Abstract

In flowering plants, pollination of the stigma sets off a cascade of responses in the distal flower organs. Ethylene and its biosynthetic precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) play an important role in regulating these responses. Because exogenous application of ethylene or ACC does not invoke the full postpollination syndrome, the pollination signal probably consists of a more complex set of stimuli. We set out to study how and when the pollination signal moves through the style of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) by analyzing the expression patterns of pistil-expressed ACC-synthase and -oxidase genes. Results from this analysis showed that pollination induces high ACC-oxidase transcript levels in all cells of the transmitting tissue. ACC-synthase mRNA accumulated only in a subset of transmitting tract cells and to lower levels as compared with ACC-oxidase. More significantly, we found that although ACC-oxidase transcripts accumulate to uniform high levels, the ACC-synthase transcripts accumulate in a wave-like pattern in which the peak coincides with the front of the ingrowing pollen tube tips. This wave of ACC-synthase expression can also be induced by incongruous pollination and (partially) by wounding. This indicates that wounding-like features of pollen tube invasion might be part of the stimuli evoking the postpollination response and that these stimuli are interpreted differently by the regulatory mechanisms of the ACC-synthase and -oxidase genes.

Pollination induces a myriad of responses in the whole flower that contribute to the successful sexual reproduction in higher plants. This cascade of responses or “postpollination syndrome” includes wilting of the petals (Larsen et al., 1995), mRNA poly(A+) tail shortening and cell deterioration in the transmitting tissue of the style (Herrero and Dickinson, 1979; Wang et al., 1996), and ovary development (Zhang and O'Neill, 1993). The responses of the distal floral organs to the pollination event at the stigma surface are regulated by interorgan signaling. Compounds implied in signaling are the gaseous hormone ethylene and its precursor 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC; Woltering et al., 1994; O'Neill, 1997).

Ethylene is made via a two-step biosynthetic route that starts with the conversion of the Met derivative S-adenosyl-l-Met to ACC and 5′-methyl-thioadenosine by ACC-synthase. Next, ACC is oxidized by ACC-oxidase to form ethylene, CO2, and HCN. Rate limiting in this route is ACC-synthase (Yang and Hoffman, 1984).

The ethylene that is produced upon pollination is characterized by two peaks occurring at 3 and 36 h after pollination (HAP; O'Neill, 1997; De Martinis et al., 2002). The first ethylene burst evolves from the stigma and can be attributed mainly to direct conversion of pollen-borne ACC (Hill et al., 1987; Lindstrom et al., 1999) by ACC-oxidase that is abundantly present in the stigma (O'Neill, 1997). The second peak of ethylene is produced by flower organs that are distal to the stigma, like the style, the ovary, and the petals, and can mainly be attributed to endogenous ACC-synthase and -oxidase activities. Importantly, these activities correlate closely with the transient increase in expression of the corresponding genes (Tang and Woodson, 1996; O'Neill, 1997; Bui and O'Neill, 1998; Sanchez and Mariani, 2002).

The above observations imply that between the two peaks of ethylene production, a pollination signal must be transmitted from the stigma to the distal flower organs to induce ACC-synthase and -oxidase gene expression, ethylene production, and, finally, to actuate the full postpollination syndrome. The exogenous application of ethylene or ACC or both failed to evoke the complete set of postpollination responses (O'Neill, 1997). This suggests that a more complex set of stimuli is involved; for example, a combination of ethylene and other wounding responses of the style to the invading pollen tubes (Woltering et al., 1997; Lantin et al., 1999).

To study how and when the pollination signal travels through the pistil, we have characterized the expression pattern of pistil-expressed ACC-synthase and -oxidase genes from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). We show that before pollination, ACC-oxidase transcripts accumulate in all cells of the transmitting tissue, whereas ACC-synthase transcripts accumulate in a subset of the transmitting tract cells. Importantly, we found that after pollination and during the progamic phase, the ACC-oxidase transcripts accumulate to a high level throughout the style, whereas ACC-synthase transcripts accumulate in a wave-like pattern along the style that correlates with the ingrowing pollen tubes. This phenomenon is independent of incongruity and can be mimicked during the first 12 h by wounding, albeit at a lower level. These findings suggest that the physics of pollen tube invasion might be a part of the pollination response and have a differential effect on key enzymes in the ethylene biosynthesis pathway.

RESULTS

ACC-Synthase and -Oxidase Transcripts Display Tissue- and Developmental-Specific Accumulation Patterns

We isolated ACC-synthase (ACCS2) and ACC-oxidase (tobacco ethylene-forming enzyme [TEFE]) cDNAs from a pollinated tobacco stigma and style cDNA library (see “Materials and Methods”) to use as tools to study how the pollination signal moves through the pistil. ACCS2 shares 79% identity at amino acid level with another ACC-synthase from tobacco (Liu et al., 1998) and TEFE shares 91% identity at amino acid level to ethylene-forming enzyme (EFE) from tobacco (Knoester et al., 1995). Genomic DNA-blot analyses indicated that both ACCS2 and TEFE are part of a small gene family (data not shown).

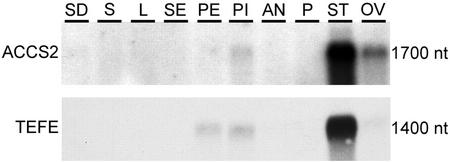

We studied the tissue-specific accumulation pattern of ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts by hybridizing ACCS2 and TEFE cDNAs to gel blots containing poly(A+) RNA from seedlings and various tissues (Fig. 1). The ACCS2 probe detected transcripts of 1,700 nucleotides in the lanes containing mRNA from pistils, from ovaries at 12 HAP, and highest hybridization signal was found in 12-HAP stigmas and styles. ACCS2 did not hybridize to mRNA from vegetative tissues, sepals, petals, anthers from flowers at stage 12, and pollen (Fig. 1). The TEFE probe detected transcripts of 1,400 nucleotides in mRNA from petals, pistils, and 12-HAP ovaries. Most ACC-oxidase transcripts were detected in 12-HAP stigmas and styles. No hybridization signal was detected in lanes containing vegetative tissues, sepal, anther, and pollen mRNA (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Accumulation of ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts in various plant tissues. Each lane contained 1 μg of poly(A+) RNA from seedlings (SD), stems (S), leaves (L), sepals (SE), petals (PE), flower stage 12 pistils (PI), flower stage 12 anthers (AN), mature pollen (P), 12-HAP stigmas and styles (ST), and 12-HAP ovaries (OV). Autoradiogram exposure times: 48 h for ACCS2 probe and 3 h for TEFE probe.

