Abstract

The submersed monocot Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) Royle is a facultative C4 plant. It typically exhibits C3 photosynthetic characteristics, but exposure to low [CO2] induces a C4 system in which the C4 and Calvin cycles co-exist in the same cell and the initial fixation in the light is catalyzed by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC). Three full-length cDNAs encoding PEPC were isolated from H. verticillata, two from leaves and one from root. The sequences were 95% to 99% identical and shared a 75% to 85% similarity with other plant PEPCs. Transcript studies revealed that one isoform, Hvpepc4, was exclusively expressed in leaves during C4 induction. This and enzyme kinetic data were consistent with it being the C4 photosynthesis isoform. However, the C4 signature serine of terrestrial plant C4 isoforms was absent in this and the other H. verticillata sequences. Instead, alanine, typical of C3 sequences, was present. Western analyses of C3 and C4 leaf extracts after anion-exchange chromatography showed similar dominant PEPC-specific bands at 110 kD. In phylogenetic analyses, the sequences grouped with C3, non-graminaceous C4, and Crassulacean acid metabolism PEPCs but not with the graminaceous C4, and formed a clade with a gymnosperm, which is consistent with H. verticillata PEPC predating that of other C4 angiosperms.

Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase (PEPC; EC 4.1.1.31) occurs in eubacteria, cyanobacteria, green algae, and all higher plants. In the latter, it is encoded by a small multigene family (Lepiniec et al., 1993, 1994; Ernst and Westhoff, 1997). A major function of the enzyme in higher plants is anapleurotic, providing carbon skeletons for the synthesis of compounds that serve in processes such as C/N partitioning, guard cell movements, and nitrogen fixation in legumes (Chollet et al., 1996). In C4 and Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) photosynthesis, alternate forms of PEPC catalyze the initial carboxylation step in a C4 acid cycle that functions as a CO2 concentrating mechanism. In terrestrial C4 plants, PEPC and Rubisco fixation events are separated between mesophyll and bundle sheath cells, and PEPC expression is in the cytosol of the former (Matsuoka and Sanada, 1991). In CAM plants, the fixation events are separated temporally with the CAM photosynthetic PEPC expressed in the cytosol of chloroplastic cells (Cushman and Bohnert, 1999).

Investigations on the origins of the C4 syndrome indicate that it arose independently in a number of angiosperm taxa and included changes in the genes controlling anatomical and chloroplastic development and in those orchestrating photosynthetic biochemistry (Hermans and Westhoff, 1992; Kellogg, 1999). PEPC has played an important role in these studies, and the structure, function, and phylogenetic relationships of its sequences have been used to better understand the evolution of C4 and CAM photosynthetic systems (Lepiniec et al., 1994).

The aquatic monocot Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) Royle is the best documented case of an inducible C4 photosynthetic system that concentrates CO2 in the chloroplasts without enzymatic compartmentation in mesophyll and bundle sheath cells, i.e. it lacks Kranz anatomy. When [CO2] is abundant, H. verticillata exhibits C3 characteristics, but a C4 photosynthetic system is induced by exposure to low [CO2], both in nature and in the laboratory. Thus, it is best described as a facultative NADP-ME C4 species (Bowes et al., 2002). The induction has been demonstrated by gas exchange and biochemistry, 14C pulse-chase studies, enzyme localization, and measurements of internal [CO2] (Bowes and Salvucci, 1989; Magnin et al., 1997; Reiskind et al., 1997). A unique trait of this system is that the C4 and Calvin cycles exist together within the same cell, and the site of CO2 concentrating is the leaf mesophyll chloroplasts (Reiskind et al., 1997). Global climate change scenarios predicting drought and high temperatures have heightened interest in the regulation and expression of the suite of enzymes involved in C4 photosynthesis. A goal of such research is to introduce C4 cycle components into C3 crop species with the hope that the transformants, similar to C4 and CAM plants, would have improved performance under adverse conditions (Matsuoka and Sanada, 1991; Ku et al., 1999; Mann, 1999). In this context, H. verticillata provides a higher plant example, albeit an aquatic one, of how the C4 and Calvin cycle components might co-exist in the same cell and still function in series to concentrate CO2.

As part of a molecular approach to understand how the C4 system in H. verticillata is induced and regulated, we have focused attention on the PEPC isoforms that we have found in this plant. We present evidence that one is induced and operates in C4 leaf photosynthesis. Multiple isoforms are commonly reported for PEPC gene families (Ernst and Westhoff, 1997). However, this is the first report of three full-length PEPC cDNAs isolated from a plant that is normally C3, but has evolved an inducible C4 system to combat the adverse environmental conditions of low [CO2] and high [O2], temperature, and irradiance that occur during summer days (Bowes and Salvucci, 1989). The phylogenetic relationships of H. verticillata PEPC isoforms with those of members of other species possessing C3, C4, and CAM isoform types are also shown.

RESULTS

Isolation, Cloning, and Sequencing of Three Full-Length cDNAs Encoding H. verticillata PEPC

Hvpepc3 and 4 were culled from 40 C4 leaf-derived RACE clones that screened positively for either the 3F or 4F oligoprobe. Subsequent isolations using C3 leaf material yielded only clones of Hvpepc3. A similar number of root-derived RACE clones tested positively only to the probe 3F, and from these clones, Hvpepc5 was isolated and sequenced. The salient features of these cDNAs and their encoded PEPCs are summarized in Table I. The 5′ region in all of the isoforms had two ATG triplets that are candidates for translation initiation; the two different coding sequence lengths that would occur with each of the ATG triplets are also shown. These data indicate that the encoded proteins were very similar in terms of Mr and pI.

Table I.

