jacalin (Yang and Czapla, 1993). Native MornigaG eluted with an apparent Mr of approximately 60 kD from a Superose 12 gel filtration column (using jacalin as a Mr marker). These findings suggested that native MornigaG is, like jacalin, a tetramer composed of four protomers consisting of a short β- and a long α-chain. Sugar determination by the phenol/H2SO4 acid method indicated that MornigaG contains approximately 6% covalently bound carbohydrate. Because this value corresponds to six monosaccharide units per 16 kD polypeptide, it can be concluded that MornigaG contains one N-glycan per protomer.

MornigaM migrated as a doublet of 15- to 16-kD polypeptides upon SDS-PAGE, irrespective whether the protein was reduced with β-mercaptoethanol (Fig. 1, lane 6). Mass spectrometry yielded two values (16,320 and 16,898 D), indicating that the lectin is a mixture of two slightly different forms. Native MornigaM eluted with an apparent Mr of approximately 60 kD from a Superose 12 gel filtration column (using jacalin as a Mr marker). No covalently bound carbohydrate could be detected in MornigaM preparations by the phenol/H2SO4 acid method, indicating that the lectin is not glycosylated. Sequencing of the electroblotted 16-kD polypeptides of MornigaM yielded a very weak signal, indicating that the bulk of the protein is N-terminally blocked. Despite the weak signal, the sequence TQSTGTSQTIAVGLWGGPGGNAWD could be determined. Because this sequence shares a high identity with residues 1 through 19 of KM+ (Rosa et al., 1999), it seems likely that the 16-kD polypeptides of MornigaM are homologs of the KM+ subunit in Artocarpus seeds. Our analytical data indicate that MornigaM is like KM+ (Misquith et al., 1994), a homotetramer composed of four protomers each consisting of a single nonglycosylated 16-kD polypeptide.

Agglutination Activity and Carbohydrate-Binding Specificity of MornigaG and MornigaM

MornigaG and MornigaM are powerful hemagglutinins. The specific agglutination activity (defined as the minimal concentration required for a visible agglutination) of MornigaG was 2.5 and 3.3 ng mL−1 with rabbit and human red blood cells, respectively. For MornigaM, the specific agglutination activity was 5.4 and 43 ng mL−1 with rabbit and human erythrocytes, respectively. MornigaG and MornigaM are one to two orders of magnitude more potent hemagglutinins than all other JRLs except jacalin and the Maclura pomifera agglutinin (MPA), which are about as active as the Morus lectins (Fig. 2). MornigaG is (like jacalin and MPA) almost equally active with rabbit and human erythrocytes, whereas MornigaM has a clear preference for rabbit red blood cells (Fig. 2). A similar (or even more pronounced) preference for rabbit over human erythrocytes was observed for all Man-binding JRLs. However, it should be emphasized that MornigaM is at least 25 times more active than any other Man-binding JRL. This is important because the unusually high specific agglutination activity may be indicative for a stronger biological activity of MornigaM compared with the previously identified homologs from other plant species.

Figure 2.

Comparison of specific agglutination activity of different Man-specific (left) and Gal-specific (right) JRLs. Results are expressed as the agglutination titer of lectin solutions of 1 mg mL−1. Agglutination activity was tested with trypsin-treated rabbit (RRBC) and human group A (HRBC) erythrocytes. All lectins were isolated by affinity chromatography on immobilized Man or Gal, and were essentially pure.

To determine the overall carbohydrate specificity of MornigaG and MornigaM, the inhibitory effect of a series of simple sugars was tested in hapten inhibition assays of the agglutination of rabbit erythrocytes. The agglutination of rabbit erythrocytes by MornigaG was readily inhibited by Gal, with the inhibitory concentration required to cause 50% inhibition (IC50) being 25 mm, but not by Glc, Man, methyl α-d-mannopyranoside, or any other simple sugar (even when used at a concentration as high as 200 mm). Similar assays revealed that MornigaM was very efficiently inhibited by methyl α-d-mannopyranoside (IC50 = 1.5 mm) and to a lesser extent by Man (IC50 = 12.5 mm) and Glc (IC50 = 25 mm), but not by Gal or any other simple sugar.

Molecular Cloning of Black Mulberry Tree Lectins

Screening of a cDNA library constructed with poly(A)-rich RNA from bark using a synthetic oligonucleotide derived from the N-terminal amino acid sequence EINFEYN of MornigaG yielded a high number of positive clones. Sequence analysis of the cDNA clone LECMornigaG1 encoding MornigaG revealed that it contains an open reading frame of 669 bp encoding a 223-amino acid precursor with a putative initiation codon at position 8 of the deduced amino acid sequence. Translation starting with this Met residue yields a 216-amino acid polypeptide (with a calculated molecular mass of 23,457 D) that shares a high sequence similarity with the precursor of jacalin (Fig. 3). In a later stage, additional cDNA clones encoding MornigaG were obtained after screening of the cDNA library using LECMornigaG as a probe. Sequence analyses revealed minor differences among the deduced amino acid sequences of the different cDNA clones.

Figure 3.

Deduced amino acid sequence of cDNA clones encoding the black mulberry tree lectins. A, Alignment of precursor sequences encoding MornigaG and jacalin. B, Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences encoding MornigaM and Heltuba, and the protein sequence of KM+ (Rosa et al., 1999). C, Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences encoding MornigaG and MornigaM. Amino acids that are conserved among the different sequences are boxed.

The deduced amino acid sequence of LECMornigaG1 comprises a perfect match with the amino acid sequence of the β-chain (I70–S81) and the N terminus of the α-chain (G83–N102; Fig. 3). Because the precursor of MornigaG shares a very high sequence identity with that of jacalin (Yang and Czapla, 1993), one can reasonably assume that both preproproteins are processed in a similar way. In accordance with this, the primary translation product of LECMornigaG1 contains the information for a signal peptide (residues 1–21), a propeptide (residues 22–60), the 22-amino acid β-chain (residues 60–81; 2,176 D), a short linker peptide SN (residues 82–83), and the 133-amino acid α-chain (residues 84–216; 14,685 D), respectively (Fig. 4). Though the precursors of MornigaG and jacalin are very similar, there is apparently a difference for what concerns the length and the site of the excision of the linker between the α- and β-chains because a dipeptide (S82N83) is excised from pro-MornigaG, whereas processing of projacalin involves the removal of a tetrapeptide (T80SSN83). As a result, the β-chain of MornigaG is two amino acid residues longer than that of jacalin. However, it should be mentioned that according to the results of mass spectrometry analyses, a small part of the β-chain of jacalin also consists of a 22-residue polypeptide (Young et al., 1995).