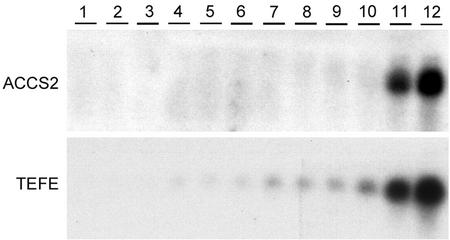

Figure 2 shows the developmental accumulation pattern of ACC-synthase and -oxidase mRNA in stigmas and styles from flowers at stages 1 to 12 (see “Materials and Methods” for description of flower stages). A weak ACCS2 hybridization signal was first detected at flower stage 8 and hybridization levels increased sharply at stages 11 and 12. TEFE hybridization signal was first detected in stigmas and styles at flower stage 3 and gradually increased in intensity toward stage 12 (Fig. 2). In the ovary, both transcripts accumulated late during development (data not shown). Taken together, these results show that ACC-oxidase transcripts start to accumulate relatively early during development, whereas ACC-synthase transcripts do not accumulate until maturity.

Figure 2.

Accumulation of ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts during development of the stigma and style. Each lane contained 20 μg of total RNA from stigma and style of flower stages 1 through 12 (see “Materials and Methods”). Autoradiogram exposure times: 2 d.

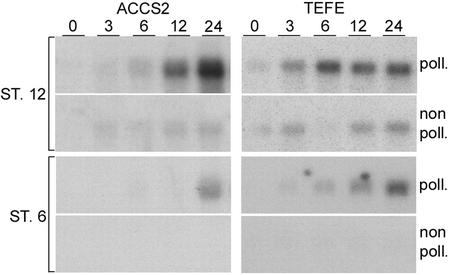

Pollination Induces ACC-Synthase and -Oxidase Transcript Accumulation

To determine whether stigma/style ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcript levels are modulated by pollination, we hybridized ACCS2 and TEFE probes to blots containing RNA from mature stigmas and styles at various time points after pollination (Fig. 3). Within 3 to 6 HAP, ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcript levels had increased and continued to rise thereafter. By contrast, in non-pollinated stigma/styles, transcript levels remained low and increased somewhat at 24 HAP (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcript accumulation induction in flower stage 12 and 6 stigmas and styles. Each lane contained 5 μg of total RNA of 0-, 3-, 6-, 12-, and 24-HAP stigmas and styles of flower stage 12 or 6. Autoradiogram exposure times: stage 12, 3 d for ACCS2 and 1 d for TEFE probe; and stage 6, 3 d for ACCS2 and 1 d for TEFE probe.

To investigate whether this pollination response depended on the developmental stage, ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcript accumulation of pollinated stigmas and styles from flowers at stage 6 was analyzed. At stage 6, the secretory zone and the transmitting tract of the pistil have developed and are receptive and capable of supporting pollen germination and tube growth (Kuboyama et al., 1994; Wolters-Arts et al., 1996; Sanchez and Mariani, 2002). The results in Figure 3 show that at 0 HAP, no ACCS2 and some TEFE hybridization signal were present. After pollination, ACC-oxidase transcripts had started to accumulate within 3 h, which was similar to the transcript accumulation response in mature pollinated stigmas and styles. However, the ACC-synthase transcript level did not increase until 24 HAP. These data show that pollination induces the mature and immature stigma and style to accumulate ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts. However, in a pistil at stage 6, this response seems to be delayed in the case of ACC-synthase expression.

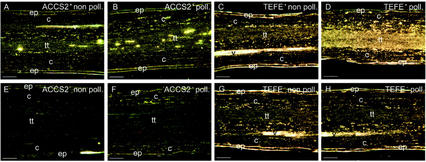

Tissue-Specific ACC-Synthase and -Oxidase Accumulation in Pollinated Styles

To study the effect of pollination on the tissue-specific accumulation of ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts, we performed an in situ hybridization experiment (Fig. 4). ACCS2 did not hybridize to the epidermis, cortex, and vascular tissue in both non-pollinated and pollinated styles (Fig. 4, A, B, E, and F). However, ACCS2 hybridization signal was detected in few and apparently randomly scattered cells in the transmitting tissue. In pollinated styles, ACC-synthase transcript accumulation was detectable in a larger number of cells as compared with non-pollinated styles (Fig. 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

ACC-synthase and -oxidase mRNA localization patterns in pollinated and non-pollinated styles. The lower part of 16-HAP or non-pollinated styles were fixed, embedded in paraffin, sliced into 10-μm sections, and hybridized with 33P-labeled sense or antisense probes as described in “Materials and Methods.” Photographs were taken by dark-field microscopy. A and B, Hybridization of ACCS2 antisense probe with non-pollinated (A) and pollinated (B) styles. C and D, Hybridization of TEFE antisense probe with non-pollinated (C) and pollinated (D) styles. E and F, Hybridization of ACCS2 sense probe with non-pollinated (E) and pollinated (F) styles. G and H, Hybridization of TEFE sense probe with non-pollinated (G) and pollinated (H) styles. Emulsion exposure times: 44 d for ACCS2 probes and 4 d for TEFE probes. c, Cortex; ep, epidermis; tt, transmitting tissue; v, vascular bundle.

In contrast to ACCS2, the TEFE probe hybridized to transcripts in all cells of the transmitting tissue in non-pollinated and pollinated styles. In pollinated styles, the hybridization signal was higher as compared with non-pollinated styles and, in addition, TEFE hybridization signal was also detected in the cortex cells. No hybridization signal was detected in cortex cells of non-pollinated styles, nor was one detected in vascular tissue and epidermis (Fig. 4, C, D, G, and H). Taken together, these data show that ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts accumulate in different patterns within the style and that the pollination-induced transcript accumulation is primarily the result of increased expression levels within the same tissue rather than additional tissues expressing ACC-synthase and -oxidase.

Pollination Induces Dynamic Accumulation Patterns of ACC-Synthase and -Oxidase Transcript in the Stigma and along the Style

As ACC-synthase is considered rate limiting to the production of the ethylene signal, and because it is up-regulated together with ACC-oxidase upon congruous pollination, we investigated whether the growth of incongruous pollen tubes has a similar effect. More specifically, we wanted to elucidate how the presence of pollen tube tips in a given place in the style or wounding relates to ACC-synthase and -oxidase gene expression. To this end, transcript accumulation responses to three different treatments were analyzed: (a) pollination with tobacco pollen, (b) pollination with Petunia hybrida pollen, and (c) wounding by inserting a hypodermic needle in the stigma and a part of the style. Non-pollinated tobacco pistils served as a negative control. Pistils pollinated with tobacco pollen produced ethylene with two characteristic peaks at 3 and 36 HAP (De Martinis et al., 2002; data not shown) and the tubes reached the ovary and effected fertilization within 36 h. Pollination with P. hybrida caused a similar ethylene peak at 3 h, but the second peak was delayed by 12 h (De Martinis et al., 2002; data not shown). P. hybrida pollen tubes grew at approximately the same speed as compared with tobacco, but P. hybrida pollen tubes did not reach the ovary until 42 HAP because they paused at the transition zone that separates the stylar transmitting tract from the ovary. Wounding also caused an early ethylene peak, albeit at a lower level (Hill et al., 1987; Woltering et al., 1997; Goto et al., 1999) and flowers produced sustained elevated levels of ethylene for several days after wounding (Hoekstra and Weges, 1986).

