Abstract

GSK3 is a highly conserved kinase that negatively regulates many cellular processes by phosphorylating a variety of protein substrates. BIN2 is a GSK3-like kinase in Arabidopsis that functions as a negative regulator of brassinosteroid (BR) signaling. It was proposed that BR signals, perceived by a membrane BR receptor complex that contains the leucine (Leu)-rich repeat receptor-like kinase BRI1, inactivate BIN2 to relieve its inhibitory effect on unknown downstream BR-signaling components. Using a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) two-hybrid approach, we discovered a potential BIN2 substrate that is identical to a recently identified BR-signaling protein, BES1. BES1 and its closest homolog, BZR1, which was also uncovered as a potential BR-signaling protein, display specific interactions with BIN2 in yeast. Both BES1 and BZR1 contain many copies of a conserved GSK3 phosphorylation site and can be phosphorylated by BIN2 in vitro via a novel GSK3 phosphorylation mechanism that is independent of a priming phosphorylation or a scaffold protein. Five independent bes1 alleles containing the same proline-233-Leu mutation were identified as semidominant suppressors of two different bri1 mutations. Over-expression of the wild-type BZR1 gene partially complemented bin2/+ mutants and resulted in a BRI1 overexpression phenotype in a BIN2+ background, whereas overexpression of a mutated BZR1 gene containing the corresponding proline-234-Leu mutation rescued a weak bri1 mutation and led to a bes1-like phenotype. Confocal microscopic analysis indicated that both BES1 and BZR1 proteins were mainly localized in the nucleus. We propose that BES1/BZR1 are two nuclear components of BR signaling that are negatively regulated by BIN2 through a phosphorylation-initiated process.

BRs are a special class of plant polyhydroxysteroids that have wide distribution throughout the plant kingdom and play many important roles throughout plant development that include seed germination, stem elongation, pollen tube growth, vascular differentiation, skotomorphogenesis, and stress resistance (Clouse and Sasse, 1998; Steber and McCourt, 2001). It was well documented that gene regulation is critical for many BR-elicited physiological responses (Clouse and Feldmann, 1999), however, the signaling mechanism from BR perception to gene regulation remains largely unknown. Extensive genetic screens for BR-insensitive-signaling mutants in Arabidopsis have so far identified only two genes, BRI1 and BIN2 (Clouse et al., 1996; Kauschmann et al., 1996; Li and Chory, 1997; Noguchi et al., 1999; Li et al., 2001; Li and Nam, 2002).

BRI1 encodes a Leu-rich repeat receptor-like kinase that is composed of an extracellular domain, a single-pass transmembrane segment, and an intracellular kinase domain (Li and Chory, 1997). BRI1 is a plasma membrane-localized protein and can function as a Ser/Thr kinase when expressed in Escherichia coli or animal cell culture (Friedrichsen et al., 2000; Oh et al., 2000). The extracellular domain of BRI1 can confer BR responsiveness to the kinase domain of Xa21, a rice (Oryza sativa) Leu-rich repeat-receptor-like kinase involved in plant disease resistance (He et al., 2000). It was shown that transgenic plants overexpressing the BRI1 gene displayed an enhanced BR sensitivity and contained a higher BR-binding activity that could be co-immunoprecipitated with the BRI1 protein (Wang et al., 2001). In addition, BR treatment of Arabidopsis seedling enhanced BRI1 phosphorylation (Wang et al., 2001). It was concluded that BRI1 is a critical component of a BR receptor complex at the cell surface.

BIN2, which is identical to the UCU1 gene implicated in leaf development (Pérez-Pérez et al., 2002), encodes an intracellular Ser/Thr kinase that displays significant sequence identity to the mammalian GSK3 and fruitfly (Drosophila melanogaster) SHAGGY kinases (Li and Nam, 2002). A hypermorphic mutation within its coding sequence or its overexpression led to a phenotype similar to BR-deficient or bri1 mutants. In contrast, a forced reduction of BIN2 gene expression via cosuppression partially rescued a weak bri1 mutation, suggesting that BIN2 functions as a negative regulator in the plant steroid signaling (Li and Nam, 2002).

Originally identified as a kinase that phosphorylates and inactivates glycogen synthase (Embi et al., 1980), GSK3 is a highly conserved kinase that is implicated in many fundamental biological processes that include metabolism, gene regulation, cell fate determination, tissue patterning, and programmed cell death (Frame and Cohen, 2001). In resting cells, GSK3 is a constitutively active kinase that phosphorylates a variety of protein substrates including cytoskeleton proteins and transcriptional factors, but becomes inactive in response to a variety of stimuli. The majority of known GSK3 substrates contains repeats of a short consensus sequence, S/TxxxS/T (S/T corresponds to Ser or Thr and x denotes any other residues; Woodgett, 2001). It is well known that GSK3 cannot directly bind its substrates, and at least two different mechanisms have been described for GSK3 to bind and phosphorylate its diverse substrates (Cohen and Frame, 2001). One requires a priming phosphorylation in which a distinct protein kinase phosphorylates the C-terminal S/T residue of the S/TxxxS/T motif, thus creating a GSK3-binding site on the substrates to allow the N-terminal S/T residue be phosphorylated by the GSK3 kinase, whereas the other involves a scaffold protein that binds both GSK3 and its substrates to facilitate phosphorylation of the substrates by the GSK3 kinase.