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the differences in biosynthesis, processing, and topogenesis of MornigaG and MornigaM. In the top panel (MornigaG), SP, NPT, and L refer to signal peptide, N-terminal propeptide, and linker between α- and β-chain, respectively. In the bottom panel (MornigaM), M and P refer to the N-terminal Met residue and the N-terminal propeptide, respectively. PTP, Primary translation product; PTP-Met-1, Primary translation product after removal of the N-terminal Met.

The sequence of the mature α-chain contains two putative glycosylation sites, 21NET and 35NGT, respectively. Carbohydrate estimations indicated that MornigaG contains approximately 6% covalently bound sugars (corresponding to six to seven monosaccharide units per α-chain). Subtracting the calculated molecular mass of the naked α-chain (14,685 D) from that of the mature α-chains (15,776; 15,786; 15,811; 15,828; 15,976; 15,992; and 16,032 D, respectively) yields a difference of 1,091; 1,101; 1,126; 1,143; 1,291; 1,307; and 1,347 D, respectively. These differences in molecular mass correspond to six to seven monosaccharide units, indicating that the α-chain contains a single N-glycan. On the analogy of jacalin and MPA (Young et al., 1995), the occurrence of multiple forms the α-chain of MornigaG can be ascribed most probably to genetic and posttranslational microheterogeneity.

Screening of the same cDNA library using a synthetic oligonucleotide derived from the N-terminal amino acid sequence WGGPGGNAWD of MornigaM resulted in the cloning of MornigaM. Sequence analysis of the cDNA clone LECMornigaM1 encoding MornigaM revealed an open reading frame of 531 bp encoding a 177-amino acid polypeptide with one putative initiation codon at position 17 of the deduced amino acid sequence. Translation starting with this Met residue yields a 161-amino acid polypeptide with a calculated molecular mass of 16,984 D (Fig. 3). Because residues T8-D31 of this deduced acid sequence match almost perfectly the N-terminal sequence, there is no doubt that LECMornigaM encodes MornigaM. Further analysis indicated that the deduced amino acid sequence of LECMornigaM contains no signal peptide (von Heijne, 1986), which suggests that MornigaM is like all other Man-binding JRLs synthesized on free polysomes. The calculated molecular mass of the primary translation product (16,984 D) differs from the values obtained by mass spectrometry of the mature protein (16,320 and 16,898 D, respectively). One of these polypeptides is 45 D larger than the primary translation product after cleavage of the Met residue (16,853 D). Most probably, this polypeptide corresponds to the primary translation product minus the N-terminal Met but with an acetylated N-terminal Ala. It should be mentioned here that the N-terminal Ala of the mature KM+ polypeptide also is acetylated (Rosa et al., 1999). The second lectin polypeptide with a molecular mass of 16,320 corresponds to a protein starting with the sequence TQSTGTSQ (16,322 D). N-terminal sequencing confirmed that a small part of MornigaM starts with this sequence, which implies that at least part of the primary translation product is posttranslationally processed by the removal of an N-terminal heptapeptide. Therefore, it can be concluded that the bulk of the primary translation product of MornigaM is modified by the removal of the N-terminal Met followed by an acetylation of the resulting N-terminal Ala. Only a small part of the protein is proteolytically modified through the cleavage of a short N-terminal peptide of seven residues (Fig. 4). Sequence comparisons revealed that the deduced amino acid sequence of LECMornigaM shares 69% sequence similarity with the protein sequence of the Man-binding lectin of KM+ from jack fruit seeds (Rosa et al., 1999). The high sequence identity and structural similarity support the idea that MornigaM has to be considered a “vegetative” homolog of the seed-specific KM+ from jack fruit. However, it should be mentioned that mature KM+ lacks the first 11 N-terminal amino acid residues of the N-acetylated MornigaM and the first five residues of the processed MornigaM. Because KM+ has not been cloned, it is not clear whether the different N terminus of the jack fruit and black mulberry homologs is due to a different length of the primary translation product or to a difference in posttranslational processing.

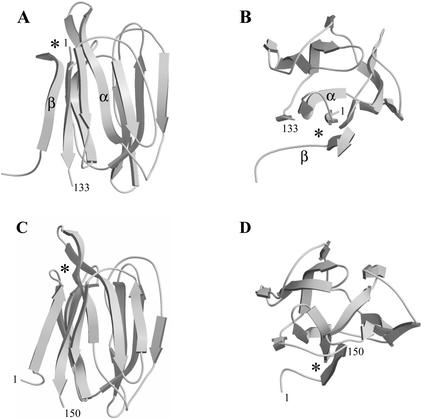

Molecular Modeling of MornigaG and MornigaM

MornigaG and MornigaM share a high sequence identity (74.5% and 60.7%, respectively) and similarity (86.3% and 74.0%, respectively) with jacalin. Hydrophobic cluster analysis (HCA) confirmed the close structural similarity between the black mulberry tree lectins and jacalin. All 12 strands of β-sheet occurring in jacalin are well conserved and are at similar positions in MornigaG and MornigaM (result not shown). For the molecular modeling of the black mulberry tree lectins, two different model lectins were used. Jacalin was used as a model for MornigaG because both lectins closely resemble each other for what concerns their specificity and molecular structure (i.e. the presence of an α- and a β-chain). For MornigaM, Heltuba was used as a model because this is the only Man-specific JRL for which the structure has been resolved.

The three-dimensional model of the MornigaG monomer built from the coordinates of jacalin comprises a heavy α-chain of 133 residues noncovalently associated with a light β-chain of only 19 residues. In contrast, the three-dimensional model of MornigaM built from the x-ray coordinates of Heltuba consists of a single polypeptide chain. Like jacalin and Heltuba, the MornigaG and MornigaM monomers exhibit a typical β-prism architecture, which consists of three bundles of four-stranded β-sheets oriented parallel to the axis of the prism (Fig. 5). The α-chain of MornigaG contains 11 strands of β-sheet forming two four-stranded bundles and an incomplete three-stranded bundle of β-sheet. An additional strand of β-sheet present in the short β-chain completes this third bundle of β-sheet to form a regular β-prism structure. The carbohydrate-binding site of MornigaG comprises residues Gly-1, Tyr-122, Trp-123, and Asp-125 of the α-chain, and is located at the top of the β-prism. All four residues involved in the binding site of MornigaG are exactly the same as in jacalin. In the structure of MornigaM, all 12 strands of β-sheet are located on a single polypeptide. However, the organization of these 12 strands into three four-stranded bundles is virtually the same as in MornigaG. The carbohydrate-binding site of MornigaM consists of the residues Gly-16, Phe-139, Val-140, and Asp-142, and is located at the top of the β-prism. All four residues involved in the binding site of MornigaM are exactly the same as in Heltuba. It is interesting to note here that two of the four residues of the binding sites of MornigaG and MornigaM are different, whereas all four residues are identical between MornigaG/jacalin and MornigaM/Heltuba.