We isolated RNA from four consecutive 8-mm pieces of pistil harvested at different time intervals after pollination. Together, the pistil segments encompassed the stigma (segment 1), the upper and middle part of the style (segments 2 and 3), and the lower part of the style including the style-ovary transition zone (segment 4). We analyzed the levels of ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts in these segments and quantified the levels by calibrating the RNA blots with dilution series of in vitro-transcribed ACCS2 and TEFE cRNA on each gel (Cornelissen and Vandewiele, 1989).

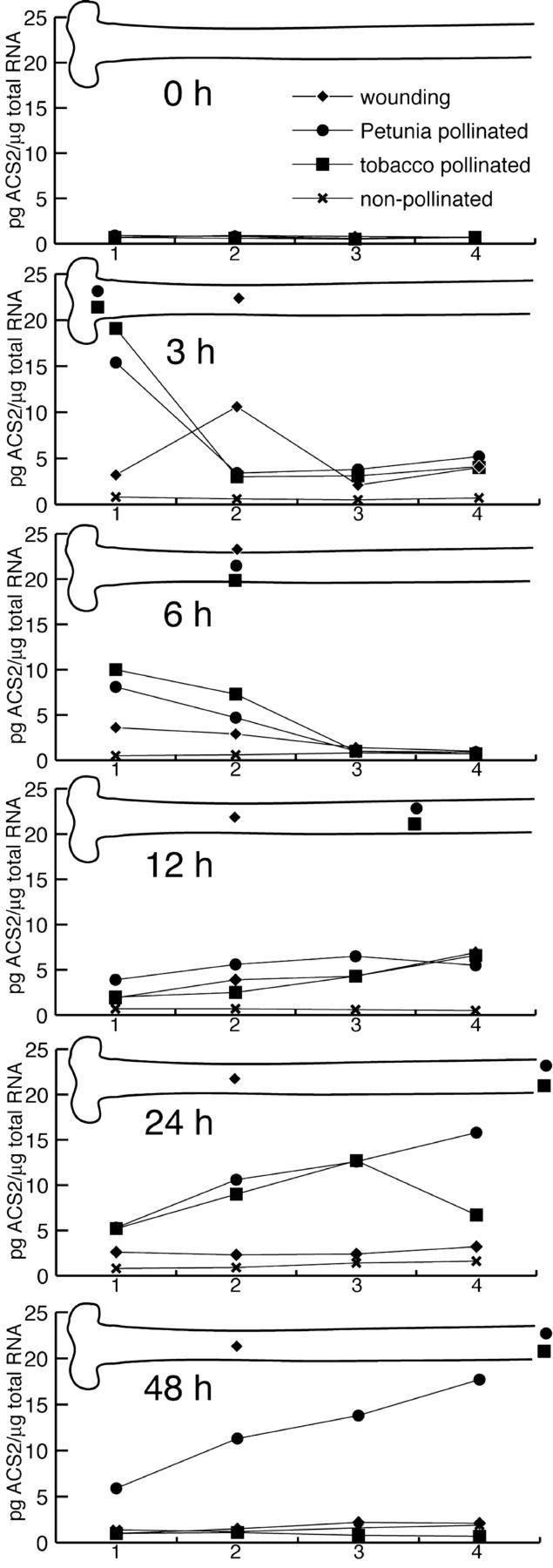

ACC-Synthase Transcript Accumulation Patterns

Figure 5 illustrates the different ACC-synthase accumulation profiles induced by the different treatments. In non-pollinated styles, no transcripts were detected above the threshold (2 pg μg−1 total RNA) until 24 h, at which time point the mRNA levels rose slightly in all parts of the style. Pollination with tobacco pollen and with P. hybrida pollen, instead, caused similar wave-like ACC-synthase transcript accumulation patterns until 24 HAP. At 3 HAP, although the tips of the pollen tubes were located only in the stigma, ACC-synthase mRNA levels were increased in all style parts, and the highest level was detected in the stigma (19 pg μg−1 total RNA; Fig. 5). At 6 HAP, pollen tubes had grown into the uppermost part of the style and ACC-synthase mRNA was detectable in these two parts, but undetectable in the middle and lower parts of the style, below the tube tips (Fig. 5). At 12 HAP, pollen tubes had just reached the lowest part of the style. By then, ACC-synthase transcripts were present in the whole style and their levels were slightly higher in the middle and lower style parts. At 24 HAP, the tobacco pollen tubes had grown through the whole style and the ACC-synthase transcripts accumulated to a higher level in a pattern similar to 12 HAP. At 48 HAP, these transcripts were no longer detectable in styles pollinated with tobacco pollen. However, in the styles pollinated with P. hybrida pollen, ACC-synthase mRNAs were still present at the same level and in the same pattern as at 24 HAP (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

ACC-synthase mRNA accumulation patterns in stigma and style parts at different time intervals after congruous and incongruous pollination and after wounding. Graphical representation of ACC-synthase transcript accumulation levels in four consecutive segments of non-pollinated (X), tobacco-pollinated (▪), P. hybrida-pollinated (●), and wounded (♦) pistils at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after treatment. Segment one represents the stigma and segments two, three, and four represent upper, middle, and lower style (including the style-ovary transition zone), respectively. The accumulation levels are expressed in picograms per microgram total RNA and were obtained from calibrated RNA gel blots as described in “Materials and Methods.” In the pistil drawing over each graph, the position of the front of the pollen tube tips or needle is indicated by the respective symbol. Autoradiogram exposure times: 1 week for non-pollinated pistils and 2 d for other treatments.

Wounding generally caused lower ACC-synthase mRNA accumulation levels, as compared with pollination. From 3 to 12 hours after wounding, the accumulation patterns were largely similar, albeit at a lower level, to those observed in pollinated styles. The only difference was observed at 3 h after wounding, when the highest ACC-synthase level was observed in the upper part of the style, corresponding to the position of the tip of the needle. A similar peak of expression was found at 3 HAP with both types of pollen, suggesting that in all three cases this might be because of wounding effect. At 24 and 48 h after wounding, ACC-synthase accumulation patterns were different from the pollination-induced patterns; namely, low transcript levels were present throughout the style (Fig. 5).