Characteristics of the cDNAs and the predicted amino acid sequences of the three PEPC isoforms from H. verticillata

| Hvpepc3 | Hvpepc4 | Hvpepc5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| cDNA (bp) | 3,368 | 3,197 | 3,251 |

| Coding sequence | 60–2,972 | 62–2,968 | 59–2,971 |

| 99–2,972 | 95–2,968 | 98–2,971 | |

| 5′-UTR (bp) | 1–59 (59) | 1–61 (61) | 1–58 (58) |

| Percent nucleotide identity at 5′-UTR (bp) | 100 | 80 | 98 |

| 3′-UTR (bp) | 2,973–3,368 | 2,969–3,197 | 2,972–3,251 |

| (395) | (228) | (279) | |

| Percent nucleotide identity at 3′-UTR (bp) | 100 | 67 | 99 |

| Deduced amino acids | 970 | 968 | 970 |

| Percent amino acid identity | 100 | 95 | 99 |

| Molecular mass | 110,345 | 109,970 | 110,344 |

| pI | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.4 |

Three full-length cDNAs encoding PEPC were sequenced using RACE-PCR techniques. The percent identities among the nucleotide and amino acid sequences were measured by pair-wise comparison. The data for Hvpepc4 and 5 are compared with those of Hvpepc3.

A comparison of the nucleotides (nt) from the 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions (UTR) of the three H. verticillata PEPC cDNA sequences indicates that Hvpepc3 and Hvpepc5 were very similar but not identical and that they differed from Hvpepc4. The 5′-UTR of Hvpepc5 showed 1 bp deletion and one substitution compared with Hvpepc3, whereas there were 2 bp substitutions in the 3′-UTR and 4 bp substitutions in the coding region. The Hvpepc5 sequence downstream of the stop codon (TAA) was 116 bp shorter than that of Hvpepc3. All three sequences contained a single polyadenylation signal motif.

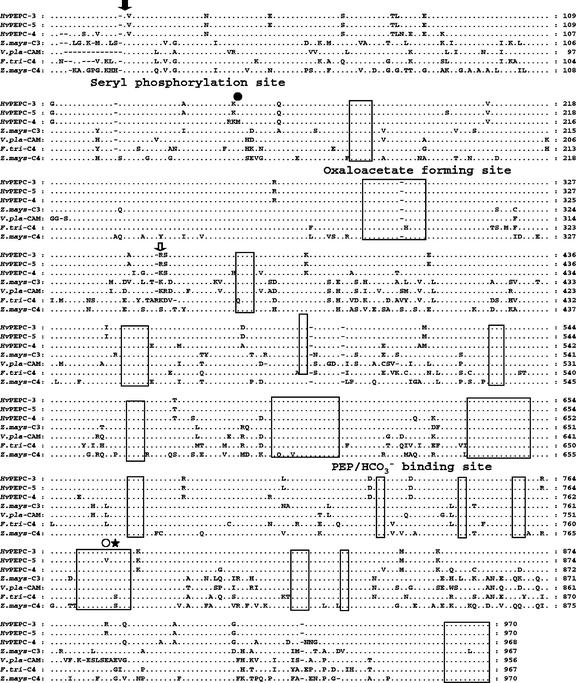

A comparative multiple alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of the three H. verticillata PEPCs with those of two other monocots and one eudicot representing C3, C4, and CAM isoform sequences is shown in Figure 1. The monocot maize contains both C3 and C4 PEPCs, whereas the monocot Vanilla planifolia has a CAM isoform. The C4 PEPC from the C4 eudicot F. trinervia was also included in the comparison because this sequence bears a phylogenetic resemblance to those of H. verticillata. The conserved regions for both eukaryotic and prokaryotic PEPCs are indicated, as well as the specific catalytic and regulatory binding locales and two putative C4 signature sites. Homology among the H. verticillata sequences was high (95%–99%), and they showed the closest resemblance to the C3 PEPC from maize (85%). Identity with the CAM PEPC was 83%, with the F. trinervia C4 PEPC 81%, and with the maize C4 PEPC 78%. In a comparison with Hvpepc3, Hvpepc5 had three substitutions resulting from the 4 bp changes, whereas Hvpepc4 had 44 substitutions and two deletions. The three substitutions found in Hvpepc5 were Ser-196 for Cys, Val-777 for Ile, and Arg-891 for Glu. The substitutions in Hvpepc4 occurred mostly in the variable regions; the Met-150 appears to be a unique change, replacing Leu, which is found in all other PEPCs listed in the database. The signature C4 Ser, Ser-774 of F. trinervia (Bläsing et al., 2000), was also present in the C4 PEPC of maize, but it was notably absent from all of the H. verticillata sequences. Instead, Ala was found at the corresponding position. A putative C4-determinant Lys-347, as described for the F. trinervia C4 PEPC, occurred in Hvpepc4 at the same position, whereas the putative C3-marker Arg occurred in the other H. verticillata isoforms (Hermans and Westhoff, 1992; Bläsing et al., 2000). It should be noted that Lys-347 is not an absolute C4 marker, because it also occurs in CAM and some C3 sequences and not in the graminaceous C4 PEPC isoforms. None of the other reported C4-determinant residues described by Hermans and Westhoff (1992) were found in the H. verticillata deduced sequences.

Figure 1.

Multiple alignment of the deduced amino acid sequences of three H. verticillata PEPCs and those of maize (Zea mays; C3 and C4), Vanilla planifolia (CAM), and Flaveria trinervia (C4). Only residues that differ among the sequences are shown. Gaps (-) and identical (.) bp are indicated. Boxed residues indicate the most conserved regions among prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Putative regulatory and catalytic sites are also shown. , The Ser residue that is common to all plant PEPCs and that is the target for phosphorylation; ●, the unique Hvpepc4 Met residue; , the F. trinervia putative C4 Lys site; ○, the unique Hvpepc5 Val; and ★, the position of the C4 signature Ser.

