Abstract

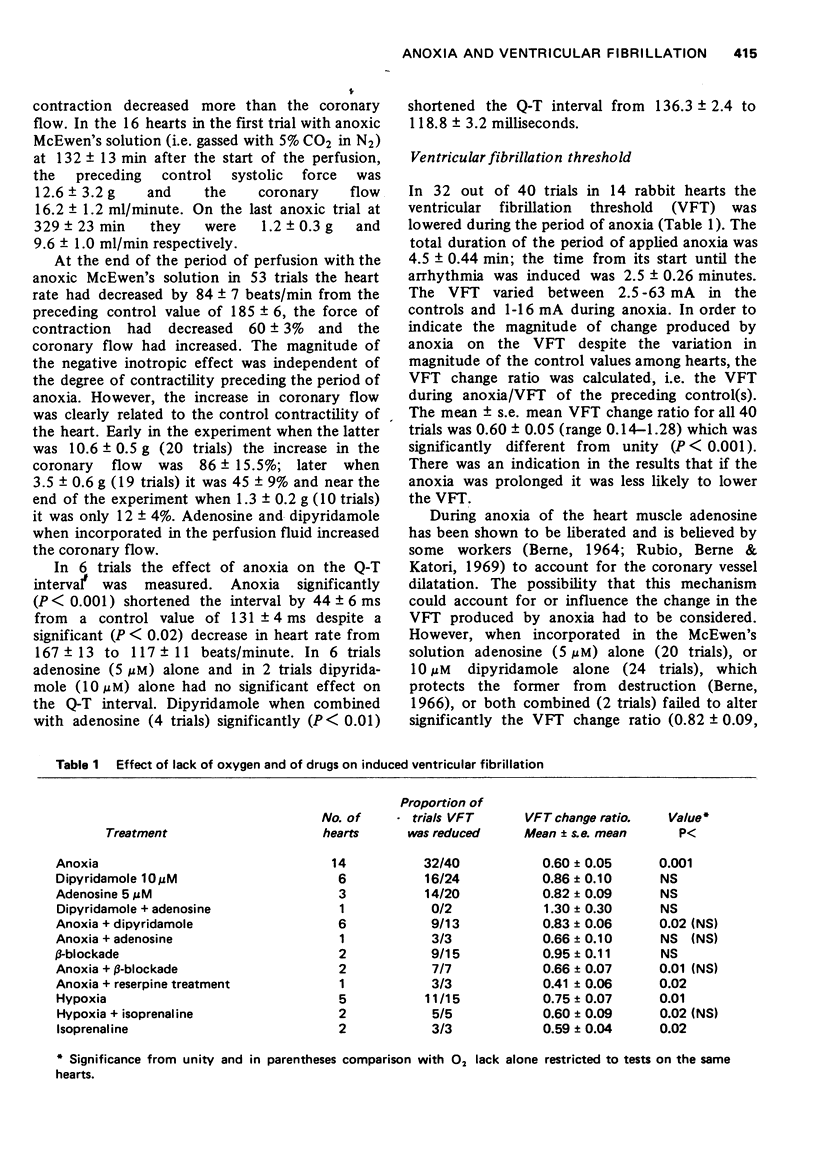

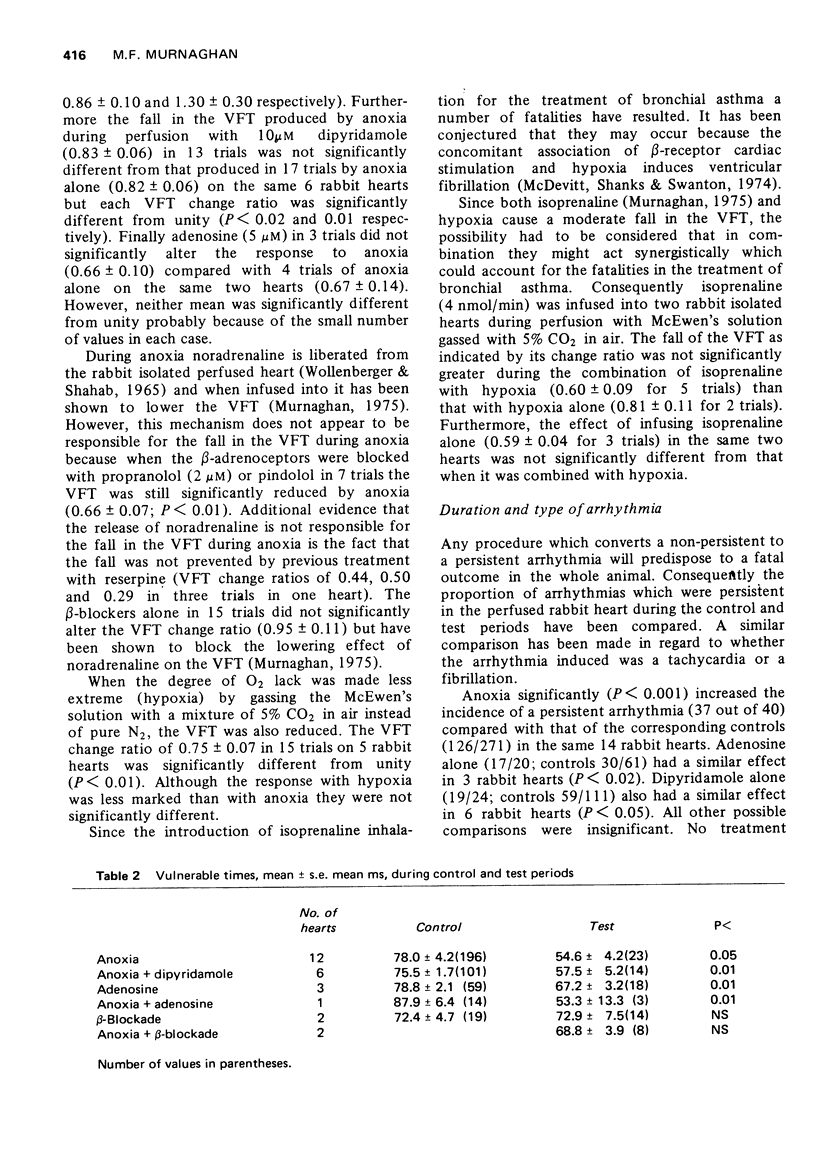

1. The ventricular fibrillation threshold (VFT) was measured in the isolated heart of the rabbit perfused via the aorta with McEwen's solution at 37 degrees C by applying a single 10 ms pulse of current during the vulnerable period of late systole. The arrhythmia induced was either fibrillation or a rapid tachycardia. 2. Gassing the McEwen's solution with 5% CO2 in N2 (anoxia) instead of with carbogen caused a negative inotropic and chronotropic effect and significantly lowered the VFT. Although anoxia releases noradrenaline from the heart the effect of anoxia on the VFT was not prevented by beta-adrenoceptor blockade with propranolol or pindolol or by previous treatment with reserpine. 3. Perfusion with adenosine (5 muM) which is released from the heart muscle by anoxia, or with dipyridamole (10 muM) which protects the adenosine from binding or destruction by the tissues, or with both combined failed to alter the VFT significantly. Furthermore neither adenosine nor dipyridamole significantly altered the effect of anoxia on the VFT. 4. Anoxia, adenosine and dipyridamole significantly increased the duration of the induced arrhythmia when compared with that of the controls. 5. Anoxia and adenosine significantly shortened the vulnerable time, i.e., the minimal time after the R-wave of the ECG at which the pulse had to be applied to induce the arrhythmia. 6. Perfusion with the McEwen's solution gassed with 5% CO2 in air (hypoxia) significantly lowered the VFT but the effect was not as great as with anoxia. Isoprenaline when infused lowered the VFT but this effect was not potentiated by hypoxia. 7. The results indicate that (a) anoxia lowers the VFT in the perfused isolated heart of the rabbit and that this effect is not due to adenosine or noradrenaline released by the anoxia and (b) hypoxia does not sensitize the heart to the arrhythmic effect of isoprenaline.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Afonso S. Coronary vasodilator responses to hypoxia and induced tachycardia before and after lidoflazine. Am J Physiol. 1969 Feb;216(2):297–300. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.216.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso S., O'Brien G. S. Enhancement of coronary vasodilator action of adenosine triphosphate by dipyridamole. Circ Res. 1967 Apr;20(4):403–408. doi: 10.1161/01.res.20.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso S., O'Brien G. S. Mechanism of enchancement of adenosine action by dipyridamole and lidoflazine, in dogs. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1971 Nov;194(1):181–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BADEER H., HORVATH S. M. Role of acute myocardial hypoxia and ischemic-nonischemic boundaries in ventricular fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1959 Nov;58:706–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(59)90228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNE R. M. REGULATION OF CORONARY BLOOD FLOW. Physiol Rev. 1964 Jan;44:1–29. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1964.44.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUNAG R. D., DOUGLAS C. R., IMAI S., BERNE R. M. INFLUENCE OF A PYRIMIDOPYRIMIDINE DERIVATIVE ON DEAMINATION OF ADENOSINE BY BLOOD. Circ Res. 1964 Jul;15:83–88. doi: 10.1161/01.res.15.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURN J. H., HUKOVIC S. Anoxia and ventricular fibrillation; with a summary of evidence on the cause of fibrillation. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1960 Mar;15:67–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1960.tb01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHARDACK W. M., GAGE A. A., FEDERICO A. J., CUSICK J. K., MATSUMOTO P. J., LANPHIER E. H. REDUCTION BY HYPERBARIC OXYGENATION OF THE MORTALITY FROM VENTRICULAR FIBRILLATION FOLLOWING CORONARY ARTERY LIGATION. Circ Res. 1964 Dec;15:497–502. doi: 10.1161/01.res.15.6.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COFFMAN J. D., GREGG D. E. Ventricular fibrillation during uniform myocardial anoxia due to asphyxia. Am J Physiol. 1960 May;198:955–958. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1960.198.5.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceremuzyński L., Staszewska-Barczak J., Herbaczynska-Cedro K. Cardiac rhythm disturbances and the release of catecholamines after acute coronary occlusion in dogs. Cardiovasc Res. 1969 Apr;3(2):190–197. doi: 10.1093/cvr/3.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN J., MOE G. K. NONUNIFORM RECOVERY OF EXCITABILITY IN VENTRICULAR MUSCLE. Circ Res. 1964 Jan;14:44–60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J. Ventricular vulnerability during acute coronary occlusion. Am J Cardiol. 1969 Dec;24(6):857–864. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90476-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jageneau A. H., Schaper W. K., Van Gerven W. Enhancement of coronary reactive hyperemia in unanesthetized pigs by an adenosine-potentiator (Lidoflazine). Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmakol. 1969;265(1):16–23. doi: 10.1007/BF01417207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolassa N., Pfleger K., Rummel W. Specificity of adenosine uptake into the heart and inhibition by dipyridamole. Eur J Pharmacol. 1970 Mar;9(3):265–268. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(70)90221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCEWEN L. M. The effect on the isolated rabbit heart of vagal stimulation and its modification by cocaine, hexamethonium and ouabain. J Physiol. 1956 Mar 28;131(3):678–689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacConaill M., Murnaghan M. F. Effect of adrenaline on the ventricular fibrillation threshold in the isolated rabbit's heart. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1967 Nov;31(3):523–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1967.tb00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt D. G., Shanks R. G., Swanton J. G. Further observations on the cardiotoxicity of isoprenaline during hypoxia. Br J Pharmacol. 