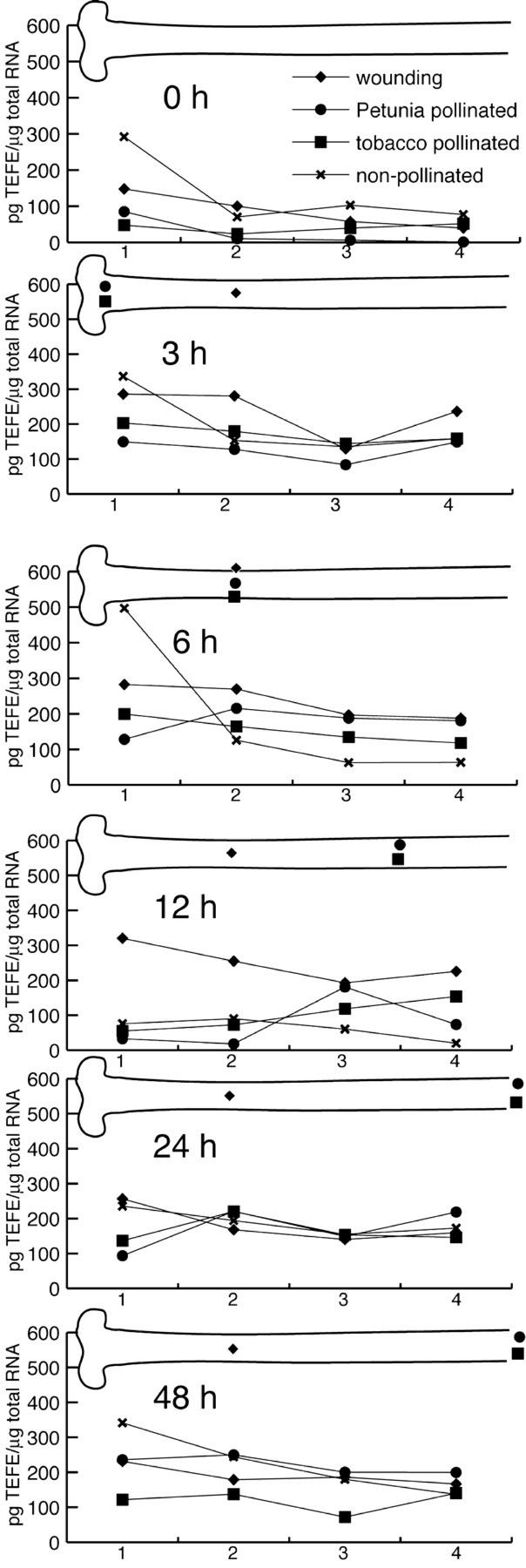

ACC-Oxidase Transcript Accumulation Patterns

Results in Figure 6 show that in general, ACC-oxidase mRNA accumulated to much higher levels as compared with ACC-synthase (highest levels were 500 and 19 pg μg−1 total RNA, respectively; Figs. 5 and 6). In non-pollinated pistils, ACC-oxidase mRNA was detected in all style parts and, until 6 h, levels were very high in the stigma (500 pg μg−1 total RNA) after which they decreased, at 12 h, to below 100 pg μg−1 total RNA. At 24 and 48 h, equal levels were present in all style parts (200–300 pg μg−1 total RNA).

Figure 6.

ACC-oxidase mRNA accumulation patterns in stigma and style parts at different time intervals after congruous and incongruous pollination and after wounding. Graphical representation of ACC-oxidase transcript accumulation levels in four consecutive segments of non-pollinated (X), tobacco-pollinated (▪), P. hybrida-pollinated (●), and wounded (♦) pistils at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after treatment. Segment one represents the stigma and segments two, three, and four represent upper, middle, and lower style (including the style-ovary transition zone), respectively. The accumulation levels are expressed in picograms per microgram total RNA and were obtained from calibrated RNA gel blots as described in “Materials and Methods.” In the pistil drawing over each graph, the position of the tip of the pollen tubes or needle is indicated by the respective symbol. Autoradiogram exposure times: 16 h.

In both tobacco and P. hybrida-pollinated pistils, similar ACC-oxidase transcript accumulation patterns were detected, but they were different from the ones observed for ACC-synthase transcripts (Figs. 5 and 6). In the first 6 HAP, ACC-oxidase mRNAs accumulated to high levels (82–203 pg μg−1 total RNA) in the stigma and throughout the style. However, at 12 HAP, the transcript levels in the stigma and the uppermost style part had declined but remained high in middle and lower style. At 24 HAP, ACC-oxidase transcripts had all increased to similar levels (Fig. 6). At 48 HAP, they were still present in the same pattern. However, in tobacco-pollinated styles, transcript levels had decreased, whereas in P. hybrida-pollinated styles they had increased. Wounding caused equal ACC-oxidase transcript levels in all parts of the stigma and style and remained high until 12 HAP, after which time point the levels decreased somewhat (Fig. 6).

Taken together, our observations show that pollination causes very different ACC-synthase and -oxidase accumulation patterns. ACC-oxidase expression is globally and strongly up-regulated by pollination. In contrast to ACC-oxidase, ACC-synthase expression levels are lower and their peaks progress with the front of the pollen tube tips in the style. In addition, these responses do not seem to be specific for congruous pollination because they can be completely or partially invoked by incongruous pollination or wounding, respectively.

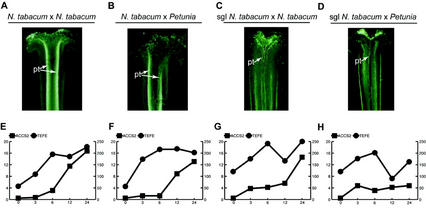

ACC-Synthase mRNA Accumulation Levels Depend on the Number of Ingrowing Pollen Tubes

To investigate whether, besides the position of the pollen tube tips, the number of pollen tubes also has an effect on ACC-synthase and -oxidase expression, we used pollinations on a stigmaless pistil in which only few pollen tubes can grow (Fig. 7; Goldman et al., 1994; Wolters-Arts et al., 1998). Wild-type styles pollinated with tobacco or P. hybrida pollen were penetrated by thick bundles of pollen tubes (Fig. 7, A and B). In contrast, stigmaless styles supplied with stigmatic exudate and pollinated with tobacco pollen were penetrated by a lesser number of pollen tubes (Fig. 7C) and P. hybrida-pollinated stigmaless styles were penetrated by only 10 to 20 pollen tubes (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Stylar ACC-synthase- and -oxidase mRNA accumulation levels related to number of ingrowing pollen tubes. A through D, Aniline blue-stained 100-μm vibratome sections of stigma and style of wild-type (A and B) and stigmaless (C and D) tobacco plants, pollinated with either tobacco (A and C) or P. hybrida (B and D) pollen. All pollinations of stigmaless tobacco plants were performed with added stigmatic exudate. Photographs were taken by epi-fluorescence microscopy. E through H, Line graphs of ACC-synthase and -oxidase mRNA accumulation at 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 HAP in styles of wild-type (E and F) and stigmaless tobacco plants (G and H), pollinated with either tobacco (E and G) or P. hybrida (F and H) pollen. The mRNA levels were measured as described in “Materials and Methods” from autoradiograms of calibrated northern blots containing 5 μg of total RNA per lane and exposed for 2 d (ACCS2 probe) or 1 d (TEFE probe). mRNA levels are expressed as picogram per microgram total RNA. pt, Pollen tubes.