Differential Expression of H. verticillata Isoforms

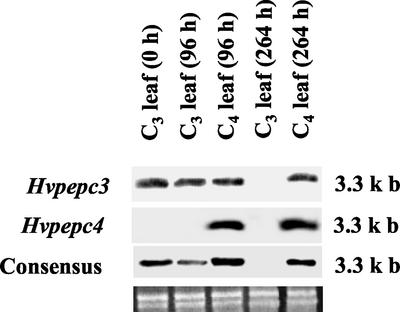

To compare the specific expression of Hvpepc3 and Hvpepc4, northern analyses were performed using C3 and C4 leaves of H. verticillata (Fig. 2). The samples were analyzed several times throughout the C4 induction period, starting at zero time when all the leaves had C3 photosynthetic characteristics. When isoform-specific RNA probes were used, Hvpepc4 was expressed exclusively in C4-induced leaves, after 96 and 264 h into the induction period. This isoform notably was not expressed in any other samples. In contrast, Hvpepc3 was expressed in C3 and C4 leaf samples, except at the 264-h C3 sampling time. The results of consensus probing were similar to those using the Hvpepc3 probe. The results represent a 1-μg total RNA loading scheme, which is the maximum recommended (Roche Diagnostics/Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis). The loading of greater quantities of total RNA (2 and 5 μg) did not change the detection threshold. The probe to the Hvpepc3 isoform was specifically synthesized from its 3′-UTR, however the similarity between these regions of Hvpepc3 and Hvpepc5 suggests that the probe could not discriminate between these two isoforms. Therefore, an Hvpepc5 signal in the C3 leaves cannot be excluded.

Figure 2.

Northern analyses of PEPC isoform expression in H. verticillata leaves in the C3 state and during induction of the C4 state. One microgram per lane of total RNA from H. verticillata C3 and C4 leaves was separated on a 1.2% (w/v) denaturing agarose gel and blotted onto a positively charged nylon membrane. DIG-labeled 3′-end RNA probes from Hvpepc3 and Hvpepc4, and a consensus probe were used to hybridize the membranes for transcript identification. The ethidium bromide-stained gel shows uniform loading of RNA samples. The size (kb) of the full-length cDNAs encoding PEPC isoforms is indicated on the right.

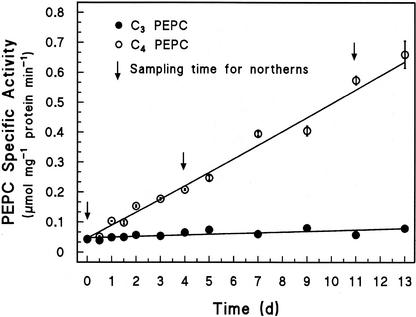

The activity of PEPC was followed in the same samples used for the northern analyses. Figure 3 shows the specific activity over time of PEPC in desalted extracts from the C3- and C4-induced leaves and shows the times when RNA was sampled for the northern analyses. The PEPC activity in the C3 leaves remained essentially constant and low. In contrast, that of the C4-induced leaves increased in a linear fashion, reaching values more than 10-fold greater than in the C3 leaves.

Figure 3.

Specific activities of PEPC in desalted extracts of H. verticillata leaves in the C3 state and during induction of the C4 state. The PEPC was extracted from leaves harvested during the light period, and activity was measured with saturating substrates at pH 8. The arrows indicate sampling times for the northern analyses. Data are means ± se, n = 3.

Partial Purification of PEPC, Kinetic Characterization, and Western Analyses

Data for the purification of PEPC from extracts of C3 and C4 leaves (harvested in the light at 288 h into the induction period) and roots, using ammonium sulfate fractionation and Q-Sepharose FF anion-exchange chromatography, are summarized in Table II. The PEPC activities were assayed at the optimal pH of 8.0 with saturating substrate concentrations. The root extract did not bind to the column but eluted as a single peak in the buffer wash. However, the leaf extracts did bind and were eluted with a linear salt gradient. The elution profiles of each of these extracts were characterized by a single peak, but with elution at slightly different salt concentrations. The specific PEPC activities in both the crude and chromatographed C4 leaf extracts were substantially higher than the corresponding C3 values, and leaf values were much higher than those of the roots. The crude activities were similar to those described previously (Fig. 3). The purification factors were greater for the leaf extracts than for the root.

Table II.

Partial purification of PEPC extracted from H. verticillata C3 and C4 leaves and roots

| Source | Specific Activity

|

Peak Elution Concentration | Purification Factor | Recovery | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | (NH4)2SO4 Pellet | Peak Fraction | ||||

| μmol mg−1 protein min−1 | mm | % | ||||

| C3 leaves | 0.078 | 0.182 | 0.590 | 200 | 7.6 | 62 |

| C4 leaves | 0.589 | 0.743 | 2.830 | 262 | 4.8 | 44 |

| Root | 0.030 | N.D. | 0.080 | 0 | 2.7 | 66 |

Leaves of H. verticillata were harvested midway through their light cycle, C3 at 0 h and C4 at 288 h into the induction period. The PEPC of C3 and C4 leaves eluted as single peaks but at different [KCl]. Ammonium sulfate precipitation was not employed for root extracts because of the initial low activity. The protein from the root extract eluted in the buffer wash, and did not bind to the Sepharose column. Specific activity was assayed with saturating substrate concentrations at pH 8. N.D., Not detemined.

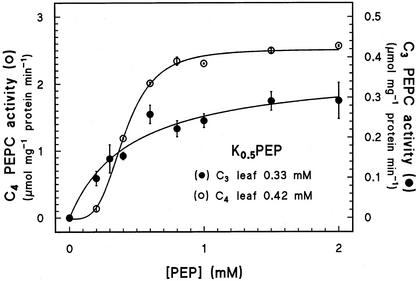

Kinetic data for the C3 and C4 leaf peak PEPC fractions are presented in Figure 4. The activities were assayed at a cytosolic-like pH of 7.3, where PEPC kinetic effects are more pronounced. A plot of activity versus [PEP] produced a hyperbolic curve for the C3 leaf enzyme that followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics (r2 = 0.957), whereas that of the C4 was sigmoid and fitted the Hill equation (r2 = 0.998). The Hill coefficients for the two extracts differed considerably, 1.8 and 3.8 for the C3 and C4 leaves, respectively. The specific activities, calculated from the Michaelis-Menten and Hill equations, were severalfold different, with the C4 value the higher (2.51 versus 0.37 μmol mg−1 protein min−1). In contrast, the K0.5 PEP values did not differ substantially, whether estimated from the graph or calculated by the Hill equation, and in addition, they were relatively high (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of PEP concentration on the specific activity of PEPC in the C3 and C4 leaf peak fractions from anion-exchange chromatography (see Table II). The PEPC was extracted from the H. verticillata leaves harvested during the light period. The C4 sample was taken 288 h into the induction period. The assay was run at pH 7.3 in the absence of dithiothreitol. The apparent K0.5 PEP values were determined from the curves. Data are means ± se, n = 3.