Figure 5.

Ribbon diagrams showing the β-prism architecture of the MornigaG (A, side view; B, top view) and MornigaM (C, side view; D, top view) monomer. The location of the monosaccharide-binding site at the top of the monomer is indicated by an asterisk. In the structure of MornigaG, the noncovalently associated α-chain and β-chain are labeled by the symbols α and β, respectively. The contribution of the β-chain of the MornigaG to the formation of the third four-stranded bundle of β-sheet (lower left) is shown in the top view of the β-prism (B). Figures were rendered with MOLSCRIPT and RASTER3D.

MornigaG and MornigaM Are Developmentally Regulated

A comparison of the protein composition of bark tissue collected during summer and winter by SDS-PAGE clearly demonstrated that the intensity of the lectin polypeptide bands strongly increases during fall (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 4). Semiquantitative agglutination assays indicated that the total lectin activity is approximately 5-fold higher in “winter bark” than in “summer bark.” Furthermore, northern-blot analysis of RNA isolated from bark collected in summer (mid July) and fall (mid October) showed that the lectin mRNAs are much more abundant in fall than in summer (results not shown).

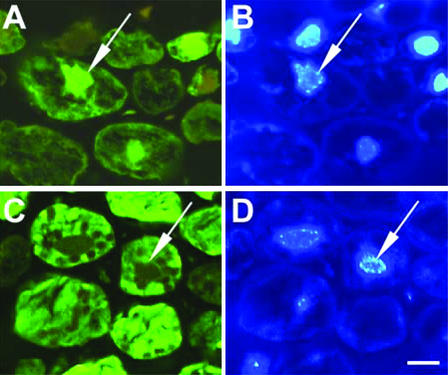

Immunocytochemical Localization of MornigaG and MornigaM in the Cells of Bark Tissue

MornigaG and MornigaM are abundantly present in the cells of black mulberry bark. Staining of the sections with anti-MornigaM antibodies yielded a strong signal underneath the cell wall and in the nucleus (which was identified by the concomitant DAPI staining; Fig. 6, A and B). This particular staining pattern confirms that MornigaM is at least partly located in the cytoplasm (as could be predicted on the basis of the deduced sequence of the primary translation product of the corresponding gene). In addition, it also appears that a considerable part of MornigaM is located in the nucleus. In accordance with this, MornigaM should be considered a cytoplasmic/nuclear protein. The labeling of MornigaG is clearly distributed over the whole area of the cell, whereas the nucleus is completely unlabeled (Fig. 6, C and D). This indicates that this lectin is, as could be expected on the basis of the presence of similar vacuolar targeting sequences in the MornigaG precursor as in jacalin, located within vacuoles.

Figure 6.

Immunocytochemical localization of MornigaM and MornigaG in bark of black mulberry tree. For immunocytochemical analysis, semi-thin sections were probed with antibodies raised against MornigaM (A) and MornigaG (C), respectively, followed by a goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibody conjugated with Alexa 488 as described in “Materials and Methods.” A and C, Treatment with MornigaM and MornigaG antibody, respectively. B and D, Concomitant 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining of the sections shown in A and C, respectively. The position of nuclei is marked by arrows. Bar = 10 μm in all micrographs.

Seed-Specific Homologs of MornigaG and MornigaM

Crude extracts from black mulberry tree seeds also agglutinated trypsin-treated erythrocytes. However, the titer of the seed extract (400) was three orders of magnitude lower than that of crude bark extracts, suggesting that the lectin content of the seed is approximately 1,000-fold lower than that of the bark. This huge difference in lectin content was confirmed by SDS-PAGE that demonstrated that no major polypeptide bands are present in the pattern of the seed extract at the position corresponding to that of the bark lectins (Fig. 1, lane 1).

Hapten inhibition assays demonstrated that the agglutination activity of the seed extract was, unlike that of the bark extract, almost completely inhibited by Gal, indicating that the black mulberry tree seeds contain exclusively or predominantly a Gal-specific lectin. Affinity chromatography of the seed extract on Gal-Sepharose 4B yielded a small quantity of a seed-specific Gal-specific black mulberry tree agglutinin (MornigaGs). Careful examination of the unretained fraction revealed that a weak agglutination activity was left over in the seed extract after removal of MornigaGs. This residual lectin activity was insensitive to Gal, but was completely inhibited by Man. Subsequent affinity chromatography on Man-Sepharose 4B yielded a very small amount of a seed-specific Man-specific black mulberry tree agglutinin (MornigaMs).

To corroborate the relationship of MornigaGs and MornigaMs to MornigaG and MornigaM, respectively, the purified seed lectins were partially characterized. MornigaGs and MornigaG behaved identically upon SDS-PAGE and gel filtration (results not shown). Both lectins showed the same specific agglutination activity and exhibited the same specificity toward simple sugars. In addition, the N-terminal sequence of the 17-kD polypeptide of MornigaGs was identical to that of the β-chain of MornigaG. Based on these results, it can be concluded that MornigaGs is a virtually identical seed-specific homolog of MornigaG. The available quantity of MornigaMs was too small to compare the seed lectin with MornigaM by SDS-PAGE and gel filtration. However, both lectins showed identical agglutination properties and exhibited the same sugar specificity, suggesting that MornigaMs is a similar (or possibly identical) seed-specific homolog of the bark-specific MornigaM.