It was hypothesized that, in the absence of BR signals, BIN2 is a constitutively active kinase that would phosphorylate several positive BR-signaling proteins, rendering them inactive to mediate BR signaling (Li and Nam, 2002). To fully understand how BIN2 functions to control BR signaling, it is essential to identify its phosphorylation targets. Using BIN2 as a bait, we conducted a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) two-hybrid screen and identified a novel Arabidopsis protein, which contains many copies of the consensus S/T/xxxS/T GSK3 phosphorylation motif, as a potential BIN2 substrate. Interestingly, this protein, which was originally named BIN2 SUBSTRATE 1 (BIS1), and its closet homolog (named BIN2 SUBSTRATE 2 [BIS2]) are identical to two recently identified BR-signaling proteins, BES1 and BZR1, respectively (Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002). In this report, we present both biochemical and genetic data to show that both BES1 and BZR1 are putative substrates of BIN2 and that they function positively to mediate BR signaling in Arabidopsis.

RESULTS

BES1 and BZR1 Interact Specifically with BIN2 in Yeast Cells

To understand how the cytoplasmic BIN2 kinase regulates BR signaling, we sought to identify potential BIN2 substrates using the yeast two-hybrid approach. A full-length BIN2 protein containing the hypermorphic bin2-1 mutation was used as bait to screen an Arabidopsis two-hybrid cDNA library (Kim et al., 1997). Among the BIN2-interacting clones were nine overlapping cDNAs encoding a novel Arabidopsis protein of 335 amino acids (accession no. AAF79422), which was named BIS1. The longest BIS1 clone starts at the 40th codon of the full-length BIS1 gene, whereas the shortest BIS1 clone encodes the C-terminal 52 amino acids. Yeast two-hybrid analysis indicated that BIS1 interacted with the wild-type and bin2-1-mutated BIN2 proteins but failed to interact with the BRI1 cytoplasmic kinase (BRI1CK), the Gal4 DNA-binding domain, or the N-terminal portion of an Arabidopsis NADPH oxidase (91N; Keller et al., 1998), a nonrelevant bait (Fig. 1A), suggesting that BIS1 specifically interacted with BIN2. Consistent with a recent result indicating that kinase activity is not required for a GSK3/substrate interaction in animals (Fraser et al., 2002), the kinase-dead BIN2 protein containing a Lys-69-Arg mutation was still able to interact with BIS1 (Fig. 1A).

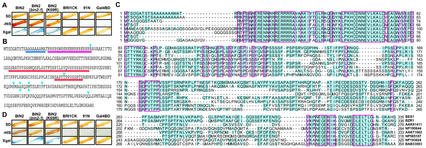

Figure 1.

Identification of BES1 and BZR1 as potential BIN2 substrates. A, BES1 displays a specific interaction with BIN2 measured by growth on medium lacking His (second strip) and blue color on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside-containing medium (third strip). B, The hypothetical product of the BES1 gene. The Ala stretch, the bipartite nuclear localization sequence, and putative GSK3 phosphorylation sites are denoted by blue, pink, and red underlines, respectively. The arrows indicate the N-terminal positions where partial BES1 proteins of the original yeast two-hybrid clones are fused with the GAL4 DNA activation domain. C, Alignment of BES1 protein and its homologs. Aligned with BES1 are BZR1 (AAL57684), four other Arabidopsis hypothetical proteins (NP_190644, NP_193624, AAK91411, and NP_565187), a tomato mature anther-specific protein (AAK71662), and an unknown rice protein (BAB33003). The multiple sequence alignment was conducted using the Lasergene sequence analysis software package (DNAStar, Inc., Madison, WI). Absolutely conserved amino acids are indicated by the pink box, whereas homologous amino acids are shaded with blue color. D, BIN2 can also interact with BZR1 in the yeast two-hybrid assay.

In addition to a stretch of Ala residues and a bipartite nuclear localization signal at its N terminus, BIS1 contains in its middle portion two S/T-rich segments with nine and three copies of a S/TxxxS/T motif (Fig. 1B) that is known to be phosphorylated by many animal GSK3 kinases (Cohen and Frame, 2001). Database searches revealed that BIS1 displays significant sequence identities with five hypothetical Arabidopsis proteins (AAL57684, NP_190644, NP_193624, AAK91411, and NP_565187), a tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) mature anther-specific protein (AAK71662), and an unknown rice protein (BAB33003; Fig. 1C). Because BIS1 and AAL57684 are almost identical in size and share 89% sequence identity, we named the latter protein BIS2 and tested whether it could also interact with BIN2 using the yeast two-hybrid assay. As indicated in Figure 1D, BIS2 did interact with the wild-type and two mutated BIN2 proteins but failed to interact with BRI1CK or the N-terminal part of the Arabidopsis NADPH oxidase. Interestingly, BIS1 and BIS2 are identical to BES1 and BZR1, respectively, the two novel BR-signaling proteins identified through independent genetic approaches (Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002). We therefore renamed the two potential BIN2 substrates as BES1 and BZR1.

Both BES1 and BZR1 Can Be Phosphorylated by BIN2 in Vitro

Because BES1 and BZR1 contain many copies of the consensus S/TxxxS/T GSK3 phosphorylation motif, we wanted to know whether they could be phosphorylated by BIN2 in vitro. We expressed the wild-type BIN2, BES1, and BZR1 as glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins in E. coli. In addition, we also expressed GST, a GST-BRI1CK fusion protein, and two mutated GST-BIN2 proteins containing the bin2-1 and Lys-69-Arg mutations, respectively. After purification, GST, GST-BES1, or GST-BZR1 was incubated with BRI1CK or one of the different forms of BIN2 proteins and assayed for protein phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 2, A and B, both BES1 and BZR1 were phosphorylated when incubated with the wild-type BIN2 kinase, whereas little phosphorylation was detected on either protein when incubated with the kinase-dead BIN2 or the active GST-BRI1CK fusion protein. As expected, the bin2-1-mutated BIN2 protein showed a higher kinase activity toward BES1 or BZR1 than the wild-type BIN2, whereas no phosphorylation by the wild-type GST-BIN2 was observed on the GST itself (data not shown). Thus, we concluded that BIN2 could phosphorylate both BES1 and BZR1 proteins in vitro.