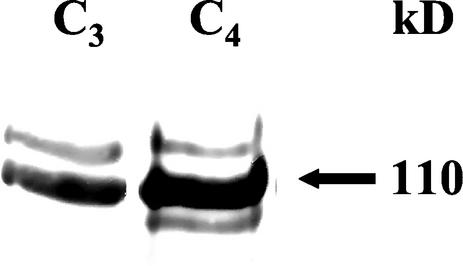

Western analyses showed two prominent immunoreactive bands in both leaf extracts, with the second being much more pronounced in the C4 leaves (Fig. 5). In addition, a third, faster running band was evident only in the C4 leaf extract. The distribution of these bands was in the Mr range of 105,000 to 111,000.

Figure 5.

Western analyses of PEPC from leaves of H. verticillata. Leaves of H. verticillata were harvested midway through their light cycle, C3 at 0 h and C4 at 288 h into the induction period. Six micrograms of protein from the C3 and C4 leaf peak fractions from anion-exchange chromatography (see Table II) was resolved by 5% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and transblotted to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with antibodies raised against maize PEPC. The PEPC signals from C3 and C4 leaves are shown. The kilodalton value of the prominent PEPC band is indicated at the right.

Phylogenetic Analyses

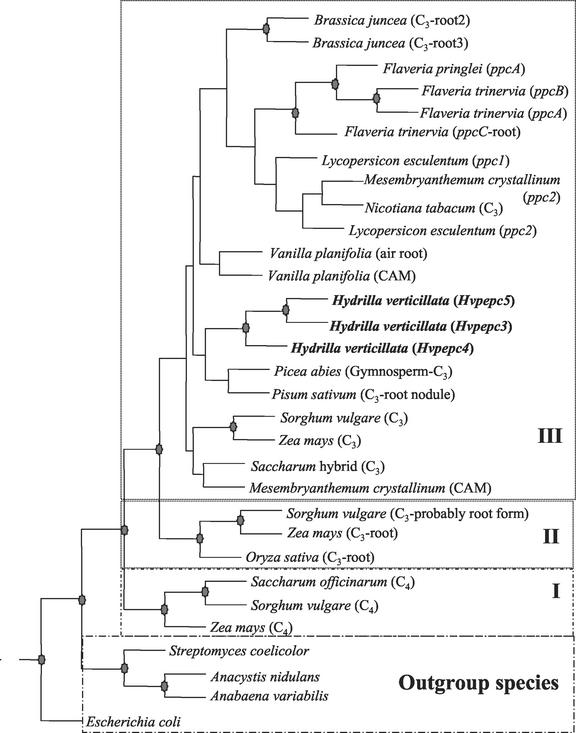

Figure 6 shows the results of a phylogenetic analysis of deduced amino acid sequences with the PHYLIP program (Phylogeny Inference Package, version 3.57c, Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle) using the parsimony algorithm. In addition to the three H. verticillata PEPC sequences, 28 other full-length sequences from GenBank representing 17 different taxa were included. Particular emphasis was placed on selecting species with a set of two or more isoforms, so that diversity of isoform function was represented. Using the PHYLIP or the PAUP package (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony, version 4.0, Sinaur Associates, Sunderland, MA), both the protein distance and protein parsimony methods gave consensus trees that were very similar. For these analyses, the four prokaryotic sequences were taken as the outgroup, showing similarity with the seed plant sequences in the range of 26% to 39%. In all, 943 total characters were considered, and 608 of them were parsimony informative. The consistency and retention indices were 0.71 and 0.63, respectively, indicating low homoplasy or background noise because of convergence or reversion events. The root PEPC isoforms of the graminaceous plants; maize, sorghum (Sorghum vulgare), and rice (Oryza sativa); and the C4 sequences of maize and sorghum apparently diverged independently.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of deduced amino acid PEPC sequences. The PHYLIP package was used to construct a consensus tree with 100 bootstrap replications using the parsimony method. The four prokaryotic species served as the outgroup. The stars at the fork of the tree represent >85% support. The three groupings are: I, C4 graminaceous; II, graminaceous roots; and III, sequences of other higher plants. Deduced amino acid sequences other than H. verticillata were obtained from GenBank/SwissProt.

From this analysis, it appeared that PEPC isoforms can be grouped into three distinct groups that likely share a common ancestor: I, C4 graminaceous; II, graminaceous roots; and III, PEPC isoforms with varying functions from a variety of taxa. Although group III was monophyletic, relationships within it were largely unresolved because the component branches lacked statistical support. Nonetheless, there was good support for several clades, namely Brassica spp., Flaveria spp., Hydrilla spp., and a Sorghum spp./Zea spp. group (C3 PEPC). Within the genus Flaveria, the C3 species Flaveria pringlei ppcA showed a clear divergence from the C4 F. trinervia ppcA, with 100% support. However, the sequences from both the C3 and C4Flaveria spp. fell into the same group as those from H. verticillata. In the case of H. verticillata, Hvpepc3 and Hvpepc5, and Hvpepc4 diverged from a unique common C3 ancestor. It is intriguing that the gymnosperm Norway spruce (Picea abies) along with the root nodule pea (Pisum sativum) and the H. verticillata sequences appear to form a clade that is present regardless of tree construction methods.