DISCUSSION

The bark of the black mulberry tree accumulates large quantities of two related, though different, JRLs. One of these lectins (MornigaG) has the same molecular structure and carbohydrate-binding specificity as jacalin and hence can be classified in the subfamily of Gal-specific JRLs. The other lectin (MornigaM) shares its molecular structure and overall specificity with KM+ and related lectins and thus clearly belongs to the subfamily of Man-specific JRLs. Both black mulberry tree bark lectins accumulate in very high concentrations and are developmentally regulated like bark-specific VSPs. In this respect, MornigaG and MornigaM resemble the bark lectins of the legume trees, black locust (Nsimba-Lubaki and Peumans, 1986), Japanese pagoda tree (Baba et al., 1991), yellow wood (Van Damme et al., 1995a), Maackia amurensis (Van Damme et al., 1997b), and elderberry (Nsimba-Lubaki and Peumans, 1986). This implies that beside legume lectins and type-2 ribosome-inactivating proteins, members of the family of the JRLs can be considered bark-specific VSPs. Though the concept of lectins as bark storage proteins is not novel, the black mulberry tree bark is a unique system for two reasons.

First, the total lectin content (approximately 80% of the total protein content) is extremely high. Second, the bark of black mulberry tree apparently accumulates a typical vacuolar (MornigaG) and a cytoplasmic/nuclear (MornigaM) lectin. This is an important observation because to the best of our knowledge, no (putative) cytoplasmic/nuclear bark storage protein has been identified. Moreover, the fact that MornigaM accounts for 53.3% of the total bark protein demonstrates for the first time, to our knowledge, that a plant tissue accumulates the bulk of its storage proteins as a cytoplasmic/nuclear protein. It is interesting that the prominent nuclear location of MornigaM is reminiscent to that of the recently discovered jasmonate-induced chitin-binding tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) lectin, which occurs in the cytoplasm and nucleus of the leaf cells (Chen et al., 2002). However, there is an important difference because MornigaM does not, unlike in the tobacco lectin, contain a classical nuclear localization signal in its sequence. MornigaM also differs from the previously studied mannose-specific JRL from hedge bindweed, which is exclusively located in the cytoplasm of the rhizome cells and is absent from the nuclei (Peumans et al., 2000a). This observation indicates that the apparent partial nuclear location of MornigaM cannot be extrapolated to all mannose-specific JRLS.

The simultaneous occurrence of a Gal-specific JRL and a Man-specific JRL in a single tissue has already been documented for jack fruit seeds. However, in this particular case, the Gal-specific lectin is a major seed storage protein (accounting for approximately 70% of the total seed protein), whereas the Man-specific lectin is only a minor protein (Rosa et al., 1999). Estimates based on earlier reports and our own experimental data indicate that jacalin is 50 to 100 times more abundant than KM+.

Seeds of the black mulberry tree also contain a gJRL and a mJRL. This simultaneous occurrence of closely related lectins in seeds and bark is not unique for mulberry, but has also been encountered in most tree species that express bark lectins. For example, seeds of elderberry contain type-2 ribosome-inactivating proteins that closely resemble their bark-specific homologs (Peumans et al., 1991). In a similar manner, seeds of the legume trees black locust (Van Damme et al., 1995b), Japanese pagoda tree (Van Damme et al., 1997a), and Maackia amurensis (Yamamoto et al., 1994) contain lectins, which are closely related though not identical with the respective bark lectins. The observation that bark-specific lectins from three structurally and evolutionarily unrelated lectin families have seed-specific homologs in most species in which they are expressed is important in view of the evolution of plant lectins and their genes. Taking into consideration the high sequence similarity/identity between seed and bark-specific homologs, one can reasonably assume that their genes evolved from a common ancestor through the acquisition of seed- and bark-specific promoters, respectively.

The fact that plants apparently used a similar mechanism for legume lectins, type-2 ribosome-inactivating proteins, and JRLs was most probably not by chance or coincidence but was driven by an evolutionary pressure to express carbohydrate-binding domains in seeds and bark. Though circumstantial, evidence for the possible involvement of such an evolutionary pressure for the lectins follows the observation that thus far, no bark-specific counterparts have been identified of the classic seed-specific storage proteins like prolamins, 7S and 11S globulins, and 2S albumins. The key question that remains is what kind of evolutionary pressure may have driven plants to develop a genetic system that directs the expression of lectins in seeds and bark. In other words, why do plants accumulate seed and bark lectins? According to the currently accepted ideas, the most abundant lectins, irrespective whether they are located in seeds or vegetative tissues, fulfill a double role. Under normal conditions (i.e. in the absence of a challenge by a predating organisms), plant lectins just fulfill a role as storage proteins. However, as soon as the plant is attacked by a herbivorous animal or a phytophagous invertebrate, the lectins act as unspecific defense proteins (Chrispeels and Raikhel, 1991; Peumans and Van Damme, 1995). The possible toxicity of MornigaG and MornigaM toward higher animals and invertebrates has not yet been studied. However, because MornigaG and MornigaM are capable of interacting with animal glycoproteins, one can reasonably expect that they can exert harmful or deleterious effects in the gastrointestinal tract of higher animals or insects. It is worth noting in this context that jacalin, which is virtually identical to MornigaG, possesses insecticidal properties (Czapla and Lang, 1990). As has been suggested for other tree species that express two or more bark lectins (e.g. elderberry and Japanese pagoda tree) with a different carbohydrate-binding specificity, the simultaneous accumulation of a Gal- and a Man-specific JRL in the bark of black mulberry tree extends the spectrum of foreign target glycans, which eventually enables the plant to defend itself against a broader range of pests.

Although the simultaneous occurrence of a Gal-specific (jacalin) and a Man-specific JRL (KM+) in jack fruit seeds has been known for years (De Miranda Santos et al., 1991), the exact relationship between both lectins is still unknown because KM+ has not yet been cloned. Therefore, the molecular cloning of MornigaG and MornigaM allowed us, for the first time, to our knowledge, to make a detailed comparison of the (deduced) amino acid sequences of a Gal-specific and a Man-specific JRL from a single species. Beside confirming that MornigaG is virtually identical to the previously described Gal-specific lectins from jack fruit and Osage orange, our results unambiguously demonstrated that MornigaM is a structural and functional homolog of the Man-specific JRLs from hedge bindweed (Peumans et al., 1997), Jerusalem artichoke (Van Damme et al., 1999), and rice (Zhang et al., 2000).