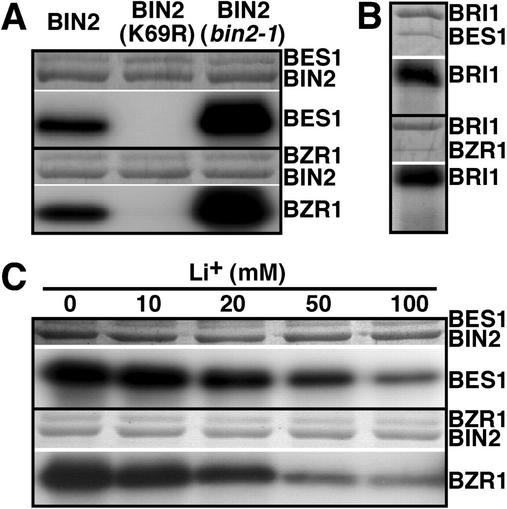

Figure 2.

Phosphorylation of BES1/BZR1 by BIN2 in vitro. A, BIN2 can phosphorylate both BES1 and BZR1 in vitro. GST-BES1 (top) or GST-BZR1 (bottom) fusion proteins were mixed with the wild-type BIN2 (lane 1), the Lys-69-Arg-mutated GST-BIN2 (lane 2), or the bin2-1-mutated GST-BIN2 (lane 3) to measure protein phosphorylation activity as described in “Materials and Methods.” B, GST-BRI1CK was unable to phosphorylate BES1 or BZR1 protein. C, The phosphorylation of BES1 or BZR1 by BIN2 can be inhibited by lithium. For A through C, the amount of proteins used in the kinase assays is indicated by Coomassie Blue staining in the top strip above the white dividing line, whereas the level of proteins phosphorylation is shown by autoradiography in the bottom strip.

It is well known that lithium ions can specifically inhibit GSK3 kinase activity (Klein and Melton, 1996; Stambolic et al., 1996) by competing with Mg2+ that is critical for the GSK3 kinase activity (Ryves and Harwood, 2001). If BES1 and BZR1 were substrates of BIN2, their phosphorylation by BIN2 in vitro would be inhibited by lithium treatment. We conducted similar in vitro phosphorylation assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of lithium. As indicated in Figure 3C, the phosphorylation of both BES1 and BZR1 were inhibited by lithium, supporting our conclusion that the observed phosphorylation of BES1 or BZR1 was catalyzed by the BIN2 GSK3 kinase.

Figure 3.

BIN2 phosphorylation of BES1 and BZR1 via a novel mechanism. A, Phosphorylation of BES1 and BZR1 by BIN2 does not require priming phosphorylation. CIP-treated GST-BES1 or GST-BZR1 was incubated with GST-BIN2 or with a mutated GST-BIN2 fusion protein containing Arg-80-Ala mutation, and assayed for protein phosphorylation as described in the “Materials and Methods.” B, Both GST-BES1 and GST-BZR1 proteins can be phosphorylated by an MBP-BIN2 fusion kinase. C, FRATide has no inhibitory effect on the BIN2 phosphorylation of either BES1 or BZR1. For all panels, the amount of protein used for the kinase assays are indicated in the top strip, whereas the levels of protein phosphorylation are shown in the bottom strip.

BIN2 Phosphorylates BES1 and BZR1 via a Novel Mechanism

It is well established that efficient phosphorylation of a protein substrate by a GSK3 kinase occurs only after the substrate is prime-phosphorylated at the C-terminal S/T residue of the S/TxxxS/T motif by a different protein kinase or when the substrate and GSK3 are brought together by a scaffold protein (Cohen and Frame, 2001; Woodgett, 2001). It is quite possible that both BES1 and BZR1 proteins were prime-phosphorylated by an E. coli kinase during their synthesis to create a GSK3 recognition site on either protein. To investigate such a possibility, we treated both GST-BES1 and GST-BZR1 fusion proteins with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIP) and used the resulting dephosphorylated GST-fusion proteins for the in vitro kinase assay. As indicated in Figure 3A, BIN2 was still able to phosphorylate the CIP-treated substrates to the same levels as the non-treated substrates, suggesting that the phosphorylation of BES1 or BZR1 by BIN2 does not require a priming phosphorylation event. To further confirm this result, we generated a mutant GST-BIN2 fusion protein by mutating Arg-80 to Ala, which corresponds to Arg-96 of the human GSK3β kinase that is known to be essential for binding a primed substrate (Frame et al., 2001). As shown in Figure 3A, the mutated BIN2 kinase was still capable of phosphorylating the two putative substrates as well as the wild-type BIN2 kinase did.

It is also possible that the observed transphosphorylation of the two GST-tagged putative BIN2 substrates by the GST fused BIN2 kinase was mediated by GST homodimerization, a functional equivalent to a scaffold protein. To eliminate this possibility, we used a different BIN2 fusion protein tagged with a maltose-binding protein (MBP) for the in vitro kinase assay. As shown in Figure 3B, the MBP-BIN2 fusion kinase could also efficiently phosphorylate BES1 and BZR1, suggesting that BIN2 can bind directly to BES1 or BZR1 with no requirement for a scaffold protein. Such a conclusion is further strengthened by an inhibition experiment using a synthetic peptide (FRATide), which was derived from a vertebrate GSK3-binding protein (Yost et al., 1998) and was shown to inhibit the phosphorylation of non-primed substrates by GSK3 kinases (Thomas et al., 1999; Farr et al., 2000). As indicated in Figure 3C, the FRATide had little effect on the phosphorylation of BES1 or BZR1 by BIN2 at the concentrations known to be inhibitory to animal GSK3 kinases. Taken together, these in vitro biochemical data strongly suggested that BIN2 phosphorylation of BES1 and BZR1 does not require a priming phosphorylation or a scaffold protein, but involves a direct physical interaction.