Results in Figure 7 show that in all cases, ACC-synthase transcript levels did not rise strongly until 6 HAP. At 12 HAP, the levels increased in the wild-type styles (Fig. 7, E and F), and at 24 HAP, the level in stigmaless styles pollinated with tobacco pollen had also risen to approximately the same ACC-synthase RNA concentration (14.6 pg μg−1 total RNA; Fig. 7G). However, in stigmaless styles pollinated with P. hybrida pollen, the ACC-synthase levels always remained low at 4.8 pg μg−1 total RNA (Fig. 7H). In contrast to this, ACC-oxidase transcripts displayed the same accumulation curve in all styles except for a little “dip” at 12 HAP in stigmaless styles. Transcript accumulation started within 3 HAP and by 24 HAP the level in P. hybrida-pollinated stigmaless styles was only slightly lower (162 pg μg−1 total RNA; Fig. 7H) as compared with the ACC-oxidase transcript levels in the other styles (250, 200, and 225 pg μg−1 total RNA, respectively; Fig. 7, E–G). Taken together, these results show that pollen tube number mainly modulates ACC-synthase transcript accumulation levels and that once the number of penetrating pollen tubes has crossed a threshold of at least 10 to 20 pollen tubes, ACC-synthase transcripts accumulate to their highest levels.

DISCUSSION

We studied the movement of the pollination signal through the tobacco stigma and style by characterizing the relationship between pollination and tissue-specific accumulation of ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts. We have shown that pollination induces accumulation of these transcripts. However, ACC-oxidase transcripts accumulate to much higher levels—both before and after pollination—as compared with ACC-synthase. In addition, we found that ACC-oxidase transcripts accumulate in all cells of the transmitting tissue, whereas ACC-synthase transcripts accumulate in a subset of transmitting tract cells. More importantly however, our results show that although pollination-induced ACC-oxidase expression is high throughout the style, the ACC-synthase expression peak follows the front of the ingrowing pollen tubes. This response can also be mimicked by incongruous pollination and (partially) by wounding, indicating that wounding-like features of pollen tube invasion might be part of the stimuli evoking the postpollination response and that these stimuli are interpreted differently by the regulatory mechanisms of the ACCS2 and TEFE genes.

Pollination Induces ACC-Synthase- and -Oxidase Gene Expression

In tobacco, pollination induces ethylene release by the pistil (Hill et al., 1987; De Martinis et al., 2002) and we found that it also induces accumulation of ACC-synthase and -oxidase mRNAs (Figs. 1 and 3–7). Similar results have been found for a variety of species (Tang and Woodson, 1996; Clark et al., 1997; Jones and Woodson, 1997; O'Neill, 1997; Bui and O'Neill, 1998) and, together, they suggest that at least part of the rise in ethylene production is because of the activation of genes coding for the enzymes of ethylene biosynthesis (O'Neill, 1997).

The ACCS2 and TEFE genes are part of a small gene family. It has been shown for ACC-synthase and -oxidase gene families from other species that each member has a different tissue- and temporal-specific expression pattern (Tang et al., 1994; Bui and O'Neill, 1998; Jones and Woodson, 1999; Llop-Tous et al., 2000). Because both ACCS2 and TEFE share high homologies to previously identified ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts from tobacco, we cannot exclude that ACCS2 and TEFE probes may also detect transcripts from other gene family members. Despite this apparent lack of specificity, we found that the ACCS2 and TEFE probes have overlapping floral tissue-specific hybridization patterns and they do not hybridize to RNA from vegetative organs (Fig. 1). However, the transcripts that can be detected by the ACCS2 and TEFE probe are not regulated coordinately during pistil development because ACC-oxidase transcripts are already present at stage 6 (Fig. 2). This difference in temporal expression seems to be maintained after pollination because in mature pistils ACC-synthase transcripts reach a discrete level at 24 HAP and TEFE at 3 HAP. In addition, when stage 6 pistils are pollinated, ACC-oxidase transcripts appear at 3 HAP, whereas ACC-synthase expression is only detectable at 24 HAP (Fig. 3). Together, this indicates that the regulatory mechanism of the ACCS2 gene (and possibly other ACC-synthase genes) cannot be triggered by pollination until it is activated by other developmental cues. The fact that development sets up specific pollination-related mechanisms is also demonstrated by the acquisition of incongruity barriers in the tobacco pistil after stage 6 (Kuboyama et al., 1994; Sanchez and Mariani, 2002) and the inability of immature P. hybrida pistils to sustain ethylene production (Tang and Woodson, 1996).

After landing and germination on the stigma, pollen tubes will grow between the cells of the secretory and transition zone and subsequently through the extracellular matrix of the transmitting tract (Herrero and Dickinson, 1979). In pollinated styles, ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts both accumulate in cells of the transmitting tissue. However, ACC-synthase transcripts accumulate in discrete patches of transmitting tract cells and ACC-oxidase transcripts accumulate in all transmitting tract cells (Fig. 4). Although it is not clear what causes these different accumulation patterns, one possible explanation could be that within this apparently homogenous tissue, at least two cell types exist. However, we did not observe any differences in cell morphology by toluidine blue staining and bright-field microscopy (data not shown). Therefore, an alternative explanation could be that the transmitting tract cells only express ACC-synthase after receiving a signal that is spread unequally over the style.

Upon pollination, ACC-oxidase transcripts, but no ACC-synthase transcripts, accumulate in the cortex cells. ACC-oxidase transcript accumulation in the cortex is probably caused by elevated ethylene levels in the style, as it was shown in P. hybrida by Tang et al. (1994). The fact that cells and tissues in the style have different ACC-synthase and -oxidase mRNA accumulation responses after pollination indicates that these responses are controlled by different regulatory mechanisms.