The identification of MornigaG and MornigaM is also important because it demonstrates that the bark of the black mulberry tree is a rich source of two different lectins with interesting carbohydrate-binding properties and biological activities. Although MornigaG closely resembles jacalin with respect to its sequence and molecular structure, there are definitely subtle differences between both lectins for what concerns their respective specificity. Therefore, it can be expected that, on the analogy of jacalin, MornigaG will be a useful tool and a bioactive protein suitable for numerous applications in biological and biomedical research. MornigaM is even more promising than MornigaG. Several previously isolated Man-specific JRLs proved to be very useful lectins because of their unique specificity toward Man and oligomannosides. It is unfortunate that the potential use of most of these lectins is limited because they are present in low concentrations and are, for practical reasons, difficult to prepare in reasonable amounts. This drawback does certainly not apply to MornigaM because this lectin can easily be prepared in gram quantities. Moreover, because MornigaM is a much more potent agglutinin than any other Man-specific JRL, one can reasonably expect that this novel lectin will be superior to all previously described Man-specific JRLs for various applications as a tool and/or bioactive protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All bark material was obtained from a single black mulberry (Morus nigra) tree. Bark used for the isolation of RNA destined for the construction of the cDNA library was stripped from young shoots around mid-October, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −70°C until use. For the purification of the proteins, branches of different age were cut from the tree in January (winter bark). The bark was stripped with a knife, lyophilized, and powdered in a coffee mill. Samples of summer bark used for protein and RNA extraction were collected in July. Seeds were isolated from ripe fruits collected from the same tree.

Preparation of Crude Extract

Bark meal (50 g) was extracted in 500 mL of 0.2 m NaCl containing 0.2% (w/v) ascorbic acid (adjusted to pH 7) by continuous stirring overnight in the cold (2°C). The homogenate was passed through a sieve and was centrifuged at 3,000g for 10 min. CaCl2 (1 g L−1) was added to the supernatant and the pH was adjusted to 9.0 with 1 n NaOH. After removal of the bulky precipitate by centrifugation (3,000g for 10 min), the supernatant was adjusted to pH 7.5 with 1 n HCl, and solid ammonium sulfate was added to a final concentration of 1 m. The extract was kept overnight in the cold room at 2°C and was centrifuged (8,000g for 10 min). The resulting supernatant was filtered through filter paper (3MM; Whatman, Beverly, MA) and was used for the isolation of the Gal- and Man-specific bark lectins by successive affinity chromatography on immobilized Gal and Man.

Isolation of the Gal-Specific Black Mulberry Tree Agglutinin (MornigaG)

The cleared extract from the bark meal was loaded on a column (2.5 × 10 cm; 50-mL bed volume) of Gal-Sepharose 4B equilibrated with 1 m ammonium sulfate. After loading the extract, the column was washed with 1 m ammonium sulfate until the A280 fell below 0.01 and the bound (Gal-specific) lectin eluted with 200 mL of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 10). The pH of the lectin solution was adjusted to 7.5 with 1 n acetic acid, solid NaCl was added to a final concentration of 0.2 m, and the affinity chromatography on Gal-Sepharose 4B was repeated using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 1.5 mm KH2PO4, 10 mm Na2HPO4, 3 mm KCl, and 140 mm NaCl, pH 7.4) as a running buffer. The bound lectin was eluted with a solution of 0.1 m Gal in PBS, dialyzed against the appropriate buffer, and stored at −20°C until use. After two consecutive rounds of affinity chromatography, the MornigaG preparation was essentially devoid of the Man-binding MornigaM. The total yield of MornigaG was 630 A280 units (approximately 400 mg) 50 g−1 of bark meal.

Isolation of the Man-Specific Black Mulberry Tree Agglutinin (MornigaM)

The flow-through and the wash fractions of the first affinity chromatography on Gal-Sepharose 4B were pooled and loaded on a column (2.5 × 10 cm; 50-mL bed volume) of Man-Sepharose 4B equilibrated with 1 m ammonium sulfate. After loading, the column was washed with 1 m ammonium sulfate until the A280 fell below 0.01 and the bound lectin eluted with 200 mL of a solution of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 10). The pH of the lectin solution was adjusted to 7.5 with 1 n acetic acid and solid NaCl was added to a final concentration of 0.2 m. To remove possible traces of MornigaG, the lectin was first loaded on a column (1.6 × 5 cm; 10-mL bed volume) of Gal-Sepharose 4B equilibrated with PBS. The flow-through and the first 25 mL of wash solution (PBS) were pooled and subjected to a second affinity chromatography on the Man-Sepharose 4B using PBS as a running buffer. The bound lectin was eluted with a solution of 0.1 m Man in PBS, dialyzed against the appropriate buffer, and stored at −20°C until use. After two consecutive rounds of affinity chromatography (in combination with an intermediate affinity chromatography on immobilized Gal), the MornigaM preparation was essentially devoid of the Gal-binding MornigaG. The total yield of MornigaM was 1,240 A280 units (approximately 800 mg) 50 g−1 of bark meal.

Isolation of Black Mulberry Tree Seed Lectins

Dry black mulberry seeds (5 g) were powdered with mortar and pestle and extracted in 50 mL of 0.1 m Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.2 m NaCl. The homogenate was centrifuged at 9,000g for 15 min and the resulting supernatant was filtered through filter paper (3MM; Whatman). The cleared extract was applied on a column (1 × 5 cm; approximately 4-mL bed volume) of Gal-Sepharose 4B equilibrated with PBS. After loading the extract, the column was washed with the same buffer until the A280 fell below 0.01. The bound lectin (MornigaGs) was eluted with 5 mL of 20 mm acetic acid, lyophilized, and was redissolved in 1 mL of PBS.

The pass-through and first 10 mL of wash solution of the affinity chromatography on Gal-Sepharose 4B were combined and loaded onto a column (1 × 5 cm; approximately 4-mL bed volume) of Man-Sepharose 4B equilibrated with PBS. After loading the extract, the column was washed with PBS until the A280 fell below 0.01 and the bound lectin (called MornigaMs) eluted with a solution of 20 mm acetic acid, lyophilized, and was redissolved in 1 mL of PBS.

The total yield of MornigaGs and MornigaMs was 1.5 A280 units (approximately 1 mg) and 0.05 A280 units (approximately 30 μg), respectively, 5 g−1 of seed meal.

Hemagglutination Tests and Hapten Inhibition Assays

Agglutination assays were carried out in small glass tubes or in 96 U-welled microtiter plates in a final volume of 50 μL containing 40 μL of a 1% (v/v) suspension of red blood cells and 10 μL of extracts or lectin solutions. To determine the specific agglutination activity, the lectin was serially diluted with 2-fold increments. Agglutination was assessed visually after 1 h at room temperature. Rabbit and human (blood group A) erythrocytes were treated with trypsin as described previously (Van Damme et al., 1996).