A Semidominant Mutation in the BES1 Gene Rescued Two Different bri1 Mutations

A recent report indicated that BES1 is a novel BR-signaling protein (Yin et al., 2002). Our own genetic screens for extragenic suppressors for two different bri1 mutations provided an independent support for the involvement of BES1 in BR signaling. Five semidominant bri1 suppressors, namely m11-1, m42-5, m9-1, m7-1, and m21-1, were identified, the first two suppressing bri1-5 (Cyr-69-Tyr) and the other three suppressing bri1-9 (Ser-662-Phe). These suppressor mutants displayed similar morphological phenotypes that include elongated and wavy petioles, cup-shaped rosette leaves (Figs. 4A and 5F), and strong suppression of the dwarf phenotype of the bri1 mutations (Fig. 4B). One of the suppressors, m11-1, was mapped near the Arabidopsis bacterial artificial chromosome clone F18O14 that contains the BES1 gene, which prompted us to sequence the BES1 gene from the five phenotypically similar bri1 suppressors. As indicated in Figure 4C, the five suppressor mutants contain the exact same C-T mutation in the BES1 gene, resulting in a Pro-233-Leu missense mutation, and were therefore renamed as bes1-101 to bes1-105. Interestingly, this mutation is identical to the bes1-D mutation that was recently discovered in a similar genetic screen for bri1 suppressors (Yin et al., 2002). The identification of six independent bes1 alleles containing the exact same mutation that suppresses three different bri1 mutations provides very strong evidence that BES1 is involved in BR signaling. Because the Pro-233-Leu mutation has no direct effect on the BIN2/BES1 interaction or the phosphorylation of BES1 by BIN2 (data not shown), we suspected that this mutation might block a downstream step of a BIN2-initiated negative regulatory process, thereby resulting in a constitutive active form of BES1. Yin et al. (2002) showed that the Pro-233-Leu mutation resulted in an increased protein stability and nuclear accumulation of BES1, leading to a constitutive activation of a BR-signaling pathway.

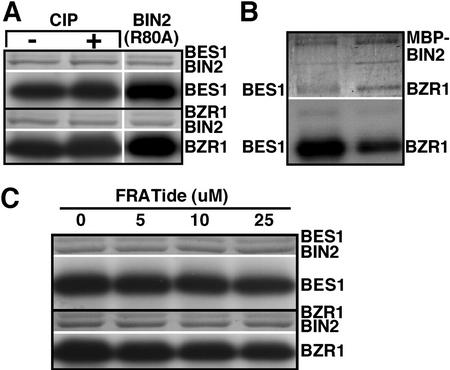

Figure 4.

Identification of semidominant bes1 mutations as suppressors for two different bri1 mutations. A and B, Suppression of bri1-9 mutant phenotypes by a semidominant suppressor mutation m9-1. Shown in A and B (from left to right) are a wild-type plant, a bri1-9 mutant, and a bri1-9 m9-1 double mutant. C, Molecular nature of the five semidominant bri1 suppressor mutations that suppress bri1-5 or bri1-9 mutation. A C-T mutation (indicated by an arrow) in the BES1 gene was detected in the five independently isolated bri1 suppressor mutants, resulting in a missense mutation of Pro-233 to Leu.

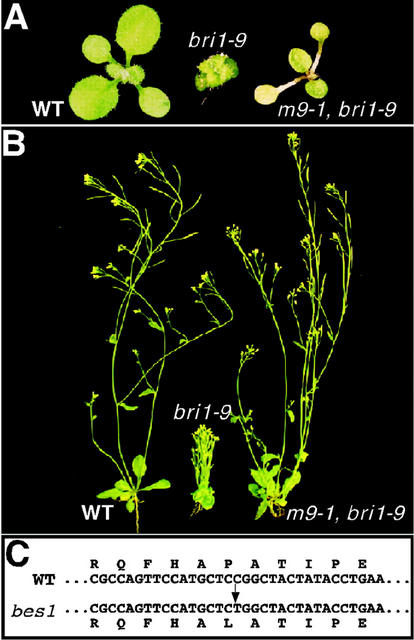

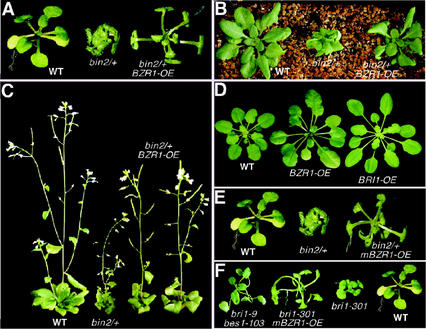

Figure 5.

Overexpression of the BZR1 gene suppressed bin2/+ and bri1 mutant phenotypes. A, Overexpression of the wild-type BZR1 rescued the short-petiole phenotype of the bin2/+ mutant. B, The cabbage-like rosette phenotype of the bin2/+ mutant was rescued by BZR1 overexpression. C, BZR1 overexpression can rescue the overall growth defect and the silique phenotype of the bin2/+ mutant. Shown in A through C (from left to right) are a wild-type plant, the bin2-1/+ mutant, and transgenic bin2-1/+ plants overexpressing the BZR1 gene. D, The overexpression of the wild-type BZR1 gene in a BIN2+ background leads to a phenotype that resembles that of BRI1 overexpression transgenic plants. E, Overexpression of a mutated BZR1 gene containing the Pro-234-Leu mutation rescued the bin2/+ phenotype. Shown here (from left to right) are a wild-type seedling, a bin2-1/+ mutant, and a transgenic bin2-1/+ mutant expressing the mutated BZR1 gene. F, Overexpression of the mBZR1 gene rescued the weak bri1-301 mutation and gives rise to a bes1-like phenotype. From left to right are a bes1-103 bri1-9 double mutant, a transgenic bri1-301 plant expressing the mBZR1 gene, a bri1-301 mutant, and a wild-type control plant.