1974 Mar;50(3):335–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1974.tb09608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnaghan M. F. The effect of sympathomimetic amines on the ventricular fibrillation threshold in the rabbit isolated heart. Br J Pharmacol. 1975 Jan;53(1):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1975.tb07323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson R. A. Changes in content of purine nucleoside in canine myocardium during coronary occlusion. Circ Res. 1970 Mar;26(3):301–306. doi: 10.1161/01.res.26.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parratt J. R., Wadsworth R. M. The effects of dipyridamole on coronary post-occlusion hyperaemia and on myocardial vasodilatation induced by systemic hypoxia. Br J Pharmacol. 1972 Dec;46(4):594–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1972.tb06886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R. M., Spear J. F., Moore E. N., Horowitz L. H., Sonne J. E. Vulnerability of canine ventricle to fibrillation during hypoxia and respiratory acidosis. Chest. 1973 Jun;63(6):986–994. doi: 10.1378/chest.63.6.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio R., Berne R. M., Katori M. Release of adenosine in reactive hyperemia of the dog heart. Am J Physiol. 1969 Jan;216(1):56–62. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.216.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio R., Berne R. M. Release of adenosine by the normal myocardium in dogs and its relationship to the regulation of coronary resistance. Circ Res. 1969 Oct;25(4):407–415. doi: 10.1161/01.res.25.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHUMWAY N. E., JOHNSON J. A., STISH R. J. The study of ventricular fibrillation by threshold determinations. J Thorac Surg. 1957 Nov;34(5):643–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH G., LAWSON D. D. The protective effect of inhalation of oxygen at two atmospheres absolute pressure in acute coronary arterial occlusion. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1962 Mar;114:320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres L., Papp G. Effect of arterial hypoxia on the susceptibility to arrhythmia of the heart. Acta Physiol Acad Sci Hung. 1967;32(1):143–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAUTWEIN W., GOTTSTEIN U., DUDEL J. Der Aktionsstrom der Myokardfaser im Sauerstoffmangel. Pflugers Arch. 1954;260(1):40–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00363778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull A. D., MacLean L. D., Dobell A. R., Demers R. The influence of hyperbaric oxygen and of hypoxia on the ventricular fibrillation threshold. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1965 Dec;50(6):842–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenberger A., Shahab L. Anoxia-induced release of noradrenaline from the isolated perfused heart. Nature. 1965 Jul 3;207(992):88–89. doi: 10.1038/207088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]