The carbohydrate-binding specificity of the lectin was determined by hapten inhibition of the agglutination of trypsinized rabbit erythrocytes. To 10 μL of crude extract or a solution of purified lectin (in PBS), 10-μL aliquots of solutions of sugars (0.5 m in PBS) or glycoproteins (5 mg mL−1 in PBS) were added. After preincubation for 1 h at 25°C, 30 μL of a 1% (v/v) suspension of trypsinized rabbit erythrocytes was added and the agglutination was evaluated after 1 h. To determine the inhibitory potency of the most active monosaccharides and glycoproteins, the assays were repeated with serially diluted stock solutions of sugars and glycoproteins. The concentration required for 50% inhibition of the agglutination of trypsin-treated rabbit erythrocytes was determined visually.

Analytical Methods

Extracts and purified black mulberry tree lectins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 12.5% to 25% (w/v) acrylamide gradient gels as described by Laemmli (1970). For N-terminal amino acid sequencing, purified proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and were electroblotted on a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Polypeptides were excised from the blots and were sequenced on a protein sequencer (model 477A/120A or Procise 491 cLC; Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA). Prior to mass spectrometry, proteins were desalted on a C4-ZipTip (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Proteins were dissolved in 50% (v/v) water and 50% (v/v) acetonitrile containing 0.1% (v/v) acetic acid and they were injected at 5 μL min−1 on an electrospray ion trap mass spectrometer (Esquire-LC-MS; Bruker Daltonic, Bremen, Germany). About 300 spectra were averaged, resulting in an accuracy of ±0.01% for proteins with a relative molecular mass of 10,000.

Total neutral sugar was determined by the phenol/H2SO4 method (Dubois et al., 1956), with d-Glc as a standard. Analytical gel filtration was performed on a Pharmacia Superose 12 column (Amersham Biosciences AB, Uppsala) using PBS containing 0.1 m Gal and 0.1 m Man (to avoid possible binding of the lectins to the column) as a running buffer at a flow rate of 20 mL h−1. Due to the aberrant elution behavior of lectins, the molecular mass of native MornigaG and MornigaM was estimated using well-characterized members of the same lectin family, namely jacalin (60 kD) and Calsepa (32 kD) as markers.

Preparation of Monospecific Antibodies and Western Blot

Polyclonal antibodies were raised against MornigaG and MornigaM in male New Zealand white rabbits. The animals were injected with 1 mg of purified protein dissolved in PBS and were emulsified in 1 mL of Freund's complete adjuvant. Five booster injections with 1 mg of purified protein in 1 mL of PBS were given at 10-d intervals. Ten days after the final injection, blood was collected from an ear marginal vein. After clotting, the crude serum was prepared by centrifugation (3,000g for 5 min). Both antisera were purified by affinity chromatography on the respective immobilized antigens as previously described (Desmyter et al., 2001). Preliminary Western-blot experiments showed that affinity-purified anti-MornigaG antibodies strongly crossreacted with MornigaM and that affinity-purified anti-MornigaM antibodies strongly crossreacted with MornigaG. Due to this strong crossreactivity, the affinity-purified antibody preparations were unsuitable for immunolocalization studies of the black mulberry bark lectins. To remove the crossreacting antibodies, the affinity-purified anti-MornigaG antibody fraction was depleted of MornigaM-binding antibodies by affinity chromatography on immobilized Morniga M. In a similar manner, the affinity-purified anti-MornigaM antibody fraction was depleted of MornigaG-binding antibodies by affinity chromatography on immobilized MornigaG. Western-blot analysis revealed that the final anti-MornigaG antibody fraction reacted exclusively with MornigaG, whereas the final anti-MornigaM antibody fraction reacted exclusively with MornigaM. Coupling of the antigens to the column and purification of the antiserum were performed as described previously for jacalin and Calsepa (Peumans et al., 2000a).

Immunocytochemistry

Small pieces of young black mulberry bark were fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde and 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 in PBS, embedded in polyethylene glycol, and cut as described (Hause et al., 1996). Cross sections (2 μm thick) were immunolabeled by incubation with purified primary antibodies raised against MornigaM and MornigaG, respectively, (diluted 1:250 [MornigaM] or 1:2,000 [MornigaG] in PBS containing 2% [w/v] acetylated bovine serum albumin and 1 mg mL−1 goat IgG) followed by an goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with Alexa488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After immunolabeling, sections were stained with 0.1 μg mL−1 DAPI for 15 min and were mounted in citifluor/glycerol. Control experiments were performed by omitting the primary antibody and they revealed no signal. The fluorescence of immunolabeled MornigaM and MornigaG as well as of DAPI-stained nuclei was visualized with a epifluorescence microscope ('84Axioskop; Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using the proper filter combinations. Micrographs were taken by a CCD camera (Sony, Tokyo) and were processed through the Photoshop program (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

RNA Isolation, Construction, and Screening of cDNA Library

Total cellular RNA was prepared from bark collected in autumn and poly(A)-rich RNA enriched by chromatography on oligo-deoxythymidine cellulose. A cDNA library was constructed with poly(A)-rich RNA using the Cap Finder cDNA Synthesis kit from Clontech Laboratories (Palo Alto, CA). cDNA fragments were inserted into the EcoRI site of pUC18 (Pharmacia, Uppsala). The library was propagated in Escherichia coli XL1 Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Recombinant lectin clones were screened using a 32P end-labeled degenerate oligonucleotide probes derived from the N-terminal amino acid sequence of MornigaG (20-mer, 5′-TTRTAYTCRAARTTDATYTC-3′) and MornigaM (29-mer, 5′-TGGGGNGGNCCNGGNGGNAAYGCNTGGGA-3′), respectively. In a later stage, cDNA clones encoding black mulberry tree lectins were used as probes to screen for more cDNA clones. Hybridizations were done overnight as reported previously (Van Damme et al., 1996). Colonies that produced positive signals were selected and rescreened at low density using the same conditions. Plasmids were isolated from purified single colonies on a miniprep scale using the alkaline lysis method as described by Mierendorf and Pfeffer (1987) and they were sequenced by the dideoxy method (Sanger et al., 1977). DNA sequences were analyzed using programs from PC GENE (Biomed, Geneva) and GENEPRO (Riverside Scientific, Seattle).