BZR1 Overexpression Partially Rescued bin2/+ and bri1 Mutant Phenotypes

To investigate whether BZR1 also participates in BR signaling, we transformed a BZR1 cDNA construct driven by the BRI1 promoter into the bin2/+ mutants and screened the resulting transgenic plants by northern-blot analysis for plants that overexpress the BZR1 gene (data not shown). If BZR1 were a bona fide BIN2 substrate, its overexpression in the bin2/+ plants would be able to, at least partially, suppress the bin2/+ phenotype. We reasoned that although a large majority of the overexpressed BZR1 proteins would be phosphorylated by the increased BIN2 activity in the bin2/+ mutants (Li and Nam, 2002), some of them might escape from being phosphorylated by BIN2 to remain active to mediate BR signaling. BZR1 overexpression not only rescued the short petiole and the “cabbage-like” rosette phenotypes of the bin2/+ mutants at early developmental stages (Fig. 5, A and B), but also partially suppressed the overall growth defect at later developmental stages (Fig. 5C). The curly leaf phenotype of cauline leaves and the male sterility phenotype of the bin2/+ mutants were almost completely suppressed in the transgenic BZR1 overexpression bin2/+ plants (Fig. 5C). An effect of BZR1 overexpression on the petiole length was also observed in the BIN2+ background. Transgenic plants overexpressing the BZR1 gene are phenotypically similar to transgenic plants that overexpress the BRI1 gene (Fig. 5D).

Consistent with a recent report that the Pro-234-Leu mutation in the BZR1 gene (bzr1-1D) was recovered as a semidominant mutation that was insensitive to brassinazole, a specific BR biosynthesis inhibitor (Wang et al., 2002), overexpression of the mutated BZR1 (mBZR1) gene containing the Pro-234-Leu mutation driven by the BRI1 promoter not only suppressed the weak bri1-301 mutation but also rescued the bin2/+ mutant phenotype. As indicated in Figure 5E, transgenic bin2/+ plants expressing the mutated BZR1 (mBZR1) gene exhibited similar phenotypes to the BRI1-BZR1 transgenic plants. Transgenic bri1-301 plants expressing the mBZR1 gene similarly showed elongated and wavy petioles, a phenotype that is quite similar to that of the bes1 mutants (Fig. 5F). These transgenic results, when combined with the recently reported genetic data (He et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002), strongly support that BZR1 is also a positive BR-signaling protein that functions downstream of BRI1 and BIN2 in the BR-signaling pathway.

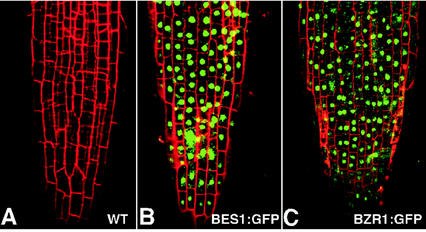

Both BZR1 and BES1 Are Nuclear Proteins

To determine the subcellular localization of BES1 and BZR1 proteins, we translationally fused the entire coding region of the BES1 or BZR1 gene to a modified green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (von Arnim et al., 1998) and used the BRI1 promoter to drive the expression of the resulting BRI1-BES1:GFP or BRI1-BZR1:GFP fusion gene in wild-type Arabidopsis plants. The resulting transgenic plants were phenotypically similar to BRI1-BES1 or BRI1-BZR1 transgenic plants in the BIN2+ background (data not shown), indicating that the GFP-tagged BES1 or BZR1 proteins are still functional. Consistent with the presence of a bipartite nuclear localization signal at their N termini, the GFP-fused BES1 and BZR1 proteins were found mainly in the nucleus (Fig. 6). Thus, BES1 and BZR1 could function as BR-signaling components that transduce BR signal into the nucleus to regulate gene expression. Contrary to the two recent studies that showed BR-stimulated nuclear accumulation of BES1 and BZR1 (Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002), both GFP-fusion proteins were constitutively localized in the nucleus and BR treatment failed to further increase their nuclear accumulation (data not shown). This discrepancy might be attributable to the different tissues used for the BES1/BZR1 localization studies. Wang et al. (2002) and Yin et al. (2002) used dark-grown hypocotyls for their studies, whereas we examined light-grown root tips to determine BES1/BZR1 subcellular localization.

Figure 6.

Nuclear localization of BES1 and BZR1. A, Root tip from a wild-type control plant. B, Root tip from a BRI1-BES1:GFP transgenic seedling. C, Root tip from a BRI1-BZR1:GFP transgenic seedling. The localization patterns of BES1:GFP and BZR1:GFP were analyzed by examining root tips after 1 min of treatment with 10 μg mL−1 propidium iodide (red signal to visualize cell walls) using a confocal microscope (LSM510, Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, UK) filtered with FITC10 set (excitation 488 nm with emission 505–530 and 530–560 nm).

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we describe the identification of two novel Arabidopsis proteins by yeast two-hybrid as potential substrates for the BIN2 GSK3 kinase that negatively regulates BR signaling. Interestingly, the same two proteins were recently identified through two different genetic screens as potential nuclear components of a BR signal transduction pathway (Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002). Our results provide another testimony for the success of the yeast two-hybrid approach in uncovering additional components of a signaling pathway in Arabidopsis.

Our in vitro biochemical experiments strongly suggested that both BES1 and BZR1 are most likely substrates for the BIN2 GSK3 kinase. The two nuclear proteins display specific interactions with BIN2 in the yeast two-hybrid assay. In addition, both proteins contain multiple copies of the consensus S/TxxxS/T GSK3 phosphorylation motif. More importantly, both BES1 and BZR1 can be specifically and efficiently phosphorylated by BIN2 in vitro (Figs. 2 and 3). In fact, under our kinase assay conditions, the transphosphorylation of BES1 and BZR1 by BIN2 is much stronger than the BIN2 autophosphorylation. Furthermore, the BIN2 phosphorylation of BES1 and BZR1 can be inhibited by Li+, a specific inhibitor of all known GSK3 kinases (Klein and Melton, 1996).