DISCUSSION

Photosynthesis in H. verticillata is unique in that, against a C3 background, a C4 cycle is induced but without the development of specialized anatomy that occurs in terrestrial C4 species. This “minimalist” system represents something of a paradox in our concept of C4 photosynthesis. Since the classical C3 × C4 Atriplex spp. hybridization experiments of Björkman et al. (1970), it has been accepted that for a C4 system to concentrate CO2 and to avoid its futile cycling, the biochemical components need to be segregated in specific cell types. H. verticillata was the only exception, but others have been reported recently (Bowes et al., 2002), including Borszczowia aralocaspica, a terrestrial NAD-ME C4 species in which the C4 and Calvin cycles appear to co-exist in different regions of the same cell (Voznesenskaya et al., 2002).

The inducible H. verticillata system provides an excellent opportunity to study the minimum essential biochemical elements to operate a C4 photosynthetic system, such as might be needed to transform a C3 crop plant. Its facultative nature also enables us to examine the genes involved in both the C3 and C4 states, differences in their expression, and variations in the regulatory and catalytic domains of their products.

We have previously described the major physiological and biochemical features of the system (Bowes and Salvucci, 1989; Magnin et al., 1997). Thus, the purpose of this study was to begin to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved, particularly those associated with the induction and role(s) of PEPC, the first element in the C4 pathway. The genes encoding PEPC isoforms in terrestrial plants have been well described, and distinctions can be made among the C3 (non-photosynthetic forms), C4, and CAM isoforms (Lepiniec et al., 1993; Ernst and Westhoff, 1997; Svensson et al., 1997; Cushman and Bohnert, 1999).

Of the three PEPC isoforms from H. verticillata Hvpepc4 was expressed solely in C4 leaves. Several lines of evidence point to this isoform as the photosynthetic PEPC operating in the light. It was only isolated from C4 leaf RNA and was only expressed in C4 leaves, and its expression coincided with the rise in PEPC activity as the C4 system was induced. In addition, its sequence least resembled those of Hvpepc3 or Hvpepc5 that were isolated from C3 leaves and roots, respectively. It also contained the F. trinervia C4 Lys-347, though as noted earlier, this residue is not a very specific determinant of a C4 PEPC isoform. The C4-signature Ser residue was absent from all H. verticillata sequences, and instead, Ala, which is typical of C3 sequences, occurred at this position. Ser appears to be ubiquitous at this position among the C4 isoforms of terrestrial C4 plants, and it plays a role in determining the kinetic characteristics (Bläsing et al., 2000). How the H. verticillata PEPC functions kinetically as a C4 photosynthetic isoform with the C3 Ala at this position, instead of Ser, is an interesting issue that deserves further study.

We recently reported that PEPC in desalted extracts from C3 and C4 H. verticillata leaves differed kinetically in that the C4 leaf enzyme is light activated and is over 10-fold more sensitive to malate inhibition (Bowes et al., 2002). In the present study, the specific activity of C4 leaf PEPC was substantially higher than that from C3 leaves. Among terrestrial plants, PEPC in C4 leaves is light-activated, and its activity is similarly severalfold higher than that from C3 leaves when assayed at a cytosolic-like pH (Gupta et al., 1994).

The Km PEP values for PEPC differ among terrestrial plant C3 and C4 enzymes (O'Leary, 1982). This, however, was not the case for PEPC from C3 and C4 H. verticillata leaves, which had similar K0.5 PEP values that were high and C4-like, confirming much earlier measurements with crude extracts (Nakamura et al., 1983). Bläsing et al. (2000) showed that in site-directed mutagenesis and chimeric constructs of ppcA PEPC from C3 F. pringlei and C4 F. trinervia, the replacement of Ala-774 with Ser increases the K0.5 PEP of the recombinant proteins. They concluded that Ser-774 is a key determinant of C4-like kinetics, including a high K0.5 PEP. Thus, the similarity of H. verticillata K0.5 PEP values might be expected, because the sequences are identical at this site. In contrast, the presence of Ala and high K0.5 values does not support a ubiquitous need for Ser at this position to obtain a C4-like K0.5 PEP.

Hill coefficients for recombinant ppcA PEPCs from C3 and C4 Flaveria spp. indicate the C4 enzyme has greater positive cooperativity (Bläsing et al., 2000). The H. verticillata data parallel this, in that the C4 leaf PEPC was strongly homotropic with PEP acting as a positive modulator. A similar situation exists with maize (Tovar-Mendez et al., 1998). The in vivo role for allosteric regulation of the C4 photosynthetic isoform is undetermined. However, PEPC operating in a C4 CCM may need enhanced capacity to respond rapidly as metabolites fluctuate with transient changes in the environment.

The expression pattern and kinetic data point to Hvpepc4 as the C4 photosynthetic PEPC. What then is the role for Hvpepc3 in the leaves? H. verticillata leaves can fix CO2 in the dark, at 12% of the light rate in the case of C4 leaves, and they accumulate malate (Reiskind et al., 1997; J.B. Reiskind, S.K. Rao, and G. Bowes, unpublished data). The ability of a PEPC that is not light-regulated to scavenge inorganic carbon at night when concentrations rise could be another factor in the plant's carbon economy in habitats where dissolved CO2 becomes a major daytime limitation.

The sequence similarity between Hvpepc3 and 5 might suggest that the same gene encodes them both. However, this is unlikely because all of the 3′-UTR sequences analyzed to date from independent clones of three organ sources, i.e. leaf, root, and subterranean and axillary turions, revealed (a) three distinct 3′-UTR categories; (b) that the Hvpepc5-like sequences were the same length and were 99% homologous; and (c) that a specific polyadenylation signal site at a common position (nt 3,198 to 3,203 in Hvpepc3 and Hvpepc5) was present.