Northern Blot

RNA electrophoresis was performed according to Maniatis et al. (1982). Poly(A)-rich RNA (approximately 3 μg) was denatured in glyoxal and dimethyl sulfoxide and was separated in a 1.2% (w/v) agarose gel. After electrophoresis, the RNA was transferred to Immobilon N membranes (Millipore) and the blot was hybridized using a random primer-labeled cDNA insert. Hybridization was performed as reported by Van Damme et al. (1996). An RNA ladder (0.16–1.77 kb) was used as a marker.

Molecular Modeling

The program SEQVU (The Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney) was used to compare the amino acid sequences of MornigaG and MornigaM to that of other JRLs.

HCA (Gaboriaud et al., 1987; Lemesle-Varloot et al., 1990) was performed to delineate the structurally conserved regions between the amino acid sequences of MornigaG and jacalin (Sankaranarayanan et al., 1996) on the one hand, and the sequences of MornigaM and Heltuba (Van Damme et al., 1999) on the other. HCA plots were generated using the program HCA-Plot2 (Doriane, Paris).

Molecular modeling of MornigaG and MornigaM was performed on a Silicon Graphics O2 10000 workstation using the programs INSIGHTII, HOMOLOGY, and DISCOVER3 (MSI, San Diego). The atomic coordinates of jacalin (RCSB PDB code 1JAC; Sankaranarayanan et al., 1996) and Heltuba (RCSB PDB code 1C3M; Bourne et al., 1999) were taken from the RCSB Protein Data Bank and were used to build the three-dimensional models of MornigaG and MornigaM, respectively. Steric conflicts resulting from the replacement or the deletion of some residues in the modeled proteins were corrected during the model building procedure using the rotamer library (Ponder and Richards, 1987) and the search algorithm implemented in the HOMOLOGY program (Mas et al., 1992) to maintain proper side chain orientation. Energy minimization and relaxation of the loop regions were carried out by several cycles of steepest descent and conjugate gradient using DISCOVER3. The program TURBOFRODO (Bio-Graphics, Marseille, France) was run on the O2 10000 workstation to draw the Ramachandran plots and perform the superimposition of the models. MOLSCRIPT (Kraulis, 1991), and RASTER3D (Merritt and Bacon, 1997) were used to draw the figures.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Catholic University of Leuven (grant no. OT/98/17), by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (to A.B. and P.R.), and by the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (Belgium, grant no. G.0113.01). P.P. is a PostDoctoral Fellow of this fund.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.005892.

LITERATURE CITED

- Baba K, Ogawa M, Nagano A, Kuroda H, Sumiya K. Developmental changes in the bark lectin of Sophora japonica L. Planta. 1991;183:462–470. doi: 10.1007/BF00197746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausch JN, Poretz RD. Purification and properties of the hemagglutinin from Maclura pomifera seeds. Biochemistry. 1977;16:5790–5794. doi: 10.1021/bi00645a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne Y, Zamboni V, Barre A, Peumans WJ, Van Damme EJM, Rougé P. Crystal structure of Helianthus tuberosus lectin, a widespread scaffold for mannose-binding lectins. Struct Fold Des. 1999;7:1473–1482. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)88338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Peumans WJ, Hause B, Bras J, Kumar M, Proost P, Barre A, Rougé P, Van Damme EJM. Jasmonic acid methyl ester induces the synthesis of a cytoplasmic/nuclear chito-oligosaccharide binding lectin in tobacco leaves. FASEB J. 2002;16:905–907. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0598fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrispeels MJ, Raikhel NV. Lectins, lectin genes, and their role in plant defense. Plant Cell. 1991;3:1–9. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman GD, Chen TH, Ernst SG, Fuchigami L. Photoperiod control of poplar bark storage protein accumulation. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:686–692. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czapla TH, Lang BA. Effect of plant lectins on the larval development of European corn borer (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) and southern corn rootworm (Coleoptera:Chrysomelidae) J Econ Entomol. 1990;83:2480–2485. [Google Scholar]