Our biochemical data also suggested a novel mechanism for phosphorylating BES1 or BZR1 by the BIN2 GSK3 kinase. In animal cells, GSK3 can only phosphorylate a protein substrate when the substrate is prime-phosphorylated by a distinct kinase or when GSK3 and its substrate are brought together by a scaffold protein (Cohen and Frame, 2001; Harwood, 2001; Woodgett, 2001). Despite the presence of a conserved “primed phosphate”-binding site in BIN2, which is composed of Arg-80, Arg-164, and Lys-189 that correspond to Arg-96, Arg-180, and Lys-205 of the human GSK3β (ter Haar et al., 2001), BIN2 phosphorylation of BES1 and BZR1 does not require a priming phosphorylation event. First, CIP-treated BES1 or BZR1 can be phosphorylated by BIN2 as efficiently as their non-treated counterparts. Second, the Arg-80-Ala mutation in the conserved primed phosphate-binding pocket had little effect on the phosphorylation of either BES1 or BZR1 by BIN2, although a corresponding mutation (Arg-96-Ala) in the human GSK3β completely abolished the ability of GSK3β to phosphorylate primed substrates (Frame et al., 2001). We have also shown that BIN2 phosphorylation of BES1 or BZR1 is not dependent on the presence of a scaffold protein. Both BES1 and BZR1 interacted with BIN2 in yeast cells. In addition, purified GST-BES1 or GST-BZR1 protein was phosphorylated by a purified MBP-BIN2 fusion kinase in vitro. It was also reported that a purified GST-BIN2 protein could interact directly with MBP-BES1 proteins assayed by a GST pull-down experiment (Yin et al., 2002). Furthermore, the FRATide, which was known to inhibit the phosphorylation of non-primed substrates by animal GSK3 kinases, had little effect on the phosphorylation of BES1 or BZR1 by BIN2. These data strongly suggest that BIN2 can phosphorylate BES1 and BZR1 through its direct interaction with the two putative substrates. Such a conclusion is consistent with the fact that the shortest BES1 clone isolated from the yeast two-hybrid screen contains only the C-terminal 52 amino acids but lacks the conserved S/TxxxS/T GSK3 phosphorylation motif. Further experiments are needed to define a minimum BIN2-binding site on BES1 and BZR1.

Although direct evidence for BES1 or BZR1 being the in vivo substrates of the BIN2 kinase is lacking, the existing experimental evidence strongly argues for such a possibility. The Pro-233-Leu mutation in the BES1 gene, which stabilizes the BES1 protein and leads to an increased BES1 accumulation in the nucleus (Yin et al., 2002), suppresses not only bri1 mutations but also the bin2/+ mutant phenotype. A corresponding Pro-234-Leu mutation in the BZR1 gene, which leads to increased protein stability and nuclear accumulation of BZR1, also rescued bri1 and bin2 mutations (He et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002). In this study, we have shown that overexpression of the wild-type BZR1 gene also suppressed the bin2/+ mutant phenotype. Together, these genetic and transgenic data strongly suggested that both BES1 and BZR1 function downstream of BRI1 and BIN2 in the BR-signaling pathway. Second, it has been shown recently that BR treatment inhibited phosphorylation of both BES1 and BZR1 proteins, which is accompanied by increased stability and nuclear accumulation of the two BR-signaling proteins (He et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002), suggesting that both BES1 and BZR1 could be phosphorylated by a kinase that is negatively regulated by BRs. BIN2 would be the best candidate for such a kinase because BIN2 is the only known kinase that is thought to be negatively regulated by BR (Li and Nam, 2002) and can phosphorylate both BES1 and BZR1 in vitro. Because of a phosphorylation-coupled protein degradation process, steady-state levels of the phosphorylated BES1 or BZR1 protein in the bin2 mutant that contains a higher BIN2 activity were not increased (He et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002). However, the levels of the non-phosphorylated BES1 and BZR1 proteins, the two presumed BIN2 substrates, were greatly reduced in the hypermorphic bin2 mutant even after BR treatment (He et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002), supporting BIN2 being the kinase that phosphorylates both BES1 and BZR1 in vivo.

The phosphorylation of BES1 and BZR1 by BIN2 might promote protein degradation, interfere with the nuclear localization, or directly affect the nuclear activities of the two BR-signaling proteins. BR-stimulated dephosphorylation of BES1 and BZR1 was shown to be accompanied by increased protein stability and subsequent nuclear transport of BES1 and BZR1, respectively (Wang et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002). In addition, treatment with MG132, a proteosome inhibitor, dramatically increased the accumulation of the phosphorylated BZR1 protein (He et al., 2002). In contrast, the total amount of BES1 or BZR1 protein is greatly reduced in the hypermorphic bin2-1 mutant (He et al., 2002; Yin et al., 2002). The BR-regulated protein stability of BES1 and BZR1 seems to be crucial for BR signaling. The Pro-Leu mutation found in all known bes1 and bzr1 alleles, a suppressor of both bri1 and bin2 mutations, leads to enhanced stability of both BES1 and BZR1 proteins but has no effect on their phosphorylation by the BIN2 kinase. Consistent with these findings, overexpression of either the wild-type BZR1 gene (Fig. 5) or a BZR1-CFP fusion gene (He et al., 2002) partially rescued the bin2/+ mutant phenotype.