Ethylene Does Not Signal Incongruous Pollinations

In situ hybridization does not allow quantitative analysis of gene expression. Therefore, we also devised a method to detect a low level of expression at a particular time in a particular position of a pollinated or non-pollinated pistil. Using this method, we found that pollination sets up typical ACC-synthase and -oxidase expression patterns along the style that change during pollen tube growth (Figs. 5 and 6). However, until 24 HAP, we found no differences between either the ACC-synthase or -oxidase transcript accumulation patterns induced by tobacco and P. hybrida pollinations. This similarity of responses was also found in mRNA poly(A+) tail shortening and in cell deterioration (Wang et al., 1996). Together, these data suggest that ethylene does not play a role as a signal in incongruous pollinations, but rather, it is a product of pollination. Similar conclusions were obtained by De Martinis et al. (2002) and Sanchez and Mariani (2002), who showed that in tobacco styles, pollinated with either Nicotiana repanda or Nicotiana maritima pollen, ethylene production and ACC oxidase expression stopped after pollen tube growth had arrested.

At 48 HAP, transcript levels remained high for ACC-synthase in P. hybrida-pollinated styles, whereas transcript levels in tobacco-pollinated styles showed a sharp decrease (Fig. 5). This difference in transcript levels is probably the reason for the delayed ethylene evolution peak observed in these crosses (De Martinis et al., 2002; data not shown). Although we do not know what causes this different response, one possible explanation might be that this increased expression is caused by delayed pollen tube growth of P. hybrida and pausing at the transition zone between style and ovary.

Progression of Pollen Tubes through the Style Coincides with Localized Up-Regulation of ACC-Synthase Transcript Levels

Pollination-induced ethylene evolution is characterized by two peaks: one at 3 HAP mainly from the stigma and one at 36 HAP from flower organs distal to the stigma (Hill et al., 1987; De Martinis et al., 2002). Until now, it was not known whether pollination induces ethylene, ACC-synthase, and -oxidase production in the whole style at once or gradually as the pollen tubes grow downwards. Data from Figure 6 show that after pollination or wounding, high ACC-oxidase levels appear immediately and persist throughout the style. In contrast to ACC-oxidase, during the time frame the pollen tubes grow through the style, we found that the ACC-synthase transcript accumulation patterns can be distinguished in two phases: (a) Within 3 HAP, transcripts accumulate throughout the style but mainly in the stigma; and (b) between 3 and 24 HAP, the ACC-synthase transcript peak moves downward in the style with the front of growing pollen tubes (Fig. 5).

The current model on pollination-induced interorgan signaling (O'Neill, 1997; Bui and O'Neill, 1998) suggests that after landing, the pollen transmits one or more primary pollination signal(s) that are translocated quickly (i.e. within 4 h; Gilissen and Hoekstra, 1984) to the distal flower organs. It has been shown that pollen-borne ACC most likely is not the translocated factor (Singh et al., 1992; Woltering et al., 1997), but rather is converted immediately to ethylene by the highly abundant ACC-oxidases in the stigma (Fig. 6; Hoekstra and Weges, 1986; Tang et al., 1994), thus producing the first ethylene peak. At present, the exact identity of the primary pollination factor is not yet known (Porat et al., 1998), although auxin has been suggested and stigma- and ovary-specific auxin-regulated ACC-synthase genes have been identified (Bui and O'Neill, 1998). Whatever these factors will turn out to be, it seems reasonable to suggest that, at phase one, the ACC-synthase transcript accumulation pattern and, therefore, probably also the ethylene production pattern along the style (Fig. 5) illustrate the action of the translocating primary pollination signal. In addition, it is clear from our observations that, at phase two, the second peak of ethylene evolution by the style (De Martinis et al., 2002; K. Weterings unpublished data) is produced by an increasing ethylene production peak that moves downwards with the front of the pollen tube tips as illustrated by the ACC-synthase transcript accumulation wave (Fig. 5).

The Dynamic ACC-Synthase Expression Patterns Can Be Mimicked by Wounding

One unsolved question is whether ethylene production is induced by the growing pollen tubes or by the wounding in the pistil caused during growth. Wounding the pistil has been shown to generate responses in the flower similar to pollination responses (Gilissen, 1977; Gilissen and Hoekstra, 1984; Hoekstra and Weges, 1986). Woltering et al. (1997) have suggested that these two responses might be mediated by different signals. We found that, at 3 h after wounding, from the position of the needle tip downward an ACC-synthase mRNA accumulation pattern similar to the pollination-induced phase one pattern is set up. This finding is in agreement with the early ethylene peak that has been observed for wounded pistils (Hill et al., 1987; Woltering et al., 1997). Furthermore, until 12 h after treatment, phase two of the ACC-synthase transcript accumulation pattern evoked by pollination can also be induced by wounding. After 12 h, however, ACC-synthase expression levels go down and expression patterns no longer resemble those that are induced by pollination (Fig. 5). The high-ethylene evolution levels that are sustained for several days after pistil wounding (Hoekstra and Weges, 1986) seem to be conflicting with the low-ACC synthase levels in the pistil, but can probably be explained by higher ethylene production associated with accelerated corolla wilting (Gilissen and Hoekstra, 1984; Hoekstra and Weges, 1986; Woltering et al., 1997).

What causes the difference between pollination- and wounding-induced ACC-synthase transcript accumulation patterns at 24 and 48 h after treatment? One explanation might be that the single wounding event caused by inserting a needle at a high position in the style is insufficient to sustain an ACC-synthase expression pattern equal to that caused by the continuous and progressive wounding inflicted by pollen tube growth. This notion is in agreement with the finding that fewer pollen tubes growing in the style cause lesser damage than average pollination, and are unable to generate an ACC-synthase and ethylene production response (Fig. 7; Stead, 1985; Hill et al., 1987). In addition, other reports have shown a clear relationship between arrest of pollen tube growth in incongruous and incompatible pollinations and lower ethylene production and lower expression of ACC-oxidase (Singh et al., 1992; De Martinis et al., 2002; Sanchez and Mariani, 2002). Therefore, it is tempting to suggest that, because the tip of the needle and the tips of the pollen tubes elicit the same ACC-synthase expression pattern (Fig. 5), it is the wounding and not pollen tube growth that causes this pattern. In carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus), however, Larsen et al. (1995) have shown that incompatible pollen tubes that are actively growing through the style do not elicit ethylene production, suggesting that, at least in this plant, additional signals besides wounding are probably needed to generate the full postpollination response.