- De Miranda Santos IKF, Mengel JO, Jr, Bunn-Moreno MM, Campos-Neto A. Activation of T and B cells by a crude extract of Artocarpus integrifolia is mediated by a lectin distinct from jacalin. J Immunol Methods. 1991;14:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90371-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmyter S, Vandenbussche F, Van Damme EJM, Peumans WJ. Preparation of monospecific polyclonal antibodies against Sambucus nigra lectin related protein, a glycosylated plant protein. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2001;31:209–216. doi: 10.1081/PB-100104904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugar and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- Gaboriaud C, Bissery V, Benchetrit T, Mornon JP. Hydrophobic cluster analysis: an efficient new way to compare and analyze amino acid sequences. FEBS Lett. 1987;224:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80439-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geshi N, Brandt A. Two jasmonate-inducible myrosinase-binding proteins from Brassica napus L. seedlings with homology to jacalin. Planta. 1998;204:295–304. doi: 10.1007/s004250050259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankins CN, Kindinger JI, Shannon LM. The lectins of Sophora japonica: purification, properties, and N-terminal amino acid sequences of five lectins from bark. Plant Physiol. 1988;86:67–70. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hause B, Demus U, Teichmann C, Parthier B, Wasternack C. Developmental and tissue-specific expression of JIP-23, a jasmonate-inducible protein of barley. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996;37:641–649. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a028993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraulis PJ. Molscript: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemesle-Varloot L, Henrissat B, Gaboriaud C, Bissery V, Morgat A, Mornon JP. Hydrophobic cluster analysis: procedure to derive structural and functional information from 2-D representation of protein sequences. Biochimie. 1990;72:555–574. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(90)90120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeshima M, Sasaki T, Asahi Y. Characterization of the major proteins in sweet potato tuber roots. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:1899–1902. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mann K, Farias CMSA, Gallego Del Sol F, Santos CF, Grangeiro TB, Nagano CS, Cavada BS, Calvete JJ. The amino-acid sequence of the glucose/mannose-specific lectin isolated from Parkia platycephala seeds reveals three tandemly arranged jacalin-related domains. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:4414–4422. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mas MT, Smith KC, Yarmush DL, Aisaka K, Fine RM. Modeling the anti-CEA antibody combining site by homology and conformational search. Proteins Struct Func Genet. 1992;14:483–498. doi: 10.1002/prot.340140409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt EA, Bacon DJ. Raster3D photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierendorf RC, Pfeffer D. Direct sequencing of denatured plasmid DNA. Methods Enzymol. 1987;152:556–562. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignery GA, Pikaard CS, Hannapel DJ, Park WD. Isolation and sequence analysis of cDNAs for the major potato tuber protein, patatin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:7987–8000. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.21.7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misquith S, Rani PG, Surolia A. Carbohydrate binding specificity of the B-cell maturation mitogen from Artocarpus integrifolia seeds. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30393–30401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira RA, Ainouz IL. Lectins from seeds of jack fruit (Artocarpus integrifolia L.): isolation and purification of two isolectins from the albumin fraction. Biol Plant (Praha) 1981;23:186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K, Nakamura S, Fujitake M, Nakanishi T. Complete amino acid sequence of Japanese chestnut agglutinin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:23–28. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsimba-Lubaki M, Allen AK, Peumans WJ. Isolation and characterization of glycoprotein lectins from the bark of three species of elder, Sambucus ebulus, Sambucus nigra and Sambucus racemosa. Planta. 1986;168:113–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00407017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nsimba-Lubaki M, Peumans WJ. Seasonal fluctuations of lectin in bark of elderberry (Sambucus nigra) and black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) Plant Physiol. 1986;80:747–751. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.3.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peumans WJ, Hause B, Van Damme EJM. The galactose-binding and mannose-binding jacalin-related lectins are located in different sub-cellular compartments. FEBS Lett. 2000a;477:186–192. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01801-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peumans WJ, Van Damme EJM. Lectins as plant defense proteins. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:347–352. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peumans WJ, Winter HC, Bemer V, Van Leuven F, Goldstein IJ, Truffa-Bachi P, Van Damme EJM. Isolation of a novel plant lectin with an unusual specificity from Calystegia sepium. Glycoconjugate J. 1997;14:259–265. doi: 10.1023/a:1018502107707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peumans WJ, Zhang W, Barre A, Houles-Astoul C, Balint-Kurti P, Rovira P, Rougé P, May GD, Van Leuven F, Truffa-Bachi P et al. Fruit-specific lectins from banana and plantain. Planta. 2000b;211:546–554. doi: 10.1007/s004250000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peumans WP, Kellens TC, Allen AK, Van Damme EJM. Isolation and characterization of a seed lectin from elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) and its relationship to the bark lectins. Carbohydrate Res. 1991;213:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)90593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder JW, Richards FM. Tertiary templates for proteins: use of packing criteria in the enumeration of allowed sequences for different structural classes. J Mol Biol. 1987;193:775–791. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa JC, De Oliveira PSL, Garratt R, Beltramini L, Resing K, Roque-Barreira M-C, Greene LJ. KM+, a mannose-binding lectin from Artocarpus integrifolia: amino acid sequence, predicted tertiary structure, carbohydrate recognition, and analysis of the β-prism fold. Protein Sci. 1999;8:13–24. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan R, Sekar K, Banerjee R, Sharma V, Surolia A, Vijayan M. A novel mode of carbohydrate recognition in jacalin, a Moraceae plant lectin with a β-prism fold. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:596–603. doi: 10.1038/nsb0796-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE. Developmental regulation and the influence of plant sinks on vegetative storage protein gene expression in soybean leaves. Plant Physiol. 1989a;89:309–315. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.1.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE. Preferential loss of an abundant storage protein from soybean pods during seed development. Plant Physiol. 1989b;90:1252–1255. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.4.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE. Storage proteins of vegetative plant tissues. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Mol Biol. 1994;45:303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJM, Barre A, Bemer V, Rougé P, Van Leuven F, Peumans WJ. A lectin and a lectin-related protein are the two most prominent proteins in the bark of yellow wood (Cladrastis lutea) Plant Mol Biol. 1995a;29:579–598. doi: 10.1007/BF00020986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJM, Barre A, Mazard AM, Verhaert P, Horman A, Debray H, Rougé P, Peumans WJ. Characterization and molecular cloning of the lectin from Helianthus tuberosus. Eur J Biochem. 1999;259:135–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJM, Barre A, Rougé P, Peumans WJ. Molecular cloning of the bark and seed lectins from the Japanese pagoda tree (Sophora japonica) Plant Mol Biol. 1997a;33:523–536. doi: 10.1023/a:1005781103418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJM, Barre A, Rougé P, Van Leuven F, Peumans WJ. The seed lectins of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) are encoded by two genes which differ from the bark lectin genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1995b;29:1197–1210. doi: 10.1007/BF00020462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJM, Barre A, Smeets K, Torrekens S, Van Leuven F, Rougé P, Peumans WJ. The bark lectin of Robinia pseudoacacia contains a complex mixture of isolectins: characterization of the proteins and the cDNA clones. Plant Physiol. 1995c;107:833–843. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJM, Barre A, Verhaert P, Rougé P, Peumans WJ. Molecular cloning of the mitogenic mannose/maltose-specific rhizome lectin from Calystegia sepium. FEBS Lett. 1996;397:352–356. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJM, Peumans WJ, Barre A, Rougé P. Plant lectins: a composite of several distinct families of structurally and evolutionary related proteins with diverse biological roles. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1998;17:575–692. [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme EJM, Van Leuven F, Peumans WJ. Isolation, characterization and molecular cloning of the bark lectins from Maackia amurensis. Glycoconjugate J. 1997b;14:449–456. doi: 10.1023/a:1018595300863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. A method for predicting signal cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;11:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Ishida C, Saito M, Konami Y, Osawa T, Irimura T. Cloning and sequence analysis of the Maackia amurensis haemagglutinin cDNA. Glycoconjugate J. 1994;11:572–575. doi: 10.1007/BF00731308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Czapla TH. Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones encoding jacalin isolectins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5905–5910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh KW, Chen JC, Lin MI, Chen YM, Lin CY. Functional activity of sporamin from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas Lam.): a tuber storage protein with trypsin inhibitory activity. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;33:565–570. doi: 10.1023/a:1005764702510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young NM, Watson DC, Thibault P. Mass spectrometric analysis of genetic and post-translational heterogeneity in the lectins jacalin and Maclura pomifera agglutinin. Glycoconjugate J. 1995;12:135–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00731357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Peumans WJ, Barre A, Houles-Astoul C, Rovira P, Rougé P, Proost P, Truffa-Bachi P, Jalali HA, Van Damme EJM. Isolation and characterization of a jacalin-related mannose-binding lectin from salt-stressed rice (Oryza sativa) plants. Planta. 2000;210:970–978. doi: 10.1007/s004250050705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]