We hypothesize that both BES1 and BZR1 are physiological substrates for the BIN2 GSK3 kinase in BR signaling. In the absence of BR signals, BIN2 is a constitutively active kinase that phosphorylates BES1 and BZR1 through a novel GSK3 phosphorylation mechanism, leading to protein degradation to block the transduction of BR signals into the nucleus. When BR signals are perceived by a BRI1-containing BR receptor complex, BIN2 becomes inactivated by an as yet unknown mechanism, resulting in increased stability and subsequent nuclear accumulation of both BES1 and BZR1. Such a BR-signaling model involving a GSK3 kinase is quite similar to the Wnt-signaling pathway in which a GSK3 kinase, under resting conditions, phosphorylates β-catenin, a nuclear Wnt-signaling protein, leading to its ubiquitin-mediated degradation (Aberle et al., 1997). When Wnt signals bind their corresponding receptors, the GSK3 kinase is inhibited, and β-catenin becomes dephosphorylated, accumulates in the cytosol, and translocates to the nucleus where it binds to transcription factors to activate gene expression (Cohen and Frame, 2001). Further investigation is needed to fully understand the biochemical mechanisms by which BES1/BZR1 are negatively regulated by BIN2 and by which BES1/BZR1 activate nuclear events of BR signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two-Hybrid Screening

We used the matchmaker system (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) for the yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) two-hybrid experiments. The entire BIN2 open reading frame (ORF) containing the bin2-1 mutation was cloned into the pAS2 vector and transformed into yeast Y190 cells. The resulting yeast cells were then transformed with the plasmid DNAs of an Arabidopsis cDNA library (Kim et al., 1997), and putative BIN2 interactors were screened by growth on synthetic medium lacking His but containing 25 mm 3-aminotriazole and confirmed by blue color on 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside containing medium. To determine the specificity of a two-hybrid interaction, Y190 cells containing either pACT2-BES1 or pACT2-BZR1 plasmid were mated with Y187 cells expressing the Gal4 DNA-binding domain or a Gal4 DNA-binding domain fusion protein fused with wild-type or mutated BIN2, BRI1CK, or the N-terminal portion of the Arabidopsis NADPH oxidase (91N). The resulting diploid yeast cells were assayed for the activation of the two reporter genes, HIS3 and LacZ.

Mutant Screening and Mapping

bri1-5 and bri1-9 seeds were soaked in a solution of 0.3% (v/v) ethyl methanesulfonate for 14 to 18 h, rinsed 10 times with water, and planted in individual trays with approximately 500 to 1,000 plants per tray. Seeds from each of 70 trays were collected as individual pools, planted on trays, and screened for non-dwarf plants. One of the suppressors, bri1-5 m11-1 (Wassilewskija ecotype), was mapped by crossing to wild-type plants of the Columbia ecotype. Because the resulting F1 plants retained the cupped-shaped leaf phenotype, indicating that this phenotype of the suppressor is dominant, we analyzed markers in repulsion as was done for bin2 (Li et al., 2001). m11-1 was mapped roughly midway between the markers nga63 (five of 76 recombinants) and so392 (eight of 76 recombinants), which is approximately the same map position of the bacterial artificial chromosome containing the BES1 gene.

Protein Expression and in Vitro Kinase Assays

The entire BIN2 ORF was cloned into the pGEX-KG vector (Guan and Dixon, 1991) or pMAL-c2 vector (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) for generating GST or MBP fusion proteins. A 1.3-kb MunI-BamHI fragment encoding BRI1CK or the entire ORF for BES1 or BZR1 was cloned into pGEX-KG vector to generate GST fusion proteins. The QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used to create mutant GST fusion proteins. Protein induction and purification were carried out according to manufacturers' recommended protocols. For CIP treatment, GST-BES1/GST-BZR1 fusion proteins, while bound on glutathione-agarose beads (Amersham Biosciences AB, Uppsala), were incubated with 20 units of CIP (New England Biolabs) at 37°C for 10 min. Purified BIN2 or BRI1CK fusion proteins were incubated with GST, GST-BES1, or GST-BZR1 fusion proteins at room temperature for 30 min in a 20-μL GSK3 reaction mixture containing 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm dithiothreitol, 100 μm ATP, and 0.5 μL of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci mmol−1, ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA). Increasing concentrations of FRATide (0–25 μm; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) were used to determine the effect of the GSK3-binding peptide on BIN2 activity. Kinase reactions were terminated by adding 5 μL of SDS-containing sample buffer, boiled for 3 min, and separated by an 8% (w/v) SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie Blue, and phosphorylated protein bands were visualized by autoradiography.