Taken together, we have shown that ACC-synthase and -oxidase transcripts both are accumulated upon penetration of the style by the pollen tubes. Study of mRNA accumulation patterns in the style resulting from congruous or incongruous pollination has shown that each type of pollination causes its own characteristic, dynamic accumulation motif. Evidently, these patterns are the result of specific communications along the style, between the pollen tubes and the style, and between the ovary and the style. One or more pollen-derived signals and wound-induced signals clearly play an important role in this communication. However, the exact natures of the signal(s) and of the signal(s) regulating ACCS2 and TEFE during the progamic phase, whether they are derived from the pollen or the style, remain to be established.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material, Flower Stages, and Treatments

Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) cv “Petit Havana” SR1, stigmaless tobacco plants (Goldman et al., 1994), and Petunia hybrida W115 were maintained in a growth chamber at 15 h of light (20°C, 65% relative humidity) and 9 h of dark (18°C, 65% relative humidity).

The following morphological markers were used for flower staging (Koltunow et al., 1990): stage 1, bud length (b.l.) = 8 mm and calyx is closed and onion-shaped; stage 2, b.l. = 11 mm and calyx slightly opened; stage 3, b.l. = 14 mm and corolla starts to emerge from the calyx; stage 4, b.l. = 16 mm and sepals completely separated at calyx tip; stage 5, b.l. = 20 mm and the bulge of the corolla tube is just inside the calyx; stage 6, b.l. = 22 mm and corolla tube bulge is outside at the tip of the calyx; stage 7, b.l. = 28 mm and corolla tube and bulge have emerged from the calyx; stage 8, b.l. = 39 mm and corolla has elongated and petals are green; stage 9, b.l. = 43 mm, corolla tube bulge has enlarged, and petal tips are slightly pink; stage 10, b.l. = 45 mm, corolla limb is beginning to open, and petal tips are pink; stage 11, b.l. = 46 mm, corolla limb is halfway open, and stigma and anthers are visible; and stage 12, b.l. = 46 mm, flower is open, the anthers have dehisced, and the corolla limb is fully expanded and deep pink.

For pollination studies, flowers at stage 11 were emasculated 16 h before treatment. Pollination was carried out by brushing mature pollen from a dehisced anther onto the stigma. In stigmaless tobacco flowers, 2 to 4 μL of exudate from a mature, emasculated P. hybrida flower was added before pollination. For wounding, a 25-gauge hypodermic needle was pushed once or twice through the stigma into the upper part of the style.

Construction of Pollinated Stigma-Style cDNA Library

cDNA was prepared from poly(A+) RNA isolated from 12-HAP stigma-styles, cloned unidirectionally in EcoRI- and XhoI-digested arms of phage λ ZAPII, and packaged using Gigapack II Gold packaging extract according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Isolation of TEFE and ACCS2

TEFE was isolated by differentially screening 300,000 plaque-forming units of the tobacco-pollinated stigma-style cDNA library with a cDNA probe prepared from 12-HAP stigma-style poly(A+) RNA as positive probe and a cDNA probe from pooled non-pollinated stigma-style, mature pollen, and seedling poly(A+) RNA as negative probe.

ACCS2 was isolated by screening the tobacco-pollinated stigma-style cDNA library with a cDNA clone coding for the ACC-synthase conserved region. This partial cDNA clone was obtained by reverse transcriptase-PCR using pollinated stigma-style RNA as template and degenerate primers directed against the ACC-synthase conserved region (RP-SYN2, 5′-CCCAKCRGCYTCAATYTGYAC-3′; and RP-SYN3, 5′-CCRAYTCKRAADCCWGGBARSCCCAT-3′; Zarembinski and Theologis, 1993). GenBank accession numbers for ACCS2 and TEFE are X98492 and X98493, respectively.

RNA Isolation and Analysis

RNA was isolated as described by Eldik et al. (1995). Tissue was ground in liquid N2, with extraction buffer (0.1 m Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 0.1 m NaCl, 0.05 m EDTA, 1% [w/v] SDS, 1% [w/v] tri-iso-naphthalene-sulfonic acid sodium salt [Eastman-Kodak, Rochester, NY], and 0.05 m β-mercapto-ethanol) and Tris-Cl [pH 7.5]- buffered phenol, mixed in a ratio of 1:1 (v/v). After extraction with phenol:Sevag (1:1 [v/v]), mRNA was recovered from the homogenate by precipitation with ethanol followed by precipitation with LiCl. Poly(A+) RNA was isolated using the PolyATtract para-magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's protocol (Promega, Madison, WI).

RNA was separated on a 1.1% (w/v) agarose and 2% (w/v) formaldehyde gel, run in 1× MOPS buffer (Sambrook et al., 1989). For calibration, on each gel a dilution series of in vitro-produced ACCS2 and/or TEFE transcripts was loaded (Cornelissen and Vandewiele, 1989). After equal loading was confirmed by comparison of the ribosomal RNA bands, RNA was transferred to Hybond N (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) and all blots were hybridized and washed under stringent conditions (65°C; 0.1× SSC).

ACCS2 and TEFE transcripts were quantified by scanning the autoradiograms containing the hybridization signals from RNA samples and calibration series with the Ultroscan laser scanner (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala), processing the scan data with Gelscan XL software (Pharmacia), and plotting it on the ACCS2- or TEFE-specific calibration curve (Cornelissen and Vandewiele, 1989).

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization studies were carried out as described by Cox and Goldberg (1988) and Yadegari et al. (1994) with minor modifications. In brief, 1-cm style sections were fixed (0.5% [w/v] glutaraldehyde, 4% [w/v] formaldehyde, in 0.01 m KPO4 buffer [pH 6.8] containing 0.1% [v/v] Triton X-100), dehydrated, cleared, and embedded in paraffin. Ten-micrometer sections were hybridized to [33P]UTP-labeled sense or antisense RNA probes at a specific activity of 4 to 5 × 108 dpm μg−1. After hybridization and emulsion development, sections were stained with toluidine blue. Slides were viewed under dark-field illumination with a compound microscope (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) and images were captured digitally using a CCD camera (CoolSnap, Silver Spring, MD). The images were assembled in Adobe Photoshop 5.0 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) and adjusted for optimum silver grain resolution.

Aniline Blue Staining

Fresh 100-μm vibratome sections of stigma and style were stained with aniline blue according to Kho and Bera (1968), and viewed by epi-fluorescence.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the “BRIDGE” program (European Community fellowship to M.P.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.007831.