The three full-length cDNA H. verticillata sequences were all very similar (95%–99%). A comparable situation is seen in Kalanchoe blossfeldiana where two pairs of isogenes encode highly similar C3- and CAM-specific PEPC isoforms, with the slight deviations being attributed to gene duplication or the hybrid status of the plant in which the parental genomes are expressed (Gehrig et al., 1995). Gene duplication could be the case in H. verticillata, because the plants in Florida are dioecious female diploids (2n = 16) and are materlineal (Langeland et al., 1992). Variable length and base pair differences of the UTRs, particularly at the 3′ end where message stability is an issue, may determine functional properties of encoded proteins (Ingelbrecht et al., 1989). These could be elements governing functional differences among the H. verticillata isoforms. In addition, there were two initiation codons downstream of the leader sequence, which are seen in other PEPC sequences (Relle and Wild, 1996). If translation is initiated from the second Met, then the motif upstream of the Ser residue is absent and the interaction of this residue with PEPC-protein kinase and the subsequent phosphorylation would not occur.

All but two plant PEPCs in GenBank contain a Cys residue at position 196, but Ser occurred in Hvpepc5. At 891, Arg is the residue most commonly found, and it was conserved in Hvpepc5, but in both Hvpepc3 and Hvpepc4, Glu was substituted. The Met-150 in Hvpepc4 was also unusual, because the conserved residue is Leu. It is not clear whether these divergences influence the kinetic and regulatory characteristics of the isoforms. As noted earlier, the absence of the C4 signature Ser is a very unusual feature of the H. verticillata photosynthetic PEPC sequence.

The deduced amino acid sequences of the three full-length PEPC isoforms indicated that they had similar pIs and Mrs. This may be why Q-Sepharose chromatography of C4 leaf extracts did not yield two peaks, even though northern analyses showed the presence of two isoforms. Of the immunoreactive bands resolved on SDS-PAGE, only the second corresponded with the deduced Mr of the three identified isoforms. The others may be cross-reacting proteins or other isoforms. Similar banding patterns for PEPC have been observed in Egeria spp. and Sorghum spp. with the conclusion that they represented different PEPC isoforms (Casati et al., 2000; Nhiri et al., 2000).

The phylogenetic analyses indicated that the H. verticillata sequences, including Hvpepc4, were divergent from the C4 graminaceous PEPCs. The C4 F. trinervia PEPC similarly grouped with C3 and CAM PEPCs from monocots and eudicots. Thus, the functional diversity of PEPC isoforms was not fully reflected in the branching pattern. It is possible that the C4 form of PEPC diverged before the monocot/ eudicot split 200 million years ago (mya) but after the gymnosperm and angiosperm divergence 330 mya (Wolfe et al., 1989; Relle and Wild, 1996). The PEPC from Norway spruce, which is suggested to be part of the N-fixation system in spruce roots (Relle and Wild, 1996) and, thus, is likely related to the pea root nodule PEPC, was potentially a sister to the H. verticillata isoforms and was closer to them than to other monocot C3 or CAM PEPCs. If so, the H. verticillata PEPCs may represent ancestral sets of genes that emerged before angiosperm divergence and may provide clues to C4 evolution in monocots. It should be noted that monocot PEPC genes may have diverged early into the C4 type and were not necessarily accompanied by C4 photosynthesis (Kawamura et al., 1992).

Members of the Hydrocharitaceae, to which H. verticillata belongs, were adapted to an aquatic environment 120 mya (Sculthorpe, 1967). Aquatic habitats may experience very low daytime CO2 to O2 ratios, particularly in heavily vegetated areas (Bowes and Salvucci, 1989), so submersed species likely experienced low [CO2] before terrestrial plants encountered such conditions. Some submersed species show evidence of C4 photosynthesis (Bowes et al., 2002), and it is possible an early selection pressure led to its presence in submersed species, like H. verticillata, before its advent in terrestrial plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) Royle sprigs 6 cm long were incubated with a photon irradiance of 300 μmol m−2 s−1 under a 14-h 30°C photoperiod/22°C scotoperiod to limit daytime [CO2] and induce C4 photosynthesis, or a 10-h 15°C photoperiod/10°C scotoperiod regime to maintain the C3 state (Magnin et al., 1997). Induction was followed over time by determining the increase in PEPC activity, and leaves in the C3 and C4 state were harvested at intervals. Rooting of H. verticillata sprigs was achieved by planting them in sand under a 12-h 25°C photoperiod/25°C scotoperiod. Roots were harvested 3 or 4 weeks after planting.

PEPC Assay, Western-Blot Analyses, and Protein Purification

Enzyme activities for maximal activity and western blots were performed as previously described (Magnin et al., 1997). For the latter, polyclonal antibodies raised against maize PEPC were used. K0.5 PEP values and maximal velocities were assessed at pH 7.3 in the absence of dithiothreitol with [PEP] ranging from 0 to 2 mm. Protein was determined by the Bradford method with γ-globulin as the standard (Bradford, 1976). PEPC was purified by (NH4)2SO4 fractionation (25%–55% [w/v]) followed by desalting on PD-10 columns (Amersham Biosciences AB, Uppsala) equilibrated with 20 mm PIPES, pH 7.0, 10 mm MgCl2, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol. The resulting eluate was applied to a 1-mL Q-Sepharose FF column (Amersham Biosciences AB) equilibrated with running buffer (RB; 20 mm PIPES, pH 7.0, and 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol). After a RB wash, the bound protein was eluted with a 30-mL linear KCl gradient (0–400 mm) in RB and collected in 0.5-mL fractions for PEPC assay.