Generation of Transgenic Plants

A full-length BZR1 cDNA was cloned into a modified pPZP212 vector (Hajdukiewicz et al., 1994) that contains a 1.7-kb regulatory fragment of the BRI1 gene to generate the BRI1-BZR1 transgene that was used to transform the bin2-1 heterozygous mutants, the bri1-301 mutants, and wild-type Arabidopsis plants. The QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used to create the mutant BZR1 gene containing the Pro-234-Leu mutation. To generate transgenic plants expressing the BRI1-BES1:GFP or BRI1-BZR1:GFP transgene, the entire BES1 or BZR1 coding region was used to replace the BRI1 ORF of the pPZP-BRI1-BRI1:GFP plasmid (Friedrichsen et al., 2000), and the resulting transgene was transformed into wild-type plants.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by a University of Michigan Start-up Fund (to J.L.), by an Overseas Outstanding Young Investigator Award from the Chinese Natural Science Foundation (to J.L.), and by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. GM60519 to J.L.). R.J.S. and A.D.D. were supported by the Undergraduate Biology Research Program and the University of Arizona Honors Program.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.102.010918.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. β-Catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD, Feldmann KA. Molecular genetics of brassinosteroid action. In: Sakurai A, Yokota T, Clouse SD, editors. Brassinosteroids: Steroidal Plant Hormones. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1999. pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD, Langford M, McMorris TC. A brassinosteroid-insensitive mutant in Arabidopsis thalianaexhibits multiple defects in growth and development. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:671–678. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD, Sasse JM. Brassinosteroids, essential regulator of plant growth and development. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998;49:427–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Frame S. The renaissance of GSK3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:769–776. doi: 10.1038/35096075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embi N, Rylatt DB, Cohen P. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle: separation from cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylase kinase. Eur J Biochem. 1980;107:519–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr GH, Ferkey DM, Yost C, Pierce SB, Weaver C, Kimelman D. Interaction among GSK-3, GBP, axin, and APC in Xenopusaxis specification. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:691–702. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame S, Cohen P. GSK3 takes center stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem J. 2001;359:1–16. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame S, Cohen P, Biondi RM. A common phosphate binding site explains the unique substrate specificity of GSK3 and its inactivation by phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1321–1327. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser E, Young N, Dajani R, Franca-Koh J, Ryves J, Williams RS, Yeo M, Webster MT, Richardson C, Smalley MJ et al. Identification of the Axin and Frat binding region of glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2176–2185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichsen DM, Joazeiro CA, Li J, Hunter T, Chory J. Brassinosteroid-insensitive-1 is a ubiquitously expressed leucine-rich repeat receptor serine/threonine kinase. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:1247–1256. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan KL, Dixon JE. Eukaryotic proteins expressed in Escherichia coli: an improved thrombin cleavage and purification procedure of fusion proteins with glutathione S-transferase. Anal Biochem. 1991;192:262–267. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90534-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdukiewicz P, Svab Z, Maliga P. The small, versatile pPZP family of Agrobacteriumbinary vectors for plant transformation. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:989–994. doi: 10.1007/BF00014672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood AJ. Regulation of GSK-3: a cellular multiprocessor. Cell. 2001;105:821–824. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He JX, Gendron JM, Yang Y, Li J, Wang ZY. The GSK3-like kinase BIN2 phosphorylates and destabilizes BZR1, a positive regulator of the brassinosteroid signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10185–10190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152342599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z, Wang ZY, Li J, Zhu Q, Lamb C, Ronald P, Chory J. Perception of brassinosteroids by the extracellular domain of the receptor kinase BRI1. Science. 2000;288:2360–2363. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauschmann A, Jessop A, Koncz C, Szekeres M, Willmitzer L, Altmann T. Genetic evidence for an essential role of brassinosteroids in plant development. Plant J. 1996;9:701–713. [Google Scholar]

- Keller T, Damude HG, Werner D, Doerner P, Dixon RA, Lamb C. A plant homolog of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase gp91phox subunit gene encodes a plasma membrane protein with Ca2+binding motifs. Plant Cell. 1998;10:255–266. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Harter K, Theologis A. Protein-protein interactions among the Aux/IAA proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11786–11791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein PS, Melton DA. A molecular mechanism for the effects of lithium on development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chory J. A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell. 1997;90:929–938. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Nam KH. Regulation of brassinosteroid signaling by a GSK3/SHAGGY-like kinase. Science. 2002;295:1299–1301. doi: 10.1126/science.1065769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Nam KH, Vafeados D, Chory J. BIN2, a new brassinosteroid-insensitive locus in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:14–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.127.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T, Fujioka S, Choe S, Takatsuto S, Yoshida S, Yuan H, Feldmann KA, Tax FE. Brassinosteroid-insensitive dwarf mutants of Arabidopsis accumulate brassinosteroids. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:743–752. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.3.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh MH, Ray WK, Huber SC, Asara JM, Gage DA, Clouse SD. Recombinant brassinosteroid insensitive 1 receptor-like kinase autophosphorylates on serine and threonine residues and phosphorylates a conserved peptide motif in vitro. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:751–766. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.2.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez JM, Ponce MR, Micol JL. The UCU1Arabidopsis gene encodes a SHAGGY/GSK3-like kinase required for cell expansion along the proximodistal axis. Dev Biol. 2002;242:161–173. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryves WJ, Harwood AJ. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 by competition for magnesium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:720–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1664–1668. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70790-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steber CM, McCourt P. A role for brassinosteroids in germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:763–769. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Haar E, Coll JT, Austen DA, Hsiao H-M, Swenson L, Jain J. Structure of GSK3β reveals a primed phosphorylation. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:593–596. doi: 10.1038/89624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GM, Frame S, Goedert M, Nathke I, Polakis P, Cohen P. A GSK3-binding peptide from FRAT1 selectively inhibits the GSK3-catalysed phosphorylation of Axin and β-catenin. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Arnim AG, Deng XW, Stacey MG. Cloning vectors for the expression of green fluorescent protein fusion proteins in transgenic plants. Gene. 1998;221:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Nakano T, Gendron J, He J, Chen M, Vafeados D, Yang Y, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Asami T, Chory J. Nuclear-localized BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced growth and feedback suppression of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Dev Cell. 2002;2:505–513. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00153-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Seto H, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Chory J. BRI1 is a critical component of a plasma-membrane receptor for plant steroids. Nature. 2001;410:380–383. doi: 10.1038/35066597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett JR (2001) Judging a protein by more than its name: GSK-3. Sci STKE, http://stke.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/sigtrans;2001/100/re12 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yin Y, Wang ZY, Mora-Garcia S, Li J, Yoshida S, Asami T, Chory J. BES1 accumulates in the nucleus in response to brassinosteroids to regulate gene expression and promote stem elongation. Cell. 2002;109:181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00721-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost C, Farr GH, III, Pierce SB, Ferkey DM, Chen MM, Kimelman D. GBP, an inhibitor of GSK-3, is implicated in Xenopusdevelopment and oncogenesis. Cell. 1998;93:1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]