LITERATURE CITED

- Bui AQ, O'Neill SD. Three 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase genes regulated by primary and secondary pollination signals in orchid flowers. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:419–428. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.1.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DG, Richards C, Hilioti Z, Lind IS, Brown K. Effect of pollination on accumulation of ACC-synthase and ACC-oxidase transcripts, ethylene production and flower petal abscission in geranium (Pelargonium × hortorum L.H. Bailey) Plant Mol Biol. 1997;34:855–865. doi: 10.1023/a:1005877809905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen M, Vandewiele M. Both RNA level and translation efficiency are reduced by anti-sense RNA in transgenic tobacco. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:833–843. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox KH, Goldberg RB. Analysis of plant gene expression. In: Shaw CH, editor. Plant Molecular Biology: A Practical Approach. Oxford: IRL Press; 1988. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- De Martinis D, Cotti G, te Lintel Hekkert S, Harren FJM, Mariani C. Ethylene response to pollen-tube growth in the Nicotiana tabacum flower. Planta. 2002;214:806–812. doi: 10.1007/s00425-001-0684-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldik GJ, Vriezen WH, Wingens M, Ruiter RK, Vanherpen MMA, Schrauwen JAM, Wullems GJ. A pistil-specific gene of Solanum tuberosum is predominantly expressed in the stylar cortex. Sex Plant Reprod. 1995;8:173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Gilissen LJW. Style-controlled wilting of the flower. Planta. 1977;133:275–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00380689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilissen LJW, Hoekstra FA. Pollination-induced corolla wilting in Petunia hybrida: rapid transfer through the style of a wilting-inducing substance. Plant Physiol. 1984;75:496–498. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.2.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MHS, Goldberg RB, Mariani C. Female sterile tobacco plants are produced by stigma-specific cell ablation. EMBO J. 1994;13:2976–2984. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto R, Aida R, Shibata M, Ichimura K. Role of ethylene on flower senescence of Torenia. J Jpn Soc Hortic Sci. 1999;68:263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Herrero M, Dickinson HG. Pollen-pistil incompatibility in Petunia hybrida: changes in the pistil following compatible and incompatible intraspecific crosses. J Cell Sci. 1979;36:1–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.36.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SE, Stead AD, Nichols R. Pollination-induced ethylene and production of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid by pollen of Nicotiana tabacum cv White Burley. J Plant Growth Regul. 1987;6:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra FA, Weges R. Lack of control by early pistillate ethylene of the accelerated wilting of Petunia hybrida flowers. Plant Physiol. 1986;80:403–408. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ML, Woodson WR. Pollination-induced ethylene in carnation: role of stylar ethylene in corolla senescence. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:205–212. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ML, Woodson WR. Differential expression of three members of the 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase gene family in carnation. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:755–764. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.2.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kho YO, Bera J. Observing pollen tubes by means of fluorescence. Euphytica. 1968;17:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Knoester M, Bol JF, van Loon LC, Linthorst HJM. Virus-induced gene expression for enzymes of ethylene biosynthesis in hypersensitively reacting tobacco. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1995;8:177–180. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltunow AM, Truettner J, Cox KH, Wallroth M, Goldberg RB. Different temporal and spatial gene expression patterns occur during anther development. Plant Cell. 1990;2:1201–1224. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.12.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboyama T, Chung CS, Takeda G. The diversity of interspecific pollen-pistil incongruity in Nicotiana. Sex Plant Reprod. 1994;7:250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Lantin S, O'Brien M, Matton DP. Pollination, wounding and jasmonate treatments induce the expression of a developmentally regulated pistil dioxygenase at a distance, in the ovary, in the wild potato Solanum chacoense Bitt. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;41:371–386. doi: 10.1023/a:1006375522626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen PB, Ashworth EN, Jones ML, Woodson WR. Pollination-induced ethylene in carnation. Role of pollen tube growth and sexual compatibility. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1405–1412. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom JT, Lei CH, Jones ML, Woodson WR. Accumulation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) in Petunia pollen is associated with expression of a pollen-specific ACC synthase late in development. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1999;124:145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Liu JZ, Li N, Yang SF, Kung SD. Full length nucleotide sequence of the tobacco cultivar SR1 encoding 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1534. [Google Scholar]

- Llop-Tous I, Barry CS, Grierson D. Regulation of ethylene biosynthesis in response to pollination in tomato flowers. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:971–978. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.3.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill SD. Pollination regulation of flower development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1997;48:547–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porat R, Nadeau JA, Kirby JA, Sutter EG, O'Neill SD. Characterization of the primary pollen signal in the postpollination syndrome of Phalaenopsis flowers. Plant Growth Regul. 1998;24:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez AM, Mariani C. Expression of the ACC-synthase and ACC-oxidase coding genes after self- and incongruous pollination of tobacco pistils. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;48:351–359. doi: 10.1023/a:1014087914652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Evensen KB, Kao TH. Ethylene synthesis and floral senescence following compatible and incompatible pollinations in Petunia inflata. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:38–45. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead AD. The relationship between pollination, ethylene production and flower senescence. In: Tucker GA, Roberts JA, editors. Ethylene and Plant Development. London: Butterworths; 1985. pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Woodson WR. Temporal and spatial expression of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase mRNA following pollination of immature and mature Petunia flowers. Plant Physiol. 1996;112:503–511. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.2.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang XY, Gomes AMTR, Bhatia A, Woodson WR. Pistil-specific and ethylene-regulated expression of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase genes in Petunia flowers. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1227–1239. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wu HM, Cheung AY. Pollination induces mRNA poly(A) tail-shortening and cell deterioration in flower transmitting tissue. Plant J. 1996;9:715–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.9050715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltering EJ, de Vrije T, Harren F, Hoekstra FA. Pollination and stigma wounding: same response, different signal? J Exp Bot. 1997;48:1027–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Woltering EJ, ten Have A, Larsen PB, Woodson WR. Ethylene biosynthetic genes and inter-organ signaling during flower senescence. In: Scott RJ, Stead AD, editors. Molecular and Cellular Aspects of Plant Reproduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1994. pp. 285–307. [Google Scholar]

- Wolters-Arts M, Derksen J, Kooijman JW, Mariani C. Stigma development in Nicotiana tabacum. Cell death in transgenic plants as a marker to follow cell fate at high resolution. Sex Plant Reprod. 1996;9:243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Wolters-Arts M, Lush WM, Mariani C. Lipids are required for directional pollen-tube growth. Nature. 1998;392:818–821. doi: 10.1038/33929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadegari R, De Paiva G, Laux T, Koltunow AM, Apuya N, Zimmerman JL, Fischer RL, Harada JJ, Goldberg RB. Cell differentiation and morphogenesis are uncoupled in Arabidopsis raspberry embryos. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1713–1729. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SF, Hoffman NE. Ethylene biosynthesis and its regulation in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1984;35:155–189. [Google Scholar]

- Zarembinski TI, Theologis A. Anaerobiosis and plant growth hormones induce two genes encoding 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Mol Biol Cell. 1993;4:363–373. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.4.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XS, O'Neill SD. Ovary and gametophyte development are coordinately regulated by auxin and ethylene following pollination. Plant Cell. 1993;5:403–418. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.4.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]