Cloning and cDNA Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from C4 leaves, roots, subterranean and axillary turions (Qiagen RNeasy Kit, Qiagen USA, Valencia, CA), and RACE-ready cDNA was prepared from it using the SMART RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). PEPC-specific primers 8F (5′-GCGAAGCAATATGGAGTGAAGTTGA-3′; corresponding to nt 79–103) and 11R (5′-TTGTACATTGTACCCTGGGTCCCTT-3′; nt 933–957) were designed from the partial cDNA sequence Hvpepc2 obtained previously (Rao et al., 1998). TA cloning of the RACE products was performed with the TOPO-XL PCR Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). PEPC-specific inserts were initially confirmed by screening with the DIG-oligo tailed primer 11R (Roche Diagnostics/Roche Applied Science). From partial sequencing of the 5′ end of several of these clones, two primers, 3F (5′-CGCGTCTGTTCTGATGGCGTC-3′; nt 47–67) and 4F (5′-TGCGCGAGTGTCCCGATGG3′; nt 47–65), were designed and DIG-tailed to aid in further screening. Clones from this screening were partially sequenced to identify the extreme 5′- and 3′-cDNA ends, so that specific primers could be designed to amplify full-length cDNAs encoding PEPC isoforms. A primer walking strategy was used for sequencing. The full-length sequence data reported here are in the GenBank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information under the accession numbers AF271161 (Hvpepc3), AF271162 (Hvpepc4), and AF271163 (Hvpepc5).

Northern Analyses

For northern analyses, a total of 1 μg of RNA per lane, extracted from leaves (RNeasy Plant Kit, Qiagen USA), was separated on a 1.2% (w/v) agarose formaldehyde gel (Maniatis et al., 1982). A downward capillary blotting method was employed to transfer the RNA to a positively charged nylon membrane using 10× SSC as the transfer buffer (Roche Diagnostics/Roche Applied Science). The bound RNA was UV cross-linked for 3 min and hybridized overnight with the appropriate DIG-labeled RNA probe in standard hybridization buffer with 50% (v/v) formamide. The stringency washes and detection were carried out following the DIG-System User's Guide (Roche Diagnostics/Roche Applied Science). For stripping the probes from the hybridized membranes, two washes at 80°C for 1 h each were performed with 50% (v/v) formamide and 5% (w/v) SDS in 50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.5.

Syntheses of Antisense RNA Probes

Three different antisense RNA probes were synthesized following the protocol of the DIG RNA labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics/Roche Applied Sciences). PCR amplified regions from either full- or partial-length cDNA clones were inserted into the vector pCR-XL-TOPO (Invitrogen) in a manner such that the transcription template included the T7 promoter/priming site at the 3′ end. The specific probes for Hvpepc3 (nt 2,948–3,368) and Hvpepc4 (nt 2,944–3,197) were derived from their respective full-length cDNA clones with the primer pairs PRB-3P (5′-TGCTGGCATGCAGAACACTGGTTAACC-3′) and T7-PCR primer (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′). The region (nt 47–1,799) of the consensus probe was PCR amplified from a 1.8-kb partial cDNA clone of Hvpepc3 with the aid of primer pairs 3F (5′-CGCGTCTGTTCTGATGGCGTC-3′) and T7-PCR primer.

Sequence Analyses and Phylogeny Inference

Standard sequence compiling and analyses, including pair-wise comparison of nt and deduced amino acids, were performed using the Wisconsin package (v10.1, Genetics Computer Group, Madison, WI). For phylogenetic analysis, PHYLIP v3.57 (Felsenstein, 1989) and PAUP programs were used. The deduced amino acid sequences of the three full-length H. verticillata PEPC isoforms and 28 previously published PEPC sequences from GenBank were used to build the tree. The species and accession numbers of the 28 PEPC sequences are: Anacystis nidulans (M11198), Anabaena variabilis (M80541), Norway spruce (Picea abies; X79090), pea (Pisum sativum; D64037), rice (Oryza sativa; AF271995), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; X59016), common ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum; ppc2, X14588; ppc1, X14587), Vanilla planifolia (ppcV1, X87148; ppcV2, X87149), maize (Zea mays; C3, X61489; root, AB012228; C4, X03613), sorghum (Sorghum vulgare; CP21, X63756; CP46, X65137; CP28, X59925), Flaveria trinervia (ppcA, X64143; ppcB, AF248079; ppcC, AF248080), Flaveria pringlei (ppcA, Z48966), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum; C4, AJ293346), Saccharum hybrid var H32–8560 (C3, M86661), tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum; ppc1, AJ243416; ppc2, AJ243417), brown mustard (Brassica juncea; ppc2, AJ223496; ppc3, AJ223497), Streptomyces coelicolor (CAB95920), and Escherichia coli (AE000469).

The predicted protein sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL program (Thompson et al., 1994), and the sequences were edited to include only the unambiguously aligned sections. Two different methods in the PHYLIP package, NEIGHBOR (neighbor-joining based on the output file from PROTDIST distance matrix analysis program) and PROTPARS (maximum parsimony), were used with a bootstrap analysis of 100 replications to determine and compare the confidence level of branches within the phylogenetic tree.

Distribution of Materials

Upon request, all novel materials described in this publication will be made available in a timely manner for noncommercial research purposes, subject to the requisite permission from any third-party owners of all or parts of the material. Obtaining any permissions will be the responsibility of the requestor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Michael Salvucci of the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Western Cotton Research Laboratory (Tucson, AZ) for the generous gift of the antibody to PEPC from maize. We also thank Drs. Walter Judd and Mark Whitten of the University of Florida Department of Botany (Gainesville, FL) and the Florida Museum of Natural History (Gainesville, FL), respectively, for their advice on phylogenetic tree construction.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. IBN–9604518) and by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiatives Competitive Grants Photosynthesis and Respiration Program (grant no. 93–37306–9386).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.008045.

LITERATURE CITED

- Björkman O, Pearcy RW, Nobs MA. Hybrids between Atriplexspecies with and without β-carboxylation photosynthesis: photosynthetic characteristics. Carnegie Inst Wash Year Book. 1970;69:640–648. [Google Scholar]

- Bläsing OE, Westhoff P, Svensson P. Evolution of C4 phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in Flaveria, a conserved serine residue in the carboxyl-terminal part of the enzyme is a major determinant for C4-specific characteristics. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27917–27923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909832199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes G, Rao SK, Estavillo GM, Reiskind JB. C4 mechanisms in aquatic angiosperms: comparisons with terrestrial C4systems. Funct Plant Biol. 2002;29:379–392. doi: 10.1071/PP01219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes G, Salvucci ME. Plasticity in the photosynthetic carbon metabolism of submersed aquatic macrophytes. Aquat Bot. 1989;34:232–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casati P, Lara MV, Andreo CS. Induction of a C4-like mechanism of CO2 fixation in Egeria densa, a submersed aquatic species. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:1611–1622. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chollet R, Vidal J, O'Leary MH. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase: a ubiquitous highly regulated enzyme in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:273–298. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman JC, Bohnert HJ. Crassulacean acid metabolism: molecular genetics. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:305–332. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst K, Westhoff P. The phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (ppc) gene family of Flaveria trinervia (C4) and F. pringlei (C3): molecular characterization and expression analysis of the ppcB and ppcC genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;34:427–443. doi: 10.1023/a:1005838020246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP: phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrig H, Taybi T, Kluge M, Brulfert J. Identification of multiple isogenes in leaves of the facultative Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) plant Kalanchoe blossfeldianaPoelln. cv. Tom Thumb FEBS Lett. 1995;377:399–402. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Ku MSB, Lin J-H, Zhang D, Edwards GE. Light/dark modulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in C3 and C4species. Photosynth Res. 1994;42:133–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02187124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans J, Westhoff P. Homologous genes for the C4 isoform of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in a C3 and a C4 Flaveriaspecies. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;234:275–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00283848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelbrecht ILW, Herman LMF, Dekeyser RA, Van Montagu MC, Depicker AG. Different 3′ end regions strongly influence the level of gene expression in plant cells. Plant Cell. 1989;1:671–680. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.7.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura T, Shigesada K, Toh H, Okumura S, Yanagisawa S, Isui K. Molecular evolution of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase for C4photosynthesis in maize: comparison of its cDNA sequence with a newly isolated cDNA encoding an isozyme involved in the anapleurotic function. J Biochem. 1992;112:147–154. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg EA. Phylogenetic aspects of the evolution of C4photosynthesis. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, editors. C4 Plant Biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 411–444. [Google Scholar]

- Ku MSB, Agarie S, Nomura M, Fukayama H, Tsuchida H, Ono K, Hirose S, Toki S, Miyao M, Matsuoka M. High-level expression of maize phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in transgenic rice plants. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:76–80. doi: 10.1038/5256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langeland KA, Shilling DG, Carter JL, Laroche FB, Steward KK, Madiera PT. Chromosome morphology and number in various populations of Hydrilla verticillata. Aquat Bot. 1992;42:253–263. [Google Scholar]

- Lepiniec L, Keryer E, Philippe H, Gadal P, Cretin C. Sorghum phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase gene family: structure, function and molecular evolution. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;21:487–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00028806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepiniec L, Vidal J, Chollet R, Gadal P, Cretin C. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase: structure, regulation and evolution. Plant Sci. 1994;99:111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Magnin NC, Cooley BA, Reiskind JB, Bowes G. Regulation and localization of key enzymes during the induction of Kranz-less, C4-type photosynthesis in Hydrilla verticillata. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:1681–1689. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.4.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T, Fritsch EF, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mann CC. Crops scientists seek a new revolution. Science. 1999;283:310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M, Sanada Y. Expression of photosynthetic genes from the C4plant, maize, in tobacco. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;225:411–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00261681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Salvucci ME, Bowes G. Glucose-6-phosphate activation and malate inhibition of HydrillaPEP carboxylase. Plant Physiol. 1983;72:S124. [Google Scholar]

- Nhiri M, Bakrim N, El Hachimi-Messouak Z, Echevarria C, Vidal J. Posttranslational regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase during germination of Sorghum seeds: influence of NaCl and l-malate. Plant Sci. 2000;151:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary M. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase: an enzymologist's view. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1982;33:297–315. [Google Scholar]

- Rao SK, Reiskind JB, Magnin NC, Bowes G. Exploitation of non-photosynthetic enzymes to operate a C4-type CCM when [CO2] is low. In: Garab G, editor. Photosynthesis: Mechanism and Effects. Vol. 5. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 3565–3570. [Google Scholar]

- Reiskind JB, Madsen TV, Van Ginkel LC, Bowes G. Evidence that inducible C4-type photosynthesis is a chloroplastic CO2 concentrating mechanism in Hydrilla, a submersed monocot. Plant Cell Environ. 1997;20:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Relle M, Wild A. Molecular characterization of a phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase in the gymnosperm Picea abies(Norway spruce) Plant Mol Biol. 1996;32:923–936. doi: 10.1007/BF00020489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sculthorpe CD. The Biology of Aquatic Vascular Plants. London: Edward Arnold, Ltd; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson P, Bläsing OE, Westhoff P. Evolution of the enzymatic characteristics of C4 phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase-a comparison of the orthologous ppcA phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylases of Flaveria trinervia (C4) and Flaveria pringlei (C3) Eur J Biochem. 1997;246:452–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tovar-Mendez A, Rodriguez-Sotres R, Lopez-Valentin DM, Munoz-Clares RA. Reexamination of the roles of PEP and Mg2+ in the reaction catalysed by the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase from leaves of Zea mays: effects of the activators glucose 6-phosphate and glycine. Biochem J. 1998;332:633–642. doi: 10.1042/bj3320633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voznesenskaya EV, Franceschi VR, Kiirats O, Freitag H, Edwards GE. Kranz anatomy is not essential for C4plant photosynthesis. Nature. 2001;414:543–546. doi: 10.1038/35107073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Gouy M, Yang YW, Sharp PM, Li WH. Date of monocot-dicot divergence estimated from chloroplast DNA sequence data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6201–6205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]